Abstract

Objective

β-adrenoceptor mediated activation of brown adipose tissue (BAT) has been associated with improvements in metabolic health in models of type 2 diabetes and obesity due to its unique ability to increase whole body energy expenditure, and rate of glucose and free fatty acid disposal. While the thermogenic arm of this phenomenon has been studied in great detail, the underlying mechanisms involved in β-adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake in BAT are relatively understudied. As β-adrenoceptor agonist administration results in increased hepatic gluconeogenesis that can consequently result in secondary pancreatic insulin release, there is uncertainty regarding the importance of insulin and the subsequent activation of its downstream effectors in mediating β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake in BAT. Therefore, in this study, we made an effort to discriminate between the two pathways and address whether the insulin signaling pathway is dispensable for the effects of β-adrenoceptor activation on glucose uptake in BAT.

Methods

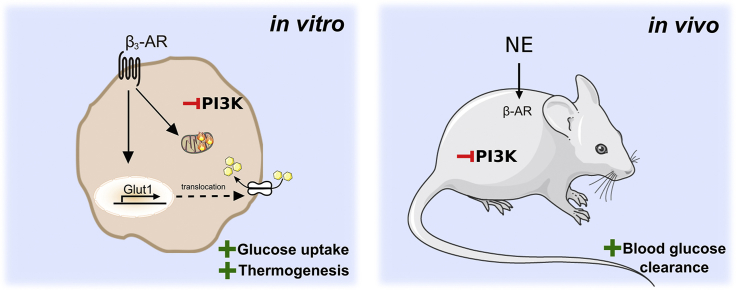

Using a specific inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase α (PI3Kα), which effectively inhibits the insulin signaling pathway, we examined the effects of various β-adrenoceptor agonists, including the physiological endogenous agonist norepinephrine on glucose uptake and respiration in mouse brown adipocytes in vitro and on glucose clearance in mice in vivo.

Results

PI3Kα inhibition in mouse primary brown adipocytes in vitro, did not inhibit β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake, GLUT1 synthesis, GLUT1 translocation or respiration. Furthermore, β-adrenoceptor mediated glucose clearance in vivo did not require insulin or Akt activation but was attenuated upon administration of a β3-adrenoceptor antagonist.

Conclusions

We conclude that the β-adrenergic pathway is still functionally intact upon the inhibition of PI3Kα, showing that the activation of downstream insulin effectors is not required for the acute effects of β-adrenoceptor agonists on glucose homeostasis or thermogenesis.

Keywords: Glucose clearance, Brown adipose tissue, GLUT1, Akt, PI3Kα, Insulin, Thermogenesis

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

PI3Kα/Akt are dispensable for β-AR mediated glucose clearance in vivo.

-

•

PI3Kα inhibition in brown adipocytes does not inhibit GLUT1 synthesis/translocation.

-

•

Acute β-AR induced thermogenesis in brown adipocytes is independent of PI3Kα/Akt.

-

•

Glucose uptake in brown adipocytes does not require a functional insulin pathway.

1. Introduction

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) is the major site for norepinephrine mediated glucose uptake both in vitro and in vivo [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]; therefore, activation of this tissue can have profound effects on whole body glucose metabolism. Owing to its discovery in adult humans [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]], there has a been growing interest in identifying the mechanisms underlying adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake in BAT for use as pharmacological targets in developing new antidiabetic and antiobesity therapies.

Insulin-mediated glucose uptake occurs through a well characterized pathway. Binding of insulin to its receptor triggers increasedphosphoinositide 3-kinase alpha (PI3Kα) activity, subsequent phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) activation of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1), which translocates inactive protein kinase B (Akt) to the plasma membrane via N-terminal PH domains, facilitating Akt Thr308 phosphorylation by PDK1. This causes a conformational change in Akt, allowing mechanistic target of Rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) to phosphorylate Akt at a second site, Ser473, fully activating Akt [16]. Activation of this signaling pathway results in translocation and subsequent fusion of perinuclear glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) vesicles to the plasma membrane thereby increasing cellular glucose uptake. In contrast, adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake in BAT occurs primarily though the β3-adrenoceptor. This involves increases in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels and mTORC2 activation but without involvement of exchange protein directly activated by cycling AMP (Epac) [9], leading to the de-novo synthesis and translocation of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) vesicles to the plasma membrane [17]. Insulin and adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake in BAT have thus been demonstrated to be distinct from one another, both in terms of the signaling mediators activated and the subtype of glucose transporter involved. In conditions of peripheral insulin resistance, in which the insulin pathway is defunct as in patients with type 2 diabetes [18], adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake in BAT could possibly be activated to ameliorate hyperglycemia.

However, there remains ongoing debate as to whether the insulin signaling pathway directly affects adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake into BAT. Activation of β3-adrenoceptors in vivo stimulates lipolysis in white adipose tissue (WAT) leading to the secretion of non-esterified fatty acids to balance the increased energy cost of BAT during non-shivering thermogenesis, the primary function of the tissue. The transiently increased plasma levels of non-esterified fatty acids can result in increased plasma insulin levels [19,20]. This increase could then have potential effects on systemic glycemia resulting from increased insulin release following β3-adrenoceptor stimulation, raising the question if the effects of norepinephrine on whole body glucose metabolism are due to β3-adrenoceptor glucose clearance or just a secondary effect following insulin secretion. A recent study suggests that Akt, a key mediator of the insulin signaling pathway, plays a central role in β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake and clearance in BAT [21]. However, we [17] and others [22] have shown that β-adrenoceptor signaling in adipose tissues does not involve Akt. To address these apparent divergences in the field, it is essential to establish whether adrenoceptor mediated glucose clearance occurs due to a distinct signaling pathway or whether at a mechanistic level, the insulin signaling pathway has to be intact and functional for these effects. This is of specific importance if adrenoceptor mediated glucose in BAT is to be a relevant pharmacological target in an insulin resistant condition.

In this study, we have examined the influence of insulin and insulin signaling (in particular PI3Kα) on acute β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake and respiration in brown adipocytes in vitro and glucose clearance in vivo. By using a specific PI3Kα inhibitor, we successfully inhibited the insulin signaling pathway in both systems without affecting β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake and respiration in brown adipocytes or norepinephrine stimulated glucose clearance in vivo. These results demonstrate that acutely, neither β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake, glucose clearance, nor thermogenesis require insulin, PI3Kα, or Akt activation.

2. Results

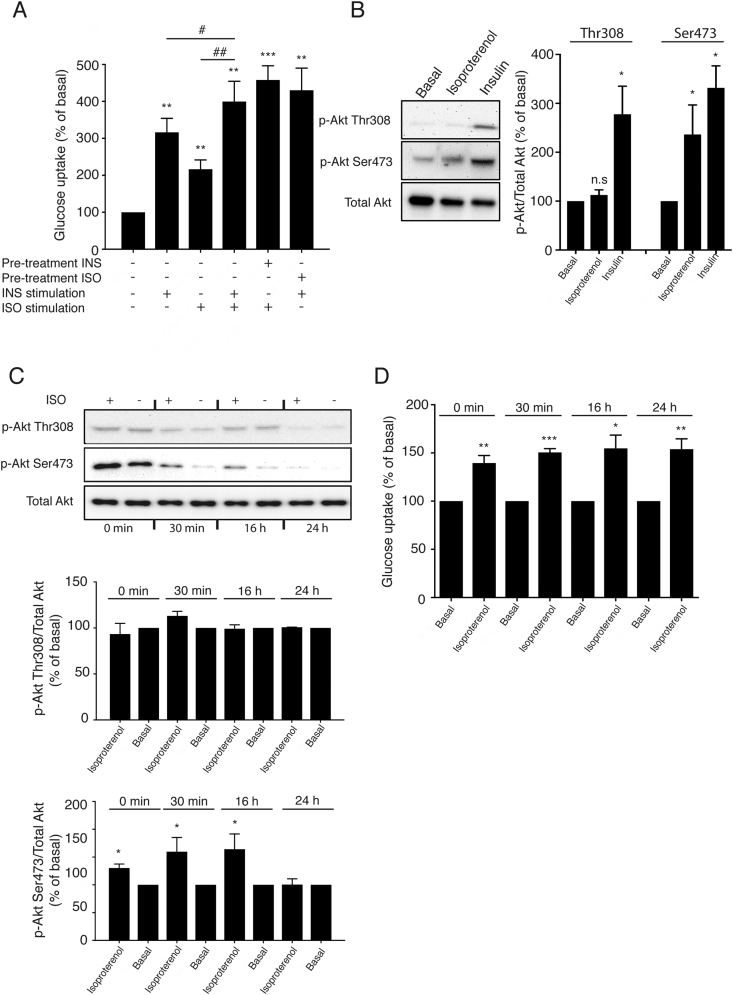

2.1. Additive effect on glucose uptake by insulin and β-adrenoceptor stimulation

To demonstrate the effect of insulin and β-adrenoceptor agonist treatment on glucose uptake in primary brown adipocytes, these cells were stimulated either with isoproterenol (1 μM), insulin (100 nM), or a combination of both. Treatment of brown adipocytes either with insulin or the β-adrenoceptor agonist isoproterenol for 120 min resulted in an approximate 2-3-fold increase in glucose uptake (Figure 1A), in agreement with earlier published results [9,17,23]. Co-treatment of brown adipocytes with both insulin and isoproterenol resulted in a partial additive effect, indicating the presence of more than one pathway to increase glucose uptake (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

β-Adrenoceptor stimulated Akt phosphorylation is affected by insulin. (A) The β-adrenoceptor agonist isoproterenol (1 μM) and insulin (100 nM) significantly increased glucose uptake in mature brown adipocytes after 120 min of stimulation. Co-adding insulin and isoproterenol and stimulating for 120 min resulted in a partial additive effect and stimulating the cells first with insulin for 10 min followed by isoproterenol for 120 min, or isoproterenol followed by insulin show a likewise partial additive uptake (n = 3). (B) Western blot showing Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 and Thr308 following 120 min stimulation with isoproterenol (1 μM) or insulin (100 nM) and (C) with and without 120 min stimulation of isoproterenol (1 μM) during different conditions and with different incubation time with insulin-free stimulation medium. (n = 3). (D) Glucose uptake with and without 120 min stimulation of isoproterenol (1 μM) during different conditions and with different incubation time with insulin-free stimulation medium. (n = 3). Each value represents the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

2.2. Insulin influences β-adrenoceptor stimulation of Akt phosphorylation

Western blots were performed to measure semi-quantitatively if β-adrenoceptor stimulation could phosphorylate Akt, a key signaling molecule involved in the insulin pathway. Insulin (100 nM) phosphorylated Akt at both Ser473 and Thr308 in brown adipocytes (Figure 1B). Isoproterenol, however, only phosphorylated Akt at Ser473, and not at Thr308 following 120 min of stimulation.

Brown adipocytes are routinely serum starved in medium still containing insulin for 16 h and thereafter in medium that is devoid of insulin for 30 min prior to stimulating the cells for the measurement of glucose uptake and protein phosphorylation. We hypothesized that the isoproterenol induced Akt phosphorylation in brown adipocytes observed in Figure 1B could be a consequence of residual effects of insulin from the serum starved medium. To investigate whether the observed Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 in cells treated with the β-adrenoceptor agonist was an artifact due to residual effects of insulin (the normal culture media contains 2.4 nM of insulin) present in the adipocyte serum starved medium and whether this had any effect on β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake, primary brown adipocytes were incubated in medium devoid of insulin for either 0, 30 min, 16 h, or 24 h prior to isoproterenol treatment for 120 min. Thereafter Akt phosphorylation and glucose uptake were measured in parallel.

Isoproterenol stimulation increased glucose uptake in all cells regardless of the duration of insulin removal before stimulation (Figure 1D), and failed to phosphorylate Akt at Thr308 under any conditions (Figure 1C). However, isoproterenol (1 uM) failed to phosphorylate Akt at Ser473 only when insulin was removed from the cells for 24 h (and not at shorter time periods) (Figure 1C). Collectively, our data indicate that adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake in brown adipocytes is functional even in conditions where Akt is not phosphorylated.

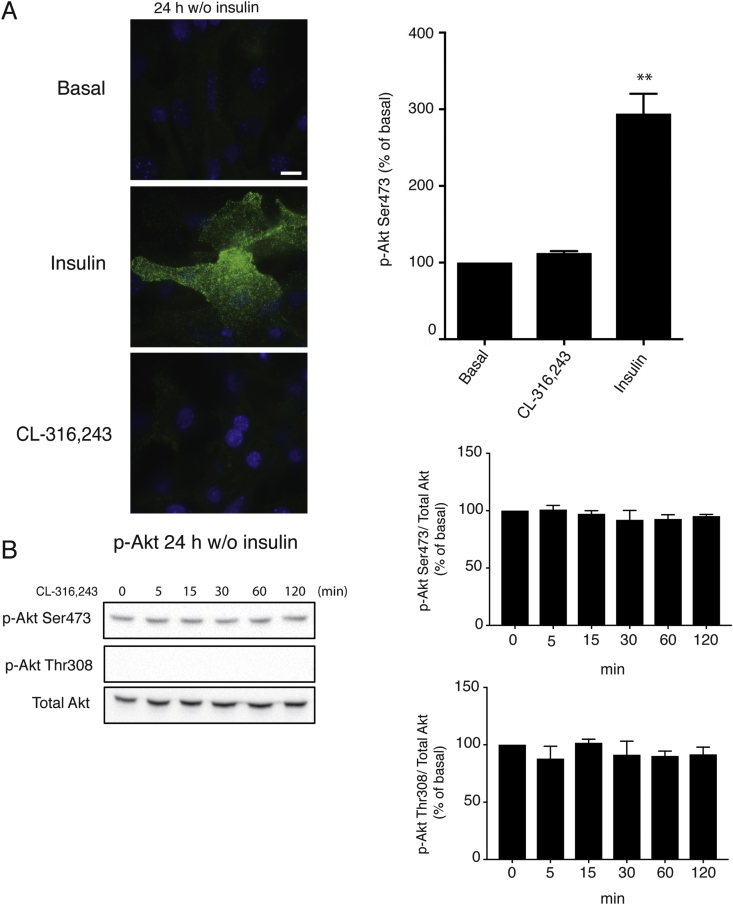

2.3. Akt is not phosphorylated at the plasma membrane following β-adrenoceptor agonist treatment

Akt is translocated to the plasma membrane upon insulin stimulation due to increased PIP3 levels [16]. This translocation occurs rapidly (within a few minutes) and is crucial for subsequent signaling. Since a marginal increase in Akt Ser473 phosphorylation is detected in brown adipocytes after stimulation with isoproterenol-agonist for 120 min under standard conditions, in which the cells are insulin starved for 30 min only, we wanted to investigate if acute adrenoceptor stimulation could affect Akt phosphorylation and Akt cellular localization in a similar manner to insulin.

Following removal of insulin for 24 h in the medium, brown adipocytes were stimulated with insulin or the β3-adrenoceptor agonist CL-316,243 for 15 min. Subsequently, immunocytochemistry was performed to visualize p-Akt Ser473 at the plasma membrane using TIRF microscopy. Insulin stimulation resulted in a pronounced accumulation of p-Akt S473 at the plasma membrane (Figure 2A). However, there was no detectable change in localization of p-Akt Ser473 at the plasma membrane in cells treated with CL-316,243. In addition, CL-316,243 failed to phosphorylate Akt at Ser473 or Thr308 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Acute β3-adrenoceptor stimulation does not phosphorylate Akt at the plasma. Mature brown adipocytes, with insulin removed from media 24 h prior stimulation with 1 μM CL316243 or 100 nM insulin. (A) Showing translocated p-Akt Ser473 by TIRF microscopy, at 15 min of stimulation. Quantifications show basal normalized to 100%. (n = 3) (B) Western blot showing time-dependent whole cell phosphorylation of p-Akt Ser473 and Thr308 over total Akt. Quantifications show basal normalized to 100%. Each value represents the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Bar 10 μm.

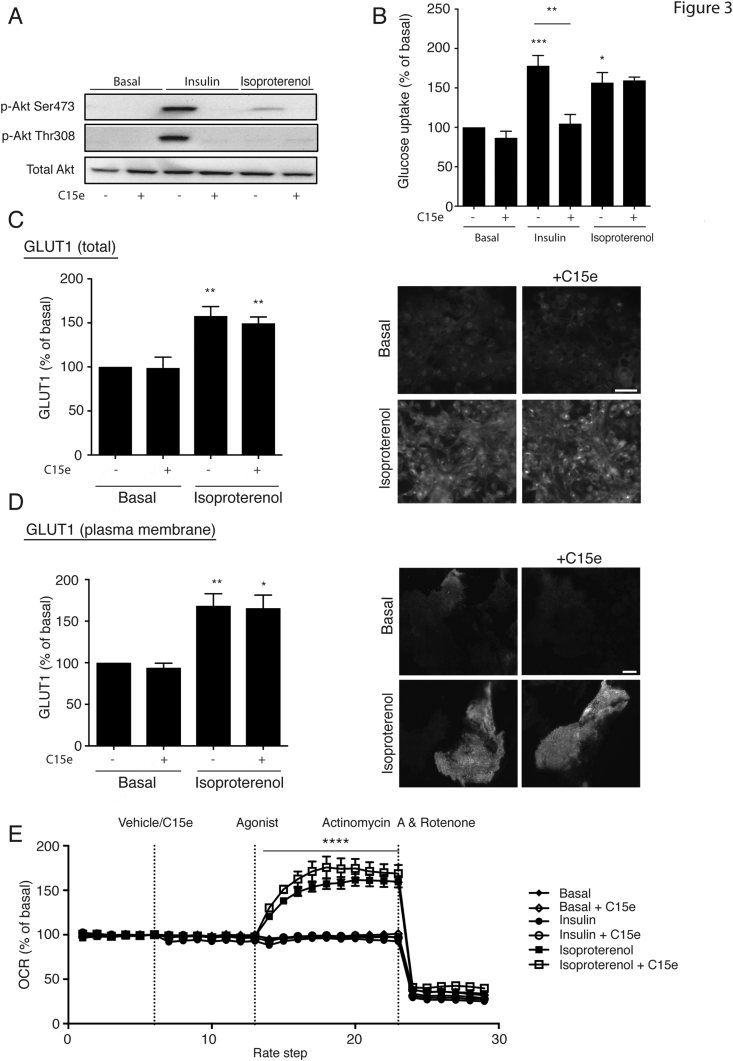

2.4. PI3Kα inhibition does not affect β-adrenoceptor mediated-glucose uptake

The results in Figure 1, Figure 2 show that the Akt Ser473 phosphorylation observed following β-adrenoceptor stimulation is a secondary effect of the insulin added to the differentiation and serum starvation media, that can be abolished by removing insulin from the media for longer periods of time (i.e. 24 h insulin free conditions). This was further confirmed by performing Akt phosphorylation studies in the absence/presence of the specific PI3Kα inhibitor, compound 15e (C15e) [24].

Both insulin and isoproterenol stimulation under standard conditions resulted in Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 in brown adipocytes (Figure 3A). In cells pretreated with C15e, insulin and isoproterenol treatment failed to increase Akt phosphorylation at Ser473. In addition, while C15e pretreatment fully blocked insulin stimulated glucose uptake, PI3Kα inhibition did not decrease β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake (Figure 3B). Collectively, our data suggest that β-adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake can still occur when the insulin pathway is inhibited indicating the presence of distinct pathways in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in brown adipocytes.

Figure 3.

PI3Kα inhibition does not reduce β-adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake in primary brown adipocytes. (A–B) The effect of 1 μM C15e, a PI3Kα inhibitor, on Akt phosphorylation (Ser473 and T308) and glucose uptake, in response to insulin (100 nM) and isoproterenol (1 μM). Brown adipocyte primary cultures were pretreated with C15e (1 μM) for 30 min followed by stimulation with isoproterenol or insulin for 120 min (n = 3 for western blot and n = 6 for glucose uptake). (C–D) Permeabilized mature brown adipocytes treated for 2 h with 1 μM isoproterenol in the presence or absence of 1 μM C15e, showing total cellular GLUT1, bar 50 μm (C) or GLUT1 translocated to the plasma membrane by TIRF microscopy, bar 10 μm (D) (n = 3). (E) The effect in oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in primary brown adipocytes stimulated by isoproterenol (1 μM) and insulin (1 μM) with C15e (1 μM) or vehicle using Seahorse XF96. The statistics shown are valid for both traces of brown adipocytes treated with both isoproterenol and isoproterenol in the presence of C15e (n = 4). Quantifications show basal normalized to 100%. Each value represents the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001.

2.5. Increased GLUT1 synthesis and translocation following β-adrenoceptor stimulation occurs independently of the insulin pathway

While insulin stimulation in BAT results in activation of Akt and subsequent translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane to increase glucose uptake [25], β-adrenoceptor stimulation instead increases the de novo synthesis of GLUT1, and translocation of these newly synthesized transporters to the plasma membrane [17,23]. To examine any potential effect of the insulin pathway on the synthesis and translocation of GLUT1, we stimulated brown adipocytes with the β-adrenoceptor agonist isoproterenol in the presence and absence of C15e and measured total GLUT1 content in the cell and GLUT1 just at the plasma membrane (Figure 3C,D). C15e did not prevent the de novo synthesis of GLUT1 (Figure 3C), or GLUT1 translocation to the plasma membrane (Figure 3D) following β-adrenoceptor treatment, suggesting that β-adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake is dependent on GLUT1 translocation and that this occurs without neither the influence of PI3Kα, the phosphorylation of Ser473 nor the insulin pathway.

2.6. PI3Kα inhibition does not inhibit acute β-adrenoceptor mediated respiration

To establish whether the activation of PI3Kα and downstream effectors such as Akt was essential for β-adrenoceptor stimulated respiration in primary brown adipocytes, oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were measured using the Seahorse XF96 in brown adipocytes stimulated with isoproterenol (1 μM) and insulin (1 μM) in the presence or absence of C15e (1 μM) (Figure 3E). Isoproterenol significantly increased respiration, while insulin had no effect on OCR. C15e had no inhibitory effect on basal or isoproterenol stimulated OCR. This suggests that both acute glucose uptake and respiration occur independently of PI3Kα or Akt in primary brown adipocytes.

2.7. Inhibiting the β3-adrenoceptor significantly affects glucose clearance in vivo

Several studies from our group and others [[26], [27], [28]] have shown that β-adrenoceptor stimulation of BAT improves glucose clearance, both long-term and acutely; however, due to the ambiguity in the field regarding the impact of insulin in mediating this effect in vivo [19,20], this calls for further investigation.

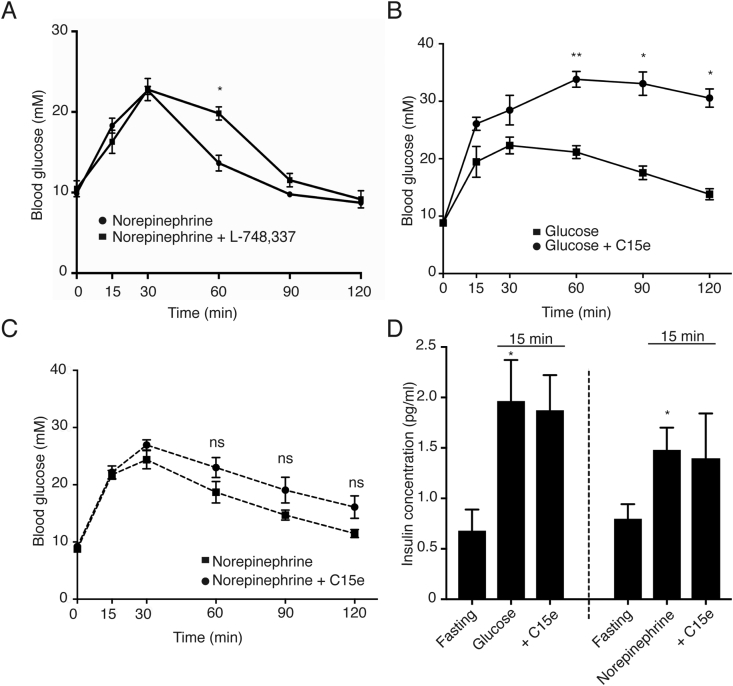

To investigate if adrenoceptor stimulated glucose clearance in vivo requires functional β3-adrenoceptors, we treated mice with the β3-adrenoceptor antagonist L-748,337 [29] or vehicle, followed by 1 mg/kg of norepinephrine. In mice pretreated with vehicle, norepinephrine injection resulted in hepatic glucose outflow peaking at 30 min that was eventually cleared within the span of 120 min (Figure 4A). Contrastingly in mice treated with L-748,337, while hepatic glucose output was intact, these mice displayed an attenuated glucose clearance 60 min post norepinephrine injection. Additionally, a 2 way ANOVA was performed that showed that the interaction between the combined effects of the agonist over time and inhibitor were highly significant (p = 0.0053). This suggests that β3-adrenoceptors are important for glucose clearance after adrenoceptor stimuli.

Figure 4.

Adrenoceptor-driven glucose clearance is attenuated by a β3-adrenoceptor antagonist but is not affected by the PI3Kα inhibitor C15e. (A) C57Bl/6N mice were treated with the β3-adrenoceptor antagonist L-748,337 (5 mg/kg body weight ip.) or vehicle (DMSO) 10 min prior to treatment with norepinephrine (1 mg/kg body weight i.p.) or equal volume of saline (i.p). Blood glucose was measured at time points 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after administration of norepinephrine (n = 6 mice). A 2way ANOVA was performed to test for statistical significance, p values for the effect of the agonist over time, the inhibitor and the interaction were p < 0.0001, p = 0.1296 and p = 0.0053 respectively. C57Bl/6N mice were treated with the PI3Kα inhibitor, C15e (10 mg/kg body weight i.p) or vehicle (DMSO) 10 min prior to treatment with either (B) glucose (2 g/kg body weight i.p.), (a 2way ANOVA was performed to test for statistical significance, p values for the effect of the agonist over time, the inhibitor and the interaction were p = 0.0012, p = 0.0037 and p = 0.0045 respectively). (C) Norepinephrine (1 mg/kg body weight i.p.) or equal volume saline (i.p). Blood glucose was measured at time points 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after administration of glucose and norepinephrine respectively (n = 8–9 mice); a 2way ANOVA was performed to test for statistical significance, p values for the effect of the agonist over time, the inhibitor and the interaction were p = 0.0001, p = 0.1244 and p = 0.1333 respectively. (D) Insulin concentration in the serum at fasting levels and after 15 min of stimulation with glucose (2 g/kg body weight i.p.) or norepinephrine (1 mg/kg body weight i.p.) with and without C15e (n = 8 in fasting groups, n = 4 in stimulated groups). Each value represents the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

2.8. Inhibiting PI3Kα does not affect β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose clearance in vivo

Inhibition of β3-adrenoceptors can potentially affect free fatty acid secretion and consequently insulin release which could partially explain the observed differences in 4A. Therefore, we aimed to completely inhibit the contribution of insulin to the observed adrenoceptor stimulated glucose clearance in vivo. To first demonstrate the inhibition of insulin induced glucose clearance in vivo, we treated mice with a bolus of glucose with or without C15e (Figure 4B). While mice pretreated with vehicle were able to clear glucose effectively, mice pretreated with C15e retained a significantly higher level of blood glucose over the entire duration of the experiment. This shows that C15e is extremely effective in inhibiting the insulin stimulated glucose clearance in vivo.

Upon administration of C15e or vehicle followed by norepinephrine, contrary to the previous group, we observed that both groups of mice cleared glucose arising from hepatic outflow equally effectively (Figure 4C). Noticeably, there was no significant difference in glucose clearance in groups treated with and without the inhibitor using a 2way ANOVA, distinctly showing that the clearance seen is due to the adrenoceptor agonist without any involvement of insulin. Both glucose and norepinephrine treatment of mice rapidly increased insulin levels in the blood (Figure 4D), which was not affected by C15e.

3. Discussion

We have previously demonstrated that β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake in brown adipocytes in vitro most likely occurs independently of insulin and the insulin signaling pathway [17,30]. However, recent studies have further expanded upon the role of the insulin signaling pathway in adrenoceptor mediated glucose uptake and have demonstrated that Akt phosphorylation occurs upon stimulation of β-adrenoceptors [21,31] and that Akt is essential for this effect in BAT [21]. In this study, we made an effort to understand the mechanism underlying adrenoceptor glucose uptake and establish whether this effect persists upon the inhibition of the insulin pathway both in vitro and in vivo.

3.1. β-adrenoceptor stimulation in primary brown adipocytes yields phosphorylation at Ser473 due to residual insulin in media

In this study, while insulin resulted in a pronounced phosphorylation of Akt at both Thr308 and Ser473, isoproterenol did not affect Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 but increased Akt Ser473 phosphorylation. The general consensus is that Akt requires phosphorylation at both Ser473 and Thr308 to be fully active [16,32]. It has been proposed that phosphorylation at Thr308 alone can partially activate Akt, but phosphorylation solely at Ser473 has not been proposed to have any stimulatory effect [32]. This would then indicate that the weak phosphorylation at Akt Ser473 we observe in brown adipocytes treated with isoproterenol is in itself not enough for activating Akt. In addition, since we observed no phosphorylation of Akt at Thr308, there is no reason to believe that partial activation of Akt has any role in adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake.

We hypothesized that Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 following isoproterenol treatment could be explained by residual effects due to insufficient insulin starvation prior to the experiment. Generally, to eliminate any effects of insulin signaling in brown adipocytes, the cells are routinely incubated with insulin-free medium 30 min prior to the start of most experiments. We hypothesized that this time frame was too short to completely eliminate effects of the insulin from the preceding medium and could explain the apparent β-adrenoceptor mediated Akt phosphorylation in vitro. It has been shown that mTORC2 activity at the plasma membrane is constitutive and PI3K-insensitive [33], so that membrane recruitment of Akt is sufficient for it to be phosphorylated at Ser473 by mTORC2. We hypothesized that the β-adrenoceptor mediated Akt phosphorylation could be explained by recruitment of Akt to the plasma membrane as a consequence of residual insulin in parallel with the recruitment and activation of mTORC2 by isoproterenol treatment [17]. We therefore insulin-starved brown adipocytes for varying lengths of time prior to stimulation with isoproterenol and measured Akt phosphorylation and glucose uptake. Isoproterenol treatment had no effect on Akt Ser473 phosphorylation when the cells had been insulin starved for 24 h. However, in these cells, isoproterenol was fully able to induce glucose uptake thereby signifying that the phosphorylation of Akt is inconsequential to the effects of β-adrenoreceptor mediated induction of glucose uptake in brown adipocytes.

It has recently been shown that Akt activity is confined to membranes enriched in PIP2 and PIP3 [34,35] and that the binding of PIP2 and PIP3 to the PH domain was required to stimulate kinase activity of phosphorylated Akt [34]. Furthermore, Akt was shown to be rapidly dephosphorylated in absence of PIP3, an autoinhibitory process driven by the interaction of its PH and kinase domains [35]. In primary brown adipocytes that had been insulin starved for 24 h, β-adrenoceptor stimulation did not result in Akt translocation to the plasma membrane, nor did it result in phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 or Thr308 at any time point up to 2 h. Together these results imply that Akt phosphorylation holds no functional role in the adrenergic signaling pathway.

Both insulin and isoproterenol increase glucose uptake in primary brown adipocytes in vitro, with several studies (including this study) showing that β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake occurs in the absence of insulin signaling [[8], [9], [10],17]. Still, there are studies suggesting that Akt is a key effector of β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake and lipid metabolism in brown adipocytes [21,22,36]. However, most of these studies culture brown adipocytes in medium containing differentiation agents, including insulin, which is not removed prior to the experiments. According to our present results, residual insulin could explain perceived β-adrenergic mediated activation of Akt in vitro. Thus, it is extremely important to optimize insulin starvation protocols thoroughly, especially for experiments aimed at understanding the molecular mechanisms activating proteins also involved in the insulin pathway.

3.2. Inhibition of PI3Kα does not affect acute β-adrenoceptor glucose uptake, GLUT1 de novo synthesis, GLUT1 translocation nor thermogenic function

To conclusively show that β-adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake into brown adipocytes occurs independently of the insulin pathway, brown adipocytes were pre-treated with C15e, a PI3Kα inhibitor. These cells were insulin starved for 30 min as we observed maximal, though weak, adrenoceptor mediated Akt phosphorylation at this time point. C15e pre-treatment resulted in complete inhibition of both insulin and adrenoceptor induced Akt phosphorylation, while C15e only inhibited insulin (but not isoproterenol) mediated glucose uptake.

Insulin mediated glucose uptake is mediated primarily through translocation of GLUT4 vesicles. We and others have shown that in brown adipocytes, the induction and subsequent translocation of GLUT1 is the major determinant of adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake [17,23,37]. We showed that isoproterenol treatment increased GLUT1 synthesis and its translocation even in the presence of C15e.

Additionally, inhibition of PI3Kα in brown adipocytes had no inhibitory effect on β-adrenoceptor mediated respiration. Combined, these results highlight that a functional insulin signaling pathway is unnecessary for these acute effects of adrenoceptor activation in brown adipocytes.

3.3. β-Adrenoceptor mediated glucose clearance in vivo does not require a functional insulin pathway

BAT is the major contributor to the clearance of blood glucose levels by norepinephrine, both acutely and chronically [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. However, due to the effect β-adrenoceptor stimulation has on liver glucose output together with the effect β3-adrenoceptor agonists have on WAT (stimulating lipolysis and non-esterified fatty acid secretion) [19,20], two events resulting in increased insulin release from the pancreas, there is currently a discussion on how much influence insulin and its signaling mediators have on norepinephrine-driven glucose clearance. Therefore, to unravel the controversy about this effect, for the first time in vivo, we inhibited the insulin pathway while activating the adrenergic pathway.

The selective β3-adreneoceptor antagonist L-748,337 was used to examine the role of β3-adrenoceptors on norepinephrine-driven glucose clearance, showing that β3-adrenoceptor stimulation contributes to glucose clearance mediated by norepinephrine. However, since β3-adrenoceptors are present in both BAT and WAT, the direct effect of β3-adrenoceptor glucose clearance and the secondary release of fatty acids from WAT via β3-adrenoceptors and insulin release from the hepatic output, needed to be distinguished. For this purpose, we used C15e, the selective PI3Kα inhibitor. The inhibitor had no effect on hepatic glucose output or insulin secretion but was successful in inhibiting the glucose-bolus driven clearance. Remarkably, it had no effect on the glucose clearance following injection of norepinephrine, even though the increase in insulin levels was not significantly different to that of glucose administration. These results show for the first time that although norepinephrine results in secondary insulin effects on glucose homeostasis, norepinephrine alone is sufficient to drive the blood glucose clearance.

3.4. Utilizing the β-adrenergic pathway to improve glucose clearance

The main tissue for norepinephrine stimulated glucose uptake and clearance of blood glucose levels is BAT in rodents [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. While in this study, we confirmed the importance of β3-adrenoceptors for blood glucose clearance, we cannot exclude that the β2-adrenoceptor present on skeletal muscle could be partly responsible for the β-adrenoceptor blood glucose clearance we observe. A study exposing human type 2 diabetes patients to a mild cold-acclimatization protocol, showed increased translocation of GLUT4 to muscle cell membranes and dramatically improved skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Additionally, this mild cold-induced GLUT4 translocation did not appear to occur via phosphorylation of Akt at either Thr308 or Ser473, nor via an improved insulin signaling, nor via the activation of 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [38]. Additionally, we have previously shown that Goto-Kakizaki rats (a model for type 2 diabetes) treated with a β2-adrenoceptor agonist for 4 days become markedly better at clearing glucose [30]. In addition, the stimulation of β2-adrenoceptors in rat skeletal muscle cells led to glucose uptake without observing phosphorylation of Akt at either Thr308 or Ser473 at any time point. This effect persists even when Akt was pharmacologically inhibited in vitro [30]. Collectively, these results imply that even if skeletal muscles contribute to the β-adrenoceptor driven glucose clearance in vivo, it does so independently of Akt.

While insulin leads to an increase in anabolic mechanisms and glucose uptake, adrenoceptor stimulated glucose uptake in BAT will instead be used for increased catabolic procedures, i.e. burning energy for heat, and for replenishing fuel not via GLUT4, but instead GLUT1. Physiological implications would be that these pathways can be stimulated either solely or in concert in vivo, which could be of very high consequence for the notion of using BAT as potential target in treatment for type 2 diabetes and obesity. In these disorders, the patients suffer from insulin insensitivity and down-regulation of many important signaling proteins that drive insulin-mediated glucose uptake, like PI3Kα and Akt. Since adrenoceptor stimulated glucose clearance and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes does not require these signaling molecules, we believe that this distinct pathway can serve as a potential target for type 2 diabetes treatment.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Glucose clearance

Male C57Bl/6 mice (12–14 weeks old) were starved for 5 h, before being administered with C15e (10 mg/kg i.p.), L-748,337 (5 mg/kg i.p.) or equal volume of vehicle (DMSO) 10 min before administration of either glucose (2 g/kg i.p.), norepinephrine (1 mg/kg i.p.), or an equal volume of saline. Blood from the tail vein was drawn to measure blood glucose values with a glucometer (AccuCheck, Biochemical systems international Srl., Florence, Italy) (values above 30 mM were checked by glucometer Xpress). Serum was taken at time points 0 and 15 min for measurement of insulin levels by an Ultrasensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Chrystal Chem Inc.). All experiments were conducted with ethical permission from the North Stockholm Animal Ethics Committee.

4.2. Immunoblotting

Brown adipocytes were harvested as previously described [17]. Immunoblotting was performed as previously described [39]. The primary antibodies Akt, p-Akt Thr308, p-Akt Ser473, (diluted 1:1000) were all from Cell Signaling. All primary antibodies were detected using a secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG, Cell signaling) diluted 1:2000.

4.3. Brown fat precursor cell isolation

NMRI male mice (3-4 week-old) were purchased from Nova-SCB AB, Sweden. Animals were euthanized by CO2, and brown fat precursor cells isolated from the intrascapular, axillary and cervical brown adipocyte depots as previously described [40]. All experiments were conducted with ethical permission from the North Stockholm Animal Ethics Committee.

4.4. Primary cell culture of brown adipocytes

The cell culture medium consisted of DMEM supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (NCS), 2.4 nM insulin, 10 nM HEPES, 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 25 μg/ml sodium ascorbate [40]. Aliquots of 0.1 ml cell suspension were cultured in 24-well culture dishes with 0.9 ml of cell culture medium. Cultures were incubated in a 37 °C humidified atmosphere of 8% CO2 in air (Heraeus CO2-auto-zero B5061 incubator, Hanau, Germany). On days 1, 3, and 5, the cell culture medium was renewed. Cells were used on day 7.

4.5. 2-Deoxy-D-[1–3H]-glucose uptake in primary brown adipocytes

Glucose uptake was performed as previously described [17]. Cells were serum starved (DMEM supplemented with 0.5% BSA, 2.4 nM insulin, 10 nM HEPES, 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 25 μg/ml sodium ascorbate) the night prior to experiment. Starvation medium was removed 30 min before the experiments (unless otherwise indicated), and an insulin free starvation medium was added. Inhibitors were added as indicated for 30 min before stimulated with insulin or isoproterenol for 2 h.

4.6. Fluorescence microscopy

Brown adipocytes were grown and differentiated on laminin-coated glass-bottom dishes (P35GC-1.5-10-C; MatTek, Ashland, MA). Cells were serum starved overnight and exposed to buffer without insulin for 30 min or 24 h before cells were stimulated for 2 h with drugs, immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described [17]. GLUT1 (1:500) antibody was from Abcam.

Both total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (TIRFM) and epifluorescence images were captured using a AxioObserver D1 Laser TIRF 3 system (Carl Zeiss) equipped with an alpha Plan-Apochromat 63 × /1.46 oil objective lens, Plan-Apochromat 20×/0,6 objective lens, diode-pumped solid-state (561 nm/20 mW) laser, 86HE (561 nm) shift-free filter set and filter set 49 for Dapi. Images were captured with an AxioCam MRm rev.3 camera (Carl Zeiss), and the system was controlled by ZEN blue 2011 software. Penetration depth of the evanescent field is estimated to be ∼160 nm. Images were acquired with a readout-rate of average exposure time of 500 ms. Intensities of all region of interests (ROIs) were normalized to control, 5 ROIs per image, with at least 5 images per condition (n = 3).

4.7. Seahorse XF96 analysis

3–4 week old male C57Bl/6J mice were obtained from Monash University Animal Research Platform (Clayton, Victoria, Australia) with ethical permission from the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences Animal Ethics Committee (MIPS.2015.14). Mice were killed by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation and primary brown adipocytes isolated and cultured as described above. On day 7, adipocytes were washed twice in XF assay media (Seahorse Bioscience) supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 0.5% BSA, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 2 mM l-glutamine, and 160 μl added per well, and incubated in a non-CO2 incubator for 30 min before being placed in the Seahorse. 6 baseline rate measurements were made using a 2 min mix, 2 min measure cycle, before addition of vehicle or C15e (1 μM) for 7 rates, addition of isoprenaline or insulin (1 μM) for 10 rates, followed by the simultaneous addition of antimycin A (1 μM) and rotenone (0.1 μM) for 6 rates to define non-mitochondrial respiration. OCR rates immediately prior to vehicle or C15e addition were used as the basal rates and defined as 100%.

4.8. Statistics

Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the results expressed as mean ± SEM. The responses to agonists were calculated as percentage to control, which were set to 100%. The statistical significance of differences between groups was analyzed by Student's t-test or repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Geiser-Greenhouse correction followed by Sidak's multiple comparison test.

Acknowledgments

T. Bengtsson is supported by Vetenskapsrådet-Medicin (VR-M) from the Swedish Research Council, Stiftelsen Svenska Diabetesförbundets Forskningsfond, the Magnus Bergvall Foundation, and the Carl Tryggers Foundation. Assistance with TIRF microscopy by IFSU is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Stanford K.I., Middelbeek R.J., Townsend K.L., An D., Nygaard E.B., Hitchcox K.M. Brown adipose tissue regulates glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123(1):215–223. doi: 10.1172/JCI62308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu X., Perusse F., Bukowiecki L.J. Chronic norepinephrine infusion stimulates glucose uptake in white and brown adipose tissues. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266(3 Pt 2):R914–R920. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.3.R914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shibata H., Perusse F., Vallerand A., Bukowiecki L.J. Cold exposure reverses inhibitory effects of fasting on peripheral glucose uptake in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257(1 Pt 2):R96–R101. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.1.R96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inokuma K., Ogura-Okamatsu Y., Toda C., Kimura K., Yamashita H., Saito M. Uncoupling protein 1 is necessary for norepinephrine-induced glucose utilization in brown adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2005;54(5):1385–1391. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooney G.J., Caterson I.D., Newsholme E.A. The effect of insulin and noradrenaline on the uptake of 2-[1-14C]deoxyglucose in vivo by brown adipose tissue and other glucose-utilising tissues of the mouse. FEBS Letters. 1985;188(2):257–261. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puchalski W., Bockler H., Heldmaier G., Langefeld M. Organ blood flow and brown adipose tissue oxygen consumption during noradrenaline-induced nonshivering thermogenesis in the Djungarian hamster. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1987;242(3):263–271. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402420304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merlin J., Sato M., Nowell C., Pakzad M., Fahey R., Gao J. The PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone promotes the induction of brite adipocytes, increasing β-adrenoceptor-mediated mitochondrial function and glucose uptake. Cellular Signalling. 2018;42:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marette A., Bukowiecki L.J. Stimulation of glucose transport by insulin and norepinephrine in isolated rat brown adipocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257(4 Pt 1):C714–C721. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.4.C714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chernogubova E., Cannon B., Bengtsson T. Norepinephrine increases glucose transport in brown adipocytes via beta3-adrenoceptors through a cAMP, PKA, and PI3-kinase-dependent pathway stimulating conventional and novel PKCs. Endocrinology. 2004;145(1):269–280. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernogubova E., Hutchinson D.S., Nedergaard J., Bengtsson T. Alpha1- and beta1-adrenoceptor signaling fully compensates for beta3-adrenoceptor deficiency in brown adipocyte norepinephrine-stimulated glucose uptake. Endocrinology. 2005;146(5):2271–2284. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nedergaard J., Bengtsson T., Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;293(2):E444–E452. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cypess A.M., Lehman S., Williams G., Tal I., Rodman D., Goldfine A.B. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(15):1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito M., Okamatsu-Ogura Y., Matsushita M., Watanabe K., Yoneshiro T., Nio-Kobayashi J. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1526–1531. doi: 10.2337/db09-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Marken Lichtenbelt W.D., Vanhommerig J.W., Smulders N.M., Drossaerts J.M., Kemerink G.J., Bouvy N.D. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(15):1500–1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virtanen K.A., Lidell M.E., Orava J., Heglind M., Westergren R., Niemi T. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(15):1518–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andjelkovic M., Alessi D.R., Meier R., Fernandez A., Lamb N.J., Frech M. Role of translocation in the activation and function of protein kinase B. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(50):31515–31524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen J.M., Sato M., Dallner O.S., Sandstrom A.L., Pisani D.F., Chambard J.C. Glucose uptake in brown fat cells is dependent on mTOR complex 2-promoted GLUT1 translocation. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2014;207(3):365–374. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201403080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frojdo S., Vidal H., Pirola L. Alterations of insulin signaling in type 2 diabetes: a review of the current evidence from humans. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1792(2):83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grujic D., Susulic V.S., Harper M.E., Himms-Hagen J., Cunningham B.A., Corkey B.E. Beta3-adrenergic receptors on white and brown adipocytes mediate beta3-selective agonist-induced effects on energy expenditure, insulin secretion, and food intake. A study using transgenic and gene knockout mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(28):17686–17693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacPherson R.E., Castellani L., Beaudoin M.S., Wright D.C. Evidence for fatty acids mediating CL 316,243-induced reductions in blood glucose in mice. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;307(7):E563–E570. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00287.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albert V., Svensson K., Shimobayashi M., Colombi M., Munoz S., Jimenez V. mTORC2 sustains thermogenesis via Akt-induced glucose uptake and glycolysis in brown adipose tissue. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2016;8(3):232–246. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu D., Bordicchia M., Zhang C., Fang H., Wei W., Li J.L. Activation of mTORC1 is essential for beta-adrenergic stimulation of adipose browning. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2016;126(5):1704–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI83532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dallner O.S., Chernogubova E., Brolinson K.A., Bengtsson T. Beta3-adrenergic receptors stimulate glucose uptake in brown adipocytes by two mechanisms independently of glucose transporter 4 translocation. Endocrinology. 2006;147(12):5730–5739. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayakawa M., Kaizawa H., Moritomo H., Koizumi T., Ohishi T., Okada M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 4-morpholino-2-phenylquinazolines and related derivatives as novel PI3 kinase p110alpha inhibitors. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;14(20):6847–6858. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slot J.W., Geuze H.J., Gigengack S., Lienhard G.E., James D.E. Immuno-localization of the insulin regulatable glucose transporter in brown adipose tissue of the rat. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1991;113(1):123–135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsen J.M., Csikasz R.I., Dehvari N., Lu L., Sandström A., Öberg A.I. β3-adrenergically induced glucose uptake in brown adipose tissue is independent of UCP1 presence or activity: mediation through the mTOR pathway. Molecular Metabolism. 2017;6(6):611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Souza C.J., Hirshman M.F., Horton E.S. CL-316,243, a beta3-specific adrenoceptor agonist, enhances insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in nonobese rats. Diabetes. 1997;46(8):1257–1263. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.8.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida T., Sakane N., Wakabayashi Y., Umekawa T., Kondo M. Anti-obesity effect of CL 316,243, a highly specific beta 3-adrenoceptor agonist, in mice with monosodium-L-glutamate-induced obesity. European Journal of Endocrinology – European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 1994;131(1):97–102. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1310097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Candelore M.R., Deng L., Tota L., Guan X.M., Amend A., Liu Y. Potent and selective human beta(3)-adrenergic receptor antagonists. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;290(2):649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato M., Dehvari N., Oberg A.I., Dallner O.S., Sandstrom A.L., Olsen J.M. Improving type 2 diabetes through a distinct adrenergic signaling pathway involving mTORC2 that mediates glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4115–4129. doi: 10.2337/db13-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deiuliis J.A., Liu L.-F., Belury M.A., Rim J.S., Shin S., Lee K. β3-Adrenergic signaling acutely down regulates adipose triglyceride lipase in Brown adipocytes. Lipids. 2010;45(6):479–489. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3422-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alessi D.R., Andjelkovic M., Caudwell B., Cron P., Morrice N., Cohen P. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. The EMBO Journal. 1996;15(23):6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebner M., Sinkovics B., Szczygieł M., Ribeiro D.W., Yudushkin I. Localization of mTORC2 activity inside cells. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2017;216(2):343–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201610060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebner M., Lučić I., Leonard T.A., Yudushkin I. PI(3,4,5)P 3 engagement restricts Akt activity to cellular membranes. Molecular Cell. 2017;65(3):416–431. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.12.028. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lučić I., Rathinaswamy M.K., Truebestein L., Hamelin D.J., Burke J.E., Leonard T.A. Conformational sampling of membranes by Akt controls its activation and inactivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018;115(17):E3940–E3949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716109115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Gurmaches J., Tang Y., Jespersen N.Z., Wallace M., Martinez Calejman C., Gujja S. Brown fat AKT2 is a cold-induced kinase that stimulates ChREBP-mediated de novo lipogenesis to optimize fuel storage and thermogenesis. Cell Metabolism. 2018;27(1):195–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.10.008. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu Y., Saito M. Activation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis in recovery from anesthetic hypothermia in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261(2 Pt 2):R301–R304. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.2.R301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanssen M.J.W., Hoeks J., Brans B., van der Lans A.A.J.J., Schaart G., van den Driessche J.J. Short-term cold acclimation improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature Medicine. 2015;21(8):863–865. doi: 10.1038/nm.3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindquist J.M., Fredriksson J.M., Rehnmark S., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. Beta 3- and alpha1-adrenergic Erk1/2 activation is Src- but not Gi-mediated in Brown adipocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(30):22670–22677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909093199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nechad M., Nedergaard J., Cannon B. Noradrenergic stimulation of mitochondriogenesis in brown adipocytes differentiating in culture. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253(6 Pt 1):C889–C894. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.6.C889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]