Abstract

As of common routine in tumor resections, surgeons rely on local examinations of the removed tissues and on the swiftly made microscopy findings of the pathologist, which are based on intraoperatively taken tissue probes. This approach may imply an extended duration of the operation, increased effort for the medical staff, and longer occupancy of the operating room (OR). Mixed reality technologies, and particularly augmented reality, have already been applied in surgical scenarios with positive initial outcomes. Nonetheless, these methods have used manual or marker-based registration. In this work, we design an application for a marker-less registration of PET-CT information for a patient. The algorithm combines facial landmarks extracted from an RGB video stream, and the so-called Spatial-Mapping API provided by the HMD Microsoft HoloLens. The accuracy of the system is compared with a marker-based approach, and the opinions of field specialists have been collected during a demonstration. A survey based on the standard ISO-9241/110 has been designed for this purpose. The measurements show an average positioning error along the three axes of (x, y, z) = (3.3 ± 2.3, − 4.5 ± 2.9, − 9.3 ± 6.1) mm. Compared with the marker-based approach, this shows an increment of the positioning error of approx. 3 mm along two dimensions (x, y), which might be due to the absence of explicit markers. The application has been positively evaluated by the specialists; they have shown interest in continued further work and contributed to the development process with constructive criticism.

Keywords: Computer Assisted Surgery, Microsoft HoloLens, Pattern Recognition, Head and Neck Cancer, Augmented Reality, Visualization, Facial Landmarks, Registration

Introduction

Clinical Requirements

Head and neck cancer (H&NC) management and surgery is still a challenge worldwide. With more than 550,000 new cases and some 300,000 deaths per year, it is the sixth most widely diffused cancer [1]. Despite the frequency of occurrence, H&NC resection requires many complex procedures. As summarized by the American National Institutes of Health (NIH) [2], surgeons currently lack a method to rapidly visualize intraoperatively—if a tumor has correctly been resected. The surgeons rely on the support of pathologists and on local examinations of the removed tissue by means of specialized microscopes [3, 4]. These procedure may involve an extended duration of the surgery, implying more work for the medical staff, a longer occupancy of the operating room (OR), and a higher likelihood of relapses [5].

The complete surgical removal of the tumor masses is of crucial importance in the treatment of head and neck cancer and—as any other manual task—is not exempt from human mistakes [6, 7]. Despite all precautions, errors cannot always be avoided, and for this reason, a clear surgical plan is of great importance. The Canadian Cancer Society forecasts the number of H&NC patients in Canada to rise by 58.9% from the period 2003–2007 to the period of 2028–2032 [8]; against the background of this expected statistical growth, new visualization tools can thus represent a possible help in assuring high standards for the increasing numbers of patients.

Technical Advancements

Mixed reality (MR) technologies, and particularly spatial-aware augmented reality (AR), have the potential to virtually provide a visual control system in surgical scenarios. In recent years, AR has seen a conspicuous diffusion in different fields, whereas medical applications are mostly confined to the research field [9–12]. An AR system for superimposing preoperative scans directly on a patient can help specialists in locating tissues which need to be further examined or removed. A noteworthy example is given by Wang et al. [13], who examined the role of video see-through AR for navigation in maxillofacial surgery; ignoring the intrinsic limitations of video see-through displays, the relatively low accuracy of the object registration is considered as a bottleneck. The majority of recent studies used manual registration, leaving the task of performing a correct alignment to the user [14, 15]. Also for this reason, education and training scenarios currently represent the main target for mixed reality headsets in the medical field [16–18]. A promising application case is medical workflow assistance: an example is given by Hanna et al. [19]; they introduce Microsoft HoloLens in radiological pathology to help specialists in finding metal clips during a biopsy, with an average time reduction of 85.5% compared with the same task performed without electronic assistance.

As for computer-assisted surgery, initial trials for the introduction of spatial-aware AR headsets in a surgical scenario have been reported by Mojica et al. [20], for in situ visualization of MRI scans during neurosurgery with HoloLens, and by Andress et al. [21] who introduce fiducial markers for on-the-fly augmentation of orthopedic surgery. Pioneer trials were made public at the end of 2017 [14], and these were not only for scene augmentation but also for remote support via video streaming [22], which is available on YouTube [23]. Despite the appreciation shown for this development, limitations are reported especially regarding the registration of the 3D models which were performed manually. Interesting approaches are also presented by Cho et al. [24] and Adabi et al. [25]; they use HoloLens for spatial error measurements, mixing image triangulation, and spatial mapping information.

Despite early successes of MR-based medical applications, no work to date has considered the resection of head and neck cancer, either intraoperatively or during preoperational planning. The overall goal of this work is to provide a preliminary evaluation of the degree of aid that a mixed reality headset, e.g., Microsoft Hololens, can provide to a maxillofacial surgeon during a routine operation for tumor removal and also provide an idea for the automatic registration of 3D objects. A comparable study has been performed by Perkins et al. [26] on breast cancer surgery; in this work, we use their results as a reference, to compare the accuracy of the proposed approach.

Materials and Methods

The Software Architecture

An overview of the system is given in Fig. 1: the tasks of image segmentation and volume reconstruction have been implemented in a MeVisLab (https://www.mevislab.de/) application [27–29].

Fig. 1.

The system framework

Using a PET-CT scan, the MeVisLab application segments the volume of interest (VOI) and reconstructs the relative Iso-surface using thresholds [30–35]. The generated 3D mesh is subsequently loaded in the AR application; this was built under Windows 10 Pro 1709 with Visual Studio VS2017 (v151.5.0) to target Microsoft HoloLens and was thus developed in C# using Unity3D (v2017.1.3f1), OpenCV for Unity (v2.2.7), Dlib FaceLandmarkDetector (v1.1.9), and Microsoft HoloToolkit (v1.2017.1.2).

At runtime, the AR application registers the segmented volumes over a person’s face using facial landmark detection.

Image Segmentation and 3D Reconstruction

Multiple studies have already been conducted on head and neck tumor segmentation, but due to its high morphological variance, no single segmentation technique was yet capable to segment the complete volume of all tumors [36]. A simple threshold-based segmentation approach was chosen in this exploratory study. The result of the segmentation was qualitatively evaluated by a senior surgeon who judged the degree of accuracy to be clinically acceptable. A relative threshold value of 29.5 was used for the case shown in Fig. 2 (Note, Figs. 2, 3, and 4 belong to the same patient with two tumors. However, Fig. 2 shows an axial slice where only the “upper” one of the two tumors is visible). Further analyses on image segmentation have been considered as out of scope, also due to the limited resolution of the available HMDs.

Fig. 2.

Segmented PET-CT slice of the patient. The tumor is shown in orange, (for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article)

Fig. 3.

Volume rendering of the original PET-CT

Fig. 4.

Volume rendering of the segmented PET-CT; the tumors are represented in yellow (for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article)

The segmented PET-CT provides enough information for the generation of an Iso-surface (3D mod) of the tumor [37–39]. The 3D models of the tumors are reconstructed from the PET acquisitions, because the surgeons rely on this information when deciding for a therapy and the tumor margins. Due to intrinsic limitations of the headset, the generated meshes most often need to pass through grid reduction steps to guarantee a framerate of 60 fps [40].

In Figs. 3 and 4, the effect of the segmentation on the whole volume is shown. As the thresholding is only applied to the selected VOI, the remaining volume is still rendered to ease the comparison. The VOI is preselected by the surgeon at the stage of segmentation and indicates the spatial extension of the tumor.

Design and Development of AR Scenario

Axis Alignment

To keep the application logic and its description simple, the generated 3D mesh is assumed to satisfy two conditions:

The origin of the axes matches the center of mass,

The orientation is set accordingly, so that the z-axis is parallel to the gaze direction.

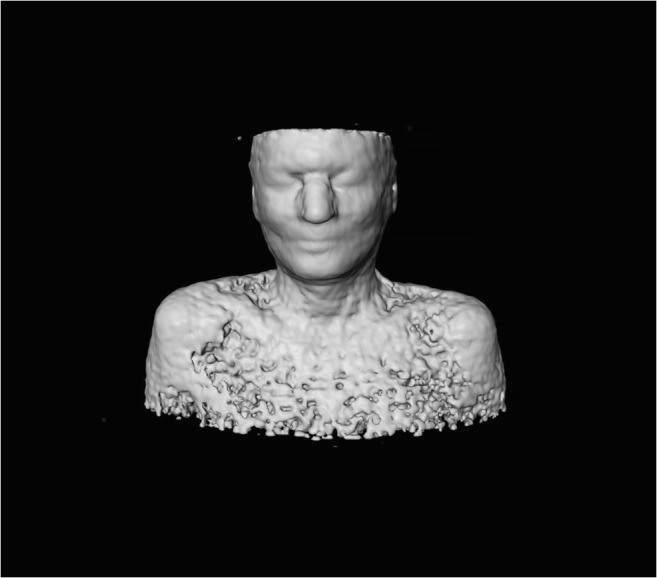

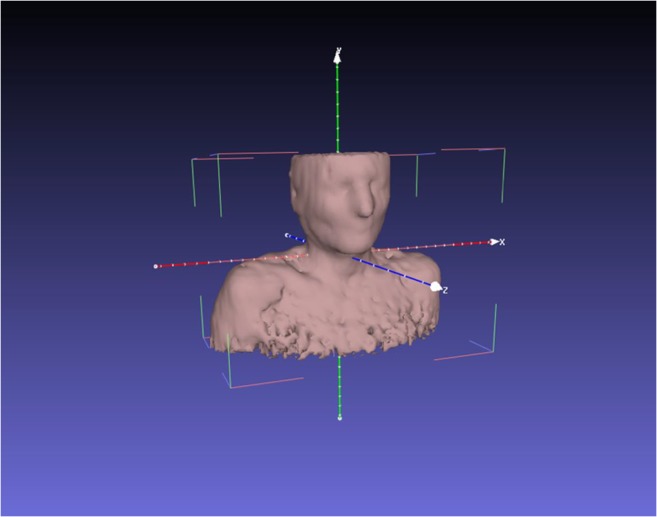

These conditions can be easily checked and adjusted within Unity, or with well-known tools like MeshLab as shown in Fig. 5 [41].

Fig. 5.

Axis visualization in MeshLab

Face Landmarks Detection in MR Environment

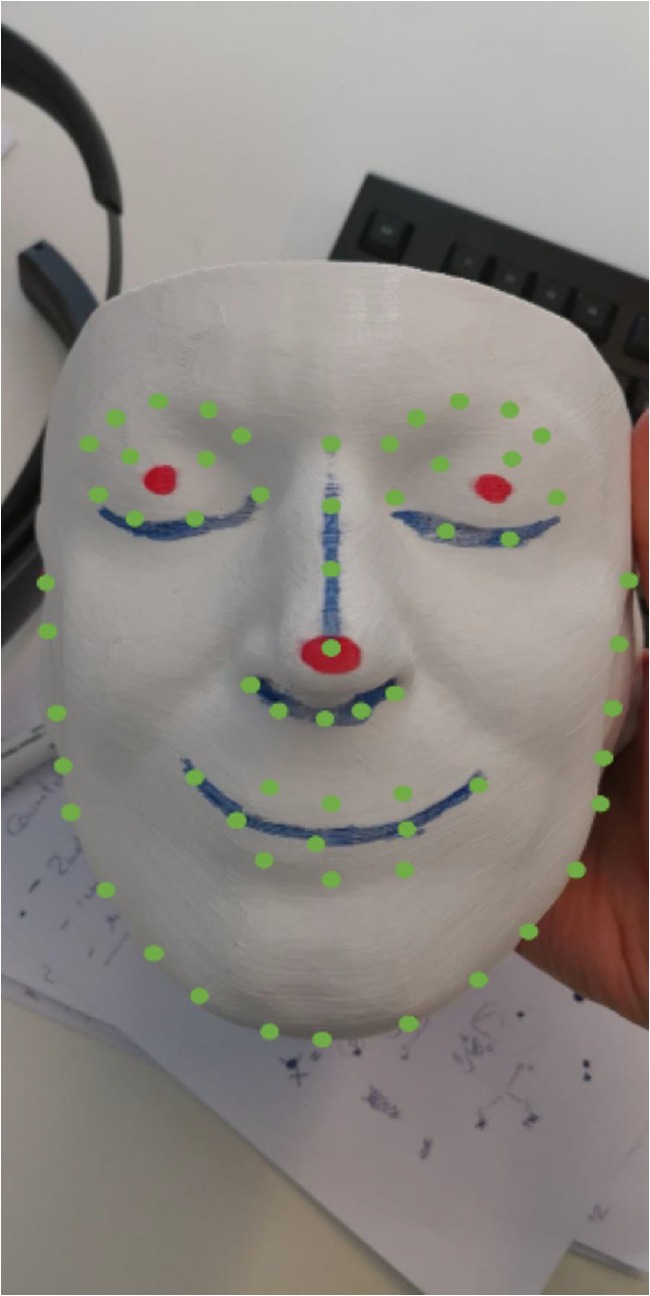

Microsoft HoloLens is equipped with an RGB camera and sensors for environment calibration and reconstruction. The RGB camera only is used in order to recognize the presence of a face. The frames are analyzed with Dlib [42], which offers an implementation of the method suggested by Kazemi and Sullivan for facial landmark detection [43]. This implementation has been chosen for its ease of integration within the framework and its previous applications in the medical field [44]. This method uses a machine learning approach, which is trained using images of actual people; during our experiments, we found that the method is also able to detect colorless, 3D-printed faces. An example of the detected points is shown in Fig. 6, where the blue lines are added for an easier understanding and the red points are later used to measure the registration error.

Fig. 6.

Facial landmarks (in green) detected over a phantom head. The red dots are used to measure the registration error and not related to this stage. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article)

Automatic Registration Procedure

Projection Matrices and Spatial Mapping

The detection algorithm provides information about the 2D pixel-location of defined facial features, e.g., the nose tip. Known transformations are then applied to these points in order to approximate their location in the real world [45]. These transformations depend on the intrinsic camera parameters and the headset location (HL), which is expressed with its 6 degrees of freedom (DoF).

For each feature, the transformed vector D has the same direction as the target point, which can then be retrieved with a ray-cast algorithm in the Spatial Mapping scene [46]. This information can then be used to place the object in the scene, leaving its rotation for the following steps.

Image Processing as Control Step

The described approach can be subject to a non-negligible measurement error (e.g., see Fig. 7). To contain this error, the user would need not only to recalibrate the interpupillary distance of the device at first use but also to let the device further update the spatial reconstruction of the environment which, in some conditions, can be time-consuming.

Fig. 7.

Example of evident positioning error

To compensate the error introduced by the spatial reconstruction, a control step based on triangle similarity has been introduced [24, 25]. Since the size of the head concerned is known from the PET-CT scan, it is worth considering the application of triangle similarity for distance evaluation [47–49].

This method only provides information about the magnitude of the distance from the camera location; no information is given about its direction. The direction information is retrieved applying the transformation matrices. The result of the triangulation is then averaged with the spatial mapping. The RGB camera and the (patient) face need to face each other about the same direction, otherwise the progress will fail. This is only needed for the initial registration, and the virtual object can then be anchored to the world, until the patient is moved.

An example of a completed registration is shown in Fig. 8: the red points marked on the printed model (Fig. 6) are completely overlapped by the green points of the virtual model. In this case, the two small yellow elements represent the tumors, while the bigger horizontal element depicts a section of the PET-CT scan to be used as a reference to monitor the location.

Fig. 8.

Example of a registration with negligible error

Camera-Based Automatic Orientation

The discussed method does not provide any information regarding the rotation. Taking the approaches used in commercial applications into consideration [50], this problem has been addressed using the face landmarks, the RGB camera parameters, and their 6-DoF position. This information can be used to define a Perspective-n-Point (PNP) problem, which can be solved with a direct linear transformation [51, 52] and the Levenberg-Marquardt optimization algorithm [53–55]. An implementation of this approach is provided by OpenCV.

Experiment Scenario

Although the system is designed for working in any environment, a test-bed has been reconstructed. The rendering was tested over a 3D-printed version of a patient CT scan, which was laid over a green surface to simulate the environment of an operating room (see Figs. 8 and 9).

Fig. 9.

An image from the showcase at the hospital

To obtain the reproduced phantom, the Iso-surface of the CT scan was first converted to the STL (Standard Triangulation Language) format which was post-processed manually in the MeshLab. The result was then printed with the MakerBot Replicator+ using a PLA filament. All data set files (.stl, CT, PET) are freely available for download (please cite our work if you use them) [56]:

Please note in addition that all data sets were completely anonymized before their use in this study; any patient-specific information from the medical records was deleted during the anonymization process and before the data selection was performed. De-identified data only was used in this study, and an approval has been provided for it by the internal review board (IRB) of the university (IRB: EK-29-143 ex 16/17, Medical University of Graz, Austria). Since all data are internal from the university clinic (Medical University of Graz), the data can be used retrospectively and in de-identified form for research and other scientific purposes. Under these conditions, the ethics committee/IRB has waived the requirement for informed consent.

Results

Technical Results

The error measured with and without user calibration has been reported in Tables 1 and 2. The values represent the distance between the red reference points and the green virtual points, measured by the introduction of a ruler with millimeter precision as in [26]. In both cases, the measurements were repeated four times at an approximate distance of 80 cm from the target. An experienced user was involved during the four measurements; she had to change her position to measure the error along the z-direction and to obtain a rotation of the view of approx. 90° along the y-axis.

Table 1.

Error of the automatic registration after user calibration

| Error along the y-axis (up-down dimension) (mean ± standard deviation) | − 4.5 ± 2.9 mm |

| Error along the x-axis (right-left dimension) (mean ± standard deviation) | 3.3 ± 2.3 mm |

| Error along the z-axis (back-front dimension) (mean ± standard deviation) | − 9.3 ± 6.1 mm |

Table 2.

Error of the automatic registration without user calibration

| Error along the y-axis (up-down dimension) (mean ± standard deviation) | − 12.5 ± 2.5 mm |

| Error along the x-axis (right-left dimension) (mean ± standard deviation) | 7.0 ± 2.1 mm |

| Error along the z-axis (back-front dimension) (mean ± standard deviation) | − 19.0 ± 2.0 mm |

Clinical Feedback

Two demonstrative sessions took place, the first at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery of the Medical University of Graz in Austria and the second at the Institute of Computer Graphics and Vision of Graz University of Technology. The intention of these sessions was the obtaining of opinions and suggestions from various different experts, in order to address future development steps adequately and comprehensively.

During the first showcase, six medical experts participated: two nurses and four surgeons. Each participant had to repeat the registration ex novo. All of these experts showed interest in and appreciation for the technology, has and their responses have been quantified using a questionnaire based on the standard ISO-9241/110 (Table 3). Each question had to be anonymously answered using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

Table 3.

ISO-9241/110-based questionnaire and relative answers given by the medical staff

| Question | Median answer | Interquartile range | χ2 test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The software is easy to use | 4.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 2. The software is easy to understand without prior training | 4.5 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 3. The software is easy to understand after an initial training | 4.5 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 4. The software offers all the necessary functionalities (the minimum requirements are met) | 3.5 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 5. The software successfully automates repetitive tasks (minimal manual input) | 4.0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| 6. The way of interaction is uniform through the operation cycle | 4.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 7. The introduction of the software could considerably reduce the overall operation time (or manual tasks) | 3.5 | 2 | 0.10 |

| 8. The introduction of the software might increase the quality of the operation (e.g., lower risk of failures, …) | 5.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 9. The introduction of a similar software in a surgery room could be beneficial | 5.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 10. The software would be helpful for educational purposes | 5.0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| 11. The software could be helpful in an ambulatory and/or doctor’s office | 5.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 12. I am an expert in the medical field | 5.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 13. I am an expert in the field of human-computer interaction | 3.0 | 2 | 0.41 |

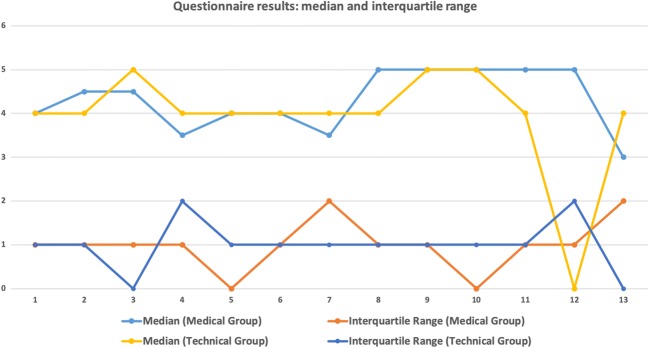

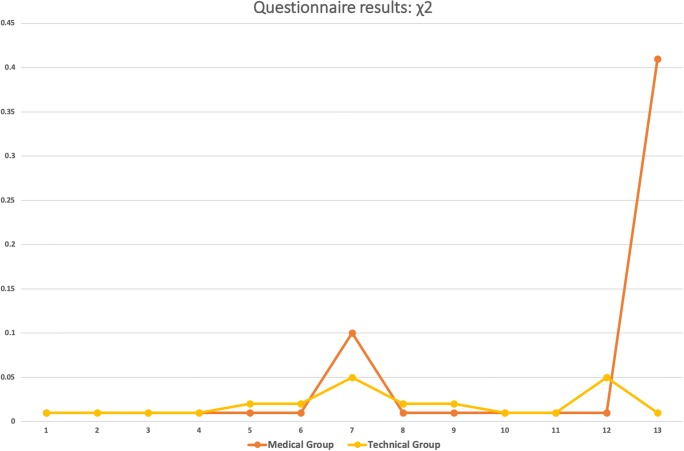

The questionnaire was then also presented to technical experts (Table 4). Some of these explicitly stated that they wished to make no responses to the medical-related questions as they were not comfortable with these. This group consisted of seven persons: one professor, two senior researchers, and four PhD students. Figures 10 and 11 show a graphical visualization of these results.

Table 4.

ISO-9241/110-based questionnaire and answers given by the experts in mixed reality

| Question | Median answer | Interquartile range | χ2 test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The software is easy to use | 4.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 2. The software is easy to understand without prior training | 4.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 3. The software is easy to understand after an initial training | 5.0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| 4. The software offers all the necessary functionalities (the minimum requirements are met) | 4.0 | 2 | 0.01 |

| 5. The software successfully automates repetitive tasks (minimal manual input) | 4.0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 6. The way of interaction is uniform through the operation cycle | 4.0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 7. The introduction of the software could considerably reduce the overall operation time (or manual tasks)a | 4.0 | 1 | 0.05 |

| 8. The introduction of the software might increase the quality of the operation (e.g., lower risk of failures, …)a | 4.0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 9. The introduction of a similar software in a surgery room could be beneficial | 5.0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 10. The software would be helpful for educational purposes | 5.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 11. The software could be helpful in an ambulatory and/or doctor’s office | 4.0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 12. I am an expert in the medical field | 0.0 | 2 | 0.05 |

| 13. I am an expert in the field of human-computer interaction | 4.0 | 0 | 0.01 |

aThis question was considered as optional

Fig. 10.

Graphical visualization of median and interquartile range. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article)

Fig. 11.

Graphical visualization of the χ2 test. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article)

Discussion

Technical Results

In order to compare the performance of the proposed system, a marker-based approach has been used as a reference [26].

Analyzing the errors from Table 1, calibration is a necessary step for automatic registration. In this case, it was possible to reduce the error by half when comparing the results with Table 2. This step would thus need to be taken into consideration during the preplanning of an operation.

Furthermore, as could be expected, the use of facial landmarks as markers appears to diminish the accuracy of the system. No comparison can be made in terms of the back-front dimension (depth), as this was not tested in the reference study. At all events, this would appear to be the most relevant shortcoming of the device: as of today, it is not possible to rely on depth information on a millimeter scale, which forces the specialist to look at the 3D model only from given directions. Nonetheless, a higher average registration error was expected given that the face detection algorithm introduces an artificial noise, because it is based on a heuristic approach.

In addition, lower average errors are registered when the study is compared with the marker-less video see-through AR system [57]; this could be due to the introduction of the integrated spatial understanding capabilities in the HoloLens display, which avoid the necessity to synchronize the display with a third device, an ad hoc synchronization that can lead to a higher overall measurement error. Further work is to be addressed in this direction, as the newer API provides simultaneous access to both RGB and depth images.

Clinical Feedback

All the participants felt in general terms comfortable with the application, although the first group needed an initial training session to familiarize themselves with the device. The overall feedback provided is seen as positive for the introduction of the technology in operating rooms and ambulatories. All the experts expressed the wish for an additional visualization of spatial information for bones and blood vessels. The maximum positive feedback was given unanimously to the question of whether the study participants would introduce the application in an educational environment for surgical training, which may suggest that the technology offers sufficient reliability for this purpose.

It is also interesting to analyze questions seven, eight, and nine together: although the responses agree on the benefits the application could bring in an operating theater, they also consider it to be more of a quality assurance tool than a time saving method.

Further considerations emerged from comparing both Tables 3 and 4: although all participants agree that the system is easy to use and understand, it can be noticed that the engineers find it simpler to use. The application content would appear to be suitable for the medical staff, subject to them first receiving basic training on the technology.

Conclusions

In the proposed work, a marker-less mixed reality application for maxillofacial oncologic surgery support has been introduced and evaluated. The tests focused on a recreated case of head and neck cancer, under the supervision of a facial surgeon from the Medical University of Graz. In order to create a test-bed, a 3D model of the patient’s head was 3D-printed. The registration of the 3D model is achieved automatically using facial landmarks detection.

A questionnaire was provided to a group of experts during a showcase presentation. The answers were used to understand and establish the usefulness of such a system in medical environments. The questionnaire was drafted according to the recommendation of the standard ISO-9241/110 Ergonomics of Human-Machine Interaction. The outcome of this survey is that surgeons generally show great interest in and appreciation for this technology, in particular for the potential it has for ensuring higher quality standards.

The same showcase was then proposed to researchers at the Institute of Computer Graphics and Vision of the Graz University of Technology, in order to compare the reactions of biomedical and computer engineers with those of the physicians.

This revealed how a profound knowledge of mixed reality is not necessary to correctly and intuitively understand the application, but it is necessary to have at least a basic knowledge in the target medical field in order to understand not only the behavior of the application but also the information provided by its content.

Our measured errors of the device are in line with what were declared by the manufacturer. Nonetheless, in previous clinical studies, this alignment has been performed manually. In this study, we evaluate a computer vision approach for automatic alignment. In our evaluation, we did not plan to provide the surgeon with an all-in-one tool, due to the limited resolution of the device. This may be possible with upcoming devices, like the HoloLens 2. Nevertheless, we aimed at a support tool and for higher precision the operative microscope should be used.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the team Kalkofen at the Institute of Computer Graphics and Vision, TU Graz, for their support.

Funding Information

This work received funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) KLI 678-B31: “enFaced: Virtual and Augmented Reality Training and Navigation Module for 3D-Printed Facial Defect Reconstructions” (Principal Investigators: Drs. Jürgen Wallner and Jan Egger), the TU Graz Lead Project (Mechanics, Modeling and Simulation of Aortic Dissection), and CAMed (COMET K-Project 871132), which is funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Transport, Innovation and Technology (BMVIT) and the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs (BMDW) and the Styrian Business Promotion Agency (SFG).

Footnotes

Antonio Pepe and Gianpaolo Francesco Trotta are joint first authors.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jürgen Wallner, Vitoantonio Bevilacqua, and Jan Egger are joint senior authors.

References

- 1.Wiesenfeld D. Meeting the challenges of multidisciplinary head and neck cancer care. Int J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;46:57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2017.02.210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institutes of Health, Technologies Enhance Tumor Surgery: Helping Surgeons Spot and Remove Cancer, News In Health, 2016

- 3.Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Wang HH, Longtine JA, Dvorak A, Dvorak HF: Role of the Surgical Pathologist in the Diagnosis and Management of the Cancer Patient, 6th edition, Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine, 2003

- 4.Kuhnt D, et al. Fiber tractography based on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) compared with high angular resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI) with compressed sensing (CS)–initial experience and clinical impact. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:A165–A175. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318270d9fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCahill LE, Single RM, Aiello Bowles EJ, et al. Variability in reexcision following breast conservation surgery. JAMA. 2012;307:467–475. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harréus U: Surgical Errors and Risks-The Head and Neck Cancer Patient, GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology. Head Neck Surg 12, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Stranks J. Human Factors and Behavioural Safety. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2007. pp. 130–131. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics . Canadian Cancer Statistic 2015. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunkel N, Soechtig S: Mixed Reality: Experiences Get More Intuitive, Immersive and Empowering. Deloitte University Press, 2017

- 10.Coppens A, Mens T. Merging Real and Virtual Worlds: An Analysis of the State of the Art and Practical Evaluation of Microsoft Hololens. Mons: University of Mons; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uva AE, Fiorentino M, Gattullo M, Colaprico M, De Ruvo MF, Marino F, Trotta GF, Manghisi VM, Boccaccio A, Bevilacqua V, Monno G. Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics. Berlin: Springer; 2016. Design of a projective AR workbench for manual working stations; pp. 358–367. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, et al. Development of a surgical navigation system based on augmented reality using an optical see-through head-mounted display. J Biomed Inform. 2015;55:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Junchen, Suenaga Hideyuki, Yang Liangjing, Kobayashi Etsuko, Sakuma Ichiro. Video see-through augmented reality for oral and maxillofacial surgery. The International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery. 2016;13(2):e1754. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt P, Ives M, Lawton G, Simmons J, Radev N, Spyropoulou L, Amiras D. Through the HoloLens™ looking glass: augmented reality for extremity reconstruction surgery using 3D vascular models with perforating vessels. Eur Radiol Exp. 2018;2:2018. doi: 10.1186/s41747-017-0033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanna Matthew G., Ahmed Ishtiaque, Nine Jeffrey, Prajapati Shyam, Pantanowitz Liron. Augmented Reality Technology Using Microsoft HoloLens in Anatomic Pathology. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2018;142(5):638–644. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0189-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sappenfield Joshua Warren, Smith William Brit, Cooper Lou Ann, Lizdas David, Gonsalves Drew B., Gravenstein Nikolaus, Lampotang Samsun, Robinson Albert R. Visualization Improves Supraclavicular Access to the Subclavian Vein in a Mixed Reality Simulator. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2018;127(1):83–89. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SYED A.Z., ZAKARIA A., LOZANOFF S. DARK ROOM TO AUGMENTED REALITY: APPLICATION OF HOLOLENS TECHNOLOGY FOR ORAL RADIOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 2017;124(1):e33. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2017.03.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lia H, Paulin G, Yeo CY, Andrews J, Yi N, Hag H, Emmanuel S, Ludig K, Keri Z, Lasso A, Fichtinger G: HoloLens in suturing training, SPIE Medical Imaging 2018: Image-guided procedures, Robotic Interventions, and Modeling, vol. 10576, 2018

- 19.Hanna MG, Worrell S, Ishtiaque A, Fine J, Pantanowitz L. Pathology specimen radiograph co-registration using the HoloLens improves physician assistant workflow. Pittsburgh: Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine-Innovating Imaging Informatics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mojica CMM, Navkar NV, Tsagkaris D, Webb A, Birbilis TA, Seimenis I, TsekosNV: Holographic interface for three-dimensional visualization of MRI on HoloLens: a prototype platform for MRI Guided Neurosurgeries, IEEE 17th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering, 2017, pp 21–27

- 21.Andress S, et al. On-the-fly augmented reality for orthopaedic surgery using a multi-modal fiducial. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2018;5(2):021209. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.5.2.021209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luce P, Chatila N: AP-HP: 1ère intervention chirurgicale au monde à l’hôpital Avicenne réalisée avec une plateforme collaborative de réalité mixte, en interaction via Skype avec des équipes médicales dans le monde entier, grâce à HoloLens, Hub Presse Microsoft France, 05 12 2017. [Online]. Available: https://news.microsoft.com/fr-fr/2017/12/05/ap-hp-1ere-intervention-chirurgicale-monde-a-lhopital-avicenne-realisee-hololens-plateforme-collaborative-de-realite-mixte-interaction-via-skype-equipes-med/. Accessed 05 11 2018

- 23.Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Opération de l’épaule réalisée avec un casque de réalité mixte - hôpital Avicenne AP-HP, APHP, 05 12 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xUVMeib0qek. Accessed 04 11 2018

- 24.Cho K, Yanof J, Schwarz GS, West K, Shah H, Madajka M, McBride J, Gharb BB, Rampazzo A, Papay FA: Craniofacial surgical planning with augmented reality: accuracy of linear 3D cephalometric measurements on 3D holograms. Int Open Access J Am Soc Plast Surg 5, 2017

- 25.Adabi K, Rudy H, Stern CS, Weichmann K, Tepper O, Garfein ES. Optimizing measurements in plastic surgery through holograms with Microsoft Hololens. Int Open Access J Am Soc Plast Surg. 2017;5:182–183. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perkins S, Lin MA, Srinivasan S, Wheeler AJ, Hargreaves BA, Daniel BL: A mixed-reality system for breast surgical planning, in IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct Proceedings, Nantes, 2017

- 27.Egger J, et al. Integration of the OpenIGTLink Network Protocol for image-guided therapy with the medical platform MeVisLab. Int J Med Rob. 2012;8(3):282–290. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger J, et al. HTC Vive MeVisLab integration via OpenVR for medical applications. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger J, et al. GBM volumetry using the 3D slicer medical image computing platform. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1364. doi: 10.1038/srep01364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bevilacqua V. Three-dimensional virtual colonoscopy for automatic polyps detection by artificial neural network approach: New tests on an enlarged cohort of polyps. Neurocomputing. 2013;116:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2012.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bevilacqua V, Cortellino M, Piccinni M, Scarpa A, Taurino D, Mastronardi G, Moschetta M, Angelelli G. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Berlin: Springer; 2009. Image processing framework for virtual colonoscopy, in Emerging Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications. ICIC 2009; pp. 965–974. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bevilacqua V, Mastronardi G, Marinelli M. International Conference on Intelligent Computing. Berlin: Springer; 2006. A neural network approach to medical image segmentation and three-dimensional reconstruction; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zukic D, et al: Segmentation of vertebral bodies in MR images, Vision, Modeling, and Visualization, 2012, pp 135-142

- 34.Zukić D, et al. Robust detection and segmentation for diagnosis of vertebral diseases using routine MR images. Computer Graphics Forum. 2014;33(6):190–204. doi: 10.1111/cgf.12343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bevilacqua V, Trotta GF, Brunetti A, Buonamassa G, Bruni M, Delfine G, Riezzo M, Amodio M, Bellantuono G, Magaletti D, Verrino L, Guerriero A. Italian Workshop on Artificial Life and Evolutionary Computation. Berlin: Springer; 2016. Photogrammetric meshes and 3D points cloud reconstruction: a genetic algorithm optimization procedure; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schinagl DA, Vogel WV, Hoffmann AL, van Dalen JA, Oyen WJ, Kaanders JH. Comparison of five segmentation tools for 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose–positron emission tomography–based target volume definition in head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2007;69:1282–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumgart BG: A polyhedron representation for computer vision. In Proceedings of the May 19-22, 1975, national computer conference and exposition, ACM, 1975, pp 589–596

- 38.Bosma, M. K., Smit, J., & Lobregt, S. (1998). Iso-surface volume rendering. In Medical Imaging 1998: Image Display. International Society for Optics and Photonics, vol 3335, pp 10–20

- 39.Egger Jan, Gall Markus, Tax Alois, Ücal Muammer, Zefferer Ulrike, Li Xing, von Campe Gord, Schäfer Ute, Schmalstieg Dieter, Chen Xiaojun. Interactive reconstructions of cranial 3D implants under MeVisLab as an alternative to commercial planning software. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0172694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner A, Zeller M, Cowley E, Brandon B: Hologram stability, 21 03 2018. [Online]. Available: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/mixed-reality/hologram-stability. Accessed 05 11 2018

- 41.Visual Computing Laboratory, MeshLab, CNR, [Online]. Available: http://www.meshlab.net/. Accessed 05 11 2018

- 42.Dlib C++ library, [Online]. Available: http://www.dlib.net. Accessed 02 11 2018

- 43.Kazemi V, Sullivan J: One millisecond face alignment with an ensemble of regression trees, in IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 2014

- 44.Bevilacqua V, Uva AE, Fiorentino M, Trotta GF, Dimatteo M, Nasca E, Nocera AN, Cascarano GD, Brunetti A, Caporusso N, Pellicciari R, Defazio G. International conference on recent trends in image processing and pattern recognition. Berlin: Springer; 2016. A comprehensive method for assessing the blepharospasm cases severity; pp. 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guyman W, Zeller M, Cowley E, Bray B: Locatable camera, Microsoft - Windows Dev Center, 21 03 2018. [Online]. Available: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/mixed-reality/locatable-camera. Accessed 05 11 2018

- 46.Unity Technologies, Physics Raycast, 04 04 2018. [Online]. Available: https://docs.unity3d.com/ScriptReference/Physics.Raycast.html. Accessed 05 11 2018

- 47.Salih Y, Malik AS: Depth and geometry from a single 2D image using triangulation, in IEEE international conference on multimedia and expo workshops, 2012.

- 48.Alizadeh P. Object distance measurement using a single camera for robotic applications. Sudbury: Laurentian University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holzmann C, Hochgatterer M: Measuring distance with mobile phones using single-camera stereo vision, IEEE Computer Society, 2012, pp 88–93

- 50.Enox Software, Dlib FaceLandmark Detector, Enox Software, 31 01 2018. [Online]. Available: https://assetstore.unity.com/packages/tools/integration/dlib-facelandmark-detector-64314. Accessed 05 11 2018

- 51.Abdel-Aziz YI, Karara HM: Direct linear transformation into object space coordinates in close-range photogrammetry, Proc. Symposium on Close-Range Photogrammetry, 1971, pp 1–18

- 52.Seedahmed G, Schenk AF: Direct linear transformation in the context of different scaling criteria, in In Proc. ASPRS. Ann. Convention, St. Louis, 2001

- 53.Levenberg K. A method for the solution of certain non-linear problems in least squares. Q Appl Math. 1944;2(2):164–168. doi: 10.1090/qam/10666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marquardt DW. An algorithm for the least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. SIAM J Appl Math. 1963;11(2):431–441. doi: 10.1137/0111030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.OpenCV Dev Team, Camera Calibration and 3D Reconstruction, 02 11 2018. [Online]. Available: https://docs.opencv.org/2.4/modules/calib3d/doc/camera_calibration_and_3d_reconstruction.html. Accessed 04 11 2018

- 56.J. Egger, J. Wallner, 3D printable patient face and corresponding PET-CT data for image-guided therapy, Figshare, 2018. 10.6084/m9.figshare.6323003.v1

- 57.Hsieh C-H, Lee J-D: Markerless augmented reality via stereo video see-through head-mounted display device. Math Probl Eng 2015, 2015