Abstract

Objectives

This retrospective study aimed to investigate complications associated with the extraction of third molars at a tertiary healthcare centre in Oman.

Methods

All consecutive patients who underwent extraction of one or more impacted third molars under general anaesthesia at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, Oman, between January 2007 and December 2017 were included. Age, gender, indication for extraction, teeth removed, procedure and complications were recorded.

Results

A total of 1,116 third molars (56% mandibular and 44% maxillary) were extracted and the majority (67.7%) were from female patients. The mean age at extraction was 24 ± 5 years and most patients (77.7%) were 20–29 years old. The intraoperative and postoperative complication rates were 3.7% and 8.3%, respectively. The intraoperative complications included tuberosity fracture (1.2%), root fracture (1.1%), bleeding (0.7%), soft tissue injury (0.5%) and adjacent tooth damage (0.2%). Postoperative complications were sensory nerve injuries (7.2%), swelling/pain/trismus (0.6%) and dry socket (0.5%). Nerve injury was temporary in 41 patients and permanent in four cases. A statistically significant relationship was observed between those aged 30–39 years and dry socket (P = 0.010) as well as bone removal and all postoperative complications (P = 0.001).

Conclusion

Most complications resulting from third molar extractions were minor and within the reported ranges in the scientific literature. However, increased age and bone removal were associated with a higher risk of complications. These findings may help to guide treatment planning, informed consent and patient education.

Keywords: Third Molar, Tooth Extraction, Complications, Lingual Nerve, Inferior Alveolar Nerve, Oman

Advances in Knowledge.

- This study supports the available worldwide literature on the complications of third molar extractions in Oman.

- To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first to highlight the complications of third molar extractions in Oman.

Application to Patient Care

- Indications for the removal of third molars and the anticipated outcome should be carefully reviewed during treatment planning.

- This study represents a continued movement towards the use of evidence-based medicine to discuss and explain outcomes, complications and the risk-benefit ratios with patients before any procedure.

Third molars are the most frequently impacted teeth and might fail to erupt into a normal functional position.1 The prevalence of impacted third molars ranges between 16.7–68.6% across various populations.2–9 Studies from the Gulf region have reported an impacted third molars rate of 32–40.5%.8,9 A recently published study from Oman found that 54.3% of young Omani adults between 19–26 years old have at least one impacted third molar.10

Extraction of third molars is one of the most common procedures performed by oral surgeons. Generally, these surgeries do not encounter difficulties but at times can result in complications; a complication rate of 4.6–30.9% following the extraction of third molars is reported in the literature.11–15 Complications may occur intraoperatively or develop during the postoperative period. Intraoperative complications may include bleeding, damage to adjacent teeth, injury to surrounding tissues, displacement of teeth into adjacent spaces, fracture of the root, maxillary tuberosity or the mandible. Postoperative complications may include swelling, pain, trismus, prolonged bleeding, dry socket, infection and sensory alterations of the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) or lingual nerve (LN).

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study in Oman to determine the complications associated with third molar extraction. Reporting the associated complications in the Omani population is vital, given the reported high prevalence of impacted third molars that may require future extraction. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the various complications associated with third molar extraction at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH), Muscat, Oman.

Methods

This retrospective analytical study was conducted at SQUH between January 2007 and December 2017 and included all consecutive patients who underwent removal of one or more impacted third molars under general anaesthesia (GA). Patient’s records were collected using the TrakCare electronic patient record (EPR) system (InterSystems Corporation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA).

All procedures were performed by consultant oral and maxillofacial surgeons and their designated subordinates who were trained to extract third molars. All patients underwent standard surgical protocol.

Patients with known bleeding diathesis or who were taking medications which prolonged bleeding were prepared and optimised prior to the procedure and necessary local haemostatic measures were used in all such cases. In the current cases, bleeding was not included as an intraoperative complication.

The extraction technique involved the removal of third molars with or without mucoperiosteal flap elevation and lingual flap retraction, bone removal and tooth sectioning using surgical drills, elevators and/or forceps. After tooth extraction, the sockets were irrigated with chlorhexidine, bony irregularities were corrected and surgical wounds were closed using absorbable sutures. Following the procedure, detailed postoperative instructions were given to the patients and suitable antibiotics and analgesics were prescribed. Routine follow-up was done after three weeks and, in case of complications, extended follow-up was arranged.

Clinically significant intraoperative bleeding was managed by applying pressure, packing with Surgicel® (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, New Jersey, USA) and suturing the sockets.

The study variables were age, gender, teeth removed, an indication for extraction, surgical procedure and complications. Microsoft Excel, Version 16.0 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to create a record of all data collected during the course of this study.

All data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). The relationship between study variables and complications and between intraoperative and postoperative complications were analysed using chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman (MREC #1239). All data, including patient identification, history and other details remained confidential.

Results

A total of 337 patients had at least one third molar extracted under GA at SQUH during the study period. From those patients, a total of 1,116 third molars were extracted with the majority (67.7%) from female patients. The mean age of the subjects was 24 ± 5 years (range: 15–55 years) and most (77.7%) were 20–29 years old. The average number of teeth extracted per patient was 3.3 ± 0.9 and 56% were mandibular third molars. The most common indication for molar extraction was pericoronitis (34.1%); in 35.3% of records the reason for removal was not mentioned. Approximately half of third molars (50.4%) were surgically extracted and involved buccal and distal bone removal with or without sectioning the tooth. Among non-surgically extracted teeth, most were maxillary third molars [Table 1].

Table 1.

Preoperative and intraoperative characteristics of patients who underwent extraction of third molars at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, Oman between January 2007 and December 2017 (N = 337)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 109 (32.3) |

| Female | 228 (67.7) |

| Age range in years | |

| <20 | 35 (10.4) |

| 20–29 | 262 (77.7) |

| 30–39 | 35 (10.4) |

| ≥40 | 5 (1.5) |

| Indication for extraction | |

| Decay/pulpitis | 14 (4.2) |

| Chronic pain | 42 (12.5) |

| Pericoronitis | 115 (34.1) |

| Cheek bite | 16 (4.7) |

| Adjacent tooth decay | 5 (1.5) |

| Orthodontic | 11 (3.3) |

| Pathology | 3 (0.9) |

| Prophylactic | 8 (2.4) |

| Temporomandibular joint disorders | 4 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 119 (35.3) |

| Location of extracted third molars (N = 1,116) | |

| Maxilla | 491 (44) |

| Mandible | 625 (56) |

| Average per patient | 3.3 |

| Operative approach* | |

| Simple elevation | 554 (49.6) |

| Bone removal | 512 (45.9) |

| Tooth sectioning | 223 (20) |

Percentages do not add up to 100% as multiple approaches may have been used.

In this study, the rate of intraoperative and postoperative complications was 3.7% and 8.3%, respectively. Most intraoperative complications were minor with tuberosity fractures (1.2%) being the most common, followed by fractures of the apical third of the root (1.1%) and bleeding (0.7%). Postoperative complications were either inflammatory in nature (1.1%)—included swelling, pain, trismus and dry socket—or related to nerve injuries (7.2%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Type and frequency of complications following extraction of third molars

| Complication | Frequency | Percentage by patient (n = 337) | Percentage by tooth (n = 1,116) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative complications | |||

| Root fracture | 12 | 3.6 | 1.1 |

| Bleeding | 8 | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| Tuberosity fracture | 6 | 1.2 | 1.2* |

| Soft tissue injury | 6 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| Damage adjacent tooth | 2 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Postoperative complications | |||

| Swelling/pain/trismus | 7 | 2.1 | 0.6 |

| Dry socket | 6 | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| LN injury | 35 | 10.4 | 5.6† |

| IAN injury | 10 | 3.0 | 1.6† |

LN = lingual nerve; IAN = inferior alveolar nerve.

n = 491 (number of maxillary third molars);

n = 625 (number of mandibular third molars).

Among the 625 extracted mandibular third molars, 45 cases reported nerve injuries, of which the majority (91.1%) were temporary injuries (LN = 71.1%; IAN = 20%), and few (8.9%) were permanent injuries (LN = 6.7%; IAN = 2.2%). Based on the total extracted mandibular third molars, the overall rate of permanent nerve damage was found to be 0.7% (LN = 0.5%; IAN = 0.2%), while the overall temporary nerve damage was 6.5% (LN = 5.1%; IAN = 1.4%).

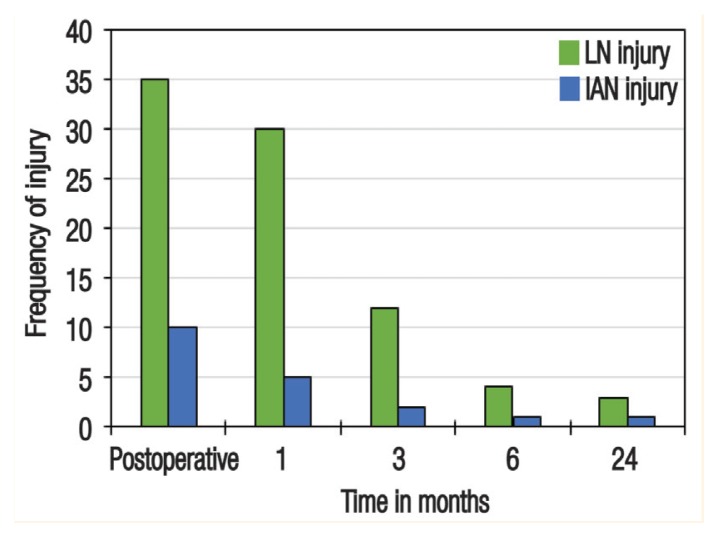

Among the LN injury cases, all except four resolved within six months after the procedure. Among the IAN injury cases, all except two resolved within the first three months after the procedure. Three cases of LN injury (0.5%) and one case of IAN injury (0.2%) had no recovery of sensation during the two-year follow-up period and were considered permanent injuries [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Timeline of postoperative recovery for lingual nerve and inferior alveolar nerve injuries.

LN = lingual nerve; IAN = inferior alveolar nerve.

A statistically significant relationship was observed between patients aged 30–39 years and dry socket (P = 0.010) as well as between bone removal and all postoperative complications (P = 0.001). No other variables, intraoperative complications or postoperative complications showed statistically significant relationships.

Discussion

Complications associated with third molar removal are not uncommon in dental and maxillofacial surgical procedures. Complications vary from minor inflammatory reactions such as pain and swelling to nerve damage, mandibular fracture and severe life-threatening infections.16 In the current study, the overall intraoperative and postoperative complication rates were 3.7% and 8.3%, respectively. The majority of reported complications were minor and transient in terms of overall patient health. These complication rates were within the ranges reported in the literature. Most studies mainly reported postoperative rather than intraoperative complication rates. Azenha et al. demonstrated an overall complication rate of 10.4%, while Bui et al. and Muhonen et al. reported postoperative complication rates of 9.8% and 9.1%, respectively.12,17,18

The current study showed that complications associated with mandibular third molar extraction occurred more frequently than with maxillary third molars. Of the 98 complications documented, 79 (80.6%) were associated with mandibular third molars. Most studies related to complications of third molar removal have stated similar findings.12–15

In this study, intraoperative complications were encountered in 40 cases. There were 12 cases of unretrieved root fractures; the root fragments were usually fragments of the apical third and were in close proximity to vital structures such as the inferior alveolar canal (IAC) or the maxillary sinus and required additional bone removal for retrieval with possible risk of damage to adjacent structures. In the postoperative period, none of these cases reported any secondary complications.

Clinically significant intraoperative bleeding was encountered in eight cases (0.7%) in the current study, which is comparable to the reported range of 0.2–5.8%.11 Bui et al. determined that the frequency of unexpected haemorrhage was 0.6% and an American age-related third molar study reported a frequency of 0.7%.12,13 The variability of reported rates could be due to the varying definitions and parameters of estimating bleeding.

The current study found six cases of tuberosity fracture, all of which were managed conservatively. Six cases of soft tissue injury that occurred due to tearing of the adjacent oral mucosal tissue were managed by primary closure. Iatrogenic damage to an adjacent tooth was encountered in two cases; in one of those cases, the coronal restoration of an adjacent tooth was fractured. Teeth with large restorations or carious lesions are at risk of fracture or damage upon elevation (rate: 0.3–0.4%).15 In the second case of iatrogenic damage, the adjacent second molar was luxated from its socket, which was repositioned and stabilised. During follow-up, it was found to have satisfactory stability without the need for further treatment. Furthermore, none of the intraoperative complications revealed any statistically significant association with postoperative complications.

The most commonly reported postoperative complication of third molar removal in the literature are dry socket, infection, bleeding and sensory disturbances due to nerve injuries.11–23 In the present study, the overall postoperative complication rate was 8.3%. Extraction of third molars is often associated with expected and typically transient postoperative pain, swelling and trismus; however, at times, this pain may present beyond the first postoperative week and may require additional treatment such as placement of a dressing or administration of antibiotics during a follow-up visit.11 Seven such cases were found in the current study based on subjective findings mentioned in the EPR. In these cases, the symptoms gradually resolved with supportive measures.

The literature reports a frequency of dry socket ranging from 0.3–26% for all extractions and is known to occur more frequently following third molar extraction.11–14 Some controlled studies have reported a rate of up to 25–30% after the extraction of mandibular third molars.19 Several studies have suggested that increased age, being female, the use of oral contraceptives, smoking, surgical trauma and pericoronitis are risk factors for dry socket.14,19–21 The current study had a relatively low rate of dry socket (0.5%), with all cases occurring in relation to mandibular third molars and four occurred in patients aged 30–39 years old. However, contrary to published literature, dry socket occurred in four males who were non-smokers and two females who were not on oral contraceptives.

Injuries to the IAN and LN are well-known and are frequently occurring complications of third molar extraction. This type of injury is often troubling to both patients and surgeons and may result in considerable morbidity and litigation.22 Previous studies have shown widely ranging rates of LN and IAN injuries (0–23% and 0.4–8.1%, respectively).12,15,22,23 In the present study, the LN and IAN injury rates were 5.6% and 1.6%, respectively. In LN injury, patients usually have a loss of sensation on the affected side of the tongue. In a cadaveric study, Kiesselbach and Chamberlain found the position of LN to be highly inconsistent, making patients vulnerable to damage throughout the procedure (i.e., during incision, mucoperiosteal flap elevation, lingual flap retraction, tooth sectioning, tooth extraction and suturing).24

In the current cases that had LN injury, the corresponding third molars had been surgically extracted and involved mucoperiosteal flap elevation, lingual flap retraction and bone removal. However, lingual flap retraction and LN injury did not show any statistically significant relationship. There was progressive improvement in the follow-up period with spontaneous resolution of symptoms of LN injury, with most cases resolving within the first three postoperative months and 88.6% of cases resolved within six months. In one case, there was a delayed resolution of 12 months; in another case, LNs were bilaterally affected and then resolved within one month. In three cases, no improvement was observed in tongue numbness after a two-year follow-up period and these cases were classified as having permanent damage.

In cases of IAN injury, patients usually have a loss of sensation in the lower lip with or without chin involvement on the affected side. In addition, patients may also present with tingling, tickling or burning sensations. Proximity of the third molars to the IAC is the most predictive factor for IAN injury.22 In the current study, all cases of IAN injury radiographically showed that the roots of the extracted teeth were in close proximity to the IAC. However, there was no statistically significant relationship between IAN injury and proximity of the corresponding tooth to the IAC. Among all patients who reported with IAN injury, the majority (90%) recovered within 3–6 months. In one case, there were no signs of improvement in lip numbness after a two-year follow-up period; thus, this numbness was regarded as permanent damage. In this study, the rate of permanent neurosensory damage to the LN and IAN was 0.5% and 0.2%, respectively, which is in line with rates in the literature.22,25

Patient factors (e.g. age, medical status, medication regimens and social habits), tooth factors (e.g. type of impaction and tooth position), operative factors (e.g. duration, technique and surgeon experience) and anaesthetic factors (e.g. local and general anaesthesia) have been reported as being associated with complications of third molar extraction.11,12 However, there was no statistical relationship in the current study between any of these factors and complications, except age and removal of bone.

Patients aged 30–39 years had higher rates of dry socket in this study, which is in agreement with published studies.21 Rood suggested that permanent damage to the IAN and LN was significantly related to bone removal with a surgical drill.26 This suggestion was consistent with the findings from the present study where there was a statistically significant relationship between bone removal and nerve injuries. Brann et al. and Costantinides et al. found that the rates of LN and IAN damage were more frequent when mandibular third molars were extracted under GA compared to local anaesthesia.27,28 This finding could be due to surgical difficulty, preoperative pathology, age or anatomic position.27

Postoperative infections after third molar extraction have been frequently reported in the literature, with rates ranging from 0.8–4.2%.11 However, no cases of postoperative infection were encountered in the current study.

This study has some limitations. Cases of third molar removal performed under local anaesthesia were excluded; including these cases could have resulted in a bigger sample size and more comprehensive complication data. Furthermore, as this study was retrospective, cases with limited or missing data were encountered. A more complete data set could have helped analyse complications more precisely if information had been available detailing anatomic and radiographic positions of teeth, position of the IAN, indications for removal, social history including smoking, surgical difficulties and surgeon experience. This shortcoming highlights the necessity for more comprehensive record maintenance and further studies that should include more parameters, such as risk factors that can affect treatment outcome; this may help in minimising complications in third molar extraction.

Conclusion

This retrospective study is the first to analyse the various complications associated with third molar extraction in Oman. The results suggest that most complications of third molar extraction are minor and within ranges reported in the literature. However, increased age and bone removal were found to increase the risk of postoperative complications. Hence, a careful review of the indications and the necessity of an extraction should be considered preoperatively. These findings may help to improve treatment planning and patient education.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this study.

Reference

- 1.Miloro M, Ghali GE, Larsen PE, Waite PD. Peterson’s Principles of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2nd ed. London: BC Decker Inc; 2004. p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown LH, Berkman S, Cohen D, Kaplan AL, Rosenberg M. A radiological study of the frequency and distribution of impacted teeth. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1982;37:627–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fanning EA, Moorrees CF. A comparison of permanent mandibular molar formation in Australian Aborigines and Caucasoids. Arch Oral Biol. 1969;14:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(69)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hugosan A, Kugelberg CF. The prevalence of third molars in a Swedish population. An epidemiological study. Community Dent Health. 1988;5:121–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashemipour MA, Tahmasbi-Arashlow MT, Fahimi-Hanzaei FF. Incidence of impacted mandibular and maxillary third molars: A radiographic study in Southeast Iran population. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:e140–5. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaya GS, Aslan M, Ömezil MM, Dayı E. Some morphological features related to mandibular third molar impaction. J Clin Exp Dent. 2010;2:12–17. doi: 10.4317/jced.2.e12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattab FN, Rawashdeh MA, Fahmy MS. Impaction status of third molars in Jordanian students. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:24–9. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(05)80068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haidar Z, Shalhoub SY. The incidence of impacted wisdom teeth in a Saudi community. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15:569–71. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(86)80060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan AH. Pattern of third molar impaction in a Saudi population. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2010;2:109–13. doi: 10.2147/cciden.s12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Anqudi SM, Al-Sudairy S, Al-Hosni A, Al-Maniri A. Prevalence and pattern of third molar impaction: A retrospective study of radiographs in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2014;14:e388–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouloux GF, Steed MB, Perciaccante VJ. Complications of third molar surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2007;19:117–28. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bui CH, Seldin EB, Dodson TB. Types, frequencies, and risk factors for complications after third molar extraction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1379–89. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiapasco M, De Cicco L, Marrone G. Side effects and complications associated with third molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:412–20. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90005-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haug RH, Perrott DH, Gonzalez ML, Talwar RM. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons age-related third molar study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sisk AL, Hammer WB, Shelton DW, Joy ED., Jr Complications following removal of impacted third molars: The role of the experience of the surgeon. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44:855–9. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(86)90221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brauer HU. Unusual complications associated with third molar surgery: A systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:565–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azenha MR, Kato RB, Bueno RB, Neto PJ, Ribeiro MC. Accidents and complications associated to third molar surgeries performed by dentistry students. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;18:459–64. doi: 10.1007/s10006-013-0439-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhonen A, Ventä I, Ylipaavalniemi P. Factors predisposing to postoperative complications related to wisdom tooth surgery among university students. J Am Coll Health. 1997;46:39–42. doi: 10.1080/07448489709595585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blum IR. Contemporary views on dry socket (alveolar osteitis): A clinical appraisal of standardization, aetiopathogenesis and management: A critical review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:309–17. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia AG, Grana PM, Sampedro FG, Diago MP, Rey JM. Does oral contraceptive use affect the incidence of complications after extraction of a mandibular third molar? Br Dent J. 2003;194:453–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander RE. Dental extraction wound management: A case against medicating postextraction sockets. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:538–51. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(00)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerjes W, Upile T, Shah P, Nhembe F, Gudka D, Kafas P, et al. Risk factors associated with injury to the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves following third molar surgery-revisited. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Middlehurst RJ, Barker GR, Rood JP. Postoperative morbidity with mandibular third molar surgery: A comparison of two techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:474–6. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90415-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiesselbach JE, Chamberlain JG. Clinical and anatomic observations on the relationship of the lingual nerve to the mandibular third molar region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:565–7. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90631-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carmichael FA, McGowan DA. Incidence of nerve damage following third molar removal: A west of Scotland oral surgery research group study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;30:78–82. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(92)90074-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rood JP. Permanent damage to inferior alveolar and lingual nerves during the removal of impacted mandibular third molars. Comparison of two methods of bone removal. Br Dent J. 1992;172:108–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brann CR, Brickley MR, Shepherd JP. Factors influencing nerve damage during lower third molar surgery. Br Dent J. 1999;186:514–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costantinides F, Biasotto M, Maglione M, Di Lenarda R. Local vs general anaesthesia in the development of neurosensory disturbances after mandibular third molars extraction: A retrospective study of 534 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016;21:e724–30. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]