Abstract

The aim of this prospective investigation was to assess the association of 18F-FDG PET/CT with time to hormonal treatment failure (THTF) in men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Methods: 76 men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer recruited from 2005 to 2011 underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT and were followed prospectively for THTF, defined as treatment change to chemotherapy or death. Patients who had not switched to chemotherapy were censored at the last follow-up date (median of 36 mo; range, 12–108 mo). Cox regression analyses were performed to examine the association between PET/CT measurements: sum of SUVmax, maximum SUVmax, and average SUVmax for up to 10 of the most active lesions and THTF. Survival probabilities were based on the Kaplan–Meier method. Results: 43 patients had hormonal treatment failure, and 8 died without documented treatment failure. Median THTF was 26.5 mo (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–46.6 mo). The THTF-free probability at 5 y was 35% ± 6%. On univariate analysis, all PET parameters, including number of lesions, were statistically significant for THTF. In a reduced multivariate model accounting for clinical variables, only sum of SUVmax (hazard ratio, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.002–1.03; P = 0.024) and number of lesions (hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08–1.29; P < 0.001) were independently associated with THTF. When sum of SUVmax was grouped into quartile ranges, there was a significantly worse survival probability for patients in the fourth-quartile range than in the first, with a univariate hazard ratio of 6.2 (95% CI, 2.8–13.6; P < 0.001). Conclusion: Sum of SUVmax and number of lesions derived from 18F-FDG PET/CT provide independent prognostic information on THTF in men with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer.

Keywords: 18F-FDG, PET/CT, prostate, cancer, castrate-sensitive

Prostate cancer affects approximately 1 in 6 men and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in men (1). Although most patients present with locoregional disease, approximately 6% of patients have metastatic disease on initial presentation (1). Furthermore, many patients undergoing treatment will eventually develop metastatic disease, with a growing incidence of metastatic prostate cancer over the past decade (2). Androgen deprivation therapy remains the first-line treatment for metastatic prostate cancer. However, in many cases patients will develop castration resistance, with tumor growth despite suppressed serum androgens, thus requiring further treatment with various other drug combinations (3). Development of a castration-resistant state is associated with poor outcome in terms of both quality of life and survival despite several novel investigational and recently approved therapeutic regimens (4).

The ability to predict time to hormonal treatment failure (THTF) in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer can be of value for clinical management decisions, as the early development of castration resistance has been associated with decreased overall survival (5,6). However, ongoing attempts to accurately predict THTF have been met with mixed results. Assays evaluating the utility of prostate cancer antigen-3 messenger RNA and type 2 transmembrane serine protease with v-erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog have not been reliable in predicting time to castration resistance (7,8). Serum follicle-stimulating hormone has been shown to be inversely related to THTF; however, data are limited (9).

PET is a noninvasive imaging tool to interrogate underlying tumor biology. Several PET-based radiotracers, including 18F- or 11C-acetate, 18F- or 11C-choline, 16β-18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone targeted to the androgen receptor, the synthetic l-leucine analog 18F-fluciclovine, and radiotracers based on prostate-specific membrane antigen, have been investigated for the imaging evaluation of prostate cancer (10). 18F-FDG is the most commonly used PET radiotracer for oncologic imaging and is based on the increased glucose metabolism in malignant tissue (11). 18F-FDG PET has been used in the diagnosis, staging, prediction, and monitoring of treatment response and in surveillance for a variety of cancers (12). Although initially thought to be of limited value, 18F-FDG PET/CT has demonstrated utility in assessing treatment response and predicting overall survival in castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer (13–15).

The purpose of this prospective single-center study was to determine whether parameters derived from 18F-FDG PET/CT can independently predict THTF in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

Institutional Review Board and Radiation Safety Committee approval was obtained for this prospective cohort study. All patients gave written informed consent in adherence with the regulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The investigation was performed under clinical trial registration number NCT00282906, “FDG Positron Emission Tomography and Computed Tomography (PET-CT) in Metastatic Prostate Cancer.”

Patients were prospectively recruited from 2005 to 2011. Patients were eligible if they were beginning their first antiandrogen therapy or a new antiandrogen therapy after not responding to a prior one. Medical therapy was determined at the discretion of the treating physicians, and patients were chosen for the study after the decision for antiandrogen therapy had been made. The androgen deprivation medications included bicalutamide, leuprolide acetate, and ketoconazole, singly or in combination and with or without bisphosphonates (supplemental materials, available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org). None of the patients received enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate, as these medications were not approved during the study period. Metastatic disease was confirmed by CT and bone scintigraphy. The mean, median, and range of time from initial diagnosis to PET/CT were 1,594 d, 458 d, and 2–7,217 d, respectively. Exclusion criteria included a history of cancer other than prostate cancer, active infection, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, or active inflammatory conditions. In addition, patients with recent or complicated nonhealing fractures or recent arthroplasty were excluded to avoid the challenge of interpreting increased osseous metabolic activity in areas that may also be sclerotic on CT but are secondary to reactive or inflammatory changes.

PET/CT Imaging and Interpretation

All patients underwent PET/CT imaging (Biograph Duo LSO; Siemens) 1 h after intravenous administration of 370–550 MBq (10–15 mCi) of 18F-FDG, as previously described (15). Customary quality control procedures were performed before all PET/CT scans (68Ge normalization daily and Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging PET/CT chest phantom every 3 mo). All patients fasted for 4–6 h before 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, and water intake was encouraged before and after each scan. Blood glucose levels were obtained for all patients before intravenous administration of 18F-FDG and in all cases was less than 200 mg/dL.

Helical CT (pitch, 1.0; 90–130 mAs; 130 kVp) was performed first for each scan. Only oral contrast material was used. PET was then performed for 4 min per bed position at a sufficient number of bed positions to cover the top of the head to the feet. Raw CT data were reconstructed into 5-mm-thick transverse images, and coronal and sagittal reformats were generated. CT-based attenuation-corrected PET images were reconstructed and viewed on a color high-resolution monitor. PET and CT images could be viewed on a continuous fusion scale from PET-only to CT-only images using E-soft image fusion software (Siemens).

PET/CT images were interpreted in consensus by 2 fellowship-trained board-certified nuclear radiologists with more than 20 y of experience in interpreting PET/CT studies. Lesions with visually discernible uptake and a distinct correlation on CT that did not represent a physiologic or benign entity were selected for further evaluation, with up to an arbitrary maximum of 30 lesions per scan for the various metastatic sites (e.g., bone, lymph node, and soft tissue). The mean hepatic background SUV was obtained for each patient by placing a 3-cm-diameter region of interest over an area of normal liver (16). The SUVmax of each lesion was than determined using 3-dimensional regions of interest with vendor-provided software (Siemens), subtracting the mean hepatic background activity for analysis.

The PET variables included the average and sum of the SUVmax of all lesions as well as the maximum SUVmax of the most active lesion. The SUVmax was assigned to be 0 if it was lower than the mean hepatic background SUV.

Statistical Methods

The primary endpoint of the analyses was THTF, defined as the time between the date of baseline PET/CT imaging and the date of a change to cytotoxic chemotherapy or the date of death, whichever came first. Patients who were alive and had not switched to chemotherapy were censored at the last follow-up date (median of 36 mo; range, 12–108 mo). The analyses included only the 10 most metabolically active lesions for patients who had more than 10 lesions seen on PET/CT. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to examine the association between PET measurements and THTF (17). A reduced multivariate Cox model was constructed by including only PET variables that were significantly associated with THTF at a P value of no more than 0.05. Given that there was generally a linear trend for all the PET variables versus patients’ THTF, in that higher measurements seemed to be associated with worse outcomes, the PET variables were treated as continuous variables in these analyses. Analyses were also performed by adjusting for clinical parameters, including age, serum prostate-specific antigen level, alkaline phosphatase level, and Gleason score, to further assess the independent association between the PET parameters and THTF. P values were based on the likelihood ratio tests associated with Cox model regression analysis.

To further illustrate patterns, for each PET variable, patients were grouped into quartiles to display a dose–response effect in the plots, should it exist. The survival figures presented the probability that hormonal treatment would not fail, calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The effects of the PET parameters on THTF were then examined separately for patients in each quartile. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (version 11.0; StataCorp LP). All reported P values were 2-sided, and a P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In total, 76 patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer met the eligibility criteria during the accrual period and underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT. The median age at baseline PET/CT was 66 y (range, 48–88 y), and the median Gleason score was 9 (range, 6–10). The mean hepatic (background) SUV of patients was 2.3 (range, 1.2–3.2). The median number of metabolically active metastatic lesions (above mean hepatic activity) for each patient was 2 (range, 0–10). Six patients had lesions that were mildly active but had SUVmax levels below the patient-specific average mean hepatic SUV. The median serum alkaline phosphatase level at enrollment was 87 IU/L (range, 40–2,208 IU/L), and the median serum prostate-specific antigen level was 32.3 ng/mL (range, 0.04–3,799 ng/mL). The median and ranges for the PET parameters were, respectively, 4.2 and 0–181 for sum of SUVmax, 2.4 and 0–21.9 for maximum SUVmax, and 1.4 and 0–18.1 for average SUVmax (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient and Disease Characteristics

| Variable | Total (n = 76) | % |

| Age at baseline PET/CT scan (y) | ||

| Median | 66 (48, 59, 73, 88) | |

| <70 | 49 | 65 |

| ≥70 | 27 | 35 |

| Median PSA level at baseline (ng/mL) | 32.3 (0.04, 6.2, 161.1, 3,799) | |

| Median alkaline phosphatase at baseline (IU/L) | 87 (40, 61, 149.5, 2,208) | |

| Gleason score at diagnosis | ||

| Median | 9 (6, 7, 9, 10) | |

| Missing | 3 | |

| Baseline disease evaluation: PET/CT results*† | ||

| Total no. of lesions | 2 (0, 1, 8, 10) | |

| Sum of SUVmax | 4.2 (0, 0.6, 14.4, 181) | |

| Maximum SUVmax | 2.4 (0, 0.5, 5.0, 21.9) | |

| Average SUVmax | 1.4 (0, 0.3, 2.8, 18.1) |

For some patients who had extensive numbers of bone lesions, not all bone lesions were counted or measured for disease evaluation. The 10 hottest lesions were used in analyses.

6 patients did not have lesions with SUVmax above liver background at baseline.

PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Data in parentheses are minimum, 25%, 75%, and maximum.

Relationship of PET Parameters to THTF

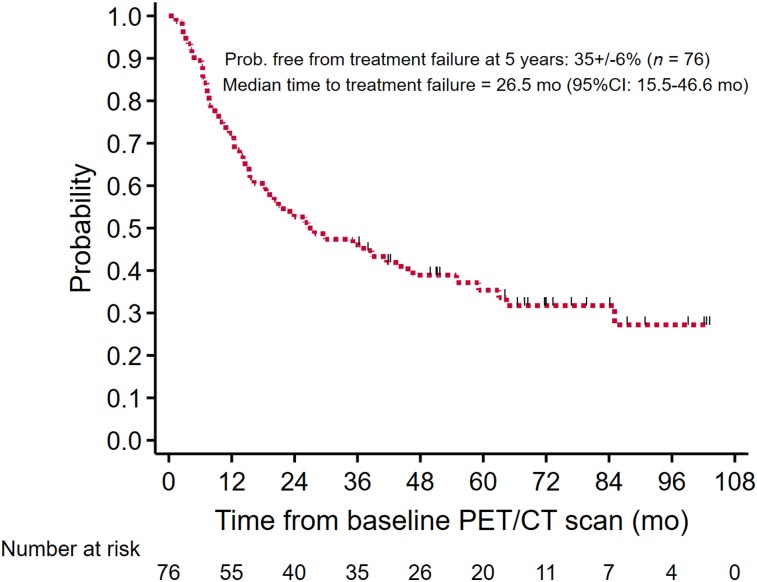

Of the 76 patients, 43 had treatment failure and 8 died without a documented date of treatment failure. For the THTF analysis, these 51 patients were considered to have had events. Of the 8 patients who died without a documented treatment failure, the median time to death was 27.2 mo (range, 7.3–64.4 mo). The overall probability of treatment failure for the cohort at 5 y was 35% ± 6%, with a median THTF of 26.5 mo (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–46.6 mo) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Overall probability of THTF.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the Cox regression model of THTF, with and without adjusting for the standard clinical parameters. As shown in the table, univariate Cox regression analyses demonstrated an increased hazard ratio for the associated PET parameter with each unit increase. The corresponding PET parameters demonstrated a hazard ratio of 1.03 (95% CI, 1.01–1.04; P < 0.001) for sum of SUVmax, 1.11 (95% CI, 1.04–1.17; P = 0.002) for maximum SUVmax, and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04–1.26; P = 0.012) for average SUVmax. In addition, the number of baseline disease sites was evaluated, with a hazard ratio of 1.23 (95% CI, 1.13–1.33; P < 0.001) for each increase in number of disease sites. In the reduced multivariate Cox regression analysis, incorporating the 2 most statistically significant (P < 0.001) parameters from the univariate analysis, the continuous parameters sum of SUVmax and number of baseline disease sites remained significant, with hazard ratios of 1.01 (95% CI, 1.002–1.03; P = 0.024) and 1.18 (95% CI, 1.08–1.29; P < 0.001), respectively. To highlight the prognostic value of the PET parameters, we present 2 illustrative cases (Figs. 2 and 3) of castration-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer and a summary of the corresponding clinical and imaging parameters.

TABLE 2.

Hazard Ratios, 95% CIs, and P Values from Cox Regression Models on THTF

| Univariate* |

Multivariate† |

Reduced multivariate‡ |

Multivariate adjusting for clinical variables¶ |

||||||

| Variable | Range | HR | P | HR | P | HR | P | HR | P |

| Baseline sum of SUVmax | 0–181 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.084 | 1.01 (1.002, 1.03) | 0.024 | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 0.004 |

| Baseline maximum SUVmax | 0–21.9 | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | 0.002 | 1.12 (0.93, 1.33) | 0.26 | ||||

| Baseline average SUVmax | 0–18.1 | 1.15 (1.04, 1.26) | 0.012 | 0.77 (0.51, 1.16) | 0.21 | ||||

| Baseline disease sites (n) | 0–101 | 1.23 (1.13, 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.02, 1.27) | 0.017 | 1.18 (1.08, 1.29) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.03, 1.29) | 0.011 |

Analysis of association between PET variables and THTF.

Includes all 4 PET variables as independent variables.

Includes only PET variables that are associated with THTF at P ≤ 0.05 after controlling for each other.

Reports association between SUVmax or number of baseline disease sites with THTF after adjusting for clinical variables including age, baseline Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen level, and alkaline phosphatase level.

HR = hazard ratio.

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs.

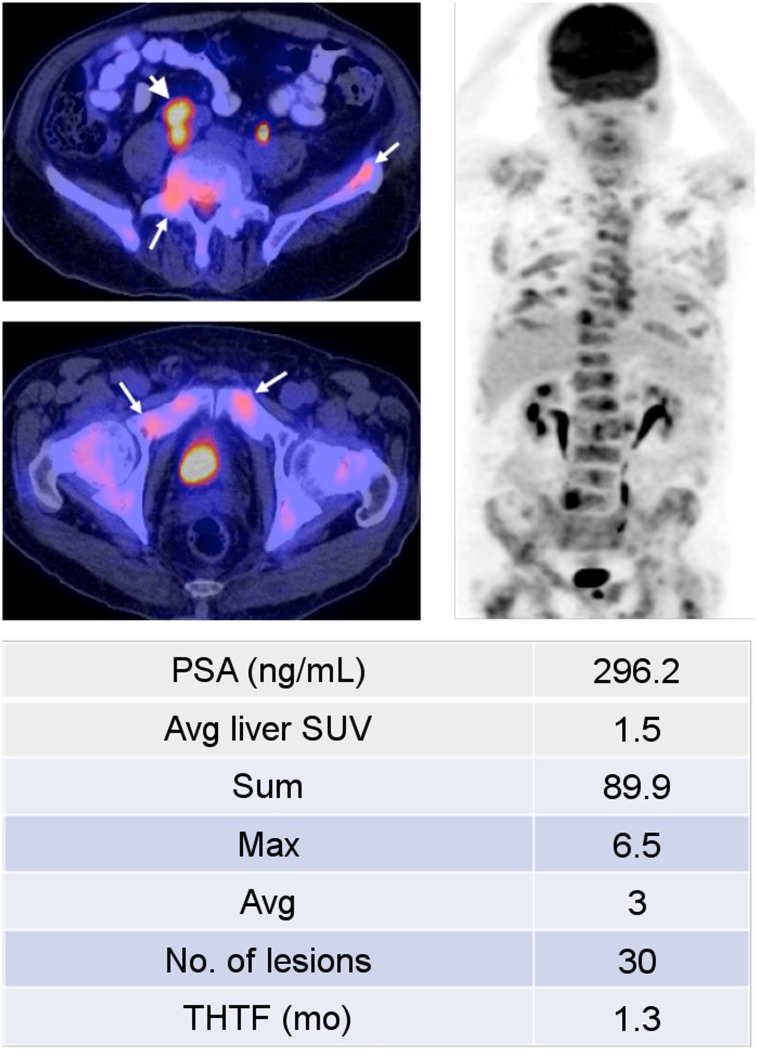

FIGURE 2.

A 72-y-old man who presented with treatment-naïve castration-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer, with Gleason score of 7 (4 + 3). 18F-FDG PET/CT (left: axial PET/CT, right: coronal PET) demonstrated widespread metastatic disease, involving bones (long arrows) and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (short arrow). Shortly after start of androgen-deprivation therapy, patient’s disease progressed and chemotherapy was initiated. PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

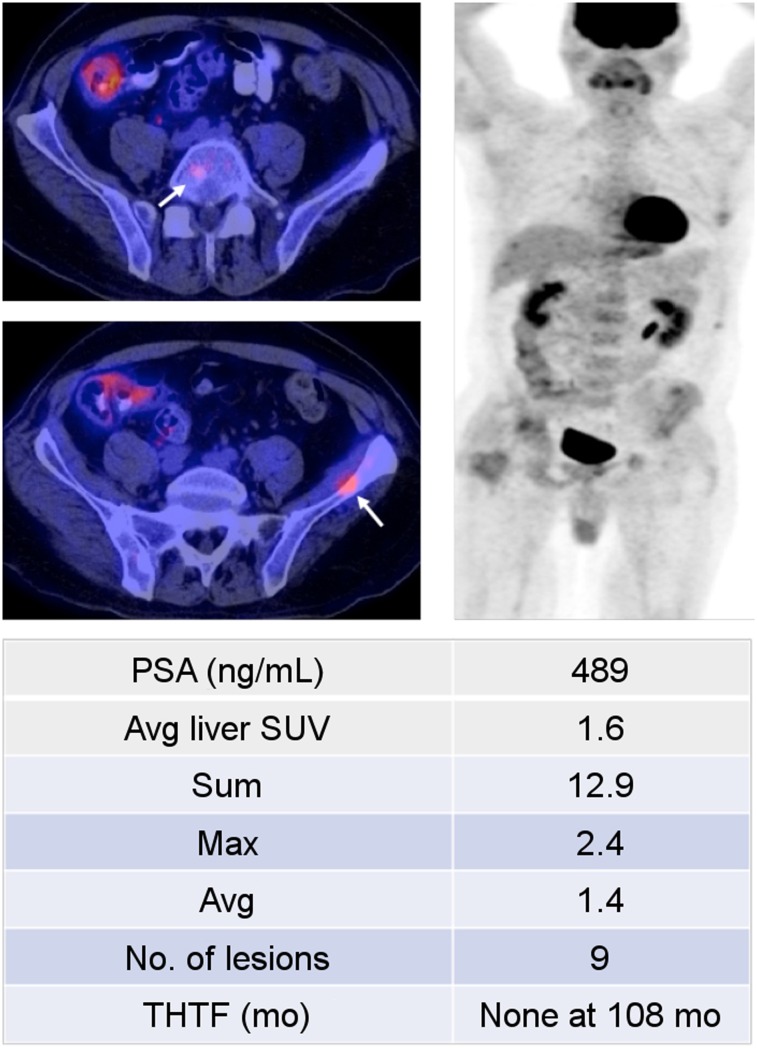

FIGURE 3.

A 53-y-old man who presented with treatment-naïve castration-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer, with Gleason score of 8 (4 + 4). 18F-FDG PET/CT (left: axial PET/CT, right: coronal PET) demonstrated scattered osseous metastases (arrows). Despite significantly elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSF) level, PET/CT revealed relatively low metabolic activity, with SUVmax sum of 12.9. Patient responded well to androgen deprivation therapy, and his disease remained well controlled at termination of study.

Relationship of PET Parameters to THTF—Grouping Patients by Quartile

To further illustrate the impact of the PET parameters and number of baseline disease sites on patients’ THTF, patients were separated into 4 quartiles. Table 3 summarizes the results of the Cox regression model of THTF for the grouping of patients by quartiles.

TABLE 3.

Hazard Ratios, 95% CIs, and P Values from Cox Regression Models on THTF, Grouping Patients According to Quartiles

| Univariate* |

Adjusting for clinical variables† |

||||||||

| Variable | n | Quartile range | Events (n) | Median THTF (mo) | % patients with no events at 3 y (±SE) | HR | P‡ | HR | P‡ |

| Baseline sum of SUVmax | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| First quartile | 20 | 0, 0.6 | 11 | 64 | 75 ± 10 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second quartile | 18 | 0.6, 4.2 | 10 | 38 | 56 ± 12 | 1.4 (0.57, 3.2) | 1.4 (0.57, 3.3) | ||

| Third quartile | 19 | 4.2, 14.4 | 12 | 29 | 42 ± 11 | 1.8 (0.79, 4.1) | 2.1 (0.85, 5.2) | ||

| Fourth quartile | 19 | 14.4, 181 | 18 | 7 | 11 ± 7 | 6.2 (2.8, 13.6) | 7.4 (3.0, 18.2) | ||

| Baseline maximum SUVmax | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| First quartile | 19 | 0, 0.5 | 10 | 85 | 79 ± 9 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second quartile | 20 | 0.5, 2.4 | 12 | 29 | 50 ± 11 | 1.6 (0.70, 3.8) | 1.5 (0.64, 3.6) | ||

| Third quartile | 18 | 2.4, 5.0 | 14 | 12 | 33 ± 11 | 2.9 (1.3, 6.6) | 4.0 (1.6, 9.8) | ||

| Fourth quartile | 19 | 5.0, 21.9 | 15 | 13 | 21 ± 9 | 3.8 (1.7, 8.5) | 5.3 (2.1, 13.2) | ||

| Baseline average SUVmax | 0.007 | <0.001 | |||||||

| First quartile | 19 | 0, 0.3 | 10 | 85 | 74 ± 10 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second quartile | 19 | 0.3, 1.4 | 13 | 29 | 47 ± 11 | 1.9 (0.84, 4.4) | 1.6 (0.69, 3.9) | ||

| Third quartile | 19 | 1.4, 2.8 | 14 | 12 | 37 ± 11 | 2.5 (1.1, 5.8) | 3.2 (1.2, 8.0) | ||

| Fourth quartile | 19 | 2.8, 18.1 | 14 | 14 | 26 ± 10 | 2.9 (1.3, 6.7) | 3.8 (1.5, 9.7) | ||

| Baseline disease sites (n) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| First quartile | 28 | 0, 1 | 15 | 59 | 64 ± 9 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second quartile | 12 | 1, 2 | 6 | 64 | 67 ± 14 | 1.2 (0.46, 3.1) | 1.8 (0.59, 5.3) | ||

| Third quartile | 19 | 2, 8 | 14 | 20 | 42 ± 11 | 2.2 (1.03, 4.5) | 2.6 (1.1, 6.0) | ||

| Fourth quartile | 17 | 8, 10 | 16 | 7 | 6 ± 6 | 6.4 (3.0, 13.5) | 6.7 (2.5, 17.8) | ||

| Overall | 76 | 51 | 26.5 (15.5, 46.6) | 46 ± 6 | |||||

Univariate analysis of association between each PET variable (grouped into quartiles) and THTF.

Assessment of association between each PET variable and THTF, adjusting for clinical variables including age, baseline Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen level, and alkaline phosphatase level.

P values were from test for trend of 4 quartiles.

HR = hazard ratio.

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs.

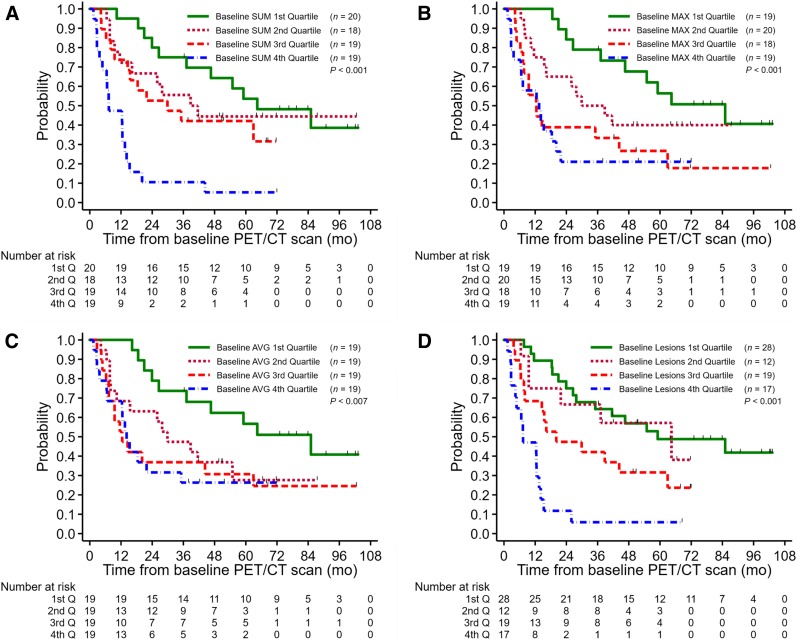

For sum of SUVmax, the median THTF for the first, second, third, and fourth quartiles was 64 mo, 38 mo, 29 mo, and 7 mo, respectively. There was a significant difference (P < 0.001) in THTF, especially in that patients in the fourth quartile had a dramatically shorter THTF, as demonstrated by the hazard ratio of 6.2 (95% CI, 2.8–13.6) between the fourth and first quartiles (Fig. 4A). In the first quartile, 75% ± 10% of patients had no events within 3 y from baseline, as compared with 11% ± 7% in the fourth quartile. Similar significant differences were demonstrated when comparing the quartiles for maximum SUVmax (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B), average SUVmax (P = 0.007) (Fig. 4C), and number of baseline disease sites (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

1.THTF by baseline sum of SUVmax (A), baseline maximum SUVmax (B), baseline average SUVmax (C), and number of baseline disease sites (D).

DISCUSSION

Although androgen deprivation therapy remains the mainstay for castration-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer, there have been considerable advancements in therapeutic options (18). In addition to classic medical castration, current options include combined androgen blockade, peripheral androgen blockade, and potentially even up-front use of cytotoxic chemotherapy (19). Recent literature has also described the use of therapy locally directed to prostate cancer oligometastases as a potential option (20). Furthermore, the role of continuous versus intermittent androgen deprivation therapy remains controversial (21). However, despite these advances, the ability to accurately risk-stratify patients, potentially guiding therapeutic options, remains relatively rudimentary (22).

In 2003, Glass et al. developed a prognostic model based on prostate-specific antigen, appendicular versus axial skeletal bone metastases, performance status, and Gleason score (23). Patients were stratified into good-, intermediate-, and poor-risk groups, and the model was validated on the basis of data from the SWOG 8894 trial (24). However, because of a combination of factors, including advances in treatment management and the implementation of widespread prostate-specific antigen screening, the model has performed poorly in subsequent studies (25). Gravis et al. evaluated the utility of additional prognostic factors, including alkaline phosphatase level, lactate dehydrogenase level, and pain scores, demonstrating that alkaline phosphatase may help predict overall survival. Although alkaline phosphatase slightly outperformed the Glass model (concordance index, 0.64 vs. 0.58), the confidence of the 2 indices overlapped (25). Furthermore, in the GETUG-AFU 15 study, abnormal alkaline phosphatase values were not independently associated with treatment response to up-front docetaxel with androgen deprivation therapy, questioning its ability to predict treatment response (26).

Location and volume of disease have both emerged as potential candidates in risk stratification. In the ECOG 3805 trial, patients with high-volume disease, defined as 4 or more osseous metastases or visceral metastases, demonstrated the largest benefit from adding up-front docetaxel to androgen deprivation therapy (19). Conversely, in a systematic literature review of patients with recurrent disease isolated to regional or retroperitoneal lymph nodes, Abdollah et al. showed that salvage lymph node dissection can delay clinical progression and postpone the need for hormonal therapy in up to one third of patients (27), thus demonstrating potentially differing treatment options for patients with low-volume or localized disease. However, there is a lack of consensus on how location and volume should be defined. Furthermore, the location and number of metastatic foci do not give the complete picture of absolute disease burden and may not characterize disease aggressiveness (22).

Imaging has the potential to provide an objective assessment of disease extent and prognosis in prostate cancer. However, current standard diagnostic imaging techniques, such as CT and 99mTc-based bone scintigraphy, insufficiently capture the true tumor burden (28). 99mTc-based bone scintigraphy is fundamentally limited by its indirect nonspecific assessment of osteoblastic activity and bone turnover (29). Although CT is useful in the assessment of soft-tissue metastases, it cannot distinguish between active sclerotic bone metastases and treated disease. Additionally, findings on CT are not necessarily reflective of disease aggressiveness (30).

Several advantages of imaging metastatic prostate cancer with 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging have been shown (10). 18F-FDG PET/CT can help distinguish between metabolically active versus dormant bone lesions. Furthermore, 18F-FDG PET/CT can provide insight into treatment response assessment by comparing the 18F-FDG uptake of lesions between serial scans (31,32). However, studies evaluating the prognostic utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT for metastatic prostate cancer are limited. Meirelles et al. demonstrated an inverse correlation between overall survival and the SUVmax of the most active lesion on baseline 18F-FDG PET. However, the study was limited to 51 patients, only 12 of whom had castration-sensitive disease (33). In a cohort of 87 men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer, Jadvar et al. evaluated baseline 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters as imaging biomarkers for overall survival. The study determined that sum of SUVmax contributes independent prognostic information on overall survival, particularly when patients in the fourth quartile are compared with those in the first quartile, with a hazard ratio of 3.8 (95% CI, 1.8–7.9; P < 0.001) (15).

In our study, we found that on univariate analysis all PET parameters were associated with THTF. However, on multivariate analysis only sum of SUVmax and number of metabolically active baseline disease sites were of significant independent prognostic value. The utility of sum of SUVmax over the other PET parameters was somewhat expected, as it is more representative of overall disease burden. The prognostic value of the PET parameters was further highlighted after patients were divided into quartiles, with significant differences in all parameters between the first and fourth quartiles. Additionally, the percentage of patients who experienced hormonal treatment failure differed substantially between the fourth and first quartiles, most pronounced for sum of SUVmax and number of baseline disease sites. This finding further highlights the data that sum of SUVmax contains with regard to disease burden and aggressiveness. Although beyond the scope of this study, assessing the utility of sum of SUVmax and number of metabolically active disease sites to guide more aggressive first-line therapy, such as chemohormonal therapy, would be interesting.

Potential limitations of our study include the lack of histologic confirmation for the metastatic lesions, in view of practical and ethical constraints. However, all selected lesions were required to have correlations on standard imaging consistent with sites of metastatic disease. Additionally, all patients underwent multiple additional follow-up 18F-FDG PET/CT and standard imaging examinations over the course of the study for separate research inquiries. Although follow-up imaging data were outside the scope of this analysis, the subsequent studies were used for additional confirmation of proper initial selection of metastatic lesions. We elected to apply the widely used and simple SUVmax as the primary analysis parameter. Other emerging parameters such as metabolic tumor volume and total-lesion glycolysis are less often used in the clinic but would be of interest in future investigations in this clinical setting. Our study did not control for type of androgen deprivation therapy given during the study, which was at the discretion of the clinician. None of the patients in this study received enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate, which were approved subsequent to the accrual termination. However, these results are still applicable to patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy or in areas in which enzalutamide or abiraterone are unavailable or inaccessible (34). In addition, some patients may benefit from the use of up-front docetaxel in view of more rapid clearance of docetaxel in castrated men than in noncastrated patients (35). We did not monitor the serum testosterone level to define emergence of the castration-resistant state (prostate-specific antigen rise despite serum testosterone level below 50 ng/dL). Instead, we used THTF as a practical endpoint and an operational proxy for emergence of the castration-resistant state, prompting the clinician to consider chemotherapy. Furthermore, there may be differences in tumor biology and outcome between patients receiving first- or second-line androgen deprivation therapy, which may influence THTF. However, most of the patients in this study received first-line therapy, and this distinction was not assessed in our study. Lastly, as per our Intuitional Review Board requirements, the treating oncologists were informed about the findings of all 18F-FDG PET/CT scans, and any changes in management based on these findings were left to the discretion of the oncologists.

CONCLUSION

Sum of SUVmax and number of metabolically active lesions derived from 18F-FDG PET/CT are useful imaging biomarkers for predicting THTF in men with castration-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer. The prognostic value of these parameters to stratify patients between various conventional and emerging treatment strategies requires further validation in prospective clinical trials.

DISCLOSURE

Support grants were received from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA111613, Hossein Jadvar) and from the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30‐CA014089). No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Is 18F-FDG PET/CT useful in predicting the emergence of hormonal treatment failure in men with metastatic castrate-sensitive prostate cancer?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: This prospective single-center clinical trial showed that 18F-FDG PET/CT provides statistically significant independent prognostic information on time to hormonal treatment failure in men with castrate-sensitive prostate cancer.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: 18F-FDG PET/CT has potential utility in clinical management decisions in the care of men with castrate-sensitive prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly SP, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Cook MB. Past, current, and future incidence rates and burden of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4:121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litwin MS, Tan H. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer: a review. JAMA. 2017;317:2532–2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirby M, Hirst C, Crawford ED. Characterising the castration-resistant prostate cancer population: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:1180–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anampa-Guzman AC, Sulca-Huamani O, Perez-Mendez R, Mendoza-Soto G, Chavez PC, Aliaga R. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: secondary analysis [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl):e597. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bournakis E, Efstathiou E, Varkaris A, et al. Time to castration resistance is an independent predictor of castration-resistant prostate cancer survival. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:1475–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Piñeiro L, Schalken JA, Cabri P, Maisonobe P, de la Taille A. Evaluation of urinary prostate cancer antigen-3 (PCA3) and TMPRSS2-ERG score changes when starting androgen-deprivation therapy with triptorelin 6-month formulation in patients with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2014;114:608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Taille A, Martinez-Pineiro L, Cabri P, Houchard A, Schalken J. Factors predicting progression to castrate-resistant prostate cancer in patients with advanced prostate cancer receiving long-term androgen-deprivation therapy. BJU Int. 2017;119:74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoare D, Skinner TA, Black A, Robert Siemens D. Serum follicle-stimulating hormone levels predict time to development of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9:122–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadvar H. Molecular imaging of prostate cancer: PET radiotracers. AJR. 2012;199:278–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadvar H. Positron emission tomography in prostate cancer: summary of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Tomography. 2015;1:18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu S, Alavi A. Unparalleled contribution of 18F-FDG PET to medicine over 3 decades. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(10):17N–21N, 37N. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadvar H. FDG PET in prostate cancer. PET Clin. 2009;4:155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadvar H. Is there use for FDG-PET in prostate cancer? Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46:502–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadvar H, Desai B, Ji L, et al. Baseline 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters as imaging biomarkers of overall survival in castrate-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1195–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paquet N, Albert A, Foidart J, Hustinx R. Within-patient variability of 18F-FDG: standardized uptake values in normal tissues. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:784–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox GE, Oakes DR. Analysis of Survival Data. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ost P, Bossi A, Decaestecker K, et al. Metastasis-directed therapy of regional and distant recurrences after curative treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2015;67:852–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain M, Tangen CM, Berry DL, et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1314–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Psutka SP, Frank I, Karnes RJ. Risk stratification in hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer: more questions than answers. Eur Urol. 2015;68:205–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glass TR, Tangen CM, Crawford ED, Thompson IAN. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate: identifying prognostic groups using recursive partitioning. J Urol. 2003;169:164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisenberger MA, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gravis G, Boher J-M, Fizazi K, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in noncastrate metastatic prostate cancer: validation of the Glass model and development of a novel simplified prognostic model. Eur Urol. 2015;68:196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdollah F, Briganti A, Montorsi F, et al. Contemporary role of salvage lymphadenectomy in patients with recurrence following radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2015;67:839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tombal B, Lecouvet F. Modern detection of prostate cancer’s bone metastasis: is the bone scan era over? Adv Urol. 2012;2012:893193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langsteger W, Rezaee A, Pirich C, Beheshti M. 18F-NaF-PET/CT and 99mTc-MDP bone scintigraphy in the detection of bone metastases in prostate cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46:491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jadvar H. Molecular imaging of prostate cancer with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6:317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris MJ, Akhurst T, Osman I, et al. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;59:913–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jadvar H, Pinski JK, Conti PS. FDG PET in suspected recurrent and metastatic prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:1485–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meirelles GSP, Schöder H, Ravizzini GC, et al. Prognostic value of baseline [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and 99mTc-MDP bone scan in progressing metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6093–6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sathekge M, Bruchertseifer F, Knoesen O, et al. 225Ac-PSMA-617 in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced prostate cancer: a pilot study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franke RM, Carducci MA, Rudek MA, Baker SD, Sparreboom A. Castration-dependent pharmacokinetics of docetaxel in patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4562–4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.