Abstract

CRISPR/Cas9 technology has revolutionized biology. This prokaryotic defense system against foreign DNA has been repurposed for genome editing in a broad range of cell tissues an organisms. Trypanosomatids are flagellated protozoa belonging to the order Kinetoplastida. Some of its most representative members cause important human diseases affecting millions of people worldwide, such as Chagas disease, sleeping sickness and different forms of leishmaniases. Trypanosomatid infections represent an enormous burden for public health and there are no effective treatments for most of the diseases they cause. Since the emergence of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology, the genetic manipulation of these parasites has notably improved. As a consequence, genome editing is now playing a key role in the functional study of proteins, in the characterization of metabolic pathways, in the validation of alternative targets for antiparasitic interventions, and in the study of parasite biology and pathogenesis. In this work we review the different strategies that have been used to adapt the CRISPR/Cas9 system to Trypanosoma cruzi, Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania spp., as well as the research progres achieved using these approaches. Thereby, we will present the state-of-the-art molecular tools available for genome editing in trypanosomatids to finally point out the future perspectives in the field.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, genome editing, kinetoplastids, Leishmania, Lotmaria passim, Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, trypanosomatids

HUMANKIND has altered the genomes of living organisms for thousands of years through selective breeding or artificial selection. Since the generation of the first recombinant DNA molecule (Jackson et al., 1972) and the first genetically modified organism (Cohen et al., 1973) in the early 70’s, the scientific community has genetically modified the genes of a vast repertoire of species using biotechnology methods for a variety of purposes, but mainly in the fields of food technology and health sciences. As time goes by, methodologies for genetic engineering have rapidly improved, becoming more efficient and easy to apply. In addition, the emergence of the prokaryotic CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated gene 9) system for genome editing has revolutionized biology, leading to the genetic manipulation of an increasing number of eukaryotic organisms, ranging from protists to mammalian cells (Cong et al., 2013; DiCarlo et al., 2013; Ghorbal et al., 2014; Gratz et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2013; Lander et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2014; Sidik et al., 2014; Sollelis et al., 2015). The chronology of the prokaryotic CRISPR locus discovery, description as an adaptive immune system in archaea and bacteria, and repurposing for genome editing in eukaryotic cells, is one of the most inspiring lessons in modern science (Lander, 2016). The entire process took more than 25 years and it was marked by anecdotes of frustration, rejections in prestigious journals and funding cuts for many of the laboratories involved. However, starting in 2012, when the team led by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier showed evidence that the system could be re-programmed for the genome edition of almost any living being (Jinek et al., 2012), there has been an exponential publication of research articles adapting the system to multiple cell types and organisms, being successfully used in even the most refractory species for genome modifications, thus impelling a huge progress in the field of genetic engineering.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing consists of the prokaryotic endonuclease Cas9 (the most commonly used from Streptococcus pyogenes or SpCas9) and a programmable RNA chimera or single guide RNA (sgRNA) that is designed to target a specific sequence of the genome (Doudna and Charpentier, 2014; Hsu et al., 2013; Jinek et al., 2012). Cas9 and the sgRNA molecule assemble together in the nucleus of the cell to conform a ribonucleoprotein complex. This complex recognizes the target DNA sequence and produces a double strand break (DSB), leading to modifications in the genome sequence, depending on the DNA repair machinery of the organism (Cong et al., 2013; Doudna and Charpentier, 2014; Hsu et al., 2013). The most common DNA repair mechanisms are non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR). The first one is absent in trypanosomatids (Passos-Silva et al., 2010), but HDR is highly efficient when a DNA donor template is provided to induce DSB repair by homologous recombination at the Cas9 cleavage site (Lander et al., 2015). An alternative DSB repair mechanism named microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) has been described in trypanosomatids and does not require the presence of a DNA donor template (Glover et al., 2011; Glover et al., 2008; Peng et al., 2015), producing small deletions at the DSB site. However it is much less efficient than HDR and requires the presence of microhomology regions flanking the DSB site in the genome (Glover et al., 2008; Lander et al., 2015; Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015).

The development of molecular tools for the genetic manipulation of organisms is a key factor in basic research to answer biologically relevant questions, such as dissecting the role of essential proteins and metabolic pathways of a cell type. Trypanosomatids include human parasites Trypanosoma cruzi, T. brucei and Leishmania spp, the causative agents of Chagas disease, sleeping sickness and visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis, respectively. These diseases are worldwide spread and their etiologic agents are mainly diploid and lack introns, which facilitates in silico analyses of their genomic sequences (Burle-Caldas Gde et al., 2015; Docampo, 2011). Genetic engineering of trypanosomatids has been mainly done in T. brucei, a parasite that exhibits functional RNA interference (RNAi) machinery, allowing downregulation of specific gene targets (Kolev et al., 2011). Gene knockout can also be efficiently achieved in T. brucei by homology-directed repair (HDR), although two rounds of replacement with different resistance markers are necessary to disrupt both alleles of a gene (Docampo, 2011). However, the main orthologs of the RNAi machinery are absent in T. cruzi and have been identified in just a few species of Leishmania (Kolev et al., 2011). In addition, few conventional gene knockouts had been described in both parasites (Docampo, 2011; Lander et al., 2016a; Taylor et al., 2011). Conditional knockouts have been reported in T. brucei, while systems for inducible and constitutive expression are available in all three species (Docampo, 2011). In general, there were few molecular tools available for the genetic manipulation of T. cruzi and Leishmania spp., compared to T. brucei, thus limiting the study of biological processes in the first two parasites. Fortunately, genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 has been recently achieved in T. cruzi (Lander et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2015), L. major (Sollelis et al., 2015), L. donovani (Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015), L. mexicana (Beneke et al., 2017), T. brucei (Beneke et al., 2017; Rico et al., 2018; Vasquez et al., 2018) and the honey bee trypanosomatid Lotmaria passim (Liu et al., 2019) and the system has been successfully used to investigate the role of several proteins in trypanosomatids, but mainly in T. cruzi (Beneke et al., 2017; Bertolini et al., 2019; Chiurillo et al., 2017; Chiurillo et al., 2019; Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018b; Lander et al., 2018; Lander et al., 2015; Martel et al., 2017; Takagi et al., 2019), as shown in Table 1. In this review we described the main strategies that have been developed to perform genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in trypanosomatids, presenting examples of their usefulness for solving biological questions. After describing the state-of-the-art technology, we discuss the main factors that have been proven to be necessary to successfully perform genome editing in trypanosomatids, as well as the limitations of the system and alternative approaches to study essential genes in this group of organisms. For information on CRISPR-based genome editing in other protozoan parasites there are several reviews that has been recently published in the field (Bryant et al., 2019; Di Cristina and Carruthers, 2018; Duncan et al., 2017; Lander et al., 2016a; Suarez et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Genes that have been functionally studied in trypanosomatids using CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

| Organism | Edited gene# | Purpose | sgRNA expression* | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. cruzi | Paraflagellar rod 2, PFR2 | KO | Constitutive | Lander et al., 2015 |

| Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, IP3R | Endogenous tagging | Constitutive | Lander et al., 2016b | |

| Mitochondrial calcium uniporter, MCU | KO, endogenous tagging, complementation | Constitutive | Lander et al., 2016b; Chiurillo et al., 2017; Chiurillo et al., 2019 | |

| Mitochondrial calcium uniporter b, MCUb | KO, KI | Constitutive | Chiurillo et al., 2017; Chiurillo et al., 2019 | |

| Mitochondrial calcium uniporter c, MCUc | KO, KI, complementation | Constitutive | Chiurillo et al., 2019 | |

| Mitochondrial calcium uniporter d, MCUd | KO, complementation | Constitutive | Chiurillo et al., 2019 | |

| Mitochondrial calcium uptake 1, MICU1 | KO | Constitutive | Bertolini et al., 2019 | |

| Mitochondrial calcium uptake 2, MICU2 | KO | Constitutive | Bertolini et al., 2019 | |

| Ammonium transporter, AMT | KO, endogenous tagging | Constitutive | Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018b | |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase, PDP | KO, endogenous tagging | Constitutive | Lander et al., 2018 | |

| Transient receptor potential 1, TRP1 | Endogenous tagging | Constitutive | Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018a | |

| Transient receptor potential 2, TRP2 | Endogenous tagging | Constitutive | Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018a | |

| DNA topoisomerase 1A | Endogenous tagging | Transient, driven by T7 RNA polymerase | Costa et al., 2018 | |

| Cap guanylyltransferase-methyltransferase, CGM1 | KO | Transient, synthetic RNA oligonucleotides | Takagi et al., 2019 | |

| L. mexicana | Central pair associated protein, PF16 | KO, endogenous tagging | Transient, driven by T7 RNA polymerase | Beneke et al., 2017 |

| L. donovani | Casein Kinase 1.1, CK1.1 | KO | Transient, driven by T7 RNA polymerase | Martel et al., 2017 |

Genes used as proof of concept for different CRISPR/Cas9 strategies are not listed in this table.

All strategies involved constitutive Cas9 expression.

KO, knockout; KI, knock-in.

Trypanosoma cruzi

Within trypanosomatids, CRISPR/Cas9 technology was first used to modify the genome of T. cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas disease. This slow-progressing, life-threatening disease affects about 7 to 8 million people worldwide, mostly in Latin America where the disease is endemic (Forsyth et al., 2016; Traina et al., 2017). Chagas disease is also the most prevalent parasitic disease in the Americas, with 100 million people at risk and more than 10,000 deaths per year (Montgomery et al., 2014). Currently, there are only two accepted drugs to treat Chagas disease (Urbina and Docampo, 2003). Besides their adverse side effects, the efficacy of these drugs decreases the longer a person has been infected (Forsyth et al., 2016). Investigating T. cruzi biology is necessary for the development of alternative therapies to treat the disease. The genetic manipulation of this parasite has been historically challenging, with few reports of conventional knockouts and no reports of endogenous tagging before the emergence of CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Docampo, 2011; Lander et al., 2016a; Taylor et al., 2011). In a first study Peng et al. (Peng et al., 2015) generated a cell line that constitutively expresses Cas9, and used it to deliver an in vitro-transcribed sgRNA, with or without a DNA donor template for HDR. In the absence of DNA donor, DSB repair in T. cruzi was carried out by MMEJ, as demonstrated by whole-genome sequencing. However, the authors observed a cytotoxic effect of Cas9 heterologous expression in epimastigotes, producing low genome editing efficiencies, which were even lower in the presence of a DNA donor template to induce exogenous gene replacement. An important result of this first approach was the downregulation of endogenous genes encoding a putative fatty acid transporter (FATP), and the enzyme histidine ammonia lyase (HAL), as shown by the decrease of their activities in transfected populations. Also, this study used CRISPR/Cas9 to downregulate the expression of a gene family (β-galactofuranosyl glycosyltransferase, β-GalGT), confirming the editing of β-GalGT gene copies by whole-genome sequencing. This strategy could be useful for the generation of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated silencing libraries and for downregulation of other conserved gene families. This research group also developed an online tool for sgRNA design, named Eukaryotic Pathogen CRISPR/Cas9 technology guide RNA/DNA Design Tool (Peng and Tarleton, 2015), which is very useful for off-target analysis in the genomes of kinetoplastids or any organism of the EupathDB database (Aurrecoechea et al., 2017), and also allows custom genome upload.

In 2015, Lander et al. (Lander et al., 2015) reported a different strategy to perform genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in T. cruzi. They tested three different methodologies to disrupt non-essential endogenous genes encoding paraflagellar rod proteins 1 and 2 (PFR1 and PFR2), and a glycoprotein of 72 kDa (GP72), as proof of concept. The strategies involved either one or two integrative vectors for constitutive expression of sgRNA and Cas9 driven by the ribosomal promoter, or integrative plasmid Cas9/pTREX-n containing sgRNA and Cas9 co-transfected with a DNA donor template for HDR, to generate knockout cell lines for PFR1, PFR2 and GP72 genes. The delivery of DNA donor to induce DSB repair by homologous recombination on the PFR2 locus, produced a genome editing efficiency of 100%, generating a homogeneous double knockout population in five weeks, a result never achieved in T. cruzi before. They further confirmed the disassembly of the paraflagellar rod structure and a motility defect of PFR2-KO epimastigotes by western blot analysis and microscopy (Lander et al., 2016a). Interestingly, Lander et al. (Lander et al., 2015) did not observe Cas9 toxicity, probably due to the use of a fused version of the endonuclease with GFP. This method has been successfully used for endogenous tagging of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (TcMCU) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (TcIP3R) (Lander et al., 2016b), ammonium transporter (TcAMT) (Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018b), pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase (TcPDP) (Lander et al., 2018), transient receptor potential 1 and 2 (TcTRP1 and TcTRP2) (Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018a) and the functional characterization of the pore-forming subunits of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex, TcMCU, TcMCUb, TcMCUc, TcMCUd (Chiurillo et al., 2017; Chiurillo et al., 2019), mitochondrial calcium uptake proteins 1 and 2 (TcMICU1 and TcMICU2) (Bertolini et al., 2019), TcAMT (Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018b) and TcPDP (Lander et al., 2018), which evidences the usefulness of the system to efficiently modify the genome of T. cruzi in the presence of a DNA donor template. It is important to mention that knockout cell lines obtained through this strategy (TcMCU, TcMCUc and TcMCUd knockouts) have been recently complemented with either wild type or mutated versions of the added-back gene (Chiurillo et al., 2019). In this study the authors also performed in situ mutagenesis of TcMCUb and TcMCUc by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knock-in. Using this approach they predicted a hetero-oligomeric structure of the MCU complex and studied the importance of critical residues in the four MCU paralogs on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. To our knowledge, this is the first study using in vivo site-directed mutagenesis for the functional study of proteins in T. cruzi. Detailed protocols for genome editing in T. cruzi using this strategy are described in two methodological works (Lander et al., 2019; Lander et al., 2017). A summary of proteins that have been functionally studied using CRISPR/Cas9 technology in trypanosomatids is shown in Table 1.

A third approach for genome editing in T. cruzi involves the delivery of a ribonucleoprotein (RPN) complex composed by the Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9), and in vitro-transcribed sgRNAs by nucleofection into different stages of the parasite’s life cycle (epimastigotes and trypomastigotes) and different T. cruzi strains (Soares Medeiros et al., 2017). The system was tested with or without providing single stranded repair oligonucleotides to induce HDR, and targeting either exogenous reporter genes (tdTomato, mCherry and eGFP) or endogenous genes, in order to achieve gene knockout and tagging. The results indicate that this system is very efficient for the disruption of tdTomato reporter gene in T. cruzi, as assessed by flow cytometry. They also achieved simultaneous knockout of mCherry and eGFP by delivering two pools of RPNs containing sgRNAs to target both reporter genes with 55% efficiency in epimastigotes, as shown also by flow cytometry. These authors evaluated the efficiency of the method for knocking out the genes encoding a conserved hypothetical protein and calreticulin in T. cruzi epimastigotes, in the presence of a repair template containing a stop codon sequence. After evaluating several clones none of them were null mutants, although a few clones were single knockouts, a result that has been previously observed in attempts to generate knockouts in T. cruzi by conventional methods (Jimenez and Docampo, 2015; Li et al., 2011). Interestingly, this strategy was useful for generating T. cruzi parasites exhibiting flagellar and cytokinesis defects in a substantial population of epimastigotes where RPN complexes were delivered to target proven essential genes for the flagellar structure, as observed by bright-field microscopy (Soares Medeiros et al., 2017). This group also studied the effect of RPN-mediated knockdown of genes encoding nitroreductase (NTR), an enzyme involved in the activation of anti-T. cruzi compounds benznidazole and nifurtimox, and the target of posaconazole, CYP51. The knockdown of both genes reduced the sensitivity to the respective drugs, which represents an indirect evidence of the downregulation of suspected essential genes in this parasite. In addition, selection-free endogenous tagging was performed at an internal site of GP72 protein using SaCas9 RPNs. Finally, by tdTomato loss of fluorescence this group showed the potential usefulness of the method for gene silencing in other trypanosomatids (T. brucei bloodstream forms and Leishmania major promastigotes).

Based in the first two described systems for genome editing in T. cruzi (Lander et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2015), another group published a method merging both techniques to improve their genome editing efficiencies. Romagnoli et al. (Romagnoli et al., 2018) used the Cas9-GFP sequence from Cas9/pTREX-n vector (Lander et al., 2015) to generate a cell line constitutively expressing a Cas9-GFP fusion. This cell line was further used for transfection with in vitro-transcribed sgRNAs to target the genes encoding GFP and three endogenous proteins: GP72, α-tubulin and β-tubulin. The merged strategy allowed the expression of non-toxic Cas9-GFP in T. cruzi Dm28c strain epimastigotes and transfection with sgRNAs with no need for previous cloning. By flow cytometry they observed 95% loss of fluorescence at day 5 post-transfection using sgRNAs to target GFP. In this study the authors also obtained mutant cell lines with the expected phenotypes when targeting the three endogenous genes: flagellar detachment from the cell body for GP72-targeted epimastigotes, and multinucleated/multiflagellated parasites when targeting α-tubulin and β-tubulin, as expected. The main advantage of this method is the possibility of transfecting different sgRNAs simultaneously, which could be useful for targeting several genes. However, in the absence of a DNA donor template to induce HDR, the double strand break produced by Cas9 would be repair by MMEJ, which is a less efficient DNA repair mechanism in trypanosomatids (Beneke et al., 2017; Burle-Caldas et al., 2018; Chiurillo et al., 2016; Lander et al., 2015; Sollelis et al., 2015; Vasquez et al., 2018; Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015). In addition, the transient expression of in vitro-transcribed sgRNAs could reduce the efficiency of the method. Therefore, more endogenous genes should be used to test this system.

In a comparative approach, Burle-Caldas et al. (Burle-Caldas et al., 2018) assessed two genome editing protocols modified from previous studies (Lander et al., 2015; Soares Medeiros et al., 2017). One of the protocols involves the constitutive expression of SpCas9-GFP with sgRNAs that were either constitutively expressed or in vitro-transcribed. The second protocol involves the use of SaCas9 RPNs with of without single stranded oligonucleotides (SSO) to induce HDR. All the experiments in this work were performed targeting GP72 gene as proof of concept. The results using SpCas9-GPF were similar to those reported by Lander et al. (Lander et al., 2015), where gene editing efficiency was much higher in the presence of a DNA donor template than in its absence, confirming than the HDR mechanism is more efficient that MMEJ for DSB repair in T. cruzi. However, in the absence of a selective marker, they did not achieve 100% gene disruption with this method, as previously observed when using a Blasticidin-S deaminase (Bsd) cassette as DNA donor template to generate a double knockout (Chiurillo et al., 2017; Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018b; Lander et al., 2018; Lander et al., 2015). Using SaCas9 RPNs these authors achieved 37% gene knockdown in the presence of SSOs (HDR mechanism) as previously reported (Soares Medeiros et al., 2017). However, in the absence of SSOs they did not observe parasites with the expected phenotype (detached flagellum), confirming the low efficiency of MMEJ for DSB repair in T. cruzi.

An interesting approach to perform in vivo studies with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout cell lines was published last year (Costa et al., 2018). In this study the authors generated a T. cruzi reporter cell line that expresses a fusion protein between red-shifted luciferase and GFP domains (Luc::Neon reporter). This bioluminescent/fluorescent cell line allows following the kinetics of the infection in a murine model and also visualize individual fluorescent parasites in tissue sections for cellular biology purposes. This cell line was also engineered for CRISPR/Cas9 functionality to facilitate genome editing using a PCR-based approach that has been also used in T. brucei and Leishmania (Beneke et al., 2017) (Table 1). This reporter cell line can be used for the generation of bioluminescent/fluorescent/null mutants, to evaluate in vivo the phenotype generated by downregulation of endogenous genes. The system was assessed by knocking out GP72, by replacing a green fluorescent protein (mNeonGreen) by a red fluorescent protein (mScarlet) and by performing endogenous tagging of DNA topoisomerase 1A. In this system, the reporter cell line constitutively expresses T7 RNA polymerase and Cas9 while sgRNA are delivered as PCR products containing the T7 promoter upstream the specific sgRNA sequence for in vivo transcription. Donor DNA templates were PCR amplified and included 30 nt homology arms to induce HDR. Interestingly, in this approach the authors used two selective markers in two homology templates (PAC and BSD, conferring puromycin and blasticidin resistance, respectively). However, it has been shown that only one selective marker is necessary to replace both alleles of a gene when Cas9 is constitutively expressed in T. cruzi (Lander et al., 2015). Therefore, the use of two selective markers is probably necessary because in this strategy the sgRNA is transiently expressed (Costa et al., 2018). For GP72 and mNeonGreen, gene editing was highly efficient. However, a lower editing efficiency was observed for the C-terminal tagging of DNA topoisomerase 1A. The main advantage of this methodology is that it represents a cloning-free CRISPR/Cas9 method that does not require the in vitro-transcription and further purification of sgRNAs. Also, as Cas9 is constitutively expressed, it probably increases the efficiency of the technique.

A recent work involving genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in T. cruzi was performed using proliferable extracellular amastigotes. In this work Takagi et al. (Takagi et al., 2019) standardized a method to culture amastigote-like cells obtained by in vitro differentiation of tissue culture-derived trypomastigotes. They first generated a Cas9-expressing T. cruzi cell line (epimastigote stage), and after selection cells were in vitro-differentiated into metacyclic trypomastigotes (metacyclogenesis), used for infection of tissue-cultured mammalian cells, and collected from supernatants as trypomastigotes. Then, cells were in vitro-differentiated into extracellular amastigotes (EAs) under acidic conditions and immediately used for transfection with two synthetic RNA oligonucleotides that after annealing conform the specific guide RNA (gRNA). This approach was assessed by targeting an exogenous gene (eGFP, present in the Cas9-eGFP fusion protein), and the endogenous gene TcCGM1 (cap guanylyltransferase-methyltransferase), an ortholog of the T. brucei gene encoding the mRNA capping enzyme TbCgm1, essential for cell proliferation (Table 1). In this study, eGFP downregulation was evidenced by loss of fluorescence. Genome editing was confirmed by gDNA analysis in the Cas9-eGFP expressing cell line after transfection with a gRNA targeting the eGFP gene. By targeting this exogenous gene, the authors achieved knockout efficiencies higher than 95% in both, epimastigotes and amastigotes. After targeting endogenous gene TcCGM1 they evaluated enzyme activity in axenic culture of extracellular amastigotes and observed that it significantly decreased. This group also observed a defect in the proliferation of intracellular amastigotes after host cell invasion with transfectant EAs. Although no direct evidence of genome editing at the TcCGM1 locus in amastigotes was shown, the strong phenotype observed in extracellular and intracellular amastigotes indicate this strategy could be very useful to evaluate gene essentiality in amastigotes, a stage that has been little studied in T. cruzi life cycle, and is a key stage for the study of host-parasite interactions and for the validation of alternative drug targets in this organism.

Leishmania spp.

Leishmaniases are animal and human diseases caused by more than twenty species belonging to the genus Leishmania. These protozoan parasites are transmitted to humans by the bites of infected phlebotomine sandflies, which are insect vectors world-wide distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. There are three main forms of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral (fatal) leishmaniasis. Currently, there is an estimate of 1.2 million cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis and 0.4 million cases of visceral leishmaniasis per year, resulting in about 30,000 annual deaths, while 350 million people are at risk of acquiring these diseases (Jones et al., 2018). Although there are medicines available to treat leishmaniasis, the emergence of more efficient treatments with shorter administration periods and improved safety profiles are demanded.

The genetic manipulation of Leishmania parasites has been historically challenging and time-consuming. The strategy of conventional knockout by gene replacement in Leishmania spp. involves multiple cloning steps, long flanking regions in the DNA cassette to promote HDR, and two rounds of transfection with different resistance markers for generation of null mutants (Duncan et al., 2017). In addition, attempts to knockout essential genes for promastigotes viability have shown that Leishmania parasites can alter the copy number of a gene by gene duplication or changes in cell ploidy, retaining it in the genome (Beverley, 2003). During this two-step gene deletion process, compensatory mutations usually appear, leading to the failure of this knockout strategy (Dacher et al., 2014). This scenario has substantially changed after the emergence of CRISPR/Cas9 and its adaptation to Leishmania spp.

Chronologically speaking, the second trypanosomatid where CRISPR/Cas9 was used for genome editing was Leishmania major. In 2015, Sollelis and colleagues (Sollelis et al., 2015) developed a strategy using one vector for expression of Cas9 and another vector for expression of a specific sgRNA, driven by the LmU6 promoter, and a DNA donor template. In this work the authors targeted the entire paraflagellar rod 2 (LmPFR2) tandem, which has three gene copies in L. major. The knockout analysis was performed by PCR, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), western blot analysis, fluorescence microscopy and whole genome sequencing. In this way the authors demonstrated that PFR2 was absent in knockout parasites with a very high efficiency. This study showed for the first time strong evidence of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in L. major.

CRISPR/Cas9 was also used for genome editing in L. donovani (Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015). In this extensive work the researchers followed a two-vector strategy, for the simultaneous expression of Cas9 and the sgRNA driven by the ribosomal promoter. They tested two different versions of the sgRNA vector, with or without a ribozyme sequence downstream of the sgRNA to avoid polyadenylation and generate the proper guide length. Using these two strategies the authors generated knockout and endogenous C-terminal tagged cell lines of the gene encoding miltefosine transporter (LdMT), leading to the selection of miltefosine (MLF) resistant parasites. Interestingly, the results indicate that presence of the ribozyme downstream the sgRNA sequence actually increased the percentage of MLF resistant parasites after 6 weeks of transfection. However, as previously shown in T. cruzi (Lander et al., 2015), a functional sgRNA could be generated in the absence of a transcription terminator sequence when the expression of the sgRNA is driven by the ribosomal promoter. In both cases the sgRNA processing occurs through an unknown mechanism. The results of Zhang and Matlashewski (Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015) confirmed the success of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in Leishmania spp. and provided strong evidence of the DSB repair mechanisms in L. donovani. In general, this research group improved the CRISPR/Cas9 strategy in Leishmania in different aspects: the use of shorten regions for HDR, the use of a stronger RNA polymerase I promoter (rRNAP) to drive sgRNA transcription, and the use of a single vector to express both Cas9 and the sgRNA. Matlashewski’s group subsequently used this system to downregulate multi-copy genes, something that was not possible to do by conventional knockout (Zhang et al., 2017). In this second work they targeted the A2 multigene family together with the miltefosine transporter gene, to select for miltefosine-resistant L. donovani promastigotes. In this strategy there is no need for integration of the selectable marker at the Cas9 target site. The main disadvantage of this system is probably the need for performing multiple transfections to increase the editing efficiency, which could be time-consuming. An important contribution of this work is the generation of a vector for co-expression of Cas9 and the sgRNA, that can be used for genome editing in different Leishmania species, including L. donovani, L. major, and L. mexicana.

More recently, a genome editing toolkit for kinetoplastids has been successfully used in L. mexicana, L. major and L. donovani (Beneke et al., 2017; Martel et al., 2017). This cloning-free system has also been adapted for gene editing in T. brucei and T. cruzi (Beneke et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2018) and involves the PCR-amplification of both, a sgRNA template for in vivo transcription and the homology cassettes to induce DSB repair as explained in the T. cruzi section. The PCR-generated DNA templates are used to transfect parasites constitutively expressing Cas9 and the T7RNAP (Cas9 T7 cells). The main contribution of this work is that it provides detailed protocols for gene knockout and N- or C-terminal gene tagging in kinetoplastids, using a cloning-free system that requires less than 30 nucleotides flanking regions for DNA repair by either HDR or MMEJ, although the repair mechanism was not further investigated. Beneke et al. (Beneke et al., 2017) tested the system by tagging three L. mexicana genes: PF16 (encoding a central pair protein of the axoneme), SMP-1 (small myristoylated protein 1) and histone H2B. They also generated PF16 and LPG1 (encoding galactofuranosyl transferase) gene knockouts and in all cases, mutant (tagged or KO) cell lines were generated in 6-7 days, with intact locus undetectable in the entire population and exhibiting the expected phenotypes. For LPG1 gene knockout the authors also generated an add-back (gene restoration) cell line, which is a key step in reverse genetics. A Cas9 T7 cell line was also generated in L. major promastigotes and T. brucei bloodstream forms. Then, these cell lines were used to generate LmPF16 and TbGPI-PLC (encoding glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C) gene knockouts, demonstrating the usefulness of the system to perform genome editing in other kinetoplastid species. In addition to the plasmids designed for PCR-generation of template DNAs, Beneke et al. (Beneke et al., 2017) also provided an online tool for primer design using their system, which has been proven to be rapid, reliable and useful to target single genes and potentially useful for high throughput genome screening (Beneke et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2018; Martel et al., 2017).

Trypanosoma brucei

Trypanosoma brucei belongs to the group of trypanosomes that causes Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT, also known as sleeping sickness), an endemic parasitic disease occurring in 36 sub-Saharan Africa countries where there are tsetse flies that transmit T. brucei. There is no vaccine available for this disease and chemotherapy also remains unsatisfactory, especially for advanced cases when a neurological phase has been reached and the disease becomes potentially fatal. Trypanosoma brucei has been widely used as a model for genetic manipulation of trypanosomatids, which has been historically easier in T. brucei than in T. cruzi and Leishmania spp (Docampo, 2011). Reverse genetics in T. brucei has been facilitated by the intrinsic characteristics of the parasite, such as the presence of the RNAi machinery that allows rapid phenotype verification after gene downregulation; the high efficiency of homologous recombination and transfections; the development of inducible systems for gene expression; and the ability to perform gene knockouts, gene complementation and tagging using conventional methods (Kolev et al., 2011; Matthews, 2015). The abundant molecular tools available for T. brucei could explain the fact that the CRISPR/Cas9 technology emerged later in this parasite than in other trypanosomatids, in which the system was absolutely necessary for genetic engineering.

CRISPR/Cas9 was first reported in T. brucei by Beneke et al. (Beneke et al., 2017), developing a genome editing toolkit for kinetoplastids (see Leishmania spp. section). This cloning-free system requires a parental cell line co-expressing T7 RNA polymerase and Cas9, which will be transfected with two PCR fragments. One of them contains a sgRNA sequence downstream the T7 promoter, to allow the in vivo transient transcription of this molecule. The second PCR product contains the DNA repair cassette with 30 bp homology regions. For gene tagging, only one DNA repair template in necessary to facilitate genome editing. For gene knockouts, two different resistance markers should be co-transfected with the sgRNA template, to end up with a triple resistant knockout cell line. The method was shown to be efficient in T. brucei bloodstream forms for knocking out TbGPI-PLC gene, as mentioned above (Beneke et al., 2017). This method allows the detection of knockout parasites at 6-7 days post-transfection. Further analysis of clonal populations by PCR and by quantitating the release of soluble VSG into the medium (GPI-PLC null mutants do not exhibit this phenotype) demonstrated the deletion of both alleles in triple resistant parasites. This is a fast a reliable strategy for gene deletion in T. brucei, however the number of selectable markers in this cell line could restrict the system for further genetic interventions.

A second strategy for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in T. brucei was recently reported by Rico et al. (Rico et al., 2018) and claims the advantage of being inducible and selection-free, using a T. brucei codon-optimized Cas9. This system includes a DNA template to promote DSB repair by HDR, with approximately 50 bp single stranded oligonucleotide repair template; or by MMEJ in the absence of the template DNA. The system was optimized to enhance Cas9 expression driven by a tetracycline-inducible ribosomal RNA promoter, which allows temporal control of the endonuclease to reduce its potential toxicity and off-target effects. In addition, the constitutive expression of the sgRNA was driven by T7 promoter, including the sequence of hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme at the sgRNA 3’ end. By RNA blot the authors demonstrated the generation of sgRNAs of the proper size (96 bp) that were stabilized by Cas9, providing evidence for assembly of Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoproteins in T. brucei. However, a sgRNA control generated in the absence of the HDV ribozyme was not included in the analysis. The molecular constructs were used to transfect T. brucei 2T1T7 bloodstream forms, which are parasites expressing the tetracycline repressor and the T7 RNA polymerase (Alsford et al., 2005). The system was used to disrupt genes encoding aquaglyceroporin (AQP2) and amino acid transporter 6 (AAT6), conferring resistance to the clinical drugs pentamidine and eflornithine, respectively. Resistance to these drugs was used to assay editing efficiencies. Using this system they were able to achieve genome editing efficiencies close to 100% without further selection. This is a promising methodology for precision base editing that should be further tested using endogenous genes that do not confer drug resistance at all, and thus confirm the efficiency of this selection-free method.

An interesting approach to achieve genome editing in T. brucei was recently published by Vasquez et al. (Vasquez et al., 2018). In this study the authors developed an episome-based CRISPR/Cas9 system in which wild type procyclic forms were genetically modified by nucleofection of Cas9 and sgRNAs delivered as episome, and in the presence of a template DNA for DSB repair. The system was optimized for sequential transfection of the episomes (first, Cas9 episome and then sgRNA/repair template episome) using GFP as reporter gene. This method was used for precise editing of genes that are present in multicopy arrays, such as H3.V and H4.V histone variants. The approach used by Vasquez and colleagues (Vasquez et al., 2018), introduces a genome editing strategy that allows the disruption of multicopy genes, which are very abundant in the genome of trypanosomes and have been left aside because there were no molecular tools to dissect their functions before the CRISPR era.

Lotmaria passim

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been recently used for genome editing in the honey bee trypanosomatid parasite Lotmaria passim (Liu et al., 2019). This is the first report of genome editing in a trypanosomatid that is not a vertebrate pathogen. Using T. cruzi plasmids for constitutive expression of Cas9 and sgRNA, and providing a DNA template to induce homology-directed repair, these authors disrupted the endogenous miltefosine transporter (LpMT) and tyrosine aminotransferase (LpTAT) genes by replacement with hygromycin resistance marker. This system represents a useful approach to study L. passim biology and to elucidate the mechanisms driving honey bee-parasite interactions.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

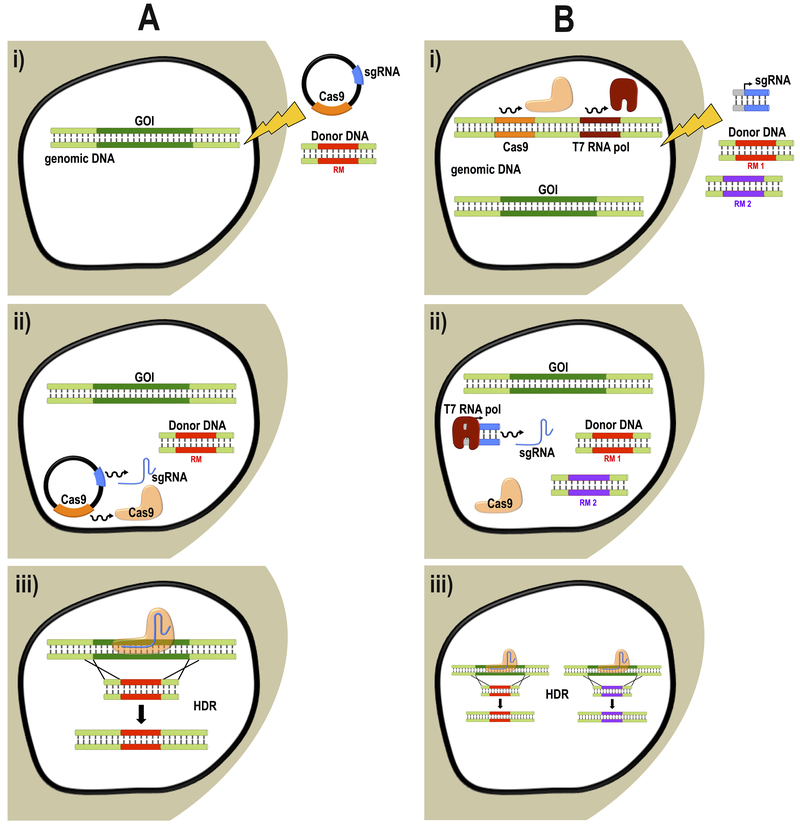

In the last five years CRISPR/Cas9 technology has changed the pace and course of research in trypanosomatids. Important findings have been reported on the structural and biochemical characterization of proteins involved in different metabolic pathways and signaling cascades in T. cruzi, T. brucei and Leishmania spp. (Beneke et al., 2017; Bertolini et al., 2019; Chiurillo et al., 2017; Chiurillo et al., 2019; Costa et al., 2018; Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018b; Lander et al., 2018; Lander et al., 2017; Martel et al., 2017; Vasquez et al., 2018) (Table 1). Several approaches have been successfully used to adapt the CRISPR/Cas9 system and modify these parasites’ genomes. Based on the current literature, there are two key aspects to achieve efficient genome editing outputs in kinetoplastids. The first one is the constitutive expression of Cas9, which in most cases does not interfere with cell viability in trypanosomatids. Constitutively expressed Cas9 ensures DNA cleavage at both alleles of the locus (Beneke et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2018; Lander et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2015; Sollelis et al., 2015; Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015). Using an inducible system, the nuclease can be further turned off to avoid off-targeting and Cas9 cytotoxicity (Rico et al., 2018). Providing an appropriate DNA template to promote DSB repair by HDR is the second aspect that significantly improves the genome editing strategy, as this DNA repair mechanism has resulted to be more efficient than MMEJ in trypanosomatids (Beneke et al., 2017; Burle-Caldas et al., 2018; Chiurillo et al., 2016; Lander et al., 2015; Sollelis et al., 2015; Vasquez et al., 2018; Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015). Other factors could affect the efficiency of the system, such as the DNA delivery system (nucleofection is a more efficient electroporation method than transfection); the possibility of performing cell sorting during the selection period, to enrich the population of genetically modified parasites or even get mutant clones; and the presence of a resistance marker in the DNA donor template to ensure the selection of parasites with properly edited genomes. Selection-free methods are useful when there is an expected phenotype associated to the deletion of a gene, as for example, drug resistance (Rico et al., 2018; Soares Medeiros et al., 2017; Zhang and Matlashewski, 2015) or flagellar detachment (Burle-Caldas et al., 2018). However, for genes encoding proteins of unknown function, the inclusion of a resistance marker or reporter gene in the DNA donor template is the best option to efficiently achieve genome editing in trypanosomatids (Beneke et al., 2017; Bertolini et al., 2019; Chiurillo et al., 2017; Chiurillo et al., 2019; Costa et al., 2018; Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018a; Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018b; Lander et al., 2018; Lander et al., 2016b; Lander et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019; Martel et al., 2017). Figure 1 describes the two strategies that have been most widely used for genome editing in kinetoplastids (Beneke et al., 2017; Lander et al., 2015).

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of the two main strategies used for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in trypanosomatids. Both strategies involve the constitutive expression of Cas9 and provide a donor DNA template to induce DSB repair by HDR. A, The methodology originally described by Lander et al. (2015) in T. cruzi involves: i) co-transfection of an integrative vector for expression of Cas9 and a specific sgRNA, together with a donor DNA template containing a resistance marker (RM) flanked by homology regions; ii) co-expression of Cas9 and sgRNA, which will assemble in the nucleus of the cell to conform a ribonucleoprotein complex; and iii) Cas9 will be targeted by sgRNA to the gene of interest (GOI), producing a DNA cleavage that will be repair by homologous recombination, producing first allele replacement by the resistance marker. Constitutive expression of Cas9 and sgRNA allows sequential replacement of the second allele using the first replaced allele as template. B, Strategy developed by Beneke et al. [26] as a toolkit for genome editing in L. mexicana, L. major and T. brucei. i) The method involves the use of a parental cell line expressing Cas9 and T7 RNA polymerase (T7 RNA Pol) for nucleofection of three PCR products: two donor DNAs with different resistance markers (RM 1 and RM 2) and a DNA fragment holding the specific sgRNA sequence downstream the T7 promoter for in vivo transcription; ii) In the nucleus of the cell transiently expressed sgRNA assembles with Cas9; iii) Cas9 targets both alleles of the gene, which are simultaneously replaced by two different resistance markers.

A factor that has been widely discussed by different laboratories in the field is the need of reducing the selection periods necessary to obtain mutant parasites by CRISPR/Cas9. Selection times between 3 days to 5 weeks have been reported for the generation of mutant cell lines in these organisms (Beneke et al., 2017; Lander et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2015; Romagnoli et al., 2018; Soares Medeiros et al., 2017). But there are differences in the way these periods are defined. First, there is an important difference between the generation of a double resistant population and a stable, clonal population of null mutant parasites. Genome plasticity is a hallmark of kinetoplastids and even though genome editing occurs within a few days post transfection, the modification of both alleles by a single homology template at a specific locus takes longer. In addition, clonal populations obtained by either cell sorting or limiting dilution, take a few weeks to reach a reasonable culture volume for further phenotype analysis. Whereas the loss of fluorescence of a reporter gene can be detected 3 days post-transfection, the loss of function of a channel or enzyme would take longer periods to be confirmed in a population. In general, selection time is intrinsic to the parasite’s biology (doubling time, antibiotic sensitivity) while transfection efficiency is determined by methodological factors. The last aspect that has been pointed out in different studies is the ability to delete essential genes by CRISPR/Cas9. In that case the definition of gene essentiality has to be taken in account. Essential genes encode essential proteins. Thus, essentiality can be identified in different ways. For example, a lethal phenotype in all life cycle stages, a conditional lethal phenotype that depends on growth conditions such as temperature or nutrient availability, or essentiality in one life cycle stage but not another (Duncan et al., 2017). A gene that generates a lethal phenotype when silenced throughout the entire life cycle of the parasite cannot be disrupted either by CRISPR/Cas9 or traditional knockout methods. Such essential genes should be studied by conditional knockout or knockdown methods (conventional or inducible). The absence of the NHEJ pathway for double strand break repair in trypanosomatids makes inducible Cas9 expression useless for the disruption of essential genes, as a resistance marker should be provided in a DNA donor template to promote HDR. Gene knockout by CRISPR/Cas9 is useful for essential genes with lethal phenotypes in life cycle stages other than that where the null mutant was selected, or for gene knockouts with conditional lethal phenotypes (Chiurillo et al., 2017; Lander et al., 2015). In T. brucei and some Leishmania species, RNAi is an important tool for inducible knockdown to study essential genes (Beverley, 2003; Kolev et al., 2011). More recently, the glucosamine-induced glmS ribozyme has been successfully used for inducible knockdown in T. brucei (Cruz-Bustos et al., 2018c). However, inducible knockdown methods are not available yet for T. cruzi. The emergence of either conditional knockout or inducible knockdown system will be determinant to accelerate the identification and validation of alternative drug targets for the treatment of Chagas disease. In that sense, a new CRISPR-based system that targets RNA instead of DNA and exhibits two different types of RNAse activity has been recently described in prokaryotes (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Cox et al., 2017; East-Seletsky et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018). The system has been successfully adapted to mammalian cells and includes a Cas13 nuclease that processes multiple CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) from a single transcript, and also acts as an RNA-guided RNAse, without modifying the genomic DNA sequence (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018). These new family of CRISPR-associated nucleases are promising alternatives for the study of essential genes and multigene families in trypanosomatids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Roberto Docampo for revising this manuscript and providing valuable suggestions to improve its writing. Funding for this work has been provided by U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants AI107663 and AI140421).

LITERATURE CITED

- Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Essletzbichler P, Han S, Joung J, Belanto JJ, Verdine V, Cox DBT, Kellner MJ, Regev A, Lander ES, Voytas DF, Ting AY, and Zhang F. 2017. RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature. 550:280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsford S, Kawahara T, Glover L, and Horn D. 2005. Tagging a T. brucei rRNA locus improves stable transfection efficiency and circumvents inducible expression position effects. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 144:142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurrecoechea C, Barreto A, Basenko EY, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Cade S, Crouch K, Doherty R, Falke D, Fischer S, Gajria B, Harb OS, Heiges M, Hertz-Fowler C, Hu S, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Lawrence C, Li W, Pinney DF, Pulman JA, Roos DS, Shanmugasundram A, Silva-Franco F, Steinbiss S, Stoeckert CJ Jr., Spruill D, Wang H, Warrenfeltz S, and Zheng J. 2017. EuPathDB: the eukaryotic pathogen genomics database resource. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D581–D591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneke T, Madden R, Makin L, Valli J, Sunter J, and Gluenz E. 2017. A CRISPR Cas9 high-throughput genome editing toolkit for kinetoplastids. R Soc Open Sci 4:170095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini MS, Chiurillo MA, Lander N, Vercesi AE, and Docampo R. 2019. MICU1 and MICU2 Play an Essential Role in Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake, Growth, and Infectivity of the Human Pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. MBio. 10: e00348–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverley SM 2003. Protozomics: trypanosomatid parasite genetics comes of age. Nat Rev Genet 4:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant JM, Baumgarten S, Glover L, Hutchinson S, and Rachidi N. 2019. CRISPR in Parasitology: Not Exactly Cut and Dried! Trends Parasitol. 35: 409–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burle-Caldas GA, Soares-Simoes M, Lemos-Pechnicki L, DaRocha WD, and Teixeira SMR. 2018. Assessment of two CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing protocols for rapid generation of Trypanosoma cruzi gene knockout mutants. Int J Parasitol. 48:591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burle-Caldas Gde A, Grazielle-Silva V, Laibida LA, DaRocha WD, and Teixeira SM. 2015. Expanding the tool box for genetic manipulation of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 203:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiurillo MA, Lander N, Bertolini MS, Storey M, Vercesi AE, and Docampo R. 2017. Different Roles of Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Complex Subunits in Growth and Infectivity of Trypanosoma cruzi. MBio. 8: e00574–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiurillo MA, Lander N, Bertolini MS, Vercesi AE, and Docampo R. 2019. Functional analysis and importance for host cell infection of the Ca2+-conducting subunits of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biol Cell. 30: mbcE19030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiurillo MA, Moraes Barros RR, Souza RT, Marini MM, Antonio CR, Cortez DR, Curto MA, Lorenzi HA, Schijman AG, Ramirez JL, and da Silveira JF. 2016. Subtelomeric I-SceI-Mediated Double-Strand Breaks Are Repaired by Homologous Recombination in Trypanosoma cruzi. Front Microbiol 7:2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SN, Chang AC, Boyer HW, and Helling RB. 1973. Construction of biologically functional bacterial plasmids in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 70:3240–3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, and Zhang F. 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 339:819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa FC, Francisco AF, Jayawardhana S, Calderano SG, Lewis MD, Olmo F, Beneke T, Gluenz E, Sunter J, Dean S, Kelly JM, and Taylor MC. 2018. Expanding the toolbox for Trypanosoma cruzi: A parasite line incorporating a bioluminescence-fluorescence dual reporter and streamlined CRISPR/Cas9 functionality for rapid in vivo localisation and phenotyping. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DBT, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Franklin B, Kellner MJ, Joung J, and Zhang F. 2017. RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science. 358:1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Bustos T, Moreno SNJ, and Docampo R. 2018a. Detection of Weakly Expressed Trypanosoma cruzi Membrane Proteins Using High-Performance Probes. J Eukaryot Microbiol 65:722–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Bustos T, Potapenko E, Storey M, and Docampo R. 2018b. An Intracellular Ammonium Transporter Is Necessary for Replication, Differentiation, and Resistance to Starvation and Osmotic Stress in Trypanosoma cruzi. mSphere. 3: e00377–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Bustos T, Ramakrishnan S, Cordeiro CD, Ahmed MA, and Docampo R. 2018c. A Riboswitch-based Inducible Gene Expression System for Trypanosoma brucei. J Eukaryot Microbiol 65:412–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacher M, Morales MA, Pescher P, Leclercq O, Rachidi N, Prina E, Cayla M, Descoteaux A, and Spath GF. 2014. Probing druggability and biological function of essential proteins in Leishmania combining facilitated null mutant and plasmid shuffle analyses. Mol Microbiol 93:146–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristina M, and Carruthers VB. 2018. New and emerging uses of CRISPR/Cas9 to genetically manipulate apicomplexan parasites. Parasitology. 145:1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, Rios X, Aach J, and Church GM. 2013. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res 41:4336–4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R 2011. Molecular parasitology in the 21st century. Essays Biochem 51:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna JA, and Charpentier E. 2014. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 346:1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SM, Jones NG, and Mottram JC. 2017. Recent advances in Leishmania reverse genetics: Manipulating a manipulative parasite. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 216:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East-Seletsky A, O’Connell MR, Burstein D, Knott GJ, and Doudna JA. 2017. RNA Targeting by Functionally Orthogonal Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas Enzymes. Mol Cell. 66:373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CJ, Hernandez S, Olmedo W, Abuhamidah A, Traina MI, Sanchez DR, Soverow J, and Meymandi SK. 2016. Safety Profile of Nifurtimox for Treatment of Chagas Disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 63:1056–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbal M, Gorman M, Macpherson CR, Martins RM, Scherf A, and Lopez-Rubio JJ. 2014. Genome editing in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Biotechnol 32:819–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover L, Jun J, and Horn D. 2011. Microhomology-mediated deletion and gene conversion in African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res 39:1372–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover L, McCulloch R, and Horn D. 2008. Sequence homology and microhomology dominate chromosomal double-strand break repair in African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res 36:2608–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz SJ, Cummings AM, Nguyen JN, Hamm DC, Donohue LK, Harrison MM, Wildonger J, and O’Connor-Giles KM. 2013. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics. 194:1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, Cradick TJ, Marraffini LA, Bao G, and Zhang F. 2013. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 31:827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DA, Symons RH, and Berg P. 1972. Biochemical method for inserting new geneticinformation into DNA of Simian Virus 40: circular SV40 DNA molecules containing lambda phage genes and the galactose operon of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 69:2904–2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Zhou H, Bi H, Fromm M, Yang B, and Weeks DP. 2013. Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez V, and Docampo R. 2015. TcPho91 is a contractile vacuole phosphate sodium symporter that regulates phosphate and polyphosphate metabolism in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Microbiol 97:911–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, and Charpentier E. 2012. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 337:816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NG, Catta-Preta CMC, Lima A, and Mottram JC. 2018. Genetically Validated Drug Targets in Leishmania: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. ACS Infect Dis 4:467–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolev NG, Tschudi C, and Ullu E. 2011. RNA interference in protozoan parasites: achievements and challenges. Eukaryot Cell. 10:1156–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S, Lotfy P, Brideau NJ, Oki J, Shokhirev MN, and Hsu PD. 2018. Transcriptome Engineering with RNA-Targeting Type VI-D CRISPR Effectors. Cell. 173:665–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES 2016. The Heroes of CRISPR. Cell. 164:18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander N, Chiurillo MA, Bertolini MS, Storey M, Vercesi AE, and Docampo R. 2018. Calcium-sensitive pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase is required for energy metabolism, growth, differentiation, and infectivity of Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem 293:17402–17417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander N, Chiurillo MA, and Docampo R. 2016a. Genome Editing by CRISPR/Cas9: A Game Change in the Genetic Manipulation of Protists. J Eukaryot Microbiol 63:679–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander N, Chiurillo MA, and Docampo R. 2019. Genome Editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in Trypanosoma cruzi. Methods Mol Biol 1955:61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander N, Chiurillo MA, Storey M, Vercesi AE, and Docampo R. 2016b. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated endogenous C-terminal Tagging of Trypanosoma cruzi Genes Reveals the Acidocalcisome Localization of the Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor. J Biol Chem 291:25505–25515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander N, Chiurillo MA, Vercesi AE, and Docampo R. 2017. Endogenous C-terminal Tagging by CRISPR/Cas9 in Trypanosoma cruzi. Bio Protoc 7: e2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander N, Li ZH, Niyogi S, and Docampo R. 2015. CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Disruption of Paraflagellar Rod Protein 1 and 2 Genes in Trypanosoma cruzi Reveals Their Role in Flagellar Attachment. MBio. 6:e01012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZH, Alvarez VE, De Gaudenzi JG, Sant’Anna C, Frasch AC, Cazzulo JJ, and Docampo R. 2011. Hyperosmotic stress induces aquaporin-dependent cell shrinkage, polyphosphate synthesis, amino acid accumulation, and global gene expression changes in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem 286:43959–43971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Lei J, and Kadowaki T. 2019. Gene Disruption of Honey Bee Trypanosomatid Parasite, Lotmaria passim, by CRISPR/Cas9 System. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 9:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel D, Beneke T, Gluenz E, Spath GF, and Rachidi N. 2017. Characterisation of Casein Kinase 1.1 in Leishmania donovani Using the CRISPR Cas9 Toolkit. Biomed Res Int 2017:4635605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KR 2015. 25 years of African trypanosome research: From description to molecular dissection and new drug discovery. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 200:30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SP, Starr MC, Cantey PT, Edwards MS, and Meymandi SK. 2014. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: Chagas disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90:814–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos-Silva DG, Rajao MA, Nascimento de Aguiar PH, Vieira-da-Rocha JP, Machado CR, and Furtado C. 2010. Overview of DNA Repair in Trypanosoma cruzi, Trypanosoma brucei, and Leishmania major. J Nucleic Acids. 2010:840768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D, Kurup SP, Yao PY, Minning TA, and Tarleton RL. 2015. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated single-gene and gene family disruption in Trypanosoma cruzi. MBio. 6:e02097–02014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D, and Tarleton R. 2015. EuPaGDT: a web tool tailored to design CRISPR guide RNAs for eukaryotic pathogens. Microb Genom 1:e000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rico E, Jeacock L, Kovarova J, and Horn D. 2018. Inducible high-efficiency CRISPR-Cas9-targeted gene editing and precision base editing in African trypanosomes. Sci Rep 8:7960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnoli BAA, Picchi GFA, Hiraiwa PM, Borges BS, Alves LR, and Goldenberg S. 2018. Improvements in the CRISPR/Cas9 system for high efficiency gene disruption in Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta Trop. 178:190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Brown KM, Lee TD, and Sibley LD. 2014. Efficient gene disruption in diverse strains of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/CAS9. MBio. 5:e01114–01114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidik SM, Hackett CG, Tran F, Westwood NJ, and Lourido S. 2014. Efficient genome engineering of Toxoplasma gondii using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS One. 9:e100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares Medeiros LC, South L, Peng D, Bustamante JM, Wang W, Bunkofske M, Perumal N, Sanchez-Valdez F, and Tarleton RL. 2017. Rapid, Selection-Free, High-Efficiency Genome Editing in Protozoan Parasites Using CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoproteins. MBio. 8:e01788–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollelis L, Ghorbal M, MacPherson CR, Martins RM, Kuk N, Crobu L, Bastien P, Scherf A, Lopez-Rubio JJ, and Sterkers Y. 2015. First efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in Leishmania parasites. Cell Microbiol. 17:1405–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez CE, Bishop RP, Alzan HF, Poole WA, and Cooke BM. 2017. Advances in the application of genetic manipulation methods to apicomplexan parasites. Int J Parasitol. 47:701–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi Y, Akutsu Y, Doi M, and Furukawa K. 2019. Utilization of proliferable extracellular amastigotes for transient gene expression, drug sensitivity assay, and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MC, Huang H, and Kelly JM. 2011. Genetic techniques in Trypanosoma cruzi. Adv Parasitol. 75:231–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traina MI, Hernandez S, Sanchez DR, Dufani J, Salih M, Abuhamidah AM, Olmedo W, Bradfield JS, Forsyth CJ, and Meymandi SK. 2017. Prevalence of Chagas Disease in a U.S. Population of Latin American Immigrants with Conduction Abnormalities on Electrocardiogram. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11:e0005244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA, and Docampo R. 2003. Specific chemotherapy of Chagas disease: controversies and advances. Trends Parasitol. 19:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez JJ, Wedel C, Cosentino RO, and Siegel TN. 2018. Exploiting CRISPR-Cas9 technology to investigate individual histone modifications. Nucleic Acids Res 46:e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WW, Lypaczewski P, and Matlashewski G. 2017. Optimized CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing for Leishmania and Its Use To Target a Multigene Family, Induce Chromosomal Translocation, and Study DNA Break Repair Mechanisms. mSphere. 2:e00340–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WW, and Matlashewski G. 2015. CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing in Leishmania donovani. MBio. 6:e00861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]