Abstract

Background

Acute otitis media (AOM) and otitis media with effusion (OME) occur primarily in children, whereas acute otitis externa (AOE) occurs with similar frequency in children and adults. Data on the incidence and management of otitis in adults are limited. This study characterizes the incidence, antibiotic management, and outcomes for adults with otitis diagnoses.

Methods

A retrospective cohort of ambulatory adult veterans who presented with acute respiratory tract infection (ARI) diagnoses at 6 VA Medical Centers during 2014–2018 was created. Then, a subcohort of patients with acute otitis diagnoses was developed. Patient visits were categorized with administrative diagnostic codes for ARI (eg, sinusitis, pharyngitis) and otitis (OME, AOM, and AOE). Incidence rates for each diagnosis were calculated. Proportions of otitis visits with antibiotic prescribing, complications, and specialty referral were summarized.

Results

Of 46 634 ARI visits, 3898 (8%) included an otitis diagnosis: OME (22%), AOM (44%), AOE (31%), and multiple otitis diagnoses (3%). Incidence rates were otitis media 4.0 (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.9–4.2) and AOE 2.0 (95% CI, 1.9–2.1) diagnoses per 1000 patient-years. By comparison, the incidence rates for pharyngitis (8.4; 95% CI, 8.2–8.6) and sinusitis (15.2; 95% CI, 14.9–15.5) were higher. Systemic antibiotics were prescribed in 75%, 63%, and 21% of AOM, OME, and AOE visits, respectively. Complications for otitis visits were low irrespective of antibiotic treatment.

Conclusions

Administrative data indicated that otitis media diagnoses in adults were half as common as acute pharyngitis, and the majority received antibiotic treatment, which may be inappropriate. Prospective studies verifying diagnostic accuracy and antibiotic appropriateness are warranted.

Keywords: adult, antibiotic, otitis

Otitis describes inflammation of the ear caused by infectious or noninfectious processes. Acute otitis externa (AOE) is cellulitis of the ear canal skin, which is almost entirely caused by bacteria [1]. Otitis media (OM) concerns the middle ear and is further delineated as otitis media with effusion (OME) or acute otitis media (AOM). Although middle ear effusion is present in both AOM and OME, AOM is differentiated from OME by signs and symptoms of acute infection. In practice differentiating AOM from OME can be subjective, which can result in overtreatment of OME with antibiotics [2]. Collectively, OM is common in children and is the most common reason children receive antibiotics.

OM in adults is thought to be an infrequent diagnosis, and the epidemiology of AOM and OME in adults has rarely been described [3–13]. There are no practice guidelines for AOM in adults; however, antibiotic treatment recommendations are similar to those for children [14]. In children with nonsevere AOM, recommendations are determined by the age of the patient and generally include immediately prescribing antibiotics or observing for resolution of symptoms within 48 to 72 hours before prescribing antibiotics [3]. The preferred antibiotic for AOM is amoxicillin, with amoxicillin/clavulanate reserved for specific circumstances. Prescription of antibiotics is not recommended for the treatment of OME [15]. Differentiation between AOM and OME is vital for this reason. In contrast to OM, AOE occurs with similar frequency in children and adults, and AOE treatment recommendations for adults are well defined [16]. Guidelines recommend pain management and topical antibiotics with or without topical hydrocortisone for most adult and pediatric patients with uncomplicated AOE [17]. Systemic antibiotic therapy is recommended only if the infection extends beyond the external canal or in patients with select comorbidities. It is unknown if clinicians practice in accordance with these recommendations. The purposes of this investigation were to (1) describe the incidence, clinical characteristics, and antibiotic treatment of adult patients with otitis diagnoses and (2) describe the complications and follow-up visits post-treatment.

METHODS

A retrospective cohort of adult veterans who had a diagnosis of an acute respiratory tract infection (ARI) assigned in the outpatient setting between July 2014 and April 2018 in 1 of 6 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) was developed [18]. These facilities were located in North Carolina, Missouri, Kansas, Utah, Idaho, and California. The cohort consisted of patient-visits with otitis, sinusitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, or upper respiratory tract infection without further descriptors (URI-NOS). From this cohort, a subcohort was developed of outpatients presenting specifically with otitis diagnoses. This subcohort was the focus of this study.

Outpatient visits that occurred within emergency department, urgent care clinics, or primary care settings with an International Classification of Diseases 9th (ICD-9) or equivalent International Classification of Diseases 10th (ICD-10) Clinical Modification code for OME, AOM, or AOE were used to identify otitis patient-visits (Supplementary Data). Visits with diagnostic codes that described nonsuppurative or serous otitis media were categorized as OME, whereas visits with diagnostic codes that described suppurative otitis media or otitis media without further clarification (eg, unspecified otitis media) were categorized as AOM [19]. Visits were excluded if they were associated with a separate visit with a diagnostic code for otitis within 12 weeks preceding the index visit; an ears, nose, and throat (ENT) specialty clinic visit or procedure within the same time frame; or diagnostic codes during the index visit for malignant otitis, chronic otitis, Eustachian tube disorders; diagnoses of AOM or OME described as recurrent; or diagnoses of OME where chronicity was not defined. As all cases with an otitis diagnosis in the preceding 12 weeks were excluded, visits with diagnostic codes of AOM where chronicity was not defined were categorized as acute otitis [20]. Exclusion criteria to identify nonotitis ARI patient-visits mirrored criteria for the otitis patient-visits (Supplementary Data). The intent was to create a cohort of visits associated with acute diagnoses while excluding visits associated with chronic diagnoses.

Data elements including diagnoses, patient demographics, prior medical history, co-diagnoses, vital signs and relevant laboratory data on the day of visit, medications prescribed, and outcomes were obtained from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The CDW is a relational database that stores information from >60 domains including demographic, diagnosis, laboratory, and treatment data extracted from the electronic medical record. A prescription for an antibiotic or topical medication was attributed to a visit if it was dispensed from a VA pharmacy within 2 days before or <3 days after the visit [21].

Study end points included the incidence rates for adult otitis diagnostic categories, the proportions of visits in which systemic and/or topical antibiotics were prescribed, otic complications, otitis-related return visits, specialty clinic visits for otitis within 30 days of the index visit. Incidence describes the number of cases per unit of person-time and is an indicator of how commonly a specific diagnosis was identified. Visits were included in the incidence calculation but excluded from the demographic, treatment, and outcomes analyses if they were associated with (1) co-diagnosis of an infectious disease requiring antibiotics or (2) multiple categories of otitis diagnosis during the index visit [21]. For the incidence calculation, the total number of patients with each specific diagnosis was divided by the total number of patient-years identified during the study period. Total patient-years was determined by summing the total number of patient-years, counted as 1 patient-year for each year a patient had a visit within the cohort time frame. The incidence rates of acute sinusitis and pharyngitis diagnoses were included for comparative purposes. Proportions of visits with systemic and/or topical antibiotics prescribed were calculated by dividing the total number of visits with antibiotics prescribed by the total number of visits in each otitis diagnostic category. Outcomes measured within 30 days of the index visit for each otitis diagnostic category included return to clinic visits for otitis, referral to ENT specialists, documented ENT procedures, and otic complications. ENT procedures were defined as an ENT visit associated with a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code describing a procedure involving a part of the head or neck. Otic complications were defined as a visit associated with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnostic code for acute mastoiditis, malignant otitis externa, meningitis, new-onset hearing loss, new-onset facial paralysis, or new-onset gait disturbances (Supplementary Data) [12, 22]. To identify only new-onset hearing loss, facial paralysis, or gait disturbances, visits associated with these outcomes were further investigated to see if the patient had an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnostic code for these diagnoses in the past year. If the patient did, the outcome was not considered new.

Demographics, antibiotics prescribed, and outcomes were compared with descriptive statistics, chi-square test, contingency tables, the Student t test, and analysis of variance with post hoc tests, as indicated. The margin of significance for post hoc tests was determined by the number of groups being compared using a Bonferroni correction [23]. For comparisons between 2 groups, a 2-tailed P value <.05 defined significance, whereas statistical significance for 3 and 4 group comparisons was defined by 2-tailed P values of <.017 and <.008, respectively. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as appropriate.

This research complied with all federal guidelines and Department of Veterans Affairs policies relative to human subjects research and was approved by the institutional review board of each participating VAMC.

RESULTS

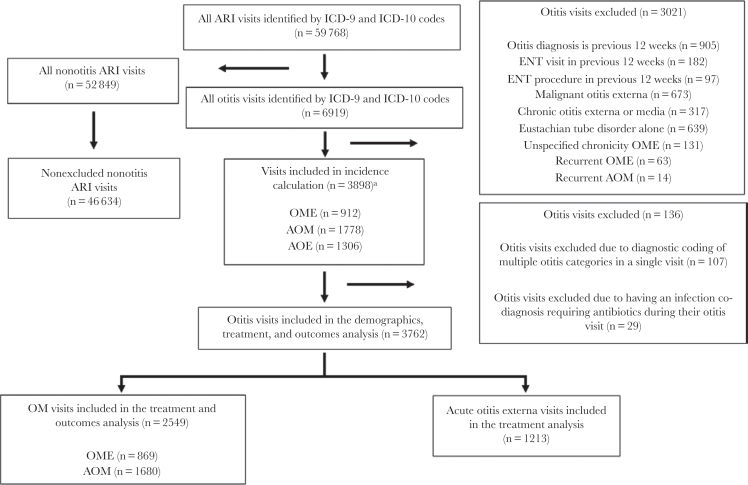

After application of exclusion criteria, a total of 46 634 ARI visits were identified. Of these, 3898 (8%) were otitis visits (Figure 1). Of the 3898 otitis visits included in the incidence calculation, 2690 were visits with codes for OM and 1306 were visits with codes for AOE. There were 97 visits associated with codes for multiple otitis diagnoses. After removing visits with infectious disease co-diagnoses requiring antibiotics and visits with multiple categories of otitis diagnoses, 3762 visits remained: 2549 OM visits and 1213 AOE visits. Patients were mostly male (86%), had normal vital signs, and were seen by a physician in the primary care setting (Table 1). ARI co-diagnosis was common (619/3762 [16%]), but only 117/3762 (3%) visits included a diagnosis of ARI in the previous 30 days. Patients with midlevel providers were more likely to be diagnosed with unspecified otitis media compared with patients seen by physicians (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.71–2.24). The same was true for patient-visits in in urgent care clinics compared with primary care clinics (10.29; 95% CI, 4.9–21.5). Fever was documented in 31/3762 (1%) overall visits and 15/1680 (1%) AOM visits.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for identification of adult acute otitis diagnoses cohort. aVisits included in the incidence calculation could have multiple otitis diagnoses (3989 unique visits, 3996 total otitis diagnoses).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Characteristics

| Characteristic, No. (%) | All Otitis Visits (n = 3762) | Acute Nonsuppurative OM (n = 869) | Acute Suppurative OM (n = 1680) | Acute Otitis Externa (n = 1213) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), yb,c | 56 (16) | 55 (16) | 55 (16) | 58 (16) |

| Male genderb,c | 3249 (86) | 715 (82) | 1433 (85) | 1101 (91) |

| Prior medical history | ||||

| History of allergic rhinitis | 378 (10) | 103 (12) | 162 (10) | 113 (9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 858 (23) | 195 (22) | 372 (22) | 291 (24) |

| Current smokera | 452 (12) | 125 (14) | 178 (11) | 149 (12) |

| History of hearing loss | 307 (8) | 64 (7) | 146 (9) | 97 (8) |

| Immunosuppresseda | 40 (1) | 2 (<1) | 27 (2) | 11 (1) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD)b,c | 2.3 (2.2) | 2.2 (2.1) | 2.2 (2.1) | 2.6 (2.3) |

| History of OM in past year | 171 (5) | 39 (4) | 87 (5) | 45 (4) |

| History of AOE in past yeara,b,c | 134 (4) | 11 (1) | 46 (3) | 77 (6) |

| ARI visit in past 30 d | 117 (3) | 34 (4) | 57 (3) | 26 (2) |

| Visit provider | ||||

| Physiciana,c | 1945 (52) | 513 (59) | 738 (44) | 694 (57) |

| Midlevel providera,c | 1731 (46) | 345 (40) | 894 (53) | 492 (41) |

| Other providersa | 86 (2) | 11 (1) | 48 (3) | 27 (2) |

| Visit location | ||||

| Primary carea,b | 2128 (57) | 435 (50) | 1011 (60) | 682 (56) |

| Emergency departmenta,c | 1418 (38) | 389 (45) | 539 (32) | 490 (40) |

| Urgent carea,c | 73 (2) | 5 (1) | 68 (4) | 0 (<1) |

| Other locations | 143 (4) | 40 (5) | 62 (4) | 41 (3) |

| Vitals and laboratory values on visit date | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure ≤100 mmHg | 57 (2) | 17 (2) | 22 (1) | 18 (1) |

| Temperature ≥100.4°F | 31 (1) | 12 (1) | 15 (1) | 4 (<1) |

| Heart rate ≥100 bpm | 221 (6) | 47 (5) | 104 (6) | 70 (6) |

| WBC ≥12 K/µLd | 27 (1) | 9 (1) | 13 (1) | 5 (<1) |

| Co-diagnoses | ||||

| Acute respiratory tract infectionb,c | 619 (16) | 218 (25) | 353 (21) | 48 (4) |

Immunosuppression was determined by identifying patients with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code signifying immunosuppression in the past year or with filled prescriptions for an immunomodulating medication within a prespecified time window (Supplementary Data). Providers: The physician category included physicians and medical trainees. Midlevels included physician assistants and nurse practitioners. Other providers included nurses and pharmacists. Other visit locations included geriatric teams and women’s health clinics. Vitals and laboratory parameters: the maximum temperature, heart rate, and white blood cell count and the minimum systolic blood pressure values within 24 hours of the otitis encounter were recorded. Statistical tests used included the chi-square test for nominal data and the Student t test for continuous data. P values <.017 were considered significant (Bonferroni correction).

Abbreviations: AOE, acute otitis externa; AOM, acute suppurative OM; OM, otitis media; OME, acute nonsuppurative OM; WBC, white blood cell count.

aSignificant difference between OME and AOM (P < .017).

bSignificant difference between OME and AOE (P < .017).

cSignificant difference between AOM and AOE (P < .017).

dOnly 401 patient-visits were associated with a WBC value.

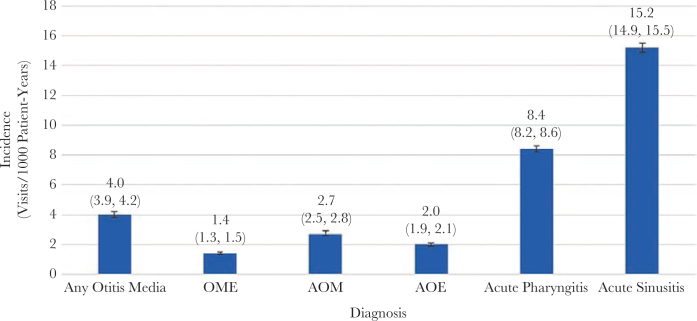

There were 912, 1778, and 1306 patient-visits included in the incidence calculations for OME, AOM, and AOE, respectively, and 668 513 patient-years during the period of observation. The incidence rates were 4.0 (95% CI, 3.9–4.2) per 1000 patient-years for any diagnoses of OM. By comparison, the incidence rates for acute pharyngitis and sinusitis were 8.4 (95% CI, 8.2–8.6) and 15.2 (95% CI, 14.9–15.5) per 1000 patient-years, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence rates of otitis diagnoses (visits per 1000 patient-years). The Any Otitits Media group included patients with a diagnosis of either OME or AOM. The total numbers of visits for acute pharyngitis and sinusitis in the corresponding time frame were 5613 and 10 187, respectively. There were 668 513 patient-years during the period of observation. Abbreviations: AOE, acute otitis externa; AOM, suppurative OM; OME, nonsuppurative OM.

After excluding patients with multiple otitis diagnoses or infectious co-diagnoses, systemic antibiotics were prescribed in 2057/3762 (55%) otitis visits, of which 783/2057 (38%) were amoxicillin/clavulanate and 660/2057 (32%) were amoxicillin. In addition, systemic antibiotics were prescribed in 1800 (71%) of all 2549 OM diagnoses, of which 702/1800 (39%) were amoxicillin/clavulanate and 590/1800 (33%) were amoxicillin (Table 2). Systemic antibiotics were more likely to be prescribed in AOM (1253/1680 [75%]) compared with OME visits (547/869 [63%]; P < .001). Systemic antibiotics were less likely to be prescribed in AOE visits (257/1213 [21%]) compared with OM diagnoses (1800/2549 [71%]; P < .001). In contrast, topical antibiotics were more likely to be prescribed in visits with AOE (839/1213 [69%]) than OM diagnoses (342/2549 [13%]; P < .001). By comparison, 23 126/46 634 (49%) nonotitis ARI visits were treated with antibiotics. Otitis visits, without a concurrent nonotitis ARI diagnosis, accounted for 6% (1609/25 183) of all ARI visits where antibiotics were prescribed.

Table 2.

Systemic Antibiotic Prescribing for OM Diagnoses

| Category, No. (%) | Overall (n = 2549) | Acute Suppurative OM (n = 1680) | Acute Nonsuppurative OM (n = 869) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic antibiotic prescribeda | 1800 (71) | 1253 (75) | 547 (63) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanatea | 702 (39) | 448 (36) | 254 (46) |

| Amoxicillina | 590 (33) | 430 (35) | 160 (29) |

| Azithromycin | 184 (10) | 125 (10) | 59 (11) |

| Other systemic antibioticsa | 354 (20) | 270 (22) | 84 (10) |

Groups compared using chi-square test. Visits could be associated with multiple systemic antibiotics; these visits were counted as each antibiotic given. The rate each individual antibiotic was prescribed was reported as a percentage of the total visits with systemic antibiotic prescribed. Other systemic antibiotics prescribed included: oral cefaclor, cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, cephalexin, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, clindamycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, minocycline, nitrofurantoin, penicillin, rifampin, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and intravenous ceftriaxone and vancomycin.

Abbreviations: OM, otitis media.

aSignificant difference between acute suppurative OM and acute nonsuppurative OM.

Thirty-day return visits and complications were uncommon for OM diagnoses. Otitis-related return to clinic visits (4/2549 [<1%]), ENT consults or procedures (10/2549 [<1%]), and otic complications (21/2549 [1%]) were rare. Otic complications predominately included new-onset hearing loss (17/2549 [1%]); however, 2 cases of new-onset gait disturbance, 1 case of acute mastoiditis, and 1 case of new-onset facial paralysis were also identified. There were no OM visits associated with subsequent development of meningitis or malignant otitis externa. There were no significant differences in complications based upon receipt of systemic antibiotics (68/1800 [4%]) during the initial visit compared with visits without receipt of systemic antibiotics (21/749 [3%]; P = .24). Similarly, return visits and complications were uncommon for AOE (otitis-related return clinic visits: 8/1213 [<1%]; ENT consult or procedures: 6/1213 [<1%]; or otic complications: 19/1213 [2%]). Otic complications paralleled those observed for OM: New-onset hearing loss (10/1213 [1%]), 4 cases of acute mastoiditis, 2 cases of malignant otitis externa, 3 cases of new-onset facial paralysis, and 1 case of new-onset gait disturbance were identified. No significant difference in outcomes was observed between those who received systemic antibiotics (16/257 [6%]) for AOE and those who did not (39/956 [4%]; P = .17). Further, no significant differences in outcomes were seen in AOE visits depending on if patients were treated with systemic antibiotics alone, topical medications alone, or in combination (P > .008).

Discussion

The results of this retrospective cohort study present several aspects of otitis diagnosis and treatment in adults that are sparsely documented in the current literature. We found the incidence of adult OM to be twice that of AOE and half that of pharyngitis based on administrative diagnostic coding. The incidence of OM was more common than we anticipated based on internal comparison with other ARI diagnoses within the VA and limited published studies of OM in adult populations. It is unclear if the OM cases in our study accurately reflect the diagnostic criteria utilized in pediatric populations or if subtle diagnostic differences in AOM or OME affected the true distribution of otitis disease.

Further, in our study codes not classified as suppurative, nonsuppurative, or serous otitis media were the most common diagnostic codes utilized (eg, unspecified otitis media), accounting for most visits. It is likely that visits with these codes were clinically similar to those coded with suppurative otitis media, as the rates of systemic antibiotic treatment in these patients were almost identical (74% with suppurative otitis media and 75% with unspecified otitis media). Visits with midlevel providers or in urgent care clinics were more likely to utilize the unspecified otitis media codes, which may reflect diagnostic uncertainty and an inability to differentiate OME from AOM. As antibiotics are not recommended in OME but are sometimes recommended in AOM, this difficulty with differentiation can result in overtreatment of OME with antibiotics. However, OME was treated with antibiotics only slightly less frequently than AOM (63% vs 75%), suggesting limited awareness of OM recommendations and antibiotic overtreatment.

Many patients had established risk factors for otitis infections, as identified in studies of pediatric patients, such as co-diagnosis with an additional ARI, a history of OM, allergic rhinitis, and exposure to tobacco smoke. Also, patients with an ARI co-diagnosis were more likely to receive systemic antibiotics (448/619 [72%]) compared with those without an ARI co-diagnosis (1609/3143 [51%]; P < .001). Although 12% of the cohort were current smokers, this is similar to the veteran population as a whole [24].

Patients with AOM visits rarely exhibited fever, yet the majority (75%) were treated with antibiotics. In children, watchful waiting without antibiotics is a recommended treatment strategy for children without fever of 102.2°F or higher [2]. In our cohort, 99% of patients with AOM had temperatures <100.4°F, suggesting an opportunity to increase the use of watchful waiting or delayed antibiotic prescriptions in adult patients with AOM.

Systemic antibiotics were prescribed in a substantial number of patients with AOE (21%). Practice guidelines recommend considering systemic antibiotics for AOE in patients with immunocompromised states or diabetes, but only 5/257 (2%) and 63/257 (25%) AOE patients with systemic antibiotics prescribed had comorbid immunosuppression or diabetes, respectively [17].

The majority of visits with AOM associated with a prescribed antibiotic were for amoxicillin/clavulanate rather than amoxicillin. Pediatric AOM guidelines recommend that amoxicillin should be used as the firstline treatment, with amoxicillin/clavulanate being reserved for specific circumstances: concurrent conjunctivitis, treatment with amoxicillin in the past 30 days, or history of recurrent AOM unresponsive to amoxicillin [2, 14]. Visits with conjunctivitis co-diagnoses or history of recurrent AOM were excluded, and of the AOM visits where amoxicillin/clavulanate was prescribed, only 24/448 (5%) patients received amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate in the past 30 days. The rate of use of amoxicillin for AOM in our study (35%) was much lower than in a national study examining pediatric AOM prescribing, in which 54% of antibiotics for AOM in children were amoxicillin [26]. We previously have observed high rates of amoxicillin/clavulanate use in the treatment of pharyngitis within the VA where it is clearly not indicated [18, 25]. None of the facilities included in this analysis have clinical order sets within the electronic health record specific to management of otitis. However, increasing the use of amoxicillin when antibiotics are needed is another stewardship opportunity for adults with AOM.

Finally, adverse 30-day outcomes associated with these visits were low. This suggests that patients with otitis without a significant history of past otitis or complicating presentation are unlikely to develop complications. No significant difference in outcomes between patients who received systemic antibiotics vs those who did not was observed, further supporting the use of watchful waiting for AOM, no antibiotics for OME, and topical only for AOE.

A strength of this analysis included the use of the VA’s CDW to develop a large cohort of adults with an otitis diagnosis. The analysis spanned 6 VA health care facilities and comprised thousands of cases, and to our knowledge, it is the largest evaluation of otitis in adults residing in the United States. Further, as the analysis was embedded within a larger detailed cohort of ARIs, we were able to provide a relative comparison of incidence with commonly diagnosed acute sinusitis and pharyngitis. This analysis has several limitations. The analysis was retrospective, and administrative codes were used to assign the diagnoses within the cohort. It is possible that administrative coding for otitis visits does not accurately reflect provider diagnoses; however, manual chart review for the other ARI conditions (eg, sinusitis and pharyngitis) within the VA CDW exhibited high sensitivity [25]. Further, the VA population is overwhelmingly male, and veterans have a greater comorbidity burden than nonveterans. Veterans may have antibiotic prescriptions filled at non-VA facilities or receive care external to the VA, particularly specialty care such as ENT services in smaller facilities. Finally, outcomes were reports as crude proportions and were not adjusted for differences between antibiotic recipients and nonrecipients.

Data on adult OM are sparse, and direct comparison of findings is difficult due to differences in population studied. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that, globally, in 2005, 51% of OM occurred in patients aged <5 years and the global incidence rate of OM was between 1.49 and 3.14 cases per 100 people-years for people ≥20 years of age. Further, they reported the incidence of AOM to be 5.46 cases per 100 people-years for high-income areas in North America, but this did not discriminate by age [27]. Our study reports the incidence for OM to be 0.40 visits per 100 patient-years, which was lower than the rates reported by the WHO. OM diagnoses have been associated with ARIs in pediatric populations. In a study by Chonmaitree et al., 61% of ARI diagnoses were associated with an AOM or OME in the following 28 days [28]. This cohort’s population showed that only 3% of OM visits were associated with an ARI diagnosis within the 30 days before the index visit, but 16% of patients had an ARI co-diagnosis during their otitis visit.

These study findings pose topics for future research. First, prospective observational studies to establish the diagnostic accuracy and distribution in primary care are needed. Second, chart-level review may be beneficial to identify documented signs and symptoms of otitis diagnosis and treatment. Third, investigation to determine the benefit of antibiotic therapy in adult OM diagnoses could be beneficial, particularly given the high proportion of treatment with antibiotics in this cohort and the low incidence of fever, 1 criterion used in children to determine the need for antibiotic therapy for AOM. In the absence of such studies, educational campaigns to improve diagnosis and antibiotic use may be appropriate. Finally, the full extent of infectious complications, hearing loss, and antibiotic adverse events is unknown, and further work could help in assessing the risk–benefit of such treatments.

Conclusions

We observed a significant number of adult patients with acute otitis diagnoses and found that OM in particular is diagnosed more commonly in adult patients than previously thought. Antibiotic prescribing was often discordant with guideline recommendations for AOE and pediatric guidelines for OME and AOM. Most clinical outcomes were similar irrespective of treatment strategy, which suggests that OM and AOE may be a fruitful diagnosis for future outpatient antibiotic stewardship initiatives among adult patients.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SHEPHERD Grant 200-2011-47039 and with resources from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Roland PS, Stroman DW. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope 2002; 112:1166–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013; 131:e964–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saki N, Rahim F, Nikakhlagh S, et al. Quality of life in children with recurrent acute otitis media in southwestern Iran. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 66:267–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brownlee RC Jr, DeLoache WR, Cowan CC Jr, Jackson HP. Otitis media in children. Incidence, treatment, and prognosis in pediatric practice. J Pediatr 1969; 75:636–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roy E, Hasan KhZ, Haque F, et al. Acute otitis media during the first two years of life in a rural community in Bangladesh: a prospective cohort study. J Health Popul Nutr 2007; 25:414–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang PC, Chang YH, Chuang LJ, et al. Incidence and recurrence of acute otitis media in Taiwan’s pediatric population. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011; 66:395–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Telle DW, Klein JO, Rosner B. Epidemiology of OM during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study. J Infect Dis 1989; 160:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ologe FE, Segun-Busari S, Abdulraheem IS, Afolabi AO. Ear diseases in elderly hospital patients in Nigeria. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60:404–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mills R, Hathorn I. Aetiology and pathology of otitis media with effusion in adult life. J Laryngol Otol 2016; 130:418–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Celin SE, Bluestone CD, Stephenson J, et al. Bacteriology of acute otitis media in adults. JAMA 1991; 266:2249–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwartz LE, Brown RB. Purulent otitis media in adults. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152:2301–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leskinen K, Jero J. Acute complications of otitis media in adults. Clin Otolaryngol 2005; 30:511–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Finkelstein Y, Ophir D, Talmi YP, et al. Adult-onset otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994; 120:517–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanford Guide Web Edition. OM, acute, empiric therapy Available at: https://dva.sanfordguide.com/sanford-guide-online/disease-clinical-condition/otitis-media. Accessed 1 January 2019.

- 15. Rosenfield RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: OM with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016; 154(Suppl 1):S1–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimated burden of acute otitis externa—United States, 2003–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 150:S1–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Madaras-Kelly KJ, Hruza H, Pontefract B, et al. Multi-centered evaluation of an acute respiratory tract infection audit-feedback intervention: impact on antibiotic prescribing rates and patient outcomes. In: Program and abstracts of ID Week, San Francisco, CA, 3–7 October 2018. Abstract 213.

- 19. Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA 2016; 315:1864–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Acuin J. Chronic Suppurative OM – Burden of Illness and Management Options. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones BE, Sauer B, Jones MM, et al. Variation in outpatient antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections in the veteran population: a cross-sectional Study. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bluestone CD. Clinical course, complications and sequelae of acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000; 19:S37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bonferonni CE. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilità. Pubblicazioni del Real Istituto Superiore di Scienze Economiche e Commerciali di Firenze. 1936; 8:3–62.

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco product use among military veterans — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bohan JG, Madaras-Kelly K, Pontefract B, et al. ; ARI Management Improvement Group Evaluation of uncomplicated acute respiratory tract infection management in veterans: a national utilization review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2019; 40:438–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hersh AL, Fleming-Dutra KE, Shapiro DJ, et al. ; Outpatient Antibiotic Use Target-Setting Workgroup Frequency of first-line antibiotic selection among US ambulatory care visits for otitis media, sinusitis, and pharyngitis. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176:1870–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One 2012; 7:e36226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chonmaitree T, Revai K, Grady JJ, et al. Viral upper respiratory tract infection and otitis media complication in young children. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:815–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.