Abstract

Purpose

To complete the baseline trachoma map in Oromia, Ethiopia, by determining prevalences of trichiasis and trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) at evaluation unit (EU) level, covering all districts (woredas) without current prevalence data or active control programs, and to identify factors associated with disease.

Methods

Using standardized methodologies and training developed for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project, we conducted cross-sectional community-based surveys from December 2012 to July 2014.

Results

Teams visited 46,244 households in 2037 clusters from 252 woredas (79 EUs). A total of 127,357 individuals were examined. The overall age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in adults was 0.82% (95% confidence interval, CI, 0.70–0.94%), with 72 EUs covering 240 woredas having trichiasis prevalences above the elimination threshold of 0.2% in those aged ≥15 years. The overall age-adjusted TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds was 23.4%, with 56 EUs covering 218 woredas shown to need implementation of the A, F and E components of the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness and environmental improvement) for 3 years before impact surveys. Younger age, female sex, increased time to the main source of water for face-washing, household use of open defecation, low mean precipitation, low mean annual temperature, and lower altitude, were independently associated with TF in children. The 232 woredas in 64 EUs in which TF prevalence was ≥5% require implementation of the F and E components of the SAFE strategy.

Conclusion

Both active trachoma and trichiasis are highly prevalent in much of Oromia, constituting a significant public health problem for the region.

Keywords: Ethiopia, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, prevalence, risk factors, trachoma, trichiasis

Introduction

Trachoma is the leading infectious cause of blindness, and is caused by conjunctival infection with the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. Early infection manifests as redness and irritation, with follicles on the tarsal conjunctiva; this may meet the definition of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) of the World Health Organization (WHO) simplified trachoma grading system. Repeated infections may result in scarring of the conjunctivae, and alteration in eyelid morphology and function such that in-turning of the eyelashes ensues; this condition is known as trachomatous trichiasis (TT). The in-turned eyelashes rub on the cornea and cause devastating pain at each blink.1 With repeated rubbing, ulceration and subsequent opacification of the normally clear cornea can develop, which may result in visual impairment and blindness.2,3

WHO has targeted trachoma for elimination as a public health problem worldwide by 2020, advocating control using the SAFE strategy (surgery for trichiasis, antibiotics to clear infection, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvement), with the recommended intensity of interventions stratified by the prevalence of disease.4

Trachoma is a public health problem in more than 50 countries, with 232 million people estimated to be at risk of blindness from it in 2014. Significant progress in eliminating trachoma has been made in the past decade, with seven countries (Gambia, Ghana, Iran, Morocco, Myanmar, Oman, and Vietnam)5 having reported achieving the goal of elimination. Ethiopia is estimated to be the most trachoma-affected country in the world.5

Oromia is the largest of the nine regions of Ethiopia by both landmass and number of residents, with the 2015 population estimated to be over 33 million.6 It is divided into 12 town administration units and 18 rural zones; these are further divided into 304 woredas (districts), of which 265 are rural. The 2005–2006 national survey of blindness, low vision and trachoma estimated the region-level prevalence of TF among children 1–9 years of age to be 24.5%, and the TT prevalence in people aged 15 years and older to be 2.8%7. Despite these estimates, which were among the highest known, by 2012 only 23 of the 265 rural woredas had either started interventions against trachoma or had prevalence data to guide programmatic interventions (Table 1, Figure 1). For the purposes of the work presented here, existing district-level prevalence estimates were considered to be adequate if they were (1) designed to estimate the prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years, and (2) had taken place in the 10 years prior to 2012, when the project began.

Table 1. Woredas surveyed for trachoma, or in which interventions against trachoma had commenced, prior to the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP), Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012.

| Zone | Woreda | Year of most recent surveya | TF,b % | Trichiasis,c % | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsi | Ziway Dugda | 2010 | 22.1 | 3 | |

| Dodota | 2010 | 16.9 | 2.5 | ||

| East Shewa | Bora | 2008 | 60 | 12 | |

| Dugda | 2008 | 60 | 7 | ||

| Adami Tullu, Jido Kombolcha | 2008 | 23 | 7 | ||

| Lomie | 2013 | 12.53 | 1.68 | ||

| Adama | 2007 | 19 | 1.7 | MDA stopped in 2011. An impact survey was not done. Re-surveyed with GTMP. | |

| Fentale | 2010 | 10 | 1.7 | ||

| Bosset | 2007 | 19 | 1.7 | MDA stopped in 2011. An impact survey was not done. Re-surveyed with GTMP. | |

| East Wollega | Sibu Sire | 2007 | 24.5 | 3.5 | No woreda-level baseline data; antibiotic distribution commenced using region-level prevalence data (shown). |

| Sasiga | 2010 | 9.6 | 0.7 | ||

| Diga | 2010 | 14 | 2.5 | ||

| Ilu Aba Bora | Gechi | 2011 | 23.2 | 1.6 | |

| Jimma | Sokoru | 2007 | 24.5 | 3.5 | No woreda-level baseline data; antibiotic distribution commenced using region-level prevalence data (shown). |

| Omonada | 2011 | 12.8 | 2.8 | No baseline data. Data shown are from an impact survey conducted after 3 years of antibiotic distribution. | |

| North Shewa | Dera | 2010 | 34.1 | 8.7 | |

| Hidhebu Abote | 2008 | 42.9 | 4.8 | ||

| Wore Jarso | 2010 | 16 | 9.5 | ||

| West Arsi | Arsi Negele | 2009 | 39.6 | 6.9 | |

| West Shewa | Dendi | 2010 | 27.4 | 0 | |

| Gindeberet | 2011 | 55.3 | 1.7 | ||

| Abune Gindeberet | 2011 | 55.3 | 1.7 | ||

| Bako Tibe | 2010 | 37 | 0.5 |

Population-based prevalence survey.

Population-level prevalence in those aged 1–9 years.

Population-level prevalence in those aged ≥15 years.

MDA, mass drug administration; TF, trachomatous inflammation – follicular.

Figure 1.

Map of woredas with previous trachoma mapping, or in which interventions against trachoma had commenced prior to the Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012.

Based on this assessment, over 230 woredas in Oromia were identified that did not have program ready trachoma data, or had data that were considered to be outdated. WHO guidelines recommend that district-level estimates are used to make decisions on where to implement the SAFE strategy. However, a 2010 WHO recommendation allowed for mapping at larger scales in suspected highly trachoma-endemic areas, in order to expedite the start of much needed interventions.8 To complete the map of trachoma in Oromia, we undertook a series of population-based prevalence surveys covering all remaining unmapped rural woredas in Oromia. Because trachoma was expected to be highly and widely endemic in the region, surveys were initially conducted at sub-zone level, i.e. generally involving the combination of several contiguous woredas into a single evaluation unit (EU). The objectives of each survey were to determine the prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years, and to estimate the prevalence of trichiasis among people aged 15 years and older, each at sub-zonal level; and to identify risk factors associated with TF and trichiasis in these age groups.

Materials and methods

In general, the methodology used for this work followed that published previously for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP),9 with context specific details added. Surveys were initially undertaken at sub-zonal level, with woredas grouped following sociodemographic divisions and existing administrative boundaries, in order to form contiguous EUs of approximately 500,000 inhabitants.

Prior to the start of field work, fieldworkers were deployed to obtain a list of all kebeles (the smallest administrative units with population estimates) and geres (kebele divisions consisting of about 30 households each) in all woredas included in each survey, from the respective woreda health offices. Where an EU comprised more than one woreda, the number of kebeles selected from each woreda was proportional to that woreda’s population. Kebeles were then selected with a probability proportional to size technique. This provided all individuals in the survey populations an equal probability of selection. At the second stage, one gere was randomly selected (by drawing lots) from the list of all geres in each selected kebele. An additional gere was sampled within the kebele if teams were unable to sample 30 households in the first selected gere.

Based on the most recent census data, it was estimated that 48 children aged 1–9 years would be found in each gere.6 Therefore, to achieve the target framework of 1222 children in sampled households in each EU, 1222/48 = 25.5 clusters were needed, so 26 clusters were planned to be visited per EU. All individuals at least 1 year old in selected geres were invited to be included, and the gere was considered to be the cluster unit for the purposes of analysis.

Survey teams

Survey teams comprised a trachoma grader, a data recorder, and a driver. Graders and recorders attended the standardized 5-day training using GTMP training manual version 1, held in Bishoftu, Oromia, with both graders and recorders trained in the survey rationale and methodology, and each having to pass an examination before being considered for the survey team. Full details are provided elsewhere.9

Ethical review

Ethical approval was obtained from Oromia Regional Health Bureau Ethics Review Committee (BEFO/HBTFH/1-8/2110) and the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (6319). Official letters of permission were obtained from each zonal and woreda health office.

Informed verbal consent was obtained from all study participants. For children aged <15 years, consent was obtained from the head of household. Verbal consent was considered most appropriate because of low literacy rates among the survey population. People with active trachoma (TF and/or trachomatous inflammation – intense) were provided with a course of tetracycline hydrochloride 1% eye ointment and given instruction for its use. Participants found to have trichiasis were referred to the nearest eye health facility for further assessment. The cost of lid surgery for those with trichiasis was borne by the project.

Risk factors

Water, sanitation and hygiene variables were collected by data recorders by direct observation and via standardized interview questions with the household head. Variables related to water access and source type for both drinking and washing, and sanitation types, used WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program definitions.9,10

Data on climatic variables possibly related to trachoma risk were obtained during fieldwork and from existing data sources, using knowledge of the epidemiology of trachoma in other environments. Altitude was collected directly at the time of the surveys by recording global positioning system (GPS) coordinates at each household. Climate variables derived from local meteorological stations were obtained from WorldClim variables (worldclim.org), at a resolution of 2.5 arc minutes (~5 km).11 Variables chosen were those considered to be potentially relevant to C. trachomatis infection transmission, including mean annual temperature, mean annual precipitation, precipitation in the driest month, maximum temperature in the hottest month, and minimum temperature in the coldest month. Climatic variables were assigned to households at cluster level, with the cluster GPS coordinates derived from the means of household GPS coordinates.

Data analysis

Descriptive data and prevalence results were produced using R 3.0.2 (2013, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). TF prevalence in children aged 1–9 years was adjusted for age in 1-year age-bands using the latest available census data.12 Trichiasis prevalence in those aged ≥15 years was adjusted for age and sex in 5-year age-bands. Trichiasis prevalence for the whole population was estimated by halving the ≥15 years’ trichiasis prevalence.13 Confidence intervals (CIs) were generated by bootstrapping adjusted mean cluster-level outcome proportions. Raster point values for climatic variables were extracted using ArcGIS 10.3 (Spatial Analyst; Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). Data clustering was analyzed using Anselin Local Morans I statistic at polygon level, with contiguity of edges and corners between polygons used to define spatial relationships, and outcomes standardized for the number of associated polygons, in ArcGIS 10.3 (Spatial Statistics).

Risk factor analysis was performed using Stata 10.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). A multi-level hierarchical model was used to account for clustering at gere and household level. Co-linearity of variables was examined using Mantel-Haenszel tests of association, but was not an absolute exclusion criterion. A stepwise inclusion approach was used for the multivariable model, with variables considered for inclusion if the univariable association was significant at the p < 0.10 level (Wald’s test). Variables were retained in the model if statistical significance was found at the p < 0.05 level (Likelihood ratio test).

Results

All 18 rural zones of Oromia region were included in the surveys. A total of 59 sub-zone level EUs, covering 252 woredas, were surveyed from December 2012 to July 2013. Remapping (by adding additional clusters) occurred in sub-zones found to have TF prevalences in 1–9-year-olds <10%, following the WHO recommendation8 that district-level data be obtained in this circumstance. This affected seven sub-zones covering 38 woredas, resulting in their division into woreda-sized EUs for district-level mapping. For reasons of practicality, remapping was truncated after 20 of these woredas had been remapped (from May to July 2014), with the provisional decision not to remap the remaining 18 low prevalence woredas based on results from the first 20, and challengeable should further research suggest that it be reviewed.

A total of 79 EUs were surveyed, with 46,244 households in 2037 clusters visited, and 139,105 people sampled for inclusion. A total of 127,357 participants (91.6%) consented and were examined, with a mean of 2.75 people examined in each household. A total of 41,642 children aged 1–9 years, and a total of 69,481 individuals aged 15 years or older were examined. In total, 9008 cases of TF and 865 cases of trichiasis were identified.

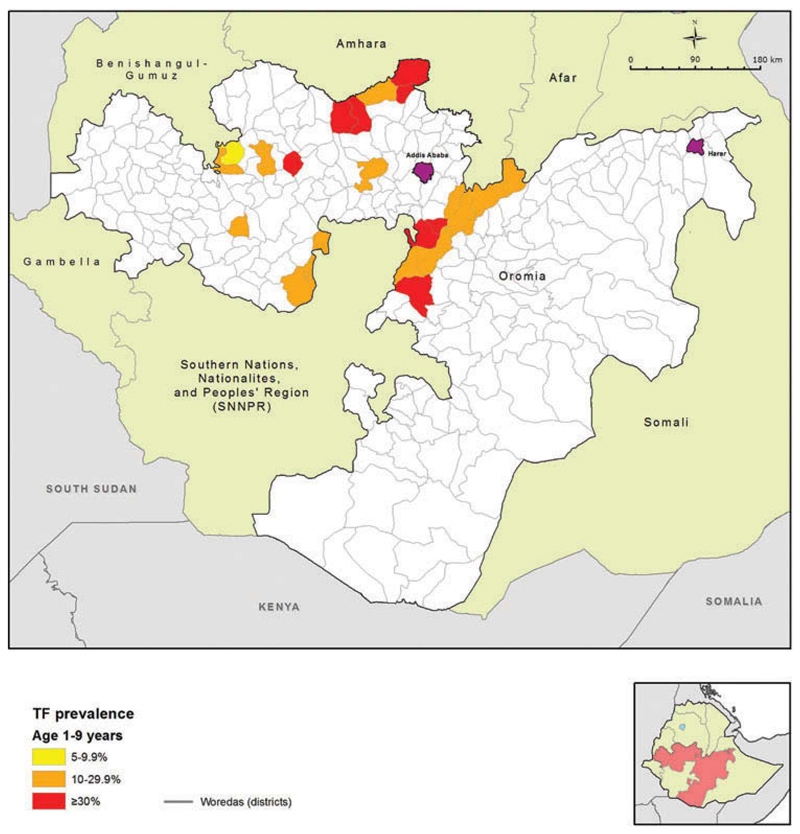

The age-adjusted TF prevalence among children aged 1–9 years ranged from a low of 1.1% (95% CI 0.3–2.2%) in Gaji woreda of West Wellega, to a high of 48.7% (95% CI 41.6–57.1%) in the Horo Guduru zone woredas (Figure 2). The mean age-adjusted TF prevalence over all EUs was 23.4% (95% CI 22.8–24.2%) in the same age group. Of 79 EUs surveyed, 56 (71%) showed a TF prevalence ≥10% among children aged 1–9 years. In other words, 218 (87%) of 252 woredas included in the surveys were part of EUs that had TF prevalence ≥10%. Each of these woredas require mass distribution of azithromycin, together with implementation of the F and E components of the SAFE strategy, for at least 3 years before impact survey.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

A relatively low prevalence of TF was observed in the western part of Oromia, including EUs in Ilu Ababora, Kelem Wellega, and part of West Wellega (Figure 2). This area formed a group of 22 contiguous low prevalence EUs; an overall low prevalence EU grouping statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level (Anselin Local Moran’s I).

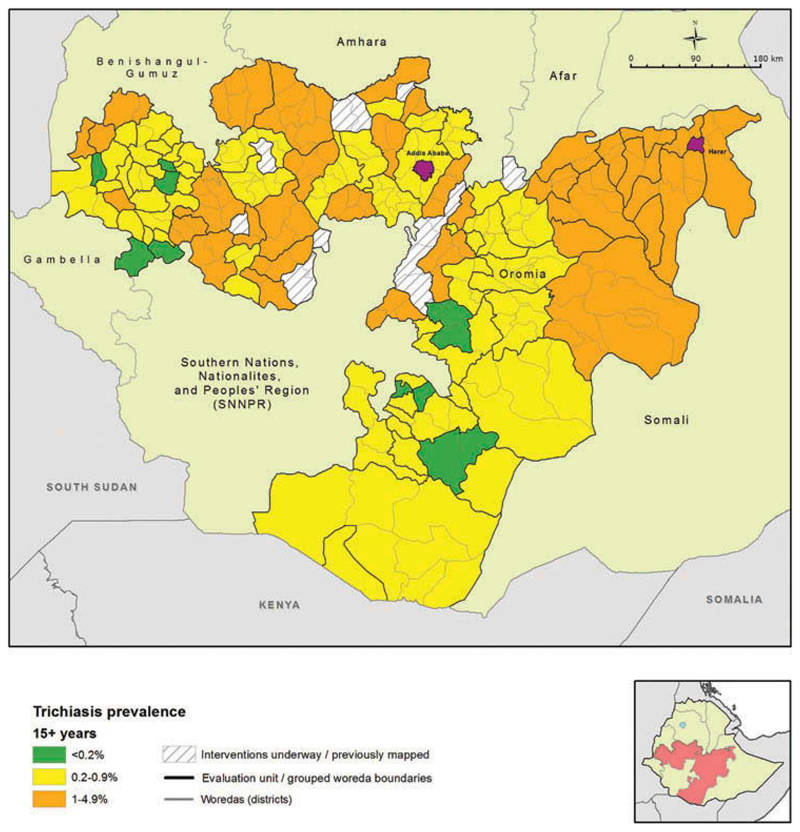

The age- and sex-adjusted trichiasis prevalence in those aged 15 years and older ranged from 0.0% (95% CI 0.0–0.1%) in Nole Kaba to 2.5% (95% CI 1.6–3.6%) in the EU covering Kersa, Mean, Tiro, and Afeta woredas of Jimma Zone (Figure 3). The mean age- and sex-adjusted trichiasis prevalence over all EUs was 0.82% (95% CI 0.70–0.94%) in those aged 15 years or older. Overall, 72 EUs had a trichiasis prevalence in those aged 15 years or older that was higher than the elimination threshold of 0.2%. In other words, 240 woredas (95.2% of all woredas included in the surveys) were part of EUs that had a prevalence of trichiasis suggestive of a significant public health problem.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of trichiasis in adults aged ≥15 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

TF and trichiasis prevalences by EU are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2. Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

| Zone | Evaluation unit | Children aged 1–9 years examined, n | TF cases, n | Unadjusted TF, % | Adjusted TF, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsi | Amigna, Bele Gasgar, Robe, Seru, Shirka | 1091 | 307 | 28.1 | 29.6 (23.4–36.4) |

| Aseko, Chole, Gololcha (Arsi), Guna, Merti | 878 | 221 | 25.2 | 24.3 (17.1–31.8) | |

| Degeluna Tijo, Enkelo Wabe, Limuna Bilbilo, Lude Hitosa, Tena | 1022 | 243 | 23.8 | 20.9 (14.2–27.4) | |

| Deksis, Dodota, Jeju, Sire, Sude | 1036 | 315 | 30.4 | 30.1 (24.1–38.1) | |

| Hitosa, Munessa, Tiyo, Ziway Dugda | 1017 | 274 | 26.9 | 23.6 (15.7–31.5) | |

| Bale | Agarfa, Dinsho, Gasera, Goba, Sinana | 1023 | 480 | 46.9 | 42.3 (35.7–51.0) |

| Berbere, Dolo Mena, Gura Damole, Harena Buluk, Meda Welabu | 1041 | 441 | 42.4 | 38.8 (32.5–45.5) | |

| Dawe Kachen, Dawe Serer, Ginir, Gololcha (Bale), Goro (Bale), Lege Hida, Rayitu, Seweyna | 1008 | 432 | 42.9 | 40.4 (33.2–49.3) | |

| Borena | Abaya, Bule Hora, Dugda Dawa, Gelana | 1292 | 502 | 38.9 | 37.1 (30.2–43.7) |

| Arero, Dehas, Dire, Miyo, Moyale, Teltele, Yabelo | 882 | 272 | 30.8 | 29.2 (20.9–38.6) | |

| Dillo, Melka Soda | 1073 | 485 | 45.2 | 43.5 (35.4–53.1) | |

| East Harerge | Babile, Chinaksen, Gursum, Jarso | 1076 | 487 | 45.3 | 42.3 (34.2–48.3) |

| Bedeno, Deder, Malka Balo | 993 | 354 | 35.6 | 30.9 (23.2–39.6) | |

| Fedis, Girawa, Golo Oda, Meyu, Midega Tola | 1187 | 575 | 48.4 | 46.6 (37.9–54.1) | |

| Goro Gutu, Kersa, Meta | 1120 | 394 | 35.2 | 34.6 (29.2–40.3) | |

| Haro Maya, Kombolcha, Kurfa Chele | 1061 | 267 | 25.2 | 25.0 (18.8–30.5) | |

| Kumbi | 1046 | 426 | 40.7 | 38.0 (32.2–43.2) | |

| East Shewa | Ada’a, Gimbichu, Liben | 758 | 297 | 39.2 | 37.8 (31.4–46.0) |

| Adama | 711 | 262 | 36.8 | 34.7 (24.1–37.8) | |

| Boset | 891 | 303 | 34.0 | 31.2 (27.1–43.8) | |

| East Wollega | Boneya Boshe, Jimma Arjo, Leka Dulecha, Nunu Kumba, Wama Hagalo, Wayu Tuka | 840 | 177 | 21.1 | 19.8 (13.0–27.9) |

| Diga, Gobu Seyo, Gudeya Bila, Guto Gida, Sasiga | 845 | 184 | 21.8 | 18.4 (11.0–27.6) | |

| Gida Kiremu, Haro Limu, Ibantu, Kiramu, Limu | 994 | 441 | 44.4 | 43.2 (34.3–51.3) | |

| Guji | Adola, Hambela Wamena, Liben (Guji), Odo Shakiso, Wadera | 1265 | 469 | 37.1 | 35.5 (29.2–42.7) |

| Afele Kola (Dima), Ana Sora, Gora Dola, Saba Boru | 1071 | 264 | 24.6 | 24.8 (18.1–33.0) | |

| Bore, Girja (Harenfema), Kercha, Uraga | 1253 | 434 | 34.6 | 29.7 (21.3–37.4) | |

| Horo Guduru | Ababo, Abay Chomen, Abe Dongoro, Amuru, Guduru, Horo (Horo Guduru), Jarte Jardega, Jimma Genete, Jimma Rare | 967 | 488 | 50.5 | 48.7 (41.6–57.1) |

| Illu Aba bora | Ale | 631 | 42 | 6.7 | 4.9 (1.5–8.7) |

| Alge Sachi, Bilo Nopha, Metu Zuria | 843 | 71 | 8.4 | 5.5 (2.1–10.2) | |

| Badele Zuria, Chora, Chwaka, Dabo Hana, Dega, Dorani, Meko | 943 | 157 | 16.6 | 16.0 (10.0–23.4) | |

| Bicho, Borecha, Dedesa, Hurumu, Yayu | 803 | 212 | 26.4 | 21.0 (14.1–28.3) | |

| Bure | 694 | 73 | 10.5 | 8.8 (4.4–13.8) | |

| Darimu | 954 | 95 | 10.0 | 7.3 (3.5–12.2) | |

| Didu | 762 | 82 | 10.8 | 10.2 (6.6–14.6) | |

| Halu (Huka) | 549 | 10 | 1.8 | 1.2 (0.4–1.9) | |

| Nono Sale | 332 | 74 | 22.3 | 22.4 (15.0–30.1) | |

| Jimma | Chora Botor, Limu Kosa, Limu Seka | 933 | 215 | 23.0 | 20.5 (13.4–28.2) |

| Dedo, Seka Chekorsa | 1012 | 488 | 48.2 | 45.9 (38.8–52.2) | |

| Gera, Nono Benja, Setema, Sigmo | 972 | 479 | 49.3 | 46.3 (37.7–53.5) | |

| Goma, Guma, Shebe Sambo | 991 | 431 | 43.5 | 41.5 (32.9–50.2) | |

| Kersa (Jimma), Mena (Jimma), Tiro Afeta | 1103 | 400 | 36.3 | 35.5 (27.3–44.4) | |

| Kelem Wollega | Anfilo, Gidami, Sayo | 879 | 29 | 3.3 | 3.2 (1.0–4.9) |

| Dale Sadi, Gawo Kebe, Lalo Kile | 937 | 89 | 9.5 | 8.6 (4.1–13.0) | |

| Dale Wabera | 886 | 42 | 4.7 | 6.3 (2.7–10.9) | |

| Hawa Galan | 1331 | 154 | 11.6 | 10.0 (4.6–16.0) | |

| Jimma Horo | 1027 | 22 | 2.1 | 2.9 (1.0–5.6) | |

| Yama Logi Welel | 931 | 41 | 4.4 | 4.2 (1.7–6.2) | |

| North Shoa | Abichuna Gne’a, Aleltu, Jida, Kembibit | 861 | 223 | 25.9 | 25.5 (18.2–33.6) |

| Debre Libanos, Kuyu, Wuchale, Yaya Gulele | 968 | 466 | 48.1 | 47.1 (40.0–55.9) | |

| Degem, Dera, Gerar Jarso, Wara Jarso | 824 | 411 | 49.9 | 48.4 (40.3–58.0) | |

| South West Shewa | Akaki, Bereh, Mulo, Sebeta Hewas, Sululta, Walmara | 881 | 290 | 32.9 | 29.8 (21.2–38.5) |

| Ameya, Goro, Waliso, Wenchi | 1159 | 391 | 33.7 | 32.1 (22.6–41.8) | |

| Becho, Dawo, Ilu, Kersana Malima, Seden Sodo, Sodo Daci, Tole | 1006 | 316 | 31.4 | 30.3 (23.2–37.6) | |

| West Harerge | Anchar, Goba Koricha, Habro | 1040 | 391 | 37.6 | 36.3 (28.7–45.8) |

| Boke, Daro Lebu, Gemechis, Oda Bultum | 1231 | 416 | 33.8 | 33.4 (27.3–41.2) | |

| Chiro Zuria, Hawi Gudina, Mieso | 1047 | 304 | 29.0 | 28.3 (22.4–35.3) | |

| Doba, Burka Demtu, Mesela, Tulo | 978 | 207 | 21.2 | 21.8 (14.4–30.4) | |

| West Shewa | Adda Berga, Ejere (Addis Alem), Meta Robi | 950 | 348 | 36.6 | 35.4 (27.3–43.4) |

| Ambo Zuria, Jibat, Nono, Tikur Enchini, Toke Kutaye | 1058 | 330 | 31.2 | 29.1 (22.9–37.2) | |

| Bako Tibe, Cheliya, Ilu Gelan, Dano, Mida Kegn | 1100 | 438 | 39.8 | 39.8 (31.0–47.3) | |

| Dendi, Ifata, Jeldu | 1084 | 190 | 17.5 | 17.0 (12.4–22.1) | |

| West Arsi | Adaba, Kokosa, Nenesebo | 1159 | 143 | 12.3 | 13.2 (7.5–18.6) |

| Dodola, Gedeb Asasa, Kore | 1381 | 317 | 23.0 | 21.9 (15.6–29.7) | |

| Shalla, Shashemene, Siraro | 1327 | 620 | 46.7 | 45.8 (37.8–55.1) | |

| Wondo, Kofele | 1497 | 383 | 25.6 | 27.3 (20.0–35.5) | |

| West Wollega | Ayra, Guliso, Jarso, Nejo | 714 | 28 | 3.9 | 3.9 (1.2–7.7) |

| Babo | 997 | 25 | 2.5 | 2.5 (1.0–4.8) | |

| Begi | 1079 | 109 | 10.1 | 9.3 (6.5–12.8) | |

| Boji Chekorsa | 778 | 20 | 2.6 | 2.8 (0.7–5.9) | |

| Boji Dirmeji | 640 | 8 | 1.3 | 1.2 (0.3–2.1) | |

| Gaji | 780 | 10 | 1.3 | 1.1 (0.3–2.2) | |

| Gimbi | 713 | 20 | 2.8 | 1.8 (0.8–3.3) | |

| Gudetu Kondole | 1197 | 174 | 14.5 | 14.3 (8.5–19.9) | |

| Haru | 708 | 20 | 2.8 | 2.9 (1.2–4.6) | |

| Homa, Yubdo | 742 | 53 | 7.1 | 5.7 (2.1–8.5) | |

| Kiltu Kara, Mana Sibu | 949 | 82 | 8.6 | 8.0 (3.7–13.8) | |

| Lalo Asabi | 705 | 18 | 2.6 | 2.9 (0.4–6.6) | |

| Nole Kaba | 741 | 33 | 4.5 | 4.3 (1.2–7.2) | |

| Sayo Nole | 789 | 25 | 3.2 | 2.1 (0.4–4.5) |

CI, confidence interval.

Table 3. Prevalence of trichiasis in adults aged ≥15 years by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

| Zone | Evaluation Unit | Adults ≥15 years examined, n | Trichiasis cases, n | Unadjusted trichiasis, % | Adjusted trichiasis, % 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsi | Amigna, Bele Gasgar, Robe, Seru, Shirka | 1371 | 10 | 0.7 | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) |

| Aseko, Chole, Gololcha (Arsi), Guna, Merti | 1280 | 21 | 1.6 | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | |

| Degeluna Tijo, Enkelo Wabe, Limuna Bilbilo, Lude Hitosa, Tena | 1332 | 15 | 1.1 | 0.8 (0.2–1.5) | |

| Deksis, Dodota, Jeju, Sire, Sude | 1282 | 18 | 1.4 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | |

| Hitosa, Munessa, Tiyo, Ziway Dugda | 1394 | 31 | 2.2 | 1.3 (0.7–2.0) | |

| Bale | Agarfa, Dinsho, Gasera, Goba, Sinana | 1514 | 7 | 0.5 | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) |

| Berbere, Dolo Mena, Gura Damole, Harena Buluk, Meda Welabu | 1137 | 12 | 1.1 | 0.7 (0.3–1.0) | |

| Dawe Kachen, Dawe Serer, Ginir, Gololcha (Bale), Goro (Bale), Lege Hida, Rayitu, Seweyna | 1303 | 33 | 2.5 | 1.5 (0.9–2.1) | |

| Borena | Abaya, Bule Hora, Dugda Dawa, Gelana | 1283 | 14 | 1.1 | 0.7 (0.2–1.1) |

| Arero, Dehas, Dire, Miyo, Moyale, Teltele, Yabelo | 1275 | 29 | 2.3 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | |

| Dillo, Melka Soda | 1170 | 12 | 1.0 | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | |

| East Harerge | Babile, Chinaksen, Gursum, Jarso | 1364 | 30 | 2.2 | 1.1 (0.6–1.6) |

| Bedeno, Deder, Malka Balo | 1321 | 30 | 2.3 | 1.1 (0.6–1.6) | |

| Boke, Daro Lebu, Gemechis, Oda Bultum | 1403 | 37 | 2.6 | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) | |

| Fedis, Girawa, Golo Oda, Meyu, Midega Tola | 1586 | 49 | 3.1 | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | |

| Goro Gutu, Kersa, Meta | 1537 | 47 | 3.1 | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) | |

| Haro Maya, Kombolcha, Kurfa Chele | 1478 | 42 | 2.8 | 1.4 (0.6–2.0) | |

| Kumbi | 1096 | 30 | 2.7 | 1.0 (0.5–1.6) | |

| East Shewa | Ada’a, Gimbichu, Liben | 1235 | 42 | 3.4 | 1.5 (0.8–2.5) |

| Adama | 1318 | 31 | 2.4 | 1.2 (0.4–1.3) | |

| Boset | 1580 | 32 | 2.0 | 0.9 (0.7–1.8) | |

| East Wollega | Boneya Boshe, Jimma Arjo, Leka Dulecha, Nunu Kumba, Wama Hagalo, Wayu Tuka | 1477 | 18 | 1.2 | 0.7 (0.3–1.1) |

| Diga, Gobu Seyo, Gudeya Bila, Guto Gida, Sasiga | 1470 | 14 | 1.0 | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | |

| Gida Kiremu, Haro Limu, Ibantu, Kiramu, Limu | 1453 | 29 | 2.0 | 1.1 (0.5–1.9) | |

| Guji | Adola, Hambela Wamena, Liben (Guji), Odo Shakiso, Wadera | 1354 | 19 | 1.4 | 0.9 (0.3–1.9) |

| Afele Kola (Dima), Ana Sora, Gora Dola, Saba Boru | 1163 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | |

| Bore, Girja (Harenfema), Kercha, Uraga | 1314 | 9 | 0.7 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | |

| Horo Guduru | Ababo, Abay Chomen, Abe Dongoro, Amuru, Guduru, Horo (Horo Guduru), Jarte Jardega, Jimma Genete, Jimma Rare | 1458 | 32 | 2.2 | 1.5 (0.7–2.3) |

| Illu Aba bora | Ale | 1612 | 7 | 0.4 | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) |

| Alge Sachi, Bilo Nopha, Metu Zuria | 1720 | 11 | 0.6 | 0.5 (0.1–1.1) | |

| Badele Zuria, Chora, Chwaka, Dabo Hana, Dega, Dorani, Meko | 1593 | 25 | 1.6 | 1.1 (0.5–2.0) | |

| Bicho, Borecha, Dedesa, Hurumu, Yayu | 1644 | 24 | 1.5 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | |

| Bure | 1617 | 6 | 0.4 | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) | |

| Darimu | 1695 | 10 | 0.6 | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | |

| Didu | 1582 | 3 | 0.2 | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | |

| Halu (Huka) | 1600 | 9 | 0.6 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | |

| Nono Sale | 780 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | |

| Jimma | Chora Botor, Limu Kosa, Limu Seka | 1614 | 26 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.4–1.6) |

| Dedo, Seka Chekorsa | 1511 | 49 | 3.2 | 2.3 (1.4–3.3) | |

| Gera, Nono Benja, Setema, Sigmo | 1349 | 28 | 2.1 | 1.6 (0.7–2.8) | |

| Goma, Guma, Shebe Sambo | 1634 | 35 | 2.1 | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | |

| Kersa, Mena, Tiro Afeta | 1523 | 63 | 4.1 | 2.5 (1.6–3.6) | |

| Kelem Wollega | Anfilo, Gidami, Sayo | 1630 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) |

| Dale Sadi, Gawo Kebe, Lalo Kile | 1617 | 14 | 0.9 | 0.6 (0.2–0.9) | |

| Dale Wabera | 1817 | 19 | 1.0 | 0.7 (0.3–1.1) | |

| Hawa Galan | 1846 | 30 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.5–1.3) | |

| Jimma Horo | 1765 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | |

| Yama Logi Welel | 1766 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.2 (0.0–0.5) | |

| North Shoa | Abichuna Gne’a, Aleltu, Jida, Kembibit | 1728 | 10 | 0.6 | 0.5 (0.1–1.0) |

| Debre Libanos, Kuyu, Wuchale, Yaya Gulele | 1682 | 23 | 1.4 | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | |

| Degem, Dera, Gerar Jarso, Wara Jarso | 1582 | 52 | 3.3 | 2.0 (1.3–2.9) | |

| South West Shewa | Akaki, Bereh, Mulo, Sebeta Hewas, Sululta, Walmara | 1553 | 19 | 1.2 | 0.7 (0.3–1.3) |

| Ameya, Goro, Waliso, Wonchi | 1716 | 55 | 3.2 | 1.7 (0.9–2.4) | |

| Becho, Dawo, Ilu, Kersana Malima, Seden Sodo, Sodo Daci, Tole | 1508 | 25 | 1.7 | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | |

| West Arsi | Adaba, Kokosa, Nenesebo | 1289 | 5 | 0.4 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) |

| Dodola, Gedeb Asasa, Kore | 1368 | 4 | 0.3 | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | |

| Shalla, Shashemene, Siraro | 1416 | 35 | 2.5 | 1.7 (1.0–2.5) | |

| Wondo, Kofele | 1659 | 16 | 1.0 | 0.7 (0.2–1.2) | |

| West Harerge | Anchar, Goba Koricha, Habro | 1527 | 49 | 3.2 | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) |

| Chiro Zuria, Hawi Gudina, Mieso | 1461 | 46 | 3.1 | 1.8 (1.1–2.3) | |

| Doba, Burka Demtu, Mesela, Tulo | 1455 | 29 | 2.0 | 1.0 (0.5–1.3) | |

| West Shewa | Adda Berga, Ejere (Addis Alem), Meta Robi | 1555 | 28 | 1.8 | 1.0 (0.5–1.5) |

| Ambo Zuria, Jibat, Nono, Tikur Enchini, Toke Kutaye | 1457 | 15 | 1.0 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | |

| Bako Tibe, Cheliya, Ilu Gelan, Dano, Mida Kegn | 1632 | 33 | 2.0 | 1.2 (0.7–1.8) | |

| Dendi, Ifata, Jeldu | 1653 | 10 | 0.6 | 0.4 (0.1–0.9) | |

| West Wollega | Ayra, Guliso, Jarso (West Wollega), Nejo | 1689 | 12 | 0.7 | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) |

| Babo | 1782 | 14 | 0.8 | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) | |

| Begi | 1795 | 21 | 1.2 | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) | |

| Boji Chekorsa | 1783 | 13 | 0.7 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | |

| Boji Dirmeji | 1801 | 15 | 0.8 | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | |

| Gaji | 1642 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | |

| Gimbi | 1581 | 18 | 1.1 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | |

| Gudetu Kondole | 1750 | 27 | 1.5 | 1.3 (0.7–2.0) | |

| Haru | 1638 | 10 | 0.6 | 0.4 (0.1–0.8) | |

| Homa, Yubdo | 1554 | 9 | 0.6 | 0.2 (0–0.4) | |

| Kiltu Kara, Mana Sibu | 1582 | 18 | 1.1 | 1.1 (0.4–1.9) | |

| Lalo Asabi | 1677 | 9 | 0.5 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | |

| Nole Kaba | 1586 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | |

| Sayo Nole | 1510 | 4 | 0.3 | 0.2 (0–0.5) |

CI, confidence interval.

Clustering of TF and trichiasis

Null models for both TF and trichiasis considering age and sex showed statistically significant clustering at EU, kebele (cluster) and household levels. For TF, the estimate for the standard deviation of the random effects intercept on the odds scale for between-EU clustering was 5.8 (standard error, SE, 1.16, p < 0.0001); for between-kebele clustering was 4.3 (SE 1.04, p < 0.0001); and for between-household clustering was 3.5 (SE 1.05, p < 0.0001). For trichiasis, the estimate for the standard deviation of the random effects intercept on the odds scale for between-EU clustering was 2.10 (SE 1.08, p < 0.0001); for between-kebele clustering was 2.05 (SE 1.07, p < 0.0001); and for between-household clustering was 1.94 (SE 1.19, p < 0.0001). For both TF and trichiasis, clustering was strongest at the EU level, but the model adjusting for clustering at both EU and kebele level was a better fit to the data (likelihood ratio test, p < 0.0001). All subsequent analyses using hierarchical regression models accounted for both the EU and kebele in which examined individuals resided.

TF risk factors

Full univariable results for the outcome TF in children aged 1–9 years are shown in Table 4. A multivariable analysis was performed to identify independent predictors for TF in this age group. Younger age, female sex, greater time to main source of washing water, household adults’ use of open defecation, and lower annual precipitation, were all independent predictors of TF. Living at higher altitudes was associated with decreased odds of TF in children. Full multivariable results are shown in Table 5.

Table 4. Multilevel univariable analysis of factors related to trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

| Variable | n | TF, % | Univariable odds ratio (95% CI)a | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | |||||

| Age, years | 1–4 | 17,092 | 28.6 | 2.36 (2.22–2.50) | <0.0001 |

| 5–9 | 24,550 | 16.8 | 1 | ||

| Sex | Male | 20,679 | 21.4 | ||

| Female | 20,963 | 21.8 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | <0.0001 | |

| Household | |||||

| Children aged 1–9 years in household, n | 1–3 | 36,822 | 22.6 | 1 | |

| ≥4 | 4820 | 14.6 | 1.12 (0.99–1.25) | 0.1473 | |

| Inhabitants in household, n | 1–5 | 30,507 | 25.4 | 1 | |

| ≥6 | 11,135 | 11.3 | 1.00 (0.91–1.11) | 0.2879 | |

| Open defecation (no facilities, bush, or field) | Yes | 15,576 | 30.7 | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | |

| No | 26,066 | 16.2 | 1 | ||

| Drinking source surface waterc | Yes | 7733 | 24.0 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | 0.7583 |

| No | 33,909 | 21.1 | 1 | ||

| Time to main source of drinking water, minutesd | <30 | 19,657 | 17.3 | 1 | |

| ≥30 | 21,985 | 25.6 | 1.11 (1.01–1.22) | 0.0391 | |

| Washing source surface waterc | Yes | 9081 | 22.7 | 0.99 (0.87–1.13) | 0.1213 |

| No | 33,949 | 20.5 | 1 | ||

| Time to main source of water used for face-washing, minutesd | <30 | 20,176 | 17.3 | 1 | 0.014 |

| ≥30 | 21,436 | 25.7 | 1.14 (1.04–1.25) | ||

| All washing at source | 30 | 6.7 | 2.30 (0.34–15.55) | ||

| Cluster-level geoclimatic | |||||

| Altitudee, m above sea level | <2500 | 37,034 | 21.5 | 1 | |

| ≥2500 | 4,595 | 22.4 | 0.41 (0.33–0.50) | <0.0001 | |

| Maximum temperature of warmest monthf, °C | <25 | 5,606 | 25.8 | 1 | |

| ≥25 | 36,036 | 21.0 | 2.05 (1.64–2.59) | ||

| Mean annual precipitationf, mm | <1000 | 9,319 | 37.7 | 8.53 (6.89–10.57) | <0.0001 |

| 1000–1499 | 16,308 | 22.0 | 3.18 (2.61–3.87) | ||

| ≥1500 | 16,015 | 11.9 | 1 | ||

Multilevel univariable random effects regression accounting for clustering at evaluation unit and kebele (cluster) level.

Wald’s test.

River, dam, lake, canal.

Time for round-trip estimated by household head.

From GPS coordinates of household collected at time of survey.

From estimates of mean kebele (cluster) coordinates extracted from Bioclim rasters (Worldclim.org).

CI, confidence interval.

Table 5. Multilevel multivariable analysis of factors related to trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

| Variable | Multivariable odds ratioa | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | |||

| Age 1–4 years (reference 5–9 years) | 2.36 | <0.00001 | |

| Female sex | 1.08 | 0.011 | |

| Household | |||

| Open defecation (no facilities, bush, or field) | 1.16 | <0.0001 | |

| Time to main source of water used for face-washing, minutes | <30 | 1.00 | 0.0391 |

| ≥30 | 1.12 | ||

| All washing at source | 2.43 | ||

| Cluster-level geoclimatic | |||

| Altitudec, m above sea level | ≥2500 | 0.44 | <0.0001 |

| Mean annual precipitationd, mm | <1000 | 2.03 | 0.0022 |

| 1000–1499 | 1.59 | ||

| ≥1500 | 1.00 | ||

Multilevel multivariable random effects logistic regression accounting for clustering at evaluation unit and kebele (cluster) level.

Likelihood ratio test of inclusion/exclusion of variable in final model.

From GPS coordinates of households.

Mean kebele (cluster) coordinates extracted from Bioclim rasters (Worldclim.org).

Risk factors for trichiasis

Full univariable results for the outcome of trichiasis in those aged 15 years and older are shown in Table 6. A multivariable analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of trichiasis in this age group. Increasing age, female sex, living alone, living in a household in which adults practiced open defecation, lower altitudes, hottest maximum annual temperatures, and lower mean annual precipitation were associated with the presence of trichiasis. The full multivariable results are shown in Table 7.

Table 6. Multilevel univariable analysis of factors related to the presence of trichiasis in adults aged ≥15 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

| Variable | n | Trichiasis, % | Univariable odds ratio (95% CI)a | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | |||||

| Age, years | 15–24 | 19,622 | 0.1 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| 25–34 | 18,468 | 0.5 | 3.46 (2.20–5.30) | ||

| 35–44 | 13,122 | 1.0 | 6.73 (4.40–10.20) | ||

| 45–54 | 8204 | 2.1 | 14.34 (9.50–21.50) | ||

| 55–64 | 4913 | 3.3 | 24.32 (16.10–36.00) | ||

| ≥65 | 5152 | 4.8 | 37.90 (25.40–56.70) | ||

| Sex | M | 30,706 | 0.5 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| F | 38,775 | 1.7 | 3.36 (2.82–4.00) | ||

| Household | |||||

| Children aged 1–9 years in household, n | 0 | 32,110 | 1.5 | 1.89 (1.15–3.08) | <0.0001 |

| 1–3 | 34,809 | 0.9 | 1.15 (0.70–1.87) | ||

| ≥4 | 2562 | 0.7 | 1 | ||

| Inhabitants in householdc, n | 1 | 6643 | 2.6 | 2.59 (1.95–3.42) | <0.0001 |

| 2–5 | 47,183 | 1.2 | 1.34 (1.06–1.68) | ||

| ≥6 | 15,655 | 0.7 | 1 | ||

| Open defecation (no facilities, bush, or field) | Yes | 22,722 | 1.7 | 1.45 (1.23–1.70) | <0.0001 |

| No | 46,759 | 0.9 | 1 | ||

| Drinking source surface waterd | Yes | 11,786 | 1.4 | 1.21 (0.97–1.49) | 0.08 |

| No | 57,695 | 1.2 | 1 | ||

| Time to main source of drinking water, minutese | ≥30 | 35,285 | 1.3 | 1.00 (0.84–1.16) | 0.931 |

| <30 | 34,196 | 1.1 | 1 | ||

| Washing source surface waterd | Yes | 13,892 | 1.3 | 1.14 (0.94–1.40) | 0.1857 |

| No | 55,589 | 1.2 | 1 | ||

| Time to main source of washing watere, minutes | ≥30 | 34,367 | 1.3 | 2.14 (0.25–18.22) | 0.7839 |

| <30 | 35,054 | 1.1 | 1 | ||

| All washing at source | 60 | 1.7 | 1.00 (0.85–1.17) | ||

| Cluster-level geoclimatic | |||||

| Altitudef, m above sea level | <1500 | 8973 | 1.7 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| 1500–2499 | 54073 | 1.2 | 0.86 (0.65–1.12) | ||

| ≥2500 | 6419 | 0.7 | 0.34 (0.22–0.54) | ||

| Maximum temperature of warmest monthg, °C | <25 | 7714 | 0.7 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| ≥25 | 61767 | 1.3 | 2.35 (1.67–3.29) | ||

| Mean annual precipitationg, mm | <1000 | 12409 | 2.2 | 2.92 (2.06–4.13) | <0.0001 |

| 1000–1499 | 24357 | 1.3 | 1.83 (1.35–2.46) | ||

| ≥1500 | 32715 | 0.7 | 1 | ||

Multilevel univariable random effects regression accounting for clustering at evaluation unit and kebele (cluster) level.

Wald’s test.

Presented as binary living alone/not living alone in the final model, but displayed in further categories here for illustrative purposes.

River, dam, lake, canal.

Time for round-trip estimated by household head.

From GPS coordinates of households collected at time of survey.

Mean kebele (cluster) coordinates extracted from Bioclim rasters (Worldclim.org).

CI, confidence interval.

Table 7. Multilevel multivariable analysis of factors related to the presence of trichiasis in adults aged ≥15 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2012–2014.

| Variable | Multivariable odds ratioa | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | |||

| Age, years | 15–24 | 1.00 | <0.0001 |

| 25–34 | 3.25 | ||

| 35–44 | 7.20 | ||

| 45–54 | 15.62 | ||

| 55–64 | 24.98 | ||

| ≥65 | 41.81 | ||

| Female sex | 3.96 | <0.0001 | |

| Household | |||

| Living alone | 1.30 | <0.0001 | |

| Open defecation (no facilities, bush, or field) | 1.26 | 0.006 | |

| Cluster-level geoclimatic | |||

| Altitudec, m above sea level | <1500 | 1.00 | <0.0001 |

| 1500–2499 | 0.93 | ||

| ≥2500 | 0.50 | ||

| Maximum temperature of warmest monthd, °C | ≥25 | 1.89 | 0.0017 |

| Mean annual precipitationd, mm | <1000 | 2.55 | <0.0001 |

| 1000–1499 | 2.06 | ||

| ≥1500 | 1.00 | ||

Multilevel multivariable random effects logistic regression accounting for clustering at evaluation unit and kebele (cluster) level.

p-value from Likelihood ratio test of inclusion/exclusion of variable in final model.

Estimate from GPS coordinates of household.

Discussion

Determining the prevalences of TF and trichiasis is crucial before developing and implementing interventions for the elimination of trachoma. This survey compiled these essential baseline prevalence data for the whole of Oromia Region. EUs covering 218 out of 252 districts surveyed (87%) had TF prevalences in 1–9-year-old children ≥10%, warranting immediate implementation of the A, F and E components of SAFE, in accordance with WHO recommendations.4 EUs covering a further 14 woredas had a TF prevalence between 5.0 and 9.9%, and need a single round of antibiotic treatment, plus implementation of the F and E components of SAFE, before impact survey. Collectively, this is a huge undertaking and will require intricate coordination as well as significant funding if the blinding effects of trachoma are not to continue into the next generation in Oromia.

Younger children were at the highest risk of TF in this study. Most studies report a higher odds of TF in younger children.14–17 This may be because of improved hygiene practices with age, or partial immunity conferring a decreased risk or duration of infection or inflammatory response.18 It is possible that the pre-school age group may provide a more focused and efficient target for impact surveys in providing evidence of a diminished prevalence of trachoma for elimination programs.

In adults, the odds of trichiasis was 3.96 times higher in women than in men. This finding is in agreement with the last Ethiopian National Survey on blindness, low vision and trachoma, and other studies in Ethiopia and elsewhere; females are disproportionately affected by trichiasis.19–21 The reason for this is unclear, but may be related to increased contact with children in societies where women are the primary caregivers, or to a genetically determined propensity to a more intense immuno-inflammatory reaction to C. trachomatis infection. The strength of this association in Oromia is among the highest reported.20

In our study 37.4% of children lived in households that used open defecation, and these children were more likely to have TF than children living in a household with any form of latrine. Trachoma is commonly linked with low levels of sanitation.22–24 The link between trachoma and sanitation may be direct through enhanced density of the Musca sorbens flies thought to mechanically transmit C. trachomatis from eye to eye, or may just be an indirect metric for social deprivation, with its associated lower economic and educational opportunities overall.

We found an association between TF and increased reported time to the household’s source of water used face for washing. Trachoma has been associated with poor access to water,25,26 but is also found in areas where water is not necessarily in short supply.27–29 The volume of water used by a household has been shown to decrease markedly when the round-trip to source and back takes more than 30 minutes,30 but more distant access to water does not necessarily mean that less is used for any particular water-requiring activity. The interaction between trachoma and water access is likely to be complex, given this difference between water availability and water use, and any proposed water access interventions should clearly be paired with general health and facial hygiene education. We acknowledge that effective ways to encourage sustained behavior change, in both developing and developing countries, have so far been elusive.

We found that TF was associated with living in lower altitudes, and in drier areas. The distribution of trachoma has previously been associated with climatic and geographical factors, such as lower altitude,31,32 lower precipitation,33 and higher mean annual temperature.17,33 The cause of the relationship of these factors with trachoma is unclear, but it is likely that locations subjected to extremes of any environmental variable will be relatively sparsely populated, limiting transmission potential, and that the people who have the option to migrate from these areas would be relatively economically advantaged anyway. It is likely that these climatic associations will not be universal and will be limited to specific geographical areas. It has been suggested that these associations could be used in politically or geographically difficult environments for stratifying risk and targeting interventions,34 although more work is needed to determine when and how this type of focused approach could be used for elimination programs in stable environments.

The highly focal distribution of trachoma has been described previously.26,35–37 In keeping with this, we found that both TF and TT were highly clustered at EU, kebele and household level. Of note, despite the overall prevalence of trachoma being exceedingly high throughout most of Oromia, a group of EUs in Kelem Wellega and West Wellega Zones in the western part of the region had relatively uniformly low prevalences, while closely neighboring EUs (in areas such as Horo Guduru and East Wellega Zones) had TF prevalences amongst the highest in Oromia. Further study is warranted to identify the underlying factors associated with such steep prevalence gradients.

Both active and potentially blinding trachoma are highly prevalent in Oromia, indicating that trachoma is a significant public health problem in at least 218 woredas of the region. The high prevalence of trichiasis among women deserves urgent and special attention and suggests that programs need to ensure that the major part of their trichiasis management approach is tailored to the needs of women. Programs need to also focus on creating open-defecation-free environments and on increasing access to water as part of trachoma elimination efforts. Further study is warranted to determine why the western part of Oromia has a relatively low prevalence of TF compared to the other parts of the region.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/iope.

References

- 1.Palmer SL, Winskell K, Patterson AE, et al. “A living death”: a qualitative assessment of quality of life among women with trichiasis in rural Niger. Int Health. 2014;6:291–297. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihu054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:477–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon AW, Peeling RW, Foster A, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of trachoma. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:982–1011. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.982-1011.2004. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon A, Zondervan M, Kuper H, et al. Trachoma control: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Alliance for the Global Elimination of Blinding Trachoma by the year 2020. Progress report on elimination of trachoma, 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014;89:421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Population and Housing Census Report 2007. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berhane Y, Worku A, Bejiga A, et al. Prevalence and causes of blindness and low vision in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Dev. 2008;21:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Report of the 3rd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, 19–20 July 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:214–225. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1037401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNICEF and WHO. Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water: 2015 Update and MDG Assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, et al. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Central Statistical Agency. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census. 2007.

- 13.World Health Organization. Report on the 2nd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Geneva, 25–27 August, 2003. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey R, Duong T, Carpenter R, et al. The duration of human ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection is age dependent. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;123:479–486. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899003076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards T, Harding-Esch EM, Hailu G, et al. Risk factors for active trachoma and Chlamydia trachomatis infection in rural Ethiopia after mass treatment with azithromycin. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:556–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Last AR, Burr SE, Weiss HA, et al. Risk factors for active trachoma and ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection in treatment-naïve trachoma-hyperendemic communities of the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea Bissau. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schémann J-F, Sacko D, Malvy D, et al. Risk factors for trachoma in Mali. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:194–201. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu VH, Holland MJ, Burton MJ. Trachoma: protective and pathogenic ocular immune responses to Chlamydia trachomatis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(2):e2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berhane Y, Alemayehu W, Bejiga A. National survey on blindness, low vision and trachoma in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cromwell EA, Courtright P, King JD, et al. The excess burden of trachomatous trichiasis in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:985–992. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melese M, Alemayehu W, Worku A. Trichiasis among close relatives, central Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2004;42:255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabiu M, Alhassan M, Ejere H. Environmental sanitary interventions for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD004003. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004003.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Courtright P, Sheppard J, Lane S, et al. Latrine ownership as a protective factor in inflammatory trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:322–325. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.6.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emerson PM, Burton M, Solomon AW, et al. The SAFE strategy for trachoma control: using operational research for policy, planning and implementation. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:613–619. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.28696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabiu M, Alhassan MB, Ejere HOD, et al. Environmental sanitary interventions for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004003.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polack SR, Solomon AW, Alexander NDE, et al. The household distribution of trachoma in a Tanzanian village: an application of GIS to the study of trachoma. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ballard RC, Sutter EE, Fotheringham P. Trachoma in a rural South African community. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27(1 Pt 1):113–120. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruz AAV, Medina NH, Ibrahim MM, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in a population of the upper Rio Negro basin and risk factors for active disease. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:272–278. doi: 10.1080/09286580802080090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward B. The prevalence of active trachoma in Fiji. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;59:458–463. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(65)93746-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cairncross S, Valdmanis V. Water supply, sanitation and hygiene promotion. In: Jamison D, Breman J, Measham A, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2006. pp. 771–792. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haileselassie T, Bayu S. Altitude – a risk factor for active trachoma in southern Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2007;45:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baggaley RF, Solomon AW, Kuper H, et al. Distance to water source and altitude in relation to active trachoma in Rombo district, Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JL, Sivasubramaniam S, Rabiu MM, et al. Multilevel analysis of trachomatous trichiasis and corneal opacity in Nigeria: the role of environmental and climatic risk factors on the distribution of disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clements ACA, Kur LW, Gatpan G, et al. Targeting trachoma control through risk mapping: the example of Southern Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey R, Osmond C, Mabey DC, et al. Analysis of the household distribution of trachoma in a Gambian village using a Monte Carlo simulation procedure. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:944–951. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagi M, Schemann J-F, Mauny F, et al. Active trachoma among children in Mali: clustering and environmental risk factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(1):e583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broman AT, Shum K, Munoz B, et al. Spatial clustering of ocular chlamydial infection over time following treatment, among households in a village in Tanzania. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:99–104. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]