Abstract

Protein tyrosine nitration is an oxidative postranslational modification that can affect protein structure and function. It is mediated in vivo by the production of nitric oxide-derived reactive nitrogen species (RNS), including peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and nitrogen dioxide (•NO2). Redox-active transition metals such as iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn) can actively participate in the processes of tyrosine nitration in biological systems, as they catalyze the production of both reactive oxygen species and RNS, enhance nitration yields and provide site-specificity to this process. Early after the discovery that protein tyrosine nitration can occur under biologically relevant conditions, it was shown that some low molecular weight transition-metal centers and metalloproteins could promote peroxynitrite-dependent nitration. Later studies showed that nitration could be achieved by peroxynitrite-independent routes as well, depending on the transition metal-catalyzed oxidation of nitrite (NO2−) to •NO2 in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Processes like these can be achieved either by hemeperoxidase-dependent reactions or by ferrous and cuprous ions through Fenton-type chemistry. Besides the in vitro evidence, there are now several in vivo studies that support the close relationship between transition metal levels and protein tyrosine nitration. So, the contribution of transition metals to the levels of tyrosine nitrated proteins observed under basal conditions and, specially, in disease states related with high levels of these metal ions, seems to be quite clear. Altogether, current evidence unambiguously supports a central role of transition metals in determining the extent and selectivity of protein tyrosine nitration mediated both by peroxynitrite-dependent and independent mechanisms.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, Superoxide, Free radicals, Oxidative stress, Nitration, Transition metals, Hydrogen peroxide, Nitrogen dioxide

Introduction

Transition metals are essential components for all living organisms, as they participate in many key biological processes such as cellular respiration, gene transcription, and many enzymatic reactions. Their ability to oscillate between different redox states is the main feature that allows them to act as cofactors in most of these processes. In humans, the most abundant are iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn); within the cells, they can be found in different forms: mainly, bound to proteins, but also in association with low molecular weight species and a small fraction as ‘free’ ions.1,2 Due to their redox capability, under certain conditions these transition metals can catalyze the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may lead to oxidative damage of biomolecules, such as proteins and DNA. These ROS include superoxide radicals (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH).3,4

Nitric oxide (•NO) is an endogenously synthesized free radical with many physiological functions, like vasodilation and neurotransmission. However, in the presence of ROS and transition metals, it can give rise to several reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and nitrogen dioxide radical (•NO2). These RNS can mediate the oxidation and nitration of different biomolecules, like the nitration of protein tyrosine (Tyr) residues to 3-nitrotyrosine (NO2Tyr), an oxidative postranslational modification found in many pathological conditions.5,6 Transition metals can also play an important role in this type of oxidative modification, although they are not required for it. In fact, the first protein identified to be nitrated in vitro by biologically relevant nitrating agents (i.e. ONOO−) was a metalloprotein: Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD); the Cu2+ atom of the enzyme was show to be a key element in that process, considerably promoting NO2Tyr formation.7 Besides Cu,Zn SOD, those initial studies showed that low molecular weight transition metal complexes could also catalyze nitration of phenolics by ONOO−.8 As we will discuss below, transition metals can enhance and lead protein tyrosine nitration by several mechanisms and, so, they are undoubtedly necessary for explaining in vivo protein tyrosine nitration.

Biological formation of nitrating species

By the late 1980s, the role of the free radical •NO as an important messenger in biological systems had been establisheded.9–11 Soon after that, it was shown that •NO could also act as a cytotoxic effector molecule when it was overproduced; its capability to participate as a pathogenic mediator depends mainly on the formation of secondary intermediates such as ONOO− and •NO2 that are considerably more reactive and toxic than •NO itself. These RNS are produced from •NO in the presence of other oxidant species like O2•−, H2O2, and transition metal centers.5

Peroxynitrite is a short-lived oxidant species produced in vivo by the extremely fast reaction between •NO and O2•− (k ∼ 1010 M−1 s−1). At physiological pH values, it can exist as the anionic form (ONOO−) and as the peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH; pKa = 6.8); both species can participate directly in one- and two-electron oxidation reactions with biomolecules. The main targets for peroxynitrite in biological systems are thiols, carbon dioxide (CO2) and transition metal centers (Men+X), all of which react directly with either ONOOH or ONOO− with second order rate constants ranging from ∼103 to ∼107 M−1 s−1.12,13 In the absence of other targets, ONOOH decays by homolysis to nitrate (NO3−), producing also •OH and •NO2 with maximum yields of 30% in a first-order reaction that has a rate constant value of 0.9 s−1 (37°C, pH 7.4).13–15 The reaction between ONOO− and CO2 and some reactions of ONOO− with transition metal centers also can produce secondary radicals. In the first case, the nucleophilic addition of ONOO− to CO2 (k = 5.8 × 104 M−1 s−1, 37°C) yields a nitrosoperoxocarboxylate adduct (ONOOCO2−) that undergoes a fast homolysis to •NO2 and carbonate radicals (CO3•−).16,17 Reaction of ONOO− with transition metal centers (both from metalloproteins and from low molecular weight metal complexes) is more complex and can either be a one- or two-electron oxidation of the transition metal, in which ONOO− is reduced to •NO2 or nitrite (NO2−), respectively. As a result of this reaction, the metal center is oxidized to a higher oxidation state oxo-metal complex (O = Me(n+1)+X), a strongly oxidizing species.5,17 The radical species formed from ONOO− direct reactions and its proton-catalyzed homolysis (CO3•−, •NO2, O = Me(n+1)+X, and •OH) are all strong one-electron oxidants able to oxidize a great number of biomolecules and are responsible for many of the observed in vitro and in vivo peroxynitrite-dependent oxidations, like protein tyrosine nitration.5,8,18,19 In contrast, the two-electron oxidation of low molecular weight and protein thiols by ONOOH represents a quite harmless way of ONOO− decomposition, as it generates the oxidized sulfenic acid from the thiol and NO2−.20 The main fate of ONOO− in biological systems is summarized in Fig. 1.

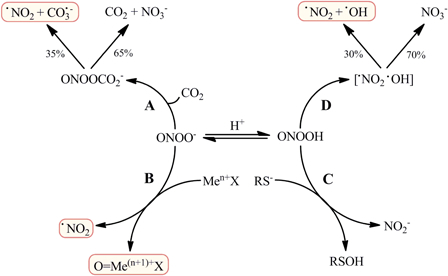

Figure 1.

Principal fate of peroxynitrite in biological systems. Peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−) and its acid form, peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH; pKa = 6.8), coexist at physiological pH values and can undergo direct reactions with several biomolecules, the most important of them being carbon dioxide (CO2), thiols (RS−) and transition metal centers (Men+X). Reaction of ONOO− with CO2 (A) yields a nitrosoperoxocarboxylate adduct (ONOOCO2−), which homolyzes to nitrogen dioxide (•NO2) and carbonate radicals (CO3•−) with 35% yields. Some transition metal centers can reduce ONOO− by one electron (B), producing •NO2 and a high oxidation state oxo-metal complex (O = Me(n+1)+X). Thiols readily react with ONOOH in a two electron oxidation (C), in which the thiol is oxidized to sulfenic acid (RSOH), reducing ONOOH to nitrite (NO2−). Alternatively, ONOOH can undergo homolysis (D) to •NO2 and hydroxyl radical (•OH) with maximum yields of 30%, the remaining decaying to nitrate (NO3−). The species highlighted are all strong one-electron oxidants that mediate much of the oxidative damage associated with peroxynitrite.

Another RNS that accounts for much of •NO-mediated toxicity is •NO2. This radical species undergoes a variety of reactions that include its recombination with other radicals, its addition to double bonds, electron transfer reactions and hydrogen atom abstractions from carbon–hydrogen bonds of unsaturated compounds, phenols and thiols. Of particular relevance are its recombination reactions with lipid- and protein-derived radicals that occur at near diffusion limited rates (k > 109 M−1 s−1) and produce nitrated lipids and proteins.21 As explained before, many ONOO− decomposition pathways can produce •NO2 in vivo; there are, however, other reactions that generate •NO2 in biological systems. The most relevant is the one that involves the peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of NO2−, which is of most relevance under inflammatory conditions. This one-electron oxidation of NO2− is catalyzed by several heme peroxidases (e.g. myeloperoxidase (MPO) and eosinophil peroxidase (EPO)) in the presence of H2O2 and begins with the reaction of the latter with the heme group located at the active site of the peroxidase in a two-electron oxidation (Eq. 1). This oxidation step produces an oxoferryl porphyrin π cation radical intermediate (HP•+-(Fe4+ = O)), known as compound I, which is a strong one- and two-electron oxidant. One of the multiple targets of compound I is NO2−, which is oxidized by one electron to •NO2; as a result, compound I is reduced to the corresponding oxoferryl intermediate (HP-(Fe4+ = O)), known as compound II (Eq. 2). Compound II is also a strong one-electron oxidant that can oxidize NO2− to •NO2 and regenerate the heme peroxidase to its ground state (Eq. 3); this reaction is, however, much slower than the one that implies compound I:22

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Besides heme proteins, free hemin and other low molecular weight metal complexes have been shown to produce •NO2 by this mechanism.23 Finally, another reaction that could generate •NO2 in vivo is the one-electron oxidation of NO2− by •OH,21 but this seems to be a minor route for the biological formation of •NO2 due to the high reactivity and very low selectivity of •OH.

Biochemical mechanisms of tyrosine nitration

Under biological conditions, tyrosine nitration is mediated by free radical reactions in a two-step process: first, the phenolic ring of Tyr is oxidized to its one-electron oxidation product, the tyrosyl radical (Tyr•), and, then, the addition of •NO2 to the Tyr• produces the non-radical product NO2Tyr. Many of the peroxynitrite-derived radicals mentioned earlier can act as the one electron oxidant responsible for producing the Tyr•: CO3•−, O = Me(n+1)+X (both from metalloproteins or low molecular weight metal complexes), •NO2 and •OH.6,24 In hydrophobic environments, some of the intermediates of lipid peroxidation processes, like lipid peroxyl (LOO•) and alkoxyl (LO•) radicals, can also mediate the one-electron oxidation of Tyr, thereby contributing to protein tyrosine nitration in membranes and lipoproteins.25,26

Protein tyrosine nitration then requires a one-electron oxidant to oxidize Tyr to the Tyr•, and also •NO2 to recombine with the Tyr• formed; by several decay pathways, ONOO− produces both species, so it is one of the most relevant agents causing protein tyrosine nitration in vivo. Alternatively, tyrosine nitration can occur by the •NO2 production catalyzed by heme peroxidases in the presence of H2O2 and NO2− that was described previously. This system also produces one-electron oxidants that can readily oxidize Tyr to Tyr• (heme peroxidase compound I and II, •NO2) and •NO2 to generate the nitrated product.6,24

Tyrosine nitration can be achieved also by an •NO2− independent route that implies the addition of •NO to the Tyr• instead of •NO2, to yield 3-nitrosotyrosine. This intermediate can be further oxidized by two electrons to finally form NO2Tyr in two steps of one-electron oxidation that can be mediated by heme peroxidases/H2O2.27,28 This alternative mechanism may be of great relevance in vivo as it does not need •NO2, which has an extremely short biological half-life compared to •NO.29

The free radical reactions that lead to the production of NO2Tyr can also generate secondary products that are detected most of the time. Two of the most important of these products are 3,3′-dityrosine (DiTyr), which arises when two Tyr• recombine, and 3-hydroxytyrosine (DOPA), produced mainly as a product of •OH addition to Tyr and the subsequent loss of an electron of the adduct formed.5,24 Fig. 2 shows the free radical mechanisms that lead to tyrosine nitration and the formation of secondary products. The rate constants for several reactions involved in peroxynitrite biochemistry and tyrosine nitration are shown in Table 1.

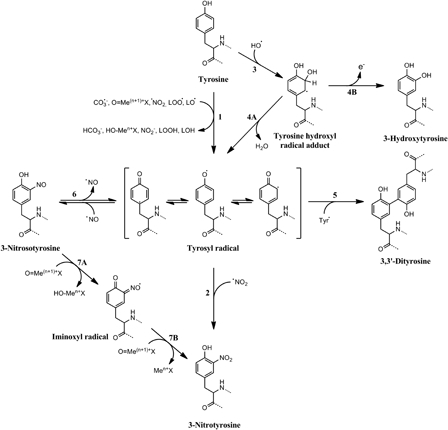

Figure 2.

Free radical mechanisms of tyrosine nitration and oxidation. Several one-electron oxidants can oxidize tyrosine to tyrosyl radical (1), which can then react with nitrogen dioxide to produce 3-nitrotyrosine (2). Hydroxyl radical can add into the phenolic ring of tyrosine (3) yielding a tyrosine hydroxyl radical adduct that can dehydrate to tyrosyl radical (4A) or loose an electron to produce the stable product 3-hydroxytyrosine (4B). Tyrosyl radicals, besides reacting with •NO2, can recombine between themselves to generate the oxidation product 3,3′-dityrosine (5). An alternative route to tyrosine nitration implies the reaction of tyrosyl radicals with nitric oxide (6) to yield 3-nitrosotyrosine. This intermediate can be then oxidized to 3-nitrotyrosine by two steps of one-electron oxidation mediated by oxo-metal complexes. The first oxidation produces an iminoxyl radical intermediate (7A) that is finally oxidized to 3-nitrotyrosine (7B). Modified from Ref. 5.

Table 1.

Rate constants of some relevant reactions involved in peroxynitrite biochemistry and tyrosine nitration

| Reaction | k (M−1 s−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| •NO + O2•− → ONOO− | 0.4–1.6 × 1010 | 30–32 |

| ONOO− + CO2 → ONOOCO2− | 5.8 × 104 | 16,33 |

| ONOOH + Prx5(-S−) → NO2− + Prx5(-SOH) | 7 × 107 | 34 |

| ONOOH + GS− → NO2− + GSOH | 1.4 × 103 | 35 |

| ONOOH + MPO(Fe3+) → •NO2 + MPO(Fe4+ = O) | 6.2 × 106 | 36 |

| ONOOH + Hb(Fe2+)O2 → Hb(Fe3+) + O2•− + NO3− + H+ | 1.04 × 104 | 37 |

| ONOO− + Mn3+TE-2-PyP → •NO2 + O = Mn4+TE-2-PyP | 3.4 × 107 | 38 |

| MPO(P•π+Fe4+ = O) + NO2− → MPO(PFe4+ = O) + •NO2 | 2.0 × 106 | 39 |

| •OH + NO2− → •NO2 + OH− | 6.0 × 109 | 40 |

| Tyr + CO3•− → Tyr• + HCO3− | 4.5 × 107 | 41 |

| Tyr + •OH → Tyr(OH)• | 1.2 × 1010 | 42 |

| Tyr + •NO2 → Tyr• + NO2− + H+ | 3.2 × 105 | 43 |

| Tyr + MPO(Fe4+ = O) → Tyr• + MPO(Fe3+) + OH− | 1.6 × 104 | 44 |

| Tyr + LOO• → Tyr• + LOOH | 4.8 × 103 | 25 |

| Tyr + LO• → Tyr• + LOH | 3.5 × 105 | 26 |

| Tyr• + •NO2 → NO2Tyr | 3.0 × 109 | 43 |

| Tyr• + Tyr• → DiTyr | 2.3 × 108 | 45 |

Experimental conditions used for rate constant determination (e.g. temperature, pH) can be found in each specific reference.

The homolysis of ONOOH to yield •OH and •NO2 in a first order process is described in the text and shown in Fig. 1. The reactions of peroxynitrite with peroxiredoxins, glutathione and oxyhemoglobin inhibit tyrosine nitration by reduction or isomerization of peroxynitrite.

Prx5, peroxiredoxin 5; GS−, glutathione; MPO, myeloperoxidase; HbO2, oxyhemoglobin; Mn3+TE-2-PyP, manganese (III) meso-tetrakis ((N-ethyl)pyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; MPO(P•π+Fe4+ = O), myeloperoxidase compound I.

Initially, it was proposed that tyrosine nitration could be achieved by a free radical-independent mechanism (an electrophilic aromatic nitration) promoted by the reaction between ONOO− and transition metal centers.5,7,8 In this mechanism, the transition metal center would promote the heterolytic cleavage of ONOO−, producing the nitronium cation (NO2+) that could then attack the aromatic ring of tyrosine as a two-electron acceptor, yielding a nitroarenium ion intermediate that then evolves to 3-nitrotyrosine and a proton. In this case, there is no net redox change in the metal center.5,7,8 However, this mechanism has not been confirmed in biological systems and the relevance of electrophilic aromatic nitration mediated by ONOO− and transition metal centers is undefined.

Transition metal center-mediated tyrosine nitration

Transition metals are not needed for peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration. In the absence of any direct targets, ONOO− finally decays by proton-catalyzed homolysis, producing both •OH and •NO2 that can oxidize and nitrate tyrosine. However, the yields of NO2Tyr formed under these conditions are usually low because no more than 30% of the ONOO− undergoes homolysis to •OH and •NO2, and also due to the extremely high reactivity of •OH that allows it to participate in many other reactions that compete with tyrosine nitration. Several low molecular weight transition metal complexes and some metalloproteins have been shown to enhance notably tyrosine nitration by ONOO− in vitro.8,19,46 The mechanism by which these metal complexes can promote ONOO−-dependent tyrosine nitration implies the direct reaction between ONOO− and the transition metal center, which acts as a Lewis acid, to form a Lewis adduct. This adduct would then undergo a homolytic rupture to yield •NO2 and the corresponding oxy radical of the Lewis acid, which finally rearranges to the respective oxo compound, via oxidation of the Lewis acid (Eq. 4; the charges of the species involved are not specified):5,47

| (4) |

As a result of this reaction, •NO2 and oxo-metal complexes (e.g. O = Fe4+X, O = Mn4+X) are generated; these two species are able to oxidize and nitrate tyrosine residues. So, in the presence of transition metal centers (low molecular weight complexes or metalloproteins) that react with ONOO− by the described reaction, ONOO−-dependent tyrosine nitration is mediated mainly by these two oxidants; NO2Tyr yields are increased in this transition metal-dependent nitration largely by two factors. In the absence of transition metal complexes, ONOO− will decay by proton-catalyzed homolysis, generating a maximum of 30% of the oxidants that mediate tyrosine nitration (•OH and •NO2). However, in the presence of transition metal complexes that react with ONOO− at moderate rates, most of the ONOO− will be decomposed by reaction with the metal complex and a small fraction will undergo homolysis. Depending on some factors (e.g. rate constant of the reaction between the metal and ONOO−, concentration of the metal complex), all of the ONOO− can decay through reaction with the metal complex, resulting in a generation of the secondary oxidants •NO2 and O = Me(n+1)+X with a 100% yield with respect to the initial ONOO− concentration. Thus, the production of ONOO−-derived secondary oxidants can reach much higher levels in the presence of some metal complexes and this will result in higher yields of tyrosine nitration. Besides this, nitration is enhanced also because of the higher selectivity of oxo-metal complexes to oxidize tyrosine residues than •OH; so, not only more oxidant is produced, but also a greater part of it may produce Tyr• (Fig. 3).

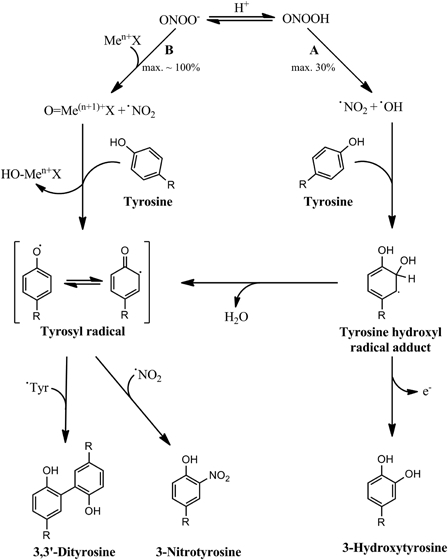

Figure 3.

Peroxynitrite-dependent tyrosine nitration mediated by transition metal centers. In the absence of any direct target, peroxynitrous acid decays by homolysis producing nitrogen dioxide and hydroxyl radicals with maximum yields of 30% (A). These two radicals mediate tyrosine nitration and oxidation by a hydroxyl radical-dependent pathway that produces 3-nitrotyrosine in relatively low yields, as well as 3,3′-dityrosine and 3-hydroxytyrosine. However, in the presence of certain transition metal centers that react fast with ONOO−, almost all of the peroxynitrite present can decompose by reacting with the metal complex (B), producing high levels of the oxidized oxo-metal complex and nitrogen dioxide. In this case, these two species mediate tyrosine nitration, which can occur now in higher yields. Also, high levels of 3,3′-dityrosine may be produced.

Peroxynitrite-independent tyrosine nitration depends largely on the presence of transition metals. It can occur by two main pathways described previously that use H2O2 and NO2−: the peroxidase-dependent oxidation of NO2− to •NO2 and the Fenton-dependent production of •NO2 from NO2−. In the first case, the two-electron oxidation of a heme peroxidase by H2O2 produces the heme peroxidase compound I that can act as a one-electron oxidant in the two key reactions: the oxidation of Tyr to Tyr• and the oxidation of NO2− to •NO2. The one-electron reduction product of compound I, compound II, can also oxidize by one-electron Tyr and NO2−. So, by any combination of these reactions, tyrosine nitration can be achieved, as both Tyr• and •NO2 are produced (Fig. 4).22,48,49 This transition metal-catalyzed nitration is mediated by Fe3+ and Mn3+ atoms coordinated by tetrapyrroles – iron and manganese porphyrins – both free and protein-bound, that can be oxidized by two electrons by H2O2.23,46,50

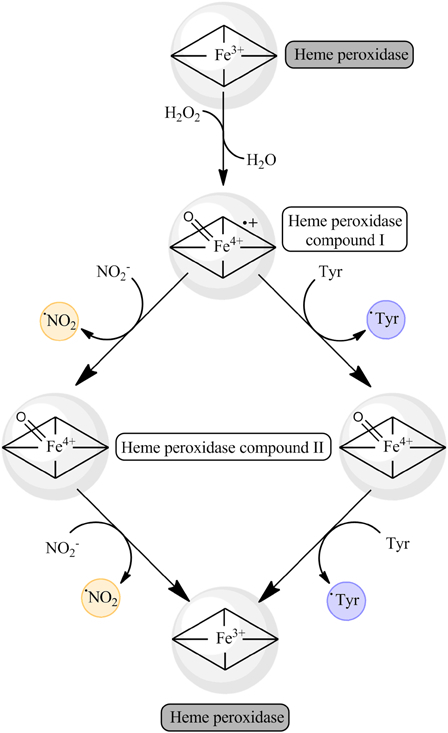

Figure 4.

Heme peroxidase-dependent tyrosine nitration in the presence of H2O2 and NO2−. Heme peroxidases can reduce H2O2 by two electrons to H2O, producing the oxidized compound I intermediate. This intermediate can oxidize by one-electron either tyrosine residues or nitrite, yielding tyrosyl radical or nitrogen dioxide, evolving to the compound II intermediate. Analogously, compound II can act also as a one-electron oxidant, able to oxidize tyrosine residues to tyrosyl radicals and NO2− to nitrogen dioxide. In this way, both tyrosyl radicals and nitrogen dioxide are produced and lead to 3-nitrotyrosine formation; also, 3,3′-dityrosine may be produced by the recombination of two tyrosyl radicals.

In the ferrous state (Fe2+), iron can also promote tyrosine nitration in the presence of H2O2 and NO2−, and in this case, the nature of the ligand group is not as relevant as for the mechanism mentioned before. This pathway to tyrosine nitration begins with the Fenton reaction, in which Fe2+ is oxidized by H2O2 to Fe3+, producing a hydroxyl anion and •OH (Eq. 5):

| (5) |

After its production, •OH can oxidize by one electron both Tyr to Tyr• and NO2− to •NO2 that can finally recombine to yield NO2Tyr (Eqs. 6–8). Clearly, the •NO2 produced is also able to oxidize Tyr to Tyr•:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Besides iron, copper can also induce tyrosine nitration by this mechanism: Cu+ atoms, coordinated by diverse ligands, participate as Fe2+ in the generation of •OH (Eq. 9) that in the presence of NO2− can lead to tyrosine nitration:23

| (9) |

Cupric ion-containing metal complexes (Cu2+X) also have been shown to mediate tyrosine nitration in the presence of H2O2 and NO2− by the same mechanism as Cu+ complexes; however, the Cu2+ atom needs to be reduced first to Cu+: this initial reduction can be promoted by hydroperoxide anions (HOO−) that arise from H2O2 dissociation (Eq. 10):23,51

| (10) |

Recently, a new mechanism was proposed to participate in copper-mediated tyrosine nitration. This novel mechanism is promoted by Cu2+ complexes in the presence of •NO2 and implies the reduction of the Cu2+ atom to Cu+ by •NO2, which oxidizes to NO2+ and may promote tyrosine nitration by electrophilic aromatic nitration.52 Further studies are needed to define the biological relevance of these reactions in copper-mediated tyrosine nitration.

Site-specificity in transition metal-catalyzed protein tyrosine nitration

Despite being a non-enzymatic amino acid modification, tyrosine nitration has shown to be a relatively selective process: not all proteins become nitrated and, among those proteins that undergo nitration, only one or two tyrosine residues are preferentially modified. The determinants of this selectivity are not fully established yet, but some relevant factors have been identified, like the protein structure, the nitration mechanism, and the environment where the protein is located.24,29 A particular case where the selectivity of tyrosine nitration seems more clear is in transition metal-containing proteins that have tyrosine residues close to the metal center. Two well-described examples of this are the MnSOD and the prostacyclin synthase, where a particular tyrosine residue is nitrated by ONOO−.53,54 In proteins that lack redox-active transition-metal centers, tyrosine nitration is achieved by one-electron oxidants that arise, for example, by ONOO− decomposition in solution, that will preferentially react with solvent-exposed tyrosines. However, for several transition metal-containing proteins, nitration can occur through the direct reaction between ONOO− and the metal center that, as was described previously, may generate oxidizing and nitrating species in situ (e.g. oxo-metal center and •NO2); these species may then promote the specific nitration of neighboring tyrosine residues. These metalloproteins may also catalyze their own site-specific nitration in the presence of H2O2 and NO2−, •NO2, or •NO: the direct reaction between the oxidized metal center (e.g. Fe3+ or Mn3+) and H2O2 would produce an oxo-metal compound that may oxidize nearby Tyr residues to Tyr•, which could then recombine with •NO2 (that may also be produced by the oxo-metal compound catalyzed oxidation of NO2−) to produce NO2Tyr. In the presence of •NO, the Tyr• produced could also lead to tyrosine nitration through the formation of 3-nitrosotyrosine (NOTyr), which could be further oxidized to NO2Tyr by the metalloprotein itself, in the presence of H2O2.29

The mechanisms of protein tyrosine nitration in controlled in vitro systems are well established nowadays; however, understanding properly how tyrosine nitration occurs in vivo is much more difficult, mainly because of the multiple targets and reactions that consume oxidizing and nitrating radicals by pathways different from tyrosine nitration, and also because of the presence of multiple biological reductants that could reduce tyrosyl radicals back to Tyr. When this is considered, site-specific nitration of metalloproteins becomes a mechanism of greater relevance, as it generates nitrating and oxidizing intermediates in a different environment, much closer to the tyrosine residue that gets nitrated and not accessible to reductants and other competitors that may abolish nitration.24

Biological examples of metal-catalyzed tyrosine nitration

There are many studies that support the close relationship between transition metal levels and tyrosine nitration, both by in vitro and in vivo approaches. Free iron (Fe2+ and Fe3+) and copper (Cu+ and Cu2+) ions can promote protein tyrosine nitration in the presence of H2O2 and NO2− through Fenton-type chemistry.23 This means that, under pathological conditions that involve high levels of these metal ions, there will be an increase in tyrosine nitration levels at least by this mechanism. Indeed, several studies have shown in some animal models of disease related with high levels of iron, how NO2Tyr levels are significantly increased.55–57

Under inflammatory conditions, the peroxidase-catalyzed mechanism of nitration is of greater relevance, due to the release of leukocyte peroxidases, like MPO and EPO, involved in the production of oxidants that participate in the immune response against invading pathogens.22,58,59 The reactive species generated by these heme peroxidases, besides acting as antimicrobial agents, can promote oxidative modifications of host biomolecules, like protein tyrosine nitration. Numerous studies have shown that the levels of protein-bound NO2Tyr are greatly enhanced in inflammatory sites under certain disease states (e.g. atherosclerotic plaque), where MPO also is found.60–63 In this case, not only the peroxidase/H2O2/NO2− system could be implied in nitration, but also ONOO−-dependent nitration promoted by MPO might contribute to the high levels of NO2Tyr detected.

Undoubtedly, one of the most relevant redox active transition metal complexes in biological systems is hemin (ferriprotoporphyrin IX). Under normal conditions, hemin is found as a prosthetic group in heme proteins, both in its reduced state (heme, Fe2+-protoporphyrin IX) and in its oxidized state (hemin), where its reactivity is more or less controlled. However, under diverse pathological conditions, high amounts of hemin are released from their respective proteins, resulting in high levels of free hemin able to participate in multiple oxidative reactions. This situation can occur mainly in hemolytic diseases (e.g., hemolytic anemia, sickle cell disease and hemorrhage), where the abnormal intravascular hemolysis results in the massive release of hemin from red blood cell hemoglobin into the vascular space.64–66

Free hemin is highly toxic; much of its toxicity is given by its redox properties and its capacity to produce highly reactive species that mediate oxidative damage, mainly through its reaction with H2O2. Although under certain conditions hemin can catalyze H2O2 decomposition to H2O and O2 (catalase-like activity), in the presence of many different substrates the hemin/H2O2 system acts as powerful one- and two-electron oxidant able to oxidize a great number of biomolecules.67,68 Protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation can be promoted by this system, among other modifications. Also, the reaction between hemin and lipid hydroperoxides produces secondary radical species that can lead to oxidative damage.69 Besides this, as was mentioned previously, free hemin catalyzes protein tyrosine nitration by H2O2/NO2− and can also promote ONOO−-dependent tyrosine nitration, enhancing greatly the levels of NO2Tyr.23,70 Indeed, it was observed that the levels of tyrosine nitrated proteins are much higher in aortas of animal models of hemolytic diseases with respect to normal ones, suggesting that the excess of hemin in the vasculature promotes tyrosine nitration, among other effects.71 Due to its high hydrophobicity, released hemin tends to accumulate in cell membranes, so its effects would be more pronounced on membrane proteins and lipids.

Transition metal-dependent increase in tyrosine nitration can also occur as an unintended reaction by certain metal-based drugs: this is the case of synthetic metalloporphyrins of iron and manganese (FeP and MnP), a group of compounds that can catalytically decompose ONOO− and that have been used in numerous in vivo and in vitro studies to attenuate peroxynitrite-dependent cytotoxicity. Their ability to act as ONOO− decomposers relies on their quite fast reaction with ONOO− (k ∼ 105–107 M−1s−1 for Mn3+/Fe3+P).12 Under normal cellular conditions, the compounds, administered as Mn3+P, readily evolve to the Mn2+ state; this reduction can be achieved in vivo with relative ease by low molecular weight reductants, such as glutathione or ascorbate, or also enzymatically by a number of flavoenzymes including the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Then, the Mn2+P can reduce ONOO− by two electrons, producing NO2− and O = Mn4+P, in a reaction that is almost as fast as the one for the Mn3+P and avoids •NO2 formation.12,13,72 However, under cellular oxidative stress conditions a larger fraction of both iron and manganese porphyrins can remain in the 3+ redox state and react with peroxynitrite in a one-electron reduction of ONOO−, yielding •NO2 and the oxo-metal 4+ state of the porphyrin (O = Fe/Mn4+P), both strong oxidants. Although in a large number of studies in in vivo models these compounds have shown to protect against peroxynitrite dependent cytotoxicity,12 in vitro approaches showed early that Fe3+ and Mn3+ porphyrins can enhance peroxynitrite-mediated oxidations, like DNA strand breaks and tyrosine nitration.46,73,74 It seems reasonable that these compounds starting in the 3+ state could promote tyrosine nitration by ONOO− as both O = Fe/Mn4+P and •NO2 can oxidize and nitrate tyrosine residues. So, the effectiveness of Mn and Fe-porphyrins to neutralize deleterious actions of peroxynitrite depends on cell/tissue redox state and its use in subjects with critically low levels of intracellular reductants may result in more oxidative damage than protection.

Site-specific nitration of proteins directed by transition metal centers has been observed in diverse metalloproteins by in vitro approaches. For example, human MnSOD is nitrated by ONOO− specifically at tyrosine 34, which is located close to the Mn3+ atom.75,76 MnSOD nitration is mediated by the direct reaction between the metal center and ONOO− that yields Mn4+ = O and •NO2.53 Like MnSOD, prostaglandin H2 synthase (PGHS) is also site-specifically nitrated by ONOO− at residue 385, in a process that depends on the heme group of the enzyme.77 Another heme protein, prostacyclin synthase, undergoes site-specific nitration by ONOO− at tyrosine 430, a residue that lies near the heme group.54 Interestingly, it was seen that PGHS can also be specifically nitrated at tyrosine 385 by a peroxynitrite-independent mechanism. During the enzyme turnover, a tyrosyl radical at Tyr 385 is generated; the trapping of this Tyr• by •NO can lead to NO2Tyr through the oxidation of the nitrosotyrosine in the presence of more substrate.27,78

Thus, site-specific tyrosine nitration of metalloproteins might occur in vivo by diverse mechanisms and seems to be a quite relevant process in biological tyrosine nitration: metal-catalyzed protein tyrosine nitration can be achieved at considerable yields in vivo even in the presence of multiple targets that readily consume reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (Table 1).

Disclaimer statements

Contributors N.C., S.B. and R.R. elaborated together the outline of the review, defined the artwork and the key bibliography. N.C. generated the first written version and was responsible of the artwork. S.B. and R.R. provided continuous advice, additional text and bibliography throughout the process. All authors worked on the different draft versions of the manuscript until reaching final form.

Funding This work was supported by grants of Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (Fondo Clemente Estable, FCE_6605) to S.B. and Universidad de la República, Alexander Von Humboldt Foundation and National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI095173) to R.R. Further support was provided by the companies RIDALINE, ALDENOR and ASM through the Fundación Manuel Pérez, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de la República, Uruguay.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval None.

Acknowledgements

N.C. is partially supported by a fellowship from Universidad de la República.

References

- 1.Rines AK, Ardehali H. Transition metals and mitochondrial metabolism in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2013;55:50–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean KM, Qin Y, Palmer AE. Visualizing metal ions in cells: an overview of analytical techniques, approaches, and probes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1823(9):1406–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aust SD, Morehouse LA, Thomas CE. Role of metals in oxygen radical reactions. J Free Radic Biol Med 1985;1(1):3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewer GJ. Risks of copper and iron toxicity during aging in humans. Chem Res Toxicol 2010;23(2):319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radi R. Nitric oxide, oxidants, and protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101(12):4003–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza JM, Peluffo G, Radi R. Protein tyrosine nitration – functional alteration or just a biomarker? Free Radic Biol Med 2008;45(4):357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Chen J, Tsai M, Martin JC, Smith CD,. et al. Peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration catalyzed by superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys 1992;298(2):431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckman JS, Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, van der Woerd M, Smith C, Chen J,. et al. Kinetics of superoxide dismutase- and iron-catalyzed nitration of phenolics by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys 1992;298(2):438–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ignarro LJ, Byrns RE, Buga GM, Wood KS, Chaudhuri G. Pharmacological evidence that endothelium-derived relaxing factor is nitric oxide: use of pyrogallol and superoxide dismutase to study endothelium-dependent and nitric oxide-elicited vascular smooth muscle relaxation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1988;244(1):181–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles RG, Palacios M, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Formation of nitric oxide from L-arginine in the central nervous system: a transduction mechanism for stimulation of the soluble guanylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989;86(13):5159–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marletta MA, Yoon PS, Iyengar R, Leaf CD, Wishnok JS. Macrophage oxidation of L-arginine to nitrite and nitrate: nitric oxide is an intermediate. Biochemistry 1988;27(24):8706–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szabó C, Ischiropoulos H, Radi R. Peroxynitrite: biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007;6(8):662–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. Chemical biology of peroxynitrite: kinetics, diffusion, and radicals. ACS Chem Biol 2009;4(3):161–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahoney LR. Evidence for the formation of hydroxyl radicals in the isomerization of pernitrous acid to nitric acid in aqueous solution. J Am Chem Soc 1970;92:5262–3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990;87(4):1620–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denicola A, Freeman BA, Trujillo M, Radi R. Peroxynitrite reaction with carbon dioxide/bicarbonate: kinetics and influence on peroxynitrite-mediated oxidations. Arch Biochem Biophys 1996;333(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radi R. Peroxynitrite, a stealthy biological oxidant. J Biol Chem 2013;288(37):26464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos CX, Bonini MG, Augusto O. Role of the carbonate radical anion in tyrosine nitration and hydroxylation by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys 2000;377(1):146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramezanian MS, Padmaja S, Koppenol WH. Nitration and hydroxylation of phenolic compounds by peroxynitrite. Chem Res Toxicol 1996;9(1):232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM, Freeman BA. Peroxynitrite oxidation of sulfhydryls. J Biol Chem 1991;266(7):4244–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Augusto O, Bonini MG, Amanso AM, Linares E, Santos CX, De Menezes SL. Nitrogen dioxide and carbonate radical anion: two emerging radicals in biology. Free Radic Biol Med 2002;32(9):841–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Vliet A, Eiserich JP, Halliwell B, Cross CE. Formation of reactive nitrogen species during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of nitrite. J Biol Chem 1997;272(12):7617–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas DD, Espey MG, Vitek MP, Miranda KM, Wink DA. Protein nitration is mediated by heme and free metals through Fenton-type chemistry: an alternative to the NO/O2− reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99(20):12691–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartesaghi S, Ferrer-Sueta G, Peluffo G, Valez V, Zhang H, Kalyanaraman B,. et al. Protein tyrosine nitration in hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments. Amino Acids 2007;32(4):501–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartesaghi S, Wenzel J, Trujillo M, López M, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B,. et al. Lipid peroxyl radicals mediate tyrosine dimerization and nitration in membranes. Chem Res Toxicol 2010;23(4):821–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folkes LK, Bartesaghi S, Trujillo M, Radi R, Wardman P. Kinetics of oxidation of tyrosine by a model alkoxyl radical. Free Radic Res 2012;46(9):1150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunther MR, Hsi LC, Curtis JF, Gierse JK, Marnett LJ, Eling TE,. et al. Nitric oxide trapping of the tyrosyl radical of prostaglandin H synthase-2 leads to tyrosine iminoxyl radical and nitrotyrosine formation. J Biol Chem 1997;272(27):17086–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sturgeon BE, Glover RE, Chen YR, Burka LT, Mason RP. Tyrosine iminoxyl radical formation from tyrosyl radical/nitric oxide and nitrosotyrosine. J Biol Chem 2001;276(49):45516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radi R. Protein tyrosine nitration: biochemical mechanisms and structural basis of functional effects. Acc Chem Res 2013;46(2):550–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein S, Czapski G. The reaction of NO• with O2•− and HO2•: a pulse radiolysis study. Free Radic Biol Med 1995;19(4):505–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huie RE, Padmaja S. The reaction of NO with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun 1993;18(4):195–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kissner R, Nauser T, Bugnon P, Lye PG, Koppenol WH. Formation and properties of peroxynitrite as studied by laser flash photolysis, high-pressure stopped-flow technique, and pulse radiolysis. Chem Res Toxicol 1997;10(11):1285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lymar SV, Hurst JK. Rapid reaction between peroxynitrite ion and carbon dioxide: implications for biological activity. J Am Chem Soc 1995;117(20):8867–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubuisson M, Vander Stricht D, Clippe A, Etienne F, Nauser T, Kissner R,. et al. Human peroxiredoxin 5 is a peroxynitrite reductase. FEBS Lett 2004;571(1-3):161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koppenol WH, Moreno JJ, Pryor WA, Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite, a cloaked oxidant formed by nitric oxide and superoxide. Chem Res Toxicol 1992;5(6):834–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Floris R, Piersma SR, Yang G, Jones P, Wever R. Interaction of myeloperoxidase with peroxynitrite. A comparison with lactoperoxidase, horseradish peroxidase and catalase. Eur J Biochem 1993;215(3):767–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Denicola A, Souza JM, Radi R. Diffusion of peroxynitrite across erythrocyte membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95(7):3566–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrer-Sueta G, Vitturi D, Batinic-Haberle I, Fridovich I, Goldstein S, Czapski G,. et al. Reactions of manganese porphyrins with peroxynitrite and carbonate radical anion. J Biol Chem 2003;278(30):27432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burner U, Furtmuller PG, Kettle AJ, Koppenol WH, Obinger C. Mechanism of reaction of myeloperoxidase with nitrite. J Biol Chem 2000;275(27):20597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagager T, Sehested K. Formation and decay of peroxynitrous acid: a pulse radiolysis study. J Phys Chem 1993;97:6664–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S, Hoffman MZ. Rate constants for the reaction of the carbonate radical with compounds of biochemical interest in neutral aqueous solution. Radiat Res 2014;56(1):40–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solar S, Solar W, Getoff N. Reactivity of OH with tyrosine in aqueous solution studied by pulse radiolysis. J Phys Chem 1984;88:2091–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prütz WA, Mönig H, Butler J, Land EJ. Reactions of nitrogen dioxide in aqueous model systems: oxidation of tyrosine units in peptides and proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys 1985;243(1):125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marquez LA, Dunford HB. Kinetics of oxidation of tyrosine and dityrosine by myeloperoxidase compounds I and II. Implications for lipoprotein peroxidation studies. J Biol Chem 1995;270(51):30434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin F, Leitich J, von Sonntag C. The superoxide radical reacts with tyrosine-derived phenoxyl radicals by addition rather than by electron transfer. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2 1993;(9):1583. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrer-Sueta G, Ruiz-Ramírez L, Radi R. Ternary copper complexes and manganese (III) tetrakis(4-benzoic acid) porphyrin catalyze peroxynitrite-dependent nitration of aromatics. Chem Res Toxicol 1997;10(12):1338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferrer-Sueta G, Quijano C, Alvarez B, Radi R. Reactions of manganese porphyrins and manganese-superoxide dismutase with peroxynitrite. Methods Enzymol 2002;349:23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCormick ML, Gaut JP, Lin T, Britigan BE, Buettner GR, Heinecke JW. Electron paramagnetic resonance detection of free tyrosyl radical generated by myeloperoxidase, lactoperoxidase, and horseradish peroxidase. J Biol Chem 1998;273(48):32030–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacob JS, Cistola DP, Hsu FF, Muzaffar S, Mueller DM, Hazen SL,. et al. Human phagocytes employ the myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide system to synthesize dityrosine, trityrosine, pulcherosine, and isodityrosine by a tyrosyl radical-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 1996;271(33):19950–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao P, Song Y, Li H, Gao Z. Efficiency of methemoglobin, hemin and ferric citrate in catalyzing protein tyrosine nitration, protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation in a bovine serum albumin-liposome system: influence of pH. J Inorg Biochem 2009;103(5):783–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiao L, Lu Y, Liu B, Girault HH. Copper-catalyzed tyrosine nitration. J Am Chem Soc 2011;133(49):19823–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar V, Kalita A, Mondal B. Phenol ring nitration induced by the unprecedented reduction of the Cu(II) centre by nitrogen dioxide. Dalton Trans 2013;42(46):16264–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quijano C, Hernandez-Saavedra D, Castro L, McCord JM, Freeman BA, Radi R. Reaction of peroxynitrite with Mn-superoxide dismutase. Role of the metal center in decomposition kinetics and nitration. J Biol Chem 2001;276(15):11631–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidt P, Youhnovski N, Daiber A, Balan A, Arsic M, Bachschmid M,. et al. Specific nitration at tyrosine 430 revealed by high resolution mass spectrometry as basis for redox regulation of bovine prostacyclin synthase. J Biol Chem 2003;278(15):12813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li X, Li H, Lu N, Feng Y, Huang Y, Gao Z. Iron increases liver injury through oxidative/nitrative stress in diabetic rats: involvement of nitrotyrosination of glucokinase. Biochimie 2012;94(12):2620–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y, Huang Y, Deng X, Xu Y, Gao Z, Li H. Iron overload-induced rat liver injury: involvement of protein tyrosine nitration and the effect of baicalin. Eur J Pharmacol 2012;680(1-3):95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonald CJ, Ostini L, Wallace DF, John AN, Watters DJ, Subramaniam VN,. et al. Iron loading and oxidative stress in the Atm−/− mouse liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011;300(31):554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brennan ML, Wu W, Fu X, Shen Z, Song W, Frost H,. et al. A tale of two controversies: defining both the role of peroxidases in nitrotyrosine formation in vivo using eosinophil peroxidase and myeloperoxidase-deficient mice, and the nature of peroxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species. J Biol Chem 2002;277(20):17415–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu W, Chen Y, Hazen SL. Eosinophil peroxidase nitrates protein tyrosyl residues. Implications for oxidative damage by nitrating intermediates in eosinophilic inflammatory disorders. J Biol Chem 1999;274(36):25933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baldus S, Eiserich JP, Brennan M-L, Jackson RM, Alexander CB, Freeman BA. Spatial mapping of pulmonary and vascular nitrotyrosine reveals the pivotal role of myeloperoxidase as a catalyst for tyrosine nitration in inflammatory diseases. Free Radic Biol Med 2002;33(7):1010–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vivekanandan-Giri A, Slocum JL, Byun J, Tang C, Sands RL, Gillespie BW,. et al. High density lipoprotein is targeted for oxidation by myeloperoxidase in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(10):1725–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He C, Choi HC, Xie Z. Enhanced tyrosine nitration of prostacyclin synthase is associated with increased inflammation in atherosclerotic carotid arteries from type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Pathol 2010;176(5):2542–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hataishi R, Kobayashi H, Takahashi Y, Hirano S, Zapol WM, Jones RC. Myeloperoxidase-associated tyrosine nitration after intratracheal administration of lipopolysaccharide in rats. Anesthesiology 2002;97(4):887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar S, Bandyopadhyay U. Free heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol Lett 2005;157(3):175–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson SR, Dang TN, Dringen R, Bishop GM. Hemin toxicity: a preventable source of brain damage following hemorrhagic stroke. Redox Rep 2009;14(6):228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vinchi F, Tolosano E. Therapeutic approaches to limit hemolysis-driven endothelial dysfunction: scavenging free heme to preserve vasculature homeostasis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013:396527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kremer ML. The reaction of hemin with H2O2. Eur J Biochem 1989;185(3):651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Portsmouth D, Beal EA. The peroxidase activity of deuterohemin. Eur J Biochem 1971;19:479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kalyanaraman B, Mottley C, Mason RP. A direct electron spin resonance and spin-trapping investigation of peroxyl free radical formation by hematin/hydroperoxide systems. J Biol Chem 1983;258(6):3855–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartesaghi S, Valez V, Trujillo M, Peluffo G, Romero N, Zhang H,. et al. Mechanistic studies of peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration in membranes using the hydrophobic probe N-t-BOC-L-tyrosine tert-butyl ester. Biochemistry 2006;45(22):6813–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vinchi F, De Franceschi L, Ghigo A, Townes T, Cimino J, Silengo L,. et al. Hemopexin therapy improves cardiovascular function by preventing heme-induced endothelial toxicity in mouse models of hemolytic diseases. Circulation 2013;127(12):1317–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trujillo M, Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. Peroxynitrite detoxification and its biologic implications. Antioxid Redox Signal 2008;10(9):1607–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crow JP. Manganese and iron porphyrins catalyze peroxynitrite decomposition and simultaneously increase nitration and oxidant yield: implications for their use as peroxynitrite scavengers in vivo. Arch Biochem Biophys 1999;371(1):41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Groves JT, Marla SS. Peroxynitrite-induced DNA strand scission mediated by a manganese porphyrin. J Am Chem Soc 1995;117:9578–9. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamakura F, Taka H, Fujimura T, Murayama K. Inactivation of human manganese-superoxide dismutase by peroxynitrite is caused by exclusive nitration of tyrosine 34 to 3-nitrotyrosine. J Biol Chem 1998;273(5):14085–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moreno DM, Martí MA, De Biase PM, Estrin DA, Demicheli V, Radi R,. et al. Exploring the molecular basis of human manganese superoxide dismutase inactivation mediated by tyrosine 34 nitration. Arch Biochem Biophys 2011;507(2):304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deeb RS, Hao G, Gross SS, Lainé M, Qiu JH, Resnick B,. et al. Heme catalyzes tyrosine 385 nitration and inactivation of prostaglandin H2 synthase-1 by peroxynitrite. J Lipid Res 2006;47(5):898–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goodwin DC, Gunther MR, Hsi LC, Crews BC, Eling TE, Mason RP,. et al. Nitric oxide trapping of tyrosyl radicals generated during prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase turnover: detection of the radical derivative of tyrosine 385. J Biol Chem 1998;273(10):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]