Abstract

Chronic wounds—including diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure ulcers—represent a major health problem that demands an urgent solution and new therapies. Despite major burden to patients, health care professionals, and health care systems worldwide, there are no efficacious therapies approved for treatment of chronic wounds. One of the major obstacles in achieving wound closure in patients is the lack of epithelial migration. Here, we used multiple pre-clinical wound models to show that Caveolin-1 (Cav1) impedes healing and that targeting Cav1 accelerates wound closure. We found that Cav1 expression is significantly upregulated in wound edge biopsies of patients with non-healing wounds, confirming its healing-inhibitory role. Conversely, Cav1 was absent from the migrating epithelium and is downregulated in acutely healing wounds. Specifically, Cav1 interacted with membranous glucocorticoid receptor (mbGR) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in a glucocorticoid-dependent manner to inhibit cutaneous healing. However, pharmacological disruption of caveolae by MβCD or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Cav1 knockdown resulted in disruption of Cav1-mbGR and Cav1-EGFR complexes and promoted epithelialization and wound healing. Our data reveal a novel mechanism of inhibition of epithelialization and wound closure, providing a rationale for pharmacological targeting of Cav1 as potential therapy for patients with non-healing chronic wounds.

Keywords: Caveolin-1, skin re-epithelialization, chronic wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, wound healing

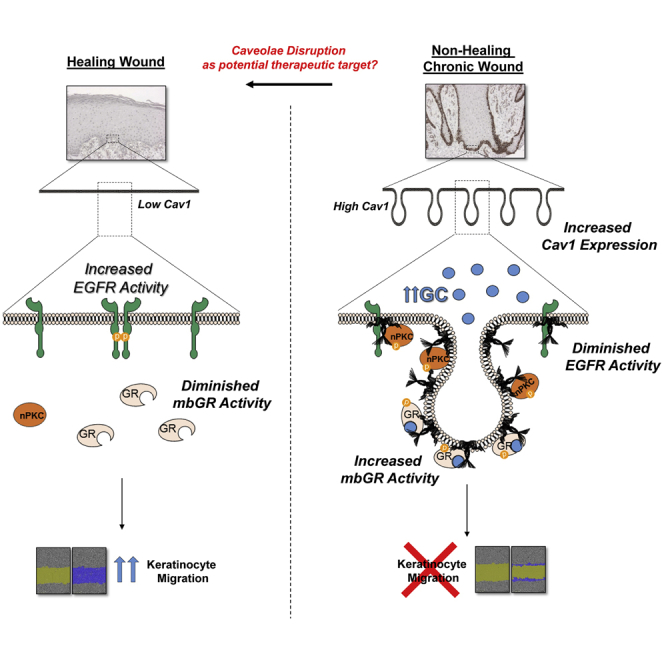

Graphical Abstract

Compartmentalization of signaling events at caveolae is crucial during wound healing. Jozic and colleagues show that human non-healing chronic wounds exhibit elevated levels of Caveolin-1, which inhibits keratinocyte migration by sequestering EGFR while promoting glucocorticoid signaling. They further demonstrate that disruption of caveolae accelerates keratinocyte migration and wound closure.

Introduction

Chronic wounds—including diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), venous leg ulcers, and pressure ulcers—represent a major health problem that demands an urgent solution and new therapies. Despite of the major burden to patients, health care professionals, and health care systems worldwide, there are no efficacious therapies approved for treatment of chronic wounds for nearly two decades.1 The lack of therapy derives from the multi-factorial and complex pathophysiology that is not yet fully understood, the lack of the animal model that recapitulates the human condition, and the complexity of the wound healing process itself.1, 2, 3 Cutaneous wound repair is a multifaceted process that involves a sequence of biological events characterized by an inflammatory response followed by proliferation and subsequent remodeling of the wounded tissue. Tight control of keratinocyte proliferation and migration are essential to successful re-epithelialization and wound healing, where keratinocytes must first migrate to cover the wound surface and then differentiate to form a stratified epithelium.

Balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory signals (or the lack of it) is one of the major players contributing to acute wound healing or pathophysiology of chronic wounds. Glucocorticoids (GCs) have commonly been used as major therapeutic agents that block inflammation, suppress immune system activation, and act as cell growth inhibitory agents and are known to inhibit epithelialization and wound healing.4, 5, 6 GCs mediate their effect via glucocorticoid receptors (GRs). The GR signaling can be genomic or nuclear regulating transcription or non-genomic via transcription-independent mechanisms that mediate rapid cellular responses to GCs.6, 7, 8, 9 Because most GR-dependent non-genomic signaling mechanisms originate from activation of membranous GR (mbGR), a cell-impermeable BSA-conjugated form of GCs can be used to study these non-genomic effects.6, 10, 11 Stimulation of the membrane fraction of mbGR leads to the activation of a signaling cascade (involving phospholipase C [PLC]/protein kinase C [PKC]/GSK-3β) that results in the inhibition of keratinocyte migration and wound healing. Furthermore, we have shown that inhibiting the aforementioned signaling cascade can restore the GC-mediated inhibition of wound closure.6

However, the mechanism by which GRs associate with the plasma membrane remains unclear. One possibility is by localizing to caveolae and associating with caveolin, similar to other steroid hormone receptors, including androgen and estrogen receptors.12, 13 Caveolae are cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich microdomains in the plasma membrane that allow the compartmentalization and clustering of signaling molecules. By oligomerization at caveolae, caveolins can compartmentalize various signal transduction molecules, affording orchestration of transmembrane signaling events and allowing cross-talk between various downstream effectors, thereby either sequestering certain proteins to alter their normal function(s) or bringing other molecules in close enough proximity to interact with each other (which, otherwise, would not).14 Caveolins are integral membrane proteins that have been shown to be essential for caveolar formation as well as for the binding and trafficking of cholesterol. They bind various structural and signaling molecules that contain a caveolin-binding domain, ranging from Rho GTPases to protein kinases, to growth factor receptors, and to heterotrimeric G proteins. In doing so, caveolins have been implicated in a variety of cellular processes, including vesicular transport, internalization of pathogens, integration of signaling pathways, and regulation of cell proliferation.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Caveolin-1 (Cav1) has long been implicated to be important in wound healing, as Cav1 null mice exhibit a significant increase in extracellular matrix of skin and lungs, with Cav1 null skin fibroblasts displaying a pro-fibrotic and hyper-proliferative phenotype as well as an increased susceptibility for tumor formation;20, 21, 22, 23 however, their exact role is yet to be fully understood. This is substantiated by inconsistencies in literature arising from different tissue and organismal models, where Cav1 can either promote or inhibit cell migration and subsequent wound healing, thus arguing for a context-dependent role.24, 25, 26, 27, 28

Cyclodextrins are a family of cyclic oligosaccharides that are commonly used as molecular chelating agents, of which β-cyclodextrin is the most commonly used, partly because it is the least irritating and most effective in binding cholesterol.29 Furthermore, due to its ability to bind cholesterol and free fatty acids, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) has been widely used in extracting cholesterol from plasma membranes.30, 31 Cholesterol is an essential part of every mammalian cellular and organelle membrane, and it is involved in various cellular processes ranging from maintaining membrane fluidity or permeability to membrane trafficking, to cell signaling, and to protein/lipid sorting, as well as formation of ordered liquid domains in membranes such as lipid rafts.32 Hence, studying caveolae and their subsequent disruption may point out the role Cav1 plays in controlling signaling and cellular behavior.

Here, we show that Cav1, found downregulated during cutaneous acute wound healing and almost absent from the migrating healing epithelium, is significantly upregulated in non-healing DFUs and venous leg ulcers (VLUs), two major types of chronic wounds. Furthermore, we show that Cav1 associates with both GR and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in primary human keratinocytes to inhibit migration and wound closure. Conversely, using a pharmacologic approach to disrupt caveolae through MβCD-mediated depletion of membrane cholesterol, or a targeted genetic approach of Cav1-CRISPR knockdown in multiple pre-clinical models, shows not only that mbGR-mediated inhibition of keratinocyte migration is reversed but also that EGFR is rescued from sequestration by Cav1 within the caveolae. Both approaches, disrupting the caveolae or Cav1KO, reverse signaling events induced by mbGR, resulting in accelerated wound closure. Together, our data provide evidence for a novel molecular mechanism by which Cav1, through interactions with mbGR and EGFR, inhibits keratinocyte migration and wound healing. This complex novel mechanism reveals a new therapeutic approach to stimulate wound healing through disruption of caveolae or targeting Cav1.

Results

Glucocorticoids Sequester GR and EGFR to Caveolin-Rich Membrane Microdomains to Potentiate mbGR and Antagonize EGFR Signaling, Which Can Be Reversed by Pharmacologic Caveolae Disruption or Genetic Targeting of Cav1

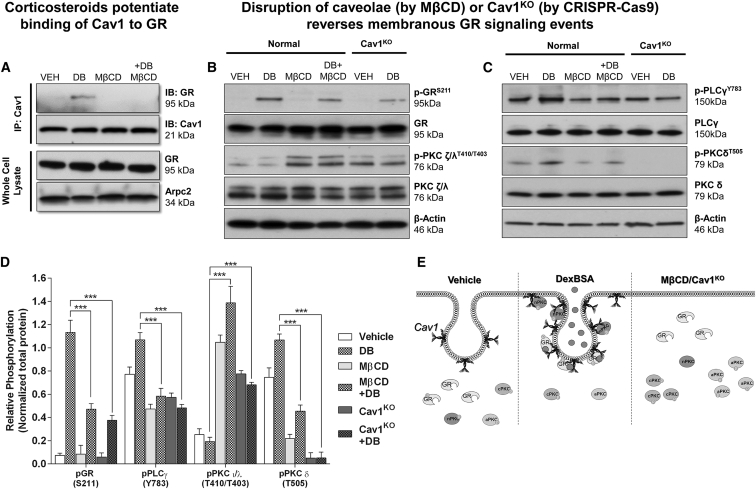

In lieu of our recent discovery that mbGR mediates inhibition of keratinocyte migration and wound healing,6 we aimed to determine whether mbGR localizes to caveolae and interacts with Cav1. To test this, we treated primary human keratinocytes with BSA-conjugated Dex (Dex-BSA), a cell-impermeable selective activator of mbGR,6 in the presence or absence of MβCD (a caveolae disruptor). Interaction of Cav1 and GR was assessed by Cav1 co-immunoprecipitation and subsequent immunoblotting, as well as by immunofluorescence. We observed that Dex-BSA stimulated the interaction of Cav1 and GR (Figure 1A; Figure S1), a complex that could be ameliorated by disrupting caveolae with MβCD (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Cav-1 Binds to mbGR, and Disruption of Caveolae Results in a Reversal of mbGR Effects in Primary Human Keratinocytes

(A) Primary human keratinocytes were stimulated with vehicle (DMSO) or 100 nM Dex-BSA (hereinafter referred to as DB) for 30 min in the presence or absence of 2% MβCD, followed by Cav1 co-immunoprecipitation. (B and C) Levels of total GR, phospho-GRS211, atypical total PKC ζ/λ, and phospho-PKC ζ/λT410/T403 (B) and levels of total PLCγ, p-PLCγY783, novel total PKC δ, and phospho-PKC δT505 (C) were assessed by immunoblotting; Arpc2 and β-actin were used as loading controls. Whole-cell lysate membranes were stripped and re-probed with appropriate antibodies. (D) Signals were quantified as amount of phosphorylated protein over total protein. Experiments were done in triplicates, with error bars corresponding to SDs from 3 biological triplicates with at least three technical replicates. ***p ≤ 0.001, two-way ANOVA. (E) Treatment with DexBSA causes interaction of Cav1 with pGR and nPKC and potentiates mbGR-mediated signaling events, which can be ameliorated either by disrupting caveolae (by MβCD) or knocking out Cav1 from the cells (Cav1KO).

We have previously shown that Dex-BSA induces a novel signaling pathway via activation of mbGR that functions through PLC/PKC/GSK-3β and results in the inhibition of keratinocyte migration and subsequent wound healing.3 To test whether Cav1 participates in this mechanism, we treated primary human keratinocytes with Dex-BSA for 1, 2, 5, 15, 30, or 60 min and subjected isolated proteins to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting to dissect this signaling cascade. First, we confirmed activation of both phospho-GRS211 and phospho-PLCγY783 (Figures S2A and S2B) but also found activation of novel (δ/θ) PKCs (Figure S2C). In addition, we also found a selective inhibition of atypical PKC ζ/λ isoenzymes (Figure S2D). Lastly, we detected a decrease in phosphorylation of a stimulatory site of EGFR (EGFRY1173), whereas phosphorylation of an inhibitory site (EGFRT654) was found to be increased upon treatment with Dex-BSA (Figure S2E). These data suggest that Cav1 participates in mediating mbGR signaling while inhibiting EGFR, which is in line with previous observations that GCs can antagonize EGFR signaling33, 34, 35 on the molecular level and in patients with chronic wounds who exhibit deregulated EGFR expression and localization.36, 37

Since mbGR interacts with Cav1, we postulated that caveolae disruption by MβCD treatment should reverse both mbGR and EGFR signaling cascades. To test this, we treated primary human keratinocytes with Dex-BSA in the presence of MβCD and assayed activation of the GR-PLCγ-PKC signaling cascade via SDS-PAGE and subsequent immunoblotting using phosphorylated antibodies against each proteins. We observed that disruption of caveolae by MβCD abrogated Dex-BSA-mediated activation of GR (Figure 1B). In addition, MβCD treatment reversed PLCγY783 and novel PKCδT505 phosphorylation (Figure 1C) while stimulating activity of atypical PKC ζ/λT410/T403 (Figure 1B). To make sure that this effect was driven by Cav1 and not any nonspecific outcomes due to cholesterol disruption from lipid rafts, we generated stable Cav1-knockout keratinocytes (Cav1KO) using a combination of Cav1-CRISPR/Cas9 and Cav1-homology-directed repair (HDR) plasmids (Figure S3) and compared our results to the disruption of caveolae by MβCD. As expected, knocking out Cav1 from human keratinocytes resulted in an effect similar to disruption of caveolae by MβCD, where treatment of keratinocytes with MβCD or KO of Cav1 from normal keratinocytes reversed the Dex-BSA-mediated activation of GR, PLCγ, and PKCδ while stimulating activation of PKC ζ/λ (Figures 1B and 1C).

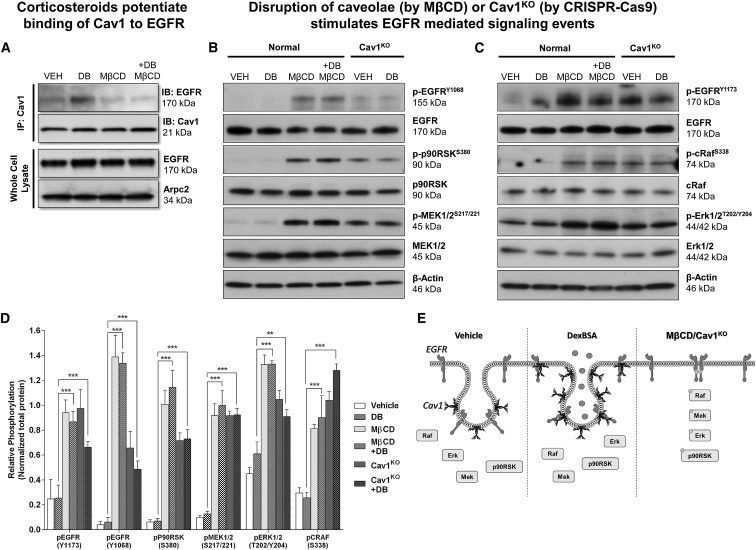

To test EGFR signaling, we used a similar approach. We observed that Dex-BSA stimulated the interaction of Cav1 and EGFR, which could be abrogated by disrupting caveolae with MβCD (Figure 2A). Moreover, MβCD treatment, or Cav1KO, rescued the inactivation of EGFR and subsequent signaling cascade, including p90RSK, MEK1/2 (Figure 2B), cRaf, and Erk1/2 (Figure 2C). Together, these data suggest that, in response to Dex-BSA, Cav1 orchestrates compartmentalization of both GR and EGFR at the caveolae and, thus, leads to reorganization of downstream signaling events associated with GR and EGFR, overall contributing to the inhibition of keratinocyte migration and wound closure.

Figure 2.

Cav-1 Binds Also to EGFR, and Disruption of Caveolae Results in a Rescue of EGFR Signaling in Primary Human Keratinocytes

(A) Primary human keratinocytes were stimulated with vehicle (DMSO) or 100 nM Dex-BSA for 2 min in the presence or absence of 2% MβCD, followed by Cav1 co-immunoprecipitation. (B and C) Levels of total EGFR, p-EGFRY1068, total cRaf, p-cRafS338, total Erk1/2, p-Erk1/2T202/Y204 (B) and levels of p-EGFRY1173, total p90RSK, p-p90RSKS380, total MEK1/2, and p-MEK1/2S217/221 (C) were assessed by immunoblotting. Whole-cell lysate membranes were stripped and re-probed with appropriate antibodies. (D) Signals were quantified as amount of phosphorylated protein over total protein. Experiments were done in triplicates, with error bars corresponding to SDs from biological triplicates with at least three technical replicates. **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001, two-way ANOVA. (E) Treatment with DexBSA causes interaction of Cav1 with EGFR and inhibits downstream EGFR-mediated signaling events, which can be reversed either by disrupting caveolae (by MβCD) or knocking out Cav1 from the cells (Cav1KO).

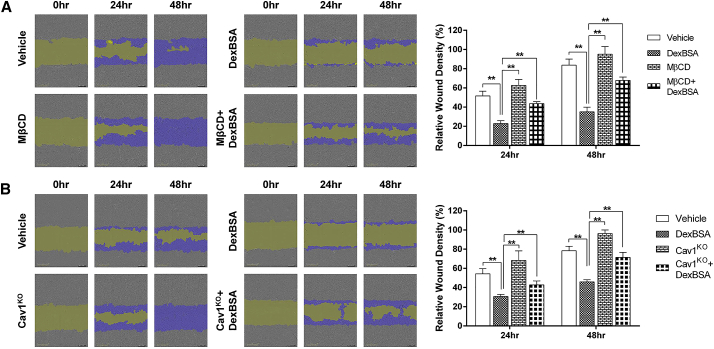

Caveolae Disruption Reverses GC-Mediated Inhibition of Keratinocyte Migration

To evaluate the functional consequence of caveolae disruption by MβCD and reversal of GC-mediated inhibition of keratinocyte migration, we performed a series of migration assays using primary human keratinocytes treated with Dex-BSA in the presence or absence of MβCD. As expected, we observed that treatment with Dex-BSA significantly inhibited keratinocyte migration, which was rescued by pretreatment with MβCD (Figure 3A). Interestingly, treatment of keratinocytes with MβCD alone showed a trend (albeit not statistically significant) in increasing relative migration in comparison to vehicle-treated control cells (Figure 3A). In order to exclude nonspecific secondary effects of MβCD, we repeated our wound migration assays using Cav1KO keratinocytes in the presence of Dex-BSA and observed results comparable to chemical inhibition by MβCD. Namely, Dex-BSA inhibited keratinocyte migration, while Cav1KO restored Dex-BSA-mediated inhibition (Figure 3B). Together, these data provide further evidence that Cav1 acts as a negative regulator of keratinocyte migration, while Cav1 suppression reverses the inhibitory effects of mbGR.

Figure 3.

Pharmacologic Disruption of Caveolae or Genetic Targeting of Cav1 Reverses GC-Mediated Inhibition of Keratinocyte Migration

(A and B) Control (A) or Cav1-deficient (B) human keratinocytes were pre-treated with 4 μg/mL mitomycin-C in the presence or absence of 2% MβCD and either vehicle (DMSO) or 100 nM Dex-BSA. Cells were wounded by a scratch, and their migration was assessed at the time of the scratch (0 h) and every 2 h for 48 h. Keratinocyte migration was quantified by comparing relative wound density using the Cell Migration Analysis software module (Essen BioScience) 24 and 48 h after the initial scratches were made; purple corresponds to repopulation of the wound over time by migrating cells. Error bars correspond to SD from 3 independent experiments with 16 technical replicates each. **p ≤ 0.01, two-way ANOVA.

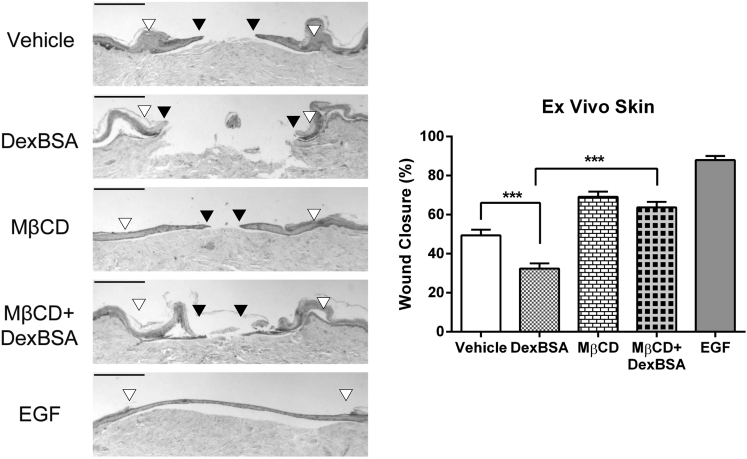

Caveolae Disruption Accelerates Wound Closure

To test the functional implications of disrupting Cav1-mbGR or Cav1-EGFR association, we utilized a human skin ex vivo wound model38, 39 and treated it with Dex-BSA, MβCD, or the combination of the two (EGF served as a positive control). As expected, histological assessments at day 5 post-wounding show that Dex-BSA treatment inhibited epithelialization, whereas EGF stimulated it (Figure 4). Pretreatment of skin with MβCD rescued Dex-BSA-mediated inhibition of wound healing (Figure 4). This acceleration of wound closure by MβCD in the presence of Dex-BSA can be attributed to a dual effect: blocking of activation of mbGR as well as rescue of EGFR.

Figure 4.

Disruption of Caveolae Accelerates Wound Healing and Rescues mbGR-Mediated Inhibition of Wound Closure in Human Skin

Human skin was wounded and maintained at the air-liquid interface in the presence or absence of 2% (w/v) MβCD, 100 nM Dex-BSA, or 25 ng/mL EGF. Wound healing was assessed at day 5 post-wounding, a time point when exponential epithelialization occurs. Gross photos show visual signs of closure and correspond to the histology assessments. White arrowheads point to the initial site of wounding, while black arrowheads point to the wound edge of the migrating epithelial tongue. Scale bars, 500 μm. Graphs represent summarized migration rates; error bars correspond to SD from 18 biological samples from 6 independent experiments with 3 technical replicates. ***p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA.

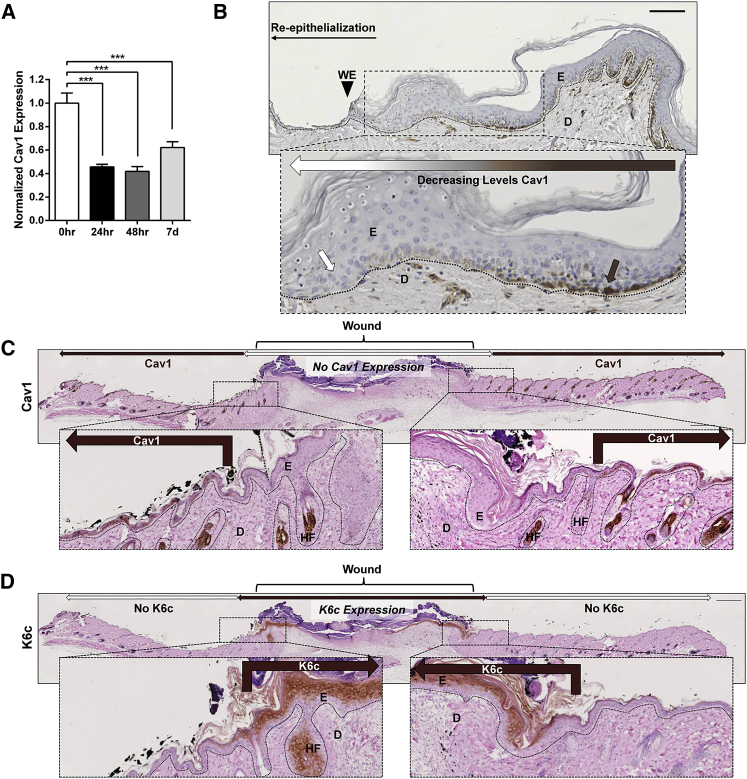

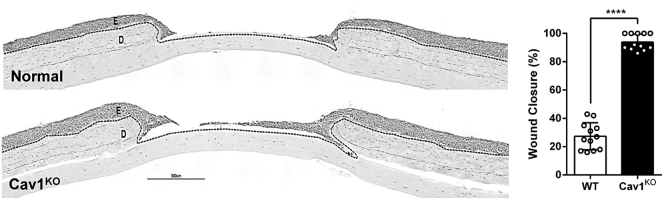

To establish an expression pattern of Cav1 in human skin wounds, we used a well-established human ex vivo model.6, 39 qPCR analysis of Cav1 expression during acute wound healing showed that Cav1 expression is significantly reduced during the first 48 h of wound healing, which starts to recover by day 7 (Figure 5A). Furthermore, histological assessment of ex vivo human skin 48 h after wounding shows a substantial decrease in Cav1. Interestingly, Cav1 is almost completely absent from the migrating epithelial tongue, thereby suggesting a negative role for Cav1 during keratinocyte migration and re-epithelialization (Figure 5B). Moreover, we induced full-thickness excisional wounds on the dorsal skin of C57BL/6 mice, harvested the skin 6 days later, and performed immunoperoxidase staining to confirm the expression and localization of Cav1 in vivo. We observed results similar to those found with an human ex vivo wound model, where Cav1 was primarily localized to the basement membrane of the epidermis away from the wound edge and absent in the re-epithelializing skin (Figure 5C). To ensure that the area that was void of Cav1 expression was, indeed, the re-epithelializing tissue, we performed immunofluorescence co-staining of Cav1 with cytokeratin-6c (K6c), a well-established marker of re-epithelialization.2, 40, 41 There was no co-localization of Cav1 and K6c (Figure 5D), confirming that Cav1 is downregulated during re-epithelialization and, thus, emphasizing the importance of its absence during epidermal wound healing. To provide further evidence that downregulation of Cav1 promotes wound closure, we generated 3D skin organotypic cultures,42, 43, 44 using normal foot fibroblasts in combination with either normal or Cav1KO human keratinocytes, wounded them, and assessed wound closure by histomorphometric analyses. As expected, we observed that Cav1 knockdown accelerated wound closure (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Cav1 Expression Is Spatiotemporally Downregulated in Both Human Ex Vivo and Mouse In Vivo Wounds

(A and B) Healthy human skin was wounded and maintained at the air-liquid interface for 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 96 h, and 7 days prior to assessment of Cav1 expression by (A) qPCR and (B) immunohistochemistry from 15 biological specimens from 5 independent experiments with 3 technical replicates. ***p ≤ 0.001, Student t test. Brown arrows point to expression of Cav1 in normal skin away from the wound, while white arrows indicate absence of Cav1 at the wound edge of the migrating epithelial tongue ex vivo. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Cav1 expression assessed by immunohistochemistry in murine excisional wounds 6 days post-wounding. White double arrows indicate wound area, brown arrows point to expression of Cav1 in skin away from the wound, while white arrows indicate absence of Cav1 from the wound edge of the migrating epithelial tongue in vivo. Bottom panel represents enlargement of the wound edge area. (D) Cytokeratin 6c (K6c) was used as a marker for migrating keratinocytes of the newly formed epidermis in murine excisional wounds; bottom panel represents enlargement of the wound edge area; dashed lines demarcate epidermal-dermal boundary. E, epidermis; D, dermis WE, wound edge; HF, hair follicle; n = 6. Scale bar, 500 μm.

Figure 6.

Cav1 Knockdown Accelerates Wound Closure in Human Skin Equivalents

Control and Cav1KO organotypic skin was wounded, and wound closure was quantified by histomorphometric analyses; dashed lines demarcate epidermal-dermal boundary. Scale bar, 500 μm. Graph represents quantification of wound closure; ****p ≤ 0.0001, pairwise Student’s t test, 12 biological samples from 3 independent experiments with 4 technical replicates, two tailed. E, epidermis; D, dermis.

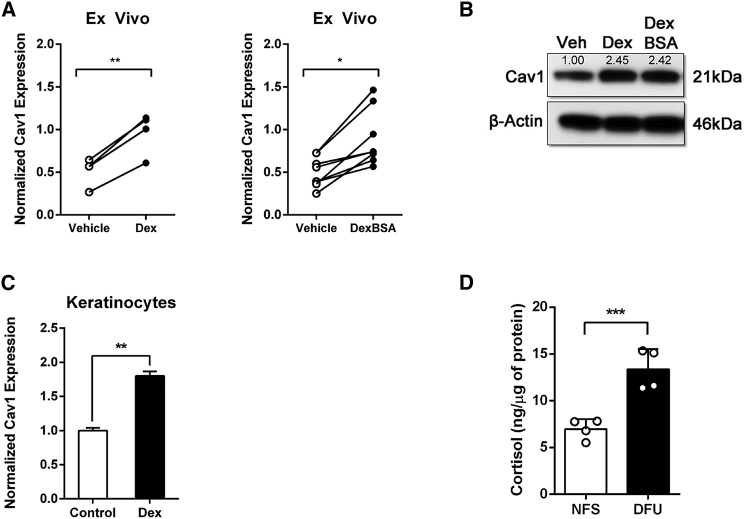

Increased Cortisol Levels in Chronic Wounds Contribute to Elevated Levels of Cav1 in Human Skin

Although GCs have long been known to inhibit wound healing,6, 36, 45, 46 we wanted to ascertain whether GCs affect expression of Cav1. To test this hypothesis, we treated human ex vivo skin with GCs (either Dex or Dex-BSA) and compared the relative levels of Cav1 to vehicle control (DMSO)-treated skin by qRT-PCR and western blotting. We observed a statistically significant induction of Cav1 expression upon Dex or Dex-BSA treatment on both the mRNA (Figure 7A) and protein (Figure 7B) levels. To validate that the observed induction of Cav1 was, indeed, coming from the epidermis, we treated human keratinocytes with Dex and assayed the expression of Cav1 by qRT-PCR. As expected, we saw that Dex stimulated the expression of Cav1 in human keratinocytes (Figure 7C). In order to establish that elevated GC levels are physiologically relevant, we measured cortisol levels (by ELISA) in non-healing edges of DFU specimens and compared them to normal skin. We observed a statistically significant increase in levels of cortisol in tissues from non-healing edges of DFUs when compared to normal healthy skin (Figure 7D). Together, these data led us to conclude that elevated GC levels in DFUs contribute to inhibition of wound closure, at least in part, by stimulating expression of Cav1.

Figure 7.

Induction of Cav1 Contributes to Inhibition of Healing in Human Skin

(A and B) Ex vivo human wounds were treated daily with 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex) or Dex-BSA, after which relative expression of Cav1 was determined by (A) qRT-PCR (pairwise Student’s t test from 4 [for Dex-treated skin] or 8 [for Dex-BSA-treated skin] biological samples; *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01, two tailed) and (B) western blotting. (C) Human keratinocyte HaCaT cells were treated with 1 μM Dex for 48 h, and levels of Cav1 were determined by qRT-PCR (t test from 3 independent experiments each consisting of 3 technical replicates; **p ≤ 0.01, two tailed). (D) Cortisol levels of 4 normal skin and 4 diabetic foot ulcer wounds were measured by ELISA normalized by micrograms of tissue (***p ≤ 0.001, t test, two tailed).

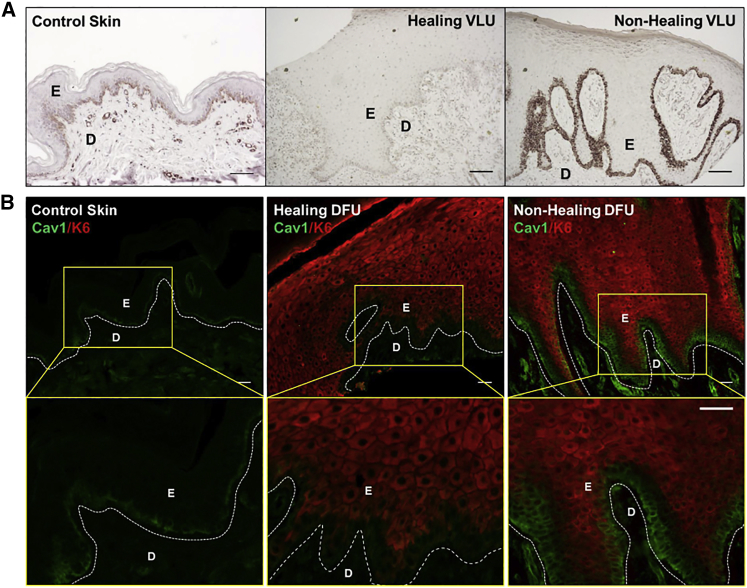

Cav1 Expression Is Upregulated in Non-healing Chronic Wounds in Relation to Clinical Outcome

Since we observed that Cav1 expression is downregulated at the migrating tongue of human skin ex vivo acute wounds (Figures 5A and 5B), and because increased levels of cortisol synthesis lead to increased levels of Cav1 (Figure 7), we expected that Cav1 expression should also be deregulated in chronic wounds and, thus, can contribute to non-healing outcomes. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated Cav1 expression in non-healing chronic wound edges in tissue biopsies obtained from patients. Cav1 expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry in biopsies obtained from non-healing VLUs and then compared to relative expression and localization of both healing VLUs and location-matched healthy skin. VLUs were stratified based on their healing outcomes using surrogate clinical endpoints.47 Briefly, patients with VLUs were treated with the standard of care compression therapy with non-healers defined as those whose ulcer size did not decrease by more than 40% after compression therapy over 4 weeks.47 Cav1 expression in VLUs negatively correlated with healing outcome. In healing VLUs, Cav1 expression at the basement membrane was downregulated overall in comparison to control skin (Figure 8A), consistent with the notion of shifting a chronic non-healing wound into an acutely healing wound.1, 47 Conversely, in non-healing VLUs, Cav1 was strikingly upregulated. Although predominantly localized to basement membrane in control skin and healing VLUs, in non-healing VLUs, Cav1 was detected beyond this single layer (Figure 8A). Furthermore, the assessment of Cav1 expression in DFUs showed similar results: healing DFUs exhibited decreased expression on Cav1, while non-healing DFUs exhibited increased expression of Cav1 (Figure 8B). We also observed differences in Cav1 localization in non-healing DFUs. The basal epidermal layer of non-healing DFUs showed strong Cav1 expression that was devoid of any K6c staining. In the few immediate suprabasal layers of keratinocytes, we observed Cav1-K6c co-localization. The more exterior epidermal keratinocytes were K6c positive and Cav1 negative (Figure 8B). Thus, we conclude that Cav1 is upregulated in the non-healing tissue of two types of chronic wounds, DFUs and VLUs, and could potentially serve as a universal indicator of non-healing clinical outcome.

Figure 8.

Cav1 Expression Is Upregulated in Chronic Wound Epidermis, and Its Levels Correlate with Clinical Outcomes of Healing

(A and B) Location-matched control skin as well as healing/non-healing (A) VLU and (B) DFU skin were subjected to Cav1 peroxidase or immunofluorescence staining. Healing outcome of VLUs and DFUs was determined based on wound size monitored over 4 weeks.72, 73 D, dermis; E, epidermis. Scale bars, 200 μm.

With these data taken together, we can summarize that Cav1 has a dual function in mechanisms that inhibit keratinocyte migration and wound closure: by associating with mbGR, Cav1 permits the GC-mediated inhibitory signal, and by sequestering EGFR, Cav1 blocks its pro-migratory signals. Because Cav1 contributes to the inhibition of healing via multiple mechanisms, it is a very attractive target for potential therapeutic interventions. This is further supported by genetic targeting and pharmacologic inhibition data that show that disruption of caveolae or knockdown of Cav1 accelerates epithelialization and wound closure in pre-clinical models.

Discussion

Here, we show a novel mechanism by which Cav1 mediates membrane compartmentalization of major signaling that control keratinocyte migration and subsequent cutaneous wound healing. We provide evidence for spatiotemporal downregulation of Cav1 during acute wound healing, whereby Cav1 expression is almost absent from keratinocytes at the migrating tongue of healing epithelium, suggesting that its absence is critical for successful wound healing. Importantly, Cav1 is found upregulated in patients with two different types of chronic ulcers, DFUs and VLUs. Indeed, its induction is specific for non-healing chronic ulcers, whereas Cav1 is found downregulated in healing ulcers, consistent with its absence in healing acute human and murine wounds. Although different in etiology and pathology, DFUs and VLUs may share mechanisms that contribute to the inhibition of healing.36 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first mechanism identified in pathophysiology of the non-healing phenotype of both DFUs and VLUs. The Cav1-mediated inhibition of healing can be attributed to two different signaling mechanisms. The Cav1 protein complex with either mbGR or EGFR contributes to major signaling events that result in the inhibition of keratinocyte migration and wound healing. Conversely, disruption of Cav1 complexes by either pharamacologic approach using MβCD or genetic KO rescues this inhibition. Together, these data underscore the role of Cav1 and its importance in membrane organization as a key mediator of cellular migration and wound closure, revealing an excellent potential therapeutic target.

Recently, Yang et al. demonstrated that overexpression of Cav1 in epidermal stem cells promoted wound healing in a rat burn model,48 demonstrating cell-specific effects of Cav1 during cutaneous wound healing. The study focused on different type of wound and model system (rat burn wound model) and found that increased rate of cell proliferation contributed to faster wound healing. Interestingly, one of the hallmarks of chronic, non-healing wounds in patients is hyper-proliferation due to loss of quiescence of epidermal stem cells.1, 2, 4, 37, 49, 50 We concede that overexpression of Cav1 was, indeed, found in this hyper-proliferative epidermis, which is similar to what Yang et al. found. Several factors (human versus mouse) can contribute to different outcomes: for instance, burns use different mechanisms to achieve successful wound closure. Apart from the obvious anatomical differences in rodent versus human skin, it is widely accepted that rodent skin heals by contraction (due to the presence of extensive subcutaneous muscle, panniculus carnosus, that is mainly absent from humans), whereas human skin heals by re-epithelialization. Cav1 has long been established as a mediator of mechanotransduction,51, 52, 53 suggesting that Cav1 may potentiate wound contraction in this model. Furthermore, many lines of evidence point to Cav1 exhibiting both anti-differentiation and anti-proliferative effects in various stem cells, which thus argues for very complex signaling arising from different stem cells. Thus the role of Cav1 in epidermal stem cells and its involvement in cutaneous wound healing will require further elucidation. Recently, the downregulation of Cav1 has been shown to potentiate EGFR signaling and cell migration, as well as wound closure, in a corneal epithelial model of wound healing,35 which further supports our findings presented in this paper. Interestingly, it also lends support to the notion that Cav1 may tightly regulate cell migration and wound closure in multiple cells of epithelial origin and, thus, argues for an evolutionarily conserved pathway where Cav1 may need to be spatiotemporally downregulated in order to potentiate EGFR signaling, directional cell migration, and subsequent wound closure. All these different effects underscore the role of Cav 1 and its importance in tissue- and cell-specific targeting in the context of wound healing. Furthermore, type of the model(s) and species-specific differences should always be taken into consideration.

Identification of this unique mechanism by which mbGR mediates cellular functions places Cav1 in a central role in mediating membranous GC signaling. In lieu of our recent discovery that GCs replicate the Wnt-like pathway,6 the data presented here further provide additional opportunity for fine-tuning these major stress signals and emphasize the role of Cav1 in tissue homeostasis. Since skin is the site of the extra-hepatic cholesterol synthesis and extra-adrenal site for cortisol synthesis,54, 55, 56 modulation of cholesterol and cortisol production can directly affect Cav1 and its control of wound closure. For example, it has been shown that free cholesterol upregulates Cav1 mRNA (via two sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-binding elements located in the Cav1 promoter region) and stabilizes Cav1 protein.57 Furthermore, both local and systemic stress signals, in the form of GCs, can also influence reorganization of signaling molecules at the plasma membrane microdomains by coordinating their localization to caveolae and association with Cav1. As we show here, activation of mbGR by Dex-BSA leads to its association with Cav1 within caveolae and further compartmentalization of various signal transduction molecules. Furthermore, disruption of caveolae by MβCD in the absence of mbGR also stimulates wound closure, which can contribute to the modulation of endogenous cortisol-mbGR activity.

Cav1 can orchestrate transmembrane signaling events and allow for cross-talk between various downstream effectors, thereby either sequestering certain proteins from their normal function (such as EGFR) or bringing other molecules in close enough proximity to interact that otherwise would not (such as mbGR/PLCγ/PKC). These regulatory mechanisms underscore the role of caveolae and Cav1 in mediating signaling events that are important for the control of wound healing. Consistent with human ex vivo organotypic 3D skin cultures and mouse in vivo wound expression data, the presence of Cav1 in epidermis mediates inhibition of healing in patients’ samples from chronic ulcers.

Another very interesting finding is that mbGR activation results in differential regulation of PKC isoenzymes in a caveolae-dependent manner; i.e., it can be disrupted by MβCD or by loss of Cav1 (Cav1KO). Considering the relative abundance of PKC isoenzymes in various tissues and their roles in cell survival, proliferation, migration, and differentiation, our identification that mbGR activation results in differential regulation of PKC isoenzymes in a caveolae-dependent manner is intriguing. Atypical PKCs (ζ and λ/ι) are activated independently of diacylglycerol (DAG) and Ca2+ but can be regulated by phosphatidylserine (PS). PKCζ, the only atypical isoenzyme expressed in keratinocytes, is required for migration and invasion of multiple cancer cell types and essential for EGF-induced chemotaxis of breast and lung cancer cell lines.58 This is in line with our observation that Dex-BSA leads to the suppression of PKCζ, whereas caveolae disruption or Cav1KO rescues the mbGR-mediated suppression to promote the migration of keratinocytes.

Alternatively, novel PKCs (δ, ε, η, and θ) are activated by DAG and PS but are insensitive to Ca2+ and have been shown to stimulate keratinocyte differentiation, with PKCδ serving as the most potent activator.59 Our observation that caveolae disruption or Cav1KO can reverse PKCδ activation is also very plausible, since it has been previously shown that PKCδ can translocate to caveolin-enriched microdomains to negatively regulate EGF-mediated PLD1/PKCα activity.60 In dermal fibroblasts, PKCδ overexpression inhibits wound healing, while inhibition of PKCδ improves fibroblast response to insulin and VEGF. Furthermore, depletion of PKCδ from diabetic fibroblasts significantly improves fibroblast function, resulting in improved granulation tissue formation, angiogenesis, and wound healing.61 Taken together, our findings that mbGR can modulate such complex signaling network via Cav1 provide new insights into multiple treatment paradigms.

It was previously shown that Cav1 can sequester and modulate EGFR activation of downstream signaling.62, 63, 64 Our previous studies have shown downregulation and mis-localization of EGFR in chronic wounds.36, 37 Here, we provide the first evidence of a novel mechanism linking deregulated EGFR activity in chronic wounds to increased levels of Cav1 that antagonizes EGFR phosphorylation and downstream signaling necessary for proper keratinocyte proliferation and migration. Although recombinant human EGF (rhEGF) therapy has shown promise in promoting healing of primarily DFUs,65, 66, 67, 68 it failed to achieve US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in the United States.38 Furthermore, rhEGF did not significantly enhance re-epithelialization of VLUs, possibly due to upregulation of Cav1 at the wound edge of VLUs. Conversely, we have previously shown that EGFR is downregulated and mis-localized to the cytoplasm in pre-debridement, whereas it is normalized in post-debridement specimens.37

In conclusion, we identified a novel mechanism by which Cav1 orchestrates GC-mediated signaling events involved in the control of cutaneous wound healing. Consequently, this leads to the inhibition of keratinocyte migration and wound closure, which can be rescued either by using MβCD to disrupt caveolae or by inhibiting Cav1 expression. Furthermore, aberrant overexpression of Cav1 in two non-healing chronic wounds, DFUs and VLUs, emphasizes the importance of membrane organization as a key mediator of cellular migration and subsequent re-epithelialization. Taken together, our findings provide a new therapeutic approach to stimulate wound healing via disruption of caveolae.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Antibodies for immunoblots were used as follows: GR (1:1,000; Cell Signaling, #3660); phospho-GRS211 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4161); β-actin (1:10,000, Sigma, #A5441); PLCγ1 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #2822); phospho-PLCγ1Y783 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #14008); phospho-EGFRY1173 (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #sc-12351); phospho-EGFRY1068 (1:500, Abcam, #ab32430); phospho-EGFRT654 (1:250, Abcam, #ab78283); EGFR (1:1,000, Santa Cruz, #sc-03); cRaf (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9422); phospho-cRafS338 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9427); MEK1/2 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #8727); phospho-MEK1/2S217/221 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9154); Erk1/2 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4695); phospho-Erk1/2T202/Y204 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4370); p90RSK (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9355); phospho-p90RSKS380 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #11989); Arpc2 (1:2,000, Abcam, #ab133315); PKC δ (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9616); phospho-PKC δT505 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, #9374); PKC ζ/λ (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9368); phospho-PKC ζ/λT410/T403 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, #9378); anti-rabbit IgG (immunoglobulin G), HRP (horseradish peroxidase) (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #7074); and anti-mouse IgG, HRP (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #7076). The antibody for co-immunoprecipitation was Cav1 (BD Biosciences, #610407). Antibodies for immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence were Cav1 (1:100, Sigma, #HPA049326) and Cytokeratin 6C (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #MA1-35561).

Cell Culture

Primary adult human epidermal keratinocytes (HEKs) were grown as previously described.3 Briefly, keratinocytes were obtained from the Living Skin Bank (Burn Center at Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, NY, USA) and grown in a serum-free keratinocyte growth medium (KSFM; GIBCO #10724-011, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 0.2 ng/mL EGF, 25 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. Third-passage cells were used at 60%–70% confluency. Keratinocytes, grown on 60-mm plates (Greiner Bio-One, #628160, Frickenhausen, Germany), were then starved overnight with custom basal keratinocyte medium (Basal KSFM without phenol red, T3, hydrocortisone, insulin, and L-glutamine; GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA) prior to treatment with ±2% (w/v) MβCD (Sigma # F4767, St Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h and then stimulated with ±100 nM Dex-BSA (Steraloids, Newport, RI, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was cut in 7-μm sections, deparaffinized with xylene (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ, USA), and rehydrated in graded ethanol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol. The slides were then incubated in sodium citrate (0.05% Tween) solution for 30 min at 95°C for antigen retrieval, allowed to cool down, and then treated with Background Punisher (MACH 1 Kkit, Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA). Rabbit anti-Cav1 antibodies (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, catalog #HPA049326) and mouse anti-keratin 6c (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #MA1-35561) were applied to the samples for overnight incubation at 4°C. The detection and chromogenic reaction were carried out using the Betazoid DAB Chromagen Kit (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA, #BDB2004H), and slides were counterstained using Harris Hematoxylin (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

qPCR

RNA isolation and purification were performed as previously described.69 1.0 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed using a qScript cDNA Kit (QuantaBio, Beverly, MA, USA), and real-time PCR was performed in triplicates using the Bio-Rad CFX Connect Thermal Cycler and Detection System and the PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix (QuantaBio, Beverly, MA, USA). Relative expression was normalized for levels of Arpc2. The primer sequences are as follows: Arpc2 forward primer, 5′-TCCGGGACTACCTGCACTAC-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-GGTTCAGCACCTTGAGGAAG-3′; Cav1 forward primer, 5′-GCGACCCTAAACACCTCAAC-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-ATGCCGTCAAAACTGTGTGTC-3′. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s t test.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Co-immunoprecipitation protocol was followed as previously described,70 with minor modifications using the Pierce Classic IP Kit (Thermo Scientific, #26149, Rockford, IL, USA). Pre-cleared cell lysate (400 μg) was incubated with 2 μg Cav1 antibody (BD Biosciences, #610407) immobilized on AminoLink Plus Coupling resin overnight at 4°C, after which the resin was washed extensively with lysis buffer, eluted, and solubilized in SDS sample loading buffer. Proteins were resolved by 4%–20% Criterion TGX pre-cast gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Thermo Scientific), and placed in blocking buffer for 1 h (Tris-buffered saline [TBS], 0.1% Tween 20, 5% BSA) and then probed with indicated antibodies overnight. To determine relative protein amounts, three representative exposures for each sample were quantified using ImageJ software.

CRISPR/Cas9 Cav1 KO

Cav1 CRISPR/Cas9 KO and Cav1 HDR plasmids (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) were used to generate Cav1 human keratinocyte KO cells. Briefly, 2 μg Cav1-CRISPR/Cas9 and Cav1-HDR plasmids were combined with antibiotic- and serum-free media containing FuGENE HD (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) transfection reagent and incubated for 48 h at 37°C before proceeding with puromycin selection for 5 days.

Wound Scratch Assay

Primary HEKs were used in a previously described wound scratch assay.6 Briefly, HEKs were grown to confluence in 96-well ImageLock plates (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), treated with 4 μg/mL mitomycin-C, and wounded by scratch with a 96-pin wound-making tool (WoundMaker, Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Cells were incubated for 48 h, and two representative images from each well of relative migration were taken every 2 h after the initial wounding, using the IncuCyte Zoom System (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and quantified using the Cell Migration Analysis software module (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

In Vivo Wounding

All animal care and use procedures were approved by the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Under anesthesia, hair on the dorsal skin of male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA), 8 weeks of age, was removed by clipping, and the skin was cleaned with antiseptics. Two excisional wounds, 8 mm × 6 mm, were created in the dorsal skin on both sides of the midline. Wound tissue was collected on day 6, fixed in 10% formalin, processed, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were stained with H&E for histological analysis and then immunostained for Cav1.

Ex Vivo Human Wound Model

Human skin specimens from reduction surgery were used to generate acute wounds as previously described.38, 39 Briefly, a 3-mm biopsy punch was used to create acute wounds (n = 9 per treatment), which were treated daily with or without 1 μM Dex, 0.1 μM Dex-BSA, or 2% (w/v) MβCD, or a combination for 5 days. Ex vivo acute wound specimens were paraffin embedded, and rate of healing was analyzed for epithelialization by histology assessment using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope and NIS Elements software.

Organotypic Cultures

A fibroblast-collagen matrix was constructed using adult human primary dermal fibroblasts and type I collagen from bovine origin (Advanced BioMatrix, Carlsbad, CA, USA).42, 43, 44 Briefly, 1 mL acellular collagen matrix was poured into polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membrane inserts (Greiner Bio-One North America, Monroe, NC, USA) placed in 6-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and allowed to gel at 37°C for 20 min. 2.5 mL cellular matrix containing the fibroblasts was added on top of the gellified acellular matrix and incubated at 37°C for 30 min before adding organotypic culture medium (FAD medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 10−10 M cholera toxin, 0.4 μg/mL hydrocortisone per milliliter, and 50 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid).36 The submerged matrices were incubated overnight at 37°C. The next day, the media were removed from the matrices, and 106 HaCaT (normal or Cav1KO) cells per insert were added on top of each matrix. The cells were allowed to attach at 37°C for 30–60 min, and then the cultures were submerged into organotypic culture medium supplemented with 2 ng/mL EGF and incubated overnight at 37°C before raising them to the air-liquid interface. Medium was replaced every 2 days for 20 days. Wounds were created as described earlier. The wounds were treated daily for 2 days, collected, and fixed in formalin for histological assessment.

Cortisol ELISA

Human skin specimens were obtained as described earlier. 1-cm square templates of skin were generated using a scalpel and incubated in customized basal media. Medium was collected after 6 h. Skin specimens were weighted before experiment, and cortisol production was normalized per gram of tissue. Cortisol levels in media (harvested from cultured skin) were measured using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems) following commercial protocol.71 Cortisol concentration in media samples was normalized to the gram of tissue. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t test.

Statistics

Results from quantitative experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA, or pairwise two-sided Student’s t test as indicated in each figure legend (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001).

Study Approval

Control healthy human skin specimens were obtained as discarded tissue from reduction surgery procedures in accordance with institutional approvals as previously described.6 Specifically, protocol to obtain unidentified skin specimens was submitted to the University of Miami Human Subject Research Office (HSRO). Upon review conducted by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board (IRB), it was determined that such protocol does not constitute Human Subject Research per 45 CFR 46.101.2. Chronic wound samples were obtained from consenting patients receiving standard care at the University of Miami Hospital. These protocols were approved by the IRB (protocols #20150912, #20150222, #20090709, and #27085). Ulcers did not exhibit any clinical signs of infection. Chronic wound tissue was stored in RNALater (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for subsequent RNA isolation, snap frozen for protein isolation, or fixed in formalin.

Author Contributions

I.J. and M.T.-C. designed experiments, obtained funding, and analyzed and interpreted the data; experiments were carried out by I.J., A.P.S., G.D.G., C.R.H., L.L.W., I.P., and T.C.W.; T.C.W., I.P., H.B., and R.S.K. contributed reagents; I.J. and M.T.-C. participated in writing the manuscript and composing the figures. All authors reviewed and approved submission of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Anthony Barrientos, Gregory Plano, Marcia Boulina, Camillo Ricordi, and Marta Garcia-Contreras for their generosity in sharing laboratory equipment. We are also grateful to all members of the M.T.-C. laboratory for overall support and critical evaluation of the manuscript. This work was funded in part by a 3M Healthcare fellowship granted by the Wound Healing Foundation; a PhRMA Foundation research starter grant; a Medline Wound Healing Foundation innovation grant (to I.J.); grant SAC-2013-19 (to M.T.-C.); grants NR015649, NR013881, and 1R01AR073614 (to M.T.-C.); and the University of Miami Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery University of Miami Skin Diseases Research Core Center (UMSDRCC).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.07.016.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Eming S.A., Martin P., Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:265sr6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastar I., Stojadinovic O., Yin N.C., Ramirez H., Nusbaum A.G., Sawaya A., Patel S.B., Khalid L., Isseroff R.R., Tomic-Canic M. Epithelialization in wound healing: a comprehensive review. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014;3:445–464. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastar I., Wong L.L., Egger A.N., Tomic-Canic M. Descriptive vs mechanistic scientific approach to study wound healing and its inhibition: is there a value of translational research involving human subjects? Exp. Dermatol. 2018;27:551–562. doi: 10.1111/exd.13663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stojadinovic O., Brem H., Vouthounis C., Lee B., Fallon J., Stallcup M., Merchant A., Galiano R.D., Tomic-Canic M. Molecular pathogenesis of chronic wounds: the role of beta-catenin and c-myc in the inhibition of epithelialization and wound healing. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62953-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vukelic S., Stojadinovic O., Pastar I., Vouthounis C., Krzyzanowska A., Das S., Samuels H.H., Tomic-Canic M. Farnesyl pyrophosphate inhibits epithelialization and wound healing through the glucocorticoid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:1980–1988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jozic I., Vukelic S., Stojadinovic O., Liang L., Ramirez H.A., Pastar I., Tomic-Canic M. Stress signals, mediated by membranous glucocorticoid receptor, activate PLC/PKC/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin pathway to inhibit wound closure. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2017;137:1144–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasricha N., Joëls M., Karst H. Rapid effects of corticosterone in the mouse dentate gyrus via a nongenomic pathway. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:143–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strehl C., Gaber T., Löwenberg M., Hommes D.W., Verhaar A.P., Schellmann S., Hahne M., Fangradt M., Wagegg M., Hoff P. Origin and functional activity of the membrane-bound glucocorticoid receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3779–3788. doi: 10.1002/art.30637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samarasinghe R.A., Witchell S.F., DeFranco D.B. Cooperativity and complementarity: synergies in non-classical and classical glucocorticoid signaling. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2819–2827. doi: 10.4161/cc.21018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haller J., Mikics E., Makara G.B. The effects of non-genomic glucocorticoid mechanisms on bodily functions and the central neural system. A critical evaluation of findings. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:273–291. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vernocchi S., Battello N., Schmitz S., Revets D., Billing A.M., Turner J.D., Muller C.P. Membrane glucocorticoid receptor activation induces proteomic changes aligning with classical glucocorticoid effects. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2013;12:1764–1779. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.022947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu M.L., Schneider M.C., Zheng Y., Zhang X., Richie J.P. Caveolin-1 interacts with androgen receptor. A positive modulator of androgen receptor mediated transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13442–13451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlegel A., Wang C., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P. Ligand-independent activation of oestrogen receptor alpha by caveolin-1. Biochem. J. 2001;359:203–210. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lisanti M.P., Scherer P.E., Tang Z., Sargiacomo M. Caveolae, caveolin and caveolin-rich membrane domains: a signalling hypothesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:231–235. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W., Razani B., Altschuler Y., Bouzahzah B., Mostov K.E., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 inhibits epidermal growth factor-stimulated lamellipod extension and cell migration in metastatic mammary adenocarcinoma cells (MTLn3). Transformation suppressor effects of adenovirus-mediated gene delivery of caveolin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:20717–20725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909895199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Razani B., Woodman S.E., Lisanti M.P. Caveolae: from cell biology to animal physiology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:431–467. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sando G.N., Zhu H., Weis J.M., Richman J.T., Wertz P.W., Madison K.C. Caveolin expression and localization in human keratinocytes suggest a role in lamellar granule biogenesis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;120:531–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barar J., Campbell L., Hollins A.J., Thomas N.P., Smith M.W., Morris C.J., Gumbleton M. Cell selective glucocorticoid induction of caveolin-1 and caveolae in differentiating pulmonary alveolar epithelial cell cultures. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;359:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Igarashi J., Hashimoto T., Shoji K., Yoneda K., Tsukamoto I., Moriue T., Kubota Y., Kosaka H. Dexamethasone induces caveolin-1 in vascular endothelial cells: implications for attenuated responses to VEGF. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C790–C800. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00268.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park D.S., Razani B., Lasorella A., Schreiber-Agus N., Pestell R.G., Iavarone A., Lisanti M.P. Evidence that Myc isoforms transcriptionally repress caveolin-1 gene expression via an INR-dependent mechanism. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3354–3362. doi: 10.1021/bi002787b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capozza F., Williams T.M., Schubert W., McClain S., Bouzahzah B., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Absence of caveolin-1 sensitizes mouse skin to carcinogen-induced epidermal hyperplasia and tumor formation. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;162:2029–2039. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64335-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Del Galdo F., Lisanti M.P., Jimenez S.A. Caveolin-1, transforming growth factor-beta receptor internalization, and the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2008;20:713–719. doi: 10.1097/bor.0b013e3283103d27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castello-Cros R., Whitaker-Menezes D., Molchansky A., Purkins G., Soslowsky L.J., Beason D.P., Sotgia F., Iozzo R.V., Lisanti M.P. Scleroderma-like properties of skin from caveolin-1-deficient mice: implications for new treatment strategies in patients with fibrosis and systemic sclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2140–2150. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.13.16227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gálvez B.G., Matías-Román S., Yáñez-Mó M., Vicente-Manzanares M., Sánchez-Madrid F., Arroyo A.G. Caveolae are a novel pathway for membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase traffic in human endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:678–687. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge S., Pachter J.S. Caveolin-1 knockdown by small interfering RNA suppresses responses to the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by human astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:6688–6695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez E., Nagiel A., Lin A.J., Golan D.E., Michel T. Small interfering RNA-mediated down-regulation of caveolin-1 differentially modulates signaling pathways in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:40659–40669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podar K., Shringarpure R., Tai Y.T., Simoncini M., Sattler M., Ishitsuka K., Richardson P.G., Hideshima T., Chauhan D., Anderson K.C. Caveolin-1 is required for vascular endothelial growth factor-triggered multiple myeloma cell migration and is targeted by bortezomib. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7500–7506. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grande-García A., Echarri A., de Rooij J., Alderson N.B., Waterman-Storer C.M., Valdivielso J.M., del Pozo M.A. Caveolin-1 regulates cell polarization and directional migration through Src kinase and Rho GTPases. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:683–694. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valle B.C., Billiot F.H., Shamsi S.A., Zhu X., Powe A.M., Warner I.M. Combination of cyclodextrins and polymeric surfactants for chiral separations. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:743–752. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodal S.K., Skretting G., Garred O., Vilhardt F., van Deurs B., Sandvig K. Extraction of cholesterol with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin perturbs formation of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:961–974. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez S.A., Gunther G., Tricerri M.A., Gratton E. Methyl-β-cyclodextrins preferentially remove cholesterol from the liquid disordered phase in giant unilamellar vesicles. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;241:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Caveolae and signalling in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:225–237. doi: 10.1038/nrc3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchis A., Bayo P., Sevilla L.M., Pérez P. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonizes EGFR function to regulate eyelid development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2010;54:1473–1480. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103071as. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauriola M., Enuka Y., Zeisel A., D’Uva G., Roth L., Sharon-Sevilla M., Lindzen M., Sharma K., Nevo N., Feldman M. Diurnal suppression of EGFR signalling by glucocorticoids and implications for tumour progression and treatment. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5073. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang C., Su X., Bellner L., Lin D.H. Caveolin-1 regulates corneal wound healing by modulating Kir4.1 activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2016;310:C993–C1000. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00023.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee B., Vouthounis C., Stojadinovic O., Brem H., Im M., Tomic-Canic M. From an enhanceosome to a repressosome: molecular antagonism between glucocorticoids and EGF leads to inhibition of wound healing. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:1083–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brem H., Stojadinovic O., Diegelmann R.F., Entero H., Lee B., Pastar I., Golinko M., Rosenberg H., Tomic-Canic M. Molecular markers in patients with chronic wounds to guide surgical debridement. Mol. Med. 2007;13:30–39. doi: 10.2119/2006-00054.Brem. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ojeh N., Stojadinovic O., Pastar I., Sawaya A., Yin N., Tomic-Canic M. The effects of caffeine on wound healing. Int. Wound J. 2016;13:605–613. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stojadinovic O., Tomic-Canic M. Human ex vivo wound healing model. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1037:255–264. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-505-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mansbridge J.N., Knapp A.M. Changes in keratinocyte maturation during wound healing. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1987;89:253–263. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12471216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazzalupo S., Wong P., Martin P., Coulombe P.A. Role for keratins 6 and 17 during wound closure in embryonic mouse skin. Dev. Dyn. 2003;226:356–365. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlson M.W., Alt-Holland A., Egles C., Garlick J.A. Three-dimensional tissue models of normal and diseased skin. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2008;41:19.9.1–19.9.17. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1909s41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maas-Szabowski N., Stärker A., Fusenig N.E. Epidermal tissue regeneration and stromal interaction in HaCaT cells is initiated by TGF-alpha. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2937–2948. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stark H.J., Baur M., Breitkreutz D., Mirancea N., Fusenig N.E. Organotypic keratinocyte cocultures in defined medium with regular epidermal morphogenesis and differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1999;112:681–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beer H.D., Fässler R., Werner S. Glucocorticoid-regulated gene expression during cutaneous wound repair. Vitam. Horm. 2000;59:217–239. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(00)59008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slominski A.T., Zmijewski M.A. Glucocorticoids inhibit wound healing: novel mechanism of action. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2017;137:1012–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stone R.C., Stojadinovic O., Rosa A.M., Ramirez H.A., Badiavas E., Blumenberg M., Tomic-Canic M. A bioengineered living cell construct activates an acute wound healing response in venous leg ulcers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaaf8611. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang R., Wang J., Zhou Z., Qi S., Ruan S., Lin Z., Xin Q., Lin Y., Chen X., Xie J. Role of caveolin-1 in epidermal stem cells during burn wound healing in rats. Dev. Biol. 2019;445:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falanga V. Classifications for wound bed preparation and stimulation of chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brem H., Tomic-Canic M. Cellular and molecular basis of wound healing in diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1219–1222. doi: 10.1172/JCI32169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rizzo V., Sung A., Oh P., Schnitzer J.E. Rapid mechanotransduction in situ at the luminal cell surface of vascular endothelium and its caveolae. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26323–26329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park H., Go Y.M., Darji R., Choi J.W., Lisanti M.P., Maland M.C., Jo H. Caveolin-1 regulates shear stress-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;278:H1285–H1293. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gvaramia D., Blaauboer M.E., Hanemaaijer R., Everts V. Role of caveolin-1 in fibrotic diseases. Matrix Biol. 2013;32:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slominski A., Wortsman J., Tuckey R.C., Paus R. Differential expression of HPA axis homolog in the skin. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2007;265-266:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vukelic S., Stojadinovic O., Pastar I., Rabach M., Krzyzanowska A., Lebrun E., Davis S.C., Resnik S., Brem H., Tomic-Canic M. Cortisol synthesis in epidermis is induced by IL-1 and tissue injury. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:10265–10275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.188268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slominski A.T., Manna P.R., Tuckey R.C. Cutaneous glucocorticosteroidogenesis: securing local homeostasis and the skin integrity. Exp. Dermatol. 2014;23:369–374. doi: 10.1111/exd.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fielding C.J., Bist A., Fielding P.E. Caveolin mRNA levels are up-regulated by free cholesterol and down-regulated by oxysterols in fibroblast monolayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:3753–3758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rimessi A., Zecchini E., Siviero R., Giorgi C., Leo S., Rizzuto R., Pinton P. The selective inhibition of nuclear PKCζ restores the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic agents in chemoresistant cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:1040–1048. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.5.19520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deucher A., Efimova T., Eckert R.L. Calcium-dependent involucrin expression is inversely regulated by protein kinase C (PKC)alpha and PKCdelta. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:17032–17040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han J.M., Kim Y., Lee J.S., Lee C.S., Lee B.D., Ohba M., Kuroki T., Suh P.G., Ryu S.H. Localization of phospholipase D1 to caveolin-enriched membrane via palmitoylation: implications for epidermal growth factor signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:3976–3988. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khamaisi M., Katagiri S., Keenan H., Park K., Maeda Y., Li Q., Qi W., Thomou T., Eschuk D., Tellechea A. PKCδ inhibition normalizes the wound-healing capacity of diabetic human fibroblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:837–853. doi: 10.1172/JCI82788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Razani B., Altschuler Y., Zhu L., Pestell R.G., Mostov K.E., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 expression is down-regulated in cells transformed by the human papilloma virus in a p53-dependent manner. Replacement of caveolin-1 expression suppresses HPV-mediated cell transformation. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13916–13924. doi: 10.1021/bi001489b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nixon S.J., Carter A., Wegner J., Ferguson C., Floetenmeyer M., Riches J., Key B., Westerfield M., Parton R.G. Caveolin-1 is required for lateral line neuromast and notochord development. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:2151–2161. doi: 10.1242/jcs.003830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Agelaki S., Spiliotaki M., Markomanolaki H., Kallergi G., Mavroudis D., Georgoulias V., Stournaras C. Caveolin-1 regulates EGFR signaling in MCF-7 breast cancer cells and enhances gefitinib-induced tumor cell inhibition. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009;8:1470–1477. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.15.8939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown G.L., Curtsinger L., Jurkiewicz M.J., Nahai F., Schultz G. Stimulation of healing of chronic wounds by epidermal growth factor. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1991;88:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Margolis D.J., Bartus C., Hoffstad O., Malay S., Berlin J.A. Effectiveness of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor for the treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:531–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2005.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Valenzuela-Silva C.M., Tuero-Iglesias A.D., García-Iglesias E., González-Díaz O., Del Río-Martín A., Yera Alos I.B., Fernández-Montequín J.I., López-Saura P.A. Granulation response and partial wound closure predict healing in clinical trials on advanced diabetes foot ulcers treated with recombinant human epidermal growth factor. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:210–215. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gomez-Villa R., Aguilar-Rebolledo F., Lozano-Platonoff A., Teran-Soto J.M., Fabian-Victoriano M.R., Kresch-Tronik N.S., Garrido-Espíndola X., Garcia-Solis A., Bondani-Guasti A., Bierzwinsky-Sneider G., Contreras-Ruiz J. Efficacy of intralesional recombinant human epidermal growth factor in diabetic foot ulcers in Mexican patients: a randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:497–503. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramirez H.A., Liang L., Pastar I., Rosa A.M., Stojadinovic O., Zwick T.G., Kirsner R.S., Maione A.G., Garlick J.A., Tomic-Canic M. Comparative genomic, microRNA, and tissue analyses reveal subtle differences between non-diabetic and diabetic foot skin. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jozic I., Saliba S.C., Barbieri M.A. Effect of EGF-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor on Rab5 function during endocytosis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;525:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slominski A., Zbytek B., Semak I., Sweatman T., Wortsman J. CRH stimulates POMC activity and corticosterone production in dermal fibroblasts. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005;162:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Margolis D.J., Gelfand J.M., Hoffstad O., Berlin J.A. Surrogate end points for the treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1696–1700. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gelfand J.M., Hoffstad O., Margolis D.J. Surrogate endpoints for the treatment of venous leg ulcers. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2002;119:1420–1425. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.