Abstract

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is a highly effective program, vital to our nation’s health and well-being. SNAP’s entitlement funding structure allows it to provide benefits to anyone who meets the program’s eligibility requirements, and this structure also enables SNAP to respond quickly when need increases. Research shows that SNAP reduces poverty for millions, improves food security, and is linked with improved health.

Despite SNAP’s successes, there is room to build on its considerable accomplishments. Evidence suggests that current benefit levels are not adequate for many households. Some vulnerable groups have limited SNAP eligibility, and some eligible individuals face barriers to SNAP participation.

Policymakers should address these shortcomings by increasing SNAP benefits and expanding SNAP eligibility to underserved groups. The federal government and states should also continue improving policies and procedures to improve access for eligible individuals.

SNAP—the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly the Food Stamp Program—is America’s most important food assistance program. SNAP helps close to 40 million Americans afford a nutritious diet in an average month. Nearly 90% of recipients are in families with children, elderly people, or those with disabilities.1

SNAP focuses benefits on households with the lowest incomes: households in poverty receive about 92% of SNAP benefits, and households in deep poverty receive 55% of benefits.1 SNAP benefits average only about $1.40 per person per meal. Despite a modest benefit that may be inadequate for many families, SNAP has contributed to measurable improvements in the health and well-being of Americans.

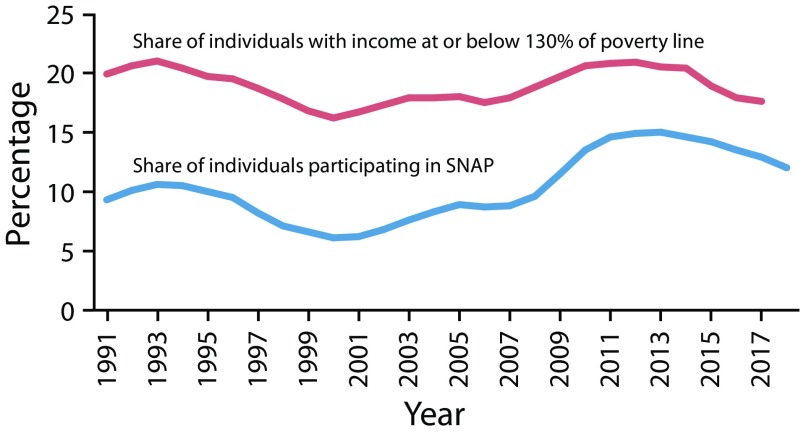

Much of SNAP’s success is attributable to its entitlement structure. SNAP benefits are available to anyone who meets the program’s eligibility rules. This enables SNAP to respond quickly and effectively when need increases, such as during an economic downturn or after a natural disaster. SNAP enrollment rises when more people become eligible, such as during a weaker economy, and falls when the economy improves (Figure 1). During the Great Recession of 2007 through 2009, for example, SNAP expanded by about 20 million people, but enrollment has since fallen by 7 million people and continues to fall.

FIGURE 1—

Tracking Changes in Share of Near-Poor Population and Share of Population Receiving SNAP: United States, 1991–2018

Note. SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Poverty estimates are annual estimates. SNAP shares of resident population are calendar year averages.

Source. US Census Bureau; US Department of Agriculture.

FOOD INSECURITY, POVERTY, AND HEALTH

SNAP, along with other federal nutrition assistance programs, has largely eliminated severe hunger and malnutrition in the United States, although more needs to be done to eliminate food insecurity. A team of doctors visiting areas in the rural South and Appalachia in the late 1960s were stunned to find children with symptoms associated with malnutrition.2 In response, President Richard Nixon and lawmakers from both major political parties established national eligibility and benefit standards for the Food Stamp Program and eased enrollment barriers. The team returned a decade later, after the program had expanded nationwide, and found dramatic improvement, especially among children. They concluded that the Food Stamp Program had a greater impact on improving quality of life and nutrition than any other social program.2

Evaluating SNAP’s impact is difficult because of its broad coverage and because participants may differ in important, but unmeasurable ways from nonparticipants. Participation is voluntary, and eligible households with greater unmet food needs are likelier to apply for SNAP. Although it would generally not be feasible to measure all of SNAP’s impacts using randomized control trials, nonexperimental studies with rigorous research designs that account for selection bias have yielded compelling evidence that SNAP reduces food insecurity (when households lack resources to enable them consistent access to nutritious food) and poverty. Research in the past decade has also revealed associations between SNAP participation and positive health outcomes.

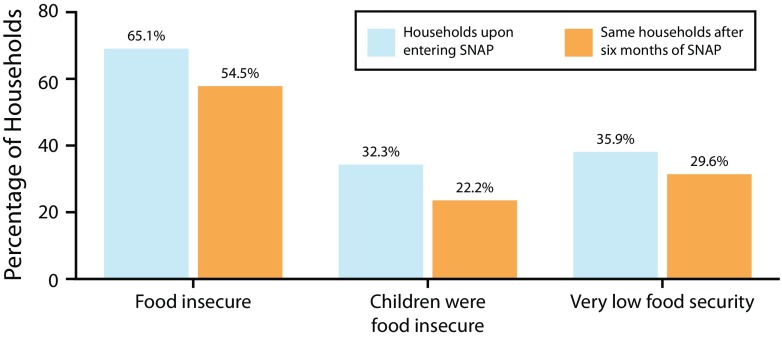

In 2017, 11.8% of households experienced food insecurity, including 4.5% with very low food security (i.e., those in which household members take actions such as eating less than they would like because of difficulty affording food).3 SNAP participation reduces food insecurity by up to 30%, even more for some populations, recent evidence from studies with strong research designs shows (Figure 2).4

FIGURE 2—

Household Food Security Status Among Households New to SNAP and After Six Months: United States, 2012

Note. SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. “Food insecure” means household lacked consistent access to nutritious food at some point during the year because of limited resources. “Household with food-insecure children” are those in which both children and adults experience food insecurity during the year. “Very low food security” means ≥ 1 household member has to skip meals or otherwise eat less at some point during the year because they lack money. This chart shows the results of a study on longitudinal data comparing households upon beginning to receive SNAP and 6 months later.

Source. J. Mabli et al.4

More generous SNAP benefits reduce food insecurity further. The 2009 Recovery Act (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Pub L. No. 111–5), an economic stimulus response to the recession that included a temporary, across-the-board increase in SNAP benefits, provided a natural experiment that some researchers have used to isolate the effect of raising SNAP benefits on food insecurity. Because of the Great Recession, very low food security was expected to increase in 2009. Instead it fell that year (when the benefit increase took effect) among low-income households likely eligible for SNAP while rising among households with somewhat higher incomes who are less likely to be eligible. The Recovery Act increase may have decreased the prevalence of very low food security among SNAP participants by roughly one third.5

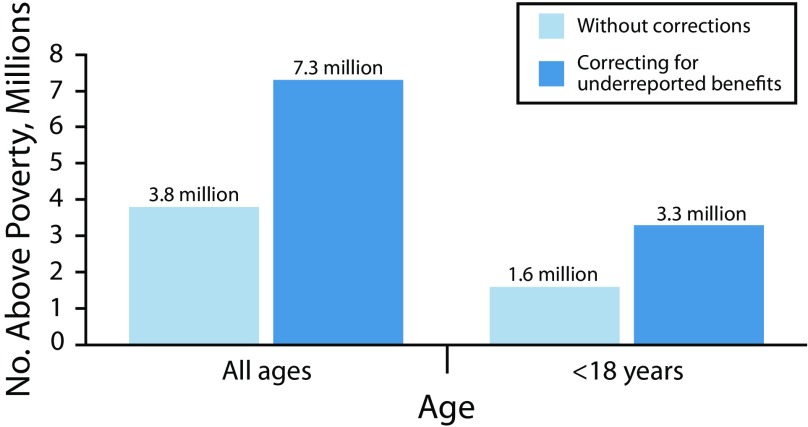

SNAP reduces poverty by giving benefits to households to buy groceries, allowing them to spend more of their budgets on other basic needs, such as housing, electricity, and medical care. SNAP raised the income of 7.3 million people above the poverty line in 2016—including 3.3 million children (Figure 3), more than any other program except the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits combined—and made millions of others less poor.6 It also lifted the income of 1.9 million children above 50% of the poverty line in 2016, more than any other benefit program.4

FIGURE 3—

Millions of Adults and Children Kept Above Poverty Line by SNAP: United States, 2016

Note. SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The figure uses the Supplemental Policy Measure (SPM) and the 2017 SPM poverty line adjusted for inflation. Survey data tend to underreport government benefits. We corrected for this for SNAP and Supplemental Security Income and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

Source. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.6 Corrections for underreported government assistance are from the US Department of Health and Human Services Urban Institute Transfer Income Model.

A National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine expert panel found compelling evidence of SNAP’s crucial role in reducing poverty among children and their families. The panel found that raising SNAP benefits by 20% to 35% along with other changes to SNAP and programs such as the housing voucher program and Earned Income Tax Credit would reduce childhood poverty significantly.7

HEALTH OUTCOMES

Research shows a consistent correlation between food insecurity and health problems throughout different stages of life, contributing to growing recognition that food security is a leading public health priority.8 Food insecurity is linked to poorer quality diet, chronic health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, and overall poorer health. Among children, food insecurity is also associated with frequent infections; among older adults, it is linked to more daily living limitations and lower quality of life.9–12

Emerging research links SNAP with improved health outcomes. Adults receiving SNAP have more positive self-assessments of their health status; they also miss fewer days of work because of illness, make fewer physician office visits, and have a reduced likelihood of demonstrating psychological distress.13–15 Children receiving SNAP report better health status than do their counterparts who are not recipients, and their households are less likely to have to sacrifice health care to pay for other necessary expenses.16,17 When compared with families who keep benefits, working families with children younger than 4 years who lose at least some of their SNAP benefits have a higher risk of negative health outcomes.18

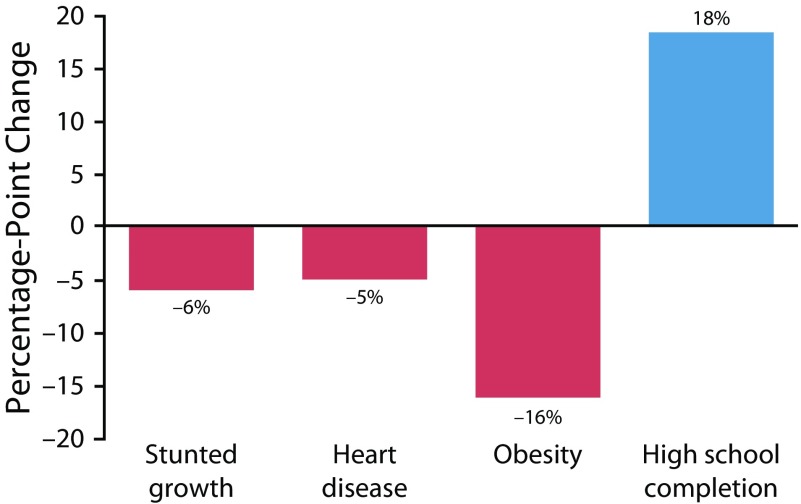

Receiving SNAP in early life can lead to improved outcomes later on. Research that compares pregnant mothers who received food assistance benefits to those who did not as the program was rolling out in the 1960s and 1970s found that mothers who had access during their pregnancy gave birth to fewer low birth weight babies.19 In a similar study, adults who were able to receive food stamps as young children had lower risks as adults of obesity and other conditions related to heart disease and diabetes (Figure 4).20 Another working paper using similar methods linked receiving SNAP as a young child with increased longevity and positive economic outcomes.21

FIGURE 4—

Long-Term Effects of SNAP Participation: United States, 1968–2009

Note. SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The study compared the likelihood of adult outcomes among individuals who had access to SNAP (then food stamps) in early childhood after its introduction in the 1960s and early 1970s with similar children who did not (because they were born before its introduction) in each county.

Source. Hoynes et al.20

SNAP may also help participants take required medications by allowing them to spend money on medicine that they would have spent on food. (Taking less than the prescribed amount because of cost is a significant public health problem, affecting up to 1 in 4 working-age adults.22) Elderly individuals who participated in SNAP were 30% less likely to take less medication than prescribed because of cost than were nonparticipants, one study found.23

Elderly participants who receive SNAP are also less likely to be admitted to a nursing home or hospital than are low-income elderly individuals who do not participate. Findings from a study of more than 60 000 low-income seniors show that 1 year after participants started receiving SNAP, their likelihood of entering a nursing home or being hospitalized is 23% and 4% less, respectively.24 Research using longitudinal data also finds a reduction in the likelihood of hospitalization of 46% among food-insecure, elderly individuals participating in SNAP, and 18% among elderly who are food secure, compared with low-income seniors who are not participants.25

In addition, an analysis of national data shows a relationship between SNAP participation and reduced health care expenditures. In a study that controlled for variables that affect spending on health, low-income SNAP-participating adults have annual health care costs that are on average nearly 25% (about $1400) less than those of nonparticipants. The differences are even greater among those with hypertension (nearly $2700 less) and coronary heart disease (about $4100 less).26 Two other studies designed to control for potential bias because of unobserved differences between SNAP participants and nonparticipants also found an association between SNAP participation and reduced health care costs of as much as $5000 per person per year.27,28

AREAS FOR IMPROVEMENT

Although SNAP is an effective program with positive health outcomes for participants, there is room to build on its considerable accomplishments. Evidence shows that SNAP’s modest benefits are likely insufficient to adequately supplement the income of America’s poor and that increasing benefits would contribute to improved outcomes for many households.29

SNAP benefit levels are calculated using a formula that is based on the cost of the US Department of Agriculture’s Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), intended to represent a diet that low-income families can buy at relatively low cost.30 The TFP is estimated using nationwide data on the cost of a market basket of foods consistent with those low-income households purchase, following the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. To meet cost constraints, nutrient standards, food group requirements, and other considerations, the TFP model results in market baskets of foods that may be impractical and depart, sometimes dramatically, from what people currently consume. For example, by choosing many foods that require substantial preparation, the TFP implicitly assumes that low-income households will spend significant amounts of time preparing meals mostly from scratch and are able to consume a diet that differs significantly from actual consumption patterns.31,32 Furthermore, the TFP fails to meet all nutritional guidelines, does not allow spending variation because of family composition, and does not adequately account for medically necessary dietary needs and restrictions.31,33,34

There is strong evidence that participants often deplete their SNAP benefits and other resources to buy food soon after receiving benefits, resulting in reduced food consumption and other negative outcomes at the end of the month. Households spend less on food as the month goes on. For the first 2 days after receiving benefits, households participating in SNAP spend $66 daily on food. Spending falls to less than $18 per day for the rest of the month.35 Although the monthly decline in spending alone may not be cause for alarm, as households may be purchasing food that lasts throughout the month, evidence also suggests effects on food consumption: in the final 2 days of the month, adult SNAP participants consume 38% fewer calories per day than in the days preceding.36 This monthly food consumption cycle has negative consequences; children’s test scores fall throughout the benefit month, and children have a greater likelihood of misbehaving in school as the month proceeds, studies show.37–39

Many vulnerable Americans are largely or entirely ineligible to participate in SNAP. Some adults without dependent children in their household can receive only 3 months of SNAP benefits out of every 36 months. SNAP eligibility is limited to several classes of lawfully present immigrant groups, such as children, refugees, and asylees and some legal immigrant adults who have been in the United States for at least 5 years. Many low-income college students who need help paying for groceries are ineligible for SNAP.

Puerto Rico has an inadequate block grant for nutrition assistance—called the Nutrition Assistance Program—that it has operated since 1982. SNAP can serve all applicants who meet the program’s eligibility criteria because of its entitlement structure, but the Nutrition Assistance Program must set income requirements and benefit amounts below those in SNAP to stay within its fixed annual funding. This prevents the Nutrition Assistance Program from expanding to respond to increased need, such as following a natural disaster. The recent devastation caused by hurricanes Irma and María, as well as longstanding economic problems, demonstrated these limitations; although Congress provided funding for additional benefits in response to the disasters, this funding arrived much more slowly than it would have under SNAP and did not address Puerto Rico’s long-term need for improved food security and health.

States have made tremendous progress at reaching individuals eligible for SNAP by streamlining application and recertification processes, reducing paperwork requirements for participants, and using technology to process SNAP cases more efficiently. SNAP reaches most people eligible for the program, with an 85% participation rate in 2016.40 But in several ways, eligible individuals face difficulty applying or staying connected to the program. For example, seniors have very low participation rates, below 50%.40 Also, some individuals with disabilities may face barriers in completing the enrollment process or maintaining eligibility. Some families with immigrants may face language barriers, and recent anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric may discourage some eligible immigrants from participating. Many families still experience “churn”—exiting SNAP because of administrative hurdles, despite being eligible, and then shortly reapplying. And many individuals who meet SNAP’s eligibility requirements would also meet the requirements of other public benefit programs but often face inefficient and duplicative enrollment processes that present barriers to access. As a result of differing levels of access across states, estimates of state rates of participation among eligible individuals ranged from below 60% in some states to 100% in others.

These issues point to several areas in which SNAP can build on its success. Raising SNAP benefits would allow households to better afford healthy food. It could contribute to improved health and other positive outcomes for many households, particularly those who have insufficient resources to last throughout the month. Lifting or easing eligibility restrictions for adults without dependent children, immigrants, students, and other groups could improve their food security. States can continue improving policies and procedures to enable more eligible people to apply and help participants who remain eligible stay connected to the program. States can also take steps to increase cross-program efficiencies, such as by allowing one program’s eligibility determination to simplify the determination in another.

KEY DRIVERS OF ECONOMIC INSECURITY

SNAP improves food security, reduces poverty, and is associated with improved health for millions of Americans. Although there are areas for improvement, it is important to recognize that the key drivers of food insecurity are outside the program’s control.

Low-income families face multiple challenges in achieving economic security and mobility. For many low-income workers, employment does not offer a pathway to a stable income. Jobs with low wages often have unpredictable and varying schedules and do not provide key benefits such as paid sick leave and health insurance. Meanwhile, costs for basic necessities continue to rise; many low-income families face housing instability because of high housing costs, for example, and many cannot afford adequate childcare, with available assistance unable to match needs. Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made health insurance more accessible, millions of low-income individuals remain uninsured. Some, for example, live in states that have chosen not to expand Medicaid and thus are in a coverage gap, with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but below the eligibility standards for ACA premium tax credits to buy private coverage. Others have an offer of employer coverage that technically qualifies as affordable but is in practice not affordable. For households with little means to meet basic needs, financial assistance is very limited, as the reach of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families has declined dramatically in the past 2 decades.

SNAP plays a critical role in promoting food security and good health. Although low-income families may worry about whether their job will last through the month or how to afford the rent or their child’s next doctor’s appointment, they know that SNAP can help them obtain adequate food. Despite these important effects, SNAP cannot make up for the lack of a well-paying job or a stable place to live. Analyzing SNAP’s impact within this context; recommending policy changes that focus on the root causes of poverty, hunger, and hardship; and focusing recommendations for SNAP on policies that fall within the program’s purview would help researchers, advocates, and policymakers promote appropriate policies to build on SNAP’s successes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work draws on previous literature reviews published by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, and various staff, including Dottie Rosenbaum, Ed Bolen, Lexin Cai, and Catlin Nchako, have contributed research to those pieces. Steven Carlson has published literature reviews on SNAP and links with children, health, and benefit adequacy that this article drew from as well.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this study.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Cronquist K, Lauffer S. Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2017. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotz N. Hunger in America: The Federal Response. New York: Field Foundation; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2017. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mabli J, Ohls J, Dragoset L, Castner L, Santos B. Measuring the Effect of SNAP Participation on Food Security. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nord M, Prell M. Food Security Improved Following the 2009 ARRA Increase in SNAP Benefits. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Safety net more effective against poverty than previously thought. 2015. Available at: http://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/safety-net-more-effective-against-poverty-than-previously-thought. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murthy VH. Food insecurity: a public health issue. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(5):655–657. doi: 10.1177/0033354916664154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seligman HK, Berkowitz SA. Aligning programs and policies to support food security and public health goals in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:319–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(2):203–212. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman-Jensen A, McFall W, Nord M. Food Insecurity in Households with Children. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1830–1839. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory CA, Deb P. Does SNAP improve your health? Food Policy. 2015;50:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller DP, Morrissey T. Using natural experiments to identify the effects of SNAP on child and adult health. 2017. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1103&context=ukcpr_papers. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 15.Oddo VM, Mabli J. Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and psychological distress. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):e30–e35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joyce KM, Breen A, Ettinger de Cuba S, Cook JT, Barrett KW. Household hardships, public programs, and their associations with the health and development of very young children: insights from Children’s HealthWatch. J Appl Res Child. 2012;3(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ettinger de Cuba S, Weiss I, Pasquariello J et al. The SNAP vaccine: boosting children’s health. 2012 Available at http://childrenshealthwatch.org/the-snap-vaccine-boosting-childrens-health. Accessed May 6, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ettinger de Cuba S, Chilton M, Bovell-Ammon A et al. Loss of SNAP is associated with food insecurity and poor health in working families with young children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(5):765–773. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almond D, Hoynes HW, Schanzenbach DW. Inside the War on Poverty: the impact of food stamps on birth outcomes. Rev Econ Stat. 2011;93(2):387–403. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoynes HW, Schanzenbach DW, Almond D. Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. Am Econ Rev. 2016;106(4):903–934. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoynes H, Bailey MB, Rossin-Slater M, Walker R. Is the social safety net a long-term investment? Large-scale evidence from the Food Stamps Program. 2019. Available at: https://gspp.berkeley.edu/research/working-paper-series/is-the-social-safety-net-a-long-term-investment-5cd06d6b43b4a4.02083762. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 22.Herman D, Afulani P, Coleman-Jensen A, Harrison GG. Food insecurity and cost-related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):e48–e59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivasan M, Pooler JA. Cost-related medication nonadherence for older adults participating in SNAP, 2013–2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):224–230. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szanton S., Samuel LJ, Cahill R et al. Food assistance is associated with decreased nursing home admissions for Maryland’s dually eligible older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):162. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0553-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J. Are older adults who participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program healthier than eligible nonparticipants? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. The Gerontologist. 2015;55(suppl 2):672. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Rigdon J, Meigs JB, Basu S. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participation and health care expenditures among low-income adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1642–1649. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholas LH. Can food stamps help to reduce Medicare spending on diabetes? Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyerhoefer CD, Pylypchuk Y. Does participation in the Food Stamp Program increase the prevalence of obesity and health care spending? Am J Agric Econ. 2008;90(2):287–305. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson S. More adequate SNAP benefits would help millions of participants better afford food. 2019. Available at: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/more-adequate-snap-benefits-would-help-millions-of-participants-better. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 30.Carlson A, Lino M, Juan WY, Hanson K, Basiotis PP. Thrifty Food Plan, 2006. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drewnowski A, Eichelsdoerfer P. Can low-income Americans afford a healthy diet? Nutr Today. 2010;44(6):246–249. doi: 10.1097/NT.0b013e3181c29f79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilde PE, Llobrera J. Using the Thrifty Food Plan to assess the cost of a nutritious diet. J Consum Aff. 2009;43(2):274–304. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziliak JP. Modernizing SNAP benefits. 2016. Available at: http://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/ziliak_modernizing_snap_benefits.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 34.Babb AM, Wasserman JK, Knudsen DC, Lalevich ST. An examination of medically necessary diets within the framework of the Thrifty Food Plan. Ecol Food Nutr. 2019;58(3):236–246. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2019.1598978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiehen L, Newman C, Kirlin A. The food-spending patterns of households participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: findings from USDA’s FoodAPS. 2017. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84780/eib-176.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 36.Todd J. Revisiting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program cycle of food intake: investigating heterogeneity, diet quality, and a large boost in benefit amounts. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2015;37(3):437–458. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gassman-Pines A, Bellows L. Food instability and academic achievement: a quasi-experiment using SNAP benefit timing. Am Educ Res J. 2018;55(5):897–927. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotti C, Gordanier J, Ozturk OD. When does it count? The timing of food stamp receipt and educational performance. Econ Educ Rev. 2018;66:40–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gennetian LA, Seshadri R, Hess ND, Winn AN, Goerge RM. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit cycles and student disciplinary infractions. Soc Serv Rev. 2016;90(3):403–433. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunnyngham K. Trends in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation rates: fiscal year 2010 to fiscal year 2016. 2018. Available at: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/snap/Trends2010-2016.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2019.