Abstract

Here, I address the topic of suitability for redox research of common settings in cell cultures. This is done through the prism of in vitro anticancer effects of vitamin C. Cell culture media show lower concentrations of iron and a higher level of oxygen compared to interstitial fluid. Such a setup promotes ascorbate-mediated production and accumulation of hydrogen peroxide, which efficiently kills a variety of cancer cell lines. However, the anticancer effects are annihilated if the iron level is corrected to mimic in vivo concentrations. It appears that the potential benefits of application of vitamin C in cancer treatment have been significantly overestimated. This might be true for other pro-oxidative agents as well, such as some (poly)phenols. We urgently need to establish medium formula and culture maintenance settings that are optimal for redox research.

Keywords: Cell culture, Iron, Ascorbate, Cancer

Commercial cell culture media, such as DMEM or RPMI-1640 supplemented with (usually) 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), are built to mimic extracellular milieu, i.e. interstitial fluid. Apparently, on many accounts they do. Different types of cultured cells efficaciously grow and proliferate in those media, and there are thousands of cell culture studies conducted each year, some of them in the redox field. For example, about 250 papers were published in 2014, containing a combination of terms ‘antioxidant’ in the Title/Abstract section and ‘cell culture’ in All Fields (source: PubMed). Pertinent to this, it is clearly of the essence that cell culture media reflect in vivo redox settings as accurately as possible. But what if they do not, and what might be the consequences?

It is believed that the concentration of iron in interstitial fluid (outside the CNS) closely mirrors the range (10–30 µM) found in the plasma.1,2 The presence of different complexes and the susceptibility of iron in interstitial fluid to reduction and oxidation are not known, but cell culture media fail to reproduce even the concentration. DMEM contains only 0.25 µM ferric nitrate, whereas in RPMI-1640 iron probably exists via impurities. The level of iron in fetal calf serum (FCS) is not consistent and varies between manufacturers and batches. In the end, the concentration of iron does not exceed 5 µM in cell culture media with 10% (v/v) FCS.3,4 The concentration of oxygen represents another major problem of redox research in cell cultures, as repeatedly pointed out by Halliwell.5,6 Cell cultures are kept under 95/5% air/CO2 atmosphere resulting in hyperoxia of the medium (pO2≈150 mmHg) as compared to interstitial fluid, where pO2 is in the 1–10 mmHg range.

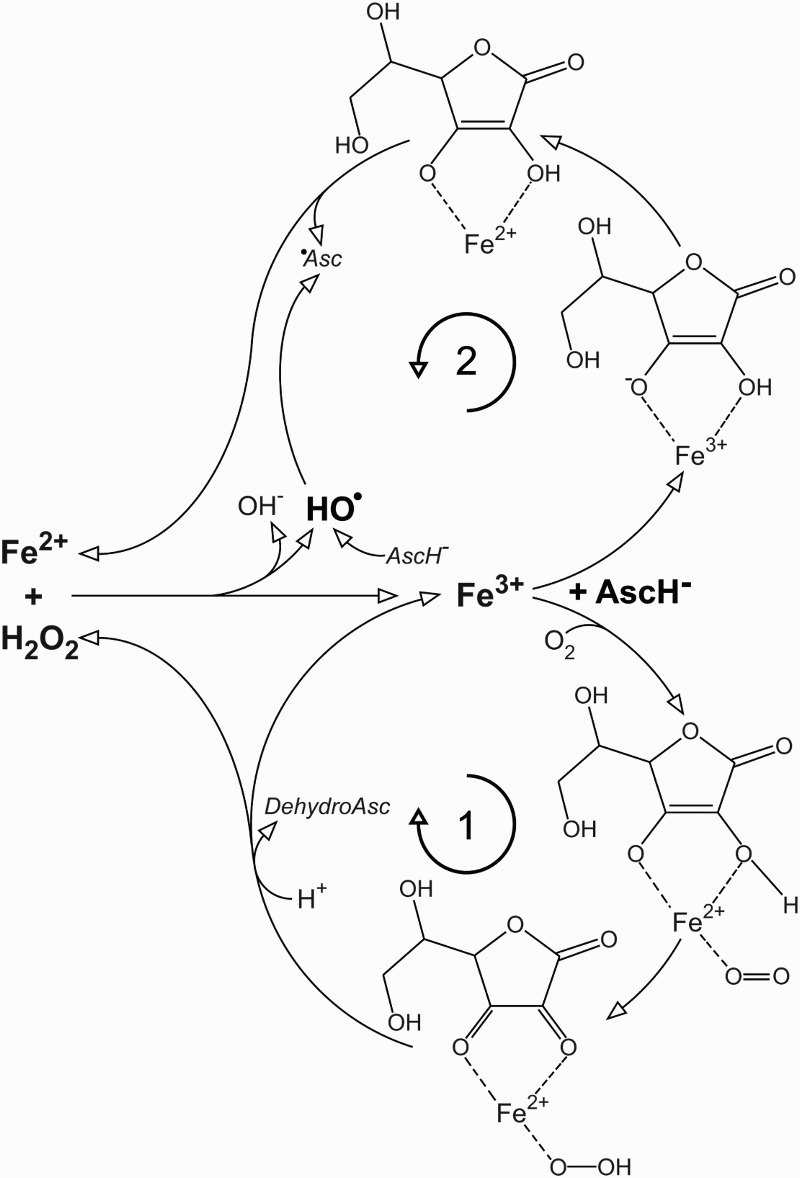

Following over 20 studies on cancer cell lines showing anticancer effects of pharmacological (millimolar) ascorbate, resulting in animal and human trials,7 we have found recently that the supplementation of cell culture medium with as little as 5 µM of iron (to reach the minimal level in interstitial fluid) annihilates any anticancer effects of ascorbate. A similar outcome has been observed when the level of iron was corrected via increased percentage of FCS.8 Briefly, the combination of iron, ascorbate, and O2 in the medium generates H2O2, which enters and kills cancer cells.9 But when iron is present at physiological concentrations it reacts with H2O2 to produce hydroxyl radical, which has an extremely low diffusion radius and cannot affect the cells.8,10 For a more detailed explanation, we need to take a closer look at the ascorbate–iron–oxygen system, which is composed of two branches (Fig. 1). With ascorbate present in excess (μM), O2 and iron concentration are the rate limiting factors. High pO2 in cell culture media promotes branch 1,11 resulting in the accumulation of H2O2. However, branch 1 also consumes O2, so there is a negative feedback present. With the decrease of O2 concentration, branch 1 slows down and branch 2 takes over to reduce Fe3+ to Fe2+, which further removes H2O2 via Fenton chemistry.8 Ascorbyl radical is generated in branch 2 and via hydroxyl radical scavenging. The consumption of O2 and the production of ascorbyl radical are promoted with increasing iron concentrations.8 The balance between accumulation and degradation of H2O2 is defined by the level of iron, and unfortunately it appears that the major switch between these two is placed between the concentrations of iron in cell culture media and in interstitial fluid. Even more, at in vivo O2 level branch 2 should clearly prevail, not allowing the generation/accumulation of H2O2.

Figure 1.

Redox system composed of iron, ascorbate, and molecular oxygen. Two main branches are marked with 1 and 2. Asc, ascorbate; HO•, hydroxyl radical; •Asc, ascorbyl radical.

An immediate cause for this commentary is the recently published paper by Du et al., entitled ‘The role of labile iron in the toxicity of pharmacological ascorbate’.12 The authors have cited our work and recognized that extracellular iron can save cancer cells from ascorbate-related H2O2 production but the study, like many before, was conducted in DMEM with 10% FCS. The focus was on the modulation of intracellular level of iron, and it has been presumed that the influx of H2O2 from the ascorbate-supplemented medium is (patho)physiologically relevant. The discussion is closed by the following suggestion: ‘However, increasing the level of extracellular as well as intracellular catalytically active labile iron in tumor tissue may enhance the effectiveness of pharmacological ascorbate as an adjuvant in cancer therapy’, although the level of extracellular iron was not taken into consideration as an experimental parameter, and in spite of our findings that the increase of extracellular iron in the medium (from 5 to 10–30 µM; in fact, we went up to 100 µM – unpublished data) completely prevents anticancer effects of ascorbate.8

If we, scientists directly involved in the redox field, continue to keep our eyes closed to this and other technical but fundamental problems, the road is paved for researchers in lucrative fields, such as food industry, pharmacy, and cosmetic industry to develop ‘powerful new antioxidants’, and to compromise our efforts. We cannot act surprised by the fact that promising results from in vitro redox studies are rarely translated into success in human clinical trials. For example, at least some phenolic compounds produce H2O2 in cell culture media and exert in vitro anticancer effects via mechanisms that appear to be similar to ascorbate.13,14 So it is no wonder that clear benefits for cancer patients (such as tumor regression or prolonged survival) from the application of (poly) phenolics are still missing in spite of a number of finished clinical trials.15

To conclude, we urgently need to determine redox properties of interstitial fluid, including the redox activity of iron and the level of endogenous antioxidants and antioxidative enzymes, and to define medium formula and culture maintenance settings that are optimal for redox research. Similarly to medical associations and their guidelines for patient treatment, the societies interested in free radicals might provide recommendations for redox research. Our field has yet much to offer and must not be jeopardized.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia, grant number OI173014.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding None.

Conflict of interest None.

Ethics approval None.

References

- 1.Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and disorders of iron metabolism. Annu Rev Med 2011;62:347–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050109-142444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavill I, Staddon G, Jacobs A. Iron kinetics in the skin of patients with iron overload. J Invest Dermatol 1972;58(2):96–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12551708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kakuta K, Orino K, Yamamoto S, Watanabe K. High levels of ferritin and its iron in fetal bovine serum. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol 1997;118(1):165–69. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9629(96)00403-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wesselius LJ, Williams WL, Bailey K, Vamos S, O'Brien-Ladner AR, Wiegmann T. Iron uptake promotes hyperoxic injury to alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159(1):100–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9801033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress in cell culture: an under-appreciated problem? FEBS Lett 2003;540(1–3):3–6. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00235-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliwell B. Cell culture, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: avoiding pitfalls. Biomed J 2014;37(3):99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parrow NL, Leshin JA, Levine M. Parenteral ascorbate as a cancer therapeutic: a reassessment based on pharmacokinetics. Antioxid Redox Sign 2013;19(17):2141–56. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mojić M, Bogdanović Pristov J, Maksimović-Ivanić D, Jones DR, Stanić M, Mijatović S, Spasojević I. Extracellular iron diminishes anticancer effects of vitamin C: an in vitro study. Sci Rep 2014;4:5955. doi: 10.1038/srep05955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Q, Espey MG, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Corpe CP, Buettner GR, et al. Pharmacologic ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: action as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102(38):13604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506390102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hempel SL, Buettner GR, Wessels DA, Galvan GM, O'Malley YQ. Extracellular iron (II) can protect cells from hydrogen peroxide. Arch Biochem Biophys 1996;330(2):401–8. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taqui Khan MM, Martell AE. Metal ion and metal chelate catalyzed oxidation of ascorbic acid by molecular oxygen. I. Cupric and ferric ion catalyzed oxidation. J Am Chem Soc 1967;89(16):4176–85. doi: 10.1021/ja00992a036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du J, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Cullen JJ. The role of labile iron in the toxicity of pharmacological ascorbate. Free Radic Biol Med 2015;88:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long LH, Clement MV, Halliwell B. Artifacts in cell culture: rapid generation of hydrogen peroxide on addition of (–)-epigallocatechin, (–)-epigallocatechin gallate, (+)-catechin, and quercetin to commonly used cell culture media. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;273(1):50–3. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long LH, Kirkland D, Whitwell J, Halliwell B. Different cytotoxic and clastogenic effects of epigallocatechin gallate in various cell-culture media due to variable rates of its oxidation in the culture medium. Mutat Res 2007;634(1–2):177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carocho M, Ferreira IC. The role of phenolic compounds in the fight against cancer – a review. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2013;13(8):1236–58. doi: 10.2174/18715206113139990301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]