Abstract

The genetic basis of morphological variation, both within and between species, provides a major topic in evolutionary biology. Teleost fish produce most elaborate color patterns, and among the more than 20 000 species a number have been chosen for more detailed analyses because they are suitable to study particular aspects of color pattern evolution. In several fish species, color variants and pattern variants have been collected, transcriptome analyses have been carried out, and the recent advent of gene editing tools, such as CRISPR/Cas9, has allowed the production of mutants. Covering mostly the literature from the last three years, we discuss the cellular basis of coloration and the identification of loci involved in color pattern differences between sister species in cichlids and Danio species, in which cis-regulatory changes seem to prevail.

Current Opinion in Genetics and Development 2019, 57:31–38

This review comes from a themed issue on Developmental mechanisms, patterning and evolution

Edited by Gáspár Jékely and Maria Ina Arnone

For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial

Available online 14th August 2019

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2019.07.002

0959-437X/© 2019 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

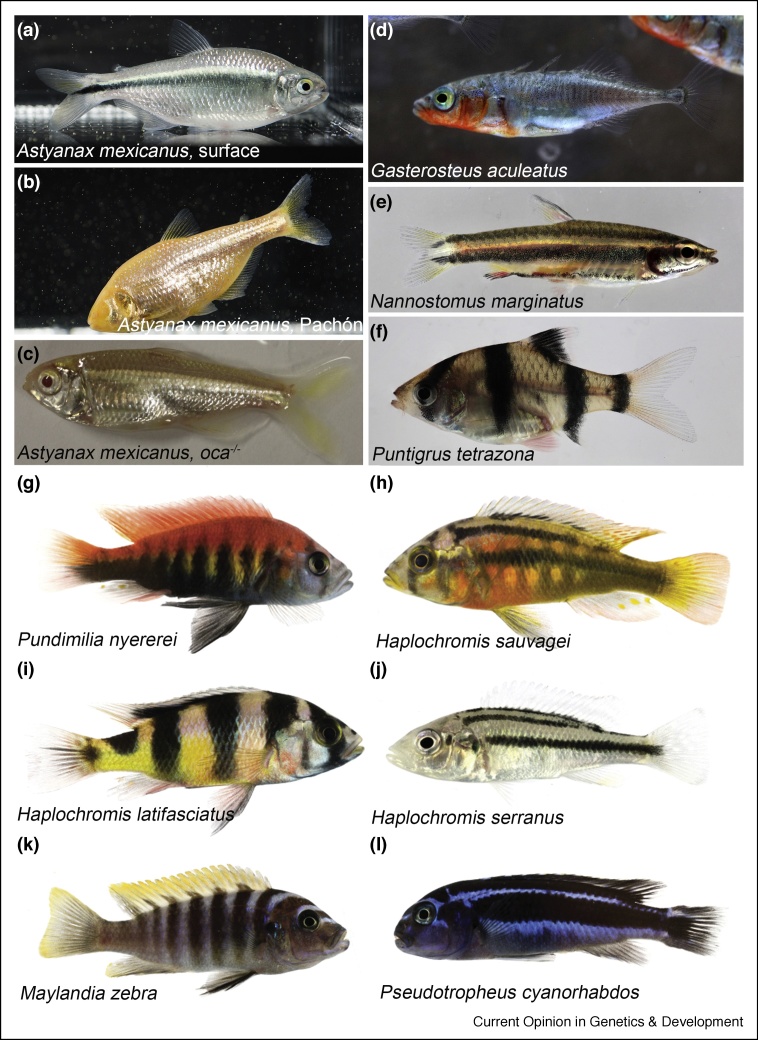

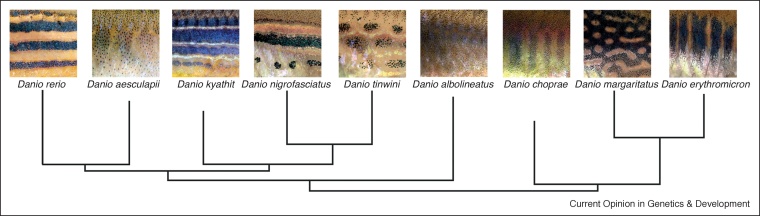

Color patterns are a striking feature of animals, they evolve rapidly and play important roles in natural as well as sexual selection. Often strikingly elaborate, they serve as camouflage in predator avoidance, and have important roles in kin recognition and mate selection [1]. To study the genetic basis of color pattern evolution it is advantageous to concentrate on organisms where interbreeding is possible and transgenic and imaging methods are applicable. Teleost fish are well suited as vertebrate models because offspring develop outside the maternal organism allowing inspection of the pattern throughout development. In several fish genera closely related species still interbreed, for example, in sticklebacks or cavefish (Figure 1a–d) [2,3]. These species, however, are not very rich in patterns, with the notable exception of the cichlids from the great African lakes [4] (for examples see Figure 1g–l). Here genes responsible for the evolution of coloration can be identified by genetic mapping of QTLs via backcrosses [5]. Clearly the zebrafish, Danio rerio, as a well-developed model system for biomedical research, combines a number of advantages making it an outstanding system also to study color pattern evolution [6, 7, 8]. Zebrafish display a stereotyped pattern of horizontal stripes, whereas other closely related Danio species show quite diverse patterns (Figure 2). In the Danio genus hybrids are generally viable but sterile [6,7]; on the other hand a large collection of color pattern mutants have been collected in zebrafish providing test cases for candidate genes involved in speciation. Furthermore, an elaborate tool kit has been developed in zebrafish resulting in a rather detailed knowledge of the cellular and genetic basis of color patterning, which provides a foundation for the understanding of variation in color patterns during the evolution of teleost fish [9].

Figure 1.

Color patterns in fish.

Fish often show a silvery skin with additional color patterns; many cavefish are unpigmented. (a–c): Astyanax mexicanus (Mexican tetra) surface form (a), unpigmented cave form (Pachón) (b), oca2 mutant (c). Gasterosteus aculeatus (Three-spined stickleback) male displaying the bright red pigmentation that evolved by sexual selection (d). (e), (f): horizontal stripes and vertical bars are frequent motifs in fish patterning: Nannostomus marginatus (e), Puntigrus tetrazona (f), fish commonly found in the pet trade. African cichlids from Lake Victoria (g–j) and Lake Malawi (k,l). Pundamilia nyererei (g), Haplochromis sauvagei (h), Haplochromis latifasciatus (i), Haplochromis serranus (j), Maylandia zebra (k), Pseudotropheus cyanorhabdos (l). Images courtesy: N. Rohner (a,b), J. Kowalko (c), C. Kratochwil (g–l).

Figure 2.

Pigment pattern evolution in Danio fish.

Depicted are details of the pigmentation patterns on the flanks of different, closely related, Danio fish. The patterns range from horizontal stripes, vertical bars, spots in combination with stripes, dark spots on a light background and light spots on a dark background, absence of pattern. Their phylogenetic relationships are drawn according to Ref. [52].

Counter shading

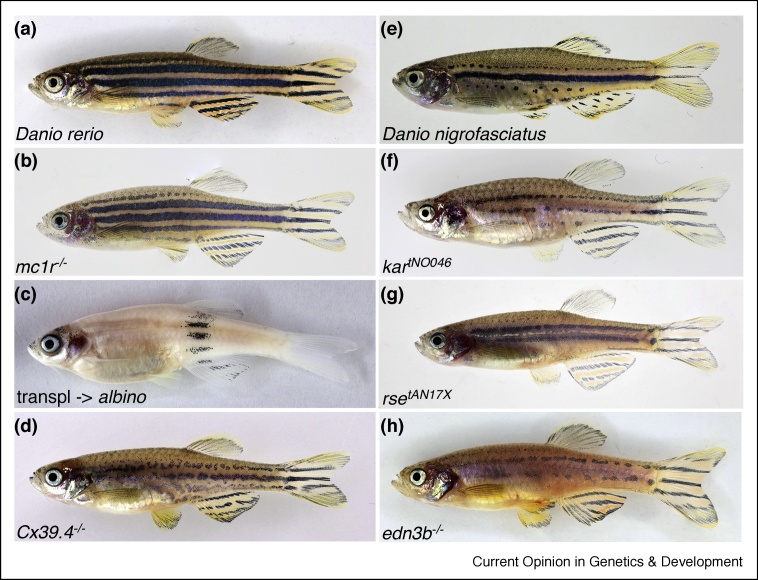

The primary functions of colors in animals are to shield against UV-irradiation from sunlight [10] and to camouflage from predators. Many fish are cast in a silvery skin produced by light-reflecting iridophores, topped with black melanophores giving them a dark back and light belly to render them less visible. This dorso-ventral pigment patterning is one of the most widespread chromatic adaptations in vertebrates and presumably evolved through natural selection. In mammals countershading depends on differential expression of Agouti-signaling protein (Asip), an antagonist for Melanocortin receptor1 (Mc1r), which leads to the switch from eumelanin to pheomelanin synthesis within melanocytes [11,12]. Teleost fish do not produce pheomelanin, but they share countershading, which results from the differential distribution of dark melanophores that are most abundant dorsally. Importantly, the mechanism in fish is also dependent on Agouti signaling [13,14]. asip1 displays a dorso-ventral expression gradient in the skin of several fish species with low levels in the dorsum and high levels ventrally. Overexpression of asip1 in zebrafish leads to a loss of dorsal melanophores [13]. A similar phenotype arises from the loss of mc1r (U. I. unpublished, Figure 3b). Interestingly, the striped pattern is unaffected; the dorso-ventral countershading mechanism acts independently from the more recently evolved striping mechanism with resultant patterns superimposed to generate the full pattern.

Figure 3.

Patterning in Danio rerio and Danio nigrofasciatus.

Wild type zebrafish (Danio rerio) show a pattern of light and dark stripes on top of a dorso-ventral pigmentation gradient (a). Mutations in mc1r lead to a loss of dorsal melanophores but do not affect the striped pattern. Note that, in addition, dispersed melanophores appear at regions outside the striped flank area (b). Clones created by blastomere transplantation of pigmented melanophores into an albino mutant host show the dorso-ventral spreading of the pigmented cells, presumably caused by the trajectories of the spinal nerves, along which melanoblasts reach the skin (c). Disruption of cell–cell interactions leads to patterning defects, as shown in the break-up of stripes in luc/Cx39.4−/− mutants (d) [36]. Danio nigrofasciatus(e) show an attenuated pattern of fewer stripes and lower numbers of melanophores that break up into spots similar to zebrafish mutants with defects in endothelin-signaling, for example, endothelin-converting enzyme ece2/karneoltNO046(f), weak allele of endothelin receptor3a ednr3a/rosetAN17X(g), and endothelin edn3b−/−(h).

In the Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) the asymmetrical coloration of the right and left sides is also under the control of the Agouti-system. However, here it is not high asip1 levels that correlate with the lack of coloration, instead, the expression levels of three receptors, mc1r, mc5r, and melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 2 are higher in pigmented areas [15].

The asip1 expression gradient is not restricted to Teleost fish, but is also found in the ray-finned fish spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus), which diverged from teleosts before the teleost-specific genome duplications. The expression pattern correlates with the differential dorso-ventral pigmentation in gar [16•]. This demonstrates that countershading is an evolutionary old system that arose before the whole genome duplication events in teleost fish.

Pigmentation

Mc1r has repeatedly been found mutated in different vertebrate species suggesting that it is a target for regressive evolution, for example, in non-pigmented cave adapted organisms [17•]. However, mutations in Mc1r are not the only causes for depigmentation. In two independent populations of Mexican cavefish (Astyanax mexicanus) QTL mapping suggested the oca-2 gene as a candidate for pigment loss [18]. This was now confirmed by a gene knock-out in the surface form and subsequent complementation tests [19•] (Figure 1a–c).

Birds and mammals have only a single pigment cell type, the melanocyte. In contrast, teleost fish develop at least six classes of pigment cells (chromatophores) leading to a fascinating diversity of colors. In addition to black melanophores and light-reflecting iridophores there are yellow–orange xanthophores, red erythrophores, white leucophores, and blue cyanophores. The pigment cells are distributed in superimposed layers between epidermis and myotome and can be found on scales. The stereotyped arrangement of chromatophores in the skin, which is also present in amphibia and reptiles, consists of xanthophores/erythrophores in the outermost layer that contain pteridine-based pigments absorbing short-wavelength light. Underneath, in the middle layer, there are S-iridophores, which reflect and interfere with light due to purine-based crystalline platelets. Melanophores in the basal-most layer absorb light across the spectrum [20]. Bounding the myotome, a continuous sheet of reflective L-iridophores shields the body from UV irradiation. Combinations of differently colored cells and variations in the distribution and shapes of chromatophores lead to a rich spectrum of colors and patterns.

The cellular origin of white color in fish is linked to diverse pigment-cell-types. White color may be produced by iridophores; in zebrafish, for example, the light stripes are composed of an epithelial-like dense sheet of whitish iridophores topped with yellow or orange xanthophores. The white coloration in Medaka (Oryzias latipes), in contrast, is produced by leucophores, which are related to xanthophores and contain white pteridine-based pigments [21]. Recently it was shown that Danio species produce two distinct classes of leucophores with independent developmental origins and cellular architectures. Xantho-leucophores are clonally related to xanthophores like those in Medaka, whereas melano-leucophores originate from pigmented melanophores that acquire white guanine-based particles while losing melanin. Single cell transcriptomics confirms the distinct classes and their clonal relationships [22•]. The melano-leucophores have not been described previously, their appearance in eight of nine Danio species serves to add contrast to the patterns, which is recognized by conspecifics and thus appears to have functional evolutionary significance.

In the clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris) two vertical white bars are observed on the orange colored body. Transcriptomic analysis and electron microscopy of the white chromatophores indicate that these are indeed iridophores. This notion is further supported by pharmacological inhibition of iridophore differentiation during early development, which leads to an elimination of the white bars as well as L-iridophores underlying the orange regions [23•].

The ontogeny of the adult pattern

In zebrafish the origin of chromatophores has recently been elucidated in a comprehensive lineage analysis of clones induced in Sox10 expressing neural-crest-derived cells [24,25] (reviewed in Ref. [9]). Pigment cells producing the adult pattern are derived from multipotent neural-crest-derived stem cells located at the dorsal root ganglia of the peripheral nervous system, they share a lineage with peripheral nerves and glia. Progenitors of iridophores and melanophores migrate to the skin along spinal nerves. Melanophores expand in number while migrating as melanoblasts whereas iridophores proliferate after they have reached the skin and then spread. Pigmented melanophores rarely divide once in the skin. Xanthophores arise from larval xanthophores as well as from the stem cells. The proliferation of pigment cells is regulated by competitive interactions among cells derived from neighboring segments, resulting in a vertical orientation of stem-cell-clones. These homotypic interactions are controlled by cell-type-specific signaling systems [26]. Different receptor–ligand pairs regulate specification, proliferation and maintenance of each pigment cell type. These are Kit-signaling in melanophores [27], Leukocyte tyrosine kinase-signaling [28, 29, 30] and Endothelin-signaling in iridophores [31,32], and Colony stimulating factor-signaling [33] in xanthophores. An even spacing involves collective migration and contact inhibition of locomotion of the three cell types [26]. This mode of coloring the skin is probably widespread in fish, whereas different patterns emerge by species- specific cell interactions among the different pigment-cell-types [9].

In zebrafish a number of genes are known that are autonomously required in pigment cells to achieve interactions between different types of chromatophores by direct cell contact [34]. These typically encode integral membrane proteins such as adhesion molecules [35], components of cellular junctions or channels [36, 37, 38]. Except for a single morphological cue, the horizontal myoseptum, which orients the stripes along the body axis [39], the pattern is self-organizing. In some other Danio species with patterns different from zebrafish the horizontal myoseptum as a morphological cue is not used; vertical bars, like horizontal stripes a frequent motif in fish patterns (Figure 1), may be guided by the dorso-ventral trajectories of the spinal nerves along which the melanophores reach the skin (Figure 3c). Iridophores play a leading role for the development of the stripes in the body of zebrafish. Emerging along the horizontal myoseptum they disperse dorso-ventrally in a loose shape and, by patterned aggregation to a dense shape, sequentially produce more light stripes delineating the dark stripe regions where melanophores emerge [25]. During the patterning process melanophores and xanthophores do not move much, and the patterning mechanism involves characteristic shape changes of iridophores and xanthophores essential for the exact superposition of the cells to achieve the precise striping of the pattern [25,40,41]. A number of short-range and long-range interactions among the three cell types have been deduced from mutant phenotypes and cell ablation studies. Iridophores promote and sustain melanophores and they attract xanthophores, whereas xanthophores repel melanophores [39,42]. Recently a novel mathematical model has been formulated [43••]. It attributes a central role to iridophores, a cell type neglected in previously favored models of Turing-type mechanisms focusing on melanophores and xanthophores only [44, 45, 46, 47]. The authors of the new model propose a number of specific cellular interactions underlying iridophore shape transitions during stripe formation. This results in different iridophore and xanthophore shapes between light and dark stripe areas, as observed in vivo. They show the efficacy of their model by producing a striped pattern through simulations. The model describes redundancies among these interactions likely accounting for the robustness of the patterning process. It also shows how evolutionary changes may occur through loss of specific interactions [43••]. Thus the model can be used to guide predictions about the evolution of diverging patterns, which may be tested experimentally.

Pattern diversification

The identification of specific genetic variations underlying phenotypic changes is a major challenge in evolutionary biology. Considering pattern differences between two closely related species, several approaches have been used to identify genes involved in the evolution of coloration and pattern. In the last 8–12 million years several hundred species of cichlid fish evolved during repeated adaptive radiations in the East African Rift Valley lakes, such as Lakes Victoria, Tanganyika, and Malawi [4]. These radiations gave rise to a large diversity of species displaying various color patterns, including vertical bars, horizontal stripes, combinations of both, and blotches. Recently it was shown that sex-specific blotched color morphs found in multiple species across several genera of Lake Malawi cichlids are caused by an allelic series at pax7a that lead to varying transcript levels [48]. Horizontal dark stripes evolved repeatedly in all three African lake systems. Genetic mapping of the stripe trait between two striped species from Lake Victoria and an interbreeding non-striped species revealed that horizontal stripes are inherited as a recessive Mendelian trait [5] (see also Figure 1). Further mapping identified the gene coding for Agouti-related peptide 2 (Agrp2) as the crucial factor controlling stripe formation [49••]. The peptide itself displays no significant sequence divergence between the species; however, expression is higher in the non-striped species. This suggests that Agrp2 acts as a suppressor of stripe formation. Indeed, CRISPR-mediated knock out of agrp2 in a non-striped species led to the appearance of a horizontal stripe. However, lack of the second stripe indicates that further genetic differences account for the species-specific pigment patterning [49••]. In another pair of interbreeding fish from lake Malawi, the striped trait was also mapped to the agrp2 region. In addition, further analysis revealed higher levels of expression in several other non-striped species from lakes Tanganyika and Malawi (Figure 1g–l), compared to their non-striped sister species, confirming convergent evolution in the three independent radiations [49••]. Interestingly, agrp2 expression is not correlated with the site of the stripe appearance, but likely acts as a more general antagonist for the melanocortin receptors, in a similar manner to Asip. Recurrent mutations at the agrp2 locus constitute an example of regulatory tinkering that might have facilitated the ease and speed of the evolution of both convergent and divergent phenotypes that characterize the East African cichlid radiations.

In the Danio genus, the zebrafish D. rerio and its close relative Danio nigrofasciatus differ in the number of stripes and the melanophore content; the D. nigrofasciatus pattern resembles the phenotype of weak alleles of genes involved in endothelin signaling in D. rerio (Figure 3e–h). In zebrafish, endothelin signaling is required cell autonomously in iridophores for their development and proliferation, and iridophores indirectly promote and sustain melanophore development: Mutants eliminating iridophores display fewer dark stripes, which tend to break up into spots (Figure 3f–h) [39]. In D. nigrofasciatus, specifically, the expression of the secreted ligand Endothelin-3 (Edn3b) occurs at lower levels due to cis-regulatory changes [50••]. Interspecies hybrids display an intermediate phenotype and show lower edn3b expression from the nigrofasciatus allele, which behaves like a hypomorph. Edn3b overexpression is sufficient to increase iridophore coverage, and alter melanophore distributions in D. nigrofasciatus to a state more similar to that of D. rerio [50••].

Conclusions

Fish have most elaborate color patterns composed of multiple cell types producing diverse pigments or light-reflecting nano-structures. Consequently, a relatively large number of genes have been identified as ‘pigmentation genes’. In part this high number results from the teleost-specific genome duplications, as it was shown that duplicates among pigmentation genes were preferentially retained after the teleost-specific and the salmonid-specific duplication events [51]. Many cases are known of paralogs, one of which has specialized for coloration while the other takes over the essential functions. This has allowed a rather rich collection of adult viable mutants specifically affected in coloration [34]. Indeed, in zebrafish several mutant phenotypes are reminiscent of the pattern of other Danio species [50••] (see Figure 3d–h), although in general it is expected that changes at multiple loci underlie the diversification of the pattern between two species. QTL-mapping is possible in interbreeding species of fish, such as cichlids and cavefish, and the identification of agrp2 as a gene responsible for pattern differences in cichlids presents significant progress [49••]. Genetic mapping is not possible with Danios because inter-species hybrids are invariably sterile. However, in this species we have a profound knowledge about the cell biology of pigment pattern formation, including cell lineages and cell–cell interactions; and many mutations with striking patterning phenotypes exist. A crucial candidate gene, edn3b, for the differences between two species was found due to the mutant phenotype in D. rerio (Figure 3) [50••].

In several populations of Mexican cavefish mutations in the coding region of genes involved in melanin synthesis, such as mc1r and oca-2, have been identified as causing depigmentation. In other cases, the coding region is not affected but cis-regulatory changes that result in very low expression in one population seem to be responsible for the differences. Cis-regulatory rather than coding sequence changes are frequent in speciation; by just eliminating the function of one of the many pigmentation genes conspicuous effects in phenotype may be produced. There is a large degree of redundancy in the system, however, and single gene mutations resulting in significant phenotypic changes are rare. In particular, the pigment cell autonomous functions, which include direct heterotypic cell–cell interactions as shown during zebrafish stripe formation, have only been speculated to play roles in speciation so far, without direct proof. Strikingly, in the recent case studies discussed in this essay, targeted gene knock out using the CRISPR/Cas9 system played a crucial role, which demonstrates that the field of evolutionary genetics will generally profit enormously from this powerful novel technology. Fish systems such as zebrafish and cichlids will probably yield answers of significance also for color patterning in mammals and birds in which such investigations are far more complicated [8].

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

We thank Marco Podobnik for comments on the manuscript, and N. Rohner, C. Dooley, J. Kowalko and C. Kratochwil for images. This work was supported by ERC Advanced Grant “Danio pattern” (no. 694289) and the Max-Planck-Society.

References

- 1.Cuthill I.C., Allen W.L., Arbuckle K., Caspers B., Chaplin G., Hauber M.E., Hill G.E., Jablonski N.G., Jiggins C.D., Kelber A. The biology of color. Science. 2017;357 doi: 10.1126/science.aan0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kingsley D.M., Peichel C.L. Biology of the three-spined stickleback. In: Lutz P.L., editor. Marine Biology. CRC Press; 2007. [Östlund-Nilsson S, Mayer I, Huntingford FA (Series Editor) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres-Paz J., Hyacinthe C., Pierre C., Retaux S. Towards an integrated approach to understand Mexican cavefish evolution. Biol Lett. 2018;14 doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maan M.E., Sefc K.M. Colour variation in cichlid fish: developmental mechanisms, selective pressures and evolutionary consequences. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2013;24:516–528. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henning F., Lee H.J., Franchini P., Meyer A. Genetic mapping of horizontal stripes in Lake Victoria cichlid fishes: benefits and pitfalls of using RAD markers for dense linkage mapping. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:5224–5240. doi: 10.1111/mec.12860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parichy D.M. Evolution of danio pigment pattern development. Heredity (Edinb) 2006;97:200–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parichy D.M., Johnson S.L. Zebrafish hybrids suggest genetic mechanisms for pigment pattern diversification in Danio. Dev Genes Evol. 2001;211:319–328. doi: 10.1007/s004270100155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh A.P., Nusslein-Volhard C. Zebrafish stripes as a model for vertebrate colour pattern formation. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R81–R92. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nusslein-Volhard C., Singh A.P. How fish color their skin: a paradigm for development and evolution of adult patterns: multipotency, plasticity, and cell competition regulate proliferation and spreading of pigment cells in Zebrafish coloration. Bioessays. 2017;39 doi: 10.1002/bies.201600231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapp F.G., Perlin J.R., Hagedorn E.J., Gansner J.M., Schwarz D.E., O’Connell L.A., Johnson N.S., Amemiya C., Fisher D.E., Wolfle U. Protection from UV light is an evolutionarily conserved feature of the haematopoietic niche. Nature. 2018;558:445–448. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0213-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millar S.E., Miller M.W., Stevens M.E., Barsh G.S. Expression and transgenic studies of the mouse agouti gene provide insight into the mechanisms by which mammalian coat color patterns are generated. Development. 1995;121:3223–3232. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrieling H., Duhl D.M., Millar S.E., Miller K.A., Barsh G.S. Differences in dorsal and ventral pigmentation result from regional expression of the mouse agouti gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5667–5671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cal L., Suarez-Bregua P., Comesana P., Owen J., Braasch I., Kelsh R., Cerda-Reverter J.M., Rotllant J. Countershading in zebrafish results from an Asip1 controlled dorsoventral gradient of pigment cell differentiation. Sci Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40251-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceinos R.M., Guillot R., Kelsh R.N., Cerda-Reverter J.M., Rotllant J. Pigment patterns in adult fish result from superimposition of two largely independent pigmentation mechanisms. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28:196–209. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda N., Kasagi S., Nakamaru T., Masuda R., Takahashi A., Tagawa M. Left-right pigmentation pattern of Japanese flounder corresponds to expression levels of melanocortin receptors (MC1R and MC5R), but not to agouti signaling protein 1 (ASIP1) expression. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2018;262:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Cal L., MegIas M., Cerda-Reverter J.M., Postlethwait J.H., Braasch I., Rotllant J. BAC recombineering of the agouti loci from spotted gar and zebrafish reveals the evolutionary ancestry of dorsal-ventral pigment asymmetry in fish. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2017;328:697–708. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.22748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors show that countershading, which depends on asymmetric expression of Agouti-signaling protein, is an evolutionary old system that probably arose before the origin of teleosts.

- 17•.Espinasa L., Robinson J., Espinasa M. Mc1r gene in Astroblepus pholeter and Astyanax mexicanus: convergent regressive evolution of pigmentation across cavefish species. Dev Biol. 2018;441:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study the gene coding for Melanocortin receptor 1, Mc1r, is shown to be mutated in a cave-adapted catfish from Equador.

- 18.Protas M.E., Hersey C., Kochanek D., Zhou Y., Wilkens H., Jeffery W.R., Zon L.I., Borowsky R., Tabin C.J. Genetic analysis of cavefish reveals molecular convergence in the evolution of albinism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:107–111. doi: 10.1038/ng1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Klaassen H., Wang Y., Adamski K., Rohner N., Kowalko J.E. CRISPR mutagenesis confirms the role of oca2 in melanin pigmentation in Astyanax mexicanus. Dev Biol. 2018;441:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors used CRISPR/Cas9 to show that oca2 mutations are responsible for the naturally occurring albinism in different populations of the Mexican cavefish Astyanax mexicanus.

- 20.Hirata M., Nakamura K., Kanemaru T., Shibata Y., Kondo S. Pigment cell organization in the hypodermis of zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:497–503. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura T., Nagao Y., Hashimoto H., Yamamoto-Shiraishi Y., Yamamoto S., Yabe T., Takada S., Kinoshita M., Kuroiwa A., Naruse K. Leucophores are similar to xanthophores in their specification and differentiation processes in medaka. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:7343–7348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311254111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Lewis V.M., Saunders L.M., Larson T.A., Bain E.J., Sturiale S.L., Gur D., Chowdhury S., Flynn J.D., Allen M.C., Deheyn D.D. Fate plasticity and reprogramming in genetically distinct populations of Danio leucophores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:11806–11811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901021116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes the widespread occurrence of two classes of leucophores in Danio fish. Xantho-leucophores related to xanthophores and melano-leucophores, which originate from pigmented melanophores by acquiring white guanine-based light-reflecting particles while losing melanin.

- 23•.Salis P., Lorin T., Lewis V., Rey C., Marcionetti A., Escande M.L., Roux N., Besseau L., Salamin N., Semon M. Developmental and comparative transcriptomic identification of iridophore contribution to white barring in clownfish. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2019;32:391–402. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study the authors found that the white bars in clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris) depend on iridophores, similar to light stripes in zebrafish, not on leucophores, as found in medaka.

- 24.Singh A.P., Dinwiddie A., Mahalwar P., Schach U., Linker C., Irion U., Nusslein-Volhard C. Pigment cell progenitors in zebrafish remain multipotent through metamorphosis. Dev Cell. 2016;38:316–330. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh A.P., Schach U., Nusslein-Volhard C. Proliferation, dispersal and patterned aggregation of iridophores in the skin prefigure striped colouration of zebrafish. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:607–614. doi: 10.1038/ncb2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walderich B., Singh A.P., Mahalwar P., Nusslein-Volhard C. Homotypic cell competition regulates proliferation and tiling of zebrafish pigment cells during colour pattern formation. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dooley C.M., Mongera A., Walderich B., Nusslein-Volhard C. On the embryonic origin of adult melanophores: the role of ErbB and Kit signalling in establishing melanophore stem cells in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:1003–1013. doi: 10.1242/dev.087007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fadeev A., Krauss J., Singh A.P., Nusslein-Volhard C. Zebrafish Leucocyte tyrosine kinase controls iridophore establishment, proliferation and survival. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2016;29:284–296. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadeev A., Mendoza-Garcia P., Irion U., Guan J., Pfeifer K., Wiessner S., Serluca F., Singh A.P., Nusslein-Volhard C., Palmer R.H. ALKALs are in vivo ligands for ALK family receptor tyrosine kinases in the neural crest and derived cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E630–E638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719137115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mo E.S., Cheng Q., Reshetnyak A.V., Schlessinger J., Nicoli S. Alk and Ltk ligands are essential for iridophore development in zebrafish mediated by the receptor tyrosine kinase Ltk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:12027–12032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710254114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krauss J., Frohnhofer H.G., Walderich B., Maischein H.M., Weiler C., Irion U., Nusslein-Volhard C. Endothelin signalling in iridophore development and stripe pattern formation of zebrafish. Biol Open. 2014;3:503–509. doi: 10.1242/bio.20148441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parichy D.M., Mellgren E.M., Rawls J.F., Lopes S.S., Kelsh R.N., Johnson S.L. Mutational analysis of endothelin receptor b1 (rose) during neural crest and pigment pattern development in the zebrafish Danio rerio. Dev Biol. 2000;227:294–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parichy D.M., Ransom D.G., Paw B., Zon L.I., Johnson S.L. An orthologue of the kit-related gene fms is required for development of neural crest-derived xanthophores and a subpopulation of adult melanocytes in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 2000;127:3031–3044. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irion U., Singh A.P., Nusslein-Volhard C. The developmental genetics of vertebrate color pattern formation: lessons from zebrafish. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2016;117:141–169. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eom D.S., Inoue S., Patterson L.B., Gordon T.N., Slingwine R., Kondo S., Watanabe M., Parichy D.M. Melanophore migration and survival during zebrafish adult pigment stripe development require the immunoglobulin superfamily adhesion molecule Igsf11. PLoS Genet. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irion U., Frohnhofer H.G., Krauss J., Colak Champollion T., Maischein H.M., Geiger-Rudolph S., Weiler C., Nusslein-Volhard C. Gap junctions composed of connexins 41.8 and 39.4 are essential for colour pattern formation in zebrafish. eLife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe M., Iwashita M., Ishii M., Kurachi Y., Kawakami A., Kondo S., Okada N. Spot pattern of leopard Danio is caused by mutation in the zebrafish connexin41.8 gene. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:893–897. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe M., Sawada R., Aramaki T., Skerrett I.M., Kondo S. The physiological characterization of Connexin41.8 and Connexin39.4, which are involved in the striped pattern formation of zebrafish. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:1053–1063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.673129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frohnhofer H.G., Krauss J., Maischein H.M., Nusslein-Volhard C. Iridophores and their interactions with other chromatophores are required for stripe formation in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:2997–3007. doi: 10.1242/dev.096719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahalwar P., Singh A.P., Fadeev A., Nusslein-Volhard C., Irion U. Heterotypic interactions regulate cell shape and density during color pattern formation in zebrafish. Biol Open. 2016;5:1680–1690. doi: 10.1242/bio.022251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahalwar P., Walderich B., Singh A.P., Nusslein-Volhard C. Local reorganization of xanthophores fine-tunes and colors the striped pattern of zebrafish. Science. 2014;345:1362–1364. doi: 10.1126/science.1254837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patterson L.B., Parichy D.M. Interactions with iridophores and the tissue environment required for patterning melanophores and xanthophores during zebrafish adult pigment stripe formation. PLoS Genet. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43••.Volkening A., Sandstede B. Iridophores as a source of robustness in zebrafish stripes and variability in Danio patterns. Nat Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05629-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study an agent-based mathematical model for stripe formation in zebrafish has been formulated based on empirical data on cell interactions. Importantly the model includes iridophores, which may act as a source of robustness for the patterning mechanism. The model also predicts differences in cell–cell interactions that could lead to the divergence of patterns in different species.

- 44.Singh A.P., Frohnhofer H.G., Irion U., Nusslein-Volhard C. Fish pigmentation. response to comment on “Local reorganization of xanthophores fine-tunes and colors the striped pattern of zebrafish”. Science. 2015;348:297. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe M., Kondo S. Fish pigmentation. Comment on “Local reorganization of xanthophores fine-tunes and colors the striped pattern of zebrafish”. Science. 2015;348:297. doi: 10.1126/science.1261947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kondo S. An updated kernel-based Turing model for studying the mechanisms of biological pattern formation. J Theor Biol. 2017;414:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe M., Kondo S. Is pigment patterning in fish skin determined by the Turing mechanism? Trends Genet. 2015;31:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts R.B., Moore E.C., Kocher T.D. An allelic series at pax7a is associated with colour polymorphism diversity in Lake Malawi cichlid fish. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:2625–2639. doi: 10.1111/mec.13975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49••.Kratochwil C.F., Liang Y., Gerwin J., Woltering J.M., Urban S., Henning F., Machado-Schiaffino G., Hulsey C.D., Meyer A. Agouti-related peptide 2 facilitates convergent evolution of stripe patterns across cichlid fish radiations. Science. 2018;362:457–460. doi: 10.1126/science.aao6809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identified regulatory changes of the gene agouti-related peptide 2 (agrp2) as responsible for the convergent evolution of striped patterns in multiple flocks of cichlid fish from the great African lakes. They show that reduced expression of agrp2 is associated with the presence of horizontal stripes and that a CRISPR/Cas9-generated mosaic knockout of agrp2 in a nonstriped species reconstitutes stripes.

- 50••.Spiewak J.E., Bain E.J., Liu J., Kou K., Sturiale S.L., Patterson L.B., Diba P., Eisen J.S., Braasch I., Ganz J. Evolution of Endothelin signaling and diversification of adult pigment pattern in Danio fishes. PLoS Genet. 2018;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study the authors show that differences in Endothelin-3 expression contribute to the differences in iridophore complement and striping pattern in two related Danio species, Danio rerio and Danio nigrofasciatus. Cis-regulatory differences between the two species lead to lower expression in Danio nigrofasciatus, to reduced iridophore proliferation and fewer stripes.

- 51.Lorin T., Brunet F.G., Laudet V., Volff J.N. Teleost fish-specific preferential retention of pigmentation gene-containing families after whole genome duplications in vertebrates. G3 (Bethesda) 2018;8:1795–1806. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCluskey B.M., Postlethwait J.H. Phylogeny of zebrafish, a “model species,” within Danio, a “model genus”. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:635–652. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]