Abstract

Introduction

Individuals with delayed below-knee amputation have previously reported superior clinical outcomes compared with lower limb reconstruction. The UK military have since introduced a passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO) into its rehabilitation care pathway to improve limb salvage outcomes. The aims were to determine if wearing a PDAFO improves medium-term clinical outcomes and what influence does multidisciplinary team (MDT) rehabilitation have after PDAFO fitting? Also, what longitudinal changes in clinical outcomes occur with MDT rehabilitation and how do these results compare with patients with previous lower extremity trauma discharged prior to PDAFO availability?

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated levels of mobility, activities of daily living, anxiety, depression and pain in a heterogeneous group of 23 injured UK servicemen 34±11 months after PDAFO provision. We also retrospectively analysed 16 patients across four time points (pre-PDAFO provision, first, second and final inpatient admissions post-PDAFO provision) using identical outcome measures, plus the 6 min walk test.

Results

Outcomes were compared with previous below-knee limb salvage and amputees. Before PDAFO, 74% were able to walk and 4% were able to run independently. At follow-up, this increased to 91% and 57%, respectively. Mean depression and anxiety scores remained stable over time (p>0.05). After 3 weeks, all patients could walk independently (pre-PDAFO=31%). Mean 6 min walk distance significantly increased from 440±75 m (pre-PDAFO) to 533±68 m at last admission (p=0.003). The ability to run increased from 6% to 44% after one admission.

Conclusions

All functional and most psychosocial outcomes in PDAFO users were superior to previous limb salvage and comparable to previous below-knee amputees. The PDAFO facilitated favourable short-term and medium-term changes in all clinical outcome measurements.

Keywords: rehabilitation, orthosis, outcomes, function, lower-limb, trauma

Key messages.

In patients with lower extremity injuries commonly considered to demonstrate poor long-term outcomes, passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO) provision has facilitated favourable medium-term changes in a range of patient-reported measures.

PDAFO provision alongside multidisciplinary team rehabilitation demonstrates superior levels of function and pain compared with patients with previous below-knee limb salvage treated at the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre.

PDAFO users are able to achieve comparable levels of function and pain responses to elective below-knee amputees with advanced and considerably more expensive prosthesis provision.

Proceeding with limb salvage alongside PDAFO provision could lead to advantageous and prolonged cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, mental health and vocational benefits for patients with severe lower extremity injury.

The PDAFO is considered an important component in the aftercare/management of severe lower extremity trauma and a viable alternative to elective below-knee amputation in some patients.

Introduction

Limb salvage can result in decreased function, persistent pain and disability.1–7 The US and UK military have previously reported more favourable functional and psychosocial outcomes in traumatic lower limb amputee groups compared with patients who underwent lower limb reconstruction.3 8 Of note, US military amputees were previously 2.6 times more likely to engage in vigorous activity than their limb salvage counterparts, and 50% of unilateral amputees from the UK military were able to run independently compared with just 5% of their lower limb salvage patients.3 8

The Intrepid Dynamic Exoskeletal Orthosis (IDEO), a passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO), was developed to reduce the high rates of delayed amputation in US service personnel who experienced high-energy lower extremity trauma.9 This PDAFO has since demonstrated improved functional and psychosocial outcomes in its users.10–13 Despite the positive short-term outcomes (monitoring over 8 weeks of rehabilitation in a US military rehabilitation centre), there is a paucity of literature detailing longer term follow-up and longitudinal effects of wearing a PDAFO on clinical outcomes after its provision.

The UK Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre (DMRC) Headley Court has since developed the IDEO by using different manufacturing techniques. The PDAFO used by the UK military uses the concept of the US IDEO brace and was developed to improve the durability of these bespoke, custom-fitted devices, without increasing the weight or size. The IDEO is manufactured from composite fibres and acrylic resin9 using a ‘wet lay-up technique’, whereas the UK-manufactured PDAFO uses composite fibres preimpregnated with epoxy resin, thereby affecting the weight and durability of the device. These techniques in manufacturing reflect how prosthetic running blades are commonly made (see online supplementary file 1 for an image of the orthosis). Each PDAFO redistributes and redirects forces exerted on the foot and ankle complex. It transmits the force proximally on the limb, in areas such as the patella tendon and medial flares of the tibial condyle which is load tolerant. It incorporates a solid ankle foot plate that provides maximum support to the foot and ankle in all three planes of motion. A posterior carbon strut that stores mechanical energy as the forefoot is loaded between mid-stance and terminal stance. The orthosis then releases this stored energy when unloaded to facilitate additional power at push-off.9

jramc-2018-001082supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

The prescription of this PDAFO has now become widely integrated into the rehabilitation of distal lower extremity injuries at DMRC. However, the short-term to medium-term functional and psychosocial outcomes of UK military PDAFO users are currently unknown. It is also important to determine how these outcomes compared with patients with severe lower extremity injuries medically discharged prior to the availability of the PDAFO. Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to investigate if wearing a PDAFO can improve medium-term functional and psychosocial outcomes and what influence does multidisciplinary team (MDT) rehabilitation have after PDAFO fitting? A secondary aim will assess a subset of these patients and answer the following clinically important question: What longitudinal changes in functional and psychosocial outcomes occur with MDT rehabilitation and how do these results compare with patients with previous lower extremity trauma discharged prior to PDAFO availability?

Methods

Appropriate approval had been provided prior to commencing this clinical service evaluation. Clinicians at DMRC routinely record patient information and clinical data, including functional and psychosocial outcomes in all patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation. These clinical data were extracted from the Defence Medical Information Capability Program and used for the purposes of this service evaluation.

Current eligibility criteria for PDAFO provision at DMRC Headley Court

The criteria for being considered eligible for receiving a PDAFO at DMRC include: (1) biomechanical pain to the foot and ankle that is not responding well to standard rehabilitation treatment protocols; (2) plateau in functional ability postrehabilitation input and where level of function is deemed suboptimal; (3) sufficient proximal muscle control to use the orthosis and benefit from the energy returning properties; and (4) no open wounds or significant oedema that cannot be medically managed.

Aftercare for the PDAFO user

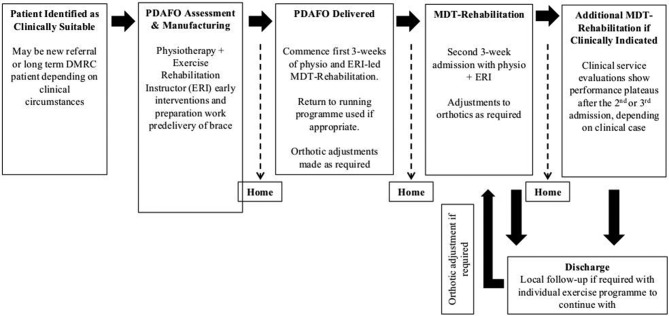

After injury and before the PDAFO is fitted, patients follow the UK Defence model of complex trauma rehabilitation.14 On receiving the orthosis, patients are encouraged to follow DMRC-recommended guidelines of two 3-week admissions (Figure 1). However, due to the stage of patient’s rehabilitation pathway (ie, imminent medical discharge) or personal preference (other life priorities), some patients cannot or choose not to participate in MDT rehabilitation after their PDAFO provision. The MDT rehabilitation of patients who were fitted with the PDAFO focused on correct use of the device, gait re-education and progressive strengthening, balance and flexibility exercises in order to maximise energy storage and return during both low-impact and high-impact activities.

Figure 1.

Passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO) delivery paradigm. DMRC, Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Study design

Stage 1: A retrospective medium-term (>12 months) follow-up evaluation of functional and psychosocial outcomes of PDAFO users who were admitted to inpatient rehabilitation at DMRC between November 2014 and February 2017. Stage 2: A retrospective longitudinal evaluation of these PDAFO users who were admitted to DMRC for MDT rehabilitation who completed a minimum of two 3-week inpatient admissions (the current recommended guidelines). These patients had their functional and psychosocial outcomes monitored over four time points (four inpatient admissions): preprovision of the PDAFO, first, second and final admissions post-PDAFO provision. Testing the patients before and after the intervention in a cross-over study design allows these patients to act as their own control. The clinical outcomes collected in stage 2 were then compared against the previously published8 outcomes of below-knee limb salvage (BK-LS) and delayed below-knee amputees (d-BKA) who had their final admission to DMRC prior to the availability of this custom-made PDAFO.8 Further analysis (presented in online supplementary file 2) investigated the clinical outcomes of all patients prescribed the PDAFO who later elected for amputation at three time points (1) their pre-PDAFO admission, (2) their final admission wearing their prosthetic device and (3) after >12 months of follow-up. There were no exclusion criteria based on severity of injury or the amount of previous MDT rehabilitation. Inclusion criteria for stage 2 were all PDAFO users who engaged in MDT rehabilitation for at least two 3-week inpatient admissions (the current recommended guidelines for PDAFO users treated within complex trauma at DMRC—Figure 1).

jramc-2018-001082supp002.pdf (67.5KB, pdf)

Functional and psychosocial outcome measures

Function

Stage 1 and 2 analysis: During each inpatient admission and within the follow-up questionnaire the level of mobility (‘run independently,’ ‘walk independently’ or ‘walk with an aid or adaptation’) and the ability to perform activities of daily living (‘independently’, ‘with an aid or adaptation’ or ‘requires support or assistance’) were recorded using DMRC developed tools.8

During stage 2 only: The 6 min walk test15 was completed at each inpatient admission to demonstrate the longitudinal changes in ambulatory function. The ability to progress into other less physically demanding job roles within the military or civilian sector is an important goal of rehabilitation at DMRC, therefore comparisons in 6 min walk distance (6MWD) were made to general population norms (>459 m).16

Psychosocial

Stages 1 and 2: The Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale17 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-918 are two validated patient-reported questionnaires. Two DMRC developed outcome tools were completed by clinicians to assess the requirement for mental health support and the assessment of ongoing pain (‘none’, ‘controlled’ or ‘uncontrolled’).8

Statistical analysis

This study used a convenient sample and therefore was not subject to any sample size power calculations. All data were checked for normality of distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and tests for skewness and kurtosis. Stage 1: pre-PDAFO and follow-up outcomes underwent an independent samples t-test. Most descriptive data are presented as prevalence (%) reported at baseline and follow-up. Stage 2 used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures design to determine if there was a significant main effect on the provision of the PDAFO on length of rehabilitation and clinical outcome measured. Post hoc analyses using Bonferroni were performed to determine the differences in the rate or magnitude of improvement in the objective physical performance measures and patient-reported outcome scores over time. Comparisons between PDAFO outcomes and patients with previous lower extremity trauma (BK-LS and d-BKA) were made using one-way ANOVA. The effect size was determined using the difference of the means. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (V.22; IBM). The level of significance was set a priori as p<0.05.

Results

To date, 65 UK military personnel have received a PDAFO, 6 (9%) have decided to pursue elective amputation post-PDAFO fitting. Forty of the 65 patients were admitted to DMRC for inpatient MDT rehabilitation prior to the provision of their PDAFO, allowing comparisons of medium-term follow-up and monitoring of longitudinal inpatient clinical data to baseline values.

The demographic and injury characteristics of PDAFO users for medium term and longitudinal follow-up are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and injury characteristics

| Medium-term follow-up | Longitudinal MDT rehabilitation (≥2 admissions) | |||

| All patients | Received ≥1 MDT rehabilitation admission post-PDAFO provision | Did not receive MDT rehabilitation post-PDAFO provision | ||

| n | 23 | 14 | 9 | 16 |

| Age (years) | 33±7 (23–53) | 31±7 (23–48) | 35±8 (29–53) | 31±5 (23–43) |

| Gender (% male) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Body height (cm) | 181±6 (167–192) | 180±6 (167–192) | 182±6 (168–190) | 180±6 (167–190) |

| Body mass (kg) | 90±12 (66–109) |

87±11 (66–106) |

93±14 (71–109) |

87±11 (66–106) |

| BMI (kg·m2) | 27±3 (22–32) |

27±2 (22–32) |

28±3 (23–32) |

27±3 (22–34) |

| BP | ||||

| Systolic | 134±11 (116–160) |

133±12 (116–160) |

136±10 (118–145) |

131±13 (116–160) |

| Diastolic | 77±10 (63–96) |

75±10 (63–96) |

79±9 (67–95) |

76±11 (63–96) |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| IED (%) | 9 (39) | 4 (29) | 5 (56) | 7 (44) |

| GSW (%) | 3 (13) | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 2 (13) |

| RTA (%) | 3 (13) | 3 (21) | – | 2 (13) |

| Fall (%) | 3 (13) | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 1 (6) |

| Sport (%) | 2 (9) | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 1 (6) |

| Non-specific MSK disorder (%) | 3 (13) | 2 (14) | 1 (11) | 3 (19) |

| Injury type* | ||||

| Fracture (%) | 17 (74) | 10 (71) | 7 (78) | 10 (63) |

| Nerve damage (%) | 8 (35) | 6 (43) | 2 (22) | 6 (38) |

| Degenerative joint (%) | 2 (9) | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 1 (6) |

| Bone segment injured† | ||||

| Tibia/fibula (%) | 5 (29) | 4 (40) | 1 (14) | 6 (60) |

| Malleolus (%) | 4 (24) | 2 (20) | 2 (29) | 1 (10) |

| Hind foot (%) | 10 (59) | 6 (60) | 4 (57) | 7 (70) |

| Mid-foot (%) | 5 (29) | 1 (10) | 4 (57) | 2 (20) |

| Additional complications/diagnosis | ||||

| Compartment syndrome (%) | 2 (9) | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | 1 (6) |

The values are given as the number of patients, with the percentage in parentheses.

BMI, body mass index; GSW, gunshot wound; IED, improvised explosive device; MDT, multidisciplinary team; MSK, musculoskeletal; PDAFO, passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis; RTA, road traffic accident.

*The injury types do not add up to the number of patients because some patients had multiple injuries.

†The numbers do not add up to the number of patients with fracture because some patients had injuries to multiple bone segments. The percentages of patients with fractured bone segments are a reflection of the total number of patients who experienced a fracture, not the total number of patients in each injury group.

Medium-term follow-up of PDAFO users

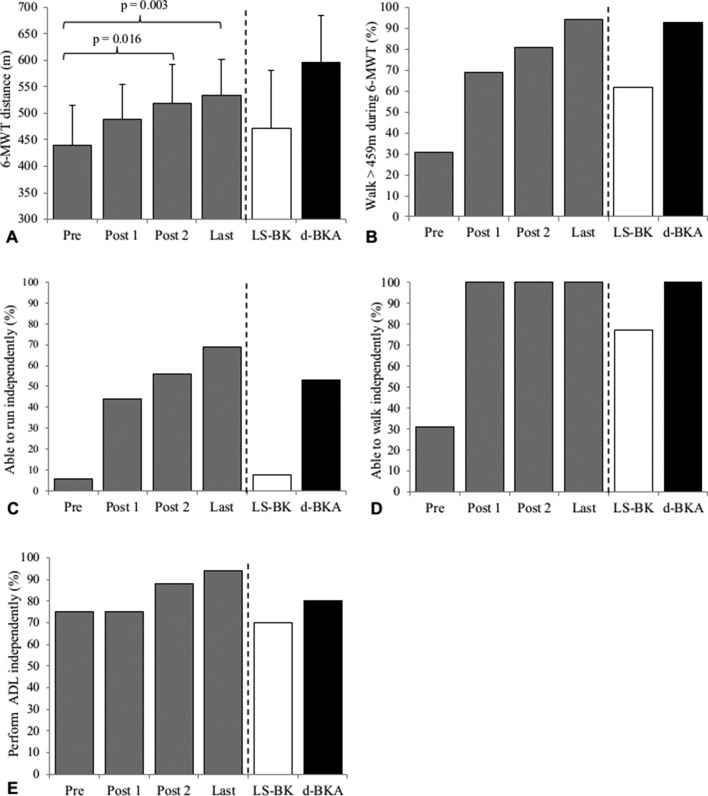

Twenty-three PDAFO users (58% response rate) received a mean 5±4 three-week admission prior to being supplied their PDAFO. Fourteen patients received at least one MDT rehabilitation admission after the provision of their PDAFO; nine did not receive any rehabilitation. The follow-up clinical outcomes questionnaire was completed a mean 34±11 months after being supplied the brace (MDT rehabilitation post-PDAFO=33±11 months, no rehabilitation=36±12 months). Baseline and follow-up data are provided in Table 2 and Figure 2. Prior to the provision of the brace, 74% of users (17 patients) were able to walk independently; this increased to 91% (21 patients) at follow-up. Before PDAFO, only 1 (4%) patient was able to run independently. At follow-up, 13 (57%) patients were able to run independently. The ability to run independently was greater in patients prescribed their PDAFO in combination with MDT rehabilitation (n=10, 71%) compared with no rehabilitation post-PDAFO provision (n=3, 33%). The mean depression and anxiety scores recorded pre-PDAFO and at follow-up are similar and are indicative of ‘no symptoms’ (p>0.05). There was a twofold increase in the number of patients reporting ‘no pain’ without the brace at follow-up (13%–31%). Patients who received MDT rehabilitation after PDAFO were better able to ‘control their pain’ when wearing and not wearing their brace compared with patients who did not receive rehabilitation after PDAFO fitting.

Table 2.

Medium-term psychosocial outcomes of passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO) users. Data present pre-PDAFO and >12 months of follow-up measures in (1) all users, (2) patients who received rehabilitation after PDAFO and (3) no rehabilitation after PDAFO. Data presented as mean, SD, range and percentages

| All patients | Received MDT rehabilitation post-PDAFO provision | Did not receive MDT rehabilitation post-PDAFO provision | ||||

| Preprovision admission | Follow-up | Preprovision admission | Follow-up | Preprovision admission | Follow-up | |

| n | 23 | 23 | 14 | 14 | 9 | 9 |

| Mental health outcomes | ||||||

| PHQ-9 (Depression) | 4±4 (0–19) |

4±4 (0–13) |

4±4 (0–12) |

3±3 (0–10) |

4±6 (0–19) |

4±5 (0–13) |

| <5 No symptoms (%) | 70 | 61 | 71 | 64 | 67 | 56 |

| >10 Moderate symptoms (%) | 13 | 13 | 14 | 7 | 11 | 22 |

| >15 Moderate to severe symptoms (%) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) | 4±5 (0–12) |

3±4 (0–13) |

4±4 (0–11) |

3±4 (0–13) |

4±6 (0–12) |

4±5 (0–8) |

| <5 No symptoms (%) | 70 | 70 | 71 | 71 | 67 | 67 |

| >10 Moderate symptoms (%) | 13 | 4 | 14 | 7 | 11 | 0 |

| >15 Severe symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Requires mental health support (%) | 22 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Pain | ||||||

| Not wearing the PDAFO | ||||||

| Report no pain (%) | 13 | 30 | 7 | 21 | 22 | 44 |

| Able to control pain (%) | 91 | 78 | 93 | 86 | 90 | 67 |

| Wearing the PDAFO | ||||||

| Report no pain (%) | – | 22 | – | 21 | – | 22 |

| Able to control pain (%) | – | 91 | – | 100 | – | 78 |

MDT, multidisciplinary team; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Figure 2.

Medium-term functional outcomes of passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO) users. Data present pre-PDAFO and >12 months of follow-up measures in (1) all users, (2) patients who received rehabilitation after PDAFO and (3) no rehabilitation after PDAFO. Panel (A) demonstrates the prevalence of PDAFO users able to run independently. Panel (B) demonstrates the prevalence of PDAFO users able to walk independently. Panel (C) demonstrates the prevalence of PDAFO users able to perform activities of daily living (ADL) independently. Data presented as mean and SD.

Longitudinal

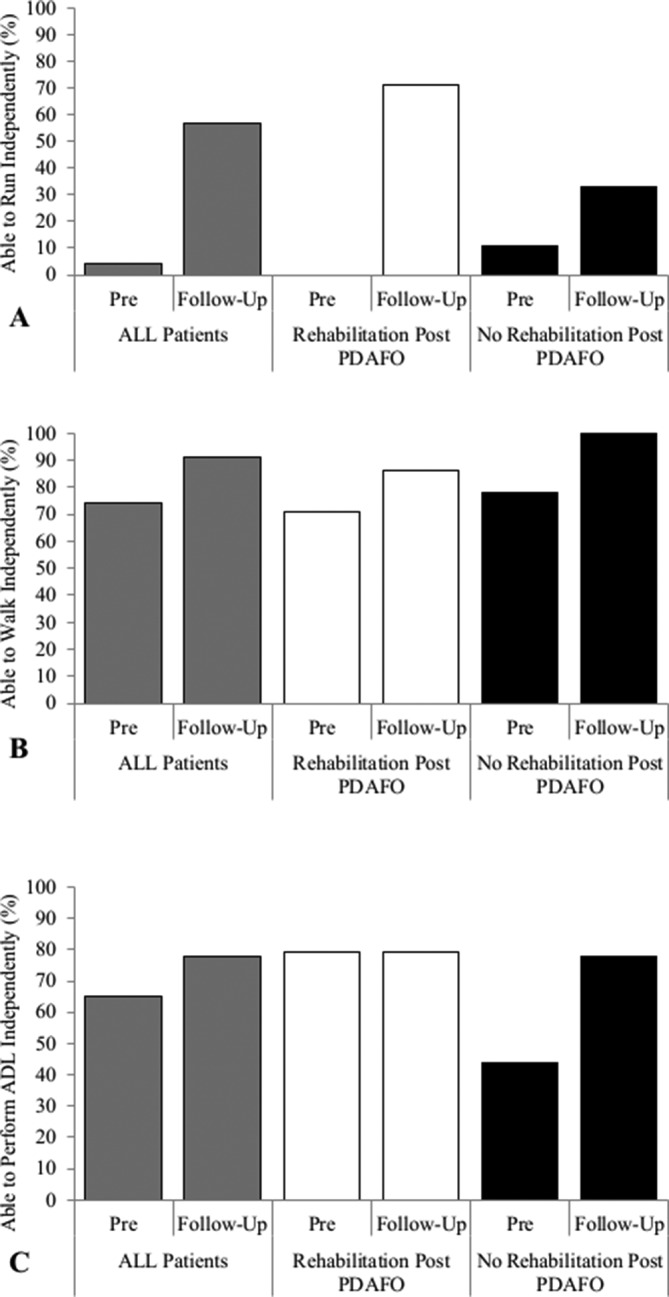

Sixteen patients received a minimum of two 3-week admissions. Their pre-PDAFO, first, second and final admission clinical outcomes are reported in Table 3 and Figure 3. Improvements in 6MWD were seen after PDAFO fitting at each admission (effect size range 11%–21%). In people with lower extremity injury, a minimal detectable change in 6MWD has been identified as 45 m.19 After one 3-week admission, mean 6MWD increased 48 m from 440±75 to 488±67 m (p>0.05). By the end of the second and final admissions significantly greater mean 6MWD was recorded (519±73 m, p=0.016 and 533±68 m, p=0.003; 73 and 93 m, respectively). The most notable difference in physical performance after wearing the PDAFO was the increased prevalence of patients able to run independently (Figure 3A). The ability to run increased from 6% to 44% after one 3-week admission; this pattern of progression continued to increase to 56% and 69% by the end of their second and final admissions, respectively. Before PDAFO, only 31% of patients could walk independently. By the end of the first admission, all patients could walk independently and there was a twofold increase in the number of patients able to walk speeds comparable with the general population (>459 m) in 6 min (31%–69%). Prior to the PDAFO being available to patients at DMRC, there was a significant difference in physical performance demonstrated at last admission between BK-LS and d-BKA. At the end of their final admission, the level of function demonstrated in PDAFO users was notably higher than previous BK-LS and more comparable to d-BKA groups. There were no significant changes in mean depression or anxiety over time (p>0.05) with mean scores between ‘3’ and ‘4’ indicating ‘no-symptoms’. ‘Moderate-symptoms’ of depression and anxiety reported pre-PDAFO provision were no longer demonstrated after the first and second admissions. There were no significant differences in mean depression or anxiety scores at last admission between PDAFO users, BK-LS and d-BKA (p>0.05). By the second admission, all PDAFO users were able to ‘control their pain’ and there was an incremental increase of patients reporting ‘no pain’ symptoms at last admission (6%–38%). This favourable pain status is comparable to d-BKA (40%) and is twofold greater than previous BK-LS (15%) groups.

Table 3.

Length of MDT rehabilitation and longitudinal changes in psychosocial outcomes of passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO) users who engaged in a minimum two inpatient rehabilitation admissions versus patients with previous traumatic lower extremity injury recorded at last admission, prior to the availability of the brace. Data present pre-PDAFO, first, second and last admissions post-PDAFO provision compared with previous below-knee limb salvage (BK-LS) and delayed below-knee amputees (d-BKA). Data presented as mean, SD, range and percentages

| Patients who engaged in the recommended guidelines of ≥2 inpatient MDT rehabilitation admissions wearing their PDAFO | Outcomes of patients with previous lower extremity trauma recorded at last admission prior to the availability of the PDAFO* | |||||

| Preprovision admission | First admission post-PDAFO provision | Second admission post-PDAFO provision | Last admission | BK-LS (last admission) |

d-BKA (last admission) |

|

| n | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 13 | 15 |

| MDT rehabilitation | ||||||

| Months of rehabilitation | 20±10 (3–42) |

1±2 (0–5) |

4±3 (2–8) |

10±9 (3–28) |

18±17 (3–58) |

19±8 (9–31) |

| Number of ~3 weeks of admissions | 6±4 (2–16) |

7±4 (3–17) |

8±4 (4–18) |

10±6 (5–19) |

8±6 (2–13) |

7±3 (4–13) |

| Mental health outcomes | ||||||

| PHQ-9 (Depression) | 4±4 (0–12) |

4±2 (0–7) |

3±3 (0–9) |

3±3 (0–8) |

4±5 (0–17) |

4±6 (0–19) |

| <5 No symptoms (%) | 75 | 50 | 69 | 81 | 77 | 60 |

| >10 Moderate symptoms (%) | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 20 |

| >15 Moderate to severe symptoms (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 7 |

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) | 4±4 (0–11) |

4±3 (0–11) |

3±3 (0–9) |

3±3 (0–9) |

3±5 (0–16) |

4±5 (0–14) |

| <5 No symptoms (%) | 75 | 69 | 63 | 69 | 69 | 67 |

| >10 Moderate symptoms (%) | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 20 |

| >15 Severe symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Requires mental health support (%) | 25 | 38 | 13 | 13 | 33 | 40 |

| Pain | ||||||

| Report no pain (%) | 6 | 13 | 31 | 38 | 15 | 40 |

| Able to control pain (%) | 88 | 88 | 100 | 100 | 85 | 93 |

MDT, multidisciplinary team; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

*Adapted from Ladlow et al.8

Figure 3.

Longitudinal changes in functional outcomes of passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis (PDAFO) users who engaged in a minimum two inpatient rehabilitation admissions against patients with previous traumatic lower extremity injury recorded at last admission prior to the availability of the brace. Data present pre-PDAFO, first, second and last admissions post-PDAFO provision compared with previous below-knee limb salvage (BK-LS) and delayed below-knee amputees (d-BKA). Panel (A) demonstrates the distance walked over 6 min. Panel (B) demonstrates the prevalence of PDAFO users able to walk >459 m (general population norms). Panel (C) demonstrates the prevalence of PDAFO users able to run independently. Panel (D) demonstrates the prevalence of PDAFO users able to walk independently. Panel (E) demonstrates the prevalence of PDAFO users able to perform activities of daily living (ADL) independently. Data presented as mean and SD (adapted from Ladlow et al 8). 6MWT, 6 min walk test.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the medium-term (mean 34±11 months) effect of a PDAFO on functional and psychosocial outcomes in patients with foot and ankle trauma. The results suggest that the provision of a PDAFO to patients presenting with lower extremity injuries commonly considered to demonstrate poor long-term clinical outcomes1 6 7 has contributed to lasting favourable results in a range of patient-reported measures. Improvements (and importantly, no deterioration) in mobility and pain status were demonstrated alongside unchanged levels of ‘none to minimal’ depression and anxiety and stable body mass index (27±3 kg·m2). In light of the historical evidence,1 2 5 6 the outcomes demonstrated here are highly significant. Blair et al 20 found that return-to-duty rates were increased in servicemen who received an integrated orthotic and rehabilitation programme (51%) compared with an IDEO brace alone (13%). Although return-to-duty rates were not measured, an integrated PDAFO and MDT rehabilitation approach facilitated higher levels of mobility and more favourable pain responses compared with PDAFO provision alone. It would be intuitive to propose that this increased prevalence of patients able to ‘walk and/or run independently’ with ‘controlled pain’ would heighten the probability of a patient finding employment after medical discharge.

The rehabilitation protocol used by the US military encouraged injured servicemen to complete 4 weeks of physical therapy without the orthosis (IDEO), followed by 4 weeks with it.10 Bedigrew et al 10 investigated the effect of an integrated IDEO and rehabilitation programme in a heterogeneous group of injured servicemen (lower extremity fractures, nerve injuries and arthritis) and reported no significant change in outcomes reported between weeks 0 and 4. However, significant improvements in physical performance, pain and patient-reported outcomes were demonstrated between weeks 4 and 8. Making direct comparisons between our findings and the above articles must be done with caution due to very different rehabilitation approaches and measurement tools; however, collectively both militaries report significant improvements in function and psychosocial outcomes when integrating a PDAFO with MDT rehabilitation.12 Our findings suggest PDAFO users who complete MDT rehabilitation are able to demonstrate comparable functional and pain responses to elective BKA with advanced prosthesis provision (Figure 3 and Table 3). This observation has recently been demonstrated by US military rehabilitation centres.21

The economic cost over 40 years of lower limb amputation is thought to be $350 465 compared with $133 704 for lower limb salvage surgery.22 Delayed amputation is also associated with higher numbers of revision surgical procedures, rates of infectious complications and non-healing wounds.23 24 With comparable clinical outcomes being demonstrated between lower limb amputees and limb salvage groups, healthcare providers may wish to review the cost-effectiveness of using assistive technology (like a PDAFO) prior to elective amputation in their patients with traumatic lower extremity.

In one US military rehabilitation centre, over 80% of patients treated with the IDEO avoided lower limb amputation within the first year.25 Six (9%) patients who had been prescribed the UK PDAFO later had elective amputation. Their injury characteristics and clinical outcomes are reported in the online supplementary file 2. This group demonstrated a significantly shorter 6MWD (370±61 m, p<0.05), greater mean depression and anxiety scores and an increased prevalence required mental health support in the admission prior to PDAFO provision than those who continued to manage with their PDAFO.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Of the 65 patients who received the brace we were only able to follow-up 40 patients, therefore, this may have skewed our finding. This further substantiates the importance for future research investigating the effectiveness and suitability of the PDAFO in injured UK military personnel. It lacks a control group or an alternative AFO making it challenging to assess the magnitude of improvement across all outcome measures. Baseline (pre-PDAFO fitting) measurement has however enabled patients to act as their own controls. Of note, all patients received MDT rehabilitation prior to their PDAFO fitting. The effect of this on clinical outcomes using the PDAFO is unknown. Despite differences in length of rehabilitation between patients, the eligibility criteria for a PDAFO meant relative levels of physical dysfunction and/or pain-related disability would be standardised across the group (all patients had reached a plateau in their level of function). The nature of combining PDAFO with intensive MDT rehabilitation may limit the external validity of these findings to civilian organisations and/or patients that either do not have the resources available to offer specialised rehabilitation or procure such a novel orthosis to their patients. However, some of the traumatic injuries presented in the PDAFO group are not dissimilar from what might be expected in civilian-based trauma caused by a high-energy mechanism such as a road traffic accident or a fall from a height. A pragmatic and appropriately tailored rehabilitation intervention could yield clinically meaningful improvements in patients who are motivated and have exhausted all other rehabilitation and medical methods to improve function and reduce distal lower extremity pain. Exploratory research into the capability of this PDAFO for both UK civilian and military personnel is encouraged.

Conclusion

The consequences of chronic pain and reduced physical function after lower extremity trauma may predispose an individual to live a more sedentary lifestyle, regardless of their preinjury activity levels. Strategies to increase physical function while reducing the development of chronic health disorders in disabled populations is a globally important issue. For young, previously active servicemen, the ability to remain physically active with manageable pain post-trauma is often a primary concern and aspiration. Prior to the provision of the US IDEO and UK PDAFO, both the US and the UK military reported significantly more favourable functional and psychosocial outcomes in their BKA compared with lower limb salvage.3 8 The introduction of this orthosis has altered the clinical decision-making landscape by enabling patients to attain higher levels of functional independence alongside reductions in pain comparable to BKA. The decision to proceed with limb salvage with a PDAFO could lead to advantageous and prolonged cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, mental health and vocational benefits for patients. Improvements in function, in combination with reductions in pain, are the ‘holy grail’ of any surgical and rehabilitation intervention. DMRC now considers the provision of this PDAFO an important component in the aftercare and management of patients with severe foot and ankle trauma and a viable alternative to elective below-knee amputation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jo Eldridge for her assistance as a research administrator overseeing the extraction of clinical outcomes from the Defence Medical Information Capability Programme (DMICP). We also thank the staff and patients within the Complex Trauma department at the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre (DMRC) whose hard work and effort made the outcomes presented within this manuscript possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: PL, NB, RP, SDD and ANB conceived the study design. PL, NB and LM collected data. PL performed the data analysis and all authors analysed and interpreted the findings. PL wrote the draft manuscript. All authors read, critically reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: NB is the developer of the orthosis and an employee of Blatchford. Blatchford supplies the orthosis to the UK Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre (DMRC) Headley Court and has commercial interests in the product. NB’s role is to fit the orthosis at DMRC. NB has no financial interests, patent or licensing agreements. NB did not perform any data analysis as part of the study. All remaining authors certify no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, and so on) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Due to privacy concerns, some data regarding participants are available but only to bona fide researchers working on a related project, subject to the completion of a non-disclosure agreement. Access requests for any restricted data should be sent to peter.ladlow100@mod.gov.uk.

References

- 1. Bennett PM, Stevenson T, Sargeant ID, et al. Outcomes following limb salvage after combat hindfoot injury are inferior to delayed amputation at five years. Bone Joint Res 2018;7:131–8. 10.1302/2046-3758.72.BJR-2017-0217.R2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF, et al. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation after leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1924–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa012604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doukas WC, Hayda RA, Frisch HM, et al. The Military Extremity Trauma Amputation/Limb Salvage (METALS) study: outcomes of amputation versus limb salvage following major lower-extremity trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:138–45. 10.2106/JBJS.K.00734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ. Factors influencing outcome following limb-threatening lower limb trauma: lessons learned from the Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP). J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006;14(10 Spec No.):S205–S210. 10.5435/00124635-200600001-00044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Pollak AN, et al. Long-term persistence of disability following severe lower-limb trauma. Results of a seven-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:1801–9. 10.2106/JBJS.E.00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramasamy MA, Hill CAM, Masouros S, et al. Outcomes of IED foot and ankle blast injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:e25–1-7. 10.2106/JBJS.K.01666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramasamy A, Hill AM, Phillip R, et al. The modern "deck-slap" injury--calcaneal blast fractures from vehicle explosions. J Trauma 2011;71:1694–8. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318227a999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ladlow P, Phillip R, Coppack R, et al. Influence of immediate and delayed lower-limb amputation compared with lower-limb salvage on functional and mental health outcomes post-rehabilitation in the U.K. military. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016;98:1996–2005. 10.2106/JBJS.15.01210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patzkowski JC, Blanck RV, Owens JG, et al. Can an ankle-foot orthosis change hearts and minds? J Surg Orthop Adv 2011;20:8–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bedigrew KM, Patzkowski JC, Wilken JM, et al. Can an integrated orthotic and rehabilitation program decrease pain and improve function after lower extremity trauma? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:3017–25. 10.1007/s11999-014-3609-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harper NG, Esposito ER, Wilken JM, et al. The influence of ankle-foot orthosis stiffness on walking performance in individuals with lower-limb impairments. Clin Biomech 2014;29:877–84. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Highsmith MJ, Nelson LM, Carbone NT, et al. Outcomes associated with the Intrepid Dynamic Exoskeletal Orthosis (IDEO): a Systematic Review of the Literature. Mil Med 2016;181(S4):69–76. 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsu JR, Owens JG, DeSanto J, et al. Patient Response to an Integrated Orthotic and Rehabilitation Initiative for Traumatic Injuries: the PRIORITI-MTF study. J Orthop Trauma 2017;31 Suppl 1:S56–S62. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ladlow P, Phillip R, Etherington J, et al. Functional and mental health status of united kingdom military amputees postrehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:2048–54. 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. ATSCoPSfCPF L, ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories . ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7. 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chetta A, Zanini A, Pisi G, et al. Reference values for the 6-min walk test in healthy subjects 20-50 years old. Respir Med 2006;100:1573–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Resnik L, Borgia M. Reliability of outcome measures for people with lower-limb amputations: distinguishing true change from statistical error. Phys Ther 2011;91:555–65. 10.2522/ptj.20100287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blair JA, Patzkowski JC, Blanck RV, et al. Return to duty after integrated orthotic and rehabilitation initiative. J Orthop Trauma 2014;28:e70–e74. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilken JM, Roy CW, Shaffer SW, et al. Physical performance limitations after severe lower extremity trauma in military service members. J Orthop Trauma 2018;32:183–9. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chung KC, Saddawi-Konefka D, Haase SC, et al. A cost-utility analysis of amputation versus salvage for gustilo type IIIB and IIIC open tibial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:1965–73. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bcf156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huh J, Stinner DJ, Burns TC, et al. Infectious complications and soft tissue injury contribute to late amputation after severe lower extremity trauma. J Trauma 2011;71(1 Suppl):S47–S51. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318221181d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Melcer T, Sechriest VF, Walker J, et al. A comparison of health outcomes for combat amputee and limb salvage patients injured in Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;75(2 Suppl 2):S247–S254. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318299d95e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hill O, Bulathsinhala L, Eskridge SL, et al. Descriptive characteristics and amputation rates with use of intrepid dynamic exoskeleton orthosis. Mil Med 2016;181(S4):77–80. 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jramc-2018-001082supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

jramc-2018-001082supp002.pdf (67.5KB, pdf)