Abstract

Objectives

Murine models of interleukin (IL)-23-driven spondyloarthritis (SpA) have demonstrated entheseal accumulation of γδT-cells which were responsible for the majority of local IL-17A production. However, IL-23 blockers are ineffective in axial inflammation in man. This study investigated γδT-cell subsets in the normal human enthesis to explore the biology of the IL-23/17 axis.

Methods

Human spinous processes entheseal soft tissue (EST) and peri-entheseal bone (PEB) were harvested during elective orthopaedic procedures. Entheseal γδT-cells were evaluated using immunohistochemistry and isolated and characterised using flow cytometry. RNA was isolated from γδT-cell subsets and analysed by qPCR. Entheseal γδT-cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin, anti-CD3/28 or IL-23 and IL-17A production was measured by high-sensitivity ELISA and qPCR.

Results

Entheseal γδT-cells were confirmed immunohistochemically with Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets that are cytometrically defined. Transcript profiles of both cell populations suggested tissue residency and immunomodulatory status. Entheseal Vδ2 cells expressed high relative abundance of IL-23/17-associated transcripts including IL-23R, RORC and CCR6, whereas the Vδ1 subset almost completely lacked detectable IL-23R transcript. Following PMA stimulation IL-17A was detectable in both Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets, and following CD3/CD28 stimulation both subsets showed IL-17A and IL-17F transcripts with neither transcript being detectable in the Vδ1 subset following IL-23 stimulation.

Conclusion

Spinal entheseal Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets are tissue resident cells with inducible IL-17A production with evidence that the Vδ1 subset does so independently of IL-23R expression.

Keywords: spondyloarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, T cells, psoriatic arthritis

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Entheseal resident γδT-cells drive enthesitis in an interleukin (IL)-23 overexpression animal model of spondyloarthritis (SpA) but very little is known about γδT-cells at the human enthesis.

IL-17 but not IL-23 inhibition is effective in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis.

What does this study add?

This study identifies tissue resident populations of γδT-cells in the healthy enthesis that have transcript expression related to tissue repair and immunomodulation and identifies a subset of which is able to produce IL-17 independently of IL-23R expression.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

First comprehensive evaluation of human entheseal γδT-cells, delivering insights into the mechanism underlying effective treatment of SpA.

Highlights γδT-cells and IL-23 independent IL-17 production mechanisms as potential targets of future therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

The spondyloarthropathies (SpA) are a group of inflammatory diseases of which ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is often referred to as the prototypic member.1 Mechanical strain is likely to be an important environmental risk factor2 which may interact with various genetic elements to initiate disease. Although dysregulation of the interleukin (IL)-23 signalling pathway is accepted as an important risk factor for SpA development,3 4 the precise mechanism as to how IL-23 drives disease has not been elucidated. A crucial role for enthesitis in SpA pathogenesis is supported by observations in murine models where either TNFα or IL-23/17 pathway dysregulation leads to inflammation that spreads to adjacent synovium and bone.5–8 A poorly defined non-conventional population of lymphocytes was originally shown to be responsible for this murine entheseal pathology.6 It was subsequently shown that an entheseal resident population of γδT-cells were the primary source of IL-17A consequent to IL-23 overexpression.9

γδT-cells are non-conventional T-cells that express the γδ form of the T-cell receptor (TCR) rather than the αβ form expressed by most T lymphocytes.10 In comparison to αβT-cells, γδT-cells have a limited repertoire of V gene segment rearrangements and are thought to participate more extensively in innate immunity and homeostatic processes.10 11 In adults, γδT-cells expressing a Vδ1 domain constitute a minority of the blood γδT-cell population and are reported to recognise several unconventional MHC superfamily members which may present lipids or are stress induced.10 The Vδ2 subsets are by contrast the major subsets present in the blood and react to pyrophosphate molecules.12 However, both subsets have been shown to be capable of producing IL-1713 and mouse studies have shown the importance of the IL-17 producing γδT-cells in wound healing and osteogenesis.14

Recent studies have pointed to the non-efficacy of anti-IL-23 therapy for ankylosing spondylitis,10 whereas anti-IL-17A therapy is effective in AS.15 16 A potential explanation for this surprising finding is that early experimental SpA, but not established disease, is dependent on IL-23,17 which points to the importance of innate immunity in disease onset. Therefore, this study investigated whether the normal human enthesis had resident entheseal γδT-cells, key cells in innate immune responses and focused on the IL-23/17 axis.

Methods

Participants and samples

Human entheseal soft tissue (EST) and peri-entheseal bone (PEB) (figure 1A) were harvested as previousy described18 from normal spinous process and interspinous ligament of 34 patients (14 men, 25 women, median age 53) undergoing spinal surgery at the Leeds General Infirmary for correction of scoliosis or spinal decompression of thoracic or lumbar vertebrae. Entheseal tissue donors were not known or suspected to have any systemic inflammatory condition including SpA.

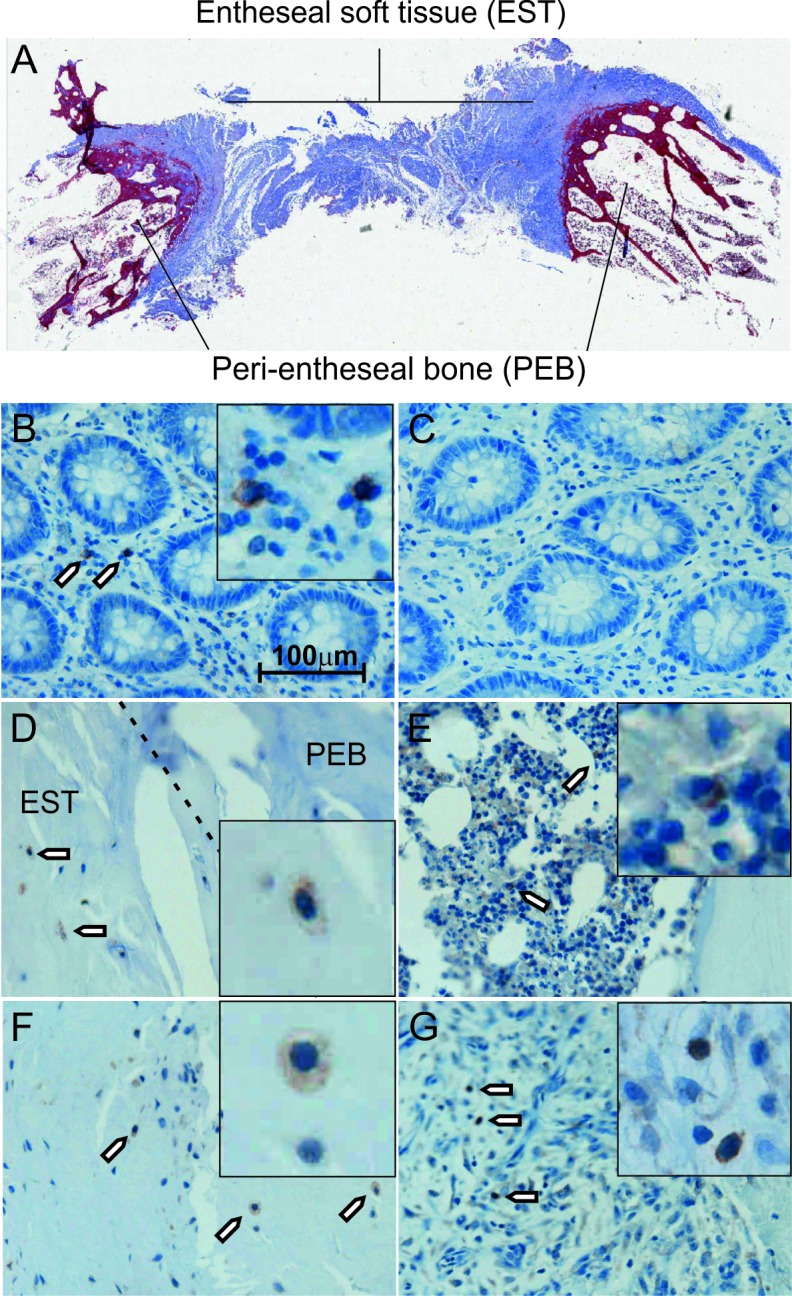

Figure 1.

γδT-cell localisation and phenotyping. Masson’s trichrome stained section showing the area of the spine harvested for analysis. Outer edges of the spinous process are labelled peri-entheseal bone (PEB) and the interspinous ligament labelled entheseal soft tissue (EST) (A). Immunohistochemistry showing γδT-cell receptor expression in human colon tissue, inset shows high power image (B). Staining is absent with omission of the primary antibody (C). Positive staining is observed in the border between the EST and the PEB (D) as well as in the haematopoietic bone marrow (E) and deeper within the EST (F). Inflammatory infiltrate of ruptured Achilles also contains positively stained cells (G). Brown colour and arrows indicate regions of positive staining.

Blood was collected from 20 patients with SpA (15 men, 5 women, median age 44) as well as 14 healthy controls (6 men, 8 women, median age 38). To determine whether γδT-cells might be present at sites of enthesis damage, tissue was procured from the peri-entheseal rupture site of patients undergoing surgical repair of ruptured Achilles’ tendons (n=3). The investigation was approved by North West-Greater Manchester West Research Ethics Committee and Leeds East Research Ethics Committee. Patients gave informed consent in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Immunohistochemistry

Enthesis samples were fixed by incubation in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 hours and then decalcified by incubation in 0.5 M EDTA solution. Histological sections of decalcified, entheseal tissue were stained using the Envision (Dako) immunohistochemistry staining kit. Slides were incubated with anti-TCRδ antibody (online supplementary table 1), diluted 1:20 in antibody diluent (Dako) and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Staining then proceeded as previously described.18

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp001.pdf (84.5KB, pdf)

Cell staining prior to sorting and flow cytometry

EST was separated from PEB and both were enzymatically digested as previously described,18 following which, erythrocytes were removed by incubation in ammonium chloride buffer. Prior to incubation with antibodies, cells were incubated in a blocking buffer (10% mouse serum and 1% human IgG in PBS) for 15 min at room temperature. All antibody incubations were performed at room temperature for 15 min (online supplementary table 1). Cells were sorted using an Influx (BD) cell sorter directly into RNA extraction buffer supplied as a component of the PicoPure RNA isolation kit (Thermo Fisher), which was then used throughout for RNA isolation.

For phenotypic characterisation, cells from each subset were categorised as naïve (CD45RAhi, CD45ROlo) tissue resident memory (CD45RAlo, CD45ROhi, CD69hi, CD103hi, CCR7lo), effector memory (CD45RAlo, CD45ROhi, CCR7lo) and central memory (CD45RAlo, CD45ROhi, CCR7hi).

Magnetic bead enrichment and stimulation assays

For magnetic bead enrichment, mononuclear cells were isolated using Lymphoprep (Axis Shield) and blocked as previously described. Cells were incubated with biotinylated antibodies for 15 min at room temperature, then incubated with anti-biotin microbeads (Miltenyi) for 15 min at 4°C and isolated by two rounds of magnetic separation using MS columns (Miltenyi). For post-enrichment activation, subsets were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin as above or with a combination of anti-CD3/CD28 or 100 ng/mL IL-23 for 48 hours.

Transcript analysis

Transcript analysis was performed by qPCR using the Biomark HD gene expression system (Fluidigm). Briefly, cDNA was reverse transcribed using reverse transcription master mix (Fluidigm) and then underwent pre-amplification (18 cycles) using a pre-amp master mix (Fluidigm) with a solution containing all primer sets. Gene expression was then measured using a dynamic array integrated fluidic circuit (Fluidigm), Taqman gene expression assays and universal Taqman master mix (both Thermofisher). We focused on genes involved in tissue repair, cytokine signalling and signal transduction, pattern recognition and chemokine signalling. A subset of samples were also analysed for expression of genes associated with tissue residence (online supplementary table 2). Expression of all genes was measured relative to HPRT, and qPCR for PMA-induced cytokine expression was performed using a Quant Studio real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp002.pdf (62.6KB, pdf)

Measurement of IL-17A by high - sensitivity ELISA

The γδ subsets (δ1 and δ2) were isolated as previously described. Cells were stimulated with PMA (25 µg/mL) and ionomycin (1 µg/mL) for 1 hour in standard culture conditions. The supernatant was removed and replaced with fresh media (RPMI 1640) and the cells were returned to standard culture conditions for 24 hours. Cell supernatant was tested for IL-17A protein using IL-17A high-sensitivity (0.25–16 pg/mL sensitivity range) ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistics

An independent sample Mann-Whitney U test was used to detect differences in γδT-cell subset distribution between EST, PEB and peripheral blood (PB). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to detect the differences between expression of tissue residency associated transcripts and IL-23/IL-17 axis transcripts in γδT-cell subsets from EST, PEB and PB. To compare the overall changes in transcript abundance between γδT-cells from entheseal tissue and PB, all γδT-cell subsets in both EST and PEB were grouped together and compared with all γδT-cell subsets in PB and a Mann–Whitney U test was used to detect statistical difference. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to detect statistical difference in intracellular cytokine protein expression and a Mann-Whitney U test was used to detect changes in cytokine transcript expression following PMA stimulation. Unless otherwise stated, all box plots display median—line, box—IQR and whiskers—range, all bar graphs display median—box, whiskers—IQR. All graphs were generated using Prism V.7 (GraphPad), and all statistical tests were performed using SPSS V.21 (IBM).

Results

Immunohistochemistry

Positive staining for the γδ TCR was observed in control human colon tissue in the stromal compartment (figure 1B), and γδT-cells were rare as is consistent with previously published research.19 The negative control (omission of the primary antibody) showed a total lack of positive staining (figure 1C). γδT-cells were observed in entheseal tissue at the bone/soft tissue border (figure 1D) as well as in the PEB anchoring region haematopoietic bone marrow (figure 1E) and in the soft tissue of the ligament (figure 1F). γδT-cells were also observed in inflammatory infiltrate in ruptured Achilles tissue, also indicating their presence at the sites of injury (figure 1G).

Phenotypic characterisation

For flow cytometry analysis, live cells were discriminated based on 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) exclusion. T-cells were selected based on positive expression of CD45 and CD3 with a pan-γδ TCR antibody used in combination with Vδ1 and Vδ2 isoform-specific antibodies identified Vδ1+, Vδ2+ and Vδ3–6 (Vδ1,Vδ2 double negative) γδT-cell subsets (figure 2A). Healthy EST (n=11) contained a similar proportion of γδ subsets (37% Vδ1% and 57% Vδ2) as was observed in peripheral blood (n=14) (22% Vδ1% and 67% Vδ2). PEB contained a higher proportion of the Vδ1 subset and a lower proportion of the Vδ2 subset (49% and 34%, p=0.031 and 0.027, respectively). The proportion of γδT-cells which were Vδ1, Vδ2 double negative was consistently low (~7%) with no significant difference observed between groups (figure 2B). Blood from patients with PsA or AS (n=20) showed no difference in the proportion of each subset compared with healthy controls (figure 2C). Similarly no significant difference was observed in patients’ blood with active disease compared with those in remission (data not shown).

Figure 2.

γδT-cell phenotyping in blood and enthesis using flow cytometry. γδT-cells were identified based on positive expression of CD45 and CD3 and positive expression of the γδT-cell receptor, and then subdivided based on the Vδ isoform of the receptor expressed (A). In entheseal tissue (n=11), peri-entheseal bone contained a significantly higher proportion of the Vδ1 and a lower proportion of the Vδ2 expressing cells compared with healthy control blood (n=14) (B). There was no difference in subset proportion in spondyloarthritis patients (n=20) compared with healthy controls (C). Analysis of γδ subsets showing naïve, tissue resident memory (TRM), central memory (CM) and effector memory phenotypes (EM) (D). *P<0.05.

Additional phenotypic characterisation for markers of naïve and memory T-cell subsets showed differences between γδT-cell subsets and changes associated with tissue origin. The Vδ1 subset had a far greater proportion of cells with a naïve phenotype compared with the Vδ2 irrespective of tissue origin (p=0.001) and the Vδ1 subset from PEB contained a greater proportion of the tissue resident memory phenotype compared those from blood (p=0.43) (figure 2D).

Transcriptional profile for tissue residency and immunomodulatory status

Analysis of transcripts associated with tissue residency showed significantly increased expression in entheseal derived Vδ1, Vδ2 and Vδ3–6 subsets (n=12) compared with those derived from peripheral blood (n=6). TGFβ1 was increased on average 5.4-fold (p=0.010, 0.012 and 0.014, respectively) and NR4A1, 7.4-fold (p=0.005, 0.016 and 0.041, respectively).20 This pattern was reversed in genes with reported lower expression in tissue resident T-cells,20 with lower expression in entheseal derived Vδ1, Vδ2 and Vδ3–6 subsets of KLF2, 533-fold (p=0.004, 0.034 and 0.009, respectively) and TBX21 6.9-fold (p=0.036 and 0.011, respectively) although in this case only in entheseal derived Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets (figure 3A).

Figure 3.

γδT-cells in enthesis and blood are transcriptionally distinct. Unmatched entheseal tissue derived subsets were compared with healthy blood derived cells. They had significantly higher expression of transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1), nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group a member 1 (Nr4a1) and lower expression of Krupple-like factor 2 (KLF2) and T-box 21 (TBX21) (A). All γδT-cell subsets expressed high levels of signal transduction molecules and immunomodulatory genes, Expression of IL-23/IL-17 axis cytokines was low or absent. Colour denotes relative expression to HPRT blue-low, black-equal, yellow-high, grey-below detection, Arrows indicate higher expression in γδT-cells (all subsets) from entheseal tissue (EST and PEB) compared with blood. Numbers show difference in median relative abundance. The ‘un-sorted’ category represents gene expression in an unsorted mixture of all cells released from entheseal digests (B) (PEB n=12, EST n=12, PB n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01. EST, entheseal soft tissue; PEB, peri-entheseal bone.

Transcriptional analysis of all γδT-cell subsets derived from entheseal tissue (n=12) compared with those derived from blood (n=6) showed increased expression of growth factor transcripts including BMP-2 and VEGFA (p=0.008 and <0.001), as well as immunomodulatory factors including IL-10, TGF β and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) (all p<0.001). All subsets strongly expressed JAK/STAT signal transduction genes and had little or undetectable expression of IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 (Figure 3B and online supplementary figure 1).

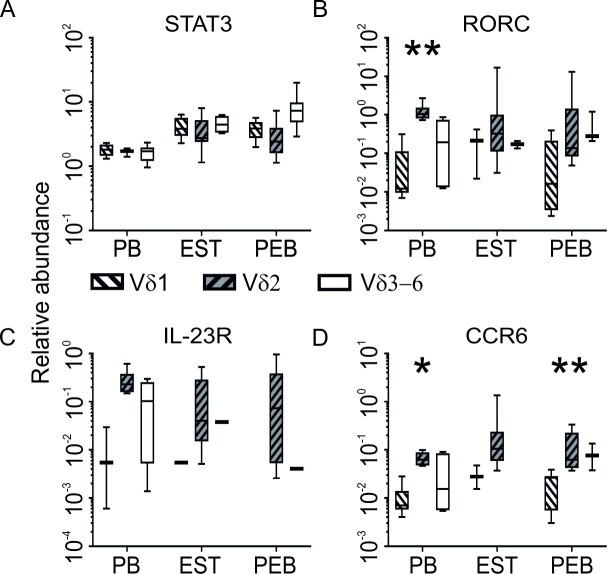

Different IL-23/17 axis transcriptional profile between Vδ1 and Vδ2 cells

STAT3 expression was significantly increased in Vδ1, and Vδ3–6 tissue derived subsets in comparison with age matched blood (both p=0.003) with a strong trend were observed in the Vδ2 subset (p=0.065, figure 4A). Expression of RORC, IL-23R and CCR6 (figure 4B–D) was consistently higher in the Vδ2 subset compared with Vδ1. Although loss of detectable expression in low expressing subsets rendered statistical analysis problematic, significance was achieved in CCR6 expression in PEB (p=0.004). IL-23R expression was consistently detected in the Vδ2 subset but was largely absent in entheseal derived Vδ1 and Vδ3–6 subsets. IL-23R transcript was detected at a low level in 1 of 12 samples in each case in EST and in one sample in the Vδ3–6 subset in PEB (figure 4C).

Figure 4.

The Vδ2 subset expressed higher levels of genes involved or associated with IL-23-driven IL-17 signalling. Entheseal tissue derived subsets had generally higher expression of STAT3 compared with blood (A) and the Vδ2 subset had the highest expression of RORC (B), IL-23R (C) and CCR6 transcript (D) (PEB n=12, EST n=12, PB n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01. EST, entheseal soft tissue; PEB, peri-entheseal bone.

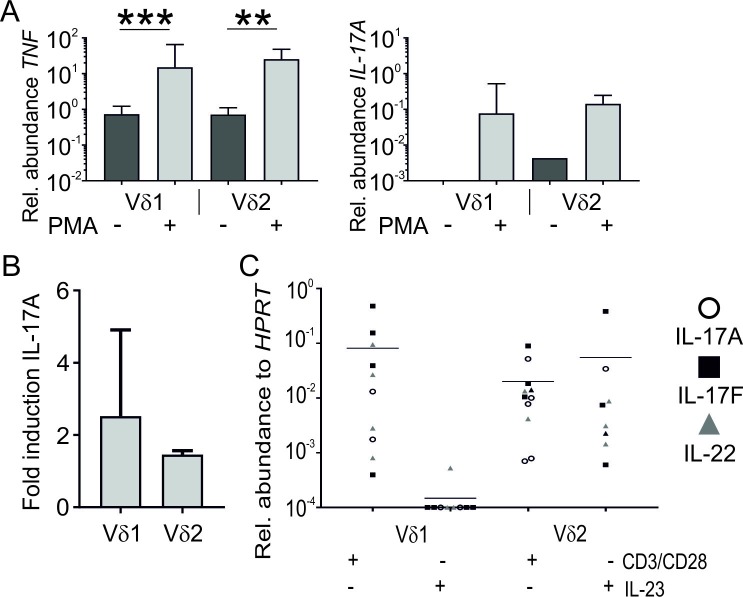

IL-17 production in γδT-cell subsets

Next, the ability of entheseal γδT-cell subsets to produce the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22 and TNFα was assessed using ELISA and qPCR. In PMA and ionomycin stimulated γδT-cell subsets, TNFα transcript expression was significantly increased in Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets (p=0.001 0.002, respectively) (figure 5A). IL-17A was not detected without stimulation but was detected following stimulation (figure 5A) in both Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets. Additionally, high-sensitivity ELISA confirmed an increase in IL-17A production in both subsets on PMA/ionomycin stimulation in the Vδ1 fraction, the mean basal level was 0.70 pg/mL and this rose to 1.60 pg/mL (2.28-fold). In the Vδ2 fraction, basal level was 15.56 pg/mL and this rose to 23.30 pg/mL (1.49-fold) (figure 5B). However, the low number of cells made accurate determination of cell number problematic, therefore although the number of input cells used in stimulated and unstimulated conditions was comparable within subsets, caution should be used in comparing IL-17A concentrations between Vδ subsets.

Figure 5.

TNFα and IL-17A are produced by both γδT-cell subsets quantitative PCR showing TNFα and IL-17A transcript expression in γδT-cell subsets with or without stimulation (n=8) (A). Fold induction of secreted IL-17A protein following PMA/ionomycin stimulation compared with unstimulated fraction of purified Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets (n=3) bar shows that mean whiskers represent 1 SD (B). Transcript expression of IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 following 48-hour stimulation of Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets with combined anti-CD3/CD28 or IL-23 stimulation (n=10). Line denotes mean expression (all genes combined) (C). Genes for which a housekeeping value was obtained, but for which a target value was not, were assigned a value of 0.0001, as 0 cannot be plotted on a log scale. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P≤0.001.

Next we assessed the impact of more physiological stimuli on both Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets expression of IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 cytokine transcripts. Following stimulation with a combination of anti-CD3/CD28, robust detection of IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 transcripts was observed in Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets (figure 5C). In contrast, IL-23 stimulation had almost no effect in the Vδ1 subset but caused a marked increase in the Vδ2 subset (figure 5C). Finally, we ascertained whether this equated with measurable IL-17A protein detection using the highly sensitive ELISA. Unlike PMA stimulation, we could not detect changes in IL-17A protein using either CD3/CD28 or IL-23 stimulation (online supplementary file 5)).

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp005.pdf (67.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

The γδT-cell population is responsible for the majority of the IL-17A produced at the enthesis in IL-23 dependent murine models of SpA.6 9 Herein, we describe γδT-cell populations at the normal and injured human enthesis by immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry and provide evidence supporting their entheseal residency. We defined both Vδ1 and Vδ2 entheseal resident cells but only Vδ2 subset consistently expressed high levels of transcripts associated with IL-17/IL-23 axis cytokine signalling, namely RORC, IL-23R and CCR6.21 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of enthesis resident γδT-cells in man and fits in with the knowledge of their role in skin and gut disease in general and other recent studies from peripheral blood and synovial fluid in spondyloarthritis pointing to a key role in disease.22

Following PMA stimulation, IL-17A production was also detected in both the Vδ1 and Vδ2 populations by high-sensitivity ELISA and this was confirmed by qPCR. Furthermore, qPCR on both subpopulations stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 or IL-23 confirmed that IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 production could be driven in the absence of IL-23 and supports the assertion that the Vδ1 subset do not express IL-23R under basal conditions in entheseal tissue. Since IL-23R transcript expression was absent in 11 of 12 Vδ1 subset isolates, this suggests a potential for this population to produce IL-17A in an IL-23 independent manner. We demonstrated IL-17A protein production in both populations using PMA/ionomycin although this is a non-physiological stimulus. Nevertheless, PMA been used extensively to demonstrate the functional characteristics of cells although we acknowledge that the potential functional drives in vivo in man need to be defined.

Also, in the present work, we noted low level IL-23R transcript expression in the peripheral blood Vδ1 subset. It has also been previously shown that IL-23R expression is upregulated following anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation of Th17 -cells, thus meaning any potential IL-17 secretion independent of IL-23 is hard to prove in the current setting.23 This highlights the potential plasticity of these cells and may explain differences observed between circulating and entheseal resident γδT-cells. It also suggests that IL-23 cannot be excluded from driving IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 production in these cells in the disease environment.

A lower proportion of the Vδ2 subset was observed in entheseal tissue compared with blood suggesting potential enrichment of a tissue homing phenotype, since γδT-cells are known to migrate and reside in tissues based on specific isoform expression.11 Alternatively, this may represent the expansion of a resident population. We did not observe a change in the distribution of subsets in the blood of SpA patients where the subset distribution was similar to healthy controls (figure 2). Analysis of entheseal γδT-cell transcripts that have been suggested to correlate with tissue localisation of T-cells in general20 showed clear disparities from those isolated from blood. TGFβ1 and NR4A1 (nuclear hormone receptor NUR/77) were more highly expressed in entheseal γδT-cell subsets compared with those isolated from blood. The expression of KLF2 (Krupple-like factor 2) was more than two orders of magnitude lower in entheseal derived cells, similarly TBX21 (T-bet) expression was greater in Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets but interestingly not in the Vδ3–6 subsets perhaps reflecting a stronger Th1-like phenotype in these cells.24 The modulation of these genes on tissue residence has largely been elucidated in the context of conventional T-cells.25–28 However, the striking changes observed in this study suggest that these findings can be applied more broadly, including to γδT-cells and add additional verification that the γδT-cells derived from entheseal tissues are a distinct tissue resident population.

Further transcriptome analysis showed increased expression of genes relevant to bone repair including BMP-2 29 and angiogenesis, VEGFA 30 in entheseal γδT-cell populations compared with those isolated from blood. IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 are expressed at low levels or absent and cytokines associated with an immunomodulatory phenotype, TGFβ and IL-10 31 32 are increased in entheseal cells. Following in vitro activation of these cells TNFα and IL-17A protein were readily detectable.

It has previously been shown that the γδT-cells produced IL-17A in the absence of IL-23R. The importance of IL-23 independent IL-17 production was first highlighted in the colon where inhibition of IL-17A but not IL-23 led to loss of barrier integrity, an effect that was attributed to IL-23 independent IL-17A production in γδT-cells.33 Analogous to this study, this work suggests that IL-17A protein expression can occur independently of IL-23 in spinal derived tissue. However, the in vivo basis for this in axial SpA remains conjectural but could involve activation of different pattern recognition receptors at entheses which needs further exploration. Noting that there is evidence for IL-23 inhibition efficacy in peripheral psoriatic arthritis,34 35 the putative differences between spinal and peripheral entheses that might underscore this observation need exploration.

Given the recent reports that IL-17A inhibition works in AS but IL-23 inhibition does not,15 36 these findings point towards a potential IL-23 independent innate immune pathway that may provide insights into understanding the clinical scenario. Indeed, the demonstration that IL-23 plays a role in innate (disease initiation) but not adaptive immunity in experimental SpA supports this view.17 Further studies looking at peripheral entheses and entheseal spinal or sacroiliac tissue from active SpA are needed. However, these findings highlight a potentially pivotal role for γδT-cells in spinal innate immunity in SpA.

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp003.pdf (6.8MB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp004.pdf (5.2MB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. RJC is supported by a Pfizer investigator initiated research grant, CB is supported by a Novartis Global research grant. This work has been previously presented at the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2017 annual meeting and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2018 annual meeting.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

CB and DGM contributed equally.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it published Online First. The author affiliations and order of authors have been updated.

Contributors: The listed authors made the following contributions to this manuscript: Experimental design—RJC, CB, AD, DGM, DN. Preparing the manuscript—RJC, CB, AW, EMF, PL, RD, AK, PM, AD, HMO, DN, DGM. Performing the experiments—RJC, CB, EMF, RD, PL, AK, PM, AD. Study concept—RJC, CB, DN, DMG. Final approval—RJC, CB, AW, HMO, DN, DMG.

Funding: Novartis Global research grant (CB), Pfizer investigator initiated research grant (RJC).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Leeds East Research Ethics Committee 06/Q1206/127, Greater Manchester West Ethics Committee 16/NW/0797.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Taurog JD, Chhabra A, Colbert RA. Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;374:2563–74. 10.1056/NEJMra1406182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jacques P, Lambrecht S, Verheugen E, et al. Proof of concept: enthesitis and new bone formation in spondyloarthritis are driven by mechanical strain and stromal cells. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:437–45. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lubberts E. The IL-23–IL-17 axis in inflammatory arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:415–29. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rahman P, Inman RD, Gladman DD, et al. Association of interleukin-23 receptor variants with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2008;58:1020–5. 10.1002/art.23389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGonagle D, Gibbon W, Emery P. Classification of inflammatory arthritis by enthesitis. The Lancet 1998;352:1137–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12004-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-γt+ CD3+CD4−CD8− entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med 2012;18:1069–76. 10.1038/nm.2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lories RJU, Derese I, de Bari C, et al. Evidence for uncoupling of inflammation and joint remodeling in a mouse model of spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:489–97. 10.1002/art.22372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Armaka M, Apostolaki M, Jacques P, et al. Mesenchymal cell targeting by TNF as a common pathogenic principle in chronic inflammatory joint and intestinal diseases. J Exp Med 2008;205:331–7. 10.1084/jem.20070906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reinhardt A, Yevsa T, Worbs T, et al. IL‐23‐dependent γδ T cells produce IL‐17 and accumulate in enthesis, aortic valve, and ciliary body. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2476–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adams EJ, Gu S, Luoma AM. Human gamma delta T cells: evolution and ligand recognition. Cell Immunol 2015;296:31–40. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, Havran WL. γδ T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 2017;17:733–45. 10.1038/nri.2017.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gu S, Nawrocka W, Adams EJ. Sensing of pyrophosphate metabolites by Vγ9Vδ2 T. Front Immunol 2015;688 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lawand M, Déchanet-Merville J, Dieu-Nosjean M-C. Key features of gamma-delta T-cell subsets in human diseases and their immunotherapeutic implications. Front Immunol 2017;8:761 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ono T, Okamoto K, Nakashima T, et al. IL-17-producing [gamma][delta] T cells enhance bone regeneration. Nature communications 2016;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dubash S, Bridgewood C, McGonagle D, et al. The advent of IL-17A blockade in ankylosing spondylitis: secukinumab, ixekizumab and beyond. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019;15:123–34. 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1561281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Tok MN, Na S, Lao CR, et al. The initiation, but not the persistence, of experimental spondyloarthritis is dependent on interleukin-23 signaling. Front Immunol 2018;9 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cuthbert RJ, Fragkakis EM, Dunsmuir R, et al. Brief report: group 3 innate lymphoid cells in human Enthesis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1816–22. 10.1002/art.40150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fukushima K, Masuda T, Ohtani H, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization, distribution and ultrastructure of lymphocytes bearing the gamma/delta T-cell receptor in the human gut. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol 1991;60:7–13. 10.1007/BF02899521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mackay LK, Kallies A. Transcriptional regulation of tissue-resident lymphocytes. Trends Immunol 2017;38:94–103. 10.1016/j.it.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, et al. The IL-23–IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:585–600. 10.1038/nri3707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Venken K, Jacques P, Mortier C, et al. Rorγt inhibition selectively targets IL-17 producing iNKT and γδ-T cells enriched in spondyloarthritis patients. Nat Commun 2019;10:9 10.1038/s41467-018-07911-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Wit J, Souwer Y, van Beelen AJ, et al. Cd5 costimulation induces stable Th17 development by promoting IL-23R expression and sustained STAT3 activation. Blood 2011;118:6107–14. 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hertweck A, Evans CM, Eskandarpour M, et al. T-Bet activates Th1 genes through mediator and the super elongation complex. Cell Rep 2016;15:2756–70. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hombrink P, Helbig C, Backer RA, et al. Programs for the persistence, vigilance and control of human CD8+ lung-resident memory T cells. Nat Immunol 2016;17:1467–78. 10.1038/ni.3589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skon CN, Lee J-Y, Anderson KG, et al. Transcriptional downregulation of S1PR1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol 2013;14:1285–93. 10.1038/ni.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boddupalli CS, Nair S, Gray SM, et al. ABC transporters and Nr4a1 identify a quiescent subset of tissue-resident memory T cells. J Clin Invest 2016;126:3905–16. 10.1172/JCI85329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mackay LK, Wynne-Jones E, Freestone D, et al. T-Box transcription factors combine with the cytokines TGF-β and IL-15 to control tissue-resident memory T cell fate. Immunity 2015;43:1101–11. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gamer LW, Pregizer S, Gamer J, et al. The role of Bmp2 in the maturation and maintenance of the murine knee joint. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2018;33:1708–17. 10.1002/jbmr.3441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeon HH, Yu Q, Lu Y, et al. FOXO1 regulates VEGFA expression and promotes angiogenesis in healing wounds. J Pathol 2018;245:258–64. 10.1002/path.5075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diefenhardt P, Nosko A, Kluger MA, et al. Il-10 receptor signaling empowers regulatory T cells to control Th17 responses and protect from GN. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;29:1825–37. 10.1681/ASN.2017091044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shidal C, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. MicroRNA-92 expression in CD133+ melanoma stem cells regulates immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment through integrin-dependent TGF-β activation. Am Assoc Immnol 2018;79:3622–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee JS, Tato CM, Joyce-Shaikh B, et al. Interleukin-23-independent IL-17 production regulates intestinal epithelial permeability. Immunity 2015;43:727–38. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Deodhar A, Gottlieb A, Boehncke W-H, et al. OP0308 efficacy and safety results of guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis over 56 weeks from a phase 2A, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2018;77:201. [Google Scholar]

- 35. McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. The Lancet 2013;382:780–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60594-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baeten D, Østergaard M, Wei JC-C, et al. Risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, for ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept, dose-finding phase 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1295–302. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp001.pdf (84.5KB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp002.pdf (62.6KB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp005.pdf (67.2KB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp003.pdf (6.8MB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2019-215210supp004.pdf (5.2MB, pdf)