Abstract

Background

Sepsis is a major global healthcare concern. Platelets and leucocytes play a key role in sepsis. Whole blood flow cytometry (FCM) is a powerful new technique for the assessment of leucocyte and platelet parameters and their functional state. In the present study, we have used FCM to examine platelet and leucocyte functions and parameters in sepsis patients.

Methods

Prospective, non-interventional cohorts of all adult patients with sepsis and history of intensive care unit stay for more than 24 h at mixed surgical- medical ICU were evaluated. The Simplified Acute Physiology Score-3 (SAPS 3) admission score was obtained, and whole blood FCM analysis of select platelets and leukocyte parameters were performed using a combination of monoclonal antibodies in a predefined panel. We also evaluated the correlation between these parameters and the severity of the illness, based on SAPS 3 admission score.

Results

Total leucocyte count (TLC) was statistically and significantly different between all the study samples, but platelet count was not. SAPS 3 acted as the best discriminant between the study groups. With a cut-off score of 55.5, SAPS 3 score predicted hospital mortality with a sensitivity of 82.8% and a specificity of 83.9%, with an area under receiver operating curves (AUROC) of 0.888 (95% CI = 0.807–0.969, p < 0.000). Parameters for CD62P, platelet-leucocyte aggregates (PLAs) and CD11b showed statistically significant differences between the patients and healthy volunteers. CD62P expression was positively correlated to PLA variables in severe sepsis patients. The median fluorescence intensity was found to be more informative than mean fluorescence intensity. New “62P adhesion index (62P AI)” and “PLA adhesion index” are proposed and is likely to be more informative.

Conclusion

SAPS 3 score was the most robust of the parameters evaluated. Our study suggest the idea that the incorporation of platelet and leucocyte activation parameters, rather than mere static counts, will add the existing prognostic model though we could not conclusively prove the same in this study.

Keywords: Sepsis, Platelets, Leucocytes, Whole blood flow cytometry, SAPS 3

Introduction

Despite advances in medical treatment, sepsis is one of the leading causes of death in intensive care units (ICUs).1 Sepsis can be defined as systemic inflammatory response syndrome that has a proven or suspected microbial aetiology. When sepsis is associated with dysfunction of organs distant from the site of infection, the patient has severe sepsis.2

The pathophysiology of sepsis is complex. Platelets and leucocytes play a key role in the inflammatory response and the coagulation dysfunction seen in sepsis.3 The pathophysiology and risk indicators associated with leucocyte activation, thrombocytopaenia and leucocyte–platelet dysfunction in adult sepsis patients is being gradually understood and is still in a nascent stage.4

Whole blood flow cytometry (FCM) allows for rapid, accurate and detailed means of evaluation of platelets and leucocytes in cases of sepsis/severe sepsis.5 In the present study, we have used FCM to evaluate platelet and platelet–leucocyte functional parameters in severe sepsis patients. We have measured the same in control groups and compared them. We also sought to understand the correlation between these parameters and the severity of the illness based on current standardised risk scoring systems for sepsis.

Material and methods

The present study was conducted in the Department of Pathology, of an urban tertiary-care teaching hospital. The study included prospective, cohorts of adult patients (more than 18 years old) with diagnosed severe sepsis and history of ICU stay for more than 24 h who were managed at a 20 bedded mixed surgical–medical ICU over 2 years period. During the period of the study, adult patients admitted to the ICU, who have an expected ICU stay longer than 24 h were screened for sepsis by independent staff physicians using standard diagnostic and clinical criteria and were included in the study. For sepsis patients, risk prognostic scoring data were recorded by using the Simplified Acute Physiology Score-3 (SAPS 3) stand-alone database system.6 Patients who had received blood/platelet transfusion within 2 weeks prior to admission, patients on antiplatelet medication and cases of diagnosed haematological malignancies were excluded from the study. The ICU control group was recruited from ICU patients admitted for other causes but without severe sepsis. Healthy controls were recruited from volunteers after informed consent. Relevant clinical details were noted for all the cases. The study procedures were approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Blood samples were obtained from patients and controls in sterile vacutainer tubes with appropriate anticoagulant by a standardised collection protocol to minimise platelet activation and aggregate formation.7 Routine blood parameters were studied on collected Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-anticoagulated sample in five part automated cell counters. For morphological examination, peripheral blood smear stained with Leishman stain was examined in all cases. Acid citrate dextrose (ACD) in special BD falcon tubes was used as anticoagulant for FCM.8 Whole blood FCM analysis was performed using monoclonal antibody (MAb) within 30 min of collection of blood. The samples were prepared and analysed as per protocol that was developed and validated in house to suit our requirements after carrying out multiple protocol development studies to validate the stability and repeatability of the FCM measurements for platelets and platelet–leucocyte aggregates (PLAs) using the samples from healthy controls to establish normal ranges for platelet activation markers and PLA. Prior fixation was avoided on samples (after carrying out various in house trials). For PLAs formation, unfixed sample was finally selected for study. Collected blood sample was incubated with MAb reagents for 20 min at room temperature without agitation, and 1% paraformaldehyde fixative was added after incubation with antibody. FCM analysis was done using a combination of MAbs in predefined panel (Table 1). All antibodies were used at optimal concentrations as determined by titration experiments. FCM evaluation was carried out using a four colour BD FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Fullerton, CA) using the Cell Quest pro software. Separate staining protocols were followed for platelets and PLAs.

Table 1.

Panel of tubes with fluorescent-labelled antibody markers.

| Tube no | Unstained blood (μl) | FITC | PE | Per CP | APC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 μl + 1% 1 ml paraformaldehyde | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 5 μl | 10 μl G1 | 10 μl G1 | – | 5 μl G1 |

| 3 | 5 μl | 10 μl CD154 | 10 μl CD62P | – | 5 μl CD41a |

| 4 | 50 μl | 10 μl G1 | 10 μl G1 | 10 μl CD45 | – |

| 5 | 50 μl | 10 μl CD42a | 10 μl CD14 | 10 μl CD45 | – |

| 6 | 50 μl | 10 μl 11b | – | 10 μl CD45 | – |

FITC: fluorescein isothiocynate; PE: phycoerythrin; Per CP: peridinin chlorophyll protein complex; APC, allophycocyanin.

Flow cytomytry (FCM) immunophenotyping was performed by collecting 10,000 ungated list mode events. The four-colour analysis enabled discrimination of platelet-coupled and platelet-free leucocytes and calculation of the percentage of PLAs in the leucocyte population. Neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes and platelets were identified using the logical gating facility in forward and side scatter by a combination of cell size and granularity, as well as binding characteristics of anti-CD45 (pan-leucocyte marker), anti-CD14 (monocyte marker) and anti-CD41a and anti-CD42a (platelet marker). Binding of antibody against the α-subunit of the leucocyte MAC-1 integrin (CD11b) and CD14 was used to determine status of activation of circulating neutrophils and monocytes. Binding of an antibody against the expressed platelet surface α-granule protein P-selectin (CD62P greater than that of normal control was taken as a measure of platelet activation). Similarly CD154 was evaluated on platelets.

Separate scatter plots were created for platelets and platelet–leucocyte aggregates. Four decade logarithmic amplification scale was used. Quadrant was put on the dot plots and the plots formatted for the appropriate gate. Statistical data were asked for dot plots. The fixed quadrant was placed at 101 X-axis and 101 Y-axis. The current/gain in the is photomultiplier tube (PMTs) was so adjusted that the isotype control (Fig. 4A and B) cells fell in the lower left (LL) region of the quadrant. The analysis was done with the following interpretation: LL = negative, UR = positive for both X and Y, LR = positive for X, UL = positive for Y axes, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Flow cytometry dot plots. (A) Sepsis patient platelet activation analysis. (B) Sepsis patient platelet–leucocyte aggregate and monocyte–platelet aggregate analysis. FITC: fluorescein isothiocynate; PE: phycoerythrin; Per CP: peridinin chlorophyll protein complex; APC, allophycocyanin.

A suitable gating strategy was used to define the subpopulation of interest. For example, in all leucocyte-related study, CD45 was used as a pan leucocyte marker in combination with CD41a as a general platelet marker when studying platelet functions (CD62P and CD154). In leucocyte–platelet adhesion studies, CD42a was used as a platelet marker along with CD45 and CD 14 (monocyte marker) based on prior trials. Subgating plots with CD14 and CD42a gave us platelet–monocyte adhesions (Table 1). PLAs were defined as leucocytes that had bound anti-CD42a (platelet marker) in addition to the appropriate leucocyte markers. The percentage of platelet-conjugated monocytes (platelet–monocyte aggregates [PMAs]) was measured by analysis of the CD 14-positive individual white cell subpopulations.

During analysis, a gating strategy similar to sample acquisition was also applied separately for platelet and platelet leucocyte conjugates. Quadrant was put on the second dot plot of each set, and the plot was formatted for appropriate gate. The data from the acquired list mode were superimposed to the respective first dot plots. This quadrant was copied to the rest of dot plots, and all the plots formatted for appropriate gate. The statistics of the each second dot plot was asked for. The data from the acquired list mode in the respective dot plots were superimposed. The statistics were calculated for the plots. The statistical data displayed below the respective dot plots showed the percentage positivity of the cells of respective antibodies in each dot plot (Fig. 4A and B). The measurement of variables was expressed as percentage of positive cells and/or mean fluorescence intensity (MeFI) and median fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Statistical analysis

The study population (100) was divided into three groups:

Group 1—Severe sepsis patients (30).

Group 2—Healthy individuals (40).

Group 3—ICU patients not in severe sepsis (30).

The data were analysed using SPSS, version 20.0, for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was carried out for all the relevant parameters after calculating test for variance (Levene's). A post hoc test with Bonferroni (at alpha of 0.05) was also done (except for SAPS 3 score). A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Tests for normality of the SAPS 3 scores data including visual plots, normal Q–Q plots, box plots and Shapiro–Wilk's test were carried out. Similarly subgroup analysis between survivors and non-survivors was done. Correlation tests were also carried out for various parameters in Group 1 and 3 (intergroup and intragroup) Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated for the SAPS 3 scores to calculate the cut-off values and develop a prediction score. A logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict survival for 60 patients using SAPS 3 score as predictor, including the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The model (SAPS score) was then statistically evaluated to assess its ability to predict and reliably distinguish between survivors and non-survivors and calculate the odds ratio for such a score.

Results

Out of the 30 severe sepsis cases, 21 (69%) patients were male and 9 (31%) were female. Within 40 healthy individuals, the male population was 17 (42.5%), and females were 23 (57.5%). Out of the 30 non-sepsis ICU cases, 23 (76.5%) were male, and 7 (23.5%) were females. The mean age of the severe sepsis patients (group 1) was 54.2 years with age range 21–88 years. Mean age for healthy individuals (Group 2) was 24.5 years with age range 19–44 years. The mean age of the ICU non-severe sepsis patients (Group 3) was 47.6 years with age range 19–85 years. The values of the various measured general parameters are as in Table 2. Total leucocyte count (TLC) was statistically different between all the groups (ANOVA of 0.00 between groups 1 and 2, 3 and 0.02 between groups 2 and 3) but platelet count was not. The values of the various measured flow cytometric parameters are as in Table 3. Parameters (percentage of cells, MFI and index) for CD62P, PLA and CD11b, on post hoc analysis, showed statistically significant differences between the patients (groups 1, 3) and healthy volunteers (Group 2)(ANOVA of <0.05) but no significance difference was observed between group 1 and 3. The MeFI was not significant in most parameters between the groups. CD62P MeFI value is higher in sepsis patients than healthy individuals, though platelet activation measured as CD62P MeFI (mean fluorescence intensity) showed no statistically significant differences between both patient groups. The MFI was found to be more informative than MeFI. A new “62 P adhesion index (62P AI)” is proposed which is a multiplication factor of CD62P expression in percentage positive platelets and CD62P MFI score. The new index may be more informative and a robust reproducible parameter than either the cell count or the fluorescence value in isolation, as the biological effect is the function of number of activated platelets and their level of activation represented by fluorescence intensity. The parameters for CD154 and monocyte–platelet adhesion did not show any significant difference between the groups. PLA% also did not show statistically significant difference between the patient groups, but measurement of PLA% was higher in sepsis patients than the healthy individuals. A new “PLA adhesion index” is proposed which is a multiplication factor of PLA % and PLA MFI. The new index may be more representative of the pathophysiology like in 62P AI. Though both these indices showed statistically significant differences between the patients (groups 1, 3) and healthy volunteers (group 2), there was no significance between group 1 and 3.

Table 2.

Descriptive data of measured general parameters.

| Variables | Severe sepsis patients (Group 1) (N = 30) |

Healthy volunteers (Group 2) (N = 40) |

ICU patients not in severe sepsis (Group 3) (N = 30) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

| Age (in years) | 53 | 17 | 20 | 11 | 45.5 | 21 |

| TLC | 15065 | 8000 | 6905 | 1210 | 11300 | 8560 |

| Platelet count | 152000 | 181750 | 232500 | 279000 | 217000 | 105000 |

IQR: interquartile range; TLC: total leucocyte count; ICU: intensive care unit.

Table 3.

Study descriptive of measured flow cytometric parameters.

| Variables | Severe sepsis patients (Group 1) (N = 30) |

Healthy volunteers (Group 2) (N = 40) |

ICU patients not in severe sepsis (Group 3) (N = 30) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

| CD62P% | 26.00 | 47.5 | 2.79 | 3.51 | 17.04 | 23.07 |

| CD62P MeFI | 30.00 | 11.0 | 23.65 | 7.37 | 26.76 | 13.38 |

| 62P MFI | 27.50 | 11.5 | 20.17 | 6.25 | 21.15 | 13.54 |

| 62P AIa | 853.50 | 1389.0 | 63.00 | 86.0 | 358.50 | 966.0 |

| CD154% | 00 | 00 | .05 | 0.11 | .00 | .06 |

| CD154 MeFI | 9.50 | 12.25 | 10.03 | 17.78 | 7.86 | 14.22 |

| CD154 MFI | 9.00 | 12.25 | 9.78 | 18.53 | 7.73 | 13.25 |

| PLA % | 12.00 | 11.25 | 9.08 | 3.87 | 9.00 | 6.82 |

| PLA MeFI | 111.50 | 46.25 | 74.28 | 24.11 | 114.63 | 47.71 |

| PLA MFI | 87.00 | 44.5 | 62.79 | 20.65 | 85.59 | 32.98 |

| PLA AIa | 1071.50 | 928.0 | 560.50 | 320.0 | 814.50 | 727.0 |

| MPA% | 2.00 | 1.2 | 1.58 | 1.05 | 2.04 | 2.14 |

| MPA MeFI | 122.00 | 63.75 | 134.47 | 61.17 | 118.19 | 105.77 |

| MPA MFI | 120.50 | 76.25 | 153.68 | 81.69 | 123.26 | 143.26 |

| CD11b % | 84.00 | 12.25 | 72.28 | 12.44 | 80.12 | 14.55 |

| CD11b MeFI | 526.00 | 479.0 | 405.70 | 150.88 | 505.13 | 344.26 |

| CD11b MFI | 523.00 | 579 | 417.92 | 159.5 | 580.47 | 367.97 |

CD: cluster designate; MeFI: mean fluorescence; MFI: median fluorescence; PLA: leucocyte–platelet adhesion; MPA: monocyte–platelet adhesion; IQR: interquartile range.

Index as a product of percent cells and median fluorescence.

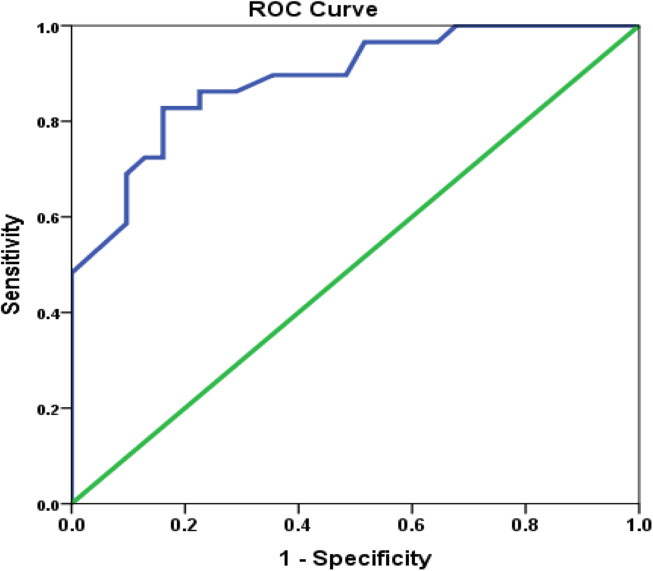

All the ICU patients were evaluated for SAPS 3 admission score. A Shapiro–Wilk's test (p > 0.05) and a visual inspection of the histograms, normal Q–Q plots and box plots of the SAPS 3 scores analysis for groups 1 and 3 showed that they were approximately normally distributed in both the groups with a skewness of 0.130 (Standard error (SE) 0.427) and a kurtosis of (−) 0.298 for Group 1 and a skewness of 0.697 (SE 0.427) and a kurtosis of (−) 0.604 for Group 3. In the ANOVA test, the SAPS 3 scores were significant in between the groups 1 and 3 (Fig. 1). Independent sample t test showed that in severe sepsis patients, there is a statistically significant higher SAPS 3 admission score seen among the non-survivors than survivors (p < 0.001). The SAPS 3 scores were also significantly different between the survivors and non-survivors in both the ICU patient groups (Table 4). In addition to SAPS 3 scores, both age and TLC were found to be significantly different between non-survivors and survivors. Interestingly, (though not statistically significant), all CD62P parameters were lower in non-survivors as compared to survivors. To determine the sensitivity and specificity and cut-off values for a given SAPS 3 score in determining the outcome, a ROC curve and area under ROC (AUROC) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was plotted (Fig. 2). There were 31 survivors and 29 non-survivors in the patient groups (group 1 and 3 combined). With a cut-off score of 55.5, SAPS 3 score predicted hospital mortality with a sensitivity of 82.8% and a specificity of 83.9%, with an AUROC of 0.888 (95% CI = 0.807–0.969, p < 0.000). A logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict survival for 60 ICU patients using SAPS 3 score as predictor. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to assess the agreement between the observed and expected numbers of survivors and non-survivors with regard to the probability of death. In this analysis, p > 0.05 was indicative good test adjustment. A test of the full model (predictability of 81.7%) against a constant only model (51.7%) was statistically significant, indicating that the predictor as a set reliably distinguished between survivors and non-survivors (chi square = 33.85, p < 0.000 with df = 1). A positive relationship between prediction and grouping was indicated by Nagelkerke's R2 of 0.575. Prediction success overall was 81.7% (79.3% for non-survivors and 83.1% for survivors.) The Wald criterion demonstrated that SAPS 3 score made a significant contribution to prediction (p = 0.000). EXP (B) value of 1.15 (95% CI = 1.075–1.224) which indicates that higher SAPS 3 score predicts increasing mortality. Addition of other variables such as CD62P score, PLA scores and CD11b did not improve the model fit.

Fig. 1.

Box plot of SAPS 3 admission scores among the patient groups. SAPS 3: Simplified Acute Physiology Score-3.

Table 4.

SAPS 3 admission score among non-survivors and survivors (groups 1 and 3).

| SAPS 3 admission score | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Severe sepsis patients (Group 1) (N = 30) |

ICU patients not in severe sepsis (Group 3) (N = 30) |

||||||

| Number | Mean | Median | IQR | Number | Mean | Median | IQR | |

| Died | 20 | 69.35 | 69 | 16 | 09 | 64.89 | 64 | 23 |

| Survived | 10 | 52.50 | 52 | 19 | 21 | 43.43 | 42 | 10 |

SAPS 3: Simplified Acute Physiology Score-3; IQR: interquartile range; ICU: intensive care unit.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve for SAPS 3 scores. SAPS 3: Simplified Acute Physiology Score-3; ROC: Receiver-operating characteristic.

PLA% score was significantly related to CD62P% value in Group 1 (coefficient of .424 and p=.019) but was weakly related in Group 3 (coefficient of .359 and p=.051). PLA% also showed a significant inverse correlation with SAPS 3 score in Group 3 (negative coefficient of –.435 and p=.016) but not in Group 1 (Fig. 3). There was no statistically significant correlation between SAPS 3 admission score and other parameters in the severe sepsis group.

Fig. 3.

Correlation/scatter graph between leucocyte–platelet aggregate (LPA) % and CD62P% in Group 1 and between LPA % and (Simplified Acute Physiology Score) SAPS 3 scores in Group 3. SAPS 3: Simplified Acute Physiology Score-3.

Discussion

In the present study, we used FCM to detect activation and functional status of circulating platelets and related the measured data with the calculated ICU prognostic scoring system in sepsis patients. We also measured, in healthy individuals, all the FCM test parameters evaluated in this study to form a baseline value for the Indian population after validation of the procedures. We also measured percentage positive cells, MeFI and MFI data for all the parameters.8, 9

As a measure of platelet activation, we determined the platelet surface expression of CD62P and CD154.10 In our study, CD 62 P expression in normal healthy individuals was 4.54% ± 4.18% (range: 1.07%–16.49%) and CD62P expression was found to be significantly increased in platelets in severe sepsis patients compared to healthy individuals. Other workers have reported a value for platelet CD62P, in a range of 8–21% in fresh samples and 1.9 ± 0.5% in the Indian population (Ray et al.).11, 12 Gawaz et al. have demonstrated increase in platelet CD62P expression with increased score of different ICU prognostic scoring systems (Elebute and Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) scores and a decline in 62 P expression on platelets in the setting of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) in severe sepsis.13 We have shown there is a mild negative trend between platelet 62P expression and SAPS 3 admission score in severe sepsis patients (not significant). We also noticed that CD62P scores were paradoxically lower in non-survivors compared to survivors. This can be explained by a probable exhaustion in platelet activation with increasing severity of sepsis. It was further seen than MFI is a better parameter than MeFI. Therefore, we have also included MFI as a measurement variable. In our study, we have proposed a new index “62 P AI” which is hoped to be more relevant.

Montalbano et al. found increased expression of platelet CD40 L (CD154) in sepsis with thrombocytopaenia.14 We have not found any significant difference in CD154 expression within the study groups. Moreover our sepsis group did not have significant thrombocytopaenia. These patterns of expression may be due to rapid proteolytic cleavage of CD154 within minutes.15

Leucocyte platelet adhesion (PLA) is the consequences of activated platelet surface expression of CD62P, fibrinogen and/or thrombospondin-mediated action.16 In the present study, we measured PLA percentage as well as MeFI and MFI. We also proposed for a new index “leucocyte–platelet adhesion index” which will be a better parameter than the individual variables. Li et al. showed PLA values 2.8 ± 0.7% (n = 12) in healthy control.17 In our study, the mean value of PLA% in normal individuals (n = 30) was 9.48 ± 3.12%. We have observed an enhanced platelet–leucocyte interaction (though statistically not significant) in severe sepsis patients when compared with healthy individuals. The only FCM parameters, which are statistically significantly correlated between the patient groups, were PLA% and 62P% in Group 1 and PLA% and SAPS 3 score in Group 3 (negatively correlated). The correlation between LPA% and activated platelets (62P %), which was significant in Group 1 but weaker in Group 3, may be due to early and sustained platelet activation in Group 1 (severe sepsis).The negative correlation of PLA% with SAP 3 score (in non-severe sepsis cases [Group 3]), may be a reflection that there may be other parameters than leucocyte–platelet aggregates that affect SAPS 3 scores. This will need further validation in larger studies. However, when analysing the data, we did not find statistically significant differences between survivors and non-survivors in PLA percentage.

In our study, platelet–monocyte aggregates (PMAs) were defined as monocytes (CD14-PE) positive for CD42a. Li et al., demonstrated PMAs in normal sample to be 2.4 ± 0.9.17 In our study observed level of platelet monocyte aggregates in normal healthy individuals was a mean of 1.84 ± 0.88. There was an enhancement seen in platelet-monocyte interaction in ICU patients when compared with healthy individuals. In our study we observed significantly higher CD11b expression and MFI were also higher than healthy individuals. Previous study in Indian population by Ray et al. showed CD11b expression in control group was 268 ± 42 (MeFI) for neutrophils and 353 ± 47 (MeFI) for monocytes.12, 13 In our study, average leucocyte CD11b MeFI in healthy control was 433 ± 151. TLC was positively correlated with CD11b% in severe sepsis group. We have not studied separately for leucocyte components. The above observed findings may be due to the complex interactions between various components.18, 19 As per recommendations of previous studies ACD as an anticoagulant is preferable for CD11b studies. Our results support use of ACD in evaluating CD11b expression.20, 21

In previous studies septic shock was associated with a significant drop in platelet count and an increase in TLC.19, 22 In this study we did not find statistically significant difference in platelet count but there is statistically significant differences found in TLC among the observed groups. Therefore our study results suggest that functional status of platelets and leucocytes in sepsis are more important than only absolute platelet count.

Furthermore, CD62P expression was positively correlated to PLA variables in severe sepsis patients which may indicate that activated CD62P positive platelets adhere more easily to leucocytes. These data may indicate that platelet CD62P expression is not only mechanism for platelets leucocytes adhesion, but also on other on the platelet surface adhesion molecules, e.g., the platelet fibrinogen receptor GPIIb/IIIa.15 The dependence of PLA on platelet 62 P expression than TLC may also indicate that platelets play more active role in the adhesion process.17

SAPS 3 score was the most robust of the parameters evaluated and acted as the best discriminant between the study groups. The scores were statistically different between group 1 and group 3. With a cut-of score of 55.5, SAPS 3 score predicted hospital mortality with a sensitivity of 82.8% and a specificity of 83.9%, with an AUROC of 0.888 (95% CI; 0.807–0.969, p < 0.000). Hernandez et al. in their study of 2426 ICU patients found the mean SAPS 3 score of 55 (16–124) with (AUROC = 0.80, 0.78–0.81).22 When sub group analysis was done the scores showed significant differences between survivors and non-survivors both in a combine analysis and in the severe sepsis group. (t test; p < 0.02). On logistic regression analysis of SAPS 3 score with mortality, the critical value is 56.78(SAPS 3 > -intercept/coefficient > −7.780/.137 > 56.78). Thus a patient with scores higher than 56.78, the logistic regression predicts that chances of mortality is more. However our sample sizes were small with multiple test parameters, with a higher chance of alpha error and lower power.

Conclusion

SAPS 3 admission scoring system used in this study have only platelet count, total and differential leucocyte count in the evaluated parameters none of which, except TLC (in early phase), is well correlated with severity of sepsis and dysfunction of leucocyte and platelet in sepsis. Therefore our pilot study was based on the idea that incorporation of platelet and leucocyte activation parameters, than mere static counts, will improve the existing prognostic model, but we were unable to conclusively prove it in this data set. Though not a primary objective, SAPS 3 cut-off scores generated gave us valuable data for the future studies of sepsis evaluation. Our data showed comparable results to many similar international studies for the parameters evaluated. In this study we established valid protocols, from sample collection to data interpretation, by extensive evaluation for platelet parameters, leucocyte-platelet interaction and leucocyte activation markers by FCM. However, in addition to sequential sampling and long term follow up, more number of cases with age and matched groups need to be evaluated in order to understand the complex interactions in the pathogenesis of sepsis, which will be imperative for developing targeted pharmacological interventions in the future.

Limitations

-

a)

Owing to operational difficulties to get voluntary healthy controls, our study population is not age matched.

-

b)

We worked with a basic four colour flow cytometer. Though robust, we feel that a modern multicolour FCM with higher sampling rate and better resolution will be better suited for platelet, leucocyte–platelet adhesion and microparticles analysis.

-

c)

In spite of best efforts, we had issues in evaluation of CD154 in control and patient samples. Hence the data cannot be used. More robust evaluation/validation is needed before commenting on the role of CD154 in sepsis.

-

d)

The sample numbers are small, but this was due to the strict criteria for case selection and criticality of patients in the ICU which resulted in a large percentage of cases being unsuitable to be included in the study, given the time frame of this study.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none declare.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on Armed Forces Medical Research Committee Project No. 4146/2011 granted and funded by the office of the Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services and Defence Research Development Organization, Government of India.

The authors would like to acknowledge help of Ms Sarika (Lab technician) in carrying out the sample preparation and testing.

References

- 1.Martin G.S. Sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock: changes in incidence, pathogens and outcomes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10(6):701–706. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy M.M., Fink M.P., Marshall J.C., Abraham E., Angus D., Cook D. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawaz M., Fateh-Moghadam S., Pilz G., Gurland H.J., Werdan K. Platelet activation and interaction with leucocytes in patients with sepsis or multiple organ failure. Eur J Clin Invest. 1995;25(11):843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1995.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coller B.S. Historical perspective and future directions in platelet research. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(suppl 1):374–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lundahl T., Fagerberg I., Egberg N., Bunescu A., Larsson A. Activated platelets and impaired platelet function in intensive care patients analyzed by flow cytometry. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1996;7(2):218–220. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199603000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreno R.P., Metnitz P.G., Almeida E., Jordan B., Bauer P., Campos R.A. SAPS 3–From evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 2: development of a prognostic model for hospital mortality at ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(10):1345–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michelson A.D., Barnard M.R., Krueger L.A., Valeri C.R., Furman M.I. Circulating monocyte-platelet aggregates are a more sensitive marker of in vivo platelet activation than platelet surface P-selectin studies in baboons, human coronary intervention, and human acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104(13):1533–1537. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.095588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnard M.R., Krueger L.A., Frelinger A., Furman M.I., Michelson A.D. Whole blood analysis of leukocyte – platelet aggregates. Curr Protoc Cytometry. 2003;6 doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0615s24. 15. 1-15.6.15. 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzenberg L.A., Tung J., Moore W.A., Parks D.R. Interpreting flow cytometry data: a guide for the perplexed. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(7):681–685. doi: 10.1038/ni0706-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamburger S.A., McEver R.P. GMP-140 mediates adhesion of stimulated platelets to neutrophils. Blood. 1990;75(3):550–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curvers J., de Wildt-Eggen J., Heeremans J., Scharenberg J., de Korte D., van der Meer P.F. Flow cytometric measurement of CD62P (P-selectin) expression on platelets: a multicenter optimization and standardization effort. Transfusion. 2008;48(7):1439–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray M.R., Roychoudhury S., Mukherjee S., Siddique S., Banerjee M., Akolkar A.B. Airway inflammation and upregulation of beta2 Mac-1 integrin expression on circulating leukocytes of female ragpickers in India. J Occup Health. 2009;51(3):232–238. doi: 10.1539/joh.l8116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gawaz M., Dickfeld T., Bogner C., Fateh-Moghadam S., Neumann F.J. Platelet function in septic multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23(4):379–385. doi: 10.1007/s001340050344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montalbano A., Turani F., Ciotti E., Fede M., Piperno M., David P. CD40L is selectively expressed on platelets from thrombocytopenic septic patients. Crit Care. 2010;14(suppl 1):P19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henn V., Slupsky J.R., Gräfe M., Anagnostopoulos I., Förster R., Müller-Berghaus G. CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature. 1998;391(6667):591–594. doi: 10.1038/35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redlich J.V., Losche W., Heptinstall S., Kehrel B., Spangenberg P. Formation of platelet-leukocyte conjugates in whole blood. Platelets. 1997;8(6):419–426. doi: 10.1080/09537109777113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li N., Goodall A.H., Hjemdahl P. Efficient flow cytometric assay for platelet-leukocyte aggregates in whole blood using fluorescence signal triggering. Cytometry. 1999;35(2):154–161. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990201)35:2<154::aid-cyto7>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russwurm S., Vickers J., Meier-Hellmann A., Spangenberg P., Bredle D., Reinhart K. Platelet and leukocyte activation correlate with the severity of septic organ dysfunction. Shock. 2002;17(4):263–268. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japp A.G., Chelliah R., Tattersall L., Lang N.N., Meng X., Weisel K. Effect of PSI-697, a novel P-selectin inhibitor, on platelet-monocyte aggregate formation in humans. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(1) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.006007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Repo H., Jansson S.-E., Leirisalo-Repo M. Anticoagulant selection influences flow cytometric determination of CD11b upregulation in vivo and ex vivo. J Immunol Meth. 1995;185(1):65–79. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00105-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dellinger R.P., Levy M.M., Rhodes A., Annane D., Gerlach H., Opal S.M. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(2):165–228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez, Palo Performance of the SAPS 3 admission score as a predictor of ICU mortality in a Philippine private tertiary medical center intensive care unit. J Intensive Care. 2014;2:29. doi: 10.1186/2052-0492-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]