Abstract

Background:

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the costliest diseases in the United States.

Objective:

To describe aspects of real-world patient and caregiver burden in patients with clinician-diagnosed early AD, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild dementia (MILD) due to AD.

Methods:

Cross-sectional assessment of GERAS-US, a 36-month cohort study of patients seeking care for early AD. Eligible patients were categorized based on study-defined categories of MCI and MILD and by amyloid positivity [+] or negativity [–] within each severity cohort. Demographic characteristics, health-related outcomes, medical history, and caregiver burden by amyloid status are described.

Results:

Of 1,198 patients with clinician-diagnosed early AD, 52% were amyloid[+]. For patients in both cohorts, amyloid[–] was more likely to occur in those with: delayed time to an AD-related diagnosis, higher rates of depression, poorer Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia scores, and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (all p < 0.05). MILD[–] patients (versus MILD[+]) were more medically complex with greater rates of depression (55.7% versus 40.4%), sleep disorders (34.3% versus 26.5%), and obstructive pulmonary disease (11.8% versus 6.6%); and higher caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview) (all p < 0.05). MILD[+] patients had lower function according to the Functional Activities Questionnaire (p < 0.001), yet self-assessment of cognitive complaints across multiple measures did not differ by amyloid status in either severity cohort.

Conclusions:

Considerable patient and caregiver burden was observed in patients seeking care for memory concerns. Different patterns emerged when both disease severity and amyloid status were evaluated underscoring the need for further diagnostic assessment and care for patients.

Study Registry:

H8A-US-B004; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02951598.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid, burden of illness, florbetapir F18, mild Alzheimer’s dementia, mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic, degenerative brain disorder, clinically affecting an estimated 5.4 million Americans [1]. Early symptomatic AD henceforth referred to as early AD, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild dementia (MILD), is characterized by a decline in a person’s ability to remember, reason, and learn, leading to permanent cognitive disability in the moderate to severe stages of the illness [2]. As AD progresses, impairments of activities of daily living lead to decreased quality of life (QoL) and increased morbidity and mortality [1] as well as escalated caregiver burden and stress [3]. Health-related and economic outcomes tended to worsen as the disease progressed according to GERAS-I, an observational study of patients with mild, moderate, and moderately/severe AD conducted in Europe [4]. GERAS-I addressed many questions regarding the consequences associated with disease progression but excluded patients with the early stages of AD.

The burden of the early stages of AD including cognitive impairment, effects on daily functioning, social/family care, and economic costs has been studied but is inadequately described [5–7] in large part due to the underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of early AD. Refinements in diagnostic criteria and advancements in biomarker modalities have improved the classification and study of early AD. Detection of biomarkers now allow for premortem identification of the presence of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [8, 9] via cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and positron emission tomography (PET) amyloid imaging [10, 11]. A negative Aβ PET scan indicates no or sparse amyloid neuritic plaques on pathology and is therefore inconsistent with a diagnosis of AD. In contrast, a positive Aβ PET scan indicates moderate to frequent amyloid neuritic plaques, which is more consistent with an AD diagnosis within the context of a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

The current study, GERAS-US (H8A-US-B004; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02951598), was designed to longitudinally address gaps and expand knowledge from GERAS-I to include patients with clinician-diagnosed early AD in real-world clinical practice. Specifically, this study investigated patients who were being seen in the United States (US) by practicing physicians and assessed the health-related and economic burden associated with clinician-diagnosed early AD.

The aim of this manuscript is to describe the study design and baseline clinical burden for participants; diagnostic criteria were applied to categorize patients by severity and amyloid status to better describe burden of early AD.

METHODS

Study design

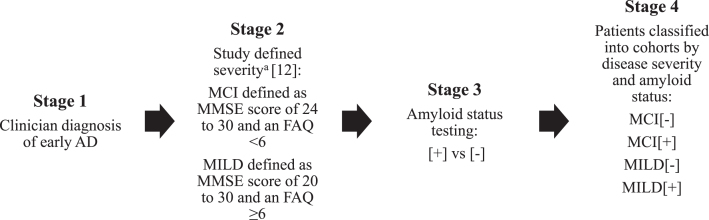

This cross-sectional assessment uses baseline data from GERAS-US, a 36-month US-based, prospective cohort study of patients with clinician-diagnosed early AD seeking routine care for memory concerns. To better characterize patients and determine burden, while maintaining real-world practice, measures of cognition, function, and amyloid status were applied to the study population in a 4-stage approach (Fig. 1). Patients were identified by their physician for whom they were seeing for memory concerns and invited to participate in the study. The first stage identified patients with clinician-diagnosed early AD based upon the clinical judgment/diagnosis of their physician. During stage 2, uniform diagnostic criteria were applied to classify patients as either MCI (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score of 24 to 30 and a Functional Activities Questionnaire [FAQ] <6) or MILD (mild dementia, MMSE score of 20 to 30 and an FAQ ≥6) [12]. Patients falling outside of these ranges were classified as MCI or MILD based on their current clinician-reported diagnosis. If patients were missing a diagnosis, they were excluded from the analyses. During stage 3, the study population was further defined following amyloid testing (amyloid status positive [+] or negative [–]). Stage 4 categorized patients into 4 cohorts by amyloid status within AD severity cohorts (MCI and MILD).

Fig.1.

Four-Stage Approach of Study Disease Classification. aPatients falling outside of these ranges were classified as MCI or MILD based on their current clinician-reported diagnosis. If patients were missing a diagnosis they were excluded from the analyses. FAQ, Functional Activities Questionnaire; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MILD, mild dementia; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; [+], amyloid positive; [–], amyloid negative.

Site selection

Sites (n = 77) were chosen to be reflective of physicians in clinical practice rather than clinical trial settings. One site (n = 50 patients) was withdrawn from enrollment due to quality or compliance findings prior to amyloid testing. These patients were considered screen failures due to lack of evidence of disease. The 76 remaining sites were geographically diverse including 20 states in rural, suburban, and urban settings (1.1%, 45.1%, and 53.8%, respectively) from outpatient practices of neurology (35.1%), psychiatry (23.0%), and family/general practice (14.9%). Some sites had been involved in interventional clinical trials as well as observational research. Sites were further selected based on the number of reported patients seen per month with AD, experience with cognitive testing, and proximity to an imaging center that provided amyloid PET imaging using florbetapir. All sites completed Good Clinical Practice training prior to enrolling participants. Physicians received compensation for their time spent on study-related tasks.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by either a central or a site-specific institutional review board. The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. All participants or their legal designees provided written informed consent before baseline assessments.

Participant selection

Participants were enrolled from October 30, 2016, through October 9, 2017. Eligible patients were between the ages of 55 and 85 years, met criteria for early AD in the opinion of the enrolling physician, had MMSE scores ≥20, had study partners who were willing to participate, and were able to communicate in English or Spanish. Patients were excluded if they were unable to undergo amyloid testing, had prior (within last 2 years) CSF or amyloid PET with amyloid[–] results, were participating in another clinical trial for an investigational drug, or were employees or family members of personnel affiliated with the study.

To increase the likelihood of studying individuals with early AD, patients were required to undergo an Aβ PET scan as part of the study. Florbetapir PET scan was performed if historical evidence of amyloid pathology was unavailable. Because the proportion of patients who are amyloid[+] is unknown in routine clinical practice, this cross-sectional analysis included all patients regardless of amyloid status, but only patients identified as amyloid[+] will continue in the longitudinal portion of this study.

Participants were invited to participate in an addendum that enabled the linkage of study data to insurance claims data to further characterize costs of care. Participants were compensated for their time and travel as part of the study.

Assessments

Physicians collected the patient’s and study partner’s demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) and medical history including the presence and treatment of potential comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, ischemic heart disease, depression, epilepsy, seizures due to conditions other than epilepsy, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke, urinary tract disorder, sleep disorders, and obstructive pulmonary disease). The patient’s experience with AD such as time since symptom onset, family history of AD, use of AD treatments, interactions with emergency services, and occurrence of accidental falls was also collected.

Most assessments were collected using standardized outcome measures from the clinician, patient, or study partner perspective including cognition [13, 14], function [15, 16], neuropsychiatric symptoms [17], QoL/study partner burden [18–21], and healthcare resource utilization/caregiver time [22] (Table 1). These measures and any changes to living status will also be collected post-baseline for continuing patients and analyzed at a later date.

Table 1.

Outcome assessments and source of inquiry

| Outcome Assessments | Source of Data | Measures | |

| Cognition | Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [13] | Investigator rated interview with patient | •Assessed via orientation, memory, and attention |

| •Patients are tested on their ability to name objects, follow verbal and written commands, write a sentence, and copy figures | |||

| •Range: 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better cognition | |||

| Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog-13) [14] | Investigator rated interview with the patient | •Assessed via orientation, verbal memory, language, and praxis, delayed free recall, digit cancellation, and maze completion | |

| •Range: 0 to 85, with higher scores indicating greater disease severity | |||

| Function | Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) [15] | Investigator interview with study partner of the patient’s functioning | •Assessed by ability to complete complex ADLs that may be impaired in early stage AD (e.g., ability to shop, cook, and pay bills) |

| •Range: 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater impairment | |||

| Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) [16] | Two versions were used: 1) Study partner rated version and 2) patient rated version via investigator interview | •Assessed patients’ perspective of their ability to perform high level tasks in daily-life and overall cognitive functional ability | |

| •Study partner version also includes changes over 1 year and concern of those changes | |||

| •Ranges: 20 to 100 (study partner version) and 0 to 15 (patient version), with higher scores indicating poorer status | |||

| Psychopathology | Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [17] | Investigator interview with study partner describing patient | •Assessed the presence, frequency, and severity of delusions, hallucinations, agitation, apathy, anxiety, depression, euphoria, irritability, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behavior; and two questions inquire about neurovegetative changes (appetite and nighttime behavior disturbances) |

| •Range: total 0 to 144, with lower scores indicating poorer status | |||

| Healthcare resource utilization and caregiver time | Resource Utilization in Dementia Questionnaire (RUD Version 4.0) [22] | RUD administered by the investigator to the study partner describing patient and study partner information | •Questions of patient and study partner work status and use of hospital services, emergency department, outpatient, and prescription drug use |

| •Caregiving time includes time spent assisting patients’ basic ADLs such as using toilet, eating, dressing, grooming, walking, and bathing; assisting patients’ instrumental activities of daily living such as shopping, cooking, housekeeping, laundry, transportation, taking medication, and managing finances; and providing supervision | |||

| •Used for calculating costs | |||

| Quality of Life (QoL)/Caregiver Burden | Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia (BASQID) [18] | Investigator interview with the patient | •Assessed subjective QoL in dementia using a total scale and two subscales: life satisfaction and feelings of positive QoL |

| •Three additional questions (G1, G2, and G3) are included to provide global subjective ratings of QoL, health, and memory | |||

| •Range (total score): 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating poorer status | |||

| Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) [19] | Study partner completed questionnaire | •Caregiver burden in terms of stress, time for self and impact of caring on caregivers’ social life | |

| •Range: 0 to 88, with higher scores indicating greater burden | |||

| Desire to Institutionalize Scale (DTI) [20, 21] | Study partner completed | •Assessed whether study partner has considered, discussed, or taken steps toward moving patient to another living arrangement via six questions | |

| •Range: 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating greater desire to institutionalize |

Sample size

Sample size targets for the study were determined based on the longitudinal portion of this study for which the primary objective is to determine the changes in total societal costs over 36 months. In order to obtain an approximate 95% confidence interval of ±10% of the mean cost estimate, the aim was to enroll 700 amyloid[+] patients (350 per severity cohort) so that approximately 420 patients would provide data at 36 months. The sample size was calculated assuming that costs would be exponentially distributed, that discontinuation rates would be similar to those of the GERAS-I study mild AD dementia cohort (40% discontinuation by 36 months [23]), and that severity cohorts and amyloid status would be equally represented. The sample size calculation was based on the asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimate of the mean of the exponential distribution and used the fact that the mean and standard deviation (SD) are equal for an exponential random variable.

Statistical analysis

The baseline analysis was descriptive in nature to understand the population and clinical characteristics of illness. Data are summarized as the number of patients and percentages for categorical variables and means±SD for continuous variables. The primary comparisons were conducted for difference between amyloid status: MCI cohort (MCI[+] versus MCI[–]) and MILD cohort (MILD[+] versus MILD[–]). Additional comparisons were conducted for difference between severity cohorts (MCI versus MILD) and between amyloid status cohorts ([+] versus [–]) (data not shown). All comparisons evaluated were pre-specified; no comparisons evaluated were for effects suggested solely by the data. Continuous baseline characteristics were compared using t-tests and categorical variables compared using chi-square statistics. The size of the resulting p-value was taken as an index of how different the cohorts may be, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The study was not powered based on comparisons for baseline variables, and the clinical relevance of the size of the difference was taken into consideration in evaluating the results of the analyses. No adjustments were made for multiplicity in cohort comparisons or for the number of variables assessed. A Spearman correlation was calculated for the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI)-patient and CFI-study partner assessment of concordance. All analyses used SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.12 (Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Patient disposition

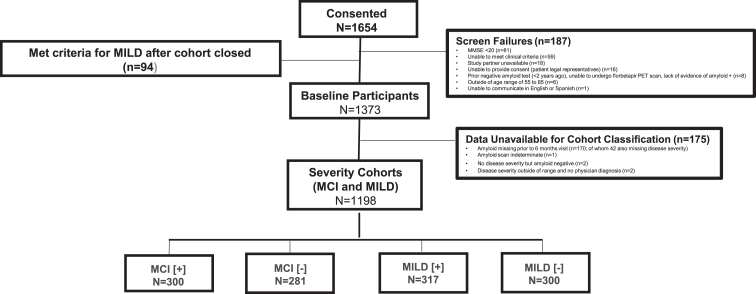

GERAS-US was composed of 1,654 consenting patient-study partner dyads (Fig. 2). A total of 187 patients were screen failures, and 94 patients consented after the MILD cohort closed and therefore were not included. Of the 1,373 participants, 175 patients could not be classified for the following reasons: amyloid missing prior to the 6-month visit (n = 170, of whom 42 were also missing severity); amyloid scan indeterminate (n = 1); no disease severity but amyloid[–] (n = 2); and severity outside of the pre-specified range and no physician diagnosis (n = 2). The evaluable population included 1,198 patients (MCI[+] = 300, MCI[–] = 281, MILD[+] = 317, and MILD[–] = 300).

Fig.2.

Patient Attrition at Baseline. MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MILD, mild dementia; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; PET, positron emission tomography; +, amyloid positive; –, amyloid negative.

Demographic characteristics

Overall, patients had a mean age of 70.4 years, slight preponderance of females (55.3%), and were mostly self-identified as Caucasian (87.0%). Patients had a similar mean age, gender, and race regardless of amyloid status within each severity cohort (Table 2). Notably, a higher than expected proportion of patients were of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (39.2%) with a higher proportion of Hispanic/Latino patients with amyloid[–] status in each severity cohort (both p < 0.001) and with the highest rate reported for the MILD[–] cohort (58.7%).

Table 2.

Patient and study partner demographic characteristics across cohorts*

| Description | Overall | MCI[+] | MCI[–] | p† | MILD[+] | MILD[–] | p† |

| N = 1198 | N = 300 | N = 281 | N = 317 | N = 300 | |||

| Patient | |||||||

| Age, mean (SD) y | 70.4 (7.7) | 70.3 (7.4) | 69.3 (7.7) | 0.092 | 71.7 (8.0) | 69.9 (7.4) | 0.004 |

| Age >65 y, n (%) | 891 (74.4) | 224 (74.7) | 199 (70.8) | 0.298 | 245 (77.3) | 223 (74.3) | 0.392 |

| Gender, n (%) female | 663 (55.3) | 158 (52.7) | 160 (56.9) | 0.301 | 167 (52.7) | 178 (59.3) | 0.096 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.019 | 0.447 | |||||

| White | 1042 (87.0) | 259 (86.3) | 249 (88.6) | 279 (88.0) | 255 (85.0) | ||

| Black | 116 (9.7) | 33 (11.0) | 17 (6.0) | 30 (9.5) | 36 (12.0) | ||

| Asian | 27 (2.3) | 5 (1.7) | 14 (5.0) | 5 (1.6) | 3 (1.0) | ||

| Other | 13 (1.1) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.9) | 6 (2.0) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) Hispanic or Latino | 470 (39.2) | 62 (20.7) | 95 (33.8) | <0.001 | 137 (43.2) | 176 (58.7) | <0.001 |

| Study Partner | |||||||

| Age, mean (SD) y | 58.6 (15.2) | 59.7 (15.9) | 59.7 (14.4) | 0.958 | 59.3 (14.9) | 55.8 (15.2) | 0.004 |

| Age >65 y, n (%) | 503 (42.0) | 144 (48.0) | 126 (44.8) | 0.445 | 131 (41.3) | 102 (34.0) | 0.061 |

| Gender, n (%) female | 782 (65.3) | 187 (62.3) | 174 (61.9) | 0.919 | 226 (71.3) | 195 (65.0) | 0.093 |

| Number of caregivers in addition to study partner | 0.741 | 0.119 | |||||

| 0 | 735 (61.4) | 212 (70.7) | 199 (70.8) | 179 (56.5) | 145 (48.3) | ||

| 1 | 325 (27.1) | 67 (22.3) | 58 (20.6) | 99 (31.2) | 101 (33.7) | ||

| 2 | 94 (7.8) | 14 (4.7) | 14 (5.0) | 25 (7.9) | 41 (13.7) | ||

| 3 | 30 (2.5) | 4 (1.3) | 8 (2.8) | 10 (3.2) | 8 (2.7) | ||

| 4+ | 14 (1.2) | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.3) | 5 (1.7) | ||

| Study partner is a spouse, n (%) | 501 (41.8) | 144 (48.0) | 121 (43.1) | 0.174 | 134 (42.3) | 102 (34.0) | 0.231 |

| Resides with patient, n (%) | 822 (68.6) | 196 (65.3) | 181 (64.4) | 0.816 | 227 (71.6) | 218 (72.7) | 0.770 |

MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MILD, mild dementia; SD, standard deviation; +, amyloid positive; –, amyloid negative. *Percentages are based on the number of respondents available per item. †p-values were computed for continuous versus categorical data from t-test or chi-square test, respectively.

Study partners on average were younger than patients with a mean age of 58.6 years and nearly two-thirds were female (65.3%) (Table 2). Most study partners resided with the patient (68.6%) and were the sole caregiver (61.4%), yet less than half were the patients’ spouse (41.8%).

Clinical characteristics

Overall, the mean time since AD-related diagnosis was 1.5±2.2 years and with mean time since first symptoms of 3.2±2.9 years (Table 3). Approximately 27% (324/1198) of patients had a first degree relative with AD. Interactions with police, fire, or ambulance services over the last 3 months were very low (1.5%). Accidental falls over the last 3 months were reported in 10.1% of patients including an average of 2.1 falls per patient among those who fell. Amyloid[–] patients had a delayed time before they received a diagnosis related to early AD in both severity cohorts (both p < 0.01) and a longer time until recognition of first symptoms only in the MCI cohort (p = 0.002).

Table 3.

Patient clinical characteristics and comorbidities across cohorts*

| Description | Overall | MCI[+] | MCI[–] | p† | MILD[+] | MILD[–] | p† |

| N = 1198 | N = 300 | N = 281 | N = 317 | N = 300 | |||

| Time since AD-related diagnosis, mean (SD) y | 1.5 (2.2) | 1.0 (1.3) | 1.5 (2.0) | 0.003 | 1.5 (2.3) | 2.1 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Time since first symptoms, mean (SD) y | 3.2 (2.9) | 2.7 (2.4) | 3.5 (3.1) | 0.002 | 3.2 (3.1) | 3.5 (2.8) | 0.208 |

| First degree relative with AD, n (%) | 324 (27.1) | 82 (27.6) | 97 (34.5) | 0.131 | 68 (21.5) | 77 (25.7) | 0.057 |

| Interactions with police, fire, or ambulance services due to cognitive symptoms over last 3 months, n (%) | 18 (1.5) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.402 | 7 (2.2) | 7 (2.3) | 0.864 |

| Accidental falls over last 3 months, n (%) | 120 (10.1) | 24 (8.0) | 18 (6.4) | 0.329 | 46 (14.6) | 32 (10.7) | 0.357 |

| Number of falls, mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.7) | 0.544 | 2.2 (1.9) | 2.6 (2.3) | 0.395 |

| Any comorbidity, n (%)‡ | 1051 (87.7) | 263 (87.7) | 245 (87.2) | 0.984 | 272 (85.8) | 271 (90.3) | 0.073 |

| Number of comorbidities, mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.3 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.538 | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.8 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 723 (68.8) | 191 (72.6) | 152 (62.0) | 0.011 | 191 (70.2) | 189 (69.7) | 0.903 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 513 (48.8) | 132 (50.2) | 114 (46.5) | 0.410 | 128 (47.1) | 139 (51.3) | 0.324 |

| Depression, n (%) | 467 (44.4) | 94 (35.7) | 112 (45.7) | 0.022 | 110 (40.4) | 151 (55.7) | <0.001 |

| Sleep disorders, n (%) | 290 (27.6) | 57 (21.7) | 68 (27.8) | 0.112 | 72 (26.5) | 93 (34.3) | 0.047 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 301 (28.6) | 76 (28.9) | 61 (24.9) | 0.310 | 72 (26.5) | 92 (33.9) | 0.058 |

| Obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 78 (7.4) | 11 (4.2) | 17 (6.9) | 0.174 | 18 (6.6) | 32 (11.8) | 0.036 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 111 (10.6) | 28 (10.6) | 15 (6.1) | 0.067 | 34 (12.5) | 34 (12.5) | 0.987 |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MILD, mild dementia; SD, standard deviation; +, amyloid positive; –, amyloid negative. *Percentages are based on the number of respondents. †p-values were computed for continuous versus categorical data from t-test or chi-squared test, respectively. ‡12 comorbidities interrelated to AD were evaluated.

Comorbidities

Most patients had at least 1 physician-reported current comorbid condition (87.7%) with an overall mean number of 2.4±1.8 comorbidities present during the baseline visit (Table 3). Hypertension was the most common (68.8%) followed by hypercholesterolemia (48.8%), depression (44.4%), diabetes mellitus (28.6%), and sleep disorders (27.6%). Amyloid[–] patients had significantly greater rates of depression in both severity cohorts; furthermore, the most marked differences among amyloid[–] patients were within the MILD cohort. Patients categorized as MILD[–] were more medically complex with a significantly higher number of comorbidities (2.8±2.2) versus the MILD[+] cohort (2.3±1.7; p < 0.001). Specifically, MILD[–] patients versus MILD[+] patients reported significantly higher rates of depression (55.7% versus 40.4%; p < 0.001), and sleep disorders (34.3% versus 26.5%; p = 0.047).

Outcome measures

When comparing the effect of amyloid status within each severity cohort, study partners saw significantly worse changes in patients compared to a year ago (CFI-study partner change score) among MCI[–] versus MCI[+] patients and among MILD[+] versus MILD[–] patients (p = 0.043 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 4). No other measures were significantly different among MCI[+] versus MCI[–]. MILD[+] (versus MILD[–]) also tended to have lower function across the clinician-administered FAQ (p < 0.001) and study partner perceived overall function (CFI total; p = 0.011) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Baseline health-related outcome measures across cohorts, mean (SD)*

| Description | Range | Overall | MCI[+] | MCI[–] | p§ | MILD[+] | MILD[–] | p§ |

| N = 1198 | N = 300 | N = 281 | N = 317 | N = 300 | ||||

| MMSE | 0–30↓† | 26.0 (2.8) | 27.4 (1.8) | 27.6 (1.9) | 0.235 | 24.4 (2.8) | 24.8 (2.8) | 0.052 |

| ADAS-Cog-13 | 0–85↑‡ | 22.0 (10.1) | 16.6 (7.5) | 17.2 (8.5) | 0.428 | 27.3 (10.0) | 26.6 (9.0) | 0.269 |

| FAQ | 0–30↑‡ | 8.7 (7.6) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.971 | 15.6 (6.4) | 13.8 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| CFI-patient, total | 0–15↑‡ | 5.8 (3.8) | 4.5 (3.2) | 4.5 (3.1) | 0.972 | 7.6 (3.9) | 8.3 (3.8) | 0.200 |

| CFI-study partner, total | 20–100↑‡ | 54.6 (15.2) | 47.0 (14.0) | 45.8 (13.1) | 0.241 | 63.7 (13.4) | 61.0 (11.0) | 0.011 |

| Change subscale | 20–100↑‡ | 69.1 (9.3) | 65.1 (8.9) | 66.6 (7.3) | 0.043 | 73.2 (10.3) | 70.8 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Concern subscale | 20–100↑‡ | 55.6 (20.9) | 48.8 (22.1) | 46.1 (19.8) | 0.315 | 60.7 (19.6) | 64.9 (15.4) | 0.092 |

| Spearman correlation coefficient between patient and partner | 0.540 | 0.508 | 0.366 | 0.413 | 0.319 | |||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | ||||

| NPI, total | 0–144↓† | 6.9 (10.4) | 4.9 (9.0) | 4.3 (6.8) | 0.454 | 8.9 (11.7) | 9.2 (12.1) | 0.721 |

| BASQID, total | 0–100↓† | 54.6 (20.7) | 64.7 (18.5) | 60.8 (19.9) | 0.014 | 49.8 (19.2) | 43.6 (18.2) | <0.001 |

| BASQID, life satisfaction | 0–100↓† | 50.8 (20.4) | 59.7 (19.3) | 56.3 (20.3) | 0.032 | 46.7 (18.7) | 40.8 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| BASQID, feelings of positive quality of life | 0–100↓† | 58.7 (23.1) | 70.3 (19.7) | 65.9 (21.4) | 0.012 | 53.0 (22.1) | 46.4 (21.0) | <0.001 |

| Zarit Burden Inventory | 0–88↑‡ | 17.5 (14.9) | 12.4 (13.4) | 12.2 (12.8) | 0.857 | 20.8 (14.9) | 24.1 (14.5) | 0.004 |

| Desire to Institutionalize | 0–6↑‡ | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.749 | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.028 |

| Individual items, yes n (%) | ||||||||

| Considering | 61 (5.1) | 6 (2.0) | 7 (2.5) | 0.689 | 28 (8.9) | 20 (6.7) | 0.316 | |

| Felt better off | 62 (5.2) | 10 (3.3) | 9 (3.2) | 0.930 | 24 (7.6) | 19 (6.4) | 0.547 | |

| Discussed with family | 106 (8.9) | 15 (5.0) | 16 (5.7) | 0.709 | 48 (15.2) | 27 (9.0) | 0.020 | |

| Discussed with patient | 90 (7.5) | 18 (6.0) | 15 (5.4) | 0.731 | 39 (12.3) | 18 (6.0) | 0.007 | |

| Taken step towards placement | 24 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.4) | 0.155 | 11 (3.5) | 8 (2.7) | 0.564 | |

| Likely to move patient | 36 (3.0) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.8) | 0.219 | 16 (5.1) | 13 (4.3) | 0.676 |

ADAS-Cog13, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive subscale; BASQID, Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia; CFI, Cognitive Function Instrument; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MILD, mild dementia; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; SD, standard deviation; +, amyloid positive; –, amyloid negative. *All percentages are based on the number of respondents. †Lower scores equal poorer status ↓. ‡Higher scores equal poorer status ↑. §p-values were computed for continuous versus categorical data from t-test or chi-squared test, respectively.

Amyloid[–] patients in both severity cohorts had poorer subjective QoL as measured by the Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia (BASQID) total score, its subscales of life satisfaction and feeling positive QoL (Table 4), as well as the additional global patient rating of QoL item (all p < 0.05 for MCI[+] versus MCI[–] comparisons; all p < 0.01 for MILD[+] versus MILD[–] comparisons) (Table 5). Furthermore, MILD[–] patients also reported a poorer QoL in terms of poorer health and poorer memory as measured by BASQID items versus MILD[+] patients (all p≤0.005) (Table 5) as well as higher caregiver burden based on Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) (p = 0.004) (Table 4). MILD[+] patients were associated with a higher desire to institutionalize from the study partner’s perspective versus MILD[–] patients (p = 0.028) (Table 4). Interpretation of the desire to institutionalize measure was based on six items addressing attitudes toward institutionalization. Although very few study partners were considering institutionalization (5.1%), drivers of significant changes for the MILD[+] cohort may be the percentage of study partners that are discussing institutionalization with family members (MILD[+] 15.2% versus MILD[–] 9.0%; p = 0.020) as well as discussions that study partners are having with patients (MILD[+] 12.3% versus MILD[–] 6.0%; p = 0.007) (Table 4).

Table 5.

BASQID qualitative outcome measures across cohorts*

| Description | Overall | MCI[+] | MCI[–] | p* | MILD[+] | MILD[–] | p* |

| N = 1198 | N = 300 | N = 281 | N = 317 | N = 300 | |||

| How would you rate your QoL?, n (%) | 0.014 | 0.004 | |||||

| Very poor | 16 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (1.9) | 8 (2.7) | ||

| Poor | 139 (11.6) | 24 (8.0) | 37 (13.2) | 28 (8.9) | 50 (16.7) | ||

| Fair | 287 (24.0) | 43 (14.3) | 62 (22.1) | 85 (26.9) | 97 (32.4) | ||

| Good | 381 (31.9) | 124 (41.3) | 90 (32.0) | 93 (29.4) | 74 (24.7) | ||

| Very good | 373 (31.2) | 108 (36.0) | 91 (32.4) | 104 (32.9) | 70 (23.4) | ||

| How would you rate your health?, n (%) | 0.351 | <0.001 | |||||

| Very poor | 33 (2.8) | 5 (1.7) | 3 (1.1) | 11 (3.5) | 14 (4.7) | ||

| Poor | 260 (21.7) | 41 (13.7) | 52 (18.5) | 60 (19.0) | 107 (35.8) | ||

| Fair | 381 (31.9) | 101 (33.7) | 87 (31.0) | 108 (34.2) | 85 (28.4) | ||

| Good | 358 (29.9) | 108 (36.0) | 107 (38.1) | 90 (28.5) | 53 (17.7) | ||

| Very good | 164 (13.7) | 45 (15.0) | 32 (11.4) | 47 (14.9) | 40 (13.4) | ||

| How would you rate your memory, n (%) | 0.841 | 0.005 | |||||

| Very poor | 97 (8.1) | 15 (5.0) | 18 (6.4) | 28 (8.9) | 36 (12.0) | ||

| Poor | 378 (31.6) | 65 (21.7) | 66 (23.5) | 112 (35.4) | 135 (45.2) | ||

| Fair | 430 (36.0) | 124 (41.3) | 108 (38.4) | 122 (38.6) | 76 (25.4) | ||

| Good | 216 (18.1) | 82 (27.3) | 73 (26.0) | 34 (10.8) | 27 (9.0) | ||

| Very good | 75 (6.3) | 14 (4.7) | 16 (5.7) | 20 (6.3) | 25 (8.4) |

BASQID, Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MILD, mild dementia; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation; +, amyloid positive; –, amyloid negative. *All percentages are based on the number of respondents. †p-values were computed from chi-squared test.

Additional comparisons

All comparisons were replicated stratifying for either severity (MCI versus MILD) or amyloid status (+ versus –) without consideration for the other factor. Additional findings included the MILD cohort having worse outcomes across all measures when compared with MCI (all p < 0.001) and some individual items on the desire to institutionalize and BASQID scales (all p < 0.001). Amyloid[+] patients were more likely than amyloid[–] patients to have lower functioning scores (FAQ and CFI total-study partner; all p < 0.05) but better BASQID scores (all p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The baseline findings from GERAS-US provided a cross-sectional description of patients with clinician-diagnosed early AD, including MCI and mild dementia, which received amyloid PET imaging. Understanding key differences related to amyloid status may underscore areas for future investigation to predict the expected course of AD. Noteworthy differences included existing comorbid conditions, outcomes, and ethnicity.

Our study observed that approximately 50% of patients diagnosed with early AD were amyloid [–]. However, a surprising finding was the similar rates of amyloid[+] among patients within the MCI (51.6%) and MILD (51.4%) cohorts. Although to our knowledge, no other study addresses the rates of amyloid positivity in early stage AD, greater variability was identified across individual studies. Within clinical trials and after extensive inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied, amyloid[+] was reported in 38% to 42% of patients with MCI [24] and 75.8% of patients with MILD [25]. Additionally, the IDEAS study reported rates of amyloid positivity as 55.3% of patients with MCI and 70.1% for patients with dementia, although the rate for patients with MILD was not explicitly reported [26].

The MILD[–] cohort was more medically complex (compared to the MILD[+] cohort) with greater rates of physician-reported comorbidities: depression, sleep disorders, and obstructive pulmonary disease. Higher rates of depression were also identified in the MCI[–] versus MCI[+] cohort. The higher rates of comorbid conditions in the MILD[–] cohort may add to the difficulty in determining the precise cause of cognitive impairment, and other known causes/contributors of cognitive impairment may complicate the ability to conclusively make an AD diagnosis. Previous reports suggest that among vascular comorbidities, “mixed” dementia is common and is often (>42%) reported in the real-world population [27–29]. Medical management is paramount as comorbidities often play an important role in masking an AD diagnosis and tailored management provides the opportunity to address potentially manageable or reversible causes of cognitive impairment.

The relationship between health-related outcomes and amyloid status were more evident in the MILD cohort while little differentiation was found within the MCI cohort. MILD[+] patients had more functional impairment than MILD[–] patients according to the study partner-reported FAQ and the CFI-study partner total and change scores, yet self-assessment of cognitive function (CFI-patient) did not differ by amyloid status, suggesting that patients were less aware of these deficits. Similarly, differences between MILD[+] and MILD[–] cohorts were found when patients were asked to subjectively rate their memory on the single item of the BASQID. This discrepancy was observed despite both cohorts having a similar degree of cognitive impairment on objective measurement, suggesting that insight may differ by amyloid status or source of cognitive impairment. BASQID ratings (MILD[+] versus MILD[–], respectively) included “good” and “very good” (17.1% versus 17.4%), “fair” (38.6% versus 25.4%), and “poor” and “very poor” (44.3% versus 57.2%). Indeed, anosognosia, a deficit of self-awareness, may be cognitive domain specific, and further investigation is needed to understand the impact of structural and pathophysiological correlates of cognitive impairment on subsequent loss of insight [30]. Of clinical relevance, these data suggest that observations by a study partner may better represent the true degree of impairment on these domains, and this discrepancy highlights the need for historical corroboration when evaluating a patient with cognitive impairment.

In contrast, an amyloid[–] status for both severity cohorts was associated with worse patient-rated QoL across the BASQID’s total and subscales. These findings may reflect that while patients may be less aware of their cognitive deficits, they are still aware of their broader health-related QoL as indicated from the BASQID. Patients with an amyloid[–] status also had more comorbidities that may affect QoL. This observation suggests that such complaints by the patient need to be taken seriously. It also is consistent with Ready [31] who summarized that the patient’s perspective may be more reliable than those of caregivers and healthcare providers on select constructs related to AD. Our findings suggest that patients seeking care for cognitive impairment that is likely due to early AD are able to appropriately report their QoL and overall health but not their cognitive function, where changes may be more recognizable by study partners. Importantly, future reports of the longitudinal GERAS-US study will more clearly describe patient-rated QoL that will be limited to patients with an amyloid[+] status.

An amyloid[–] status for both severity cohorts was also associated with higher caregiver burden (ZBI), and although study partners were infrequently considering institutionalization for this clinician-diagnosed early AD population (5.5%), they did have significantly more discussions with families of MILD[+] patients (MILD[+] 15.2% versus MILD[–] 9.0%; p = 0.020), as well as the patients themselves (MILD[+] 12.3% versus MILD[–] 6.0%; p = 0.007). This finding acknowledges that while the two cohorts appear to have a similar overall clinical presentation when looking at total summary scores, differences in specific item/domain-level disabilities or impairments are driving some of the differences in perceived need for long-term care services. Patients with more comorbidities will also have more caregiver burden. There do appear to be some modest differences in functioning between the MILD[+] versus MILD[–] cohorts; perhaps these are on highly sensitive activities. These findings are less clear in additional analyses (not shown) that assessed amyloid status without consideration for disease severity and disease severity without consideration for amyloid status.

At the time our study commenced, it was appreciated that caregiver burden was substantial for patients with later stage AD including increased depression, more stress and greater fatigue, as well as financial burden and the need to alter their working situations (e.g., early retirement and reduction in work hours) [32]. Until recently, the degree of burden for caregivers was relatively unknown for patients with early AD. The considerable informal caregiver burden observed in our study, especially among patients in the MILD[–] cohort, provides new knowledge and corroborates the recent findings of Connors et al. [33]. In their 3-year observational study consisting of 185 patients with MCI and their caregivers of whom approximately three-quarters were spouses, 21.1% to 29.5% of caregivers reported a clinically significant level of burden [33]. This higher degree of caregiver burden was associated with the patients’ high level of neuropsychiatric symptoms, lower functional ability, and lack of driving ability, plus the need for change in the caregivers’ employment. Of note, nearly one-third of patients were diagnosed with dementia over the 3-year study period, which led to increased caregiver burden (–3.2 points on the ZBI scale). Accordingly, caregivers of patients with early AD need personal support and counseling to reduce high levels of stress and burden and to improve poor mental health symptoms.

The burden of AD and other related dementias is high among people of Hispanic ethnicity and is estimated to rise in the future [34]. Traditionally, Hispanic people have been underrepresented in clinical research, [35] yet ethnoracial differences have been recently reported to vary across ethnicities in terms of clinical presentation and progression, genetics, and neuropathologic deficits [36]. A noteworthy strength of GERAS-US was the representative enrollment of patients with Hispanic ethnicity (39.2%) for both severity cohorts. Enrollment of sites in GERAS-US was driven to be reflective of the US population and attempts were made to ensure all regions of the country were represented with the restriction that the site had to be located near an amyloid testing facility. The study population came from 20 states, yet over 80% of the study population came from states where the prevalence of Hispanics, based on 2010 US Census data, was over 20%. In addition, 37.7% came from California and Texas where the 2010 census rates were over 30% [37]. The higher-than-expected rate of amyloid negativity, however, may be an area for further exploration. Santos [36] stated, however, that amyloid status did not vary for Hispanics, yet other biomarkers such as tau may be present at different rates. Although rates of AD tend to be 1.5 times higher in patients with Hispanic ethnicity [1], the higher rate of amyloid[–] scans should be assessed further to understand if there are potential difficulties in assessing symptoms in this population or if other factors contributing to cognitive impairment such as differences in rates of comorbidities may confound these findings.

An important finding of this study was the observation that only about 52% of patients were amyloid[+] indicating that cognitive deficits, in some cases, may be attributable to etiologies other than AD such as vascular dementia or major depressive disorder. This rate is lower than those of several clinical trials where approximately 1 in 5 patients with probable AD or MCI due to AD were likely misdiagnosed [24, 38, 39]. This rate is consistent with another US-based observational study (Imaging Dementia –Evidence for Amyloid Scanning; IDEAS), which was designed as part of the Coverage with Evidence Development by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to assess the clinical usefulness of amyloid testing in patients with uncertain cause of cognitive issues [40]. Rates may differ as these observational studies capture real-world practice with less intensive clinical and research-oriented assessments, thus including diverse patient samples, whereas clinical trials use enrichment strategies to enroll homogenous study populations and utilize central readers to interpret amyloid PET images to enable testing of specific hypotheses. The findings of lower amyloid positivity rates may also be explained by the inherent variability associated with amyloid PET interpretation, especially in patients with early AD. This emphasizes the need for improving diagnostic accuracy with the addition of quantification analysis. It is important to emphasize that patients categorized as MCI[+] and MILD[+] represent a continuum of clinician-diagnosed early AD. In contrast, patients categorized as MCI[–] and MILD[–] are not likely to develop AD. Finally, amyloid status has many implications for caregivers and patients, who may worry about being labelled with AD, and could affect counseling and treatment, thus necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management of patients with cognitive impairment. Physicians should consider amyloid scanning for their patients in order to optimize patient care.

Overall, our study suggests that amyloid status carries important clinical implications. Perhaps, counterintuitively, amyloid[–] patients have greater health burden, increased number of comorbidities including depression, yet a lower rate of consideration for institutionalization. Physicians should search for alternative explanations of dementia in patients with negative amyloid scans. Early detection and confirmation of the causes of their cognitive deficits, some of which may be reversible, may aid patients and families by allowing them the opportunity to benefit from available treatments in a timely manner, plan for the future, develop relationships with care partners, and identify resource needs to manage the disease as it progresses [5]. Amyloid imaging did illuminate the differences in burden as it relates to cognitive deficits; however, unexpectedly, differences in other outcomes by amyloid imaging were not seen possibly due to the high rates of comorbid conditions in the amyloid[–] cohort.

There are some limitations to these findings. First, although geographically dispersed, patients are not nationally representative. Sites were restricted to those with access to imaging centers that administer amyloid scans. Second, several patients were unable to obtain a PET scan after completing the physician visit due to limited availability within imaging centers. These patients were excluded from these analyses. Despite this, other measures were robust with a low level of missing data using electronic data capture methods. Third, all diagnostic and testing procedures, including amyloid imaging, relied on real-world practice rather than strict study criteria or central readers to assess scans and may therefore vary significantly according to level of reader experience at a specific study site. Fourth, statistical comparisons are exploratory with no correction for multiplicity. Despite these limitations, the physicians who participated in this study represent a sample of those who treat early AD patients. There were no study-specific prescribed treatments or regimens specified in the protocol; thus, management of the patients was determined by the physician, caregiver, and patient, representing real-world practice. Outcomes described herein should reflect real-world distribution.

In summary, to our knowledge, GERAS-US is the only study to assess outcomes including burden of clinician-diagnosed early AD and amyloid status in a real-world setting of patients who were being treated by physicians. Thus, the findings from this study make it possible to address current gaps in the literature regarding the characteristics and burden of illness in patients with clinician-diagnosed early AD. Surprisingly, our study found little variability in the rates of amyloid negativity between patients diagnosed with MCI or MILD, suggesting that misdiagnosis of early AD occurred in about half of our study population. This finding could have implications for clinical practice, given the differences in clinical phenotypes seen and may be important for individualized treatment as well as health systems. Our work suggests that amyloid negativity may be more common among patients with multiple comorbidities, especially vascular comorbidities; indeterminate causes of cognitive impairment were common and led to poorer health-related outcomes and QoL; and amyloid[+] patients had lower cognitive functioning based on physician administered and study-partner scales but perhaps demonstrated lower awareness based on self-examination. These findings underscore that accuracy of diagnosis will lead to different care pathways as suggested by the IDEAS study [26], especially where the cause of cognitive decline may be treatable. Future longitudinal GERAS-US data will aid in understanding the longitudinal impact and value of early amyloid positivity on patients, caregivers, and society.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing support was provided by Teresa Tartaglione, PharmD (Synchrogenix, a Certara Company, Wilmington, Delaware). The authors thank the following who provided support to the conduct of this study: United Biosource Corporation (Juan Torres, Julio Puth, Deborah McGinley, and the United Biosource Corporation team) and the GERAS team (Rita Papen, Jose Luis Guerra, and Deanilee Deckard). The authors also thank each of the study investigators, site personnel, patients, and study partners for their participation in this study.

Eli Lilly and Company is the sole sponsor and funder for this study; the sponsor was responsible for the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, and decision to publish the findings.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-0430r2).

REFERENCES

- [1]. Alzheimer’s Association (2016) 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 12, 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) 5th ed Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Liu S, Liu J, Wang XD, Shi Z, Zhou Y, Li J, Yu T, Ji Y (2018) Caregiver burden, sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in dementia caregivers: A comparison of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 30, 1131–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Wimo A, Reed CC, Dodel R, Belger M, Jones RW, Happich M, Argimon JM, Bruno G, Novick D, Vellas B, Haro JM (2013) The GERAS Study: A prospective observational study of costs and resource use in community dwellers with Alzheimer’s disease in three European countries – study design and baseline findings. J Alzheimers Dis 36, 385–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Kirson NY, Scott Andrews J, Desai U, King SB, Schonfeld S, Birnbaum HG, Ball DE, Kahle-Wrobleski K (2018) Patient characteristics and outcomes associated with receiving an earlier versus later diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 61, 295–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Lin PJ, Neumann PJ (2013) The economics of mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 9, 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Zucchella C, Bartolo M, Pasotti C, Chiapella L, Sinforiani E (2012) Caregiver burden and coping in early-stage Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 26, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Jack CR Jr (2011) Alliance for aging research AD biomarkers work group: Structural MRI. Neurobiol Aging 32(Suppl 1), S48–S57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Morris GP, Clark IA, Vissel B (2014) Inconsistencies and controversies surrounding the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2, 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Laforce R Jr, Rabinovici GD (2011) Amyloid imaging in the differential diagnosis of dementia: Review and potential clinical applications. Alzheimers Res Ther 3, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, Donohoe KJ, Foster NL, Herscovitch P, Karlawish JH, Rowe CC, Carrillo MC, Hartley DM, Hedrick S, Mitchell K, Pappas V, Thies WH (2013) Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: A report of the Amyloid Imaging Taskforce, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. J Nucl Med 9, 476–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Teng E, Becker BW, Woo E, Knopman DS, Cummings JL, Lu PH (2010) Utility of the functional activities questionnaire for distinguishing mild cognitive impairment from very mild Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 24, 348–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL (1984) A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 141, 1356–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, Chance JM, Filos S (1982) Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol 37, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Amariglio RE, Donohue MC, Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Salmon DP, Ferris SH, Karantzoulis S, Aisen PS, Sperling RA, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (2015) Tracking early decline in cognitive function in older individuals at risk for Alzheimer disease dementia: The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Cognitive Function Instrument. JAMA Neurol 72, 446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J (1994) The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 44, 2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Trigg R, Skevington SM, Jones RW (2007) How can we best assess the quality of life of people with dementia? The Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia (BASQID). Gerontologist 47, 789–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J (1980) Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 20, 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Morycz RK (1985) Caregiving strain and desire to institutionalize family members with Alzheimer’s disease. Possible predictors and model development. Res Aging 7, 329–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. McCaskill GM, Burgio LD, Decoster J, Roff LL (2011) The use of Morycz’s desire-to-institutionalize scale across three racial/ethnic groups. J Aging Health 23, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Wimo A, Wetterholm AL, Mastey V, Winblad B (1998) Evaluation of the resource utilization and caregiver time in anti-dementia drug trials – a quantitative battery In The Health Economics of Dementia Wimo A, Karlsson G, Jonsson B, Winblad B, eds. John Wiley and Sons, London, pp. 465–499. [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Belger M, Argimon JM, Dodel R, Haro JM, Wimo A, Reed C (2015) Comparing resource use in Alzheimer’s disease across three European countries –18 month results of the GERAS study. ISPOR 18th Annual European Congress, Milan, Italy, 2015. Abstract PND64. [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Gidicsin CM, Carmasin JS, Maye JE, Coleman RE, Reiman EM, Sabbagh MN, Sadowsky CH, Fleisher AS, Murali Doraiswamy P, Carpenter AP, Clark CM, Joshi AD, Lu M, Grundman M, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Skovronsky DM, AV45-A11 study group (2013) Florbetapir (F18-AV-45) PET to assess amyloid burden in Alzheimer’s disease dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and normal aging. Alzheimers Dement 9, S72–S83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Witte MM, Trzepacz P, Case M, Yu P, Hochstetler H, Quinlivan M, Sundell K, Henley D (2014) Association between clinical measures and florbetapir F18 PET neuroimaging in mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 26, 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Rabinovici GD, Gatsonis C, Apgar C, Chaudhary K, Gareen I, Hanna L, Hendrix J, Hillner BE, Olson C, Lesman-Segev OH, Romanoff J, Siegel BA, Whitmer RA, Carrillo MC (2019) Association of amyloid positron emission tomography with subsequent change in clinical management among Medicare beneficiaries with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. JAMA 321, 1286–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA (2007) Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology 69, 2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Barnes, LL, Leurgans S, Aggarwal NT, Shah RC, Arvanitakis Z, James BD, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA (2015) Mixed pathology is more likely in black than white decedents with Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 85, 528–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Yu L, Boyle PA, Leurgans S, Schneider JA, Kryscio RJ, Wilson RS, Bennett DA (2015) Effect of common neuropathologies on progression of late life cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging 36, 2225–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. DeCarolis A, Corigliano V, Comparelli A, Sepe-Monti M, Cipollini V, Orzi F, Ferracuti S, Giubilei F (2012) Neuropsychological patterns underlying anosognosia in people with cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 34, 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Ready RE (2007) Commentary on “Health economics and the value of therapy in Alzheimer’s disease.” Patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 3, 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Black SE, Gauthier S, Dalziel W, Keren R, Correia J, Hew H, Binder C (2010) Canadian Alzheimer’s disease caregiver survey: Baby-boomer caregivers and burden of care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 25, 807–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Connors MH, Seeher K, Teixeira-Pinto A, Woodward M, Ames D, Brodaty H (2019) Mild cognitive impairment and caregiver burden: A 3-year-longitudinal study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, Holt JB, Croft JB, Mack D, McGuire LC (2019) Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimers Dement 15, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, Arenaza-Urquijo E, Astell AJ, Babiloni C, Bahar-Fuchs A, Bell J, Bowman GL, Brickman AM, Chételat G, Ciro C, Cohen AD, Dilworth-Anderson P, Dodge HH, Dreux S, Edland S, Esbensen A, Evered L, Ewers M, Fargo KN, Fortea J, Gonzalez H, Gustafson DR, Head E, Hendrix JA, Hofer SM, Johnson LA, Jutten R, Kilborn K, Lanctôt KL, Manly JJ, Martins RN, Mielke MM, Morris MC, Murray ME, Oh ES, Parra MA, Rissman RA, Roe CM, Santos OA, Scarmeas N, Schneider LS, Schupf N, Sikkes S, Snyder HM, Sohrabi HR, Stern Y, Strydom A, Tang Y, Terrera GM, Teunissen C, Melo van Lent D, Weinborn M, Wesselman L, Wilcock DM, Zetterberg H, O’Bryant SE; International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Alzheimer’s Association (2019) Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement 15, 292–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Santos OA, Pedraza O, Lucas JA, Duara R, Greig-Custo MT, Hanna Al-Shaikh FS, Liesinger AM, Bieniek KF, Hinkle KM, Lesser ER, Crook JE, Carrasquillo MM, Ross OA, Ertekin-Taner N, Graff-Radford NR, Dickson DW, Murray ME (2019) Ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer’s disease from the FLorida Autopsied Multi-Ethnic (FLAME) cohort. Alzheimers Dement 15, 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. US Census Bureau (2011) The Hispanic Population: 2010 Census Briefs. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-04.pdf. Accessed on June 27, 2019.

- [38]. Landau SM, Mintun MA, Joshi AD, Koeppe RA, Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2012) Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann Neurol 72, 578–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Fleisher AS, Chen K, Liu X, Roontiva A, Thiyyagura P, Ayutyanont N, Joshi AD, Clark CM, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Doraiswamy PM, Johnson KA, Skovronsky DM, Reiman EM (2011) Using positron emission tomography and florbetapir F18 to image cortical amyloid in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia due to Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 68, 1404–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Alzheimer’s Association (2015) Major new research study to demonstrate value of PET scans in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. https://alz.org/documents_custom/IDEAS_study_news_release_041615.pdf. Accessed on February 19, 2018.