Abstract

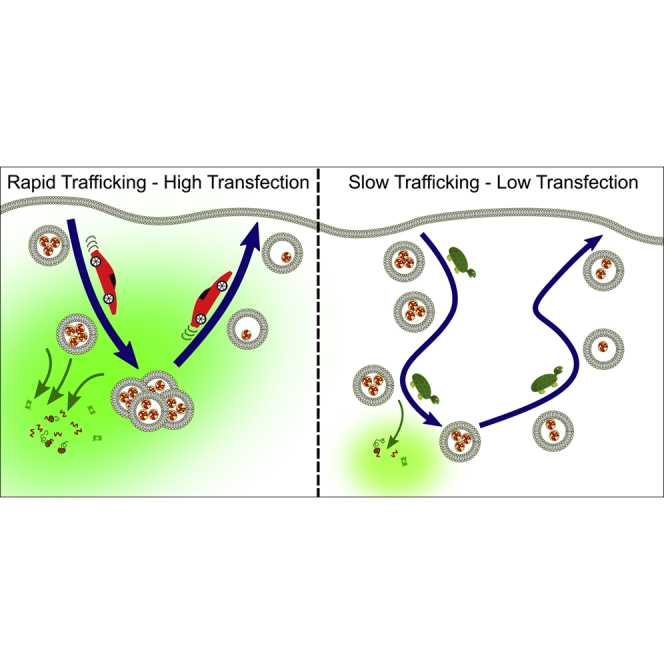

Lipid nanoparticles have great potential for delivering nucleic-acid-based therapeutics, but low efficiency limits their broad clinical translation. Differences in transfection capacity between in vitro models used for nanoparticle pre-clinical testing are poorly understood. To address this, using a clinically relevant lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivering mRNA, we highlight specific endosomal characteristics in in vitro tumor models that impact protein expression. A 30-cell line LNP-mRNA transfection screen identified three cell lines having low, medium, and high transfection that correlated with protein expression when they were analyzed in tumor models. Endocytic profiling of these cell lines identified major differences in endolysosomal morphology, localization, endocytic uptake, trafficking, recycling, and endolysosomal pH, identified using a novel pH probe. High-transfecting cells showed rapid LNP uptake and trafficking through an organized endocytic pathway to lysosomes or rapid exocytosis. Low-transfecting cells demonstrated slower endosomal LNP trafficking to lysosomes and defective endocytic organization and acidification. Our data establish that efficient LNP-mRNA transfection relies on an early and narrow endosomal escape window prior to lysosomal sequestration and/or exocytosis. Endocytic profiling should form an important pre-clinical evaluation step for nucleic acid delivery systems to inform model selection and guide delivery-system design for improved clinical translation.

Keywords: lipid nanoparticle, LNP, endocytosis, transfection, recycling, mRNA, nucleic acid, pH sensor

Graphical Abstract

Lipid nanoparticles are promising vectors for delivery of macromolecular therapeutics, such as mRNA. Pre-clinical testing of vectors relies on cell models of disease, such as cancer. Here, using high-content endocytic profiling in different cell types, we have identified key endocytic features that are critical to effective cytosolic delivery of mRNA.

Introduction

mRNA-based therapeutics are an important emerging class of drugs1, 2, 3 designed to produce therapeutic proteins. They provide a promising alternative approach for the treatment of diseases where conventional drugs have been unsuccessful. mRNA-based therapeutics, unlike DNA-based therapeutics, do not require nuclear delivery, thus minimizing the risk of genomic integration, and have the additional advantage that protein expression is triggered almost immediately after cytosolic entry.4

The unmet major challenge for mRNA and other nucleic-acid-based therapeutics is achieving effective intracellular delivery, such that sufficient cargo enters the cytosol to mediate a biological and thus therapeutic effect. Chemical modifications to RNA confer increased stability and reduced immunogenicity, thereby facilitating expression of a range of therapeutic proteins.5 However, delivering long, negatively charged nucleic acids into the cytosol of target cells while avoiding degradation still represents a significant challenge.

Both viral6 and non-viral7 delivery vectors have been extensively investigated for nucleic-acid-based therapies and some have progressed to clinical trials. Non-viral delivery systems such as lipids and polymers can complex with nucleic acids, mediate endocytic cell uptake and facilitate endosomal escape.8, 9, 10 Lipid-based nanoparticles (LNPs), consisting of an ionizable cationic lipid, cholesterol, phospholipid, and a poly(ethylene glycol) lipid, have received a great deal of research interest and have progressed into a number of clinical trials7, 11 and Onpattro (patisiran) has been recently being approved for delivery of small interfering RNA (siRNA) to liver for treatment of polyneuropathy of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (https://www.alnylam.com/our-products/).12 Post-systemic administration, LNPs are thought to undergo relatively rapid desorption of the polyethyleneglycol (PEG) lipid, adsorption of ApoE and other plasma proteins, followed by intracellular uptake through LDL or related receptors.13 The ionizable lipid component of the LNP is the main driver facilitating pH-dependent endosomal escape and cytosolic availability of the payload. Upon exposure to acidic pHs in the endolysosomal system, LNPs interact with counter-charged anionic lipids of the inner endosomal membrane and create fusogenic hexagonal non-bilayer structures that facilitate cargo release.12, 14 The ionizable cationic lipid DLin-MC3-DMA, pKa 6.4,15 was found to be the most potent lipid when formulated into LNPs with both siRNA15 (gene silencing) and mRNA16 (protein expression) in vitro and in vivo.

Cell culture systems still represent important pre-clinical models to assess target engagement and the delivery efficiency of drug delivery formulations in vitro. Obtaining closer in vitro-in vivo correlation is required to accelerate the translation of intracellular therapeutics from bench to bedside. This requires a high level of understanding of the interaction between formulations and cells, together with knowledge of the endolysosomal characteristics of any particular cell model. Hundreds of cell models are now available for pre-clinical testing, but very few studies have attempted to correlate productive delivery in different disease and clinically relevant cell types with high content endolysosomal analysis and profiling.

In this work, we evaluated DLin-MC3-DMA-containing LNPs for mRNA delivery to tumor cells, using mRNA encoding EGFP and observed significant differences in protein expression across 30 cell lines. Other studies have similarly reported that cell types vary widely in their ability to be transfected.17 However, the interplay of factors affecting mRNA transfection such as cell uptake, rates of intracellular trafficking, and especially pH profiles of the endolysosomal systems for different cell models have been largely unexplored and are critical for successful clinical translation of mRNA delivery systems.

Here, we focused on three cell line models: HCT116 (human colon epithelial), H358 (human lung epithelial), and CT26.WT (mouse colon fibroblast), representing high, medium, and low protein expressors following mRNA transfection and correlated these transfection levels in in vivo xenograft or syngeneic tumor models. We analyzed the endocytic characteristics of these lines in detail in a process we term endocytic profiling. We subsequently used endocytic profiling on all three cell lines and correlated the findings with mRNA delivery and protein expression. The capacity for transfection was independent of uptake levels but highly dependent on high rates of LNP endocytic traffic and recycling that occurs through various endolysosomal compartments of varying pH, measured utilizing a novel pH probe. These we find are key determining factors in the LNP-mediated functional delivery of mRNA into the cytosol.

Results

Multiple Cell Line Analysis and In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation

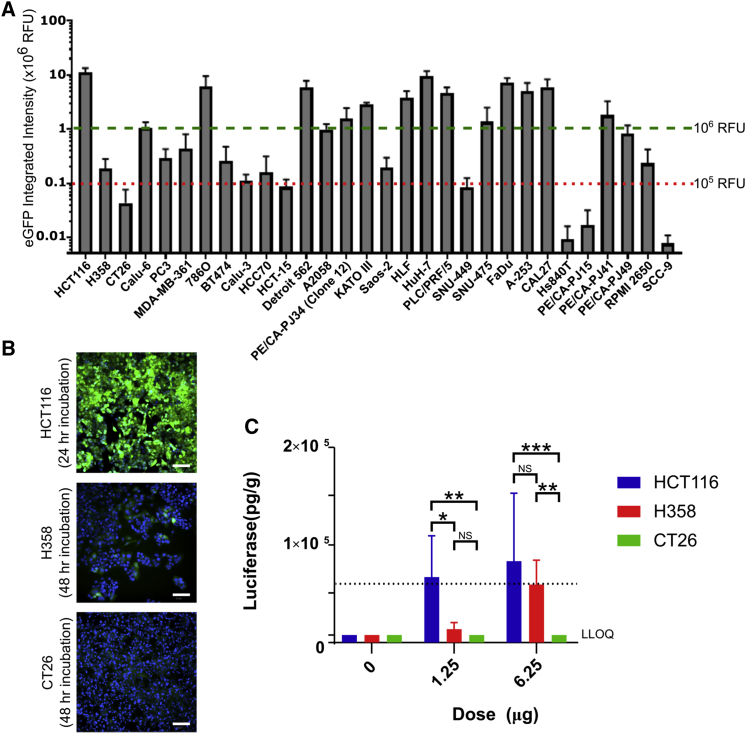

To screen for effective delivery of mRNA by our LNP we incubated LNPs containing EGFP encoding mRNA with 30 clinically relevant cell models; several of which were also routinely used as xenograft tumor models. LNPs formulated with 30 ng mRNA were incubated for periods between 0 and 48 h and imaged by automated microscopy (Figure 1A). Quantification of the images revealed a wide range of differences in effective mRNA delivery between these different cell models. These were defined as having high (>106 RFU), medium (105 to 106 RFU), or low (<105 RFU) EGFP expression. Over half of the cell lines analyzed showed medium or poor transfection, while high expressors included the human colon epithelial HCT116 and human hepatocyte HuH-7 cells. Interestingly, while there was great difference in expression levels between different cell types, levels within a single cell population remained relatively consistent, as shown for selected high- and low-expressing variants in Figure 1B. LNPs may interact with low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) via ApoE to gain cell entry.18 However, we found no correlation between transfection efficiency and LDLR and ApoE mRNA expression via Cancer Cell Line Encyclopaedia19 (Figure S1A). For ApoE, this was confirmed at the protein level in the three cell lines studied in detail (Figure S1B).

Figure 1.

LNP-Mediated Delivery of EGFP mRNA in In Vitro and In Vivo Tumor Models

(A) Cells were incubated with LNP containing mRNA expressing EGFP for 48 h. EGFP expression was captured every 4 h, and data shown is peak expression following the addition of 30 ng LNP/well. Values represent the mean, error bars the SEM. All data represents four independent experiments (run in duplicate) with the exception of HCC70 (n = 2), HS940T (n = 3), PE/CA-PJ15 (n = 2), and SCC-9 (n = 2). Cell lines above dashed green line are high expressors, and cell lines below dotted red line are low expressors; note log scale. (B) Cells were incubated with LNP containing mRNA expressing EGFP (green), fixed, and counterstained with Hoechst at 24 or 48 h post-LNP transfection and imaged on an ImageXpress at 10× magnification. (C) LNP containing luciferase mRNA were injected into HCT116, H358, and CT26.WT tumor sites of nude or BALB/c mice using a final volume of 30 μL per injection (LNP in PBS). The tumor was excised after 6 h and assayed for luciferase expression. LLOQ, lower level of quantification. p values calculated using two-way ANOVA; see Supplemental Information. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.01.

To gain mechanistic insights for differential transfection ability, we examined three cell models from Figure 1B in greater detail, selecting lines representing high (HCT116), medium (H358), and low (CT26.WT) protein expression. It was confirmed that exposure to LNP-mRNA over the 48-h period had no effect on growth rates in these cell lines (Figure S2). The translatability of differences in LNP performance between cell types from in vitro to in vivo was then investigated by establishing mouse xenograft or syngeneic models of the prioritized tumor types (HCT116, H358, and CT26.WT). Luciferase mRNA formulated in LNPs was administered via intra-tumoral injection to maximize efficacy and minimize the impact of physiological barriers, which could affect LNP performance. This allowed any differences between tumor types to be more reliably attributed to the tumor cell type. Mice were sacrificed after 6 h and tumors excised from the animals were homogenized and assayed for luciferase expression. For the three cell lines, there was parity between protein expression observed in vitro to that observed in vivo. No detectable protein expression was observed in the CT26.WT model at any dose, whereas significantly higher levels of protein expression were measured in the HCT116 compared to H358 (p = 0.011) and CT26.WT (p = 0.004) in the low (1.25 μg)-dose group. At the higher 6.25-μg dose, both HCT116 and H358 xenografts showed high levels of expression, with CT26.WT remaining below detection levels.

LNPs have been shown to accumulate in the liver,20 and luciferase expression was therefore tested in the liver to see if this could account for differences in transfection (Figure S3). At low doses, there was no correlation between luminescence measured in the tumor and that measured in the liver, indicating that the lower fluorescence is not due to LNP liver accumulation. At the higher dose, there was evidence of LNP accumulation in the liver of H358 xenograft mice, and this was significantly higher than the other two models (p < 0.001 in both cases). This may be due to differences in tumor architecture where interstitial pressure buildup forces the LNP out of the tumor site. High liver expression was accompanied by high luciferase expression in the tumor.

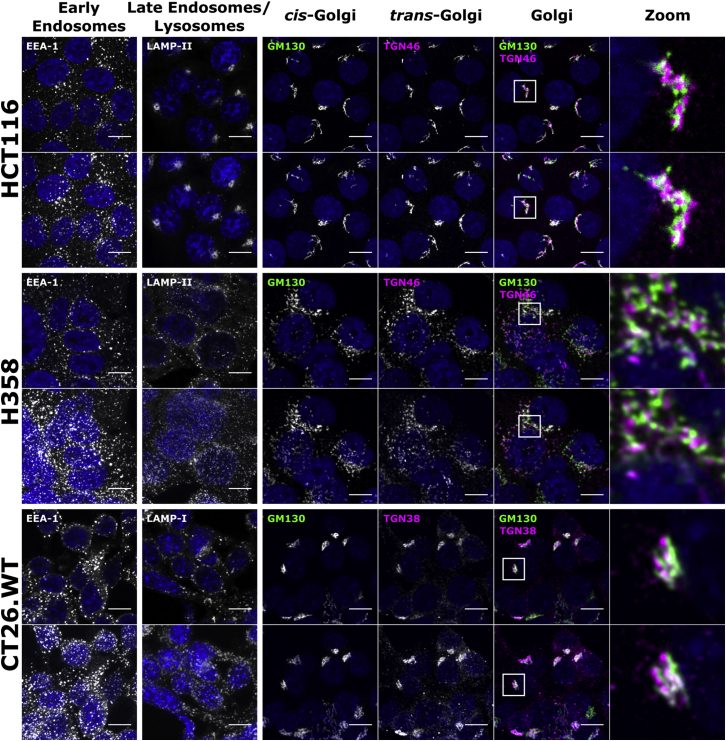

Endocytic Profiling

LNPs are known to enter cells via endocytosis.13 We hypothesized that phenotypic differences across cells could explain the differences in their transfection capabilities, and we investigated the distribution of organelles using immunofluorescence microscopy. These ranged from early endosomes to lysosomes and structures such as the tubulin cytoskeleton, which influences the distribution and function of these compartments.21, 22 Early endosomes (EEA-1) were generally scattered in the cytoplasm in all models, with some enrichment in a juxtanuclear region in HCT116 cells (Figure 2). There was, however, a major difference in organization of late endosomes and lysosomes (LAMPI/II) between the high and the low and medium transfectors. These organelles were very tightly packed in a juxtanuclear region in HCT116 cells but were scattered in the H358 and CT26.WT lines. The cis and trans sections of the Golgi complex (GM130 and TGN46/38, respectively) were examined, showing the typical polarized, juxtanuclear cluster in HCT116 and CT26.WT cells but with an unusual scattered distribution in H358 cells.

Figure 2.

Organelle Distribution in HCT116, H358, and CT26.WT Cells by Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown for 48 h before fixing; labeling early endosomes, lysosomes, and Golgi structures; and imaging by confocal microscopy. Upper row represents single sections; lower row represents maximum projection images of the same region. Scale bar, 10 μm; for a wider field of view, see Figure S4.

Endolysosomal organization and function is regulated by microtubules that stem from the centrosome, located near the nucleus, and serves as the microtubule organizing center (MTOC). This structure can be immune visualized by labeling pericentrin, a known component of the MTOC.23 Surprisingly, microtubule organization was similar among the three cell types (Figure S5), but H358 cells were characterized by the presence of two or three MTOCs located close to each other in the majority of cells, an effect often observed in cancer cells.23

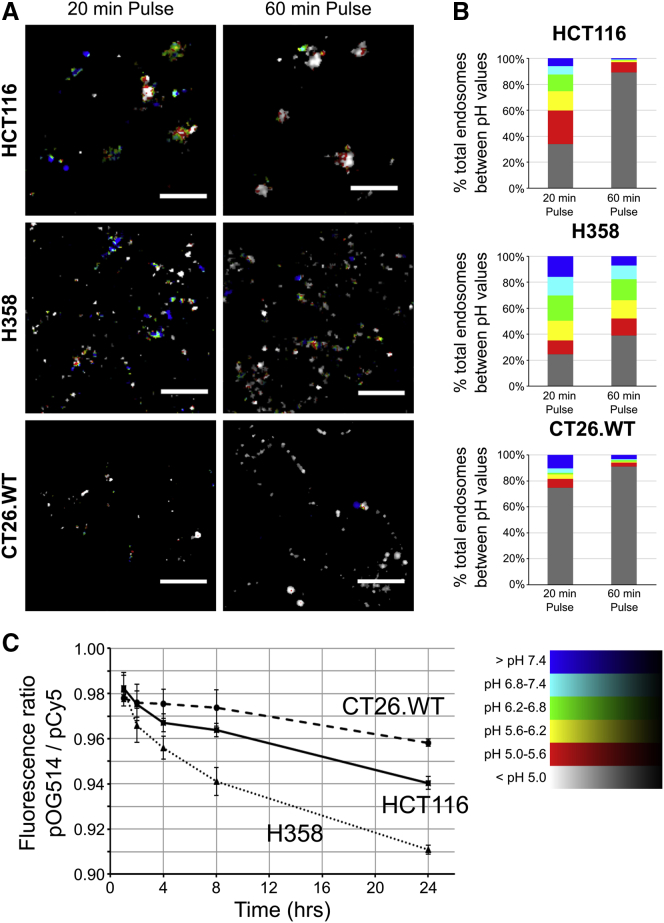

Endocytic pH Analysis

Endolysosomal mRNA escape by this LNP is pH dependent, and we evaluated the pH of the endolysosomal system in the three cell lines to identify any differences. This was performed using dextran, a commonly used drug delivery vector,24 that is known to traffic in the fluid phase from plasma membrane to lysosomes.25 For this, in live cells, we used dual-labeled 10-kDa dextran (Dex) tagged with pH-sensitive (fluorescein, Fluo) and insensitive (tetramethylrhodamine [Rhod]) fluorophores. Endocytosed dual-labeled Fluo-Dex-Rhod probe can only provide pH responses between pH 7.4 and 5.0 when measured against a pH calibration curve. Lower pHs produce a limited reduction in fluorescein fluorescence, limiting its use below pH 5.0.26 Using this probe, calibrated pH readings are fed back into captured microscopy images (Figure 3A) to provide a graphical-pictorial representation of both intracellular pH distribution and a quantitative pH analysis above pH 5.0 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Analysis of Endolysosomal pH in HCT116, H358, and CT26.WT Using Ratiometric Dextran Probes to Measure pH

(A and B) Cells were incubated with Fluo-Dex-Rhod for 20 or 60 min before imaging by confocal microscopy. Images were analyzed using an automated script (Figure S11 and Scripts 1 and 2 in the Supplemental Information) and endosomal pH calculated against a calibration curve. (A) Example false-color images from data in (B) of the pH in endolysosomal regions; color key bottom right of figure; enlarged images shown as Figure S6. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Total endosome volume within each pH range, calculated as the mean of at least two independent experiments of the integrated pH log ratio of 10 separate images. (C) Cells were incubated with OG514-Dex-Cy5 for 1 h, washed, imaged, then reimaged at 2, 4, 8, and 24 h post-addition. Ratiometric analysis of the probe was conducted as in (B). Error bars represent the SEM. p values calculated using two-way ANOVA; see Statistics in the Supplemental Information.

To measure endolysosomal pH in the three cell lines, Fluo-Dex-Rhod was incubated with the cells for 20 and 60 min prior to uptake analysis by confocal microscopy. Data in Figures 3A and 3B show that the probe, in all three cell lines, was internalized to vesicular structures and was exposed to a range of pHs (7.4–5.6) after just 20 min incubation. At this time point, HCT116 and H358 cells show broad pH profiles, while ∼75% of the probe in the low-transfecting CT26.WT cells was in an environment of pH 5.0 or lower. Interestingly, a further 40 min of endocytic traffic was required by HCT116 cells to deliver the probe to this environment. However, H358 cells showed a broader pH profile, with 60% of the dextran still remaining in a pH > 5.0 environment after this longer incubation period. In summary, these results highlight that this dextran conjugate, in the three cell lines, experienced unique pH environments as it was delivered along the endolysosomal pathway.

The lack of sensitivity of Fluo-Dex-Rhod below pH 5.0 is demonstrated in Figure 3B where the gray columns, representing a large volume of internalized dextran, denote pH that can only be categorized as less than pH 5. To address this significant problem, we designed and manufactured a new pH probe incorporating Oregon green 514 (OG514) as the pH-sensitive fluorophore and the spectrally separable Cy5 as the pH-insensitive variant. OG514 is insensitive to changes higher than pH ∼5.5 before losing fluorescence at pH ∼3.5;26 this makes it a more suitable probe than fluorescein for measuring pH in the late endosomal-lysosomal system.

Attempts to calibrate the absolute intracellular pH sensed by the new probe using the same live-cell-imaging equilibration buffers and method at significantly lower pH (5.5–3.5) as described for Fluo-Dex-Rhod were unsuccessful, due to loss of cell viability and/or endolysosomal integrity when generating the calibration curve (data not shown). In live cells, we therefore examined ratiometric differences of OG514-Dex-Cy5 after a 1 h pulse followed by a 1- to 23-h chase. This probe showed that CT26.WT cells showed negligible and non-significant reduction in pH during the 23-h chase period (p = 0.201, 1 and 24 h), while HCT116 and H358 cells showed a significant pH decrease between these two time points (both p < 0.001) to a final pH value significantly lower than that for CT26.WT cells (p < 0.001) and HCT116 (p = 0.002) cells.

Overall, the data show that in H358 cells, while there is low initial exposure of dextran to pH < 5.0, a subsequent chase period results in accumulation of dextran in increasingly acidic compartments. This was not observed in the other two cell lines, as within 60 min a very large fraction of dextran is already located in a pH < 5.0 environment (Figure 3B) and thus there is little subsequent change in the ratio of OG514-Dex-Cy5 (Figure 3C). The low-transfecting CT26.WT cells were however unable to further acidify their endolysosomal system beyond what is seen after just 20 min.

LNP Uptake and Transfection

The observed endocytic profile of dextran and other endocytic probes in the three cells lines was compared with cells incubated with LNPs encapsulating Cy5-labeled EGFP-mRNA. These experiments also allowed for analysis of endolysosomal escape and subsequent translation, manifest as EGFP expression.

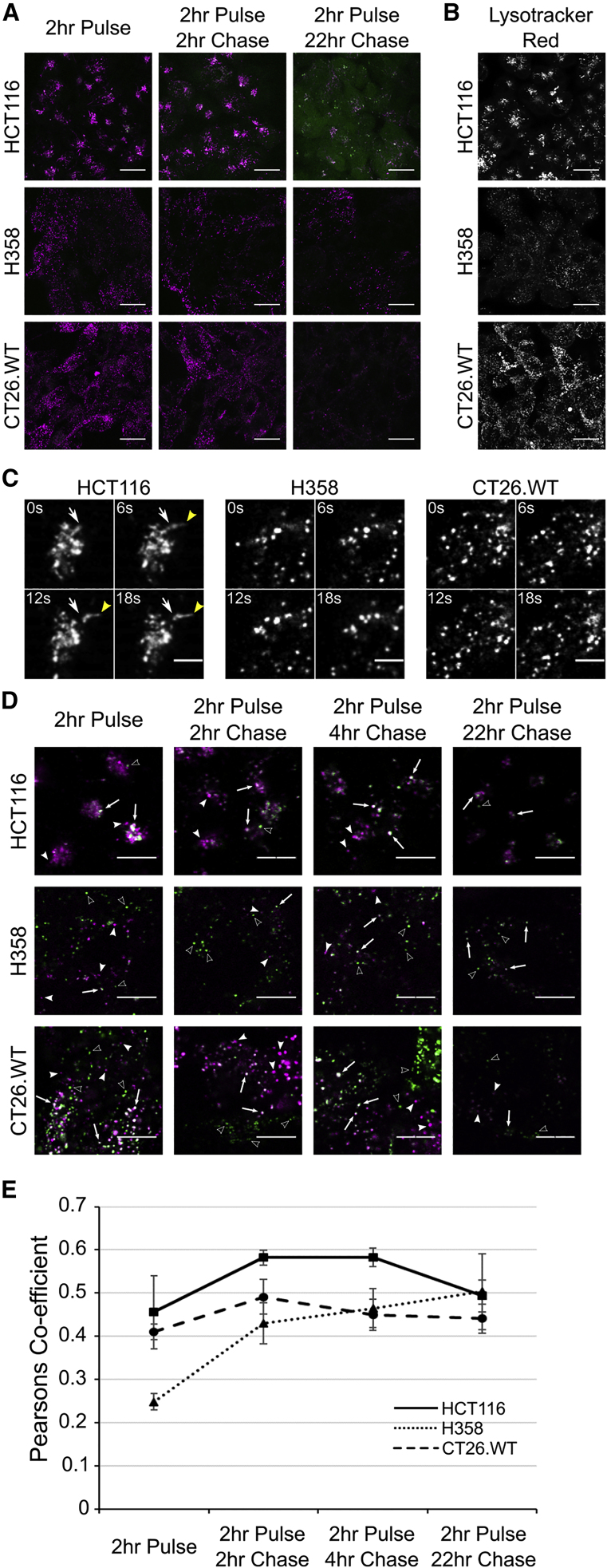

Analogous to dextran and LAMPII, Cy5-mRNA fluorescence was localized to the tight juxtanuclear region of HCT116 cells, and at only 4 h (2 h pulse, 2 h chase) EGFP fluorescence was observed (Figure 4A); this increased significantly during the course of the experiment to 24 h (2 h pulse, 22 h chase). As suggested in Figure 1, consistent levels of EGFP expression were observed across the cell population. In the other two models, vesicular LNP distribution again mirrored dextran/LAMPII localization, but there was no evidence of EGFP expression after 4 h. At 24 h, there was low EGFP expression in the H358 cell line; however, none could be detected in CT26.WT cells. Staining the cells with lysotracker red (Figure 4B) for 2 h confirmed that the differentially localized structures containing dextran and LNPs were acidic in nature. As cell uptake of Cy5-mRNA was seen to be similar between HCT116 and H358 cell lines (Figure 5G), our earlier identification of delayed trafficking in H358 cells to acidic organelles (as seen in Figure 3) is very likely to be responsible for reduced expression. Time-lapse imaging of cells incubated for 2 h with Cy5-mRNA/LNP (Figure 4C; Videos S1, S2, and S3) showed motile vesicles in all three cell types but identified, exclusively in HCT116 cells, highly motile tubular structures entering and exiting from the juxtanuclear cluster.

Figure 4.

Uptake of Cy5-mRNA/LNP and EGFP Expression and Distribution of Lysosomes

(A) Cells were incubated with LNP containing Cy5-mRNA (magenta) encoding EGFP (green) and incubated for 2 h before washing and imaging after 2 and 22 h. Images represent maximum projections, and intensities can be compared between time points but not between cell lines; see Figure 5 for comparative intensity measurements. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Cells were incubated with 50 nM lysotracker red (in the absence of LNPs) for 2 h before washing; images represent maximum projections. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) Stills from Videos S1, S2, and S3 showing differences in vesicular formation and movement (white arrow shows initial starting position; yellow arrowhead indicates movement). Cells were incubated with Cy5-mRNA/LNP. Scale bar, 5 μm (D and E) for 2 h followed by a chase period of 0, 2, 4, and 22 h. (D) Arrows indicate colocalization of the two probes (white/gray), solid arrowheads indicate non-colocalized Cy5-mRNA/LNP (magenta), and hollow arrowheads indicate lysosomes containing only the pulse-chased Dex-546 (green). Scale bars represent 10 μm. Intensities are comparable between time points but cannot be compared between cell lines. (E) Colocalization of Cy5-mRNA/LNP with dextran containing lysosomes (n = 3 separate experiments, error bars represent SEM). Enlarged images are shown in Figure S6; zoomed-out images are available in Figure S8. p values calculated using two-way ANOVA; see Statistics in the Supplemental Information.

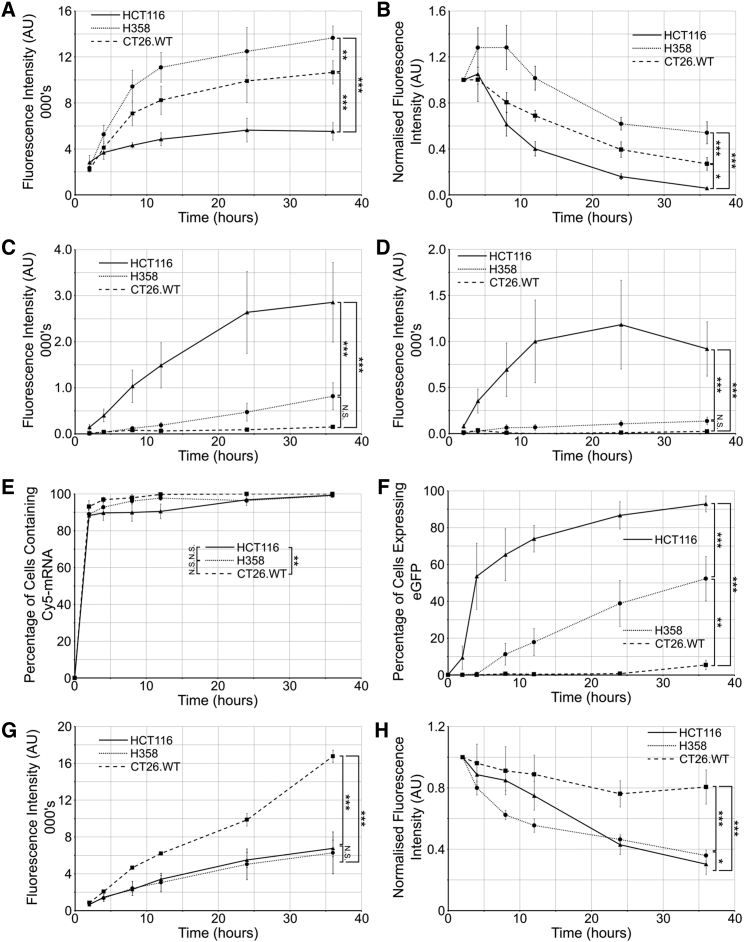

Figure 5.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Endocytic Uptake and Transfection

Cells were incubated with the Cy5-mRNA/LNP for either (A and C) continuous incubation of 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 36 h or as (B and D) pulse-chase with cells incubated for 2 h followed by a chase period for the remaining time. (A and B) Analysis of Cy5-mRNA uptake. (C and D) Analysis of EGFP expression. Following continuous incubation, cells are categorized as having (E) internalized the LNP or (F) having been transfected following continuous incubation. Cells were incubated with a continuous pulse of Dextran-Alexa 488 (G) or with a pulse-chase of Dex-488 (H). In all cases, values represent the mean from three independent experiments of the median fluorescence of each population; error bars represent SEM. Fluorescence measurement settings were maintained between all experiments. See Figure S9 for raw data showing recycling of (Figure S9A) Cy5-mRNA and (Figure S9B) Dextran-Alexa 488. Representative histograms are shown in Figure S10. p values calculated using two-way ANOVA; see Statistics in the Supplemental Information for further information. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.01.

As we had compared endocytic analysis of dextran and LNPs separately, we investigated whether the LNP traffics to the same terminal lysosomal compartments that had been labeled with fluorescent dextran already internalized via an earlier pulse-chase period.27 Cy5-mRNA/LNP were pulsed with the cells for 2 h and washed from the media, and fluorescence was then visualized after 2-, 4-, 6-, and 24-h chase periods (Figure 4D). Cy5-mRNA and lysosomal dextran-546 colocalization was then quantified (Figure 4E). Over the course of the experiment, significant differences were observed between all three cell lines with respect to Cy5-mRNA/LNP (p = 0.002) colocalization with lysosomes. HCT116 cells showed the most rapid colocalization of Cy5-mRNA with lysosomes, and H358 cells showed slow initial trafficking of Cy5-mRNA (and dextran) to lysosomes (Figures 4D and 4E; Figures S7 and S8). Interestingly, beyond the 2 h time point, there was no further increase in the colocalization of Cy5-mRNA with dextran in lysosomes, suggesting a block in traffic or a deviation from the route to these organelles. The reduced dextran and Cy5-mRNA fluorescence after 24 h, observed in all three models, is suggestive of recycling that we later analyzed and quantified (Figure 5).

To gain further information on trafficking and transfection and give a more complete endocytic profile, we performed flow cytometry analysis of cells incubated with Cy5-mRNA/LNP. After 8 h continuous LNP incubation, both CT26.WT (7,085 fluorescence units [FU] per cell) and H358 (9,427 FU/cell) had significantly higher cell-associated Cy5 fluorescence compared with HCT116 cells (4,500 FU/cell; Figure 5A). This is in contrast to equivalent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values at 2 h: HCT116, 3,360 FU/cell; versus CT26.WT, 2,190 FU/cell; and H358, 2,340 FU/cell. Surprisingly, this initial very rapid 2-h uptake in HCT116 cells represents the majority of mRNA that the cell internalizes, reaching ∼50% of the maximal uptake seen at 24 h. For both CT26.WT and H358, only ∼20% Cy5-mRNA is internalized after 2 h (when compared to much higher values at 36 h where saturation has yet to be reached). This agrees with the rate and extent of measurable transfection that reaches a plateau in HCT116 after 24 h, while there is a continuous increase in transfection throughout all 36 h in the H358 cells (Figure 5C). Throughout this long experimental time frame, despite internalizing a relatively large amount of the Cy5-mRNA/LNP, CT26.WT cells show no evidence of EGFP expression above background.

There was little similarity between the rate of uptake of Cy5-mRNA/LNP compared with dextran (Figure 5G) and for all cell lines, a more rapid initial uptake of LNPs was observed, indicative of receptor-mediated uptake.

It has been recently suggested that rates of recycling influence the ability of LNPs to deliver siRNA into the cytosol,28, 29 with recycling-deficient or -inhibited cells showing increased transfection ability. In our analysis, Cy5 fluorescence was still observed in the cells, to different extents, after 24 h (Figures 4A and 5A), prompting us to assess whether Cy5-mRNA/LNP recycling also influenced LNP-mediated delivery of mRNA. Cells were pulsed with the Cy5-mRNA/LNP for 2 h, and internalized cell fluorescence intensity was monitored over a 34-h chase period (Figure 5B). Surprisingly, and contrary to expectations, both the medium and low transfectors had relatively low recycling rates after 24 h: CT26.WT, 24%; H358, 38%. HCT116 cells, however, had expelled 86% of the internalized fluorescence after 24 h; 50% reduction in fluorescence was observed in < 12 h. These significantly different rates of recycling also lead to further differences in EGFP expression (Figure 5D). Between 24 and 36 h, there is a plateau and possibly a drop in EGFP expression in HCT116 cells, indicating that EGFP is being recycled or degraded faster than it is being translated from remaining mRNA. In H358 cells, however, there is a small but continual increase in EGFP expression, indicating that even 34 h after removal of the LNP, EGFP is being expressed.

In addition to determining the amount of transfection (as determined by FUs), we also looked at the percentage of “transfected” cells via flow cytometry. These were identified as having fluorescence above background, where background was defined as the fluorescence intensity of the 99.9th percentile of blank cells. Confirming data in Figure 5F, EGFP was detected in >50% HCT116 cells after 4 h. H358 cells, to a much lesser extent, were also transfected, taking 36 h to transfect more than 50% of cells; only 5% of CT26.WT cells gave higher than background EGFP fluorescence at this time point.

Discussion

Many unknown underlying intracellular differences affecting the in vitro and in vivo transfection capacity of any nucleic acid delivery system remain to be elucidated, and endocytic profiling identifies and highlights several factors likely to influence cytosolic delivery, positively or negatively. Correlation of LNP transfection capacity between in vitro and in vivo was shown using mouse tumor models of HCT116, H358, and CT26.WT, with the former portraying high transfection levels and the latter negligible levels. Initial profiling experiments revealed major differences in the organization of both the endolysosomal system and the Golgi apparatus that regulate membrane trafficking between the plasma membrane and endosomes. The spatial organization of late endosomes and lysosomes immediately suggested that the scattered phenotype identified in H358 and CT26.WT cells may be prognostic of low transfection. We postulated that this may be governed by differences in microtubule arrangements, and recent studies suggest scattered lysosomes are associated with higher pH and lower proteolytic activity compared to their juxtanuclear counterparts.30 We were surprised to discover that the endolysosomal phenotypes do not appear to be due to microtubule organization, and the reason for such pronounced differences in late endosomal and/or lysosomal profiles remains to be determined.

With pH being implicated in endosomal organization and being the vesicular release mechanism of the LNP, it was important to analyze this parameter as part of our endocytic profiling. Very few studies, however, have attempted to correlate endosomal escape of delivered nucleic acid delivery systems with endolysosomal pH—none for LNP-mediated mRNA delivery. This is surprising, as so many delivery strategies have an absolute reliance on effective acidification for catalyzing endosomal escape. A major barrier in accurate endosomal pH measurement is the availability of probes for analyzing the whole endolysosomal pH range from 7.4 to 4.0. Fluorescein proved deficient in this manner, requiring us to manufacture a new probe to track the pH across the whole endosomal system to lysosomes. Fluorescent dextran is commonly used as a fluorophore carrier for microscopy and flow cytometry pH analysis.30, 31 Several other single or combinations of ratiometric pH probes have been described, including those entrapped in nanoparticles or on the surface of cell-penetrating nanoneedles.32, 33 A triple-labeled system was developed combining, on the same polyacrylamide nanoparticle, fluorescein and OG514 versus rhodamine, allowing for analysis of the full endocytic pH range.34 Our double-probe approach is a useful alternative to this system, and it will be interesting to explore its further application in other pH-based endocytosis studies.

Using a commercial dextran pH probe, we initially highlighted the large differences in the pH of the early endocytic structures among the three cell lines. The resulting pH profiles proved difficult to correlate with LNP transfection capacity; however, using our newly developed probe, we were able to establish that the low-transfecting CT26.WT cells had the highest terminal pH and later identified a defect in the trafficking of the LNP to lysosomes. We postulate that both these factors have a negative impact on transfection due to the LNPs’ limited trafficking to the environment that favors endosomal escape. In stark contrast, HCT116 cells were notable for showing a high initial rate of endocytosis through the full endolysosomal pH profile to lysosomes. What does not reach this organelle is rapidly recycled, and during both or either of these processes, it is thought the mRNA rapidly escapes to the cytosol, manifest as protein expression at very early time points. The medium transfector H358 cells sit in between the HCT116-CT26.WT extremes, having relatively slow rate of pH change albeit with a relatively low terminal pH. This supports the flow cytometry analysis of EGFP expression, where H358 cells show evidence of a continued slow increase in transfection compared to HCT116 cells, where transfection appears to rapidly saturate.

Optimization of the ionizable lipid pKa in DLin-MC3-DMA LNPs delivering mRNA was also recently demonstrated;35 however, the success of any such delivery strategy remains reliant on understanding the pH environment of a specific cell model. This knowledge is important for valid assessment of cargo delivery performance to the cytosol. Data published during the writing of this manuscript suggest endosome size and leakiness influences the release of polyplex-plasmid DNA from endosomes via the proton sponge effect, an effect mechanistically quite different from the pH-induced lipid conformational changes and release mechanism of LNPs.36

Differences in the dynamics of trafficking have been shown in a recent study that also identified CT26.WT mouse line as a low protein expressor compared with breast cancer SK-BR3 cells following transfection with DNA plasmid polyplexes composed of either polyethyleneimine (PEI) or polyamidoamine gold.37 A high initial polyplex uptake rate was identified as a determining factor for transfection efficiency, similar to what we observe here with an LNP-delivering mRNA. The data also highlights, without comment, juxtanuclear polyplexes in SKBR3 cells but scattered localization in CT26.WT cells. This suggests a commonality with respect to uptake and endolysosomal distribution of two very different delivery systems (cargo and vector) acting at different locations. We show using time-lapse imaging that this juxtanuclear region in HCT116 cells is a highly dynamic cluster of membrane traffic, forming tubular structures that organized Cy5-mRNA delivery to other compartments such as recycling endosomes. Support for this is provided by studies showing recycling endosomes as tubular networks, referred to as the endosomal recycling compartment, that is often prominent in a juxtanuclear region of the cell.38, 39 As tubulation is a notable feature of recycling endosomes, further studies may reveal that their biological environment favors escape to the cytosol. A previous study using a cationic LNP (via C12-200)-containing siRNA suggests that effective recycling leads to poor protein silencing,28 although this LNP is known to internalize independently of ApoE. This is supported by a study in cells incubated for 24 h with siRNA-loaded ionizable (MC3) nanoparticles and agents affecting recycling via inhibition of the NPC1 protein.29 We identify here, however, using flow cytometry and microscopy, that internalized Cy5-mRNA escapes from cells much more rapidly in HCT116 cells compared to the low-transfecting models. This agrees with localization of the LNP in tubules that we postulate to be recycling compartments. We also show trafficking of LNPs to juxtanuclear compartments is rapid in HCT116 cells and that a fraction of mRNA sufficient to express GFP protein has escaped into the cytosol before the remainder is recycled or degraded. The pKa of the DLin-MC3-DMA ionizable lipid is 6.4; this compares favorably with recycling endosomes’ pH40, 41 that are less acidic than early or sorting endosomes. Overall, it is difficult to draw parallels between endosomal escape of siRNA and mRNA, as they have quite different molecular weights and hydrodynamic volumes, and the mechanisms or machinery needed to influence protein expression are different, with a longer time period required to functionally measure siRNA delivery efficiency. Electron microscopy studies from the Zerial group42 analyzing DLin-MC3-DMA siRNA delivery do, however, provide compelling evidence that cargo escape is occurring at early endosomal level, noting that recycling endosomes contain internalized material in less than 15 min after exposure to cells.40 This is, however, in contrast to later studies showing Rab7-dependent trafficking to late endosomes and/or lysosomes was important for functional mRNA delivery utilizing ionizable LNPs containing leukotriene inhibitor MK-571.43

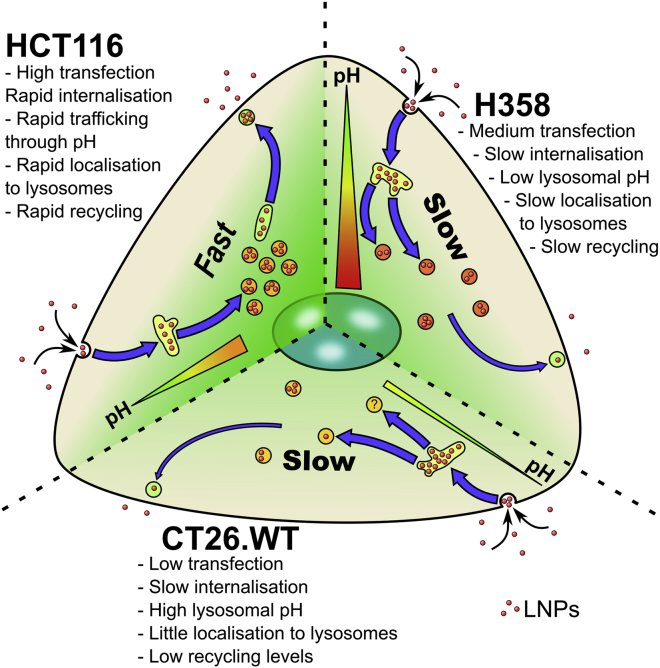

From the endocytic profiling undertaken here, we have identified important features that influence the effective delivery of mRNA by LNPs and the resultant protein expression (Figure 6). Rapid transport through the endosomal pathway to lysosomes or out of the cell via recycling and/or exocytosis positively influences LNP-mediated mRNA cytosolic delivery. This occurred very rapidly in HCT116 cells, suggesting that a much narrower-than-expected escape window is optimal for maximal transfection. H358 did express EGFP but at a low and via a prolonged mechanism. The two low-transfecting cell lines were noted for having slower endocytic traffic, with CT26.WT additionally having defects in endolysosomal acidification.

Figure 6.

Summary of Uptake Characteristics in the Three Models

HCT116, H358, and CT26.WT internalize Cy5-mRNA/LNP and traffic to dextran positive lysosomes at differing rates. These terminal lysosomes have differing relative pH levels in different cell lines from high (green) to low (red) pH. Recycling rates also differ between the cell lines, with HCT116 rapidly expelling Cy5, to lower Cy5 recycling rates in H358 and CT26.WT cells.

Overall, our data point to the fact that it is highly unlikely that one single cellular factor or process determines the efficiency capacity of this LNP or other NP delivery systems that rely on endocytosis for success. This new knowledge will now, however, influence our subsequent use of these models for drug delivery analysis in vitro and in vivo. High-content endocytic profiling of in vitro models, as shown here, could form an important process in the design phase of intracellular delivery systems and be carried out much earlier in the drug-discovery phase. This is especially pertinent for those systems such as LNPs that depend on responding to biological stimuli such as endosomal pH for their mechanism of delivery. This study also illustrates that systems relying on pH triggers for delivery cannot be used indiscriminately across disease areas and/or cell types and may not be appropriate in settings where disease pathology involves changes in endolysosomal organization and intracellular pH. Thus, more investment and considerations toward understanding the cell model representative of the intended disease should be considered, rather than solely focusing on the characteristics of the delivery systems. This will hopefully inform the design of more efficient, bespoke delivery systems that will be able to fully exploit the potential of nucleic-acid-based therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The ionizable cationic lipid O-(Z,Z,Z,Z-heptatriaconta-6,9,26,29-tetraem-19-yl)-4-(N,N-dimethylamino) butanoate (DLin-MC3-DMA) was synthesized at Moderna. 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy-(polyethyleneglycol)-2000] (DMPE-PEG2000) from NOF Corporation and cholesterol (Chol) from Sigma-Aldrich. EGFP mRNA (996 nucleotides) ARCA capped modified with 5-methylcytidine and pseudouridine used for in vitro work was purchased from TriLink Biotechnologies, while EGFP and luciferase mRNAs used in the cell screen and in vivo analysis were provided by Moderna.35 Citrate buffer was purchased from Teknova, and HyClone RNase free water was obtained from GE Healthcare Cell Culture. Amino dextran (10 kDa), 5/6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester, 5/6-carboxyfluorescein NHS ester, OG514 NHS ester, and Thermo Scientific Pierce 6-kDa MWCO polyacrylamide desalting columns (10 mL) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Sulfo-Cy5 NHS ester was purchased from Lumiprobe Life Science Solutions. Succinic anhydride, citric acid, sodium phosphate dibasic dihydrate, sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate, and anhydrous DMSO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All reagents and solvents were used as supplied.

LNP Preparation and Characterization

LNPs were prepared using the microfluidic setup described in detail elsewhere.44 In brief, stocks of lipids were dissolved in ethanol and mixed in the appropriate weight ratios (20:1 or 10:1 lipid:mRNA) to obtain a lipid concentration of 12.5 mM (1.85 mg/mL). The aqueous and ethanol solutions were mixed in a 3:1 volume ratio using a microfluidic apparatus NanoAssemblr, from Precision NanoSystems, at a mixing rate of 12 mL/min. LNPs were dialyzed overnight against 400× sample volume using Slide-A-Lyzer G2 dialysis cassettes from Thermo Scientific with a molecular weight cutoff of 10 kDa.

Size of LNPs was confirmed by dynamic light scattering measurements using a Zetasizer Nano ZS from Malvern Instruments; the concentration and encapsulation of mRNA were determined using the RiboGreen assay. The encapsulation efficiency and physical characteristics of the batches used can be found in Table S1.

Cell Culture

Human colon epithelial (HCT116), human lung epithelial (H358), and mouse colon fibroblast (CT26.WT) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in medium (RPMI, Gibco, Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and one-part GlutaMAX (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK). This is referred to hereafter as complete medium. Cells were maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator for no more than 10 passages post-thawing and regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination (LookOut, Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK). In addition, cell identities were confirmed by species-specific short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling against a minimum of nine published markers (STR profiling was outsourced to IDEXX BioResearch). For all experiments, cells were seeded at the following densities for 48 h before analysis unless otherwise stated: HCT116, 42,000 viable cells/cm2; H358, 63,000 viable cells/cm2; CT26.WT, 63,000 viable cells/cm2.

LNP-Mediated Delivery of EGFP mRNA in a Panel of Cancer Cell Lines

All cell types were cultured in the same conditions using complete medium. Cells were seeded into black-walled, clear-bottom 384-well plates (Corning, #3712) at 3,000 cells/well, 60%–80% confluency. Cells were seeded into 75 μL of complete medium and incubated overnight at 37°C/5% CO2. At time of seeding, cell viability was > 90% as determined by trypan blue exclusion. The following day, LNPs formulated with 30 ng mRNA at a concentration of 0.4 ng/μL (30 ng/0.06 cm2) were added in complete medium and incubated with the cells for periods between 0 and 48 h. Immediately following addition of LNP, the cells were imaged live using an Incucyte ZOOM (Essen Bioscience) where kinetic EGFP and phase contrast images were captured at 10× magnification every 2 h for a total of 48 h. Images were analyzed using the integrated Incucyte ZOOM analysis software. Cells were identified and segmented for analysis via fine tuning of the software parameter conditions on the bright-phase images. A fixed threshold level was adjusted per cell type to classify EGFP-expressing cells over background levels. The segmentation masks were then used to calculate mean cell confluence and EGFP integrated intensity measurements as an estimate of total cellular EGFP expression levels.

Duplicate plates were also fixed (4% paraformaldehyde [PFA] for 20 min, followed by 3× PBS wash) after either 24 h or 48 h of LNP exposure. These plates were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, 1:5,000) for 20 min followed by 3× PBS wash. Fluorescent images were captured on an ImageXpress Micro (Molecular Devices) using a 10× objective.

In Vivo Comparison of LNP Potency in Different Tumor Models

HCT116 for implantation were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% glutamine, while both H358 and CT26.WT were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% glutamine, at 37°C and 7.5% CO2. Cells were implanted by subcutaneous injection of 1 × 107 HCT116 cells/mouse, 3 × 106 H358 cells/mouse with 50% Matrigel, or 5 × 105 CT26.WT cells/mouse into the left flank of female nude (HCT116 and H358, 18 g+) or BALB/c mice (CT26.WT, 16 g+, all Envigo UK). When the tumors had reached ∼200–300 mm3 (11 days post-implantation using HCT116, 17 days for H358, and 10 days for CT26) mice were randomized by size into treatment groups (n = 4–5/group).

Mice were administered a single intra-tumoral injection of 30 μL of PBS or MC3 LNP loaded with luciferase mRNA (1.25 μg or 12.5 μg/mouse) using a 29G insulin syringe (Henry Schein). At 6 h post-dose, mice were bled under terminal anesthesia, and tumors were excised whole, snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Frozen tumors were thawed on ice and weighed. 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison WI, USA) was added to each tumor to obtain a final concentration of 100 mg of tissue per mL. Tumors were homogenized using a Polytron 1200E homogenizer with PT-DA 07/2 EC-E107 probe (Kinematica, Luzern, Switzerland) for 2 min followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 300 × g at 4°C. Supernatants were stored at −80°C until required.

Tumor supernatants were thawed on ice. Control tumors were used as diluent to generate a standard curve and controls with QuantiLum recombinant luciferase (Promega). Aliquots (20 μL) of standards, controls, and samples were added to a 96 Maxisorp black microwell plate (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark) prior to addition of 100 μL of luciferase assay reagent (Promega) to each well as directed by manufacturer’s protocol. Luminescence was detected using EnVision 2104 multilabel reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham MA, USA) following 2 min incubation. The standard curve was generated using 4PL non-linear regression and used to calculate luciferase concentrations in samples.

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with UK Home Office legislation, the Animal Scientific Procedures Act 1986, and the AstraZeneca Global Bioethics policy. All experimental work is outlined in project license 70/8894, which has gone through the AstraZeneca Ethical Review Process.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells were seeded at densities described above onto sterile coverslips and allowed to adhere for 48 h. They were then either fixed with 3% PFA in PBS for 20 min or −20°C methanol for 3 min before washing three times with PBS. PFA-fixed cells were permeabilized and quenched in 0.1% Triton X-100/50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 10 min and washed three times in PBS. Both PFA- and methanol-fixed cells were blocked with blocking solution (2% BSA, 2% FBS in 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS) for 30 min before applying the primary antibody (see Table S2). PFA-fixed cells were washed three times in 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, while methanol-fixed cells were washed three times in PBS for 5 min. Secondary antibodies (all from Life Technologies) were diluted 1:1,000 in blocking buffer containing 1 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 and applied to the cells for 1 h. Coverslips were washed a further three times in PBS, dipped in distilled water, and immediately mounted onto microscope slides using Dako fluorescence mounting medium.

Samples were imaged on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope using the 405-nm, 488-nm, 543-nm, and 633-nm lasers, 63× 1.4 nucleic acid (NA) oil immersion objective. Images obtained were analyzed using ImageJ45 and are presented as single-section images or maximum projection images through the z axis. Presented images are representations from at least two independent experiments.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were seeded into 24-well plates (Corning, Fisher Scientific) at the previously outlined density, allowed to adhere prior to incubation for different experiments with 380 ng LNP (200 ng/cm2), 12.5 μg dextran-Alexa 488 (Dex-488; Fisher Scientific) (50 μg/mL), or 1 μg DiI-LDL (4 μg/mL), all in 250 μL complete medium.

For LNP uptake experiments, cells were either incubated with the LNP or Dex-488 continuously for 2 h (pulse) followed by washing three times in complete medium and then further incubated in complete medium for the remainder of the experiment (chase).

For all experiments, cells were trypsinized using 100 μL 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Fisher Scientific) for 5 min at 37°C, washed with ice-cold PBS containing 5% BSA by centrifuging at 400 × g at 4°C for 3 min, then washed in ice-cold PBS alone, and finally resuspended in 500 μL ice-cold PBS. Samples were analyzed on a FACSVerse (BD) using the 488-nm and 633-nm lasers, 527/32 (for EGFP and Alexa 488) and 660/10 (for Cy5 and Alexa 647) filters. Cells were double gated for single cells (forward scatter-area/side scatter-area [FSC-A/SSC-A] and forward scatter-height/forward scatter-width [FSC-H/FSC-W]) with no further gating. The median was used to determine MFI values within each experiment. Values plotted represent the mean of the medians from at least three independent experiments.

Live Cell Microscopy: Lysosomal Delivery of LNPs and Dextran

Cells were seeded onto tissue-culture-treated 35-mm imaging dishes (Ibidi, Thistle Scientific, Glasgow, UK) at the previously outlined density and allowed to adhere. Twelve hours before imaging, cells were incubated with 50 μg dextran-Alexa 546 (Dex-546; Fisher Scientific) in 500 μL complete medium (100 μg/mL) for 2 h (pulse) before washing three times in complete medium and incubating overnight in complete medium under tissue culture conditions (chase). On the day of the experiment, cells were pulsed with 1.9 μg LNP (200 ng/cm2) or 100 μg dextran-Alexa 647 (Dex-647; Fisher Scientific) in 1 mL complete medium and incubated for 2 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were then washed in complete medium and immediately imaged on the SP5 confocal microscope (2 h time point) at 37°C 5% CO2. Samples were then returned to the tissue culture incubator and reimaged at 4, 6, and 24 h post-addition.

Confocal imaging was performed sequentially using 488-nm and 633-nm lasers followed by 543-nm laser, using a 63× oil immersion CSII objective at 1,000 Hz with a line average of 3 (bidirectional scanning), with the pinhole set to 1 airy unit. Images were acquired with a raster size of 1,024 × 1,024 and a zoom of 2.5 to give an apparent voxel size of 130 × 130 × 500 nm (XYZ). The diffraction limit at 488 nm of our microscope with the objective 131 × 131 × 700 nm (XYZ); these settings were chosen as a compromise between imaging speed, resolution, and number of cells per image.

Images were analyzed using the JACoP46 plugin for ImageJ using Pearson’s coefficient to determine the colocalization of LNP or Dex-647 with lysosomal localized Dex-546.27 Thresholds for images were automatically determined using the Otsu thresholding algorithm, and the colocalization value returned was used to calculate the mean colocalization of 10 images (representing > 100 cells analyzed per sample). A mean of this result from three independent experiments was then subsequently obtained.

Endolysosomal pH Analysis: Uptake and Calibration of Fluo-Dex-Rhod (“High” pH Probe)

Cells were seeded onto tissue culture (TC)-treated 35-mm imaging dishes at the previously outlined density and allowed to adhere. To localize fluorescein-dextran-rhodamine (Fluo-Dex-Rhod) to the lysosomes, 100 μg/mL of the probe was pulse-chased overnight as previously described. To enrich the probe in earlier endocytic compartments, the same probe was pulsed for 20 min before washing and imaging, while a 1 h pulse was employed to label the entire fluid phase pathway from plasma membrane to lysosomes.47

To generate Fluo-Dex-Rhod pH calibration curves, cells were incubated with 100 μg/mL probe for 1 h and washed three times in PBS. Subsequently, cells were incubated with ionophores 20 μM nigericin (stock solution 10 mM in DMSO, stored at 4°C) and 20 μM monensin (both Sigma-Aldrich, stock solution 50 mM in ethanol, stored at −20°C) for 5 min in the presence of the relevant pH buffer (see Preparation of pH Buffers in the Supplemental Materials and Methods and Table S2). The cells were then imaged at the requisite pH in the presence of both ionophores. A minimum of 10 single-section images were obtained per condition on the confocal microscope (see Live Cell Microscopy: Lysosomal Delivery of LNPs and Dextran above) sequentially scanning alternately on either 488-nm or 543-nm lasers to reduce bleed-through. Images were analyzed using an automated script (see Script 1 for Measuring Fluorescence Ratio between Two Fluorophores in the Supplemental Information) with the ratio of the log fluorescein intensity and log rhodamine intensity of each region of interest (ROI) used for calculating and quantifying pH.

Endolysosomal pH Analysis: Uptake of OG514-Dextran-Cy5 (“Low” pH Probe)

To synthesize the probe, amino dextran (5 mg, 0.5 μmol) was dissolved in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate solution (0.5 mL) in a 5-mL reaction vial fitted with a magnetic stirrer bar. Following dissolution, the solution was chilled in an ice bath. The solution was transferred to a vial containing OG514 carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester (0.46 mg, 0.75 μmol) to dissolve the dye. The new solution was then quickly transferred to another vial containing sulfo-Cy5 NHS ester (0.57 mg, 0.72 μmol) and was stirred in an ice bath for 2 h. The solution and stirrer bar were then transferred to a vial containing succinic anhydride (1.5 mg, 15 μmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred over ice for 1 h then overnight at room temperature. The solution was directly loaded onto a size exclusion desalting column and eluted with Millipore water. Polymer fractions were collated into a 5-mL Eppendorf tube and frozen in dry ice before freeze-drying to obtain the title product as a dark blue solid of 5.2 mg, 91% yield. Absence of unreactive dyes was tested by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) running in a 70:25:5 ratio of chloroform:methanol:acetic acid.

To determine the differences in intracellular acidity, cells were seeded onto tissue culture-treated 35-mm imaging dishes at the previously outlined density and allowed to adhere. OG514-Dextran-Cy5 (OG514-Dex-Cy5) was enriched in different endocytic organelles using the same method as for Fluo-Dex-Rhod, analyzed by confocal microscopy (see Live Cell Microscopy: Lysosomal Delivery of LNPs and Dextran above) and quantified as for Fluo-Dex-Rhod using the same script (Script 1 for Measuring Fluorescence Ratio between Two Fluorophores in the Supplemental Information).

Statistics

All graphs represent the mean of three independent experiments with error bars representing the SEM. Probability is calculated using either a two-tailed t test for when only two factors are compared within an experiment or a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis for comparing three or more factors within an experiment. ANOVA tables detailing F values and degrees of freedom are displayed in the Statistics section of the Supplemental Information. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Author Contributions

In vitro research was undertaken by E.J.S. and S.E.P. with support from A.S. and R.M.E. In vivo research was undertaken by A.S.D., M.B., and S.M.B. E.J.S., A.T.J., S.E.P., A.S.D., S.P., and M.B.A. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript before submission.

Conflicts of Interest

M.B.A., S.P., S.E.P., A.S.D., R.M.E., A.S., M.B., and S.M.B. are employees of AstraZeneca.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jen Wymant (Cardiff University) and Alex Kapustin (AstraZeneca Cambridge) for critically reading this manuscript, Dr. Jennifer Hare (AstraZeneca Cambridge) for performing the in vivo studies, and Maelle Mairesse for her contribution to the in vivo analysis. The work was funded by AstraZeneca with experiments performed at Cardiff University and AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.07.018.

Contributor Information

Marianne B. Ashford, Email: marianne.ashford@astrazeneca.com.

Arwyn T. Jones, Email: jonesat@cardiff.ac.uk.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Sahin U., Karikó K., Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics—developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:759–780. doi: 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kormann M.S., Hasenpusch G., Aneja M.K., Nica G., Flemmer A.W., Herber-Jonat S., Huppmann M., Mays L.E., Illenyi M., Schams A. Expression of therapeutic proteins after delivery of chemically modified mRNA in mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:154–157. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zangi L., Lui K.O., von Gise A., Ma Q., Ebina W., Ptaszek L.M., Später D., Xu H., Tabebordbar M., Gorbatov R. Modified mRNA directs the fate of heart progenitor cells and induces vascular regeneration after myocardial infarction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:898–907. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youn H., Chung J.K. Modified mRNA as an alternative to plasmid DNA (pDNA) for transcript replacement and vaccination therapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2015;15:1337–1348. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1057563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svitkin Y.V., Cheng Y.M., Chakraborty T., Presnyak V., John M., Sonenberg N. N1-methyl-pseudouridine in mRNA enhances translation through eIF2α-dependent and independent mechanisms by increasing ribosome density. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:6023–6036. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kay M.A. State-of-the-art gene-based therapies: the road ahead. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:316–328. doi: 10.1038/nrg2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin H., Kanasty R.L., Eltoukhy A.A., Vegas A.J., Dorkin J.R., Anderson D.G. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:541–555. doi: 10.1038/nrg3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semple S.C., Akinc A., Chen J., Sandhu A.P., Mui B.L., Cho C.K., Sah D.W., Stebbing D., Crosley E.J., Yaworski E. Rational design of cationic lipids for siRNA delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:172–176. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Draghici B., Ilies M.A. Synthetic nucleic acid delivery systems: present and perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:4091–4130. doi: 10.1021/jm500330k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Junquera E., Aicart E. Recent progress in gene therapy to deliver nucleic acids with multivalent cationic vectors. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;233:161–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zatsepin T.S., Kotelevtsev Y.V., Koteliansky V. Lipid nanoparticles for targeted siRNA delivery - going from bench to bedside. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2016;11:3077–3086. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S106625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullis P.R., Hope M.J. Lipid Nanoparticle Systems for Enabling Gene Therapies. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1467–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Digiacomo L., Cardarelli F., Pozzi D., Palchetti S., Digman M.A., Gratton E., Capriotti A.L., Mahmoudi M., Caracciolo G. An apolipoprotein-enriched biomolecular corona switches the cellular uptake mechanism and trafficking pathway of lipid nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2017;9:17254–17262. doi: 10.1039/c7nr06437c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanez Arteta M., Kjellman T., Bartesaghi S., Wallin S., Wu X., Kvist A.J., Dabkowska A., Székely N., Radulescu A., Bergenholtz J., Lindfors L. Successful reprogramming of cellular protein production through mRNA delivered by functionalized lipid nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E3351–E3360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720542115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayaraman M., Ansell S.M., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K., Chen J., Du X., Butler D., Eltepu L., Matsuda S., Narayanannair J.K. Maximizing the potency of siRNA lipid nanoparticles for hepatic gene silencing in vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:8529–8533. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nabhan J.F., Wood K.M., Rao V.P., Morin J., Bhamidipaty S., LaBranche T.P., Gooch R.L., Bozal F., Bulawa C.E., Guild B.C. Intrathecal delivery of frataxin mRNA encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles to dorsal root ganglia as a potential therapeutic for Friedreich’s ataxia. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20019. doi: 10.1038/srep20019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamano S., Dai J., Moursi A.M. Comparison of transfection efficiency of nonviral gene transfer reagents. Mol. Biotechnol. 2010;46:287–300. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tam Y.Y., Chen S., Cullis P.R. Advances in Lipid Nanoparticles for siRNA Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2013;5:498–507. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics5030498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghandi M., Huang F.W., Jané-Valbuena J., Kryukov G.V., Lo C.C., McDonald E.R., 3rd, Barretina J., Gelfand E.T., Bielski C.M., Li H. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature. 2019;569:503–508. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S., Tam Y.Y., Lin P.J., Leung A.K., Tam Y.K., Cullis P.R. Development of lipid nanoparticle formulations of siRNA for hepatocyte gene silencing following subcutaneous administration. J. Control. Release. 2014;196:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anitei M., Hoflack B. Bridging membrane and cytoskeleton dynamics in the secretory and endocytic pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;14:11–19. doi: 10.1038/ncb2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vonderheit A., Helenius A. Rab7 associates with early endosomes to mediate sorting and transport of Semliki forest virus to late endosomes. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaval B., Doxsey S.J. Pericentrin in cellular function and disease. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:181–190. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sizovs A., McLendon P.M., Srinivasachari S., Reineke T.M. Carbohydrate polymers for nonviral nucleic acid delivery. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010;296:131–190. doi: 10.1007/128_2010_68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphries W.H., 4th, Szymanski C.J., Payne C.K. Endo-lysosomal vesicles positive for Rab7 and LAMP1 are terminal vesicles for the transport of dextran. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026626. e26626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayward R., Saliba K.J., Kirk K. The pH of the digestive vacuole of Plasmodium falciparum is not associated with chloroquine resistance. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:1016–1025. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moody P.R., Sayers E.J., Magnusson J.P., Alexander C., Borri P., Watson P., Jones A.T. Receptor Crosslinking: A General Method to Trigger Internalization and Lysosomal Targeting of Therapeutic Receptor:Ligand Complexes. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:1888–1898. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahay G., Querbes W., Alabi C., Eltoukhy A., Sarkar S., Zurenko C., Karagiannis E., Love K., Chen D., Zoncu R. Efficiency of siRNA delivery by lipid nanoparticles is limited by endocytic recycling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:653–658. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H., Tam Y.Y., Chen S., Zaifman J., van der Meel R., Ciufolini M.A., Cullis P.R. The Niemann-Pick C1 Inhibitor NP3.47 Enhances Gene Silencing Potency of Lipid Nanoparticles Containing siRNA. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:2100–2108. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson D.E., Ostrowski P., Jaumouillé V., Grinstein S. The position of lysosomes within the cell determines their luminal pH. J. Cell Biol. 2016;212:677–692. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201507112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchetti A., Lelong E., Cosson P. A measure of endosomal pH by flow cytometry in Dictyostelium. BMC Res. Notes. 2009;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiappini C., Martinez J.O., De Rosa E., Almeida C.S., Tasciotti E., Stevens M.M. Biodegradable nanoneedles for localized delivery of nanoparticles in vivo: exploring the biointerface. ACS Nano. 2015;9:5500–5509. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desai A.S., Chauhan V.M., Johnston A.P., Esler T., Aylott J.W. Fluorescent nanosensors for intracellular measurements: synthesis, characterization, calibration, and measurement. Front. Physiol. 2014;4:401. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benjaminsen R.V., Sun H., Henriksen J.R., Christensen N.M., Almdal K., Andresen T.L. Evaluating nanoparticle sensor design for intracellular pH measurements. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5864–5873. doi: 10.1021/nn201643f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabnis S., Kumarasinghe E.S., Salerno T., Mihai C., Ketova T., Senn J.J., Lynn A., Bulychev A., McFadyen I., Chan J. A Novel Amino Lipid Series for mRNA Delivery: Improved Endosomal Escape and Sustained Pharmacology and Safety in Non-human Primates. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vermeulen L.M.P., Brans T., Samal S.K., Dubruel P., Demeester J., De Smedt S.C., Remaut K., Braeckmans K. Endosomal Size and Membrane Leakiness Influence Proton Sponge-Based Rupture of Endosomal Vesicles. ACS Nano. 2018;12:2332–2345. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Figueroa E., Bugga P., Asthana V., Chen A.L., Stephen Yan J., Evans E.R., Drezek R.A. A mechanistic investigation exploring the differential transfection efficiencies between the easy-to-transfect SK-BR3 and difficult-to-transfect CT26 cell lines. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2017;15:36. doi: 10.1186/s12951-017-0271-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant B.D., Donaldson J.G. Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:597–608. doi: 10.1038/nrm2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGraw T.E., Dunn K.W., Maxfield F.R. Isolation of a temperature-sensitive variant Chinese hamster ovary cell line with a morphologically altered endocytic recycling compartment. J. Cell. Physiol. 1993;155:579–594. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041550316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maxfield F.R., McGraw T.E. Endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akinc A., Querbes W., De S., Qin J., Frank-Kamenetsky M., Jayaprakash K.N., Jayaraman M., Rajeev K.G., Cantley W.L., Dorkin J.R. Targeted delivery of RNAi therapeutics with endogenous and exogenous ligand-based mechanisms. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1357–1364. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilleron J., Querbes W., Zeigerer A., Borodovsky A., Marsico G., Schubert U., Manygoats K., Seifert S., Andree C., Stöter M. Image-based analysis of lipid nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery, intracellular trafficking and endosomal escape. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:638–646. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel S., Ashwanikumar N., Robinson E., DuRoss A., Sun C., Murphy-Benenato K.E., Mihai C., Almarsson Ö., Sahay G. Boosting Intracellular Delivery of Lipid Nanoparticle-Encapsulated mRNA. Nano Lett. 2017;17:5711–5718. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhigaltsev I.V., Belliveau N., Hafez I., Leung A.K.K., Huft J., Hansen C., Cullis P.R. Bottom-up design and synthesis of limit size lipid nanoparticle systems with aqueous and triglyceride cores using millisecond microfluidic mixing. Langmuir. 2012;28:3633–3640. doi: 10.1021/la204833h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bolte S., Cordelières F.P. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bright N.A., Gratian M.J., Luzio J.P. Endocytic delivery to lysosomes mediated by concurrent fusion and kissing events in living cells. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.