Abstract

Objectives. To determine which front-of-package label (out of 5 formats) is most effective at guiding consumers toward healthier food choices.

Methods. Respondents from Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States took part in the Front-of-Pack International Comparative Experiment between April and July 2018. Respondents were shown foods of varying nutritional quality (with no label on package) and selected which they would be most likely to purchase. The same choice sets were then shown again with 1 of 5 randomly allocated labels on package (Health Star Rating (HSR), Multiple Traffic Lights (MTL), Nutri-Score, Reference Intakes, or Warning Label). We calculated an improvement score (from 11 100 valid responses) to identify the extent to which the labels produced healthier choices.

Results. The most effective labels were the Nutri-Score and the MTL (mean improvement score = 0.09; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.07, 0.11), then the Warning Label (0.06; 95% CI = 0.04, 0.08), the HSR (0.05; 95% CI = 0.03, 0.07), and lastly the Reference Intakes (0.04; 95% CI = 0.02, 0.04).

Conclusions. Well-designed, salient, and intuitive front-of-package labels can be effective on a global scale. Their impact is not bound to the country from which they originate.

Poor nutritional quality of diet is recognized as a major risk factor for obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and some cancers.1 These chronic diseases are largely preventable, and implementing strategies to improve consumers’ diets at the population level is a well-supported, cost-effective prevention approach.2 One such strategy that has received considerable policy attention is the provision of clear nutrition information on food products to assist people in making healthier dietary choices.3 In its Global Action Plan, the World Health Organization recommends the use of nutrition labels as a method for facilitating healthy food choices and encouraging manufacturers to engage in reformulation.1 Many countries have implemented back-of-pack nutrition information systems to provide consumers with information about the energy and nutrients contained within foods. Identified limitations of these systems relate to a lack of visibility and the complexity of the information provided.4,5 Front-of-pack labels (FoPLs) are proposed to be an effective complementary form of information provision because of their ability to provide more visible and simplified nutrition information.6 Experimental evidence shows that people are more likely to attend to and make use of FoPLs than more detailed back-of-pack nutrition information.4,5,7,8

Given that various FoPL formats exist around the world, ranging from simple icons to detailed representations of individual nutrients,9 it is important to determine (1) which, if any, are effective in modifying consumers’ choices and (2) which elements of FoPLs are likely to enhance their effectiveness. Most FoPLs can be classified as reductive or interpretive. Reductive labels (such as Reference Intakes) present nutrition information with little additional interpretation, whereas interpretive labels provide consumers with some guidance about the healthiness of the food (e.g., through the use of colors or symbols). As shown in Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), interpretive FoPLs can be divided into those that (1) provide information at the level of the individual nutrient (known as nutrient-specific FoPLs, such as Multiple Traffic Lights [MTL] and Warning Labels), (2) feature a summary indicator computed on the basis of the nutritional composition of the food (e.g., the Nutri-Score), or (3) are hybrid labels encompassing both forms of information (e.g., the Health Star Rating [HSR]). The present study includes a reductive label and all 3 forms of interpretive labels to assess which is likely to be most effective in encouraging healthier food choices.

Research suggests that reductive labels are harder to understand and as a result interpretive FoPLs tend to be preferred by consumers.10,11 In addition, numerous reviews have concluded that consumers make healthier choices when using interpretive rather than reductive labels.10,12–14 Much of this work has focused on comparing versions of the Reference Intakes and the MTL label because of the longer history of these FoPLs, although more recent work has included newer FoPLs, such as those featuring summary indicators.15–22 Evidence suggests that summary indicator FoPLs may be more effective than nutrient-specific FoPLs in guiding consumers toward healthy choices. Studies on the Nutri-Score (adopted in 2017 in France) found it was noticed faster and was easier to understand than the MTL and Reference Intakes, and that it led participants to select products of higher nutritional quality.23 The HSR (which first appeared on food packs in Australia in 2014) has been shown to lead to healthier choices compared with the MTL and Reference Intakes.20,21 The Warning Label (implemented in 2016 in Chile) has been found to outperform the Reference Intakes in terms of healthiness of food choices and reaction time tasks (e.g., timed identification of foods high in a target nutrient).15 Studies comparing the MTL and the Warning Label indicate that these 2 FoPLs produce similar outcomes in terms of ability to identify the healthiest alternative from a choice set.15,18,19

As more countries consider implementing FoPLs,24 it is timely to assess whether this form of nutrition intervention is effective in changing behavior and whether some FoPL designs are more effective than others within and across different cultural contexts. Although there is compelling evidence that interpretive FoPLs are more effective than reductive FoPLs, the introduction of new interpretive FoPLs, the lack of comprehensive comparisons of different interpretative FoPLs, and the limited cross-cultural work all result in the need for large-scale, international studies involving different kinds of label formats to provide a more complete and up-to-date picture of FoPL effectiveness.10,12,24 As such, the main aim of the present study was to identify the extent to which 5 different FoPLs (HSR, MTL, Nutri-Score, Reference Intakes, and Warning Label) are effective in favorably influencing consumers’ food choices. We employed an experimental design with randomized interventions across 12 countries: Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

METHODS

This study was part of a larger research project investigating the effects of FoPLs on consumers’ food-related decisions (the Front-of-Pack International Comparative Experiment). In compliance with Transparency and Openness Promotion Standards, the survey instrument, power calculation, and syntax for analyses are available in online Appendixes A, B, and C. Data will be provided upon request (from author C. J.). The study protocol can be found at http://www.ANZCTR.org.au/ACTRN12618001221246.aspx.

Participants

An International Organization for Standardization (ISO)-accredited international Web panel provider (PureProfile) was used to source survey respondents from the 12 countries. Various methods, including online and mass media advertising and word-of-mouth referrals, were used to recruit panel members. The researchers informed participants that “In this survey, you will be presented with a variety of food products and will be asked to make judgements about these products.” They were therefore aware that the survey related to food but not that the specific focus was on FoPLs. The Web panel provider applied quotas to yield a sample that was evenly split according to gender, age (18–30 years, 31–50 years, > 50 years), and income level (low, medium, and high) within countries and across the entire sample.

We calculated income brackets for each country by first estimating the median household income within each country (from various national statistical databases) and creating a bracket of ±33% around this figure. This represented the “medium” income band. We considered anything below or above this figure low or high income, respectively. We set the same age, gender, and income quotas for all countries, despite varying national demographic profiles, to ensure that there was wide variation among participants across these demographic variables. Panel members were not eligible to participate if they fell within a demographic group for which the age, gender, or income quota had already been filled. Survey respondents were also excluded if they reported that they “never” purchased 2 or more of the 3 food categories included in the study (breakfast cereals, cakes, and pizzas).

All respondents completed the survey on a desktop or tablet rather than a mobile device to ensure adequate visibility of the stimuli. The researchers set a target of 1000 respondents (see online Appendix A for a power calculation for each country).

Stimuli

In the present study, we used fictional food brands to eliminate confounding effects of brand associations, loyalty, or familiarity. We chose the 3 food types included in the study because they are consumed in all 12 countries (and hence are familiar), are highly variable in nutritional quality within product categories (thereby facilitating healthiness rankings), are eaten for different reasons, and have been used in previous studies.16,21,25,26 Each choice set comprised food from broad product categories (e.g., cakes) rather than specific food types (e.g., cheesecakes). A graphic designer created images of mock food packs (featuring a fictional brand “Stofer”) to prevent past experience with real brands from affecting respondents’ judgments. We provided a zoom function that enabled respondents to magnify sections of the package—including the nutrition label—by hovering over the image. A screenshot from the study is shown in online Figure B.

The 3 nutritional profiles created within each food category represented lower, intermediate, and higher nutritional quality. This resulted in 9 base mock packs that we then replicated to feature each of the 5 FoPLs. The nutritional information for each product is provided in Table 1. An example of 1 product set and the 5 associated FoPLs is shown in online Figure C. Native speakers translated the wording of the survey items and the words used on the FoPLs into 1 of the primary languages of the country where the respondent resided. English was used in Australia, Canada, Singapore, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Spanish was used in Argentina, Mexico, and Spain. Danish was used in Denmark, French in France, and German in Germany. The English version of the survey instrument is provided in online Appendix B.

TABLE 1—

Nutritional Information for All Products (Across All 12 Countries): April–July 2018

| Nutrient Values per 100 g |

||||||

| Product | Energy (kcal) | Energy (kJ) | Fat (g) | Saturated fat (g) | Sugars (g) | Sodium (mg) |

| Cornflakes | 378 | 1582 | 1 | < 1 | 8 | 390 |

| Coco Krisps | 387 | 1638 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 295 |

| Coco Full | 452 | 1892 | 16 | 4 | 29 | 445 |

| Quattro Stagioni | 191 | 801 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 335 |

| Regina pizza | 231 | 968 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 689 |

| Quattro Fromaggi | 274 | 1148 | 17 | 9 | 1 | 594 |

| Cheesecake | 217 | 908 | 7 | 3 | 18 | 110 |

| Brownies | 463 | 1938 | 27 | 4 | 34 | 228 |

| Cake | 422 | 1768 | 24 | 16 | 27 | 274 |

Note. The 12 study countries were Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Procedure

Respondents aged 18 years and older completed an online survey. After providing information on gender, age, household composition, and household income (for screening purposes), respondents indicated their education level and rated their nutrition knowledge and diet quality.

The survey then presented respondents with 3 stimulus sets, 1 from each food category (breakfast cereal, cake, and pizza). Each stimulus set contained the 3 product variations from a food category (e.g., 3 different pizzas) without any FoPLs. The survey asked, “Assuming you were interested in purchasing this type of food, which food product would you buy?” They could select 1 of the 3 food products shown or they could select “I wouldn’t buy any of these products.”

After the selection task was undertaken in the absence of FoPLs, respondents were randomly assigned to 1 of the 5 FoPL conditions and shown the same stimuli, this time with an FoPL on the mock packages. Respondents were not told in advance that the same stimulus sets would be repeated or that FoPLs would appear. Throughout the experiment, the order of presentation of the stimulus sets and the order of individual products within each set were randomized to avoid order effects. We chose a repeated measures design to increase the external validity of the study, increase statistical power, and eliminate any error variance due to individual differences.27

Statistical Analyses

We coded the product chosen from each stimulus set with a score of 3 (higher nutritional quality product), 2 (intermediate nutritional quality product), or 1 (lower nutritional quality product). We calculated an improvement score for each food by subtracting the choice score in the no-FoPL condition from the choice score in the FoPL condition. Thus, to be included in analyses measuring improvement in choice, respondents needed to have selected a product in both the no-FoPL and FoPL conditions for at least 1 category of food. We then calculated an overall score for each respondent by averaging improvement scores across the 3 food products. Averaging (rather than summing) the improvement scores meant that respondents could be included in analyses if they answered at least 1 pair (no FoPL, FoPL) of food choices.

We analyzed data in SPSS version 24 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The dependent variable was the improvement in the healthiness of the chosen product and the independent variable was FoPL condition. We controlled for gender, age, educational level, income level, involvement in grocery shopping, perceived diet quality, and perceived nutritional knowledge by entering them as covariates. We calculated the parameter estimates as Β values (with associated significance values) for each FoPL, with Reference Intakes as the reference category. We set the significance threshold at P < .0125 after applying a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (4 comparisons within each ANCOVA). We then plotted the estimated marginal means for each FoPL (and 95% confidence intervals) produced by the ANCOVA to permit comparison across all FoPLs. We ran ANCOVAs on the data combined across all countries and separated by country. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess FoPL effectiveness among respondents who were capable of improving their choices (i.e., by including only respondents who selected an unhealthy or moderately healthy product in the no-FoPL condition). The syntax for the ANCOVA is available in online Appendix C. Data will be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

RESULTS

Between April and July 2018, a total of 12 015 respondents completed the survey, resulting in 36 045 possible “no FoPL–FoPL” choice pairs. After we removed data for choice pairs in which respondents reported that they “never” purchased that food (n = 1179; 3% of all choice pairs) and then removed cases in which the respondent opted out of making a choice in 1 or both choice pairs (n = 6691; 19%), the number of remaining valid choice pairs was 28 175 (78%). However, because responses were averaged across the 3 foods, respondents only needed to complete at least 1 food choice pair to be included in analyses. This resulted in 8% (n = 915) of respondents being excluded from analyses because they had not provided valid data across all 3 choice pairs.

The characteristics of the sample members providing a valid response are described in online Table A. From this sample of valid respondents (n = 11 100), 96% described themselves as being the primary or shared primary grocery shopper in the household, 75% declared having a mostly or very healthy diet, and 76% reported being at least somewhat knowledgeable about nutrition.

Table 2 shows the patterns of improvement, deterioration, or lack of change seen across the no-FoPL–FoPL choice pairs for the overall data and by FoPL condition. For the majority of choice pairs (82%), food selection remained unchanged from the no-FoPL to FoPL condition. Improvements in the healthiness of products chosen occurred for 12% of choice pairs and a deterioration occurred for 6%. There were differences according to FoPL type, with exposure to the Nutri-Score and MTL resulting in the greatest proportions of healthier choices (14%).

TABLE 2—

Patterns of Change in Food Choices (Across All 12 Countries) Between the No-FoPL and FoPL Scenario: April–July 2018

| % of Participants Who Switched, by FoPL |

|||||||

| No-FoPL Condition Outcome | FoPL Condition Outcome | All FoPLs | HSR | MTL | Nutri-Score | Reference Intake | Warning Label |

| Unhealthy choice | Switch to moderately healthy | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| Switch to healthy | 4.1 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 3.9 | |

| Moderately healthy choice | Switch to unhealthy | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Switch to healthy | 5.6 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 5.0 | |

| Healthy choice | Switch to unhealthy | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

| Switch to moderately healthy | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.7 | |

| No change | … | 81.8 | 83.7 | 80.3 | 79.9 | 82.1 | 82.9 |

Note. FoPL = Front-of-Package Label; HSR = Health Star Rating; MTL = Multiple Traffic Lights. Data shown are for 28 175 valid choice pairs (where a choice was made in both the no-FoPL and FoPL scenario) out of a total 36 045 potential choice pairs. The 12 study countries were Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

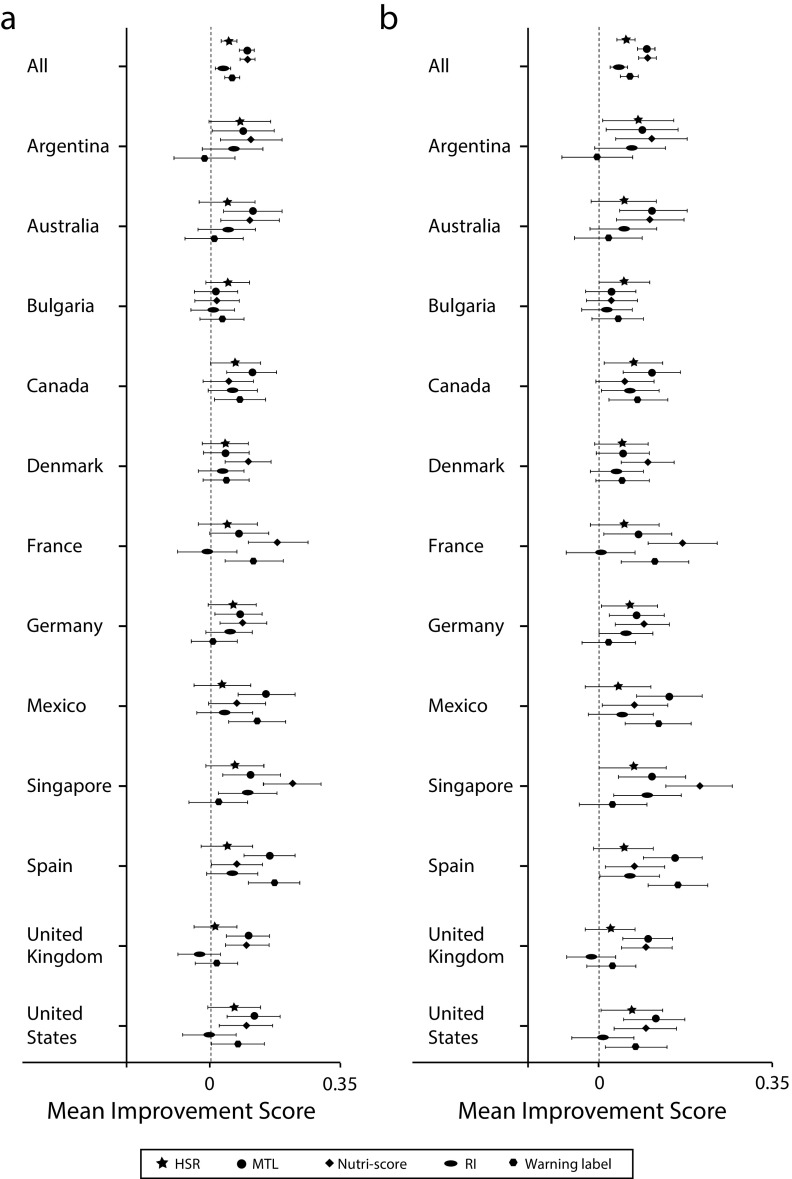

The parameter estimates for the ANCOVAs with data combined and separated across countries (with the Reference Intakes as the reference category) are shown in online Table B. Of interest was the comparison in mean improvement (and associated confidence intervals) for each FoPL. This is shown in the “All Respondents” column in Figure 1. The total sample results show that all 5 FoPLs produced significant improvements in food choices. Across the total sample, the most effective FoPLs appeared to be the Nutri-Score and MTL (both mean improvement scores = 0.09; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.07, 0.11), then the Warning Label (mean improvement score = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.04, 0.08), the HSR (mean improvement score = 0.05; 95% CI = 0.03, 0.07), and lastly the Reference Intakes (mean improvement score = 0.04; 95% CI = 0.02, 0.04). As indicated by the confidence intervals, the MTL and Nutri-Score improved the healthiness of food choices to a significantly greater extent than the Reference Intakes and HSR. We found no other significant differences at the aggregate level. In terms of country-level data, there were very few significant differences between the FoPLs. The Nutri-Score produced greater improvement than the Reference Intakes in France and the Warning Label in Singapore. Both the MTL and Nutri-Score produced greater improvement than the Reference Intakes in the United Kingdom.

FIGURE 1—

Mean Improvement Scores According to Front-of-Package Label (FoPL) Condition for Each Country and Combined Across All Countries for (a) All Respondents and (b) Respondents Selecting Intermediate and Unhealthy Foods at Baseline: April–July 2018

Note. HSR = Health Star Rating; MTL = Multiple Traffic Lights; RI = Reference Intake. The x-axis scale represents change scores ranging from −2 to +2, with 0 representing no change and a positive value representing change toward the healthier option(s) after the addition of an FoPL. “Whiskers” indicate 95% confidence intervals. The 12 study countries were Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to account for the fact that improvement could only occur where respondents selected a product of lower or intermediate nutritional quality in the no-FoPL condition. The parameter estimates can be found in online Table C. The pattern of differences between the FoPLs (shown in the right-hand column of Figure 1) was very similar to that observed in the full data set. At the total sample level, the Nutri-Score and MTL performed significantly better than the other FoPLs. At the country level, the only differences occurred in the case of the United Kingdom, where the MTL performed significantly better than the HSR, and the Reference Intakes improved performance to a level on par with the MTL.

DISCUSSION

Increasingly, nutrition information on the front of prepackaged foods is being used as a public health intervention to educate consumers and encourage them to choose healthier products. This study measured the effectiveness of 5 different FoPLs in terms of how well they influence product choice within and across 12 countries. In the aggregated results for all 12 countries (11 100 respondents), all 5 FoPLs demonstrated the ability to favorably influence product choice, with the Nutri-Score and MTL producing the greatest improvements. The Warning Label and HSR resulted in slightly lower levels of improvement (with only the HSR being significantly different from the Nutri-Score and MTL). The Reference Intakes consistently produced the lowest level of improvement, significantly below that of the Nutri-Score and MTL. Analyzing the data by country resulted in a pattern of effects similar to that of the aggregated data, but with very few of the differences between FoPLs reaching the significance threshold. In a sensitivity analysis including only respondents who were capable of improving on their no-FoPL choices, we observed highly similar patterns. The superior performance of the Nutri-Score and MTL over the Reference Intakes in France and the United Kingdom may be due to the fact that these 2 labels originated in these respective countries and thus participants were likely to be more familiar with them.

The present findings consolidate and extend those of previous studies. Consistent with past research, the results show that the Reference Intakes label (the only fully reductive FoPL included in the present study) was less likely to shift consumers toward healthier choices compared with more interpretive FoPLs.15,20–22,28–30 This outcome provides an important addition to the literature, which has to date primarily focused on Reference Intakes and MTL, with much less work examining the more recently implemented FoPLs of the HSR, Nutri-Score, and Warning Label. The inclusion of a greater number of interpretive FoPLs provides further insight into the specific features of these FoPLs that are likely to enhance their effectiveness. In particular, the superior performance of the 2 colored FoPLs, the Nutri-Score and the MTL, supports the importance of ensuring that on-pack nutrition information is highly visible as well as intuitively understandable.31,32 Warning labels are one of the most recent FoPLs to appear on foods, and a number of different designs have been tested in different countries and studies.33,34 Future research should consider comparing different formats (e.g., different colors, shapes, and anchoring statements) against existing FoPLs.

When considering the impact of FoPLs, it is important to note that choices did not change between the no-FoPL and FoPL conditions for the majority of choice sets. This is consistent with the tendency for past behavior to be the strongest predictor of future behavior. Study participants likely had some familiarity and established preferences for the type of food they would buy within a category (e.g., a general preference for chocolate-flavored cakes such as brownies over dairy cakes such as cheesecake). However, the results of the present study indicate that even this preference can be shifted once salient and intuitive FoPLs are made available. In 12% of choice sets, respondents made an overall healthier choice after FoPLs were included on packs. The finding that 6% of choice sets ended in a less healthy option after the addition of an FoPL is a cause for concern that warrants further investigation.

These conclusions should be considered in terms of the study limitations. In particular, although steps were taken to maximize the ecological validity of the research, the use of products from a fictional brand presented through an online interface presented to Web panel members—some of whom may have elected to participate because of a specific interest in nutrition—may reduce the applicability of results to a real-world setting. The participant samples were not intended to be representative of each country’s population, but rather to consistently reflect a range of sociodemographic profiles across the included countries. As such, and given the recruitment of Web panel members, the demographic characteristics other than those for which quotas were specified may have been distributed in a manner different to what would be found within the respective populations. The experimental design, which involved presenting the food packs with FoPLs soon after those without FoPLs were presented, does not replicate how consumers would encounter FoPLs in the real world and potentially fostered a social desirability bias among participants, limiting the strength of conclusions that can be drawn. Studies analyzing real-world data (e.g., pre–post sales data during FoPL implementation) are needed to permit more definitive conclusions. However, the results could offer insights of particular relevance to online grocery shopping, which is increasing in prevalence.35 Finally, the results of this study are more likely to apply to first-time purchases rather than repeat, habitual purchases because of the use of unfamiliar brands.

A major contribution of the present study is the inclusion of a large number of FoPLs and countries, which provides insights into whether different FoPLs perform differently in various countries and cultural contexts. The relative stability of the findings across countries demonstrates that the ability of an FoPL to influence choice is not necessarily bound to the country in which it is used, and that well-designed FoPLs can be effective internationally. These are important outcomes given the global nature of the food industry and the potential benefits associated with having consistent product-labeling requirements across countries. However, a limitation of the present study is the lack of representation of some geographical areas (e.g., Africa, the Middle East, and most of Asia), and additional work is needed in these locations. Nevertheless, the results have important policy implications and can provide information to governments that are seeking to implement or enhance front-of-pack food labels.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present study received funding from Santé Publique France (French Agency for Public Health) and Curtin University.

We thank all scientists in charge of the translations: Pilar Galan, Karen Assmann, Valentina Andreeva, and Sinne Smed, who contributed to the creation of the different versions of the online survey. We also thank all researchers and doctoral students who tested the online survey.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The protocol of the present study was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval reference: HRE2017-0760) and the institutional review board of the French Institute for Health and Medical Research (IRB Inserm n_17-404).

Footnotes

See also Gustafson, p. 1624.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020. 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- 2.World Health Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health: a framework to monitor and evaluate implementation. 2006. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43524/9789241594547_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed July 23, 2018.

- 3.Hawkes C. Government and voluntary policies on nutrition labelling: a global overview. In: Albert J, editor. Innovations in Food Labelling. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing Ltd; 2010. pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham DJ, Heidrick C, Hodgin K. Nutrition label viewing during a food-selection task: front-of-package labels vs nutrition facts labels [erratum in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(12):2040] J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(10):1636–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunert KG, Wills JM, Fernández-Celemín L. Nutrition knowledge, and use and understanding of nutrition information on food labels among consumers in the UK. Appetite. 2010;55(2):177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temple NJ, Fraser J. Food labels: a critical assessment. Nutrition. 2014;30(3):257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegrist M, Leins-Hess R, Keller C. Which front-of-pack nutrition label is the most efficient one? The results of an eye-tracker study. Food Qual Prefer. 2015;39:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidal L, Antúnez L, Sapolinski A, Giménez A, Maiche A, Ares G. Can eye-tracking techniques overcome a limitation of conjoint analysis? Case study on healthfulness perception of yogurt labels. J Sens Stud. 2013;28(5):370–380. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Der Bend D, Van Dieren J, Marques MDV et al. A simple visual model to compare existing front-of-pack nutrient profiling schemes. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2014;4(4):429–534. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawley KL, Roberto CA, Bragg MA, Liu PJ, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. The science on front-of-package food labels. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(3):430–439. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012000754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pettigrew S, Talati Z, Miller C, Dixon H, Kelly B, Ball K. The types and aspects of front-of-pack food labelling schemes preferred by adults and children. Appetite. 2017;109:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hersey JC, Wohlgenant KC, Arsenault JE, Kosa KM, Muth MK. Effects of front-of-package and shelf nutrition labeling systems on consumers. Nutr Rev. 2013;71(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/nure.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campos S, Doxey J, Hammond D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(8):1496–1506. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cecchini M, Warin L. Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies. Obes Rev. 2016;17(3):201–210. doi: 10.1111/obr.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arrúa A, Machín L, Curutchet MR et al. Warnings as a directive front-of-pack nutrition labelling scheme: comparison with the Guideline Daily Amount and traffic-light systems. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(13):2308–2317. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ducrot P, Julia C, Méjean C et al. Impact of different front-of-pack nutrition labels on consumer purchasing intentions: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(5):627–636. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Julia C, Hercberg S. Nutri-Score: evidence of the effectiveness of the French front-of-pack nutrition label. Ernährungs Umschau. 2017;64(12):181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandpur N, de Morais Sato P, Mais LA et al. Are front-of-package warning labels more effective at communicating nutrition information than traffic-light labels? A randomized controlled experiment in a Brazilian sample. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):E688. doi: 10.3390/nu10060688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machín L, Aschemann-Witzel J, Curutchet MR, Giménez A, Ares G. Does front-of-pack nutrition information improve consumer ability to make healthful choices? Performance of warnings and the traffic light system in a simulated shopping experiment. Appetite. 2018;121:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talati Z, Norman R, Pettigrew S et al. The impact of interpretive and reductive front-of-pack labels on food choice and willingness to pay. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0628-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talati Z, Pettigrew S, Ball K et al. The relative ability of different front-of-pack labels to assist consumers discriminate between healthy, moderately healthy, and unhealthy foods. Food Qual Prefer. 2017;59:109–113. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maubach N, Hoek J, Mather D. Interpretive front-of-pack nutrition labels. Comparing competing recommendations. Appetite. 2014;82:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julia C, Hercberg S. Development of a new front-of-pack nutrition label in France: the five-colour Nutri-Score. Public Health Panorama. 2017:712. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanter R, Vanderlee L, Vandevijvere S. Front-of-package nutrition labelling policy: global progress and future directions. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(8):1399–1408. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson WL, Kelly B, Hector D et al. Can front-of-pack labelling schemes guide healthier food choices? Australian shoppers’ responses to seven labelling formats. Appetite. 2014;72:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drescher LS, Roosen J, Marette S. The effects of traffic light labels and involvement on consumer choices for food and financial products. Int J Consum Stud. 2014;38(3):217–227. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charness G, Gneezy U, Kuhn MA. Experimental methods: between-subject and within-subject design. J Econ Behav Organ. 2012;81(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Herpen E, Hieke S, van Trijp HCM. Inferring product healthfulness from nutrition labelling. The influence of reference points. Appetite. 2014;72:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feunekes GIJ, Gortemaker IA, Willems AA, Lion R, van den Kommer M. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling: testing effectiveness of different nutrition labelling formats front-of-pack in four European countries. Appetite. 2008;50(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly B, Hughes C, Chapman K et al. Consumer testing of the acceptability and effectiveness of front-of-pack food labelling systems for the Australian grocery market. Health Promot Int. 2009;24(2):120–129. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham DJ, Orquin JL, Visschers VHM. Eye tracking and nutrition label use: a review of the literature and recommendations for label enhancement. Food Policy. 2012;37(4):378–382. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Kleef E, Dagevos H. The growing role of front-of-pack nutrition profile labeling: a consumer perspective on key issues and controversies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55(3):291–303. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.653018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabrera M, Machín L, Arrúa A et al. Nutrition warnings as front-of-pack labels: influence of design features on healthfulness perception and attentional capture. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(18):3360–3371. doi: 10.1017/S136898001700249X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acton RB, Hammond D. Do consumers think front-of-package “high in” warnings are harsh or reduce their control? A test of food industry concerns. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(11):1687–1691. doi: 10.1002/oby.22311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anesbury Z, Nenycz-Thiel M, Dawes J, Kennedy R. How do shoppers behave online? An observational study of online grocery shopping. J Consum Behav. 2016;15(3):261–270. [Google Scholar]