Abstract

Bletilla striata is a plant from the Orchidaceae family that has been employed as a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for thousands of years in China. Here, we briefly review the published studies of the last 30 years that were related to chemical constituents, pharmacologic activities, and clinical applications of B. striata. Approximately 158 compounds have been extracted from B. striata tubers with clarified molecular structures that were classified as glucosides, bibenzyls, phenanthrenes, quinones, biphenanthrenes, dihydrophenanthrenes, anthocyanins, steroids, triterpenoids, and phenolic acids. These chemicals support the pharmacological properties of hemostasis and wound healing, and also exhibit anti-oxidation, anti-cancer, anti-viral, and anti-bacterial activities. Additionally, various clinical trials conducted on B. striata have demonstrated its marked activities as an embolizing and mucosa-protective agent, and its application for use in novel biomaterials, quality control, and toxicology. It also has been widely used as a constituent of many preparations in TCM formulations, but because there are insufficient studies on its clinical properties, its efficacy and safety cannot be established from a scientific point of view. We hope that this review will provide reference for further research and development of this unique plant.

Keywords: Bletilla striata, chemical constituents, pharmacological activities, clinical application, quality control, toxicology

Introduction

Bletilla striata (Thunb.) Rchb. f. (Orchidaceae), also known as Bletillae Rhizoma, is considered to be merely an ornamental plant in Europe and the USA. However, B. striata, which is widely distributed in China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, and Myanmar, is important because of its use in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

According to the earliest pharmacopeia of TCM, Shennong’s Materia Medica Classic, Chinese scholars were the first to describe the morphologic features and medicinal value of B. striata (Hossain, 2011; Chen et al., 2018). Other Chinese pharmacopeias have recorded the effect of its astringency upon hemostasis and analgesia, as well as its use for treating traumatic bleeding, ulcers, and swelling and chapped skin (He et al., 2016). Physicians in Korea and Japan have used B. striata to treat tuberculosis, whooping cough, bleeding of the stomach/duodenal ulcers, abscesses, swellings, and parasitic diseases (Rhee et al., 1982). Several studies have revealed its uses in TCM, its chemical constituents, and medicinal properties (Yang et al., 2019).

This review summarizes current knowledge regarding the chemical composition, bioactivities, and pharmacologic effects of B. striata. We also provide a brief summary to provide insights into the TCM-based uses of B. striata, and a scientific basis for developing new medicines utilizing this interesting plant.

Chemical Constituents

The study of the chemical constituents of B. striata can be traced back to the late 19th century, but Japanese scholars began systematic research only in 1983 (Takagi et al., 1983). Studies have shown that the chemical constituents of B. striata are mainly glucosides, bibenzyls, phenanthrenes, quinones, biphenanthrenes, dihydrophenanthrenes, anthocyanins, steroids, triterpenoids, and phenolic acids. Their names (1–158) appear in Table 1 , and their structures (1–158) are shown in Figures 1 – 11 . These chemical components form the material basis for the medicinal value of B. striata.

Table 1.

List of 158 compounds isolated from B. striata.

| No. | Compound Name | Chemical Formula | Plant Part | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycosides | ||||

| 1 | dactylorhin A | C40H56O22 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 3 | gymnoside I | C21H30O11 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 4 | gymnoside II | C21H30O11 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 5 | gymnoside V | C49H62O23 | tubers | (Yan et al., 2014) |

| 6 | gymnoside IX | C51H64O24 | tubers | (Yan et al., 2014) |

| 7 | gymnoside X | C51H64O24 | tubers | (Yan et al., 2014) |

| 8 | militarine | C34H46O17 | tubers | (Han et al., 2002b) |

| 9 | bletilnoside A | C38H62O12 | roots | (Park et al., 2014) |

| 10 | bletilnoside B | C38H60O12 | roots | (Park et al., 2014) |

| 11 | 3-O-ß-D-glucopyranosyl-3-epiruscogenin | C41H60O12 | roots | (Park et al., 2014) |

| 12 | 3-O-ß-D-glucopyranosyl-3-epineoruscogenin | C41H58O12 | roots | (Park et al., 2014) |

| 13 | dancosterol | C35H60O6 | tubers | (Han et al., 2001) |

| 14 | 2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2-O-glucoside | C21H22O8 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993b) |

| 15 | 2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-O-diglucoside | C27H32O13 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993b) |

| 16 | 3,7-dihydroxy-2,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene-3-O-glucoside | C22H24O9 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993b) |

| 17 | gastrodin | C13H18O7 | fibrous roots | (Yu et al., 2016) |

| 18 | 2,7-dihydroxy-l-(4’-hydroxybenzyl)-9,10-dihydrophenan-threne-4’-O-glucoside | C28H30O9 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993b) |

| 19 | 3’-hydroxy-5-methoxybibenzyl-3-O-ß-D-glucopyranoside | C21H26O8 | tubers | (Han et al., 2002b) |

| Bibenzyls | ||||

| 20 | blestritin A | C37H36O6 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 21 | blestritin B | C30H30O6 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 22 | blestritin C | C36H34O6 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 23 | bulbocodin | C36H34O6 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 24 | bulbocodin C | C29H28O5 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 25 | bulbocodin D | C29H28O5 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 26 | bulbocol | C23H24O4 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 27 | gymconopin D | C23H24O4 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 28 | shancigusin B | C28H26O5 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 29 | shanciguol | C28H26O5 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 30 | arundinan | C22H22O3 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 31 | arundin | C29H28O4 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 32 | batatasin III | C15H16O3 | tubers | (Woo et al., 2014) |

| 33 | gigantol | C16H18O4 | tubers | (Woo et al., 2014) |

| 34 | 3,4’-dihydroxy-5,3’,5’-trimethoxybibenzyl | C17H20O5 | tubers | (Woo et al., 2014) |

| 35 | 3,3’-dihydroxy-5,4’-dimethoxybibenzyl | C16H18O4 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 36 | 3’-O-methylbatatasin III | C15H18O3 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 37 | 3,3’-dihydroxy-4-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-5-methoxybibenzyl | C22H22O4 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1993) |

| 38 | 3,3’-dihydroxy-2-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-5-methoxybibenzyl | C22H22O4 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1993) |

| 39 | 3’,5-dihydroxy-2-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-3-methoxybibenzyl | C22H22O4 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1993) |

| 40 | 2’,6’-bis(p-hydroxybenzyl)-5-methoxybibenzyl-3,3’-diol | C33H36O5 | tubers | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| 41 | 2,6-bis(p-hydroxybenzyl)-5,3’-dimethoxybibenzyl-3-ol | C30H30O5 | tubers | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| 42 | 3,3’-dihydroxy-5-methoxy-2,5’,6-tris(p -hydroxybenzyl) bibenzyl | C46H44O11 | tubers | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| 43 | 3,3’,5-trimethoxybibenzyl | C17H20O3 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1991) |

| 44 | 3,5-dimethoxybibenzyl | C16H18O2 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1991) |

| 45 | 5-hydroxy-4-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-3’,3-dimethoxybibenzyl | C23H24O4 | tubers | (Han et al., 2002a) |

| 46 | 3,3’-dihydroxy-5-methoxybibenzyl | C15H16O3 | tubers | (Han et al., 2002c) |

| 47 | 5-hydroxy-2-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-3-methoxybibenzyl | C22H22O3 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| Phenanthrenes | ||||

| 48 | 4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | C15H12O3 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 49 | 3,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | C16H14O4 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 50 | 2,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene-3,7-diol | C16H14O4 | tubers | (Feng et al., 2008) |

| 51 | 3,5-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | C16H14O4 | tubers | (Xiao et al., 2016) |

| 52 | 1,5-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | C16H14O4 | tubers | (Xiao et al., 2016) |

| 53 | 2,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene-7-ol | C15H14O3 | tubers | (Xiao et al., 2016) |

| 54 | 2,4,7-trimethoxyphenanthrene | C17H16O3 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1991) |

| 55 | 2,3,4,7-tetramethoxyphenanthrene | C18H18O4 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1991) |

| 56 | 1,8-bis(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | C29H24O5 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1991) |

| 57 | 1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4,8-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | C23H20O5 | tubers | (Morita et al., 2005) |

| 58 | 1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol | C22H18O4 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1990) |

| 59 | 2-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxyphenanthrene | C16H14O3 | fibrous roots | (Yu et al., 2016) |

| 60 | 3,7-dihydroxy-2,4,8-trimethoxyphenanthrene | C17H16O5 | tubers | (Woo et al., 2014) |

| 61 | 2,7-dihydroxy-3,4-dimethoxyphenanthrene | C16H14O4 | tubers | (Han et al., 2002c) |

| 62 | 1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4,7-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2-ol | C23H20O4 | tubers | (Xiao et al., 2017) |

| 63 | 1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4,7-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,8-diol | C23H20O5 | tubers | (Xiao et al., 2017) |

| 64 | 1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4,7-dimethoxyphenanthrene-2,6-diol | C23H20O5 | tubers | (Xiao et al., 2017) |

| 65 | bleformin B | C23H20O5 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 66 | blespirol | C25H18O5 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993b) |

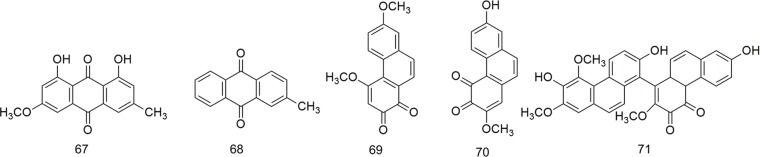

| Quinones | ||||

| 67 | 1,8-dihydroxy-3-methoxy-6-methylanthracene-9,10-dione | C16H12O5 | tubers | (Wang et al., 2001) |

| 68 | 2-methylanthraquinone | C15H10O2 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016c) |

| 69 | 4,7-dimethoxyphenanthrene-1,2-dione | C16H13O4 | tubers | (Xiao et al., 2016) |

| 70 | 7-hydroxy-2-methoxyphenanthrene-3,4-dione | C15H13O4 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016a) |

| 71 | 3’,7’,7-trihydroxy-2,2’,4’-trimethoxy-[1,8’-biphenanthrene]-3,4-dione | C31H23O8 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016a) |

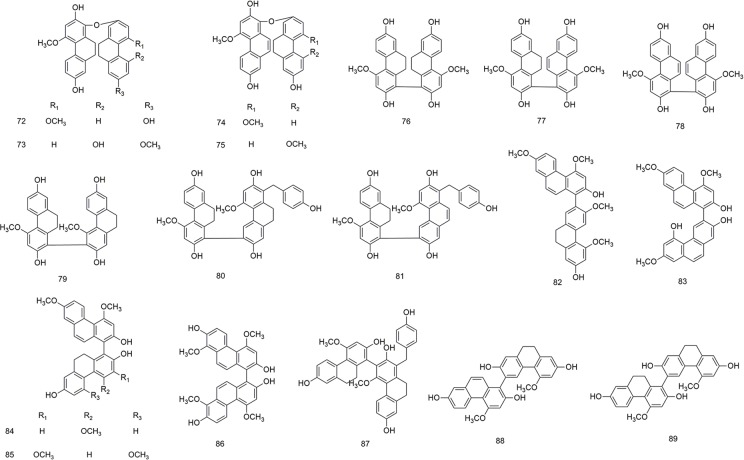

| Biphenanthrenes | ||||

| 72 | blestrin A | C30H26O6 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1990) |

| 73 | blestrin B | C30H26O6 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1990) |

| 74 | blestrin C | C30H24O6 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1992) |

| 75 | blestrin D | C30H24O6 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1992) |

| 76 | blestriarene A | C30H26O6 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1989) |

| 77 | blestriarene B | C30H24O6 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1989) |

| 78 | blestriarene C | C30H22O6 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1989) |

| 79 | blestrianol A | C30H26O6 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1991) |

| 80 | blestrianol B | C37H32O7 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1991) |

| 81 | blestrianol C | C37H30O7 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1991) |

| 82 | 4,7,3’5’-tetramethoxy-9’,10’-dihydro-[1,2’-biphenanthrene]-2,7’-diol | C32H27O6 | fibrous roots | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| 83 | 4,7,7’-trimethoxy-9’,10’-dihydro-[1,3’-biphenanthrene]-2,2’,5’-triol | C31H25O6 | fibrous roots | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| 84 | 4,7,4’-trimethoxy-9’,10’-dihydro-[1,1’-biphenanthrene]-2,2’,7’-triol | C31H25O6 | fibrous roots | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| 85 | 4,7,3’,5’-tetramethoxy-9’,10’-dihydro-[1,1’-biphenanthrene]-2,2’,7’-triol | C32H27O7 | fibrous roots | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| 86 | 4,8,4’,8’-tetramethoxy-[1,1’-biphenanthrene]-2,7,2’,7’-tetrol | C32H26O8 | fibrous roots | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| 87 | bleformin D | C37H32O7 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 88 | 4,4’-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydro-[6,1’-biphenanthrene]-2,7,2’,7’-tetraol | C30H24O6 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 89 | gymconopin C | C30H26O6 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

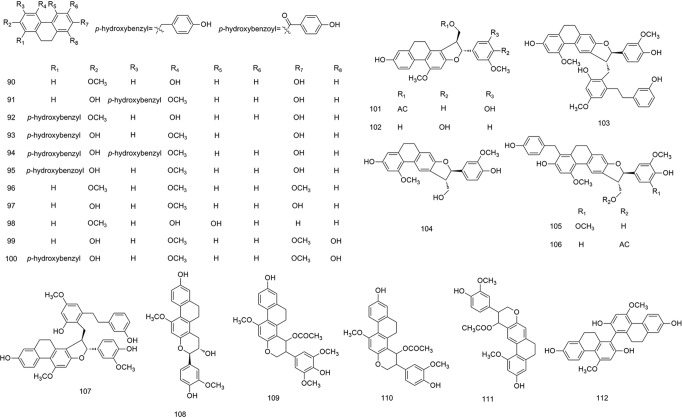

| Dihydrophenanthrenes | ||||

| 90 | 4,7-dihydroxy-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C15H14O3 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1990) |

| 91 | 2,7-dihydroxy-3-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C22H20O4 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1990) |

| 92 | 4,7-dihydroxy-1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C22H20O4 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1990) |

| 93 | 2,7-dihydroxy-1,6-bis(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C29H26O5 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1990) |

| 94 | 2,7-dihydroxy-l,3-bis(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C29H26O5 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1993) |

| 95 | 2,7-dihydroxy-l-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C22H20O4 | tubers | (Bai et al., 1993) |

| 96 | 2,4,7-trimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C17H18O3 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1991) |

| 97 | 2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C15H14O3 | tubers | (Han et al., 2002c) |

| 98 | 4,5-dihydroxy-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C15H14O3 | fibrous roots | (Yu et al., 2016) |

| 99 | 2,8-dihydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C15H14O3 | tubers | (Woo et al., 2014) |

| 100 | 2,8-dihydroxy-1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-4,7-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | C23H22O5 | tubers | (Woo et al., 2014) |

| 101 | pleionesin C | C27H26O7 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

| 102 | (2,3-trans)-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxymethyl-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-phenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-ol | C25H24O6 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

| 103 | bleochranol A | C40H38O8 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

| 104 | bleochranol B | C25H24O6 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

| 105 | bleochranol C | C33H32O8 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

| 106 | bleochranol D | C34H32O8 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

| 107 | (2,3-trans)-3-[2-hydroxy-6-(3-hydro-xyphenethyl)-4-methoxybenzyl]-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydrophenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-ol | C40H38O8 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

| 108 | shanciol | C25H24O6 | tubers | (Ma et al., 2017) |

| 109 | bletlos A | C28H28O8 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993a) |

| 110 | bletlos B | C27H26O7 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993a) |

| 111 | bletlos C | C27H26O | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1993a) |

| 112 | blestriaren A | C30H26O6 | rhizomes | (Li et al., 2008a) |

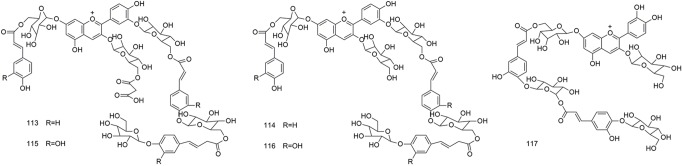

| Anthocyanins | ||||

| 113 | Bletilla anthocyanin 1 | C75H81O40 | flowers | (Saito et al., 1995) |

| 114 | Bletilla anthocyanin 2 | C72H79O37 | flowers | (Saito et al., 1995) |

| 115 | Bletilla anthocyanin 3 | C75H81O43 | flowers | (Saito et al., 1995) |

| 116 | Bletilla anthocyanin 4 | C72H79O40 | flowers | (Saito et al., 1995) |

| 117 | 3-O-(ß-glucopyranoside)-7-O-[6-O-(4-O-(6-O-(4-O-(ß-glucopyranosyl)-trans-caffeoyl)-ß-glucopyranosyl)-trans-caffeoyl)-ß-glucopyranoside] | C57H63O32 | flowers | (Tatsuzawa et al., 2010) |

| Steroids | ||||

| 118 | ß-sitosterol | C29H50O | tubers | (Han et al., 2001) |

| 119 | ß-sitosterol palmitate | C45H80O2 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1997) |

| 120 | stigmasterol | C29H48O | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016c) |

| 121 | stigamasterol palmitate | C45H78O2 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1997) |

| 122 | 3-epiruscogenin | C27H42O4 | roots | (Park et al., 2014) |

| 123 | 3-epineoruscogenin | C27H40O4 | roots | (Park et al., 2014) |

| 124 | (20S,22R)-1ß,2ß,3ß,4ß,5ß,7α-hexahydroxyspirost-25(27)-en-6-one | C27H35O9 | roots | (Park et al., 2014) |

| 125 | (1α,3α)-1-O-[(ß-D-xylopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl)]-3-O-D-glucopyranosyl-5α-spirostan | C44H71O17 | roots | (Wang and Meng 2015) |

| 126 | (1α,3α)-1-O-[(ß-D-xylopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl)oxy]-3-O-D-glucopyranosyl-25(27)-ene-5α-spirostan | C44H69O17 | roots | (Wang and Meng 2015) |

| 127 | (1α,3α)-1-O-[(ß-D-xylopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl)oxy]-epiruscogenin | C38H59O12 | roots | (Wang and Meng 2015) |

| 128 | (1α,3α)-1-O-[(ß-D-xylopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl)oxy]-epineoruscogenin | C38H57O12 | roots | (Wang and Meng 2015) |

| Triterpenoids | ||||

| 129 | cyclomargenol | C32H54O | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1997) |

| 130 | cyclomargenone | C32H53O | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1997) |

| 131 | cycloneolitsol | C32H54O | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1997) |

| 132 | cyclobalanone | C32H53O | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1997) |

| 133 | 24-methylenecycloartanol palmitate | C47H81O2 | tubers | (Yamaki et al., 1997) |

| 134 | cyclolaudenol | C31H51O | tubers | (Yang et al., 2014) |

| 135 | cyclolaudenone | C31H50O | tubers | (Yang et al., 2014) |

| 136 | 3ß-hydroxyoleane-12-en-28-oic acid 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-ß-D-glucopyranoside | C41H55O12 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016b) |

| Phenolic acids | ||||

| 137 | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | tubers | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| 138 | protocatechuic acid | C7H6O4 | tubers | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| 139 | cinnamic acid | C9H8O2 | tubers | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| 140 | caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | tubers | (Han et al., 2001) |

| 141 | 2-hydroxysuccinic acid | C4H5O5 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016b) |

| 142 | palmitic acid | C16H32O2 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016b) |

| 143 | syringaresinol | C22H26O8 | tubers | (Han et al., 2001) |

| 144 | pinoresinol | C20H22O6 | tubers | (Bae et al., 2016) |

| 145 | 3’’-methoxynyasol | C18H17O3 | tubers | (Bae et al., 2016) |

| 146 | p-hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H6O2 | tubers | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| 147 | ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | tubers | (Yu et al., 2011) |

| 148 | 3-hydroxycinnamic acid | C9H8O3 | tubers | (Yu et al., 2011) |

| Others | ||||

| 149 | 4-hydroxybenzylamine | C7H9NO | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016b) |

| 150 | 4,4’-dihydroxydiphenylmethane | C13H12O2 | tubers | (Yan et al., 2014) |

| 151 | 4,4’-dihydroxybenzyl sulfide | C14H14SO2 | tubers | (Yan et al., 2014) |

| 152 | 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde | C6H6O3 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016c) |

| 153 | striatolide | C18H30O3 | tubers | (Yan et al., 2014) |

| 154 | schizandrin | C24H32O7 | tubers | (Han et al., 2002a) |

| 155 | brugnanin | C56H90O8 | tubers | (Sun et al., 2016c) |

| 156 | bletillanol A | C18H21O5 | tubers | (Bae et al., 2016) |

| 157 | bletillanol B | C18H20O5 | tubers | (Bae et al., 2016) |

| 158 | tupichinol A | C17H18O4 | tubers | (Bae et al., 2016) |

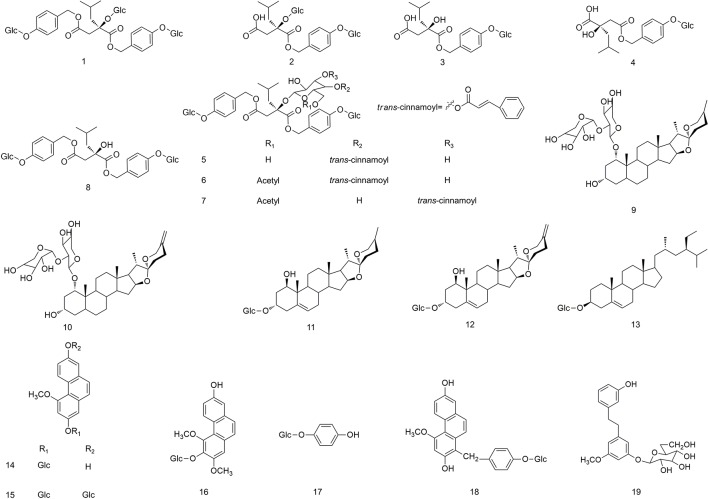

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of glycoside compounds (1–19) isolated from B. striata.

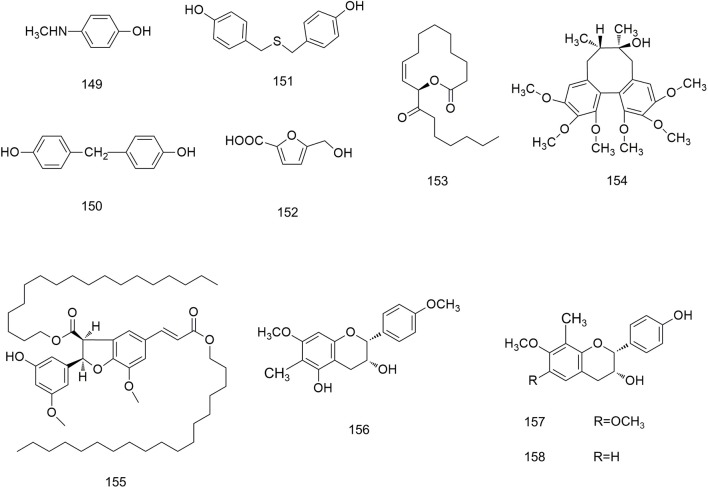

Figure 11.

Chemical structures of other compounds (149–158) isolated from B. striata.

Glycosides

Glycosides are an important class of compounds in B. striata ( Figure 1 ), of which polysaccharides are relatively abundant in its dried tubers. B. striata contains various natural monosaccharide compounds (1–19). Bletilla striata polysaccharide (BSP) is a high-molecular-weight, viscous polysaccharide, whose chemical composition is glucomannan (which comprises D-glucose and D-mannose) (Liu et al., 2013).

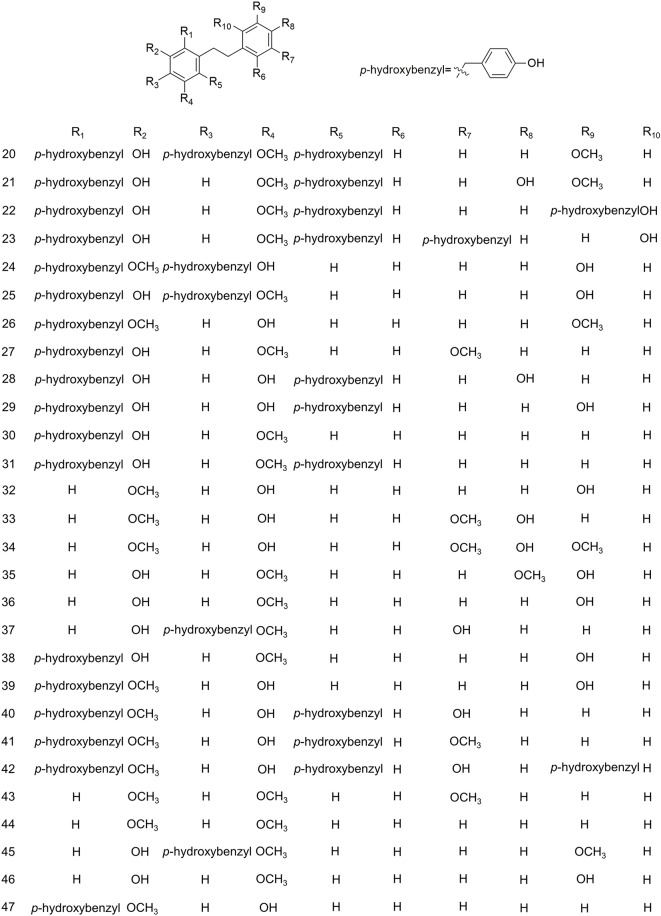

Bibenzyls

Although the skeleton of bibenzyl compounds is simple, the bridge chain substituents attached to the aromatic ring are diverse. This scenario leads to various structural types and, thus, to various biologic activities (Dai and Sun, 2008). The structure of bibenzyl compounds is unique, and this is of considerable practical importance for finding benzyl compounds with potential medicinal value. B. striata is rich in benzyl compounds (20–47), containing 28 types, as shown in Figure 2 .

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of bibenzyls (20–47) isolated from B. striata.

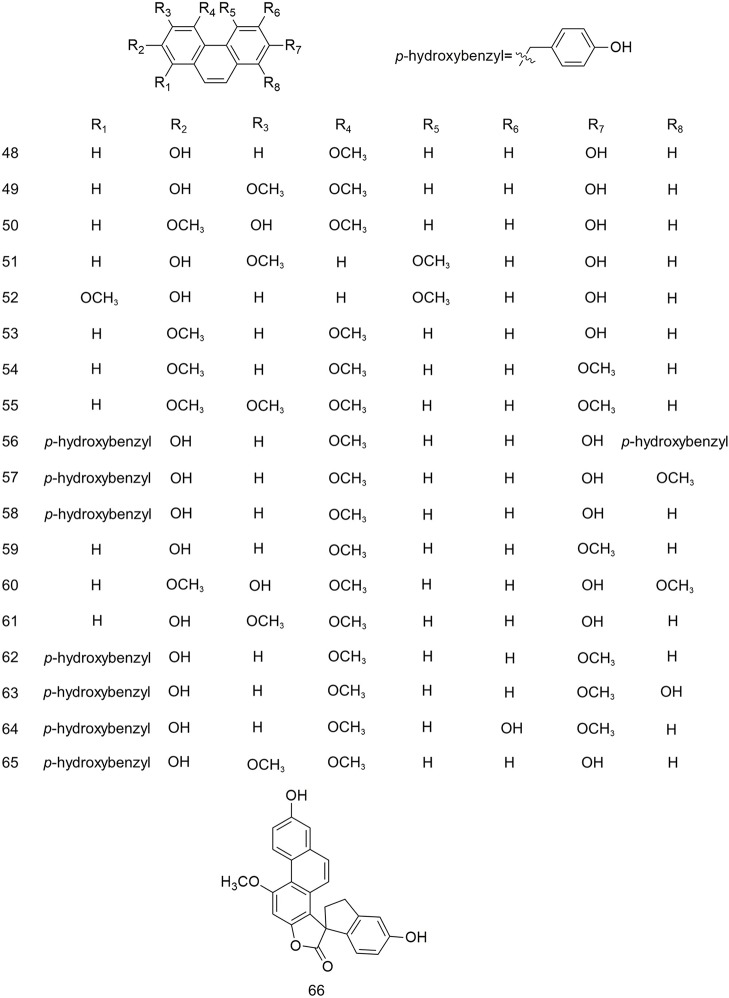

Phenanthrenes

Several studies have reported that phenanthrenes are present in B. striata. The substituents on the aromatic rings are mainly methoxy, hydroxyl, and p-hydroxybenzyl groups, as shown in Figure 3 .

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of phenanthrenes (48–66) isolated from B. striata.

Quinones

Benzoquinones, naphthoquinones, anthraquinones, and phenanthraquinones are commonly found in plants used for TCM. Five types of quinones have been isolated from B. striata, including anthraquinones (67–68) and phenanthraquinones (69–71), whose structures are shown in Figure 4 .

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of quinones (67–71) isolated from B. striata.

Biphenanthrenes

Due to their axial asymmetry and asymmetric induction, biphenanthrene compounds exhibit important characteristic absorption in the infrared region at 1620–1480 cm−1 and 900–650 cm−1 (Tang et al., 2014). The biphenanthrene compounds in B. striata are composed of two simple phenanthrenes or dihydrophides, as shown in Figure 5 .

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of biphenanthrenes (72–89) isolated from B. striata.

Dihydrophenanthrenes

Dihydrophenanthrenes, phenanthrenes, and benzyls are stilbenoids with an identical 1,2-distyrene skeleton. The substituents on their aromatic rings are mainly hydroxyl, methoxy, and p-hydroxybenzyl groups (Lin et al., 2005). In the ultraviolet spectrum, dihydrophenanthrene compounds, in general, have an α band at approximately 310 nm, a β band at approximately 250 nm, and a ρ band at approximately 280 nm. The skeleton of dihydrophenanthrenes can be synthesized in the phenylpropane metabolic pathway using phenolic compounds (Gu et al., 2013). The structures of dihydrophenanthrenes are shown in Figure 6 .

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of dihydrophenanthrenes (90–112) isolated from B. striata.

Anthocyanins

Anthocyanins are the main pigments that give flowers their color. The flowers of B. striata are not commonly used in TCM, and therefore, few studies have been conducted on these flowers. Only five compounds (113–117) have been isolated from the flowers of B. striata. However, recent studies have shown that the anthocyanins in plants may affect human health (Stintzing and Carle, 2004), and have provided new material to study the medicinal uses of B. striata. The structures of anthocyanins are shown in Figure 7 .

Figure 7.

Chemical structures of anthocyanins (113–117) isolated from B. striata.

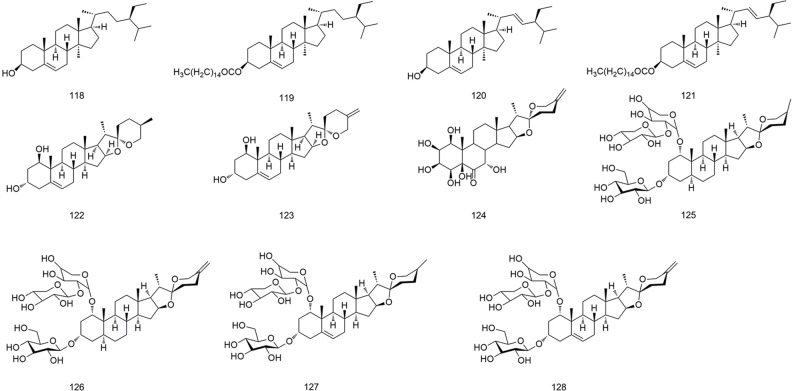

Steroids

All steroids are biosynthesized from mevalonic acid (Debieu et al., 1992). The steroids present in B. striata are complex, with diverse structures and many derivatives. Eleven steroids and their derivatives (118–128) have been isolated from B. striata, and their structures are shown in Figure 8 .

Figure 8.

Chemical structures of steroids (118–128) isolated from B. striata.

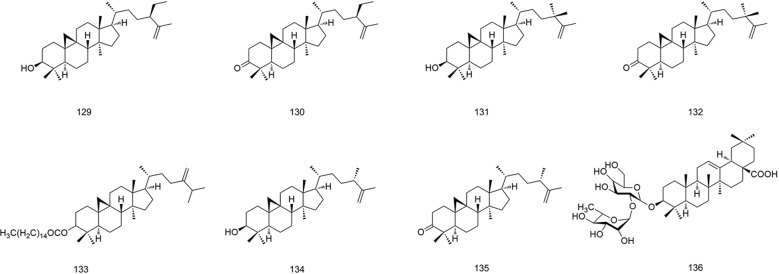

Triterpenoids

Triterpenoids are widespread in plants. They are mostly tetracyclic and pentacyclic, but a few are monocyclic, bicyclic, and tricyclic (Liou and Wu, 2002). The triterpenoids isolated from B. striata have mainly tetracyclic triterpene structures (129–135), but also include a pentacyclic triterpene branched diglycoside compound (136). Their structures are shown in Figure 9 .

Figure 9.

Chemical structures of triterpenoids (129–136) isolated from B. striata.

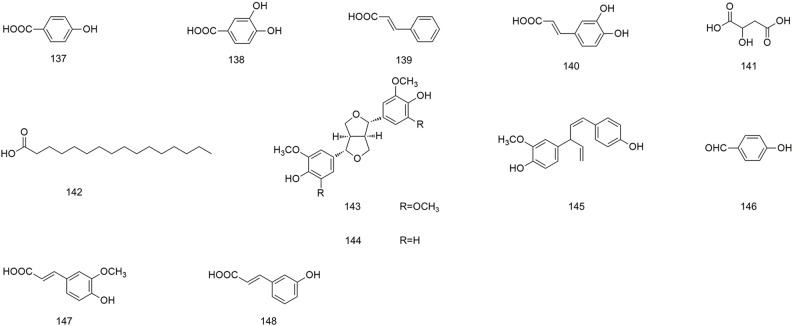

Phenolic Acids

Phenolic acids are organic acids containing phenol rings, hydroxybenzoic acids, and hydroxycinnamic acids. They are important secondary metabolites in plants because of the protection they offer against insects, viruses, and bacteria (Heleno et al., 2015). Consumption of phenolic acid-rich food could assist with accelerating the elimination of oxygen free radicals in the body, which would protect cells (Bae et al., 2016). Twelve phenolic acids (137–148) have been obtained from B. striata, and their structures are shown in Figure 10 .

Figure 10.

Chemical structures of phenolic acids (137–148) isolated from B. striata.

Other Compounds

In addition to the compounds stated above, other compounds from B. striata with different structures (149–158) have been reported. Their structures are shown in Figure 11 .

Pharmacologic Activities

The basic research of TCM focuses mainly on chemical composition and pharmacology, of which the latter is the most important. Pharmacologic studies on B. striata have mainly focused on pharmacokinetics. The latter advances our understanding of the mechanism of action of B. striata components. In recent years, pharmacologic studies on B. striata have focused mainly on its hemostatic, wound-healing, anti-oxidative, anti-cancer, antiviral, and antibacterial activities.

Hemostasis

Hemostasis is a process that causes bleeding to stop (i.e., blood is retained within a damaged blood vessel). The hemostatic effect is one of the main pharmacologic effects of B. striata. Bensky and colleagues showed that when the dried powder of B. striata tubers was mixed with water, it could achieve a good hemostatic effect after it was spread onto a wound (Venkatraja et al., 2012). Interestingly, recent studies have shown that the water-soluble portion of B. striata has an active role in hemostasis, and its function is believed to be related to adenosine diphosphate, which promotes and accelerates platelet aggregation (Lu et al., 2005; Gachet, 2006). Hung and Wu found that BSP in this water-soluble component played a key role in hemostatic activity (Hung and Wu, 2016). Indeed, there has recently been intensive research on the procoagulant function of BSP.

Blood coagulation is a process in which a series of coagulation factors is successively activated by enzymatic action to produce thrombin and fibrinogen clots. Animal experiments have shown that BSP can participate in multiple hemostasis processes, such as platelet adherence to the subendothelial matrix to block vessels (primary hemostasis), and the formation of fibrin clots (secondary hemostasis) by activation of various coagulation factors and promotion of thromboxane-A2 synthesis (Dong et al., 2014). Because of its obvious and non-toxic hemostatic effect, BSP has been developed as a new type of hemostatic agent that can be used as a drug delivery vehicle and wound dressing (Zhang et al., 2017a). BSP can be combined with other materials to develop new biomedical materials, such as hemostatic materials for surgical treatments (Wang et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019).

In addition to BSP, the steroids (123, 125–128) in B. striata exhibit obvious hemostatic activity and can significantly reduce clotting time (Yamaki et al., 1990). The hemostatic effect of this type of composition may be related to platelets, blood clotting, and fibrinolysis (Zhao et al., 2016).

Wound Healing

Wound healing has three main phases: inflammation, proliferation of granulation tissue, and repair (Kasuya and Tokura, 2014). Antioxidants in plants, such as polysaccharides and phenolic compounds, have important roles in these three phases (Süntar et al., 2012).

In the inflammation phase, BSP promotes the expression of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and interferon (IFN)-γ (Diao et al., 2008). As downstream effector molecules of the toll-like receptor-4/lipopolysaccharide (TLR4/LPS) signaling pathway, TNF-α and IL-1β are mediators of the inflammatory response. They have similar effects and can activate various inflammatory cells (Cunha et al., 2007). Also, IFN-γ enhances the expression of major histocompatibility complex class-II molecules on macrophage surfaces to improve their ability to present antigens (Baldridge et al., 2010). Additionally, it was found that a BSP solution (11 μM) increased the nitric oxide (NO) concentration in a wound, which would promote the chemotaxis of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, thereby providing adequate conditions for wound repair (Diao et al., 2008). NO can also regulate the diameter of and flow within blood vessels so that the wound obtains a more generous blood supply, which helps to repair the wound and advance the growth of new blood vessels. Studies have indicated that BSP can promote the cleanliness of necrotic tissue and provide conditions for subsequent tissue regeneration in a wound (Huang et al., 2019).

In the phases based on the proliferation of granulation tissue and repair, BSP can control the expression of pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., TNF-α) at an appropriate level, reduce the inflammatory reaction in the wound, and prevent damage to remaining cells (Lou et al., 2010). In addition, BSP promotes an increase in the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), as well as the synthesis and release of hydroxyproline. These actions promote the growth of epithelial cells, accelerate fibroblast proliferation, and further promote healing by wound contraction (Wang et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2011).

Apart from BSP, several phenolic acids (137–138, 140, 146–148) in B. striata are thought to promote wound healing (Song et al., 2017). Yang and colleagues reported that the esterification products of caffeic acid (140) and phenylethyl alcohol can inhibit the transforming growth factor-β1/Mothers against the decapentaplegic homolog 3 (TGF-β1/Smad3) signaling pathway (Yang et al., 2017). There is evidence that Smad3 can bind the DNA sequences of target genes at the transcriptional level, and, for pathologic skin conditions, assumes important roles in tissue repair and fibrosis (Ashcroft et al., 1999). Also, the degradation product of protocatechuic acid (138) can regulate high mobility group box (HMGB)1 expression by modulating the HMGB1/receptor for the advanced glycation end products (RAGE) pathway (Zhang et al., 2015). During wound healing, classically activated macrophages can utilize HMGB1 to attract vessel-associated stem cells (e.g., endothelial progenitor cells, vascular progenitor cells, smooth muscle progenitor cells), which contribute to skin healing and angiogenesis (Lolmede et al., 2009).

Anti-Oxidation

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have dual biologic effects. These are necessary to maintain cellular homeostasis during normal activities, but they also damage macromolecular matter. ROS over-accumulation results in cell death, can lead to multiple diseases, and accelerates the aging of the human body (Mittler, 2002). It is advantageous that various chemical constituents in plants can be used as natural antioxidants to remove free radicals in the body without the need for catalase, peroxidase, or superoxide dismutase (Grant and Loake, 2000).

Assays based on the scavenging of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals have shown that the fibrous root parts and pseudobulb parts of B. striata exhibit strong free radical-scavenging activity. Indeed, the partial antioxidant capacity of chloroform subfractions from ethanol extracts of the fibrous roots of B. striata was the strongest (half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) = 0.848 mg/L). Simultaneously, because the fibrous root parts contain more total phenols, they showed stronger reducing ability (reducing power RP0.5AU = 83.68 mg/L) (Jiang et al., 2013).

BSP has been shown to be a natural antioxidant through various antioxidant test systems (DPPH, 2,2’-azino-bis, ferric-reducing antioxidant power). The antioxidative effects of BSP are mediated through the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 (NOX4)/p22phox signaling pathway (Qu et al., 2016). Through this signaling pathway, BSP can inhibit expression of NOX4 and p22phox, thereby blocking angiotensin II-induced ROS generation (Yue et al., 2016). Furthermore, ferulic acid (147) in B. striata shows favorable free radical-scavenging ability, and its reducing ability is even stronger than that of vitamin C (Zhao et al., 2010). This antioxidant ability can protect cells from oxygen species-mediated DNA damage and radiation-induced free radicals (Srinivasan et al., 2006). The NOX4/ROS-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is the one through which ferulic acid (147) can decrease ethanol-induced ROS accumulation to improve anti-apoptotic responses (Li et al., 2017).

In some cases, antioxidants can worsen oxidative stress (Miller et al., 2005). If an antioxidant effect is observed, trace ROS are important cellular messengers of molecular signaling. Excessive clearance of ROS may lead to redox imbalance and induce cell-signaling disturbances, thereby triggering oxidative systems in the body.

Anti-Cancer

The anti-cytotoxic activity of synthetic drugs can strengthen some of the medicinal effects of B. striata, especially efficacy against cancer-related diseases. Glycosides (9–12), bibenzyls (30, 32–34, 38–41), phenanthrenes (57), quinines (70–71), dihydrophenanthrenes (90, 94, 98, 100–103, 105–107, 112), steroids (125–128), and triterpenoids (136) from B. striata have been reported to show inhibitory activities against various tumor cell lines in vitro: HepG2, MCF-7, HT-29, A549, BGC-823, HL-60, MCF-7, SMMC-7721, W480, SK-OV-3, SK-MEL-2, and HCT-15. Their names and anti-cancer activities are listed in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Anti-cancer activities of B. striata.

| Aspects | Compound No. | Tumor Cell | Anti-Tumor Activity Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directly | 100 | HCT-15 | Inhibit growth of tumor | (Woo et al., 2014) |

| 90, 98 | HepG2 | Arrest the cells at G2/M phase | (Wang et al., 2017) | |

| 39, 40 | K562 | Cell cycle arrest | (Morita et al., 2005) | |

| 70, 71 | MCF-7, HT-29, A549 | Induce apoptosis | (Sun et al., 2016a) | |

| 136 | A549 | Arrest the cells at G0 phase | (Sun et al., 2016c) | |

| 12, 125–128 | A549, BGC-823, HepG2, HL-60, MCF-7, SMMC-7721,W480 | Inhibit growth of tumor | (Wang and Meng, 2015) | |

| 9–11 | A549, SK-OV-3, SK-MEL-2, HCT-15 | Inhibit growth of tumor | (Wang and Meng, 2015) | |

| 30, 38, 40-41, 101-103, 105-107, 112 | HL-60, SMMC-7721, A549, MCF-7, W480 | Inhibit growth of tumor | (Li et al., 2008a) | |

| Indirectly | 40, 59, 94 | K562 | Reverse tumor multidrug resistance | Morita et al., 2005 |

Woo and colleagues revealed that compound (100) exhibited growth inhibition against a human colon cancer cell line (HCT-15), with an IC50 of 2.16 μM (Woo et al., 2014). Compounds (90, 98) isolated from B. striata tubers showed potent inhibition of proliferation of human hepatoma cells (HepG2), with an IC50 of 29.1 μM and 25.5 μM, respectively. In HepG2 cells, these two dihydrophenanthrenes induced apoptosis by downregulating the expression of cyclin B1 and blocking the cell cycle in the G2/M phase (Wang et al., 2017). Compounds (40, 57, 94) were shown to sensitize K562/breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) cells to the metabolically active product camptothecin, SN-38, by inhibiting the function of BCRP cells, thereby demonstrating that they could alter multidrug resistance in cancer treatment (Morita et al., 2005). Compounds (39, 40) inhibited tubulin polymerization at an IC50 of 10 μM, and they limited cell growth by interfering with the mitosis of tumor cells (Morita et al., 2005). Compounds (70–71) exhibited significant cytotoxic effects against the MCF-7, HT-29, and A549 lines. After MCF-7 cells underwent treatment, the IC50 for compounds (70–71) was 18.49 μg/ml and 12.64 μg/ml, which are greater values than that for cisplatin. Interestingly, their anti-cancer activity is related to their pro-oxidative activity.

These compounds can block the G0/G1 phase via a ROS-mediated mechanism that ultimately leads to apoptosis (Sun et al., 2016a). Compound (136) has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells in the same manner by blocking the G0/G1 phase (Sun et al., 2016c). The IC50 for compounds (12, 125–128) against A549, BGC-823, HepG2, HL-60, MCF-7, SMMC-7721, and W480 cells ranged from 11.3 μM to 32.2 μM, a range that is similar to that for doxorubicin (Wang and Meng, 2015). Compounds (9–11) showed significant cytotoxicity against A549, SK-OV-3, SK-MEL-2, and HCT-15 cells, with IC50 ranging from 3.98 μM to 12.10 μM (Wang and Meng, 2015). Compounds (30, 38, 40–41, 101–103, 105–107, 112) showed significant cytotoxicity against HL-60, SMMC-7721, A549, MCF-7, and W480 cells with IC50 ranging from 0.24 μM to 38.56 μM (Li et al., 2008a). Among them, compound (103) showed stronger cytotoxicity than cisplatin against the cell lines mentioned above.

In addition to the monomeric compounds stated above, BSP is also considered to have anti-cancer activity (Zhang et al., 2019b). Qian and colleagues showed that, compared with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) alone, better results were obtained when the hepatocellular carcinoma in ACI rats was treated with a combination of TACE and arterial administration of BSP (Qian et al., 2003). BSP also inhibited the proliferation of HepG2 cells in a weak manner, and the division of HepG2 cells was not inhibited at <1.5 mg/ml. BSP can also induce apoptosis through caspase-3 expression (Liu et al., 2018). Using BSP as a drug carrier or mixing chemotherapeutic drugs with BSP is another anti-cancer strategy. In this manner, the drug concentration in the target organ can be maintained at a particular level. Based on this idea, copolymer micelles have been used in cancer chemotherapy (Wang et al., 2019). A macromolecular substance consisting of stearic acid-modified BSP as a carrier of docetaxel was created, and had a more pronounced effect on inhibiting the growth of HepG2 and HeLa cancer cells compared with that of docetaxel injection alone (Guan et al., 2017).

Antiviral

The efficacy of several first-line antiviral agents appears to be diminishing (Ruiz and Russell, 2012). The antiviral effect of some traditional Chinese herbs (e.g., Isatis tinctoria) has been demonstrated by experimental and clinical research (Li and Peng, 2013). The active pharmaceutical ingredient in these plants can be used as the lead compound for further structural optimization to develop new antiviral drugs that can strengthen the immune system to fight and eliminate viral infections.

B. striata can exert antiviral activity by (i) interfering with the surface proteins of viruses to reduce cell infection and inhibit virus invasion into tissue; (ii) interfering with the RNA replication of the invading viruses to inhibit viral proliferation in the body; and (iii) preventing the virus from being released from host cells, thereby reducing viral spread (Shi et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017b). The water and ethanol extracts of B. striata avert invasion by the influenza virus by interfering with the hemagglutinin receptor on Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, and viral inhibition increases with the extract concentration, with an IC50 of 18.3 mg/ml and 235.7 μg/ml, respectively, being recorded (Zhang et al., 2017b). Various compounds (53, 84–86, 88, 90, 97–98) in B. striata also show different levels of antiviral activity. Most of them have been shown to have significant antiviral activity against the H3N2 virus in an embryonated hen-egg model, with inhibition ranging from 17.2% to 79.3% (Shi et al., 2017).

B. striata can also assist the immune system of the human body to indirectly exert antiviral activity. Peng and colleagues investigated the immunomodulatory activity of BSPF2, which is a new polysaccharide identified from B. striata. BSPF2 significantly induced spleen cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Peng et al., 2014). The spleen can produce lymphocytes, macrophages, and various cytokines, and has an important role in the immune system. Animal experiments have demonstrated that B. striata can promote T-cell and B-cell immunity in immunocompromised mice (Qiu et al., 2011).

Antibacterial

The use of phytochemicals could solve the problems of drug-resistant strains and antibiotic shortages. Phytochemicals are safe, low-toxicity agents with important bacteriostatic functions (Barbieri et al., 2017).

Testing of the antibacterial activity of B. striata has revealed that bibenzyls (40, 42) and biphenanthrenes (76–78, 83–86) are active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Their names and antibacterial activities are listed in Table 3 . Compound (84) exhibited potential activity against Staphylococcus aureus American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 29213, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) ATCC 43300, and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2–8 µg/ml. Scanning electron microscopy showed that compound (84) killed bacterial cells by damaging their cytoplasmic membranes (Chen et al., 2018). Compounds of 78 and 83–86, with a MIC of 2 μg/ml and 64 μg/ml, were active against six Gram-positive bacteria: S. aureus ATCC 25923, 29213, 43300, Staphylococcus epidermidis Center for Medical Culture Collections (CMCC) 26069, E. faecalis ATCC 29212, and Bacillus subtilis China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) 1.1470 (Qian et al., 2015). Blestriarene A (76), blestriarene B (77), and blestriarene C (78) showed activity against S. aureus ATCC 25923 at MIC of 12.5–50 mg/ml, against S. epidermidis ATCC 26069 at MIC of 25–50 mg/ml, and against B. subtilis ATCC 6633 at MIC of 25 mg/ml (Yang et al., 2012). Compound (40) exhibited in vitro activity against Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778 and S. aureus ATCC 25923, with a MIC of 6.25 μg/ml, and the MIC for compound (42) against S. aureus ATCC 25923 was 3.12 μg/ml (Takagi et al., 1983). Furthermore, the phenanthrene fraction from the ethanol extract of B. striata has been regarded as a significantly active agent against Gram-positive bacteria, including clinical isolates of MRSA and S. aureus (S. aureus ATCC 25923, 29213, 43300) (Guo et al., 2016).

Table 3.

Antibacterial activities of B. striata.

| Compound No. | Bacteria | MCI | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | C. albicans ATCC 10257 | > 100 µg/ml | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| B.cereus ATCC 11778 | 6.25 µg/ml | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 6.25 µg/ml | ||

| 42 | C. albicans ATCC 10257 | > 100 µg/ml | (Takagi et al., 1983) |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 3.12 µg/ml | ||

| 76.77.78 | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 12.5–50 mg/ml | (Yang et al., 2012) |

| S. epidermidis ATCC 26069 | 25–50 mg/ml | ||

| B. subtilis ATCC 6633 | 25 mg/ml | ||

| 78 | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 32 µg/ml | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 16 µg/ml | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | 16 µg/ml | ||

| S. epidermidis CMCC 26069 | 16 µg/ml | ||

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 16 µg/ml | ||

| E. coli ATCC 35218 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| P. vulgaris CMCC 49027 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| 83 | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 8 µg/ml | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 8 µg/ml | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | 8 µg/ml | ||

| S. epidermidis CMCC 26069 | 8 µg/ml | ||

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 64 µg/ml | ||

| E. coli ATCC 35218 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| P. vulgaris CMCC 49027 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| 84 | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 4 µg/ml | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 2 µg/ml | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | 4 µg/ml | ||

| S. epidermidis CMCC 26069 | 4 µg/ml | ||

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 4 µg/ml | ||

| E. coli ATCC 35218 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| P. vulgaris CMCC 49027 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| 85 | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 64 µg/ml | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 32 µg/ml | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | 32 µg/ml | ||

| S. epidermidis CMCC 26069 | 8 µg/ml | ||

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| E. coli ATCC 35218 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| P. vulgaris CMCC 49027 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| 86 | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 16 µg/ml | (Qian et al., 2015) |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 8 µg/ml | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | 16 µg/ml | ||

| S. epidermidis CMCC 26069 | 8 µg/ml | ||

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 64 µg/ml | ||

| E. coli ATCC 35218 | >128 µg/ml | ||

| P. vulgaris CMCC 49027 | >128 µg/ml |

Clinical Application

TCM Formulations

Based on classical theories of TCM, Chinese medicinal formulations are prepared by pooling different types of medicinal herbs together (Li and Peng, 2013). During the development of TCM theory, many formulations have been recorded in pharmacopeias or by folklore based on clinical experiences. Considering the different causes and symptoms of diseases, B. striata is often used with other drugs to offset the toxicity of one drug or enhance the bioavailability of another drug, which is known as the “correspondence of prescription and syndrome” in TCM.

For example, Bai Ji San (B. striata liniment) is frequently used as an astringent hemostatic medicine. It is composed of B. striata (Bai Ji in Chinese), Asarum sieboldii (Xi Xin), Saposhnikovia divaricata (Fang Feng), and Semen Platycladi (Bai Zi Ren), as noted in Tai Ping Sheng Hui Fang (medical literature edited by the Song Dynasty government). Qu Huo Wai Xiao Tang (decoction for purging fire) can be used to treat skin scalding. It is composed of Bai Ji, Sanguisorba officinalis (Di Yu), Cacumen Platycladi (Bai Ye), stir-baked Fructus Gardeniae (Chao Zhi Zi), Cynanchum otophyllum (Qing Yang Sheng), Angelica sinensis (Dang Gui), and Radix Glycyrrhizae (Gan Cao), as noted in Dong Tian Ao Zhi (Practical Surgical and Clinical Experiences). Although the pharmacologic mechanism of these formulations is not clear, considerable clinical evidence suggests that B. striata has value in the treatment of various diseases.

Embolizing Agent

TACE is a first-line treatment for most inoperable tumors (Tsurusaki and Murakami, 2015). An embolizing agent based on B. striata and TACE has been used in clinical applications. The B. striata embolizing agent can, in general, be classified into three types according to its formulation: liquid, compound, or microspheres.

The B. striata liquid embolizing agent is composed of BSP, cellulose diacetate (solute), and dimethyl sulfoxide (solvent). It has the characteristics of easy flow, good biocompatibility, and no fixed morphology. It can be used for the embolization of irregular tumor cavities and reduces damage to vascular walls (Sun et al., 2005).

The B. striata compound embolizing agent is a synthetic moiety that can be used as an anti-carcinogen and coagulant. In this compound, B. striata can have a pharmacologic role with other medicinal ingredients. It can inhibit the proliferation and spread of tumor cells, and reduce the risk of adverse reactions (Chen et al., 2006).

B. striata polysaccharide microspheres (BSPMs) could be promising transarterial chemoembolization carriers for cancer treatment. BSPMs show favorable drug-loading, swelling, suspension, drug-entrapment, and release characteristics in vitro, which are conducive to long-term targeted chemotherapy (Li et al., 2018b). Studies have shown that BSPMs can embolize the blood supply of hepatic arteries and the hepatic portal vein, and completely inhibit the growth of tumors and surrounding microvessels by stopping the binding of VEGF to its receptor (Zhao et al., 2004).

The B. striata embolizing agent has also performed well in TACE of hepatic cirrhosis with portal hypertension and secondary hypersplenism. In a study by Liu and coworkers, long-term follow-up of surgical patients revealed a mean survival duration of 61.5 ± 9.1 (median, 60; range, 1–157) months in the control group and 63.4 ± 9.9 (52, 0–161) months in the B. striata group. The spleen thickness of treated patients was reduced compared with that before TACE, and the counts of white blood cells, platelets, and red blood cells returned to within normal ranges (Liu et al., 2011). Therefore, TACE using B. striata as an embolizing agent is a safe and efficacious treatment for patients with hepatic cirrhosis with portal hypertension and secondary hypersplenism.

Mucosa-Protective Agent

The imbalance between proteases and mucosal defense factors is an important cause of several digestive-system diseases (e.g., gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and ulcerative colitis). In recent years, strengthening mucosal defenses has become a new strategy to treat peptic ulcers (Al-Jiboury and Kaunitz, 2012). B. striata can be used as a mucosa-protective agent alone or in combination with other Chinese herbal medicines (Zhang et al., 2019a). It can be administered by gastroscopic spraying, injection through a gastric tube, oral administration, or enemas (Zhou et al., 2019).

In the treatment of diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract, B. striata forms a protective film on the damaged mucosal surface to protect it from erosion (by gastric acid) and digestion (by pepsin), thus enhancing the defensive function of the gastric mucosa (He et al., 2016). A preliminary clinical trial showed that B. striata combined with Panax notoginseng, omeprazole, and amoxicillin could reduce the inflammatory response of gastric ulcers, protect the ulcer surface, and promote the regeneration and repair of ulcerated tissue (Bai and Zhang, 2010). In the treatment of ulcerative colitis, B. striata can be added to an enema to act as a mucosa-protective agent. After B. striata powder enters the intestine, it can form a gel on the surface of the intestinal mucosa to protect it. It can also enhance adhesion of drugs to the intestinal wall, thereby increasing the drug concentration in the intestinal tract.

B. striata has a hemostatic function and can promote ulcer healing, which can aid regeneration of the intestinal mucosa and, thus, promote the healing of ulcerative colitis (Lan and Chang, 2014). BSP can alleviate the pathologic damage and symptoms of ulcerative colitis. It can inhibit the expression of TNF-α and nuclear factor-kappa B, upregulate the expression of IL-10, prevent the abnormal release of proinflammatory factors, promote repair of the intestinal mucosa, and inhibit inflammation (Ke and Zhao, 2011). BSP can also reduce the expression of Th2 cytokines in the colon by inhibiting macrophage activation, and relieve inflammation in the intestinal tract. Furthermore, enemas containing B. striata can reduce the risk of postoperative complications of patients with an artificial anus in the colon, reduce the possibility of inflammatory reactions in the surrounding skin, reduce erosion and hemorrhage in the artificial anal mucosa, and improve the quality of life for patients (Lan and Chang, 2014).

Novel Biomaterials

Recently, novel “dissolving microneedles” have been created using BSP. Microneedles can carry drugs into the skin for drug delivery and release encapsulated drugs over time. Compared with conventional transdermal patches and subcutaneous injections, B. striata polysaccharide microneedles are a minimally invasive method of drug delivery that prevents skin retention of biohazardous sharp waste. The pharmacologic activity of BSP contributes to the recovery from the micro-trauma caused by microneedles, such as prevention of bacterial infection and reduction of inflammation (Hu et al., 2018).

Mixing B. striata and polyvinyl alcohol to form a dressing matrix can result in a novel, high-quality biologic dressing. This material makes full use of the pharmacologic activity of B. striata for hemostasis and wound healing, and has been shown to have good mechanical properties and biocompatibility. Hence, it can absorb oozing blood and tissue fluid, which accelerates the healing of burns, surgical wounds, and acute wounds (Lin et al., 2012).

A novel, readily stripped bilayer composite was designed as a wound-dressing material, and exhibited excellent biocompatibility and mechanical properties. This composite comprised an upper layer of soybean protein nonwoven fabric coated with a lower layer of genipin-crosslinked chitosan and B. striata herbal extract. The extract in the wound-dressing material was non-toxic, but also promoted the growth of L929 fibroblasts, which are beneficial for wound healing (Liu and Huang, 2010).

Quality Control

The China Food and Drug Administration defines “geo-authentic” herbs as traditional Chinese crude drugs grown in unadulterated environments and subjected to natural conditions, or with specific cultivation techniques and processing methods (Brinckmann, 2013). Zheng’an County in Guizhou Province is accepted as the most optimal location to produce the crude tubers of B. striata in China. The B. striata produced here is called “Zheng’an Bai Ji”. However, the material basis and potential mechanisms for producing geo-authentic herbs are not completely clear. The Chinese Pharmacopoeia recommends identifying the geo-genuine properties of B. striata according to morphologic, microscopic, and thin-layer chromatography approaches, and by ensuring that the residual inorganic components after ashing are ≤15.0% (He et al., 2016).

The standards mentioned above are accepted in formularies and pharmacopoeias, but may not be sufficient to evaluate the quality of all B. striata tubers. The latter contain various medicinally active ingredients (e.g., glycosides, bibenzyls, phenanthrenes, biphenanthrenes, and dihydrophenanthrenes) which should also be considered in quality control. For example, assessment of amounts of dactylorhin A (1), gymnoside V (5), gymnoside IX (6), militarine (8), and bletilnoside A (9) by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography using photo-diode array detection showed obvious variation in response to the different origins of B. striata. The mass fraction of each chemical marker was 0.341–1.110, 2.840–6.990, 5.790–34.400, 0.191–3.890, and 0.184–5.050 mg/g, respectively. Among them, a wild strain of B. striata produced in Zheng’an County contained relatively high levels of active ingredients at 1.110, 6.500, 31.400, 3.890, and 5.05 mg/g, respectively (Wang et al., 2014). Furthermore, Liu et al. used a parallel-line assay based on quantitative responses to evaluate the hemostatic potency of B. striata obtained from different habitats, which provided monitoring indicators for the clinical efficacy of B. striata (Liu et al., 2014). These preliminary results may provide evidence for the geographic specificity and quality control of geo-authentic herbs.

Toxicology

Toxic side effects and adverse reactions from B. striata have rarely been reported. If B. striata is used with Aconitum carmichaeli, it enhances the content of hypaconitine in the decoction (Weng et al., 2004). However, hypaconitine can increase the expression of RyR2 (a regulatory protein related to the function of calcium channels) in cardiac muscle, which may result in an abnormal heart rate (Liu et al., 2016). Therefore, B. striata cannot be used with A. carmichaeli in TCM (He et al., 2016).

Tests to determine the acute toxicity of B. striata have shown that the mean mortality of mice is <20% if a single intragastric dose is increased to 80 g/kg body weight, and the median lethal dose of B. striata was not detected. Subsequent experiments using a maximum dose of B. striata that did not cause the death of experimental animals was determined to be 180 g/kg body weight (Zhang et al., 2013).

A series of toxicology experiments showed that BSP did not elicit allergic reactions, phototoxicity reactions and, most importantly, no obvious adverse reactions to human skin. These experiments included tests of acute oral toxicity (in mice), skin stimulation (rabbits), skin allergy (guinea pigs), skin phototoxicity (guinea pigs), and skin patches (humans) (Zhang et al., 2003). Yue and colleagues showed that the acute toxicity of BSP was very low. Mice were given BSP (4 g/kg body weight, i.g.) twice during an interval of 6 h. None of the mice died, and no significant changes were detected in their activity, food intake, fur, or weight (Yue et al., 2003).

Conclusions and Perspectives

B. striata has been used as a medicinal herb in China for thousands of years. However, due to the high degree of personalization of the diagnosis and treatment of TCM, its clinical efficacy cannot be comprehensively evaluated by evidence-based medicine. In this review, we categorized research on B. striata based on its chemical constituents, pharmacologic activities, and clinical applications. We also tried to establish connections between the conclusions of many studies carried out on B. striata.

More than 150 compounds have been isolated from various parts of B. striata, and they exhibit a wide range of biologic and pharmacologic properties. Efficacious use of B. striata is dependent upon the connection between these chemical components and their specific bioactivities. Based on extensive biologic testing, numerous phytochemicals identified in B. striata are efficacious against one or more diseases. Developing and applying monomer compounds isolated from this herb is another development direction. Therefore, B. striata has great potential to be further mined for its pharmacological effects.

These studies on component detection, pharmacological probing, and clinical exploration conducted on B. striata have provided us with additional data for this valuable herb. Additional systematic studies will offer sufficient proof for establishing the efficacy and safety of this herb so it can be used as a medicine from a scientific point of view. We hope that this review will allow further research and development of this unique plant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: DX. Project administration: DX, JC. Writing – original draft: YP. Writing – review and editing: DX, JC.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31560079, 31560102, 31960074), the PhD Science Foundation of Zunyi Medical University (F-809), the Talent Growth Project of the Guizhou Education Department (KY[2017]194), and the Research Project of Guizhou Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (QZYY-2019-060).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Surendra Sarsaiya (ZMU, China) for proofreading an earlier version of this article.

References

- Al-Jiboury H., Kaunitz J. D. (2012). Gastroduodenal mucosal defense. Curr. Opin. Gastroen. 28, 594–601. 10.1097/00001574-199012000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft G. S., Yang X., Glick A. B., Weinstein M., Letterio J. J., Mizel D. E., et al. (1999). Mice lacking Smad3 show accelerated wound healing and an impaired local inflammatory response. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 260–266. 10.1038/12971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J. Y., Lee J. W., Jin Q., Jang H., Lee D., Kim Y., et al. (2016). Chemical constituents isolated from Bletilla striata and their inhibitory effects on nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 Cells. Chem. Biodivers. 14, e1600243. 10.1002/cbdv.201600243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L., Kato T., Inoue K., Yamaki M., Takagi S. (1991). Blestrianol A, B and C, biphenanthrenes from Bletilla striata. Phytochemistry 30, 2733–2735. 10.1016/0031-9422(91)85133-K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L., Kato T., Inoue K., Yamaki M., Takagi S. (1993). Stilbenoids from Bletilla striata . Phytochemistry 33, 1481–1483. 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85115-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L., Yamaki M., Inoue K., Takagi S. (1990). Blestrin A and B, bis(dihydrophenanthrene)ethers from Bletilla striata . Phytochemistry 29, 1259–1260. 10.1016/0031-9422(90)85437-K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X. M., Zhang Q. Y. (2010). Observation of baijigou powder, notoginseng powder and cuttlefish bone jointed with omeprazole and amoxicillin in the treatment of gastric ulcer. Chin. Med. Herald 7, 79–80. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7210.2010.03.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldridge M. T., King K. Y., Boles N. C., Weksberg D. C., Goodell M. A. (2010). Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-gamma in response to chronic infection. Nature 465, 793–797. 10.1038/nature09135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri R., Coppo E., Marchese A., Daglia M., Sobarzo-Sánchez E., Nabavi S. F., et al. (2017). Phytochemicals for human disease: An update on plant-derived compounds antibacterial activity. Microbiol. Res. 196, 44–68. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinckmann J. A. (2013). Emerging importance of geographical indications and designations of origin-authenticating geo-authentic botanicals and implications for phytotherapy. Phytother. Res. 27, 1581–1587. 10.1002/ptr.4912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. C., Lin C. X., Chen N. P., Gao C. X., Zhao Y. J., Qian C. D. (2018). Phenanthrene antibiotic targets bacterial membranes and kills Staphylococcus aureus with a low propensity for resistance development. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1593–1602. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Lv L. Y., Li Y., Ren X. D., Luo H., Gao Y. P., et al. (2019). Preparation and evaluation of Bletilla striata polysaccharide/graphene oxide composite hemostatic sponge. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 130, 827–835. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.02.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Q., Yang X. Z., Shen J. J., Wang S. D., Zhen X. G. (2006). The experimental studies of Chinese herbs as a vascular embolization agent for the hepatic arteries. J. Interventronal. Radiol. 15, 88–92. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-794X.2006.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Y., Cheng L. Z., He Y. C., Wei X. L. (2018). Extraction, characterization, utilization as wound dressing and drug delivery of Bletilla striata polysaccharide: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 120, 2076–2085. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha T. M., Verri W. A., Fukada S. Y., Guerrero A. T. G., Santodomingo-Garzón T., Poole S., et al. (2007). TNF-α and IL-1β mediate inflammatory hypernociception in mice triggered by B1 but not B2 kinin receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 573, 221–229. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y., Sun L. R. (2008). Advances in studies on bibenzyls naturally occurred in plant. Chin. Tradit. Herbal. Drugs 39, 1753–1755. 10.3321/j.issn:0253-2670.2008.11.051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debieu D., Gall C., Gredt M., Bach J., Malosse C., Leroux P. (1992). Ergosterol biosynthesis and its inhibition by fenpropimorph in Fusarium species. Phytochemistry 31, 1223–1233. 10.1016/0031-9422(92)80265-G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diao H. J., Li X., Chen J. N., Luo Y., Chen X., Dong L., et al. (2008). Bletilla striata polysaccharide stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase and proinflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 105, 85–89. 10.1263/jbb.105.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L., Dong Y. X., Liu X. X., Liao S. G., Wang A. M., Li Y. J. (2014). Effect of Bletilla striata polysaccharides on rat platelet aggregation, coagulation function, TXB2 and 6-keto-PGF1α expression. J. Guiyang Med. Coll. 39, 459–462. 10.19367/j.cnki.1000-2707.2014.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J. Q., Zhang R. J., Zhao W. M. (2008). Novel bibenzyl derivatives from the tubers of Bletilla striata . Helv. Chim. Acta 91, 520–525. 10.1002/hlca.200890056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gachet C. (2006). Regulation of platelet functions by P2 receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. 46, 277–300. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. J., Loake G. J. (2000). Role of reactive oxygen intermediates and cognate redox signaling in disease resistance. Plant Physiol. 124, 21–29. 10.1104/pp.124.1.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu R. H., Hong L. Y., Long C. L. (2013). The ways of producing secondary metabolites via plant cell culture. Plant Physiol. 9, 869–881. 10.13592/j.cnki.ppj.2013.09.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Q. X., Zhang G. Y., Sun D. D., Wang Y., Liu K., Wang M., et al. (2017). In vitro and in vivo evaluation of docetaxel-loaded stearic acid-modified Bletilla striata polysaccharide copolymer micelles. PLos One 12, e0173172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. J., Dai B. L., Chen N. P., Jin L. X., Jiang F. S., Ding Z. S., et al. (2016). The anti-Staphylococcus aureus activity of the phenanthrene fraction from fibrous roots of Bletilla striata . BMC Complem. Altern. M. 16, 491–497. 10.1186/s12906-016-1488-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G. X., Wang L. X., Wang M. L., Zhang W. D., Li T. Z., Liu W. Y., et al. (2001). Studies on the chemical constituents of Bletilla striata . J. Pharm. Pract. 19, 360–361. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-0111.2001.06.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han G. X., Wang L. X., Zhang W. D., Wang M. L., Liu H. T., Xiao J. H. (2002. a). Studies on chemical constituents of Bletilla striata (II). Acad. J. Second Mil. Med. Univ. 23, 1029–1031. 10.16781/j.0258-879x.2002.09.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han G. X., Wang L. X., Zhang W. D., Yang Z., Li T. Z., Jiang T., et al. (2002. b). Study on chemical constituents of Bletilla striata(I). Acad. J. Second Mil. Med. Univ. 23, 443–445. 10.16781/j.0258-879x.2002.04.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han G. X., Wang L. X., Zheng Bing G. U., Zhang W. D., Chen H. S. (2002. c). A new bibenzyl derivative from Bletilla striata . Chin. Chem. Lett. 13, 231–232. 10.1021/cm022001r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. R., Wang X. X., Fang J. C., Zhao Z. F., Huang L. H., Hao G., et al. (2016). Bletilla striata: Medicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 195, 20–38. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heleno S. A., Martins A., Queiroz M. J. R. P., Ferreira I. C. F. R. (2015). Bioactivity of phenolic acids: metabolites versus parent compounds: a review. Food Chem. 173, 501–513. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. M. (2011). Therapeutic orchids: traditional uses and recent advances-an overview. Fitoterapia 82, 102–140. 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. L., Liao Z. C., Hu Q. Q., Maffucci K. G., Qu Y. (2018). Novel Bletilla striata polysaccharide microneedles: fabrication, characterization, and in vitro transcutaneous drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 117, 928–936. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Shi F., Wang L., Yang Y., Khan B. M., Cheong K. L., et al. (2019). Preparation and evaluation of Bletilla striata polysaccharide/carboxymethyl chitosan/Carbomer 940 hydrogel for wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 132, 729–737. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung H. Y., Wu T. S. (2016). Recent progress on the traditional Chinese medicines that regulate the blood. J. Food Drug Anal. 24, 221–238. 10.1016/j.jfda.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F. S., Li W. P., Huang Y. F., Chen Y. T., Jin B., Chen N. P., et al. (2013). Antioxidant, antityrosinase and antitumor activity comparison: the potential utilization of fibrous root part of Bletilla striata (Thunb.) Reichb.f. PLos One 8, e58004. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya A., Tokura Y. (2014). Attempts to accelerate wound healing. J. Dermatol. Sci. 76, 169–172. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke C. Y., Zhao C. J. (2011). Effects of Bletilla striata polysaccharides on ulcerative colitis. Chin. Pharm. 22, 2132–2134. 10.1007/s10008-010-1224-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lan H., Chang M. Q. (2014). Application of Bletilla striata in diagnosis and treatment of anorectal diseases. Chin. J. Coloproctol. 34, 53–55. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-1174.2014.12.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Li L., Yang C. F., Zhong Y. J., Wu D., Shi L., et al. (2017). Hepatoprotective effects of Methyl ferulic acid on alcohol-induced liver oxidative injury in mice by inhibiting the NOX4/ROS-MAPK pathway. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 493, 277–285. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Y., Kuang M. T., Yang L., Kong Q. H., Hou B., Liu Z. H., et al. (2008. a). Stilbenes with anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activity from the rhizomes of Bletilla ochracea Schltr. Fitoterapia 127, 47–80. 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Peng T. (2013). Traditional Chinese herbal medicine as a source of molecules with antiviral activity. Antiviral. Res. 97, 1–9. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. Z., Zhao N., Chen Z., Han W. X., Fu L. N., He S. M., et al. (2018. b). Preparation of matrine loaded microspheres based on Bletilla striata polysaccharide. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 53, 284–290. 10.16438/j.0513-4870.2017-0903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. H., Lu C. T., Hu J. J., Chen Y. S., Huang C. H., Lou C. W. (2012). Property evaluation of Bletilla striata/polyvinyl alcohol nano fibers and composite dressings. J. Nanomater. 2012, 5. 10.1155/2012/519516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. L., Chen W. P., Macabalang A. D. (2005). Dihydrophenanthrenes from Bletilla formosana . Chem. Pharm. Bull. 53, 1111–1113. 10.1002/chin.200608189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou M. J., Wu T. S. (2002). Triterpenoids from Rubia yunnanensis . J. Nat. Prod. 65, 1283–1287. 10.1021/np020038k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. S., Huang T. B. (2010). A novel wound dressing composed of nonwoven fabric coated with chitosan and herbal extract membrane for wound healing. Polym. Composite. 31, 1037–1046. 10.1002/pc.20890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. Q., Wang Y. P., Han D., Bi Y. J., Li H. B., Liu G., et al. (2013). Extraction of Bletilla striata polysaccharide and its relative molecular mass determination and structure study. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 35, 2291–2293. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1528.2013.10.055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M. X., Song T. T., Ye C., Zhang Y., Shi Y. H., Dai J. L. (2018). Inhibitory effect of Bletilla Striata polysaccharide on the proliferation of HepG2 . Asia-Pacific. Tradit. Med. 14, 11–13. 10.11954/ytctyy.201803005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Teng X. J., He J. F., Xiao S. S., Yuan Z. B., Li X. J., et al. (2011). Partial splenic embolization using Bletilla striata particles for hypersplenism in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Am. J. Chin. Med. 39, 261–269. 10.1142/S0192415X11008804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Li Y., Li W. F., Xu J. K., Li F., Du H. (2016). Advances in studies on toxicity and modern toxicology of species in. Aconitum L. Chin. Tradit. Herbal. Drugs 47, 4095–4102. 10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2016.22.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. X., Dong L., Zhang X. H., Dong Y. X., Wang A. M., Liao S. G., et al. (2014). Quality evaluation of Bletillae Rhizoma based on hemostatic biopotency. Chin. J. Chin. Mater. Med. 39, 2051–2055. 10.4268/cjcmm20141920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lolmede K., Campana L., Vezzoli M., Bosurgi L., Tonlorenzi R., Clementi E., et al. (2009). Inflammatory and alternatively activated human macrophages attract vessel-associated stem cells, relying on separate HMGB1- and MMP-9-dependent pathways. J. Exp. Med. 85, 779–787. 10.1189/jlb.0908579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B., Xu Y. M., Zhang H. M., Li T. J., Qiu Y. (2005). Effects of different extracts from Bletilla Colloid on rabbit platelet aggregation. Pharm. J. PLA. 21, 330–331. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-9926.2005.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Diao H. J., Xia S. H., Dong L., Chen J. N., Zhang J. F. (2010). A physiologically active polysaccharide hydrogel promotes wound healing. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 94, 193–204. 10.1002/jbm.a.32711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X. J., Cui B. S., Han S. W., Li S. (2017). Chemical constituents from tuber of Bletilla striata . Chin. J. Chin. Mater. Med. 42, 1578–1584. 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.2017.0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. R., Roberto P. B., Darshan D., Riemersma R. A., Appel L. J., Eliseo G. (2005). Meta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Ann. Intern. Med. 142, 37–46. 10.1016/j.accreview.2005.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. (2002). Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 405–410. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H., Koyama K., Sugimoto Y., Kobayashi J. I. (2005). Antimitotic activity and reversal of breast cancer resistance protein-mediated drug resistance by stilbenoids from Bletilla striata . Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15, 1051–1054. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. E., Woo K. W., Sang U. C., Lee J. H., Kang R. L. (2014). Two new cytotoxic spirostane-steroidal saponins from the roots of Bletilla striata . Helv. Chim. Acta 97, 56–63. 10.1002/hlca.201300102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q., Li M., Xue F., Liu H. J. (2014). Structure and immunobiological activity of a new polysaccharide from Bletilla striata . Carbohyd. Polym. 107, 119–123. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C. D., Jiang F. S., Yu H. S., Shen Y., Fu Y. H., Cheng D. Q., et al. (2015). Antibacterial biphenanthrenes from the fibrous roots of Bletilla striata . J. Nat. Prod. 78, 939–943. 10.1021/np501012n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J., Vossoughi D., Woitaschek D., Oppermann E., Bechstein W. O., Li W. Y., et al. (2003). Combined transarterial chemoembolization and arterial administration of Bletilla striata in treatment of liver tumor in rats. World J. Gastroentero. 9, 50–54. 10.1080/00365520310005712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H. M., Ying Z., Zhou Q. X., Shu L. (2011). Regulatory effect of Bletilla striata polysaccharide on immune function of mice. Chin. J. Biologicals 24, 676–678. 10.13200/j.cjb.2011.06.57.qiuhm.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y., Li C. X., Zhang C., Zeng R., Fu C. M. (2016). Optimization of infrared-assisted extraction of Bletilla striata polysaccharides based on response surface methodology and their antioxidant activities. Carbohyd. Polym. 148, 345–353. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee J. K., Kim P. G., Baek B. K., Lee S. B., Ahn B. Z. (1982). Isolation of anthelmintic substance on clonorchis sinensis from tuber of Bletilla striata . Korean J. Parasitol. 20, 142. 10.3347/kjp.1982.20.2.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A., Russell S. J. (2012). A new paradigm in viral resistance. Cell Res. 22, 1515–1517. 10.1038/cr.2012.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N., Ku M., Tatsuzawa F., Lu T. S., Yokoi M., Shigihara A., et al. (1995). Acylated cyanidin glycosides in the purple-red flowers of Bletilla striata . Phytochemistry 40, 1523–1529. 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00479-Q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Bing Z., Lu Y. Y., Qian C. D., Yan F., Fang L. W., et al. (2017). Antiviral activity of phenanthrenes from the medicinal plant Bletilla striata against influenza A virus. BMC Complem. Altern. M. 17, 273–287. 10.1186/s12906-017-1780-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Zeng R., Hu L. L., Maffucci K. G., Ren X. D., Qu Y. (2017). In vivo wound healing and in vitro antioxidant activities of Bletilla striata phenolic extracts. Biomed. Pharmacother. 93, 451–461. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M., Sudheer A. R., Pillai K. R., Kumar P. R., Sudhakaran P. R., Menon V. P. (2006). Influence of ferulic acid on γ-radiation induced DNA damage, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in primary culture of isolated rat hepatocytes. Toxicology 228, 249–258. 10.1016/j.tox.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stintzing F. C., Carle R. (2004). Functional properties of anthocyanins and betalains in plants, food, and in human nutrition. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 15, 19–38. 10.1016/j.tifs.2003.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun A. J., Liu J. Q., Pang S. Q., Lin J. S., Xu R. A. (2016. a). Two novel phenanthraquinones with anti-cancer activity isolated from Bletilla striata . Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 2375–2379. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.01.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun A. J., Pang S. Q., Wang G. Q. (2016. b). Chemical constituents from Bletilla striata and their anti-tumor activities. Chin. Pharmacol. J. 51, 101–104. 10.11669/cpj.2016.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun A. J., Pang S. Q., Wang G. Q. (2016. c). Separation of chemical constituents from Bletilla striata and their antitumor activities. Chin. Pharmacol. J. 47, 35–38. 10.1002/chin.201634198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. T., Zhang J. F., Chen Y. X. (2005). Embolization of carotid aneurysms in rabbit models using self-made liquid embolic agent from Bletillae Rhizoma. Chin. J. Minim. Invas. Neurosur. 10, 462–464. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-122X.2005.10.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Süntar I., Akkol E. K., Nahar L., Sarker S. D. (2012). Wound healing and antioxidant properties: do they coexist in plants? Free Radical. Antioxid. 2, 1–7. 10.5530/ax.2012.2.2.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S., Yamaki M., Inoue K. (1983). Antimicrobial agents from Bletilla striata. Phytochemistry 22, 1011–1015. 10.1016/0031-9422(83)85044-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. F., Ruan C. F., Ying C., Zhang H. W. (2014). Research progress on chemical constituents and medical functions in plants of Bletilla Rchb. f. Chin. Tradit. Herbal. Drugs 45, 2864–2872. 10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2014.19.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Tang X. D., Li Z. H., Zhang L. Y., Zhang B. P., Du N. (2015). Research overview of clinical application of TCM powders in digestive system diseases. Chin. J. Inf. Tradit. Chin. Med. 22, 128–130. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-5304.2015.09.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuzawa F., Saito N., Shigihara A., Honda T., Toki K., Shinoda K., et al. (2010). An acylated cyanidin 3,7-diglucoside in the bluish flowers of Bletilla striata‘Murasaki Shikibu’ (Orchidaceae). J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 79, 215–220. 10.2503/jjshs1.79.215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurusaki M., Murakami T. (2015). Surgical and locoregional therapy of HCC: TACE. Liver Cancer 4, 165–175. 10.1159/000367739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraja B., Vanitha Malathy V., Balasubramanian E., Mohan, Rajendran R., Rammohan R. (2012). Biopolymer and Bletilla striata herbal extract coated cotton gauze preparation for wound healing. J. Med. Sci. 12, 148–160. 10.3923/jms.2012.148.160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. M., Yan Y., Lan B., Liao S. G., Wang Y. L., Li Y. J. (2014). Simultaneous determination of nine chemical markers of Bletillae Rhizoma by ultra performance liquid chromatography. Chin. J. Chin. Mater. Med. 39, 2051–2055. 10.4268/cjcmm20141121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Luo W. F., Li P. W., Li S. D., Yang Z. M., Zhang H., et al. (2017). Preparation and evaluation of chitosan/alginate porous microspheres/Bletilla striata polysaccharide composite hemostatic sponges. Carbohyd. Polym. 174, 432–442. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. M., Sun J. T., Yi L., Xue W. H., Diao H. J., Lei D., et al. (2006). A polysaccharide isolated from the medicinal herb Bletilla striata induces endothelial cells proliferation and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in vitro . Biotechnol. Lett. 28, 539–543. 10.1007/s10529-006-0011-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]