Abstract

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis is an autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism that is an often missed but treatable cause of hereditary ataxia. We report a case of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) that was diagnosed only after the development of cognitive decline and adult onset ataxia in a 35-year-old man. He had poor scholastic performance in childhood followed by gradually progressive cognitive decline. He presented to us with severe cerebellar ataxia and oculomotor apraxia. The key features that led to the diagnosis of CTX were the history of cataracts in childhood and Achilles tendon xanthoma. His brain magnetic resonance imaging showed characteristic features of CTX, and the diagnosis was confirmed by demonstrating the mutation in exon 2 of the CYP27A1 gene. The recognition of CTX earlier could have prevented his significant disabilities. The definitive treatment is oral chenodeoxycholic acid, which will prevent the accumulation of the cholestanol, which is thought to be responsible for the neurotoxicity.

Keywords: Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, chenodeoxycholic acid, hereditary ataxia, tendon xanthoma

INTRODUCTION

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is a very rare, autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism with only close to 300 cases reported worldwide[1] and a prevalence of <5/100000.[2] It is caused by mutations in the CYP27A1 gene that encodes the mitochondrial enzyme sterol 27-hydroxylase. Accumulation of sterols causes bilateral cataracts in childhood, tendon xanthomas in adolescence, and progressive neurologic dysfunction beginning in early adulthood. The dominant features are cerebellar ataxia, dementia, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy, and psychiatric disorders. Treatment with the bile acid chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) can prevent the irreversible neuronal injury if started early.

CASE REPORT

A 35-year-old man, first born child of a third degree consanguineous marriage who had delay in all developmental milestones, subnormal intelligence, and a poor scholastic performance, presented with swaying while walking. Till 5 years back, he was active, able to run, and play normally. He spoke fluently and was able to read whole sentences and write his own name. He was poor in calculation and in money handling but did all activities of self-care by himself. He had cataracts in both eyes detected at 14 years of age, surgically corrected. Since the past 5 years, he had reduced talk and interaction with others, reduced laughter and emotions. This gradually progressed to drastically reduced spontaneous speech and lack of self-care. He needed repeated coaxing to do his routine activities and now needs assistance in all activities of self-care. For the past 3 years, he became unable to walk without support with swaying to either side and had recurrent falls and facial injuries multiple times. He also had few episodes of jerking of his body during sleep.

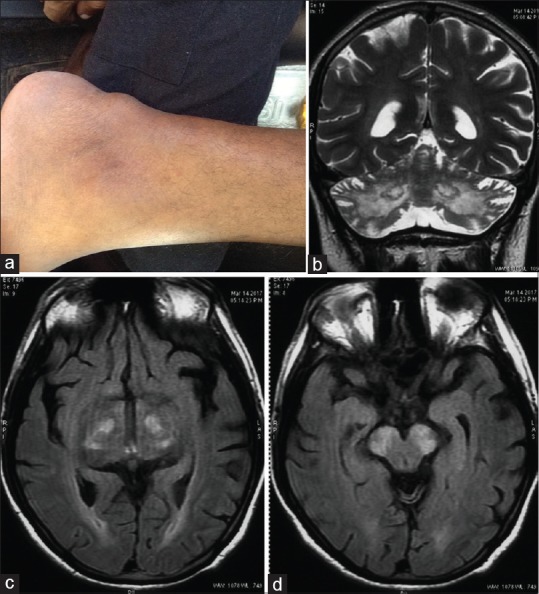

Clinical examination revealed bilateral pseudophakia, left Achilles tendon xanthoma [Figure 1a], clawing of toes, and bilateral pes cavus. He was conscious, oriented, had reduced attention, subnormal intelligence, and memory impairment. Speech was scanning, with reduced fluency, impaired naming and comprehension. He could not read or write. He had slowing of commanded saccadic eye movements and broken pursuit with oculomotor apraxia like head thrusting movement. He had generalized hypotonia, pendular knee jerks, and absent ankle jerks. He had severe truncal and gait ataxia, dysmetria, and intention tremor. He had occasional myoclonic jerks, mostly during sleep.

Figure 1.

(a) Achilles tendon xanthoma. Magnetic resonance imaging brain showing (b) symmetrical cerebellar atrophy and T2 hyperintensity of dendate nuclei, (c) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities in globus pallidus and white matter, (d) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity in substantia nigra

The clinical picture of a hereditary ataxic syndrome with cataracts, peripheral neuropathy, and tendon xanthoma suggested the possibility of CTX. His hemogram, liver, and renal function tests were normal. Electrocardiogram showed right bundle branch block. Tests of thyroid function and serum levels of Alphafetoprotein (AFP), Creatine kinase (CPK), Lactate, Pyruvate and Ammonia were normal. His total cholesterol was 136 mg/dL, and high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and very LDL were 50, 71, and 15 mg/dL, respectively. Electroencephalogram showed diffuse background slowing in delta range, and nerve conduction studies were suggestive of axonal polyneuropathy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his brain showed cerebellar and cerebral atrophy and bilaterally symmetrical T2 and FLAIR hyperintense lesions in dentate nuclei [Figure 1b], globus pallidus [Figure 1c], and substantia nigra [Figure 1d] which was characteristic of CTX. Genetic analysis confirmed our diagnosis by detection of p. Arg127Gly homozygous mutation in exon 2 of CYP27A1 gene on chromosome 2.

DISCUSSION

CTX is an autosomal recessive lipid storage disease, first described in 1937[3] due to mutations in the CYP27A1 gene that codes for the enzyme sterol 27-hydroxylase. Fifty-four different mutations have been described,[4,5] but there is no established correlation between genotype and phenotype. Fifty percent of mutations in CYP27A1 have been detected in the region of exons 6–8, 16% in exon 2, and 14% in exon 4.[6,7] A homozygous missense variation in exon 2 of CYP27A1 gene that results in amino acid substitution of glycine for arginine at codon 127 (p. Arg127Gly) was detected in our case.

The normal catabolism of cholesterol depends on the formation of primary bile acids (cholic acid and CDCA) through various sterol intermediates. Sterol 27-hydroxylase catalyzes the hydroxylation of 5 beta-cholestane-3 alpha, 7 alpha, and 12 alpha-triol at C27.[8] The deficiency of sterol 27-hydroxylase leads to disruption of bile acid synthesis, which in turn causes the upregulation of CYP7A, the gene encoding cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase, which catalyzes the conversion of cholesterol and 7 alpha-hydroxycholesterol to cholestanol.[9] Hence, cholestanol accumulates. Bile acids are also necessary for feedback inhibition of hepatic hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA), which is involved in regulating cholesterol production.[10] In CTX, increased activity of hepatic HMG-CoA reductase causes elevated synthesis of cholesterol, thereby enhancing hepatic secretion of apoB-containing lipoproteins. LDL receptors are upregulated, resulting in normal serum cholesterol levels in CTX.[11]

CTX should be suspected in patients with a combination of clinical features starting from birth including neonatal cholestatic jaundice, infantile diarrhea, premature cataracts presenting in childhood,[12] tendon xanthomas presenting during adolescence or early adulthood,[13] progressive neurologic dysfunction beginning in late childhood or early adulthood, ataxia or spastic paraparesis, and intellectual disability or psychiatric disturbances along with MRI evidence of dentate nuclei signal alterations.[14] Having siblings with CTX and consanguineous parents should also raise suspicion of CTX. In patients with mental retardation who have a component of progressive neurologic disease, CTX deserves special consideration because of its response to treatment. It should be noted that the symptoms might also start in adulthood.[15]

The presence of oculomotor apraxia in our patient prompted us to also consider other hereditary ataxias such as ataxia telangiectasia and ataxia with ocular apraxia type 2, but the absence of telangiectasia and normal alpha-fetoprotein levels, respectively, pointed against the favor of these. Moreover, cataracts and tendon xanthomas were strong pointers toward CTX. Even though a broad range of neurological features in CTX have been described in literature including dystonia and palatal myoclonus, oculomotor apraxia has not been reported as a feature of this disease. The head thrusting movement in oculomotor apraxia is related to impaired saccadic initiation, saccadic hypometria, abnormal smooth pursuit, and difficulty suppressing the vestibulo-ocular reflex while tracking an object moving with head rotation. Nevertheless, it is a nonspecific sign that has been described in a wide variety of underlying conditions including many storage diseases and insults to the developing brain in the perinatal period or in the first 6 months of birth. Hence, even though not reported yet, it is very well plausible that CTX could cause oculomotor apraxia.

Finally, the MRI revealed characteristic changes described in CTX: cerebellar atrophy, white matter signal alterations, and symmetric hyperintensities in the dentate nuclei, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, and inferior olive. These are thought to be due to the accumulation of sterols in the nerve cells along with varying degrees of demyelination. The cerebellar predominance of white matter changes and bilateral focal lesions in cerebellum help distinguish the radiographic features of CTX from other leukodystrophies.

Early detection and diagnosis of CTX is crucial because early and long-term treatment with CDCA improves neurological symptoms and even reverses the progression of the disease.[2] However, an obvious delay between symptom onset and diagnosis is prevalent.[2] Therapy for CTX involves administration of bile acids such as CDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), cholic acid, or taurocholic acid. Compared to administration of UDCA or taurocholic acid, CDCA treatment (750 mg/d) is the therapy of choice for treating the neurological and nonneurological symptoms of CTX. The potential mechanism of action of bile acids might be feedback inhibition of endogenous bile acid synthesis pathway, thereby reducing cholestanol accumulation. Combination therapy with CDCA (300 mg/d) and pravastatin (10 mg/d) can also be used to improve lipoprotein metabolism, inhibit cholesterol synthesis, and reduce plasma levels of cholestanol. The efficacy of treatment with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors alone is controversial.

Our patient is being treated currently with UDCA along with other symptomatic therapy.

CONCLUSION

Even though a very rare genetic disease affecting bile acid metabolism, CTX is a diagnosis that should never be missed because the neurological dysfunction resulting from it can be fully prevented by early and continuous replacement therapy with CDCA. It should be suspected in any patient with neonatal cholestatic jaundice, infantile diarrhea, and bilateral cataracts in childhood and tendon xanthomas in adolescence. Neurological signs appear in early adulthood as ataxia, spasticity, extrapyramidal features, dementia, and psychiatric abnormalities. Characteristic MRI appearance of bilateral cerebellar atrophy and dentate and white matter hyperintensities support the diagnosis, which is confirmed by genetic studies.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barkhof F, Verrips A, Wesseling P, van Der Knaap MS, van Engelen BG, Gabreëls FJ, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: The spectrum of imaging findings and the correlation with neuropathologic findings. Radiology. 2000;217:869–76. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc03869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilo-de-la-Fuente B, Jimenez-Escrig A, Lorenzo JR, Pardo J, Arias M, Ares-Luque A, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Spain: Clinical, prognostic, and genetic survey. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:1203–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Bogaert L, Schere H, Epstein E. Paris: Masson et Cie; 1937. Generalised form of cerebral cholesterosis. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallus GN, Dotti MT, Federico A. Clinical and molecular diagnosis of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with a review of the mutations in the CYP27A1 gene. Neurol Sci. 2006;27:143–9. doi: 10.1007/s10072-006-0618-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Federico A, Dotti MT, Gallus GN. Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis. GeneReviews. [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1409/

- 6.Lorbek G, Lewinska M, Rozman D. Cytochrome P450s in the synthesis of cholesterol and bile acids – From mouse models to human diseases. FEBS J. 2012;279:1516–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider H, Lingesleben A, Vogel HP, Garuti R, Calandra S. A novel mutation in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene of a woman with autosomal recessive cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leitersdorf E, Reshef A, Meiner V, Levitzki R, Schwartz SP, Dann EJ, et al. Frameshift and splice-junction mutations in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene cause cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Jews Or Moroccan origin. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2488–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI116484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crestani M, Sadeghpour A, Stroup D, Galli G, Chiang JY. Transcriptional activation of the cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A) by nuclear hormone receptors. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:2192–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjorkhem I, Boberg KM, Leitersdorf E. Inborn errors in bile acid biosynthesis and storage of sterols other than cholesterol. In The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler KW, editors. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2001. pp. 2961–88. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tint GS, Ginsberg H, Salen G, Le NA, Shefer S. Chenodeoxycholic acid normalizes elevated lipoprotein secretion and catabolism in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Lipid Res. 1989;30:633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatterjee G, Chakraborthy I, Das TK, Dutta C. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in a family. Indian J Dermatol. 1999;44:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaikwad SB, Garg A, Mishra NK, Gupta V, Srivastava A, Sarkar C, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: Neuroimaging findings in two siblings from an Indian family. Neurol India. 2003;51:401–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mignarri A, Gallus GN, Dotti MT, Federico A. A suspicion index for early diagnosis and treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37:421–9. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keren Z, Falik-Zaccai TC. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX): A treatable lipid storage disease. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2009;7:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]