Abstract

Background

Thymidylate synthase (TYMS) is a successful chemotherapeutic target for anticancer therapy. Numerous TYMS inhibitors have been developed and used for treating gastrointestinal cancer now, but they have limited clinical benefits due to the prevalent unresponsiveness and toxicity. It is urgent to identify a predictive biomarker to guide the precise clinical use of TYMS inhibitors.

Methods

Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening was performed to identify potential therapeutic targets for treating gastrointestinal tumours as well as key regulators of raltitrexed (RTX) sensitivity. Cell-based functional assays were used to investigate how MYC regulates TYMS transcription. Cancer patient data were used to verify the correlation between drug response and MYC and/or TYMS mRNA levels. Finally, the role of NIPBL inactivation in gastrointestinal cancer was evaluated in vitro and in vivo.

Findings

TYMS is essential for maintaining the viability of gastrointestinal cancer cells, and is selectively inhibited by RTX. Mechanistically, MYC presets gastrointestinal cancer sensitivity to RTX through upregulating TYMS transcription, supported by TCGA data showing that complete response cases to TYMS inhibitors had significantly higher MYC and TYMS mRNA levels than those of progressive diseases. NIPBL inactivation decreases the therapeutic responses of gastrointestinal cancer to RTX through blocking MYC.

Interpretation

Our study unveils a mechanism of how TYMS is transcriptionally regulated by MYC, and provides rationales for the precise use of TYMS inhibitors in the clinic.

Funding

This work was financially supported by grants of NKRDP (2016YFC1302400), STCSM (16JC1406200), NSFC (81872890, 81322034, 81372346) and CAS (QYZDB-SSW-SMC034, XDA12020210).

Keywords: Thymidylate synthase, Raltitrexed, MYC, NIPBL, Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening

Research in context

Evidence before this study

To date, fluorouracil (5FU)-based chemotherapy is the first line choice for treating gastrointestinal cancer, but has limited response rate in the clinic due to the prevalent unresponsiveness and toxicity.

Added value of this study

Our study unveils a novel mechanism showing TYMS is transcriptionally regulated by MYC, while NIPBL loss reduces MYC bioactivity and impairs gastrointestinal cancer sensitivity to RTX through downregulating TYMS. Our data suggest that gastrointestinal tumours with high MYC and TYMS expression will have better therapeutic responses compared with low MYC and TYMS expressing tumours, which is well supported by TCGA cancer patient data.

Implications of all the available evidence

High MYC/TYMS expression can be served as a potential biomarker to predict the therapeutic responses of TYMS inhibitors for treating gastrointestinal cancer in the clinic.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal cancer is a malignant disease originating from gastrointestinal tract and accessory organs of digestion, consisting of esophagus cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, and others. Gastric cancer and colorectal cancer are two kinds of the most prevalent cancer types [1, 2], and the age-standardised 5-year relative survivals for gastric and colorectal cancers are 27.5% and 47.2% in China, respectively [3].

To date, 5FU-based chemotherapy is still served as the first-line choice for treating gastric and colorectal cancers. 5FU, which is a kind of dUMP mimetics, forms a covalent complex with thymidylate synthase and inhibits the enzymatic activity of catalyzing the reductive methylation of dUMP by 5,10-methylene tetrahydrofolate (5′,10′-mTHF) to produce dTMP and dihydrofolate (DHF) [4, 5]. Antifolate drugs are another class of thymidylate synthase inhibitor, including methotrexate (MTX), raltitrexed (RTX) and pemetrexed (PTX) [6]. MTX has been used to cure childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia since 1950s [7]. RTX is approved for the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer [8], and PTX is widely used for treating malignant pleural mesothelioma and non-small cell lung cancer [9, 10]. All the thymidylate synthase inhibitors including dUMP mimetics and antifolates have limited benefits in the clinic due to the primary resistance [11], although they have been widely used for treating gastrointestinal cancer [12], [13], [14]. Therefore, it is urgent to identify a predictive biomarker to guide the precise use of thymidylate synthase inhibitors for treating gastrointestinal tumours.

Using genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening, we identified that MYC is a potential candidate for maintaining the sensitivity of gastrointestinal tumours to antifolate drugs. MYC, belonging to the basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper (bHLH-LZ) family, promotes the transcription of downstream genes through selectively binding to “E-box” consensus motif (CANNTG) [15, 16] and is vitally important for maintaining cellular homeostasis, proliferation and survival. MYCis frequently amplified in various human cancer types, but couldn't be directly targeted by currently available anticancer drugs [17]. However, it's still unknown whether MYC regulates TYMS expression.

On the other hand, we also observed that the protein expression of thymidylate synthase (TS) was markedly reduced in gastrointestinal cancer cell lines with genetic alternations of cohesin complex and -associated regulators. Cohesin complex is indispensable for gene transcription [18, 19]. In mammals, cohesin complex is composed of two structural maintenance of chromosome subunits (SMC1A/SMC1B and SMC3); one HEAT-repeats subunit (STAG1, STAG2 or STAG3); and one kleisin subunit (RAD21, REC8 or RAD21L) [20], [21], [22]. Cohesin and -associated regulatory members are frequently mutated in somatic and cancer cells [23], [24], [25]. For example, NIPBL and STAG2 are frequently altered at expression and mutation levels across many cancer types such as colorectal and bladder cancers [26, 27]. However, the biological role of deregulated cohesin members is largely elusive in cancer development.

In this study, we found that TYMS is essential for maintaining the survival of gastrointestinal tumour cells through whole genome screening, and further identified that MYC is a key transcription factor responsible for regulating TYMS transcription. Loss of NIPBL will reduce the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer to RTX through downregulating MYC-mediated TYMS transcription. Our work provides rationales for the future precise use of thymidylate synthase inhibitors in the clinic, avoiding their ineffective usage in the low MYC expressed tumours.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell cultures

The gastric cancer cell lines were purchased from Korean Cell Line Bank, RIKEN BRC Cell Bank or JCRB Cell Bank, respectively. Colorectal cancer cell lines SW480, HT29, RKO, SW620, NCI-H716, HCT116, LOVO and HCT15 were purchased from the Cell Bank of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences (Shanghai, China), and HCT8 and CW2 colorectal cancer cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. Zehong Miao from Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica. Cells were cultured in either RPMI 1640 or DMEM/F12 medium (Hyclone) with 10% foetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Life Technologies), and were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. All cell lines were recently authenticated with STR assays, and were kept as mycoplasma-free.

2.2. Compounds

Raltitrexed, pemetrexed, and methotrexate were purchased from Selleck. 5FU, puromycin, choloroquine, dTMP and polybrene were obtained from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO). 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Amersco (Cat. 0793-1G, Solon, OH).

2.3. Antibodies

The antibodies of TS (sc-390945, 1:3000), NIPBL (sc-374625, 1:2000), MYC (sc-40, 1:2000), Lamin B (sc-6216, 1:3000) and Vinculin (sc-25336, 1:3000) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The antibody of Tubulin (ab135209, 1:5000) was purchased from Abcam.

2.4. Plasmids

GeCKOv2 CRISPR knockout pooled library (#1000000048), LentiCRISPR v2 (#52961), pRSV-Rev (#12253), pMDLg/pRRE (#12251), pMD2.G (#12259), pLX302 (#25896) and pLKO.1-puro (#8453) were purchased from Addgene.

2.5. Cell viability assay

Cells were digested by 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, and plated into 96-well plates after cell number counting. Chemical was added to the cells at final concentrations of 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, and 10 µM on the next day, followed by 72 h incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2. When treatment stopped, cells were then added with 20 µl MTT solution for 4 h, followed by 12–16 h incubation with 50 µl triplex solution (0.012 M HCl, 10% SDS, and 5% isobutanol) before detecting OD570.

2.6. LC−MS/MS Analysis

1.5 × 106 NUGC3 cells were plated into 10 cm culture dishes, followed by either 8 nM RTX or 0.1% DMSO treatment for 72 h. Cells were enzymatically digested by 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, washed with 1 × PBS twice and were then centrifuged at 5,000 g at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was added with 200 µl of 80:20 methanol:water at −80 °C and mixed well. After incubated for 15 min at −80 °C, the sample was centrifuged at 13,200 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min and the soluble extract was collected. The second extraction was performed in the same condition as described above, and combined with the first extract. The third extraction was performed in the same condition with an additional sonication for 10 min on ice bath, and was combined with another two extracts. A 600 µl of total extract was analysed by Thermo Scientific TSQ Vantage triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

2.7. GeCKO library screening

The GeCKO library screening was referenced to Feng Zhang [28, 29], and was described as follows:

-

1)

Lentivirus production and purification

2 × 106 HEK293T cells were seeded into 10 cm dishes in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% foetal bovine serum the day before transfection. Fresh medium containing 25 nM chloroquine were replaced one hour before transfection. Transfection was performed with 8 µg pooled library and 8 µg lentiviral packaging vector (the mole ratio of pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/pRRE and pMD2.G was 1:1:1) using calcium phosphate. 6 h after transfection, cells were replaced with fresh DMEM/F12 media with 10% foetal bovine serum. Virus was collected at 48 and 72 h after transfection and centrifuged at 4 °C at 2,000 rpm for 10 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm ultra-low protein binding filter (Millipore, SLHV033RS), and was precipitated with PEG8000 and NaCl at final concentration of 5% and 0.15 M, respectively. The virus was re-suspended and stored at −80 °C.

-

2)

Titration of the virus

8 × 105 GSU, KATOIII, NUGC3, or SNU-638 cells were plated into 6-well plates with 3 ml medium supplemented with 10% of foetal bovine serum and 8 µg/ml polybrene. Different titrated virus amount (0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 60, 70, 85, and 100 µl) were added into each well and then spinfected at 2,000 rpm at 37 °C for 2 h. After spinfection, cells were replaced with fresh culture medium. Cells were further cultured in the incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells in each well were equally plated into duplicate wells after trypsinization. One replicate was added with 3 ml fresh culture medium supplemented with 1 µg/ml puromycin, and the other replicate receiving no puromycin. Cells in every well were counted to calculate the MOI after 3 days when there was no living cell in the non-transduction group after puromycin treatment. MOI was calculated using the following formula: percent transduction (P) = cell number from puromycin treatment replicate/cell number from non-puromycin replicate × 100%, and MOI = −In(1 − P) (pfu/cell).

-

3)

Large-scale GeCKO library screening

Total 2 × 108 cells were plated into 6-well plates at density of 8 × 105 per well supplemented with 8 µg/ml polybrene. The library virus was added into each well, followed by spinfection as described above. Cells were plated into 10 cm dishes at a density of 2 × 106 per dish supplemented with 1 µg/ml puromycin after 24 h of spinfection. Puromycin selection was performed for 7 days to remove uninfected cells, as well as allowing enough time for genome editing. After puromycin selection, 2 × 107 cells were directly harvested, washed with 1 × PBS and were stored at −80 °C as control group (termed as DMSODay0 group). To screen potential therapeutic targets, 2 × 107 cells per group of every cell line will be further treated with 0.1% DMSO for another 14 days (termed as DMSODay14 group). To explore the key genes that determine the sensitivity of NUGC3 to RTX, cells were split into three groups, 2 × 108 cells were received the treatment of 10 nM RTX (termed as RTXDay14 group), 3 × 107 cells were received the treatment of 0.1% DMSO (termed as DMSODay14 group), and 2 × 107 cells in DMSODay0 group were directly collected once puromycin selection was stopped. In order to keep 300-fold coverage of GeCKO library sgRNAs, at least 2 × 107 cells were required to be collected for each group when treatment stopped. For RTXDay14 group, 2 × 108 cells were used because 90% of total cells will be inhibited after treated with 10 nM RTX for 14 days according to our pilot experiment.

-

4)

Genomic DNA extraction and sequencing

The genomic DNA of indicated groups like DMSODay0, DMSODay14, and RTXDay14 were extracted with a Blood & Cell Culture Midi kit (Qiagen, 13343). PCR was performed in two steps for each group using TransTaq® HiFi DNA Polymerase (TransGen biotech, AP131-02): the first step of the PCR was carried out with 18 cycles in 26 × 50 µl reactions with 5 µg genomic DNA, resulting in the amplification of 130 µg genomic DNA to achieve 300 -fold coverage of the GeCKO library. The second PCR was performed with 20 cycles in 10 × 50 µl reactions with 5 µl of the combined first PCR-resulting amplicons. The second PCR product was purified by gel extraction (Qiagen, 20051) and was sequenced by Illumina HiSeq X Ten (GENEWIZ, Suzhou, China). The sequenced data were analysed using a MAGeCK algorithm [30], and CRISPR gene score (CS) = average [log2 (RTXDay14 sgRNA abundance/DMSODay14 sgRNA abundance)] or average [log2(DMSODay14 sgRNA abundance/DMSODay0 sgRNA abundance) [31].

PCR primers used in this process are as follows: v2Adaptor_F: 5′-AATGGACTATCATATGCTTACCGTAACTTGAAAGTATTTCG-3′ v2Adaptor_R: 5′-TCTACTATTCTTTCCCCTGCACTGTtgtgggcgatgtgcgctctg-3′;

Illumina primer F:

5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGC-TCTTCCGATC

TtATCACGtct tgtggaaaggacgaaacaccg-3′;

Illumina primer R:

5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATATCACGGTGACTGGAGTTCAG-ACGTGTGCTC

TTCCGATCTtTCTACTATTCTTTCCCCTGCACTGT-3′.

2.8. RNA-seq

5 × 106 cells per group were collected, and RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent. Next generation sequencing library preparations were constructed according to the manufacturer's protocol (NEBNext Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina). Sequencing was carried out by GENEWIZ on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform in 2 × 150 bp paired-end (PE) configuration.

2.9. Immunoblotting assay

Whole cell lysates were prepared with 1× cell lysis buffer (CST, 9803) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11873580001). Cell lysates were then sonicated and the soluble fractions were collected after centrifugation. The protein concentration was quantified by the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce, 23227). 20–30 µg of total protein was loaded for SDS-PAGE analysis. Transfered nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature.

2.10. RNA interference

Lentiviruses were prepared as described above. Targeted cancer cells were infected with lentivirus containing indicated shRNAs in the presence of 8 µg/µl polybrene, and were then selected by antibiotics for about two weeks to obtain stable transfected subclones. shRNAs targeting sequences were shown in supplemental Table 1.

2.11. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated knockout

HCT116 cells were subjected to CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of NIPBL. Cells were transfected with the lentiCRISPR v2 vector that expresses Cas9 and sgRNA targeting NIPBL using lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, 13778150) according to the manufacturer's guidelines, and then selected with puromycin treatment at 48 h post-transfection. Further, selected cells were plated into 96-well plates at a density to ensure one clone per well. The sorted knockout clones were obtained based on western blot and Sanger sequencing. sgRNAs targeting sequences used in this study were shown in supplemental Table 1.

2.12. Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using Trizol™ reagent, and was reversed into cDNA with PrimerScript™ RT reagent Kit (Takara, RR037A). Quantitative PCR was performed with NovoStart SYBR qPCR supermix using ABI-7500 instrument. GAPDH was used as an internal reference to normalize input cDNA. Specific primers used in this study were shown in supplemental Table 1.

2.13. Luciferase reporter assays

2 × 105 cells were seeded in each well of 24-well plates, and then transfected with 0.5 µg of pGL3-TYMS-promoter or pGL3-MYC-promoter construct and 0.05 µg of pRL-TK plasmid per well using lipofectamine 3000. After 24–36 h, relative luciferase units (RLU) were measured using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RLUs from firefly luciferase signal were normalized by RLUs from Renilla signal. Primers used in construction of TYMS and MYC promoter were shown in supplemental Table 1.

2.14. ChIP-PCR assays

ChIP experiments were performed in NUGC3 cells using the Simple ChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP kit (CST, 9003) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer sets were designed for ChIP-PCR primer within the promoters of the human TYMS. Primers used for PCR were shown in supplemental Table 1.

2.15. In vivo tumour xenograft models

All manipulations on the animal are performed following the guidelines approved by the institutional biomedical research ethics committee of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences. All animals were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility. For xenograft models, 4-week-old female BALB/c athymic mice were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd., allowing one or two week's adaptation period after arrival. 3 × 106 NUGC3 cells, 4 × 106 HCT116, RKO or NCC-59 cells were injected subcutaneously in the right lateral flank of athymic mice. To inducible knockdown NIPBL in vivo, 2 mg/ml doxycycline and 5% sucrose were added to the drinking water 23 days after tumour inoculation. Doxycycline-containing water was changed every 3 days. Mice were then treated with 1× PBS or 10 mg/kg RTX by intraperitoneal injection, five times per week for 2–3 cycles. The tumour size was measured by an electronic caliper, and the tumour volume was calculated using the following the formula: tumour volume = 1/2 × length × width2.

2.16. Patient data acquisition and analysis

There are 393 tumour samples available for analysing both mutation and CNA status of MYC, TYMS and cohesin complex members, 354 tumour samples available for analysing MYC and TYMS mRNA levels and 108 patient cases available for analysing clinical responses to TYMS inhibitors (supplemental Table 3) in TCGA provisional stomach database. There are 220 colorectal tumour samples available for analysing both mutation and CNA status of MYC, TYMS and cohesin complex members in TCGA provisional colorectal database. All the data can be accessed through GDC, cbioportal and proteinatlas websites, which is publicly open to global researchers with no further requirement of patient consent.

2.17. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± SD. The significance is determined by two-tailed Student's t-test and different levels of statistical significance were denoted by p-values (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Pearson's correlation analyses were used to calculate the regression and correlation between MYC and TYMS mRNA expression levels.

2.18. Availability of data

The GeCKO library and RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE123364 and GSE137253, respectively. All relevant data supporting the key findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

3. Results

3.1. Thymidylate synthase is an important therapeutic target for treating gastrointestinal cancer

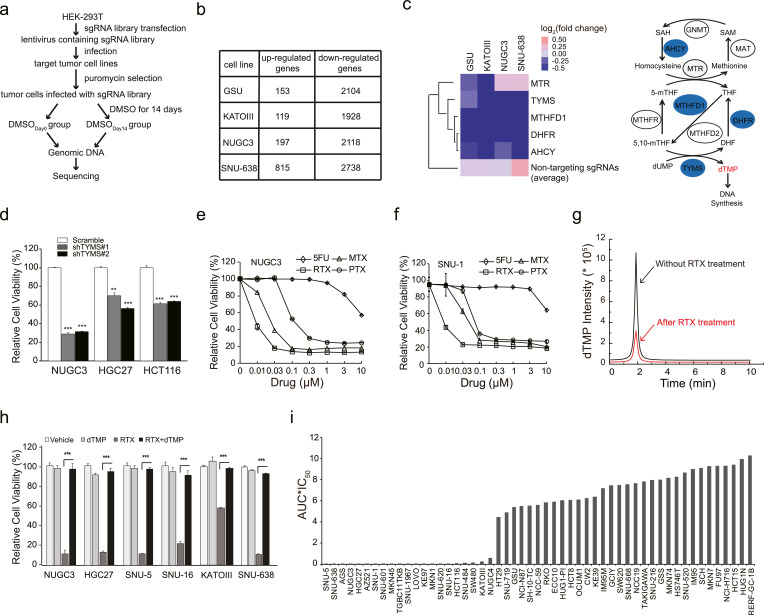

To explore the potential therapeutic targets for treating gastrointestinal cancer, we applied GeCKO screening to identify the key genes responsible for maintaining the survival of gastrointestinal cancer cells. As shown in Fig. 1(a), cells were infected with lentivirus containing 65,383 sgRNAs targeting 19,050 genes at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.4, and then were treated with puromycin for 7 days to remove uninfected cells, as well as allowing enough time for genome editing. After selection, cells were divided into two groups: one group (termed as DMSODay0) was harvested without any further treatment, and the other group was treated with 0.1% DMSO for another 14 days (termed as DMSODay14). Then, all the genomic DNA from two groups of each cell line was extracted individually, and was sequenced by Illumina HiSeq X Ten after the amplification of barcoded-PCR (Fig. 1(a)). The GeCKO screening was individually performed in four gastrointestinal cancer cell lines including GSU, KATOIII, NUGC3 and SNU-638, which was served as a 0.1% DMSO vehicle control with no significant influence on the cell growth [32, 33].

Fig. 1.

Thymidylate synthase is an important therapeutic target for treating gastrointestinal cancer. (a) The workflow of GeCKO screening in four gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. (b) The number of upregulated genes (average fold change>1.5 with duplicate sgRNAs) and downregulated genes (average fold change<0.6 with duplicate sgRNAs) in each round of GeCKO screening of each cell line. (c) Heat map of ‘one carbon pool by folate’ pathway. The average of 1,000 non-targeting sgRNA was used as control. The schematic diagram of one carbon pool by folate was shown in the right panel. Enzymes selected from the library screen data were annotated in blue circles. 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT), S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (AHCY), methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT), the tri-functional C1-synthase enzyme incorporating the activities of formyl-tetrahydrofolate (THF) synthetase, cyclohydrolase and dehydrogenase activities (MTHFD1), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). (d) The cell viability of NUGC3, HGC27 and HCT116 cells treated with RTX were detected by an MTT assay. The cell viability of NUGC3 (e) or SNU-1 (f) cells were decreased after treated with 5FU, RTX, PTX, or MTX, respectively. (g) The dTMP concentration of NUGC3 cells were detected by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) after RTX treatment. Area under the curve (AUC) indicates the dTMP concentration. Red peak: 8 nM RTX treatment group. Black peak: 0.1% DMSO treatment group. Treatment time: 72 h. (h) dTMP efficiently rescued the cell viability of indicated cell lines when treated with RTX. Vehicle: 0.1% DMSO, RTX: 10 nM, dTMP: 20 µM. (i) The cell viability of multiple gastrointestinal cancer cell lines under the treatment of RTX. IC50 multiplied by AUC of RTX treatment was presented in this study. IC50: half maximal inhibitory concentration. AUC: area under the curve. The IC50 and AUC were calculated according to dose response curves. All the experiments were repeated at least three times, and data are represented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, p value was calculated with two-tailed Student's t-test.

After data analysis, we observed that 119–815 out of 19,050 genes would boost tumour cell growth when they were knockout (folds in average >1.5 with duplicated sgRNAs in a single screening), and 1,928–2,738 out of 19,050 genes will severely impair gastrointestinal cancer cell survival when they were depleted (folds in average <0.6 with duplicated sgRNAs in a single screening) (Fig. 1(b)). To identify potential therapeutic targets for treating gastrointestinal cancer, we chose the down-regulated candidates to perform more analysis. Among them, most candidates are related to mitochondrial electron transport chain protein, tRNA synthetase, RNA polymerase, ribosomal protein, and proteasome protein, which are well-known essential genes for maintaining the survival of normal cells. After excluding these genes, we identified that sgRNAs targeting genes belonging to one carbon pool by folate, such as TYMS, MTHFD1, DHFR, AHCY and MTR, were significantly decreased in DMSODay14 group when compared with DMSODay0 group (Figs. 1(c) and S1). The average fold change of 1,000 non-targeting sgRNAs that were ranged from 1.03 to 1.30 in all the four gastrointestinal cancer cell lines was used as an internal control, indicating that non-targeting sgRNAs had no significant change on the survival of gastrointestinal cancer cells. Meanwhile, sgRNAs targeting genes involved in KEGG-defined pyrimidine metabolism pathway were also markedly decreased (Fig. S2). Interestingly, we found that TYMS gene, encoding thymidylate synthase catalyzing the methylation of dUMP to dTMP using 5′,10′-mTHF as the methyl donor, was both shared by one carbon pool by folate and pyrimidine metabolism pathways, suggesting that thymidylate synthase might be essential for gastrointestinal cancer survival.

Expectedly, TYMS knockdown significantly decreased the growth of NUGC3, HGC27 and HCT116 cell lines, supporting that TYMS is critical for the survival of gastrointestinal cancer (Fig. 1(d)). Furthermore, we selected four currently available TYMS inhibitors including three antifolate drugs (RTX, PTX and MTX) and one dUMP mimetics (5FU) to compare their therapeutic efficacies in gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. Among all the tested drugs, RTX had the best inhibitory effects in both NUGC3 and SNU-1 cell lines (Fig. 1(e) and (f)). In order to verify whether thymidylate synthase is selectively inhibited by RTX, we detected the cellular dTMP concentration upon RTX treatment. RTX at 8 nM significantly decreased the cellular dTMP concentration in NUGC3 cells compared with vehicle (Fig. 1(g)). More importantly, the inhibitory effects of RTX could be almost completely abolished by the addition of exogenous dTMP in multiple gastrointestinal cancer cell lines (Fig. 1(h)), demonstrating that thymidylate synthase is a major therapeutic target of RTX. Furthermore, RTX potently inhibited the cell viability of 22 out of 53 gastrointestinal cancer cell lines, which surpassed another two antifolate drugs (Figs. 1(i), S3a and S3b). Taken together, these data suggest that thymidylate synthase is an important therapeutic target for treating gastrointestinal cancer, which is selectively inhibited by antifolate drugs like RTX.

3.2. Genome-wide scale screening reveals that MYC is responsible for maintaining the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer cell to RTX

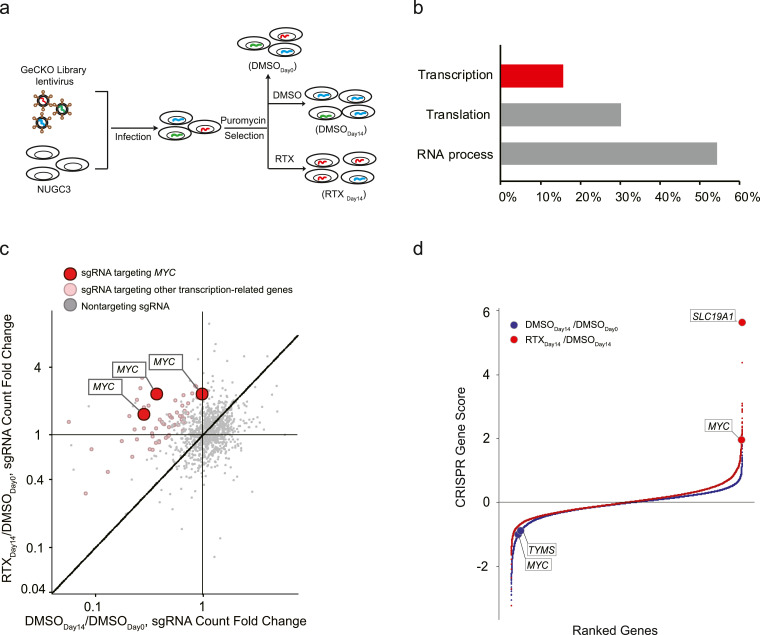

To identify key genes that determine the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer to RTX, we performed another round of GeCKO screening in NUGC3 cells with the application of RTX. Similar experimental procedures were used as described above, except that cells were divided into three groups (Fig. 2(a)). 2 × 107 cells were directly harvested after puromycin selection as DMSODay0 group, and the remaining cells were treated with either 0.1% DMSO (termed as DMSODay14) or 10 nM RTX (termed as RTXDay14) for another 14 days, respectively. In order to keep 300-fold coverage of GeCKO library, at least 2 × 107 cells per group were harvested at the end point of the treatment. Then, all the genomic DNA from three groups was extracted individually, and was sequenced after PCR amplification with different barcode primers (Fig. 2(a)).

Fig. 2.

Genome-wide scale screening identified the key regulators for maintaining the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer cells to RTX. (a) The work flow of GeCKO screening in NUGC3 cells with the supplement of 10 nM RTX. (b) Gene Ontology (GO) analysed the genes with duplicated sgRNA hits in top 5,000 candidates (FDR < 0.05). The percentages of three subgroups (transcription, translation and RNA process) were 15.6%, 30.2% and 54.2%, respectively. (c) sgRNAs targeting MYC were shown as red dots, sgRNAs targeting other transcription-related genes in (b) were shown as pink dots and the non-targeting controls were shown as grey dots. Data were analysed using a MAGeCK algorithm. See also supplemental Table 2. (d) Candidate genes were presented as red dots in RTXDay14/DMSODay0 and blue dots in DMSODay14/DMSODay0. CRISPR Gene Score (CS) is calculated by the following formula: CS= average [log2(RTXDay14 sgRNA abundance/DMSODay14 sgRNA abundance)] or average [log2(DMSODay14 sgRNA abundance/DMSODay0 sgRNA abundance)].

We chose top 5,000 candidates (FDR < 0.05, with duplicated hits) to perform gene ontology analysis, and found that genes targeted by these sgRNAs were clustered in three subgroups: transcription, translation and RNA process (Fig. 2(b) and supplemental Table 2). Using MAGeCK algorithm [30], we further identified that MYC, which belongs to COSMIC-defined Cancer Gene Census (Tier 1) with documented activity relevant to cancer [34], was the most favorable candidate among all the transcription-related genes due to the high mutation frequency of MYC amplification in stomach (53/393 cases, 13.2%) and colorectal (14/220 cases, 6.4%) adenocarcinomas (Figs. 2(b), (c) and S4). Using another CRISPR score analysis [31], we observed that sgRNAs targeting MYC were again selected out in insensitive parts (Fig. 2(d)). Consistently, sgRNAs targeting MYC and TYMS were significantly reduced in the DMSODay14 group when compared with DMSODay0 group, suggesting that both MYC and TYMS are required for the survival of NUGC3 cells (Fig. 2(d)). It's worth mentioning that SLC19A1, a folate transporter responsible for the uptake of THF cofactors and hydrophilic antifolates [35], was positively selected out in the insensitive part (Fig. 2(d)), suggesting that our screening data is reliable. Based on these data, we hypothesized that MYC is a key gene to determine the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer cell to RTX.

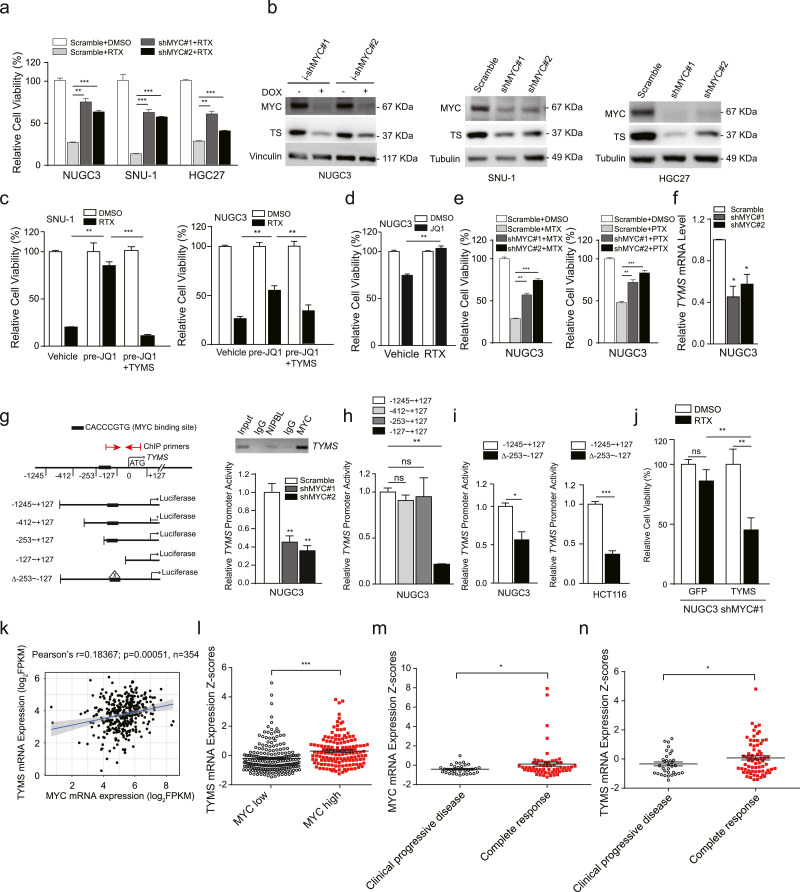

3.3. MYC predetermines the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer cell lines to antifolate drugs through regulating TYMS transcription

To examine whether MYC is responsible for maintaining the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer cells to RTX, we chose MYC-activated cancer cell lines for MYC silencing and observed that shMYC stably expressed NUGC3, SNU-1 and HGC27 cell lines were less sensitive to RTX compared with scramble (Fig. 3(a)). MYC knockdown as well as MYC inhibitor JQ1 markedly decreased the protein expression levels of both MYC and TYMS (Fig. 3(b) and S5a). As expected, the sensitivity of both SNU-1 and NUGC3 cells to RTX were also largely abolished when pre-treated with JQ1 (Fig. 3(c)). To our surprise, JQ1 was no longer able to inhibit the cell viability of NUGC3 cells after pre-treatment with RTX (Fig. 3(d)). At the same time, co-treatment of JQ1 and RTX exhibited no additive therapeutic effects in both SNU-1 and NUGC3 cells (Fig. S5b). In addition, MYC inhibition also reduced the sensitivity of NUGC3 cells to another two antifolate drugs such as MTX and PTX (Fig. 3(e)). These data support that MYC plays a critical role in maintaining the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer cells to antifolate drugs, and TYMS is a major downstream target of MYC.

Fig. 3.

MYC predetermines the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer cells to antifolate drugs through regulating TYMS transcription. (a) After stably transfected with shMYC or scramble, cells were treated with RTX for three days and the cell viability was determined by an MTT assay. (b) The protein expression levels of thymidylate synthase (TS) in NUGC3, SNU-1 and HGC27 after MYC was knocked down. (c) After pre-treatment with JQ1 for 72 h, the cell viability of SNU-1 and NUGC3 cells to RTX was determined by an MTT assay, and GFP+ cell number counting was used to measure the therapeutic efficacy of RTX in TYMS-GFP transfected cells. 1 µM and 10 µM JQ1 was used for treating SNU-1 and NUGC3 cells, respectively. (d) After pre-treatment with RTX, the cell viability of NUGC3 cells to 10 µM JQ1 was determined by an MTT assay. NUGC3 cells were gradually treated with RTX from 1 nM to 90 nM in 2 months. (e) The cell viability of shMYC stably expressed NUGC3 cells was determined after treatment with MTX and PTX for three days. (f) The TYMS mRNA expression levels in NUGC3 cells after MYC knockdown, normalized with GAPDH mRNA expression levels. (g) The luciferase activity of TYMS promoter in NUGC3 cells was measured after MYC knockdown (bottom right). Results are represented as normalized relative luciferase activity with Renilla luciferase activity. MYC was immunoprecipitated with indicated DNA regions of TYMS promoter detected by ChIP-PCR (upper right). (h) The relative luciferase activity of truncated TYMS promoter fragments. (i) The relative luciferase activity of MYC binding site-deleted fragment in NUGC3 and HCT116 cells. (j) The cell viability of TYMS-GFP transfected NUGC3 shMYC cells was determined by GFP+ cell number counting after treatment with RTX. (k) Pearson correlation analysis of the correlation of the MYC mRNA expression versus the TYMS mRNA expression in the TCGA gastric cancer patient samples according to the proteinatlas website. (Pearson's r = 0.18367; p = 0.00051, n = 354). (l) The TYMS mRNA expression levels of MYC-high samples (n = 142) and MYC-low samples (n = 212), the same samples were used in (k). (m and n) The MYC (m) and TYMS (n) expression levels in gastric tumours patients who are complete response or clinical progressive disease to TYMS inhibitors in the clinical setting. The drug response data were downloaded from GDC-TCGA database, and mRNA data was retrieved from proteinatlas website. Clinical progressive disease, n = 32 (MYC), n = 33 (TYMS). Complete response, n = 59 (MYC) or n = 69 (TYMS). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, p value was calculated with two-tailed Student's t-test.

Next, we asked how MYC regulates TYMS gene expression. Our qPCR data showed that MYC silencing significantly decreased the mRNA expression levels of TYMS gene (Fig. 3(f)). Then, we cloned the −1,245 to +127 bp DNA fragment from the ATG site of TYMS promoter into pGl3-basic-luciferase vector, and found that the luciferase activity of this fragment was significantly reduced when MYC was knocked down (Fig. 3(g), bottom right). After truncated, we identified that the E-box located within −253 to −127 bp from ATG site was responsible for MYC binding activity (Fig. 3(h)). It was further evidenced that depletion of −253 to −127 bp fragment significantly decreased the luciferase expression of the TYMS promoter (Fig. 3(i)). Chromatin-immunoprecipitation data also revealed that MYC was bound to this region of TYMS promoter (Fig. 3(g), upper right). More importantly, TYMS overexpression restored the sensitivity of NUGC3 shMYC cells as well as JQ1-pretreated SNU-1 and NUGC3 cells to RTX (Fig. 3(c) and (j)). In the clinical setting, the TYMS mRNA expression levels were positively correlated with MYC mRNA expression levels in TCGA stomach tumour samples (Pearson's r = 0.18367, p = 0.00051, n = 354, Fig. 3(k)). Meanwhile, the TYMS mRNA levels were significantly higher in MYC-high patient tumour samples than that of MYC-low samples (p < 0.001, Fig. 3(l)). Finally, we asked whether MYC/TYMS expression is correlated with the therapeutic responses of thymidylate synthase inhibitors in the clinic. We collected 108 gastric cancer patient cases with available drug response data from TCGA provisional stomach database (supplemental Table 3), and found that patients who had complete responses to TYMS inhibitors had significantly higher MYC mRNA expression levels in tumours than that of clinical progressive diseases (p < 0.05, Fig. 3(m)). Consistently, patients with complete responses had higher TYMS mRNA expression levels in tumours than that of clinical progressive disease (p < 0.05, Fig. 3(n)). Based on our data, we conclude that MYC acts as a key transcription factor regulating the transcription of thymidylate synthase, and patients with high MYC/TYMS expression in tumours will be more sensitive to antifolate drugs like RTX.

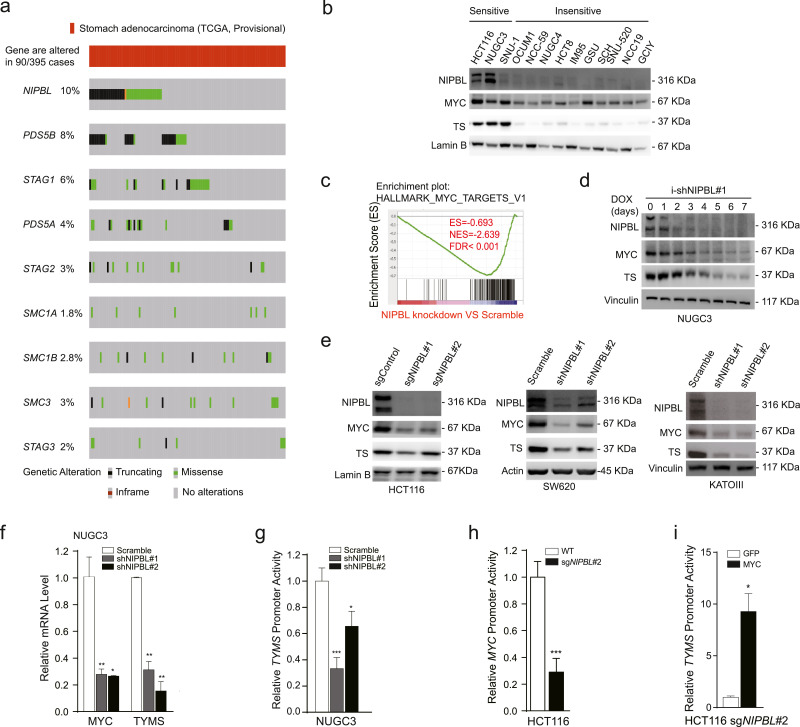

3.4. NIPBL loss inhibits TYMS transcription through downregulating MYC bioactivity

Because MYC gene is barely inactively mutated in patient tumour samples, we asked whether other genetic mutations will impair the biological activity of MYC. After analysed with TCGA data, we identified that cohesin complex members responsible for maintaining gene transcriptional activity are frequently mutated in gastrointestinal tumours (Fig. 4(a) and Fig. S6). Among them, NIPBL, a cohesin loading factor, is the top mutated candidate. It was well supported by the fact that gastrointestinal cancer cell lines that were insensitive to RTX exhibited little or no expression of NIPBL protein compared with sensitive ones, accompanied with reduced MYC and TYMS protein expression (Fig. 4(b)). By retrieving the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database [36] and validating with Sanger sequencing, we confirmed that RTX-insensitive NCC-59, SNU-520, RKO, CW2 and HCT15 cell lines had the NIPBLp.K603fs frameshift mutation (Fig. 1(i) and data not shown). Based on these data, we asked whether NIPBL deficiency could affect the transcription activity of both MYC and TYMS.

Fig. 4.

NIPBL loss inhibits TYMS transcription through downregulating MYC bioactivity. (a) Mutation status of cohesin complex and -associated members in TCGA provisional stomach database. 395 tumour samples are available for analysing the mutation status of cohesin complex members. (b) The protein expression of NIPBL, MYC and thymidylate synthase were detected in multiple gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. (c) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of NIPBL knockdown versus scramble in NUGC3 cells. (d) Indicated proteins were detected within 7 days using immunoblotting after inducible knockdown of NIPBL. (e) Indicated proteins were detected by immunoblotting after NIPBL was knocked down in another three gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. (f) The MYC and TYMS mRNA expression levels were detected by real-time PCR in NUGC3 cells after NIPBL knockdown, normalized with GAPDH mRNA expression levels. (g) The luciferase activity of TYMS promoter was detected in NUGC3 cells after NIPBL knockdown. (h) The luciferase activity of MYC promoter (−3,255 to −1,719 from ATG site) was detected in HCT116 cells after NIPBL knockout. (i) The luciferase activity of TYMS promoter was detected after MYC was overexpressed in NIPBL knockout HCT116 cells. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, p value was calculated with by two-tailed Student's t-test.

After analysis of the RNA-seq data with Gene Set Enrichment Analysis [37], we identified that the gene signature of MYC_targets was the top negatively selected one when comparing NIPBL knockdown with scramble in NUGC3 cells (FDR < =0.001, Fig. 4(c)). As expected, inducible knockdown of NIPBL decreased both MYC and TYMS protein expression levels (Fig. 4(d)). Similar results were obtained in another three gastrointestinal cancer cell lines when NIPBL was either knockout or knockdown (Fig. 4(e)). Consistently, NIPBL knockdown reduced the mRNA expression levels of both MYC and TYMS genes (Fig. 4(f)). At the same time, we cloned −1,223 to +313 DNA fragment from the transcription start site (TSS) of MYC promoter into pGl3-basic-luciferase vector, and found that NIPBL knockout/knockdown reduced the luciferase expression of both MYC and TYMS promoters (Fig. 4(g) and (h)). To further approve whether MYC is indispensable for NIPBL-regulated TYMS transcription, we re-introduced MYC into NIPBL-knockout HCT116 cells and observed that the luciferase activity of TYMS promoter was enhanced about 10-fold when MYC was restored (Fig. 4(i)), supporting that NIPBL transcriptionally regulates TYMS expression via MYC. Taken together, we conclude that NIPBL loss attenuates TYMS transcription through inactivating MYC.

3.5. NIPBL loss attenuates the therapeutic effects of RTX in vitro and in vivo

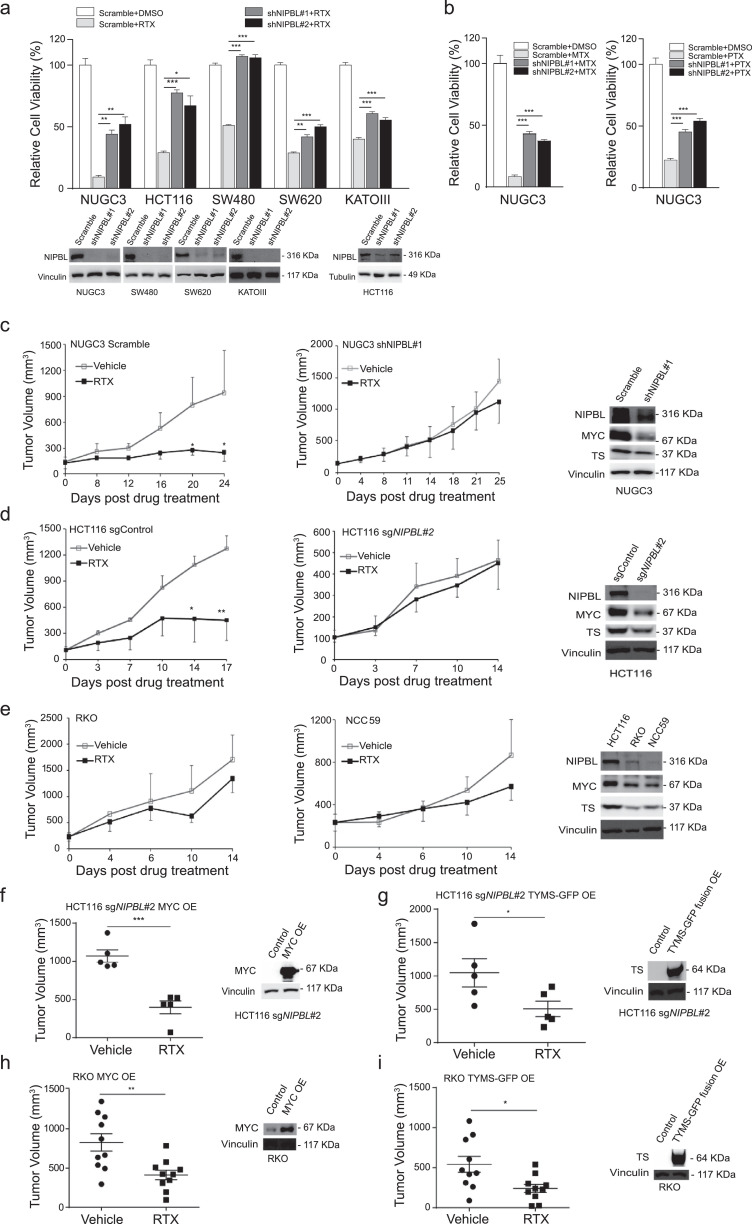

After shNIPBL stably expressed, multiple gastrointestinal cancer cell lines became less sensitive to RTX (Fig. 5(a)). The knockdown effects of shNIPBL were shown in the bottom of Fig. 5(a). In addition, NIPBL knockdown also impaired the sensitivity of NUGC3 cells to another two antifolate drugs compared with scramble (Fig. 5(b)), supporting our notion that gastrointestinal cancer cell lines harbouring NIPBLp.K603fs mutation are insensitive to RTX (Fig. 1(i)).

Fig. 5.

NIPBL loss attenuates the therapeutic responses of RTX in vitro and in vivo. (a) The sensitivity of multiple gastrointestinal cancer cell lines to RTX after NIPBL knockdown. The knockdown effects were shown in the bottom. (b) The cell viability of NUGC3 cells to MTX and PTX was determined after NIPBL knockdown. (c) RTX significantly inhibited the tumour growth of NUGC3 tumour xenografts in nude mice compared with vehicle, but failed to inhibit the tumour growth of NUGC3 tumour xenografts in vivo when NIPBL was knockdown using a doxycycline-inducible shRNA. Vehicle group, n = 9; RTX group, n = 9. The knockdown effect of NIPBL in tumour xenografts was shown in right panel. (d) RTX effectively reduced the tumour growth of HCT116 tumour xenografts in nude mice, but failed to inhibit NIPBL-knockout HCT116 tumours in vivo. The knockout effect of NIPBL in tumour xenografts was shown in the right panel. (e) RTX failed to inhibit the growth of NIPBLp.K603fs-mutated RKO and NCC-59 tumour xenografts in vivo. The expression of NIPBL, MYC and TYMS in tumour xenografts were shown in the right panel. (f-g) RTX significantly reduced the tumour growth of NIPBL-knockout HCT116 tumour xenografts with exogenously expressed MYC (f) or TYMS (g) compared with vehicle. The protein expression levels of MYC and TYMS were shown in the right panel. (h-i) After exogenously expressed with MYC (h) or TYMS (i), RTX significantly inhibited the tumour growth of NIPBLp.K603fs mutated RKO tumour xenografts with exogenously expressed MYC or TYMS compared with vehicle. The protein expression levels of MYC and TYMS were shown in right panel. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, p value was calculated by two-tailed Student's t-test.

Next, we examined whether NIPBL loss would affect the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer to RTX in vivo. As shown in Fig. 5(c), RTX significantly reduced the tumour growth of NUGC3 tumour xenografts in athymic mice (p < 0.05), but failed to inhibit that of NIPBL knockdown tumours (p > 0.05). The knockdown effect of NIPBL in tumour tissue by orally administration of doxycycline was shown in the right panel of Fig. 5(c). We obtained similar results using another NIPBL knockout HCT116 tumour xenograft model, demonstrating that NIPBL loss will impair the sensitivity of gastrointestinal cancer to RTX compared with control (Fig. 5(d)). The knockout effect of NIPBL protein was shown in the right panel of Fig. 5(d). It's worth mentioning that the growth of MYC-overexpressing HCT116 cell line was more sensitive to NIPBL loss than NUGC3 cells that probably dues to the high mRNA expression levels of MYC and TYMS (Fig. S7). In addition, we selected another two gastrointestinal cancer cell lines harbouring NIPBLp.K603fs mutation to examine their response to RTX in vivo. As expected, neither RKO nor NCC-59 tumour xenografts responded to RTX (both p > 0.05, Fig. 5(e)).

To further explore whether MYC or TYMS is responsible for maintaining the sensitivity of gastrointestinal tumours. NIPBL-knockout HCT116 cells were exogenously expressed with MYC or TYMS-GFP fusion gene and were subcutaneously transplanted into the right flank of nude mice. The in vivo data showed that both MYC- and TYMS-exogenously expressed tumour xenografts were significantly inhibited by RTX treatment compared with control (Fig. 5(f) and (g)). The exogenously expression levels of MYC and TYMS-GFP fusion proteins were shown in the right panel. We also obtained similar results in NIPBLp.K603fs mutant RKO cells when MYC and TYMS was re-introduced (Fig. 5(h) and (i)).

In summary, our study reveals that MYC is a key transcription factor regulating TYMS transcription and makes gastrointestinal cancer hypersensitive to RTX. Of note, gastrointestinal cancer patients with high MYC/TYMS levels in tumours would likely benefit more from TYMS inhibitors, while NIPBL-mutated gastrointestinal tumours lost their sensitivity to RTX through blocking MYC-mediated TYMS transcription.

4. Discussion

In this study, we identify that MYC is a key gene responsible for maintaining the sensitivity of gastrointestinal tumours to antifolate drugs. Importantly, we observed that MYC is amplified in 13.2% of stomach and 6.4% of colorectal adenocarcinomas, and NIPBL is mutated in 10.2% of stomach and 6.4% of colorectal tumour samples. Although TYMS has distinct protein expression pattern in MYC-high and NIPBL-null tumour subtypes, it would be difficult to distinguish with each other in the remaining subpopulations because TYMS gene per se has little or no genetic alternations in both gastric (1.0%) and colorectal (1.4%) cancer samples (Fig. S4a) [13, [38], [39], [40]]. In the literature, it's debatable whether the mRNA or protein expression levels of thymidylate synthase could be used as a biomarker for predicting the therapeutic efficacies of thymidylate synthase inhibitors in the clinical setting [13, [38], [39], [40]]. Like immunohistochemistry (IHC) for HER2 testing, it often produces different IHC test results for borderline samples due to the different rules for pathologist classifying positive and negative status, and can be greatly improved by FISH testing. It would be very helpful to examine the genetic mutations of MYC and NIPBL, together with IHC for TYMS testing, to improve the diagnostic accuracy and obtain better prediction when applying TYMS inhibitors to patients. Our work supports the notion that patients with high MYC/TYMS expression levels will have better therapeutic responses when treated with thymidylate synthase inhibitors compared with their counterparts.

Secondly, the genetic mutations of MYC and NIPBL are pretty dominant in gastric tumour samples rather than colorectal tumour cases (Fig. S4), which may explain why we can obtain the statistical significance when correlated clinical responses of TYMS inhibitors with the mRNA expression levels of MYC and TYMS in 102 gastric tumour cases, but not in 80 cases of colorectal tumour samples. It may require more colorectal tumour samples to perform the statistical analysis.

Thirdly, multiple TYMS inhibitors like 5FU, TS-1, capecitabine and RTX were clinically used for treating stomach and colorectal adenocarcinomas. Thus, it would be of value to explore which TYMS inhibitor has the best clinical outcome when treating MYC-high/TYMS-high patients, which couldn't be addressed in this study due to the limited patient cases.

Finally, our data suggest that thymidylate synthase inhibitors should be used to treat gastrointestinal cancer patients with high MYC/TYMS expression in tumours, avoiding their ineffective use for treating low MYC/TYMS expressed tumours that may be caused by genetic alternations like NIPBL mutation.

Funding sources

This work was financially supported by grants from National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1302400), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (16JC1406200), CAS_Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences (QYZDB-SSW-SMC034) and Strategic Priority Research Program (XDA12020210), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872890, 81322034 and 81372346) and the Recruitment Program for Professionals of China (J.Y.L.). All the funding agencies require no specific roles for this publication.

Author contributions

J.Y.L. conceived and designed the experiments. J.Y.L., T.T.L. and Y.M.H. wrote the manuscript. T.T.L., Y.M.H. and C.H.Y. performed the experiments and analysed the data. Y.J. and C.X.W. analysed the GeCKO screening data. X.M.C., X.W., J.Y.S. and Y.F.Z. performed the GeCKO screening.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank the excellent service of institutional core facilities including Molecular Biology and Biochemistry and laboratory animal technical platforms.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.10.003.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Graham D.Y. Helicobacter pylori update: gastric cancer, reliable therapy, and possible benefits. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(4):719–731. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.040. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre L.A., Bray F., Siegel R.L., Ferlay J., Lortet-Tieulent J., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng H., Zheng R., Guo Y. Cancer survival in china, 2003-2005: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(8):1921–1930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carreras C.W., Santi D.V. The catalytic mechanism and structure of thymidylate synthase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64(1):721–762. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langenbach R.J., Danenberg P.V., Heidelberger C. Thymidylate synthetase: mechanism of inhibition by 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridylate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;48(6):1565–1571. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90892-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarmula A. Antifolate inhibitors of thymidylate synthase as anticancer drugs. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2010;10(13):1211–1222. doi: 10.2174/13895575110091211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farber S., Diamond L.K., Mercer R.D., Sylvester R.F., JR, Wolff J.A. Temporary remissions in acute leukemia in children produced by folic acid antagonist, 4-aminopteroyl-glutamic acid (aminopterin) Br J Haematol. 1948;238(23):787–793. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194806032382301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocconi G., Cunningham D., Cutsem E.V. Open, randomized, multicenter trial of raltitrexed versus fluorouracil plus high-dose leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Tomudex Colorectal Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(9):2943–2952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogelzang N.J., Rusthoven J.J., Symanowski J. Phase iii study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(14):2636–2644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanna N., Shepherd F.A., Fossella F.V. Randomized phase iii trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moscow J.A. Methotrexate transport and resistance. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;30(3–4):215–224. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston P.G., Kaye S. Capecitabine: a novel agent for the treatment of solid tumors. Anticancer Drugs. 2001;12(8):639–646. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Gennaro E., Bruzzese F., Pepe S. Modulation of thymidilate synthase and p53 expression by hdac inhibitor vorinostat resulted in synergistic antitumor effect in combination with 5FU or raltitrexed. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8(9):782–791. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.9.8118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao R., Goldman I.D. Resistance to antifolates. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7431–7457. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackwell T., Kretzner L., Blackwood E., Eisenman R., Weintraub H. Sequence-specific dna binding by the c-Myc protein. Science. 1990;250(4984):1149–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.2251503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackwell T.K., Huang J., Ma A. Binding of myc proteins to canonical and noncanonical dna sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(9):5216–5224. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H., Liu H., Qing G. Targeting oncogenic myc as a strategy for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018;3(5) doi: 10.1038/s41392-018-0008-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kagey M.H., Newman J.J., Bilodeau S. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467(7314):430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorsett D. Roles of the sister chromatid cohesion apparatus in gene expression, development, and human syndromes. Chromosoma. 2007;116(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasmyth K., Haering C.H. Cohesin: its roles and mechanisms. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haering C.H., Gruber S. SnapShot: smc protein complexes part i. Cell. 2016;164(1–2):326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.026. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deardorff M.A., Bando M., Nakato R. HDAC8 mutations in cornelia de lange syndrome affect the cohesin acetylation cycle. Nature. 2012;489(7415):313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature11316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandoth C., Mclellan M.D., Vandin F. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502(7471):333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence M.S., Stojanov P., Mermel C.H. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature. 2014;505(7484):495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leiserson M.D., Vandin F., Wu H.T. Pan-cancer network analysis identifies combinations of rare somatic mutations across pathways and protein complexes. Nat Genet. 2015;47(2):106–114. doi: 10.1038/ng.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo G., Sun X., Chen C. Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing of bladder cancer identifies frequent alterations in genes involved in sister chromatid cohesion and segregation. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1459–1463. doi: 10.1038/ng.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber T.D., Kirk M.M., Yuen K.W.Y. Chromatid cohesion defects may underlie chromosome instability in human colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(9):3443–3448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712384105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanjana N.E., Shalem O., Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for crispr screening. Nat Methods. 2014;11(8):783–784. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shalem O., Sanjana N.E., Hartenian E. Genome-Scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343(6166):84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W., Xu H., Xiao T. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):554. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang T., Birsoy K., Hughes N.W. Identification and characterization of essential genes in the human genome. Science. 2015;350(6264):1096–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mokou M., Klein J., Makridakis M. Proteomics based identification of KDM5 histone demethylases associated with cardiovascular disease. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L., Wang J., Xiong H. Co-targeting hexokinase 2-mediated warburg effect and ULK1-dependent autophagy suppresses tumor growth of PTEN- and TP53-deficiency-driven castration-resistant prostate cancer. EBioMedicine. 2016;7:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tate J.G., Bamford S., Jubb H.C. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D941–D9D7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo W., Healey J.H., Meyers P.A. Mechanisms of methotrexate resistance in osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(3):621–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jordi B., Giordano C., Nicolas S. The cancer cell line encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483(7391):603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giovannetti E., Backus H.H., Wouters D. Changes in the status of p53 affect drug sensitivity to thymidylate synthase (TS) inhibitors by altering ts levels. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(5):769–775. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen J., Wang H., Wei J. Thymidylate synthase mRNA levels in plasma and tumor as potential predictive biomarkers for raltitrexed sensitivity in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(6):E938–E945. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Q., Shen J., Wang H. TS mRNA levels can predict pemetrexed and raltitrexed sensitivity in colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(2):325–333. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2354-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The GeCKO library and RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE123364 and GSE137253, respectively. All relevant data supporting the key findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.