Recently in Gut, a coding sucrase-isomaltase (SI) variant (15Phe at single nucleotide polymorphism rs9290264) with 35% reduced disaccharidase activity was reported to increase IBS risk and to correlate with more frequent stools. These observations were not assessed in relation to key dietary factors including carbohydrate (ie, SI substrates) consumption.1

Here, we studied two large German population-based cross-sectional cohorts, namely PopGen (n=639; average age 61.4; 44.8% female) and FoCus (n=759; average age 53.0; 58.5% female), with available genotype (genome-wide arrays), dietary (12-month food frequency questionnaire, FFQ), faecal microbiota (16S sequencing) and IBS status (self-reported from questionnaire) data, as previously described in detail.2–4

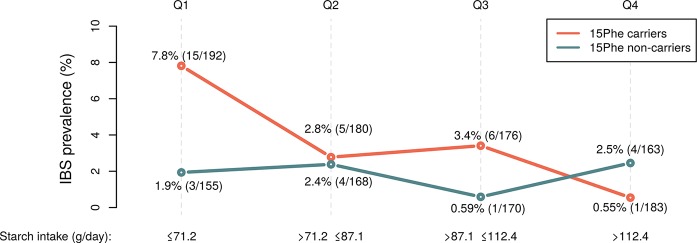

In a combined age/sex/body mass index (BMI)-adjusted logistic regression analysis of the two data sets, carriers of the 15Phe variant (52.86%) reported IBS significantly more often than non-carriers (3.69% vs 1.84%, respectively; P=0.044, OR=2.04), thus replicating and extending previous findings.1 When taking into account the consumption of SI substrate carbohydrates (polysaccharides and disaccharides; g/day) estimated from FFQ, this association appeared strongest for individuals with lowest intake (not shown). In particular, as illustrated in figure 1, starch was the individual carbohydrate component where the largest difference in IBS prevalence was observed between 15Phe carriers and non-carriers (7.8% vs 1.9%, respectively; P=0.029, OR=4.17). This suggests that 15Phe-driven genetic IBS risk effects may be better detectable in low-carbohydrate consumers (possibly driven by starch intake), where relative differences in SI enzymatic activity might have more pronounced consequences on the presence of symptom-generating undigested carbohydrates in the large bowel (compared with other intake groups, where colonic accumulation of undigested carbohydrates may result from higher intake irrespective of genotype).

Figure 1.

Sucrase-isomaltase (SI) 15Phe-driven IBS risk effects are stronger in low-starch consumers. The prevalence of IBS (%) across quartiles of starch intake (g/day) is reported, together with respective counts and number of individuals in each quartile group (Q1–Q4).

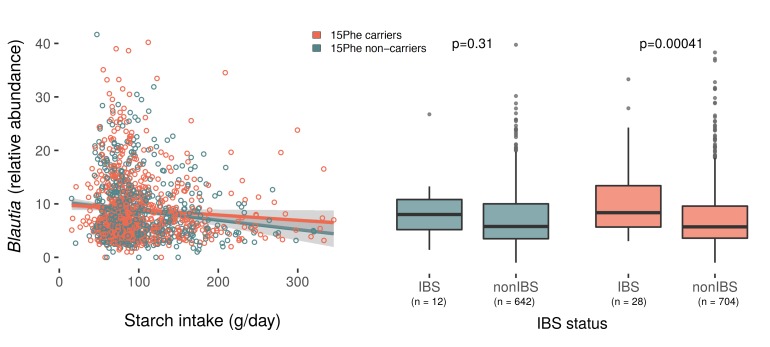

We then studied PopGen and FoCus faecal microbiota profiles in relation to carbohydrate consumption and SI 15Phe genotype. Expectedly, intake of polysaccharides (P=0.008), disaccharides (P=0.008), their sum (P=0.01) and starch (P=0.007) correlated with microbiota composition in an age/sex/BMI/total energy (TE)-adjusted multivariate analysis of variance model (mvabund/R using default settings, after excluding rare taxa with >95% zeros).5 Of note, similar effects were also observed when comparing 15Phe carriers with non-carriers (mvabund/R as above with genotype as covariate, P=0.016) irrespective of carbohydrate intake, thus suggesting SI genotype may be relevant to faecal microbiota composition. In order to gain further insight into the SI genotype-carbohydrate-microbiota interaction, we focused on 26 genera known to use intestinally available polysaccharides and disaccharides for their growth, namely ‘carb-digesters’ as defined and characterised previously by others.6 Although multiple testing correction returned no significant results, nominal trends for genotype-dependent starch-microbiota correlations were observed for Blautia, Oscillibacter, Ruminococcus and unclassified Enterobacteriaceae (typifying results for Blautia shown in figure 2). This is noteworthy, since similar changes in the relative abundance of most of these genera have been previously detected in patients with IBS.7–9 Of note, while we observed increased Blautia abundance in faecal samples from IBS cases also in our data set (generalised linear model age/sex/BMI/TE adjusted, P=0.00035, beta=0.66 vs controls), this was strongly affected by SI genotype and only significant in 15Phe carriers (P=0.00041, beta=0.80 vs P=0.31, beta=0.33 for non-carriers) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

15Phe genotype influences Blautia faecal abundance. (Left) Genotype-stratified correlation between starch intake and Blautia faecal microbiota abundance (each circle represents an individual). A trend was identified when comparing the two sucrase-isomaltase (SI) 15Phe genotype groups for their starch-bacteria correlations (age/sex/body mass index (BMI)/total energy (TE)-adjusted generalised linear model (GLM) with negative-binomial distribution, and interaction term for genotype and starch intake), in that increasing starch intake corresponds to higher Blautia abundance in 15Phe carriers compared with non-carriers (uncorrected P=0.054). (Right) Blautia faecal microbiota abundance in the two SI genotype groups stratified according to IBS status was significantly increased in IBS cases carrying the 15Phe variant (P=0.00041, beta=0.80), while there was no significant association in non-carriers (P=0.31, beta=0.33). Association analysis was performed using GLM age/sex/BMI/TE adjusted (glm.nb in stats/R). Plots were made using ggplot in ggplot2/R with stat_smooth and method=lm (left panel), and square root transformation of Blautia relative abundance (right panel).

In conclusion, we report here preliminary evidence linking the IBS-associated SI 15Phe variant to detectable diet-mediated effects on faecal microbiota composition and IBS risk. This adds to previous findings, and warrants further studies of the complex SI genotype-dietary carbohydrate-microbiota interactions in order to infer causality in relation to overall risk of IBS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Ilona Urbach, Ines Wulf and Tonio Hauptmann of the IKMB microbiome laboratory for excellent technical support.

Footnotes

AF and MD’A contributed equally.

Contributors: LT and MDA: study concept and design. WL and ML: data acquisition. LT, MR, JW and MH: statistical analyses. LT and MDA: data analysis and interpretation. AF and MDA: obtained funding, administrative and technical support, and study supervision. MDA drafted the manuscript, with input and critical revision from all other authors. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) programme e:Med sysINFLAME (http://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/5111.php, no: 01ZX1306A), the Swedish Research Council (VR 2013-3862) to MDA, and received infrastructure support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Cluster of Excellence 306 ‘Inflammation at Interfaces’ (http://www.inflammation-at-interfaces.de, no: EXC306 and EXC306/2) and from the PopGen Biobank (Kiel, Germany).

Competing interests: MDA has received unrestricted research grants from QOL Medical.

Ethics approval: Institutional ethical review committee for the PopGen Biobank.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Henström M, Diekmann L, Bonfiglio F, et al. Functional variants in the sucrase-isomaltase gene associate with increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2018;67:263–70. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krawczak M, Nikolaus S, von Eberstein H, et al. PopGen: population-based recruitment of patients and controls for the analysis of complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Community Genet 2006;9:55–61. 10.1159/000090694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Müller N, Schulte DM, Türk K, et al. IL-6 blockade by monoclonal antibodies inhibits apolipoprotein (a) expression and lipoprotein (a) synthesis in humans. J Lipid Res 2015;56:1034–42. 10.1194/jlr.P052209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang J, Thingholm LB, Skiecevičienė J, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variation in vitamin D receptor and other host factors influencing the gut microbiota. Nat Genet 2016;48:1396–406. 10.1038/ng.3695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yi Wang UN, Wright S, Warton DI. mvabund: an R package for model-based analysis of multivariate data. Methods Ecol Evol 2012:471–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vieira-Silva S, Falony G, Darzi Y, et al. Species-function relationships shape ecological properties of the human gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol 2016;1:16088 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Labus JS, Hollister EB, Jacobs J, et al. Differences in gut microbial composition correlate with regional brain volumes in irritable bowel syndrome. Microbiome 2017;5:49 10.1186/s40168-017-0260-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rajilić-Stojanović M, Biagi E, Heilig HG, et al. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1792–801. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rajilić-Stojanović M, Jonkers DM, Salonen A, et al. Intestinal microbiota and diet in IBS: causes, consequences, or epiphenomena? Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:278–87. 10.1038/ajg.2014.427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]