Summary

Background

Vaccinating infants with a first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) before 9 months of age in high-risk settings has the potential to reduce measles-related morbidity and mortality. However, there is concern that early vaccination might blunt the immune response to subsequent measles vaccine doses. We systematically reviewed the available evidence on the effect of MCV1 administration to infants younger than 9 months on their immune responses to subsequent MCV doses.

Methods

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched for randomised and quasi-randomised controlled trials, outbreak investigations, and cohort and case-control studies without restriction on publication dates, in which MCV1 was administered to infants younger than 9 months. We did the literature search on June 2, 2015, and updated it on Jan 14, 2019. We included studies reporting data on strength or duration of humoral and cellular immune responses, and on vaccine efficacy or vaccine effectiveness after two-dose or three-dose MCV schedules. Our outcome measures were proportion of seropositive infants, geometric mean titre, vaccine efficacy, vaccine effectiveness, antibody avidity index, and T-cell stimulation index. We used random-effects meta-analysis to derive pooled estimates of the outcomes, where appropriate. We assessed the methodological quality of included studies using Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines.

Findings

Our search retrieved 1156 records and 85 were excluded due to duplication. 1071 records were screened for eligibility, of which 351 were eligible for full-text screening and 21 were eligible for inclusion in the review. From 13 studies, the pooled proportion of infants seropositive after two MCV doses, with MCV1 administered before 9 months of age, was 98% (95% CI 96–99; I2=79·8%, p<0·0001), which was not significantly different from seropositivity after a two-dose MCV schedule starting later (p=0·087). Only one of four studies found geometric mean titres after MCV2 administration to be significantly lower when MCV1 was administered before 9 months of age than at 9 months of age or later. There was insufficient evidence to determine an effect of age at MCV1 administration on antibody avidity. The pooled vaccine effectiveness estimate derived from two studies of a two-dose MCV schedule with MCV1 vaccination before 9 months of age was 95% (95% CI 89–100; I2=12·6%, p=0·29). Seven studies reporting on measles virus-specific cellular immune responses found that T-cell responses and T-cell memory were sustained, irrespective of the age of MCV1 administration. Overall, the quality of evidence was moderate to very low.

Interpretation

Our findings suggest that administering MCV1 to infants younger than 9 months followed by additional MCV doses results in high seropositivity, vaccine effectiveness, and T-cell responses, which are independent of the age at MCV1, supporting the vaccination of very young infants in high-risk settings. However, we also found some evidence that MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months resulted in lower antibody titres after one or two subsequent doses of MCV than when measles vaccination is started at age 9 months or older. The clinical and public-health relevance of this immunity blunting effect are uncertain.

Funding

WHO.

Introduction

Although five of the six WHO regions have committed to eliminate measles by 2020, this disease remains endemic in many countries, mainly because of low or suboptimal vaccination coverage.1, 2 Protecting infants against measles can be achieved by ensuring high coverage with two doses of a measles-containing vaccine (MCV). WHO recommends that the first dose of MCV (MCV1) should be given at 9 or 12 months of age, depending on the level of measles virus transmission, with early administration appropriate for settings where transmission is high.3

Globally, infants who are too young to receive MCV1 as recommended by their national immunisation schedule remain at high risk of contracting measles.2, 4, 5 A surveillance study2 suggested that 12% of all measles cases reported to the WHO between 2013 and 2017 were in infants who were too young to be vaccinated. This proportion is particularly concerning because measles in infants is more likely to lead to complications and death than in school-aged children.6 The proportion of measles cases in infants is likely to increase, given that an increasing number of mothers have vaccine-induced measles immunity, and their children have lower concentrations of maternal measles antibodies than children of naturally immune mothers.7, 8

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Vaccination with a measles-containing vaccine (MCV) before 9 months of age has the potential to improve measles prevention in young infants, who are most vulnerable to the disease's potentially devastating effects. However, some evidence on the age-specific effects of administering the first dose of a MCV (MCV1) to infants younger than 9 months suggests that its immunogenicity can be suboptimal, and subsequent MCV doses might not entirely compensate for this effect. Evidence of immunity blunting after a two-dose schedule starting before 9 months of age is essential to help to guide policy on measles vaccination. We, therefore, addressed this question in our systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the immunogenicity and effectiveness of two-dose or three-dose MCV schedules, with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, our study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to examine if MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months blunts the immune response to subsequent doses of MCV. We found that administering MCV1 at this age, followed by additional vaccine doses at later ages, results in high seropositivity and vaccine effectiveness. Additionally, we found that the T-cell memory response was independent of the age of MCV1 administration. Some evidence suggests that MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months results in lower geometric mean titres after one or two subsequent doses than after a measles vaccination schedule starting at an older age.

Implications of all the available evidence

MCV1 administration to infants younger than 9 months, followed by a subsequent dose of MCV, elicited a good immune response to support this practice in high-risk settings. We found some evidence on blunting of the immune response in terms of geometric mean titres but the relevance of this finding to public health is unclear. Our results underline the importance of providing additional MCV doses to infants who have been vaccinated with MCV1 when they were younger than 9 months. Findings from our review informed WHO policy recommendations on the optimal timing of MCV1 and could help countries in their decision making if they consider offering MCVs to infants younger than 9 months.

Vaccinating young infants with a MCV between 6 and 9 months of age could reduce measles-related morbidity and mortality, and is recommended in high-risk areas, such as those with measles outbreaks.3 However, debates on the optimal age for MCV1 administration and the advantages and disadvantages of early MCV doses have been ongoing since measles vaccines were developed in the 1960s.9, 10, 11, 12

The optimal timing for MCV1 administration depends on the age at which infants have a sufficiently mature immune system to respond to a MCV, the age at which infants are at risk of infection, and the age when maternal antibodies no longer have an inhibitory effect on the immunogenicity of MCV.8, 13, 14 The optimal timing also depends on the objectives of national immunisation programmes and their progress towards measles elimination.

In our accompanying systematic review,15 we studied the effects of administering MCV1 to infants younger than 9 months in terms of immunogenicity, vaccine effectiveness, and safety. We found that administration of MCV1 between 6 and 9 months of age is safe and immunogenic. However, higher seroconversion and protection were seen in infants who received MCV1 at older ages.

A potential concern relating to the administration of MCV1 to infants younger than 9 months is whether their immune response is then blunted to subsequent MCV doses. Two reviews published almost three decades ago16, 17 suggested that measles vaccination early in infancy impaired responses to subsequent MCV doses, compared with MCV1 administration at an older age.18 This impairment is thought to be due to the presence of maternally derived neutralising antibodies, leading to suboptimal priming of the subsequent vaccine response. This effect differs from immunological tolerance or hyporesponsiveness reported for polysaccharide vaccines, in which antibody concentrations after a second antigenic challenge are lower than after the first.19

We did a systematic review and meta-analyses to assess whether MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months is associated with blunting of the immune response to subsequent MCV doses by examining immunogenicity, duration of immunity, and vaccine effectiveness.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Our search strategy for this systematic review and meta-analysis consisted of four components: a library database search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Proquest, and Global Health; a search of the WHO library database (WHOLIS) and the WHO Institutional Repository for Information Sharing database (IRIS); consulting the Working Group on Measles and Rubella from WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization in September 2015; and screening bibliographies of included articles and five key reviews.13, 14, 20, 21, 22 Additional references found in this way were subject to the same screening and selection process as articles found in the primary search. The results were restricted to articles in English, Dutch, German, French, and Spanish. We did not set any time limit to dates of published articles included in our search. We did the literature search on June 2, 2015, and updated it on Jan 14, 2019.

We developed search terms for each database using controlled vocabulary (appendix pp 2–7) to capture publications on the effects and safety of MCV1 in infants younger than 9 months. The first dose of MCV given earlier than the recommended age is often referred to as MCV0, implying that two subsequent MCV doses are needed for optimal protection. Here, we refer to all first MCV doses as MCV1 and do not make any assumptions about the total number of doses needed for optimal protection. We searched for randomised and quasi-randomised controlled trials, outbreak investigations, and cohort and case-control studies reporting summary estimates or, where unavailable, patient-level data on humoral and cellular immunogenicity, vaccine efficacy or vaccine effectiveness, and duration of protection of two-dose or three-dose MCV schedules with MCV1 administration before 9 months of age. When available, we also extracted data for the comparator group from included articles that reported MCV1 administration to infants aged 9 months and older. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria or study type and those that reported vaccines with non-standard high viral titres were excluded. A complete list of the exclusion and inclusion criteria is available in the appendix (p 8).

After deleting duplicate studies, two reviewers selected 10% of the retrieved articles at random and independently reviewed the title and abstract according to the predefined set of inclusion criteria. The application of the inclusion criteria was consistent (≤10% disagreement between the two reviewers), indicating high concordance.23 The reviewers divided the remaining articles to continue the title and abstract screening separately. This selection process was also applied to the full-text screening of included articles (≤10% disagreement). In case of uncertainty about inclusion or exclusion, the reviewers consulted each other. Discrepancies during the selection process were resolved by a third reviewer.

We report our systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.24

Data analysis

We considered the following outcome measures: the proportion of seropositive infants, geometric mean titre, duration of immunity, vaccine efficacy, and vaccine effectiveness, avidity index, and T-cell stimulation index after MCV2 or MCV3 by age of administration of MCV1. For vaccine efficacy, per-protocol results were used.

The included articles were divided among four reviewers who extracted study characteristics and outcomes using a pre-defined form. The form included 128 fields to capture data relating to the author, study year, type of study, country, study population, vaccine type, vaccine titre, test used, test definitions, summary estimates, 95% CIs, and SEs, among others. Data in all forms where checked by at least two reviewers against the original publication, and subsequently entered into a Microsoft Access database.

We used the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines25 to assess the methodological quality of included studies. We used eight indicators to assess risk of bias within and between studies: (1) representativeness, (2) attrition bias, (3) reporting bias, (4) laboratory confirmation of measles infection, (5) confirmation of vaccination status, (6) comparability of control group with vaccinated group, (7) time between vaccination and sampling, and (8) study design. These study characteristics were reviewed per outcome by four reviewers using Review Manager 5.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre; Copenhagen, Denmark) and entered into GRADE evidence summary forms.

Where possible, results were stratified by age at administration of MCV in months. Where sufficient data were available, results were pooled by meta-analyses. We examined heterogeneity between results of different studies in forest plots and using the I2 statistic to estimate the percentage of the total variation due to between-study variation.26

We included immunogenicity data derived from testing venous and capillary blood samples collected in tubes, with a minimum of 4 weeks between vaccination and blood sampling. We included studies reporting seropositivity as measured by ELISA, haemagglutination inhibition, and plaque reduction neutralisation test (PRNT). We used random-effects meta-analyses to calculate pooled estimates, where appropriate. For studies presenting outcomes of MCV2 when MCV1 was administered to infants younger than 9 months and to a comparison group of infants aged at least 9 months (ie, within-study comparisons) we used meta-analysis to estimate the difference in the proportion of infants who were seropositive between these schedules.

We examined the effect of an early MCV1 on the geometric mean titres after a two-dose or three-dose MCV schedule using results from within-study comparisons. To be included in this analysis, the time between vaccination and sampling had to be similar between the two comparison groups. For duration of immunity, we reviewed studies reporting geometric mean titres at several consecutive follow-up timepoints after vaccination.

We reviewed vaccine efficacy or vaccine effectiveness after a two-dose MCV schedule with MCV administered to infants younger than 9 months.

For antibody avidity and cellular immunity, we only assessed within-study comparisons. Studies reporting the T-cell stimulation index, which is the ratio of mean T-cell proliferation counts per minute in antigen wells divided by the mean counts per minute in corresponding control wells, considered a stimulation index of 3·0 or greater as positive.

We used Stata 15.0 statistical software (StataCorp 2017 Release 15; College Station, TX, USA) for all analyses.

Role of the funding source

PMS and TG are employees of the funder of the study and participated in data interpretation and writing of the report. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, and data analysis. All authors had full access to the study data, and the analysis, interpretation, and the decision to publish was solely the responsibility of the authors.

Results

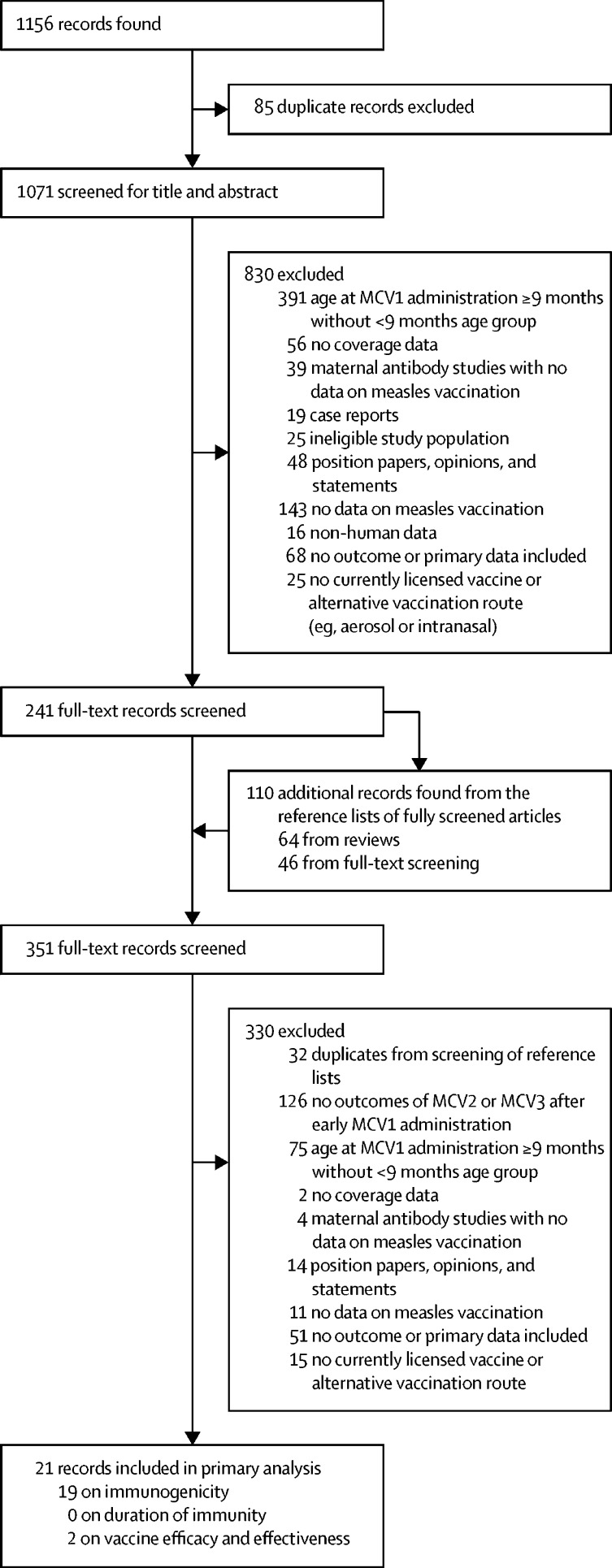

Our search retrieved 1156 records, of which 85 were duplicates and were excluded. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 1071 articles were screened and 241 met the inclusion criteria and were assessed for eligibility via full-text screening (figure 1). 110 additional publications were found through screening the bibliographies of the assessed full-text articles. 330 records in total did not meet the inclusion criteria after a second review. Data from the remaining 21 studies reported outcomes related to blunted immune responses to subsequent MCV doses after MCV1 administration to infants younger than 9 months and were included in the analysis. 19 articles reported relevant information on immunogenicity, there were no reports on duration of immunity, and two articles reported on vaccine efficacy to subsequent MCV doses (appendix pp 9–10).

Figure 1.

Study profile

Some of the 21 records included in the primary analysis had data on more than one outcome. MCV=measles-containing vaccine. MCV1=first dose of measles-containing vaccine.

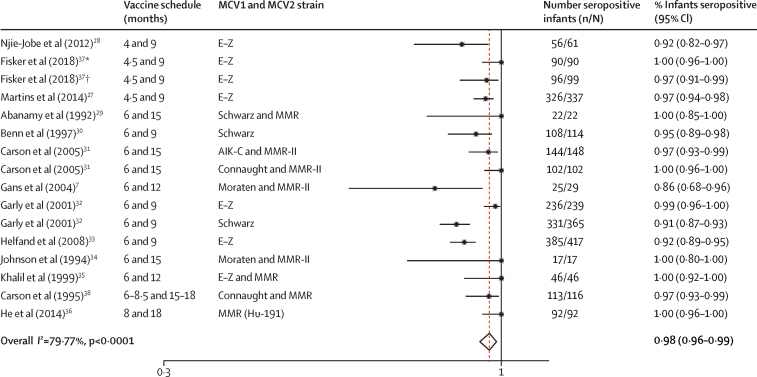

On the basis of the 13 articles7, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 that reported proportions of infants who were seropositive after a two-dose MCV schedule, in which MCV1 was administered before 9 months of age, the pooled proportion of seropositive infants after MCV2 was 98% (95% CI 96–99; figure 2). Five studies7, 27, 28, 36, 39 were meta-analysed for within-study comparisons of the proportion of infants seropositive after MCV2 administration, with MCV1 administered before 9 months of age, with control groups vaccinated at age 9 months or later. The analysis showed a non-significant pooled estimated difference of 4% fewer seropositive infants (95% CI −1 to 9, p=0·087) after vaccination with MCV1 before 9 months of age than control groups vaccinated at age 9 months and older (table 1, appendix p 11).

Figure 2.

Random-effects meta-analysis of the proportion of infants vaccinated with MCV1 before 9 months of age who were seropositive after MCV2 administration

Where multiple estimates are presented per publication, these represent subgroups. E-Z=Edmonston-Zagreb. MMR=measles-mumps-rubella. *Burkina Faso population. †Guinea-Bissau population.

Table 1.

Within-study comparisons between different MCV schedules of the proportion of infants seropositive after a two-dose schedule with MCV1 administered before or after 9 months of age

| Infants seropositive after two MCV doses | |

|---|---|

| Gans et al (2004)7* | |

| 6 and 12 months | 86% (68–96) |

| 9 and 12 months | 90% (70–99) |

| He et al (2014)36† | |

| 8 and 18 months | 100% (96–100) |

| 12 and 22 months | 100% (97–100) |

| Martins et al (2014)27‡ | |

| 4·5 and 9 months | 97% (94–98) |

| 9 and 18 months | 98% (95–100) |

| Njie-Jobe et al (2012)28‡ | |

| 4 and 9 months | 92% (82–97) |

| 9 and 36 months | 100% (92–100) |

| Fowlkes et al (2016)39‡ | |

| 6 and 9 months | 90% (85–93) |

| 9 and 20 months | 99% (93–100) |

Data are % (95% CI). MCV=measles-containing vaccine. MMR=measles-mumps-rubella.

The MCV1 strain was Moraten and MCV2 was MMR-II.

Both MCV1 and MCV2 were the MMR (Hu-191) strain.

Both MCV1 and MCV2 were the Edmonston-Zagreb strain.

Five studies7, 28, 36, 39, 40 reported geometric mean titres after a two-dose or three-dose MCV schedule, with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months and a control group of infants aged 9 months and older. Two of these studies7, 40 reported on the same cohort of infants. Four studies7, 28, 36, 39 reported geometric mean titres after MCV2 vaccination when MCV1 was administered before 9 months of age compared with administration to older infants. All four studies showed lower geometric mean titres after MCV2 administration for the MCV1 schedule starting before 9 months of age than in schedules starting at 9 months or later. However, this difference was significant in only one of these studies (table 2).39 On the basis of one study,40 geometric mean titres after MCV3 administration were not significantly different between MCV1 schedules starting before 9 months of age and those starting at 9 months or later. When considering only children who had no maternal antibodies at the time of MCV1 vaccination, significant differences were seen between the two age groups (335 mIU/mL, 95% CI 211–531 after MCV3 with MCV1 given at 6 months of age; 1080 mIU/mL, 95% CI 642–1827 after MCV3 with MCV1 at 9 months of age).

Table 2.

Vaccine schedules with reported GMTs after MCV2 and MCV3 administration in infants vaccinated with MCV1 before 9 months of age or later

|

Measles antibody titres after MCV2 |

Measles antibody titres after MCV3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMT in mIU/mL (95% CI) | Time between MCV2 and sampling | GMT in mIU/mL (95% CI) | Time between MCV3 and sampling | |

| Gans et al (2004)7and Gans et al (2013),40 | ||||

| 6 months, 12 months, 5 years | 702 (344–1457) | 24 weeks | 199 (110–361) | 0–5 years |

| 9 months, 12 months, 5 years | 1546 (686–3484) | 24 weeks | 419 (254–690) | 0–5 years |

| He et al (2014)36 | ||||

| 8 and 18 months | 3080 (2790–3400) | 30–35 days | .. | .. |

| 12 and 22 months | 3199 (2940–3480) | 30–35 days | .. | .. |

| Nije-Jobe et al (2012)28 | ||||

| 4, 9, and 36 months | 7 (4·75–8·25)* | 2 weeks | 9 (8–9)* | 2 weeks |

| 9 and 36 months | 9 (8–10)* | 2 weeks | .. | .. |

| Fowlkes et al (2016)39 | ||||

| 6, 9, and 20 months | 395·4 (347–455) | Median 11 months (IQR 9·5–14·6) | 561·2 (469–679) | 9–12 months |

| 9 and 20 months | 601·8 (503–721) | 9–12 months | .. | .. |

GMT=geometric mean titre. MCV=measles-containing vaccine.

Median and interquartile range of log2 haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody titres.

Two articles reported results on antibody avidity40, 41 after two or three doses of MCV with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months. These results were derived from the same cohort of infants at different follow-up times and times between vaccination and avidity index testing. A 2007 study,41 with 13–27 individuals per group, reported the comparison between three MCV schedules (6 and 12 months, 9 and 12 months, and 12 months only). For the two-dose schedule starting at 6 months of age, the median avidity index significantly increased after the second dose. The median avidity index after MCV2 was lower in the group who received MCV1 at 9 months than the group who received MCV1 at 6 months, but a significance measure was not reported for this comparison.

The 2013 study40 reported a comparison of the three MCV schedules with a subsequent dose at 5 years of age and a follow-up period of up to 10 years of age. The three schedules that were compared were two three-dose schedules (at 6 months, 12 months, and 5 years of age, and 9 months, 12 months, and 5 years of age) and one two-dose schedule (at 12 months and 5 years of age). The mean avidity index at age 5–10 years after three doses of MCV was lower when MCV1 was administered at 6 months of age (mean avidity index 1·4) than at 9 months (1·7) or 12 months (2·2), but the study did not report whether this difference was significant.

No studies were found that describe the duration of immunity after vaccination with MCV2 when MCV1 was administered to infants younger than 9 months. One study28 reported geometric mean titres 12 months after the last MCV dose, comparing an early three-dose MCV schedule (vaccination at 4 months, 9 months, and 36 months) with a regular two-dose MCV schedule (vaccination at 9 months and 36 months). The geometric mean titre in the early three-dose schedule was significantly lower than the geometric mean titre after the two-dose schedule (6 vs 7 log2 antibody titres, p<0·0001).

Seven studies reported cellular immune responses specific for measles virus after two or three MCV doses, with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months.7, 28, 31, 40, 42, 43, 44 One of these31 compared results in infants vaccinated at age 6 months with MCV containing either the AIK-C or Connaught strains and after measles-mumps-rubella vaccination at 15 months of age in both groups. 210 (70%) of 300 infants included in the study developed evidence of measles virus-specific T-cell responses after two doses of MCV. Since there was no control group in which MCV1 was administered at 9 months of age and older, this result is difficult to interpret.

Five consecutive studies on cell-mediated immunity by Gans and colleagues of the same cohort of infants7, 40, 42, 43, 44 found that the development of measles virus-specific T-cell responses after two or three MCV doses was independent of the age of MCV1 administration.40, 42 In the most recent follow-up study,40 in children aged 5–10 years who had received three MCV doses, the mean cell stimulation index was 11·4 (SE 1·3) in those who received MCV1 at 6 months of age and 10·9 (1·5) in those who received it at 9 months of age. The presence of maternal measles antibodies at the time of MCV1 administration had no effect on the mean stimulation index. Another study28 reported on memory T-cell responses after either a three-dose MCV schedule at 4 months, 9 months, and 36 months, or a two-dose schedule at 9 months and 36 months. No significant differences in measles-specific effector-cell or T-cell memory responses were found between the study groups up to 48 months of age.28

Two studies reported vaccine effectiveness after a two-dose MCV schedule with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months.45, 46 In one study,45 vaccine effectiveness was 93% (95% CI 86–97) up to the age of 5 years for a two-dose schedule with MCV1 administered at 6–8 months and MCV2 at 9 months of age. In the other study,46 during a measles outbreak in school-aged children, of 218 students who had received two MCV doses, 15 were vaccinated with MCV1 before 9 months of age and MCV2 at 15 months of age or later. None of these 15 students developed measles; therefore, the vaccine effectiveness was 100% (78–100).46 The pooled vaccine effectiveness of these two studies for a two-dose schedule with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months was 95% (89–100; I2=12·6%, p=0·29).

For immunogenicity outcomes (seropositivity, antibody avidity, and cellular immunity) after a two-dose MCV schedule with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months, we graded the quality of evidence for nine observational studies as very low, whereas the quality of evidence for ten randomised controlled trials was moderate. No studies were found reporting duration of immunity. We graded the quality of evidence from two observational studies with outcomes on vaccine effectiveness after a two-dose MCV schedule with MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months as very low. We found no randomised controlled trials reporting on vaccine efficacy. Overall, when rating the importance of outcomes, they were deemed important for decision-making and evidence was of moderate to very low quality (appendix p 12).

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first systematic review to examine the effect of MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months on the immunogenicity and vaccine effectiveness of subsequent MCV doses. We reviewed evidence of humoral and cellular immunity, including seropositivity, geometric mean titres, avidity, T-cell stimulation, and vaccine effectiveness. We found high seropositivity (98%) and vaccine effectiveness (95%) after a two-dose MCV schedule starting before 9 months of age, with no evidence of lesser protection, than after a two-dose MCV schedule starting at 9 months of age or later. Our pooled estimate for vaccine effectiveness for an early two-dose MCV schedule was similar to that found in a review47 of two doses of MCV, with MCV1 administered to infants aged 9 months and older (94%, IQR 88–98). We found no evidence of reduced measles virus-specific cellular immune responses in children who received an early dose of MCV1.

There were differences, however, in antibody titres. After administration of MCV2, geometric mean titres were lower in children who had received MCV1 before the age of 9 months than those who were vaccinated with MCV1 at age 9 months in all four studies with available data,7, 28, 36, 39 although this finding was significant in only one of these studies.39 The only studies we found that reported on antibody avidity,40, 41 in which the same group of infants was assessed repeatedly, did not report on the significance of the observed differences between those receiving MCV1 below and above 9 months of age.

Considering that WHO recommendations advise that when MCV is given to infants younger than 9 months in high-risk settings the first dose should be followed by two subsequent MCV doses,3 it is also relevant to compare the immunogenicity of a three-dose MCV schedule starting before 9 months of age with a regular two-dose MCV schedule starting at 9 months of age or later. We found no differences in seropositivity, cellular immunity, and antibody titres following an early three-dose MCV schedule.28, 40

Taken together, our results suggest that the suboptimal humoral response to MCV1 when administered before 9 months of age, as we report in our accompanying systematic review,15 is corrected by subsequent doses when considering seropositivity, vaccine effectiveness, and cellular immunity. However, MCV1 administered to infants younger than 9 months might negatively influence measles-specific antibody titres and duration of immunity after subsequent MCV doses, compared with MCV1 administered to infants aged 9 months and later. A subtle blunting effect was also found in studies comparing two-dose MCV schedules starting around 12 months of age with those starting later.48, 49 The immunological basis for such a blunting effect is unknown.

The strengths of our study include the systematic review strategy and broad search terms to identify studies in multiple databases and languages. We used rigorous methods to extract and appraise data. However, we encountered several methodological limitations. Studies that could be used for specific outcome indicators were scarce and studies often had small sample sizes. For instance, our pooled estimate of vaccine effectiveness after a two-dose schedule with an early MCV1 was based on only two studies, which included short follow-up times for some participants. This paucity of data limits the robustness of our conclusions. Several studies identified through our systematic review reported results for MCV1 and MCV2 vaccination in broad age groups, rather than by age in months at the time of vaccination, and could therefore not be included. The low number of relevant studies was disappointing particularly considering a 1993 report by Rosenthal and Clements,17 suggesting that further research into measles vaccines should include randomised controlled trials of early two-dose MCV schedules, to investigate both technical and epidemiological issues such as the effect of blunting immunity and the duration of antibody persistence. Furthermore, heterogeneities in several factors made comparisons across studies challenging, including the vaccine strain used, the time between vaccine administration and measurement of antibody or cellular immune responses, and the assays used to measure the immune responses. Overall, we found the evidence of included studies to be of very low or moderate quality because of the paucity of studies, small population sizes, or insufficient methodological information. However, when prioritising the outcomes according to the GRADE assessment, we determined them to be important for decision-making.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that administering MCV1 to infants younger than 9 months, followed by one or two subsequent MCV doses, results in high seropositivity and high vaccine effectiveness. We did not find evidence of blunting of the immune response using these indicators. Also, T-cell responses after subsequent MCV doses were independent of the age of administration of MCV1. In the context of high measles incidence, for example during an outbreak, these findings support the recommendation to provide early protection to infants by administering MCV1 from 6 months of age.3 However, our review also found some, albeit scant, evidence of a blunting effect of an early MCV1 on measles-specific antibody titres after subsequent MCV doses. The clinical and public health relevance of this finding are uncertain, since evidence was scarce and studies with long follow-up periods were not found. These findings suggest that in elimination settings, where there is no need for early measles protection, starting MCV vaccination at 12 months at the earliest might be optimal. However, further research is needed into the best age of MCV1 administration in areas of medium incidence, which will depend on assumptions of progress on measles elimination and evidence derived from long-term follow up of infants vaccinated at different ages.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for their contribution: Felicity Cutts, Rik de Swart, and Members of WHO's SAGE Working Group on Measles and Rubella. We would also like to thank Wim ten Have and Joost de Gorter for doing the literature search, Janneke van Heereveld and Jeroen Alblas for their help with development of our database, and Iris Brinkman for help with literature screening. Our study was presented in part at WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization meeting (Geneva, Switzerland) on Oct 20–22, 2015, and at the 10th European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health (Antwerp, Belgium) on Oct 16–20, 2017.

Contributors

LMN and SJMH designed the study. LMN, NvdM, SJMH, and BdG reviewed the literature, extracted the data, and checked the extracted data. BdG, LMN, and SJMH planned the analysis, maintained the database, and did the analysis. All authors contributed intellectually to the work.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Dabbagh A, Laws RL, Steulet C. Progress toward regional measles elimination—worldwide, 2000–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1323–1329. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6747a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel MK, Orenstein WA. Classification of global measles cases in 2013–17 as due to policy or vaccination failure: a retrospective review of global surveillance data. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e313–e320. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Measles vaccines: WHO position paper—April 2017. Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92:205–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gans HA, Maldonado YA. Loss of passively acquired maternal antibodies in highly vaccinated populations: an emerging need to define the ontogeny of infant immune responses. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1–3. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Measles vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:349–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gans HA, Yasukawa LL, Alderson A. Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to an early 2-dose measles vaccination regimen in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:83–90. doi: 10.1086/421032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waaijenborg S, Hahne SJ, Mollema L. Waning of maternal antibodies against measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in communities with contrasting vaccination coverage. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:10–16. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YL, Black FL, Chen CL, Wu CL, Berman LL. The optimal age for vaccination against measles in an Asiatic city, Taipei, Taiwan: reduction of vaccine induced titre by residual transplacental antibody. Int J Epidemiol. 1983;12:340–343. doi: 10.1093/ije/12.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogunmekan DA, Harry TO. Optimal age for vaccinating Nigerian children against measles. II. Seroconversion to measles vaccine in different age groups. Trop Geogr Med. 1981;33:379–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanetta RA, Amaku M, Azevedo RS, Zanetta DM, Burattini MN, Massad E. Optimal age for vaccination against measles in the State of Sao Paulo, Brazil, taking into account the mother’s serostatus. Vaccine. 2001;20:226–234. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orenstein WA, Markowitz L, Preblud SR, Hinman AR, Tomasi A, Bart KJ. Appropriate age for measles vaccination in the United States. Dev Biol Stand. 1986;65:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strebel PM, Papania MJ, Parker Fiebelkorn A, Halsey NA. Measles vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit P, editors. Vaccines. 6th. Elsevier Saunders; 2012. p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cutts FT, Grabowsky M, Markowitz LE. The effect of dose and strain of live attenuated measles vaccines on serological responses in young infants. Biologicals. 1995;23:95–106. doi: 10.1016/1045-1056(95)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nic Lochlainn LM, de Gier B, van der Maas N. Immunogenicity, effectiveness, and safety of measles vaccination in infants younger than 9 months: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30395-0. published online Sept 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black FL. Measles active and passive immunity in a worldwide perspective. Prog Med Virol. 1989;36:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal SR, Clements CJ. Two-dose measles vaccination schedules. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:421–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Serres G, Boulianne N, Ratnam S, Corriveau A. Effectiveness of vaccination at 6 to 11 months of age during an outbreak of measles. Pediatrics. 1996;97:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Additional summaries of information related to WHO position papers on pneumococcus. https://www.who.int/immunization/PPV23_Additional_summary_Duration_protection_revaccination.pdf?ua=1

- 20.Gans HA. The status of live viral vaccination in early life. Vaccine. 2013;31:2531–2537. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markowitz L. Measles control in 1990s: immunization before 9 months of age. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss WJ, Scott S. WHO Immunological Basis for Immunization series module xx: measles. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins C, Garly ML, Bale C. Measles virus antibody responses in children randomly assigned to receive standard-titer edmonston-zagreb measles vaccine at 4·5 and 9 months of age, 9 months of age, or 9 and 18 months of age. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:693–700. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Njie-Jobe J, Nyamweya S, Miles DJ. Immunological impact of an additional early measles vaccine in Gambian children: responses to a boost at 3 years. Vaccine. 2012;30:2543–2550. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abanamy A, Khalil M, Salman H, Abdel Azeem M. Vaccination of Saudi children against measles with Edmonston-Zagreb. Ann Saudi Med. 1992;12:110–111. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1992.110a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benn CS, Aaby P, Bale C. Randomised trial of effect of vitamin A supplementation on antibody response to measles vaccine in Guinea-Bissau, west Africa. Lancet. 1997;350:101–105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)12019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carson MM, Spady DW, Beeler JA, Krezolek MP, Audet S, Pabst HF. Follow-up of infants given measles vaccine at 6 months of age: antibody and CMI responses to MMRII at 15 months of age and antibody levels at 27 months of age. Vaccine. 2005;23:3247–3255. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garly ML, Bale C, Martins CL. Measles antibody responses after early two dose trials in Guinea-Bissau with Edmonston-Zagreb and Schwarz standard-titre measles vaccine: better antibody increase from booster dose of the Edmonston-Zagreb vaccine. Vaccine. 2001;19:1951–1959. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helfand RF, Witte D, Fowlkes A. Evaluation of the immune response to a 2-dose measles vaccination schedule administered at 6 and 9 months of age to HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1457–1465. doi: 10.1086/592756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson CE, Nalin DR, Chui LW, Whitwell J, Marusyk RG, Kumar ML. Measles vaccine immunogenicity in 6- versus 15-month-old infants born to mothers in the measles vaccine era. Pediatrics. 1994;93:939–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalil M, Poltera AA, al-Howasi M. Response to measles revaccination among toddlers in Saudi Arabia by the use of two different trivalent measles-mumps-rubella vaccines. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:214–219. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He H, Chen E, Chen H. Similar immunogenicity of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine administrated at 8 months versus 12 months age in children. Vaccine. 2014;32:4001–4005. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisker AB, Nebie E, Schoeps A. A two-center randomized trial of an additional early dose of measles vaccine: effects on mortality and measles antibody levels. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1573–1580. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carson MM, Spady DW, Albrecht P. Measles vaccination of infants in a well-vaccinated population. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:17–22. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fowlkes AL, Witte D, Beeler J. Supplemental measles vaccine antibody response among HIV-infected and -uninfected children in Malawi after 1- and 2-dose primary measles vaccination schedules. Vaccine. 2016;34:1459–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gans HA, Yasukawa LL, Sung P. Measles humoral and cell-mediated immunity in children aged 5–10 years after primary measles immunization administered at 6 or 9 months of age. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:574–582. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nair N, Gans H, Lew-Yasukawa L, Long-Wagar AC, Arvin A, Griffin DE. Age-dependent differences in IgG isotype and avidity induced by measles vaccine received during the first year of life. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1339–1345. doi: 10.1086/522519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gans H, DeHovitz R, Forghani B, Beeler J, Maldonado Y, Arvin AM. Measles and mumps vaccination as a model to investigate the developing immune system: passive and active immunity during the first year of life. Vaccine. 2003;21:3398–3405. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gans H, Yasukawa L, Rinki M. Immune responses to measles and mumps vaccination of infants at 6, 9, and 12 months. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:817–826. doi: 10.1086/323346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gans HA, Maldonado Y, Yasukawa LL. IL-12, IFN-gamma, and T cell proliferation to measles in immunized infants. J Immunol. 1999;162:5569–5575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaninda AV, Legros D, Jataou IM. Measles vaccine effectiveness in standard and early immunization strategies, Niger, 1995. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:1034–1039. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199811000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis RM, Whitman ED, Orenstein WA, Preblud SR, Markowitz LE, Hinman AR. A persistent outbreak of measles despite appropriate prevention and control measures. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:438–449. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uzicanin A, Zimmerman L. Field effectiveness of live attenuated measles-containing vaccines: a review of published literature. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 1):S133–S148. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Serres G, Boulianne N, Defay F. Higher risk of measles when the first dose of a 2-dose schedule of measles vaccine is given at 12–14 months versus 15 months of age. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:394–402. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carazo Perez S, De Serres G, Bureau A, Skowronski DM. Reduced antibody response to infant measles vaccination: effects based on type and timing of the first vaccine dose persist after the second dose. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1094–1102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.