Abstract

Background

Among different resistance mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), efflux pumps may have a role in drug-resistance property of MTB. So, the aim of this study was to compare the relative overexpression of two important efflux pump genes, drrA and drrB, among MTB isolates from TB patients.

Methods

A total of 37 clinical isolates of confirmed MTB isolates were analyzed. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) was performed using the conventional proportional method. Real-time semiquantitative PCR profiling of the efflux pump genes of drrA and drrB was performed for clinical isolates. The receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis for differentiation of resistant from susceptible isolates on the basis of efflux pump expression fold changes was also performed.

Results

According to DST, 16 rifampin (RIF) monoresistant, 3 isoniazid (INH) monoresistant, 5 multidrug-resistant (MDR) and 13 pan-susceptible isolates of MTB were evaluated for gene expression. The highest values of drrA and drrB gene expression fold changes were seen in MDR isolates, which were significant in comparison with susceptible isolates and H37Rv reference strain. By using comparative ROC analysis, the obtained cutoff point for drrA and drrB gene overexpression was the folds of >1.6 and >2.3, respectively.

Conclusion

The results of the present study confirm the role of DrrA-DrrB efflux pump in antibiotic resistance in clinical MTB isolates. As the large number of efflux pumps are located in the cell envelope of MTB, we cannot correlate a single efflux pump overexpression to the drug-resistance phenotype, unless all the pumps simultaneously investigated.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, multidrug resistance, efflux pump regulators, Isoniazid, Rifampin

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is the major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 According to the recent WHO report,2 TB is the ninth mortality cause in the world, and it was estimated that 10 million people suffered from TB in 2017; among them, 9% were HIV positive. Nowadays, the major challenge in TB control and treatment is the emergence of different forms of drug-resistant MTB isolates, including multidrug resistance (MDR), defined as TB resistant to at least isoniazid (INH) and rifampin (RIF), and extensively drug resistance (XDR), which is defined as MDR-TB plus resistance to any fluoroquinolone and at least one second-line injectable aminoglycoside antibiotics.3,4 In 2016, about 600,000 RIF-resistant (RR) new cases and 490,000 MDR isolates were recognized.2 Globally, 4.1% of new cases and 19% of previously treated TB patients are estimated to have RR-TB or MDR-TB, and about 6.2% of MDR-TB cases have additional drug resistance of XDR.5 Treatment of MDR and XDR-TB with currently available anti-TB drugs needs a longer time, associated with high costs, and has toxic side effects and treatment outcomes are often poor.6

The mode of action of RIF is binding to the β-subunit of RNA polymerase and inhibiting the elongation of mRNA molecule. INH metabolically is active against live bacteria and inhibits mycolic acid synthesis.7 Apart from known mutations in genes conferring resistance to INH and RIF, efflux pump activity was recently recognized to play a significant role in the development of drug-resistant phenotypes in MTB.8–10 Efflux pumps extrude many substrates including peptides, lipids, ions, drugs and antibiotics, from the intracellular environment into the extracellular space.4 Efflux-mediated drug resistance in M. tuberculosis could be due to one or more efflux pumps working alone or in coordination.11 The overexpression of efflux pumps can significantly decrease the intracellular concentration of many antibiotics and consequently reduce the efficacy of drugs.10

Efflux pumps can be divided into two main classes of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and secondary multidrug transporters. The latter, which include the majority of clinically relevant efflux systems, can be subdivided into four superfamilies based primarily on homology at the levels of primary and secondary structures.12 These superfamilies are the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE), resistance-nodulation-division (RND) and small multidrug resistance (SMR) families. The RND, SMR, MFS superfamily and ABC transporter have been found in MTB.8 In MTB, the genes encoding the predicted ABC transporters occupy about 2.5% of the genome.13

Two transnationally coupled open-reading frames, drrA (Rv 2936) and drrB (Rv2937), encode an ABC-type transporter, with drrA encoding the nucleotide-binding domain and drrB encoding the membrane-integral component. In fact, drrA and drrB are important because of their potency in making antibiotic resistant phenotype against structurally unrelated drugs. Studies have shown that after inhibition of ABC transporters, the resistant phenotype is changed into the sensitive type.14

The aim of this study was to compare the relative overexpression of two important efflux pump genes, drrA and drrB, related to ABC transporter in order to evaluate the role of these genes in drug resistance among MTB isolates from TB patients.

Materials And Methods

Bacterial Strains

The MTB strains selected for this study were isolated from samples of confirmed pulmonary TB patients referred to Regional Tuberculosis Laboratory of Khuzestan province, Iran, during a 2-year period, from February 2015 to February 2017. The preliminary proposal of the work was approved in joint Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Ethics Committee of the Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Iran, and the necessary permission was granted for sample collection. Moreover, as part of the Regional Centers’ policy, referred patients were requested to sign the informed consent in case that their samples are used for research purposes apart from routine clinical investigation.

The strains were identified as MTB based on acid-fast staining, growth on Lowenstein–Jensen (LJ) medium and standard biochemical identification tests.15

DNA Extraction And PCR Amplification

DNA was extracted from MTB isolates grown on LJ medium by using a simple boiling method as described earlier.16 The extracted DNAs were molecularly confirmed as belonging to MTB complex in the next step, by IS6110- based PCR amplification, employing primers which amplify a 123 bp fragment of sequence as described previously.17

Drug Susceptibility Testing (DST)

For investigating the antimicrobial susceptibility of MTB isolates, DST was performed using the standard proportional method according to the clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guideline.18 In brief, 0.2 μg/mL INH and 40 μg/mL RIF (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim am Albuch, Germany) antibiotic concentrations were incorporated into LJ medium followed by inoculation of a pre-adjusted bacterial suspension equal to 0.5 McFarland. MTB standard strain of H37Rv (ATCC 27294) was used as a reference strain. Susceptibility was defined as no or <1% growth on LJ medium containing drugs as compared with the control medium. In total, 24 drug-resistant and 13 randomly selected drug-susceptible MTB isolates were selected for further investigation.

The isolates were divided into two groups as per DST results: the susceptible isolates and the MTB isolates with various resistance phenotypes, including RIF monoresistance, INH mono resistance or isolates resistant to both INH and RIF (MDR phenotype).

Real-Time Semiquantitative PCR (RT-sqPCR)

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from clinical MTB isolates using High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions and treated with DNase Ι (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The concentration and quality of isolated total RNA were evaluated using Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at A260/A280. PCR amplification of the polA gene was done to assess possible DNA contamination, using the total RNA as a template. Only RNA with no visible amplified products was used for experiments.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) Library Synthesis

The cDNA was synthetized using PrimeScript RT reagent Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). Reverse transcription steps were as follows: 37°C for 10 mins, 42°C for 30 mins and 70°C for 5 mins. The synthesized cDNA was maintained at −80°C until use.

RT-sqPCR was performed to evaluate the overexpression of drrA and drrB efflux pump genes according to a previous report.19 polA was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization. The primer sequences for drrA, drrB and polA genes are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Sequence Of Primers Of The Genes Used In This Study

| No. | Gene | Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | Amplicon Size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | drrA | Forward | TAGACATCGCGTGCGGATTGGT | 147 |

| Reverse | GCGTGGTCAACAACGTGGCAAT | |||

| 2 | drrB | Forward | TCGCCAGCAACTTAGGGCAATACA | 233 |

| Reverse | TCCGATGACGTAGCCGCAAACTAG | |||

| 3 | polA | Forward | TCCGATGACGTAGCCGCAAACTAG | 181 |

| Reverse | GTCGTGGTTGGACCTTGGAGGG | |||

The master-mix was prepared according to the kit manufacturer’s instruction (Takara Bio Inc.). RT-sqPCR was done in an ABI Step-One thermocycler (Applied Biosystem, Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany) with the following amplification program: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 mins and 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 20 s and a final extension at 72°C for 5 mins and an additional step at 50°C for 15 s followed by melt analysis (50–99°C). The RT-sqPCR reactions were performed in triplicate samples using total RNA from three independent cultures for each strain. Differential expression was done by comparing the normalized Ct values (2−∆∆Ct) of all the biological replicates between two groups of samples using the Livak equation.20 We also used the relative expression software tool (REST 2009) to confirm the relative expression values.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of gene fold changes among different studied groups on the basis of DST results was done using Mann–Whitney test because of data distribution abnormality after Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. To evaluate the accuracy of drrA or drrB gene folds, receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was used for estimation of the proper cutoff points, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) of fold change as a decision-making tool for clinical application of drrA and drrB genes using RT-sqPCR method. Statistical analysis and calculations were done using MedCalc® software version 15.8.

Results

In this study, 37 clinical isolates which had been characterized as MTB by using standard phenotypic tests and IS6110-PCR amplification were entered the study. According to DST, drug-resistance pattern of the isolates were as follows: 16 RIF monoresistant, 3 INH monoresistant, 5 MDR and 13 pan-susceptible isolates.

In order to investigate the involvement of drrA and drrB efflux pump genes in the drug resistance of MTB clinical isolates, the relative expression profiles (fold changes) of these genes were examined by RT-sqPCR, using H37Rv as the reference strain. The results of DST and expression fold changes of putative efflux pump genes for each isolate are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Results From Phenotypic Drug Susceptibility Testing And Relevant drrA And drrB Gene Expression Fold Changes For MTB Isolates

| Patients No. | Resistance Pattern | drrA Fold Changes | drrB Fold Changes | Patient No. | Resistance Pattern | drrA Fold Changes | drrB Fold Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RIF | 6.7 | 4.8 | 20 | S | 1.3 | 2.3 |

| 2 | MDR | 23.62 | 10.7 | 21 | RIF | 0.2 | 2.9 |

| 3 | MDR | 18.53 | 4.07 | 22 | S | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| 4 | MDR | 23.51 | 4.1 | 23 | S | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| 5 | MDR | 27.93 | 5.23 | 24 | S | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| 6 | MDR | 19.8 | 3.08 | 25 | S | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| 7 | RIF | 23.19 | 4.15 | 26 | S | 0.2 | 1.02 |

| 8 | RIF | 0.98 | 3.34 | 27 | RIF | 0.5 | 3.05 |

| 9 | RIF | 4.8 | 4.24 | 28 | RIF | 0.3 | 15.46 |

| 10 | RIF | 3.06 | 1.9 | 29 | S | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| 11 | RIF | 12.7 | 3.6 | 30 | INH | 4.7 | 2.3 |

| 12 | RIF | 17.86 | 3.5 | 31 | INH | 6.9 | 7.1 |

| 13 | RIF | 27.17 | 2.9 | 32 | S | 0.4 | 0.38 |

| 14 | RIF | 13.38 | 2.1 | 33 | INH | 6.01 | 5.4 |

| 15 | RIF | 5.6 | 0.1 | 34 | S | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 16 | S | 1.1 | 2.1 | 35 | S | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| 17 | RIF | 0.4 | 5.07 | 36 | S | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| 18 | RIF | 0.7 | 2.5 | 37 | S | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| 19 | RIF | 0.3 | 4.01 |

Abbreviations: RIF, rifampin; INH, isoniazid; MDR, multidrug resistant; S, susceptible.

The majority of resistant phenotypes overexpressed both genes more than twofolds, while the pan-susceptible isolates showed less than twofold expression which was not significant compared to H37Rv reference strain. All MDR isolates overexpressed both drrA and drrB genes, which was significant in comparison with susceptible isolates and H37Rv reference strain (P values 0.009 and 0.09, respectively), while 9 out of 16 RIF monoresistant isolates (56.25%) showed overexpression of drrA and 14 (87.5%) of these isolates showed overexpression of drrB gene; both were significant as well (P values for both genes were 0.025). INH monoresistant isolates overexpressed both genes; however, due to the lower number of these isolates, we did not demonstrate significant differences compared to susceptible isolates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation Of Genes Expression Fold Changes Of drrA And drrB In Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Isolates With Various Drug-Resistance Patterns

| Resistance Phenotype | drrA Expression No.(%) | P value | drrB Expression No.(%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIF monoresistant | 9 (56.25) | 0.025 | 14(87.5) | 0.025 |

| INH monoresistant | 3 (100) | 0.1 | 3 (100) | 0.1 |

| MDR | 5 (100) | 0.009 | 5 (100) | 0.09 |

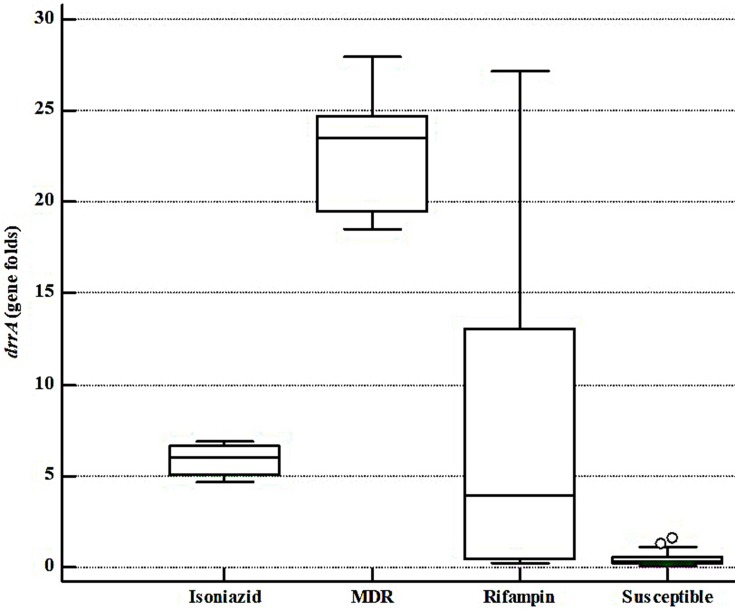

The gene expression fold changes were significantly different among MTB isolates categorized according to their DST results (P= 0.000173 for drrA gene and P= 0.000115 for drrB gene). Figures 1 and 2 represent the comparative boxplot of drrA and drrB gene fold changes among MTB isolates in different antibiotic resistance patterns. Both MDR and INH monoresistant isolates had significantly high expression fold changes of drrA in comparison with pan-susceptible isolates (Figure 1), and as the figure shows, the highest and the lowest expression values belonged to the MDR and pan-susceptible isolates, respectively, in comparison with standard MTB strain of H37Rv.

Figure 1.

The drrA gene expression fold comparison of different groups of MTB isolates as per DST results.

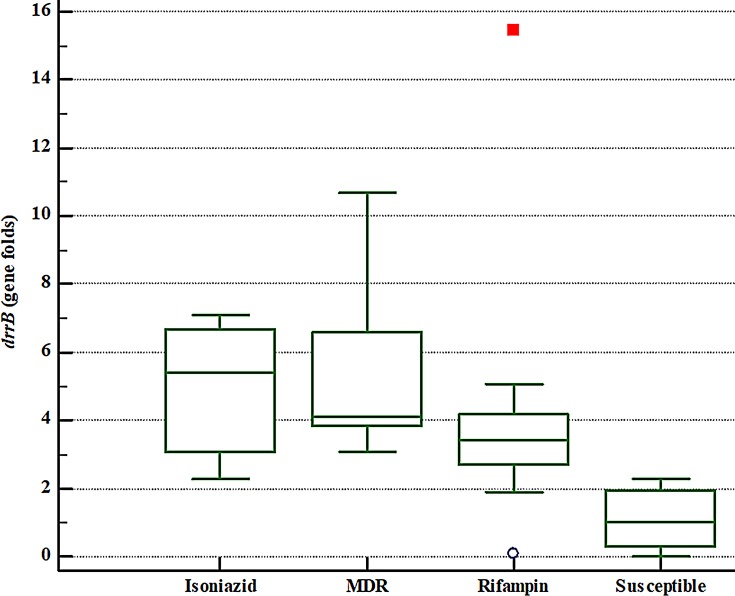

Figure 2.

The drrB gene expression fold comparison of different groups of MTB isolates as per DST results. Note that a rifampin-resistant isolate showed very high levels of drrB gene expression which is shown by a dot on the FIGURE as an outlier.

For drrB gene, though the expression fold changes were higher in RIF monoresistant isolates, all MDR and INH monoresistant isolates showed high expression fold changes for drrB similar to drrA gene (Figure 2). The highest and the lowest expression values for drrB gene belonged to the MDR and pan-susceptible isolates, respectively.

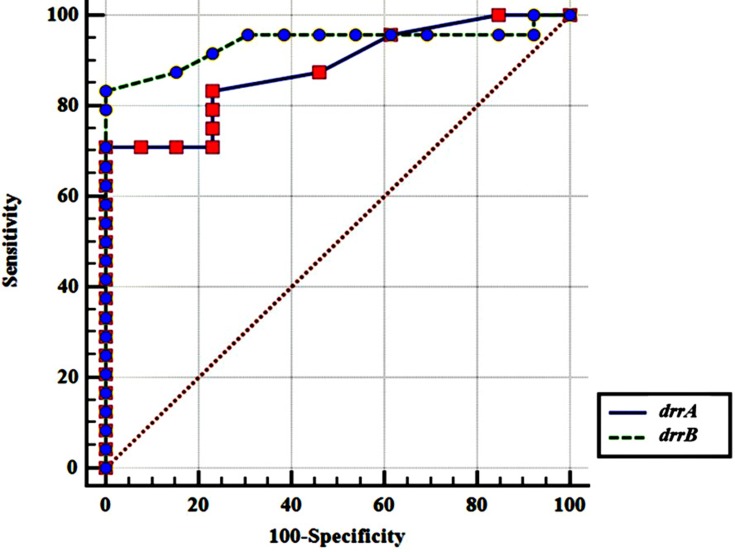

In this work, we have also evaluated drrA and drrB gene expression fold changes for clinical purposes, using ROC analysis. This analysis was used to estimate the sensitivity and specificity, based on calculated cutoff points. According to DST results, from 37 MTB tested isolates, 13 (35.14%) were susceptible and 24 (64.86%) were resistant to antibiotics. Comparative ROC analysis represented no significant difference between two genes in view of their application as diagnostic tools for differentiation of susceptible MTB isolates from resistant ones (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparative ROC curve for drrA and drrB genes. Statistical analysis showed that there is no meaningful difference between drrA and drrB genes considering diagnostic accuracy (P value= 0.4045).

The obtained cutoff point for drrA gene overexpression was the folds of >1.6 with sensitivity and specificity equal to 70.83% and 100%, respectively. The best cutoff point for drrB gene overexpression was the folds of >2.3 with sensitivity and specificity values equal to 83.33% and 100%, respectively.

Discussion

There are different mechanisms by which the MTB strains show resistance against antibiotics. The intrinsic resistance of MTB to most antibiotics is generally attributed to the low permeability of the mycobacterial cell wall because of its specific lipid‑rich composition and structure.21 Since the first evidence of active efflux being involved in antibiotic resistance, efflux mechanisms have been recognized to be major players in bacterial drug resistance.13,22 The antibiotics need to be reached to an effective intracellular concentration to do their job. However, bacterial efflux pumps extrude them before they could accumulate to their antibacterial active concentration. 23

In the present study, we evaluated the expression fold changes of drrA and drrB genes encoding putative DrrA-DrrB drug efflux pump belong to ABC transporter, in MTB isolates. The results demonstrated that RIF and INH monoresistant and MDR isolates showed meaningfully increased expression fold changes compared to susceptible isolates and H37Rv-susceptible reference strain. The efflux pump genes of drrA and drrB were shown to be significantly overexpressed in most of the antibiotic resistant MTB isolates demonstrating the contribution of these genes to the resistance phenotype of the isolates studied. Our findings suggest that the drrA and drrB genes may have a key role in MDR phenotype of MTB in the same efflux pump, because all MDR isolates showed high expression fold changes demonstrated by RT-sqPCR.

In concordant to our study, Jiang et al have reported that the increased gene expression folds of their tested efflux pumps are associated with the MDR property in MTB strains.24 They have tested putative efflux pump genes including Rv1258c, Rv1410c and Rv1819c and showed that the first two genes were overexpressed upon RIF or INH exposure, whereas the last gene was overexpressed only upon INH exposure. However, their findings were limited to only one clinical isolate, whereas we have tested 37 clinical MTB isolates.

There are other studies which also have confirmed the association of different efflux pumps with antibiotic resistance phenotypes of MTB strains.25 The expression of efflux pumps including Rv2459, Rv3728, and Rv3065 is reported to be increased in response to MTB exposure to INH and ethambutol.26 Additionally, in the study of Wang et al, on 36 isolates of MTB, they reported that the overexpression of both Rv1217c and Rv1218c genes was the cause of decreased RIF sensitivity in MIC test, whereas INH-resistant isolates showed only Rv1218c overexpression.27 The studies are not limited to MTB, as other mycobacteria such as M. smegmatis showed to become MDR when overexpression of Rv0194 occurred.28 In the current study, both drrA and drrB genes showed expression fold changes mainly for whole MDR and INH monoresistant isolates showing the role of ABC transporter efflux pump in resistance of MTB to antibiotics. The findings were in agreement to another study which stated that the certain types of efflux pumps may have a central role for extruding the antibiotics from MTB strains.27 However, based on our findings, it seems that drrB gene could be a preferred gene for assessing the clinical isolates for RIF drug resistance as more RIF monoresistant isolates overexpressed this gene.

Although several classes of efflux pumps in MTB isolates are investigated previously, there are a few reports about the expression fold changes of drrA and drrB genes in clinical isolates of MTB. In one similar study, Li et al have shown that drrA, drrB, mmr, efpA, jefA, Rv0849, Rv1634 and Rv1250 genes had high levels of expression folds in 9 MDR isolates of MTB.19 They have made stress conditions on isolates using INH and RIF antibiotics followed by assessing the folds of efflux pumps, and they demonstrated that drrA gene folds were overexpressed followed INH stress, and they have suggested drrA overexpression as one of the involving factors to INH resistance in MTB accordingly. However, such finding was not evident for RIF, and none of their isolates showed fold change of drrA expression levels in response to RIF stress. Their study was against present study, and Pang et al report that drrA may induce a low-level resistance to RIF in MTB isolates.29

Our findings revealed that MDR isolates showed significantly high overexpression folds in comparison with standard H37Rv strain. The highest expression fold changes in our work were seen for drrA gene, even up to 27.93 folds compared to H37Rv. Furthermore, the highest value for drrB gene was 15.46 folds in comparison with H37Rv strain. Calgin et al have compared 10 MDR and 10 susceptible isolates of MTB and reported that drrA and drrB gene overexpression was 1–2 folds higher than the H37Rv standard strain.30 On the other hand, Machado et al have used a cutoff value of 4 or higher folds of gene expression, compared with drug-unexposed strain and reported that the efflux pump overexpression levels would be increased in MTB, after encountering suboptimal concentrations of antituberculosis drugs.31

As putative efflux pump gene overexpression level is very important for decision-making and clinical application of basic results, in the current work, we have evaluated the accuracy of drrA and drrB gene overexpression as a guide for drug application in clinical practice. We believe that this is the first report on the validation of drrA and drrB gene overexpression folds in relation to the clinical application of target drugs. ROC analysis on our results showed that both drrA and drrB are valuable for TB therapy decision-making and categorizing the drug susceptibility or resistance of MTB strains. In fact, both genes showed proper diagnostic accuracy regarding their sensitivity and specificity. For differentiation of resistant from susceptible MTB isolates, the calculated cutoff values had acceptable sensitivity and specificity in addition to positive and negative predictive values. Thus, we suggest that the folds >1.6 and >2.3 be considered as cutoff values for drrA and drrB overexpression folds, respectively, in future studies.

Our work has some limitations. First, the number of MDR and INH monoresistant isolates was low, and for justification of the role of ABC transporter, we need to extend the duration of our future studies in order to have more isolates with such resistance phenotypes, and second, we did not study the efflux pump inhibitors, which principally bind to efflux pumps to inhibit drug efflux and thus enhance the drug effect and reduce drug resistance. So, further studies on the inhibitors targeting the efflux pumps of MTB help to understand MTB resistance and to identify the potential drug target and are of significance in guiding the development of new anti-TB drugs and optimal combinations as other investigators stated.32 Moreover, a good idea for the future studies could be to evaluate the global regulators for these pumps and the effect of the environmental signal on them.

The results of the present study confirm the role of DrrA-DrrB efflux pump in antibiotic resistance in clinical MTB isolates. As a large number of efflux pumps are located in the cell envelope of MTB, we cannot correlate a single efflux pump overexpression to the drug-resistance phenotype in a certain MTB cell, unless all the pumps are simultaneously investigated. However, such studies may suggest that the potentiation therapies targeting the efflux pumps could be considered in the future investigations to be included in TB standard antibiotic therapy. Furthermore, we presented potential cutoff points of gene expression folds by which molecular diagnostic laboratories would be able to detect the drug-resistant strains of MTB with proper sensitivity and specificity, in addition to well positive and negative predictive values.

Acknowledgment

This work is part of MSc. thesis of Zahra Absalan, which was approved in Infectious and Tropical Diseases Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran, which is appreciated. We are grateful to research affairs of the university for financial support of the study (Grant No.: OG-96117). We are also greatly thankful to the staff of Regional TB Reference Laboratory especially Nazanin Ahmadkhosravi for their collaboration in sample collection.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Raviglione M, Sulis G. Tuberculosis 2015: burden, challenges and strategy for control and elimination. Infect Dis Rep. 2016;8(2):6570. doi: 10.4081/idr.2016.6570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global tuberculosis report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js23553en/. Accessed on September 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastos ML, Hussain H, Weyer K, et al. Treatment outcomes of patients with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis according to drug susceptibility testing to first-and second-line drugs: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(10):1364–1374. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen L. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms in M. tuberculosis: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90(7):1585–1604. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1727-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. consolidated guidelines on drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311390/WHO-CDS-TB-2019.3-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange C, Abubakar I, Alffenaar JW, et al. Management of patients with multidrug-resistant/extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(1):23–63. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00188313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palomino J, Martin A. Drug resistance mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antibiotics. 2014;3(3):317–340. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics3030317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coelho T, Machado D, Couto I, et al. Enhancement of antibiotic activity by efflux inhibitors against multidrug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from Brazil. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:330. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machado D, Coelho TS, Perdigão J, et al. Interplay between mutations and efflux in drug resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:711. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazando S, Zimudzi C, Zimba M, et al. High efflux pump activity and gene expression at baseline linked to poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes. J Med Biomed Sci. 2017;6(1):8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balganesh M, Dinesh N, Sharma S, Kuruppath S, Nair AV, Sharma U. Efflux pumps of Mycobacterium tuberculosis play a significant role in antituberculosis activity of potential drug candidates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(5):2643–2651. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06003-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández L, Hancock RE. Adaptive and mutational resistance: role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(4):661–681. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00043-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braibant M, Gilot P, Content J. The ATP binding cassette (ABC) transport systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24(4):449–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhuri BS, Bhakta S, Barik R, Joyoti BA, Kundu M, Chakrabarti P. Overexpression and functional characterization of an ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transporter encoded by the genes drrA and drrB of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem J. 2002;367(1):279–285. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kent PT. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory, 1985. Available from: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10027388578 Accessed September27, 2019.

- 16.Hosek J, Svastova P, Moravkova M, Pavlik I, Bartos M. Methods of mycobacterial DNA isolation from different biological material: a review. Vet Med (Praha). 2006;51(5):180–192. doi: 10.17221/5538-VETMED [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocagöz T, Yilmaz E, Ozkara S, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum samples by polymerase chain reaction using a simplified procedure. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31(6):1435–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods GL. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes. Approved Standard M24-A2 31. 2011Available from: https://clsi.org/media/1463/m24a2_sample.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Zhang J, Guo Q, et al. Efflux pump gene expression in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0119013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederweis M. Mycobacterial porins–new channel proteins in unique outer membranes. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49(5):1167–1177. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy SB. Active efflux, a common mechanism for biocide and antibiotic resistance. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:65S–71S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.92.5s1.4.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amaral L, Martins A, Spengler G, Molnar J. Efflux pumps of Gram-negative bacteria: what they do, how they do it, with what and how to deal with them. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4:168. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang X, Zhang W, Zhang Y, et al. Assessment of efflux pump gene expression in a clinical isolate Mycobacterium tuberculosis by real-time reverse transcription PCR. Microb Drug Resist. 2008;14(1):7–11. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2008.0772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Da Silva PE, Von Groll A, Martin A, Palomino JC. Efflux as a mechanism for drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;63(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00831.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta AK, Katoch VM, Chauhan DS, et al. Microarray analysis of efflux pump genes in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis during stress induced by common anti-tuberculous drugs. Microb Drug Resist. 2010;16(1):21–28. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang K, Pei H, Huang B, et al. The expression of ABC efflux pump, Rv1217c–rv1218c, and its association with multidrug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in China. Curr Microbiol. 2013;66(3):222–226. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0215-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bansal A, Mallik D, Kar D, Ghosh AS. Identification of a multidrug efflux pump in Mycobacterium smegmatis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363(13):fnw128. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pang Y, Lu J, Wang Y, Song Y, Wang S, Zhao Y. Study of the rifampin mono-resistance mechanism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(2):893–900. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01024-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calgin MK, Sahin F, Turegun B, et al. Expression analysis of efflux pump genes among drug-susceptible and multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates and reference strains. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76(3):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machado D, Couto I, Perdigão J, et al. Contribution of efflux to the emergence of isoniazid and multidrug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e34538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song L, Wu X. Development of efflux pump inhibitors in antituberculosis therapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47(6):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]