Abstract

Eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair (MMR) involves both Exonuclease 1 (Exo1)-dependent and -independent pathways. We found that the unstructured C-terminal domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Exo1 contains two Msh2-Interacting-Peptide (SHIP) boxes downstream from the Mlh1-Interacting-Peptide (MIP) box. These three sites were redundant in Exo1-dependent MMR in vivo and could be replaced by an N-terminal-Exo1-Msh6 fusion protein. The SHIP-Msh2 interactions were eliminated by the msh2-M470I mutation and wild-type but not mutant SHIP peptides eliminated Exo1-dependent MMR in vitro. We identified two S. cerevisiae SHIP box-containing proteins and three candidate human SHIP box-containing proteins. One of these, Fun30, played a small role in Exo1-dependent MMR in vivo. The Rsc complex acted in both Exo1-dependent and Exo1-independent MMR in vivo. Our results identified two modes of Exo1 recruitment and a peptide module that mediates interactions between Msh2 and other proteins, and support a model in which Exo1 functions in MMR tethered to the Msh2-Msh6 complex.

Introduction

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) plays a critical role in mutation avoidance by correcting DNA base mispairs generated by errors during DNA replication1,2 and some types of chemical DNA damage and mispairs formed in heteroduplex homologous recombination (HR) intermediates. MMR also prevents HR between divergent DNA sequences3–6. Because of these roles in mutation avoidance, germline MMR defects cause the hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes Lynch syndrome and biallelic MMR deficiency, depending on whether one or two defective alleles are inherited7–9. Sporadic human tumors can also be MMR defective, primarily due to epigenetic silencing of the MLH1 MMR gene7,10. Eukaryotic MMR involves three general steps: 1) recognition of mispaired bases by Msh2-Msh6 or Msh2-Msh3 and recruitment of critical accessory factors such as Mlh1-Pms1; 2) excision of the DNA strand containing the incorrect base; and 3) resynthesis of the excised DNA strand.

Exonuclease 1 (Exo1) is a 5’ to 3’ double stranded DNA exonuclease consisting of a N-terminal nuclease domain and an unstructured C-terminal region1,11 and is the only exonuclease definitively identified in eukaryotic MMR12. Exo1 is required for mispair excision in two reconstituted MMR reactions in vitro: 1) reactions utilizing a circular substrate containing a mispair and a pre-existing nick 5’ to the mispair where Exo1-mediated excision occurs from the nick past the mispair in a reaction that is stimulated by Msh2-Msh6 or Msh2-Msh3 binding to the mispair13–17; and 2) reactions utilizing a circular substrate containing a mispair and a pre-existing nick 3’ to the mispair where Mlh1-Pms1 (human Mlh1-Pms2) in combination with PCNA, RFC, and Msh2-Msh6 or Msh2-Msh3 makes nicks 5’ to the mispair allowing excision by Exo115,17–19. In spite of the complete requirement for Exo1 in most reconstituted MMR reactions, deletion of EXO1 in S. cerevisiae results in a small increase in mutation rates (~1% defect in MMR)12,20, and Exo1−/− mice lack the strong mutator phenotype and early onset cancer phenotype seen in Msh2−/− or Mlh1−/− mice21. Consistent with these results, mutations have been isolated in S. cerevisiae that specifically disrupt either Exo1-dependent or Exo1-independent MMR20,22–24. Two lines of evidence suggest that Exo1-dependent MMR might be more important in vivo: 1) combining the exo1Δ mutation and the lagging strand misincorporation pol3-L612M mutation causes a synergistic increase in mutation rate, suggesting Exo1-dependent repair may be the major pathway for lagging strand MMR25; and 2) the exo1Δ mutation results in a striking accumulation of mispair- and Msh2-dependent Mlh1-Pms1 foci on DNA25, consistent with the idea that Exo1-independent MMR is activated only when Exo1 repair does not occur. Much less is known about the possible mechanisms of Exo1-independent MMR compared to Exo1-dependent MMR1,23,24,26.

Msh2 interacts with the unstructured C-terminal region of Exo112,27, and the C-terminal region of Exo1 also contains a short peptide motif termed the MIP box that mediates an interaction with Mlh128,29. However, the importance of these interactions has been unclear. In this study, we identified two redundant copies of a short peptide motif in the C-terminal tail of Exo1 that mediate the Exo1-Msh2 interaction, termed here the Msh2-interacting peptide (SHIP) box. Recruitment of Exo1 to MMR by the SHIP boxes was redundant with Exo1 recruitment by the MIP box, as eliminating both modes of Exo1 recruitment was required to eliminate Exo1-dependent MMR in vivo. Peptides containing the SHIP box motif disrupted MMR and mispair-promoted excision reactions reconstituted in vitro that were dependent on Msh2-Msh6 and Exo1, indicating these reactions were dependent on the Msh2-SHIP box interaction. Finally, we found that the SHIP box is evolutionarily conserved, and we identified other SHIP box-containing proteins in both S. cerevisiae (Fun30 and Dpb3) and humans (SMARCAD1, WDHD1, and MCM9) that interact with Msh2 and provide evidence that one of these, Fun30, along with the Rsc complex, plays a cooperating role in MMR.

Results

Two sites with a conserved sequence motif in the Exo1 C-terminal tail mediate Msh2 binding.

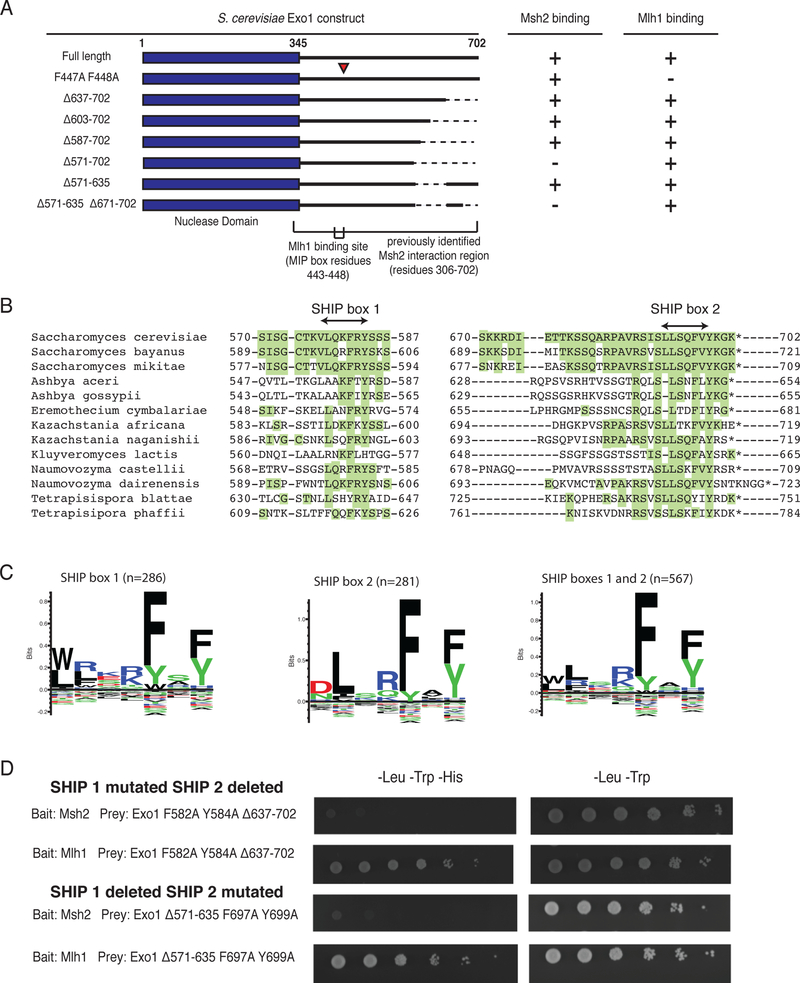

Previous results localized the Msh2 interaction region of Exo1 to the unstructured C-terminal tail (residues 366–702; Figure 1a)12. Protein-truncating mutations (N357X and N396X) that map downstream of the N-terminal nuclease domain (residues G2-K345) and upstream of the MIP box (residues T443-F448) eliminate Exo1-dependent MMR, unlike the MIP box mutations which only cause a minor defect11,20,28,30,31. To more precisely define the Exo1-Msh2 interaction, we tested a series of C-terminal truncations of Exo1 for their interaction with Msh2 or Mlh1 using yeast two-hybrid analysis. As expected, full-length Exo1 interacted with both Msh2 and Mlh1 (Figure 1a, Supplementary Figure 1), and the MIP box mutations (Exo1-F447A, F448A)30 disrupted the Exo1-Mlh1 interaction but not the Exo1-Msh2 interaction (Figure 1a, Supplementary Figure 1). C-terminal truncations of Exo1 up to residue 587 did not affect the Exo1-Msh2 interaction, whereas the C-terminal truncation including residue 571 eliminated the Exo1-Msh2 interaction. Remarkably, the Exo1-Δ571–635 internal deletion construct, which deleted the residues accounting for the differences between the shortest interacting construct (Exo1-Δ587–702) and the longest non-interacting construct (Exo1-Δ571–702), did not affect the Exo1-Msh2 interaction. In contrast, eliminating the last 32 amino acids in this internal deletion construct (Exo1-Δ571–635,Δ671–702) abolished Msh2 binding.

Figure 1. Two regions in the S. cerevisiae Exo1 C-terminal tail mediate Msh2 interaction.

A. Summary of yeast two-hybrid interactions with various Exo1 deletion constructs in prey vectors and their interactions with bait vectors encoding Msh2 or Mlh1. The Exo1-F447A,F448A variant disrupts the Exo1 MIP box and the Mlh1 binding interaction. The Exo1Δ571–702 and Exo1Δ571–635,Δ671–702 disrupt the Msh2 binding sites, but not the Exo1-Mlh1 interaction. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of 4 times. B. Sequence alignment of the Msh2-binding regions of S. cerevisiae Exo1 with closely related fungal species in the Saccharomycotina are displayed so that residues identical to S. cerevisiae are highlighted in green. C. Sequence logos generated by Seq2Logo (ref) for alignments of SHIP box 1, SHIP box 2, and both SHIP boxes based on an alignment of 291 fungal species; note that the number of sequences for each SHIP box is lower than the total number of fungal species analysed due to gene annotation errors and/or lack of conservation of specific SHIP boxes. D. Yeast two-hybrid analysis reveals that the Exo1-F582A,Y584A,Δ637–702 and Exo1Δ571–635,F697A,Y699A constructs failed to interact with the Msh2 bait (lack of growth on –Leu –Trp –His medium as compared to growth on the control –Leu –Trp medium) but still retained interaction with the Mlh1 bait. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of 4 times.

Sequence analysis of residues 570–587 and residues 670–702 of Exo1 in homologs from 291 fungal species revealed short regions of extensive conservation (Figure 1b), which were largely similar to each other (Figure 1c). We termed this shared motif the Msh2 interacting peptide (SHIP) box. The conserved aromatic residues of either the first SHIP box called SHIP1 (F582, Y584) or the second SHIP box called SHIP2 (F697, Y699) were mutated to alanine in a prey construct in which the other SHIP box region had been deleted (Exo1-Δ637–702 [SHIP2] and Exo1-Δ571–635 [SHIP1], respectively). In each case, mutation of the SHIP box in the Exo1 deletion constructs eliminated the ability of these constructs to mediate the Exo1-Msh2 interaction (Figure 1d). Thus the unstructured C-terminal tail of Exo1 contains two redundant motifs required for Msh2 binding and that these motifs likely bind the same site on Msh2.

A SHIP box peptide inhibits MMR and mispair-promoted excision reactions in vitro that depend on Msh2-Msh6 and Exo1.

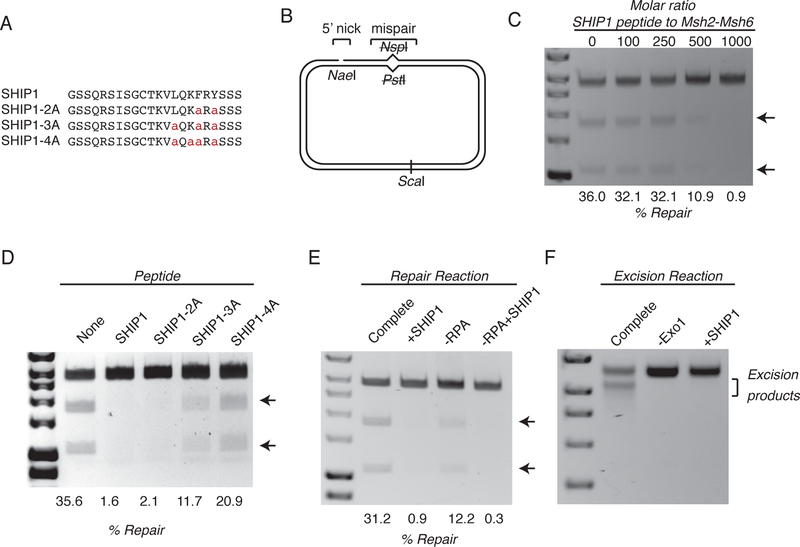

If the SHIP box motifs directly mediated the Exo1-Msh2 interaction, then peptides containing a SHIP box motif (Figure 2a) should compete with the interaction in vitro. In the absence of the SHIP1 peptide, 36% of a plasmid substrate containing a pre-existing nick 5’ to a mispair was repaired (Figure 2b,c; uncropped gel images are shown in Supplementary Data Set 1); this reconstituted MMR reaction is dependent on mispair recognition by Msh2-Msh6, excision by Exo1, and resynthesis of the excised DNA strand by DNA polymerase δ in conjunction with RPA, PCNA and the PCNA loader, RFC14. Addition of increasing amounts of the SHIP1 peptide caused increasing levels of inhibition of the repair reaction (Figure 2c). The peptide concentration range at which inhibition of MMR was observed was high, suggesting that the Exo1-Msh2 interaction might also involve Exo1 residues outside of the SHIP box that are not present in the short peptides used here; similar affects have been seen in studies that used PIP box peptides to inhibit MMR in vitro32. Peptides with increasing numbers of alanine substitutions showed decreasing levels of inhibition (Figures 2a,2d), although this inhibition was less sensitive to alanine substitutions than inhibition of the Exo1-Msh2 interaction in vivo (Figure 1; also see below). This discrepancy may be caused by the fact that the high peptide concentrations required for inhibition in the in vitro assay makes inhibition less sensitive to loss of conserved SHIP box residues than the Exo1-Msh2 interaction in vivo. In addition, the SHIP1 peptide inhibited the MMR seen in a reconstituted reaction that did not contain RPA (Figure 2e), indicating that the Exo1-Msh2 interaction is still required for MMR even when Exo1 is not inhibited by RPA. We also confirmed that the SHIP1 peptide prevented excision of the mispair-containing substrate in a reaction containing Msh2-Msh6, Exo1, PCNA, RFC, and RPA, but lacking DNA polymerase δ to a level similar to that seen when Exo1 was omitted from the reaction (Figure 2f)14. Taken together, these results suggest that the SHIP box directly mediates the Exo1-Msh2 interaction and that this interaction is required for Exo1-mediated mispair excision in reactions that occur in the absence of Mlh1-Pms1.

Figure 2. SHIP box peptides inhibit Exo1-dependent MMR and mispair-promoted excision in vitro.

A. Sequence of the wild-type SHIP1 peptide and variant peptides in which conserved SHIP box residues were replaced with alanine. B. Diagram of the mispair-containing substrate with a 5’ nick. C. Titration of the wild-type SHIP1 peptide into an in vitro MMR reaction which contains Msh2-Msh6, Exo1, RPA, RFC, PCNA, and DNA polymerase δ. Repair is assayed by restoration of a PstI restriction site at the mispair, and substrates are digested with PstI and ScaI before running on an 1% agarose gel. D. Comparison of the inhibition of the in vitro MMR reaction by the presence of the wild-type SHIP1 peptide, or the presence of peptides containing alanine substitutions. The molar ratio of peptide to Msh2-Msh6 was 1000:1. E. Comparison of the inhibition of the in vitro MMR reaction containing or lacking RPA as indicated by the SHIP1 peptide. For peptide-containing lanes, the molar ratio of peptide to Msh2-Msh6 was 1000:1. F. A mispair-promoted excision reaction of the substrate in a reaction containing Msh2-Msh6 and Exo1 (unless otherwise noted). For peptide-containing lanes, the molar ratio of peptide to Msh2-Msh6 was 1000:1. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of 3 times, although only 1 representative experiment is shown.

Exo1 MIP and SHIP boxes are redundant in Exo1-dependent MMR.

We tested the requirement for the MIP and SHIP motifs for Exo1-dependent MMR in vivo using S. cerevisiae strains containing either the pol30-K217E or pms1-A99V (previously called pms1-A130V) mutations, which eliminate the Exo1-independent MMR pathway20,24. An ARS CEN plasmid expressing wild-type EXO1 under its native promoter complemented the mutator phenotype of both the exo1Δ pol30-K217E and exo1Δ pms1-A99V double mutant strains as measured by patch tests, whereas plasmids encoding the SHIP- and MIP- double mutated Exo1, the nuclease-deficient Exo1 (Exo1-D173A), or the empty vector did not (Supplementary Figure 2a). We next measured mutation rates of strains with different combinations of integrated exo1 mutations that disrupted the Exo1 MIP box (exo1-F447A,F448A), the first SHIP box (exo1-F582A,Y584A), or the second SHIP box (exo1-F697A,Y699A) at the EXO1 locus that also contained the pol30-K217E mutation (Table 1). Simultaneous mutation of the MIP box and both SHIP boxes caused a mutation rate equivalent to that of the exo1Δ pol30-K217E double mutant or an msh2Δ single mutant (Table 1). Mutation of either SHIP box independently resulted in mutation rates that were not significantly different from that of the pol30-K217E single mutant while mutation of both SHIP boxes, the MIP box alone, or the MIP box an individual SHIP box caused mutation rates that were intermediate between that of the pol30-K217E single mutant and the exo1Δ pol30-K217E double mutant. In contrast, EXO1 plasmids containing different combinations of MIP and SHIP box mutations suppressed the synthetic lethality between the rad27Δ and exo1Δ mutations12, which was similar to a wild-type EXO1 plasmid but not an EXO1 plasmid containing the nuclease-deficient exo1-D173A mutation that does not suppress this synthetic lethality (Supplementary Figure 2b). Taken together, these results argue that: 1) Exo1 recruitment by either Msh2 or Mlh1 is required for Exo1-dependent MMR but not for other roles for Exo1; 2) Exo1 recruitment to MMR reactions by Msh2 and Mlh1 is redundant; and 3) the Exo1 SHIP boxes are redundant with each other.

Table 1.

Mutation rates caused by Exo1 MIP and SHIP mutations at the Exo1 genomic locus

| RDKY number |

Relevant Genotype |

Thr+ | Lys+ | CanR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDKY5964 | Wild-type* | 2.26 [1.22–3.30] × 10−9 (1) | 1.01 [0.67–1.86] × 10−8 (1) | 5.65 [3.56–8.53] × 10−8 (1) |

| RDKY3688 | msh2Δ* | 3.24 [2.60–4.33] × 10−6 (1,433) | 9.38 [7.30–14.0] × 10−5 (9,287) | 2.98 [2.43–4.38] × 10−6 (53) |

| RDKY7884 | exo1Δ* | 4.93 [3.04–10.2] × 10−9 (2) | 4.02 [2.67–7.34] × 10−8 (4) | 2.58 [1.52–11.2] × 10−7 (5) |

| RDKY8075 | pol30-K217E* | 9.27 [7.47–18.0] × 10−9 (4) | 3.26 [2.39–5.33] × 10−7 (32) | 3.99 [3.43–5.98] × 10−7 (7) |

| RDKY8077 | pol30-K217E exo1Δ* | 1.66 [1.39–3.54] × 10−6 (735) | 4.04 [2.80–5.94] × 10−5 (4,000) | 4.76 [3.53–7.48] × 10−6 (84) |

| RDKY9358 |

pol30-K217E

exo1-MIP |

5.78 [4.56–10.9] × 10−8 (26) | 2.79 [2.16–5.18] × 10−6 (275) | 8.14 [6.64–11.4] × 10−7 (14) |

| RDKY9359 |

pol30-K217E

exo1-SHIP1 |

1.72 [1.42–2.43] × 10−8 (8) | 4.54 [3.48–5.81] × 10−7 (45) | 5.94 [4.74–10.7] × 10−7 (11) |

| RDKY9360 |

pol30-K217E exo1-SHIP2 |

2.08 [1.40–3.66] × 10−8 (9) | 5.78 [3.24–13.2] × 10−7 (57) | 6.59 [3.51–10.4] × 10−7 (12) |

| RDKY9361 |

pol30-K217E

exo1-SHIP1, SHIP2 |

5.06 [2.66–22.1] × 10−8 (22) | 1.37 [0.84–16.1] × 10−6 (135) | 1.18 [0.56–2.47] × 10−6 (21) |

| RDKY9362 |

pol30-K217E

exo1-MIP, SHIP1 |

3.23 [2.40–4.94] × 10−7 (143) | 7.89 [5.68–10.2] × 10−6 (778) | 2.15 [1.12–5.08] × 10−6 (38) |

| RDKY9363 |

pol30-K217E exo1-MIP, SHIP2 |

5.59 [2.31–9.97] × 10−7 (247) | 1.21 [0.53–2.12] × 10−5 (1195) | 1.60 [0.79–2.52] × 10−6 (28) |

| RDKY9364 |

pol30-K217E exo1-MIP, SHIP1, SHIP2 |

1.33 [1.12–1.88] × 10−6 (589) | 4.10 [3.32–5.40] × 10−5 (4,043) | 2.88 [2.46–4.68] × 10−6 (51) |

Reported rates are the median rates with 95% confidence interval in square brackets. Fold increase in mutation rate over the wild-type strain rate (RDKY5964) is listed in parenthesis. Total loss of mismatch repair is represented by msh2Δ (RKDY3688). n=14 independent cultures from two independently derived isolates.

measured in Goellner et. al. Molecular Cell 2011

An Exo1-Msh6 fusion protein partially overcomes the requirement for Exo1 recruitment motifs.

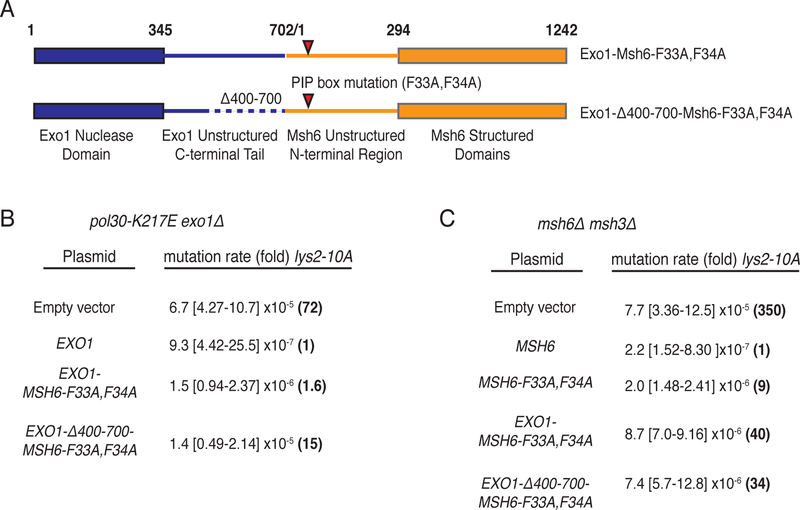

If the Exo1 MIP and SHIP boxes primarily mediate Exo1 recruitment to sites of MMR, constitutive recruitment of Exo1 might bypass the need for these motifs. A fusion of the unstructured C-terminus of Exo1 to the unstructured N-terminus of Msh6 containing a mutated Msh6-PCNA interaction site22 almost completely complemented the mutator phenotype of an exo1Δ pol30-K217E double mutant strain (Exo1-Msh6-F33A,F34A Figure 3a and 3b). A internally truncated version of this fusion that eliminated the Exo1 MIP and SHIP boxes also complemented the mutator phenotype of the exo1Δ pol30-K217E double mutant strain, although not to the same extent as the Exo1-Msh6-F33A,F34A construct (Exo1-Δ400–700-Msh6-F33A,F34A; Figures 3a and 3b). In contrast, expression of Exo1 lacking the MIP and SHIP boxes resulted in a mutator phenotype similar to that of the exo1Δ pol30-K217E double mutant (Supplementary Figure 2a; last row). Both the Exo1-Msh6-F33A,F34A and Exo1-Δ400–700-Msh6-F33A,F34A fusions could largely complement the frameshift mutation reversion phenotype of an msh6Δ msh3Δ double mutant, indicating these fusions are largely retain Msh6 function (Figure 3c). The small Msh6 defect observed is consistent with the observation that the two fusions do not completely complement the Exo1 defect of the exo1Δ pol30-K217E double mutant strain. Thus, constitutive recruitment of Exo1 by fusion to Msh6 supports MMR and can at least partially substitute for SHIP and MIP box-mediated recruitment.

Figure 3. An Exo1-Msh6 fusion can bypass the requirement for MIP and SHIP box motifs.

A. Diagram of the fusions between full length Exo1 and the Msh6 PIP box (F33A,F34A) mutant and the C-terminally truncated Exo1-Δ400–700 and the Msh6 PIP box mutant. B. Mutation rates demonstrate that expression of wild-type Exo1 and both Exo1-Msh6 fusions complement the mutator phenotype of the exo1Δ pol30-K217E double mutant strain (RDKY8077) as measured using the lys2–10A frameshift reversion assay. Note that complementation by the EXO1-Δ400–700-MSH6-F33A,F34A is less efficient than the fusion encoding the full length Exo1 protein. C. Mutation rates demonstrate that both Exo1-Msh6 fusions complement the mutator phenotype of the msh6Δ msh3Δ double mutant; however, the level of complementation is modestly reduced relative to wild-type MSH6 and msh6-F33A,F34A. In all experiments, mutation rates were determined by fluctuation analysis using 2 independently derived strains and 14 cultures; 95% confidence intervals are provided in the square brackets and the fold-increase in mutation rates relative to the complemented control strain are provided in parenthesis.

An msh2 mutation that disrupts Exo1-dependent MMR also disrupts the Msh2-Exo1 interaction.

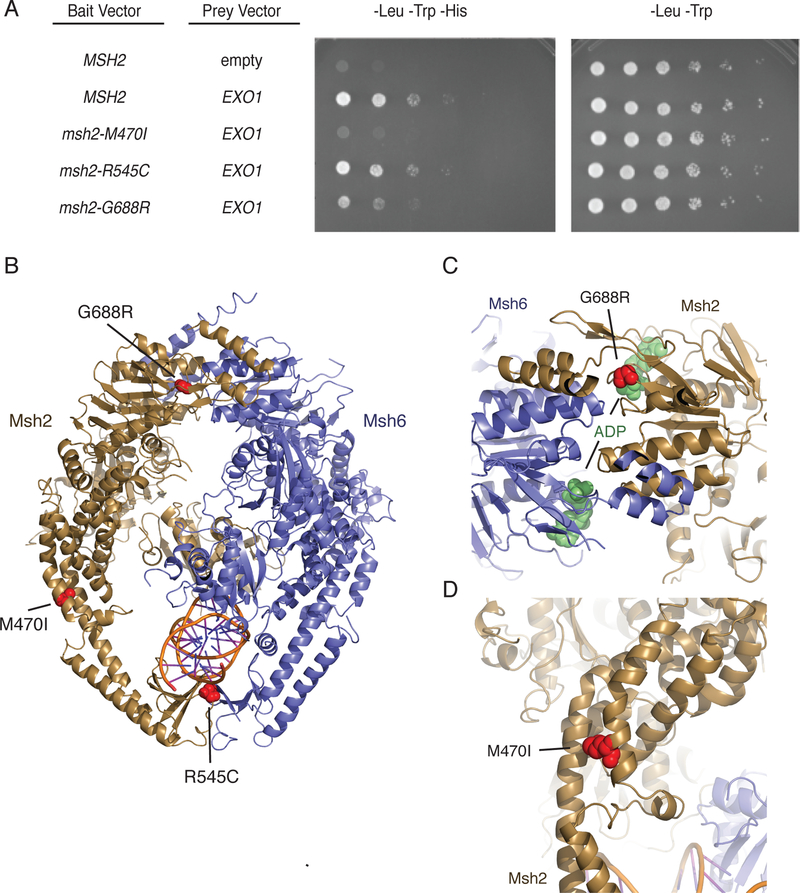

A previous genome-wide screen for mutator mutations that specifically disrupted Exo1-dependent MMR identified exo1 nuclease mutants20, exo1 truncation mutations eliminating the MIP and SHIP boxes20, mlh1 mutations affecting MIP box peptide binding20,29, and three msh2 missense mutations: msh2-M470I, msh2-R545C (previously reported as msh2-R545K), and msh2-G688R20. We therefore tested if these msh2 mutations disrupted the Exo1-Msh2 interaction by yeast two-hybrid analysis. The msh2-R545C mutation did not disrupt the Exo1-Msh2 interaction (Figure 4a). The msh2-G688R mutation that affects the ATPase domain33, which is buried within the Msh2-Msh6 heterodimer (Figure 4b,c) and could alter ATP-driven conformational changes required for Exo1 recruitment, caused a reduced but easily detectable level of Msh2-Exo1 interaction (Figure 4a). In contrast, the msh2-M470I mutation that affects a residue whose human equivalent is involved in the packing of the helices that surround the DNA (Figure 4b,d)33 and through steric interactions likely affects surface-exposed residues that could mediate SHIP box binding through steric interactions, resulted in no detectable Msh2-Exo1 interaction (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. The msh2-M470I mutation disrupts the Msh2-Exo1 interaction.

A. Yeast two-hybrid analysis of wild-type EXO1 prey vectors with bait vectors carrying MSH2, msh2-M470I, msh2-R545C, and msh2-G688R reveal that Msh2-G688R has a partial Exo1 binding defect and that Msh2-M470I is defective for Exo1 binding. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of 4 times. B. The positions of the S. cerevisiae M470I, R545C, and G688R amino acid substitutions were modelled onto the human Msh2-Msh6 structure (PDB id 2o8b, ref. 33). Msh2 is displayed in dark yellow ribbons, Msh6 is displayed in blue cartoon, and DNA is displayed as a cartoon. Positions of the amino acid substitutions are shown as red spheres. C. The G688R amino acid substitution affects a conserved glycine residue present in a loop adjacent to the Msh2 nucleotide-binding site that contains an ADP molecule (green spheres) in the human Msh2-Msh6 structure. D. The M470I amino acid substitution affects a conserved methionine present at a site where the helices in the helical arms that surround the DNA substrate pack against each other. The site is also N-terminal to a loop that interrupts these helices and might be a site of flexibility in the protein in the absence of DNA as revealed by DNA-free structures of Thermus aquaticus MutS60.

The SHIP box motif allows identification of two novel Msh2 interacting proteins.

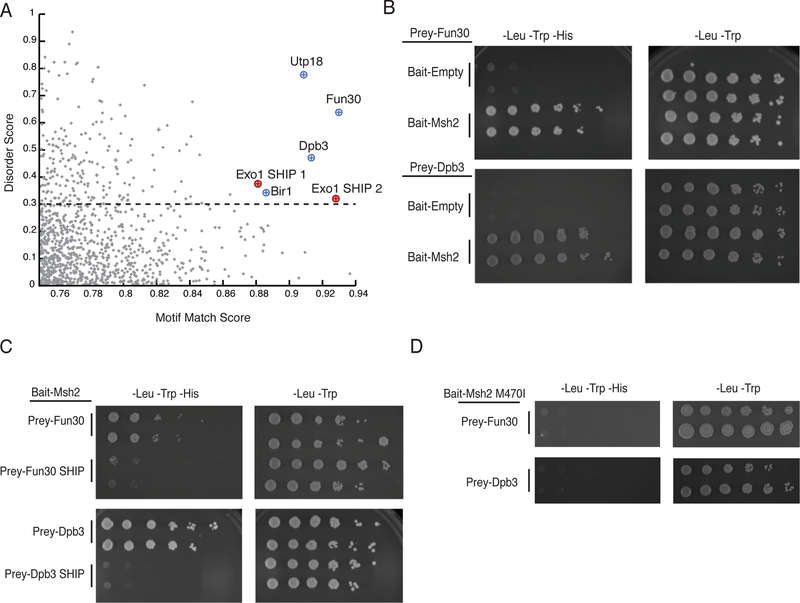

We investigated whether an Exo1-like SHIP box motif was present in the unstructured regions of other nuclear S. cerevisiae proteins. We constructed a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM, 34) using the sequences of 567 SHIP1 and SHIP2 motifs from fungal Exo1 sequences (Figure 1c) and scored the similarity of all peptides encoded in the S. cerevisiae S288c genome to the SHIP box consensus sequence. We found that 2,732 peptides had moderate or high scores (score > 0.75). We then filtered out peptides from proteins that on the basis of previous studies do not localize to the nucleus25,35–39, resulting in 1,745 peptides. We then calculated a long-range disorder score with IUPRED40. Disordered peptides from nuclear proteins with the high motif-matching scores included both Exo1 SHIP boxes and potential SHIP boxes in Utp18 (21-LLAKFVF-27), Fun30 (45-LRSRFTF-51), Dpb3 (170-LLSRFQY-176), and Bir1 (151-NLRKFTF-157) (Figure 5a; Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Data Set 2). By yeast two-hybrid analysis, Bir1 did not show an interaction with Msh2, whereas the Utp18 prey vector auto-activated the reporter in absence of the bait vector making it impossible to study a possible Msh2-Utp18 interaction using this assay (Supplementary Figure 4a). In contrast, Msh2 interacted with both Fun30, a Snf2-family ATPase involved in chromatin remodelling and the resection of double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs)41–43, and Dpb3, which is a subunit of DNA polymerase ε44 (Figure 5b). Mutations eliminating the conserved aromatic residues of the SHIP boxes in Fun30 (F49A,F51A) and Dpb3 (F174A,Y176A) eliminated the interaction between these proteins and Msh2 (Figure 5c). In addition, the msh2-M470I mutation eliminated the Msh2-Fun30 and Msh2-Dpb3 interactions in the two-hybrid interaction assay (Figure 5d), like its effect on the Msh2-Exo1 interaction (Figure 4a). The Exo1 and Fun30 SHIP boxes were conserved in the Saccharomycetaceae fungi, whereas the Dpb3 SHIP box was only present in species that were closely related to S. cerevisiae (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 5. Bioinformatic identification of putative SHIP box peptides reveals Msh2 interacting proteins.

A. The 1,745 peptides from the nuclear S. cerevisiae proteome with a moderate or good motif matching are plotted against their long-range disorder. Both known Exo1 SHIP boxes are identified. B. Yeast two-hybrid analysis identifies both Fun30 and Dpb3 as Msh2 interacting proteins. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of 4 times. C. Disruption of the putative SHIP boxes in both Fun30 and Dpb3 disrupts the Msh2 interaction as measured by yeast two-hybrid analysis; Prey-Fun30 SHIP and Prey-Dpb3 SHIP constructs contain point mutations replacing the conserved aromatic residues in the SHIP motifs with alanines. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of 4 times. D. Wild-type Fun30 and Dpb3 do not interact with the Msh2-M470I variant as measured by yeast two-hybrid analysis, similar to the effect of the variant on the Msh2-Exo1 interaction. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of 4 times.

Role of Fun30 and Dpb3 in Msh2-mediated functions.

To test the roles of Fun30 and Dpb3 in MMR, we tested the effect of deleting FUN30 and DPB3 on mutation rates in a number of strains: 1) wild-type, 2) an exo1Δ mutant to evaluate defects in Exo1-independent MMR, and 3) a pol30-K217E mutant strain to evaluate defects in Exo1-dependent MMR. Deletion of DPB3 did not cause an increased mutation rate in any of the assay strains (Table 2). The fun30Δ mutation did not cause an increase in mutation rate in either the wild-type or exo1Δ mutant strains but did in pol30-K217E mutant strain (Table 2). Neither deletion caused an increase in the level of mispair- and Msh2-dependent Mlh1-Pms1-GFP foci repair intermediates25 (Supplementary Figure 4b), nor did these deletions affect the Msh2- and Msh6-dependent suppression of HR between imperfect DNA repeats45,46 (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Mutation rates caused by dpb3Δ, fun30Δ and rsc2Δ mutations

| RDKY number |

Relevant Genotype | Thr+ | Lys+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKY5964 | Wild-type* | 2.26 [1.22–3.30] × 10−9 (1) | 1.01 [0.67–1.86] × 10−8 (1) |

| RDKY9371 | dpb3Δ | 4.74 [1.33–189] × 10−9 (2.1) | 1.33 [0.54–2.39] × 10−8 (1.3) |

| RDKY9367 | fun30Δ | 5.3 [0.91–8.71] × 10−9 (2.3) | 2.84 [1.72–5.01] × 10−8 (2.8) |

| RDKY9409 | rsc2Δ | 3.8 [2.61–7.20] × 10−9 (1.7) | 2.74 [0.77–3.47] × 10−8 (2.7) |

| RDKY9410 | fun30Δ rsc2Δ | 9.83 [4.25–64.3] × 10−9 (4.3) | 5.27 [3.23–14.0] × 10−8 (5.2) |

| RDKY7884 | exo1Δ* | 4.93 [3.04–10.2] × 10−9 (2.2) | 4.02 [2.67–7.34] × 10−8 (4) |

| RDKY9372 | exo1Δ dpb3Δ | 7.53 [3.09–12.5] × 10−9 (1.5) | 5.14 [4.74–6.36] × 10−8 (5) |

| RDKY9368 | exo1Δ fun30Δ | 1.06 [0.62–9.38] × 10−8 (4.7) | 7.28 [4.51–23.7] × 10−8 (7.2) |

| RDKY9411 | exo1Δ rsc2Δ | 3.38 [2.34–7.88] × 10−8 (15) | 1.05 [0.8–1.23] × 10−6 (100) |

| RDKY9412 | exo1Δ fun30Δ rsc2Δ | 1.96 [1.16–4.00] × 10−8 (8.7) | 2.79 [1.78–4.08] × 10−7 (28) |

| RDKY8075 | pol30-K217E* | 9.27 [7.47–18.0] × 10−9 (4) | 3.26 [2.39–5.33] × 10−7 (32) |

| RDKY9373 | pol30-K217E dpb3Δ | 1.54 [0.98–2.31] × 10−8 (6.8) | 4.89 [3.75– 9.84] × 10−7 (48) |

| RDKY9369 | pol30-K217E fun30Δ | 4.39 [3.02–6.01] × 10−8 (19) | 8.34 [6.49–10.7] × 10−7 (83) |

| RDKY9413 | pol30-K217E rsc2Δ | 7.46 [3.21–25.9] × 10−8 (33) | 3.66 [2.85–6.63] × 10−6 (362) |

| RDKY9414 | pol30-K217E fun30Δrsc2Δ | 1.36 [0.97–6.18] × 10−7 (60) | 3.38 [1.54–4.10] × 10−6 (335) |

Reported rates are the median rates with 95% confidence interval in square brackets. Fold increase in mutation rate is listed in parenthesis as compared to the wild-type strain. ). n=14 independent cultures from two independently derived isolates.

measured in Goellner et. al. Molecular Cell 2014

Role of Fun30 and Rsc2 in MMR.

These results suggest a partial role for Fun30 in Exo1-dependent MMR, which is consistent with the role of Fun30 during resection of DSBs42. In addition to Fun30, both the Rsc and Ino80 complexes have been implicated in resection; however, the role of the Ino80 complex, if any, was minor42. We therefore tested the effect of an rsc2Δ mutation on mutation rates alone and in combination with a fun30Δ mutation in wild-type, exo1Δ and pol30-K217E strains (Table 2). The rsc2Δ mutation did not increase the mutation rates of the wild-type or fun30Δ single mutant strain. Deletion of RSC2 increased the mutation rate in an exo1Δ mutant, but the exo1Δ fun30Δ rsc2Δ triple mutant had a lower mutation rate than the exo1Δ rsc2Δ double mutant (the reduction in the hom3–10 reversion assay was significant in Mann-Whitney tests, p = 0.006, but not using 95% confidence intervals, whereas the reduction in the lys2-A10 reversion assay was significant using 95% confidence intervals). In the pol30-K217E strain, deletion of RSC2 caused a significant increase in mutation rate by 95% confidence intervals. The mutation rate of the pol30-K217E fun30Δ rsc2Δ triple mutant was the same as that of the pol30-K217E rsc2Δ double mutant and was higher than that of the pol30-K217E fun30Δ double mutant, and was equivalent to that expected for a loss of approximately 5% of MMR. We also performed a selected analysis of the effects of an arp8Δ mutation that causes a defect in the Ino80 complex and found that the arp8Δ mutation did not increase the mutation rates of the wild-type, fun30Δ and rsc2Δ single mutant and pol30-K217E fun30Δ double mutant strains (Supplementary Table 2). These results suggest Fun30 plays a small role in Exo1-dependent MMR, that the Rsc complex plays a role in both Exo1-dependent and Exo1-independent MMR and that the Rsc complex is more important than Fun30.

SHIP box motifs are present in human proteins that interact with MSH2.

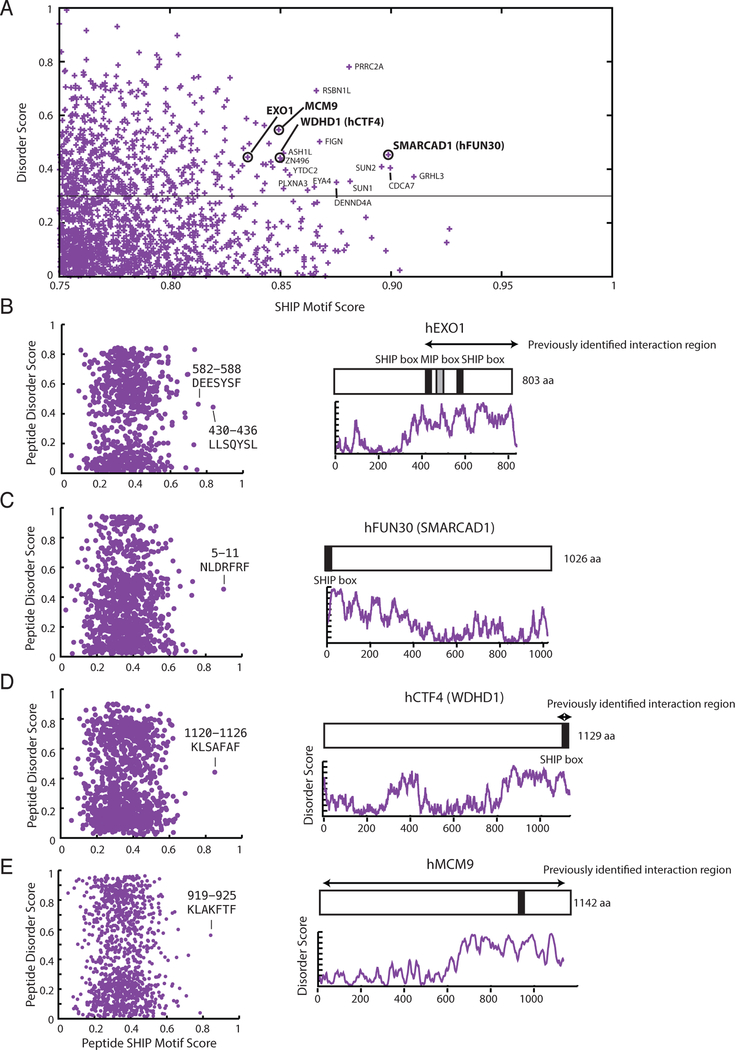

Since both S. cerevisiae and human Msh2 interact with S. cerevisiae Exo112, we used the SHIP box PSSM derived from fungal Exo1 sequences to search for SHIP boxes within the human nuclear proteome. Following the method developed for analysing S. cerevisiae, the SHIP box analysis resulted in 1,720 peptides (Figure 6a; Supplementary Data Set 3). The region previously identified for the interaction between S. cerevisiae Msh2 and human EXO1 contained SHIP box like peptides27. In addition, the human homolog of S. cerevisiae Fun30, SMARCAD1, also contains a SHIP box-like peptide (Supplementary Figure 3b), suggesting evolutionary conservation of the Msh2-Fun30/MSH2-SMARCAD1 interaction. We also found a SHIP box in WDHD1, which is a replication fork component and the homolog of S. cerevisiae Ctf447–50; however, the SHIP box is only conserved in animal WDHD1/Ctf4 homologs (Supplementary Figure 6). WDHD1 is a recently identified MSH2-interacting protein, and previous analysis both localized the interaction to the SHIP box region and found that patient-derived mutations affecting the SHIP box disrupted the interaction; however, as the WDHD1-MSH2 interaction was the only interaction characterized in that study, the authors did not draw any conclusions about MSH2-interaction motifs51. Another known MSH2-interacting protein, MCM952, also contains a putative SHIP box in its unstructured C-terminal tail, which is conserved among groups closely related to animals (Supplementary Figure 6); however, no experiments have yet been performed investigating whether the MCM9-MSH2 interaction is mediated by this SHIP box.

Figure 6. Bioinformatic identification of putative human SHIP box peptides reveals known and potentially conserved MSH2 interacting proteins.

A. The 1,720 peptides from the nuclear human proteome with a moderate or good motif matching are plotted against their long-range disorder. B, C, D, E. (Left) Two-dimensional plot of each 7mer peptide in the proteins plotted with the SHIP peptide motif score generated with the PSSM along the x-axis and the peptide disorder score generated using IUPRED 40 along the y-axis. Peptides with strong scores are labelled. (Right) Diagram of the proteins with the position of the putative SHIP boxes displayed as black bars over a plot of the IUPRED long-range disorder score. Most putative SHIP boxes are present in extended unstructured regions at the N- or C-termini of the proteins. Known human MSH2 interaction regions are displayed using arrows.

Discussion

We found that Exo1 contains two novel motifs, termed here the SHIP boxes, that account for the interaction between Msh2 and the Exo1 C-terminus12. The two SHIP boxes and the MIP box are required for Exo1-dependent MMR but are redundant with each other, which explains why previous studies were unable to clearly demonstrate a major role of the Exo1 MIP box in MMR30. An Exo1-recruitment role for these motifs is consistent with the fact that an Exo1-Msh6 fusion protein lacking these motifs can complement the deletion of EXO1 in MMR. SHIP peptide inhibition of mispair-promoted excision and MMR reactions that are dependent on Msh2-Msh6 and Exo1 indicates that the Exo1 SHIP box directly interacts with Msh2. The fact that the msh2-G688R and msh2-M470I mutations partially or completely inhibited the Exo1-Msh2 interaction is consistent with the hypothesis that the SHIP box binds near Msh2 M470 in a manner dependent upon ATP-induced conformational changes. Overall, our results support a model in which the MIP and SHIP boxes and the Exo1-Mlh1 and Exo1-Msh2 interactions recruit Exo1 to mismatch repair reactions.

Msh2-Msh6 stimulates 5’ nick-directed mispair excision by Exo1 in vitro13,14 In this reaction, Msh2-Msh6 and the formation of Msh2-Msh6 sliding clamps have been proposed to overcome inhibition of Exo1 by RPA, which binds to the single-stranded DNA generated by Exo113,53,54. The role of the Msh2-Exo1 interaction has been suggested to support re-recruitment of displaced Exo1 to the substrate13,53,54; however, the available data could not eliminate the possibility that Exo1 acts as a component of the Msh2-Msh6 sliding clamp. By using SHIP box containing peptides, we found that the Msh2-Exo1 interaction was required in reactions with substrates with a nick 5’ to the mispair for both mispair excision and complete MMR reactions even in the absence of RPA. Thus, the Exo1-Msh2 interaction plays a role other than just overcoming inhibition by RPA. Moreover, constitutive tethering of Exo1 to Msh6 partially supported MMR in vivo in the absence of the Msh2-Exo1 and Mlh1-Exo1 interactions. Taken together, these observations suggest that Exo1 may normally function during MMR while tethered to Msh2-Msh6 (and Msh2-Msh3) sliding clamps through the Msh2-Exo1 interaction. This idea is consistent with results of single molecule biochemistry experiments demonstrating that loading of Msh2-Msh6 clamps stimulates excision by Exo153.

Although the SHIP boxes appear to mediate recruitment of Exo1 by Msh2, the role for the Exo1-Mlh1 interaction is less clear, as Mlh1-Pms1 (Mlh1-Pms2 in humans) is not required for reconstituted 5’ nick-directed MMR reactions in vitro16,17, whereas conflicting requirements have been reported for Mlh1-Pms2 in MMR reactions catalyzed by human cell extracts55,56. A possible role of Mlh1-Pms2 in promoting specific termination of Exo1-mediated excision is unclear13,56, and we observe specific termination of excision even in the absence of Mlh1-Pms1 (Figure 2f). The genetic redundancy between the SHIP and MIP boxes suggests that the Exo1-Mlh1 interaction promotes mispair excision by Exo1 either by: 1) independent recruitment of Exo1 by Msh2 and Mlh1; or 2) formation of a complex containing Exo1, Msh2-Msh6 and Mlh1-Pms1 during MMR. Our identification of the two Exo1 SHIP boxes, their redundancy with the Exo1 MIP box, and the potential interaction site on Msh2 should now make it possible to better test hypotheses about the role of the Exo1-Mlh1 interaction in MMR.

By screening and validating the S. cerevisiae proteome for Msh2-binding SHIP boxes, we identified two Msh2-interacting proteins, Fun30 and Dpb3. We also identified three human proteins likely to contain functional SHIP boxes: SMARCAD1 (homolog of S. cerevisiae Fun30), WDHD1 (homolog of S. cerevisiae Ctf4) and MCM9, the latter two of which have been previously demonstrated to bind human MSH251,52. The fun30Δ mutation caused a small partial defect in Exo1-dependent MMR, consistent with previous results showing that fun30Δ caused a modest defect in 5’ resection during DSB repair42,43. In addition, consistent with this prior work on DSB resection, we found that a rsc2Δ mutation caused a small partial defect in Exo1-independent MMR and a larger defect in Exo1-dependent MMR with the magnitude of the MMR defects observed, suggesting that the Rsc complex plays a greater role in MMR than Fun30. The largest increases in mutation rates observed in the different fun30Δ and rsc2Δ mutant strains tested was equivalent to that expected for a loss of approximately 5% of MMR. The partial defects in Exo1-dependent and Exo1-independent MMR caused by FUN30 and RSC2 deletions could reflect: 1) a limited role of the Fun30 and the Rsc complex in short range resection that likely occurs in MMR; 2) redundancy of Fun30 and the Rsc complex with other chromatin remodelling complexes during MMR; or, 3) redundancy with other processes that can remove nucleosomes such as the interplay between nucleosome segregation and de novo nucleosome assembly at DNA replication forks 57 given that MMR is coupled to DNA replication25,58 or the ability of Msh2-Msh6 to displace loosely associated nucleosomes59. In contrast, deletion of DPB3 did not seem to cause a defect in either Exo1-independent or Exo1-dependent MMR in the assays used. This result suggests that either the Msh2-Dpb3 interaction functions in a different aspect of DNA metabolism or reflects a function in MMR, possibly a redundant function, that cannot be easily detected using genetic assays; one possible function is recruitment of DNA polymerase ε to the gap-filling reaction during MMR, something that would be redundant with recruitment of DNA polymerase δ.

Online Methods

Strains and plasmids.

S. cerevisiae strains were grown in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone and 2% dextrose) or in the appropriate synthetic dropout media (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% dextrose, and amino acid dropout mix at the concentration recommended by the manufacturer (US Biological) at 30°C. All transformations with plasmids or PCR-based deletion cassettes were performed using standard lithium acetate transformation protocols.

All S. cerevisiae strains in this study were derived in the S288C strain background using standard gene deletion and pop-in, pop-out methods (Supplementary Table 3). EXO1 point mutations were integrated into the RDKY8075 genome by standard pop-in/pop-out of an integrating pRS306 vector containing the appropriate exo1 mutation. Integration was confirmed by sequencing the entire EXO1 gene. Plasmid complementation experiments utilized ARS CEN plasmids from the pRS series61 in which the relevant gene was expressed under control of its native promoter (Supplementary Table 4).

Site directed mutagenesis.

Site directed mutagenesis was carried out using the GeneArt Site Directed Mutagenesis kit (Invitrogen) as described in the manufacturer instructions. The presence of the correct mutation and the absence of other mutations were confirmed by sequencing the complete target gene.

Two-hybrid assay.

Plasmids expressing fusion proteins for yeast two-hybrid analysis were generated by Gateway cloning (Invitrogen) the gene of interest without its start codon into either the gateway modified bait vector, pBTM116 containing the LexA DNA binding domain, or prey vector, pACT2 containing the GAL4 activation domain (Supplementary Table 4). Bait (TRP1) and prey (LEU2) plasmids were co-transformed into the L40 S. cerevisiae reporter strain (Supplementary Table 3), in which a positive interaction of the bait and prey fusion proteins results in expression of HIS3 and hence complementation of the his3 mutation in the L40 strain 62. Colonies were grown up overnight in -Leu -Trp selective media to maintain plasmid selection and a 10-fold serial dilution series was plated on -Leu -Trp control media and -Leu -Trp -His selective media to assay for two-hybrid interactions.

Mutation rate analysis.

Mutator phenotypes were evaluated using the hom3–10 and lys2–10A frameshift reversion assays and the CAN1 gene inactivation assay20,25. Qualitative analysis was done by patching colonies onto YPD plates and replica plating onto the appropriate selective media (-Thr, -Lys or -Arg + 60mg/L canavanine, respectively) for analysis of papillae growth. Mutation rates were determined by fluctuation analysis using a minimum of 2 independently derived strains and 14 or more independent cultures; comparisons of mutation rates were evaluated using 95% confidence intervals or by Mann-Whitney 2-tailed tests20,25.

Heteroduplex rejection assay.

The rates of recombination between sequences of 100% or 91% identity were measured as previously described using strains containing inverted repeat recombination assays 45,46. Independent colonies were cut out from YPD plates and grown for two days in YEPGG media (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glycerol, 4% galactose). Recombination rates were then measured by fluctuation analysis using a minimum of 2 independently derived strains and 14 independent cultures by plating the cultures on either complete synthetic media supplemented with 2% glycerol and 4% galactose or -His dropout media supplemented with 2% glycerol and 4% galactose to detect His+ recombinants.

SHIP box peptides.

SHIP box peptides were synthesized by BioMatik at > 95% purity and were provided as a TFA salt. All peptides were resuspended in 100% DMSO and stored at −80 C. In total, four peptides were synthesized: SHIP1-WT (GSSQRSISGCTKVLQKFRYSSS); SHIP-AA (GSSQRSISGCTKVLQKARASSS); SHIP-3A (GSSQRSISGCTKVAQKARASSS); and SHIP-4A (GSSQRSISGCTKVAQAARASSS).

Protein Purification.

Proteins were purified according to standard protocols as previously described for Exo114,15, Mlh1-Pms123,63, Msh2-Msh622,64, PCNA14,65, DNA polymerase δ66, RFC-Δ1N67, and RPA68 and were greater than 95% pure as determined by SDS-PAGE. All of the protein preparations used were previously used in other published studies14,15,18,24.

In vitro MMR assay.

The in vitro MMR repair assay was performed essentially as described14,15. 100 ng of circular DNA substrate containing a +T mispair disrupting a PstI site and a NaeI nick 5’ of the mispair was used as substrate, and the final reaction contained 33 mM Tris pH7.6, 75mM KCl, 2.5 mM ATP, 1.66 mM glutathione, 8.3 mM MgCl2, 80 μg/mL BSA, and 200 μM of each dNTP, 290 fmol PCNA, 220 fmol RFC-Δ1N, 390 fmol Msh2-Msh6, 20 fmol DNA polymerase δ, 1.05 fmol Exo1, and 1800 fmol RPA in a 10 μL volume. Reactions containing SHIP peptide contained peptides at a final concentration of 39 μM (1000:1 molar ratio SHIP peptide to Msh2-Msh6) unless indicated otherwise. Where necessary, proteins were diluted in a buffer consisting of 7.5 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.5 mg/mL BSA prior to addition to the reactions. For experiments analyzing peptide-containing reactions, a buffer portion of the reactions containing the substrate DNA was set up separately and then mixed with a protein mixture that contained all the proteins, including the SHIP peptides, where indicated, except Msh2-Msh6. Then the Msh2-Msh6 was added and the reactions were incubated 2 hours at 30 C. The reactions were then stopped by addition of EDTA, Proteinase K (Sigma), and glycogen (Thermo Scientific) to final concentrations of 21 mM, 24 μg/mL, and 13.4 μg/mL, respectively, followed by incubation for 30 minutes at 55°C. Reactions were extracted with phenol, and the DNA substrate was precipitated with ethanol, followed by digestion with PstI and ScaI. Digested DNA substrate was subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose/1xTAE gel for 45 minutes at 100V. Quantitation was performed with Alpha Imager HP software. All experiments were performed a minimum of 3 times and representative examples of each experiment are presented in Figure 2.

In vitro mispair excision assay.

Excision assays were performed exactly as described for the in vitro MMR repair assay with the following modifications: DNA polymerase δ was omitted from all reactions, and the substrate was not digested by PstI or ScaI before being subjected to gel electrophoresis14. SHIP peptides were added at a final concentration of 39 μM in reactions containing peptide. Exo1 was omitted as indicated.

Microscopy.

Cells were grown in CSM medium to log phase and examined by live imaging using Olympus BX43 fluorescence microscope with a 60x, 1.42 PlanApo N Olympus Oil immersion objective. GFP fluorescence was detected using a Chroma FITC filter set filter set and a Qimaging QIClick CCD camera. Images were captured using Meta Morph Advanced 7.7 imaging software. Figures were prepared in Adobe Photoshop, keeping processing parameters constant within each experiment.

Identification of fungal Exo1 homologs.

The S. cerevisiae Exo1 protein sequence was submitted to the BLASTP server at NCBI69 and run against fungal species with sequenced genomes using the Biopython library70. The protein sequences for blast hits with an e-value less than 10−5 were downloaded. To identify Exo1 homologs among the blast hits, a multiple sequence alignment containing all blast hits and a number of reference S. cerevisiae proteins was generated using MAFFT version 7.127 using the options “--localpair --maxiterate 1000” 71. For fungal species that had a common ancestor with S. cerevisiae after the whole genome duplication event that generated the Exo1/Din7 ohnolog pair72, the reference S. cerevisiae proteins used were Exo1, Din7, Rad2, Rad27, Yen1, and Mkt1. For fungal species that did not undergo the whole genome duplication event, the reference S. cerevisiae proteins used were Exo1, Rad2, Rad27, Yen1 and Mkt1. Using the multiple sequence alignment, a phylogenetic tree was generated using PHYLIP version 3.6673 with the programs PROTDIST and KITSCH. The resulting phylogenetic trees can be described as a series of internal nodes linked by edges to a series of terminal nodes (leaves) that contain protein sequences. Homolog identity was assigned using the co-occurrence of an S. cerevisiae reference protein in the phylogenetic tree. First, a Boolean vector (also called a bit vector) with one value per reference protein was generated for each edge. If a reference protein node was the node that the edge ends in or a node that descended from that node, then the value for that element in the vector was set to true. Thus for the reference protein set [ Exo1, Rad2, Rad27, Yen1, Mkt1 ], the edge that ends in Exo1 would be labelled [ 1, 0, 0, 0, 0 ], and the edge at the top of the phylogenetic tree, which has all reference proteins as descendants, would be labelled [ 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 ]. Second, the terminal nodes were annotated based on the label of the connecting edge. If the label of the connecting edge of a terminal node was comprised of only zeros, then the first non-zero edge associated with the ancestor nodes was used as the label for the terminal node. Third, terminal nodes containing the proteins from the blast hits were assigned a homology to one of the reference protein sequences or “unknown”. For terminal nodes in which only a single element of the Boolean vector is non-zero, the protein sequence at that node was assigned that identity. For the definition of the Boolean vector described above, a terminal node having a label of [ 0, 1, 0, 0, 0 ] would be reported as a homolog of S. cerevisiae Rad2. Terminal nodes with Boolean vectors with multiple non-zero entries, e.g. [ 1, 1, 0, 0, 0 ], were assigned an unknown homology status. Homolog identity assignments are reported in Supplementary Data Set 4. Protein sequences assigned as Exo1 homologs were then aligned using MAFFT. The gene annotation model for some of the Exo1 homologs were modified on the basis of errors that could be identified in the Exo1 multiple sequence alignment. Note that most reannotations affected the more conserved 5’ end of the EXO1 genes where the errors were most obvious. Most reannotations included identification of missing exons (particularly exon 1, which is short in many species), removal of in-frame introns, or removal of adjacent genes that were inappropriately annotated as being part of the EXO1 gene (Supplementary Data Set 5).

Position-specific scoring matrix.

We generated a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM)34 for the SHIP motif using standard techniques. Briefly, we determined the count of each amino acid at each position in the alignment of the SHIP boxes 1 and 2 from fungal Exo1 homologs were determined. A pseudocount of 1 was added to all positions that were zero, and then the counts were converted to a fraction, Fk,j, for each amino acid k at position j. Fk,j, values were then converted to log probabilities (Mk,j) scaled by a background model: Mk,j = log( Fk,j / bk ). The background model was calculated using the frequency of the different amino acids in the proteins encoded by the S. cerevisiae genome. Raw scores (Sraw) for peptides were calculated by adding up all Mk,j values from the PSSM for each amino acid k at position j within the peptide sequence. We scaled the raw scores to be in the range 0 to 1 using the equation: Sscale = (Sraw − Smin ) / (Smax − Smin ), where Smin and Smax are the minimum and maximum scores possible for any peptide scored by the PSSM.

Disorder prediction score.

The long-term disorder prediction score for each position in the proteins were generated using IUPRED40, and the disorder prediction score for each peptide was calculated by averaging the scores for each of the residues in the peptide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nikki Bowen for helpful discussions and providing many of the different protein preparations used in the in vitro MMR assays. This work was supported by NIH grant K99 ES026653 to E.M.G, NIH grant F32 CA210407 to W.J.G., NIH grant R01 GM50006 to R.D.K and support from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research to R.D.K. and C.D.P.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Code availability. The program that implements the algorithm for identifying orthologs from phylogenetic trees, idwtree, is available at http://sourceforge.net/p/idwtree.

Data availability. Source data used for the bioinformatics analysis is available in the supplement as Supplementary Data Sets 1–4. A Life Sciences Reporting Summary is available for this article.

References

- 1.Goellner EM, Putnam CD & Kolodner RD Exonuclease 1-dependent and independent mismatch repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 32, 24–32 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishel R. Mismatch repair. J Biol Chem 290, 26395–403 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z, Pearlman AH & Hsieh P. DNA mismatch repair and the DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst) 38, 94–101 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolodner RD & Marsischky GT Eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair. Curr Opin Genet Dev 9, 89–96 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li GM Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res 18, 85–98 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spies M. & Fishel R. Mismatch repair during homologous and homeologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7, a022657 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch HT, Snyder CL, Shaw TG, Heinen CD & Hitchins MP Milestones of Lynch syndrome: 1895–2015. Nat Rev Cancer 15, 181–94 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durno CA et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of biallelic mismatch repair deficiency (BMMR-D) syndrome. Eur J Cancer 51, 977–83 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterfall JJ & Meltzer PS Avalanching mutations in biallelic mismatch repair deficiency syndrome. Nat Genet 47, 194–6 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane MF et al. Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 57, 808–11 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orans J. et al. Structures of human exonuclease 1 DNA complexes suggest a unified mechanism for nuclease family. Cell 145, 212–23 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tishkoff DX et al. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae EXO1, a gene encoding an exonuclease that interacts with MSH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 7487–92 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genschel J. & Modrich P. Mechanism of 5’-directed excision in human mismatch repair. Mol Cell 12, 1077–86 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowen N. et al. Reconstitution of long and short patch mismatch repair reactions using Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 18472–7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowen N. & Kolodner RD Reconstitution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase epsilon-dependent mismatch repair with purified proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 3607–3612 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y. et al. Reconstitution of 5’-directed human mismatch repair in a purified system. Cell 122, 693–705 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Constantin N, Dzantiev L, Kadyrov FA & Modrich P. Human mismatch repair: reconstitution of a nick-directed bidirectional reaction. J Biol Chem 280, 39752–61 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith CE et al. Activation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease in a Reconstituted Mismatch Repair System. J Biol Chem 290, 21580–90 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadyrov FA, Dzantiev L, Constantin N. & Modrich P. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell 126, 297–308 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin NS, Nguyen MN, Oh S. & Kolodner RD exo1-Dependent mutator mutations: model system for studying functional interactions in mismatch repair. Mol Cell Biol 21, 5142–55 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei K. et al. Inactivation of Exonuclease 1 in mice results in DNA mismatch repair defects, increased cancer susceptibility, and male and female sterility. Genes Dev 17, 603–14 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shell SS, Putnam CD & Kolodner RD The N terminus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh6 is an unstructured tether to PCNA. Mol Cell 26, 565–78 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CE et al. Dominant Mutations in S. cerevisiae PMS1 Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway. PLoS Genet 9, e1003869 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goellner EM et al. PCNA and Msh2-Msh6 activate an Mlh1-Pms1 endonuclease pathway required for Exo1-independent mismatch repair. Mol Cell 55, 291–304 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hombauer H, Campbell CS, Smith CE, Desai A. & Kolodner RD Visualization of eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair reveals distinct recognition and repair intermediates. Cell 147, 1040–53 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadyrov FA et al. A possible mechanism for exonuclease 1-independent eukaryotic mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 8495–500 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmutte C, Sadoff MM, Shim KS, Acharya S. & Fishel R. The interaction of DNA mismatch repair proteins with human exonuclease I. J Biol Chem 276, 33011–8 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dherin C. et al. Characterization of a highly conserved binding site of Mlh1 required for exonuclease I-dependent mismatch repair. Mol Cell Biol 29, 907–18 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gueneau E. et al. Structure of the MutLalpha C-terminal domain reveals how Mlh1 contributes to Pms1 endonuclease site. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20, 461–8 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran PT et al. A mutation in EXO1 defines separable roles in DNA mismatch repair and post-replication repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 6, 1572–83 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gellon L, Werner M. & Boiteux S. Ntg2p, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA N-glycosylase/apurinic or apyrimidinic lyase involved in base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage, interacts with the DNA mismatch repair protein Mlh1p. Identification of a Mlh1p binding motif. J Biol Chem 277, 29963–72 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umar A. et al. Requirement for PCNA in DNA mismatch repair at a step preceding DNA resynthesis. Cell 87, 65–73 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren JJ et al. Structure of the human MutSalpha DNA lesion recognition complex. Mol Cell 26, 579–92 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stormo GD, Schneider TD, Gold L. & Ehrenfeucht A. Use of the ‘Perceptron’ algorithm to distinguish translational initiation sites in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res 10, 2997–3011 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huh WK et al. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425, 686–91 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A. et al. Subcellular localization of the yeast proteome. Genes Dev 16, 707–19 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natter K. et al. The spatial organization of lipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae derived from large scale green fluorescent protein tagging and high resolution microscopy. Mol Cell Proteomics 4, 662–72 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gauci S, Veenhoff LM, Heck AJ & Krijgsveld J. Orthogonal separation techniques for the characterization of the yeast nuclear proteome. J Proteome Res 8, 3451–63 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell CS et al. Mlh2 is an accessory factor for DNA mismatch repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet 10, e1004327 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P. & Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 21, 3433–4 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Awad S, Ryan D, Prochasson P, Owen-Hughes T. & Hassan AH The Snf2 homolog Fun30 acts as a homodimeric ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling enzyme. J Biol Chem 285, 9477–84 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X. et al. The Fun30 nucleosome remodeller promotes resection of DNA double-strand break ends. Nature 489, 576–80 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Costelloe T. et al. The yeast Fun30 and human SMARCAD1 chromatin remodellers promote DNA end resection. Nature 489, 581–4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Araki H. et al. Cloning DPB3, the gene encoding the third subunit of DNA polymerase II of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 19, 4867–72 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Datta A, Adjiri A, New L, Crouse GF & Jinks Robertson S. Mitotic crossovers between diverged sequences are regulated by mismatch repair proteins in Saccaromyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 16, 1085–93 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myung K, Datta A, Chen C. & Kolodner RD SGS1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of BLM and WRN, suppresses genome instability and homeologous recombination. Nat Genet 27, 113–6 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bermudez VP, Farina A, Tappin I. & Hurwitz J. Influence of the human cohesion establishment factor Ctf4/AND-1 on DNA replication. J Biol Chem 285, 9493–505 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gambus A. et al. A key role for Ctf4 in coupling the MCM2–7 helicase to DNA polymerase alpha within the eukaryotic replisome. EMBO J 28, 2992–3004 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Im JS et al. Assembly of the Cdc45-Mcm2–7-GINS complex in human cells requires the Ctf4/And-1, RecQL4, and Mcm10 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 15628–32 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu W. et al. Mcm10 and And-1/CTF4 recruit DNA polymerase alpha to chromatin for initiation of DNA replication. Genes Dev 21, 2288–99 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Z. et al. Proteomic Analysis Reveals a Novel Mutator S (MutS) Partner Involved in Mismatch Repair Pathway. Mol Cell Proteomics 15, 1299–308 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Traver S. et al. MCM9 Is Required for Mammalian DNA Mismatch Repair. Mol Cell 59, 831–9 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeon Y. et al. Dynamic control of strand excision during human DNA mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 3281–6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myler LR et al. Single-molecule imaging reveals the mechanism of Exo1 regulation by single-stranded DNA binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E1170–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li GM & Modrich P. Restoration of mismatch repair to nuclear extracts of H6 colorectal tumor cells by a heterodimer of human MutL homologs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92, 1950–4 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geng H. et al. In vitro studies of DNA mismatch repair proteins. Anal Biochem 413, 179–84 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verreault A. De novo nucleosome assembly: new pieces in an old puzzle. Genes Dev 14, 1430–8 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hombauer H, Srivatsan A, Putnam CD & Kolodner RD Mismatch repair, but not heteroduplex rejection, is temporally coupled to DNA replication. Science 334, 1713–6 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Javaid S. et al. Nucleosome remodeling by hMSH2-hMSH6. Mol Cell 36, 1086–94 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Obmolova G, Ban C, Hsieh P. & Yang W. Crystal structures of mismatch repair protein MutS and its complex with a substrate DNA. Nature 407, 703–10 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods-only References

- 61.Sikorski RS & Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19–27 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yan D. & Jin Y. Regulation of DLK-1 kinase activity by calcium-mediated dissociation from an inhibitory isoform. Neuron 76, 534–48 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hargreaves VV, Shell SS, Mazur DJ, Hess MT & Kolodner RD Interaction between the Msh2 and Msh6 nucleotide-binding sites in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2-Msh6 complex. J Biol Chem 285, 9301–10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Antony E. & Hingorani MM Mismatch recognition-coupled stabilization of Msh2-Msh6 in an ATP-bound state at the initiation of DNA repair. Biochemistry 42, 7682–93 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fien K. & Stillman B. Identification of replication factor C from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a component of the leading-strand DNA replication complex. Mol Cell Biol 12, 155–63 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fortune JM, Stith CM, Kissling GE, Burgers PM & Kunkel TA RPA and PCNA suppress formation of large deletion errors by yeast DNA polymerase delta. Nucleic Acids Res 34, 4335–41 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gomes XV, Gary SL & Burgers PM Overproduction in Escherichia coli and characterization of yeast replication factor C lacking the ligase homology domain. J Biol Chem 275, 14541–9 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakagawa T, Flores-Rozas H. & Kolodner RD The MER3 helicase involved in meiotic crossing over is stimulated by single-stranded DNA-binding proteins and unwinds DNA in the 3’ to 5’ direction. J Biol Chem 276, 31487–93 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jenuth JP The NCBI. Publicly available tools and resources on the Web. Methods Mol Biol 132, 301–12 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cock PJ et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 25, 1422–3 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katoh K. & Standley DM MAFFT: iterative refinement and additional methods. Methods Mol Biol 1079, 131–46 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scannell DR, Butler G. & Wolfe KH Yeast genome evolution--the origin of the species. Yeast 24, 929–42 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Retief JD Phylogenetic analysis using PHYLIP. Methods Mol Biol 132, 243–58 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.