Highlights

-

•

ALE meta-analysis reveals distributed brain networks for object and spatial functions in individuals with early blindness.

-

•

ALE contrast analysis reveals specific activations in the left cuneus and lingual gyrus for language function, suggesting a reverse hierarchical organization of the visual cortex for early blind individuals.

-

•

The findings contribute to visual rehabilitation in blind individuals by revealing the function-dependent and sensory-independent networks during nonvisual processing.

Keywords: Activation likelihood estimation, Meta-analysis, Neuroimaging, Blindness, Cross-modal plasticity

Abstract

Cross-modal occipital responses appear to be essential for nonvisual processing in individuals with early blindness. However, it is not clear whether the recruitment of occipital regions depends on functional domain or sensory modality. The current study utilized a coordinate-based meta-analysis to identify the distinct brain regions involved in the functional domains of object, spatial/motion, and language processing and the common brain regions involved in both auditory and tactile modalities in individuals with early blindness. Following the PRISMA guidelines, a total of 55 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The specific analyses revealed the brain regions that are consistently recruited for each function, such as the dorsal fronto-parietal network for spatial function and ventral occipito-temporal network for object function. This is consistent with the literature, suggesting that the two visual streams are preserved in early blind individuals. The contrast analyses found specific activations in the left cuneus and lingual gyrus for language function. This finding is novel and suggests a reverse hierarchical organization of the visual cortex for early blind individuals. The conjunction analyses found common activations in the right middle temporal gyrus, right precuneus and a left parieto-occipital region. Clinically, this work contributes to visual rehabilitation in early blind individuals by revealing the function-dependent and sensory-independent networks during nonvisual processing.

1. Introduction

The occipital cortex is organized in a hierarchical structure (Felleman and Van, 1991). Both nature (the innate genetic mechanism) and nurture of experiences work together in occipital development. Initial experience-independent processes include formation of anatomical and physiological maps, where the latter experience-dependent processes include maturation and refinement of the initial structures and established connections (Sengpiel and Kind, 2002). This is in agreement with the proposal that there is a critical period for the effect of visual loss on occipital development (Cohen et al., 1999). Abnormal visual experience during the critical period, such as early blindness (EB), can induce significant plastic changes in the occipital cortices and other intact brain regions. The most striking reorganization occurs in the occipital cortex, which has been historically regarded as a unimodal visual cortex for processing visual stimuli. The cortex begins responding to auditory and tactile inputs in EB individuals, which is a phenomenon known as cross-modal plasticity (Bavelier and Neville, 2002; Pascual-Leone et al., 2005). Importantly, the cross-modal occipital responses in EB individuals appear to have functional relevance for nonvisual processing and may underlie their enhanced auditory and tactile abilities. First, several studies demonstrated a significant correlation between occipital activity and behavior performance during nonvisual tasks in EB individuals (Amedi et al., 2003; Gougoux et al., 2005; Raz et al., 2005; Renier et al., 2010). Second, occipital stimulation induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in EB individuals impairs behavior performance in nonvisual processing, including sound localization, Braille reading, and tactile perception (Amedi et al., 2004; Cohen et al., 1997; Collignon et al., 2006; Kupers et al., 2006). Third, there was a report on a congenitally blind woman with acquired occipital lesions was no longer able to read Braille, although she was a proficient Braille reader before the accident (Hamilton et al., 2000).

The occipital cortex has been shown to be involved in a variety of nonvisual processing paradigms ranging from low cognitive-demand tasks such as sensory perception (Kujala et al., 1995; Röder et al., 1996; Sathian and Prather, 2006) and attention (Liotti et al., 1998; Weaver and Stevens, 2007) to high cognitive-demand tasks such as Braille reading (Burton et al., 2002; Cohen et al., 1997), semantic processing (Burton et al., 2003; Noppeney et al., 2003) and speech processing (Röder et al., 2002). Investigations on the cross-modal plasticity of the occipital cortex associated with visual loss vary widely with respect to the blind group (early- and late-onset blindness), sensory modality (auditory, tactile, and olfactory), imaging modality (functional magnetic resonance/fMRI and positron emission tomography/PET), task domain (perception, attention, imagery, memory, and language), task paradigm and level of task difficulty. Furthermore, the results from a wide range of functional neuroimaging studies can be divergent due to the control task, contrast, and significance level. The functional significance of those cross-modal occipital responses across tasks remains unclear.

Another interesting question involves the function-specific sensory-independent brain organization in EB individuals. In the last decade or so, accumulated evidence from the EB population has shown that the occipital cortices mainly process certain functions, whether they are conveyed by auditory or tactile input (Pascual-Leone and Hamilton, 2001; Ricciardi et al., 2014a). Some authors refer to this phenomenon as the 'supramodal' or ‘metamodal’ organization of the cortex (Pascual-Leone et al., 2005), suggesting that the occipital cortex may be organized according to a certain computation for a particular function, independent of the sensory modality that conveys the input to the brain. To investigate the function-specific sensory-independent brain organization in EB individuals, one should investigate multiple functional tasks simultaneously in the same blind individuals, and the stimuli of the tasks included should be conveyed by different nonvisual modalities. A recent study employed such designs to investigate the spatial processing of auditory and tactile stimuli in EB individuals (Renier et al., 2010). The results demonstrated no modality-specific occipital activation and increased activation of the middle occipital gyrus (MOG) for spatial over non-spatial processing of both auditory and tactile stimuli, suggesting that the function-specific sensory-independent spatial processing occurs in the MOG of EB individuals (Renier et al., 2010). Several neuroimaging reviews on the functional specificity of the visual cortex in EB individuals have recently been published, such as Renier et al. (2014), Ricciardi et al. (2014b), and Kupers and Ptito (2014). One consensus is that the functional specificity of the dual visual streams is only preserved in individuals with EB and not in individuals who lost their vision later in life (Collignon et al., 2012, 2013). However, these studies do not address the question of sensory independence and are qualitative in nature. The present study aims to conduct a quantitative meta-analysis of the literature to provide more solid evidence on the function-specific sensory-independent processing of the occipital cortex in EB individuals.

Although numerous studies in EB have reported occipital activation during nonvisual processing, the functional significance and function-specific sensory-independence of these cross-modal occipital responses have yet to be systematically examined. We have only identified one meta-analysis study in this field, which has several limitations (Ricciardi et al., 2014b). First, the meta-analysis involved only a small number of studies, resulting in limited statistical power. Second, the study only investigated the role of sensory modality, but not functional specialization. Third, the study did not conduct conjunction analysis on auditory and tactile modalities, and it did not investigate sensory-independent processing in EB individuals. To overcome these limitations, the present study sought to characterize the function-specific sensory-independent cross-modal responses that were consistently recruited in EB using a large data set. Meta-analysis is useful for examining consistency patterns across paradigms and studies by integrating data into an overall statistical analysis. The present study employed activation likelihood estimation (ALE) to draw a consensus across neuroimaging studies in EB individuals. The present meta-analysis sought to address three main aims:

-

•

Aim 1: Which brain regions are recruited for each specific function (object, spatial, and linguistic) (aim 1a)? Which brain regions are univocally and selectively recruited in each functional domain (aim 1b)?

-

•

Aim 2: For each function, which brain regions are selectively recruited in EB individuals compared with sighted control (SC) individuals?

-

•

Aim 3: For EB individuals, which brain regions are recruited in both auditory and tactile modalities?

2. Material and methods

2.1. Literature search and selection

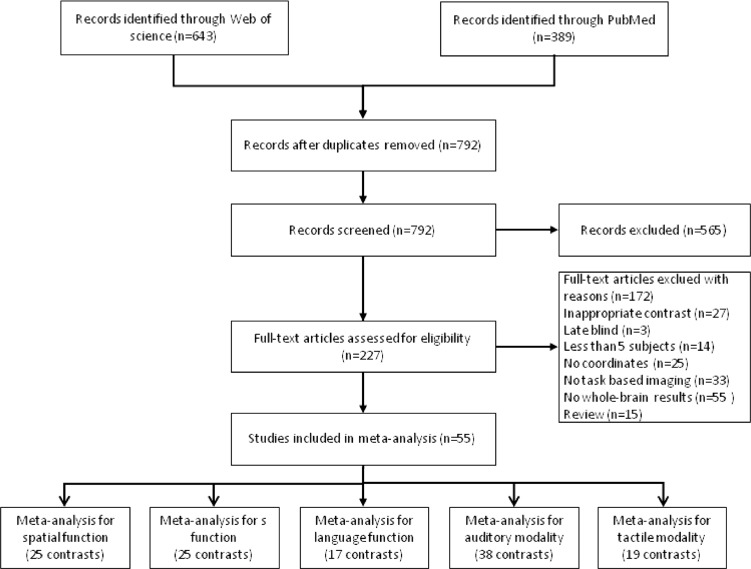

A literature search was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2015). The PubMed and Web of Science databases were searched to identify functional neuroimaging studies investigating congenitally blind and EB individuals were published in English between Jan 1995 and Dec 2018. We used the following search terms: (fMRI OR PET OR neuroimaging) AND (early blind OR congenitally blind OR blindness). All identified articles were first screened by title, and then abstract. The articles that were excluded included review articles, articles without a blind group, and articles not using task based fMRI or PET techniques. The remaining articles were imported to EndNote X7 and further reviewed through the following criteria: (1) coordinates of activation were reported in either Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space (Collins et al., 1994) or standardized Talairach space (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988); (2) the contrast was within-group based, rather than between-group based; (3) whole-brain analyses to obtain activation results; (4) univariate approach that revealed localized increased activation; and (5) a minimum of five participants were included in the final analyses. A flow chart illustrating the detailed study selection process is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of literature search and selection process.

A total of 55 published articles satisfied the above criteria (Table 1). For studies involved with multiple and independent contrasts, only the contrast that most strongly reflected the process of interest was included in each analysis. For instance, several studies involved blind participants performing a task with a certain sensory substitution device (Arno et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2012; Ptito et al., 2005; Striem-Amit et al., 2012); thus, the contrasts at post-training were selected. Three out of 55 included articles (Gougoux et al., 2005; Voss et al., 2008, 2011) performed the same experiment in two independent samples, which were both included in the analysis without the need to adjust for multiple contrasts. It is noted that several studies used the same subject sample to perform multiple relevant tasks (Park et al., 2011; Renier et al., 2010; Striem-Amit et al., 2011), and a potential overlap of the subject samples in the selected publications cannot be ruled out.

Table 1.

Summary of publications included for the main meta-analyses.

| Publication | Number of blind subjects | Imaging | Contrast | Functional domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abboud et al. (2015) | 9 EB, 12 SC | fMRI | Numerical Vs. Letter and color | Other function |

| Amedi et al. (2003) | 10 EB, 7 SC | fMRI | Verb generation Vs. Auditory noise control | Language |

| Amedi et al. (2010) | 8 EB, 8 SC | fMRI | Object recognition Vs. Sensory motor control | Object |

| Arenas et al. (2016) | 10 EB, 15 SC | fMRI | Tonal processing Vs Atonal processing | Other function |

| Arno et al. (2001) | 6 EB, 6 SC | PET | Pattern recognition Vs. Detection of noise | Object |

| Bauer et al. (2015) | 8 EB, 7 SC | fMRI | Symmetry detection Vs. Motor control | Object |

| Bedny et al. (2010) | 10 EB, 21 SC | fMRI | Motion perception Vs. Rest | Spatial |

| Bedny et al. (2011) | 11 EB, 17 SC | fMRI | Perception of sentence and word lists Vs. Perception of jabberwocky and nonword lists | Language |

| Bonino et al. (2015) | 9 EB, 10 SC | fMRI | Spatial imagery Vs. Control | Spatial |

| Büchel et al. (1998) | 6 EB | PET | Braille reading Vs. Auditory processing | Language |

| Burton et al. (2002a) | 7 EB | fMRI | Verb generation to Braille stimuli Vs. Passive touching Braille pattern stimuli | Language |

| Burton et al. (2002b) | 8 EB, 8 SC | fMRI | Verb generation to heard nouns Vs. Passive listening to indecipherable sounds | Language |

| Chan et al. (2012) | 11 EB, 14 SC | fMRI | Spatial judgment of target sound Vs. Sound detection | Spatial |

| Cohen et al. (1999) | 8 EB | PET | Braille discrimination Vs. Rest | Language |

| Collignon et al. (2011) | 11 EB, 11 SC | fMRI | Spatial judgment Vs. Pitch judgment | Spatial |

| Deutschlander et al. (2009) | 7 EB | fMRI | Imagery of locomotion Vs. Rest | Spatial |

| De Volder et al. (2001) | 6 EB, 6 SC | PET | Mental imagery of object Vs. Control | Object |

| Dormal, 2016,Dormal et al. (2016) | 15 EB, 13 SC | fMRI | Motion perception Vs. Static perception | Spatial |

| Dormal et al. (2017) | 16 EB | fMRI | Recognition of object sounds Vs. Recognition of object scrambled sounds | Object |

| Katja et al. (2009) | 12 EB | fMRI | Performing kinesthetically guided hand movements | Spatial |

| Gagnon et al. (2012) | 11 EB, 14 SC | fMRI | Maze learning Vs. Rest | Spatial |

| Gizewski et al. (2003) | 12 EB | fMRI | Braille reading | Language |

| Gougoux et al. (2005) | 5 EB, 7 SC | fMRI | Binaural sound localization Vs. Control | Spatial |

| 7 EB | fMRI | Binaural sound localization Vs. Control | Spatial | |

| Guerrero et al. (2016) | 10 EB, 15 SC | fMRI | Tonal Vs. Atonal musical perception | Other functions |

| Halko et al. (2014) | 9 EB | fMRI | Virtual navigation Vs. Motor control | Spatial |

| He et al. (2013) | 14 EB, 16 SC | fMRI | Size judgment Vs. Control | Object |

| Hüfner et al. (2009) | 11 EB, 12 SC | fMRI | Eyes Open Vs. Eyes Closed | Other function |

| Kanjlia et al. (2016) | 17 EB, 19 SC | fMRI | Decide whether two math equations were same or not Vs. Language control | Other function |

| Kim et al. (2017) | 10 EB | fMRI | Braille words Vs. Tactile controls | Language |

| Kitada et al. (2013) | 17 EB, 22 SC | fMRI | Identification of facial expressions Vs. Shoes | Object |

| Kupers et al. (2010) | 10 EB, 10 SC | fMRI | Recognition of a learned route Vs. Recognition of a scrambled route | Spatial |

| Lambert et al. (2004) | 6 EB, 6 SC | fMRI | Mental imagery of objects Vs. Passive listening to abstract words | Object |

| Lane et al. (2015) | 16 EB, 18 SC | fMRI | Sentence Vs Nonword | Language |

| Lewis et al. (2011) | 10 EB, 14 SC | fMRI | Recognition of human action sounds Vs. backward-played versions of those sounds | Other function |

| Ma and Han (2010) | 19 EB, 23 SC | fMRI | Valence judgment Vs. Rest | Other function |

| Matteau et al. (2010) | 8 EB, 9 SC | fMRI | Motion perception Vs. Rest | Spatial |

| Ofan and Zohary, 2007 | 9 EB | fMRI | Verb generation to heard nouns Vs. Verb repeat to heard nouns | Language |

| Park et al. (2011) | 10 EB, 10 SC | fMRI | 2-back working memory of words Vs. 0-back | Language |

| 2-back working memory of location Vs. 0-back | Spatial | |||

| 2-back working memory of pitch Vs. 0-back | Object | |||

| Pishnamazi et al. (2016) | 16 EB | fMRI | Touch Braille letter Vs. Rest | Language |

| Ptito et al. (2005) | 6 EB, 5 SC | PET | Orientation discrimination Vs. Rest | Spatial |

| Ptito et al. (2009) | 7 EB, 6 SC | PET | Motion discrimination Vs. Rest | Spatial |

| Ptito et al. (2012) | 8 EB, 10 SC | fMRI | Shape Vs. Rest | Object |

| Raz et al. (2005) | 9 EB | fMRI | Recognition of words Vs. Phonological control | Language |

| Renier et al. (2010) | 12 EB, 12 SC | fMRI | Identification Vs. Detection | Object |

| Localization Vs. Detection | Spatial | |||

| Renier et al. (2013) | 10 EB, 10 SC | fMRI | Auditory discrimination or categorization Vs. Olfactory discrimination or categorization | Language |

| Sadato et al. (1998) | 8 EB, 10 SC | PET | Braille reading Vs. Rest | Language |

| Angle and width discrimination Vs. Rest | Object | |||

| Sigalov et al. (2016) | 8 EB | fMRI | Reading with semantic stimuli Vs. Reading with scrambled stimuli | Language |

| Stevens et al. (2007) | 12 EB, 15 SC | fMRI | Discrimination with cue Vs. Discrimination without cue | Other function |

| Striem-Amit et al. (2012) | 8 EB | fMRI | Recognition of letters Vs. Control | Language |

| Striem-Amit et al. (2011) | 11 EB, 9 SC | fMRI | Shape Vs. Location | Object |

| Location Vs. Shape | Spatial | |||

| Striem-Amit and Amedi (2014) | 7 EB, 7 SC | fMRI | Perceive full-body shapes Vs. Perceive other objects | Object |

| Tao et al. (2015) | 15 EB | fMRI | Sound localization Vs. Target detection | Spatial |

| Vanlierde et al. (2003) | 5 EB, 5 SC | PET | Spatial imagery of matrix Vs. Memory task | Spatial |

| Voss et al. (2008) | 5 EB, 7 SC | PET | Sound source discrimination Vs. Rest | Spatial |

| 7 EB | PET | Sound source discrimination Vs. Rest | Spatial | |

| Voss et al. (2011) | 5 EB, 7 SC | PET | Location differentiation of a sound pair (same/different) Vs. Auditory perception | Spatial |

| 7 EB | PET | Location differentiation of a sound pair (same/different) Vs. Auditory perception | Spatial | |

| Weeks et al. (2000) | 9 EB, 9 SC | PET | Auditory localization and joystick movement Vs. Rest | Spatial |

2.2. ALE meta-analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted according to the guidelines (Müller et al., 2018). All meta-analyses were carried out using the ALE technique implemented in Ginger ALE, Version 3.0.2 (Eickhoff et al., 2009; Laird et al., 2005). At first, studies that used MNI coordinates were converted to Talairach coordinates (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) using icbm2tal (Lancaster et al., 2007). Then, all Talairach coordinates were imported into the ALE software to perform meta-analysis (Eickhoff et al., 2009; Laird et al., 2005). The reported coordinates were modeled with a three-dimensional Gaussian probability distribution, and the maximum probabilities associated with each primary locus of activation were combined to create modeled activation (MA) maps for each individual experiment. To determine the anatomical convergence across experiments, the union of all MA maps was then computed voxel by voxel by considering sample size in each experiment. For both the EB and SC groups, we ran a series of separate ALE analyses for each function, dividing the studies into object function, spatial function, linguistic function, and other functions (aim 1a). For the EB group, each function-specific meta-analysis was contrasted against the meta-analysis from the remaining functions pooled together (Laird et al., 2005) (aim 1b). For each function, contrast analyses were conducted between the EB and SC groups (aim 2). Finally, different meta-analyses were performed separately for auditory and tactile modalities, and then conjunction analyses were conducted on both sensory modalities (aim 3). For within-group analyses, the ALE statistic was calculated at each voxel, and the results were corrected for multiple comparisons using the cluster-level family-wise error (FWE) method (Eickhoff et al., 2016). The voxel-level threshold was set at P < 0.001, and the cluster-level threshold was set at P < 0.05 using 5000 permutations for correcting multiple comparisons. For between-group contrast analyses, the ALE maps were corrected using a false discovery rate (FDR) method with a corrected P value less than 0.05 and 20 mm3 minimum volume size.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial function

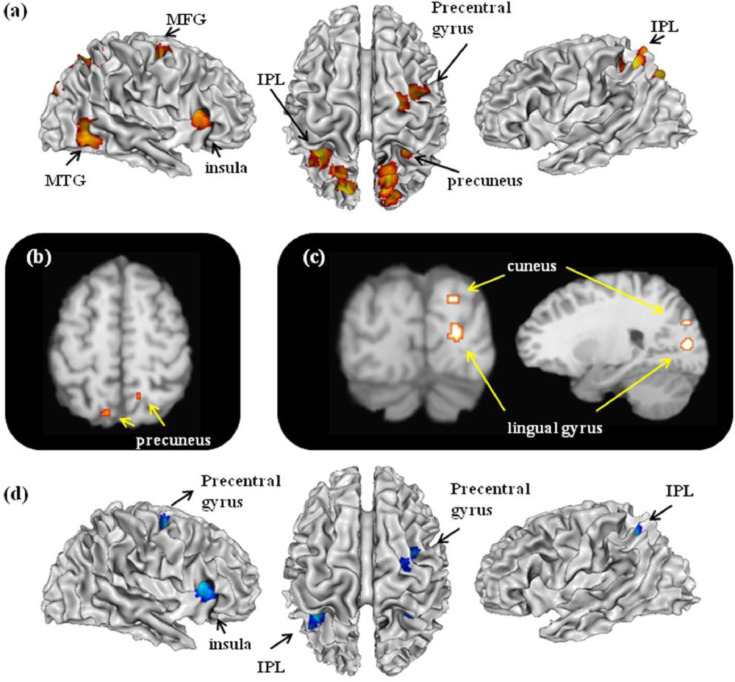

For the spatial function, 25 contrasts with 256 foci were analyzed in 224 EB individuals, and 19 contrasts with 196 foci were analyzed in 191 SC individuals. The results are reported in Table 2 and graphically presented in Fig. 2. For the EB group, the meta-analysis on the studies involving spatial functions revealed consistent activations in the bilateral precuneus extending to superior parietal lobule (SPL), right middle temporal gyrus (MTG), right parahippocampal gyrus, left inferior parietal lobule (IPL), right middle frontal gyrus (MFG) extending to precentral gyrus, right insula, and right cuneus. As compared with other functions, spatial function specifically activated bilateral precuneus. For the SC group, consistent activations were found in the bilateral insula and right parito-frontal area, including IPL, precuneus, MFG, and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG). Contrast analysis revealed more consistent activations in the right lingual gyrus and right cuneus in EB group as compared with SC group. Conjunction analysis on EB and SC revealed consistent activations in the right insula, left IPL, right precuneus, and right precentral gyrus.

Table 2.

Brain areas activated in spatial functions.

| Cluster size | Brain region | Brodmann area | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| area | x | y | z | ||

| Early blind subjects | |||||

| 3152 | Precuneus | 7 | 16 | −66 | 46 |

| Precuneus | 7 | 12 | |||

| −72 | 40 | ||||

| Cuneus | 18 | 18 | −82 | 28 | |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | 7 | 16 | −58 | 58 | |

| 2704 | Precuneus | 7 | −14 | −74 | 42 |

| Precuneus | 7 | −18 | −60 | 50 | |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | 7 | −10 | −68 | 52 | |

| 1736 | Middle Temporal Gyrus | 37 | 44 | −60 | −4 |

| Parahippocampal Gyrus | 19 | 38 | −50 | −6 | |

| 1576 | Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | −32 | −52 | 44 |

| 1496 | Precuneus | 7 | 30 | −42 | 40 |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | 7 | 28 | −56 | 40 | |

| 1256 | Middle Frontal Gyrus | 6 | 24 | −14 | 54 |

| Precentral Gyrus | 6 | 32 | −8 | 50 | |

| Precentral Gyrus | 6 | 38 | −8 | 50 | |

| 1072 | Insula | 13 | 32 | 16 | 14 |

| Insula | 13 | 34 | 22 | 6 | |

| 840 | Cuneus | 17 | 20 | −84 | 8 |

| Sighted control subjects | |||||

| 2408 | Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | 44 | −50 | 46 |

| Precuneus | 7 | 30 | −42 | 40 | |

| Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | 54 | −42 | 44 | |

| 2240 | Insula | 13 | 32 | 18 | 10 |

| Insula | 13 | 32 | 22 | 4 | |

| 1912 | Middle Frontal Gyrus | 6 | 28 | −6 | 58 |

| 1840 | Insula | 13 | −30 | 18 | 10 |

| Insula | * | −34 | 16 | 2 | |

| 1648 | Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | −36 | −50 | 38 |

| 936 | Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 9 | 54 | 10 | 30 |

| Specific activation in early blind subjects (spatial VS non-spatial) | |||||

| 216 | Precuneus | 7 | 14 | −58 | 58 |

| 72 | Precuneus | 7 | −10 | −69 | 51 |

| Hyper-activation (blind VS sighted) | |||||

| 368 | Lingual Gyrus | 17 | 22 | −85 | 8 |

| 136 | Cuneus | 18 | 20 | −84 | 27 |

| Conjunctive-activation (blind and sighted) | |||||

| 856 | Insula | 13 | 32 | 16 | 12 |

| Insula | 13 | 34 | 22 | 6 | |

| 560 | Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | −34 | −52 | 42 |

| 464 | Precuneus | 7 | 30 | −42 | 40 |

| 416 | Precentral Gyrus | 6 | 28 | −10 | 52 |

Fig. 2.

Spatial functions related activations. The figure (a) represents 3D brain activations for spatial functions in the EB group; (b) specific activations in the EB group, spatial versus non-spatial functions; (c) hyper-activations in the EB group compared with SC group; (d) common activations in both EB and SC groups.

3.2. Object function

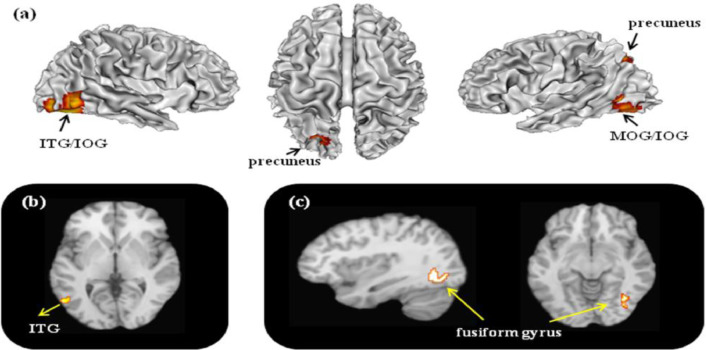

For the object function, 15 contrasts with 163 foci were analyzed in 145 EB individuals, and 14 contrasts with 147 foci were analyzed in 139 SC individuals. The results are reported in Table 3 and graphically presented in Fig. 3. For the EB group, the meta-analysis on the studies involving object functions revealed consistent activations in the bilateral inferior occipital gyrus (IOG), left MOG, left precuneus, and bilateral cerebellum. As compared with other functions, object function was specifically activated left inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) and right cerebellum. For the SC group, consistent activations were found in the left angular gyrus and bilateral medial frontal gyrus (MeFG). Contrast analysis revealed more consistent activations in the left fusiform gyrus in EB group as compared with SC group. Null results were found to be commonly activated for both EB and SC individuals.

Table 3.

Brain areas activated in object functions.

| Cluster size | Brain region | Brodmann area | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| area | x | y | z | ||

| Early blind subjects | |||||

| 4840 | Cerebellum | * | 32 | ||

| −66 | −16 | ||||

| Inferior Temporal Gyrus | * | 40 | −62 | −4 | |

| Inferior Occipital Gyrus | 18 | 32 | −78 | −8 | |

| 3048 | Middle Occipital Gyrus | 37 | −46 | −64 | −4 |

| Cerebellum | * | −32 | −64 | −18 | |

| Inferior Occipital Gyrus | 18 | −32 | −78 | −8 | |

| 952 | Precuneus | 7 | −20 | −72 | 42 |

| Sighted control subjects | |||||

| 1136 | Angular Gyrus | 39 | −28 | −60 | 36 |

| 1032 | Medial Frontal Gyrus | 6 | 2 | 2 | 52 |

| Medial Frontal Gyrus | 6 | −4 | 2 | 50 | |

| Specific activation in early blind subjects (object VS non-object) | |||||

| 1160 | Cerebellum | * | 33 | −73 | −17 |

| 376 | Inferior Temporal Gyrus | 19 | −53 | −66 | 0 |

| Inferior Temporal Gyrus | 37 | −48 | −64 | 1 | |

| Hyper-activation (blind VS sighted) | |||||

| 752 | Fusiform Gyrus | 19 | 36 | −67 | −6 |

| Conjunctive-activation (blind and sighted) | |||||

| NA | |||||

Fig. 3.

Object functions related activations. The figure (a) represents 3D brain activations for object functions in the EB group; (b) specific activations in the EB group, object versus non-object functions; (c) hyper-activations in the EB compared with SC group .

3.3. Linguistic function

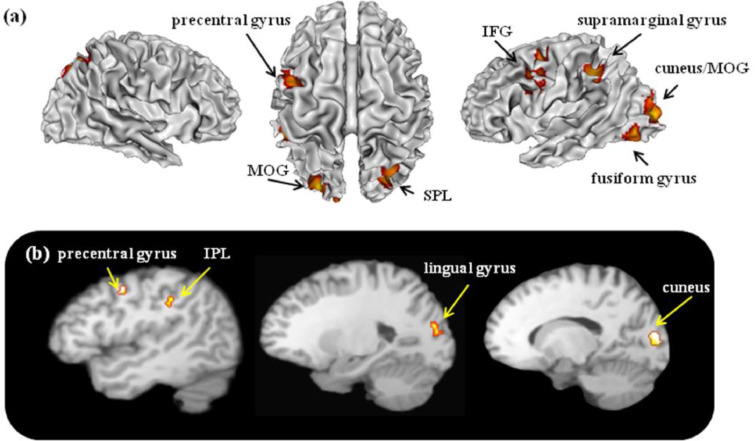

For the linguistic function, 17 contrasts with 221 foci were analyzed in 166 EB individuals. Among the included studies, only 6 studies investigated SC individuals and provided coordinate details. As a result, we did not conduct analysis on linguistic function on SC group. The results are reported in Table 4 and graphically presented in Fig. 4. The meta-analysis on the studies involving language functions revealed consistent activations in the left cuneus extending to MOG and lingual gyrus, left fusiform gyrus, right precuneus extending to SPL, left precentral gyrus, left IFG, and left supramarginal gyrus. As compared with other functions, language processing was associated with left cuneus extending to lingual gyrus, left precentral gyrus, and left IPL.

Table 4.

Brain areas activated in language functions.

| Cluster size | Brain region | Brodmann area | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| area | x | y | z | ||

| Early blind subjects | |||||

| 5712 | Cuneus | 17 | −16 | −90 | 6 |

| Middle Occipital Gyrus | 18 | −24 | −84 | 16 | |

| Lingual Gyrus | 17 | −6 | −86 | 2 | |

| 2624 | Fusiform Gyrus | 19 | −42 | −68 | −10 |

| 1792 | Precuneus | 19 | 26 | −72 | 36 |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | 7 | 28 | −66 | 48 | |

| 1712 | Precentral Gyrus | 6 | −40 | −4 | 44 |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 9 | −50 | 2 | 24 | |

| Precentral Gyrus | 6 | −40 | 2 | 32 | |

| 1200 | Supramarginal Gyrus | 40 | −44 | −38 | 34 |

| Specific activation in early blind subjects (language VS non-language) | |||||

| 1160 | Cuneus | 17 | −16 | −90 | 10 |

| Lingual Gyrus | 17 | −21 | −84 | 17 | |

| 176 | Precentral Gyrus | 6 | −43 | −2 | 43 |

| 160 | Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | −46 | −37 | 34 |

Fig. 4.

Linguistic functions related activations in the EB individuals. The figure (a) represents 3D brain activations for linguistic functions in the EB group; (b) represents specific activations in the EB group, linguistic versus non- linguistic functions.

3.4. Auditory and tactile modalities

For the auditory modality, 38 contrasts with 432 foci were analyzed in 390 EB individuals. For the tactile modality, 19 contrasts with 275 foci were analyzed in 180 EB individuals. Conjunction analysis on auditory and tactile modalities revealed common activations in the right MTG and a parieto-occipital network, including precuneus, IPL, supramarginal gyrus, lingual gyrus, and MOG (Table 5).

Table 5.

Brain areas commonly activated in auditory and tactile modalities in early blindness.

| Cluster size | Brain region | Brodmann area | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| area | x | y | z | ||

| 1080 | Middle Temporal Gyrus | 37 | 42 | −62 | −4 |

| 712 | Precuneus | 7 | 22 | −72 | 38 |

| 624 | Lingual Gyrus | 17 | −20 | −90 | 4 |

| Lingual Gyrus | 17 | −16 | −88 | 6 | |

| 624 | Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | −32 | −54 | 44 |

| 488 | Precuneus | 7 | −16 | −74 | 40 |

| 296 | Middle Occipital Gyrus | 37 | −46 | −66 | −6 |

| Fusiform Gyrus | 19 | −38 | −72 | −10 | |

| 200 | Supramarginal Gyrus | 40 | −42 | −40 | 36 |

| 168 | Precuneus | 7 | 18 | −64 | 46 |

| Precuneus | 7 | 16 | −68 | 44 | |

4. Discussion

The past decade has witnessed an explosion of interest in examining neural underpinnings of cross-modal plasticity following sensory loss (Borst and Gelder, 2018; Heimler et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2018). Although the existence of such cross-modal changes is certain, the properties of these cross-modal adaptations remain unclear. The objective of the current work was to quantitatively synthesize the results of previous neuroimaging studies on EB and SC individuals, and to characterize brain regions specifically involved in different functional domains and commonly activated in both auditory and tactile modalities. The main findings are as follows: (1) the cross-modal occipital responses in EB individuals had functional specification for language processing, but not for spatial and object processing; (2) the left cuneus and lingual gyrus take on language processing as a result of early visual loss; (3) the dual visual streams seem to be preserved in EB individuals, that is the dorsal stream is for spatial/motion processing and the ventral stream is for object processing; (4) the cross-modal occipital responses in EB individuals do not dependent on sensory modality.

4.1. Spatial function

The current results found a spatial network for the EB individuals, which comprises dorsal frontal and parietal regions in bilateral hemispheres, insula, MTG, and cuneus in right hemisphere. Importantly, conjunction analysis revealed a core network common for both EB and SC individuals, which comprises the right insula, right precuneus, right precentral gyrus, and left IPL. The dorsal frontoparietal network in both hemispheres, including MFG, precuneus, and SPL, is largely overlapped with the spatial network in sighted individuals revealed by a meta-analysis study (Cona and Scarpazza, 2019). The authors conducted systematic review and coordinate-based meta-analysis on 133 neuroimaging studies that are dealing with spatial processing in sighted individuals, and identified a core network underlying spatial function comprises dorsal frontoparietal regions, presupplementary motor area, anterior insula, and frontal operculum in bilateral hemispheres (Cona and Scarpazza, 2019). The common dorsal frontoparietal network in our current results and the meta-analysis results of spatial function have two important indications. First, there is a shared mechanism underlying the spatial functions in sighted and blind individuals. One proposed mechanism is attentional orientation, which is underlying a variety of tasks requiring the internal maintenance of task-related representations, such as mental imagery (Kosslyn, 2005) and working memory (Nobre et al., 2004). Second, the common dorsal frontoparietal network is supramodal and mediates attentional orienting to all sensory modalities (Macaluso, 2010; Posner and Peterson, 2012).

The contrast results illustrated that the bilateral precuneus was specifically activated for processing spatial information over nonspatial information in EB individuals. This is supported by the multisensory account for spatial processing. Spatial cues, such as orientation, distance, and motion, can be obtained through multiple sensory modalities. The dorsal stream appears to be shaped by spatial processing in not only visual but also tactile and auditory modalities (Katja et al., 2009; Sereno and Huang, 2014). For sighted individuals, several parietal regions, including the precuneus, are identified as multisensory operators for spatial processing (Renier et al., 2009). After visual loss, the precuneus of EB individuals could be activated by the spatial processing of auditory and tactile stimuli. Involvement of the precuneus was reported in EB individuals during sound localization (Gougoux et al., 2005; Tao et al., 2015), tactile maze learning (Gagnon et al., 2012), route recognition (Kupers et al., 2010), and visuo-spatial imagery (Vanlierde et al., 2003). However, the null findings on the occipital region are not consistent with previous findings suggesting that the dorsal visual regions respond preferentially to spatial functions (Collignon et al., 2011; Renier et al., 2010). We provide two reasons for this discrepancy. First, rather than separate occipital regions, EB individuals may rely on strengthened cortico-cortical connections between parietal and visual areas (Kupers et al., 2006; Leo et al., 2012; Ptito et al., 2005; Wittenberg et al., 2004). Second, spatial information is processed in the service of several different cognitive functions, including perception, attention, working memory, mental imagery, and navigation. This is supported by the conjunction results suggesting a core spatial network common for both EB and SC individuals. As a consequence of visual loss, cross-modal plastic changes occur in those cognitive functions differently. The contrast analysis between the two subject groups revealed more activations at the right cuneus and right lingual gyrus. The right cuneus is a subregion mainly located in the right dorsal occipital stream, which has been extensively documented as subserving visuo-spatial/motion functions in sighted individuals. It suggests that the right cuneus maintain their functional role of spatial processing in early blind individuals. The lingual gyrus is a primary visual region located along the dorsal stream and has been reported to be involved during direction and motion discrimination (Cornette et al., 1998) and spatial learning in navigational space (Nemmi et al., 2013).

4.2. Object function

The contrast analysis of object versus non-object functions revealed consistent activations in the left ITG and right cerebellum for object function. The stereotactic coordinates of our ITG activation (x=−53, y=−66, z = 0) are very close to those reported in previous studies (Amedi et al., 2010; Pietrini et al., 2004; Ptito et al., 2012). For instance, Pietrini and coworkers found category-related patterns of responses in the ITG in a group of EB participants and concluded that the representation of objects in the ventral visual pathway is a representation of abstract object features (Pietrini et al., 2004). Another study found stronger BOLD responses in the ITG during nonhaptic shape recognition through a tongue display unit (Ptito et al., 2012). Similarly, involvement of the ITG has been reported in sighted individuals while performing multisensory visual/tactile or auditory/visual object processing (James et al., 2002; Naumer et al., 2009; Stevenson and James, 2009).

According to human anatomy, the ITG is part of the lateral occipital cortex (LOC/LOtv), which is regarded as an object-selective area in the ventral visual pathway (Malach et al., 1995). Stimulation of the LOC disrupts object recognition by the use of a sensory substitution device in EB individuals but not in blindfolded sighted controls (Merabet et al., 2009). The LOC seems to play a fundamental role in object recognition in EB. Previous studies have shown further that this region responds selectively to objects across sensory modalities (Amedi et al., 2001, 2002, 2007; Stilla et al., 2008). It seems that the LOC is multisensory in nature (Lacey and Sathian, 2012) and provides modality-independent representations of objects. This is supported by effective connectivity data indicating bottom-up projections from the primary somatosensory cortex to the LOC (Deshpande et al., 2008; Peltier et al., 2007) and by functional connectivity data indicating strengthened functional connectivity between the auditory cortex and LOC during auditory-shape processing (Kim and Zatorre, 2011). Taken together, the findings suggested that the LOC hosts a trisensory representation of objects and plays an important role in object recognition in sensory loss.

The contrast results suggested more activations in the right fusiform gyrus for object function in the EB group compared with the SC group. The fusiform gyrus, known as the temporo-occipital gyrus, is located within the LOC. Involvement of the fusiform gyrus has been reported in sighted individuals while performing multisensory visual/tactile or auditory/visual object processing (James et al., 2002; Naumer et al., 2009; Stevenson and James, 2009). Tanja et al. (2011) designed two compensatory experiments to pinpoint the neural correlates representing object-specific information of trisensory modalities. In the first experiment, the authors identified that the fusiform gyrus was consistently activated by object processing in visual, auditory, and tactile modalities. The second experiment revealed that the same fusiform gyrus was activated during multisensory matching of object-related information across the three sensory modalities. Importantly, lesion studies provide evidence indicating that damage to the fusiform gyrus results in deficits in a variety of object recognition tasks (Farah et al., 1995; Feinberg et al., 1994; Moscovitch et al., 1997). In parallel, activation of the fusiform gyrus was also observed in EB individuals during pattern and form recognition using a sensory substitution device (Arno et al., 2001; Ptito et al., 2012), mental imagery of shape (De Volder et al., 2001), and even olfactory recognition of an object (Renier et al., 2013). Furthermore, a previous study showed that the involvement of the fusiform gyrus in EB during tactile recognition of objects is category-related (Pietro et al., 2004). Taken together, the findings suggest that the fusiform gyrus also hosts a trisensory representation of objects and plays an important role in object recognition in sensory loss.

4.3. Linguistic function

A left-lateralized language network comprising the prefrontal, lateral temporal, and temporoparietal cortices has been consistently reported in the literature (Chee et al., 1999; MacSweeney et al., 2008). The neural systems that support linguistic functions are particularly plastic early in life (MacSweeney et al., 2008; Mayberry et al., 2011). Due to early visual loss and delays in language acquisition, the neural basis of language processing is modified in EB individuals (Allen et al., 2013; Mayberry and Kluender, 2018). In addition to the classic language network, visual areas are also activated in EB individuals during language related tasks, such as Braille reading, verb generation, lexical retrieval, and sentence comprehension (Büchel et al., 1998; Burton et al., 2002; Cohen et al., 1999; Sadato et al., 1996). The activation of these visual regions is sensitive to manipulations of grammatical complexity (Lane et al., 2015; Röder et al., 2002). Disruption of the occipital regions by TMS impairs performance on Braille reading and verb generation (Amedi et al., 2004; Cohen et al., 1997; Hamilton et al., 2000; Maeda et al., 2003). However, it is not known whether these occipital regions are selectively involved in the processing of linguistic over nonlinguistic stimuli. We propose that distinct occipital regions are involved in linguistic and nonlinguistic functions and that the occipital regions for language processing are strongly left lateralized. Consistent with this idea, the current results revealed consistent activations of the left cuneus and left lingual gyrus that are selectively involved in linguistic processing. This is a novel finding.

After visual loss in early life, the left cuneus and left lingual gyrus in EB develop a specialization for language processing and are incorporated into the language system during development. This is in agreement with the proposal of 'reverse hierarchical organization' of the visual cortex for EB individuals. In normal vision individuals, the primary visual cortex (V1) receives input from the lateral geniculate nucleus, and the information is then sent to the extrastriate visual areas (V2-V4). Along the hierarchical processing pathways, neuronal response properties become increasingly complex, and inputs with low-level properties are transformed into more abstract representations. In EB individuals, however, accumulating evidence suggests a reverse functional hierarchy with V1 activated preferentially by higher cognitive functions such as language and memory tasks (Bedny et al., 2011; Burton et al., 2003; Raz et al., 2005; Sadato et al., 1996). For instance, a strong correlation has been found between activation of V1 and performance on verbal memory and language-related tasks (Amedi et al., 2003). Interference by brain stimulation in the occipital pole reduced accuracy on a verbal-generation task in EB subjects, and the most common error was semantic rather than phonological (Amedi et al., 2004).

4.4. Auditory and tactile modality

Both tactile and auditory tasks produced common activations at the right MTG, right precuneus, and a left parieto-occipital area, including IPL, precuneus, supramarginal gyrus, lingual gyrus, MOG, and fusiform gyrus. . This finding lends support to the proposal of a 'supramodal' organization of brain (Striem-Amit et al., 2011; Voss and Zatorre, 2012). Recent studies used multivariate analyses to reveal a shared coding of specific content, such as motion, shape, and semantic knowledge, in congenitally blind individuals across different sensory modalities (Dormal et al., 2016; Handjaras et al., 2016; Mahon et al., 2009). Studies using sensory-substitution devices also support the proposal of supramodal organization of occipital cortex that is sensory independent (Amedi et al., 2007; Ptito et al., 2012).

4.5. Clinical implications

The current findings provide important support for the proposal of a function-specific sensory-independent brain organization in EB individuals. This suggests that the brains of congenitally and early blind individuals are organized according to functional specializations of the normal visual cortex, but not to sensory modalities. This has great contributions to rehabilitation for congenitally and early blind individuals via sensory substitution devices (SSDs). First, the SSDs can be better designed according to functions, such as localization SSDs, object recognition SSDs, and linguistic SSDs. Second, the SSDs can be evolved from processing simple sensory stimuli to processing more complex information, such as faces and emotion. Finally, given that the brain is organized independent of sensory modality, the design of SSDs and training on using SSDs can utilize multiple sensory modalities to facilitate the interpretation of complex information conveyed by the SSDs.

5. Limitations

The study has several intrinsic limitations. First, the subjects consisted of not only congenitally blind individuals, but also individuals with early blindness. The onset age to define early blindness varied across the studies. The discrepancies in the population may have affected the results and conclusions. Second, the contrast analyses were affected by an unbalanced number of studies targeting different functions, which may have affected the resulting number and dimension of the clusters. Finally, the limited number of linguistic studies on SC individuals did not allow us to conduct contrast analysis between the EB and SC groups. Therefore, differences and similarities between EB and SC individuals in terms of the neural correlates underlying linguistic function await further investigation.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of the meta-analysis suggest that the dual streams seem to be preserved in EB individuals, that is, the precuneus (dorsal stream) is for spatial/motion processing, and the angular gyrus and medial frontal gyrus (ventral stream) are for object processing. However, the cross-modal occipital responses in EB individuals had functional specifications for linguistic processing but not for spatial and object processing. The left cuneus and lingual gyrus take on linguistic processing in the presence of early visual loss. The 'supramodal' organization of the brain has been evidenced in the right MTG, right precuneus and a left parieto-occipital area.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest: the authors declare that they have no existing conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grants awarded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China to Tao (81601969) and Ren (31922030), and the grants awarded by the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (2018B030334001).

Contributor Information

Chetwyn C H Chan, Email: Chetwyn.Chan@polyu.edu.hk.

Qian Tao, Email: taoqian16@jnu.edu.cn.

References

- Abboud S., Maidenbaum S., Dehaene S., Amedi A. A number-form area in the blind. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6026. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.S., Emmorey K., Bruss J., Damasio H. Neuroanatomical differences in visual, motor, and language cortices between congenitally deaf signers, hearing signers, and hearing non-signers. Front Neuroanat. 2013;7:26. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2013.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A., Jacobson G., Hendler T., Malach R., Zohary E. Convergence of visual and tactile shape processing in the human lateral occipital complex. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1202–1212. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.11.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A., Knecht S., Cohen L.G. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the occipital pole interferes with verbal processing in blind subjects. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1266. doi: 10.1038/nn1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A., Malach R., Hendler T., Peled S., Zohary E. Visuo-haptic object-related activation in the ventral visual pathway. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:324. doi: 10.1038/85201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A., Raz N., Azulay H., Malach R., Zohary E. Cortical activity during tactile exploration of objects in blind and sighted humans. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2010;28:143–156. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A., Raz N., Pianka P., Malach R., Zohary E. Early 'visual' cortex activation correlates with superior verbal memory performance in the blind. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:758–766. doi: 10.1038/nn1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A., Stern W.M., Camprodon J.A., Bermpohl F., Merabet L., Rotman S., Hemond C., Meijer P., Pascual-Leone A. Shape conveyed by visual-to-auditory sensory substitution activates the lateral occipital complex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:687. doi: 10.1038/nn1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arno P., Volder A.G., De, Vanlierde A., Wanet-Defalque M.C., Streel E., Robert A., Sanabria-Bohórquez S., Veraart C. Occipital activation by pattern recognition in the early blind using auditory substitution for vision. Neuroimage. 2001;13:632–645. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer C., Yazzolino L., Hirsch G., Cattaneo Z., Vecchi T., Merabet L.B. Neural correlates associated with superior tactile symmetry perception in the early blind. Cortex. 2015;63:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavelier D., Neville H.J. Cross-modal plasticity: where and how? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:443. doi: 10.1038/nrn848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedny M., Konkle T., Pelphrey K., Saxe R., Pascual-Leone A. Sensitive period for a multimodal response in human visual motion area mt/mst. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1900–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedny M., Pascual-Leone A., Dodell-Feder D., Fedorenko E., Saxe R. Language processing in the occipital cortex of congenitally blind adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4429–4434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014818108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonino D., Ricciardi E., Bernardi G., Sani L., Gentili C., Vecchi T., Pietrini P. Spatial imagery relies on a sensory independent, though sensory sensitive, functional organization within the parietal cortex: a fMRI study of angle discrimination in sighted and congenitally blind individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2015;68:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst A.W.D., Gelder B.D. Mental imagery follows similar cortical reorganization as perception: intra-Modal and cross-modal plasticity in congenitally blind. Cereb Cortex. 2018;29(7):2859–2875. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchel C., Price C., Rs, Friston K. Different activation patterns in the visual cortex of late and congenitally blind subjects. Brain. 1998;121:409–419. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton H., Diamond J.B., McDermott K.B. Dissociating cortical regions activated by semantic and phonological tasks: a fmri study in blind and sighted people. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1965–1982. doi: 10.1152/jn.00279.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton H., Snyder A., Conturo T., Akbudak E., Ollinger J. Adaptive changes in early and late blind: a fMRI study of Braille reading. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:589–607. doi: 10.1152/jn.00285.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton H., Snyder A., Diamond J., Raichle M. Adaptive changes in early and late blind: a fmri study of verb generation to heard nouns. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3359–3371. doi: 10.1152/jn.00129.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C.C., Wong A.W., Ting K.H., Whitfield-Gabrieli S., He J., Lee T.M. Cross auditory-spatial learning in early-blind individuals. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:2714–2727. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee M.W.L., Caplan D., Soon C.S., Sriram N., Tan E.W.L., Thiel T., Weekes B. Processing of visually presented sentences in mandarin and english studied with fMRI. Neuron. 1999;23:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80759-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L.G., Celnik P., Pascual-Leone A., Corwell B., Faiz L., Dambrosia J., Honda M., Sadato N., Gerloff C., Catala M.D. Functional relevance of cross-modal plasticity in blind humans. Nature. 1997;389:180. doi: 10.1038/38278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L.G., Weeks R.A., Sadato N., Celnik P., Ishii K., Hallett M. Period of susceptibility for cross-modal plasticity in the blind. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:451–460. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199904)45:4<451::aid-ana6>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon O., Dormal G., Albouy G., Vandewalle G., Voss P., Phillips C., Lepore F. Impact of blindness onset on the functional organization and the connectivity of the occipital cortex. Brain. 2013;136:2769–2783. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon O., Dormal G., Lepore F. Building the brain in the dark: functional and specific crossmodal reorganization in the occipital cortex of blind individuals. Plasticity in sensory systems. 2012:114–137. [Google Scholar]

- Collignon O., Lassonde M., Lepore F., Bastien D., Veraart C. Functional cerebral reorganization for auditory spatial processing and auditory substitution of vision in early blind subjects. Cereb Cortex. 2006;17:457–465. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon O., Vandewalle G., Voss P., Albouy G., Charbonneau G., Lassonde M., Lepore F. Functional specialization for auditory-spatial processing in the occipital cortex of congenitally blind humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 2011:4435–4440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013928108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins D., Neelin P., Peters T., Evans A. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of mr volumetric data in standardized talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cona G., Scarpazza C. Where is the “where”in the brain? a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on spatial cognition. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:1867–1886. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornette L., Dupont P., Rosier A., Sunaert S., Van Hecke P., Michiels J., Mortelmans L., Orban G.A. Human brain regions involved in direction discrimination. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2749–2765. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Volder A.G., Toyama H., Kimura Y., Kiyosawa M., Nakano H., Vanlierde A., Wanet-Defalque M.C., Mishina M., Oda K., Ishiwata K. Auditory triggered mental imagery of shape involves visual association areas in early blind humans. Neuroimage. 2001;14:129–139. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande G., Hu X., Stilla R., Sathian K. Effective connectivity during haptic perception: a study using granger causality analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1807–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschlander A., Stephan T., Hufner K., Wagner J., Wiesmann M., Strupp M., Brandt T., Jahn K. Imagined locomotion in the blind: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2009;45:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormal G. Auditory motion in the sighted and blind: early visual deprivation triggers a large-scale imbalance between auditory and “visual” brain regions. Neuroimage. 2016;134:630–644. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormal G., Rezk M., Yakobov E., Lepore F., Collignon O. Auditory motion in the sighted and blind: early visual deprivation triggers a large-scale imbalance between auditory and “visual” brain regions. Neuroimage. 2016;134:630–644. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff S.B., Laird A.R., Grefkes C., Wang L.E., Zilles K., Fox P.T. Coordinate-based ale meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: a random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2907–2926. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff S.B., Nichols T.E., Laird A.R., Hoffstaedter F., Amunts K., Fox P.T., Bzdok D., Eickhoff C.R. Behavior, sensitivity, and power of activation likelihood estimation characterized by massive empirical simulation. Neuroimage. 2016;137:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah M.J., Levinson K.L., Klein K.L. Face perception and within-category discrimination in prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia. 1995;33:661–667. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00002-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg T.E., Schindler R.J., Ochoa E., Kwan P.C., Farah M.J. Associative visual agnosia and alexia without prosopagnosia. Cortex. 1994;30(3):395–491. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleman D.J., Van D.E. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb cortex. 1991;1:1–47. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.1-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon L., Schneider F.C., Siebner H.R., Paulson O.B., Kupers R., Ptito M. Activation of the hippocampal complex during tactile maze solving in congenitally blind subjects. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:1663–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizewski E.R., Gasser T., Greiff A., De, Boehm A., Forsting M. Cross-modal plasticity for sensory and motor activation patterns in blind subjects. Neuroimage. 2003;19:968–975. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gougoux F., Zatorre R.J., Lassonde M., Voss P., Lepore F. A functional neuroimaging study of sound localization: visual cortex activity predicts performance in early-blind individuals. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero A.C., Hidalgo Tobón S.S., Dies S.P., Barragán P.E., Castro S.E., García J., De C.A.B. Strategies for tonal and atonal musical interpretation in blind and normally sighted children: an fMRI study. Brain Behav. 2016;6:e00450. doi: 10.1002/brb3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halko M.A., Connors E.C., Jaime S., Merabet L.B. Real world navigation independence in the early blind correlates with differential brain activity associated with virtual navigation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:2768–2778. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R., Keenan J.P., Catala M., Pascual-Leone A. Alexia for braille following bilateral occipital stroke in an early blind woman. Neuroreport. 2000;11:237–240. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handjaras G., Ricciardi E., Leo A., Lenci A., Cecchetti L., Cosottini M., Marotta G., Pietrini P. How concepts are encoded in the human brain: a modality independent, category-based cortical organization of semantic knowledge. Neuroimage. 2016;135:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C., Peelen M.V., Han Z., Lin N., Caramazza A., Bi Y. Selectivity for large nonmanipulable objects in scene-selective visual cortex does not require visual experience. Neuroimage. 2013;79:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimler B., Striem-Amit E., Amedi A. Origins of task-specific sensory-independent organization in the visual and auditory brain: neuroscience evidence, open questions and clinical implications. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;35:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüfner K., Stephan T., Flanagin V.L., Deutschländer A., Stein A., Kalla R., Dera T., Fesl G., Jahn K., Strupp M. Differential effects of eyes open or closed in darkness on brain activation patterns in blind subjects. Neurosci Lett. 2009;466:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James T.W., Humphrey G.K., Gati J.S., Servos P., Menon R.S., Goodale M.A. Haptic study of three-dimensional objects activates extrastriate visual areas. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:1706–1714. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjlia S., Lane C., Feigenson L., Bedny M. Absence of visual experience modifies the neural basis of numerical thinking. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:11172–11177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524982113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katja F., Michael B., Siegfried B., Brigitte R.D., Frank R.S. The human dorsal action control system develops in the absence of vision. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:1–12. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.K., Zatorre R.J. Tactile-auditory shape learning engages the lateral occipital complex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7848–7856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3399-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Kanjlia S., Merabet L.B., Bedny M. Development of the visual word form area requires visual experience: evidence from blind braille readers. J Neurosci. 2017;37:11495–11504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0997-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada R., Okamoto Y., Sasaki A.T., Kochiyama T., Miyahara M., Lederman S.J., Sadato N. Early visual experience and the recognition of basic facial expressions: involvement of the middle temporal and inferior frontal gyri during haptic identification by the early blind. Front hum neurosci. 2013;7:7. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosslyn S.M. Mental images and the brain. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2005;22:333–347. doi: 10.1080/02643290442000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala T., Huotilainen M., Sinkkonen J., Ahonen A.I., Alho K., Hämälä M.S., Ilmoniemi R.J., Kajola M., Knuutila J.E., Lavikainen J. Visual cortex activation in blind humans during sound discrimination. Neurosci Lett. 1995;183:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)11135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupers R., Chebat D.R., Madsen K.H., Paulson O.B., Ptito M. Neural correlates of virtual route recognition in congenital blindness. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:12716–12721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006199107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupers R., Fumal A., De Noordhout A.M., Gjedde A., Schoenen J., Ptito M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the visual cortex induces somatotopically organized qualia in blind subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:13256–13260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602925103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupers R., Ptito M. Compensatory plasticity and cross-modal reorganization following early visual deprivation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;41:36–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey S., Sathian K. Representation of object form in vision and touch.the neural bases of multisensory. Processes,Chapter. 2012;10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird A.R., Fox P.M., Price C.J., Glahn D.C., Uecker A.M., Lancaster J.L., Turkeltaub P.E., Kochunov P., Fox P.T. ALE meta-analysis: controlling the false discovery rate and performing statistical contrasts. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25:155–164. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S., Sampaio E., Mauss Y., Scheiber C. Blindness and brain plasticity: contribution of mental imagery?: an fMRI study. Cognitive Brain Res. 2004;20:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster J.L., Martinez M., Salinas F., Evans A., Zilles K., Mazziotta J.C., Fox P.T. Bias between mni and talairach coordinates analyzed using the ICBM-152 brain template. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(11):1194–1205. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane C., Kanjlia S., Omaki A., Bedny M. "Visual" cortex of congenitally blind adults responds to syntactic movement. J Neurosci. 2015;35:12859–12868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1256-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo A., Bernardi G., Handjaras G., Bonino D., Ricciardi E., Pietrini P. Increased bold variability in the parietal cortex and enhanced parieto-occipital connectivity during tactile perception in congenitally blind individuals. Neural Plast. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/720278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J.W., Frum C., Brefczynski-Lewis J.A., Talkington W.J., Walker N.A., Rapuano K.M., Kovach A.L. Cortical network differences in the sighted versus early blind for recognition of human-produced action sounds. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:2241–2255. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotti M., Ryder K., Woldorff M.G. Auditory attention in the congenitally blind: where, when and what gets reorganized? Neuroreport. 1998;9:1007–1012. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Han S. Neural representation of self-concept in sighted and congenitally blind adults. Brain. 2010;134:235–246. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso E. Orienting of spatial attention and the interplay between the senses. Cortex. 2010;46:282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacSweeney M., Capek C.M., Campbell R., Woll B. The signing brain: the neurobiology of sign language. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K., Yasuda H., Haneda M., Kashiwagi A. Braille alexia during visual hallucination in a blind man with selective calcarine atrophy. Psychiat Clin Neuros. 2003;57:227–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon B.Z., Anzellotti S., Schwarzbach J., Zampini M., Caramazza A. Category-Specific organization in the human brain does not require visual experience. Neuron. 2009;63:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malach R., Reppas J., Benson R., Kwong K., Jiang H., Kennedy W., Ledden P., Brady T., Rosen B., Tootell R. Object-related activity revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging in human occipital cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:8135–8139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteau I., Kupers R., Ricciardi E., Pietrini P., Ptito M. Beyond visual, aural and haptic movement perception: hMT+ is activated by electrotactile motion stimulation of the tongue in sighted and in congenitally blind individuals. Brain Res Bull. 2010;82:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry R.I., Chen J.K., Witcher P., Klein D. Age of acquisition effects on the functional organization of language in the adult brain. Brain Lang. 2011;119:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry R.I., Kluender R. Rethinking the critical period for language: new insights into an old question from american sign language. Biling Language and Cogn. 2018;21:886–905. doi: 10.1017/S1366728917000724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merabet L.B., Lorella B., Souzana O., Sara M., Peter M., Alvaro P.L. Functional recruitment of visual cortex for sound encoded object identification in the blind. Neuroreport. 2009;20:132–138. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832104dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L.A., 2015. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews 4, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moscovitch M., Winocur G., Behrmann M. What is special about face recognition? nineteen experiments on a person with visual object agnosia and dyslexia but normal face recognition. J Cogn Neurosci. 1997;9:555–604. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller V.I., Cieslik E.C., Laird A.R., Fox P.T., Radua J., Mataix-Cols D., Tench C.R., Yarkoni T., Nichols T.E., Turkeltaub P.E. Ten simple rules for neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;84:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumer M.J., Doehrmann O., Müller N.G., Muckli L., Kaiser J., Hein G. Cortical plasticity of audio-visual object representations. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:1641. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmi F., Boccia M., Piccardi L., Galati G., Guariglia C. Segregation of neural circuits involved in spatial learning in reaching and navigational space. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:1561–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N., Amedi A., Zohary E. V1 activation in congenitally blind humans is associated with episodic retrieval. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1459. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre A.C., Coull J., Maquet P., Frith C., Vandenberghe R., Mesulam M. Orienting attention to locations in perceptual versus mental representations. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:363–373. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noppeney U., Friston K.J., Price C.J. Effects of visual deprivation on the organization of the semantic system. Brain. 2003;126:1620–1627. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofan R.H., Zohary E. Visual cortex activation in bilingual blind individuals during use of native and second language. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1249–1259. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.J., Chun J.W., Park B., Park H., Kim J.I., Lee J.D., Kim J.J. Activation of the occipital cortex and deactivation of the default mode network during working memory in the early blind. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:407–422. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A., Amedi A., Fregni F., Merabet L.B. The plastic human brain cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;28:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A., Hamilton R. Prog Brain Res. Elsevier; 2001. The metamodal organization of the brain; pp. 427–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier S., Stilla R., Mariola E., LaConte S., Hu X., Sathian K. Activity and effective connectivity of parietal and occipital cortical regions during haptic shape perception. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrini P., Furey M.L., Ricciardi E., Gobbini M.I., Wu W.H.C., Cohen L., Guazzelli M., Haxby J.V. Beyond sensory images: object-based representation in the human ventral pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5658–5663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400707101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietro P., Furey M.L., Emiliano R., M Ida G., W-H Carolyn W., Leonardo C., Mario G., Haxby J.V. Beyond sensory images: object-based representation in the human ventral pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5658–5663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400707101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishnamazi M., Nojaba Y., Ganjgahi H., Amousoltani A., Oghabian M.A. Neural correlates of audiotactile phonetic processing in early-blind readers: an fMRI study. Exp Brain Res. 2016;234:1263–1277. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M.I., Petersen S.E. The attention system of the human brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptito M., Matteau I., Gjedde A., Kupers R. Recruitment of the middle temporal area by tactile motion in congenital blindness. Neuroreport. 2009;20:543–547. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283279909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptito M., Matteau I., Wang A.Z., Paulson O.B., Siebner H.R., Kupers R. Crossmodal recruitment of the ventral visual stream in congenital blindness. Neural Plast. 2012;8 doi: 10.1155/2012/304045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptito M., Moesgaard S.M., Gjedde A., Kupers R. Cross-modal plasticity revealed by electrotactile stimulation of the tongue in the congenitally blind. Brain. 2005;128:606–614. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N., Amedi A., Zohary E. V1 activation in congenitally blind humans is associated with episodic retrieval. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1459–1468. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renier L., Cuevas I., Grandin C.B., Dricot L., Plaza P., Lerens E., Rombaux P., Volder A.G.D. Right occipital cortex activation correlates with superior odor processing performance in the early blind. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renier L., De Volder A.G., Rauschecker J.P. Cortical plasticity and preserved function in early blindness. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;41:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renier L.A., Anurova I., De Volder A.G., Carlson S., VanMeter J., Rauschecker J.P. Multisensory integration of sounds and vibrotactile stimuli in processing streams for “what” and “where”. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10950–10960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0910-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renier L.A., Irina A., Volder A.G., De, Synn?Ve C., John V.M., Rauschecker J.P. Preserved functional specialization for spatial processing in the middle occipital gyrus of the early blind. Neuron. 2010;68:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi E., Handjaras G., Pietrini P. The blind brain: how (lack of) vision shapes the morphological and functional architecture of the human brain. Exp Biol Med. 2014;239:1414–1420. doi: 10.1177/1535370214538740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi E., Tozzi L., Leo A., Pietrini P. Modality dependent cross-modal functional reorganization following congenital visual deprivation within occipital areas: a meta-analysis of tactile and auditory studies. Multisens Res. 2014;27:247. doi: 10.1163/22134808-00002454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röder B., Rösler F., Hennighausen E., Näcker F. Event-related potentials during auditory and somatosensory discrimination in sighted and blind human subjects. Cognitive Brain Res. 1996;4:77–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röder B., Stock O., Bien S., Neville H., Rösler F. Speech processing activates visual cortex in congenitally blind humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:930–936. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadato N., Pascual-Leone A., Grafman J., Deiber M.P., Ibanez V., Hallett M. Neural networks for braille reading by the blind. Brain. 1998;121:1213–1229. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.7.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadato N., Pascual-Leone A., Grafman J., Ibanez V., Deiber M.P., Dold G., Hallett M. Activation of the primary visual cortex by braille reading in blind subjects. Nature. 1996;380:526–528. doi: 10.1038/380526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathian K., Prather S. Cerebral cortical processing of tactile form: evidence from functional neuroimaging. Touch and blindness: Psychology and neuroscience. 2006:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sengpiel F., Kind P.C. The role of activity in development of the visual system. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R818–R826. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno M.I., Huang R.S. Multisensory maps in parietal cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;24:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigalov N., Maidenbaum S., Amedi A. Reading in the dark: neural correlates and cross-modal plasticity for learning to read entire words without visual experience. Neuropsychologia. 2016;83:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.K., Phillips F., Merabet L.B., Sinha P. Why does the cortex reorganize after sensory loss? Trends Cogn Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens A.A., Snodgrass M., Schwartz D., Weaver K. Preparatory activity in occipital cortex in early blind humans predicts auditory perceptual performance. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10734–10741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1669-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson R.A., James T.W. Audiovisual integration in human superior temporal sulcus: inverse effectiveness and the neural processing of speech and object recognition. Neuroimage. 2009;44:1210–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stilla R., Hanna R., Hu X., Mariola E., Deshpande G., Sathian K. Neural processing underlying tactile microspatial discrimination in the blind: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Vis. 2008;8:1–19. doi: 10.1167/8.10.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striem-Amit E., Amedi A. Visual cortex extrastriate body-selective area activation in congenitally blind people “seeing” by using sounds. Curr Biol. 2014;24:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striem-Amit E., Cohen L., Dehaene S., Amedi A. Reading with sounds: sensory substitution selectively activates the visual word form area in the blind. Neuron. 2012;76:640–652. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striem-Amit E., Dakwar O., Reich L., Amedi A. The large-scale organization of “visual” streams emerges without visual experience. Cereb Cortex. 2011;22:1698–1709. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach, J., Tournoux, P., 1988. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system: an approach to cerebral imaging.

- Tanja K., Corinna K., Cordula H.L., Menz M.M., Maurice P., Brigitte R.D., Siebner H.R. The left fusiform gyrus hosts trisensory representations of manipulable objects. Neuroimage. 2011;56:1566–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Q., Chan C.C.H., Luo Y.j., Li J.j., Ting K.h., Wang J., Lee T.M.C. How does experience modulate auditory spatial processing in individuals with blindness? Brain Topogr. 2015;28:506–519. doi: 10.1007/s10548-013-0339-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]