Abstract

Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is a serious microbe causing dental caries. Mutacin IV is an effective bacteriocin produced by S. mutans to antagonize numerous non-mutans streptococcal species. However, the posttranscriptional regulation of mutacin IV remains unclear. This study aimed to analyze the effect of small RNA srn225147 on mutacin IV. The functional prediction suggested that srn225147 is involved in the production of mutacin IV, an important secondary metabolite. According to RNAhybrid and RNAPredator prediction, the mutacin IV formation-associated gene comD is a target of srn225147. We further analyzed the roles of srn225147 and comD in 20 S. mutans clinical strains with high production of mutacin IV (High-IV group) and lacking mutacin IV (None-IV group). Levels of comD expression were significantly higher in the High-IV group, whereas the Non-IV group showed relatively higher expression of srn225147, with a negative correlation observed between srn225147 and comD. Moreover, compared to the mimic negative control (NC) group, comD expression was decreased at 400-fold srn225147 overexpression but increased at approximately 1400-fold overexpression. Although the production of mutacin IV in the 1400-fold change srn225147 mimic group was larger than that in the 400-fold change mimic group, there was no significant difference in the production of mutacin IV between the srn225147 mimic group and mimic NC group. These results indicate that srn225147 has a two-way regulation effect on the expression of comD but that its regulation in the production of mutacin IV is weak.

Keywords: Streptococcus mutans, Mutacin, Small RNA, comD

Introduction

Dental caries is one of the most common chronic infectious disease affecting physical and mental health and remains a serious public health challenge worldwide [1–3]. According to the findings of the 4th National oral health survey, the prevalence of dental caries in elderly individuals in China is as high as 98.0% [4]. Therefore, the prevention of dental caries in China is of great importance.

Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is a crucial microbe causing dental caries [5–7]. S. mutans can adhere to tooth surface, promote the formation of biofilm, and induce acid production, leading to the demineralization of tooth surfaces and the onset of dental caries [8]. S. mutans tooth surface adherence is a prerequisite for cariogenicity. Streptococcus gordonii (S. gordonii) is a commensal bacterium colonizing human dental plaques that is negatively associated with dental caries [9, 10]. Antagonism of the growth of S. mutans via hydrogen peroxide and the balance of the acidic environment caused by S. mutans via ammonia release is key for S. gordonii to prevent dental caries [11–13]. Mutacin IV is an effective bacteriocin produced by S. mutans to antagonize the growth of S. gordonii [14].

An increasing number of studies have shown that small RNAs (sRNAs) are important regulators in bacteria at the posttranscriptional level [15, 16]. sRNAs regulate the virulence of bacteria under different stresses by base-pairing with target mRNAs to regulate expression [17]. A host of sRNAs have been identified in bacteria [18]. Recent studies have reported sRNAs expression in S. mutans under various stresses, which may involve virulence regulation. For example, more than 900 potential sRNAs were identified in S. mutans under normal conditions, followed by the detection of sRNA L10-Leader in different growth phases [19, 20]. Moreover, according to our previous studies, specific sRNAs were induced in S. mutans under different sucrose concentrations and pH stress [21, 22].

sRNA srn225147 was reported in our previous study (page 28 of Supplementary material) [21], and according to the results of bioinformatics analysis, might be involved in the production of mutacin IV. Here, we aim to investigate the function of srn225147 in the production of mutacin IV.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatics Analysis

RNAhybrid and RNAPredator (http://nibiru.tbi.univie.ac.at/RNApredator/introduction.html) were used to predict target mRNAs of srn225147 [23]. The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) gene annotation tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) and antiSMASH bacterial version (https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/) were employed for determining Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways associated with srn225147 [24, 25].

Detection of Mutacin IV and Expression Levels of comD, nlmA, nlmB and srn225147 in S. mutans Strains

S. mutans clinical isolates with high production of mutacin IV (n = 10, High-IV group) and lacking mutacin IV (n = 10, None-IV group) were selected. Production of mutacin IV was evaluated by bacteriocin assay described previously with minor modifications [11]. S. gordonii (ATCC 10558) was used as the indicator strain to evaluate mutacin IV activity. Each clinical S. mutans isolate was grown overnight in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and then adjusted OD600 nm to 0.3. Ten microliters (μL) of each isolate was then added to BHI agar and cultured for 12 h, followed by inoculation of equal amounts of the indicator strain adjacent to the S. mutans isolate. Zones of indicator strain clearing after incubation for an additional 12 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2 represent mutacin IV activity.

Bacteria were cultured overnight in BHI broth, and the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, German) was used for total bacterial RNA extraction. Mir-X™ miRNA First Strand Synthesis Kit (Takara, Japan) and Mir-X™ miRNA qRT-PCR TB Green™ Kit (Takara, Japan) was used for reverse-transcript PCR and RT-qPCR of srn225147, respectively. The PCR reaction conditions of srn225147 included 95 °C for 10 s and 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 20 s of annealing at 55 °C. The expression level of 16S rRNA was used for standardization. The 16S rRNA, comD, nlmA, and nlmB primers were synthesized according to previous studies [26, 27]. The correlation between srn225147 and target mRNA comD in the 20 isolates was assessed.

The Effect of srn225147 on comD

Electroporation was carried out according to Choi et al., with minor modifications [28]. GenePharma (Shanghai, China) helped to design and synthesize the srn225147 mimic and negative control (NC). S. mutans UA159 was cultured overnight in 1000 μL BHI broth (volume ratio 1:100) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. And then washed twice with 0.9% saline, and resuspended in fresh BHI broth. For electroporation, a 40-μL aliquot of the sample was transferred to a pre-chilled 1-mm electroporation cuvette (BTX, USA), and 8 μL of srn225147 mimic diluted with 250 μL RNase-free or 10 μL of srn225147 inhibitor diluted with 625 ul RNase-free was added. Electroporation was performed using an ECM630 (BTX, USA) by applying a single pulse of 2.5 kV, capacitance at 25 μF, and resistance at 200 Ω. The bacteria were cultured in fresh BHI broth for 8 h after electroporation, and total RNA was extracted and purified. The reverse-transcription PCR was done and the cDNA was used for RT-qPCR to evaluate the effect of srn225147 on the expression of comD.

Primer sequences are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| ID | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

| srn225147 | ATTGACTTTGAGTCTGTGC |

| comD (F) | CTCTGATTGACCATTCTTCTGG |

| comD (R) | CATTCTGAGTTTATGCCCCTC |

| nlmA (F) | AATGGACAGCCAAACACTTTC |

| nlmA (R) | TAACAAGAGTCGCACCTGCC |

| nlmB (F) | TGTCAGAAGTTTTTGGTGG |

| nlmB (R) | ACTCCAGCACATCCAGCAAG |

| 16S rRNA (F) | CTTACCAGGTCTTGACATCCCG |

| 16S rRNA (R) | ACCCAACATCTCACGACACGAG |

Statistics

T tests were used for quantitative data., and Spearman-rank correlation coefficients were used to evaluate correlations by IBM SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). p < 0.05 was the significance threshold.

Results and Discussion

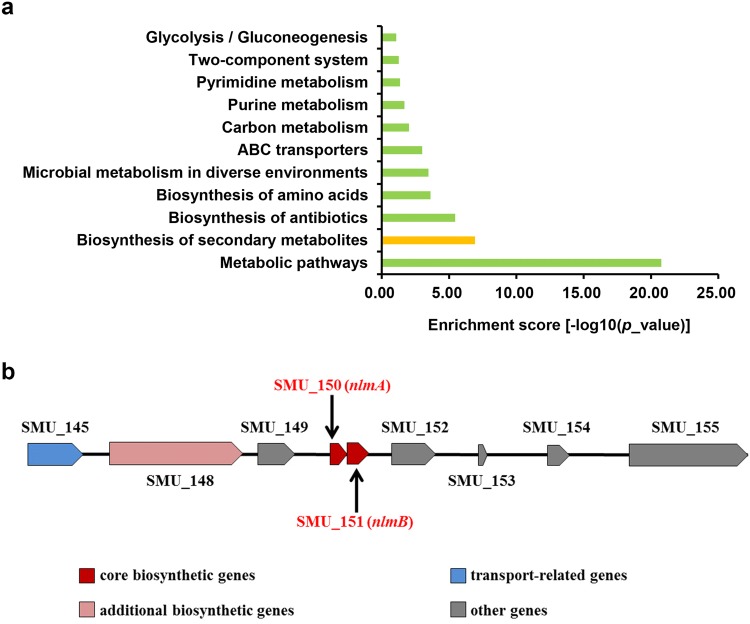

Functional Prediction of srn225147

According to KEGG analysis, srn225147 participates in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (Fig. 1a), and mutacin IV is a core secondary metabolite according to antiSMASH (bacterial version) (Table 2 and Fig. 1b). RNAhybrid and RNAPredator showed that the reported mutacin IV-associated genes comD is a candidate target for srn225147 (Table 3). Competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) and ComDE two-component signal transduction pathway play key roles in the synthesis of mutacin IV [29], whereby S. mutans produces CSP, and ComD, a membrane-associated histidine kinase encoded by comD, senses the signal once the extracellular CSP concentration has reached a certain threshold. ComD is becomes autophosphorylated and then ComE, which regulates cytoplasmic responses, is in turn phosphorylated. Activated ComE then drives nlmA and nlmB expression and the production of mutacin IV [30]. Thus, we speculated that srn225147 is involved in the production of mutacin IV by regulating comD expression.

Fig. 1.

Functional analysis of srn225147a according to KEGG, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites is one of the important pathways involving srn225147, b according to antiSMASH cluster 1, the gene encoding mutacin IV is a core component of secondary metabolite production

Table 2.

The secondary metabolites of S. mutans analyzed by antiSMASH

| Cluster | Type | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Bacteriocin | 148,813 | 148,813 |

| Cluster 2 | Bacteriocin | 264,323 | 292,670 |

| Cluster 3 | Bacteriocin | 391,531 | 401,761 |

| Cluster 4 | Nrps | 1,239,790 | 1,307,561 |

| Cluster 5 | Bacteriocin | 1,768,449 | 1,799,741 |

Table 3.

comD is the putative target for srn225147 analyzed by RNAhybrid and RNAPredator

| Software | Energy (Kcal/mol) | Position (start–end) | Interaction (5′ → 3′) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| comD | srn225147 | comD | srn225147 | ||

| RNAhybrid | − 20.30 | 685–714 | 2–17 | GCUCAGAUUCGAAAUAUCACCCAGUAUAGUCAGC | UUGACUUUGAGUCUGU |

| RNAPredator | − 10.93 | 682–694 | 7–19 | GCUCAGAUUCGAA | UUGAGUCUGUGC |

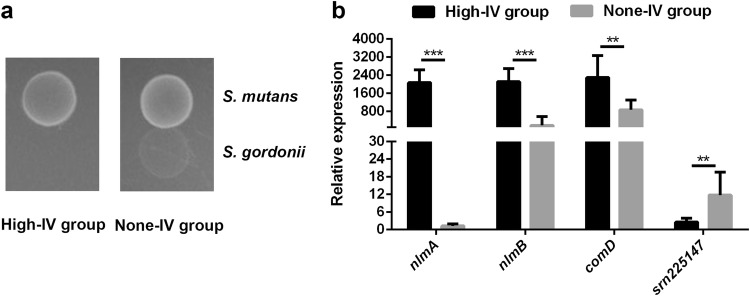

Differential Expression Level of comD, nlmA, nlmB and srn225147 in S. mutans Clinical Isolates

Bacteriocins, antibacterial peptides synthesized by bacteria, are produced by bacteria to compete in an ecological niche, providing a growth advantage [31]. Mutacin IV, encoded by nlmA and nlmB in S. mutans, is active against numerous non-mutans streptococcal species including S. gordonii, S. sobrinus, and S. cricetid [32, 33]. However, the posttranscriptional regulation of mutacin IV is still unknown. Here, we disclose the role of sRNA in mutacin IV production for the first time. Previous studies have indicated that sRNA may be a potential biomarker for evaluating the status and severity of clinical diseases. For example, expression of sRNAs in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) differs between clinical strains isolated from patients with septic shock and colonization [34]. Expression of sRNAs in S. aureus varies widely in patients with abscesses and is more homogeneous in patients with cystic fibrosis and highly uniform in nasal carriers [35]. sRNAs were also been reported in S. mutans [19–22, 36]. Accordingly, we assessed the expression levels of srn225147 and comD in 20 selected clinical isolates with high production of mutacin IV (High-IV group, n = 10) and lacking mutacin IV (None-IV group, n = 10) firstly (Fig. 2a). By promoting polysaccharide-dependent biofilm formation in S. mutans, sucrose is taken as the major cariogenic carbohydrate [37]. A previous study reported that S. mutans clinical isolates exhibit different virulences under sucrose stress [38]. Considering that differences in sucrose utilization and sucrose-induced virulence among clinical strains are unclear, this study aimed to explore the effect of srn225147 on mutacin IV; as expression of srn225147 can be detected without sucrose, we did not analyze the effect of the addition of sucrose on the expression level of srn225147 and subsequently on comD in clinical isolates. To exclude possible effects caused by sucrose and in line with the clinical nature of the isolates, sucrose was not added in our analysis of the regulation of comD and mutacin IV by srn225147 in S. mutans UA159. The results showed that the expression levels of nlmA, nlmB, and comD were significantly greater in High-IV group than in the None-IV group (p < 0.001 for nlmA and nlmB, and p = 0.001 for comD). Conversely, the None-IV group displayed a relatively higher level of srn225147 expression compared to the High-IV group (p = 0.005) (Fig. 2b). These results indicate that srn225147 might play an important role in mutacin IV.

Fig. 2.

Expression of srn225147 and mRNAs related to mutacin IV between High-IV group and None-IV group a production of mutacin IV in the High-IV group and None-IV group, b expression levels of nlmA, nlmB, comD, and srn225147 between the High-IV group and None-IV group

Regulation of comD and Mutacin IV by srn225147

A negative correlation was observed between srn225147 and comD according to expression levels in clinical isolates (r = − 0.465, p = 0.039, Fig. 3a). S. mutans UA159 with up- and downregulation of srn225147 was successfully constructed (p < 0.001 for the 1400-fold change group and p = 0.016 for the 400-fold change group). The expression level of comD decreased when the expression of srn225147 reached approximately 400-fold compared to the mimic NC group (p = 0.019); however, the expression level of comD increased when the expression of srn225147 reached approximately 1400-fold compared to the mimic NC group (p = 0.002, Fig. 3b and c). The average of inhibition zones and standard deviation (mm) of the four group (srn225147 mimic NC corresponding to the 400-fold change group, srn225147 mimic group with 400-fold change, srn225147 mimic NC corresponding to the 1400-fold change group, and srn225147 mimic group with 1400-fold change) were 2.20 ± 0.05, 2.16 ± 0.02, 2.31 ± 0.01, and 2.30 ± 0.02 mm, respectively. The inhibition zone did not differ significantly between the groups of srn225147 mimic and mimic NC (p > 0.05, Fig. 3d). The inhibition zone of srn225147 mimic group with a 1400-fold change was larger than that of the srn225147 mimic group with a 400-fold change (p = 0.006). These results suggest that the comD expression can be regulated by srn225147 but that the effect of srn225147 on mutacin IV is weak. We only focused on srn225147 in this study, yet other sRNAs may play a crucial role in mutacin IV regulation by controlling genes related to the ComDE pathway, which needs to be explored in the future.

Fig. 3.

Effect of srn225147 on the level of comD and mutacin IV a correlation between srn225147 and comD according to expression levels in 20 clinical isolates, b, c effect of srn225147 on the expression level of comD, d effect of srn225147 on the production of mutacin IV

In conclusion, our study provides a new insight into the production of mutacin IV in S. mutans at the posttranscriptional level, and our results suggest that srn225147 has a two-way regulatory effect on comD expression. However, srn225147-mediated regulation of mutacin IV production is weak. Future studies on more sRNAs associated with mutacin IV are needed.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Natural Science Fund of Education Department of Anhui province, China (Grant Number KJ2018A0223) and the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of Anhui province, China (2016–40).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were consistent with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of (2017) KY011 from the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yu Sun, Phone: +86-552-3086-336, Email: nagatoD621@163.com.

Kai Zhang, Phone: +86-552-3175242, Email: zhangkai29788@163.com.

References

- 1.Petti S. Elder neglect—oral diseases and injuries. Oral Dis. 2018;24:891–899. doi: 10.1111/odi.12797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passos-Soares JS, Santos LPS, Cruz SSD, Trindade SC, Cerqueira EMM, Santos KOB, Balinha I, Silva I, Freitas TOB, Miranda SS, et al. The impact of caries in combination with periodontitis on oral health-related quality of life in Bahia, Brazil. J Periodontol. 2018;89:1407–1417. doi: 10.1002/JPER.18-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiwari T, Jamieson L, Broughton J, Lawrence HP, Batliner TS, Arantes R, Albino J. Reducing indigenous oral health inequalities: a review from 5 nations. J Dent Res. 2018;97:869–877. doi: 10.1177/0022034518763605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao YB, Hu T, Zhou XD, Shao R, Cheng R, Wang GS, Yang YM, Li X, Yuan B, Xu T, et al. Dental caries in Chinese elderly people: findings from the 4th national oral health survey. Chin J Dent Res. 2018;21:213–220. doi: 10.3290/j.cjdr.a41077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moye ZD, Zeng L, Burne RA. Fueling the caries process: carbohydrate metabolism and gene regulation by Streptococcus mutans. J Oral Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.3402/jom.v6.24878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur G, Rajesh S, Princy SA. Plausible drug targets in the Streptococcus mutans Quorum sensing pathways to combat dental biofilms and associated risks. Indian J Microbiol. 2015;55:349–356. doi: 10.1007/s12088-015-0534-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandes RA, Monteiro DR, Arias LS, Fernandes GL, Delbem ACB, Barbosa DB. Virulence factors in Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans biofilms mediated by farnesol. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58:138–145. doi: 10.1007/s12088-018-0714-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen ZT, Scott-Anne K, Liao S, De A, Luo M, Kovacs C, Narvaez BS, Faustoferri RC, Yu Q, Taylor CM, et al. Deficiency of BrpA in Streptococcus mutans reduces virulence in rat caries model. Molecular oral microbiology. 2018;33:353–363. doi: 10.1111/omi.12230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao Y, Zhou Y, Ouyang Y, Lin HC. Association of oral streptococci community dynamics with severe early childhood caries as assessed by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis targeting the rnpB gene. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:936–945. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agnello M, Marques J, Cen L, Mittermuller B, Huang A, Chaichanasakul Tran N, Shi W, He X, Schroth RJ. Microbiome associated with severe caries in Canadian first nations children. J Dent Res. 2017;96:1378–1385. doi: 10.1177/0022034517718819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang X, Browngardt CM, Jiang M, Ahn SJ, Burne RA, Nascimento MM. Diversity in antagonistic interactions between commensal oral streptococci and Streptococcus mutans. Caries Res. 2018;52:88–101. doi: 10.1159/000479091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang X, Palmer SR, Ahn SJ, Richards VP, Williams ML, Nascimento MM, Burne RA. A highly arginolytic Streptococcus species that potently antagonizes Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:2187–2201. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03887-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fakhruddin KS, Ngo HC, Samaranayake LP. Cariogenic microbiome and microbiota of the early primary dentition: a contemporary overview. Oral Dis. 2019;25:982–995. doi: 10.1111/odi.12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossain MS, Biswas I. An extracelluar protease, SepM, generates functional competence-stimulating peptide in Streptococcus mutans UA159. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:5886–5896. doi: 10.1128/jb.01381-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nitzan M, Rehani R, Margalit H. Integration of bacterial small RNAs in regulatory networks. Annu Rev Biophys. 2017;46:131–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-034058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meibom KL, Cabello EM, Bernier-Latmani R. The small RNA RyhB is a regulator of cytochrome expression in Shewanella oneidensis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:268. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djapgne L, Panja S, Brewer LK, Gans JH, Kane MA, Woodson SA, Oglesby-Sherrouse AG. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PrrF1 and PrrF2 small regulatory RNAs promote 2-alkyl-4-quinolone production through redundant regulation of the antR mRNA. J Bacteriol. 2018;200:e00704–e00717. doi: 10.1128/JB.00704-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutta T, Srivastava S. Small RNA-mediated regulation in bacteria: a growing palette of diverse mechanisms. Gene. 2018;656:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HJ, Hong SH. Analysis of microRNA-size, small RNAs in Streptococcus mutans by deep sequencing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;326:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia L, Xia W, Li S, Li W, Liu J, Ding H, Li J, Li H, Chen Y, Su X, et al. Identification and expression of small non-coding RNA, L10-leader, in different growth phases of Streptococcus mutans. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012;22:177–186. doi: 10.1089/nat.2011.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu SS, Zhu WH, Zhi QH, Liu J, Wang Y, Lin HC. Analysis of sucrose-induced small RNAs in Streptococcus mutans in the presence of different sucrose concentrations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:5739–5748. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Tao Y, Yu L, Zhuang P, Zhi Q, Zhou Y, Lin H. Analysis of small RNAs in Streptococcus mutans under acid stress—a new insight for caries research. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1529. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eggenhofer F, Tafer H, Stadler PF, Hofacker IL. RNApredator: fast accessibility-based prediction of sRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W149–W154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blin K, Pascal Andreu V, de Los Santos ELC, Del Carratore F, Lee SY, Medema MH, Weber T. The antiSMASH database version 2: a comprehensive resource on secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D625–D630. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senadheera DB, Cordova M, Ayala EA, Chavez de Paz LE, Singh K, Downey JS, Svensater G, Goodman SD, Cvitkovitch DG. Regulation of bacteriocin production and cell death by the VicRK signaling system in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:1307–1316. doi: 10.1128/JB.06071-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh K, Senadheera DB, Levesque CM, Cvitkovitch DG. The copYAZ operon functions in copper efflux, biofilm formation, genetic transformation, and stress tolerance in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:2545–2557. doi: 10.1128/JB.02433-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi JW, Kwon TY, Hong SH, Lee HJ. Isolation and characterization of a microRNA-size Secretable small RNA in Streptococcus sanguinis. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2018;76:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s12013-018-0841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Ploeg JR. Regulation of bacteriocin production in Streptococcus mutans by the quorum-sensing system required for development of genetic competence. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3980–3989. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.3980-3989.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biswas S, Cao L, Kim A, Biswas I. SepM, a streptococcal protease involved in quorum sensing, displays strict substrate specificity. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:436–447. doi: 10.1128/JB.00708-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acedo JZ, Chiorean S, Vederas JC, van Belkum MJ. The expanding structural variety among bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42:805–828. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuy033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hossain MS, Biswas I. Mutacins from Streptococcus mutans UA159 are active against multiple streptococcal species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2428–2434. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02320-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merritt J, Qi F. The mutacins of Streptococcus mutans: regulation and ecology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:57–69. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2011.00634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bordeau V, Cady A, Revest M, Rostan O, Sassi M, Tattevin P, Donnio PY, Felden B. Staphylococcus aureus regulatory RNAs as potential biomarkers for bloodstream infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1570–1578. doi: 10.3201/eid2209.151801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song J, Lays C, Vandenesch F, Benito Y, Bes M, Chu Y, Lina G, Romby P, Geissmann T, Boisset S. The expression of small regulatory RNAs in clinical samples reflects the different life styles of Staphylococcus aureus in colonization vs. infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao MY, Yang YM, Li KZ, Lei L, Li M, Yang Y, Tao X, Yin JX, Zhang R, Ma XR, et al. The rnc gene promotes exopolysaccharide synthesis and represses the vicRKX gene expressions via MicroRNA-Size small RNAs in Streptococcus mutans. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:687. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durso SC, Vieira LM, Cruz JN, Azevedo CS, Rodrigues PH, Simionato MR. Sucrose substitutes affect the cariogenic potential of Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Caries Res. 2014;48:214–222. doi: 10.1159/000354410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao W, Li W, Lin J, Chen Z, Yu D. Effect of sucrose concentration on sucrose-dependent adhesion and glucosyltransferase expression of S. mutans in children with severe early-childhood caries (S-ECC) Nutrients. 2014;6:3572–3586. doi: 10.3390/nu6093572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]