Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a continuum with neuropathologies manifesting years before clinical symptoms; thus, AD research is attempting to identify more disease-modifying approaches to test treatments administered before full disease expression. Designing such trials in cognitively normal elderly individuals poses unique challenges.

Methods

The TOMMORROW study was a phase 3 double-blind, parallel-group study designed to support qualification of a novel genetic biomarker risk assignment algorithm (BRAA) and to assess efficacy and safety of low-dose pioglitazone to delay onset of mild cognitive impairment due to AD. Eligible participants were stratified based on the BRAA (using TOMM40 rs 10524523 genotype, Apolipoprotein E genotype, and age), with high-risk individuals receiving low-dose pioglitazone or placebo and low-risk individuals receiving placebo. The primary endpoint was time to the event of mild cognitive impairment due to AD. The primary objectives were to compare the primary endpoint between high- and low-risk placebo groups (for BRAA qualification) and between high-risk pioglitazone and high-risk placebo groups (for pioglitazone efficacy). Approximately 300 individuals were also asked to participate in a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging substudy at selected sites.

Results

The focus of this paper is on the design of the study; study results will be presented in a separate paper.

Discussion

The design of the TOMMORROW study addressed many key challenges to conducting a dual-objective phase 3 pivotal AD clinical trial in presymptomatic individuals. Experiences from planning and executing the TOMMORROW study may benefit future AD prevention/delay-of-onset trials.

Keywords: Clinical trial design, Delay of onset, Genetic risk for AD, Mild cognitive impairment due to AD, Time to event, Trial population enrichment

Highlights

-

•

Applied a genetics-based algorithm to enrich for near-term risk of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease.

-

•

Assessed early cognitive decline with a multidomain neuropsychological test battery.

-

•

Utilized time to mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease as study endpoint.

-

•

Simultaneous evaluation of a biomarker and therapeutic.

1. Background

Delay-of-onset/prevention trials for Alzheimer's disease (AD) represent a paradigm shift from what had become standard practice for testing potential AD drug therapies. Historically, the template for successful AD clinical drug trials was set by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the late 1990s. As a result, most subsequent late-stage AD clinical trials, regardless of therapeutic mechanism, targeted patients with mild-to-moderate or moderate-to-severe AD [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]], were conducted for up to 6 months and used coprimary endpoints covering cognition and function [11,12]. AD was still thought of as a condition with distinct clinical phases, and most therapeutic approaches aimed, and failed, to treat existing symptoms and improve on (as monotherapy) or supplement (as adjunctive therapy) the limited benefits of approved therapies. These disappointing results set the stage for earlier intervention, towards a more preventive, delay-of-onset paradigm.

Prevention studies for AD test disease modification by recruiting and studying cognitively normal elderly individuals and tracking their conversion to a recognized cognitive disease state. The needs of such studies present unique challenges that must be considered in the design of the clinical trial. Owing to the low incidence rate of AD in the general population [13], it is necessary to enrich a cognitively normal trial population for participants with increased risk of cognitive impairment onset during the timeframe of a prevention-type clinical trial (minimum 4–5 years) [[14], [15], [16]], to avoid prohibitive trial size and duration. Enrichment strategies for a study in presymptomatic individuals would typically make use of any number of key risk factors, such as advanced age, neuropathology burden, or family history of AD. In addition, determining transition from normal cognition to early clinical disease states in aging populations is challenging given the inherent variability in neurocognitive performance over repeated testing sessions, practice effects, and the influences of common comorbidities on cognition. A clinical trial aiming to intervene before the mild AD stage therefore requires the use of innovative, sensitive neuropsychological measures designed to detect the earliest signs of disease and to track cognitive decline.

The TOMMORROW study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01931566)—a phase 3, multicenter, global, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial conducted by Takeda Pharmaceuticals (Deerfield, IL) in partnership with Zinfandel Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Chapel Hill, NC)—was faced with navigating the challenges of an interventional trial to delay the onset of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD. The study was designed to address two primary objectives independently yet simultaneously: (1) to qualify a biomarker risk assignment algorithm (BRAA) composed of the translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane 40 homolog rs 10524523 (TOMM40 '523) genotype, apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype, and current age for assigning the risk of developing MCI due to AD and (2) to evaluate the efficacy of an interventional compound, pioglitazone (AD4833 0.8 mg sustained release once daily) in delaying the onset of MCI due to AD in cognitively normal individuals who are at risk of developing disease symptoms within the next 5 years. The urgent societal need for an impactful therapeutic option in AD [17,18] motivated a TOMMORROW study design that aimed to pursue genetic biomarker risk algorithm qualification and pioglitazone efficacy efforts within the same study, instead of conducting each study sequentially.

The TOMMORROW study was conducted between 2013 and 2018. The study was terminated before its planned completion based on data from a prespecified efficacy futility analysis (see Supplementary Material). Results from the study will be the subject of separate manuscripts. The goals of this paper are to share the TOMMORROW study design experience, discuss the rationale for choices made, and facilitate the design and conduct of future similar clinical trials.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design overview

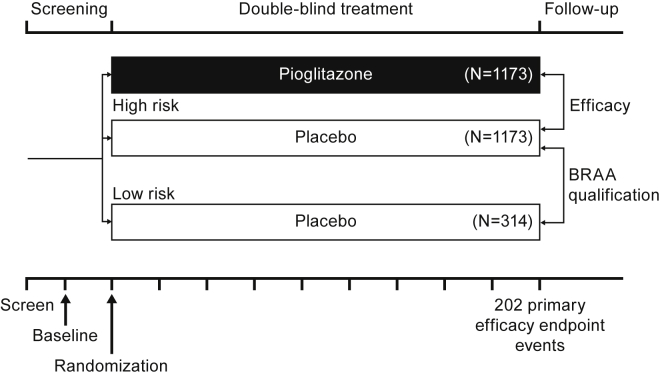

While addressing the specific challenges posed by a delay/prevention study in AD, as described previously, the design of the TOMMORROW study posited that the BRAA would effectively distinguish between cognitively normal elderly people at “high risk” and those at “low risk” of developing MCI due to AD within a 5-year timeframe. The study was designed so that the study investigators remained blinded to the results of the prognostic test and assigned treatment, and that central randomization could be used to maintain this blind. The general design is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

TOMMORROW study design framework. (Note: The numbers of participants in each arm of the diagram reflect calculated participants needed for the prespecified statistical power, not the number actually enrolled in the study. After a reassessment by the sponsor in 2015, the drug effect size assumption was increased from 30% to 40%. This change resulted in a decrease in the number of required study participants to achieve study goals from the initial target of approximately 5800 to 2800 and reduced the number of efficacy endpoint events from 410 to 202.). Abbreviation: BRAA, biomarker risk assignment algorithm.

In this design, only the “high-risk” group was evenly randomized to receive pioglitazone treatment or placebo; a smaller number of “low-risk” individuals were assigned to placebo only. This design allows two hypotheses to be investigated simultaneously: the first relates to the ability of the risk algorithm to define the “high-" and “low-risk” groups by comparing the data from the placebo-treated participants; the second relates to whether the treatment can delay the time to MCI due to AD onset by comparing the data from the treatment and placebo groups of the “high-risk” arm.

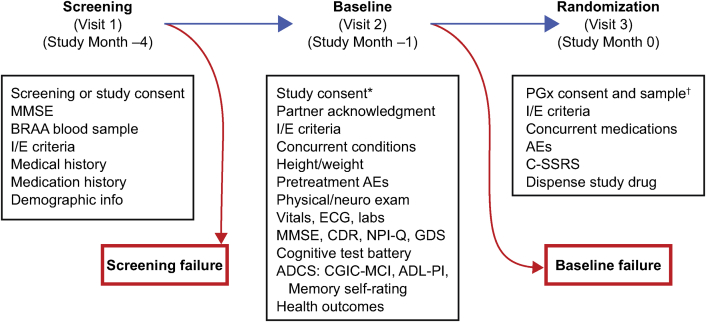

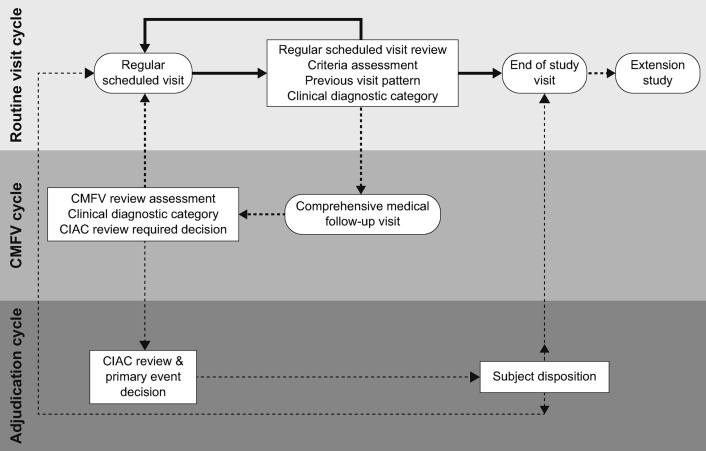

The study's enrollment procedure included separate screening, baseline, and randomization visits (for details, see selection of study participants section of the Supplementary Material). A rolling process was implemented in which low-risk participants were randomized throughout the enrollment period in a manner that ensured representation from all sites. Participants' risk status and treatment assignment remained blinded throughout the course of the study. Participants also were required to have a project partner who was able to provide information on the cognitive, functional, and behavioral status of the individual. The study operationalized MCI due to AD core clinical criteria [19] to guide its diagnosis as the primary endpoint event for both objectives. The study duration was event-driven, that is, the time needed to accumulate 202 conversions from normal cognition to an adjudicated diagnosis of MCI due to AD in the non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasian participants (see below) within the high-risk stratum, anticipated to be a minimum of 4 years. However, because the biomarker risk stratum information was blinded, accumulation of the target event total was estimated using all subjects (both high-risk and low-risk) in the non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasian group. This would occur when approximately 215 events have been confirmed through adjudication in the non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasian group (including both high-risk and low-risk subjects). Primary endpoint events were determined by an independent Cognitive Impairment Adjudication Committee. Further information regarding the adjudication process can be found in the Supplementary Material.

The trial enrolled all ethnicities using the BRAA to assign risk. However, the primary analyses to evaluate the effects of pioglitazone versus placebo were intended to be within the non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasian high-risk subgroup. The genetic analyses that led to the development of the BRAA were performed in non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasians because it was known that there are specific APOE-TOMM40 '523 haplotypes observed in African and African American populations that are not observed in non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasians [20,21]. Moreover, Asians have different allele frequencies of the TOMM40 '523 gene than non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasians [22]. Therefore, expansion of use of the BRAA for risk prediction for other ethnicities will require additional calibration and testing.

2.2. Ethics and safety aspects

The TOMMORROW trial was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the clinical study protocol, in compliance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and the ICH Guidelines for GCP, and approval by corresponding regulatory authorities, and the appropriate institutional review boards and independent ethics committees. Participants gave their written informed consent before screening in the study. In addition to regular safety surveillance, the safety of participants was evaluated by an independent Data Safety Monitoring Board. The Data Safety Monitoring Board met periodically to review aggregate and individual participant data related to safety, data integrity, and overall conduct of the trial. Unblinded adverse events listing and summary tabulations (including adverse events of special interest), serious adverse events, markedly abnormal laboratory parameters, protocol deviations listing, and enrollment summary were reviewed during these meetings. This group included individuals with expertise in endocrinology, neuroradiology, AD, cardiology, and statistics.

2.3. Study enrichment

Genetics and age have long been recognized as important risk factors for AD. The well-established genetic risk factor APOE ε4 is informative for approximately 25% of the Caucasian population who carry one or two APOE ε4 alleles. In 2009, a team of scientists led by Allen Roses identified a genetic variant—TOMM40 '523—that, when combined with the APOE genotype and age, predicted cognitive decline onset [23] and provided a means to assess risk in the non-APOE ε4 carrier Caucasian population.

A genetic-based BRAA, implemented via a simple blood test, was developed as a “fit for purpose” enrichment tool for the trial. The BRAA was used to enrich the TOMMORROW trial with individuals at an elevated near-term (i.e., 5-year) risk for onset of cognitive decline to evaluate efficacy of a therapeutic; details of the development of the BRAA are provided in the study by Crenshaw et al. [24], and detailed performance characteristics of the BRAA are described in Lutz et al. [25]. In brief, the algorithm incorporates an individual's current age along with TOMM40 '523 and APOE genotypes to determine the likelihood of developing MCI due to AD in a 5-year timeframe, corresponding to the anticipated duration of the TOMMORROW trial. The combination of APOE genotype, TOMM40 '523 genotype, and age at screening classifies individuals as high-risk or low-risk in accordance with decision rules, some of which are age-independent, whereas others change risk classification at specific ages. The age thresholds for risk are identified using historical data [24,25]. The addition of TOMM40 '523 to the algorithm was included to provide higher resolution than APOE genotype alone in risk assessment for APOE ε3/ε3 and APOE ε3/ε4 individuals. As testing the BRAA was a co-primary objective of TOMMORROW, if the study data support the BRAA as a successful prognostic tool, it could then potentially be qualified for use in clinical development (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm230597.pdf). If the study data also support efficacy of the therapeutic, then the BRAA could be used as a companion diagnostic for drug administration.

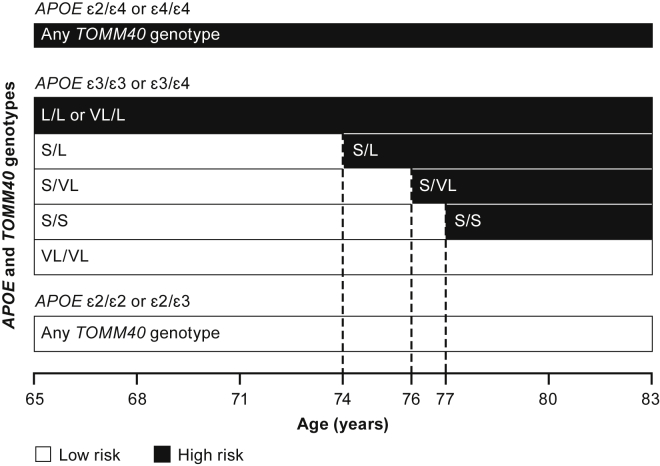

Fig. 2 summarizes the risk stratification scheme for the BRAA, which was finalized following discussions with regulators. The low-risk stratum includes carriers of APOE ε2/ε2 and APOE ε2/ε3 genotypes, and a proportion of APOE ε3/ε3 participants. Those with TOMM40 '523 L/L (i.e., ε4/ε4 carriers) or VL/L are classified as high risk. Three TOMM40 '523 genotypes are associated with APOE ε3/ε3 and ε3/ε4, conferring a risk status that changes as a function of age: TOMM40 '523 S/L becomes high risk at age 74 years; TOMM40 '523 S/S individuals enter the high-risk category at age 77 years; and TOMM40 '523 S/VL becomes high risk at age 76 years. APOE ε2/ε4 individuals are included in the high-risk stratum as a consequence of carrying an APOE ε4 haplotype (note that <3% of Caucasians possess this genotype). TOMM40 '523 VL/VL participants are classified as low risk for the age range included in the trial.

Fig. 2.

Biomarker risk assignment algorithm. Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; TOMM40, translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane 40.

2.4. Treatment and dose rationale

The rationale for the choice of therapeutic to test in TOMMORROW was based on recent research in AD. Since the discovery of APOE as the principal genetic risk factor for late-onset AD 25 years ago, the molecular pathology that leads to late-onset AD remains unknown. In addition to the hypothesis that the disease is the result of the aggregation of plaques and tangles in the brain, several molecular pathways have been implicated in the onset or progression of AD, including neuroinflammation [26], perturbations of lipid homeostasis and glucose metabolism [[27], [28], [29]], and impaired mitochondrial function [30,31]. Research has established interactions between these molecular pathways and Aβ accumulation [[32], [33], [34], [35]]. In addition, the choice of therapeutic intervention in presymptomatic AD individuals should ideally have a well-established tolerability profile to ensure the appropriate benefit-risk for study participants with long-term chronic administration.

Pioglitazone, a potent highly selective agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, increases mitochondrial numbers, motility, and function at very low doses (relative to doses used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus) [36]. This effect on mitochondria is hypothesized to be a key mechanism of action for pioglitazone's potential ability to delay the onset of MCI due to AD. In addition to these preclinical studies, an imaging study (using functional magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) conducted in cognitively normal elderly individuals demonstrated that pioglitazone has central nervous system effects at low doses and there is a demonstrable blood oxygen level–dependent effect in the left hippocampus during an encoding task for episodic memory [37]. An important consideration in dose selection was to identify the lowest effective dose to optimize the benefit-risk ratio by minimizing potential adverse events (e.g., edema) while ensuring that pioglitazone can still directly influence brain activity in cognitively normal elderly adults, the intended TOMMORROW study population. Based on the available literature and the results of the blood oxygen level–dependent functional MRI study, pioglitazone sustained release 0.8 mg, administered once-daily, was selected for TOMMORROW.

2.5. Clinical assessment tool and operationalizing MCI due to AD criteria

In discussions with the regulatory authorities, it was clear that the endpoint for this delay-of-onset study would ideally be a clinical diagnosis of an identifiable, intermediate state of presymptomatic AD. A small team of neuropsychology experts (Duke University) provided leadership in the design and conduct of neuropsychological assessment, the core element of the study. Working with experts in AD clinical trials, neuropsychology, cross-cultural measurement, and biostatistics, a neuropsychological battery was developed to identify individuals exhibiting the early stages of impairment. Individually, the instruments in the battery were all measures used in clinical neuropsychological practice that were appropriate for the preclinical stage of disease with known psychometric and normative data to facilitate diagnostic inferences in English-speaking populations. The measures tapped five broad domains affected in age-associated cognitive disorders and AD (Table 1) and also included tests in the memory and executive function domains shown previously to respond to the class of agent [38]. Normative and validation studies were conducted on the battery to ensure consistent performance across the multiple languages spoken and cultures experienced by study participants [39] (see Supplementary Material).

Table 1.

TOMMORROW neuropsychological battery

| Cognitive domain | Tests |

|---|---|

| Attention | Wechsler adult intelligence scale (WAIS)-III digit span test–forward span Trail making test (TMT) (Part A) |

| Episodic memory | California verbal learning test–2nd edition (CVLT-II) Brief visuospatial memory test–revised (BVMT-R) |

| Executive function | TMT (Part B) WAIS-III digit span test–backward span |

| Language | Multilingual naming test (MiNT) Semantic fluency (animals) Lexical/phonemic fluency (F, A, and S) |

| Visuospatial | Clock-drawing test Copy of BVMT figures |

Normative data available per language; see Cultural validation of the TOMMORROW neuropsychological battery in Supplementary Material.

To operationalize the criteria for the clinical trial, measures were selected that addressed the published criteria and were based on current standards of research and clinical practice for the detection of incident MCI due to AD [19]. The neuropsychological battery had at least two measures for each of the five cognitive domains to ensure consistency in drawing inferences of impairment in any domain, as well as to guard against spurious findings and potential missing data that can occur in a repeated measures design. The domains and measures selected are summarized in Table 1 and the full operationalization of the criteria for a diagnosis of MCI due to AD is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operationalized criteria for MCI due to AD

| Core clinical criteria (NIA–Alz Association; Albert et al. [19], 2011) | Core clinical criteria (operationalized) |

|---|---|

|

|

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Regarding the operationalized criteria, it is important to note that (1) given the inherent variability in cognition early in the expression of AD, a reliable diagnostic endpoint of MCI due to AD was defined as a stable diagnosis fulfilled across two consecutive examinations, 6 months apart and (2) these operationalized criteria were intended as guidance for diagnostic and endpoint consistency, but not as an algorithmic checklist. With the aid of these criteria, site investigators made clinical diagnoses based on the totality of the participant's data and in collaboration with the site neuropsychologist. When appropriate as per the protocol, cases were forwarded for adjudication, and determination of whether they met criteria for the MCI due to AD was made by the Cognitive Impairment Adjudication Committee (see Supplementary Material).

2.6. Imaging substudy

The TOMMORROW study design planned to include approximately 300 cognitively normal elderly individuals in a concurrent imaging substudy at selected sites. Participants were enrolled in the main TOMMORROW protocol and were required to sign a separate informed consent form to participate in this substudy. Eligible individuals who volunteered to participate in the substudy were selected in a double-blind fashion to represent a 5:4 randomization ratio between pioglitazone and placebo assignment. Participants in this substudy were scanned using MRI to assess changes in brain volume among the treatment groups (i.e., pioglitazone, high- or low-risk placebo). Serial brain MRI scans were performed at baseline, 2 years, and the end-of-study/early-withdrawal visit (minimum of two, maximum of three time points in total). Details regarding this imaging substudy are provided in the Supplementary Material.

2.7. Statistical analysis plan

The TOMMORROW study's design resulted in the following primary analysis in the Statistical Analysis Plan. Details regarding sample size calculations and secondary and prespecified futility analyses are described in the statistical considerations section of the Supplementary Material.

2.7.1. Primary biomarker risk assignment algorithm analysis

The primary analysis for assessment of the BRAA performance to assign risk of conversion as high or low during the trial was based on a Cox proportional hazards (CPH) survival model. The event for this analysis was an adjudicated event of MCI due to AD. For the primary BRAA performance analysis, participants were limited to those of non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasian ethnicity to correspond to the cohorts that were originally used to develop the BRAA. The two trial arms to be compared were the placebo-treated low-risk group and the placebo-treated high-risk group. Gender, education, and center, where assessed, were included as covariates. Point estimates, 2-sided 99% confidence intervals, and appropriate P values for the hazard ratios obtained from the CPH model were computed to test the null hypothesis of equality of the hazard functions between high-risk placebo and low-risk placebo.

2.7.2. Primary efficacy analysis

A similar analysis process as described previously for the primary BRAA analysis was used to compare the placebo- and active-treated non-Hispanic/Latino Caucasian participants (see study design overview Section 2.1) within the high-risk group (i.e., using a similar CPH model with covariates of gender, education, and center and an additional covariate of age but using a factor of high-risk treatment group instead of BRAA risk assignment). Point estimates, 2-sided 99% confidence intervals, and appropriate P values for the hazard ratios obtained from the CPH model were computed to test the null hypothesis of equality of the hazard functions between the high-risk pioglitazone and high-risk placebo treatment groups. For registration purposes, this study was envisioned as a single, pivotal, registration study; therefore, a more stringent alpha level of 0.01 was prespecified. Further descriptions of statistical analyses applied to TOMMORROW data are included in the Supplementary Material.

2.8. Extension study

Patients who completed the pivotal TOMMORROW study with an adjudicated diagnosis of MCI due to AD were offered the opportunity to continue treatment and medical management in a blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter, parallel-group long-term extension study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02284906) designed to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of pioglitazone on cognitive function. Individuals were eligible to participate in this extension study based on inclusion/exclusion criteria and on whether their site chose to participate. The treatment assignment from the pivotal study remained unchanged in the extension, that is, participants continued to receive the same study medication they received during the TOMMORROW study, either pioglitazone or placebo. The extension study was designed to follow individuals from the time they completed the TOMMORROW study until 2 years after TOMMORROW reached its target number of primary endpoint events and concluded, allowing everyone enrolling into the extension study a minimum potential follow-up period of 2 years. Of the 202 potential participants from both the high- and low-risk arms of TOMMORROW, it was expected that approximately 149 would eventually enroll into this extension study; however, because TOMMORROW was terminated early for efficacy futility, total enrollment in the extension study only reached 40. As with TOMMORROW, results from the extension study will be described in a separate paper.

3. Discussion

During the study planning stages (2009–2013)—well before the current (February 2018) FDA guidance for developing drugs in early AD—it became clear that many aspects of the proposed study had no formal precedent in the AD clinical research arena, especially for a single phase 3 study intended to qualify a biomarker and register a therapeutic. Therefore, dialog with regulatory authorities and experienced AD clinical trialists was solicited early and on an ongoing basis before study start to best incorporate the innovative aspects of study design (e.g., cognitively normal population, genetic-based enrichment, choice of therapeutic, choice of time-to-event outcome measure). Throughout the early stages of the study design process and before study start, comments were provided from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) regarding the TOMMORROW program. Chronologically, these regulatory interactions included FDA Voluntary Exploratory Data Submission meeting (2009); FDA Pre-IND meeting (2011); FDA end-pf-phase 2 meeting (2012); EMA Scientific Advice/Qualification Advice (2012); FDA Pre-IDE application meeting (2013). In addition to the dialog with regulatory authorities, the team also sought guidance from medical experts individually and via advisory panels to solicit their strategic input to the TOMMORROW program early in the process, and their feedback was incorporated into the design.

In these discussions, regulators and consultant experts emphasized that the endpoint for this delay-of-onset study would ideally be a clinically defined endpoint, such as the diagnosis of an identifiable, intermediate state of AD. Because of the inherent variability in the diagnosis of AD, particularly in the early stages of disease expression, use of a diagnostic endpoint at the intermediate stage of the disease required the application of appropriate diagnostic procedures and robust neuropsychological measures for reliable detection of early-stage cognitive decline. At the time when the TOMMORROW study was being planned, the secondary prevention trials in AD had not yet begun, and the utility of the in vivo AD neuropathological biomarkers as endpoints was not yet established. There was, however, broad agreement that sensitive cognitive measures had the greatest potential utility for observing subtle clinical change in presymptomatic AD [40]. Finally, the path forward for the evaluation of a potential prognostic and therapeutic agent within the same design was untested from a regulatory perspective. In 2011, a workgroup of the National Institute of Aging and Alzheimer's Association redefined AD as a disease continuum [19,41,42]. One of these papers, in 2011 by Albert et al., “The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease,” described core clinical research criteria to identify individuals exhibiting the earliest evidence of cognitive decline, MCI due to AD [19], providing a potential endpoint for trials looking to therapeutically intervene in cognitively normal individuals. These were matched to measurable assessment thresholds in the TOMMORROW study to define the primary endpoint event, making adjudicated clinical judgment the benchmark for determining the earliest point of transition to impaired cognitive status.

As AD clinical research continues to explore intervention earlier in the cognitive decline continuum, the challenge, particularly for delay-of-onset studies, is for these endpoints to be robust, reliable, and clinically meaningful in the general practice of medicine. For the TOMMORROW study, the therapeutic hypothesis was that treatment of cognitively normal at-risk individuals with low-dose pioglitazone would preserve cognitive functioning and positively shift the slope of cognitive decline. Therefore, looking at the time to event in the placebo versus treatment arm was chosen as a clinically relevant endpoint. This “prevention” approach is analogous to that used in cardiovascular disease that has proven effective in reducing mortality [43,44]. The TOMMORROW study used the just-established clinical diagnosis, MCI due to AD, as its primary endpoint event, and required independent adjudication for its determination. It relied on careful assessment of early cognitive change and the totality of data from the participant as well as the project partner based on the most current MCI definitions at the time of study design [19]. The benefit of selecting this diagnosis as the endpoint event was that if the trial was successful, it would provide evidence of a clinically meaningful outcome. This was important conceptually as it obviated the need for a functional co-primary for a condition defined as having evidence of cognitive decline without a discernible functional impairment.

Incident MCI due to AD is a diagnosis that rests on identifying suspect day-to-day changes in memory that are not easy to determine without the aid of collateral informants. From a practical perspective, having a project partner provided an ongoing reliable assessment of the participant's functioning and cognitive status and was beneficial for the participant's emotional support, motivation, and assistance with visit organization and medication compliance over the course of the lengthy trial. However, the requirement for and maintenance of a consistent project partner during the full trial duration presented significant recruitment and retention challenges and necessitated accommodations to account for a project partner's life and schedule, such as phone reporting or home visits in exceptional circumstances. Not unexpectedly, a number of couples joined the study with each individual acting as both a participant and a project partner.

A large, long-duration delay-of-onset study requires procedural flexibility to improve recruitment and support retention of both participants and project partners. Potential TOMMORROW participants were initially screened with minimal in-clinic assessment, primarily for cognitive status eligibility using the Mini–Mental State Examination and, if normal, with blood sample collection for genetic testing and risk assignment using the BRAA. The study design reflected an approximately 8:1 high-risk to low-risk numerical imbalance and used a rolling enrollment strategy across sites and regions to achieve a balanced study representation. In addition, a significant cohort of screened individuals were anticipated to be within the lower age range (65–70 years of age; 47%), which has the lowest risk for onset of MCI due to AD. Consequently, customized recruitment strategies and tool kits to efficiently increase yield in the high-risk stratum at sites were supported, specifically the development of local trial registries, and community engagement and educational seminars. A screening-only informed consent was also employed as additional efficiencies were explored to reduce site and participant burden during the screening process. Once enrolled, it is critical to the success of this type of study to retain both the participant and project partner through study completion. Furthermore, it should be noted the retention challenge (and associated potential impact to trial performance) for delay/prevention trials in elderly individuals involving a long follow-up period becomes a larger issue as the population ages. This dropout risk can reduce the number of events and threaten the success of the trial. Retention practices that foster the clinical site's relationships with the participants are key for mitigating early terminations. Follow-up procedures that are flexible to accommodate the participants' changing circumstances, such as remote assessment, can also guard against missing data.

Large phase 3 studies such as TOMMORROW, which seek to delay the onset of clinical disease symptoms in asymptomatic individuals, face a number of challenges regarding selection of study participants. Foremost among these is the ability to select those most likely to experience clinical disease symptoms within the expected timeframe of the study, to best enable differentiation between a placebo and active drug effect. Therefore, prognostic enrichment of the TOMMORROW study population was integral to the study design, to identify those at elevated near-term risk to develop MCI due to AD. Genetic testing is commonly used in medical practice around the world, uses a readily available tissue (blood draw or buccal sample), and does not require specialized facilities or reagents. Use of the BRAA provided the necessary enrichment of at-risk, presymptomatic individuals to support an interventional delay-of-onset trial.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in the TOMMORROW study design. The first is the evaluation of a single dose of the therapeutic. Multiple dosing arms were considered during the design phase of the study to delineate potential dose-response effects but were not implemented due to time, cost, and logistic considerations. Another limitation is the feasibility of conducting a confirmatory second trial. Owing to the long duration and large international sample size planned, conduct of a parallel study simultaneously with TOMMORROW was considered logistically and cost-prohibitive. With prior input from the EMA and US FDA, the TOMMORROW study therefore represents a single phase 3 registration study, which alone could provide evidence to support qualification of the BRAA and evidence of safety and efficacy for pioglitazone as a therapeutic to delay the onset of MCI due to AD.

Another limitation of this study is the inability to provide longitudinal information regarding amyloid or tau protein burden in asymptomatic individuals at high and low risk for MCI due to AD because neuropathology biomarkers were not collected, other than volumetric MRI (in a subset of participants). At the time this study was initiated, imaging markers and cerebrospinal fluid measurements of amyloid and tau were in development, but none had been sufficiently qualified and validated [45,46]. The reagents were not widely available (particularly where many of the clinical sites were located), the methods and analyses were not standardized, and there was concern about overburdening the TOMMORROW protocol, sites, and participants with experimental procedures. Furthermore, as the study was designed with a clinical diagnosis and was reliant on cognitive change, success was not dependent on documenting a change to the amyloid or tau levels. After the study was in the treatment phase, several strategies were considered to integrate neuropathology biomarkers into the study. However, these were not implemented as no baseline measures for these markers had been collected and because doing so would lead to significant increase in cost, complexity, site, and participant burden and would not have provided data supporting product approval.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: The authors reviewed literature from traditional sources (e.g., PubMed), meeting abstracts, presentations, and engaged experienced Alzheimer's disease (AD) clinical trialists. Priority was given to delay-of-disease-onset clinical trials and time-to-event precedents, along with significant scientific and regulatory developments in the AD field that shaped the landscape before the TOMMORROW study was launched. Relevant examples are appropriately cited.

-

2.

Interpretation: Design of the TOMMORROW study demonstrated that a novel clinical trial approach incorporating a genetic-based enrichment strategy, a pleiotropic therapeutic agent, and cognition-driven primary endpoints could be used in a phase 3 pivotal study of cognitively normal, healthy, at-risk elderly participants.

-

3.

Future directions: There is increasing interest in intervening in cognitive decline in presymptomatic individuals. The manuscript provides insights into the challenges presented by studying cognitively healthy elderly adults and will enable future clinical studies in presymptomatic AD to learn from the unique design elements used by TOMMORROW.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the members of the TOMMORROW Protocol Advisory Board (Drs. Bruno Dubois, Jeffrey Cummings, Rachelle Doody, Constantine Lyketsos, Eric Reiman, and Kathleen A. Welsh-Bohmer), the Neuropsychology Advisory Board (Drs. Kathleen A. Welsh-Bohmer (Chair), Mary Sano, Lon Schneider, Suzanne Craft, Mark Espeland, and Andreas Monsch) for their efforts and commitment on behalf of the study. The authors also acknowledge and thank Dr. Brenda Plassman, Dr. Kathleen Hayden, Dr. Heather Romero, and Dr. Kathleen Welsh-Bohmer of Duke University who collectively formed the Neuropsychology Lead Office, which provided leadership on design and conduct of neuropsychology aspects of the study. The authors also acknowledge and thank Dr. James Burke, Dr. Kumar Budur, Ryan Walter, Dom Fitzsimmons, LaDonna Randle, Daniel Hilby, Dr. Donna Crenshaw, Julian Arbuckle, Shyama Brewster, Tom Swanson, and Dr. Yuka Maruyama for their important contributions to the design and conduct of the TOMMORROW study.

Finally, the authors also gratefully recognize the leadership role of Dr. Allen D. Roses in the design of the TOMMORROW study. The concept of simultaneously testing a biomarker to identify those at near-term risk for developing the onset of Alzheimer's disease along with a therapeutic to delay that onset was conceived and put into effect by Dr. Roses. His dedication to alleviating the burden of AD culminated in the design and execution of the TOMMORROW study. Unfortunately, Dr. Roses passed away before study termination.

Editorial support was provided by Chameleon Communications International Ltd, UK (a Healthcare Consultancy Group company) and sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd.

This work was sponsored by Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA, and Zinfandel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Durham, NC, USA. The sponsors designed the study, wrote this report, and were involved in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

D.K.B., C.C., S.H., D. Yarnall, C.M., S.S., and A.M.S. are employees of Zinfandel Pharmaceuticals. K.A.W.B. and B.L.P. received funding from Takeda as part of a contract with Duke University for the work she and her team conducted as the neuropsychology leads to the TOMMORROW program. S.K.B., J.O’N., G.R., P.H., and E.L. were employed by Takeda at the time of the study. M.C., D. Yarbrough, and S.P. are employees of Takeda. M.L. is an employee of Duke University and a consultant to Zinfandel Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.010.

Contributor Information

Daniel K. Burns, Email: dburns@zinfandelpharma.com.

TOMMORROW Study Investigators:

Bruno Dubois, Jeffrey Cummings, Rachelle Doody, Constantine Lyketsos, Eric Reiman, Kathleen A. Welsh-Bohmer, Kathleen A. Welsh-Bohmer, Mary Sano, Lon Schneider, Suzanne Craft, Mark Espeland, and Andreas Monsch

Supplementary data

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Supplementary Fig. 2.

References

- 1.Quinn J.F., Raman R., Thomas R.G., Yurko-Mauro K., Nelson E.B., Van Dyck C. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1903–1911. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohs R.C., Shiovitz T.M., Tariot P.N., Porsteinsson A.P., Baker K.D., Feldman P.D. Atomoxetine augmentation of cholinesterase inhibitor therapy in patients with Alzheimer disease: 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-trial study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:752–759. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181aad585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salloway S., Sperling R., Gilman S., Fox N.C., Blennow K., Raskind M. A phase 2 multiple ascending dose trial of bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:2061–2070. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freund-Levi Y., Hjorth E., Lindberg C., Cederholm T., Faxen-Irving G., Vedin I. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on inflammatory markers in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma in Alzheimer's disease: the OmegAD study. Demen Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27:481–490. doi: 10.1159/000218081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salloway S., Sperling R., Keren R., Porsteinsson A.P., van Dyck C.H., Tariot P.N. A phase 2 randomized trial of ELND005, scyllo-inositol, in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:1253–1262. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182309fa5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sano M., Bell K.L., Galasko D., Galvin J.E., Thomas R.G., van Dyck C.H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of simvastatin to treat Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:556–563. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318228bf11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrington C., Sawchak S., Chiang C., Davies J., Donovan C., Saunders A.M. Rosiglitazone does not improve cognition or global function when used as adjunctive therapy to AChE inhibitors in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: two phase 3 studies. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:592–606. doi: 10.2174/156720511796391935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frolich L., Ashwood T., Nilsson J., Eckerwall G., Sirocco I. Effects of AZD3480 on cognition in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a phase IIb dose-finding study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:363–374. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafii M.S., Walsh S., Little J.T., Behan K., Reynolds B., Ward C. A phase II trial of huperzine A in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;76:1389–1394. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318216eb7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imbimbo B.P., Ottonello S., Frisardi V., Solfrizzi V., Greco A., Seripa D. Solanezumab for the treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:135–149. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers S.L., Doody R.S., Mohs R.C., Friedhoff L.T. Donepezil improves cognition and global function in Alzheimer disease: a 15-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Donepezil Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1021–1031. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider L.S., Mangialasche F., Andreasen N., Feldman H., Giacobini E., Jones R. Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer's disease: an appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Intern Med. 2014;275:251–283. doi: 10.1111/joim.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plassman B.L., Langa K.M., McCammon R.J., Fisher G.G., Potter G.G., Burke J.R. Incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment, not dementia in the United States. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:418–426. doi: 10.1002/ana.22362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meinert C.L., McCaffrey L.D., Breitner J.C. Alzheimer's disease anti-inflammatory prevention trial: design, methods, and baseline results. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeKosky S.T., Fitzpatrick A., Ives D.G., Saxton J., Williamson J., Lopez O.L. The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) study: design and baseline data of a randomized trial of Ginkgo biloba extract in prevention of dementia. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27:238–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shumaker S.A., Legault C., Rapp S.R., Thal L., Wallace R.B., Ockene J.K. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2651–2662. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fargo K.N., Aisen P., Albert M., Au R., Corrada M.M., DeKosky S. 2014 Report on the milestones for the US national plan to address Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:S430–S452. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings J., Lee G., Ritter A., Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2018. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;4:195–214. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roses A.D., Lutz M.W., Saunders A.M., Goldgaber D., Saul R., Sundseth S.S. African-American TOMM40′523-APOE haplotypes are admixture of West African and Caucasian alleles. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:592–601.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu L., Lutz M.W., Wilson R.S., Burns D.K., Roses A.D., Saunders A.M. APOE epsilon4-TOMM40 '523 haplotypes and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in older Caucasian and African Americans. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura A., Nonomura H., Tanaka S., Yoshida M., Maruyama Y., Aritomi Y. Characterization of APOE and TOMM40 allele frequencies in the Japanese population. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;3:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roses A.D., Lutz M.W., Amrine-Madsen H., Saunders A.M., Crenshaw D.G., Sundseth S.S. A TOMM40 variable-length polymorphism predicts the age of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10:375–384. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crenshaw D.G., Gottschalk W.K., Lutz M.W., Grossman I., Saunders A.M., Burke J.R. Using genetics to enable studies on the prevention of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:177–185. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutz M.W., Sundseth S.S., Burns D.K., Saunders A.M., Hayden K.M., Burke J.R. A genetics-based biomarker risk algorithm for predicting risk of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2016;2:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B., Gaiteri C., Bodea L.G., Wang Z., McElwee J., Podtelezhnikov A.A. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 2013;153:707–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane R.M., Farlow M.R. Lipid homeostasis and apolipoprotein E in the development and progression of Alzheimer's disease. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:949–968. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400486-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiman E.M., Chen K., Alexander G.E., Caselli R.J., Bandy D., Osborne D. Correlations between apolipoprotein E epsilon4 gene dose and brain-imaging measurements of regional hypometabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8299–8302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500579102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ronnemaa E., Zethelius B., Sundelof J., Sundstrom J., Degerman-Gunnarsson M., Berne C. Impaired insulin secretion increases the risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;71:1065–1071. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310646.32212.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swerdlow R.H., Khan S.M. A “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis” for sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2003.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cadonic C., Sabbir M.G., Albensi B.C. Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:6078–6090. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roses A.D. Apolipoprotein E affects the rate of Alzheimer disease expression: beta-amyloid burden is a secondary consequence dependent on APOE genotype and duration of disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:429–437. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy P.H., Beal M.F. Amyloid beta, mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic damage: implications for cognitive decline in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato N., Morishita R. The roles of lipid and glucose metabolism in modulation of beta-amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:199. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinney J.W., Bemiller S.M., Murtishaw A.S., Leisgang A.M., Salazar A.M., Lamb B.T. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2018;4:575–590. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sauerbeck A., Gao J., Readnower R., Liu M., Pauly J.R., Bing G. Pioglitazone attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction, cognitive impairment, cortical tissue loss, and inflammation following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2011;227:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knodt A.R., Burke J.R., Welsh-Bohmer K.A., Plassman B.L., Burns D.K., Brannan S.K. Effects of pioglitazone on mnemonic hippocampal function: a blood oxygen level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging study in elderly adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;5:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson G.S., Cholerton B.A., Reger M.A., Baker L.D., Plymate S.R., Asthana S. Preserved cognition in patients with early Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment during treatment with rosiglitazone: a preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:950–958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.11.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romero H.R., Monsch A.U., Hayden K.M., Plassman B.L., Atkins A.S., Keefe R.S.E. TOMMORROW neuropsychological battery: German language validation and normative study. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2018;4:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vellas B., Carrillo M.C., Sampaio C., Brashear H.R., Siemers E., Hampel H. Designing drug trials for Alzheimer's disease: what we have learned from the release of the phase III antibody trials: a report from the EU/US/CTAD Task Force. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zelniker T.A., Wiviott S.D., Raz I., Im K., Goodrich E.L., Bonaca M.P. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393:31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32590-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.US Preventive Services Task Force Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:1997–2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.15450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Guideline on medicinal products for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. 2008. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-medicinal-products-treatment-alzheimers-disease-other-dementias-revision-1_en.pdf

- 46.Mattsson N., Zegers I., Andreasson U., Bjerke M., Blankenstein M.A., Bowser R. Reference measurement procedures for Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers: definitions and approaches with focus on amyloid beta42. Biomark Med. 2012;6:409–417. doi: 10.2217/bmm.12.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.