Abstract

Since early times, the people of Morocco use medicinal and aromatic plants as traditional medicine to heal different human ailments. However, little studies have been made in the past to properly document and promote the traditional knowledge. This study was carried out in the Rif (North of Morocco), it aimed to identify medicinal and aromatic plant used by the local people to treat metabolic diseases, together with the associated ethnomedicinal knowledge. The ethnomedical information collected was from 582 traditional healers using semi-structured interviews, free listing and focus group. Family use value (FUV), use value (UV), plant part value (PPV), fidelity level (FL) and informant agreement ratio (IAR) were employed in data analysis. Medicinal and aromatic plant were collected, identified and kept at the natural resources and biodiversity laboratory, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra. During the present study 30 medicinal plant species belonging to 14 families has been documented. The most frequent ailments reported were diabetes (IAR = 0.98). The majority of the remedies were prepared from infusion (53.9%). Leaves were the most frequently used plant part (PPV 0.633) and Rosmarinus officinalis L. (UV = 0.325) was the specie most commonly prescribed by local herbalists. The results of this study showed that people living in the Rif of Morocco are still dependent on medicinal and aromatic plants. The documented plants can serve as a basis for further studies on the regions medicinal plants knowledge and for future phytochemical and pharmacological studies.

Keywords: Metabolism, Moroccan Rif, Medicinal and aromatic plants, Metabolic diseases

1. Introduction

People have long histories on the uses of traditional medicinal and aromatic plants for medical purposes in the world, and nowadays, this is highly actively promoted [1]. In all ancient civilizations and in all continents, one finds traces of this use. Thus, even today, despite the progress of pharmacology, the therapeutic use of plants is very present in some countries, especially in developing countries [2].

Morocco, by its biogeographical position, offers a very rich ecological and floristic diversity constituting a true plant genetic reserve, with about 4,500 species belonging to 940 genera and 135 families [3]. The mountainous regions of Rif and Atlas being the most important areas for endemism [3]. This biodiversity is characterized by a very marked endemism that [4] allows it to occupy a privileged place among the Mediterranean countries to be a which have a long medical tradition and traditional know-how based on medicinal plants [5]. Indeed, traditional medicine has always occupied an important place in the traditions of medication in Morocco and the Rif region is a concrete example. The analysis of the Moroccan medicinal bibliography shows that the data on regional medicinal plants are very fragmentary and dispersed. We believe that the heritage of the medicinal flora requires regular monitoring and evaluation in terms of quality and quantity.

Accordingly, we conducted this ethnobotanical study in the Rif, which has a considerable lithological, structural, biological and floristic diversity. The purpose of the present investigations was to evaluate medicinal plants that grow in the study area with the aim to contribute to indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants and to analyze the results concerning the existing relationships between medicinal species and metabolic diseases. Indeed, it is very important to transform this traditional knowledge into scientific knowledge in order to revalue it, to preserve it and use it rationally.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

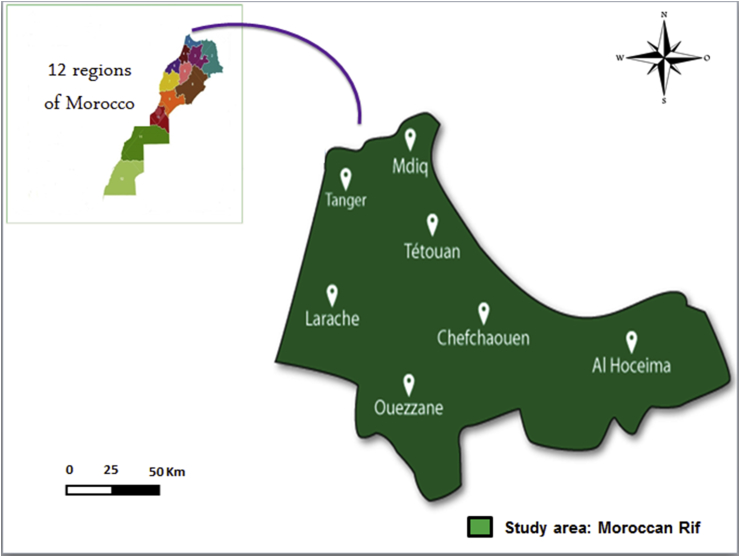

The present study was conducted in the Rif (northern Morocco) it is located on the Mediterranean coast, about 431 km at the north of Rabat, the administrative capital. The Rif is part of the region of Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima which is one of the twelve regions of Morocco established by the territorial division of 2015 [6]. This study area (between 34° to 36° N latitude and 4°–6° E longitude) is limited to the north by the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea, to the west by the Atlantic Ocean, to the south-west by the Rabat-Sale-Kenitra region, to the south-east by the Fez-Meknes region and to the east by the Eastern region. The region has two prefectures (Tangier-Asilah and M'Diq-Fnideq) and six provinces (Al Hoceima, Chefchaouen, Fahs-Anjra, Larache, Ouezzane and Tetouan) and the region's capital, Tangier-Asilah as shown in (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mapping representation of study area.

According to the 2014 national census report [7], the total area of study area is about 11,570 km2 with an average population density of 222.2/km2, and the human population is 3 549512. The study area has Mediterranean climate with maximum temperature beyond 45 °C during summer (July–August) and below 0 °C during winter (December–January) and annual rainfall is about 1000 mm. In the area, economy of the local people is very much dependent on subsistence agriculture, livestock and to a lesser extent, from forest resources for their livelihood. Inhabitants of the region use variety of medicinal plants for the treatment ailments due to expensive drugs.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Data collection tools and procedures

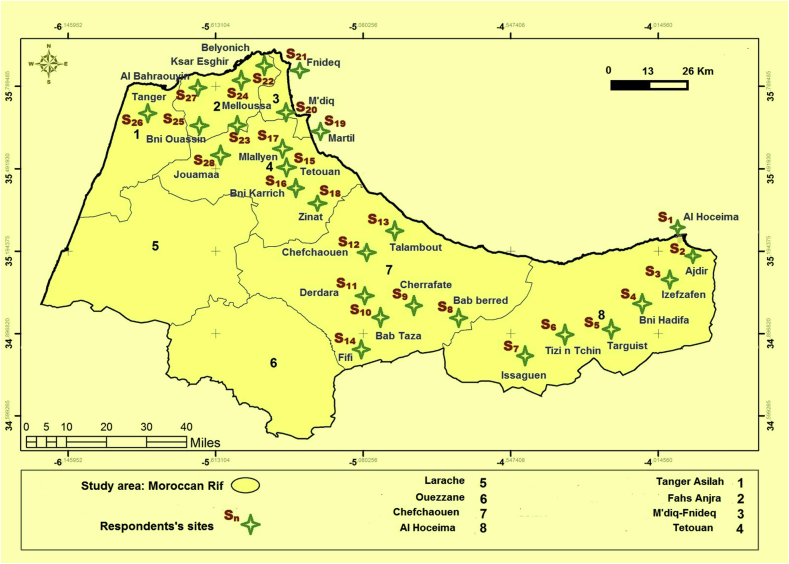

In order to gather information on medicinal plants used for treating metabolic disorders, an ethnobotanical survey was conducted from June 30th, 2016 to June 1st, 2018. Semi-structured questionnaires were administered and free listings were conducted, through face to face interviews and focus group, adopting the standard methodology followed by Martin [8]. The inclusion criteria: A lot of people may believe they are knowledgeable about plants used to treat nervous system disorders. It must be specified that qualified healthcare professionals such as “pharmacists, herbalists, practitioners and therapists” were selected for the study. While the exclusion criteria were informants who are not living in the study area. Totally, 582 informants within aged 17 to 92 were randomly selected for interviews (pharmacists, herbalists, practitioners and healers) in the study area (hospitals, pharmacies, houses, mosques, and weekly markets). The healthcare professionals were informed about the objective of this study, after having them sign a consent form, they were regularly to collect and document indigenous knowledge of plants usage against metabolic diseases. The questionnaire used consists of two parts: the first part deals with the demographic characteristic of the informants and the second one focuses on the plants used in the treatment of the diseases (Appendix A). The sample is made up of 311 females and 271 males from different socio-economic strata, chosen at random from the Rif's population. In this study, the sample is developed using a stratified random sampling method [9] to conduct various surveys from a site to another in the study area. According to this sampling method, we have divided our study area into sites (Sn), so we have 28 sites that correspond to the number of divisions in the study area (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of survey points at the study area level.

2.2.2. Plant species identification and preservation

Standard method was followed with record to collection of plant materials, drying, mounting, preparation and preservation of plant specimens [10]. All data collections were done with special care on the base of the cultural view of the local sites in the study area. The plant species collected during surveys were arranged alphabetically by family name, vernacular name/scientific name and ethnomedicinal uses. These plants were identified using standard floras available in this area of Morocco, including: The medicinal plants of the Morocco [11], Practical flora of Morocco [12] and Catalogs of vascular plants of northern Morocco volumes I and II [13]. Further, taxonomic names of plant species were confirmed at resources and biodiversity laboratory, Ibn Tofail University Kenitra, Morocco, from online databases namely: The Plant List (http://www.theplantlist.org) and the Kew Botanic Garden medicinal Plant Names services (http://www.kew.org/mpns). All the preserved specimens were deposited at the Herbarium of Ibn Tofail University.

2.2.3. Ethics statement and consent to participate

Approval for this study was granted by the Committee for ethical research of the department of biology, Ibn Tofail University. Before initiating data collection, we obtained oral informed consent in each case on a site level and then individually prior to each interview. Informants were also informed that the objectives of the research were not for commercial purposes but for academic reasons. Participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in this study; they were free to withdraw their information at any point of time. Finally, informants were accepted the idea and they have clearly agreed to have their names and personal data to be published.

2.2.4. Data analysis

A descriptive and quantitative statistical method was used to analyze the socio-demographic data of the informants (ANOVA One-way and Independent Samples T-Test, P-values of 0.05 or less were considered significant). The results of the ethnobotanical survey were analyzed using the Family Use Value (FUV), Use Value (UV), Plant Part Value (PPV), Fidelity Level (FL) and Informant Agreement Ratio (IAR). All statistical analyses were carried out with Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 21 and Microsoft Excel 2010.

2.2.4.1. Family use value (FUV)

The FUV identify the significance of plant families. It is as an index of cultural importance which can be applied in ethnobotany to calculate a value of biological plant taxon. To calculate FUV, we use the following formula: Where UVs = UV is the number of informants mentioning the family and Ns is the total number of species within each family [14].

2.2.4.2. Use value (UV)

The use value of species (UV), a quantitative method that demonstrates the relative importance of species known locally [15], was also calculated according to the following formula: . Where is the number of use reports mentioned by each informant (i) and N is the total number informants interviewed for a given plant species.

2.2.4.3. Plant part value (PPV)

Plant part value (PPV) was calculated using the following formula: Where RU is the number of uses reported of all parts of the plant and RUplant part is the sum of uses reported per part of the plant. The part with the highest PPV is the most used by the respondents.

2.2.4.4. Fidelity level (FL)

Fidelity level (FL) is the percentage of informants who mentioned the uses of certain plant species to treat a particular ailment in the study area. The FL index is calculated using this formula [16]: . Where Ip is the number of informants who independently indicated the use of a species for the same major ailment and Iu the total number of informants who mentioned the plant for any major ailment.

2.2.4.5. Informant agreement ratio (IAR)

The IAR for each use category in the four countries of investigation were calculated using the following formula [17]: . Where IAR is the Informant Agreement Ratio, Nur is the number of mentions in each category and Nt is the number of taxa used in each category. The values for the factor range from 0 to 1.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Socio-demographic features of the informants

In total, 582 local informants including 311 females and 271 males (with a sex ratio female/male of 1.15) were interviewed. In the Rif, herbs work for the treatment of conditions for both genders. However, women have a greater knowledge on the plant species and their use with a predominance of 53.4% against a percentage of 46.6% among men though the test (independent sample t test) did not show a significant difference (P = 0.494) between male and female informants on the number of medicinal plant species they listed and associated uses reported. This predominance of females can be explained by the vigilance of women for the balance of the disease, and their attachment to all that is traditional; indeed, it is women who give sustenance and healthcare to their families in case of an illness. These results confirm the results of other ethnobotanical work carried out at national scale [18, 19, 20, 21].

In the study area, the majority of the ages of the respondents ranged between 40 and 60 (50.7%) followed by informants who were older than 60 years (23%) and informants who were between 20 and 40 years of age (22.8%). Finally informants with an age less than 20 come in last position (3.5%) (Table 1). The difference between age groups and indigenous knowledge was significant (P = 0.000). The highest age respondents provide more reliable information because they hold much of the ancestral knowledge that is part of the oral tradition. So there is a loss of information on medicinal plants, which can be explained by the mistrust of certain young people, who tend not to believe this herbal medicine due to the influence of modernization and exotic culture influence. At present, the traditional medical knowledge transmitted from generation to generation is in danger, because transmission between old people and younger generation is not always assured [22]. These values confirm the results obtained in other regions of Morocco [20, 23, 24].

Table 1.

Demographic profile of informants interviewed.

| Variables | Catrgories | Total | Percentages (%) | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 311 | 53.4 | 0.494 |

| Male | 271 | 46.6 | ||

| Age | <20. years | 20 | 3.5 | 0.000 |

| 20–40 | 133 | 22.8 | ||

| 40–60 | 134 | 23 | ||

| >60 years | 295 | 50.7 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 425 | 73.6 | 0.000 |

| Divorced | 97 | 16.6 | ||

| Widower | 46 | 8 | ||

| Single | 14 | 2.3 | ||

| Educational status | Illiterate | 412 | 70.8 | 0.000 |

| Primary | 124 | 21.3 | ||

| Secondary | 42 | 7.2 | ||

| University | 4 | 0.7 | ||

| Income/month | Unemployed | 210 | 36.1 | 0.000 |

| 250 - 1500 MAD | 270 | 46.3 | ||

| 1500 - 5000 MAD | 93 | 16 | ||

| >5000 MAD | 9 | 1.6 |

The analysis of the collected data shows that, medicinal plants are much more used by married (73.1%) than by divorced (16.6%), knowing that widowers have a percentage of 8% and only 2.3% for singles, because the married people can avoid or minimize the material charges required by the doctor and the pharmacist. The difference between family status and indigenous knowledge for the treatment of metabolic diseases was statistically significant (P = 0.000). Those findings coincide with those of similar study conducted by El Hilah et al [25] in the central plateau of Morocco.

Regarding the level of education, more than half of the informants (70.8%) were illiterate, and 21.3% of the informants had been primary school, 7.2% of the informants had been secondary school. Nevertheless, informants with a university level education use little medicinal plants (0.7%). Thus, the difference between educational level and indigenous knowledge was significant (P = 0.000). We can therefore see that the use of medicinal plants decreases as the level of study increases. This result is similar to the findings reported [25, 26, 27].

In our study, 46.3% of the interviewees had a low socio-economic level, 36.1% were unemployed, 16% with average level, and only 1.6% with higher level. The difference between income/month and indigenous knowledge was significant (P = 0.000). The high cost of modern medical treatments and their side effects are among the main reasons why respondents used herbal medicine. We can therefore see that the use of plants increases with the increase in monthly income of these informants. These results are similar to those obtained in Moyen Moulouya of Morocco by Douiri [28].

3.2. Quantitative analyse

3.2.1. Most used families and their family use value (FUV)

A total of 30 medicinal plants species belonging to 14 botanical families were used to treat digestive system diseases in the study area. These plants are presented in alphabetical order. For each plant listed, we give the scientific name, the family, the local name, the part used, the method of preparation adopted by the local population, as well as the data of FUV, UR, UV and FL are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of medicinal plants used to cure metabolic diseases in the Rif region, Morocco.

| Scientific names of species and families | Local name | Parts used | Preparation | Medicinal uses | FL | UR | UV | FUV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | 0.01 | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris L. | Lbarba | Seed | Infusion | AN | 100 | 06 | 0.01 | |

| Apiaceae | 0.018 | |||||||

| Ferula communis L. | Lkalkha | Leaf | Decoction | HT | 100 | 04 | 0.007 | |

| Ridolfia segetum (L.) Moris | Slilo | Leaf | Cooked | DT, HC | 70.6 | 17 | 0.029 | |

| Asteraceae | 0.060 | |||||||

| Lactuca sativa L. | Elkhass | Leaf | Infusion | AN | 100 | 22 | 0.038 | |

| Calendula arvensis M.Bieb. | Jemra, Azwiwel | Flower | Infusion | DT | 100 | 96 | 0.165 | |

| Helianthus annuus L. | Abbad Shems | Seed | Infusion | AN | 100 | 21 | 0.036 | |

| Sonchus tenerrimus L. | Tifaf | Leaf | Decoction | AN, OB, HT | 48 | 25 | 0.043 | |

| Sonchus asper (L.) Hill | Tifaf | Whole plant | Decoction | HT | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Tanacetum vulgare L. | Lbalssem | Leaf | Infusion | DT, AN, HC | 52.4 | 42 | 0.072 | |

| Brassicaceae | 0.029 | |||||||

| Anastatica hierochuntica L. | Kaff Mariam | Root | Decoction | AN, HC | 80 | 25 | 0.043 | |

| Brassica oleracea L. | Karnabite | Leaf | Other | AN, OB | 77.8 | 09 | 0.015 | |

| Cucurbitaceae | 0.112 | |||||||

| Cucurbita pepo L. | Garaa Khedra | Fruit | Cooked | DT | 100 | 43 | 0.074 | |

| Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | Lhdej, Taferzizte | Seed | Infusion | DT | 100 | 09 | 0.015 | |

| Cupressaceae | 0.136 | |||||||

| Juniperus phoenicea L. | Arar Finiqi | Leaf | Decoction | DT | 100 | 79 | 0.136 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | 0.002 | |||||||

| Euphorbia peplis L. | Laaya, Haliba | Whole plant | Other | OB | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Fabaceae | 0.02 | |||||||

| Lupinus pilosus L. | Rjel Djaja | Seed | Infusion | DT | 100 | 07 | 0.012 | |

| Acacia albida Delile | Chok Telh | Root | Decoction | OB | 100 | 02 | 0.003 | |

| Phaseolus aureus Roxb. | Soja | Seed | Decoction | HC | 100 | 02 | 0.003 | |

| Phaseolus vulgaris L. | Loubya | Seed | Cooked | AN | 100 | 36 | 0.062 | |

| Fumariaceae | 0.002 | |||||||

| Fumaria officinalis L. | Hchicht Essibyan | Root | Decoction | HT | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Lamiaceae | 0.177 | |||||||

| Marrubium vulgare L. | Merriwta Hara, Ifzi | Leaf | Infusion | OB | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Salvia officinalis L. | Salmiya | Leaf | Infusion | AN | 100 | 119 | 0.205 | |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Azir, Yazir, | Leaf | Infusion | DT | 100 | 189 | 0.325 | |

| Linaceae | 0.112 | |||||||

| Linum usitatissimum L. | Zeri't El Kettan | Seed | Cooked | DT | 100 | 65 | 0.112 | |

| Moraceae | 0.083 | |||||||

| Ficus carica L. | Karmous, Chriha | Leaf | Infusion | DT, HC | 70 | 10 | 0.0172 | |

| Ficus abelii Miq. | Karmous, Chriha | Leaf | Decoction | DT | 100 | 103 | 0.177 | |

| Ficus dottata Gasp. | Karmous, Chriha | Fruit | Other | HC | 100 | 11 | 0.019 | |

| Morus alba L. | Ettout | Leaf | Infusion | DT, AN, OB | 58.8 | 68 | 0.117 | |

| Portulacaceae | 0.009 | |||||||

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Rejla, Tasmamine | Leaf | Cooked | HC | 100 | 05 | 0.009 | |

| Rosaceae | 0.130 | |||||||

| Malus domestica Borkh. | Tûffah | Fruit | Other | DT | 100 | 76 | 0.130 | |

DT: Diabetes, AN: Anemia, HC: Hypercholesterolemia, OB: Obesity, HT: Hyperthyroidism.

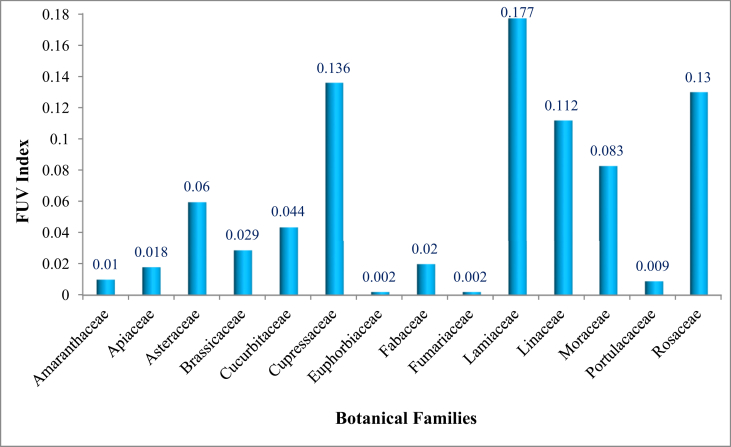

The most representative families, in terms of number of species, were Asteraceae (6 species each) followed by Fabaceae and Moraceae (4 species each) and Lamiaceae (03 species), while other families were represented by two or single species (Fig. 3). Based on the FUV index, The 5 most cited families are Lamiaceae (FUV = 0.177), Cupressaceae (FUV = 0.136), Rosaceae (FUV = 0.130), Linaceae (FUV = 0.112) and Moraceae (FUV = 0.083). This high proportion could be explained by the high representation of these families in the Rif's flora because of the ecological factors that favour the development and adaptation of the majority of their species. This partially coincides with the findings in other territories with similar characteristics [19, 29, 30, 31].

Fig. 3.

Family use value (FUV) of medicinal plants.

3.2.2. Diversity of medicinal plants and their UV values

To evaluate the relative importance of reported medicinal plants use value (UV) were calculated based on the informants' citations for specific under study plant, its value ranged from 0.002 to 0.325 (Table 2). Results of this study depicted that Rosmarinus officinalis L. exhibited the higher UV (0.325), followed by the Salvia officinalis L. (UV = 0.205), Ficus abelii Miq. (UV = 0.177) and Calendula arvensis M.Bieb. (UV = 0.165). The least UV was exhibited by 3 plant species (UV = 0.002 each). These species had the highest UV index, because these plants were mentioned by a large number of informants and UV directly depends on the number of informants mentioning the use of a specific plant. Those medicinal plant species having high UV must be further assessed for phytochemical and pharmaceutical analysis to identify their active constituents for any drug extraction [15]. These species should also be prioritized for conservation as their preferred uses may place their populations under threat due to over harvesting.

3.2.3. Fidelity level index (FL)

The fidelity value FL is an important means to see for which ailment a particular species is more effective, FL values in this study varied from 48% to 100%. The study determined 19 species of plants with a FL of 100%, most of which were used in single ailment category with multiple informants, without considering plants that were mentioned only once for better accuracy (Table 2). In general, a FL of 100% for a specific plant indicates that all of the use-reports mentioned the same method for using the plant for treatment [32]. This information means that the informants in the Rif had a tendency to rely on one specific plant species for treating one certain ailment than for several ailments. There are 19 plant species highly cited for metabolic problems should be taken in further consideration and studies to evaluate more data regarding their efficacy and authenticity as reported and recommended in other studies. Besides, plants with low FL% should not be abandoned as dwindling to remark them to the future generation that it could increase the risk of gradual disappearance of the knowledge [33].

3.2.4. Disease categories and their IAR values

Informant agreement ratio (IAR) depends upon the availability of plants within the study area to treat diseases. The product of IAR ranges from 0 to 1. High value of IAR indicates the agreement of selection of taxa between informants, whereas a low value indicates disagreement. Recently agreement ratio analysis has been used as an important tool for the analysis of ethnobotanical data [34, 35]. In the present study, the IAR values ranged from 0.64 to 0.98 per uses categories (Table 3). The category with the highest degree of agreement from informants was diabetes disorders (0.98). The ranking followed with anemia (0.96), hypercholesterolemia (0.90), obesity (0.80) and hyperthyroidism (0.64). The IAR results of the study proved that diseases that were frequent in the Rif's area have the higher informant agreement ratio (values between 0.64 and 0.98). This high IAR values indicated reasonable reliability of informants on the use of medicinal plants species [36]. The informant agreement values also indicated that the people share the knowledge of the most important medicinal plants species to treat the most frequently encountered diseases in the study area. Therefore, species with high IAR are to be prioritized for further on pharmacological and phytochemical studies.

Table 3.

IAR values by categories for treating metabolic diseases.

| Categories | List of plant species used and number of uses | Nt | Nur | IAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes (DT) | Calendula arvensis M.Bieb. (96), Cucurbita pepo L. (43), Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. (9), Juniperus phoenicea L. (79), Lupinus pilosus L. (7), Rosmarinus officinalis L. (189), Linum usitatissimum L. (65), Ficus abelii Miq. (103), Malus domestica Borkh. (76), Morus alba L. (20), Tanacetum vulgare L. (10), Ficus carica L. (3), Ridolfia segetum (L.) Moris. (5). | 13 | 705 | 0.98 |

| Anemia (AN) | Beta vulgaris L. (6), Lactuca sativa L. (22), Helianthus annuus L. (21), Tanacetum vulgare L. (22), Phaseolus vulgaris L. (36), Salvia officinalis L. (119), Morus alba L. (40), Sonchus tenerrimus L. (8), Anastatica hierochuntica L. (5), Brassica oleracea L. (2). | 10 | 259 | 0.96 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (HC) | Ridolfia segetum (L.) Moris. (12), Anastatica hierochuntica L. (20), Phaseolus aureus Roxb. (2), Ficus carica L. (7), Ficus dottata Gasp. (11), Portulaca oleracea L. (5), Tanacetum vulgare L. (10). | 7 | 67 | 0.90 |

| Obesity (OB) | Sonchus tenerrimus L. (12), Brassica oleracea L. (7), Euphorbia peplis L. (1), Acacia albida Delile. (2), Marrubium vulgare L. (1), Morus alba L. (8). | 6 | 31 | 0.80 |

| Hyperthyroidism (HT) | Ferula communis L. (4), Sonchus asper (L.) Hill. (1), Fumaria officinalis L. (1), Sonchus tenerrimus L. (5). | 4 | 11 | 0.64 |

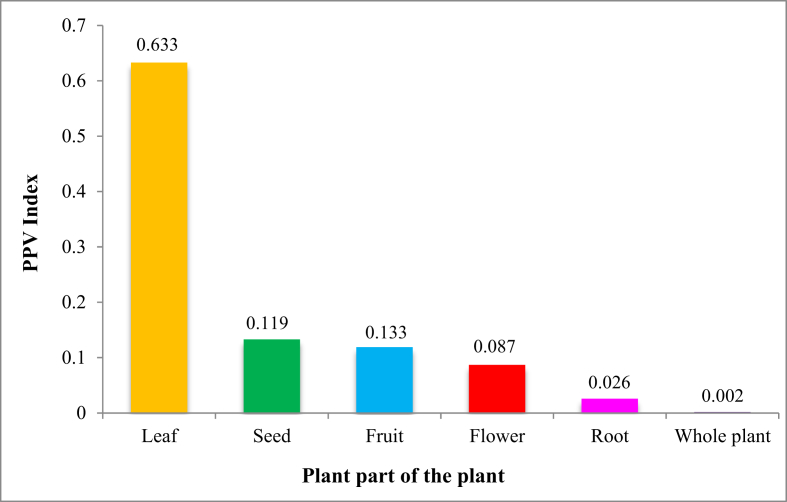

3.2.5. Parts of the medicinal plants used

People of the Rif harvest different plant parts for the preparation of traditional remedies (e.g., seed, root, flower, fruit, leaf and whole plant). Based on the plant part value PPV index, leaf was reported as the dominant plant part for metabolic remedy preparation in the study area (PPV 0.633), followed by seed (PPV 0.133), fruit (PPV 0.119), flower (PPV 0.087), root (PPV 0.026) and whole plant (PPV 0.002) respectively (Fig. 4). The preference of leaves was due to its easy availability, easy harvesting and simplicity in remedy preparation. In addition the leaves are the seat of the photosynthesis and sometimes the storage of the secondary metabolites responsible for biological properties of the plant. Similar findings indicated leaf as a major dominant plant part in Morocco [28, 37, 38] or in Africa [39, 40, 41, 42] for herbal medicine preparation.

Fig. 4.

Plant part used to treat metabolic diseases in the study area.

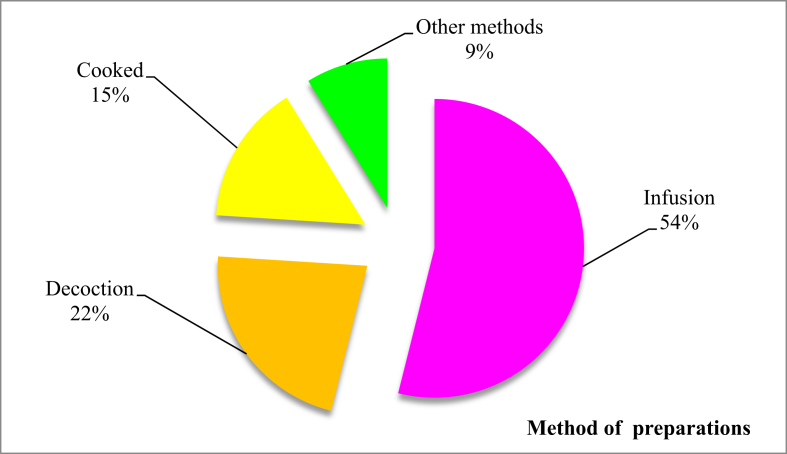

3.3. Methods of remedy preparations

In order to facilitate the administration of the active principles of the plant, several modes of preparation are employed to know the decoction, the infusion, cataplasm, raw, maceration, fumigation, inhalation and cooked. In the study area, information about the preparation of each plant has been included in Table 2. The results also showed that the majorities of remedies were prepared from infusion (53.9%) followed by decoction (22.1%) and cooked (15.16%). The percentage of the other methods of preparation grouped (fumigation, maceration, raw, inhalation, cataplasm) does not exceed 8.84% (Fig. 5). The frequent use of the infusion can be explained by the fact that the infusion makes it possible to collect the most active ingredients and attenuates or cancels out the toxic effect of certain recipes. Ethnobotanical research surveys conducted elsewhere in Morocco showed the majority of the interviewees prepared the remedy by infusion [21, 25, 43]. This confirms that there is a perpetual exchange of information on the use of medicinal plants between the people of Morocco. infusion mentioned as the major method of preparation at the continental level [44, 45, 46].

Fig. 5.

Frequency of different methods of preparation.

3.4. Routes of administration

Route of administration also varies depends on the disease and materials used. In general, most of the prepared recipes are orally prescribed (81.3%) followed by massage (9.6%), other modes of administration (4.8%), swabbing (2.5%) and rinsing (1.8%). The predominance of oral administration may be explained by a high incidence of internal ailments in the region [47]. On the other hand, it's thought that oral route is the most acceptable for the patient. The predominance of oral administration of the different medicinal plants in the Rif is in total agreement with most of the carried out ethnobotanical studies in Africa [20, 48, 49].

3.5. Conditions of medicine preparation

In the present investigations, the majority of the remedies (58.4%) in the study area were prepared from fresh parts of medicinal plants followed by dried form (40.2%) and only (1.4%) prepared either from dry or fresh plant parts. This indicates that fresh plants are much easier and quicker to prepare for remedy than the other forms. The study conducted by Abdurhman [50] indicated that 86% of preparations were in fresh form and Getahum [51] reported that most of (64%) medicinal plants were used in fresh form and 36% in dried from. The dependency of Moroccan Rif people on fresh materials is mostly due to the effectiveness of fresh medicinal plants in treatment as the contents are not lost before use compared to the dried forms.

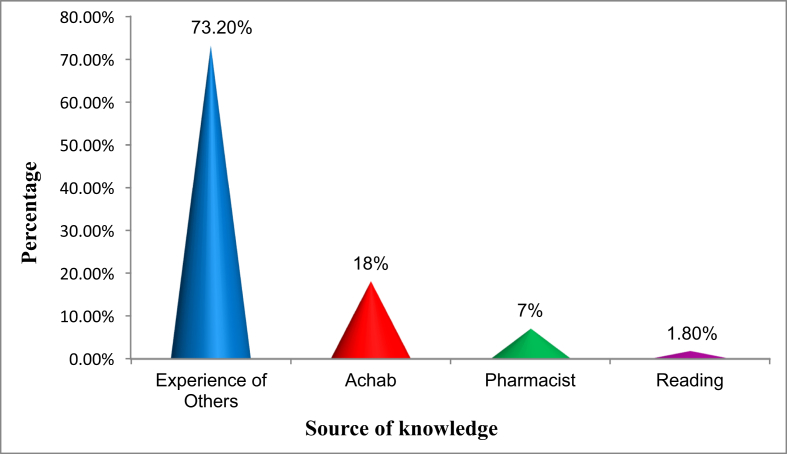

3.6. Source of knowledge about medicinal plants

In our ethnomedicinal survey, 73.2% of the informants acquired knowledge about medicinal use of plants as a remedy for metabolic diseases through others' experiences. This reflects the relative transmission of traditional practices from one generation to the next one. Followed by herbalists (18%), pharmacist (7%) and only 1.8% had built this knowledge by reading books about traditional Arab medicine, by watching television programs or by their own experience with a large number of medicinal plants in their surroundings. The environment and others' experience remain therefore the most effective means to transmit knowledge about medicinal purposes of plants (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Traditional knowledge acquisition modes.

4. Conclusion

The ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological surveys revealed that, the study area has a great biodiversity with a variety of medicinal and aromatic plants and still needs more explorations. This rich floral indicates the high potential of traditional knowledge to serve for the development of natural product-derivate as affordable medicines. These plants still play a crucial role of people in Moroccan Rif, but medicinal plants used to treat metabolic diseases in this region lacks ethno-medicinal evidence. On the basis of results of the present studies, higher use value, informant agreement ratio scores, and fidelity level values of the recorded medicinal plant species would empower the future pharmaceutical and phytochemical studies and conservation practices. In this connection, attention should be drawn to the conservations of traditional medicinal plants and associated indigenous knowledge in the Moroccan Rif area to sustain them in the future.

4.1. Limitations of the study

This study was limited to a part of Morocco (Moroccan Rif region). The same study in various parts of Morocco is suggested.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Noureddine Chaachouay: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ouafae Benkhnigue: Performed the experiments.

Mohamed Fadli: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Hamid El Ibaoui: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Lahcen Zidane: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our heartfelt thanks to all the leaders and residents of the Rif region for their help. To all sellers of medicinal and aromatic plants (Attar). We also extend our acknowledgements to all those who contributed to the realization of this work.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Mishra A.P. Bioactive compounds and health benefits of edible Rumex species-A review. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018;64(8):27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharifi-Rad M. Ethnobotany of the genus Taraxacum—phytochemicals and antimicrobial activity. Phytother Res. 2018;32(11):2131–2145. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matuhe . MATUHE/DE; Rabat — Maroc.: 2001. Rapport sur l’Etat de L’Environnement du Maroc. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghanmi M., Satrani B., Aberchane M., Ismaili M.R., Aafi A., El Abid A. Centre de Recherche Forestière. Rabat, Maroc; 2011. Plantes Aromatiques et Médicinales du Maroc, les milles et une vertu. 130 p. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scherrer A.M., Motti R., Weckerle C.S. 2005. Traditional Plant Use in the Areas of Monte Vesole and Ascea, Cilento National Park (Campania, Southern Italy) pp. 129–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulletin officiel . 2015. Bulletin officiel, Décret n° 2-15-40 du 1er joumada I 1436 (20 février 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 7.HCP . Direction Régionale de Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceima; Oct. 2018. Haut-commissariat au plan, Monograpie de la région Tanger Tétouan Al Hoceima. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin G.J. Earthscan Publ. Ltd; London: 2004. Ethnobotany: A Methods Manual; p. 01. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godron M. USTL; Montpellier, France: 1971. Essai sur une approche probabiliste de l’écologie des végétaux; p. 247. Thèse de Doctorat. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain S.K. The role of botanist in folklore research. Folklore. 1964;5(4):145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sijelmassi A. Casablanca Moroc; 1993. Les plantes médicinales du Maroc, 3ème édition Fennec. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fennane M., Tattou M.I., Mathez J., Quézel P. Institut scientifique; 1999. Flore pratique du Maroc: manuel de détermination des plantes vasculaires. Pteridophyta, Gymnospermae, Angiospermae (Lauraceae-Neuradaceae) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valdés B. vol. 1. Editorial CSIC-CSIC Press; 2002. (Catalogue des plantes vasculaires du Nord du Maroc, incluant des clés d’identification). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreekeesoon D.P., Mahomoodally M.F. Ethnopharmacological analysis of medicinal plants and animals used in the treatment and management of pain in Mauritius. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:181–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitalini S., Iriti M., Puricelli C., Ciuchi D., Segale A., Fico G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—an alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145(2):517–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman J., Yaniv Z., Dafni A., Palewitch D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;16(2–3):275–287. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinrich M., Ankli A., Frei B., Weimann C., Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers' consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998;47(11):1859–1871. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benkhnigue O., Zidane L., Fadli M., Elyacoubi H., Rochdi A., Douira A. Etude ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales dans la région de Mechraâ Bel Ksiri (Région du Gharb du Maroc) Acta Bot. Barcinonensia. 2010;53:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eddouks M., Maghrani M., Lemhadri A., Ouahidi M.-L., Jouad H. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiac diseases in the south-east region of Morocco (Tafilalet) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82(2-3):97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Hafian M., Benlandini N., Elyacoubi H., Zidane L., Rochdi A. Étude floristique et ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales utilisées au niveau de la préfecture d’Agadir-Ida-Outanane (Maroc) J. Appl. Biosci. 2014;81(1):7198–7213. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salhi S., Fadli M., Zidane L., Douira A. Etudes floristique et ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales de la ville de Kénitra (Maroc) Lazaroa. 2010;31:133. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anyinam C. 1995. Ecology and Ethnomedicine. Exploring Links Between Current Environmental Crisis and Indigenous Medical Practices. p. 4, 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aribi I. 2013. Etude ethnobotanique de plantes médicinales de la région du Jijel: étude anatomique, phytochimique, et recherche d’activités biologiques de deux espèces. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benlamdini N., Elhafian M., Rochdi A., Zidane L. Étude floristique et ethnobotanique de la flore médicinale du Haut Atlas oriental (Haute Moulouya) J. Appl. Biosci. 2014;78(1):6771–6787. [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Hilah F.B.A., Dahmani J., Belahbib N., Zidane L. Étude ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales utilisées dans le traitement des infections du système respiratoire dans le plateau central marocain. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2015;25(2):3886–3897. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouzid A., Chadli R., Bouzid K. Étude ethnobotanique de la plante médicinale Arbutus unedo L. dans la région de Sidi Bel Abbés en Algérie occidentale. Phytothérapie. 2017;15(6):373–378. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahsissene H., Kahouadji A., Hseini S. Lejeunia Rev. Bot.; 2009. Catalogue des plantes medicinales utilisees dans la region de Zaër (Maroc Occidental) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Douiri E., El Hassani M., Bammi J., Badoc A., Douira A. Plantes vasculaires de la Moyenne Moulouya (Maroc oriental) Bull. Soc. Linn Bordx. 2007;142:409–438. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonet M. Univ. Barc.; 2001. Estudi etnobotànic del Montseny. (Ph. D. thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jouad H., Haloui M., Rhiouani H., El Hilaly J., Eddouks M. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes, cardiac and renal diseases in the North centre region of Morocco (Fez–Boulemane) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;77(2–3):175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tahraoui A., El-Hilaly J., Israili Z.H., Lyoussi B. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used in the traditional treatment of hypertension and diabetes in south-eastern Morocco (Errachidia province) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110(1):105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srithi K., Balslev H., Wangpakapattanawong P., Srisanga P., Trisonthi C. Medicinal plant knowledge and its erosion among the Mien (Yao) in northern Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123(2):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhary N.I., Schnapp A., Park J.E. Pharmacologic differentiation of inflammation and fibrosis in the rat bleomycin model. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;173(7):769–776. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-717OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uprety Y., Asselin H., Boon E.K., Yadav S., Shrestha K.K. Indigenous use and bio-efficacy of medicinal plants in the Rasuwa District, Central Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010;6(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uniyal S.K., Sharma V., Jamwal P. Folk medicinal practices in Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh, western Himalaya. Hum. Ecol. 2011;39(4):479–488. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin J., Puckree T., Mvelase T.P. Anti-diarrhoeal evaluation of some medicinal plants used by Zulu traditional healers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daoudi A., Bammou M., Zarkani S., Slimani I., Ibijbijen J., Nassiri L. Étude ethnobotanique de la flore médicinale dans la commune rurale d’Aguelmouss province de Khénifra (Maroc) Phytothérapie. 2016;14(4):220–228. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hachi M., Hachi T., Belahbib N., Dahmani J., Zidane L. ‘contribution à l’etude floristique et ethnobotanique de la flore médicinale utilisée au niveau de la ville de khenifra (Maroc)’. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2015;11(3):754. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asase A., Akwetey G.A., Achel D.G. Ethnopharmacological use of herbal remedies for the treatment of malaria in the Dangme West District of Ghana. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129(3):367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asnake S., Teklehaymanot T., Hymete A., Erko B., Giday M. Survey of medicinal plants used to treat malaria by Sidama people of Boricha district, Sidama Zone, south region of Ethiopia. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/9690164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukungu N., Abuga K., Okalebo F., Ingwela R., Mwangi J. Medicinal plants used for management of malaria among the Luhya community of Kakamega East sub-County, Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nouri J. Étude floristique et ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales au nord-ouest de la Tunisie: cas de la communauté d’Ouled Sedra. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Technol. 2016;3(1):281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slimani I. Étude ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales utilisées dans la région de Zerhoun-Maroc-[Ethnobotanical Survey of medicinal plants used in Zerhoun region-Morocco-] Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2016;15(4):846. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okello S.V., Nyunja R.O., Netondo G.W., Onyango J.C. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by Sabaots of Mt. Elgon Kenya. Afr. J. Tradit. Complementary Altern. Med. 2010;7(1) doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i1.57223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stangeland T., Alele P.E., Katuura E., Lye K.A. Plants used to treat malaria in Nyakayojo sub-county, western Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(1):154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yetein M.H., Houessou L.G., Lougbégnon T.O., Teka O., Tente B. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used for the treatment of malaria in plateau of Allada, Benin (West Africa) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;146(1):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Polat R., Satıl F. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Edremit Gulf (Balıkesir–Turkey) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139(2):626–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benarba B., Meddah B., Tir Touil A. Response of bone resorption markers to Aristolochia longa intake by Algerian breast cancer postmenopausal women. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014:2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/820589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chermat S., Gharzouli R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in the north east of Algeria-an empirical knowledge in Djebel Zdimm (Setif) J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015;5:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdurhman N. Addis Ababa Univ; 2010. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Local People in Ofla Wereda, Southern Zone of Tigray Region Ethiopia. MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Getahun A. Amare Getahun; 1976. Some Common Medicinal and Poisonous Plants Used in Ethiopian Folk Medicine. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.