Abstract

Objectives

In the post-surgical setting, active involvement of family caregivers has the potential to improve patient outcomes by prevention of surgical complications that are sensitive to fundamental care. This paper describes the development of a theoretically grounded program to enhance the active involvement of family caregivers in fundamental care for post-surgical patients.

Methods

We used a quality improvement project following a multi-phase design. In Phase 1, an iterative method was used to combine evidence from a narrative review and professionals’ preferences. In Phase 2, the logic model underlying the program was developed guided by four steps: (1) confirm situation, intervention aim, and target population; (2) documented expected outcomes, and outputs of the intervention; (3) identify and describe assumptions, external factors and inputs; and (4) confirm intervention components.

Results

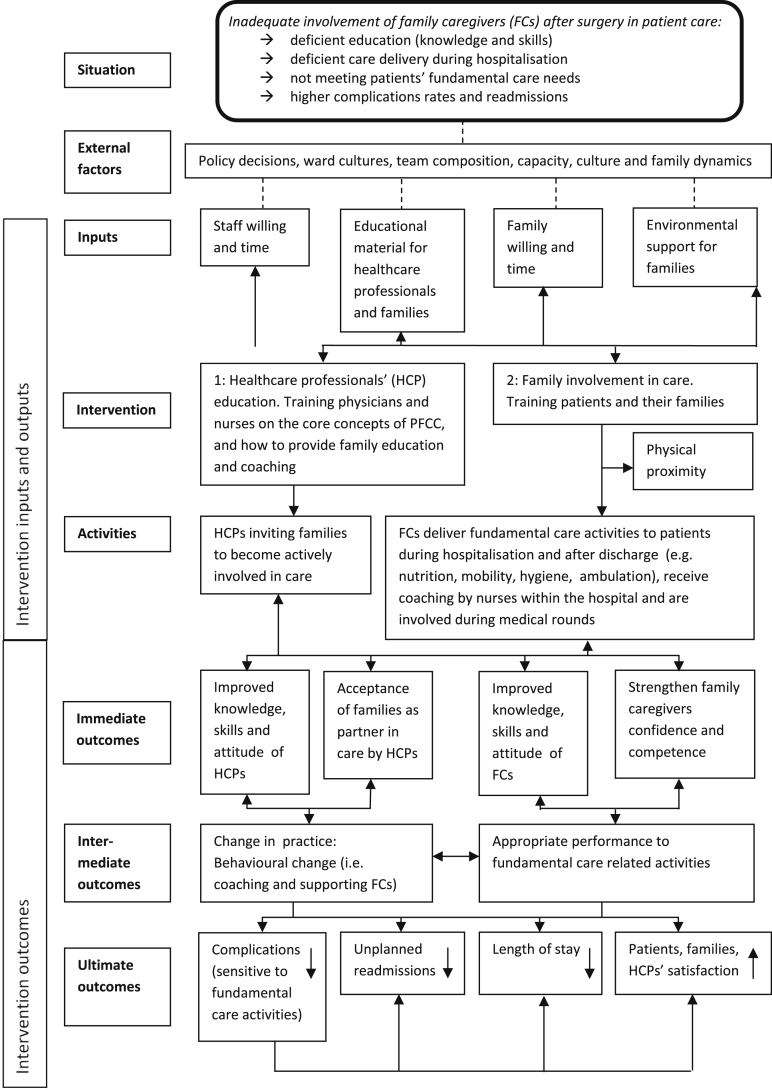

Phase 1 identified a minimum set of family involvement activities that were both supported by staff and the narrative review. In Phase 2, the logic model was developed and includes (1) the inputs (e.g. educational- and environmental support), (2) the ultimate outcomes (e.g. reduction of postoperative complications), (3) the intermediate outcomes (e.g. behavioural changes), and (4) immediate outcomes (e.g. improved knowledge, skills and attitude).

Conclusions

We demonstrated how we aimed to change our practice to an environment in which family caregivers were stimulated to be actively involved in postoperative care on surgical wards, and how we took different factors into account. The description of this program may provide a solid basis for professionals to implement the family involvement program in their own setting.

Keywords: Family caregivers, Hospital surgery department, Nursing care, Nursing models, Quality improvement

What is known?

Family involvement in care has been explored both conceptually and empirically, however there are less accounts of the underlying theoretical rationale for multi-component interventions aimed to improve family involvement in post-surgical patient care.

What is new?

This paper gives insight in the development of an evidence-based and theoretically grounded program to promote family involvement in fundamental care for patients after surgery. It shows how the family involvement program has the potential to influence outcomes on different levels, and improve quality of care. The logic model presented may help other hospitals to make attempts toward a more patient- and family centred environment.

1. Introduction

Attention to the delivery of patient- and family-centred care (PFCC) in hospital has increased in recent years. Family-centred care is more than the presence of family during hospitalisation; it includes family participation in all aspects of care delivery [1]. This participation requires a mutual partnership and collaboration among healthcare professionals, patients and their family caregivers in a way that promotes patient satisfaction and self-determination [2].

In the field of surgery, active involvement of family caregivers in fundamental care activities has the potential to improve health-related outcomes (e.g. quality of life (QoL), and discomfort) by prevention of surgical complications. This fundamental care, sometimes referred to as essential or basic care, reflects a diverse range of care processes that combine the physical, psychosocial and relational dimensions of care, traditionally delivered by nursing staff [3,4]. Poorly executed fundamental care threaten patient safety, quality of life, patient empowerment, functioning and satisfaction [3]. This results in higher numbers of complications and poor care experiences [3]. Families often act namely as primary caregivers after discharge, but feel often unprepared for this task and experience a lack of knowledge to deliver proper care [5]. Educating and training these family caregivers could improve the execution of fundamental care, and thereby reducing the risk of complications.

The incidence of complications is 2–4.5 times greater in surgery than in general medicine [6], and the consequences of surgical complications on patients' health can be severe [7]. Some surgical complications such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and delirium are believed to be potentially preventable [[8], [9], [10], [11]], and are sensitive to adequate fundamental care. Thus, meeting patients’ fundamental care needs in hospital care is crucial, especially when patients are not able to carry out these activities independently (e.g. eating, dressing, washing, mobilising, and oral hygiene) [3]. For that purpose, hospitalisation may provide a unique opportunity to actively stimulate family caregivers to collaborate in care. Family caregivers can learn new skills and knowledge under supervision and, coached by healthcare professionals, they may be motivated to be actively involved in care activities.

Although family involvement in care has been explored both conceptually and empirically, there are less accounts of the underlying theoretical rationale for multi-component interventions aimed to improve family involvement in post-surgical patient care. Gaining this understanding will provides a solid basis for healthcare professionals and policy makers on how they can replicate and implement the intervention in their own setting. Thus, the aim of this project was to develop an evidence-based and theoretically grounded program to promote family involvement in fundamental care for patients after surgery.

2. Material and methods

This project is reported according to applicable criteria of the revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guideline [12].

2.1. Study design

This two-phased study follows a multi-phase design [13]. We used both an empirical approach to initially develop the family involvement program and then a logic model to refine it. The development of the family involvement program was undertaken by an interdisciplinary team of six healthcare professionals (i.e. surgeon, surgical resident, physician assistant, and three nurse scientists). We used the logic model in the development phase of the intervention to bring more clarity in the understanding of our program and to give theoretical insight in the links between inputs, activities, actions, and outcomes.

2.2. Study setting

The setting for this quality improvement project was two surgical wards that provided care to patients after oncological and gastrointestinal surgery. The intervention was created for these two wards involving about 64 full-time equivalent nursing staff in a 1000-bed university hospital (Setting blinded for peer review, the Netherlands). These wards were chosen because staff expressed a willingness to adopt a more family centred approach to their care.

2.3. Procedures, data collection and analysis

2.3.1. Phase 1

In Phase 1, an iterative method was used to combine evidence and healthcare professionals' preferences. Six steps were used (1) narrative review, (2) draft the program, (3) focus group meetings with nurses; (4) group discussion with physicians; (5) surveys of physicians’ opinions; (6) redraft the program. We deliberately opted for various data collection methods and tailored these methods to the target group and their preferences.

The first step was to undertake a narrative review. Because this was a quality improvement project, that aimed to get specific evidence into practice in a relatively short time frame [[14], [15], [16]], this review was limited to focusing on family centred care interventions and evidence of their effectiveness as well as on the association between patient outcomes and fundamental care activities. We carried out several searches of the scientific literature in the leading biomedical bibliographic databases (Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase, EBSCO CINAHL, PsychInfo and the Cochrane Library) up to March 2015, and was updated in July 2017. The preferred citations were systematic reviews and randomised clinical trials published in reputable journals. If these types of studies were not available, we included other study designs. No restriction was placed on the year of publication for the included studies.

The second step, drafting the program, was undertaken by the project team. The review findings along with a conceptual understanding about family involvement were used in this process.

During the third step, focus group meetings of seven to eight nurses were carried out to acquire insight in the views of nurses on active family involvement in fundamental activities after surgery, the competences nurses think they should have to stimulate active family involvement, and their preferences regarding educational strategies. Competencies were defined as the functional adequacy and capacity to integrate knowledge and skills with attitudes and values into specific context of practice [17]. Participants were recruited by using convenience sampling. We invited registered nurses who were working on one of the two surgical wards to participate. A topic list (Appendix A) and prompts to were used to structure the discussion. One project team member moderated the focus groups and two others observed and took notes. The focus groups were audiotaped to assist in checking and complete the notes. We used an iterative process to identify themes across the qualitative data [18], first by coding, then grouping codes into preliminary subthemes and themes using an iterative approach. Data saturation was reached after three meetings.

In the fourth step, a 45-min large group discussion was undertaken to gain more understanding physicians’ (surgeons and residents) perspectives and experiences regarding the active involvement and family presence on surgical wards. While smaller focus groups may have yielded more rich data, this was not viewed as an option as clinical (operating) schedules and lack of time of physicians hampers the feasibility. The surgeon involved in this project moderated this discussion by using a topic list (Appendix B) which was created to reflect the literature. Two project members observed and took notes. The group discussion was also audiotaped to assist in ensure the notes were comprehensive. The same thematic analysis approach as was used for the focus groups, was used for these notes.

An opinion survey targeting physicians was used in step 5 because we recognised that the large number of physicians attending the group discussion meant that some may not have had the chance to voice their opinions. As a result, we were not able to determine if data saturation was reached. Survey questions (Appendix C) were developed from a review of the literature [1], and local knowledge but were not psychometrically tested [1,19]. The aim of the survey was to get more insight into factors that potentially facilitated or hindered physicians in involving families in care. The data were analysed descriptively.

Step 6 involved a synthesis of the findings from all of these steps led to redrafting of the program. This activity was undertaken by the project team and occurred over several group meetings.

2.3.2. Phase 2

After Phase 1, the logic model underlying the program was developed. Four steps in logic modelling guided this process: (1) confirm situation, intervention aim, and target population; (2) documented expected outcomes (i.e. immediate (direct changes), intermediate (modifications in manifestations) and ultimate outcomes (improvement of patient condition), and outputs of the intervention; (3) identify and describe assumptions, external factors and inputs; and (4) confirm intervention components [20]. Discussion, reflection and other techniques like brainstorming and theoretical hypothesis testing were used in this process. All these activities were discussed within the interdisciplinary project team, and with other stakeholders (see Acknowledgements).

During the first activity, the interdisciplinary team used all the information gathered to clarify the initial situation prior to the intervention. The initial situation refers to the local context in which the intervention will be implemented, as well as the key issues that the intervention attempts to solve. We used the findings from the previous steps to formulate a clear definition of the situation (i.e. inadequate family participation in post-operative care), and to identify the key issues that we aim to address by implementing our program. In the second activity, we formulated outcome measurements which we expected to influence as a result of the program. We made a distinction between short-term, medium-term, and long-term changes in outcomes (see Fig. 1). To reach the outcomes several activities are required, as well as stakeholders who are involved in the activities. These are the so-called outputs (e.g. training of healthcare professionals). In the third activity, we described our assumptions (e.g. optimising fundamental care activities given by family caregivers after surgery leads to better patient outcomes that are sensitive to fundamental care activities). These assumptions are beliefs about the way we think that the intervention works and are essential, because wrong assumptions often lead to poor results [20]. Once we defined the assumptions, we discussed the inputs (e.g. staff- and family willingness and time). These inputs are all the resources and contributions that we put into the intervention [20]. The success rate of the program is not only influenced by the way of the implementation, but also by the presence of external factors. Although these external factors are often out of control of individual healthcare professionals and can be difficult to influence, they should be mapped and considered carefully. During the last step, we decided which components will be included in the program. In our model, one example of such a component is the active involvement of family caregivers in fundamental care activities. For this, we used the results of our narrative review and the input of the healthcare professionals.

Fig. 1.

Active involvement of family caregivers in surgical care logic model.

2.4. Ethical considerations

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of a University Hospital (setting blinded for peer review) reviewed the study protocol and concluded that the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO) does not apply to this project (reference number W17_067#17.085). Consent to participate in this project was implied by participants’ contribution to data collection. All authors declare that no competing interests exist.

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1

The family involvement program comprised fundamental care activities, in which family caregivers can be actively involved. Table 1 provides a summary of the results of each of the 6-step process used in Phase 1 to develop the program and gives a short overview of the evidence-base and healthcare professionals’ preferences and beliefs. Baseline characteristics of all respondents are presented in Table 2. Our narrative review identified limited evidence on effective interventions to promote family caregiver involvement in hospital care of adults [21,22]. Despite this, we recognised it was important to focus on complications known to be responsive to fundamental care [3,8,23]. We found several articles that showed an association between patient outcomes and fundamental care activities as summarised below:

-

•

Oral care, coughing and deep breathing exercises [10,24,25].

-

•

Early mobilisation and head-of-bed elevation [10,[26], [27], [28]].

-

•

Encourage oral intake and companionship during meals, and feeding assistant if needed [9,27].

- •

-

•

Remove visiting hours (i.e. open visiting policy) [1].

Table 1.

Six iterative steps to develop the intervention.

| Steps | Main topics | Participants | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Narrative review |

|

Literature focusing on adult patients admitted to the hospital (first search up to March 2015, and updated in July 2017) | |

| 2. Drafting the program |

|

||

| 3. Focus group meetings |

|

Three focus group meetings, totalling 23 participants |

|

| 4. Group discussion with physicians |

|

Discussion was led by one of the project leaders, and 63 participants attended the meeting |

|

| 5. Surgeon opinion survey |

|

Physicians response rate = 75/125; 60% Male: 45 (61%) Female: 29 (39%) |

|

| 6. Redrafting the program |

|

Note:PFCC, patient- and family centred care.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the respondents [n (%) ].

| Variable | Step 3:Focus group nurses (n = 23) | Step 4: Group discussion physicians (n = 63) | Step 5:Survey physicians (n = 73) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 16 (69.57) | – | 29 (39.73) |

| Male | 7 (30.43) | – | 45 (61.64) |

| Age, Median (range) | 33.0 (23–59) | – | – |

| Education | |||

| Vocational school education | 10 (43.48) | – | – |

| Bachelor degree | 13 (56.52) | – | – |

| Professional role | |||

| Nurse | 19 (82.61) | – | – |

| Senior nurse | 1 (4.35) | – | – |

| Head nurse | 2 (8.70) | – | – |

| Nurse specialist | 1 (4.35) | – | – |

| Surgeon | – | – | 19 (26.03) |

| Surgical residents | – | – | 17 (23.29) |

| Trainees | – | – | 10 (13.70) |

| MD/PhD-studentsa | – | – | 25 (34.25) |

| Physician assistant | – | – | 3 (4.11) |

| Unclear | – | – | 1 (1.37) |

Note:a MD/PhD-student: MD = Medical Doctor, they all finished their medical degree, and are now working on their PhD in the field of surgery.

These activities became the proposed targets for family caregiver involvement.

In step 2, drafting the program, we selected a minimum set of fundamental care activities that have a known effect on postoperative complications, as well as several tasks that encourage family caregivers to provide fundamental care activities (Table 3). These activities were all related to physical care because of our narrative review findings.

Table 3.

Fundamental care activities targeted for family involvement.

| Target | Fundamental care activity | Mode | Postoperative outcome | Evidence base |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal cleansing and dressing/safety and prevention | Oral care | Twice a day | Pulmonary complications, pneumonia, surgical site infections | |

| Respiration | Coughing and deep breathing exercises | Three times a day | Pulmonary complications, pneumonia | |

| Mobility | Early mobilisation Head-of-bed elevation |

Minimum of three times a day | Pulmonary complications, pneumonia Delirium |

|

| Eating and drinking | Encourage oral intake and companionship during meals; feeding assistance if needed | During meal times | Delirium Malnutrition |

|

| Safety and prevention | Active orientation; specific time-, place-, and person-related information in the context of the present day, and daily discussions on actual items (e.g. news) | Minimum of three times a day | Delirium | |

| Dignity/comfort/privacy/communication and education | Physical proximity; rooming-in; presence during medical rounds | Up to 24 h a day | Anxiety, depression, hopelessness, quality of life |

|

In step 3, the focus group data (n = 23) showed that nurses expected positive effects of family presence on clinical outcomes. However, some nurses had some negative personal experiences with managing patients and family caregivers who exhibit aggressive behaviour. Nurses mentioned that adequate communication was important, as are clearly defined responsibilities among patients, family caregivers, and healthcare professionals. Nurses named the following other competencies as important to engage and support the involvement of family caregivers; being persuasive, being honest, listening carefully, being flexible, have self-reflection and be able to negotiate. Nevertheless, there were nurses who doubted the extent to which they possessed these competences. They spoke about the specific need for a number of training courses, preferably focusing on self-reflection and conflict management.

Analysis of the large group discussion from step 4 with 63 physicians showed they expected positive effects of family presence on clinical outcomes. However, they also emphasised that family presence may be more time-consuming, and the patient was their top priority. Physicians sometimes felt hesitant to share information with family caregivers, because they were not always sure if family caregivers would use for some ‘hidden agenda’ they might have. While physicians realised families had to have an understanding of patients' condition to be able to assist in fundamental care, they were not sure about how they would actually determine patient's preference for which family members should have access to confidential patient information.

In total, 75 physicians (60%) completed the survey in step 5 (Appendix C). Most of the physicians saw family caregivers as a respected partner in healthcare team, and take their preferences into account in the decision-making process. The majority trusted the competences and skills of family caregivers to adequately deliver fundamental care activities. Almost 30% mentioned that they only support the active involvement of family caregivers if the effectiveness on patient outcomes has been demonstrated in scientific research.

Informed by the findings from the previous steps, in our synthesis (step 6) we added healthcare professionals’ education to the program. The education seems to be necessary to train physicians and nurses on the core concepts of patient- and family centred care, and on how to provide family education and coaching.

3.2. Phase 2

Informed by the findings from Phase 1, results of the four guiding steps used in Phase 2 that underpin the program are described next. The various components of the logic model were developed from the body of work, and not individual steps in Phase 1. The family involvement program logic model is displayed in Fig. 1.

3.2.1. Step 1: confirm situation, intervention aim, and target population

3.2.1.1. Situation

PFCC was one of the core priorities within the [full name blinded for peer review] medical centre (a Joint Commission International (JCI) accredited Organisation), further supported by the JCI quality standards for PFCC. They stated that ‘hospitals must embed effective communication, cultural competence, and PFCC practices into the core activities of its system of care delivery—not considering them stand-alone initiatives—to truly meet the needs of the patients, families, and communities served’ [29]. But in translating this to the surgical departments' policy, we found out families were not encouraged to actively participate in many aspects of care delivery, and they were not involved as partners in the healthcare team.

3.2.1.2. Intervention aim

The main aim of the intervention was to support the active involvement of family caregivers in fundamental care activities related to patients’ physical care needs after surgery during hospitalisation. Achieving this aim will improve the knowledge, skills and the self-confidence in care delivery of family caregivers, and subsequently has the potential to reduce readmissions related to postoperative complications sensitive to fundamental care activities.

3.2.1.3. Target population

The program will be offered to all adult patients undergoing elective surgery who have a suitable family caregiver who is up for training and care delivery. A potential family caregiver who meets any of the following criteria will be seen as suitable:

-

•

Age 18 years or older;

-

•

Able to be present during hospitalisation during the first 5 postoperative days on the nursing ward;

-

•

Is nominated by the patient as a family caregiver;

-

•

Is able to undertake care activities by themselves without support from healthcare professionals.

We targeted this population for several reasons. First, patients undergoing elective surgery frequently experience complications sensitive to fundamental care and unplanned readmissions [8,19]. Second, most have an expected hospital stay of at least five days which make adequate training and coaching of family caregivers possible. Finally, the majority of patients undergoing elective surgery experience difficulties in carrying out self-care activities in the postoperative phase and it is known that fundamental care activities are often deficient carried out in acute settings [3].

3.2.2. Step 2: document expected outcomes and outputs of the intervention

3.2.2.1. Outcomes

The ultimate outcomes of the family involvement program are a reduction of postoperative complications (i.e. potentially preventable complications sensitive to fundamental care activities), as well as a reduction of unplanned hospital readmissions related to these complications, shorter length of hospital stay, and improved patient- family- and healthcare professional's satisfaction. To achieve these outcomes, it is essential that first the intermediate outcomes are reached. Therefore, healthcare practice needs to become more family-centred, which involves healthcare professionals (i.e. physicians and nurses) changing their behaviours to facilitate active involvement of family caregivers. Furthermore, family caregivers should have opportunities to deliver fundamental care in an appropriate way as incorrect execution can negatively influence patient outcomes. To facilitate these intermediate outcomes immediate outcomes were defined. First, knowledge, skills and attitudes of healthcare professionals should be optimised, and healthcare professionals need to accept family caregivers as a respected partner in the care team. Second, family caregivers need to have the knowledge, skills and willingness to undertake fundamental care activities. Besides this, they also need to feel confidence about care delivery about themselves.

3.2.2.2. Outputs

The desired outputs consist of activities related to the main components of the intervention, namely education and the active involvement of family caregivers. The first defined output is to train physicians and nurses to provide FC education and coaching. The second focuses on the training of family caregivers to support them in the delivery of fundamental care to their loved ones during hospitalisation and after discharge if still needed (i.e. early mobilisation, encouraging oral intake, breathing exercises, oral care and supporting active orientation).

3.2.3. Step 3: identify and describe assumptions, external factors and inputs

3.2.3.1. Assumptions

Based on Phase 1 findings, we made three assumptions. First, optimising fundamental care activities given by family caregivers after surgery leads to better patient outcomes that are sensitive to fundamental care activities. Second, family caregivers are willing to receive training and to participate in delivering fundamental care activities. Third, healthcare professionals are willing to encourage and coach family caregivers during hospitalisation.

3.2.3.2. External factors

External factors that should be considered and may influence the implementation and the outcomes of the intervention were related to hospital policies regarding family involvement in care, ward cultures, team composition, the capacity to learn and coach family caregivers, and family dynamics.

3.2.3.3. Inputs

The inputs of the family involvement program are (1) willingness of staff and family caregivers; (2) adequate educational material to support nurses, physicians and family caregivers; (3) environmental support (e.g. a comfortable room with an extra bed and meals for the family caregiver).

3.2.4. Step 4: confirm intervention components

The family involvement program is a multi-component intervention, comprised two main components: (1) training and coaching of physicians and nurses; (2) the active involvement of family caregivers in fundamental care activities. The main components, barriers, tasks and persons in charge are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Main components of the program.

| Component | Targeted barrier | Tasks | In charge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training and coaching of healthcare professionals | Physicians and nurses' knowledge, skills, attitude and acceptance of families as partner in care towards a PFCC approach | - Explain the purpose, benefits, and goals of the involvement of family caregivers and the core concepts of PFCC - Explain the difference between passive and active involvement of family caregivers - Discuss facilitators and barriers regarding the involvement of family caregivers on surgical wards - Additional attention to support the nursing staff to integrate coaching competencies in clinical practice to facilitate the active involvement of family caregivers |

Educators |

| Family involvement in fundamental care activities | Family caregivers' knowledge, skills, attitude, confidence, and competence towards a PFCC approach | - Invite family caregivers to participate in fundamental care activities - Give information about fundamental care activities - Set shared goals with patient and family caregivers - Train family caregivers to deliver fundamental care activities to patients during hospitalisation - Physical proximity of family caregivers/patients (e.g. rooming-in for at least 8 h a day) - Invite family caregivers by medical rounds - Mutual agreement between healthcare professionals and family caregivers |

Nurses/family caregiver Physicians and nurses |

Note: PFCC, patient- and family centred care.

The training and coaching of physicians and nurses is mainly focused on the four core concept of PFCC: (1) dignity and respect; (2) information sharing; (3) participation; and (4) collaboration [30].

Several tasks to encourage family caregivers to provide fundamental care activities were planned (Table 4). While we used the Fundamentals of Care (FOC) framework to select possible tasks which family members can perform if they want to participate, these tasks cover all dimensions (i.e. physical, relational and psychosocial) (Table 3, Table 4) [31]. A minimum set of fundamental care activities known to have an effect on postoperative complications were selected (see Table 3).

Optional care activities for the family caregiver to participate in included wound dressing, taking care of abdominal drains or nasogastric tubes, and administration of medication. It was planned that a qualified nurse would supervise all activities until family caregivers were competent to carry out the activities on their own.

4. Discussion

This two-phased study, using both an empirical approach to initially develop the family involvement program and then a logic model to refine it, provides guidance on how to actively involve family caregivers in fundamental care activities in post-surgical care. We linked a quality improvement project with an evidence-based approach. These two approaches have similar overall goals, but focus on different parts of the problem [32]. A quality improvement approach is focusing on ‘doing the things right [32], i.e. how can we make it possible that family caregivers are stimulated to be actively involved in fundamental care activities. Whereas the evidence-based approach was used to focus more on ‘doing the right things’ based on the best available evidence [32]. Therefore, we selected fundamental care activities known to be effective in reducing some postoperative complications, and explored healthcare professionals' preferences and beliefs in Phase 1. Based on Phase 1 findings, we developed the logic model underlying the family involvement program in Phase 2.

To enhance a more patient- and family centred approach within hospitals, we propose the logic model as a useful framework for interdisciplinary teams to engage family caregivers as respected and active partners in care.

An obstacle we faced in developing the intervention was the lack of rigorous evidence regarding family involvement in hospitalised adults [21,22]. Furthermore, despite good will, practices do not always align with a more family-centred approach [33]. Involving families as respected partners seems to be simple, but is not easy. For example healthcare professionals miss opportunities to share information with patients and family members, and do not regularly check if their information given was understood or meaningful for them [34]. This constrained families from participation in care processes [34]. In our project, we focused on active family participation in fundamental care activities to reduce the number of postoperative complications, and the number of unplanned hospital readmissions related to these complications. However, other more general interventions to stimulate patient- and family participation, and optimise patient outcomes may be useful too (e.g. participation in bedside handover, and medication communication [35,36].

Besides the implementation challenges, the burden on FCs is another emerging obstacle. Family caregivers are confronted with a new range of tasks and responsibilities related to the patients' need [37], at a stressful time. Furthermore, some healthcare professionals may see this intervention as a justification to lower numbers of nursing staff and to save money, or an abduction of nurses’ responsibilities [38,39]. Yet, if healthcare leaders condoned this rationing of nursing staff, it may directly affects the patient outcomes in a negative way as nurse staffing is associated with the quality of care [40]. Finally, in creating this intervention, we focused mainly on physicians and nurses, with special attention to the important role of nurses, instead of other healthcare professionals. This because approximately 70% of all in-hospital care is delivered by nurses [41], and they are therefore in an ideal position to actively involve and coach family caregivers. Clearly, other healthcare professionals such as physiotherapists, dieticians, and social workers should also contribute to the active involvement of family members, and be preferably involved in the drafting of such a program.

In addition to the limitations mentioned thus far, some others include the context and theoretical underpinnings of the program. That is, the family involvement program was designed for use in two Dutch surgical units that employed staff willing to adopt a more family centred approach to their care. It is possible this program may not be appropriate in other surgical settings or with less willing staff, however, the process we used, and some of the program components may be feasible in other settings. Second, there are a plethora of theories that can be used to underpin both family centred care interventions and their implementation. Modifying or tailoring our program to varying contexts will likely be required. Additionally, we used a range of data collection methods to develop the program, and each method has his limitations. A narrative review was used to get insight in the existing evidence in a timely fashion; a comprehensive systematic review was not undertaken. As a result, we may have missed some relevant information. Regarding the focus groups, there is a possibility that some participants were overwhelmed and dominated by other participants, and therefore did not feel confident enough to give their own opinion. This may particularly occurred in the group of physicians, as the group was large, which made it more difficult for the moderator to involve everyone. To overcome this limitation, we sent out an additional survey and achieved a high response rate. Therefore, we consider our results to be robust. A very important limitation of our project is that we did not actively involve family caregivers in the design of the program, but used in-direct family input by using work of other researchers. Patient and public involvement in service delivery, quality improvement and research is relatively new in The Netherlands, and thus it is not an entrenched in our culture. Although we did not yet create a full partnership with patient- and family caregivers in the development of this program [42], we recognise the need for an extensive evaluation of this program in which we need to encourage patients and family caregivers to share their experiences and input for further refinement of the program. Additionally, given our learnings from this project, we will aim to involve them in planning for the evaluation.

The focus towards a more patient- and family centred environment has consequences to hospital policies regarding family involvement in care, ward cultures, team composition, the capacity to learn and coach family caregivers, and family dynamics. Although we developed the family involvement program with an interdisciplinary team, it is mainly focusing on direct nursing care because nurses traditionally carry out or support most of the fundamental care activities in-hospital.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, while PFCC should be the norm, this is not always the case. In this paper, we demonstrate how we aimed to change our practice to an environment in which family caregivers were stimulated to be actively involved in postoperative care on surgical wards, and how we took these different factors into account. We undertook a formal process to create a theory and evidence informed program to involve family caregivers actively in hospital care in which nurses play a central role as they deliver the largest amount of in-hospital care. The family involvement program using logic modelling presented here may help others, and especially nurses, to make an earnest attempt toward achieving this goal. It may provide a solid basis for healthcare professionals and policy makers to implement the program in their own setting, while recognising that research on the effectiveness of this model is still needed. Therefore, we are working on an evaluation of our quality improvement work, and plan to undertake a randomised clinical trial afterwards to obtain rigorous evidence of effectiveness.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work is supported by an unrestricted innovation research grant of the Amsterdam UMC, location Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Authors contribution

All authors made a substantial contribution to this work and gave approval for submission. In more detail: Anne Maria Eskes drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design of this project and were involved in the analysis of the results. Anne Marthe Schreuder, Hester Vermeulen, Els Jacqueline Maria Nieveen van Dijkum and Wendy Chaboyer commented on several drafts of the manuscript. Lastly, Els Jacqueline Maria Nieveen van Dijkum and Wendy Chaboyer supervised the work.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the nursing and medical staff from two surgical wards (G6-north, and G6-South) from the Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam in Amsterdam for giving their input regarding the development and implementation of the intervention. In particular, we want to thank Reggie Smith and Chris Bakker (head of the Nursing departments), Rosanna van Langen (physician assistant), Thirza de Graaf and Sanne Kapinga (student nurses), and Robert Simons (former nursing director) for their collaboration. Furthermore, we want to thank Dr Souraya Sidani from Ryerson University, Canada for sharing her knowledge with us in the early phase of the development of our logic model.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.09.006.

Appendix D. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Gasparini R., Champagne M., Stephany A., Hudson J., Fuchs M.A. Policy to practice: increased family presence and the impact on patient- and family-centered care adoption. J Nurs Adm. 2015;45(1):28–34. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000152. Epub 2014/12/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitson A.L., Muntlin Athlin A., Conroy T. Anything but basic: nursing's challenge in meeting patients' fundamental care needs. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(5):331–339. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12081. Epub 2014/04/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feo R., Kitson A. Promoting patient-centred fundamental care in acute healthcare systems. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.01.006. Epub 2016/04/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson D., Kozlowska O. Fundamental care-the quest for evidence. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(11–12):2177–2178. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14382. Epub 2018/04/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinhard S.C.G., Huhtala Petlick B., Bemis N. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville (MD): 2008. Patient safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses. [Chapter 14] Supporting Family Caregivers in Providing Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vries E.N., Ramrattan M.A., Smorenburg S.M., Gouma D.J., Boermeester M.A. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(3):216–223. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.023622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dindo D., Demartines N., Clavien P.A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bail K., Berry H., Grealish L., Draper B., Karmel R., Gibson D. Potentially preventable complications of urinary tract infections, pressure areas, pneumonia, and delirium in hospitalised dementia patients: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin C., Kimber K.L., Gibbs M., Weekes C.E. Supportive interventions for enhancing dietary intake in malnourished or nutritionally at-risk adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009840.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassidy M.R., Rosenkranz P., McCabe K., Rosen J.E., McAneny D.I. COUGH: reducing postoperative pulmonary complications with a multidisciplinary patient care program. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(8):740–745. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Maarel-Wierink C.D., Vanobbergen J.N., Bronkhorst E.M., Schols J.M., de Baat C. Oral health care and aspiration pneumonia in frail older people: a systematic literature review. Gerodontology. 2013;30(1):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman D., Ogrinc G., Davies L., Baker G.R., Barnsteiner J., Foster T.C. Explanation and elaboration of the SQUIRE (standards for quality improvement reporting excellence) guidelines, V.2.0: examples of SQUIRE elements in the healthcare improvement literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004480. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cresswell J., Plano Clark V.L. Sage Publications; Los Angeles: 2011. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown C., Hofer T., Johal A., Thomson R., Nicholl J., Franklin B.D. An epistemology of patient safety research: a framework for study design and interpretation. Part 1. Conceptualising and developing interventions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(3):158–162. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.023630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook D.J., Mulrow C.D., Haynes R.B. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(5):376–380. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Titler M. Translating research into practice. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(6 Suppl):26–33. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000277823.51806.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meretoja R., Leino-Kilpi H., Kaira A.M. Comparison of nurse competence in different hospital work environments. J Nurs Manag. 2004;12(5):329–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin R.C., Brown R., Puffer L., Block S., Callender G., Quillo A. Readmission rates after abdominal surgery: the role of surgeon, primary caregiver, home health, and subacute rehab. Ann Surg. 2011;254(4):591–597. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3182300a38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor-Powell E.H. 2008. Developing a logic model: teaching and training guide. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger Z., Flickinger T.E., Pfoh E., Martinez K.A., Dy S.M. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548–555. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackie B.R., Mitchell M., Marshall A. 2017. The impact of interventions that promote family involvement in care on adult acute-care wards: an integrative review. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burston S., Chaboyer W., Gillespie B. Nurse-sensitive indicators suitable to reflect nursing care quality: a review and discussion of issues. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(13–14):1785–1795. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen P.U., Larsen P., Hakonsen S.J. The effectiveness of systematic perioperative oral hygiene in reduction of postoperative respiratory tract infections after elective thoracic surgery in adults: a systematic review. JBI Database Sys Rev Impl Rep. 2016;14(1):140–173. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2016-2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katsura M., Kuriyama A., Takeshima T., Fukuhara S., Furukawa T.A. Preoperative inspiratory muscle training for postoperative pulmonary complications in adults undergoing cardiac and major abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(10) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010356.pub2. Cd010356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bakker F.C., Persoon A., Bredie S.J.H., van Haren-Willems J., Leferink V.J., Noyez L. The CareWell in Hospital program to improve the quality of care for frail elderly inpatients: results of a before-after study with focus on surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2014;208(5):735–746. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C.C., Li H.C., Liang J.T., Lai I.R., Purnomo J.D.T., Yang Y.T. Effect of a modified hospital elder life program on delirium and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(9):827–834. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorcaratto D., Grande L., Pera M. Enhanced recovery in gastrointestinal surgery: upper gastrointestinal surgery. Dig Surg. 2013;30(1):70–78. doi: 10.1159/000350701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joint Commission International . 2010. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care: a roadmap for hospitals.https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/ARoadmapforHospitalsfinalversion727.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson BHA M.R. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care; Bethesda, MD: 2012. Partnering with patients, residents, and families: a resource for leaders of hospitals, ambulatory care Settings, and long-term care communities. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitson A.L. The fundamentals of care framework as a point-of-care nursing theory. Nurs Res. 2018;67(2):99–107. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasziou P., Ogrinc G., Goodman S. Can evidence-based medicine and clinical quality improvement learn from each other? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(Suppl 1):i13–i17. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackie B.R., Marshall A., Mitchell M. Acute care nurses' views on family participation and collaboration in fundamental care. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(11–12):2346–2359. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackie B.R., Marshall A., Mitchell M. Patient and family members' perceptions of family participation in care on acute care wards. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1111/scs.12631. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobiano G., Bucknall T., Sladdin I., Whitty J.A., Chaboyer W. Patient participation in nursing bedside handover: a systematic mixed-methods review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;77:243–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobiano G., Chaboyer W., Teasdale T., Raleigh R., Manias E. Patient engagement in admission and discharge medication communication: a systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;95:87–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heckel L., Fennell K.M., Reynolds J., Boltong A., Botti M., Osborne R.H. Efficacy of a telephone out call program to reduce caregiver burden among caregivers of cancer patients [PROTECT]: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Canc. 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3961-6. 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aasen E.M., Kvangarsnes M., Heggen K. Nurses' perceptions of patient participation in hemodialysis treatment. Nurs Ethics. 2012;19(3):419–430. doi: 10.1177/0969733011429015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aasen E.M., Kvangarsnes M., Heggen K. Perceptions of patient participation amongst elderly patients with end-stage renal disease in a dialysis unit. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(1):61–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aiken L.H., Sloane D.M., Bruyneel L., Van den Heede K., Griffiths P., Busse R. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet. 2014;383(9931):1824–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62631-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Oostveen C.J., Gouma D.J., Bakker P.J., Ubbink D.T. Quantifying the demand for hospital care services: a time and motion study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0674-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carman K.L., Workman T.A. Engaging patients and consumers in research evidence: applying the conceptual model of patient and family engagement. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.