Abstract

Purpose:

Early activation of cytosolic NADPH oxidase-2 (Nox2) in diabetes increases retinal ROS production, damaging their mitochondria. The assembly of Nox2 holoenzyme requires activation of a small molecular weight G-protein Rac1. Rac1 activation is regulated by guanine exchange factors) and guanine nucleotide-dissociation inhibitors, and post-translational modifications assist in its association with exchange factors and dissociation inhibitors. The goal of this study is to investigate the mechanisms of Rac1 activation in the development of diabetic retinopathy.

Methods:

The levels of dissociation inhibitor, prenylating enzyme (farnesyltransferase, FNTA) and exchange factor Vav2 were quantified in the human retinal endothelial cells, incubated in normal or high glucose for 96 hours. Role of prenylation and Vav2 in Rac1-Nox2-ROS-mitochondrial damage was confirmed in FNTA-siRNA transfected cells and using Vav2 inhibitor EHop, respectively. Retinal histopathology and functional changes associated with diabetic retinopathy were analyzed in diabetic mice receiving EHop for six months. Key parameters of Rac1 activation were confirmed in the retinal microvasculature from human donors with diabetic retinopathy.

Results:

In HRECs, glucose increased FNTA and Vav2, and decreased dissociation inhibitor. FNTA-siRNA and EHop inhibited glucose-induced activation of Rac1-Nox2-ROS signaling. In diabetic mice, EHop ameliorated the development of retinopathy and functional/structural abnormalities, and attenuated Rac1-Nox2-mitochondrial damage. Similar alterations in Rac1 regulators were observed in retinal microvasculature from human donors with diabetic retinopathy.

Conclusions:

In diabetes, Rac1 prenylation and its interactions with Vav2 contribute to Nox2-ROS-mitochondrial damage, and the pharmacological inhibitors to attenuate Rac1 interactions with its regulators could have potential to halt/inhibit the development of diabetic retinopathy.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, NADPH oxidase, Oxidative stress, Post-translational modifications, Rac1

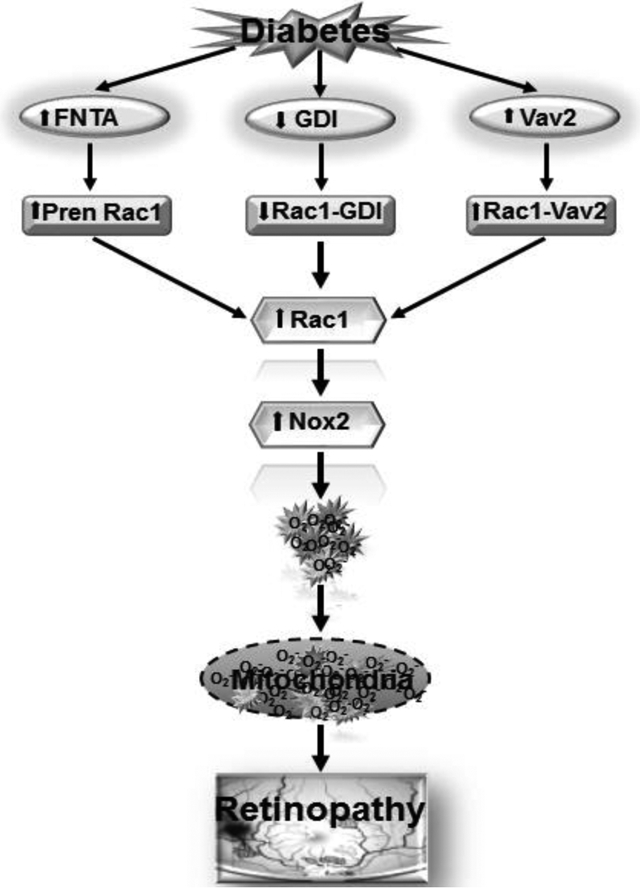

Graphical Abstract

Activation of prenylating enzyme farnesyltransferase (FNTA) in diabetes, prenylates Rac1. The binding of Rac1 with guanine nucleotide-dissociation inhibitor (GDI) is decreased, but its association with the guanine exchange factor, Vav2, is increased, resulting in Rac1 activation. Active Rac1 helps in the assembly of Nox2 holoenzyme, and Nox2 activation increases cytosolic ROS production, damaging the mitochondria. Damaged mitochondria accelerates capillary cell apoptosis, and ultimately, results in the development of diabetic retinopathy.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic retinopathy is the major blinding disease among working age adults, but the molecular mechanism(s) of this progressing disease remains obscure. Diabetes alters many metabolic pathways in the retina and its vasculature, oxidative stress is increased, and the mitochondria are damaged [1–3]. Experimental models have documented that increase in cytosolic reactive oxygen species (ROS) precedes mitochondrial damage-capillary cell apoptosis and the histopathology characteristic of diabetic retinopathy [4]. Phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase-2 (Nox2) is considered as one of the major sources of cytosolic ROS, and in diabetes, this enzyme is activated in the retinal vasculature [5]. Nox2 is a multi-component enzyme, and one of the most critical members of this holoenzyme is a small molecular weight G protein, elated C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) [6, 7]. In diabetes, Rac1 is functionally and transcriptionally activated, and Rac1 promoter is epigenetically modified [4, 8]. Activated Rac1, viaNox2, increases cytosolic ROS, and damages the mitochondria, which initiates the apoptotic machinery, and accelerates apoptosis of retinal capillary cells [4, 9]. Rac1shuttles between its inactive (GDP bound) and active (GTP bound) forms, and Rac1activation is essential for its movement to the membrane for Nox2 activation [7].

Activation of Rac1 is mediated by at least three distinct families of proteins, namely guanine exchange factors (GEFs), GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide-dissociation inhibitors (GDIs). While GEFs facilitate membrane localization of Rac1, GDIs regulate access of Rac1 to the GEFs [10]. Association of Rac1 with GDIs is assisted by post-translational modification including palmitolyation and prenylation [11, 12]. These modifications increase the hydrophobicity of Rac1, enabling it to translocate to the membrane for the formation of Nox2 holoenzyme, and its activation [13–15]. However, how diabetes affects the post-translational modification of Rac1-GDIs is unclear.

Guanine nucleotide exchange factors, especially Tiam1 and Son of Sevenless 1 (Sos1), are intimately associated with the activation of Rac1-Nox2 in the development of diabetic retinopathy [4, 16]. Activation of Rac1, however, is also mediated by other GEF’s, and Vav2 is considered as another important GEF for Rac1 activation [17, 18], and functional inactivation of Vav2 is shown to attenuate sustained activation of Rac1-Nox2 signaling in beta cells of islets [19]. The role of Vav2 in the activation of retinalRac1 in diabetes is not known.

The goal of this study is to investigate putative mechanisms underlying the activation of Rac1 in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Using experimental models (in vitro and in vivo) and retinal microvasculature from human donors with documented diabetic retinopathy, we have investigated the effect of prenylation on Rac1 activation. We have also investigated the roles of Vav2 in the regulation of Rac1-Nox2-ROS signaling, and the development structural and functional changes associated with diabetic retinopathy in a diabetic mouse model.

METHODS

Retinal endothelial cells:

Primary human retinal endothelial cells (HRECs) were purchased from Cell Systems Corporation (Cat. No. ACBRI 181, Cell Systems Corp, Kirkland, WA, USA). These cells were characterized using immunostaining for Von Willebrand Factor. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM)-F12 supplemented with 15μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, and 1% each insulin- transferrin- selenium-Glutamax and antibiotic/antimycotic [8]. HRECs from the 6th-9th passage were incubated in normal (5mmols/L, NG) or high (20mols/L, HG) D-glucose for 96 hours in the presence or absence of a small molecule inhibitor of Vav2, 5μmols/L Ehop-016 (EHop, Cat no. SML0526; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO). A group of cells was transfected with the siRNA of prenylation enzyme farnesyltransferase, FNTAIa-siRNA (Cat. No. 4390824, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), employing lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Cat. No. 13778030, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). After the transfection, the cells were incubated in NG or HG media for 96 hours [8, 16, 20, 21]. Parallel incubations with non-targeting scrambled RNA, or with reagent alone, were used as controls. In each experiment, L-glucose (L-Glu) at 20mmols/L, instead of 20mmols/L D-glucose, was used as an osmolarity/metabolic control.

Animal model:

Diabetes was induced in 7–9 weeks old C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) by streptozotocin (55 mg/kg BW) administration for four consecutive days. The mice presenting blood glucose >250 mg/dL, 2 days after the last injection were considered diabetic [8, 22], this model represents type 1 diabetes. Diabetic mice were divided into two groups, while group 1 received intraperitoneal administration of EHop (25mg/kg BW/day), group 2 mice did not receive any treatment [23]. Six months after induction of diabetes, the animals were sacrificed and their retina was collected. Age-matched normal mice were used as controls. The treatment of animals conformed to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and was approved by the Wayne State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Human donors:

Eyes from human donors with clinically documented diabetic retinopathy, enucleated within 5–6 hours of death, were obtained from the Eversight Eye Bank, Ann Arbor, MI; these eye globes were enucleated within 8 hours of death. Donors ranged from 45 to 75 years of age, and over 75% of them had type 2 diabetes and the duration of diabetes was from 10 to 35 years. Eye globes from age-matched nondiabetic donors were used as controls [24]. These globes were coded by the Eye Bank, and did not reveal any patient identification.

Retinal microvessels:

Retinal microvessesl were prepared by incubating freshly isolated retina in distilled water for 1 hour at 37°C in a shaker water bath. The nonvascular tissue was gently removed under a dissecting microscope using a Pasteur pipette, as reported previously [9]. The microvessels were then rinsed with PBS, and used for analysis. The entire retina from a mouse eye, or 1/8th to 1/5th of the temporal retina from human samples was utilized for each microvessel preparation.

Gene transcripts:

Total RNA, was isolated with TRIZOL reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and cDNA was synthesized from 1μg RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR green master mix and the gene/species-specific primers (Table I). SYBR green single melt curve analysis was performed to confirm the specific products. β-actin (human) or 18S (mice) were used as the housekeeping gene, and the relative fold change was calculated using delta delta Ct method [8, 16].

Table I.

Primer sequences

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Human | |

| FNTA | Fwd- GACTCGCCCTCCTATGTCCT |

| Rev- TGATCTGGACCACGG GATTG | |

| Cytb | Fwd- TCACCAGACGCCTCAACCGC |

| Rev- GCCTCGCCCGATGTGTAGGA | |

| Vav2 | Fwd- GACGTCAAGAAGTCTCACGGG |

| Rev- GGAAGCCCTGCTTTCCTTGA | |

| GDI | Fwd- GCCTACGGCTATCCTCGC |

| Rev- CTCAAGCTTAGCCTGGGTCG | |

| β-Actin | Fwd- AGCCTCGCCTTTGCCGATCCG |

| Rev- TCTCTTGCTCTGGGCCTCGTCG | |

| Mouse | |

| Cytb | Fwd- CCCATTCATTATCGCCGCCC |

| Rev- GGTCTCCTAGTAGGTCTGGG | |

| 18s | Fwd- GCCCTGTAATTGGAATGAGTCCACTT |

| Rev- CTCCCCAAGATCCAACTACGAGCTTT | |

Western blotting:

Protein expression was determined in 30–40μg protein by western blotting technique using antibodies against FNTA (Cat No. ab186136, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, 1:1000 dilution), GDI (Cat No. sc-373724, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:500 dilution) and Vav2 (Cat No.ab52640, Abcam; 1:1000 dilution). β-Actin (Cat No. A5441, Sigma Aldrich; 1:2000 dilution) was employed as the loading control.

Rac1 activity:

Active Rac1 was quantified by G-LISA colorimetric assay kit (Cat No. BK-128; Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO), employing 20–25μg protein [4, 8]. Fold change was calculated considering the values obtained from cells in normal glucose, or nondiabetic mice, as 100%.

Nox2 activity:

Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay was performed in 10μg protein using lucigenin (25μmols/L, Cat No. M8010, Sigma-Aldrich) as an electron acceptor and 200μM NADPH as substrate, in the presence or absence of 0.2mmols/L apocynin [25].

Reactive oxygen species:

Total ROS levels were quantified in 4–6μg protein using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; catalog no. D6883; Sigma-Aldrich). Values obtained from cells in NG were considered as 100% [7].

Immunofluorescence:

The cellular localization of Rac1 and GDI was performed by immunofluorescence technique using primary antibodies against Rac1 (Cat No. PA1–091x, Life Technologies; 1:200), and GDI (Cat No. sc-373724, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:100 dilution) [16]. For Rac1 and Vav2 cellular localization was performed using primary antibodies against Rac1 (Cat No. ab33186, Abcam; 1:200 dilution), and Vav2 (Cat No. ab52640, Abcam; 1:200 dilution). Secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated anti-rabbit (Cat No.A11008, Molecular Probes-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NE; 1:500 dilution) or Texas red-conjugated (Cat No.TI200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA; 1:500 dilution). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) containing mounting medium (blue) (Vector Laboratories) was used to visualized nucleus. The cells were examined under Leica SP5 confocal microscope at 63 x magnifications (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Cell death:

Cell death was determined using Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS kit (Cat. No. 11774425001, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) [16]. The results were calculated as fold change considering the values obtained from cells in normal glucose as 100%.

Histopathology and TUNEL staining in mouse retinal microvasculature

The eyes were enucleated and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and the whole retina was isolated and incubated in 3% crude trypsin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) containing 200mM sodium fluoride at 37°C for 45–70 minutes. The neuroretinal tissue was gently brushed away under a microscope, and the vasculature was stained with terminal deoxyribonucleotide TUNEL using an In Situ Cell Death Kit (Cat. No. 11684795910, Roche Molecular Biochemicals). As a positive control, retinal vasculature treated with DNAse was also stained with TUNEL. The TUNEL-positive capillary cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope, and the microvasculature was then stained with periodic acid Schiff-hematoxylin to count acellular capillaries by light microscopy [22, 26].

Vascular angiography:

One week before termination of the experiment, vascular angiography was performed using a Micron IV retinal imaging microscope (Phoenix Research Laboratories, Pleasanton, CA), employing the methods previously described by us [22]. Briefly, after anesthetizing the mice with Ketamine (67mg/kg)- Xylazine (10mg/kg), followed by dilation of their pupil with 0.1% tropicamide ophthalmic solution, the fundus was photographed using fundus camera for small animals. AK-FLUOR (0.5% solution, 0.01ml/g BW) was then injected intraperitoneally, and the photographs were taken for 15 minutes after fluorescein administration using a barrier filter for fluorescein angiography [22, 27].

Optical coherence tomography:

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed in mice using Micron IV retinal imaging system. Dilation and lubricant solutions were applied on the cornea of anesthetized mice, and their eyes were positioned in front of the OCT camera. Along the horizontal axis through the optic disc, an average b-scan from 50 individual scans along the retinal cross-section was obtained from each eye. Thickness of the ganglion cell layer (GCL) + inner plexiform layer (IPL), inner nuclear layer (INL) and of the total retinal layers was measured at 200 to 400μm distance on either side of the optic disc in the average b-scan using the caliper tool in the InSight software.

Changes in the retinal morphology were confirmed in 8 micron retinal cryosections, stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, and the images were analyzed at three random places using ImageJ software [22].

Electroretinogram (ERG):

Mice, dark adapted for 12 hours, were anesthetized with Ketamine-Xylazine mixture, and their pupil was dilated with tropicamide ophthalmic solution. A lubricant solution (2.5% hypromellose) was applied, and a silver embedded thread electrode was placed over the cornea, which was held in place using contact lens. ERG responses were recorded in a series of Ganzfeld flashes with intensities ranging from 100–25,000 mcd.s/m^2 using Ocuscience HMsERG Lab system. The amplitudes of a-wave and b-wave were quantified using ERGview software [22].

Statistical analysis:

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparison between groups was made using 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s t-test; p< 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Retinal endothelial cells

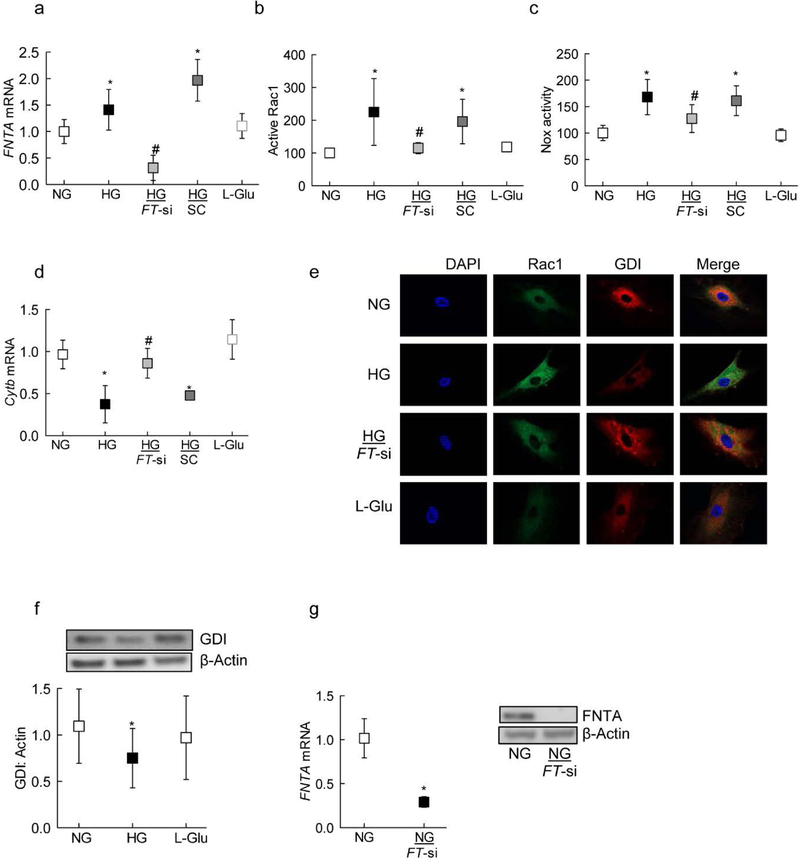

Rac1 is activated in the retina and its capillary cells in hyperglycemic milieu [4, 16], and prenylation of Rac1 is implicated in its activation and assembly of Nox2 holoenzyme [13–15], the levels of the α-subunit of prenyltransferase were quantified in the cells; compared to HRECs in NG, HRECs in HG had 50% increase in FNTA mRNA (Figure 1a). To investigate the effect of prenylation on glucose-induced activation of Rac1, HRECs transfected with FNTA-siRNA were employed; inhibition of FNTA by its siRNA attenuated glucose-induced increase in gene transcripts of FNTA and ameliorated activation of both Rac1 and Nox2. The values obtained from FNTA-siRNA transfected cells and non-transfected cells in HG, were significantly different from each other (Figures 1a–c). In the same transfected cells, FNTA-siRNA also ameliorated glucose-induced mtDNA damage, as depicted by amelioration of decrease in Cytb gene transcripts in FNTA-siRNA cells (Figure 1d). Incubation of cells in 20mols/L L-glucose, instead of 20mols/LM D-glucose, had no effect on the activities of Rac1 and Nox2, and the gene transcripts of FNTA and Cytb. Glucose-induced decreased interactions between Rac1 and GDI were ameliorated in FNTA-siRNA transfected cells. Since prenylation of Rac1 regulates its association with GDI, the effect of high glucose on association of Rac1 with GDI was determined; as shown in figure 1e&f, GDI expression was significantly decreased in cells incubated in high glucose, compared to cells in normal glucose. In the same cell preparations, co-localization of Rac1 with GDI was also decreased, and glucose-induced decrease in interactions between Rac1 and GDI were ameliorated in FNTA-siRNA transfected cells (Figure 1e). Figure 1g is included to show >70% transfection efficiency of FNTA-siRNA, as determined by its mRNA and protein expression.

Figure 1:

Prenylation and Rac1-Nox2 activation. HRECs, transfected with FNTA siRNA (FT-si), or untransfected cells, incubated in normal or high glucose for four days, were analyzed for (a) FNTA mRNA by qPCR, (b) Rac1 activation by G-LISA (c) Nox2 activity by Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay, and (d) mitochondrial damage by quantifying mRNA of Cytochrome b (Cytb). (e) Co-localization of Rac1-GDI was determined by immunofluorescence using Alexa-Flour 488 (green) conjugated and Texas Red (red) conjugated secondary antibodies for Rac1 and GDI respectively. (f) Protein expression of GDI was determined by western blot technique; the blot is a representative of 5–6 samples in each group. (g) FNTA mRNA and protein was quantified for its transfection efficiency in HRECs. Values obtained from untransfected cells in normal glucose are considered as 1 (mRNA) or 100% (activity), and are represented as mean ± SD from three different cell preparations, and each measurement was performed in duplicate. NG and HG=normal and high glucose respectively; L-Glu=L-Glucose 20mols/L; NG or HG+FT-si=cells transfected with FNTA-siRNA and incubated in normal or high glucose for 96 hours. SC= cells with scrambled RNA.

*p<0.05 compared to NG and #p<0.05 compared to HG.

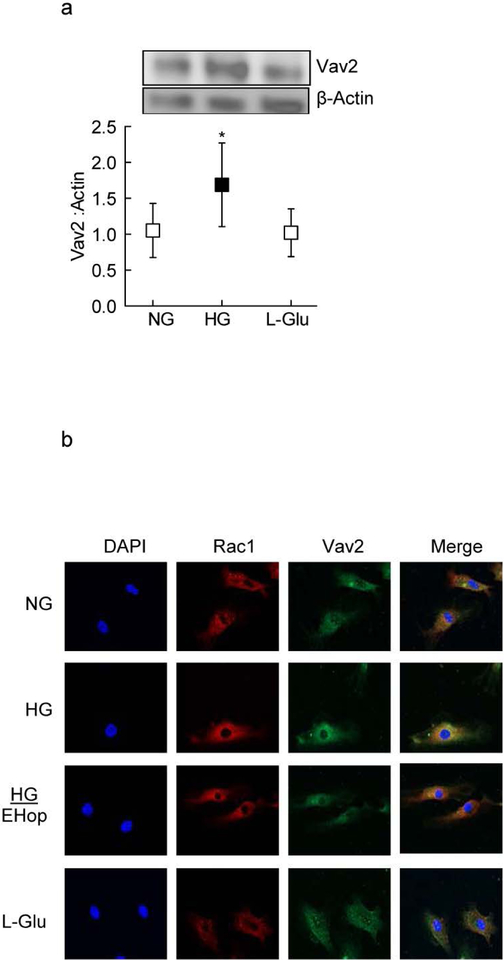

GEFs have an important role in Rac1 activation by regulating switch between the GTP and GDP bound Rac1 [28]. As shown in figure 2a glucose significantly increased the expression of Vav2 in HRECs. In the same cell preparations, Rac1 association with Vav2 was also increased in high glucose conditions (Figure 2b). The role of Vav2 in Rac1 activation was further confirmed by utilizing a pharmacological inhibitor of Vav2, EHop; addition of EHop ameliorated glucose-induced increased association of Rac1 with Vav2 (Figure 2b)

Figure 2:

Effect of high glucose on GDI-Vav2. (a) GDI protein expression was measured by western blot technique; The western blot image is representative of three experiments, and confocal image of is of 3–4 slides/experiment. (b) Co-localization of Rac1 with Vav2 was evaluated by confocal microscopy using Texas red (red) conjugated secondary antibody for Rac1 and Alexa-Flour 488 (green) conjugated secondary antibody for Vav2. Each experiment was done in 3 cell preparations. NG and HG=normal and high glucose respectively; L-Glu=20mM L-Glucose

*p<0.05 compared to NG and #p<0.05 compared to HG.

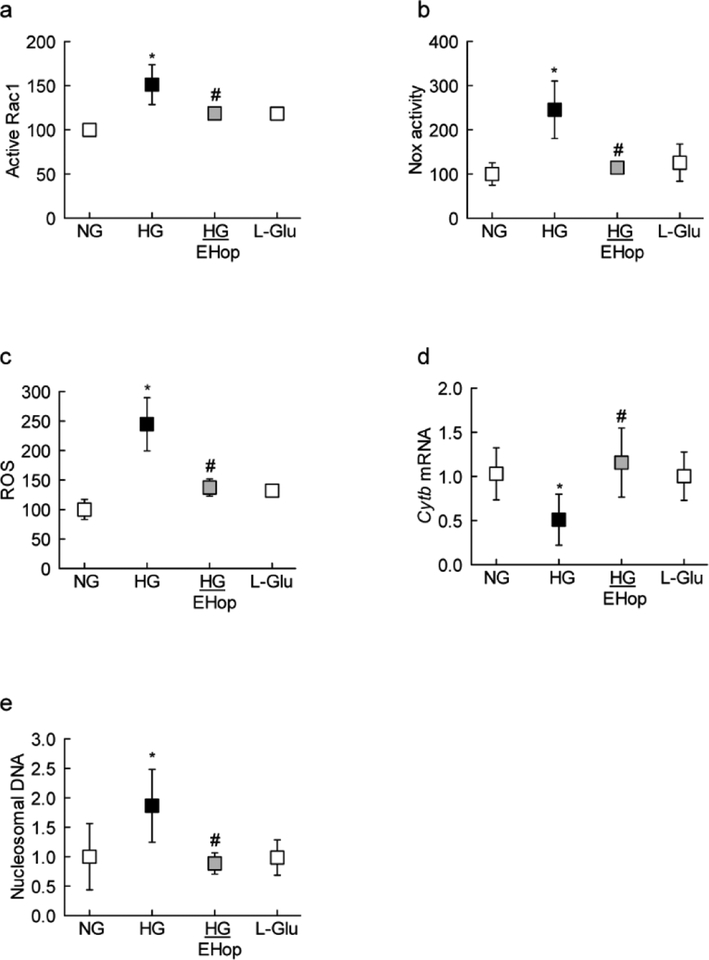

Consistent with Rac1-Vav2 association, EHop also attenuated increase in Rac1-Nox2-ROS signaling (Figures 3a–c). Since activation of Rac1-Nox2-ROS signaling in hyperglycemic milieu damages the mitochondria, accelerating capillary cell death [4, 9], the effect of EHop on the transcription of mtDNA-encoded Cytb, and cell death was determined. As shown in figures 3d&e, EHop prevented decrease in the transcription of Cytb gene, and attenuated increase in cell death of cells exposed to high glucose conditions.

Figure 3:

Vav2 inhibition and glucose-induced Nox2 signaling. HRECs were analyzed for (a) Rac1 activation by G-LISA, (c) Nox2 activity by chemiluminescence assay, (c) ROS levels using DCFH-DA, (d) Cytb gene transcripts by q-PCR, and (e) cell death by Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS kit. Values obtained from cells in normal glucose are considered as 100% (for activity and cell death) and 1 (for mRNA). Results are represented as mean ± SD from 3–4 different cell preparations, with each measurement done in duplicate. NG and HG=normal and high glucose respectively; L-Glu=20mM LGlucose.

*p<0.05 compared to NG and #p<0.05 compared to HG.

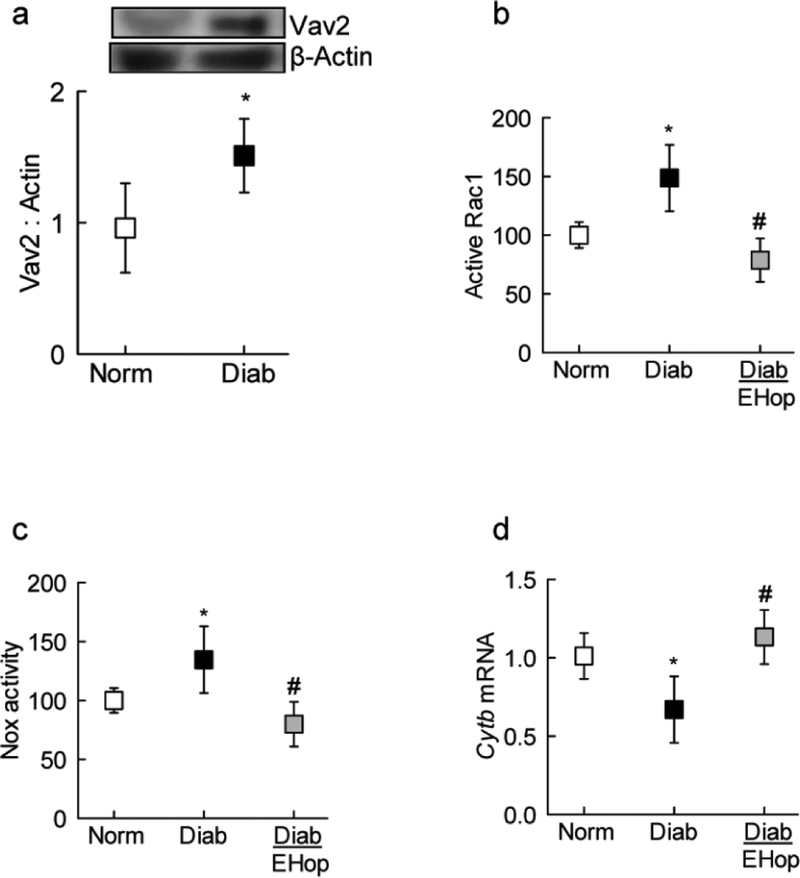

Animal model

Consistent with our in vitro results, compared to age-matched normal mice, Vav2 expression was increased by 50% in retinal microvessels from diabetic mice (Figure 4a&b). Administration of EHop, soon after induction of diabetes, prevented activation of both Rac1 and Nox2 (Figure 4b&c). In the same diabetic mice, mitochondrial damage was also prevented, as observed by amelioration of decrease in mtDNA-encoded Cytb expression in EHop-treated diabetic mice (Figure 4d). The values obtained from EHop-treated diabetic mice were significantly different from diabetic mice without any treatment, but were not different from those obtained from age-matched normal control mice.

Figure 4:

Effect of Vav2 inhibition on Rac1-Nox2 activation in diabetic mice: Retinal microvessels were prepared by osmotic shock method and (a) Vav2 expression was quantified by western blot technique. Activation of (b) Rac1 and (c) Nox2 were quantified by GLISA and Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay respectively.(d) Cyt b mRNA was quantified by q-PCR. Values are represented as mean±SD from 6–7 mice in each group, and each measurement was made in duplicate. Norm and Diab= normal and diabetic mice respectively; Diab+EHop= diabetic mice receiving EHop.

*p<0.05 compared to normal and # p<0.05 compared to diabetes.

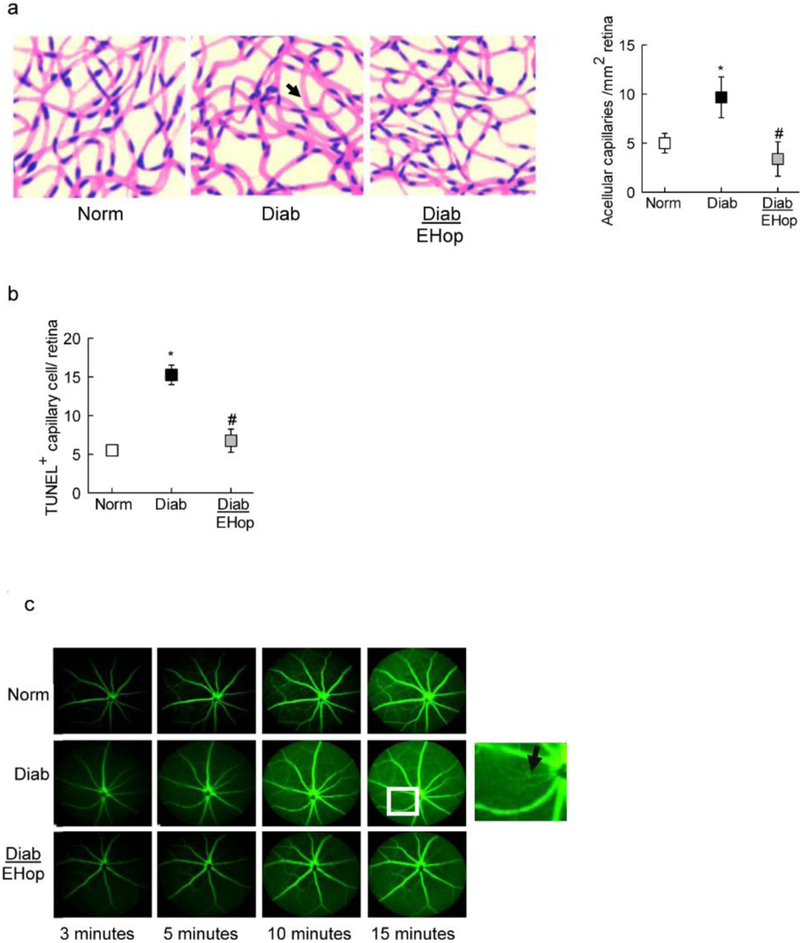

The effect of inhibition of Vav2 on the development of diabetic retinopathy was confirmed by evaluating retinal histopathology by counting the retinal capillaries that have lost endothelial cells [29–31]; EHop administration protected diabetic mice from increase in acellular capillaries and also prevented increase in TUNEL positive capillary cells. The number of acellular capillaries and TUNEL positive capillary cells were over 2 fold higher in diabetic mice without any treatment, compared to diabetic mice receiving EHop, or age-matched normal control mice (Figures 5a & b).

Figure 5:

Inhibition of Vav2 and diabetes-induced retinal capillary cell damage: Trypsin-digested retinal microvessels were used to count (a) acellular capillaries; the arrow head indicates an acellular capillary, and (b) TUNEL+ cells in the entire retinal vasculature. Histograms represent the values from 5–7 mice in each group, and the values are represented as mean ± SD; *p<0.05 and #p<0.05 compared with normal and diabetes respectively. (c) Vascular leakage was quantified by fluorescein angiography using a Micron IV retinal imaging microscope; representative angiograms from mice in each group at 3, 5, 10 and 15 minutes are presented, and the arrow in the inset indicates vascular leakage. Norm and Diab= normal and diabetic mice respectively; Diab+EHop= diabetic mice receiving EHop.

One of the hallmarks of diabetic retinopathy is the leakage of their retinal vasculature [1]; the effect of EHop on vascular integrity was determined by evaluating fluorescence dynamics. As shown in figure 5c, 10 minutes after administration of fluorescein, compared to normal control mice, retinal vasculature of diabetic mice showed leakage and significantly increased fluorescein retention. These vascular abnormalities, however, were not seen in diabetic mice receiving EHop.

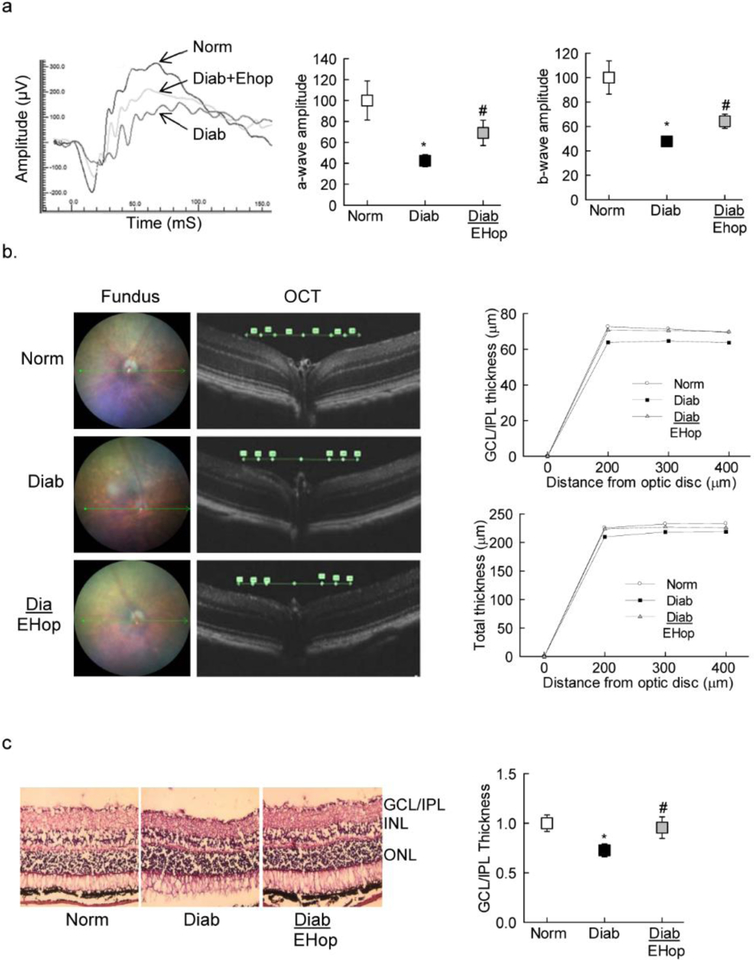

Since diabetes also damages neurovascular cells [32], amelioration in electrical responses by EHop was also determined. EHop treatment prevented abnormalities in retinal function; compared to age-matched normal mice, in EHop treated diabetic mice, although the amplitudes of both a- and b- waves were still lower at 3000 mcd.s/m^2, the values were significantly higher compared to diabetic mice without any treatment (Figure 6a). Similar changes in the amplitudes were seen at 1000 and 10,000 mcd.s/m^2.

Figure 6:

Vav2 inhibition and amelioration of retinal neuronal functional and structural defects in diabetic mice: (a) ERG was performed in dark adapted mice using a series of Ganzfeld flashes with intensities ranging from 100–25,000 mcd.s/m^2. A representative ERG response at 1000 mcd.s/m^2 from one mouse in each group, and amplitudes of a- and b-waves are represented as % normal, the values obtained from diabetic mice were considered as 100%. (b) OCT was performed using an OCT module of the Micron IV retinal imaging system. (c) Retinal cryosections (8 micron) were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, and the images were analyzed using ImageJ software. Each image is representative of 5 or more mice in each group. Each histogram has values from 5–7 mice/group, with values represented as mean ± SD; *p<0.05 and #p<0.05 compared with normal and diabetes respectively. Norm and Diab= normal and diabetic mice respectively; Diab+EHop= diabetic mice receiving EHop.

Loss of nonvascular cells results in the thinning of the retinal layers [33]; our OCT results show that compared to normal mice, diabetic mice had decrease in the thickness of GCL+IPL in diabetic mice (72.63±3.58 μm vs 63.83±4.62; p<0.05). In accordance, thickness of INL (23.88±2.17 μm vs 21.00±2.45 μm) and total retinal layers (225.63±5.32 μm vs 209.67±9.27) were also significantly decreased (p<0.05). However, treatment of diabetic mice with EHop prevented thinning of the retinal layers, and the values obtained at 300 μm away from the optic disc for GCL+IPL, INL and total retinal layers (70.75±5.80 μm, 24.14±2.12 μm and 223.63±9.07 μm respectively) were not different from those observed in normal mice (p>0.05; Figure 6b).

Amelioration of diabetes-induced decrease in retinal layer thickness by EHop was also confirmed in retinal cryosections. As shown in figure 6c, hematoxylin-eosin staining of the cryosections showed decreased GCL/IPL thickness in diabetic mice compared to their age-matched normal control mice, and EHop-treated mice presented similar retinal layer thickness as observed in age-matched normal control mice.

Retinal microvasculature from human donors

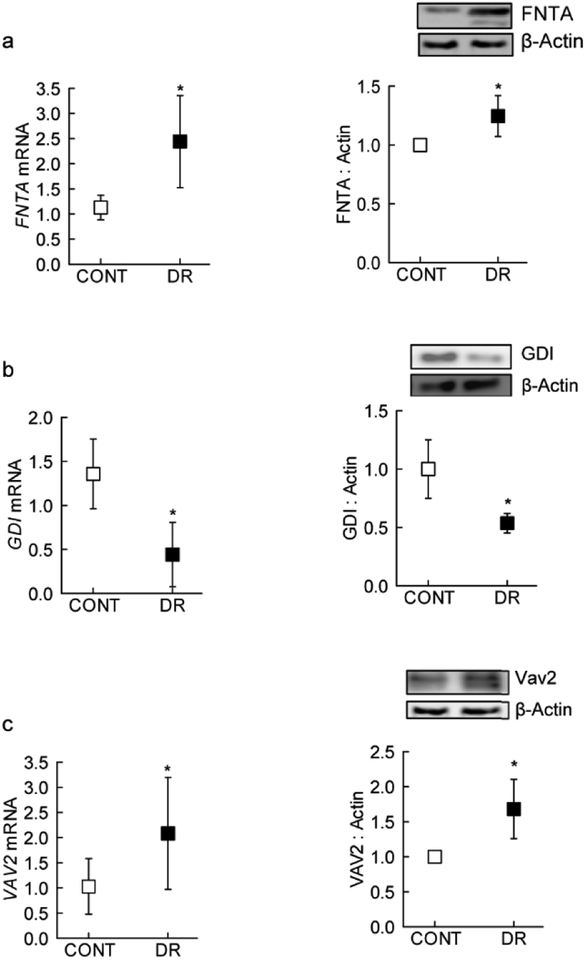

As seen in the experimental models (HRECs and mice), FNTA expression (gene and protein) was increased in the retinal microvasculature from human donors with documented diabetic retinopathy, compared to their age-matched non diabetic donors (Figure 7a). This increase in FNTA was accompanied by a significant increase in Vav2 and decrease in GDI in the retinal microvasculature from the same diabetic donors (Figures 7b&c).

Figure 7:

Modulators of Rac1 activation in the retinal microvasculature from human donors with established diabetic retinopathy. Gene transcripts and protein expression of (a) FNTA, (b) GDI and (c) Vav2 were quantified by q-PCR and western blot techniques. Each measurement was made in duplicate in 6 or more donors in both diabetic retinopathy (DR) and their age-matched non diabetic (CONT) groups. Values are represented as mean ± SD;

*p<0.05 compared with CONT.

DISCUSSION

Diabetes is associated with many metabolic abnormalities in the retina, and oxidative stress is increased in the retina and in its vasculature [34–37]. While increase in cytosolic ROS is an early event in the development of diabetic retinopathy, as the duration of diabetes progresses, mitochondria are damaged and mitochondrial ROS levels are also increased, initiating the apoptotic machinery [25]. Our recent work has identified Nox2 activation as one of the principal sources for increased cytosolic ROS in the development of diabetic retinopathy [9, 16, 38]. We have shown that sustained activation of Rac1, one of the members of Nox2 holoenzyme, represents a critical signaling step in Nox2 activation in diabetes, and epigenetic modifications of Rac1 promoter regulate its transcriptional activation [8, 9]. Covalent modifications are critical in regulating functional activation of Rac1 by modulating its binding with the GEFs and GDIs [10–12]; our results from in vitro and in vivo models demonstrate that inhibition of prenylation prevents activation of Rac1-Nox2 and mitochondrial damage. Furthermore, inhibition of Vav2 attenuates Rac1-Nox2-ROS signaling, and ameliorates the development of retinopathy in diabetic mice and prevents associated functional and structural abnormalities. Retinal microvasculature from human donors with diabetic retinopathy also yielded results consistent with those obtained from experimental models of diabetic retinopathy with decreased GDI levels and increased FNTA and Vav2 levels, further supporting a role for prenylation-dependent, Vav2-mediated functional activation of Rac1 in diabetic retinopathy.

Rac1 is a Rho GTPase, and its interactions with p47-phox are critical in promoting activation of Nox2. Rac1, like other G proteins, cycles between GDP-bound (inactive) and GTP-bound (active) forms [10]. Several mechanisms have been proposed for regulation of Rac1 in pathological states including overexpression of GEFs, loss of negative regulators (e.g., GDIs or GAPs), and post-translational modifications [10]. Rac1 has also been shown to undergo a variety of post-translational modifications, including prenylation (geranylgeranylation), palmitoylation, phosphorylation and sumoylation [12–15], and these modifications precisely regulate Rac1 function, including its activation, subcellular distribution and interaction with effector proteins. Prenylation of Rac1 is considered critical for its translocation to the membrane and activation of its effector proteins, including Nox2 [39]. Our results show that siRNA-mediated knockdown of the α-subunit of prenyltransferase significantly attenuates glucose-induced Rac1-Nox2 activation in retinal endothelial cells, suggesting the role of increased post-translational prenylation of Rac1 in Nox2 activation-mitochondrial damage. Role of prenylation in Rac1 activation in hyperglycemic milieu is further supported by increased FNTA expression in experimental models and also in retinal microvessels from human donors with diabetic retinopathy. In further support of our current obsrervations, a temporal relationship between the onset of atherogenesis and the expression of the key enzymes of mevalonic acid pathway, including HMG CoA reductase and protein prenyltransferases, is reported in vascular smooth muscle cells from streptozotocin-induced diabetic BALB/c mouse model [40], suggesting that increased prenylation of Rac1 in hyperglycemia, in part, may be due to increased expression of the prenyltransferase.

Guanine nucleotide-dissociation inhibitors serve as chaperones to transport Rac1 to the relevant subcellular location, and maintain the inactive form of Rac1 by preventing the dissociation of GDP [12, 41]. These interactions between Rac1 and GDI are also facilitated by post-translational modifications, and prenylation has been shown to be a requisite for interactions between G proteins and their GDIs and GEFs [39]. Here, we show that diabetes decreases GDI expression and its association with Rac1. Furthermore, inhibition of FNTA ameliorates Rac1-GDI association, and prevents Rac1-Nox2 activation. Together, these data raise an interesting possibility for additional regulatory roles of protein prenylation in ameliorating the degradation of GDI, possibly by ubiquitination or proteosomal degradation.

While GDIs maintain Rac1-GDP interactions, specific GEFs convert inactive form of Rac1 to its active form [10, 42]. Our previous study has shown that Tiam1 and Sos1 have significant role in Rac1-Nox2 activation in diabetes, and NSC23766, an known inhibitor of Tiam1-Rac1, attenuates glucose-induced Rac1-Nox2-ROS-apoptosis in retinal endothelial cells [4]. A given G-protein can be modulated by multiple GEFs, and a recent study has shown dual roles for Tiam1 and Vav2 in the regulation of Rac1-Nox2-ROS signaling pathway, suggesting that, while Vav2 is essential for the attainment of the active conformation of Rac1 (Rac1-GTP), Tiam1 functions as an adaptor in a polarity complex that directs localized activation of Rac1 [11, 43]. Here, our data from in vitro and in vivo models show that Vav2 is also involved in the activation of Rac1-Nox2; the expression of Vav2 is increased in the retinal microvasculature in hyperglycemic conditions, and inhibition of Vav2 by its pharmacological inhibitor EHop, in addition to regulating Rac1-Nox2, prevents mitochondrial damage.

Mitochondrial damage releases cytochrome C in the cytosol activating the apoptotic machinery [44], and animal models have clearly documented that apoptosis of capillary cells precedes the development of histopathology characteristic of diabetic retinopathy [26, 30]. Our results clearly show that administration of EHop, soon after induction of diabetes in mice, also prevents vascular changes associated with diabetic retinopathy and the number of acellular capillaries in diabetic mice receiving EHop is similar to that in normal control mice. Consistent with this, diabetic mice receiving EHop have significantly lower number of TUNEL positive capillary cells. Since vascular permeability is also considered as an early clinical sign of diabetic retinopathy [1], diabetic mice receiving EHop show amelioration of increased retinal vascular permeability, further confirming the beneficial effects of Vav2-Rac1 inhibition on the development of diabetic retinopathy.

Nonvascular cells are also damaged in diabetic retinopathy, and defects in ERG and neuronal cell apoptosis/thinning of the retinal layers are observed before vascular pathology [32, 45]. Our results show that EHop administration also protects structural and functional abnormalities in the retinal nonvascular cells; the ERG signals are better in EHop treated diabetic mice compared to untreated diabetic mice, and the thinning of their retinal layers is prevented. How regulation of Vav2-Rac1 helps in maintaining retinal nonvascular cells and their functional alterations in diabetes needs further investigation.

Based on the data accrued from experimental models (in vitro and in vivo), and the key parameters confirmed in retinal microvessels from human donors with diabetic retinopathy, we propose that in diabetes, Rac1 prenylation, and its interactions with GDI and Vav2 contribute to the activation of Rac1-Nox2-ROS. The mitochondria are damaged, ultimately leading to the development of retinopathy. Fortunately, synthetic isoprenoids targeting prenylation are being tested for breast cancer cell invasion [46], and a new class of thienopyrimidine-based bisphosphonate inhibitors in multiple myeloma cells [47]. Regulation of Vav2 prevents diabetes-induced retinal structural and functional damage, and protects the retinal vasculature from being leaky and undergoing accelerated capillary cell loss, suggesting that Vav2 could be one of the important GEFs involved in sustained activation of Rac1-Nox2, and the development of diabetic retinopathy.

Funding.

This study was supported in parts by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RAK: EY014370 and EY017313; RAK, AK: EY022230), Thomas Foundation (RAK), Department of Veterans Affairs (1BX000469, AK), and an unrestricted grant to the Ophthalmology Department from Research to Prevent Blindness. AK is the recipient of a Senior Research Career Scientist Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (13S-RCS-006).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest. GM, AJD, AK and RAK do not have any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Frank RN, Diabetic Retinopathy, New Eng J Med, 350 (2004) 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kowluru RA, Kowluru A, Mishra M, Kumar B, Oxidative stress and epigenetic modifications in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy, Prog Retin Eye Res, 48 (2015) 40–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Guzman DC, Olguin HJ, Garcia EH, Peraza AV, de la Cruz DZ, Soto MP, Mechanisms involved in the development of diabetic retinopathy induced by oxidative stress, Redox Report, 22 (2017) 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kowluru RA, Kowluru A, Veluthakal R, Mohammad G, Syed I, Santos JM, Mishra M, TIAM1-RAC1 signalling axis-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase-2 initiates mitochondrial damage in the development of diabetic retinopathy, Diabetologia, 57 (2014) 1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kowluru A, Kowluru RA, Phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase [Nox2] in cellular dysfunction in models of glucolipotoxicity and diabetes, Biochem Pharmacol, 88 (2014) 275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].El-Benna J, Dang PM, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Marie JC, Braut-Boucher F, p47phox, the phagocyte NADPH oxidase/NOX2 organizer: structure, phosphorylation and implication in diseases, Exp Mol Med, 41 (2009) 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pick E, Role of the Rho GTPase Rac in the activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: outsourcing a key task, Small GTPases, 5 (2014) e27952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Duraisamy AJ, Mishra M, Kowluru A, Kowluru RA, Epigenetics and regulation of oxidative stress in diabetic retinopathy, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 59 (2018) 4831–4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kowluru RA, Mishra M, Kumar B, Diabetic retinopathy and transcriptional regulation of a small molecular weight G-Protein, Rac1, Exp Eye Res, 147 (2016) 72–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Haga RB, Ridley AJ, Rho GTPases: Regulation and roles in cancer cell biology, Small GTPases, 7 (2016) 207–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bai Y, Xiang X, Liang C, Shi L, Regulating Rac in the nervous system: molecular function and disease implication of Rac GEFs and GAPs, BioMed Res Int, 2015 (2015) 632450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].DerMardirossian C, Bokoch GM, GDIs: central regulatory molecules in Rho GTPase activation, Trends Cell Biol, 15 (2005) 356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Syed I, Kyathanahalli CN, Kowluru A, Phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase generates ROS in INS 832/13 cells and rat islets: role of protein prenylation, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, (2011) R756–R762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].van Rijssel J, van Buul JD, The many faces of the guanine-nucleotide exchange factor trio, Cell Adh Mig, 6 (2012) 482–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Abdrabou A, Wang Z, Post-Translational Modification and Subcellular Distribution of Rac1: An Update, Cells, 7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mishra M, Duraisamy AJ, Bhattacharjee S, Kowluru RA, Adaptor protein p66Shc: A link between cytosolic and mitochondrial dysfunction in the development of diabetic retinopathy, Antiox Redox Signal, 30 (2019) 1621–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schlegel N, Waschke J, cAMP with other signaling cues converges on Rac1 to stabilize the endothelial barrier- a signaling pathway compromised in inflammation, Cell Tiss Res, 355 (2014) 587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kowluru A, Tiam1/Vav2-Rac1 axis: A tug-of-war between islet function and dysfunction, Biochem Pharmacol, 132 (2017) 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Veluthakal R, Tunduguru R, Arora DK, Sidarala V, Syeda K, Vlaar CP, Thurmond DC, Kowluru A, VAV2, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac1, regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells, Diabetologia, 58 (2015) 2573–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mishra M, Kowluru RA, Role of PARP-1 as a novel transcriptional regulator of MMP-9 in diabetic retinopathy, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1863 (2017) 1761–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mishra M, Kowluru RA, DNA methylation-a potential source of mitochondria DNA base mismatch in the development of diabetic retinopathy, Mol Neurobiol, 56 (2019) 88–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mishra M, Duraisamy AJ, Kowluru RA, Sirt1- A guardian of the development of diabetic retinopathy, Diabetes, 67 (2018) 745–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Castillo-Pichardo L, Humphries-Bickley T, De La Parra C, Forestier-Roman I, Martinez-Ferrer M, Hernandez E, Vlaar C, Ferrer-Acosta Y, Washington AV, Cubano LA, Rodriguez-Orengo J, Dharmawardhane S, The Rac Inhibitor EHop-016 Inhibits Mammary Tumor Growth and Metastasis in a Nude Mouse Model, Transl Oncol, 7 (2014) 546–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mishra M, Flaga J, Kowluru RA, Molecular mechanism of transcriptional regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in diabetic retinopathy, J Cell Physiol, 231 (2016) 1709–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kumar B, Kowluru A, Kowluru RA, Lipotoxicity augments glucotoxicity-induced mitochondrial damage in the development of diabetic retinopathy, Invest Ophtahlmol Vis Sci, 56 (2015) 2985–2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kowluru RA, Mohammad G, dos Santos JM, Zhong Q, Abrogation of MMP-9 gene protects against the development of retinopathy in diabetic mice by preventing mitochondrial damage, Diabetes, 60 (2011) 3023–3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu CH, Sun Y, Li J, Gong Y, Tian KT, Evans LP, Morss PC, Fredrick TW, Saba NJ, Chen J, Endothelial microRNA-150 is an intrinsic suppressor of pathologic ocular neovascularization, Proc Natl Acad Sci, 112 (2015) 12163–12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bokoch GM, Bohl BP, Chuang TH, Guanine nucleotide exchange regulates membrane translocation of Rac/Rho GTP-binding proteins, J Biol Chem, 269 (1994) 31674–31679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Engerman RL, Kern TS, Progression of incipient diabetic retinopathy during good glycemic control, Diabetes, 36 (1987) 808–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mizutani M, Kern TS, Lorenzi M, Accelerated death of retinal microvascular cells in human and experimental diabetic retinopathy, J Clin Invest, 97 (1996) 2883–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kern TS, Miller CM, Tang J, Du Y, Ball SL, Berti-Matera L, Comparison of three strains of diabetic rats with respect to the rate at which retinopathy and tactile allodynia develop, Mol Vis, 16 (2010) 1629–1639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kern TS, Barber AJ, Retinal ganglion cells in diabetes, J Physiol, 586 (2008) 4401–4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].van Dijk HW, Verbraak FD, Kok PH, Stehouwer M, Garvin MK, Sonka M, DeVries JH, Schlingemann RO, Abramoff MD, Early neurodegeneration in the retina of type 2 diabetic patients, Invest Ophtahlmol Vis Sci, 53 (2012) 2715–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kowluru RA, Diabetic retinopathy, oxidative stress and antioxidants, Current Topics in Nutraceutical Res, 3 (2005) 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Doly M, Droy-Lefaix MT, Braquet P, Oxidative stress in diabetic retina, Birkhauser Verlag, Place Published, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Madsen-Bouterse SA, Kowluru RA, Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment perspectives, Rev Endocr Metab Disord, 9 (2008) 315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Calderon GD, Juarez OH, Hernandez GE, Punzo SM, De la Cruz ZD, Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: development and treatment, Eye, 31 (2017) 1122–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kowluru RA, Mishra M, Kowluru A, Kumar B, Hyperlipidemia and the development of diabetic retinopathy: Comparison between type 1 and type 2 animal models, Metabolism, 65 (2016) 1570–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Di-Poi N, Faure J, Grizot S, Molnar G, Pick E, Dagher MC, Mechanism of NADPH oxidase activation by the Rac/Rho-GDI complex, Biochemistry, 40 (2001) 10014–10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chen GP, Zhang XQ, Wu T, Li L, Han J, Du CQ, Alteration of mevalonate pathway in proliferated vascular smooth muscle from diabetic mice: possible role in high-glucose-induced atherogenic process, J Diab Res, 2015 (2015) 379287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ugolev Y, Berdichevsky Y, Weinbaum C, Pick E, Dissociation of Rac1(GDP).RhoGDI complexes by the cooperative action of anionic liposomes containing phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor, and GTP, J Biol Chem, 283 (2008) 22257–22271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kowluru A, Kowluru RA, RACking up ceramide-induced islet beta-cell dysfunction, Biochem Pharmacol, 154 (2018) 161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Liu Y, Collins C, Kiosses WB, Murray AM, Joshi M, Shepherd TR, Fuentes EJ, Tzima E, A novel pathway spatiotemporally activates Rac1 and redox signaling in response to fluid shear stress, J Cell Biol, 201 (2013) 863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Phaneuf S, Leeuwenburgh C, Cytochrome c release from mitochondria in the aging heart: a possible mechanism for apoptosis with age, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 282 (2002) R423–R430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Simo R, Stitt AW, Gardner TW, Neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy: does it really matter?, Diabetologia, 61 (2018) 1902–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chen M, Knifley T, Subramanian T, Spielmann HP, O’Connor KL, Use of synthetic isoprenoids to target protein prenylation and Rho GTPases in breast cancer invasion, PloS one, 9 (2014) e89892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lacbay CM, Waller DD, Park J, Gomez Palou M, Vincent F, Huang XF, Ta V, Berghuis AM, Sebag M, Tsantrizos YS, Unraveling the Prenylation-Cancer Paradox in Multiple Myeloma with Novel Geranylgeranyl Pyrophosphate Synthase (GGPPS) Inhibitors, J Med Chem, 61 (2018) 6904–6917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]