Abstract

Background:

Extensive research into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers was performed in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH). Most prior research into CSF biomarkers has been one-point observation.

Objective:

To investigate dynamic changes in CSF biomarkers during routine tap test in iNPH patients.

Methods:

We analyzed CSF concentrations of tau, amyloid-β (Aβ) 42 and 40, and leucine rich α-2-glycoprotein (LRG) in 88 consecutive potential iNPH patients who received a tap test. We collected two-point lumbar CSF separately at the first 1 ml (First Drip (FD)) and at the last 1 ml (Last Drip (LD)) during the tap test and 9 patients who went on to receive ventriculo-peritoneal shunt surgery each provided 1 ml of ventricular CSF (VCSF).

Results:

Tau concentrations were significantly elevated in LD and VCSF compared to FD (LD/FD = 1.22, p = 0.003, VCSF/FD = 2.76, p = 0.02). Conversely, Aβ42 (LD/FD = 0.80, p < 0.001, VCSF/FD = 0.38, p = 0.03) and LRG (LD/FD = 0.74, p < 0.001, VCSF/FD = 0.09, p = 0.002) concentrations were significantly reduced in LD and VCSF compared to FD. Gait responses to the tap test and changes in cognitive function in response to shunt were closely associated with LD concentrations of tau (p = 0.02) and LRG (p = 0.04), respectively.

Conclusions:

Dynamic changes were different among the measured CSF biomarkers, suggesting that LD of CSF as sampled during the tap test reflects an aspect of VCSF contributing to the pathophysiology of iNPH and could be used to predict shunt effectiveness.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β, cerebrospinal fluid biomarker, idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, leucine rich α-2-glycoprotein, tap test, tau

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is a common age-related neurological disease first described in 1965 [1]. The tap test is routinely performed for potential iNPH patients and extensive research into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers was performed, but an iNPH-specific CSF biomarker with strong evidence has not yet been found.

iNPH affects the elderly and often includes comorbidities, particularly Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology [2], which can exacerbate iNPH symptoms. We therefore considered the potential for elevated CSF concentrations of the AD hallmark tau in patients with iNPH. We previously demonstrated that total tau concentrations as well as tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 in CSF were paradoxically low in iNPH patients [3], and we have had difficulty interpreting this result.

Surprisingly, total tau concentrations were dramatically elevated in ventricular CSF (VCSF) relative to lumbar CSF (LCSF) in patients with iNPH [4], indicating that some LCSF biomarkers including total tau do not accurately reflect the pathological brain conditions in iNPH.

The pathophysiological basis of iNPH is impaired CSF circulation [5], and CSF biomarker concentrations can change when CSF drainage removes the obstacle to circulation. Interestingly, an external lumbar drainage study revealed a 2-fold increase in total tau concentrations in CSF drained at 48 h from the beginning of treatment [6].

We hypothesized that tau concentrations are significantly underestimated in the CSF of patients with iNPH as obtained by conventional spinal tap. We aim to clarify whether dynamic changes in biomarker concentrations could be detected between the beginning and end of a routine tap test in patients with iNPH.

METHODS

Patient inclusion and classification

Patients with possible iNPH according to the Japanese iNPH guidelines were eligible for the study. Participants were enrolled between 2015 and 2017 from two hospitals, Atsuchi Neurosurgical Hospital and Otowa Hospital. All patients received a tap test for their diagnosis [7] and patients with a prospective outcome underwent lumbo-peritoneal (LP) shunt or ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunt surgery. Each patient received a standardized neurological evaluation, and iNPH patients fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for possible iNPH were selected by an Evans index (EI) >0.3 on CT imaging. Gait and cognitive function were evaluated by the timed up & go test (TUG) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), respectively. Tap test gait responders (Rs) were defined as patients whose TUG time improved more than 10%, and patients who did not respond to the tap test were defined as non-responders (NRs). Patients with an MMSE score improvement of 3 points or more one month following surgery were defined as MMSE Rs, and the remaining patients were defined as MMSE NRs. Each patient received a score on iNPH grading scale (iNPHGS) [8]. Patients who underwent shunt surgery were scored on iNPHGS again one month after the operation. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Kyoto University and both participating hospitals, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

CSF biomarker analyses

A lumbar puncture for the tap test was performed on each patient according to a standardized protocol. During the tap test, we collected the first 1 ml of CSF (First Drip (FD): 0 to 1 ml) and the last 1 ml of CSF (Last Drip (LD): 29 to 30 ml) separately.

Patients who went on to receive shunt surgery with the VP method also provided 1 ml of VCSF. All CSF samples were collected in sterile polypropylene tubes and were centrifuged 10 min at 2,000 rpm, and aliquots were stored at –80°C for subsequent biomarker assay.

We analyzed CSF concentrations of tau, amyloid-β (Aβ), and leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein (LRG) with an ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Tau (Total) Human ELISA Kit – Novex, Human Amyloid β (1–42) and (1–40) Assay Kit – IBL, and Human LRG Assay Kit – IBL).

Statistics

Comparisons among groups were performed using Chi-square tests, and results are indicated as medians and 25th–75th percentiles. Correlation studies were performed using Pearson correlation (r) and Spearman correlation (rs). The statistical threshold was defined at p < 0.05. All data analyses were performed using BellCurve for Excel and JMP® 14 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Study participants

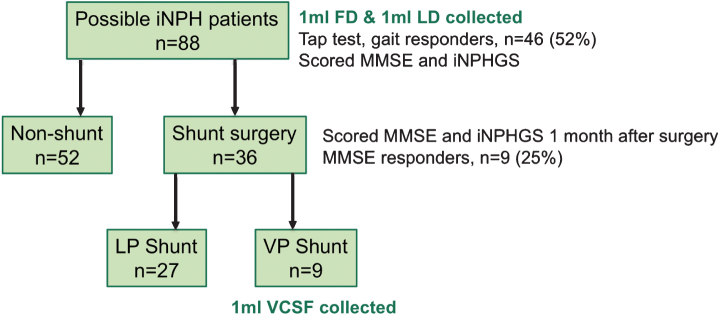

A total of 88 iNPH patients were consecutively recruited to the study, and FD and LD were collected at the tap test for all patients (Fig. 1). Subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1. 46 patients showed a gait response to the tap test and 36 patients underwent shunt surgery. Of these, 9 patients received the VP method and their characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Fig.1.

Overview of study sample. iNPH, idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus; iNPHGS, iNPH Grading Scale; FD, First Drip; LD, Last Drip; LP, lumbo-peritoneal; VP, ventriculo-peritoneal; VCSF, ventricular CSF.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects and concentrations of CSF biomarkers

| iNPH | ||||

| n | 88 | |||

| Agea | 78.9 (6.6) | |||

| EIa | 0.32 (0.04) | |||

| MMSEa | 19.8 (6.6) | |||

| iNPHGSa | 7.0 (6.6) | |||

| FD | LD | p | LD/FD ratio | |

| tau (pg/ml)b | 115 (72–169) | 131 (87–236) | 0.003 | 1.22 (0.94–1.51) |

| Aβ42 (pM)b | 50.0 (30.3–85.1) | 39.1 (24.7–70.8) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.68–0.94) |

| Aβ40 (pM)b | 1695 (1293–1961) | 1641 (1279–1961) | N.S. | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) |

| LRG (pg/ml)b | 175 (109–229) | 160 (95–160) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.64–0.95) |

iNPH, idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus; EI, Evans index; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; iNPHGS, iNPH Grading Scale; FD, First Drip; LD, Last Drip; tau, total tau; Aβ, amyloid-β; LRG, leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein. aMean and SD, bMedian value (25th–75th percentile).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the subjects who underwent VP shunt and concentrations of CSF biomarkers

| iNPH VP | |||||

| n | 9 | ||||

| Agea | 73.9 (4.1) | ||||

| EIa | 0.37 (0.05) | ||||

| MMSEa | 22.8 (4.2) | ||||

| iNPHGSa | 5.1 (1.7) | ||||

| FD | LD | VCSF | p (FD versus VCSF) | VCSF/FD ratio | |

| tau (pg/ml)b | 113 (59–130) | 105 (74–139) | 278 (193–369) | 0.02 | 2.76 (1.44–4.75) |

| Aβ42 (pM)b | 44.4 (27.6–62.3) | 31.2 (21.1–59.0) | 15.3 (10.7–34.4) | 0.03 | 0.38 (0.22–0.61) |

| Aβ40 (pM)b | 1223 (976–1551) | 1355 (733–1628) | 197 (92–726) | 0.002 | 0.18 (0.14–0.59) |

| LRG (pg/ml)b | 178 (89–179) | 117 (52–132) | 19 (15–31) | 0.002 | 0.09 (0.06–0.45) |

iNPH, idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus; EI, Evans index; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; iNPHGS, iNPH Grading Scale; FD, First Drip; LD, Last Drip; VP, ventriculo-peritoneal; VCSF, ventricular CSF; tau, total tau; Aβ, amyloid-β; LRG, leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein. aMean and SD, bMedian value (25th–75th percentile).

CSF biomarker concentrations at First Drip, Last Drip, and in ventricular CSF

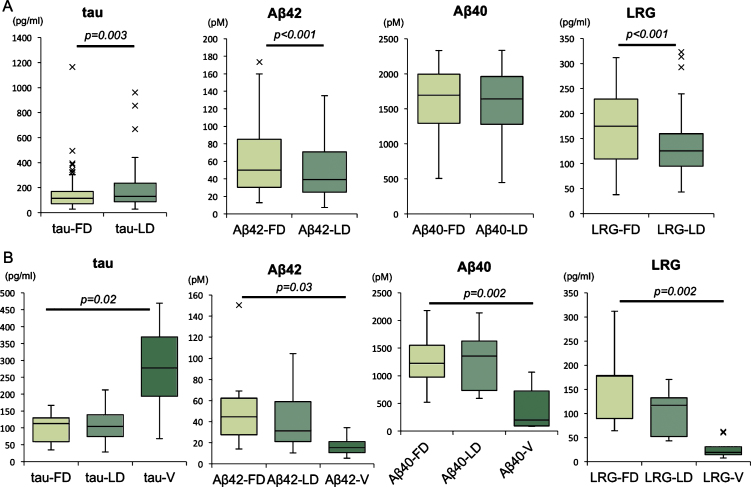

CSF tau concentrations were significantly elevated in LD compared to FD (LD/FD = 1.22, p = 0.003), while CSF concentrations of Aβ42 (LD/FD = 0.80, p < 0.001) and LRG (LD/FD = 0.74, p < 0.001) were significantly reduced in LD compared to FD (Fig. 2A).

Fig.2.

CSF biomarker concentrations of tau, Aβ42, Aβ40, and LRG. CSF biomarkers compared between FD and LD in studied samples (A), CSF biomarkers compared among FD, LD, and VCSF in patients received VP shunt (B). Horizontal lines within boxes show median values, boxes show upper and lower interquartile (IQ) ranges, whiskers indicate the 1.5 times IQ, a cross (x) in the figure indicate outlier values (1.5 times IQ). tau, total tau; Aβ, amyloid-β; LRG, leucine rich α-2-glycoprotein; FD, First Drip; LD, Last Drip; V, ventricular CSF.

VCSF tau concentrations were high compared to FD concentrations (VCSF/FD = 2.76, p = 0.02), while VCSF Aβ42 (VCSF/FD = 0.38, p = 0.03), Aβ40 (VCSF/FD = 0.18, p = 0.002), and LRG (VCSF/FD =0.09, p = 0.002) concentrations were low (Fig. 2B).

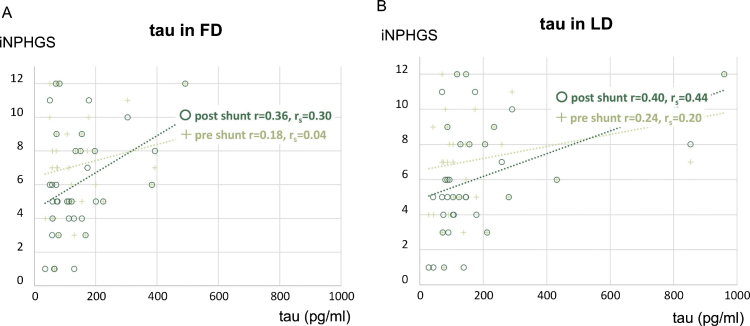

Association of CSF biomarkers and clinical characteristics

Gait response to tap test and changes in cognitive function following shunt surgery were closely associated with LD concentrations of tau (p = 0.02) and LRG (p = 0.04), respectively (Table 3). Tau concentrations had a more positive correlation with post-shunt iNPHGS than pre-shunt iNPHGS, and tau concentrations in LD were most correlated to the post-shunt iNPHGS (r = 0.40, rs = 0.44) (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of CSF biomarkers and clinical characteristics

| A) Comparison of tau in Gait Rs and NRs to tap test | |||

| Gait Rs | Gait NRs | p | |

| n | 46 | 42 | |

| Age (y)a | 77.7 (6.7) | 80.1 (6.3) | N.S. |

| EIa | 0.32 (0.05) | 0.32 (0.03) | N.S. |

| TUG responsea | 1.35 (0.83) | 0.95 (0.41) | 0.01 |

| Tau FDb | 110 (71–158) | 125 (80–206) | 0.04 |

| Tau LDb | 108 (78–198) | 158 (94–274) | 0.02 |

| B) Comparison of LRG in MMSE Rs and NRs to shunt surgery | |||

| MMSE Rs | MMSE NRs | p | |

| n | 9 | 27 | |

| Age (y)a | 76.9 (4.5) | 77.8 (7.0) | N.S. |

| EIa | 0.35 (0.05) | 0.31 (0.04) | N.S. |

| MMSE improvementa | 4.0 (3.0) | –0.3 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| LRG FDb | 112 (82–179) | 179 (137–239) | 0.16 |

| LRG LDb | 74 (53–134) | 127 (101–195) | 0.04 |

Rs, Responders; NRs, non-responders; EI, Evans index; TUG, timed up & go; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; FD, First Drip; LD, Last Drip; tau, total tau; LRG, leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein. aMean and SD, bMedian value (25th–75th percentile).

Fig.3.

Relationship of CSF tau concentrations (FD and LD) to iNPHGS (pre- and post-shunt surgery). Association between CSF tau concentrations in FD and iNPHGS (A) and association between CSF tau concentrations in LD and iNPHGS (B). tau, total tau; iNPHGS, iNPH Grading Scale; FD, First Drip; LD, Last Drip; r, Pearson correlation; rs, Spearman correlation

DISCUSSION

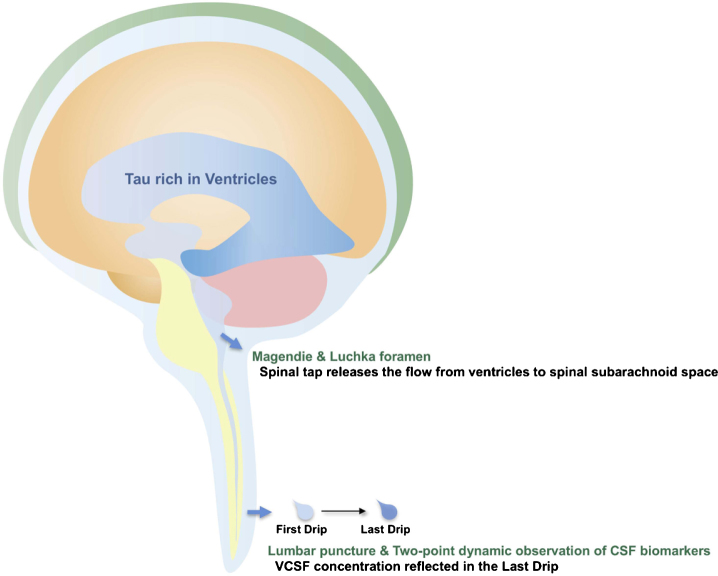

The primary observation in this study is the significant change in CSF biomarkers between FD and LD as obtained through the tap test in patients with iNPH. Interestingly, the dynamics were different for each biomarker. As expected, tau concentrations were increased in the LD relative to the FD, while concentrations of Aβ and LRG were decreased in the LD. A similar but larger change was observed in VCSF/FD for each CSF biomarker concentrations. We infer that the LD reflects the VCSF biomarker concentration, which may be biologically plausible. The subarachnoid space below the foramina of Magendie & Luchka is described in neurosurgery textbooks as having a volume of approximately 75 ml, which is half of the total amount of CSF. When 30 ml of CSF is drained by a tap test, an equivalent amount of CSF should be complementarily delivered from another location. Our data suggests that the most likely candidate is VCSF extracted through the foramina of Magendie & Luchka by an artificially created negative pressure in the spinal subarachnoid space. High concentration of tau and low concentrations of Aβ and LRG in the VCSF are therefore reflected in the LD concentration. Thus, LD rather than FD reflects the true brain condition and the rostrocaudal gradient (Fig. 4).

Fig.4.

Schematic depiction of presumed CSF flow and tau passage during the tap test. Spinal tap releases a flow of CSF from ventricles to spinal subarachnoid space. In consequence, high concentration of tau in VCSF is reflected in the Last Drip.

It is interesting that tau concentrations were elevated while the concentrations of other biomarkers were decreased in the LD and VCSF. One hypothesis is that biomarker concentrations in the VCSF are affected by the brain area in which each protein is secreted. Tau pathology is known to begin in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, which directly contacts the ventricular space. Decreased CSF circulation may also stagnate tau in the VCSF in iNPH, enhancing the VCSF-LCSF concentration difference.

In contrast, Aβ is secreted synaptically at the cortex and removed via recently known glymphatic system; brain-wide paravascular pathway for CSF and interstitial fluid [9]. Thus, Aβ might be at high concentration in the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain but not in VCSF. LRG is also primarily localized in the cerebral cortex [10], which may explain its low concentration in VCSF. In patients with iNPH, the concentrations of Aβ and LRG were decreased in LD when decreased CSF circulation was transiently improved by a tap test, also reflecting the VCSF concentration.

The function of LRG in the brain has not yet been fully investigated, but it is now considered to be one of the causes of the dementia associated with neurodegenerative disease [11] and our data may reflect this aspect to some extent. Patients with higher concentrations of LRG in LD had a poorer cognitive function response following shunt surgery.

The CSF concentrations of tau were inversely correlated to tap test response, particularly gait ability, in accordance with our previous report [3]. In the present study, this tendency was more apparent in the tau concentrations obtained from LD than FD, and tau in LD had a higher correlation with post-shunt iNPHGS relative to pre-shunt iNPHGS. Post-shunt iNPHGS may reflect the original ability potential with relieved iNPH pathophysiology. In this study, LD tau concentrations were best correlated with post-shunt iNPHGS and could indicate that tau concentrations in LD are associated with the patients’ latent tau pathology.

A similar study was recently performed by another group [12]. They compared the CSF in the first 5 ml (0–5 ml) and last 5 ml (35–40 ml) as drained by a tap test with a total amount of 40 ml. They did not detect significant changes between the two samples, although their results had same tendency toward an increase in tau and decrease of Aβ. That study included a limited number of patients (n = 16). In the present study, both FD and LD were limited to 1 ml (0–1 ml and 29–30 ml, respectively) of the CSF taken during the tap test. While this may restrict a number of biomarker assays, we recommend acquiring CSF in separate and limited 1 ml samples of FD and LD to detect subtle differences.

A few patients in this study had a smaller change ratio between FD and LD or between LCSF and VCSF. A previous study evaluated the VCSF/LCSF ratio for these biomarkers in iNPH and post-traumatic hydrocephalus and found a significant VCSF/LCSF ratio in iNPH only [13]. It is therefore possible that the minority of patients with a smaller dynamic change could have subclinical secondary hydrocephalic pathology. These patients could also be influenced by CSF flow disturbance due to spinal stenosis, which is difficult to quantify and requires additional data. Another major limitation of this study is the lack of a control group. We assumed that in AD patients without concurrent iNPH, difference of LD/FD is much smaller due to CSF flow which continuously stirs up CSF contents. However, it was ethically difficult to take 30 ml of CSF from healthy or disease control participants such as AD given the risks of post-lumbar puncture headache and subdural hemorrhage. Consequently, we could not conclude that LD/FD difference is specific for iNPH.

This is the first study observing the dynamic changes in CSF biomarkers during the tap test and reveals the link between LD and VCSF. Most prior research into CSF biomarkers has been one-point CSF observation. Therefore, the prediction of surgical outcomes remains challenging, even with the use of several biomarkers [14]. The tap test is a routine procedure for potential iNPH patients, therefore two-point CSF collection is easily obtainable. CSF biomarker studies in iNPH are still relatively new, and this dynamic CSF biomarker observational method could reveal the iNPH pathological background and elucidate the physiology of impaired CSF circulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Ms. Kaori Iida, Shizuoka City Shizuoka Hospital, for illustrating the schema. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17H06808 and JP18K15448.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-0775r1).

REFERENCES

- [1]. Adams RD, Fisher CM, Hakim S, Ojemann RG, Sweet WH (1965) Symptomatic occult hydrocephalus with “normal” cerebrospinal-fluid pressure. A treatable syndrome. N Engl J Med 273, 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Cabral D, Beach TG, Vedders L, Sue LI, Jacobson S, Myers K, Sabbagh MN (2011) Frequency of Alzheimer’s disease pathology at autopsy in patients with clinical normal pressure hydrocephalus. Alzheimers Dement 7, 509–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Jingami N, Asada-Utsugi M, Uemura K, Noto R, Takahashi M, Ozaki A, Kihara T, Kageyama T, Takahashi R, Shimohama S, Kinoshita A (2015) Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus has a different cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profile from Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 45, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Jeppsson A, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Wikkelso C (2013) Idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus: Pathophysiology and diagnosis by CSF biomarkers. Neurology 80, 1385–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Williams MA, Malm J (2016) Diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 22, 579–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Tarnaris A, Toma AK, Chapman MD, Petzold A, Kitchen ND, Keir G, Watkins LD (2009) The longitudinal profile of CSF markers during external lumbar drainage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80, 1130–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Mori E, Ishikawa M, Kato T, Kazui H, Miyake H, Miyajima M, Nakajima M, Hashimoto M, Kuriyama N, Tokuda T, Ishii K, Kaijima M, Hirata Y, Saito M, Arai H, Japanese Society of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (2012) Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: Second edition. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 52, 775–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Kubo Y, Kazui H, Yoshida T, Kito Y, Kimura N, Tokunaga H, Ogino A, Miyake H, Ishikawa M, Takeda M (2008) Validation of grading scale for evaluating symptoms of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H (2013) Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest 123, 1299–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Nakajima M, Miyajima M, Ogino I, Watanabe M, Hagiwara Y, Segawa T, Kobayashi K, Arai H (2012) Brain localization of leucine-rich alpha2-glycoprotein and its role. Acta Neurochir Suppl 113, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Miyajima M, Nakajima M, Motoi Y, Moriya M, Sugano H, Ogino I, Nakamura E, Tada N, Kunichika M, Arai H (2013) Leucine-rich alpha2-glycoprotein is a novel biomarker of neurodegenerative disease in human cerebrospinal fluid and causes neurodegeneration in mouse cerebral cortex. PLoS One 8, e74453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Djukic M, Spreer A, Lange P, Bunkowski S, Wiltfang J, Nau R (2016) Small cisterno-lumbar gradient of phosphorylated Tau protein in geriatric patients with suspected normal pressure hydrocephalus. Fluids Barriers CNS 13, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Brandner S, Thaler C, Lelental N, Buchfelder M, Kleindienst A, Maler JM, Kornhuber J, Lewczuk P (2014) Ventricular and lumbar cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus and posttraumatic hydrocephalus. J Alzheimers Dis 41, 1057–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Graff-Radford NR (2014) Alzheimer CSF biomarkers may be misleading in normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurology 83, 1573–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]