Abstract

This study aimed to screen phytochemical components and antioxidant activity of Balanites aegyptiaca ethanolic extract (BAF-EE) as well as to evaluate its curative effect on experimentally induced haemonchosis in goats. Phytochemical constitutes of BAF-EE were screened and identified using Gas Chromatography–mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis and antioxidant effect was determined. Infective third larval stage (L3) of Haemonchus contortus (H. contortus) were obtained by culturing feces of goat harboring monospecific infection of the parasite. Twelve male goats were randomly divided into four groups (n = 3) as: G1 (infected—untreated) which served as control positive, G2 (infected—BAF-EE treated), G3 (infected-albendazole treated) and G4 (uninfected—BAF-EE treated) that served as control negative. Experimental infection was conducted with a single oral dose of 10,000 L3 at 0-time, whereas treatment with BAF-EE and albendazole were given at a single oral dose of 9 g and 5 mg/kg BW, respectively in the 5th week post infection (PI). Egg count per gram of feces (EPG) was conducted once a week and blood samples were drawn on zero time, 3rd week PI and then biweekly for 9 weeks, for conduction of hemogram. At the end of the experiment, all animals were slaughtered and adult worms in their abomasa were counted. GC–MS analysis confirmed 28 compounds in the extract which revealed presence of saponins, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics and alkaloids, and exhibited in vitro antioxidant activity. Clinical signs observed on the infected animals were signs of anemia, which were gradually disappeared post treatment (PT). A maximum reduction in EPG (88.10%) and worm burden (94.66%) was recorded on 4th week PT due to efficacy of BAF-EE in contrast to 98.29% and 96.95% efficacy of albendazole. All infected groups showed a significant decrease in hemoglobin (Hb) and packed cell volume (PCV) and presence of microcytic hypochromic anemia compared with G4. Goats treated with B. aegyptiaca and albendazole, exhibited significant increase in Hb and PCV 2 weeks PT and anemia changed to be normocytic hypochromic or microcytic normochromic in G2 and G3, respectively. Total white blood cells (WBCs) were elevated significantly in all infected groups which attributed to increase in lymphocytes, monocytes and eosinophils on expense of neutrophils. After treatments, WBCs and previously mentioned cells tended to decease. This study demonstrated that BAF-EE has anthelmintic effect against H. contortus and can improve hemogram and health condition of infected goats.

Keywords: Haemonchosis, Goats, Experimental infection, Balanites aegyptiaca, Anthelmintic activity, Hemogram

Introduction

Baladi goats (Capra hircus) are famous breed of goats that are reared throughout in Egypt and have an important role in the livelihood of small, marginal farmers and landless labourers in rural Egypt (El-Halawany et al. 2017). The husbandry practices adopted by the farmers in rural Egypt predispose goats to gastrointestinal nematodes infection that causes huge economic losses.

Amongst gastro-intestinal nematodes of small ruminants, H. contortus is the highly pathogenic predominant species (Elshahawy et al. 2014; Brik et al. 2019). Infection of goats with H. contortus has a great effect on their health, causing anemia, loss of body weight and productivity (Al-Jebory and Al-Khayat 2012). In acute form of haemonchosis, the main pathological lesion caused by H. contortus infection is anemia and progressive dramatic fall in PCV which causes increase inappetence, the bone marrow eventually exhausted due to continuous loss of iron and proteins in the gastrointestinal tract that may result in death (Rouatbi et al. 2016; Mannan et al. 2017). Both adult and infective stage larvae suck blood and cause haemorrhages during their migration into the abomasum (Urquhart et al. 1996). The average blood loss due to H. contortus infection is 0.03 ml/parasite/day (Awad et al. 2016).

Control of H. contortus often depends upon the use of anthelmintic drugs and widespread intensive use, under-dosing or poor quality drugs led to development of a high level of multiple anthelmintic resistances in developing countries (Waller 1997; Shalaby 2013). Furthermore, the high cost of these drugs together with the residual concern in food animals and the risk of environmental pollution have awakened interest in medicinal plants as an alternative source of anthelmintic drugs (Hördegen et al. 2003; Githiori et al. 2004; Albadawi 2010).

Balanites aegyptiaca Del. (L.) (Family: Balanitaceea) also known as “desert date”, is a spiny tree of up to 10 m in height, distributed in Africa and South Asia (Chothani and Vaghasiya 2011). The fruits of this plant are used as folk medicine in the treatment of various diseases such as intestinal worm infestations, wound healing, syphilis, dysentery, constipation, diarrhea and fever (Doughari et al. 2007; Vijigiri and Sharma 2010). The fruit of B. aegyptiaca is known to contain a wide variety of compounds, which show a wide range of biological and pharmacological properties such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities (Chothani and Vaghasiya 2011). The fruits are commonly used to purge intestinal parasites and have been found to be effective against Fasciola gigantica, Schistosoma mansoni (Koko et al. 2000, 2005) and Trichinella spiralis (Shalaby et al. 2010). Besides, fruits have remarkable anti parasitic potential against H. contortus in lambs (Albadawi 2010; Hassan 2014). The fruit is edible, yields valuable oil and also contains saponins which are lethal to certain invertebrates (Chapagain and Wiesman 2008) and thus may be of value in eliminating helminthes.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the curative anthelmintic suppressant effects of the medicinal plant B. aegyptiaca fruit’s mesocarp ethanolic extract on experimentally induced H. contortus infection in Egyptian Baladi goats compared to albendazole as a classical used broad spectrum anthelmintic. Evaluation of clinical signs, fecal egg count, worm burden in the abomasa and alterations of the hemogram of goats were considered in this paper.

Materials and methods

Fruit procurement and BAF-EE preparation

A required quantity of B. aegyptiaca fruits (Fig. 1) was purchased from a local market in Upper Egypt and was authenticated scientifically at the department of medicinal plants, NRC, Egypt. The ethanolic extract of the fruits’ mesocarp (BAF-EE) was prepare following the method described by Wang and Weller (2006). The fruit mesocarp was macerated several times with 70% ethyl alcohol at room temperature for 1 week then filtered. The solvent was removed under vacuum at 40 °C by rotary evaporator and the extract was stored at − 4 °C.

Fig. 1.

Balanites aegyptiaca fruits

Phytochemical composition of BAF-EE

GC–MS analysis

The phytochemical composition of the BAF-EE was determined using GC–MS method: GC (Agilent Technologies 7890A) interfaced with a mass-selective detector (Agilent 7000 Triple Quad) and Agilent HP-5 ms capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID and 0.25 µm film thickness) were used. The flow rate was 1 ml/min. The injector and detector temperatures were 200 °C and 250 °C, respectively. The acquisition mass range was 50–600. The formulae of the components as identified by comparing their mass spectra and retention time (RT) with those of NIST and WILEY library were recorded.

Phytochemical screening

Qualitative phytochemical tests were carried out on the BAF-EE using modified and standard methods (Obasi et al. 2010; Tiwari et al. 2011). The phytochemical components screened included saponins, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics and alkaloids.

In vitro total antioxidant activity of BAF-EE

The in vitro total antioxidant effect of BAF-EE was determined by the Phospho-molebdenum method (Prieto et al. 1999) using ascorbic acid as standard. Results were expressed as milligram ascorbic acid equivalent per 100 ml (mgAAE/100 ml).

Assessment of BAF-EE anthelmintic efficacy on H. contortus parasite

Reference anthelmintic drug

Albendazole (Evazole®, in the form of 2.5% oral suspension), a known broad spectrum anthelmintic, was purchased from the Veterinary Division of EVA Pharma, Cairo, Egypt and used for treatment of one experimental group (G3) to be compared with the anthelmintic efficacy of BAF-EE.

Genesis of infective larval dose of H. contortus parasite (L3)

Adult females of H. contortus parasites were identified and collected from the abomasa of sheep randomly slaughtered at Moneb abattoir, Cairo, Egypt. A suitable fecal culture as described by Roberts and O’Sullivan (1950) was prepared using eggs of the collected worms to generate L3 of H. contortus as follow. The required eggs were released from the gravid uteri by crushing the collected worms using a pestle and mortar. The resultant homogenate was then mixed with crushed sheep feces that were sterilized by heating at 140 °C for 2 h. The culture was kept at room temperature ranging between 30 and 35 °C for 7 days. L3 of the parasite were obtained from the culture by means of Baerman Wetzal funnel technique (Baerman and Wetzal 1953; Soulsby 1982). The confirmatory identification of the larvae as L3 was carried out according to the method described by Soulsby (1982). Based on the guidelines published by the ‘Ministry of Agriculture (U.K.), Fisheries and Food; Agricultural Development and Advisory Service (1979)’, the actively motile larvae were counted and their number in the total amount of solution was obtained using the following formula.

A goat kid free from internal parasites was inoculated orally with a dose of 10, 000 L3 in 10 ml physiological saline solution as recommended by Howlader et al. (1997) and Hassan (2014) and kept as donor animal. Subsequently, the donor animal was used as source for getting monospecific L3 for infection of goats of the experimental groups.

Experimental animals

Twelve male, apparently healthy, 6–9 months old, Egyptian Baladi goats, weighing 15–20 kg were used. The animals were kept in door in a barn at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University and fed equally on a balanced concentrate ration at a rate equivalent to 1% of their live body weight. Animals were offered fresh tape water ad libitum and kept under close observation for 30 days to acclimate before experimentation. During this period, the animals received a standard oral dose of anticoccidial drug (Sulphadimidine 33%, Pharma Swede/Egypt), a dose of multivitamins (Univet, Ireland) and an injectable prophylactic dose of a long acting antibiotic (Oxytetracyclin 20%, Avicyclin, Avico) at a dose of 1 ml/10 kg BW. Examination of the animals’ feces was performed during three consecutive weeks, and the animals were proven to be free from internal parasites before the onset of the experiment (Wood et al. 1995).

Experimental design

After the acclimatization period, the goat kids were allocated into 4 experimental groups (each of three animal), as G1, G2, G3, and G4. Animals of G1, G2 and G3 were infected orally, each with 10,000 L3 on zero experimental day. Goats of G1 were left untreated and considered control positive group. Goats of G2 received a single oral dose of BAF-EE at the rate of 9 g/kg BW on the 5th week PI, while goats of G3 were treated with albendazole at the rate of 5 mg/kg BW on the 5th week PI. Animals of G4 were administrated BAF-EE at the rate of 9 g/kg BW on the 5th week PI and kept as control negative group. Every group of the experimental animals was kept isolated in a separated ban during the period of the experiment which persisted for 9 weeks.

Assessing the efficacy of treatments

Fecal egg count

On the 15th day PI and onwards, fresh fecal samples were collected directly from rectum of each animal once a week for 9 weeks into clean plastic bags and examined for H. contortus eggs using concentration floatation technique (Soulsby 1982). The eggs were identified on the basis of their morphological features (Thienpont et al. 1980). Fecal egg count was performed using Modified Mac-Master technique and the number of eggs per gram of feces (EPG) was determined using the following equation:

Fecal egg count reduction percent (FECR %) was calculated using the following formula as adapted by Tariq et al. (2009).

Evaluation of the adult worm burden in the abomasa

At the end of the experiment (on week 9th), all animals were slaughtered and adult worms in their abomasa were counted per animal. The efficacy of the drug and BAF-EE was assessed by the following formula:

Hemogram assays

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein of each animal into vacutainer tubes containing ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) as anticoagulant, at zero-time of the experiment, and at the 3rd week PI, then every 2 weeks PI until the end of the experiment. Hematological parameters were evaluated according to Weiss and Wardrop (2010), using a hematological analyzer (Exigo Vet, Sweden). It included the red blood cell count (RBCs), packed cell volume (PCV), hemoglobin (Hb) concentration, calculated red blood indices [Mean corpuscular volume (MCV), Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC)], total white blood cells (WBC) and differential leukocytic counts.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SE. Differences between means in the different groups were tested for significance by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple range tests to detect the significance among means in between different experimental groups and weeks (Snedecore and Cochran 1984). SPSS (version 16) computer program was used.

Results

Phytochemical composition of BAF-EE

The GC–MS analysis revealed 28 different compounds in the extract of crude BAF-EE (Table 1). The compound shown with the highest percentage (47.49%) was α-Methylcaproic acid. Those shown more than 5% were 3,4,5-Trimethoxycinnamic acid and 4-Mercaptophenol, while Pentadecanoic acid, Endo-Borneol, 3,4-Dimethoxy-2,hydroxychalcone, Butanoic acid, 3-hydroxy-, Lactose, Hexa-hydro-farnesol, Nonanoic acid, Palmitic acid, Elcosanoic acid, Heptadecanoic acid, 3-(3,4- Dimethoxyphenyl)-4-methylcoumarin, Glyceryl Monooleate, 1-Tricosanol and (S)-(-)-Citronellic acid were shown to only be more than 1%.

Table 1.

GC–MS analysis of B. aegyptiaca fruit’s mesocarp ethanolic extract

| No. | RT (min) | Name | Area sum (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.168 | 3,4,5-Trimethoxycinnamic acid | 5.85 |

| 2 | 3.441 | Pentadecanoic acid | 1.07 |

| 3 | 4.297 | Endo-borneol | 1.81 |

| 4 | 5.054 | Linoleic acid | 0.72 |

| 5 | 5.282 | 3,4-Dimethoxy-2, hydroxychalcone | 1.08 |

| 6 | 5.572 | 7-Hydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4-methylcoumarin | 0.67 |

| 7 | 5.604 | 17-Octadecynoic acid | 0.81 |

| 8 | 6.313 | Butanoic acid, 3-hydroxy- | 2.04 |

| 9 | 7.054 | Undecanoic acid | 0.89 |

| 10 | 8.008 | Lactose | 3.28 |

| 11 | 8.749 | Oleic acid | 0.7 |

| 12 | 9.364 | 4-Mercaptophenol | 8.15 |

| 13 | 10.187 | Hexa-hydro-farnesol | 1.82 |

| 14 | 11.381 | Nonanoic acid | 3.33 |

| 15 | 11.654 | Palmitic acid | 2.47 |

| 16 | 12.334 | Elcosanoic acid | 1.76 |

| 17 | 12.509 | α-Methylcaproic acid | 47.49 |

| 18 | 13.719 | Stearic acid | 0.91 |

| 19 | 13.817 | Heptadecanoic acid | 1.12 |

| 20 | 14.835 | Erucic acid | 0.76 |

| 21 | 15.931 | Vitexin | 0.72 |

| 22 | 16.77 | 2-Hexadecanol | 0.7 |

| 23 | 17.85 | Geranyl isovalerate | 0.83 |

| 24 | 19.158 | Stigmasterol | 0.66 |

| 25 | 20.254 | 3-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-4-methylcoumarin | 1.17 |

| 26 | 21.403 | Glyceryl monooleate | 4.19 |

| 27 | 22.063 | 1-Tricosanol | 2.63 |

| 28 | 23.049 | (S)-(-)-Citronellic acid | 2.38 |

Phytochemical screening of the crude BAF-EE revealed presence of saponins, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolic compounds and alkaloids.

In vitro total antioxidant activity of BAF-EE

The crude BAF-EE exhibited a strong antioxidant effect as 2128.86 mg/100 gm (ascorbic acid equivalent).

Clinical observations

No clinical signs were observed in uninfected-BAF-EE treated goats (G4) during the experimental period, while goats of all infected groups (G1, G2, G3) exhibited less or more severe signs of haemonchosis such as weakness, lack of appetite, lethargy, pale conjunctiva (Fig. 2), mushy stools (but not diarrhea) and increased heart rate and breathing. Symptoms started to appear at the 3rd week PI and were most pronounced at the 5th week PI. After this period, clinical signs were gradually disappeared in G2 and G3 animals which received treatment with BAF-EE or albendazole, respectively. Gradual improvement of the general condition occurred and the animals appeared healthy at the end of the experiment compared with the untreated control group (G1).

Fig. 2.

Pale conjunctiva in a goat kid experimentally infected with H. contortus

No evidences of toxicity or abnormal behavioral changes were recorded during or after treatment with the experimental dose of plant extract.

Parasitological findings

Egg counts per gram of feces (EPG)

None of the G4 goats (uninfected-BAF-EE treated) voided eggs in their feces throughout the experimental period. In all infected groups, egg voidance started on the 3rd week PI. The average count of EPG of G1, G2 and G3 animals is shown in Table 2. Infected-treated animals showed gradual reduction in EPG of feces from the first week after treatment, especially goats of G3 treated with albendazole, when compared with counts of G1 infected-untreated animals.

Table 2.

Egg count per gram of feces (EPG) in different infected groups of goats

| Week (PI) | G1 | G2 | G3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3rd | 83.33 ± 5.24 | 60.00 ± 15.01 | 58.67 ± 15.30 |

| 4th | 95.33 ± 10.20 | 88.33 ± 4.84 | 90 ± 10.49 |

| 5th | 95.00 ± 4.93 | 87.67 ± 2.91 | 91 ± 9.53 |

| 6th | 97.33 ± 6.74a | 21.67 ± 2.85b | 9.5 ± 1.15c |

| 7th | 88.17 ± 11.83a | 10.00 ± 0.58b | 3.50 ± 0.67c |

| 8th | 87.33 ± 8.65a | 9.7 ± 2.03b | 1.33 ± 0.33c |

| 9th | 82.00 ± 9.86a | 10.33 ± 1.20b | 1.50 ± 0.33c |

Values with different superscripts a, b, c in the same row are significantly different at (P ≤ 0.05)

G1: Goats infected—untreated and expressed as control positive

G2: Goats infected and treated with BAF-EE

G3: Goats infected and treated with albendazole

The FECR % is shown in Table 3. Both G2 and G3 infected—treated goats exhibited a significant (P ≤ 0.05) anthelmintic activity from the first week PT until the end of the experiment compared with G1 animals. Reduction in fecal egg count recorded on the 4th week PT was 88.10% and 98.29% for G2 and G3 goats, respectively. A significant (P ≤ 0.05) difference was observed between FECR % of G2 and G3.

Table 3.

Fecal egg count reduction percent (FECR %) in goats after treatment with B. aegyptiaca or albendazole in comparison with infected-untreated goats

| Treatments | Weeks post treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | |

| Control positive (G1) | − 2.78% ± 1.50a | 9.91% ± 8.05a | 8.71% ± 4.42a | 14.17 ± 6.16a |

| B. aegyptiaca (G2) | 75.08% ± 4.08b | 88.70% ± 0.97b | 88.83% ± 2.55b | 88.10 ± 1.53b |

| Albendazole (G3) | 89.58% ± 0.32c | 95.93% ± 1.07c | 98.54% ± 0.05c | 98.29 ± 0.37c |

Mean ± SE

Means with different superscripts a, b, c in the same column are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05

Total adult H. contortus burden

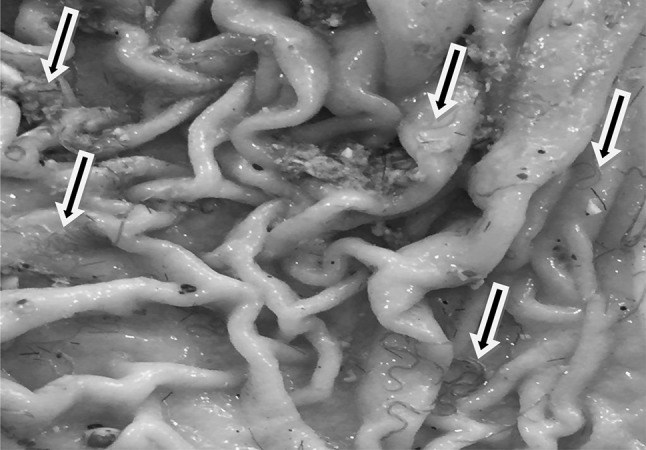

No worms were detected in the abomasa and duodenums of G4 animals on postmortem examination. Mean values of total adult H. contortus parasites released from the abomasa (Fig. 3) of G1, G2, and G3 infected goats are presented in Table 4. A maximum reduction in worm burden (94.66%) in the abomasa was recorded on 4th week PT due to the anthelmintic efficacy of BAF-EE in contrast to 96.95% efficacy of albendazole. A significant (P ≤ 0.05) reduction in total worm burden was recorded in both G2 (18.67 worms) and G3 (10.67 worms), when compared with G1 infected-untreated group (350 worms). The mean number of worms in G3 received albendazole was significantly lower than that of G2 treated with BAF-EE.

Fig. 3.

H. contortus worms in the abomasum of experimentally infected goat (arrows)

Table 4.

Total number of adult H. contortus worms in the abomasa of different infected groups and the efficacy of B. aegyptiaca and albendazole

| Infected-untreated group (G1) | B. aegyptiaca treated group (G2) | Albendazole treated group (G3) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE |

| 350 ± 38.19a | 18.67 ± 4.91b | 10.67 ± 1.45c |

| (94.66%) | (96.95%) |

Values with different superscripts a, b, c in the same row are significantly different at (P ≤ 0.05)

Hematological findings

Erythrogram

Results of the erythrogram are shown in Table 5. Erythrogram parameters of goats in the uninfected -BAF-EE treated G4 were found to fluctuate within the normal range throughout the experimental period.

Table 5.

Erythrogram of goats experimentally infected with H. contortus affected by different treatments during the experimental period

| Parameters | Groups | Weeks post infection (PI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3rd | 5th | 7th | 9th | ||

| RBCs (× 106/µl) | G1 | 14.12 ± 0.08a | 14.64 ± 0.37ab | 15.00 ± 0.14b | 15.77 ± 0.16Cc | 14.88 ± 0.21b |

| G2 | 13.95 ± 0.25 | 15.09 ± 0.56 | 14.45 ± 0.69 | 13.28 ± 0.12A | 13.97 ± 0.49 | |

| G3 | 14.13 ± 0.34 | 15.14 ± 0.42 | 14.84 ± 0.70 | 14.47 ± 0.28B | 14.49 ± 0.18 | |

| G4 | 13.96 ± 0.26ab | 13.6 ± 0.18a | 14.31 ± 0.11b | 14.93 ± 0.15Bc | 14.22 ± 0.36bc | |

| PCV (%) | G1 | 27.00 ± 0.46c | 25.40 ± 0.78Ab | 23.35 ± 0.08Aa | 22.75 ± 0.14Aa | 20.75 ± 1.24Ad |

| G2 | 26.96 ± 0.49b | 24.16 ± 0.44Aa | 24.70 ± 0.31Aa | 26.46 ± 0.39CBb | 25.58 ± 0.39Bab | |

| G3 | 27.10 ± 0.23c | 24.33 ± 0.59Aa | 24.10 ± 0.17Aa | 25.20 ± 0.40Bb | 25.18 ± 0.37Bb | |

| G4 | 26.35 ± 0.20a | 27.10 ± 0.12Ba | 26.70 ± 0.75Ba | 28.45 ± 0.19Db | 27.15 ± 0.49Cba | |

| Hb (g/dl) | G1 | 9.00 ± 0.23c | 6.90 ± 0.02Ab | 6.15 ± 0.48Aa | 5.65 ± 0.14Aa | 6.93 ± 0.39Ab |

| G2 | 9.20 ± 0.43c | 6.93 ± 0.41Aa | 6.67 ± 0.36Aa | 8.40 ± 0.20Bbc | 8.03 ± 0.29Bc | |

| G3 | 9.05 ± 0.08d | 6.75 ± 0.08Aa | 6.30 ± 0.21Aa | 8.20 ± 0.17Bc | 7.90 ± 0.26Bc | |

| G4 | 8.65 ± 0.08a | 8.75 ± 0.33Ba | 8.95 ± 0.43Ba | 9.30 ± 0.05Cc | 8.9 ± 0.18Cac | |

| MCV(fl) | G1 | 19.14 ± 0.21d | 17.36 ± 0.54Ac | 15.56 ± 0.21Ab | 14.43 ± 0.24Aa | 13.57 ± 0.81Aa |

| G2 | 19.34 ± 0.62b | 16.03 ± 0.35Aa | 17.15 ± 0.84Bac | 19.93 ± 0.36Db | 18.40 ± 0.50Bbc | |

| G3 | 19.21 ± 0.29c | 16.09 ± 0.32Aa | 16.29 ± 0.16ABa | 17.42 ± 0.06Bb | 17.42 ± 0.36Bb | |

| G4 | 18.88 ± 0.22 | 19.82 ± 0.18C | 18.64 ± 0.38C | 19.06 ± 0.25C | 19.10 ± 0.18C | |

| MCH (pg) | G1 | 6.38 ± 0.13d | 4.71 ± 0.04Ac | 4.10 ± 0.09Ab | 3.58 ± 0.13Aa | 4.69 ± 0.12dA |

| G2 | 6.61 ± 0.43c | 4.58 ± 0.12Aa | 4.65 ± 0.47Aa | 6.33 ± 0.15Cbc | 5.78 ± 0.16BCc | |

| G3 | 6.41 ± 0.09b | 4.46 ± 0.06Aa | 4.50 ± 0.27Aa | 5.66 ± 0.01Bc | 5.47 ± 0.11Bc | |

| G4 | 6.20 ± 0.05 | 6.40 ± 0.12B | 6.25 ± 0.06B | 6.23 ± 0.09C | 6.27 ± 0.14C | |

| MCHC (g/dl) | G1 | 33.32 ± 0.28c | 27.16 ± 0.14Ab | 26.34 ± 0.27Bb | 24.82 ± 0.47Aa | 26.63 ± 0.73Ab |

| G2 | 34.09 ± 1.23c | 28.64 ± 1.16Aa | 27.01 ± 0.37Ba | 31.73 ± 0.32Bb | 31.28 ± 0.71Bb | |

| G3 | 33.39 ± 0.13b | 27.74 ± 0.14Aa | 27.53 ± 0.90Ba | 31.55 ± 0.94Bb | 31.30 ± 0.68Bb | |

| G4 | 32.83 ± 0.17 | 32.29 ± 0.24B | 33.61 ± 1.05C | 32.68 ± 0.10B | 32.85 ± 0.37B | |

Mean ± SE

Values with different superscripts A, B, C, D in the same column (among groups) and a, b, c, d in the same row (within groups) are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05

G1: Goats infected—untreated and expressed as control positive

G2: Goats infected and treated with BAF-EE

G3: Goats infected and treated with albendazole

G4: Goats uninfected and dosed with BAF-EE and expressed as control negative

There were no significant differences in total RBCs count within and/or among experimental groups except on the 5th and 7th weeks PI, where counts were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) high in infected-untreated control positive (G1) goats and at the 3rd week PI in infected-treated G2 and G3 goats compared to 0 time values.

A progressive significant (P ≤ 0.05) decline in PCV was observed in G1 goats throughout the experiment. PCV percentages in goats of BAF-EE treated group (G2) decreased significantly (P ≤ 0.05) at the 3rd and 5th weeks PI, then returned after treatment to 0 time values at the 7th and 9th weeks PI. PCV percentages of albendazole treated group (G3) were decreased significantly (P ≤ 0.05) from the 3rd to the 9th week PI compared to 0 time values. After treatment, there were significant (P ≤ 0.05) elevation in PCV values at the 7th and 9th weeks PI in goats of G2 and G3 compared to G1 goats, while significant (P ≤ 0.05) depression was observed compared to those in G4.

Hemoglobin values of goats in G1 showed significant decrease (P ≤ 0.05) starting from the 3rd week PI and thereafter till the end of the experiment. Hemoglobin concentration in infected-treated groups (G2 and G3) showed significant decline on the 3rd and 5th weeks PI compared to 0 time values, after which, at the 7th and 9th weeks PI, Hb values were elevated to be comparable with 0 time values in G2 and slightly lower than 0 time values in G3. No significant differences were observed in Hb values among both G2 and G3 PT.

Studying red blood cell indices (Table 5) of G1 goats revealed occurrence of anemia of the microcytic hypochromic type throughout the experiment. A microcytic hypochromic anemia also was observed in goats of G2 and G3 at the 3rd and 5th weeks PI, which changed at the 7th and 9th weeks to be of the normocytic hypochromic type and the microcytic normochromic type in G2 and G3 goats, respectively.

Leukogram

Results of the leukogram of different experimental groups are shown in Table 6. Leukogram parameters of the control negative (G4) goats were within the normal range throughout the experimental period.

Table 6.

Leukogram of goats experimentally infected with H. contortus affected by different treatments during the experimental period

| Parameters | Groups | Weeks post infection (PI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3rd | 5th | 7th | 9th | ||

| WBC (× 103/μl) | G1 | 10.57 ± 0.69a | 12.37 ± 0.63Ab | 14.77 ± 0.19Cc | 13.87 ± 0.19Cbc | 12.89 ± 0.52Cb |

| G2 | 10.41 ± 0.11a | 12.18 ± 0.55Ab | 12.46 ± 0.59Ab | 11.27 ± 0.48Aab | 11.34 ± 0.25Aab | |

| G3 | 11.00 ± 0.12a | 11.90 ± 0.31Ab | 13.71 ± 0.41ACc | 11.87 ± 0.55Aab | 12.20 ± 0.27Ab | |

| G4 | 10.70 ± 0.50 | 10.73 ± 0.25B | 11.00 ± 0.32B | 10.93 ± 0.43A | 10.84 ± 0.66A | |

| Lymphocytes % | G1 | 60.33 ± 1.39c | 66.11 ± 0.49Bb | 66..00 ± 0.71Ab | 65.57 ± 1.00Ab | 65.33 ± 1.31Ab |

| G2 | 57.57 ± 1.00c | 66.53 ± 1.62Bb | 65.00 ± 1.23Ab | 61.97 ± 2.60ABc | 62.67 ± 2.44Ac | |

| G3 | 56.47 ± 2.56c | 65.36 ± 0.55Bb | 65.20 ± 1.37Aab | 61.25 ± 2.43ABa | 61.48 ± 2.26Aac | |

| G4 | 55.17 ± 0.69a | 57.30 ± 0.78Cab | 58.37 ± 0.68Bb | 59.33 ± 0.71Bb | 57.04 ± 0.34Bab | |

| Monocytes % | G1 | 3.66 ± 0.28a | 5.33 ± 0.55Ab | 4.90 ± 0.14Bb | 5.36 ± 0.95Bb | 5.28 ± 0.21Ab |

| G2 | 3.33 ± 0.64a | 5.06 ± 0.23Ab | 5.45 ± 0.66Bb | 4.50 ± 0.43ABb | 4.48 ± 0.25ABb | |

| G3 | 4.13 ± 0.46a | 4.76 ± 0.83ABab | 5.97 ± 0.70Bb | 5.10 ± 0.15Bab | 5.05 ± 0.45Aab | |

| G4 | 4.10 ± 0.30 | 3.96 ± 0.37B | 3.80 ± 0.12A | 4.10 ± 0.21A | 4.07 ± 0.16B | |

| Neutrophils % | G1 | 32.03 ± 1.02a | 20.23 ± 0.57Bb | 20.00 ± 0.92Bb | 22.45 ± 1.48Bb | 23.40 ± 1.95Ab |

| G2 | 34.50 ± 1.32a | 21.08 ± 0.38Bb | 20.11 ± 0.54Bb | 25.67 ± 1.60Bc | 26.42 ± 1.10Ac | |

| G3 | 33.43 ± 0.86a | 21.55 ± 0.34Bb | 20.50 ± 0.66Bb | 25.32 ± 1.70Bc | 25.55 ± 1.63Ac | |

| G4 | 36.10 ± 0.61a | 34.40 ± 0.30A | 33.50 ± 0.76A | 31.90 ± 0.73Ab | 34.49 ± 0.90B | |

| Eosinophils % | G1 | 3.66 ± 0.33a | 8.33 ± 0.88Bb | 9.00 ± 0.33Bb | 9.33 ± 0.33Cb | 7.75 ± 0.80Bb |

| G2 | 3.33 ± 0.33d | 7.00 ± 0.57Bb | 9.11 ± 0.33Bc | 7.53 ± 0.17Ab | 6.10 ± 1.96Bb | |

| G3 | 4.00 ± 0.57a | 8.33 ± 0.33Bb | 8.33 ± 0.33Bb | 6.00 ± 0.11Dc | 7.67 ± 1.33Bb | |

| G4 | 3.66 ± 0.33 | 4.00 ± 0.57A | 4.33 ± 0.33A | 4.00 ± 0.57B | 4.00 ± 0.21A | |

| Basophils % | G1 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 00.00 ± 0.00 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.33 |

| G2 | 0.66 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.15 | |

| G3 | 0.66 ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.66 ± 0.13 | |

| G4 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.66 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.14 | |

Mean ± SE

Values with different superscripts A, B, C, D in the same column (among groups) and a, b, c, d in the same row (within groups) are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05

G1: Goats infected—untreated and expressed as control positive

G2: Goats infected and treated with BAF-EE

G3: Goats infected and treated with albendazole

G4: Goats uninfected and dosed with BAF-E E and expressed as control negative

Results revealed significant (P ≤ 0.05) increases in WBCs counts in all infected groups as compared to 0 time values of the experiment and to the uninfected control G4. Counts of G1 goats were elevated throughout the experiment, while those of G2 and G3 goats were increased during the 3rd and 5th weeks PI. The increase of total leukocytes was attributable to significant (P ≤ 0.05) increases in lymphocytes, monocytes and eosinophils count percentages on expense of neutrophils. The previously mentioned cells were elevated in G1 goats throughout the experiment. In goats of G2 and G3, lymphocytes were elevated significantly (P ≤ 0.05) at the 3rd and 5th weeks PI then were lowered after treatment at the 7th and 9th weeks in G2 and at the 9th week in G3 to reach near 0- time values. Among groups, no significant variances in lymphocytes were observed PT in goats of G2 and G3 on 7th week compared to goats in G1 and G4, while on 9th week PI there were significant (P ≤ 0.05) variances between all infected groups and uninfected G4 goats. Eosinophils recorded marked (P ≤ 0.05) elevated values throughout the experiment either within/or among groups except on 7th week PI, there were significant (P ≤ 0.05) depression in goats of G2 and G3compared to those in G1 and G4 with significant (P ≤ 0.05) variance among values of G2 and G3. Monocytes were elevated significantly (P ≤ 0.05) throughout the experiment in G2 goats and at the 5th week PI in those of G3 which depressed significantly (P ≤ 0.05) after treatment to reach near to 0 time values. The mean percentages of neutrophils in all infected groups showed significant (P ≤ 0.05) decrease at the 3rd week PI till the end of the experiment compared with 0-time values and the uninfected control G4. Results of basophils revealed no significant differences among experimental groups.

Discussion

Haemonchosis, an important disease caused by a highly pathogenic nematode parasite of small ruminants (sheep and goats) called H. contortus which induces an acute disease and high mortality among these animals (Elshahawy et al. 2014; Brik et al. 2019). Due to increased occurrence of multiple drug resistant parasites, other more sustainable methods of treatment are being investigated including the use of medicinal plants with anthelmintic properties such as B. aegyptiaca.

The present study was carried out to evaluate the anthelmintic effects of B. aegyptiaca fruits’ mesocarp ethanolic extract (BAF-EE) against H. contortus in goats compared with the common commercial drug, albendazole.

In the present study, the crude BAF-EE was analyzed and its components were identified by comparing their mass spectra and retention time with those of the NIST and WILEY library. The constituents of BAF-EE shown by the analyzer included 28 compounds and the chemical structure of each compound was identified. Of these compounds, 17 were found more than 1%, while the percentage of α-Methylcaproic acid was shown more than 47%. Our findings are parallel with the findings of Saboo et al. (2014) and could be a useful referral for further isolation, purification and evaluation of B. aegyptiaca fruits therapeutic efficacy and safety for human and animals.

Phytochemical screening of BAF-EE revealed the presence of saponins, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolic compounds and alkaloids which agree with previous reports of Chothani and Vaghasiya (2011) and KoKo et al. (2017).

It was evident from this study that crude BAF-EE exhibited a strong in vitro antioxidant activity. Similar reports on the potent antioxidant effect of B. aegyptiaca fruits appear in previous studies as well (Meda et al. 2010; Chothani and Vaghasiya 2011; Koko et al. 2017). It has been reported that the phenols, flavonoids and terpenoids of the plant possess an antioxidant activity (Maryam et al. 2009; Khatua et al. 2013). Also, it was documented that the major classes of anti-parasitic phytochemical compounds from plants are alkaloids and saponins (Al-Shaibani et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2010). Our results from the phytochemical analysis confirmed the presence of antioxidants and anti-parasitic compounds in the fruits of B. aegyptiaca which support traditional application B. aegyptiaca fruit against internal parasites.

Results of the present study did not show any abnormal behavioral changes and evidence of toxicity during or after treatment with BAF-EE, which are agreed with the reports stated by Githiori et al. (2004), Albadawi (2010) and Hassan (2014).

Moreover, H. contortus infection affected the homeostasis of goats which was clinically manifested mainly by signs of anemia. The severity of the disease was depended on the number of the infective larvae given to the animals, which was in accordance with the findings of Rahman and Collins (1990). According to Soulsby (1982), the development of haemonchosis is a direct reflection of infective dose. In this study, goats were infected with 10,000 L3, which caused an acute form of haemonchosis. Our results correspond to data from studies of Ameen et al. (2010) in goats and Bowman (2014) and Iliev et al. (2017) in lambs who described that the most often clinical signs of acute haemonchosis are weakness, lethargy, lack of appetite, thirst, rapid and shallow breathing, pale mucous membranes and diarrhea. It was noticed in the experimental goats that the prepatent period of H. contortus was 21 days in all infected groups and the severity of clinical signs coincided with the peak of egg shedding at the 4th and 5th weeks PI.

The total worm burden at necropsy indicated that Baladi breed of goats employed in this study were susceptible to experimental infection with H. contortus. It is evident that BAF-EE exhibited significant anthelmintic activity against adult H. contorts worms compared with the untreated control group. Similarly, the anthelmintic effect of B. aegyptiaca has been reported against H. contortus in sheep (Albadawi 2010; Hassan 2014). Treatment of H. contortus with BAF-EE at a dose of 9 g/kg BW showed anthelmintic efficacy of 75.08% at the 1st week PT and maximum reduction of 88.10% in EPG at the 4th week PT. Similar results have been found by Albadawi (2010) and Hassan (2014), who recorded that the efficacy percentage of B. aegyptiaca against H. contortus parasites and EPG in sheep were 69.6 and 97%, respectively. Also, the efficacy of B. aegyptiaca fruits was found to be 92.3% against F. hepatica (Koko et al. 2000) and Schistosoma mansoni (Koko et al. 2005) as well.

The anthelmintic activity of B. aegyptiaca could be attributed to its bioactive compounds working jointly or separately for altering membrane permeability of the parasite (Chothani and Vaghasiya 2011) or binding the glycoprotein of the cuticle of the parasite (Kumar et al. 2011; Thompson and Geary 1995), causing their death. Saponins are known to cause damages in the membrane of the parasite and causing vacuolization and disintegration of their tegument (Wang et al. 2010). Moreover, it has been reported that alkaloids have the ability to intercalate with protein synthesis of the parasite (Al-Shaibani et al. 2009).

In the present study, use of 5 mg/kg BW of albendazole for the treatment of Haemonchosis showed an anthelmintic efficacy of 98.29% after 4 weeks of treatment, while BAF-EE at the rate of 9 g/kg BW revealed 88.10% efficacy. Albendazole acted well against mature stages of the parasite and the drug was responsible for delaying of some worms to reach maturity. The present results can be explained by the use of a crude extract of the plant containing small concentrations of its active ingredients versus the use of the synthetic anthelmintic drug containing the chemical compounds in pure forms (Rates 2001).

Improvement of the condition of the uninfected BAF-EE treated goats of G4 was noticed, which could be attributed to the wide range of biological constituents of B. aegyptiaca fruits’ mesocarp such as phytoconstituents, crude proteins (3.2–6.6%), carbohydrates (64–72%), organic acids (15%) and vitamin C (0.01–0.3%) (Chothani and Vaghasiya 2011).

In this study, goats of infected untreated G1 showed marked decreases in PCV and Hb values and microcytic hypochromic anemia from the 3rd week PI to the end of the experiment. These decreases might be attributed to blood loss that resulted from the sucking activity of both larval and adult stages of the parasite and from hemorrhages associated with the damaged epithelium of the abomasa (Urquhart et al. 1996). Gauly and Erhardt (2002), Amarante et al. (2004) stated that, the PCV is an essential parameter which may be used besides fecal egg count to describe resistance against nematode parasites in sheep. Albadawi (2010), Hassan et al. (2013), Rouatbi et al. (2016), and Mannan et al. (2017) reported rather similar results to ours after experimental infection with H. contortus in small ruminants.

Goats treated with B. aegyptiaca and albendazole revealed reduction in PCV and Hb values and microcytic hypochromic anemia at the 3rd and 5th weeks PI, values then regained 0 time levels after 2–4 weeks of treatment in G2 goats and were still low (PCV) or slightly lower than 0 time (Hb) in G3 goats. Anemia recorded after 2 and 4 weeks of treatment was of the normocytic hypochromic type in G2 and the microcytic normochromic type in G3. Changes of the erythrocytic parameters observed after treatment could indicate improvement of the condition of animals after reduction of the worm burden. Similar results were obtained by Koko et al. (2000), Adam (2006), Albadawi (2010), and Hassan (2014). However, our results disagree with Costa et al. (2006), Eguale et al. (2007), Bizimenyera et al. (2008) who showed that treatment with medicinal plants did not help animals to improve or maintain their hematological parameters. Furthermore, Hassan et al. (2013) reported that albendazole at a single dose of 5 mg/kg BW failed to improve the effect of H. contortus infection on the erythrogram. This controversy might be due to different parasitic infection levels and environmental conditions.

In the present experiment, the significant increase in leukocyte counts of infected goats was a reflection of significant increase in lymphocytes, monocytes and eosinophils at the expense of neutrophils which showed reduced counts than the normal levels. Similar results were reported after experimental H. contortus infection by El Hassan (2002), Albadawi (2010) and Hassan et al. (2013). The increased number of lymphocytes could be related to an antigenic stimulation of the abomasal mucosa due to excretory-secretary products of H. contortus. The eosinophilia and lymphocytosis observed are in agreement with the findings of Albadawi (2010) and Hassan et al. (2013). The increase in the number of eosinophils is considered an important element in the response against H. contortus infection as reported by Balic et al. (2000). Eosinophils mobilized against specific parasites were frequently found to cause immobility and death of larvae of homologous or heterologous parasites often in association with antibodies and/or other factors (Rainbird et al. 1998; Terefe et al. 2005).

The mean values of total leukocytes’ count in both infected—treated groups (G2 and G3) tended to decrease on the 7th and 9th weeks PI. These results are supported by Koko et al. (2000), Albadawi (2010) and Hassan et al. (2013) who recorded reduction in WBCs and eosinophils’ counts at the last 2 weeks after treatment with B. aegyptiaca and albendazole.

Conclusion

Results of this study indicated that B. aegyptiaca showed a significant anthelmintic activity against H. contortus at dose of 9 g/Kg BW as determined by reduction in worm burden and fecal egg counts of H. contortus, and can improve hemogram and health condition of infected goats. The present findings suggest that B. aegyptiaca could form an alternative to commercially available synthetic anthelmintics. However, further investigations are required at different doses and against different parasitic stages and species to determine the true potentials of this plant as anthelmintic for control of gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a part of a Ph.D. Thesis to be submitted to The Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University. The paper was carried out by joint financial support of The National Research Center (as a part of a project No. 11020303 supervised by Prof. Dr. Hala A. Abou-Zeina within the 11th research plan of NRC) and the Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University.

Authors’ contributions

AHM and HAAA designed, supervised and provided the steer for the experiment. HAAA and AHM conducted the phytochemical analysis of plant extract. EJ and NMFH carried out the experimental infection for providing Haemonchosis. EJ, SMN, NMF, HAAA and KMAM conducted the in vivo experiments and the laboratory work of the samples. EJ, SMN and KMAM performed the hematological studies. AHM, HAAA, SMN, EJ and NMFH analyzed and discussed the resultant data. AHM, HAAA, SMN, EJ and NMFH implemented writing the manuscript. AHM and HAAA revised and reviewed the manuscript for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Ethical Committee for Medical Research (MREC) at the National Research Centre (NRC), Egypt and in accordance with local laws and regulations. Approval Protocol No.: 16229.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ezatullah Jaheed, Email: jaheedezatullah@yahoo.com.

Amira H. Mohamed, Email: damira115@yahoo.com

Noha M. F. Hassan, Email: nohamhassan555@yahoo.com

Khaled M. A. Mahran, Email: k.mahran@cu.edu.eg

Soad M. Nasr, Email: soadnasr@yahoo.com

Hala A. A. Abou-Zeina, Phone: +01001422671, Email: hala_zeina60@yahoo.com

References

- Adam NAM (2006) Effect of piper Abyssinica and Jatropha curcas against experimental Haemochus contortus infection in desert goats. MVSc Thesis University of Khartoum Sudan

- Albadawi ROE (2010) In vivo and in vitro anthelmintic activity of Balanites aegyptiaca and Artemisia herba Alba on Haemonchus contortus of sheep. Ph.D. Thesis Faculty of Veterinary Science University of Khartoum

- Al-jebory EZ, Al-Khayat DA. Effect of Haemonchus contortus infection on physiological and immunological characters in local Awassi Sheep and Black Iraqi goats. J Adv Biomed Pathobiol Res. 2012;2(2):71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shaibani IRM, Phulan MS, Shiekh M. Anthelmintic activity of Fumaria parviflora (Fumariaceae) against gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep. Int J Agric Biol. 2009;11:431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Amarante AFT, Bricarello PA, Rocha RA, Gennari SM. Resistance of Santa Ines, Suffolk and Ile de France sheep to naturally acquired gastrointestinal nematode infections. Vet Parasitol. 2004;120:91–106. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameen SA, Joshua RA, Adedeji OS, Ojedapo LO, Arnao SR. Experimental studies on gastrointestinal nematode infection; the effects of age on clinical observations and haematological changes following Haemonchus contortus infection in West African Dwarf goats. World J Agric Sci. 2010;6:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Awad AH, Ali AM, Hadree DH. Some haematological and biochemical parameters assessments in sheep infection by Haemonchus contortus. Tikrit J Pure Sci. 2016;21(1):11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Baerman G, Wetzal R (1953) Cited after Soulsby EJL (1965) Text book of veterinary clinical parasitology, vol I Helminths 1st ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford

- Balic A, Bowles VM, Meeusen EN (2000) The immunology of gastrointestinal nematode infections in ruminants. Adv Parasitol 45: 181–241. In: Benjamin MM (ed) (2005) Outline of Vet Cl Pathol 3rd edn. Kalyani publishers, New Delhi, 42 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bizimenyera ES, Meyer S, Naidoo V, Eloff JN, Swan GE. Efficacy of Peltophorum africanum Sond (Fabaceae) Extracts on Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in sheep. J Anim Vet Adv. 2008;7(4):364–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman D. Georgis parasitology for veterinarians, chapter 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2014. pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Brik Kamal, Hassouni Taoufik, Elkharrim Khadija, Belghyti Driss. A survey of Haemonchus contortus parasite of sheep from Gharb plain, Morocco. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. 2019;4:e00094. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2019.e00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapagain BP, Wiesman Z. Metabolite profiling of saponins in Balanites aegyptiaca plant tissues using LC (RI)–ESI/MS and MALDI-TOF/MS. Metabolomics. 2008;4(4):357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Chothani DL, Vaghasiya HU. A review on Balanites aegyptiaca Del (desert date): phytochemical constituents, traditional uses and pharmacological activity. Pharmacognosy Rev. 2011;5(9):55–62. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa CTC, Bevilaqua CML, Maciel MV, et al. Anthelmintic activity of Azadirachta indica A Juss against sheep gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet Parasitol. 2006;137:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughari JH, Pukuma MS, De N. Antibacterial effects of typhi. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6(19):2212–2215. [Google Scholar]

- Eguale T, Tilahun G, Debella A, et al. In vitro and in vivo anthelmintic activity of crude extracts of Coriandrum sativum against Haemonchus contortus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hassan RO (2002) Experimental infection of three Sudanese sheep breeds to Haemonchus contortus. M.Sc Thesis University of Khartoum Sudan

- El-Halawany NK, Abd-El-Razek FM, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in exon-3 region of growth hormone gene in the Egyptian goat breeds. Egypt Acad J Biolog Sci. 2017;9(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Elshahawy IS, Metwally AM, Ibrahim DA. An abattoir-based study on helminthes of slaughtered goats (Capra hircus L., 1758) in upper Egypt. Helminthologia. 2014;51(1):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Githiori JB, Glund JHO, Waller PJ, Baker RL. Evaluation of anthelmintic properties of some plants used as livestock dewormers against Haemonchus contortus infections in sheep. Parasitology. 2004;129:245–253. doi: 10.1017/s0031182004005566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauly M, Erhardt G. Changes in faecal trichostrongyle egg count and haematocrit in naturally infected Rhön sheep over two grazing periods and associations with biochemical polymorphisms. Small Rumin Res. 2002;44:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan N (2014) Evaluation of efficacy of some medicinal plant extracts on treatment of sheep haemonchosis. Ph.D. Thesis Faculty of Veterinary Medicine El Sadat University

- Hassan MFM, Gammaz HA, Abdel-Daim MM, et al. Efficacy and safety of albendazole against Haemonchus Contortus infestation in goats. Res Zool. 2013;3(3):31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hördegen P, Hertzberg H, Heilmann J, et al. The anthelmintic efficacy of five plant products against gastrointestinal Trichostrongylids in artificially infected lambs. Vet Parasitol. 2003;117:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader MMR, Capitan SS, Eduardo SL, Roxas NP. Effects of experimental Haemonchus contortus infection on red blood cells and white blood cells of growing goats. AJAS. 1997;10(6):679–682. [Google Scholar]

- Iliev PT, Prelezov P, Ivanov A, et al. Clinical study of acute haemonchosis in lambs Trakia. J Sci. 2017;15(1):74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Khatua S, Roy T, Acharya K. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging capacity of phenolic extract from Russula lauroceras. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2013;6(4):156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Koko WS, Galal M, Khalid HS. Fasciolicidal efficacy of Albizia anthelmintica and Balanites aegyptiaca compared with albendazole. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71:247–252. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koko WS, Abdallab HS, Galala M, Khalida HS. Evaluation of oral therapy on Mansonial Schistosomiasis using single dose of Balanites aegyptiaca fruits and praziquantel. Fitoterapia. 2005;76:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koko SE, Talib MA, Elfatih F, et al. Antioxidant activity and phytochemical screening of Balanites aegyptiaca fruits. World J Pharm Med Res. 2017;3(10):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Chaudhary S, Jha K. Anthelmintic activity on the Leptadenia pyrotechnica (Forsk.) Decne. J Nat Prod Plant Resour. 2011;1(4):56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan MA, Masuduzzaman M, Rakib TM, et al. Histopathological and haematological changes in haemonchosis caused by Haemonchus contortus in small ruminants of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Vet Anim Sci. 2017;5(2):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Maryam Z, Farrukh A, Iqbal A. The in vitro antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of four Indian medicinal plants. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2009;1(Suppl 1):88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Meda NT, Lamien-Meda A, Kiendrebeogo M, Lamien CE, et al. In vitro antioxidant, xanthine oxidase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. (Balanitaceae) Pak J Biol Sci. 2010;13:362–368. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2010.362.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obasi NL, Egbuonu ACC, Ukoha PO, Ejikeme PM. Comparative phytochemical and antimicrobial screening of some solvent extracts of Samanea saman pods. Afr J Pure Appl Chem. 2010;4:206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto P, Pineda M, Aguilar M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphor molybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal Biochem. 1999;269:337–341. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman WA, Collins GH. Change in live weight gain, blood constituents and worm egg output in goats artificially infected with a sheep-derived strain of Haemonchus contortus. Br Vet J. 1990;146(6):543–550. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(90)90058-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbird MA, McMillan D, Meeusen ENT. Eosinophil-mediated killing of Haemonchus contortus larvae: effect of eosinophil activation and role of antibody, complement and interleukin-5. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20(2):93–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rates SMK. Plants as source of drugs. Toxicon. 2001;39:603–613. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts FHS, O’Sullivan PJ. Methods for egg counts and larval cultures for strongyles infesting the gastro-intestinal tract of cattle. Aust J Agric Res. 1950;1(1):99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rouatbi M, Gharbi M, Rjeibi MR, et al. Effect of the infection with the nematode Haemonchus contortus (Strongylida: Trichostrongylidae) on the haematological, biochemical, clinical and reproductive traits in rams. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2016;83(1):1–8. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v83i1.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboo SS, Chavan RW, Tapadiya GG, Khadabadi SS. Review article: an important ethnomedicinal plant balanite aegyptiaca del. Int J Phytopharm. 2014;4(3):75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby H. Anthelmintics resistance; how to overcome it? Iran J Parasitol. 2013;8:18–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby MA, Moghazy FM, Shalaby HA, Nasr SM. Effect of methanolic extract of Balanites aegyptiaca fruits on enteral and parenteral stages of Trichinella spiralis in rats. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecore GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 6. Ames: Lowa State University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby EJL. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7. London: Baille Tindall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq KA, Chishti MZ, Ahmada F, Shawl AS. Anthelmintic activity of extracts of Artemisia absinthium against ovine nematodes. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terefe G, Yacob HT, Grisez C, et al. Haemonchus contortus egg excretion and female length reduction in sheep previously infected with Oestrusovis (Diptera:Oestridae) larvae. Vet Parasitol. 2005;128:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food; Agriculture Development and Advisory Service . Manual of Veterinary Parasitological Laboratory Techniques. Technical Bulletin No. 18. 2. London: Her Majesty’s stationery office; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Thienpont D, Rochette F, Vanparijs OFJ. Diagnosing helminthiasis through coprological examination. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29(5):1021. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DP, Geary TG. The structure and function of helminth surfaces. In: Marr JJ, editor. Biochemistry and molecular biology of parasites. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 203–232. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari P, Kumar B, Mandeep K, et al. Phytochemical screening and extraction: a review. Int Pharm Sci. 2011;1(1):98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart GM, Armour J, Duncan JL, et al. Veterinary parasitology. 2. London: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vijigiri D, Sharma PP. Traditional uses of plants in indigenous folklore of Nizamabad District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Ethnobot Leafl. 2010;14:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Waller PJ. Nematode parasite control of livestock in the tropics/subtropics: the need for novel approaches. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Weller CL. Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2006;17(6):300–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wang GX, Han J, Zhao LW, et al. Anthelmintic activity of steroidal saponins from Paris polyphylla. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:1102–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DJ, Wardrop KJ. Schalm’s veterinary hematology. 6. Ames Iowa: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wood IB, Amaral NK, Bairden K, et al. World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.) second edition of guidelines for evaluating the efficacy of anthelmintics in ruminants (bovine, ovine, caprine) Vet Parasitol. 1995;58:181–213. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00806-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]