Abstract

Objectives. To determine whether (1) participating in HealthLinks, and (2) adding wellness committees to HealthLinks increases worksites’ evidence-based intervention (EBI) implementation.

Methods. We developed HealthLinks to disseminate EBIs to small, low-wage worksites. From 2014 to 2017, we conducted a site-randomized trial in King County, Washington, with 68 small worksites (20–200 employees). We assigned worksites to 1 of 3 arms: HealthLinks, HealthLinks plus wellness committee (HealthLinks+), or delayed control. At baseline, 15 months, and 24 months, we assessed worksites’ EBI implementation on a 0% to 100% scale and employees’ perceived support for their health behaviors.

Results. Postintervention EBI scores in both intervention arms (HealthLinks and HealthLinks+) were significantly higher than in the control arm at 15 months (51%, 51%, and 23%, respectively) and at 24 months (33%, 37%, and 24%, respectively; P < .001). Employees in the intervention arms perceived greater support for their health at 15 and 24 months than did employees in control worksites.

Conclusions. HealthLinks is an effective strategy for disseminating EBIs to small worksites in low-wage industries.

Public Health Implications. Future research should focus on scaling up HealthLinks, improving EBI maintenance, and measuring impact of these on health behavior.

Chronic diseases such as cancer and heart disease are leading causes of death in the United States.1 Evidence-based interventions (EBIs) decrease risk for chronic disease and illness by reducing or eliminating health risk behaviors such as physical inactivity, unhealthy eating habits, and smoking.2 Approximately 60% of people 16 and years and older are currently employed,3 making worksites a good channel to implement EBIs that address chronic disease prevention and early detection. Unfortunately, small and low-wage worksites have limited access to EBIs and face barriers to implementation.4,5 Compared with larger companies, small worksites are less likely to offer EBIs to support cancer screening, healthy eating, physical activity, or smoking cessation.6 Small worksites in low-wage industries are least likely to offer EBIs and more likely to have employees with low socioeconomic status who are at increased risk for chronic diseases.7–9

Small worksites’ key barriers to implementing EBIs include lack of time, accessibility, and resources.10–12 These barriers limit the extent to which these worksites adopt and implement EBIs, but little research exists on how to address them. A recent review of worksite health promotion interventions for low-wage worksites13 described interventions that target both individual- and organizational-level practices; most of these interventions focused on individual-level outcomes during evaluation. Research measuring small worksites’ implementation and maintenance of EBIs over time is limited. We build on previous studies that have tested small worksite interventions for weight maintenance or reduction14 by including EBIs that target a wider range of health risk behaviors.

To address these barriers and increase access to EBIs for small and low-wage worksites, the University of Washington and the American Cancer Society partnered to develop HealthLinks. HealthLinks assesses current worksite health promotion practices, provides tailored recommendations for EBIs from the Guide to Community Preventive Services (e.g., increasing access to healthy food options), and provides implementation support from a trained interventionist.2 EBIs can take the form of policies, programs, or communications. Pilot studies conducted on HealthLinks in Washington State demonstrated significant short-term improvements in EBI implementation.15,16 We tested the effect of HealthLinks on worksites’ implementation and maintenance of EBIs. Intervention worksites received (1) HealthLinks, or (2) HealthLinks+, which added worksite wellness committees (to build internal capacity for EBI implementation). We also measured employees’ perceived worksite support for their health.

METHODS

Our eligibility criteria included worksite size (20–200 employees) and industry based on the North American Industry Classification System code (accommodation and food services; arts, entertainment, and recreation; education; health care and social assistance; other services excluding public administration; and retail trade) and location in King County, Washington. We required that at least 20% of employees report to a physical worksite at least once per week, because many of the EBIs take place at the worksite. Because half of new small businesses fail in their first 5 years,17 to minimize loss of enrolled companies to business failure, we required the worksite to have been in business for at least 3 years. Finally, worksites were ineligible if they had a wellness committee (as we intended to randomize worksites to form wellness committees or not, we needed to ensure that none had a wellness committee at baseline).

Recruitment Procedures

The research team used 3 recruitment methods: (1) a list of company meeting size and industry eligibility criteria (n = 661) purchased from Survey Sampling International (Shelton, CT)18 and randomly sequenced to ensure equal chance of contact, (2) a list of eligible worksites provided by a community partner (a health insurer; n = 79), and (3) a relationship-based referral pipeline generated from multiple community partners (n = 111). Research staff initially contacted worksites via telephone. All worksites were contacted up to 15 times before being retired. Of the 851 worksites we attempted to contact, we screened 452 for eligibility. A detailed description of these 3 recruitment approaches is provided in Hammerback et al.19

All worksites interested in hearing more about the study received an in-person visit from 1 or 2 research staff, who provided more details about the study and participation requirements. Employers choosing to enroll in the study signed a memorandum of understanding with the research team; this nonbinding written agreement summarized the study timeline and expectations for the employer and the research team. Worksites were required to complete all baseline measures (described below) to enroll in the study.

Design

The HealthLinks trial was a 3-arm randomized controlled trial with the primary goals of testing HealthLinks’s effectiveness (defined as significantly increasing worksites’ EBI implementation since baseline) in small worksites in low-wage industries and whether adding wellness committees increases HealthLinks’s effectiveness. The 3 arms were (1) HealthLinks, (2) HealthLinks plus wellness committees (HealthLinks+), and (3) delayed control (these worksites had the opportunity to participate in HealthLinks after completing their final follow-up data at 24 months). The primary outcome was the total EBI score, defined as the degree (on a 0%–100% scale) to which participating worksites implemented HealthLinks-promoted EBIs. We also measured employees’ perceived support for their health at their worksite. The secondary outcomes of the study were employees’ health behaviors; findings for secondary outcomes will be presented in a separate article. Worksites participated in the study for 2 years. Employers and employees provided outcome measure data at baseline, 15 months (following delivery of HealthLinks to intervention study arms), and 24 months (the time between follow-ups was a maintenance period with minimal HealthLinks support for the intervention study arms).

Research staff who did not have contact with employers during recruitment and enrollment randomized worksites to 1 of the 3 study arms. We blocked randomization on 3 characteristics: worksite size (20–49 vs 50–200), interventionist (interventionist 1 vs interventionist 2), and industry (group 1: arts, entertainment, and recreation; education; and health care and social assistance vs group 2: accommodation and food services, other services excluding public administration, and retail trade). We categorized industry groups based on our past studies’ findings that some industries are more likely to participate in health promotion studies than are others.7,11 We wanted to ensure that industries likely to be underrepresented (group 2) were evenly distributed across study arms. The statistician (K. C. G. C.) developed a random numbers table based on these blocking criteria, and the data manager (M. K.) assigned enrolled employers to a study arm based on the random numbers table. Research staff (K. H., A. P.) then informed the employer of their assignment.

Intervention

HealthLinks.

The HealthLinks intervention arm protocols are described in detail elsewhere.20 Briefly, HealthLinks consisted of 4 phases: (1) assessment of the employer’s current (baseline) implementation of cancer screening, healthy eating, physical activity, and tobacco cessation EBIs; (2) recommendation of which EBIs to implement based on responses to the assessment; (3) implementation of EBIs; and (4) maintenance of EBIs. Phases 1 and 2 were completed in the first 2 months via in-person meetings with the employer. During phase 3, which took place over the remainder of the 15-month intervention period, the interventionist worked with the employer to focus on implementing 3 to 5 EBIs selected by the employer during phase 2. For example, an employer might draft a stricter tobacco policy, kick off an evidence-based physical activity program, and begin communicating regularly to employees about recommended cancer screenings.

To support EBI implementation, the interventionist offered monthly check-in calls or e-mails and gave the employer toolkits that included checklists, how-to guides, template policies, posters, brochures, and sample e-mail text. The toolkits’ purpose was to make each EBI as turnkey as possible for employers to implement; they also helped standardize how each EBI should be implemented across employers. The employer could also request other support, such as brief presentations for employees about specific EBIs. Phase 4 took place over months 16 through 24. During this maintenance phase, the employer could request assistance from the interventionist, but the interventionist did not initiate contact.

HealthLinks+.

Employers assigned to HealthLinks+ received the same procedures as those described. In addition, the interventionist provided toolkit resources and in-person support to form a worksite wellness committee. The role of the wellness committee was to lead worksite efforts to implement EBIs. Support from the interventionist included attending initial committee meetings, assisting employers with drafting a mission statement or goals, and drafting communications to recruit employees to serve on the committee. Whereas with HealthLinks worksites the interventionist generally interacted with a single point of contact, with HealthLinks+ worksites she partnered with both the main contact and the wellness committee.

Measures

We collected information about the characteristics of the worksite using the Worksite Profile survey. This survey measured worksite industry, size, average annual salary, annual employee turnover, and percentage of workforce employed full time, insured by the employer, and belonging to a union. It also captured workforce demographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, age, and gender) and whether the worksite was the company’s headquarters.

The Implementation Survey characterized worksite implementation of EBIs promoting cancer screening, healthy eating, physical activity, and tobacco cessation. We assessed the primary outcomes for this study using this survey. For each EBI, the survey included 5 to 10 items assessing level of implementation. We combined items using a weighted algorithm to form an implementation score from 0.00 to 1.00 for each EBI, with 0.00 indicating no implementation and 1.00 indicating full implementation.

We collected surveys from employees at baseline, 15 months, and 24 months. The Employee Survey measured employees’ perceived support for specific health behaviors (healthy eating, physical activity, tobacco cessation, and cancer screening) and for living a healthy life overall, and several other measures not relevant to the present article. We offered the surveys in the 4 most common languages in King County—English, Spanish, traditional Chinese, and Vietnamese.21

Data Collection Procedures

We administered the Worksite Profile and Implementation surveys at baseline to our main contact at each worksite either in person or by telephone before randomization. We administered these surveys again at 15 months and 24 months by telephone and each time offered the main contacts a cash incentive ($20) to thank them for their time.

We administered the employee surveys at each worksite at the same intervals. We promoted the survey to employees in advance using the communication channels the employer believed would reach the most employees. We offered all employees who were eligible (able to read 1 of the 4 survey languages, older than 20 years) and willing to participate a small cash incentive ($5) to complete the survey. The survey was anonymous, and employees were not required to participate.

Data Analysis

We performed descriptive statistical analyses, in which we summarized the general characteristics of the participants using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. For Table 1, the P values are for testing equality of means in 3 groups using analysis of variance for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

TABLE 1—

Worksite and Employee Characteristics: Worksite Profile Survey: King County, WA; 2014–2017

| Variable | Control (n = 21), Mean ±SD or No. (%) | HealthLinks (n = 24), Mean ±SD or No. (%) | HealthLinks+ (n = 23), Mean ±SD or No. (%) |

| Company characteristics | |||

| Total employeesa | 75.81 ±47.01 | 71.38 ±43.49 | 77.39 ±53.66 |

| Annual salary, $ | 37 031.00 ±11 369.60 | 36 206.00 ±8655.51 | 43 866.83 ±14 603.15 |

| % Full-time employees | 71.69 ±25.01 | 76.04 ±22.74 | 76.17 ±24.86 |

| % Union membership | 0.00 ±0.00 | 7.05 ±22.40 | 2.70 ±12.50 |

| Company tax status | |||

| Nonprofit | 13 (61.90) | 13 (54.17) | 14 (60.87) |

| For profit | 8 (38.10) | 11 (45.83) | 9 (39.13) |

| Company offers health insurance to employees | 19 (90.48) | 24 (100.00) | 22 (95.65) |

| Company is self-insured | 0 (0.00) | 1 (4.17) | 1 (4.35) |

| Employees eligible for health insurance | 85.56 ±17.04 | 84.17 ±16.96 | 81.41 ±17.53 |

| Employees enrolled in health insurance | 82.21 ±17.51 | 81.71 ±16.08 | 81.41 ±17.53 |

| Industryb | |||

| Accommodation and food services | 3 (14.29) | 2 (8.33) | 2 (8.70) |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (8.70) |

| Educational services | 3 (14.29) | 2 (8.33) | 2 (8.70) |

| Health care and social assistance | 8 (38.10) | 12 (50.00) | 11 (47.83) |

| Other (except public administration) | 7 (33.33) | 3 (12.50) | 3 (13.04) |

| Retail trade | 0 (0.00) | 5 (20.83) | 3 (13.04) |

| Employee demographics | |||

| Age, y | |||

| 18–44 | 65.21 ±20.86 | 66.24 ±21.44 | 64.14 ±18.33 |

| 45–64 | 32.31 ±19.93 | 29.86 ±20.21 | 31.27 ±16.31 |

| ≥ 65 | 2.48 ±2.82 | 3.90 ±4.05 | 4.59 ±6.43 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 25.50 ±15.84 | 41.55 ±25.10 | 34.50 ±21.13 |

| Female | 74.49 ±15.84 | 58.41 ±25.04 | 65.50 ±21.13 |

| Race | |||

| White | 64.53 ±22.14 | 66.14 ±28.56 | 66.95 ±27.89 |

| Black | 11.07 ±14.98 | 8.33 ±10.19 | 9.85 ±16.07 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.29 ±2.81 | 1.65 ±6.68 | 0.53 ±1.02 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 13.47 ±9.53 | 15.75 ±22.84 | 11.15 ±19.93 |

| Multiracial | 3.79 ±4.84 | 3.81 ±5.63 | 4.95 ±6.84 |

| Other | 4.07 ±5.06 | 5.10 ±13.83 | 3.45 ±6.55 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic/Latino | 10.23 ±12.68 | 13.45 ±19.39 | 14.64 ±19.99 |

| Languagec | |||

| English | 96.85 ±6.52 | 96.04 ±9.64 | 91.27 ±18.26 |

| Spanish | 5.87 ±5.69 | 9.18 ±11.67 | 24.00 ±24.27 |

| Chinese | 3.50 ±3.73 | 1.00 ±2.00 | 2.60 ±3.71 |

| Vietnamese | 1.00 ±1.41 | 1.83 ±4.02 | 2.50 ±5.00 |

| Other | 4.60 ±9.21 | 0.40 ±0.89 | 8.50 ±12.02 |

Note. Study population n = 68. Worksite characteristics drawn from baseline measures. No variables differed significantly between arms.

One worksite reported < 200 employees at screening and then reported 239 employees after enrollment. We allowed them to participate in the trial; dropping them from the study analyses did not result in any meaningful changes to results.

Industry as identified by North American Industry Classification System code.

Total exceeds 100% because of report of bilingual employees speaking both English and another language.

For both the primary and the secondary outcomes, we analyzed the longitudinal trajectories of outcomes over 3 time points. Because data from the same worksite are correlated at those 3 time points, and data from employees within a single worksite are correlated, we analyzed the data using generalized estimating equations with an exchangeable correlation structure. We used a robust standard error to ensure proper inference should the working correlation structure be misspecified. All models included block randomization variables (size and industry). For Tables 2 and 3, the P values are for testing equality of mean outcomes comparing the intervention groups with the control group after intervention, at both 15 and 24 months, using the Wald test following models fit from generalized estimating equations. All analyses were performed in Stata version 14.22

TABLE 2—

Evidence-Based Interventions Implementation Scores by Wave and Arm: King County, WA; 2014–2017

| Baseline Score ±SD |

15-Month Score ±SD |

24-Month Score ±SD |

||||||||

| Policy, Program, Communication | Control | HealthLinks | HealthLinks+ | Control | HealthLinks | HealthLinks+ | Control | HealthLinks | HealthLinks+ | Pa |

| Policy | ||||||||||

| Tobacco | 0.67 ±0.27 | 0.67 ±0.24 | 0.71 ±0.22 | 0.79 ±0.23 | 0.78 ±0.22 | 0.83 ±0.19 | 0.85 ±0.19 | 0.79 ±0.23 | 0.84 ±0.019 | .77 |

| Food | 0.40 ±0.017 | 0.21 ±0.23 | 0.34 ±0.21 | 0.42 ±0.21 | 0.37 ±0.027 | 0.50 ±0.21 | 0.39 ±0.23 | 0.36 ±0.27 | 0.50 ±0.22 | .07 |

| Beverage | 0.66 ±0.25 | 0.69 ±0.31 | 0.64 ±0.33 | 0.69 ±0.20 | 0.80 ±0.22 | 0.74 ±0.32 | 0.68 ±0.25 | 0.81 ±0.27 | 0.76 ±0.28 | .19 |

| Physical activity | 0.19 ±0.12 | 0.17 ±0.10 | 0.17 ±0.09 | 0.24 ±0.17 | 0.20 ±0.13 | 0.25 ±0.14 | 0.24 ±0.17 | 0.21 ±0.12 | 0.20 ±0.14 | .8 |

| Total | 0.48 ±0.10 | 0.43 ±0.13 | 0.47 ±0.13 | 0.54 ±0.11 | 0.54 ±0.12 | 0.58 ±0.14 | 0.54 ±0.12 | 0.54 ±0.12 | 0.57 ±0.14 | .22 |

| Program | ||||||||||

| Physical activity | 0.07 ±0.23 | 0.03 ±0.13 | 0.05 ±0.18 | 0.10 ±0.24 | 0.67 ±0.41 | 0.64 ±0.45 | 0.08 ±0.25 | 0.24 ±0.36 | 0.32 ±0.42 | < .001 |

| Communication | ||||||||||

| Quitline | 0.04 ±0.18 | 0.10 ±0.29 | 0.03 ±0.13 | 0.04 ±0.16 | 0.31 ±0.39 | 0.19 ±0.33 | 0.07 ±0.21 | 0.27 ±0.36 | 0.08 ±0.22 | < .001 |

| Tobacco | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.03 ±0.13 | 0.03 ±0.13 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.14 ±0.32 | 0.05 ±0.17 | 0.03 ±0.14 | 0.15 ±0.30 | 0.03 ±0.13 | .15 |

| Beverage | 0.04 ±0.18 | 0.03 ±0.17 | 0.07 ±0.22 | 0.15 ±0.32 | 0.30 ±0.37 | 0.41 ±0.41 | 0.16 ±0.34 | 0.17 ±0.30 | 0.34 ±0.40 | .06 |

| Healthy eating | 0.10 ±0.26 | 0.07 ±0.23 | 0.09 ±0.23 | 0.03 ±0.14 | 0.47 ±0.38 | 0.51 ±0.43 | 0.12 ±0.30 | 0.27 ±0.37 | 0.35 ±0.41 | < .001 |

| Physical activity | 0.03 ±0.10 | 0.08 ±0.19 | 0.03 ±0.09 | 0.08 ±0.16 | 0.49 ±0.31 | 0.49 ±0.40 | 0.11 ±0.24 | 0.16 ±0.25 | 0.36 ±0.39 | < .001 |

| Breast, cervical, colorectal free screening program | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.08 ±0.22 | 0.10 ±0.25 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.03 ±0.13 | 0.03 ±0.13 | .03 |

| Cancer | 0.03 ±0.14 | 0.03 ±0.14 | 0.10 ±0.27 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.29 ±0.36 | 0.28 ±0.39 | 0.00 ±0.00 | 0.17 ±0.31 | 0.24 ±0.37 | < .001 |

| Total | 0.04 ±0.11 | 0.05 ±0.14 | 0.05 ±0.11 | 0.05 ±0.06 | 0.33 ±0.19 | 0.31 ±0.24 | 0.07 ±0.13 | 0.19 ±0.20 | 0.23 ±0.026 | < .001 |

| Total score | 0.20 ±0.11 | 0.17 ±0.08 | 0.19 ±0.09 | 0.23 ±0.10 | 0.51 ±0.18 | 0.51 ±0.20 | 0.23 ±0.11 | 0.33 ±0.18 | 0.37 ±0.22 | < .001 |

Note. n = 68 worksites. Scores are implementation scores; range = 0.0–1.0.

P value reflects testing whether the average outcome in the intervention groups are different from the control group at both 15 and 24 months after the intervention.

TABLE 3—

Employees’ Perception of Worksite Support for Healthy Behavior by Arm and Wave: King County, WA; 2014–2017

| Baseline (n = 2678), Mean ±SD |

15 Months (n = 2613), Mean ±SD |

24 Months (n = 2328), Mean ±SD |

||||||||

| Item | Control (n = 792) | HealthLinks (n = 945) | HealthLinks+ (n = 941) | Control (n = 750) | HealthLinks (n = 959) | HealthLinks+ (n = 904) | Control (n = 712) | HealthLinks (n = 794) | HealthLinks+ (n = 822) | P |

| My worksite supports me in trying to eat healthy foods and drink healthy beverages. | 3.22 ±0.94 | 3.15 ±1.05 | 3.27 ±0.97 | 3.24 ±0.93 | 3.42 ±0.97 | 3.61 ±0.88 | 3.26 ±0.98 | 3.39 ±0.96 | 3.57 ±0.89 | .003 |

| My worksite supports me in trying to live an active life. | 3.18 ±0.90 | 3.16 ±1.03 | 3.19 ±0.96 | 3.17 ±0.87 | 3.43 ±0.99 | 3.61 ±0.88 | 3.17 ±0.92 | 3.34 ±0.96 | 3.55 ±0.92 | < .001 |

| My worksite supports me in trying to quit using tobacco.a | 3.57 ±1.34 | 3.50 ±1.44 | 3.45 ±1.29 | 3.31 ±1.33 | 3.72 ±1.32 | 3.71 ±1.10 | 3.77 ±1.23 | 3.66 ±1.18 | 3.60 ±1.34 | .25 |

| My worksite supports me in trying to obtain the recommended cancer screenings. | 2.75 ±0.96 | 2.69 ±1.07 | 2.80 ±0.99 | 2.74 ±0.97 | 2.83 ±0.99 | 2.92 ±0.96 | 2.71 ±1.02 | 2.79 ±1.01 | 2.97 ±0.95 | .032 |

| Overall, my worksite supports me in living a healthier life. | 3.35 ±0.88 | 3.33 ±1.03 | 3.34 ±0.95 | 3.39 ±0.86 | 3.56 ±0.94 | 3.74 ±0.84 | 3.36 ±0.94 | 3.51 ±0.95 | 3.68 ±0.85 | < .001 |

Note. All items were answered using Likert-type scales: 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

These analyses were restricted to current tobacco users.

RESULTS

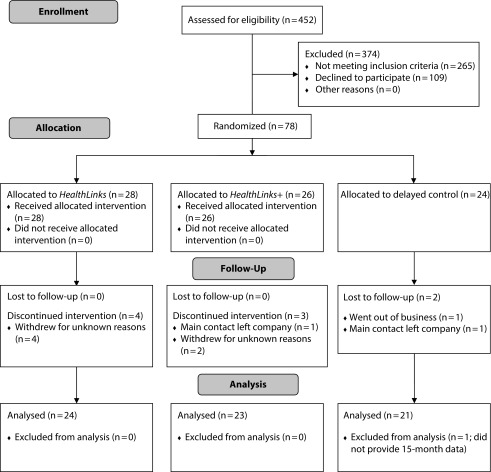

Of the 187 eligible employers, 78 (41.7%) agreed to participate in the trial and provided baseline data; these worksites’ characteristics are described elsewhere.20 In this article, we present data for 68 worksites that completed the entire trial and provided 24-month follow-up data (Figure 1 presents a CONSORT [Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials] diagram). All 68 worksites participated in the employee surveys at baseline. Five worksites did not administer the final follow-up employee surveys; we included Employee Survey data from the 63 worksites that administered employee surveys at all 3 time points in our analyses.

FIGURE 1—

CONSORT Flow Diagram of the Randomized Controlled Trial: King County, WA; 2014–2017

Note. CONSORT = Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics as reported by the worksites’ main contact for the study (usually the human resources manager). Twenty-one worksites were randomized to the control arm, 24 to the HealthLinks arm, and 23 to the HealthLinks+ arm. On average, worksites had 75 employees (SD = 48), with an average annual salary of $39 041 (the average annual salary in King County was $72 764 in 2015).23 The majority of worksites (59%) were not for profit, and almost all (96%) offered health insurance to their employees. More than half of the worksites were from the education or health care and social assistance industries.

The worksites’ main contacts reported demographic characteristics for their entire workforce (Table 1). Race and ethnicity were similar to overall race and ethnicity for King County, with our study population including a higher proportion of African Americans (10%) and Latinos (13%) than did King County (7% and 10%, respectively) and a smaller proportion of Asian Americans and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders (13%) than did King County (19%).24

Evidence-Based Interventions Implementation

Table 2 presents individual EBI scores as well as scores for EBIs grouped by type (policy, program, and communication). Overall, EBI implementation scores for policies, programs, or communications at baseline were similar and low, with total scores averaging 19% across all worksites. The exception was food policy implementation; control worksites had a higher score (40%) than did HealthLinks (21%) or HealthLinks+ (34%) worksites at baseline (P = .009). At both 15 and 24 months, EBI implementation increased significantly in both intervention arms for program, communication, and total EBI scores (all P < .001). Program scores increased the most at 15 months, from 3% to 67% in the HealthLinks arm and from 5% to 64% in the HealthLinks+ arm. At 24 months, program, communication, and total EBI scores had decreased in both intervention arms but were still higher than the control arm scores. By contrast, policy scores increased in all study arms, largely driven by increases in tobacco policy; neither intervention arm showed a significant impact on policy EBI scores compared with control worksites (P = .22).

Employee Perceptions

We received 2678 employee surveys at baseline, 2613 at 15 months, and 2328 at 24 months. Response rates for all employees ranged from 51% (24 months) to 58% (baseline); response rates for employees at the worksite for 50% or more of the time ranged from 71% (24 months) to 81% (baseline; we calculated this second response rate because surveys were administered to employees at the physical worksite). Compared with employees in control worksites, employees in the intervention worksites perceived increased worksite support for consuming healthy food and beverages, “living an active life,” getting recommended cancer screenings, and “living a healthier life” at 15 and 24 months (Table 3; all P < .001). We restricted analyses for perceived support for tobacco cessation to employees who reported current tobacco use; there were no significant differences in perceived support for tobacco cessation across study arms (Table 3; P = .25).

Forming and Maintaining Wellness Committees

We conducted an ancillary analysis restricted to the 52 worksites that formed and maintained wellness committees in alignment with their assignment to study arm. Eleven worksites in the HealthLinks+ arm either never formed a wellness committee or were unable to sustain it for 24 months. A few worksites in the HealthLinks arm reported having a wellness committee at either 15- or 24-month follow-up (n = 5). In this restricted analysis, worksites in the HealthLinks+ arm had higher EBI implementation scores at 15 and 24 months (64% and 54%, respectively) than did worksites in the HealthLinks arm (51% and 31%, respectively; P ≤ .001).

DISCUSSION

The HealthLinks intervention significantly improved EBI implementation in small worksites from low-wage industries. These employers have limited capacity for health promotion and many of their employees are at risk for health disparities. Both HealthLinks intervention groups significantly improved EBI implementation at 15 months; at 24 months, after a 9-month maintenance period, their implementation scores decreased but were still higher than those of control worksites. When we limited our analysis of EBI implementation to worksites that complied with their wellness committee assignment, we saw significantly higher implementation of EBIs in the HealthLinks+ arm at both 15 and 24 months and less backsliding at 24 months. However, only 52% of the worksites assigned to the HealthLinks+ arm were able to form and sustain wellness committees for 24 months.

Employee survey data validated employers’ reports of EBI implementation. Employees of intervention worksites reported increased support for healthy eating, physical activity, cancer screening, and their overall health over the course of the study. In qualitative studies with similar employee populations, we found that employees generally do not perceive that their employer supports their health and would welcome that support.25,26 Our previous research also suggests that employees’ perceived worksite support for their overall health and physical activity is associated with presenteeism, such that higher levels of perceived support are associated with lower levels of presenteeism even after controlling for demographic characteristics and health behavior.27

Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations. First, there was a major implementation challenge during the trial: 1 of the HealthLinks interventionists could not continue her work on the project. The worksites served by this interventionist experienced delays as we hired and trained a new interventionist. We experienced turnover with our primary contacts in a significant minority of our worksites (38%), and this turnover often created challenges with continuing implementation in the intervention groups and with completing measures in all groups. We recruited 78 worksites and were able to maintain 68 through the final follow-up. Although losing 10 worksites is a limitation, we also view retaining 87% of our original participants as a strength, especially in light of the challenges we have described.

We conducted the employee surveys as serial cross-sectional surveys at the 3 measurement time points; we were able to see a snapshot of each worksite’s employees at each time point, but we were unable to track individual employees’ perceptions of support over time. This meant that we had different groups of employees at each time point, as these are high turnover worksites.

This study also has several strengths. We used a rigorous randomized design to test 2 different versions of HealthLinks, and we included a maintenance period to see whether EBI implementation “sticks” after HealthLinks ends. Our findings suggest that HealthLinks is effective with and without a wellness committee, especially in the short term. Our findings also suggest that wellness committees may help with initial implementation and with maintaining implementation after formal HealthLinks support ends. However, the number of worksites in the wellness committee arm who failed to form or maintain a wellness committee suggests that many worksites found starting and maintaining these committees very challenging. Another possibility is that maintaining the wellness committee was an indicator of worksites’ commitment to implementing EBIs, rather than a facilitator. It is also possible that worksites in some industries may be more predisposed to form wellness committees than are others; all 5 of the worksites in the standard HealthLinks arm that formed wellness committees were in the health care and social assistance industry. By contrast, the 11 worksites in the wellness committee arm that did not form or maintain wellness committees were spread across 5 different industries (including health care and social assistance).

We were able to recruit and serve a high-need population of worksites that is underserved in terms of evidence-based workplace wellness programs and opportunities. Our employee population had salaries lower than the county median salary, suggesting that partnering with small and low-wage worksites can be an effective strategy for reaching populations experiencing health disparities.

Directions for Future Research

We discuss 2 directions for future research related to HealthLinks and other programs to help small worksites start or improve wellness programs. First, our findings suggest that wellness committee implementation may support EBI implementation and that many worksites struggled to form or maintain wellness committees. We need to learn more about (1) the essential aspects of wellness committees that support EBI implementation versus the aspects or tasks that are less helpful, and (2) how to support worksites to form and maintain wellness committees. This line of research may be especially important for helping worksites maintain EBIs after active implementation support ends.

The second area of future research involves strategies for effectively disseminating HealthLinks. Our primary contacts from the worksites were clear that the interventionist is a key part of HealthLinks’s effectiveness; most did not believe that a self-directed approach (e.g., just giving the employers our toolkits or a Web site) would have worked for them. We are currently exploring models of training and supporting HealthLinks interventionists in a variety of settings to expand the program’s reach to other counties and states.

Public Health Implications

The HealthLinks trial shows that small worksites in low-wage industries can adopt and implement EBIs, potentially benefitting employees who likely have low wages and face health disparities. This is not a light-touch intervention; these worksites need tools (which can be disseminated electronically) but also real-time assistance and nudging to implement EBIs. Small worksites do not have slack resources; we doubt that attempting to scale up HealthLinks via a profit-driven model that costs employers a substantial amount of money would reach underserved worksites and employees. We are exploring public and nonprofit partnerships to scale up HealthLinks, which will be rebranded as Connect to Wellness, and reach more worksites to improve their support for their employees’ health.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant 5R01CA160217). Additional support was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center cooperative agreement U48DP005013).

The authors would like to thank the American Cancer Society and the employers and employees who participated in the study. The authors would also like to thank Riki Mafune, Daron Ryan, and Sara Teague for their work with employers in this study.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The University of Washington institutional review board reviewed and approved all study materials and procedures.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-Term Trends in Health. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Task Force on Community Preventative Services. The community guide. 2018. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 3.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force statistics from the current population survey. 2018. Available at: https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS12300000. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 4.McPeck W, Ryan M, Chapman LS. Bringing wellness to the small employer. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(5):1–10. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.23.5.tahp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCoy K, Stinson K, Scott K, Tenney L, Newman LS. Health promotion in small business: a systematic review of factors influencing adoption and effectiveness of worksite wellness programs. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(6):579–587. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linnan L, Bowling M, Childress J et al. Results of the 2004 National Worksite Health Promotion Survey. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1503–1509. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hannon PA, Garson G, Harris JR, Hammerback K, Sopher CJ, Clegg-Thorp C. Workplace health promotion implementation, readiness, and capacity among midsize employers in low-wage industries: a national survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(11):1337–1343. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182717cf2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris JR, Hannon PA, Beresford SA, Linnan LA, McLellan DL. Health promotion in smaller workplaces in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:327–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris JR, Huang Y, Hannon PA, Williams B. Low-socioeconomic status workers: their health risks and how to reach them. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(2):132–138. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182045f2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macy G, Watkins C. A mixed methods analysis of workplace health promotion at small, rural workplaces. Am J Health Stud. 2016;31(4):232–242. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannon PA, Hammerback K, Garson G, Harris JR, Sopher CJ. Stakeholder perspectives on workplace health promotion: a qualitative study of midsized employers in low-wage industries. Am J Health Promot. 2012;27(2):103–110. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110204-QUAL-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linnan L, Weiner B, Graham A, Emmons K. Manager beliefs regarding worksite health promotion: findings from the Working Healthy Project 2. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(6):521–528. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.6.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stiehl E, Shivaprakash N, Thatcher E et al. Worksite health promotion for low-wage workers: a scoping literature review. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(2):359–373. doi: 10.1177/0890117117728607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beresford SA, Locke E, Bishop S et al. Worksite study promoting activity and changes in eating (PACE): design and baseline results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(suppl 1):4S–15S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laing SS, Hannon PA, Talburt A, Kimpe S, Williams B, Harris JR. Increasing evidence-based workplace health promotion best practices in small and low-wage companies, Mason County, Washington, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannon PA, Hammerback K, Teague S. Employees’ perceptions of evidence-based approaches to wellness in low-wage industries. Paper presented at: Annual meeting of the American Public Health Association. New Orleans, LA; November 17, 2014.

- 17.US Small Business Administration. Advocacy: the voice of small business in government. 2014. Available at: https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/FAQ_March_2014_0.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2015.

- 18. Dynata. Available at: https://www.surveysampling.com. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 19.Hammerback K, Hannon PA, Parrish AT, Allen C, Kohn MJ, Harris JR. Comparing strategies for recruiting small, low-wage worksites for community-based health promotion research. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(5):690–696. doi: 10.1177/1090198118769360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannon PA, Hammerback K, Allen CL et al. HealthLinks randomized controlled trial: design and baseline results. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;48:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felt C. King County’s changing demographics: a view of our increasing diversity. Seattle, WA: King County Office of Performance, Strategy, and Budget; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

- 23.Washington State Office of Financial Management. Average wages by county. 2017. Available at: https://www.ofm.wa.gov/washington-data-research/statewide-data/washington-trends/economic-trends/washington-and-us-average-wages/average-wages-county-map. Accessed October 31, 2018.

- 24.US Census Bureau. QuickFacts: King County, Washington. 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/kingcountywashington. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 25.Allen CL, Hammerback K, Harris JR, Hannon PA, Parrish AT. Feasibility of workplace health promotion for restaurant workers, Seattle, 2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E172. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammerback K, Hannon PA, Harris JR, Clegg-Thorp C, Kohn M, Parrish A. Perspectives on workplace health promotion among employees in low-wage industries. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(6):384–392. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130924-QUAL-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Hannon PA, Laing SS et al. Perceived workplace health support is associated with employee productivity. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(3):139–146. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.131216-QUAN-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]