Summary

Leading suicide theories and research in adults suggest that pain may exacerbate an individual’s suicidal risk. Although pain and suicidality both increase in prevalence during adolescence, their relationship remains unclear. We aimed to systematically review the empirical evidence for an association between pain and suicidality in adolescence (PROSPERO: CRD42018097226). In total, 25 observational studies, published between 1961 and December 2018, exploring the potential pain-suicidality association in adolescence (10-19 years) were included. Across various samples and manifestations of pain and suicidality, we found that pain approximately doubles adolescents’ suicidal risk, with a few studies suggesting that pain may predict suicidality longitudinally. Although depression was an important factor, it did not fully explain the pain-suicidality association. Evidence on associations between pain characteristics and suicidality is sparse and inconclusive, potentially hiding developmental differences. Identification of psychological mediators and moderators is required to develop interventions tailored to the needs of adolescents in pain.

Introduction

Although suicide can affect people at all stages of life, it accounts for a major proportion of deaths amongst young people worldwide.1,2 Death by suicide marks the fatal endpoint of the suicidality risk spectrum, which ranges from cognitions about suicide and self-harm (i.e., suicidal ideation) through suicidal behaviours (i.e., the actual act of harming oneself irrespective of suicidal intent and levels of medical severity) to death by suicide.3 These non-fatal manifestations of suicidality are a common public health problem in adolescents (lifetime suicidal ideation: 29·9%; history of suicidal behaviour: 9·7%4,5), particularly between the ages of 12 and 17 years.6,7 Thus, knowledge of the factors that promote risk and resilience to the development of suicidality and the transition from suicidal ideation to acts in adolescents is crucial.8

Leading theories of suicidality9–12 and empirical research in adults13–15 emphasize the role of pain in increasing an individual’s suicidal risk. However, pain is a complex phenomenon and little is known about which aspects of the pain experience, including sensory (e.g., pain sensitivity), cognitive (e.g., pain catastrophizing) and affective-motivational components of pain (e.g., unpleasantness of pain16,17), confer an increased suicidal risk.18 Alternative ways of describing pain are by its duration and/ or the impact of pain on functioning. Whilst ‘acute pain’ is short-lived (i.e., < 3 months) and caused by an identifiable disease or injury,19 ‘chronic pain’ refers to an enduring primary health condition (i.e., ≥ 3 months) of persistent or recurrent pain that significantly impairs patients’ wellbeing and functioning, despite treatment of an underlying medical condition.20 In this review, ‘pain’ refers to the presence of both acute and chronic pain conditions, aspects of the pain experience and functional impairment.

Although research has shown that prevalence rates of chronic pain tend to increase substantially from the age of 12 years onwards (median prevalence rate: 11-38%21,22), little is known about the pain-suicidality association in adolescents. In keeping with the definition proposed by the World Health Organisation,23 we define adolescence as a distinct developmental period, ranging from 10 to 19 years of age. During these critical years of development, young people undergo marked physical, neuro-cognitive and social changes that may precipitate or protect against the emergence of various (mental) health outcomes in adulthood.24,25 Pain during adolescence is predictive of pain in adulthood.22,26 However, the manifestation of pain may vary between adolescents and adults,21,27 and its effects may be particularly detrimental in adolescence, particularly by interfering with the adaptive development during this critical period.28

Given the growing support for a relationship between pain and suicidality in adults (see Racine13, Rizvi et al.14 and Tang et al.15), establishing whether a similar relationship exists in adolescents has the potential to enhance our understanding of the interplay between physical and mental suffering in this age group, and to inform the development of prevention strategies.6,29

In this paper, we report the findings of a systematic review designed to synthesise and critically evaluate the existing empirical evidence for an association between pain and suicidality in adolescence.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The protocol for the systematic review is compliant with the recommendations of the PRISMA statement30 and was pre-registered in PROSPERO [CRD42018097226].

A comprehensive search strategy was used to identify candidate studies, developed in liaison with an information specialist and experts on pain and suicide research (see supplement 1). Literature searches were performed in Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycINFO, Ovid Medline, EBSCO CINAHL, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, alongside checking of grey literature (ProQuest Dissertations and Theses; OpenGrey: opengrey.eu/), trial registers (ClinicalTrials.gov), conference proceedings (Web of Science and Embase), backward and forward citation screening and correspondence with authors of included studies, between June, 7th and December, 3rd, 2018. As the main database search yielded an additional key term (self-mutilation), the search was repeated on July, 3rd, 2018, focussing in the second round solely on self-mutilation as a measure of suicidality. An inclusive approach to eligibility assessment was taken. Studies were deemed eligible if they explored and provided data on the potential relationship between suicidality and pain in adolescence. No restrictions were placed on the type or the assessment of suicidality, pain or the research setting. In addition, studies (sampling both adolescents and adults) were included, provided data could be extracted for the subsample of adolescents (i.e., those aged 10 to 19 years23). In order to minimise between-study heterogeneity, only observational studies (i.e., cross-sectional, cohort and case-control studies) were included.

Studies were excluded if (1) the study did not allow to establish an association between pain and suicidality, (2) no data could be extracted for adolescents, (3) the study focussed on clearly distinct populations (e.g., animal studies, military studies, prison cohorts, and end-of-life care), (4) they did not provide original data (e.g., reviews, editorials, or opinion papers), (5) they did not use an observational study design (e.g., intervention studies, experimental studies and qualitative research), (6) they experimentally induced pain, (7) they used mixed measures of pain and suicidality (e.g., pain during self-harm) or measures of the perception of pain in comparison to other people, and (8) they were published in any other language than English. Furthermore, studies published before 1961 (the year of decriminalisation of suicide in England and Wales31) or after December 2018, and duplicates, were excluded from this review.

Using Covidence32, two independent reviewers (VH and LQ) performed the eligibility assessments between June, 7th and December, 3rd, 2018. Title and abstract screening was followed by full-text screening. Inter-rater reliabilities were calculated, using the percentage agreement with a threshold of ≥ 0·8 indicating acceptable inter-tater reliability. Between-rater discrepancies were resolved through discussion and where necessary through involvement of a third independent reviewer (BG).

Data extraction and quality assessments

Two independent reviewers (VH & RB) performed the data extraction, using a standardised pre-piloted data extraction form (see supplement 2). Authors were contacted to provide missing (subsample) data where necessary. Two studies used the same dataset, as an already included study (Young-Hunt33,34, Add Health35,36). We decided to treat all four studies separately, as data on different measures, subsamples35,36 and follow-up waves33,34 were reported, precluding a combined discussion of the study results.

Two independent reviewers (VH & LQ) performed the quality assessments, using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale ([NOS]37) for nonrandomised studies.38,39 Each study was evaluated on an item-basis to advance future research. Quality assessments were not used to determine eligibility, but to gauge the validity of the results and to generate guidelines for future research. Inter-rater reliabilities for the data extraction and quality assessments were calculated using the percentage agreement, and discrepancies between raters were resolved through discussion, and involvement of a third, independent reviewer (BG), if necessary.

Data synthesis

Given the large between-study heterogeneity in the exposure and outcome of interest, as well as in the population studied and statistics being used, a meta-analysis was considered to be inappropriate40 and a narrative synthesis of aggregated and individual study findings was conducted, primarily using risk measures.

Role of the funding source

The first author, VH, is funded by the Oskar-Helene Heim Foundation and the FAZIT foundation. CC, is funded by the Wellcome Trust, Grant Number 107496/Z/14/Z. RB is funded by Defehr-Neumann foundation. BG is funded by the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo. The funding organisations had no role in the study design, data collection, data extraction, data interpretation, or writing of this report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

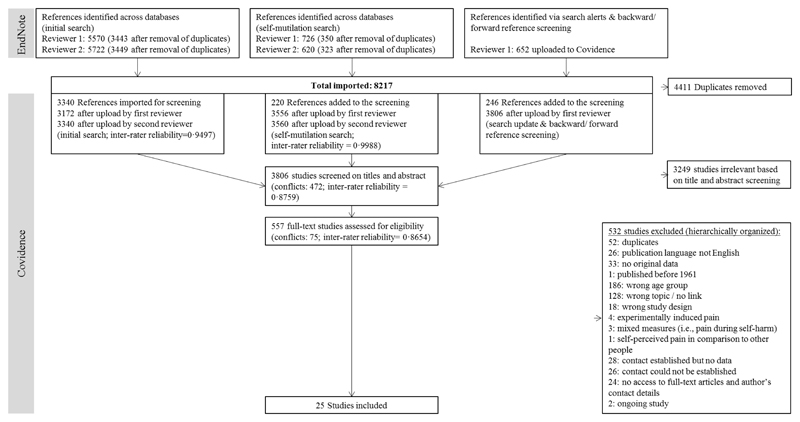

The comprehensive search strategy yielded 8217 references (figure 1). After deduplication, 3806 were retained for title and abstract screening, of which 557 studies were considered for full-text review. Independent review resulted in a total sample of 25 studies. Interrater agreement across the study selection phases and the data extraction phase was high (selection: percentage agreement=86·5-99·8%; data extraction: percentage agreement=97·7%).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow-chart of the data search and eligibility assessment.

The majority of selected studies had been published in the last decade (n=2033,34,36,41–57; 80% published after 2010; table 1). Studies were geographically diverse, and mainly based on community samples (n=1733–36,43,44,46–51,53,55,57–59), using cross-sectional designs (n=1835,41,43,46,47,49–61). Eighteen studies recruited participants aged 10 to 19 years,33–36,42,45–48,50–53,57–61 whilst in 7 studies data on adolescents within a broader age sample were made available by the authors.41,43,44,49,54–56

Table 1. Study characteristics (N=25).

| Study | Country | Population | Age range (years) | Sample size (number of adolescents if different) | Type of pain | Method of pain assessment a | Type of suicidality | Method of suicidality assessment a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation [SI] / suicidal risk (n=9) | ||||||||

| Cross-sectional study | ||||||||

| Fuller-Thomson et al., 201346 | Canada | Community sample | 15-19 | 5.788 | Migraine headache, back problems, activities prevented by pain | Interview (–) | Suicidal ideation (past 12 months) | Interview (–) |

| Halvorsen et al., 201247 | Norway | Community sample | 18-19 | 3.775 | Pain sites (composed of pain in the head, neck/ shoulder, arms/legs, stomach and back; past 12 month) | Self-report (–) | Suicidal ideation (past week) | Self-report (/) |

| Chan et al., 200958 | China | Community sample | 15-19 | 511 | Chronic illness or pain | Interview (–) | Suicidal ideation (composed of lifetime & past year) | Self-report (/) |

| Wang et al., 200959 | Taiwan | Community sample | 13-15 | 3.963 | Migraine diagnosis (with/ without aura), headache frequency, headache disability (past 3 months) | Self-report (+) | Suicidal ideation (past month) | Self-report (/) |

| Lewcun et al., 201852 | USA | Adolescents diagnosed with amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome (AMPS) | 11–17 | 453 | Family history of pain disorder Pain severity Pain duration (months) Functional disability | Patient registries (+), self-report (+), & interview (–) | Suicidal ideation (past two weeks) | Self-report (/) |

| Wang et al., 200761 | Taiwan | Adolescents diagnosed with chronic daily headache | 12-15 | 122 | Migraine diagnosis (yes/ no, with/ without aura) | Interview (+) | Suicidal risk (past month) | Interview (+) |

| Cohort study | ||||||||

| Strandheim et al., 2014b,34 | Norway | Community sample | T0: 13-15 T1: 17-19 | 2.399 | Physical pain & tension problems (past year) | Self-report (/) | Suicidal ideation (past month) | Self-report (–) |

| Case-control study | ||||||||

| Eliacik et al., 201745 | Turkey | Adolescents with vs. without non-cardiac chest pain | 13–18 | 176 | Non-cardiac chest pain | Diagnostic evaluation (+) | Suicidal ideation | Interview (–) |

| Bromberg et al., 201742 | USA | Adolescents with vs. without chronic pain [CP] | 12-18 | 186 | Chronic pain; pain intensity & pain bother (past 3 months) | Self-report (+) | Suicidal ideation | Self-report (+) |

| Suicidal behaviour [SB] / self-harm (n=6) | ||||||||

| Cross-sectional study | ||||||||

| Liu et al., 201853 | China | Community sample | 12–18 | 5.813 | Period pain (no, mild, moderate, severe) | Self-report (–) | Non-suicidal self-injury ([NSSI], lifetime & past year) | Self-report (/) |

| Koenig et al., 201550 | Germany | Community sample | 13-18 | 5.504 | General pain (aches or pains), recurrent pain headache, abdominal pain/ stomach ache | Self-report (+) | Frequency of self-injury per year & suicidal attempt ([SA]; ever) | Self-report (+) |

| Tsai et al., 201157 | Taiwan | Community sample | 15-18 | 742 | Headache | Self-report (–) | Self-harm (ever) | Self-report (–) |

| Bayramoglu et al., 201541 | Turkey | Adult suicide attempts | 14-88 | 533 (n=145) | Chief complaint: Headache & Abdominal pain | Interview (–) | Type of suicide attempt (aggressive vs. non-aggressive) | Interview (–) |

| Reigstad et al., 200660 | Norway | Adolescents attending the child & adolescent psychiatric services | 12–18 | 129 | Any frequent pain (composed of headaches, stomach pain, back pain & limb pain) | Self-report (–) | Self-harm (ever) & suicide attempt ([SA]; ever) | Self-report (–) |

| Cohort study | ||||||||

| Junker et al., 2017b,33 | Norway | Community sample | T0 to T1: 13-19 | T0: 8.965 T1: 5.152 |

Migraine (≥6 months), frequent headache, stomach pain (past year) | Self-report (–) | Self-harm hospitalisation | Interview (+) & Patient records (+) |

| Death by suicide (n=1) | ||||||||

| Cohort study | ||||||||

| Ekholm et al., 201444 | Denmark | Community sample | 16-65+ | 13.127 (n=unclear) | Chronic non-cancer pain (past 6 months) | Self-report (–) | Death by suicide | Patient registries (+) |

| Suicidality (mixed assessments; n=9) | ||||||||

| Cross-sectional study | ||||||||

| Ren et al., 201955 | China | Community sample | 15-21 | 930 (n=926) | Pain tolerance & Pain sensitivity | Self-report (/) | Suicidal ideation & attempts (past year) | Self-report ( +; / ; – ) |

| Lee et al., 201751 | Taiwan | Community sample | 11–18 | 6.150 | Pain-related quality of life (past 2 weeks) | Self-report (+) | Suicidality (composed of four types of suicidal ideation & suicide attempts; past year) | Self-report (+) |

| Campbell et al., 201543 | Australia | Community sample | 16-85 | 8.841 (n=706) | Any chronic pain (composed of arthritis, migraines, back/neck problems; past 6 months) vs. no pain | Interview (/) | Suicidal ideation, plans & attempts (past 12 months) | Interview (/) |

| Kirtley et al., 201549 | Scotland | Student sample | Mage=19·8 (SD=4·2) | 351 (n=234) | Pain distress & sensitivity | Self-report (+) | Suicidal ideation & behaviour | Self-report (/) |

| Alriksson-Schmidt, 2008c,35 | USA | Community sample | M=15·96 (SE = 0·11) | 22.261.000 (n=6.357 available for SI analyses; n=6.400 available for SA analyses) | Physical pain (composed of headache, stomach aches, joint pain; past 12 months) | Self-report (/) | Suicidal ideation [SI] & attempts ([SA]; past year) | Self-report (–) |

| Park et al., 201554 | Republic of Korea | Hospital-based study of migraine patients | 15-75 | 220 (n=23) | Migraine (composed of ever & now) | Self-report (+) & Interview (+) & Patient records (+) | Suicidality | Interview (+) |

| Rozen et al., 201256 | USA | Patients, diagnosed with cluster headache, from the community | <20-61+ | 1.134 (n=7) | Cluster headache | Self-report (–) | Suicidality | Self-report (–) |

| Cohort study | ||||||||

| Hogstedt et al., 201848 | Sweden | Swedish males, who were conscripted for compulsory military service in 1969 and 1970. | 18-20 | 49.321 (suicide: N=619; Suicide attempt: N=1.102) | Headache, stomach pain, both symptoms collapsed as general pain | Self-report (–) | Death by suicide & suicidal attempts during follow-up | Patient registries (+) |

| Van Tilburg et al., 2011c,36 | USA | Community sample | 11–18 | T0: 9.970 T1: 9.925 |

(a) headache, (b) stomach ache/upset stomach, (c) aches, pains/ soreness in muscles or joints (past year) | Self-report (–) | Suicidal ideation & attempt (past year) | Self-report (–) |

Note. Studies are grouped by the type of suicidality being measured and the study design being used. Furthermore, they are grouped by the study population, with the most recent studies being presented first. Community samples: Depending on the scale of the study, some of the samples represent large-scale national or regional surveys.

Validated tools are marked with (+) Validated single items/ questions taken, or single items/ questions taken from validated tools are marked with (/) and non-validated single items/ questions are marked with (-)

Study quality was assessed (see supplement 3), with substantial interrater agreement (percentage agreement=77·7-83·3%). Although 17 studies scored positively on at least half of the assessment criteria,33–36,42,44–48,50–53,58,59,61 study limitations became apparent in several domains, including the assessment of the exposure (i.e., pain; n=1733–35,41,42,45,47–51,53,55–57,59,60) and the outcome (i.e., suicidality; n=1634–36,41,47,49–53,55–60). Other major limitations involve the failure to justify sample size (n=941,43,49,54–57,60,61), inappropriate use and reporting of statistical tests (n=741,43,49,54–57), high number of non-respondents (n=735,43,49,52,56,58,60) and failure to control for potential correlates, such as age, gender and/ or depression (n=641,43,49,54,56,60).

Table 2 shows the individual study results, structured around the type of suicidality and the level of support provided for the potential pain-suicidality association. The majority of studies reviewed provided support for the hypothesised pain-suicidality association in adolescence. In three studies the relationship between pain and suicidality remained unclear, as no test statistics were available.43,54,56

Table 2. Study results, structured around the type of suicidality.

| Variables used to establish the pain-suicidality association | Results | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study design | Population | Type of pain | Type of suicidality | Control for covariates | Significant crude probability estimates [95%CI]; otherwise frequencies | Significant adjusted probability estimates [95%CI] | Number of tested and non-significant pain-suicidality associations | Study quality |

| Suicidal ideation/ suicidal risk (n=9) | |||||||||

| Full support | |||||||||

| Chan et al., 200958 | CS | Community sample | Chronic illness or pain | Suicidal ideation (composed of lifetime & past year) | Demographics | OR=6·4 [2·5-16·2] | aOR=4·9, [1·7-14·3] | 0 | 5/8 |

| Strandheim et al., 2014c,34 | CH | Community sample | Physical pain & tension problems (past year) | Suicidal ideation (past month) | Demographics psychiatric symptoms & health-related factors | OR=2·7 [2·1-3·4] | aOR=1·8, [1·4-2·4] | 0 | 6/9 |

| Eliacik et al., 201745 | CC | Adolescents with vs. without non-cardiac chest pain | Non-cardiac chest pain | Suicidal ideation | Demographics | Cases = 22% (n=22/100) vs. controls = 5·26% (n=4/76), p < 0·001 | Not reported | 0 | 6/9 |

| Partial support a. | |||||||||

| Halvorsen et al., 201247 | CS | Community sample | Pain sites (composed of pain in the head, neck/ shoulder, arms/legs, stomach and back; past 12 month) | Suicidal ideation (past week) | Demographics & depression | OR(1-2 pain sites)=1·5

[1·0–2·2]; OR(3-5 pain sites)=4·7; [3·2–6·8] |

aOR(3-5 pain sites)=1·8, [1·3-2·5] | 1: aOR non-sig for 1-2 pain sites | 6/8 |

| Fuller-Thomson et al., 201346 | CS | Community sample | Migraine headache, back problems, activities prevented by pain | Suicidal ideation (past 12 months) | Demographics, depression & health-related factors | Migraine: Yes = 7·2% (n=425/5788) vs.

no = 3·6% (n=5363/5788), p < 0·001 Back pain: Yes = 7·6% (n=482/ 5788) vs. no = 3·5% (n=5306/5788), p < 0·001 Activities prevented: Yes = 12·6% (n=216/ 5783) vs. no = 3·5% (n=5567/5783), p < 0·001 |

a1OR(activities)=2·0, [1·2-3·4] | 5: a1OR(controlling

for demographics & health) non-sig for

migraines & back pain; a2OR (controlling for depression) non-sig for migraines & back pain; activities prevented by pain |

8/8 |

| Wang et al., 200959 | CS | Community sample | Migraine diagnosis (with/ without aura), headache frequency, headache disability (past 3 months) | Suicidal ideation (past month) | Demographics & depression | OR(migraine diagnosis vs. no migraine)= 2·9 [2·3-3·6]; OR(migraine no aura/ probable migraine vs. no migraine)= 2·4 [1·9-3·1]; OR(migraine with aura vs. no migraine)=4·6 [3·0-7·0]; OR(migraine with aura vs. no aura/ probable migraine)=1·8 [1·2-2·8]; higher headache frequency (3·6+-4·4 vs. 1·6 +-2·8 days/month; p< 0·001) headache-related disability (8·0+-19·7 vs. 2·5 +-7·9 p< 0·001) | aOR(migraine with aura)=1·8

[1·1-3·0]; aOR(frequency >7-14 days/month)= 1·7 [1·1-2·6] |

2: aOR non sig. for migraine without aura/ probable migraine and headache-related disability | 6/8 |

| Lewcun et al., 201852 | CS | Adolescents diagnosed with amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome (AMPS) | Family history of pain disorder Pain

severity Pain duration (months) Functional disability |

Suicidal ideation (past two weeks) | Demographics & depression | Not reported | a1OR(pain duration)=1·0

[1·0-1·0] a2OR(pain duration)= non-sig. |

4: a1OR (controlling for

demographics) non-sig for family history of

pain; pain severity; functional disability a2OR (controlling for depression): pain duration non-sig |

5/8 |

| Wang et al., 200761 | CS | Adolescents diagnosed with chronic daily headache | Migraine diagnosis (yes/ no, with/ without aura) | Suicidal risk (past month) | Demographics & depression/ anxiety | Migraine: OR=4·3 [1·2-15·5] | aOR(migraine with aura vs. no migraine)=7·8 [1·4-44·6] | 1: aOR non-sig for migraine without aura vs. no migraine | 7/8 |

| No support | |||||||||

| Bromberg et al., 201742 | CC | Adolescents with vs. without chronic pain [CP] | Chronic pain; pain intensity & pain bother (past 3 months) | Suicidal ideation | Demographics & depression | none | Not reported | 1: Cases 34·7% (33/95) vs. controls 27·5% (25/91), p >0·05 | 6/9 |

| Suicidal behaviour / non-suicidal self-injury (n=6) | |||||||||

| Full support | |||||||||

| Tsai et al., 201157 | CS | Community sample | Headache | Self-harm (ever) | Gender & behaviour/ health-related factors | OR=6·5, [3·7-11·5] | aOR=9·0, [4·6-17·6] | 0 | 3/8 |

| Reigstad et al., 200660 | CS | Adolescents in child & adolescent psychiatric services | Any frequent pain (composed of headaches, stomach pain, back pain & limb pain) | Self-harm (ever) & suicide attempt ([SA]; ever) | N/A | OR(self-harm)=2·7,

[1·3-5·6]; OR(SA)=2·3, [1·1-5·0] |

N/A | 0 | 2/8 |

| Junker et al., 2017 c,33 | CH | Community sample | Migraine (≥6 months), frequent headache, stomach pain (past year) | Self-harm hospitalisation | Demographics | HR(migraine)=2·7,

[1·3-5·9]; HR(headache)=2·7, [1·7-4·2]; HR(stomach pain)=2·7, [1·8-4.3] |

aHR(migraine)=2·3,

[1·1-5·1]; aHR(headache)=2·2, [1·4-3·5]; aHR(stomach pain)=2·2, [1·4-3·5] |

0 | 6/9 |

| Partial support a. | |||||||||

| Liu et al., 201853 | CS | Community sample | Period pain (no, mild, moderate, severe) | Non-suicidal self-injury ([NSSI], lifetime & past year) | Demographics psychiatric symptoms & BMI & impulsivity | NSSI lifetime: OR(mild-severe)=

1·3-2·0f. NSSI past year: OR(mild-severe)= 1·3-2·1 f. |

NSSI lifetime: a2OR(mild-moderate)=

1·2-1·3 f. NSSI past year(mild-moderate): a2OR=1·2-1·3 f. |

2: a2OR (adjusting for all covariates): non-sig for severe pain and NSSI lifetime & past year | 6/8 |

| Koenig et al., 201550 | CS | Community sample | Recurrent pain, as well as general pain (aches or pains), headache, abdominal pain/ stomach ache (for general, headache and abdominal pain: sometimes vs. very often) | Frequency of self-injury per year (1-3x/year vs. <3x/year) & suicidal attempt ([SA]; 1 SA vs. multiple SAs, ever) | Demographics & psychiatric symptoms |

Self-injury

1-3x/year: RR(recurrent vs. no pain)=3·0 [2·4–3·6]; RR(general)=1·7-2·6 e. RR(headache)=1·3-1·9 e. RR(abdominal)=1·7-2·7 e. Self-injury >3x/year: RR(recurrent)= 6·0 [4·4–8·2]; RR(general)=2·0-3·2 e.; RR(headache – very often)= 2·5 [1·5-4·1]; RR(abdominal)=2·0-5·1 e. One SA: RR(recurrent)= 3·6 [2·8–4·6]; RR(general)=1·8-2·7 e.; RR(headache – very often)= 2·6 [1·7–3·9]; RR(abdominal)=2·2-2·3 e. Multiple SA: RR(recurrent)= 5·5 [3·8–7·8]; RR(general)=2·0-2·8 e.; RR(abdominal)=1·7-5·8 e. |

Self-injury 1-3x/year:

a2RR(recurrent)=1·4,

[1·2-1·8] a2RR(general pain – very often)= 1·6, [1·1-2·2]; Self-injury >3x/year: a2RR(recurrent)=1·8, [1·3-2·6]; One SA: a2RR(recurrent)=1·4, [1·1-1·8]; a2RR(headache – very often)=1·6, [1·0-2·3]; a2RR(abdominal pain-sometimes)=1·5, [1·1-2·1]; Multiple SA: a2RR(recurrent)=1·8, [1·2-2·6]; a2RR(abdominal pain – very often)=2·0, [1·1-3·5] |

30: OR non-sign. for

self-injury > 3x/year & headaches(sometimes);

one SA & headaches(sometimes); multiple SA &

headaches(sometimes & very

often); a1OR (controlling for demographics) non-sig for self-injury 1-3x/year & headaches(sometimes); self-injury >3 & headaches(sometimes); one SA & headaches(sometimes); multiple SA & headaches(sometimes & very often) & abdominal pain (sometimes); a2OR (all covariates): non-sig for self-injury 1-3x/year & general pain (sometimes) & headaches(sometimes & very often) & abdominal pain(sometimes & very often); self-injury >3 & general pain(sometimes & very often) & headaches(sometimes & very often) & abdominal pain (sometimes & very often); one SA & general pain(sometimes & often) & headaches(sometimes); abdominal pain (often); multiple SA & general pain(sometimes & often) & headaches(sometimes & often) & abdominal pain (sometimes) |

6/8 |

| No support | |||||||||

| Bayramoglu et al., 201541 | CS | Adult suicide attempts | Chief complaint: Headache & Abdominal pain | Type of suicide attempt (aggressive vs. non-aggressive) | N/A | none | Not reported | 2: Headache: 11·8% (2/17) vs.

9·4% (12/128), p=0·60 Abdominal pain:

17·6% (3/17) vs. 34·4% (44/128), p=0·37 |

2/8 |

| Death by suicide (n=1) | |||||||||

| No support | |||||||||

| Ekholm et al., 201444 | CH | Community sample | Chronic non-cancer pain (past 6 months) | Death by suicide | N/A | none | Not reported | 1: Death by suicide: n=0 | 7/9 |

| Suicidality (overall) & mixed assessments (n=9) | |||||||||

| Full support | |||||||||

| Lee et al., 201751 | CS | Community sample | Pain-related quality of life (past 2 weeks) | Suicidality (composed of four types of suicidal ideation & suicide attempts; past year) | Demographics | Not reported | aOR=0·97 [0·97-0·98] | 0 | 5/8 |

| Alriksson-Schmidt, 2008 d,35 | CS | Community sample | Physical pain (composed of headache, stomach aches, joint pain; past 12 months) | Suicidal ideation [SI] & attempts ([SA]; past year) | Demographics & severity of mobility limitations | Not reported | aOR(SI)?=1·2, [1·2-1·3]; aOR(SA)=1·2, [1·1-1·3] | 0 | 5/8 |

| Partial support a. | |||||||||

| Ren et al., 201955 | CS | Community sample | Pain tolerance & Pain sensitivity | Suicidal ideation & attempts (past year) | Gender | Not reported |

Suicidal ideation [SI] vs.

control aOR(pain tolerance)=1·4, [1·1-1·8] Suicidal behaviour [SA] vs. control aOR(pain sensitivity)= 0·63, [0·42-0·96]; aOR(pain tolerance)=1·9, [1·2-3·1] |

3: aOR non sign. for SI vs. control & pain sensitivity; for SB vs. SI & pain sensitivity/ pain tolerance | 2/8 |

| Kirtley et al., 201549 | CS | Community sample | Pain distress & sensitivity | Suicidal ideation & behaviour | N/A | Pain distress: z=2·4, p=0·018 | Not reported | 1: Pain sensitivity: z=1·0, p=0·300 | 0/8 |

| Hogstedt et al., 201848 | CH | Swedish males, who were conscripted for compulsory military service in 1969 and 1970. | Headache, stomach pain, both symptoms collapsed as general pain (categorised based on limited and severe symptoms) | Death by suicide & suicidal attempts [SA] during follow-up | Demographics, psychiatric diagnosis & other symptoms | Death by suicide: HR(severe

headache)= 1·4 [1·0–2·0];

HR(severe stomach pain)= 1·5

[1·1–2·1]; HR(sever headache & stomach

pain)=1·6 [1·2-2·3] Suicide attempt: HR(limited-severe headache)=1·1-1·9 e.; HR(severe stomach pain)= 2·1 [1·7-2·6]; HR(sever headache & stomach pain)=1·1-2·3 e. |

Suicide attempt: aHR(severe headache)=1·5, [1·1-2·2] | 24: OR non-sig. for

suicide & headache(limited), stomach

pain(limited) & headache/stomach pain

(limited); for suicide attempts & stomach

pain(limited) a1OR(controlling for psychiatric diagnosis) non sig. for suicide & headache(limited-severe), stomach problems (limited-severe), & headache/stomach problems (limited-severe); for SA & headache(limited), stomach problems (limited), & headache/ stomach problems (limited) a2OR(controlling for other symptoms) non sig. for suicide & headache(limited-severe), stomach problems (limited-severe) & headache/ stomach problems (limited-severe); for SA & headache(limited),stomach problems (limited severe) & headache/ stomach problems (limited-severe) |

6/9 |

| Van Tilburg et al., 2011d,36 | CH | Community sample | (a) headache, (b) stomach ache/upset stomach, (c) aches, pains/ soreness in muscles or joints (past year) | Suicidal ideation & attempt (past year) | Demographics & depression |

Suicidal

ideation: OR(headache-wave 1&2)=1·5-1·7 e.; OR(stomach pain-wave 1&2)=1·6-1·9 e.; OR(musculoskeletal pain–wave 1&2)=1·5-1·4 e. Next-year suicidal ideation (excl. wave 1 SI): OR(headache)=1·2 [1·0-1·5] OR(stomach pain)=1·4 [1·1-1·7]; Suicide Attempt [SA]: OR(headache-wave 1&2)=1·4-2·1 f.; OR(stomach pain-wave 1&2)=1·8 e. OR(musculoskeletal pain–wave 2)=1·5 [1·1–2·1] Next-year SA (excl. wave 1 SA): OR(stomach pain)=1·6 [1·2-2·1]; OR(musculoskeletal pain)=1·5 [1·1-2·1] |

Suicidal

ideation: aOR(headache-wave 1&2)=1·3-1·4 e.; aOR(stomach pain – wave 2)=1·4 [1·2-1·7]; aOR(musculoskeletal pain – wave 1)=1·3 [1·1-1·5]; Next-year suicidal ideation: aOR(headache)=1·2 [1·1-1·5] Suicide Attempt: aOR(headache-wave 2)=1·6, [1·2-2·2]; aOR(musculoskeletal pain–wave 2)=1·1 [0·8-0·9] |

14: OR non sig. for

next-year suicidal ideation (excl. wave 1 SI) & musculoskeletal

pain; for SA & musculoskeletal pain(wave 1); for

Next-year SA (excl. wave 1 SA) &

headache; aOR non sig. for SI & stomach pain(wave 1)/ musculoskeletal pain(wave 2); for Next-year SI (excl. wave 1 SI) & stomach pain/ musculoskeletal pain; for SA & headache(wave 1) /stomach pain(wave 1&2)/ musculoskeletal pain(wave 1); for next-year SA (excl. wave 1 SA) & headache/ stomach pain/ musculoskeletal pain |

7/9 |

| Pain-suicidality association unclear b. | |||||||||

| Campbell et al., 201543 | CS | Community sample | Any chronic pain (composed of arthritis, migraines, back/neck problems; past 6 months) vs. no pain | Suicidal ideation, plans & attempts (past 12 months) | N/A | Suicidal ideation(chronic pain):

11·1% (10/90) vs. 3·2% (20/616) Suicidal plan(chronic pain): 7·8% (7/90) vs. 0·8% (5/616); Suicidal attempt(chronic pain): 6·7% (6/90) vs. 0·9% (6/616) |

Not reported | Unclear | 3/8 |

| Park et al., 201554 | CS | Hospital based study of migraine patients | Migraine (composed of ever & now) | Suicidality | N/A | Suicidal risk: yes=30·4% (7/23) vs. no=69·6% (16/23) | Not reported | Unclear | 3/8 |

| Rozen et al., 201256 | CS | Patients, diagnosed with cluster headache | Cluster headache | Suicidality | N/A | Suicidal ideation: 71% (5/7); Suicidal behaviour: 14% (1/7); No suicidality: 29% (2/7) | Not reported | Unclear | 0/8 |

Note. CS = Cross-sectional Studies; CH = Cohort studies; CC = Case-control studies; OR = crude odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio. Within the table outcomes are further structured around the level of support and the population.

Results did not remain (or only partially remain) significant when controlling for covariates (e.g., depression) in multivariate models. Hence, results are reported for most significant outcomes: crude odds ratios (OR) or adjusted odds ratios (aOR), depending on whether or not the adjusted odds ratio still remained significant

The results are unclear, as no test statistics were available and only frequencies were reported.

Junker et al., 201733 and Strandheim et al., 201434 are partially based on the same dataset: Young Hunt.

Alriksson-Schmidt, 200835 and van Tilburg et al., 201136 are partially based on the same dataset: Add Health.

In these cases, pain has been divided into subcategories of varying severity levels and frequencies. To keep the table as concise a possible, we present the range of odds ratios over the different pain severity levels/ frequencies, instead of individual odds ratios. Therefore, confidence intervals are omitted.

Seven community-based studies34–36,46,47,58,59 and four clinical studies42,45,52,61 explored links between pain and suicidal ideation. In most of the community-based studies, pain increased the odds of suicidal ideation (e.g., see Halvorsen et al.47; Wang et al.59). Specifically, of the 4·5 to 17 percent of adolescents in community samples reporting suicidal ideation,34–36,46,47,58,59 adolescents with pain reported significantly higher levels of suicidal ideation compared to those without pain (with pain: 7·2-23·9% vs. no pain: 3·5-6·2%).46,47,59 However, probability estimates varied greatly between community samples (aOR=1·2-4·9; see table 2), and the statistical significance of the associations appeared to depend largely on the degree of control for covariates. All studies focussing on community samples accounted for demographics (n=734–36,46,47,58,59), consistently showing that pain increased the odds of suicidal ideation. This association persisted when additionally controlling for health-related factors (n=334,35,46), but inconsistencies appeared when studies also accounted for depression and other psychiatric symptoms (n=534,36,46,47,59). In one study, pain was significantly associated with suicidal ideation after additionally controlling for psychiatric symptoms (aOR=1·8, 95%CI=[1·4-2·4]).34 However, in other studies this association mostly diminished to non-significance after controlling for depression (see Halvorsen et al.47; Fuller-Thomson et al.46; Wang et al. 59; Van Tilburg et al.36). When focussing on clinical samples of adolescents in pain (n=442,45,52,61), three studies found significant associations between pain and suicidal ideation (aOR=1·0-7·845,52,61; percentage with suicidal ideation: 20-22%52,61, suicidal ideation with pain: 22% vs. without pain: 5·3%45), which were no longer apparent after controlling for demographics and depression.52,61 One study did not reveal any association between pain and suicidal ideation (suicidal ideation with pain: 34·7% vs. without pain: 27·5%).42

Nine studies explored the association between pain and suicidal behaviour,33,35,36,41,48,50,53,57,60 of which seven studies recruited community samples33,35,36,48,50,53,57 and two studies focussed on adolescents in psychiatric services.41,60 In community samples, pain increased the odds of suicidal behaviour, with large differences in probability estimates between community samples (aOR=1·2-9·0; see table 2), as a function of the degree of control for other correlates. Specifically, 1 to 21·4 percent of community adolescents reported suicidal behaviour.33,35,36,48,50,53,57 Adolescents with pain reported higher levels of suicidal behaviour than those adolescents without pain (with pain: 6-78% vs. without pain: 1·3-31·1%)48,50,53 and adolescents with pain reported higher rates of suicidal behaviour than no suicidal behaviour (7.9-61.8 vs. 3.4-39.2).33,57 All community-based studies (n=733,35,36,48,50,53,57) accounted for demographics either in the study design48 or through adding them as covariates (e.g., see Junker et al.33), and provided support for an association between pain and suicidal behaviour. In most studies, this association remained significant when adding behaviour- and health-related factors as covariates (n=435,48,53,57). However additional control for psychiatric symptoms (n=436,48,50,53), resulted in diminished associations. Of those studies that focussed on adolescents in psychiatric services (n=241,60), one study found a significant association between pain and suicidal behaviour (OR=2·3-2·7).60 Specifically, of the overall sample of adolescents in psychiatric services, 35·7 to 48·8 percent reported one type of suicidal behaviour. It remained unclear how many of those adolescents were also experiencing pain.60 However, adolescents who showed aggressive compared to non-aggressive suicidal behaviours did not significantly differ in their report of pain (aggressive suicidal behaviour and pain: 11·8-17·6% vs. non-aggressive suicidal behaviour and pain: 9·4-34·4%).41 Neither study accounted for other correlates.

Two studies examined the relationship between pain and death by suicide.44,48 One identified an increased risk for death by suicide (HR=1·6; 95%CI=[1·2-2·3]) in a community sample of adolescents with pain, compared to adolescents without pain (i.e., percentage of suicides: 20·4%; of which 6-62% reported pain vs. 32% without pain), which was no longer apparent after accounting for behavioural factors and psychiatric symptoms.48 Another large population-based cohort study explored the risk of death by suicide in opioid users with chronic non-cancer pain, showing that no deaths were recorded as suicides in this sample.44

Five studies explored longitudinal associations between pain and suicidality.33,34,36,44,48 Two found pain to be longitudinally associated with suicidal ideation, controlling for demographics, health-related factors and psychiatric symptoms,34,36 but only one of these measured and could thus control for suicidal ideation at baseline.36 Three studies explored the pain-suicidal behaviour association longitudinally.33,36,48 Pain was not found to predict suicidal behaviour over a one-year follow-up period,36 but pain predicted suicidal behaviour over a 33-year48, after controlling for demographics and psychiatric symptoms. Furthermore, pain was longitudinally associated with self-harm hospitalisation over a period of 12-years, controlling for demographics.33 However, as self-harm was not measured at baseline, no interferences can be drawn about the direction of this relationship.33 Finally, pain was not predictive of death by suicide after controlling for behavioural factors and psychiatric symptoms in two studies.44,48

One study showed that particularly comorbid pain, when three to five pain-sites were reported compared to fewer pain sites, increased the probability of suicidal ideation, after controlling for demographics and depression (aOR=1·8, 95%CI=[1·3-2·5]).47 Specifically, 19·6 percent of adolescents with three to five pain sites reported suicidal ideation compared to 7·5 percent of adolescents with one or two pain site and 4·5 percent of adolescents without pain.47 Four studies examined the relationship between pain frequency and suicidality.33,50,59,60 Of these, one study explored suicidal ideation, showing that more, compared to less, frequent pain, was significantly associated with suicidal ideation, after controlling for demographics and depression (aOR=1·7, 95%CI=[1·1-2·6]).59 Specifically, the prevalence of suicidal ideation increased from 7·8 percent, for pain lasting less than one day, to 26·2 percent, for pain lasting between seven to 14 days, (overall 8·5% reported suicidal ideation in this sample).59 Likewise, frequent pain was found to be associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour (OR=2·3-2·7),60 and future self-harm hospitalisation, compared to individuals with less frequent pains (aHR(sometimes/ often headaches/ stomach pain)=2·2).33 Specifically, 41·3 to 64·2 percent of adolescents with frequent pains, compared to 35·8 to 58·8 percent with seldom/ never pain, reported self-harm hospitalisation at follow-up.33 In keeping with these findings, recurrent pain was found to increase the odds of suicidal behaviour (aRR=1·4-1·8; recurrent pain: 6-20·5% with suicidal behaviour vs. no pain: 1·3-8·9% with suicidal behaviour), after controlling for demographics and psychiatric symptoms.50 However, when exploring this relationship more thoroughly focussing on varying frequencies of suicidal behaviour and pain, the pain-suicidal behaviour association only remained significant for very frequent pain and up to three episodes of suicidal behaviour per year (aRR=1·6, 95%CI=[1·1-2·2]), and for specific pain locations, after controlling for demographics and psychiatric symptoms (see table 2).50

Three studies explored pain severity as a risk factor for suicidality.48,52,53 One identified no association between severity and suicidal ideation after controlling for demographics and depression,52 and two found partial support for an association with suicidal behaviour in community samples.48,53

One study explored the relationship between pain duration and suicidal ideation in a clinical sample of pain patients, showing that the association between pain duration and suicidal ideation severity (aOR=1·0, 95%CI=[1·0-1·0]) was mediated by depression.52 Other pain characteristics (i.e., family history of pain disorders and pain intensity) were not associated with suicidal ideation in pain patients.42,52

Two studies explored the relationship between sensory (pain sensitivity and threshold) and affective (pain distress) components of the pain experience and suicidality in community samples.49,55 One study found significant group differences for pain distress, with higher levels being reported by adolescents with suicidal ideation (Med=40·5) compared to suicidal behaviour (Med=39·0) or healthy controls (Med=30·5).49 For pain sensitivity significant group differences only became apparent when comparing adolescents with suicidal behaviour to healthy controls (suicidal behaviour: M=6·6-2·3 vs. healthy: M=5·7-2·2).49,55 Moreover, higher pain tolerance was reported by adolescents with ideation and behaviour, compared to healthy controls, with no significant differences between the suicidal groups (suicidal ideation: M=1·83 (SD=0·95), suicidal behaviour: M=1·80 (SD=1·05), healthy: M=1·60 (SD=0·82).55

Lastly, six studies examined the association between physical disability and suicidality.35,42,46,51,52,59 In two community samples, the significant association between the amount of activities prevented by pain (aOR=2·0; 95%CI=[1·2-3·4]; suicidal ideation and some activities prevented by pain: 12·6% vs. no activities prevented: 3·5%),46 as well as headache-related disability and suicidal ideation (grade I disability=7·5% vs. grade IV=44·4% with suicidal ideation; p < 0·001) was no longer apparent after controlling for demographics, health-related factors and depression.46,59 Likewise, two clinical samples showed that functional disability was not associated with suicidal ideation in pain patients,52 and that functional disability and pain-bother did not differentiate between the presence of suicidal ideation in adolescents with and without chronic pain.42 Finally, the level of mobility limitations did not moderate the relationship between pain and suicidal ideation or suicidal behaviour, in a community-based study controlling for demographics.35 However, higher pain-related quality of life was significantly associated with lower levels of suicidality (aOR=0·97; 95%CI=[0·97-0·98]) in a community sample, after controlling for demographics.51

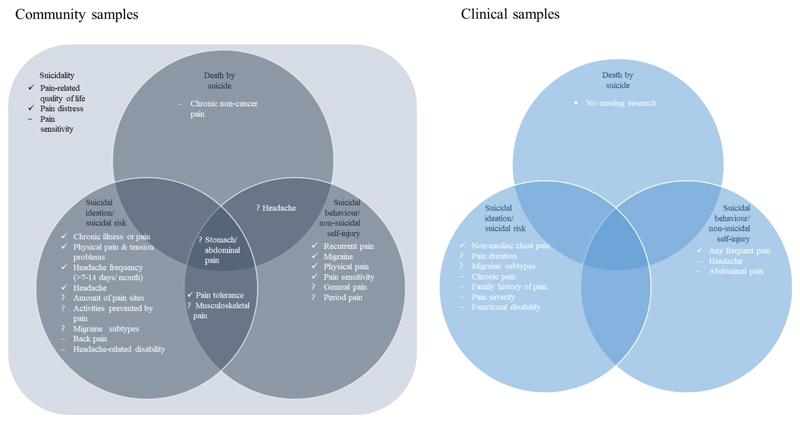

Figure 2 displays the results of this review, showing the different relationships between various manifestations of pain and suicidality in community and clinical samples of adolescents. Please note, that given the paucity of existing research and the large variety in the conceptualisation and measurement of each correlate, the evidence pertaining to specific correlates is rather limited and needs to be interpreted with caution (see supplement 4). Nevertheless, this systematic review has shown that the majority of studies reviewed provided support for the hypothesised pain-suicidality association in adolescence across the various manifestations of pain and suicidality, and the different samples being studied. Overall, we found higher prevalence rates of suicidality in community samples with pain compared to those without pain (suicidal ideation and pain: 7·6-17·7% vs. no pain: 3·6-6·2%; suicidal behaviour and pain: 6-63% vs. no pain: 1·3-39·2%), and in clinical samples (suicidal ideation and pain: 22% vs. no pain: 5·3%). Studies where the relationship was no longer apparent after control for other measured factors, were comparable to studies were this relationship remained in terms of their population, sample size and study designs, but those studies that provided only partial support generally explored more pain locations and types of suicidality, and controlled for more correlates, such as depression (n=9/11 vs. n=2/8, table 2). Across the different levels of support (full or partial support), similar associations have been found, namely around one- to two-fold increase in odds of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour, considering various pain locations. However, these associations became less robust and mostly reduced to non-significance after controlling for psychiatric symptoms (table 2).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the complex relationship between pain and suicidality in community and clinical sample of adolescents, respectively.

Note. The symbol ‘✓’ indicates correlates that were fully supported by existing research, the symbol ‘?’ shows correlates for which we found mixed findings (e.g., significance of the association depended on specific subtypes and the level of control for other factors e.g., depression; see also supplement 4 for an overview of an conditions under which this correlates were found to be significant), and the symbol ‘–’ indicates correlates that were not found to be related to suicidality. Please note, that given paucity of existing studies and the large variety in the conceptualisation and measurement of each correlate, the evidence pertaining to the specific correlates is rather limited.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesised and evaluated existing evidence across 25 studies, published between 2006 and 2018, on the hypothesised pain-suicidality association in adolescents. In keeping with our hypotheses derived from the adult literature,13,15,18,62 we found evidence for an association between pain and suicidality in adolescents, across various samples and manifestations of pain and suicidality. Overall, we found higher prevalence rates of suicidality in community samples with pain compared to those without pain (suicidal ideation and pain: 7·2-23·9% vs. no pain: 3·5-6·2%; suicidal behaviour and pain: 6-78% vs. no pain: 1·3-31·1%), and in clinical samples (suicidal ideation and pain: 22% vs. no pain: 5·3%). In other words, pain doubles the risk of suicidality, with some studies suggesting that pain may predict suicidality longitudinally. Substantial between-study heterogeneity in the operationalisation and assessment of exposures and outcomes, as well as in the population sampled, study designs used, and the degree of control for important correlates, led to inconsistent findings. These inconsistent findings are in keeping with research in adults,18,62 and highlight the need for a systematic and consistent approach in research that aims to disentangle the complex relationship between pain and suicidality.

Studies in which the pain-suicidality association became non-significant after controlling for other variables, typically assessed the exposure and outcomes with validated tools (e.g., instead of single-item, non-validated questions), explored different pain locations and types of suicidality, thereby also providing a range of non-significant associations, and more rigorously controlled for psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, than studies that provided full support for this relationship. In keeping with the adult literature (see Hooley et al.63; Spiegel et al.64), depression stood out as an important factor in the relationship between pain and suicidality, as the association weakened after controlling for depression (e.g., see Fuller-Thomson et al.46). Yet, this systematic review shows that, even after adjustment for depression, the pain-suicidality association still remained significant for subgroups that are characterised by more frequent and severe pains (e.g., headaches; see Koenig et al. 50; Hogstedt et al.48). This suggests that the relationship between pain and suicidality is complex, and at least partially depends on mechanisms other than depression (see Racine13). Additionally the cross-sectional nature of most studies means that research is still largely agnostic to the issue of whether depression acts as a confounder (increasing occurrence/reporting of both pain and suicidality), an intermediate mechanism (mediator) between pain and suicidality (e.g. pain > depression > suicidality), a moderator (e.g., the pain-suicidality association is stronger in the presence of co-morbid depression) or some complex interplay between these potential relationships. These proposed trajectories are consistent with a recent review, highlighting similar paths in which paediatric chronic pain and depression may co-occur and mutually maintain one another).65 However, little is known about which of these trajectories are more likely and the respective correlates that may drive these associations of paediatric pain with depression, or indeed with suicidality.65 Regarding suicidality, it is particularly relevant to explore these correlates to enhance our understanding of how changes in an initially adaptive state of acute pain may relate to maladaptive thoughts and behaviours. Feeling acute pain has a survival advantage, such that it signals harm and drives action to prevent future harm and promote recovery.66 However, when pain becomes chronic it loses this advantage and is associated with increased distress and at its worst self-destructive behaviours.66 In an attempt to better understand the complex pain-suicidality association in adults, a recent review has revealed psychological processes that are common to both conditions (e.g., psychological flexibility, future orientation and mental imagery).67 However, it remains unknown whether these psychological processes may also drive the behavioural change that may explain the pain-suicidality relationship in adolescence. It is, therefore, essential to better understand the pain-suicidality trajectories and the potentially complex interplay with unique correlates in adolescence to identify these vulnerable youth.

Research in adults shows that common mental-health factors (e.g., depression and anxiety) mediate but do not fully account for the pain-suicidality association.68–70 As pain and psychiatric symptoms are highly comorbid during adolescence,71 it is crucial to better understand the potentially complex interplay between physical and mental health when explaining the pain-suicidality association. To date, most studies have solely explored depression as a mental health factor underpinning the pain-suicidality association in adolescence, and little attention has been given to other potential mental health factors, such as anxiety or childhood trauma (see Spiegel et al.64), or psychological processes underpinning this association. Enhanced knowledge about and management of comorbid physical and mental-health risk factors may maximise treatment outcomes.72

Exploring different aspects of the pain experience, we found that more pain sites, frequent and recurrent pain and pain-related quality of life (i.e., people’s perceived impact of their pain on their physical, mental and social well-being51), were associated with suicidality, which corroborates and extends existing research in adults.13 In addition, longer pain duration was associated with suicidal ideation. In keeping with the adult literature, this relationship diminished after controlling for depression, suggesting that over time suicidal ideation may become more closely associated with comorbid psychological symptoms instead of the duration of the physical symptoms.13 There are mixed findings for relationships with pain severity, pain sensitivity, distress and tolerance. Although physical disability has previously been found to be a predictor of suicidality in adult samples,62 the current review detected inconsistent findings in adolescents. Even though some studies detected an association (see Lewcun et al.52), this relationship mostly diminished to non-significance, after controlling for psychiatric symptoms (see Fuller-Thomson et al.46). This finding is in keeping with research suggesting that the correlates of physical disability differ by age.73 Specifically, physical disability was strongly associated with affective distress in younger patients, compared to elderly were physical disability was strongly associated with pain severity.73 This finding suggests that in young people the association between physical disability and suicidality may be more strongly driven by the comorbid psychiatric symptoms than in older adults. That is, physical disability may increase suicidal vulnerability through its effect on mental health (e.g., emotional suffering13), or mental health problems may impact physical health and physical disability (e.g., due to fatigue, reduced activity or sleeping difficulties), leading to increased suicidal vulnerability. As most research to date is cross-sectional, the direction of the effects awaits further scrutiny. Furthermore, other aspects of the pain experience, namely family history of pain, pain intensity and opioid-use, were not found to be associated with suicidality in adolescents. As research on the relationship between aspects of the pain experience and suicidality in adolescence is very limited, mixed results, particularly when performing a range of subgroup analyses, may be attributable to a lack of power when exploring subgroups, adding moderators and controlling for various correlates. Hence, a systematic exploration of these factors and replication of existing research is warranted.

Research on the relationship between pain and suicidality during adolescence is emerging, with 18 studies that addressed the adolescent years specifically. However, the amount of evidence pertaining to the specific aspects of the pain experience that may exacerbate suicidal risk is rather limited and inconclusive (see supplement 5), which emphasizes the need for future research. Specifically, future research needs to address the above mentioned limitations by thoroughly assessing pain and suicidality, controlling for correlates other than depression, exploring aspects of the pain experience (e.g., pain frequency) and risk and resilience factors underpinning this link more thoroughly across samples and study designs to elucidate under which conditions pain may be associated with suicidality during adolescence. As most research has been conducted with community samples, future research needs to explore how these findings translate to clinical samples of adolescents in pain. Most of the reviewed research aligns with findings from similar studies in adults, which suggest a two- to three-times increased risk of suicidality in adults with chronic pain (see Racine13), compared to the doubled risk identified here. This challenges the proposed developmental profile underlying the pain-suicidality association, although the presence of a similar associations may hide different underlying mechanisms. Research to date has explored the pain-suicidality association in adolescence based on hypotheses derived from the emerging research in adults without acknowledging and exploring potential developmental differences between adolescents and adults. Moreover, as the current systematic review elucidates, the existing literature is limited by the superficial exploration of the pain-suicidality association in adolescents, mainly focussing on the overall relationship rather than specific pain characteristics. This superficial investigation may hide developmental differences that may become apparent when considering different lifetime periods and aspects of the pain experience. Chronic pain is a stressful experience that is frequently perceived as uncontrollable and functionally impairing.74 Hence, exposure to chronic pain during the sensitive adolescent period75 may interfere with adaptive neuro-cognitive development (e.g., acquisition of self-regulatory skills) and social maturation (e.g., independence), making adolescents more susceptible to prolonged emotional difficulties and at its worst suicidality.28,75 However at the same time, adolescents are shielded from some of the harsher socioeconomic effects of chronic disabling pain that may be experienced in adulthood (e.g., inability to work), and they are likely to be living in a social context which provides support for daily tasks. These highly speculative hypotheses await further scrutiny, and a systematic exploration of developmental similarities and differences underpinning the pain-suicidality association in adolescents and adults is warranted to tailor early interventions to patients’ needs.

There are several limitations pertaining to the current systematic review. First, as we focused on literature published in English, we cannot generalise these findings to research published in any other language. Second, the direction of the effects between pain and suicidality remains unclear, given the small number of cohort studies that allow a consideration of direction of causality in observed associations. In addition, the existing cohort studies were limited by the single assessment of the outcome at follow-up, which precludes conclusions to be drawn about the direction of the effects. By assessing pain and suicidality at multiple times throughout development, future studies should ideally enable stronger statements to be made concerning the likely direction of effects. Third, the identified support for the pain-suicidality association during adolescence may be due to publication bias (see also supplement 4), which we were unable to formally test, because of the large between-study heterogeneity that precludes the use of forest plots as part of a meta-analysis. Finally the findings are limited by the covariates used in existing studies (mostly depression), and it is unclear whether other unmeasured and uncontrolled factors could fully or partially explain the pain-suicidality association during adolescence.

Despite these limitations, this is the first review that systematically explored the relationship between pain and suicidality during the critical years of adolescence – a distinct developmental period with marked increases in the report of pain22 and suicidality.6,7 This review is characterised by methodological rigor, including double data search, eligibility and quality assessments, and data extraction with substantial inter-rater reliability. Moreover, unpublished subsample data has been obtained for seven studies. Across studies, we found evidence to suggest that adolescents suffering from pain are at an increased risk of suicidal ideation and behaviour. Although depression was identified as an important factor in this association, the pain-suicidality association could not be fully explained by the presence of comorbid depression. Evidence on associations between pain characteristics and suicidality is sparse and inconclusive, potentially hiding developmental differences. Interventions are warranted that target key psychological mechanisms underpinning the pain-suicidality association in adolescence to prevent or intervene with the progression along the suicide spectrum in adolescents suffering from pain. In addition, routine screening for suicidal risk needs to be facilitated to provide timely help and support.

Supplementary Material

Panel: Key Messages.

Leading suicide theories and research in adults suggest that pain may exacerbate an individual’s suicidal risk. Although pain and suicidality both increase in prevalence during adolescence, their relationship remains unclear.

Across various manifestations of pain and suicidality, we found that pain approximately doubles the risk of suicidality in community samples (suicidal ideation and pain: 7·2-23·9% vs. no pain: 3·5-6·2%; suicidal behaviour and pain: 6-78% vs. no pain: 1·3-31·1%) and clinical samples (suicidal ideation and pain: 22% vs. no pain: 5·3%) of adolescents.

Although depression was found to play an important role in this association, the pain-suicidality association cannot solely be explained by the presence of comorbid depression. Furthermore, we identified a small number of studies that explored and found inconsistent evidence for associations between pain characteristics and suicidality.

By identifying a final sample of 25 studies, this review further underscores the paucity of research with adolescents. In addition, the existing studies were limited by the assessment of pain and suicidality (e.g., single-item questions) and the degree of control for other correlates. Future research needs to address these limitations by thoroughly assessing pain and suicidality, controlling for correlates other than depression, as well as exploring aspects of the pain experience (e.g., pain frequency) and risk and resilience factors underpinning this link more thoroughly across samples and study designs. These studies may build on, but should not be restricted to, factors identified in the adult literature, in order to allow for a systematic exploration of potential developmental differences.

These findings have important clinical implications, such that interventions need to be developed that target key psychological mechanisms underpinning the pain-suicidality link in adolescence to prevent or intervene with the progression along the suicide spectrum in adolescents with pain. In addition, routine screening for suicidal risk needs to be facilitated in order to provide timely help and support.

Acknowledgements

This review was partially funded by the Oskar-Helene-Heim foundation, the FAZIT foundation, the Wellcome Trust, Grant Number 107496/Z/14/Z, the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo, and the Defehr-Neumann foundation. No other funding sources apply. We would like to thank all authors who shared their publications and made subsample data available. In addition, we would wish to gratefully thank the following people for their invaluable support: Ms Eli Harriss and Ms Karine Barker (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford) for their help in identifying all the existing literature on this topic; Professor Andrea Cipriani for his advice and comments on the study protocol; and Professor Keith Hawton for his advice and suggestions on the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors

VH, BG, and CC designed this study. VH, BG, CC, and TF reviewed the registered protocol. VH coordinated and performed the data searches, study selection, data extraction and quality assessments. LQ acted as second independent reviewer, performing the second data searches, study selection, and quality assessments. RB acted as second independent reviewer, performing the data extraction. BG oversaw the implementation and acted as a third independent reviewer to resolve conflicts. VH wrote the initial draft and RB checked the tables and numbers for accuracy. VH, BG, CC and TF contributed to revising the initial draft, leading to the final manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Declaration of Interests

We declare no competing interests.

Data Sharing

The corresponding study protocol and the EndNote libraries will be made available on the Open Science Framework at the time of publication (see https://osf.io/; project name: Pain and Suicidality in Adolescence).

References

- 1.Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyner SM, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009;374:881–892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. Suicide. [accessed May 09, 2019];2018 Aug 24; https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- 3.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K, Psychol C, Deeks J. The prevalence of suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:239–250. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawton K, Saunders KEA, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, et al. Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. The BMJ. 2017;359 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klonsky ED, May AM. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: A critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:1–5. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Boston: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klonsky ED, May AM. The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “Ideation-to-Action” Framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2015;8:114–129. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor RC, Kirtley OJ. The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373:e20170268. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Racine M. Chronic pain and suicide risk: A comprehensive review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizvi SJ, Iskric A, Calati R, Courtet P. Psychological and physical pain as predictors of suicide risk: Evidence from clinical and neuroimaging findings. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30:159–167. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang NKY, Crane C. Suicidality in chronic pain: a review of the prevalence, risk factors and psychological links. Psychol Med. 2006;36:575–586. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price DD. Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science. 2000;288:1769–1772. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treede RD, Kenshalo DR, Gracely RH, Jones AKP. The cortical representation of pain. Pain. 1999;79:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calati R, Laglaoui Bakhiyi C, Artero S, Ilgen M, Courtet P. The impact of physical pain on suicidal thoughts and behaviors: Meta-analyses. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;71:16–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grichnik KP, Ferrante FM. The difference between acute and chronic pain. Mt Sinai J Med. 1991;58:217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merskey H, Bogduk N, International Association for the Study of Pain . Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: A systematic review. Pain. 2011;152:2729–2738. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin AL, McGrath PA, Brown SC, Katz C. Children with chronic pain: Impact of sex and age on long-term outcomes. Pain. 2007;128:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organisation. Age-Not the whole story. [accessed March 5, 2018];2014 http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page2/age-not-the-whole-story.html.

- 24.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:6–20. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brattberg G. Do pain problems in young school children persist into early adulthood? A 13-year follow-up. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Rosenberg C. Chronic pain in a geographically defined general population: studies of differences in age, gender, social class, and pain localization. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:174–182. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anastas T, Colpitts K, Ziadni M, Darnall BD, Wilson AC. Characterizing chronic pain in late adolescence and early adulthood: prescription opioids, marijuana use, obesity, and predictors for greater pain interference. PAIN Reports. 2018;3 doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blakemore SJ, Mills KL. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neeleman J. Suicide as a crime in the UK: legal history, international comparisons and present implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:252–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation; Melbourne, Australia: Available at www.covidence.org. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Junker A, Bjørngaard JH, Bjerkeset O. Adolescent health and subsequent risk of self-harm hospitalisation: a 15-year follow-up of the Young-HUNT cohort. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2017;11 doi: 10.1186/s13034-017-0161-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strandheim A, Bjerkeset O, Gunnell D, Bjornelv S, Holmen TL, Bentzen N. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts in adolescence--a prospective cohort study: the Young-HUNT study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005867. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alriksson-Schmidt AI. Depressive symptomatology and suicide attempts in adolescents with mobility limitations. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B. The Sciences and Engineering. 2008;68(11–B):7688. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Tilburg MA, Spence NJ, Whitehead WE, Bangdiwala S, Goldston DB. Chronic pain in adolescents is associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Pain. 2011;12:1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [accessed February 15, 2018];2018 http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 38.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. updated March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seehra J, Pandis N, Kolestsi D, Fleming PS. Use of quality assessment tools in systematic reviews was varied and inconsistent. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons,Ltd; 2009. Chapter 40: When Does it Make Sense to Perform a Meta-Analysis; pp. 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bayramoglu A, Saritemur M, Akgol Gur ST, Emet M. Demographic and clinical differences of aggressive and non-aggressive suicide attempts in the emergency department in the eastern region of turkey. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17:1–6. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.24666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bromberg MH, Law EF, Palermo TM. Suicidal ideation in adolescents with and without chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:21–27. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell G, Darke S, Bruno R, Degenhardt L. The prevalence and correlates of chronic pain and suicidality in a nationally representative sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:803–811. doi: 10.1177/0004867415569795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ekholm O, Kurita GP, Hojsted J, Juel K, Sjogren P. Chronic pain, opioid prescriptions, and mortality in Denmark: A population-based cohort study. Pain. 2014;155:2486–2490. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eliacik K, Kanik A, Bolat N, et al. Anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and stressful life events in non-cardiac adolescent chest pain: a comparative study about the hidden part of the iceberg. Cardiol Young. 2017;27:1098–1103. doi: 10.1017/S1047951116002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fuller-Thomson E, Hamelin GP, Granger SJR. Suicidal ideation in a population-based sample of adolescents: Implications for family medicine practice. ISRN Family Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.5402/2013/282378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halvorsen JA, Dalgard F, Thoresen M, Bjertness E, Lien L. Itch and pain in adolescents are associated with suicidal ideation: a population-based cross-sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:543–546. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hogstedt C, Forsell Y, Hemmingsson T, Lundberg I, Lundin A. Psychological symptoms in late adolescence and long-term risk of suicide and suicide attempt. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48:315–327. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirtley OJ, O'Connor RC, O'Carroll RE. Hurting inside and out? Emotional and physical pain in self-harm ideation and enactment. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2015;8:156–171. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koenig J, Oelkers-Ax R, Parzer P, et al. The association of self-injurious behaviour and suicide attempts with recurrent idiopathic pain in adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee PH, Yeh YC, Hsiao RC, Yen CF, Hu HF. Pain-related quality of life related to mental health and sociodemographic indicators in adolescents. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2017;44:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewcun B, Kennedy TM, Tress J, Miller KS, Sherker J, Sherry DD. Predicting suicidal ideation in adolescents with chronic amplified pain: The roles of depression and pain duration. Psychol Serv. 2018;15:309–315. doi: 10.1037/ser0000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X, Liu ZZ, Fan F, Jia CX. Menarche and menstrual problems are associated with non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21:649–656. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0861-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park SP, Seo JG, Lee WK. Osmophobia and allodynia are critical factors for suicidality in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0529-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ren Y, You J, Zhang X, et al. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: The role of capability for suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2019;23:64–81. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2018.1426507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rozen TD, Fishman RS. Cluster headache in the United States of America: demographics, clinical characteristics, triggers, suicidality, and personal burden. Headache. 2012;52:99–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]