Abstract

Trauma in the form of instrumentation, slap, blast, accident, and sporting injury can result in tympanic membrane (TM) perforations which spontaneously recover in 53–94%. The closure rates of TM perforation due to above causes do not vary greatly; however, some otolaryngologists prefer to perform immediate microsurgical procedures to accelerate the recovery process. Our aim is to study the efficacy of Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) Chemical Cauterization (50%) and Platelet rich fibrin (PRF) Plug Myringoplasty technique in healing traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. To evaluate the preoperative and postoperative hearing outcome from the procedure and compare them. Study design is prospective study. A pilot study was carried out amongst selected 25 patients with central perforations in the Department of ENT, for duration of 2 years from July 13 to July 15. All 25 patients underwent PTA assessment & TCA (50%) and Autologous PRF Plug Myringoplasty technique done and follow up to 6 months postoperatively. The success rate traumatic tympanic membrane closure was found to be 92%. Pre- and post-operative hearing assessments of each patient were done & showed statistically significant air–bone gap closure with success rate of 88% (p < 0.05). From this study, the closure rate in traumatic tympanic membrane perforation by TCA (50%) and PRF Plug Myringoplasty technique was 92% with statistically significant hearing improvement (88%). This technique can be recommended as a time and cost effective office based procedure for treatment of traumatic tympanic membrane perforations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12070-017-1239-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Autologous, Platelet rich fibrin, Myringoplasty

Introduction

Trauma in the form of instrumentation, slap, blast, accident, and sporting injury can result in tympanic membrane (TM) perforations which spontaneously recover in 53–94% [1–4]. The closure rates of TM perforation due to above causes do not vary greatly, however some otolaryngologists prefer to perform immediate microsurgical procedures to accelerate the recovery process [5, 6].

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) was first described by Choukroun et al. [7] in 2001. Dohan et al. [8, 9] conducted a detailed biochemical analysis in 2006. Dohan et al. [9] reported that PRF consists of an intimate assembly of cytokines, glycanic chains and structural glycoproteins enmeshed within a slowly polymerized fibrin network. These natural biomediators are cheaper, less invasive and readily obtained which may correct cellular events in wound healing, such as cell proliferation, differentiation and chemotaxis. PRF membrane has a strong, elastic fibrin structure containing growth factors; it may be an ideal patching material in the treatment of traumatic TM injuries.

The objective of this study was to evaluate efficacy of Trichloroacetic acid (50%) and PRF Plug Myringoplasty technique for management of traumatic tympanic membrane perforation with regards to recovery rates, healing time and correction of the mean air–bone gap.

Materials and Methods

A pilot study was carried amongst 25 selected patients with traumatic tympanic membrane (central) perforations in the Department of ENT, for duration of 2 years from July 13 to July 15. All patients underwent Pure tone Audiometry (PTA) assessment & TCA (50%) and Autologous PRF Plug Myringoplasty technique was done under Local Anaesthesia and followed up to 6 months postoperatively. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approval was granted by the local ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study Area: Hospital Based (Tertiary referral Hospital).

Design of Study: A Prospective Study.

Inclusion Criteria

Traumatic Tympanic membrane perforation < 4 mm which failed to heal spontaneously.

Inactive Middle ear cleft.

Functional Eustachian tube.

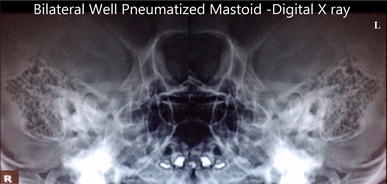

Well Pneumatized Mastoid air cell system.

Pure Tone Audiogram with Conductive hearing loss and intact ossicular chain.

No disease that could progress to a clotting disorder and no use of anticoagulants within the previous 10 days.

Exclusion Criteria

Tympanic membrane perforation > 4 mm.

History of Previous otological surgery.

Active Middle ear cleft Disease.

Dysfunctional Eustachian tube & poorly pneumatized Mastoid air cell system.

Pure Tone Audiogram with Sensorineural hearing loss and ossicular chain disruption.

Symptomatic Deviated Nasal Septum and Sinusitis (acute or chronic)

HBV and HIV Positive status.

Procedure

Patients with traumatic tympanic membrane perforations were included in the study according to the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). A thorough clinical, medical history with routine otorhinolaryngological examination was done which includes an in office based diagnostic nasal endoscopy to rule out symptomatic deviated nasal septum and sinusitis (acute or chronic), eustachian tube orifice for any mechanical and functional obstruction, nasopharynx, eustachian tube patency was assessed by valsalva’s maneuver, oto-endoscopy were done for all the cases.

Fig. 1.

Left ear traumatic tympanic membrane perforation

Size of the perforation is measured by oto-endoscopy by positioning the patient in supine posture with the involved ear facing upwards. If there is any associated wax or secondary fungal infection of the external auditory canal, it is cleared. Measurement was performed using a custom-designed measuring pick formed by attaching a 4 mm part onto the extremity of a straight pick with a 90 angle. Taking into account that the diameter of tympanic membrane is 8–9 mm, the patients with perforations 4 mm (small perforations) were selected and then PRF 1.5-times larger than the perforation site was applied.

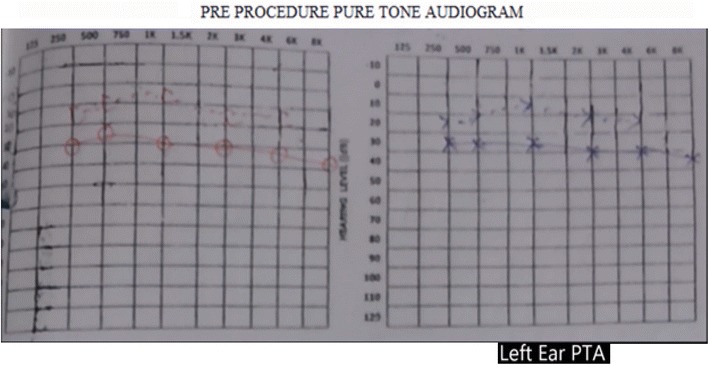

All 25 patients were explained about the procedure in detail, written and informed consent obtained for documentation, visual recording of the office procedure. The procedure doesn’t involve hospitalization and General Anaesthesia. Laboratory & radiological investigations was carried out on outpatient basis (complete hemogram test, retroviral and HbsAg status, X ray of Bilateral Mastoid, pure tone audiometry, patch test) (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

Fig. 2.

Bilateral well pneumatized mastoid digital X-ray

Fig. 3.

Diagnostic nasal endoscopy to rule out deviated nasal septum and sinusitis

Fig. 4.

Pre procedure pure tone audiogram

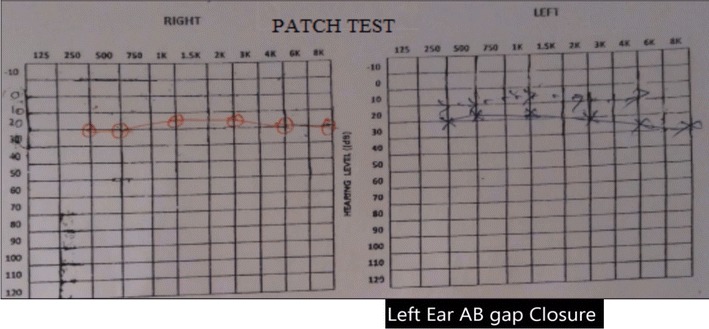

Patch Test

A small piece of paper patch was trimmed to approximately 1.5-times larger than the perforation site and laid over the perforation using ear forceps under oto-endoscopic guidance (Fig. 5). Pure tone Audiometry is done post patch test to compare with the first Audiogram report, which could help in clinical assessment of hearing improvement by measurement of the mean air–bone gap before and after the procedure (Fig. 6). Assessment of ossicular chain continuity could be indirectly assessed from the pure tone audiogram average and closure of air–bone gap post patch test. Paper patch is then removed after the patch test.

Fig. 5.

Patch test

Fig. 6.

Pure tone audiogram after patch test

PRF Preparation

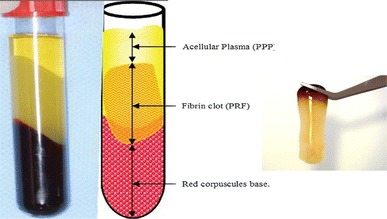

A 10-cc venous blood sample was taken by catheter from the patients into dry, glass vacuum tubes. The tubes were immediately centrifuged (2400 rpm, 12 min). After completing the process, three layers were observed to have formed. The base layer was red blood cells, the top layer was non-cellular plasma and the middle layer was PRF coagulate. With sterile forceps, the PRF was removed from the tube and stripped from the adjacent red blood cell layer. With absorption of the PRF serum into a gauze pad, a membrane, rich in fibrin from the matrix and with high resistance, was obtained. The membrane was cut to size approximately 1.5-times larger than the perforation (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Image showing the various layers immediately following centrifuge. Platelet rich fibrin separated and held with a forcep

Patient Position

Patient positioned supine with the affected ear turned upwards.

Anaesthesia

Under Local Anaesthesia, 4% Xylocaine was used to anaesthetize the tympanic membrane by instilling few drops into a small cotton ball and placing it into the external canal wall over the surface of the tympanic membrane for about 10 min and later removed.

Technique (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8.

Autologous platelet rich fibrin matrix plug myringoplasty technique. a Left ear traumatic tympanic membrane perforation, b 4% xylocaine soaked cotton for local anaesthesia, c 50% trichloroacetic acid application to freshen the margins of the perforation, d and e drawing 10 cc blood to obtain Platelet rich fibrin tube placed in centrifuge, f centrifuge apparatus, set at 2400 rpm for 12 min, g and h Platelet rich fibrin obtained and separated from Red blood cell layer, i Platelet rich fibrin plugging myringoplasty done, j post-procedure oto-endoscopy day 15, k post-procedure oto-endoscopy day 60

Under Oto-endoscopic guidance, the rim of the perforation was cauterized using a cotton tipped applicator dipped in freshly prepared 50% trichloroacetic acid until a white cauterized margin 0.5 mm in width, care was taken not to scar the promontory. Autologous PRF membrane was cut to size approximately 1.5-times larger than the perforation was plugged through the perforation site, no middle ear packing material used. External auditory canal was packed with gelfoam soaked with platelet poor plasma. Sealing the external auditory canal with cotton ball impregnated with antibiotic soaked ointment.

Post Procedure Management

All 25 patients received the following advice post procedure.

Broad spectrum antibiotics, antihistamines, analgesics, antioxidant therapy are advised for 1 week. Combination of Antibiotic with steroid ear drops (Neosporin H, Otek AC, Ciplox D) 3 drops was instilled twice daily for 3 weeks.

Avoid Ear canal instrumentation, forceful coughing, sneezing or blowing of nose, smoking & alcohol consumption.

Being an office procedure, patient can be followed up after 1st week, 4th week, 2nd month, 3rd to 6th month. Otoscopic examination, an oto-endoscopy was performed to evaluate the speed of healing & closure rates of tympanic membrane perforation and PTA (2nd month) to determine mean air–bone gap.

Follow-Up

All 25 patients were followed until present. Duration of follow up ranged from 3 months to 2 years. The mean duration of follow up was 1 year.

Statistical Methods

Data collected will be entered on excel spread sheet after coding and further processed using SPSS Version 17.0 (Statistical package for social sciences). The data analysis will be done by computing proportions, mean of standard deviation. Appropriate test of significance will be used based on type of data. A p value < 0.05 will be considered significant.

Results

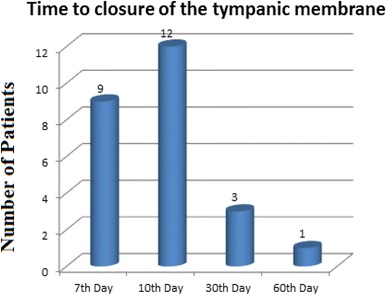

The patients included 15 males & 10 females with a mean age of 28.9 years. None of them had bilateral perforation. No statistically significant differences were observed in terms of perforation size, gender, or pre-operative audiological evaluations (p > 0.05) (Table 1). Closure was obtained in 23 patients (92%). In the 2 cases where closure was not obtained, PRF was re-applied: one closed & one did not. Mean closure time of TM perforation was 8 days (Fig. 9). Full closure of the TM was observed in 23 (92%) on post-operative day 10 (p < 0.05) after exclusion of two cases where tympanic membrane closure was not obtained. Suggesting a significant improvement (p < 0.05) in closure of traumatic tympanic membrane perforation.

Table 1.

Etiological factors of traumatic tympanic membrane perforations and closure rates

| Factors | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Size of perforation < 4 mm | 25 | 100 |

| Male | 15 | 60 | |

| Female | 10 | 40 | |

| 2 | TM closure post procedure | ||

| Yes | 23 | 92 | |

| No | 2 | 8 | |

| 3 | Etiology | ||

| A | Slap injury | 15 | 60 |

| B | Barotrauma | 1 | 4 |

| C | Water sports | 1 | 4 |

| D | Traffic accident | 3 | 12 |

| E | Instrumental injury | 5 | 20 |

Fig. 9.

Time to closure of the tympanic membrane using autologous PRF

Audiological Evaluations

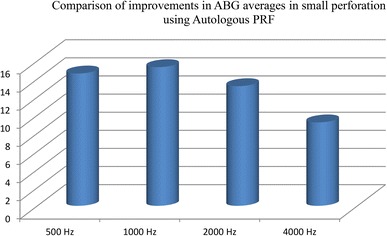

Initial and final air conduction (AC) and bone conduction (BC) average values of patients in a series of frequencies. Bone Conduction (BC) thresholds on 2000 and 4000 Hz are more affected than lower frequencies. On assessment, there was more improvement at lower frequencies compared to higher frequencies in ABG (air–bone gap) averages. There was more improvement at 500 Hz compared to 2000 and 4000 Hz, and at 1000 Hz compared to 4000 Hz after the treatment (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Improvements in ABG after the treatment in PRF membrane showed more improvement in 1000 and 2000 Hz (p < 0.05; Mann–Whitney U-test) (Table 3). The mean pre-operative air–bone gap was 20.2 db. On post-operative 2nd month, the mean improvement in the air–bone gap was 12.1 dB (p < 0.05). 22 patients of 25 showed significant hearing improvement (success rate 88% ABG closure).

Table 2.

Initial and final air and bone conduction thresholds following Platelet rich fibrin plug myringoplasty

| Valid n | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 Hz BC (Pre) | 25 | 3.10 | 2.64 |

| 500 Hz AC (Pre) | 25 | 21.00 | 6.12 |

| 500 Hz BC (Post) | 23 | 2.10 | 2.48 |

| 500 Hz AC (Post) | 23 | 4.10 | 3.53 |

| 1000 Hz BC (Pre) | 25 | 5.00 | 3.47 |

| 1000 Hz AC (Pre) | 25 | 23.32 | 4.76 |

| 1000 Hz BC (Post) | 23 | 4.32 | 2.10 |

| 1000 Hz AC (Post) | 23 | 7.23 | 3.11 |

| 2000 Hz BC (Pre) | 25 | 8.11 | 3.23 |

| 2000 Hz AC (Pre) | 25 | 22.67 | 4.23 |

| 2000 Hz BC (Post) | 23 | 6.34 | 2.18 |

| 2000 Hz AC (Post) | 23 | 9.10 | 3.28 |

| 4000 Hz BC (Pre) | 25 | 11.00 | 6.33 |

| 4000 Hz AC (Pre) | 25 | 24.13 | 6.33 |

| 4000 Hz BC (Post) | 23 | 9.00 | 4.23 |

| 4000 Hz AC (Post) | 23 | 11.46 | 4.32 |

Initial air and bone conduction thresholds are given for all the patients, final air and bone conduction thresholds are given for the patients whose perforation is closed. Pre: initial conduction threshold; post: final conduction threshold

Table 3.

The improvements in air–bone gap averages at different frequencies of all the patients whose perforations are closed

| Frequency (Hz) | n | Mean ABG (db) | SD | p | Difference | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The improvements in air–bone gap | ||||||

| 500 | 23 | 15.3 | 4.94 | < 0.001 | 500 > 2000 | 0.023 |

| 1000 | 23 | 14.6 | 3.78 | 500 > 4000 | < 0.001 | |

| 2000 | 23 | 12.2 | 3.99 | 1000 > 4000 | < 0.001 | |

| 4000 | 23 | 10.2 | 4.49 | |||

Discussion

Spontaneous recovery of traumatic TM perforations of any size heal without any interventions occurs in 53–94% cases, however few may present with persistent perforation and hearing loss [10, 11] it is preferable to wait for at least 3 weeks prior to any intervention.

Non-healing perforations typically require tympanoplasty for closure. Medical costs associated with tympanoplasty have recently compelled investigators to search for less expensive, simple non-surgical methods bringing down the waiting list for cases schedule for tympanoplasty for smaller tympanic membrane perforations. Morbidity associated with non-closure of perforation may result in chronic otorrhea and cholesteatoma formation, deterioration of hearing. The purposes of closing chronic dry perforations of the tympanic membrane are to improve hearing and prevent middle ear infections. Closure isolates the middle ear from external environment and prevents contamination by exposure to pathogens and restores the vibratory area of the membrane and affords round window protection. These problems limit the patient’s participation in water sports and for job recruitment in the military service and as a motor vehicle driver12. Closure of these perforations is gratifying to both the patient and the surgeon. The patient stands to gain as much as 15–25 dB of hearing. In some cases, tinnitus gets relieved.

While surgical closure of tympanic membrane perforation still remains the choice of management, effective closure of tympanic membrane perforation can be achieved by using chemical cautery and patch technique together for small and moderate sized perforations. The incidence of traumatic perforations of the tympanic membrane has been estimated at 8.6 per 1000 persons [13]. Three types of traumatic perforations can occur: penetrating, blunt, and iatrogenic. It is important to keep in mind that inner ear injury may accompany acute traumatic perforations, a possibility that should be evaluated by careful questioning.

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, several attempts at closing tympanic membrane perforations using prosthetic materials were made. The first published report to close the tympanic membrane perforation was in 1640 by Marcus Banzer who inserted a small ivory tube covered with pig’s bladder as a lateral graft [12]. Yearsley, in 1841, applied a ball of cotton wool moistened with glycerin against a TM perforation [14]. In 1853, Toynbee placed a rubber disk attached to a silver wire over the TM and reported significant hearing improvement [15]. The use of cauterizing agents to promote healing of tympanic membrane perforations was introduced by Roosa in 1876, who used the application of silver nitrate to the rim of a perforation [16]. The use of trichloroacetic acid was first advocated in 1895 by Okuneff [17]. Blake covered perforations with paper patches in 1887. It was not until Joynt combined the cautery and paper patch techniques that closure results improved [18], forming the basis of the modern-day use of the paper patch technique as popularized by Derlacki [19].

Studies have suggested that the healing process may be facilitated by patching with various materials, including paper, silk, and micropore strip tape [4–6, 20]. In addition to these, materials such as hyaluronate, heparin, EGF, FGF, PDGF, TGF and autogenous materials have been used in treatment [21, 22] of TM perforations.

PRF was first developed in France by Choukroun et al. [7] for use in oral and maxillofacial surgery. It is currently widely used by dental surgeons and during jaw surgeries. Erkilet et al. [10] reported that PRP had a positive effect on the healing of perforated TMs in rats and shortened the healing period.

Thrombocytes play an important role in hemostasis and wound healing. Growth factors, such as TGFb-1, EGF, PDGF, IGF-1, and VEGF, which are found in the alpha granules of thrombocytes, function in the healing stages. Depending on the method by which they are acquired and the contents, thrombocyte concentrates can be separated into two groups: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF). PRF is a second-generation thrombocyte product obtained by concentration of thrombocytes and cytokines within the fibrin network. It differs from PRP in that no synthetic material or anticoagulant is added; it can also be obtained readily in a short time and at low cost. Highly resistant, flexible, elastic autologous fibrin membranes can be obtained [8, 9]. Apart from growth factors, thrombocytes also have molecules that function in cell migration, such as fibrin, fibronectin, and vitronectin, which are known to be cell adhesion molecules. Fibrin is the active form of the plasma protein known as fibrinogen. This molecule, which is found in abundance both in plasma and in platelet alpha granules, plays a specific role in platelet aggregation during hemostasis. As the clumps of thrombocytes combine, they act as a sort of glue and, during coagulation; a protective wall is formed along the vascular branches. Fibrinogen forms the final sub-structure of all the coagulation reactions. The soluble molecule fibrinogen, while associated with polymerized fibrin gel by being changed to insoluble fibrin by thrombin, forms the first cicatricial matrix in the wound area. It also acts as an autogenous ‘antibiotic’, because of the high number of leukocytes contained in it, thereby reducing the risk of infection [8, 9].

Alvaro et al. [11] reported successful healing after the use of PRP in three patients with eardrum perforations that had not healed spontaneously. El-Anwar et al. [23] also reported successful results with the use of topical autologous PRP on the lateral surface of a cartilage graft and TM remnant during myringoplasty. In a comparison with spontaneous healing, Habesoglu et al. [24] reported that the use of PRF in acute traumatic TM perforations provided significantly better healing rates and times.

Research has revealed that the mean time of spontaneous healing of traumatic TM perforation is 25.9 days, but may be as long as 3 months [25]. In the current study of 25 patients, closure was obtained in 23 patients (92%). In the two cases where closure was not obtained, PRF was re-applied: one closed and one did not. The mean time to closure of the TM perforation was 8 days. Full closure of the TM was observed in 23 (92%) on post-operative day 10 (p < 0.05). Suggesting a significant improvement (p < 0.05) in closure of traumatic tympanic membrane perforation.

Non-explosive blast injury refers to otologic trauma, where a blow to the ear seals the external meatus, and causes a sudden increase of air pressure that strikes the tympanic membrane 26. Conductive hearing loss occurring in the speech frequencies was the most common form of hearing loss in this group of patients. The accompanying sensorineural hearing loss affects high frequencies. While air conduction thresholds are affected in low frequencies, bone conduction thresholds are affected more in the high frequencies. After the closure of the perforation, significant recovery of the conductive hearing loss is seen, but recovery of sensorineural hearing loss is less favorable [1, 3, 26].

In a study on 51 patients with traumatic TM perforation, Orji and Agu [1] have determined that average bone conduction value at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz is 8.1 dB and average bone conduction value at 4000 Hz is 13.2 dB. In our study, we have determined that, at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz, average bone conduction value is 5.5 dB and at 4000 Hz it is 11.33 dB. Additionally, BC thresholds on 2000 and 4000 Hz are more affected than lower frequencies. After treatment, there was no distinct increase in BC thresholds that would indicate any inner ear damage due to patching process. When average air–bone gap values of the patients have been assessed, it is determined that the values are higher at 500 and 1000 Hz, while at 2000 and 4000 Hz they become gradually lower (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Comparison of improvements in ABG averages in perforation using Autologous PRF

The mean pre-operative air–bone gap was 20.2 dB. On post-operative day 45, the mean improvement in the air–bone gap was 12.1 db; membrane quality in TM healing was better in patients treated with PRF. The consumables used in the PRF procedure are a glass dry vacuum tube and a catheter for taking blood. Our opinion is that PRF membrane is low cost and preferable due to its effects on accelerating the recovery process and hearing.

PRF is totally autologous & does not require a second procedure, making it more cost-effective. PRF also enables more rapid healing with better audiological improvement. The negative aspects of PRF are that blood must be taken from the patient, a centrifuge tubes are required and specialized knowledge is required for the preparation stages.

Conclusions

Autologous PRF, a product derived from whole blood through the process of gradient density centrifugation which is safe and effective in promoting the natural processes of wound healing. Its Potential value lies in its ability to incorporate high concentrations of platelet-derived growth factors, as well as fibrin, into the graft mixture which provides rapid and effective healing of traumatic TM perforation.

From this study, the closure rate in small central perforations by TCA (50%) and PRF Plug Myringoplasty technique without general anaesthesia was 92% & success rate 88% air–bone gap closure. This procedure does not require general anesthesia or hospitalization. PRF provides rapid healing of TM perforation and successful audiological results with no requirement for a second procedure. PRF is a promising biotechnology that is fuelling growing interest in tissue engineering and cellular therapeutics. This technique would be used as a time and cost effective office based procedure for the treatment of small central TM perforations in selected cases.

Summary

To Evaluate Success rate of healing traumatic tympanic membrane perforation with autologous platelet rich fibrin matrix under local anesthesia as an outpatient clinic procedure.

In this study, 25 patients with persistent traumatic tympanic membrane perforation as per inclusion criteria were included.

The closure rate in small central perforations by TCA (50%) and PRF Plug Myringoplasty technique was 92%. The mean time to closure was 8 days. Full closure of the TM was observed in 23 (92%) on post-operative day 10 (p < 0.05).

The mean pre-operative air–bone gap was 20.2 db. On post-operative day 45, the mean improvement in the air–bone gap was 12.1 db. 22 patients of 25 showed significant hearing improvement (success rate 88% ABG closure).

Autologous PRF plug myringoplasty technique can be recommended as a natural biomediator, time and cost effective office based procedure for treatment of traumatic tympanic membrane perforation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Orji FT, Agu CC. Determinants of spontaneous healing in traumatic perforations of the tympanic membrane. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33:420–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lou ZC, Lou ZH, Zhang QP. Traumatic tympanic membrane: a study of etiology and factors affecting outcome. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hempel JM, Becker A, Muller J, Krause E, Berghaus A, Braun T. Traumatic tympanic membrane perforations: clinical and audiometric findings in 198 patients. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:1357–1362. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31826939b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simsek G, Akin I. Early paper patching versus observation in patients with traumatic eardrum perforations: comparisons. Of anatomical and functional outcomes. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:2030–2032. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lou ZC, He JG. A randomised controlled trial comparing spontaneous healing, gelfoam patching and edge-approximation plus gelfoam patching in traumatic tympanic membrane perforation with inverted or everted edges. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park MK, Kim KH, Lee JD, Lee BD. Repair of large traumatic tympanic membrane perforation with a Steri-strips patch. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:581–585. doi: 10.1177/0194599811409836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choukroun J, Adda F, Schoeffler C, Vervelle A. Une opportunite en paro-implantologie: le PRF. Implantodontie. 2001;42:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dohan DM, Chouknoun J, Diss A, Dohan SL. Platelet rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: technological concepts and evoluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Oral Endod. 2006;101:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part II: platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e45–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erkilet E, Koyuncu M, Atmaca S, Yarım M. Platelet-rich plasma improves healing of tympanic membrane perforations: experimental study. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:482–487. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108003848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvaro MLN, Ortiz N, Rodriguez L, Boemo R, Fuentes JF, Mateo A, Ortiz P. Pilot study on the efficiency of the biostimulation with autologous plasma rich in platelet growth factors in otorhinolaryngology. Otol Surg (Tympanoplasty Type 1) ISRN Surg. 2011;2011:451020. doi: 10.5402/2011/451020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banzer M (1640) Disputatio de auditione laesa. Dissertation on deafness

- 13.Griffin WL., Jr A retrospective study of traumatic tympanic membrane perforations in a clinical practice. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:261–282. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197902000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yearsley J. Deafness practically illustrated. London: Churchill & Sons; 1863. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toynbee J. On the use of an artificial membrana tympani in cases of deafness dependent upon perforations or destruction of the natural organ. London: J. Churchill & Sons; 1853. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roosa DB. Diseases of the ear. New York: William Wood; 1876. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman NC. Chemical closure of chronic tympanic membrane perforations. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:850–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joynt JA. Repair of drum. Iowa Med Soc. 1919;9:51. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derlacki EL. Repair of central perforations of tympanic membrane. Arch Otolaryngol. 1953;58:405. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1953.00710040427003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gun T, Sozen T, Boztepe OF, Gur OE, Muluk NB, Cingi C. Influence of size and site of perforation on fat graft myringoplasty. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2014;41:507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou Z, Wang Y. Evaluation of the optimum time for direct application of fibroblast growth factor to human traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. Growth Factors. 2015;33:65–70. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2014.980905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guneri EA, Tekin S, Yılmaz O, Ozkara E, Erdag TK, Ikiz AO, et al. The effects of hyaluronic acid, epidermal growth factor and mitomycin in an experimental model of acute traumatic tympanic membrane perforation. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:371–376. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Anwar MW, El-Ahl MA, Zidan AA, Yacoup MA. Topical use of autologous platelet rich plasma in myringoplasty. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2015;42:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habesoglu M, Oysu C, Sahin S, Sahin-Yilmaz A, Korkmaz D, Tosun A, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin plays a role on healing of acute-traumatic ear drum perforation. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:2056–2058. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamazaki KIK, Sato H. A clinical study of traumatic tympanic membrane perforation. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2010;113:679–686. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.113.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger G, Finkelstein Y, Harell M. Non-explosive blast injury of the ear. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:395–398. doi: 10.1017/S002221510012688X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.