Abstract

Background

Preterm infants who are fed breast milk in comparison to infant formula have decreased morbidity such as necrotizing enterocolitis. Multi‐nutrient fortifiers used to increase the nutritional content of the breast milk are commonly derived from bovine milk. Human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier is now available, but it is not clear if it improves outcomes in preterm infants fed with breast milk.

Objectives

To determine whether the fortification of breast milk feeds with human milk‐derived fortifier in preterm infants reduces mortality, morbidity, and promotes growth and development compared to bovine milk‐derived fortifier.

Search methods

We searched the following databases for relevant trials in September 2018.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, Issue 9), electronic journal reference databases including MEDLINE (1980 to 20 September 2018), PREMEDLINE, Embase (1974 to 20 September 2018), CINAHL (1982 to 20 September 2018), biological abstracts in the database BIOSIS and conference abstracts from 'Proceedings First' (from 1992 to 2011). We also included the following clinical trials registries for ongoing or recently completed trials: ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.whoint/ictrp/search/en/) and the ISRCTN Registry (www.isrctn.com/), and abstracts of conferences: proceedings of Pediatric Academic Societies (American Pediatric Society, Society for Pediatric Research and European Society for Paediatric Research) from 1990 in the 'Pediatric Research' journal and 'Abstracts online' (2000 to 2017).

Selection criteria

We included randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials that compared preterm infants fed breast milk fortified with human milk‐derived fortifier versus those fed with breast milk fortified with bovine milk‐derived fortifier.

Data collection and analysis

The data were collected using the standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal. Two authors evaluated trial quality of the studies and extracted data. We reported dichotomous data using risk ratios (RRs), risk differences (RDs), number needed to treat (NNT) where applicable, and continuous data using mean differences (MDs). We assessed the quality of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

One randomized trial with 127 infants met the eligibility criteria and had low risk of bias. Human milk‐based fortifier did not decrease the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in exclusively breast milk‐fed preterm infants (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.2 to 4.54; 1 study, 125 infants, low certainty of evidence). Human milk‐derived fortifiers did not improve growth, decrease feeding intolerance, late‐onset sepsis, or death.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence evaluating human milk‐derived fortifier with bovine milk‐derived fortifier in exclusively breast milk‐fed preterm infants. Low‐certainty evidence from one study suggests that in exclusively breast milk‐fed preterm infants human milk‐derived fortifiers in comparison with bovine milk‐derived fortifier may not change the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, mortality, feeding intolerance, infection, or improve growth. Well‐designed randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate short‐term and long‐term outcomes.

Plain language summary

Human milk‐derived fortifier in preterm infants fed with all breast milk

Review question: In preterm infants fed only breast milk, does the use of extra nutrients (to provide extra protein and energy) made from human milk compared to nutrients from cow's milk decrease the chances of illnesses, death or improve growth?

Background: Preterm infants fed with breast milk need extra energy and protein to support their growth. Hence, nutrients (multi‐nutrient fortifiers) are added to the breast milk. It is not clear if nutrients made from human milk, when compared to nutrients made from cow's milk, decrease the risk of death and other illnesses, and improve growth in preterm infants who are fed only with breast milk.

Study characteristics: We found one well‐performed study that enrolled 127 infants addressing this question. Evidence is up to date as of 20 September 2018.

Key results: The use of nutrients made from human milk, when compared with nutrients made from cow's milk, did not reduce the risk of intestinal disease (necrotizing enterocolitis), feeding problems, death, infections, or improve growth in preterm infants fed with breast milk.

Conclusions: Nutrients made from human milk (multi‐nutrient fortifier), when compared with nutrients made from cow's milk, may not change the occurrence of illnesses or improve the growth in preterm infants fed only with breast milk. This evidence is insufficient to conclude whether nutrient made from human milk (multi‐nutrient fortifier) when provided to preterm infants fed only with breast milk is beneficial or not. More studies are needed to address this important question.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier compared with bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier for short‐term outcomes in preterm neonates | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Preterm neonates (< 37 0/7 weeks' gestation) fed exclusively with breast milk Settings: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit/healthcare setting Intervention: Human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier Comparison: Bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier | Risk with human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier | |||||

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | Study population | RR 0.95, (0.20 to 4.54) | 125 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | ||

| 49.2 per 1000 | 46.9 per 1000 | RD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.07 | ||||

| Death | Study population | (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.06) | 121 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | ||

| 65.6 per 1000 | 46.9 per 1000 | (RD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.06) | ||||

| Weight (change during intervention) (mean ± SD) |

1303 ± 610g | 1124 ± 534g | (MD ‐179.00, 95% CI ‐386.38 to 28.38) | 118 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

| Length (change during intervention) (mean ± SD) |

8.1 ± 4 cm | 7.3 ± 4 cm | (MD ‐0.80, 95% CI ‐2.25 to 0.65) | 118 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

| Head circumference (change during intervention) (mean ± SD) |

6.8 ± 2.5 cm | 6.2 ± 2.6 | (MD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.52 to 0.32) | 118 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

| Feeding interruption requiring parenteral nutrition | Study population | (RR 2.86, 95% CI 0.31 to 26.75) | 125 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | ||

| 16.4 per 1000 | 46.9 per 1000 | (RD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.06) | ||||

| Late‐onset sepsis | Study population | (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.21) | 125 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | ||

| 229.5 per 1000 | 125 per 1000 | (RD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.03) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; RD: Risk Difference; MD: Mean Difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aImprecision as suggested by wide 95% confidence intervals

bInclusion of a single eligible study

Background

Description of the condition

Prematurity is the most common cause of death in children under five years of age worldwide (Blencowe 2012; WHO 2017). Preterm infants are deprived of the transplacental (across the placenta) maternal‐fetal transfer of nutrients that occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy. More than 90% of energy deposited near term, which involves active amino acid transport, accretion of minerals, glycogen and fat, occurs in the last trimester (Lager 2012). The calorie and nutrient deficit in preterm infants is further compounded by the higher nutritional demands imposed by both baseline and catch‐up growth. Hence, it is imperative to fulfil the additional caloric and nutritional needs of preterm infants for optimal growth (Agostini 2010; Embleton 2007). Improved postnatal nutritional status decreases mortality and neuromorbidity in preterm infants (Hsiao 2014; McNelis 2017).

Mother’s own milk is the preferred source of nutrition for most preterm infants and inadequate supply of mother’s own milk poses challenges for optimal nutrition. In such instances, donor milk is frequently utilized to offset the shortage in supply. Since mother’s own milk or donor breast milk alone cannot meet the increased energy (110 to 135 kcal/kg/d) and protein (3.5 to 4.5 g/kg/d) demands of preterm infants, supplementation with multi‐nutrient fortifiers is required (Agostini 2010). Feeding unfortified human milk to a preterm infant often fails to meet the protein and minerals requirement, which results in low bone mineral content and inadequate growth (Gathwala 2007; Mukhopadhyay 2007). Adequate nutrition becomes the foundation of care in a preterm infant and failure to supplement breast milk with fortifiers can often lead to growth failure. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends fortification of human milk as the standard of care in preterm infants, particularly in infants who are less than 1500 g at birth (AAP 2012).

Multi‐nutrient fortifiers provide additional protein, energy (in the form of fat and carbohydrates), vitamins, iron and minerals and are available in both powder and liquid forms. Multi‐nutrient fortifiers are supplemented to augment the nutritional content of the mother’s own milk or the donor breast milk, and thereby to improve the growth of the preterm infants (Brown 2016; Dutta 2015; Mukhopadhyay 2007; Polberger 1989). The age of the preterm infant and the volume of feeds at which the multi‐nutrient fortifiers are introduced are variable. The multi‐nutrient fortifiers are usually introduced after feed tolerance has been demonstrated at volumes greater than trophic (small amount mainly given to keep the gut active and without much nutritional value) feeds. The multi‐nutrient fortifiers are rarely continued beyond discharge from the hospital because of concerns for toxicity of certain nutrients if the recommended intake is exceeded (Tudehope 2013). In such situations, upon discharge from the hospital, breast milk is often supplemented with transitional discharge formula instead of multi‐nutrient fortifiers.

The increased mortality and morbidity observed in preterm infants are secondary to complications such as hyaline membrane disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, retinopathy of prematurity, intraventricular hemorrhage, and sepsis (diseases seen in premature children involving lung, intestines, developing eyes, bleeding inside the brain and infection in the blood respectively)(Horbar 2012). Necrotizing enterocolitis is a devastating morbidity in preterm infants and affects nearly 12% of very low birth weight infants, of which nearly 30% die secondary to its complications (Gephart 2012; Horbar 2012). The etiology of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants is multifactorial and risk factors such as formula feeding, decreased or absent breast milk feeding, microbial dysbiosis (growth of harmful bacteria), infection and hypoxia, have been implicated. Breast milk (either mother’s own or donor breast milk) has been shown to be protective, while formula milk increases the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants (Quigley 2018). It is also observed that the protective effect of breast milk against necrotizing enterocolitis is dose‐dependent (Sisk 2007; Sisk 2017). The absence of specific protective factors inherent to breast milk, and the presence of potentially harmful factors in formula milk have been blamed for the increased incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis with the use of formula milk (Lönnerdal 2017). Avoidance of all bovine milk products, from which most of the multi‐nutrient fortifier and formula milk are derived, is proposed as an approach to decrease the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis. One strategy to avoid bovine products is by encouraging maternal lactation, providing support to the lactating mothers to sustain the supply of breast milk, and provision of donor breast milk when mother’s own milk is unavailable (Skouteris 2017). The other strategy is to utilize lacto‐engineering techniques to synthesize multi‐nutrient fortifiers from human milk instead of bovine milk.

Description of the intervention

Traditionally, bovine milk has been the source for the multi‐nutrient fortifiers (Mimouni 2017). Recently, using lacto‐engineering techniques, multi‐nutrient fortifiers have been derived from human milk instead of bovine milk (Sullivan 2010). Since exposure to commercial formula feeds is thought to increase morbidities including necrotizing enterocolitis, human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier has been used in place of bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier to minimize exposure to bovine products. The human milk‐derived fortifier is introduced once tolerance of feeds at a volume greater than trophic feeds is demonstrated. The supplementation with human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifiers is usually continued until around 34 weeks, when transition to a post‐discharge transitional formula or a term formula is made. This marks the strategy wherein human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifiers are used to supplement mother’s own milk or donor human milk in order to avoid all bovine milk‐derived products prior to 34 weeks with an intent to decrease the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis.

How the intervention might work

Human breast milk contains a myriad of protective and trophic components, which offer a multitude of benefits including effects on digestion, immunity and development of a healthy gut microbiome (the bacterial community in the gut). Breast milk has a high content of lactoferrin, α‐lactalbumin and many other substances with immunomodulatory (ability to alter immunity) properties. The high content of lysozyme and secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) confers transfer of maternal immunity and reinforces the antibacterial and antiviral properties of the breast milk. Factors such as α1‐antitrypsin, β‐casein in the breast milk aid in the process of nutrient digestion and absorption (Lönnerdal 2017). The multi‐nutrient fortifiers derived from human breast milk are thought to extend these same benefits when used to fortify breast milk. Human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifiers are also thought to improve feed tolerance and facilitate progression to full feeds, thereby decreasing the duration of parenteral (other than enteral, often via a vein) nutrition and the need for venous (through the vein) access. Hence, the use of human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifiers and avoidance of bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifiers is proposed as a strategy to decrease morbidity and to improve growth in preterm infants.

Why it is important to do this review

Rates of preterm births are rising (15 million preterm births worldwide in 2010) and survival rates in extremely preterm infants are improving (Blencowe 2012; NCHS 2018). The need for interventions to prevent or decrease neonatal morbidities, including necrotizing enterocolitis, is greater than ever. The use of multi‐nutrient fortifiers derived from human milk is one such encouraging intervention. It is crucial to investigate whether the use of human milk‐derived fortifier has beneficial effects on preterm mortality and morbidity even when the rate of breast milk feeding (mother’s own milk and donor milk) is high. Currently available human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier is expensive and has limited availability. Infants who were fed donor breast milk are known to have decreased in‐hospital growth compared to formula‐fed infants (Quigley 2018). Such observations raise concerns for inadequacy of growth in infants who receive a human milk‐based multi‐nutrient fortifier‐based diet. The evidence for the safety and efficacy for the use of human milk‐derived fortifier has not been assessed in a systematic review.

Objectives

To determine whether the fortification of breast milk feeds with human milk‐derived fortifier in preterm infants reduces mortality and morbidity and promotes growth and development compared to bovine milk‐derived fortifier.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs and cluster‐RCTs were considered. We planned to exclude cross‐over trials.

Types of participants

Preterm infants (less than 37 weeks' gestation) receiving enteral feeds exclusively with breast milk, either mother’s own milk or donor breast milk, or both concurrently or sequentially.

Types of interventions

Breast milk (mother’s own or donor or both) fortified exclusively with human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier versus breast milk (mother’s own or donor or both) fortified exclusively with bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier or formula.

We considered any dosage for a minimum duration of two weeks, initiated at any time during enteral feeding, and with any regimen of fortification or feeding. The target levels of volume of milk intake remained the same between the groups. Infants in both the groups had received the same standard of care except for the type of multi‐nutrient fortification.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Necrotizing enterocolitis as defined by stage 2 or stage 3 of modified Bell’s Stage (Walsh 1986), or all‐cause mortality prior to hospital discharge and first year of life.

Secondary outcomes

-

Adequacy of growth based on:

time taken to regain birth weight (days);

rates of increase in the weight (g/kg/day), length (cm/week) and head circumference (cm/week) up to six months' post‐term;

long‐term growth: rates of increase in the weight (g/kg/day), length (cm/week) and head circumference (cm/week) beyond six months' post‐term;

weight (g or z scores), head circumference (cm or z scores), and length (cm or z scores) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age and at discharge.

Neurodevelopment: severe neurodevelopmental disability defined after 12 months post‐term by one or more of the below: non‐ambulant cerebral palsy, neurodevelopmental delay (Bayley Scales of Infant Development) (Bayley 1993; Bayley 2005), auditory impairment (any impairment requiring or unimproved by amplification) and visual impairment (visual acuity < 6/60).

Feeding intolerance as defined by the number of days when feeds were stopped or reduced and parenteral nutrition was either commenced or increased during hospital stay secondary to the inability to digest enteral feeds presented as gastric residual volume of more than 50%, abdominal distension or emesis or both, or as defined by study authors (Moore 2011).

Duration of parenteral nutrition (in total number of days) during hospital stay.

Time taken to achieve full enteral feeds (in days) during the hospital stay defined as the first day when 100% of total caloric requirement or ≥ 140 mL/kg/day of feeds was administered enterally and thereafter sustained for more than 48 hours or as defined by the study authors (Maas 2018).

Time taken to achieve full intake of enteral feeds by oral route.

Length of hospital stay (in days).

Neonatal sepsis as defined by culture‐proven infection of bacteria or fungus from blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine or other body fluids, which are usually sterile (number of events of sepsis/1000 treatment days).

Measures of bone mineralization such as serum alkaline phosphatase level (≥ 2 X upper limit of normal or > 800 U/L, two values measured one week apart) (Abrams 2013; Mitchell 2009), or bone mineral content assessed by dual energy x‐ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and clinical or radiological evidence of rickets on short‐term follow‐up (36 weeks' postmenstrual age or discharge, whichever is earlier) and long‐term follow‐up (12 to 18 months).

Intestinal failure‐associated liver disease (serum conjugated bilirubin ≥ 2 mg/dL for ≥ 2 consecutive weeks during the administration of parenteral nutrition, not associated with other known causes of cholestasis) (Nehra 2014).

Duration of mechanical ventilation (days).

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (including at 28 days of life and 36 weeks' postmenstrual age) (Jobe 2001).

Retinopathy of prematurity (any stage or any stage ≥ 3 or any stage receiving treatment) (ICROP 2005).

Healthcare costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

We used the criteria and standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal (see the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy for specialized register).

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for relevant trials in September 2018.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, Issue 9).

Electronic journal reference databases: MEDLINE (1980 to 20 September 2018) and PREMEDLINE, Embase (1974 to 20 September 2018) and CINAHL (1982 to 20 September 2018).

Biological abstracts in the database BIOSIS and conference abstracts from 'Proceedings First' (from 1992 to 2011).

We used the search terms outlined in Appendix 1. We did not apply language restrictions.

We searched the following clinical trials registries for ongoing or recently completed trials: ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.whoint/ictrp/search/en/) and the ISRCTN Registry (www.isrctn.com/).

Searching other resources

Abstracts of conferences: proceedings of Pediatric Academic Societies (American Pediatric Society, Society for Pediatric Research and European Society for Paediatric Research) from 1990 in the 'Pediatric Research' journal and 'Abstracts online' (2000 to 2017).

We searched ongoing trials with the search engines provided at the web sites www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.controlled‐trials.com and registries including the WHO ICTRP (www.who.int/ictrp/child/en/) and Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au/trialSearch.aspx).

If required, we would have contacted authors who published in this field for possible unpublished studies.

We searched the reference lists of identified clinical trials and of the review authors' personal files.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used the standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal for conducting a systematic review (neonatal.cochrane.org/en/index.html).

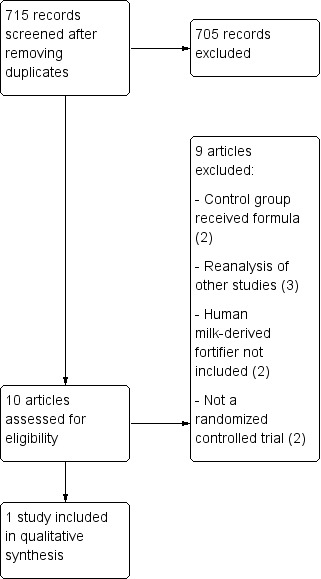

Two review authors (MPr and MPa) independently assessed the titles and the abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy for eligibility for inclusion in this review. We obtained the full‐text articles of studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria, and independently assessed the full‐text articles for inclusion. We resolved any differences by mutual discussion. We listed all studies excluded after full‐text assessment in a ‘Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

We used pre‐designed forms for trial inclusion and exclusion, data extraction, and for requesting additional published information from authors of the original reports. Regarding data extraction, we independently performed this using specifically designed paper forms for identified eligible trials. We compared the extracted data for differences, which we resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MPr and MPa) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high or unclear) of the included trial using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool (Higgins 2017) for the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Any other bias.

We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by consulting the third review author (GSu). See Appendix 2 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported relative risk (RR) and risk difference (RD) values for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes (MDs) when we identified eligible trials. For the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), we calculated these values if there was a statistically significant reduction in RD with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

If we had identified cluster‐randomized trials, analysis would have been conducted at the same level as the allocation, using a summary measurement from each cluster to avoid unit‐of‐analysis errors. Since this might have reduced the power of the study, we intended to apply alternative statistical methods that would allow analysis at the level of the individual while accounting for the clustering.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participating infant in individually randomized trials and the cluster (for example neonatal unit or subunit) for cluster‐randomized controlled trials.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of published studies if we needed clarification of details or for additional information. In the case of missing data, we described the number of participants with missing data in the ‘Results' section and the ‘Characteristics of included studies' table. We presented results for the available participants. We discussed the implications of the missing data in the ‘Discussion' section of the review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Since only one study was eligible, the issue of heterogeneity was irrelevant. However, if there were multiple eligible studies, we would have estimated the treatment effects of individual trials and examined heterogeneity between trials by inspecting the forest plots and quantifying the impact of heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We planned to grade the degree of heterogeneity as low (25% to 50%), moderate (51% to 75%) or high (> 75%). If we had detected statistical heterogeneity, we planned to explore the possible causes (for example, differences in study quality, participants, intervention regimens or outcome assessments) using post‐hoc subgroup analyses. We planned to use a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there were multiple eligible studies, we planned to investigate reporting and publication bias by examining the degree of asymmetry of a funnel plot. When we suspected reporting bias, we intended to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. If this was not possible and if we considered the missing data to have introduced serious bias, we planned to explore the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by sensitivity analyses.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software for statistical analysis. A fixed‐effect model was used for meta‐analysis (RevMan 2014). We performed statistical analyses according to the recommendations of Cochrane Neonatal.

No cluster‐randomized controlled trials were included in this review. If cluster‐RCTs were identified, we planned to perform analysis of cluster‐RCTs as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017).

Quality of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of the evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes.

All‐cause mortality up to hospital discharge and the first year of life.

Necrotizing enterocolitis confirmed either at surgery or autopsy or diagnosed clinically.

Adequacy of growth during the intervention, based on change of weight, length, and head circumference

Feeding intolerance as assessed by the interruptions in enteral feeds requiring parenteral nutrition.

Invasive infection as defined by detection by culture of bacteria or fungus from blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine or other body fluids which are usually sterile.

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of the evidence for each of the outcomes listed above. We considered evidence from randomized controlled trials as high‐quality evidence, but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to create a ‘Summary of findings’ table to report the quality of the evidence (GRADEpro GDT).

The GRADE approach resulted in an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence to one of four grades.

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We could not perform the prespecified subgroup analyses as we included only one study. We will perform the subgroup analysis when more data become available in the future.

Gestational age: preterm (32 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks) versus very preterm (28 0/7 to 31 6/7 weeks) versus extremely preterm (< 28 0/7) weeks.

Birth weight: < 1000 g versus 1000 g to 1499 g versus ≥ 1500 g.

Postnatal age: early (< 8 days postnatal age) versus late (≥ 8 days postnatal age).

Volume of enteral feeds at initiation of fortification: low volume feed fortification (fortification at feed volumes < 60 mL/kg/d) versus high volume feed fortification (fortification at feed volumes ≥ 60 mL/kg/d).

Duration of fortification (postmenstrual age): until 34 weeks' postmenstrual age versus beyond 34 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Length of fortification: total duration of < 4 weeks versus ≥ 4 weeks.

Growth restriction: presence of growth restriction at birth versus absence of growth restriction at birth.

Type of enteral breast milk: i. all mother’s own milk versus all donor breast milk; ii. majority mother’s own milk (> 50% of total enteral breast milk) versus majority donor breast milk (> 50% of total enteral breast milk).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to explore sensitivity analyses by excluding studies with high risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

See also Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

See Figure 1 for description of the study selection process.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included one study in this evaluation in which 127 infants were enrolled (O'Connor 2018). This trial was performed in two tertiary neonatal intensive care units in Canada.

Participants

This trial included preterm infants with a birth weight of less than 1250 g. Infants were excluded if they had chromosomal or congenital anomalies, if they were fed with bovine milk‐derived formula prior to the end of the intervention, or if unable to feed enterally within 14 days after birth. Average gestational age and birth weight of the included infants were 27.7± 2.5 weeks and 888 ± 201 g, respectively.

Interventions

All infants were fed primarily with mother's own milk and, if not available, pasteurized donor breast milk was used. No infant received bovine milk‐derived formula prior to the end of the study period when mother's own milk was not available. Infants were excluded if they were fed bovine milk‐derived formula prior to the end of intervention. Feeding interventions were masked, with unmarked delivery devices either in amber colored syringes or bottles wrapped with colored paper. The fortification of human milk was commenced when a feed volume of 100 mL/kg/d was reached. In the intervention group, liquid human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier Prolact+ (Prolacta Bioscience) was used. In the control group, bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier Similac Human Milk Fortifier Powder (Abbott Nutrition) was used. A standardized weight‐based feeding protocol was followed. In the intervention group, human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier was provided in three strengths of fortification; at 24 kcal/oz, 26 kcal/oz and 28 kcal/oz. In the control group, fortification was introduced to achieve 22 kcal/oz and later advanced to 24 kcal/oz. In the control group, donor milk was also fortified with protein modular (Beneprotein, Nestle). Both groups received standard multivitamin and iron drops.

Outcomes

In this study, feeding intolerance was included as a primary outcome. The secondary outcomes were necrotizing enterocolitis ≥ stage 2, severe retinopathy of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, late onset sepsis, and mortality.

Excluded studies

Two randomized controlled trials that addressed the use of human milk‐derived fortifier were excluded. In these randomized controlled trials, mother's own milk in the control group was supplemented with formula instead of donor breast milk (Cristofalo 2013; Sullivan 2010). Subsequent reanalyses of these studies (Cristofalo 2013; Sullivan 2010) led to three reports (Abrams 2014; Ganapathy 2012; Ghandehari 2012) which were also excluded. The other excluded studies did not utilize human milk‐derived fortifier in either of the comparisons (Adhisivam 2018; Corpeleijn 2016). They included comparisons of donor milk with and without bovine milk‐derived fortifier. Two studies were excluded since they were not randomized controlled studies (Assad 2016; Colacci 2017).

Risk of bias in included studies

In the only included study (O'Connor 2018), the risk of bias was low.

Allocation

In the included study (O'Connor 2018), block randomization of 4 was used. Randomization was performed by an online third‐party service. Hence the allocation bias was deemed low.

Blinding

The only included study (O'Connor 2018) was blinded to the participant, medical care team and the research team. The feeds were masked during delivery by using amber colored tubing and colored paper‐wrapped bottles. Hence, both the performance bias and detection bias were determined to be low.

Incomplete outcome data

The attrition bias in the included study (O'Connor 2018) was low. Only 2 out of 127 infants were excluded since they died before introduction of the fortified feeds. Both of those infants were from the control group.

Selective reporting

The reporting bias was considered low in the included study (O'Connor 2018) since all the predetermined outcomes were reported.

Other potential sources of bias

No other sources of bias were noted.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1 for the main comparison.

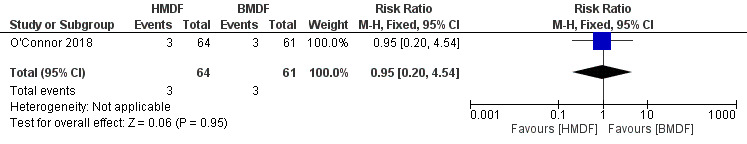

Necrotizing enterocolitis (Outcome 1.1)

The estimated risk ratio was 0.95 (95% CI 0.20 to 4.54; RD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.07; one study, 125 participants; low certainty evidence). No difference in the rate of necrotizing enterocolitis was observed with the use of human milk‐derived fortifier in preterm infants fed with breast milk. The certainty of evidence was downgraded due to imprecision and inclusion of a single study (Analysis 1.1) ( Figure 2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 1 Necrotizing Enterocolitis Stage 2 or greater.

2.

Forest plot of comparison: Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, outcome: 1.1 Necrotizing Enterocolitis Stage 2 or greater.

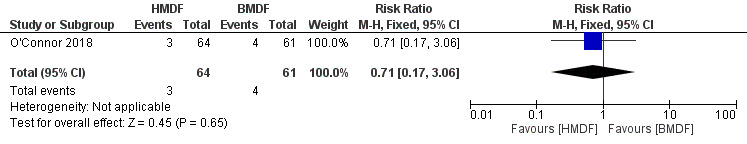

Death (Outcome 1.2)

There was no difference in the rate of death between the two interventions (RR 0.71, 95% 0.17 to 3.06; RD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.06; one study, 125 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.2) (Figure 3). The evidence was considered low‐certainty due to wide confidence intervals from a single eligible study.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 2 Death.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, outcome: 1.2 Death.

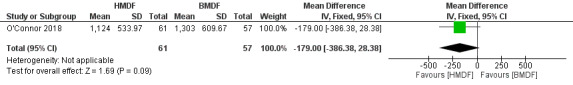

Growth rates (Outcomes 1.3 to 1.8)

Growth was assessed with interval increases in weight, height and head circumference between the beginning and the end of the intervention. The rate of growth beyond the study period, was not assessed. Hence, the assessment at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age or discharge was not performed. The risk estimates derived from a single eligible study reflected imprecision with wide confidence intervals, hence the certainty of evidence was considered to be low.

Weight (Outcomes 1.3 and 1.4)

The use of human milk‐derived fortifier did not affect weight gain as assessed by change in weight in grams (MD ‐179, 95% CI ‐386.38 to 28.38; one study, 118 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.3) (Figure 4) and in weight‐for‐age z scores (MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐0.73 to 0.33; one study, 118 participants) (Analysis 1.4). The evidence was downgraded to low certainty due to imprecision and inclusion of a single study.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 3 Weight: Change during intervention (g).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, outcome: 1.3 Weight: Change during intervention (g).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 4 Weight‐for‐age z score (change during intervention).

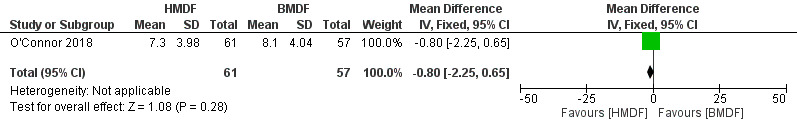

Length (Outcomes 1.5 and 1.6)

No differences were noted in length as assessed by change in length in cms (MD ‐0.8, 95% CI ‐2.25 to 0.65; one study, 118 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.5) (Figure 5) and in length‐for‐age z score (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.57 to 0.77; one study, 118 participants) (Analysis 1.6). Due to wide confidence intervals of the risk estimates and inclusion of a single study, the evidence was considered to be of low certainty.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 5 Length: Change during intervention (cm).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, outcome: 1.5 Length: Change during intervention (cm).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 6 Length‐for‐age z score (change during intervention).

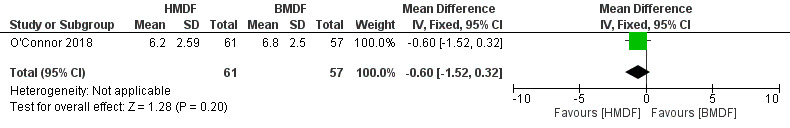

Head circumference (Outcomes 1.7 to 1.8)

No significant differences were noted in head circumference measurements as assessed by head circumference in cm (MD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.52 to 0.32; one study, 118 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.7) (Figure 6) and head circumference‐for‐age z score (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.49; one study, 118 participants) (Analysis 1.8). The evidence was downgraded to low certainty due to imprecision and inclusion of a single study.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 7 Head circumference: Change during intervention (cm).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, outcome: 1.7 Head Circumference: Change during intervention (cm).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 8 Head circumference‐for‐age Z score (change during intervention).

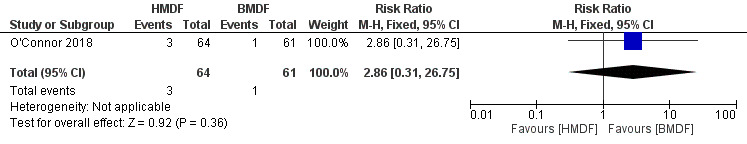

Feeding intolerance (Outcomes 1.9 to 1.11)

Feeding intolerance was measured by several comparisons. All the comparisons failed to show significant difference between the interventions including feeding interruption requiring parenteral nutrition (RR 2.86, 95% CI 0.31 to 26.75; RD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.06; one study, 125 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.9) (Figure 7), gastric residuals (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.51; RD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.17, one study, 125 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.10), and abdominal distension (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.10; RD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.08, one study, 125 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.11). Due to inclusion of a single study and the wide confidence intervals of the risk estimates, the evidence was termed as low certainty.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 9 Feeding interruption requiring parenteral nutrition.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, outcome: 1.9 Feeding interruption requiring parenteral nutrition.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 10 Gastric residuals.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 11 Abdominal distension.

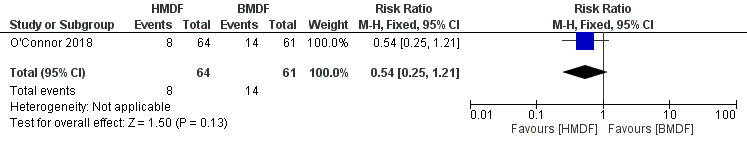

Late onset sepsis (Outcome 1.12)

No significant difference in the rate of late‐onset‐sepsis was noted with the use of human milk‐derived fortifier in preterm infants fed with breast milk (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.21; RD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.03; one study, 125 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.12) (Figure 8). We downgraded the evidence to low certainty because of inclusion of a single study and wide confidence intervals.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 12 Late‐onset sepsis.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, outcome: 1.12 Late‐onset sepsis.

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (Outcome 1.13)

Human milk‐derived fortifiers did not affect the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in breast milk‐fed preterm infants (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.51; RD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.11; one study, 125 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.13). We concluded that the certainty of evidence was low due to imprecision coming from a single eligible study.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 13 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Retinopathy of prematurity (Outcomes 1.14)

Use of human milk‐derived fortifier in preterm infants fed with breast milk had no effect on the risk of retinopathy of prematurity requiring intervention (RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.28; RD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.00; one study, 121 participants; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.14). We downgraded the evidence to low certainty due to imprecision, and because data was derived from a single study.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 14 Retinopathy of prematurity requiring intervention.

Discussion

Summary of main results

A single randomized controlled trial with 127 extremely low birth weight infants was included in this review (O'Connor 2018). In this study, a comparison between human milk‐derived fortifier and bovine milk‐derived fortifier was made in preterm infants fed exclusively with human milk. Limited evidence from this systematic review suggested that fortification with human milk‐derived fortifier when compared with bovine milk‐derived fortifier had similar effects on the incidence of feeding intolerance, or the risks of necrotizing enterocolitis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, late‐onset sepsis, severe retinopathy of prematurity, or mortality. The use of human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier did not result in significant differences in the short‐term growth parameters measured during the period of intervention. The use of human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier was safe and well tolerated.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Since only one study with a small sample size was (O'Connor 2018) eligible for inclusion, caution is advised when interpreting and applying results of this systematic review into practice. The included study had low risk of bias. In two excluded studies (Sullivan 2010; Cristofalo 2013), the control groups received infant formula instead of donor breast milk to supplement shortage of mother’s own milk. Introduction of infant formula (a bovine product) to the control group makes the assessment of the use of bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier both inaccurate and impossible. The effect of human milk‐derived fortifier on a diet composed of breast milk can only be assessed in the absence of exposure to bovine protein originating from the infant formula. In the study included in this systematic review (O'Connor 2018), all the infants were fed exclusively with either mother's milk or donor breast milk. The utilization of infant formula was excluded to ensure accurate comparisons between multi‐nutrient fortifiers. This practice of resorting to donor milk to supplement mother’s own milk instead of infant formula is also the standard of care of very low birth weight preterm infants in modern neonatal intensive care units.

The use of human milk‐derived fortifier in this study was safe. Studies comparing donor breast milk to infant formula have reported decreased short‐term growth in infants fed with exclusive breast milk (Quigley 2018). In this study (O'Connor 2018), infants fed with human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier demonstrated similar growth rates compared to infants fed with bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier over the period of the intervention.

Quality of the evidence

The included study had low risk of bias (O'Connor 2018). The processes to allow concealment of random allocation were satisfactory. Blinding of participants, caregivers, clinicians, and the investigators was achieved well and there was no perceived bias in the assessments. Since the summary estimate from this single included study with small number of subjects was associated with large confidence intervals, the evidence was assessed to be of low certainty due to imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

We strived to decrease biases in the review process by a comprehensive search including screening reference lists of related reviews and included trials. In order to identify trials that were not yet published in full format in scientific journals, we conducted searches from the proceedings of major international neonatal‐perinatal conferences. Two reviewers identified trials for inclusion and extracted data from eligible trials.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No other review has addressed the need to assess the effect of human milk‐derived fortifier in exclusively breastfed preterm infants. The lack of generalizability and the barriers due to cost was also expressed by the authors in a commentary published earlier (Embleton 2017).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Low‐certainty evidence from one study suggests that fortification of breast milk feeds with the human milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier in comparison to bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifier in exclusively breast milk‐fed preterm infants, may not affect necrotizing enterocolitis, mortality, growth parameters, feeding intolerance, or late‐onset sepsis.

Implications for research.

Well designed studies, comparing the use of human milk‐derived and bovine milk‐derived multi‐nutrient fortifiers in the setting of exclusive breast milk usage are required to evaluate short‐term outcomes including necrotizing enterocolitis, mortality, feeding intolerance, and long term growth and neurodevelopment. Parental preference for this product and lack of equipoise among the medical teams might be potential barriers for enrolment and participation in such research studies.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of Ms. Marianne Galati, MS, MLIS and Ms. Beatriz Varman, MLIS, AHIP at The Texas Medical Center Library, Houston, Texas in devising the search strategy for this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methodology

We searched the following databases for relevant trials in any language.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, current issue).

Electronic journal reference databases: MEDLINE (1980 to September 2018) and PREMEDLINE, Embase (1980 to September 2018) and CINAHL (1982 to September 2018).

Biological abstracts in the database BIOSIS and conference abstracts from 'Proceedings First' (from 1992 to 2011).

The following text words and MeSH terms comprised the MEDLINE and PREMEDLINE search strategy. We adapted this to suit Embase, CINAHL and CENTRAL.

(((((((("Infant, Newborn"[Mesh] OR "Infant, Extremely Premature"[Mesh] OR "Infant, Premature"[Mesh] OR "Infant, Low Birth Weight"[Mesh] OR "Infant, Very Low Birth Weight"[Mesh] OR "Infant, Small for Gestational Age"[Mesh] OR "Gestational Age"[Mesh] OR "Infant, Extremely Low Birth Weight"[Mesh] OR neonat*[tiab] OR infant*[tiab] OR newborn*[tiab] OR gestation*[tiab] OR "pre‐term"[tiab] OR “birth weight”[tiab] OR neonat*[OT] OR infant*[OT] OR newborn*[OT] OR gestation*[OT] OR "pre‐term"[OT] OR “birth weight”[OT])) AND ((("Infant Formula"[Mesh] OR "Milk, Human"[Mesh] OR "Breast Feeding"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "Feeding Methods"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "Milk"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "Food, Fortified"[Mesh] OR "Milk Banks"[Mesh] OR "Infant Nutritional Physiological Phenomena"[Mesh:NoExp] OR milk[tiab] OR formula[tiab] OR feeding[tiab] OR Milk[OT] OR formula[OT] OR feeding[OT])) AND ((fortif*[tiab] OR exclusiv*[tiab] OR predominant*[tiab] OR supplement*[tiab] OR enteral[tiab] OR fortif*[OT] OR exclusiv*[OT] OR predominant*[OT] OR supplement*[OT] OR enteral[OT])))) AND (("Enterocolitis, Necrotizing"[Mesh] OR "Retinopathy of Prematurity"[Mesh] OR "Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia"[Mesh] OR "Mortality"[Mesh] OR "Infant Mortality"[Mesh] OR "Morbidity"[Mesh] OR "necrotizing enterocolitis"[tiab] OR “necrotising enterocolitis”[tiab] OR NEC[tiab] OR "retinopathy of prematurity"[tiab] OR "bronchopulmonary dysplasia"[tiab] OR "Mortality"[tiab] OR "Morbidity"[tiab] OR "necrotizing enterocolitis"[OT] OR “necrotising enterocolitis”[OT] OR NEC[OT] OR "retinopathy of prematurity"[OT] OR "bronchopulmonary dysplasia"[OT] OR "Mortality"[OT] OR "Morbidity"[OT])))) NOT (((animals NOT humans)))) AND ( "2003/01/01"[PDat] : "3000/12/31"[PDat] ))) AND ((randomized controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt] OR randomized[tiab] OR placebo[tiab] OR clinical trials as topic[mesh:noexp] OR randomly[tiab] OR trial[ti] NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans [mh])))

Appendix 2. Risk of bias tool

We used the standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal to assess the methodological quality of the trials. For each trial, we sought information regarding the method of randomization, blinding and reporting of all outcomes of all the infants enrolled in the trial. We assessed each criterion as being at a low, high or unclear risk of bias. Two review authors separately assessed each study. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We have added this information to the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. We evaluated the following issues and entered the findings into the 'Risk of bias' table.

1. Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

For each included study, we categorized the method used to generate the allocation sequence as:

low risk (any truly random process e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk (any non‐random process e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk.

2. Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). Was allocation adequately concealed?

For each included study, we categorized the method used to conceal the allocation sequence as:

low risk (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth); or

unclear risk.

3. Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?

For each included study, we categorized the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or class of outcomes. We then categorized the methods as:

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for participants; and

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for personnel.

4. Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented at the time of outcome assessment?

For each included study, we categorized the methods used to blind outcome assessment. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or class of outcomes. We categorized the methods as:

low risk for outcome assessors;

high risk for outcome assessors; or

unclear risk for outcome assessors.

5. Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations). Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

For each included study and for each outcome, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We noted whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported or supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses. We categorized the methods as:

low risk (< 20% missing data);

high risk (≥ 20% missing data); or

unclear risk.

6. Selective reporting bias. Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. For studies in which study protocols were published in advance, we planned to compare pre‐specified outcomes versus outcomes eventually reported in the published results. If the study protocol was not published in advance, we planned to contact study authors to gain access to the study protocol. We assessed the methods as:

low risk (where it is clear that all of the study's pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk (where not all the study's pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified outcomes of interest and are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported); or

unclear risk.

7. Other sources of bias. Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

For each included study, we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias (for example, whether there was a potential source of bias related to the specific study design or whether the trial was stopped early due to some data‐dependent process). We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as:

low risk;

high risk;

unclear risk.

If needed, we explore the impact of the level of bias by undertaking sensitivity analyses.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Necrotizing Enterocolitis Stage 2 or greater | 1 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.20, 4.54] |

| 2 Death | 1 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.17, 3.06] |

| 3 Weight: Change during intervention (g) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐179.0 [‐386.38, 28.38] |

| 4 Weight‐for‐age z score (change during intervention) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.2 [‐0.73, 0.33] |

| 5 Length: Change during intervention (cm) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.80 [‐2.25, 0.65] |

| 6 Length‐for‐age z score (change during intervention) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.57, 0.77] |

| 7 Head circumference: Change during intervention (cm) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐1.52, 0.32] |

| 8 Head circumference‐for‐age Z score (change during intervention) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.49, 0.49] |

| 9 Feeding interruption requiring parenteral nutrition | 1 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.86 [0.31, 26.75] |

| 10 Gastric residuals | 1 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.65, 1.51] |

| 11 Abdominal distension | 1 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.80, 1.10] |

| 12 Late‐onset sepsis | 1 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.25, 1.21] |

| 13 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.48, 1.51] |

| 14 Retinopathy of prematurity requiring intervention | 1 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.02, 1.28] |

| 15 Necrotizing Enterocolitis Stage 2 or greater | 1 | 125 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.08, 0.07] |

| 16 Feeding interruption requiring parenteral nutrition | 1 | 125 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.10, 0.06] |

| 17 Gastric residuals | 1 | 125 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.18, 0.17] |

| 18 Abdominal distension | 1 | 125 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.06 [‐0.19, 0.08] |

| 19 Death | 1 | 125 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.10, 0.06] |

| 20 Late‐onset sepsis | 1 | 125 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.24, 0.03] |

| 21 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 125 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.20, 0.11] |

| 22 Retinopathy of prematurity requiring intervention | 1 | 121 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.17, ‐0.00] |

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 15 Necrotizing Enterocolitis Stage 2 or greater.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 16 Feeding interruption requiring parenteral nutrition.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 17 Gastric residuals.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 18 Abdominal distension.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 19 Death.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 20 Late‐onset sepsis.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 21 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Human milk‐derived vs. Bovine milk‐derived fortifier, Outcome 22 Retinopathy of prematurity requiring intervention.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

O'Connor 2018.

| Methods | Randomized clinical trial | |

| Participants | 127 infants < 1250 g Exclusion criteria: Receipt of formula or bovine milk‐based fortifier prior to randomization and if enteral feeding not commenced within 14 days after birth. Congenital or chromosomal anomaly affecting growth. Setting: 2 tertiary NICUs, Sinai Health System and The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention: (N = 64) Mother's own milk or pasteurized donor human milk fortified with human milk‐based fortifier (HMBF) (Prolact+, Prolacta Bioscience) to achieve 0.81 kcal/mL (24 kcal/oz), and 0.88 kcal/mL (26 kcal/oz), Control: (N = 63) Mother's own milk or pasteurized donor human milk fortified with bovine milk‐based fortifier (BMBF) (Similac Human Milk Fortifier Powder, Abbott Nutrition) to 0.72 kcal/mL (22 kcal/oz) and 0.78 kcal/mL (24 kcal/oz), and with the addition of powdered formula (Similac Neosure, Abbott Nutrition) to further concentrate feeds to 0.88 kcal/mL (26 kcal/oz). | |

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Fortification of breast milk in both groups commenced at feed volumes of ≥ 100 mL/kg/d. In the HMBF group, fortification began at 0.81 kcal/mL (24 kcal/oz), and increased to 0.88 kcal/mL (26 kcal/oz) when volume reached 140 mL/kg/d. In the BMBF group, fortification began at 0.72 kcal/mL (22 kcal/oz) and increased to 0.78 kcal/mL (24 kcal/oz) when volumes reached 140 mL/kg/d. In the BMBF group, intact‐protein modular (Beneprotein, Nestle) was added to donor milk after fortification had reached up to 0.78 kcal/mL) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomization of 4 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation by an online third party service |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Triple‐blind study. Feeding assignments were masked using amber colored tubing and color wrapping for bottles. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Self‐reported outcomes | Low risk | Triple‐blind study. The reporting team was blinded to the intervention. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Objective outcomes | Low risk | Triple blind‐study. The reporting team was blinded to the intervention. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Two infants (2/63) in the control group were excluded since they died before intervention. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes planned were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None noted |

BMBF: Bovine milk‐derived fortifier HMBF: Human milk‐derived fortifier NEC: Necrotizing enterocolitis NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abrams 2014 | A combined reanalysis of Sullivan 2010 and Cristofalo 2013 studies. The control group received bovine milk‐based preterm formula instead of donor breast milk to supplement mother's own milk. |

| Adhisivam 2018 | The control group did not receive any fortification. |

| Assad 2016 | The study design involved a retrospective study. |

| Colacci 2017 | The study design involved a retrospective study comparing human milk‐derived fortifier with bovine milk‐derived fortifier. |

| Corpeleijn 2016 | In this study, the comparison was between donor milk and formula. |

| Cristofalo 2013 | The control group received preterm formula instead of donor breast milk to supplement mother's own milk. |

| Ganapathy 2012 | This was a cost‐effectiveness analysis of human milk‐based diet. The subjects comprised the study groups from Sullivan 2010 study. The control group was supplemented with bovine milk‐based formula instead of donor breast milk. |

| Ghandehari 2012 | Reanalysis of Sullivan 2010 study |

| Sullivan 2010 | In this study, the control group received bovine milk‐based formula instead of donor breast milk to supplement mother's own milk. |

Differences between protocol and review

The following changes have been made to the Summary of findings table:

Deletion: Since the outcomes, duration of parenteral nutrition (in days) and length of hospital stay (in days) were not reported in the included study, we removed them from the list of outcomes chosen to assess the quality of outcomes using the GRADE approach.

Addition: We included in the list of outcomes eligible for assessment of quality of outcomes using the GRADE approach the following: anthropometric outcomes as assessed by change in weight, length, head circumference during the intervention; and feeding intolerance as assessed by interruption in feeds requiring initiation of parenteral nutrition.

Contributions of authors

Muralidhar H. Premkumar, Mohan Pammi and Gautham Suresh conceived and developed the protocol. Muralidhar H. Premkumar assisted in devising the search strategy and wrote the initial protocol. Mohan Pammi and Gautham Suresh reviewed the versions and approved the final version.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

None, Other.

No internal sources of support were utilized in the preparation of this protocol.

External sources

-

Vermont Oxford Network, USA.

Cochrane Neonatal Reviews are produced with support from Vermont Oxford Network, a worldwide collaboration of health professionals dedicated to providing evidence‐based care of the highest quality for newborn infants and their families.

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

This report is independent research funded by a UK NIHR Cochrane Programme Grant (16/114/03). The views expressed in this publication are those of the review authors and are not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health.

-

The Gerber Foundation, USA.

Editorial support for this review, as part of a suite of preterm nutrition reviews, has been provided by a grant from The Gerber Foundation. The Gerber Foundation is a separately endowed, private, 501(c)(3) foundation not related to Gerber Products Company in any way.

Declarations of interest

Muralidhar H Premkumar has no known conflicts of interest relevant to this review. Mohan Pammi has no known conflicts of interest relevant to this review. Gautham Suresh has no known conflicts of interest relevant to this review.

The methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Neonatal.

Core editorial and administrative support for this review has been provided by a grant from The Gerber Foundation. The Gerber Foundation is a separately endowed, private foundation, distinct from the Gerber Products Company. The grantor has no input on the content of the review or the editorial process.

In order to maintain the utmost editorial independence for this Cochrane Review, an editor outside of the Cochrane Neonatal core editorial team who is not receiving any financial remuneration from the grant, William McGuire, was the Sign‐off Editor for this review. Additionally, a Senior Editor from the Cochrane Children and Families Network, Robert Boyle, assessed and signed off on this Cochrane Review.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

O'Connor 2018 {published data only}

- O'Connor DL, Kiss A, Tomlinson C, Brando N, Bayliss A, Campbell DM, et al. OptiMoM Feeding Group. Nutrient enrichment of human milk with human and bovine milk–based fortifiers for infants born weighing <1250 g: a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018;108(1):108‐16. [DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy067; PUBMED: 29878061] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Abrams 2014 {published data only}

- Abrams SA, Schanler RJ, Lee ML, Rechtman DJ. Greater mortality and morbidity in extremely preterm infants fed a diet containing cow milk protein products. Breastfeeding Medicine 2014;9(6):281‐5. [DOI: 10.1089/bfm.2014.0024; PUBMED: 24867268] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Adhisivam 2018 {published data only}

- Adhisivam B, Kohat D, Tanigasalam V, Bhat V, Plakkal N, Palanivel C. Does fortification of pasteurized donor human milk increase the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis among preterm neonates? A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2018;18(18):1‐6. [DOI: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1461828; PUBMED: 29618272] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Assad 2016 {published data only}

- Assad M, Elliott MJ, Abraham JH. Decreased cost and improved feeding tolerance in VLBW infants fed an exclusive human milk diet. Journal of Perinatology 2016;36(3):216‐20. [DOI: 10.1038/jp.2015.168; PUBMED: 26562370] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Colacci 2017 {published data only}

- Colacci M, Murthy K, DeRegnier RO, Khan JY, Robinson DT. Growth and development in extremely low birth weight infants after the introduction of exclusive human milk feedings. American Journal of Perinatology 2017;34(2):130‐7. [DOI: 10.1055/s-0036-1584520; PUBMED: 27322667] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corpeleijn 2016 {published data only}

- Corpeleijn WE, Waard M, Christmann V, Goudoever JB, Jansen‐Van der Weide MC, Kooi EM, et al. Effect of donor milk on severe infections and mortality in very low‐birth‐weight infants: the early nutrition study randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics 2016;170(7):654‐61. [DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0183; PUBMED: 27135598] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cristofalo 2013 {published data only}

- Cristofalo EA, Schanler RJ, Blanco CL, Sullivan S, Trawoeger R, Kiechl‐Kohlendorfer U, et al. Randomized trial of exclusive human milk versus preterm formula diets in extremely premature infants. Journal of Pediatrics 2013;163(6):1592‐5. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.011; PUBMED: 23968744] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ganapathy 2012 {published data only}

- Ganapathy V, Hay JW, Kim JH. Costs of necrotizing enterocolitis and cost‐effectiveness of exclusively human milk‐based products in feeding extremely premature infant. Breastfeeding Medicine 2012;7(1):29‐37. [DOI: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0002; PUBMED: 21718117] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ghandehari 2012 {published data only}

- Ghandehari H, Lee ML, Rechtman DJ, H2MF Study Group. An exclusive human milk‐based diet in extremely premature infants reduces the probability of remaining on total parenteral nutrition: a reanalysis of the data. BMC Research Notes 2012;5(188):1‐5. [DOI: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-188; PUBMED: 22534258] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sullivan 2010 {published data only}

- Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, Patel AL, Trawoger R, Kiechl‐Kohlendorfer U, et al. An exclusively human milk‐based diet is associated with a lower rate of necrotizing enterocolitis than a diet of human milk and bovine milk‐based products. Journal of Pediatrics 2010;156(4):562‐7. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.040; PUBMED: 20036378] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

AAP 2012

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):e827‐41. [DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552; PUBMED: 22371471] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Abrams 2013

- Abrams SA, Committee on Nutrition. Calcium and vitamin D requirements of enterally fed preterm infants. Pediatrics 2013;131(5):e1676‐83. [DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-0420; PUBMED: 23629620] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Agostini 2010

- Agostoni C, Buonocore G, Carnielli VP, Curtis M, Darmaun D, Decsi T, et al. ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Enteral nutrient supply for preterm infants: commentary from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology Nutrition 2010;50(1):85‐91. [DOI: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181adaee0; PUBMED: 19881390] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bayley 1993

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2nd Edition. London (UK): Pearson, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Bayley 2005

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 3rd Edition. London (UK): Pearson, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Blencowe 2012

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379(9832):2162‐72. [DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4; PUBMED: 22682464] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 2016

- Brown JV, Embleton ND, Harding JE, McGuire W. Multi‐nutrient fortification of human milk for preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000343.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dutta 2015

- Dutta S, Singh B, Chessell L, Wilson J, Janes M, McDonald K, et al. Guidelines for feeding very low birth weight infants. Nutrients 2015;7(1):423‐42. [DOI: 10.3390/nu7010423; PUBMED: 25580815] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Embleton 2007

- Embleton ND. Optimal protein and energy intakes in preterm infants. Early Human Development 2007;83(12):831‐7. [DOI: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.10.001; PUBMED: 17980784] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Embleton 2017

- Embleton N, Cleminson J. Randomized trial of exclusive human milk versus preterm formula diets in extremely premature infants. Acta Paediatrica 2017;106(9):1538. [DOI: 10.1111/apa.13820; PUBMED: 28397283] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gathwala 2007

- Gathwala G, Chawla M, Gehlaut VS. Fortified human milk in the small for gestational age neonate. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2007;74(9):815‐8. [PUBMED: 17901665] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gephart 2012

- Gephart SM, McGrath JM, Effken JA, Halpern MD. Necrotizing enterocolitis risk: state of the science. Advances in Neonatal Care 2012;12(2):77‐87. [DOI: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e31824cee94; PUBMED: 22469959] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GRADEpro GDT [Computer program]

- McMaster University (developed by Evidence Prime). GRADEpro GDT. Version accessed 16 October 2017. Hamilton (ON): McMaster University (developed by Evidence Prime), 2015.

Higgins 2017

- Higgins JP, Green S, editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2017. Available from training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Horbar 2012

- Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Badger GJ, Kenny MJ, Soll RF, Morrow KA, et al. Mortality and neonatal morbidity among infants 501 to 1500 grams from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics 2012;129(6):1019‐26. [DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-3028; PUBMED: 22614775] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hsiao 2014

- Hsiao CC, Tsai ML, Chen CC, Lin HC. Early optimal nutrition improves neurodevelopmental outcomes for very preterm infants. Nutrition Reviews 2014;72(8):532‐40. [DOI: 10.1111/nure.12110; PUBMED: 24938866] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ICROP 2005

- International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Archives of Ophthalmology 2005;123(7):991‐9. [DOI: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991; PUBMED: 16009843] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jobe 2001

- Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2001;163(7):1723‐9. [DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060; PUBMED: 11401896] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lager 2012

- Lager S, Powell TL. Regulation of nutrient transport across the placenta. Journal of Pregnancy 2012:179827. [DOI: 10.1155/2012/179827; PUBMED: 23304511] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lönnerdal 2017

- Lönnerdal B. Bioactive proteins in human milk‐potential benefits for preterm infants. Clinics in Perinatology 2017;44(1):179‐91. [DOI: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.11.013; PUBMED: 28159205] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maas 2018

- Maas C, Franz AR, Krogh S, Arand J, Poets CF. Growth and morbidity of extremely preterm infants after early full enteral nutrition. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2018;103(1):F79‐81. [DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312917; PUBMED: 28733478] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McNelis 2017

- McNelis K, Fu TT, Poindexter B. Nutrition for the extremely preterm infant. Clinics in Perinatology 2017;44(2):395‐406. [DOI: 10.1016/j.clp.2017.01.012; PUBMED: 28477668] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mimouni 2017

- Mimouni FB, Nathan N, Ziegler EE, Lubetzky R, Mandel D. The use of multinutrient human milk fortifiers in preterm infants: a systematic review of unanswered questions. Clinics in Perinatology 2017;44(1):173‐8. [DOI: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.11.011; PUBMED: 28159204] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mitchell 2009

- Mitchell SM, Rogers SP, Hicks PD, Hawthorne KM, Parker BR, Abrams SA. High frequencies of elevated alkaline phosphatase activity and rickets exist in extremely low birth weight infants despite current nutritional support. BMC Pediatrics 2009;9:47. [DOI: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-47; PUBMED: 19640269] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moher 2009