Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate whether rapid fluorescent tissue examination immediately after colorectal cancer liver metastasis (CLM) ablation correlates to standard pathologic and immunohistochemical (IHC) assessments.

Methods:

This prospective, NIH-supported study enrolled 34 consecutive patients with 53 CLM ablated between January 2011 and December 2014. Immediately after ablation, core needle sampling of the ablation zone was performed. Tissue samples were evaluated with fluorescent viability (MitoTracker Red) and nuclear (Hoechst) stains. Confocal microscope imaging was performed within 30 minutes from ablation. The same samples were subsequently fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Identified tumor cells underwent IHC staining for proliferation (Ki67) and viability (OxPhos). The study pathologist evaluated separately the fluorescent images to detect viable tumor cells, blinded to the H&E and IHC assessment. Sensitivity, specificity and overall concordance of the fluorescent versus H&E and IHC assessments were calculated.

Results:

A total of 63 tissue samples were collected and processed. The overall concordance rate between the immediate fluorescent and the subsequent H&E and IHC assessments was 94% (59/63). Fluorescent assessment sensitivity and specificity for the identification of tumor cells were 100% (18/18) and 91% (41/45) respectively.

Conclusions:

There was a high concordance rate between the immediate fluorescent and the standard H&E and IHC assessment of the ablation zone. Given the documented prognostic value of ablation zone tissue characteristics on outcomes after ablation of CLM, the fluorescent assessment offers a potential intra-procedural biomarker of complete tumor ablation.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the most common gastrointestinal malignancy and the second most common cause of cancer-related death.1 A significant percentage of patients develop colorectal liver metastases (CLM) during the course of their disease.2 Although hepatic resection is considered the treatment of choice for CLM, only up to 20% of patients are surgical candidates due to the extent of hepatic disease, the presence of significant extrahepatic tumor burden or comorbid conditions.3,4 Percutaneous image-guided tumor ablation is an alternative treatment for selected patients with relatively small hepatic tumors, with documented safety and efficacy.5,6 Limitations to percutaneous ablative techniques include incomplete tumor treatment and local tumor progression (LTP).5–8 Therefore, it is crucial to develop prognostic markers that can be applied in real time, to identify patients at increased risk for incomplete treatment and LTP after ablation. Such markers can guide decisions regarding additional ablations within the same treatment session or indicate the need for early administration of adjuvant therapies.

Treatment effectiveness is generally assessed with post-procedural anatomic contrast-enhanced imaging (US, CT, MRI) and/or metabolic imaging (PET/CT).9,11 However, LTP occurs even in the face of complete tumor ablation with sufficient margins by imaging (>5 mm all around the target tumor).5,10,12 This phenomenon can probably be attributed to the presence of residual viable tumor cells within the ablation zone that “escape” the spatial resolution of currently available morphologic and metabolic imaging.12 The presence of viable tumor cells in the ablation zone carries an increased risk for treatment failure, LTP, as well as shorter patient survival and cancer specific survival.12–17

Unlike surgical resection, ablative techniques are not routinely assessed or followed by pathologic assessment of the treated tumor and surrounding margins. Studies evaluating tissue adherent to radiofrequency electrodes after ablation have shown that the presence of viable/proliferating cells is an independent predictor of shorter LTP-free survival.13,14,16,17 This was confirmed prospectively with biopsy of the ablation zone and pathologic assessment after tissue fixation using immunohistochemical staining.12 In all the prior studies there was a very strong correlation between the identification of viable or proliferating tumor cells and local tumor progression. However, routine tissue processing and pathologic examination requires days, which can take even longer with use of immunohistochemical stains. Therefore, a common limitation of these described methods was the inability to provide immediate tissue evaluation at the time of the ablation, precluding the possibility of additional ablation in the same session for treatment completion and tumor eradication.18

The purpose of this prospective study was to evaluate if rapid tissue examination (within 30 minutes from ablation and sampling) using fluorescent stains is feasible and correlates with known standard pathologic examinations showing viable tumor cells with already documented prognostic value in predicting LTP after hepatic tumor and specifically CLM ablation.12–15

Materials and Methods

Patient selection

This NIH-supported, IRB-approved prospective study analyzed tissue collected from the center and margin of the ablation zone of CLM through core needle biopsies. Patients undergoing ablation of CLM were assessed for prospective enrollment in this Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant study.

Patients eligible for enrollment were those with up to three CLM (each <5 cm in largest diameter) and no more than three extrahepatic sites of disease. Patients with uncorrectable coagulopathy (INR >1.5 or a platelet count of <50,000/mm3) and those unable to undergo general anesthesia were not eligible.

Treatment

Between January 2011 and December 2014, 53 consecutive CLM in 34 patients were treated with image-guided ablation. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia with continuous monitoring by an anesthesiologist. Treatment modalities used were radiofrequency (RF; n=15), microwave (MW; n=34) and irreversible electroporation (IRE; n=4), depending on tumor size, shape and location, as well as operator preference. Electrode/applicator repositioning and overlapping ablations were performed to create an ablation zone with a minimum ablation margin of at least 5 mm uniformly around the target tumor. Electrode/applicator placement and accurate tumor targeting was performed under CT guidance aided by CT fluoroscopy and/or sonography whenever needed. PET/CT guidance was also used in 41/53 ablations.19 In all cases, the manufacturer’s recommended protocol was applied and completed.20,21 RF devices used were the Valley-Lab Cool-Tip (n=13; Covidien/Medtronic) and RITA Starburst XLi (n=2; Angiodynamics). MW devices used were the NEUWAVE ablation system (n=24; NeuWave Medical/Ethicon), the Amica system (n=5; Mermaid Medical), the Microsulis system (n=4; Angiodynamics) and the Emprint system (n=1; Covidien/Medtronic). The IRE device used was the Nanoknife System (n=4; Angiodynamics). The mean number of ablation probes used per tumor was 1.7 (range: 1-4) and overlapping ablations were performed in 45/53 cases (85%).

All patients were assessed for complete tumor ablation immediately after the procedure and at 6 weeks (± 2 weeks) after the ablation with a triphasic contrast enhanced CT. The ablation was considered technically successful when the ablation zone completely covered the target tumor.

Biopsy and tissue analysis

Immediately after the completion of tumor ablation, 18-20 gauge core biopsy specimens were collected from the center and the margin of the ablation zone using contrast enhanced CT and/or PET/CT with fusion technology.12 If available, tissue adherent to electrodes was also collected.15,16 For the purpose of this study, some of the tissue samples were submitted live (fresh) for immediate fluorescent analysis in the Molecular Cytology Core Facility and subsequently fixed for further morphologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Other biopsy tissue samples did not undergo fluorescent staining (only routine pathologic assessment) and are not discussed in this study.

A combination of fluorescent markers was used, including a nuclear fluorescent marker, Hoechst 33342 (blue fluorescent dye) and a mitochondria viability fluorescent marker, MitoTracker (MT) Red (red fluorescent dye), in an effort to detect live cancer cells in the ablation zone. These fluorescent dyes are often used in in vitro experiments but have also been applied to freshly excised tissues.22 MT Red is a fluorescent reagent that labels functionally active mitochondria in live cells by detecting intact mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Hoechst 33342 was added for counterstaining and labeling of all nuclei within the same tissue sample. All collected tissue samples were incubated for 20 minutes in the staining solution: DME media with 15mM HEPES buffer, 10% fetal calf serum, 500nM MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (Invitrogen), and 10 μg/m of Hoechst 33342 (Sigma). After incubation, samples were mounted for imaging with LSM 5 Live inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany) using 20x/0.8NA objective. 579 nm laser line was used to excite MT Red and 405 nm for Hoechst 33342. Several z-stacks per sample were obtained and reviewed.

Subsequently, the exact same tissue samples were fixed in formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 μm sections and stained with standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) morphologic stains.

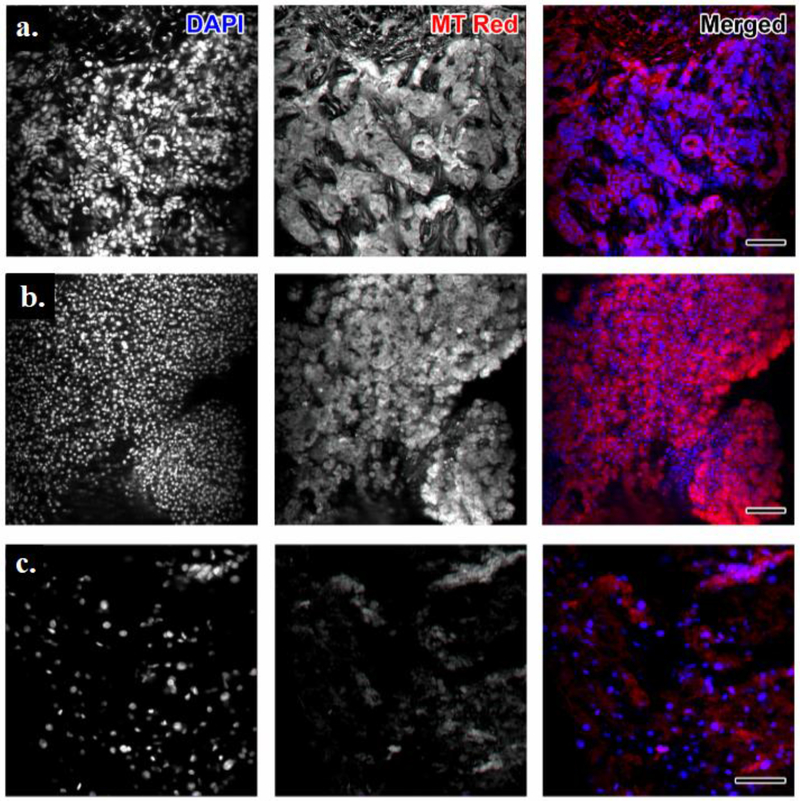

The study pathologist searched for cancer cells within the sample by observing the morphological characteristics of Hoechst-stained nuclei combined with the presence of MT Red. Cancer cells were identified by the presence of dense distribution of nuclei in Hoechst. When these were positive for MT Red, the classification of viable tumor was made (Figure 1a). Hoechst staining of characteristic large round nuclei (normal hepatocytes) with matching strong MT Red staining were classified as normal liver tissue (Figure 1b). Lack of MT Red signal in regions containing cells identified by the nuclear Hoechst stain were classified as non-viable/necrotic tissue. The fluorescent findings were validated with blinded comparison to the corresponding H&E morphologic stain with additional IHC for identified tumor cells.

Figure 1. Maximum projection of confocal stacks imaging tissues obtained from the ablation zone center.

Left most column is grayscale image of DAPI (nuclear) staining; next column is grayscale image of MitoTracker Red staining; next column is the merged image. (a) The sample was classified by the study pathologist as highly suggestive of residual viable tumor cells within the ablation zone due to the evident Mito Tracker Red positivity within dense distribution of nuclei. Ki67 and OxPhos immunohistochemical (IHC) staining has corroborated this finding. (b) Hoechst staining shows characteristic large round nuclei of hepatocytes that are alive and normal due to strong Mito Tracker Red staining. Samples like this one were classified as normal tissue. (c) MitoTracker Red was considered negative in regions containing cells, as depicted by the nuclear Hoechst stain. Thus, this tissue sample was classified as non-viable. H&E evaluation confirmed the presence of coagulative necrosis. Scale bar = 100 μm for all panels.

After H&E evaluation the study pathologist classified the same tissue samples as tumor cells, normal liver tissue and coagulation necrosis, blinded to the interpretation of the fluorescent assessment. Specimens with morphologically identified tumor cells on standard H&E examination (n=18) were further assessed with immunohistochemical stains for proliferation marker Ki67 and mitochondria viability marker OxPhos (OXP). This allowed further classification of identified cancer cells into viable tumor cells or coagulation necrosis, as well as direct correlations between MT Red and OXP positivity and cellular proliferation (Ki67 positive) and viability (OXP positive). Incubation in primary antibodies against proliferation marker, Ki67 (0.4 μg/ml, Vector Labs Cat#VP-K451) and OxPhos (2 μg/ml, Invitrogen Cat#459600) lasted 5 hours. After washing, chromogen-based detection was performed with DAB MAP kit (Ventana Medical Systems) according to the manufacturer instructions. The morphologic H&E classification combined with Ki67 and OXP immunohistochemistry was considered the gold standard reference for the evaluation of the ablation zone and the classification of tissue into viable tumor cells, normal liver cells and coagulation necrosis.

Statistics

Sensitivity, specificity and overall concordance of fluorescent stain findings versus standard pathologic examination with H&E and IHC were calculated.

Results

A total of 63 tissue samples were collected and processed from 53 ablated CLM in 34 patients. In all cases, there was imaging evidence of technically successful, complete tumor ablation. Forty-six specimens were obtained from the center of the ablation zone, 13 from the margin and 4 from tissue adherent on the utilized ablation electrodes.

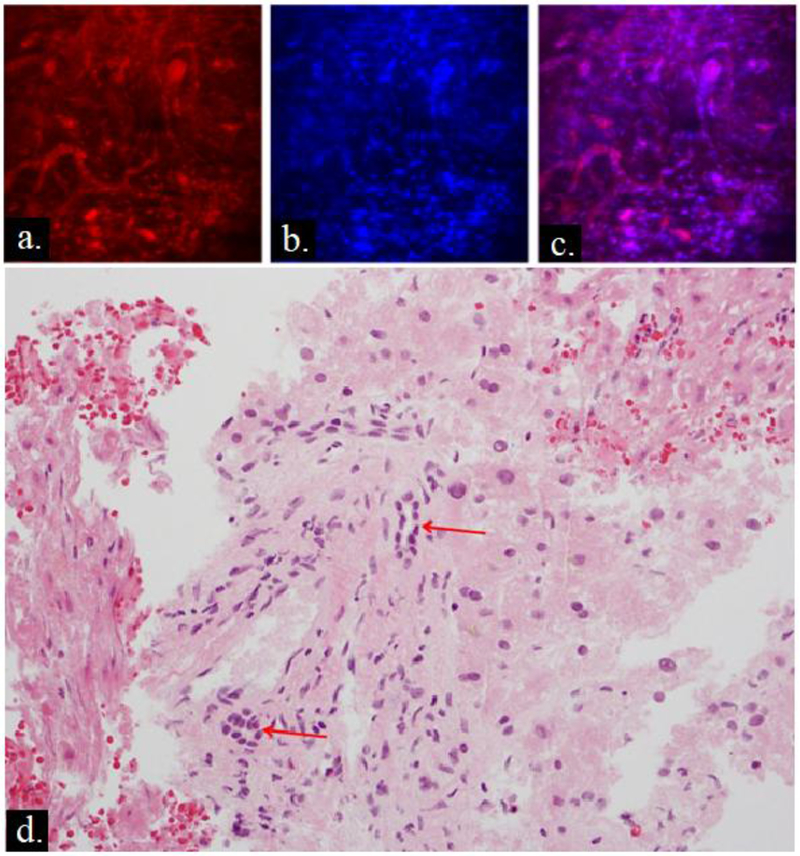

Twenty-two/63 (35%) specimens were considered positive for the presence of viable tumor cells on immediate fluorescent assessment. Eighteen of these 22 (82%) specimens contained tumor cells on morphologic H&E assessment. The four/22 false-positive samples identified as tumor cells on the fluorescent images corresponded to preserved cholangiocytes lining small bile ducts on H&E. The distribution of the cholangiocytes around the bile duct was misinterpreted on the morphologic fluorescent images (Hoechst) as indicative of the glandular morphology of adenocarcinoma (Figure 2). All 41 specimens (100%) classified as necrotic or non-cancerous on immediate fluorescent assessment displayed characteristics of complete coagulative necrosis or normal liver tissue on standard H&E morphologic assessment and did not undergo further processing with IHC.

Figure 2. False positive case.

Fluorescent images with (a) MitoTracker Red, (b) Hoechst, (c) composite image and (d) corresponding hematoxylin & eosin (H&E). The fluorescent images were considered positive for tumor cells, due to MitoTracker Red positivity in areas with dense distribution of nuclei. On standard pathologic examination H&E, there is no evidence of adenocarcinoma, however there are preserved cholangiocytes around bile ducts (red arrows) which were likely interpreted as tumor on fluorescent images.

The overall concordance rate between immediate fluorescent stain interpretation and standard H&E examination for the detection of tumor versus coagulation necrosis and normal liver parenchyma was 94% (59/63). Fluorescent stain sensitivity for the identification of samples positive for tumor on standard H&E was 100% (18/18) and specificity was 91% (41/45). For specimens containing tumor cells on H&E that were further processed with IHC, 16/18 were positive for both markers Ki67 and OXP. One specimen was positive to only Ki67 and in one specimen the collected tissue was inadequate for assessment with IHC.

Discussion

The results of our study show that rapid tissue analysis using fluorescent MT Red and Hoechst stains may be a potential immediate biomarker of complete liver tumor ablation and in particular CLM. This combination addresses the disadvantage of each fluorescent stain when used separately; MT Red may distinguish viable from necrotic/apoptotic cells but cannot differentiate benign from malignant cells. Nuclear labeling by Hoechst appears to provide a fluorescent equivalent of H&E and assists the detection of neoplastic cells, but it cannot assess viability. The combination of the two stains provides the ability to rapidly interrogate for residual viable tumor cells, with a relatively high concordance rate (94%) compared to lengthy standard pathologic assessment.

Ki67 positive tumor cells adherent to the electrode after hepatic tumor RF ablation have been associated with shorter LTP-free and overall survival. The presence of Ki67 positive tumor cells from the ablation zone was an independent predictor of shorter LTP-free survival (hazard ratio: 5.1).15 Snoeren et al. analyzed viability of tissue adherent to electrodes by the autofluorescence method using glucose-6-phosphate diaphorase staining and concluded that viable tissue was an independent risk factor for LTP.16 However, in all these studies tissue evaluation was performed after fixation and lengthy processing.13,15–17 Tanis et al. applied real time reflectance spectroscopy during RF ablation in 8 colon cancer live metastases and indicated over 97% correlation with histopathologic changes of necrosis and subsequent CT imaging of complete tumor ablation.18 The authors highlighted the value of real-time feedback during tumor ablation that could significantly improve success rates and diminish LTP after ablation. The study did not assess for the presence of residual viable tumor at the end of ablation.

Fujisawa et al. evaluated the use of YO-PRO-1, a green fluorescent DNA marker for cells with a compromised plasma membrane, as a potential immediate marker of cell death following RF ablation of CLM using biopsy samples from the ablation zone.23 More than 90% of cells were positive for this marker following ablation. Similar levels however of YO-PRO-1 positivity were encountered in dissected non-ablated pig and mouse liver specimens, leading to the conclusion that YO-PRO-1 has limited value as a potential immediate biomarker of complete tumor ablation.

Fluorescent stains used in the current study assessed cell viability based on mitochondrial function. The combination of the morphologic assessment with mitochondrial evaluation is extremely important and addresses several limitations pertaining to tissue assessment immediately after ablation. In particular, earlier work indicated that tumor cells identified within resected specimens after ablation could undergo further apoptosis and complete necrosis several days after RF ablation.24 This made immediate assessment of ablated specimens extremely difficult and indicated the need for the application of specific viability and apoptotic stains to accurately assess the status of tumor cells after ablation. Most of these stains require viable tumor processing with IHC that is lengthy and not easy to use as an immediate assay to detect residual viable tumor or necrosis. The development of such markers is critical as ablation is evolving as a cancer therapy with curative intent that could be offered instead of surgery.5,11,25 The ability to confirm complete tumor necrosis and more importantly the ability to detect residual viable tumor immediately after the completion of ablation is essential for providing the best possible care. Identification of residual tumor cells immediately after therapy would allow for application of additional ablation while the patient is still under general anesthesia, provided that and especially if there is a target identified by imaging. When additional ablation is not safe or feasible, the immediate assessment would alert the treating physicians for the presence of residual tumor cells that dramatically increase the risk of treatment failure and tumor progression. In the latter scenario, adjuvant therapy could be initiated similarly to the management of patients that undergo resection with tumor positive margins.26

In our study, all procedures were performed until there was imaging evidence of complete tumor ablation with adequate margins. There was no significant difference in the incidence of viable tumor cells in the post-ablation biopsy specimens between ablation modalities. In another study, we have shown no difference of local tumor progression between RF and MW ablation when data was stratified by margin, although the ability to obtain margins was impacted in perivascular tumors treated with RF but not those treated with MW.27 Patients found to have viable tumor cells on the intraprocedural biopsy continued routine imaging follow-up and were retreated only if there was imaging evidence of recurrence. There was no treatment decision made based on the results of the fluorescent stains in this cohort. The implementation of fluorescent stains into the treatment paradigm will be part of future clinical trial.

Limitations of our study include the relatively small number of specimens analyzed and the fact that pre-procedural biopsies were not obtained to allow comparison of fluorescent stains and imaging findings before and after ablation, as well as correlation with known technical factors,5,26,28 tumor markers and genomic profiles29–32 that may affect outcomes. The evaluation performed with biopsies is still incomplete and may miss areas of residual viable tumor within the ablation zone or the margins, especially if compared with completely excised specimens.12 Moreover, this was a proof of concept study for the use of fluorescent stains for rapid tissue assessment; this precliminary study was not designed to determine if the presence of cells considered malignant and viable with these stains places patients at increased risk for local recurrence. Finally, the fluorescent images and pathology slides were interpreted by a single pathologist, precluding assessment of interobserver variability.

To summarize, given the documented prognostic value of tissue characteristics on local tumor progression-free and overall survival in patients with CLM, ablation zone tissue evaluation with fluorescent stains appears to provide an intra-procedural biomarker of residual tumor or complete image-guided tumor ablation. This development could address a key limitation of ablation and potentially other image-guided locoregional therapies.

Table 1: Concordance of sample classification as either tumor negative or tumor positive with immediate fluorescent stain evaluation and standard morphologic assessment with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) by the study pathologist.

There was discordance in 4 cases, leading to an overall concordance rate of 94% (59/63). All 4 cases discordant samples were false positive on fluorescent stain evaluation.

| H&E Evaluation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Positive | Tumor Negative | Total | |||

| Fluorescent Stain | Evaluation | Tumor Positive | 18 | 4 | 22 |

| Tumor Negative | 0 | 41 | 41 | ||

| Total | 18 | 45 | 63 | ||

Synopsis:

Rapid assessment with fluorescent stains of tissue obtained from the ablation zone of colorectal cancer liver metastases is feasible and correlates with routine pathologic and immunohistochemical assessment which has documented prognostic value for local tumor progression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant R21 CA131763-01A1). We gratefully acknowledge Alessandra Garcia, BA (Research Study Assistant at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) for her contribution to this work.

Funding information: This study was supported by the NCI (R21 CA131763-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Herszenyi L, Tulassay Z. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal and liver tumors. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14(4):249–258. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20496531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnaud JP, Dumont P, Adloff M, Leguillou A, Py JM. Natural history of colorectal carcinoma with untreated liver metastases. Surg Gastroenterol. 1984;3(1):37–42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6522907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam R, Vinet E. Regional treatment of metastasis: Surgery of colorectal liver metastases. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(SUPPL. 4). doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberts SR, Poston GJ. Treatment advances in liver-limited metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(4):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shady W, Petre EN, Gonen M, et al. Percutaneous Radiofrequency Ablation of Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases: Factors Affecting Outcomes--A 10-year Experience at a Single Center. Radiology. 2016;278(2):601–611. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solbiati L, Livraghi T, Goldberg SN, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency ablation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: long-term results in 117 patients. Radiology. 2001;221(1):159–166. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2211001624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna NN. Radiofrequency ablation of primary and metastatic hepatic malignancies. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2004;4(2):92–100. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2004.n.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White RR, Avital I, Sofocleous CT, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence for percutaneous radiofrequency ablation and open wedge resection for solitary colorectal liver metastasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(3):256–263. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelis F, Sotirchos V, Violari E, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT Is an Immediate Imaging Biomarker of Treatment Success After Liver Metastasis Ablation. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(7):1052–1057. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.171926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Sofocleous CT, Erinjeri JP, et al. Margin size is an independent predictor of local tumor progression after ablation of colon cancer liver metastases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(1):166–175. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0377-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solbiati L, Ahmed M, Cova L, Ierace T, Brioschi M, Goldberg SN. Small liver colorectal metastases treated with percutaneous radiofrequency ablation: local response rate and long-term survival with up to 10-year follow-up. Radiology. 2012;265(3):958–968. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sotirchos VS, Petrovic LM, Gönen M, et al. Colorectal cancer liver metastases: Biopsy of the ablation zone and margins can be used to predict oncologic outcome. Radiology. 2016;280(3). doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016151005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sofocleous CT, Garg S, Petrovic LM, et al. Ki-67 is a prognostic biomarker of survival after radiofrequency ablation of liver malignancies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(13):4262–4269. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2461-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sofocleous CT, Garg SK, Cohen P, et al. Ki 67 is an independent predictive biomarker of cancer specific and local recurrence-free survival after lung tumor ablation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(3 SUPPL.). doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sofocleous CT, Nascimento RG, Petrovic LM, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of tissue adherent to multitined electrodes after RF ablation of liver malignancies can help predict local tumor progression: initial results. Radiology. 2008;249(1):364–374. doi:249/1/364[pii]\r 10.1148/radiol.2491071752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snoeren N, Huiskens J, Rijken AM, et al. Viable tumor tissue adherent to needle applicators after local ablation: A risk factor for local tumor progression. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(13):3702–3710. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1762-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snoeren N, Jansen MC, Rijken AM, et al. Assessment of viable tumour tissue attached to needle applicators after local ablation of liver tumours. Dig Surg. 2009;26(1):56–62. doi: 10.1159/000194946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanis E, Spliethoff JW, Evers DJ, et al. Real-time in vivo assessment of radiofrequency ablation of human colorectal liver metastases using diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;42(2):251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan ER, Sofocleous CT, Schöder H, et al. Split-Dose Technique for FDG PET/CT—guided Percutaneous Ablation: A Method to Facilitate Lesion Targeting and to Provide Immediate Assessment of Treatment Effectiveness. Radiology. 2013;268(1):288–295. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sofocleous CT, Sideras P, Petre EN. How we do it - A practical approach to hepatic metastases ablation techniques. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16(4):219–229. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, et al. Image-guided Tumor Ablation: Standardization of Terminology and Reporting Criteria—A 10-Year Update. Radiology. 2014;273(1):241–260. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boffa DJ, Waka J, Thomas D, et al. Measurement of apoptosis of intact human islets by confocal optical sectioning and stereologic analysis of YO-PRO-l-stained islets. Transplantation. 2005;79(7):842–845. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000155175.24802.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujisawa S, Romin Y, Barlas A, et al. Evaluation of YO-PRO-1 as an early marker of apoptosis following radiofrequency ablation of colon cancer liver metastases. Cytotechnology. 2014;66(2):259–273. doi: 10.1007/s10616-013-9565-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg SN, Gazelle GS, Compton CC, Mueller PR, Tanabe KK. Treatment of intrahepatic malignancy with radiofrequency ablation: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Cancer. 2000;88(11):2452–2463. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanis E, Nordlinger B, Mauer M, et al. Local recurrence rates after radiofrequency ablation or resection of colorectal liver metastases. Analysis of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer #40004 and #40983. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(5):912–919. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mbah NA, Scoggins C, McMasters K, Martin R. Impact of hepatectomy margin on survival following resection of colorectal metastasis: The role of adjuvant therapy and its effects. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(12):1394–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shady W, Petre EN, Do KG, et al. Percutaneous Microwave versus Radiofrequency Ablation of Colorectal Liver Metastases: Ablation with Clear Margins (A0) Provides the Best Local Tumor Control. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(2):268–275.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shady W, Petre EN, Do KG, et al. Percutaneous Microwave Versus Radiofrequency Ablation of Colorectal Liver Metastases: Ablation with Clear Margins (A0) Provides the Best Local Tumor Control. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shady W, Petre EN, Vakiani E, et al. Kras mutation is a marker of worse oncologic outcomes after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of colorectal liver metastases. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):66117–66127. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ziv E, Bergen M, Yarmohammadi H, et al. PI3K pathway mutations are associated with longer time to local progression after radioembolization of colorectal liver metastases. Oncotarget. 2017. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calandri M, Yamashita S, Gazzera C, et al. Ablation of colorectal liver metastasis: Interaction of ablation margins and RAS mutation profiling on local tumour progression-free survival. Eur Radiol February 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odisio BC, Yamashita S, Huang SY, et al. Local tumour progression after percutaneous ablation of colorectal liver metastases according to RAS mutation status. Br J Surg. 2017;104(6):760–768. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]