Abstract

Background:

Radical prostatectomy (RP) represents an important acquired risk factor for the development of primary inguinal hernias (IH) with an estimated incidence rates of 15.9% within the first 2 years after surgery. The prostatectomy-related preperitoneal fibrotic reaction can make the laparoendoscopic repair of the IH technically difficult, even if safety and feasibility have not been extensively evaluated yet. We conducted a systematic review of the available literature.

Methods:

A comprehensive computer literature search of PubMed and MEDLINE databases was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Terms used to search were (‘laparoscopic’ OR ‘laparoscopy’) AND (‘inguinal’ OR ‘groin’ OR ‘hernia’) AND ‘prostatectomy’.

Results:

The literature search from PubMed and MEDLINE databases revealed 156 articles. Five articles were considered eligible for the analysis, including 229 patients who underwent 277 hernia repairs. The pooled analysis indicates no statistically significant difference of post-operative complications (Risk Ratios [RR] 2.06; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.85–4.97), conversion to open surgery (RR 3.91; 95% CI 0.85–18.04) and recurrence of hernia (RR 1.39; 95% CI 0.39–4.93) between the post-prostatectomy group and the control group. There was a statistically significant difference of minor intraoperative complications (RR 4.42; CI 1.05–18.64), due to an injury of the inferior epigastric vessels.

Conclusions:

Our systematic review suggests that, in experienced hands, safety, feasibility and clinical outcomes of minimally invasive repair of IH in patients previously treated with prostatectomy, are comparable to those patients without previous RP.

Keywords: Groin, hernia, inguinal, prostatectomy, transabdominal preperitoneal, totally extraperitoneal

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in men, with an estimated 1.1 million diagnoses worldwide in 2012, accounting for 15% of all cancers diagnosed in men.[1] Radical prostatectomy (RP) is considered the gold standard for treating localised prostate cancer[2] and can be performed by open, laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach. However, RP is an important acquired risk factor for the development of primary inguinal hernias (IH).[3] In a meta-analysis of Zhu et al., the estimated incidence rates of post-operative IH after RP and laparoscopic RP are 15.9% and 6.7%, respectively, most of them occurring within the first 2 years after surgery.[4]

IH repair is one of the most common elective operations performed in general surgical practice.[5] Worldwide, more than 20 million patients undergo groin hernia repair annually. According to the ‘World Guidelines for Groin Hernia Management’, for male patients with primary IH, a transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) or totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic IH Repair is recommended because of a lower post-operative pain incidence and a reduction in chronic pain incidence.[3] Patients presenting with IH after RP are often considered for anterior repair,[5] since the prostatectomy-related preperitoneal fibrotic reaction can make the laparoendoscopic repair technically difficult.

Is laparoendoscopic hernia repair feasible, safe and effective in patients with the previous RP? To clarify this question, we conducted a systematic review of the available literature.

METHODS

The systematic review was carried out on previously published studies; patients’ consent and ethical approval were not required.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

A comprehensive computer literature search of PubMed, Cochrane Library and MEDLINE databases was carried out independently by two researchers to find relevant published articles (the last search was updated on 1st January 2018) in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.[6] Terms used to search were ‘laparoscopic’ OR ‘laparoscopy’) AND (‘inguinal’ OR ‘groin’ OR ‘hernia’) AND ‘prostatectomy’). Finally, we searched for additional eligible trials in reference lists. Language restrictions were set to English. The study designs considered eligible for the analysis were retrospective, prospective and randomised trials. Case reports, small case series, letters, editorials and conference proceedings were excluded from the study.

Data collection and quality assessment

Studies or subsets in studies investigating the role of laparoscopic IH repair after RP was eligible for inclusion. The following inclusion criteria were applied to select studies for this meta-analysis: Patients treated by RP, laparoscopic repair of IH performed by expert surgeons only. Exclusion criteria were as follows: concomitant prostatectomy and IH repair, open IH repair.

We extracted study characteristics (author name, publication year, country, sample size, age, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria and primary outcomes). Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion. Only studies providing complete information were included in our study. Three researchers independently reviewed titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles, applying the above-mentioned selection criteria. The same three researchers then independently evaluated the full-text version of the included articles to determine their eligibility for inclusion. Outcome measures considered were intraoperative minor and major complications, conversions to open surgery, post-operative complications and the recurrence rate.

The risk of bias and the quality assessments of studies included in the meta-analysis were independently performed by two reviewers according to the study quality assessment of controlled intervention studies National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).[7] Ultimately, the overall quality of evidence was graded with Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE approach).[8]

Statistical methods

Meta-analysis was performed by pooling the Risk Ratios (RR) of each study i.e., P1/P0, where P1 and P0 are the proportions of complication in patients and controls, respectively. When a study reported zero complications in patients or controls, 0.5 was added to the numerator and denominator of both proportions to avoid the RR equal to zero or infinite. When the control group was missing in a study, P0 was replaced by the proportion obtained by combining the control groups of the other studies. The pooled estimate of RRs was computed by means of the random effects model following the method of DerSimonian and Laird.[9](This model allowed to estimate the amount of variability between studies and accordingly provided suitable estimates of the standard error of the pooled RR. The Higgins’ I2 index[10] was computed to assess the percentage of total cross-study variation due to heterogeneity rather than chance. A forest plot was generated to display results. We carried out the sensitivity analysis to assess whether the pooled estimate is strongly dependent on one of the studies collected, by iteratively recalculating the pooled RR after exclusion of each study at a time. The funnel plot was examined to test the occurrence of publication bias. For small-study effect is meant that the chance of a smaller study being published is increased if it shows a stronger effect. The small-study effect is a term that describes increased chance of a smaller study in being published when it shows a stronger effect. The smaller study-effect was assessed by means of the Harbord's test.[11] STATA software was used for all statistical analyses and the generation of forest plot (StataCorp.[2015] Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP).

RESULTS

Literature search

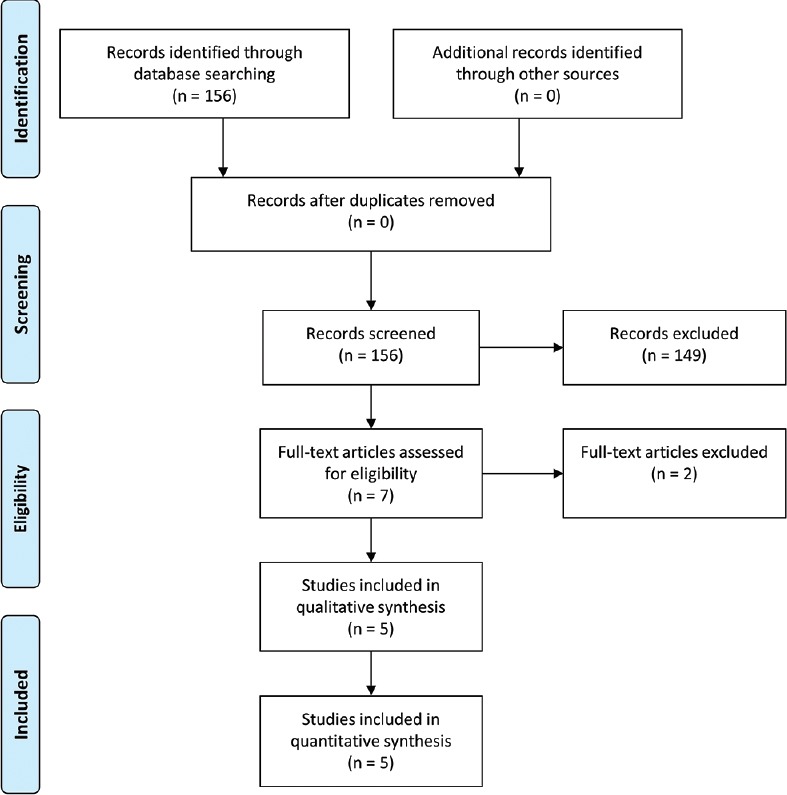

The literature search from PubMed and MEDLINE databases revealed 156 articles [Figure 1]. Results have been matched, and no duplicated studies were found. Reviewing titles and abstracts, 149 records were excluded because not matching the main topic. Two articles were excluded since they did not respect the inclusion criteria. Five articles including 229 patients who underwent 277 (181 unilateral and 48 bilateral) minimally invasive hernia repairs after prostatectomy were selected and were eligible for the study; no additional studies were found screening the references of these articles.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of the selection of relevant articles according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-guidelines

Study characteristics

The eligible trials were monocentric studies from five different countries (France, Germany, Japan, Brazil and Australia). Three studies evaluated the surgical outcome of TAPP, and two studies evaluated the surgical outcome of TEP. The characteristics of the included studies[5,12,13,14,15] are showed in Table 1. All studies provided information about minor and major intra- and post-operative complications, rate of conversion to open surgery and recurrence rate. There were no major intraoperative complications (bowel, bladder or major vessel injury) in the patients who underwent minimally invasive hernia repair after prostatectomy. Minor intraoperative complications were documented in 3 of 277 (1.1%) hernia operations after prostatectomy and were all injuries of the inferior epigastric vessels, which were managed by clipping the vessels. One trocar hernia was documented postoperatively on 277 (0.4%) hernia operations after prostatectomy. Other post-operative complications (seroma and hematoma) were documented in 16 of 277 (5.8%) hernia operations after prostatectomy. In one of 277 (0.4%) minimally invasive hernia operations there was a conversion to open surgery. There was no reported recurrence of hernia in the patients who underwent TEP or TAPP after prostatectomy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected studies considered in the systematic review

| Claus et al.[5] | Dulucq et al.[12] | Le Page et al.[13] | Sakon et al.[14] | Wauschkuhn et al.[15] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective | Prospective case-control | Prospective case-control | Retrospective | Prospective | ||||||

| Prostatectomy | No control | Prostatectomy | Control | Prostatectomy | Control | Prostatectomy | No control | Prostatectomy | Control | |

| Number of patients | 20 | 10 | 124 | 52 | 102 | 40 | 107 | 10,962 | ||

| Number of hernias | 25 | 10 | 124 | 65 | 138 | 45 | 132 | |||

| Type of repair | TAPP | TEP | TEP | TEP | TEP | TAPP | TAPP | TAPP | ||

| Minor intraoperative complications (n) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Major intraoperative complications | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Conversions to open | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Post-operative complications, n (%) | 4 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 2.8% | ||

| Recurrence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.7% | ||

TAPP or TEP laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. TEP: Totally extraperitoneal, TAPP: Transabdominal preperitoneal

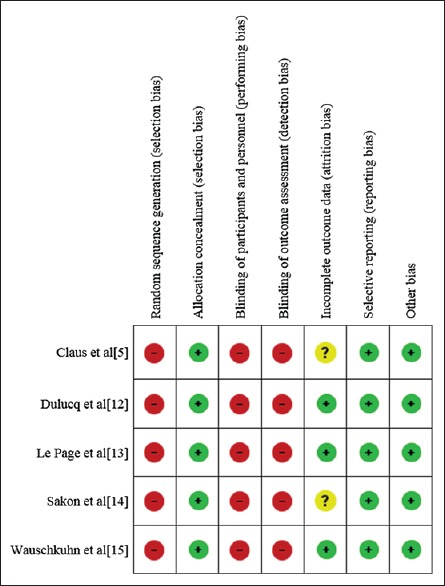

The risk of bias among included studies is reported in Figure 2. According to the study quality assessment of controlled intervention studies NHLBI,[7] the studies of Claus et al.,[5] Sakon et al.,[14] Wauschkuhn et al.[15] were classified as ‘fair’ and the studies of Le Page et al.[13] and Sakon et al.[14] were classified as ‘good’. According to the GRADE approach, the quality of evidence of this meta-analysis was ‘low’.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies

Statistical results

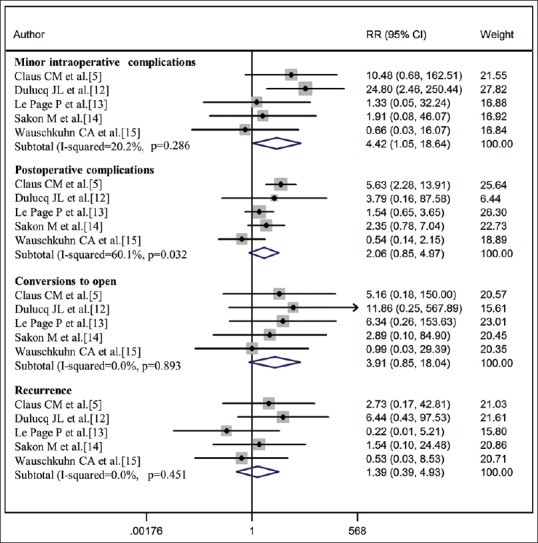

The pooled analysis indicates no statistically significant difference of post-operative complications (RR 2.06; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.85–4.97), conversion to open surgery (RR 3.91; 95% CI 0.85–18.04) and recurrence of hernia (RR 1.39; CI 0.39–4.93) between the post-prostatectomy group and the control group. There was a statistically significant difference of minor intraoperative complications (RR 4.42; CI 1.05–18.64), due to an injury of the inferior epigastric vessels during 3 of 277 minimally-invasive IH repairs after prostatectomy [Figure 3]. The Harbord test excluded the occurrence of small-study effects in all endpoints. Moreover, the funnel plot did not reveal the occurrence of publication bias.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the statistical analysis. It is described the Risk Ratios, the 95% confidence interval and the subtotal I-squared for all the studies included

DISCUSSION

RP is a risk factor associated with IH formation.[3] In a meta-analysis of 2013, Zhu et al. evaluated the incidence of IH after RP: An IH developed in 15.9% (95% CI 13.1–18.7) of patients who underwent this procedure.[4] After minimally invasive resection (laparoscopic RP, minimum incision endoscopic RP and robot-assisted RP) a lower rate of 6.7% (95% CI 4.8–8.6) was observed.[4] Besides the low midline incision, additional risk factors for a post-prostatectomy IH are advanced patient age, low body mass index and previous IH repair.[4]

It is estimated that 962,917 men underwent RP from 1998 to 2010 in the USA with a relatively stable annual rate (1425 RPs per million in the period 1998–1999 to 1330 RPs per million in the period 2010–2011).[16] Consequently, physicians are faced with a large number of post-prostatectomy IH every year. Interestingly, several authors over the last years described their experience of robotic RP with concomitant repair of IH.[17]

Hernia repair techniques vary broadly, dependent on setting. Laparo-endoscopic surgery use varies from zero to a maximum of approximately 55% in some high resource countries. The average use in high resource countries is largely unknown except for some examples such as Australia (55%), Switzerland (40%), the Netherlands (45%) and Sweden (28%).[15] According to the ‘World Guidelines for Groin Hernia Management’,[3] drawn up by an international expert group of surgeons (the HerniaSurge Group), surgical treatment of IH should be tailored to the surgeon's expertise, patient- and hernia-related characteristics and local/national resources. Mesh repair is recommended as the first choice, either by an open procedure or a laparo-endoscopic repair technique. HerniaSurge suggests Lichtenstein or laparo-endoscopic repair (TEP or TAPP) as optimal techniques. Provided that resources and expertise are available, laparo-endoscopic techniques have faster recovery times, lower chronic pain risk and are cost-effective’.[3]

As a matter of fact, patients presenting with IH after RP are often considered for anterior repair[5,18] to avoid the disadvantage of operating in a fibrotic, scarred preperitoneal space. Some authors suggested that previous RP should contraindicate a laparoscopic approach because of the associated scarring in the preperitoneal space.[13]

We conducted a review of the available literature and an analysis of the provided data, finding no difference of major intraoperative complications, post-operative complications, conversion to open surgery and recurrence of hernia in patients treated with TEP or TAPP after prostatectomy compared to patients without previous lower abdominal surgery. There was a statistically significant difference of minor intraoperative complications (RR 4.42; CI 1.05–18.64). This was due to an injury of the inferior epigastric vessels in 3 of 277 cases, which were anyway managed by simply clipping the vessels. Dulucq et al. reported in their study two cases of conversion from TEP to TAPP,[12] so that, a minimally invasive approach was effective and conversions to open surgery were not described.

This study has several limitations. First, we used four prospective and one retrospective studies. In addition, two studies had no control group, so that when the control group was missing in a study, P0 (the proportion of complications in the control group) was replaced by the proportion obtained by combining the control groups of the other studies.

A source of heterogeneity is represented by the different techniques of prostatectomy and hernia repair of the included studies. In fact, the selected papers described the surgical outcome of laparo-endoscopic hernia repair after open, laparoscopic- and robot-assisted RP. Nevertheless, regardless of the technique used, the pre-peritoneal space is violated and dissected, so that an intense fibrosis in the pre-peritoneal region is observed almost in all patients following RP.[5] A subgroup analysis according to the type of RP was taken into account but not feasible due to the small amount of patients.

Three of the selected papers evaluated the surgical outcome of TAPP; the other two described the surgical outcome of TEP in patients who previously underwent prostatectomy. In patients with IH and no previous lower abdominal surgery, TEP and TAPP have comparable outcomes; hence, it is recommended that the choice of the technique should be based on the surgeon's skills, education and experience.[3]

In all selected studies, laparoendoscopic IH repairs in patients previously having undergone prostatectomy were performed by surgeons with advanced experience in minimally invasive hernia repair. Wauschkuhn et al.[15] performed 264 TAPP repair from 1996 to 2006 in patients previously treated with prostatectomy. For the analysis of the learning curve, the authors divided the 264 laparoscopic TAPPs after prostatectomy into two subgroups, resulting in 132 TAPPs per group according to the time interval during which they were operated on (first subgroup 1996–2002, second subgroup 2002–2006). The authors observed an overall decrease in the morbidity from 9.8% in the first subgroup to 1.5% in the second subgroup. To avoid bias related to the learning curve, we used for our meta-analysis only the second subgroup and results of this meta-analysis may be appropriate for expert surgeons only. Moreover, we cannot provide any data about the long-term recurrence rate of IH in a patient treated with TEP or TAPP and previous RP, as the included studies had different follow-up lengths up to 8 months. Finally, we applied the GRADE approach[8] to evaluate the quality and taking into account the limitations mentioned above, the quality of evidence of our paper was ‘low’.

CONCLUSIONS

Our meta-analysis suggests that, in experienced hands, TAPP and TEP are safe and feasible for the treatment of IH in patients previously treated with prostatectomy. Clinical outcomes are comparable to those in patients without previous RP. However, considering the above-mentioned limitations, further studies are needed to confirm our hypothesis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. Lyon, France: Int Agency Res Cancer; 2016. Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012 v1.0. IARC Cancer Base. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, Mason M, Matveev V, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol. 2011;59:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernia Surge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018;22:1–165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu S, Zhang H, Xie L, Chen J, Niu Y. Risk factors and prevention of inguinal hernia after radical prostatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2013;189:884–90. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claus CM, Coelho JC, Campos AC, Cury Filho AM, Loureiro MP, Dimbarre D, et al. Laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty after radical prostatectomy: Is it safe? Prospective clinical trial. Hernia. 2014;18:255–9. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Study Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools .

- 8.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harbord RM, Harris RJ, Sterne JA. Updated tests for small-study effects in meta-analyses. Stata J. 2009;9:197–210. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Mahajna A. Totally extraperitoneal (TEP) hernia repair after radical prostatectomy or previous lower abdominal surgery: Is it safe? A prospective study. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:473–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-3027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Page P, Smialkowski A, Morton J, Fenton-Lee D. Totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair in patients previously having prostatectomy is feasible, safe, and effective. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4485–90. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakon M, Sekino Y, Okada M, Seki H, Munakata Y. Laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty after robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Hernia. 2017;21:745–8. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wauschkuhn CA, Schwarz J, Bittner R. Laparoscopic transperitoneal inguinal hernia repair (TAPP) after radical prostatectomy: Is it safe? Results of prospectively collected data of more than 200 cases. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:973–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyson MD, 2nd, Andrews PE, Ferrigni RF, Humphreys MR, Parker AS, Castle EP, et al. Radical prostatectomy trends in the United States: 1998 to 2011. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soto-Palou FG, Sánchez-Ortiz RF. Outcomes of minimally invasive inguinal hernia repair at the time of robotic radical prostatectomy. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18:43. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0690-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winslow ER, Quasebarth M, Brunt LM. Perioperative outcomes and complications of open vs. laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair in a mature surgical practice. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:221–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8934-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]