Abstract

Several methodological gaps exist regarding assessing the relationship between antiretroviral therapy (ART) and mental health. Adopting an “HIV care continuum” perspective, data from a cross-sectional study among 2987 people living with HIV (PLHIV) in Guangxi, China were used to examine the association between ART uptake, ART adherence and mental health. ART uptake status was retrieved from medical records. ART adherence was self-reported by ART users as the number of days on which medications were taken as prescribed over the past month, with good vs. poor adherence defined with a percent adherence cut-off of 90%. Depression, anxiety, and mental-health related quality of life were used as mental health indicators. Separate analysis was conducted to assess the impact of ART uptake and ART adherence. Differences in mental health were investigated using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) adjusting for propensity scores calculated from socio-demographic, health-related, and psychosocial covariates were further conducted. MANCOVA results showed statistically significant multivariate effects for ART adherence (Wilk’s λ = 0.984, F [3, 1885] =10.26, p<0.001) but not ART uptake (Wilk’s λ = 0.998, F [3, 2476] =1.67, p=0.17). Post-hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment (α=0.05/3 = 0.0167) showed that among ART users, those with good adherence had lower scores on anxiety (p=0.006) and higher scores on MHS (p=0.007), but no difference was found for depression (p=0.023). As only ART adherence was associated with better mental health among PLHIV, in order to maximize the potential mental health benefits of ART, intervention efforts need to emphasize on treatment adherence.

Keywords: People living with HIV/AIDS, antiretroviral therapy, mental health, China

Introduction

According to the China National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, by the end of September, 2017, there were 747,000 reported PLHIV in China, among which 542,000 had received antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Chen, 2017). Although improvements in physical health thanks to ART have been reported, depression (60%) and anxiety (40%) were still prevalent among PLHIV in China (Niu, Luo, Liu, Silenzio, & Xiao, 2016).

A number of studies have been conducted to assess the relationship between ART and mental health. However, several methodological gaps exist. First, when conceptualizing ART, most studies have focused on either ART uptake or ART adherence without taking an “HIV care continuum” perspective. According to McNairy et al. (2012), the care continuum has four essential steps: linkage from testing to enrolment in care, determination of ART eligibility, ART initiation, and adherence to medication to achieve viral suppression. Second, multiple mental health indicators measured in the same study were often modelled separately without considering the potential inter-correlation. Third, not all existing studies have adequately controlled for potential confounders in the relationship between ART and mental health. These factors may include socio-demographic variables (Brandt, 2009), health-related variables (Bernard, Dabis, & de Rekeneire, 2017), and psychosocial variables (Brandt, 2009; Lam, Naar-King, & Wright, 2007).

To bridge these gaps, this study examines the relationship between ART and mental health among PLHIV in China. We hypothesize that 1) ART uptake is associated with better mental health among PLHIV and 2) better ART adherence is associated with better mental health among ART users.

Methods

Participants

Data in the current study were derived from a cross-sectional survey conducted from October 2012 to August 2013 in the Guangxi Autonomous Region (“Guangxi”) of China. Details of the study design have been described elsewhere (Qiao et al., 2015). Briefly, we selected 12 cities/counties with the largest cumulative number of reported HIV/AIDS cases in Guangxi. Approximately 10% of the patients at each city/county were randomly sampled and invited to participate in the study by local Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) staff and healthcare workers. At least three attempts (including telephone contact and/or house visitation) within 2 months were made. A total of 3,002 patients (about 90% of those contacted) agreed to participate and signed the informed consent. The survey was conducted in offices of local CDC or HIV clinics where the participants received their medical care. A total of 2,987 participants completed the survey. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Boards at the Wayne State University in the U.S and Guangxi CDC in China. Each participant received a small gift equivalent to five U.S dollars after completing the survey.

Measures

ART uptake and ART adherence:

Participants’ current ART status was retrieved from their medical records. ART users were asked about the number of days on which medications were taken as prescribed over the past month. Poor vs good ART adherence was determined with a cut-off of percent adherence at 90%.

Mental health status:

Anxiety, depression, and mental health-related quality of life (MHS) were measured. Summary of scales was provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of scales measuring mental health and psychosocial variables.

| Psychological scales | # Items | α | Sample item | Response options |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||||

| Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) (Sun, Wu, Qu, Lu, & Wang, 2014; Zung, 1971) | 20 | 0.90 | I feared of losing control. | 4-point Likert scale (1: “not at all” to 4: “a lot”) |

| Depression | ||||

| Shorten version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) (Radloff, 1977) | 10 | 0.87 | I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me. | 4-point Likert scale (0: “not at all” to 3: “a lot”) |

| Health-related quality of life | ||||

| Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV) (Wu et al., 1997) | 34 | 0.95 | How has the quality of your life been during the past 4 weeks? i.e., How have things been going for you? | Varies by dimensions |

| Social support | ||||

| The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988) The Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS-C) (Yu, Lee, & Woo, 2004) |

28 | 0.97 | Someone will provide me with the advice I need. | 5-point Likert scale (1: “never” to 5: “always”) |

| Stigma | ||||

| The Berger HIV stigma Scale(Berger, Barbara E., Carol Estwing Ferrans, n.d.) | 14 | 0.94 | I feel guilty because I have HIV. | 4-point Likert scale (1: “totally disagree” to 4: “totally agree”) |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—Consumption (AUDIT-C) (Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998) | 3 | 0.81 | How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | Varies by questions |

Covariates:

Socio-demographic factors included age, gender, income, employment, marital status, and education. Health-related factors included route of infection, time since diagnosis (for ART uptake), time on ART (for ART adherence), physical health-related quality of life (PHS), and CD4 count group. Viral load was not included as data was not available for nearly half of participants. Psychosocial factors included substance use (drug use and alcohol use), stigma, social support, and disclosure of HIV positive status. Summary of scales was provided in Table 1.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA 13.0 (College Station, TX). Pearson’s correlation among all three mental health indicators was calculated. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to assess the differences in mental health by 1) ART uptake and 2) ART adherence (good vs. poor) among ART users. Before conducting MANOVA, transformation was conducted for skewed indicators, and equality of covariance matrices was checked using the Box’s M value.

According to China’s national guideline published in 2008, at the time when data were collected, eligibility for ART was determine by a CD4 ≤ 350cells/mm3 (Ministry of Health Working Group on Clinical AIDS Treatment, 2008). However, by 2012, a relatively large number of PLHIV were already receiving universal ART regardless of CD4 count (Zhao, McGoogan, & Wu, 2019). Therefore, to assess the ART uptake and mental health relationship, analysis was first conducted among all participants. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding participants not on ART who were “not eligible” (n=499) based on the 2008 guideline.

A propensity score method with aforementioned covariates was used. Separate propensity scores were estimated for ART uptake and ART adherence. Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) adjusting for the propensity scores was further conducted. Post-hoc univariate analyses with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/3 = 0.0167) were run to identify the locations of significant differences.

Results

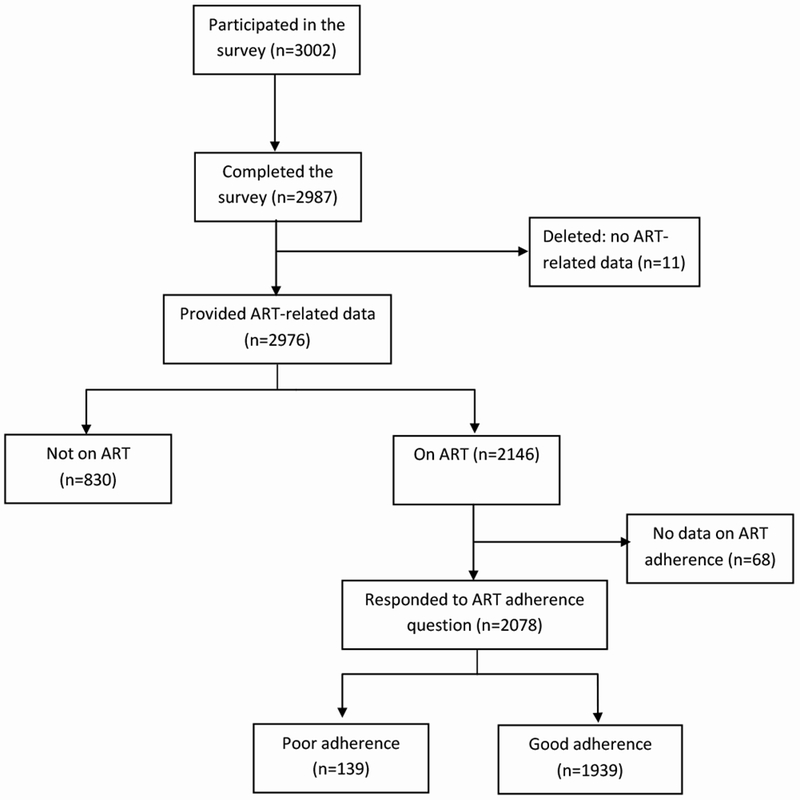

The flowchart of participants included in this study was shown in Figure 1. Of all 2,987 participants who completed the survey, data on ART use were retrieved for 2976 participants, among which 2146 (72.1%) were on ART and 830 (27.9%) were not. Among 2078 ART users who responded to the adherence question, 139 (6.7%) had poor adherence and 1939 (93.3%) had good adherence. Distribution of covariates was summarized in Table 2. Overall, the mean age was 42.4 years (SD = 12.8), most participants were males (n=1868, 62.8%), of Han ethnicity (n=2102, 70.7%), being married or cohabitated (n=2006, 69.0%), and had children (n=2451, 82.4%). Around 45% (n=1332) completed only elementary school, 26.8% were unemployed, and 46.8% had a monthly income ≥ 1000 RMB. Most participants were infected via sex (n=1956, 66.0%), and more than half (n=1712, 57.7%) reported that their HIV status was known to someone in the household. The average time since diagnosis was 38.7 months (SD = 28.7), around 25% had CD4 count less than 200 cells/mm3.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants included in this study.

Table 2:

Socio-demographic, health-related, and psychosocial characteristics by ART status groups.

| Variable | Entire cohort | Not on ART | ART users |

P value* | P value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor adherence | Good adherence | |||||

| N (%) | 2976 | 830(27.9) | 139(6.7) | 1939(93.3) | NA | NA |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||||

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 42.4±12.8 | 42.7±13.7 | 42.0 ± 13.0 | 42.4 ± 12.4 | 0.59 | 0.74 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1868(62.8) | 552(66.5) | 93(66.9) | 1181(60.9) | 0.009 | 0.16 |

| Female | 1108(37.2) | 278(33.5) | 46(33.1) | 758(39.1) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Han | 2102(70.7) | 623(75.2) | 112(80.6) | 1308(67.6) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Minority | 869(29.3) | 205(24.8) | 27(19.4) | 628(32.4) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/cohabitated | 2006(69.0) | 149(18.4) | 96(72.2) | 1360(71.7) | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Never married | 328(11.3) | 504(62.3) | 16(12.0) | 153(8.1) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 254(8.8) | 82(10.1) | 12(9.0) | 152(8.0) | ||

| Widowed | 318(10.9) | 74(9.2) | 9(6.8) | 231(12.2) | ||

| Have children | ||||||

| Yes | 2451(82.4) | 639(77.0) | 113(81.9) | 1646(84.9) | <0.001 | 0.34 |

| No | 524(17.6) | 191(23.0) | 25(18.1) | 293(15.1) | ||

| Complete education | ||||||

| Elementary school | 1332(44.9) | 387(46.9) | 79(57.2) | 834(43.1) | 0.106 | 0.004 |

| Middle school | 1224(41.9) | 347(42.0) | 47(34.1) | 825(42.7) | ||

| High school or higher | 390(13.2) | 92(11.1) | 12(8.7) | 275(14.2) | ||

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 2170(73.2) | 595(72.0) | 88(63.8) | 1437(74.4) | 0.358 | 0.006 |

| Unemployed | 793(26.8) | 231(28.0) | 50(36.2) | 494(25.6) | ||

| Monthly income | ||||||

| ≥1000 RMB | 1379(46.8) | 358(43.7) | 68(49.6) | 925(48.1) | 0.038 | 0.72 |

| <1000 RMB | 1568(53.2) | 461(56.3) | 69(50.4) | 1000(51.9) | ||

| Health-related factors | ||||||

| Route of infection | ||||||

| Sex | 1956(66.0) | 478(57.8) | 76(55.5) | 1358(70.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IDU | 471(15.9) | 180(21.8) | 33(24.1) | 245(12.7) | ||

| Blood or unknown | 536(18.1) | 169(20.4) | 28(20.4) | 328(17.0) | ||

| Months since diagnosis (Mean ± SD) | 38.7±28.7 | 32.2±28.6 | 43.7 ± 32.3 | 41.0 ± 27.8 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| Months on ART (Mean ± SD) | 34.8±23.9 | NA | 30.4 ± 23.9 | 35.4 ± 24.0 | NA | 0.02 |

| Undetectable viral load (<50 copies/ml) | ||||||

| Yes | 1218(74.3) | 27(41.5) | 60(84.5) | 1364(92.5) | <0.001 | 0.17 |

| No | 421(25.7) | 38(58.5) | 11(15.5) | 111(7.5) | ||

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | ||||||

| ≥500 | 690(23.2) | 278(33.5) | 26(18.7) | 373(19.2) | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| 351-499 | 693(23.3) | 221(26.6) | 24(17.3) | 433(22.3) | ||

| 200-350 | 855(28.7) | 155(18.7) | 40(28.8) | 645(33.3) | ||

| <200 | 738(24.8) | 176(21.2) | 49(35.2) | 488(25.7) | ||

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||

| People in the household aware of your HIV status | ||||||

| None | 612(20.6) | 254(30.9) | 26(18.7) | 318(16.4) | <0.001 | 0.47 |

| Some | 1712(57.7) | 435(52.9) | 76(54.7) | 1162(60.0) | ||

| All | 644(21.7) | 134(16.3) | 37(26.6) | 458(23.6) | ||

| Stigma (Mean ± SD) | 2.43±0.52 | 2.43±0.54 | 2.44±0.52 | 2.43±0.51 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| Social support (Mean ± SD) | 2.44±0.86 | 2.34±0.81 | 2.52±0.78 | 2.46±0.87 | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| Alcohol use | 1.55±2.43 | 1.98±2.71 | 2.04±2.60 | 1.33±2.26 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Illicit drug use | 574(19.4) | 218(26.4) | 37(27.0) | 303(15.7) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

Comparison was made between participants not on ART and ART users

Comparison was made between ART users with poor adherence and good adherence.

Moderate correlation was found between depression and anxiety (r = 0.62). MHS was negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.74) and depression (r = −0.53). MANOVA results showed marginally significant multivariate effect of ART uptake on mental health (Wilk’s λ = 0.998, F [3, 2689] =2.20, p=0.086). After adjusting for the propensity score, no statistically significant difference was found (Wilk’s λ = 0.998, F [3, 2476] =1.67, p=0.17). Similar results were found in sensitivity analysis (Wilk’s λ = 0.997, F [3, 2062] =1.88, p=0.13).

Among ART users, statistically significant difference in mental health was found by ART adherence (Wilk’s λ = 0.984, F [3, 1885] =10.26, p<0.001). The effect persisted after adjusting for the propensity score (Wilk’s λ = 0.994, F [3, 1771] =3.45, p=0.016). Post-hoc comparison showed that among ART users, well adherent patients had lower scores on anxiety (F [1, 1773] = 7.61, p=0.006) and higher scores on MHS (F [1,1773] = 7.36, p=0.007). No statistically significant difference was found for depression (F [1, 1773] = 5.21, p=0.023).

Discussions

Contrary to our hypothesis, no difference in mental health was found between ART users and patients not on ART. One possible explanation is that the difference can be masked by including patients not on ART due to having a CD4 count beyond the threshold. Studies conducted among untreated PLHIV have found strong positive association between CD4 count and mental health (Bernard et al., 2017). However, similar results were found in sensitivity analysis excluding these patients. Considering that ART may exert both positive and negative effects on mental health, it is possible that the potential mental health benefits were cancelled out by toxicities and side effects of ART.

Noticeably, among ART users, ART adherence was associated with mental health. Therefore, it is possible that ART uptake may improve mental health through improvement in physical health, which only happens for well adherent ART users. However, even after adjusting for physical health indicators, statistically significant association between good adherence and better mental health persisted. This suggests that ART, when well adhered to, may exert its positive impact on mental health separate from improvement in physical health.

There are some limitations in this study. First, ART adherence was estimated using self-report data which may be subject to self-report biases such as recall error and social desirability bias. Second, ART adherence measure without taking dose frequency into consideration might not be accurate. Third, viral load data were not available for more than half of participants, which limited our ability to consider viral load as a covariate. Fourth, the cross-sectional data prevented us from drawing causality between ART status and mental health.

Although changes in ART initiation policy have been made (universal ART regardless of CD4 level) after the study was conducted, removing the threshold may not have an influential impact on ART uptake. Studies have found that most PLHIV were diagnosed at late stages, and treatment priority was given to these patients with a low CD4 level (F. Zhang et al., 2007; L. Zhang, Gray, & Wilson, 2012; Zheng et al., 2018). Therefore, findings in the current study still have important implications. First, to maximize the potential mental health benefits of ART, intervention efforts need to emphasize on treatment adherence, especially for those late diagnosed cases. Second, more studies are needed to assess how the policy change influences patients who were diagnosed before universal ART was implemented.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child and Human Development under Grant [number R01HD074221]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant [number NSF71673146].

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, and Lashley FR (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in nursing & health, 24(6), 518–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Dabis F, & de Rekeneire N (2017). Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 12(8), e0181960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R (2009). The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: a systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research, 8(2), 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C (2017). No Title. Retrieved from http://ncaids.chinacdc.cn/xb/fzyw_10256/xgzl/201804/W020180420378390982286.pdf

- Lam PK, Naar-King S, & Wright K (2007). Social support and disclosure as predictors of mental health in HIV-positive youth. AIDS PATIENT CARE AND STDS, 21(1), 20–29. 10.1089/apc.2006.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Working Group on Clinical AIDS Treatment. (2008). China Free Antiretroviral Therapy Manual. Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- Niu L, Luo D, Liu Y, Silenzio VMB, & Xiao S (2016). The mental health of people living with HIV in China, 1998--2014: a systematic review. PloS One, 11(4), e0153489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao S, Li X, Zhou Y, Shen Z, Tang Z, & Stanton B (2015). Factors influencing the decision-making of parental HIV disclosure: a socio-ecological approach. AIDS (London, England), 29(0 1), S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Wu M, Qu P, Lu C, & Wang L (2014). Psychological well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS under the new epidemic characteristics in China and the risk factors: a population-based study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 28, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu DSF, Lee DTF, & Woo J (2004). Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-C). Research in Nursing & Health, 27(2), 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Haberer JE, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ma Y, Zhao D, … Goosby EP (2007). The Chinese free antiretroviral treatment program: challenges and responses. Aids, 21, S143–S148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Gray RT, & Wilson DP (2012). Modelling the epidemiological impact of scaling up HIV testing and antiretroviral treatment in China. Sexual Health, 9(3), 261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, McGoogan JM, & Wu Z (2019). The Benefits of Immediate ART. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC), 18, 2325958219831714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Li Y, Jiang Y, Liang X, Qin S, & Nehl EJ (2018). Population HIV transmission risk for serodiscordant couples in Guangxi, Southern China: A cohort study. Medicine, 97(36). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, & Farley GK (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WWK (1971). A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics, 12(6), 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]