Abstract

Objective:

Alterations in blood lipid concentrations in anorexia nervosa (AN) has been reported; however, the extent, mechanism, and normalization with weight restoration remain unknown. We conducted a systematic review and a meta-analysis to evaluate changes in lipid concentrations in acutely-ill AN patients compared with healthy controls (HC) and to examine the effect of partial weight restoration.

Method:

A systematic literature review and meta-analysis (PROSPERO: CRD42017078014) were conducted for original peer-reviewed papers.

Results:

Forty-eight studies were eligible for review; 33 for meta-analyses calculating mean differences (MD). Total cholesterol (MD = 22.7 mg/dL, 95% CI = 12.5, 33.0), high-density lipoprotein (HDL; MD = 3.4 mg/dL, CI = 0.3, 7.0), low-density lipoprotein (LDL; MD = 12.2 mg/dL, CI = 4.4, 20.1), triglycerides (TG; MD = 8.1 mg/dL, CI = 1.7, 14.5), and apolipoprotein B (Apo B; MD = 11.6 mg/dL, CI = 2.3, 21.2) were significantly higher in acutely-ill AN than HC. Partially weight-restored AN patients had higher total cholesterol (MD = 14.8 mg/dL, CI = 2.0, 27.5) and LDL (MD = 19.0 mg/dL, CI = 5.9, 32.0). Pre- versus post-weight restoration differences in lipid concentrations did not differ significantly.

Discussion:

We report aggregate evidence for elevated lipid concentrations in acutely-ill AN patients compared with HC, some of which persist after partial weight restoration. This could signal an underlying adaptation or dysregulation not fully reversed by weight restoration. Although concentrations differed between AN and HC, most lipid concentrations remained within the reference range and meta-analyses were limited by the number of available studies.

Keywords: eating disorder, lipids, cholesterol, weight restoration, re-nutrition

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is characterized by restriction of food intake, and low body mass index (BMI). Accompanying symptoms include fear of weight gain, an aversion to foods rich in fat and sugar, excessive exercise, distorted body image, and seeming inability to recognize the seriousness of the low weight (American Psychiatric American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Chronicity is high in AN, and evidence base for effective treatment strategies are lacking especially in adults (Bulik, Berkman, Brownley, Sedway, & Lohr, 2007). Furthermore, AN has one of the highest mortality rates of all psychiatric disorders (Chesney, Goodwin, & Fazel, 2014). Therefore, an urgent need exists for improved understanding of pathophysiology and etiology of AN to identify effective treatment targets. A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) has identified the first genomic locus associated with AN risk, and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based genetic correlations suggest that AN has both psychiatric and metabolic components. More specifically, a significant positive genetic correlation between AN and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol has been reported (Duncan et al., 2017). A second larger GWAS has augmented these findings showing significant genetic correlations with anthropometric, metabolic, and glycemic traits (Watson, personal communication). Likewise, decades of clinical research provide evidence for increased lipid concentrations in patients with AN, mirroring the recently-reported significant genetic correlations (Klinefelter, 1965).

Although several studies have investigated lipid concentrations in AN, the results have been inconsistent as evidence for both increased and decreased lipid concentrations have been reported in AN compared with healthy control participants (HC) (Feillet et al., 2000; Haluzík et al., 1999a; Haluzík, Papezová, Nedvídková, & Kábrt, 1999b; Shih et al., 2016). Most studies published to date had small sample sizes, and only a few investigated individuals with AN longitudinally to measure the potential normalization of lipid concentrations after weight restoration and/or recovery. Overall, a clear consensus is absent, the distinction between state and trait effects is unclear, and the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. A normalization of lipid profiles after weight restoration would point towards effects of starvation (state effect) whereas similar lipid concentrations before and after weight restoration may suggest a more fundamental lipid dysregulation (trait effect) in individuals with AN. The differentiation of state and trait is also clinically relevant as it can prevent unnecessary aggressive treatment of symptoms which are state-dependent and likely to normalize with remission. Based on several guidelines, including the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP, 2001), there is no indication for lipid-lowering pharmacological treatment in AN due to lipid concentrations, typical age of the patients with AN, their predominant gender, their protective HDL levels, and their lack of concomitant cardiovascular risk factors (Isner, Roberts, Heymsfield, & Yager, 1985; Matzkin, Slobodianik, Pallaro, Bello, & Geissler, 2007).

The investigation of lipid concentrations in AN has the potential to advance our understanding of AN and may reveal underlying pathophysiology by determining whether the observed alteration in lipid concentrations is a consequence of starvation and/or part of the disorder mechanism. Further explication of the role of lipids in AN could potentially enhance identification of molecular targets for drug development and improve treatment options. Therefore, we systematically reviewed and meta-analyzed case-control studies with the aim of critically examining the state of knowledge on lipid concentrations in individuals with AN compared with HC before and after partial weight restoration.

Methods

This report was completed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). Methods of analysis and inclusion criteria were specified in advance and documented in a protocol on international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with registration number: CRD42017078014. The a priori PROSPERO protocol was updated once to match the development of the systematic review. All changes and updates are publicly available and accepted by PROSPERO. This systematic review has been constructed according to the following PICO:

Population: individuals with AN

Intervention/indicator: blood tests or other biochemical measures

Comparison: 1) acutely-ill individuals with AN compared with HC, and 2) AN before and after partial weight restoration following treatment

Outcome: blood lipid profiles

To differentiate between cross-sectional and longitudinal data, we refer to participants at baseline measurement as ‘acutely-ill individuals with AN’, and in follow-up studies, the participants are referred to as ‘after partial weight restoration’ or ‘partially weight-restored’.

Eligibility criteria

All case-control studies measuring plasma and serum lipid concentrations for all age groups in individuals with AN were considered. Acutely-ill individuals and partially weight-restored individuals compared with HC were investigated. Original peer reviewed papers published in English, French, German, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian were included.

Information sources and search strategy

Five databases (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, PsycInfo, and CINAHL) with the following MeSh terms (((anorexia nervosa[MeSH Terms]) OR anorexia nervosa[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((lipids[MeSH Terms]) OR lipid[Title/Abstract]) OR cholesterol[MeSH Terms]) OR cholesterol[Title/Abstract]).” were searched (Supporting Information: Search strategy). Reference lists of key studies were searched manually to retrieve any studies not identified in the primary search. No publication date restrictions were imposed. The last search was run on 17 February 2017.

Study selection

Covidence was used to assess eligibility in an un-blinded standardized manner by a minimum of two reviewers. Title/abstract was screened by AAH, MH, and AMK, full-text articles by AAH and MH. Data were extracted by AAH, EL, and CH. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus and/or contact with the authors of the studies. The final consensual data extraction sheet was compared to the full-text articles by AAH, MH, and CH. Regular supervision and conflict resolution throughout the process was provided by JMS.

Data collection process and data items

Covidence was used for data extraction by AAH and EL. Disagreements between data extractors were resolved by a third author (JMS) and by re-checking original articles. Furthermore, the final data extraction was compared to the original articles by a fourth author (MH). Original study authors were contacted for missing data, and additional un-published author-provided data were obtained. Sample overlap was assessed by juxtaposing author names, sample sizes, comparators, and outcomes. A standard data extraction template for the systematic review was used (Supporting Information: Standard data extraction template).

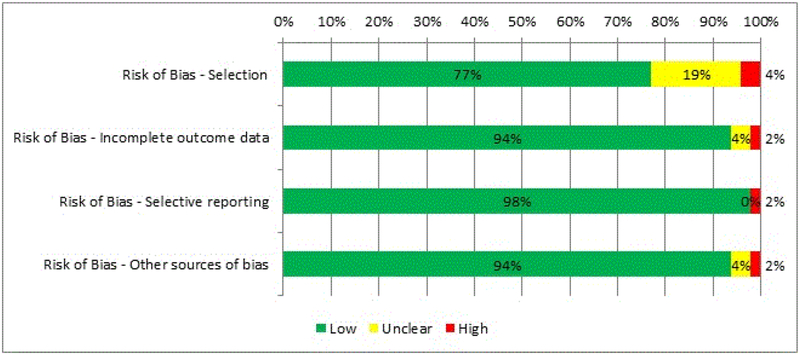

Risk of bias assessment

To ascertain the validity of eligible studies, pairs of reviewers working independently assessed the risk of bias (low/high/unclear) using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool (www.handbook.cochrane.org, chapter 8) in individual studies on four domains: selection; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and other sources. Blinding was, initially, included as a fifth domain but none of the included studies reported on this. Considering the visibility of extreme underweight in acutely-ill individuals with AN blinding of neither patients nor personnel is possible. Therefore, blinding has not been included in the risk of bias assessment in the results in (Supporting Information: Risk of bias).

We observed potential sample overlap in five studies from the Czech Republic. The authors could not rule out data reuse. Therefore, all studies were systematically reviewed, but two were excluded from our meta-analysis (Haluzík et al., 1999a; Haluzikova et al., 2009) due to a smaller sample size compared with (Krizova et al., 2008) and differing age range with (Haluzík et al., 1999b).

Meta-analysis

We performed a meta-analysis in R (version 3.4.3) using the packages ‘metafor’, ‘meta’, and ‘metasens’. The mean differences (MD) between clinical and control group were the primary effect sizes. A fixed-effect model was deemed inappropriate as significant differences were anticipated in procedures and study populations between studies, therefore a random-effects model was performed. The random-effects model assumes that the heterogeneity in the differences between clinical and control groups is due to two components: the within-study and between-study variation explained by clinical and methodological differences among the included studies. We used a restricted maximum-likelihood estimator to calculate heterogeneity. In our meta-analyses, we assumed an independent working correlation between longitudinal data points. Missing values (e.g., BMI) were calculated if possible. BMI was calculated from average weight and height (Castillo, Scheen, Lefebvre, & Luyckx, 1985; Mordasini, Klose, Heuck, Augustin, & Greten, 1977). Subgroup analysis of AN subtypes was statistically underpowered (n=10) because only one study investigated binge-eating/purging subtype (Case, Lemieux, Kennedy, & Lewis, 1999; Sanchez-Muniz, Marcos, & Varela, 1991; Weinbrenner et al., 2004).

After repeated and unsuccessful attempts to contact authors, 15 studies were excluded from the meta-analysis (PRISMA) due to missing weight, height, or BMI values (Arden, Weiselberg, Nussbaum, Shenker, & Jacobson, 1990; Blickle et al., 1984; Casper, Pandey, Jaspan, & Rubenstein, 1988; Crisp, Blendis, & Pawan, 1968; Rigaud, 1999; Stephan, Ghandour, Reville, de Laharpe, & Thierry, 1977; Stephan, Schlienger, Blickle, & de Laharpe, 1982; Umeki, 1988), implausible results (Miyai, Yamamoto, Azukizawa, Ishibashi, & Kumahara, 1975; Ohwada, Hotta, Oikawa, & Takano, 2006; Rigaud, 1999; Terra et al., 2013), extreme outliers (Case et al., 1999), and potential sample overlap (Haluzík et al., 1999a; Haluzikova et al., 2009). Additionally, one study (Curatola et al., 2004) reported low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol values as a ratio and was therefore excluded.

Publication bias or small study effects

Meta-analysing results from different studies should diminish both bias and uncertainty of the overall estimate; however, sometimes this does not hold true as published studies may be a biased selection of the evidence (Nieminen, Rucker, Miettunen, Carpenter, & Schumacher, 2007). To detect potential publication bias, we inspected funnel plots visually (Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997) and quantified their asymmetry by statistical tests using three different approaches: the Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation test (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994); Egger’s linear regression test (Egger et al., 1997); and a weighted linear regression by Thompson and Sharp which allows for between-study heterogeneity (Thompson & Sharp, 1999). Significance of these test statistics (p < .05) indicates asymmetric funnel plots and suggests publication bias or small study effects. In case of suggestive small study effects, we fitted a Copas selection model to adjust our meta-analysis for these effects.

Copas selection model

The Copas selection model to correct for potential selection bias comprises two components: a model for the meta-analyzed effect and a model estimating the probability that study k is selected for publication. The correlation parameter ⍴ between these two components indicates the extent of publication bias with larger correlations suggesting more extreme effects have been selected for publication (Copas, 1999; Copas & Shi, 2000, 2001). We used the R package ‘metasens’ which fits the Copas selection model repeatedly over a grid of tuning parameters γ0 and γ1 and creates a standardised output: a) a funnel plot; b) a contour plot; c) a treatment effect plot; and d) a p-value plot.

Meta-regression and stratified subgroup analysis

We detected extensive heterogeneity across the studies. The heterogeneity observed in a meta-analysis can be partially systematic and related to clinical study-level variables (i.e., moderators), such as age or AN subtype. In secondary analyses, potential moderators were therefore explored in stratified subgroup analyses, such as AN subtype, or via meta-regression analyses, including mean age, the time period of follow-up for longitudinal studies, duration of illness, body mass index and its differences between cases and controls. Mixed effects models allow for within-study and between-study variation and were therefore the most appropriate model indicated by the large heterogeneity estimates detected in our primary meta-analyses. We used a restricted maximum-likelihood estimator to calculate the heterogeneity included in the R package ‘meta’.

Results

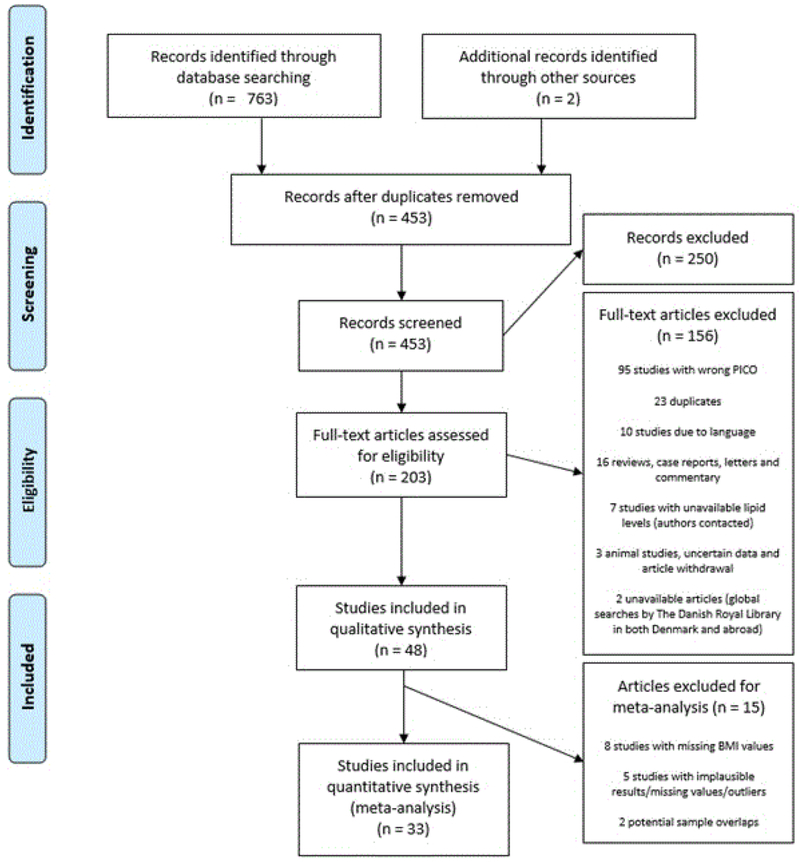

The search identified 765 studies from the following sources: PubMed (283 studies), Embase (178 studies), Scopus (224 studies), PsycInfo (57 studies), and CINAHL (21 studies), and other sources (2 studies). After screening and assessment of abstracts and full texts, 48 studies remained. Selection process is described in detail in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection process. PICO: population, intervention, comparator and outcomes. BMI: body mass index.

Lipid concentrations in acutely-ill and partially weight-recovered individuals with AN compared with HC

Systematic review

Forty-eight studies of lipid concentrations in individuals with AN were included in the systematic review, with a total of 3,037 participants (1,572 individuals with AN and 1,465 HC; Table 1). All 48 studies were observational, used a case-control design, and has an overall low risk of bias (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Overview of included studies.

| Weight restoration | First author, year | Participants (n) | BMI [kg/m2] Mean (SD)† | Age [years] Mean (SD)† | Diagnostic manual | Illness duration [years] Mean (SD) | Country | Blood sample type | Fasting before blood withdrawal [hours] | Lipid results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN | HC | AN | HC | AN | HC | AN compared with HC | |||||||

| X | (Shih et al., 2016) | 30 | 36 | 14.3 (1.4) | 20.9 (0.9) | 22.2 (4.8) | 19.9 (1.6) | DSM-IV | 3.0 | European (Price Foundation) | Plasma | N/A |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: sig. increased LDL: NS increased TG: NS decreased |

| (Víctor et al., 2015) | 24 | 36 | 16.3 (1.6) | 20.9 (1.4) | 22.4 (6.8) | 24.3 (3.4) | DSM-IV-TR | N/A confirmed by author | Spain | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: sig. increased LDL: NS increased TG: NS increased Apo a1: NS decreased Apo B: NS decreased |

|

| (Omodei et al., 2015) | 15 | 20 | 16.0 (1.5) | 20.4 (3.1) | 19.7 (3.9) | 22.6 (3.7) | DSM-5 | N/A | Italy | Serum | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS decreased |

|

| (Barja-Fernandez et al., 2015) | 30 | 50 | 16.5 (1.3) | 21.6 (1.5) | 28.1 (9.4) | 28.9 (6.2) | DSM-IV-TR | N/A | Spain | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: sig. increased LDL: sig. increased TG: sig. decreased |

|

| (Víctor et al., 2014) | 20 | 20 | 15.3 (0.9) | 20.6 (0.6) | 21.2 (5.9) | 23.6 (2.8) | DSM-IV-TR | N/A - confirmed by author | Spain | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: NS increased LDL: NS increased TG: NS increased Apo a1: NS decreased Apo B: NS decreased |

|

| (Terra et al., 2013) | 28 | 33 | 16.8 (0.2) | 21.8 (0.3) | 27.4 (1.4) | 32.6 (1.3) | DSM-IV | 8.3 (1.4) | Spain | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: NS increased LDL: NS increased TG: NS decreased |

|

| X | (Kavalkova et al., 2012) | 18 | 16 | 15.6 (1.2) | 21.8 (2.0) | 24.4 (5.1) | 22.7 (3.0) | DSM-IV | 9.0 (1.8) | Czech Republic | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: NS decreased LDL: NS increased TG: sig. increased |

| (Karczewska-Kupczewska et al., 2010) | 21 | 24 | 15.6 (1.6) | 21.0 (2.1) | 22.4 (5.2) | 24.1 (4.8) | DSM-IV-TR | 1.4 (0.9) | Poland | Serum | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS decreased HDL: NS decreased LDL: NS decreased TG: NS increased FFA: sig. decreased |

|

| (Brick et al., 2010) | 11 | 11 | 16.6 (1.7) | 22.3 (2.0) | 31.7 (7.3) | 30.5 (7.6) | DSM-IV | N/A | USA | Plasma | 12.0 | FFA: NS increased | |

| X | (Uzum et al., 2009) | 19 | 19 | 14.6 (2.0) | 17.6 (0.9) | 19.3 (3.6) | 24.0 (2.8) | DSM-IV | N/A | Turkey | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS decreased LDL: sig. increased TG: NS increased |

| X | (Rigaud et al., 2009) | 120 | 119 | 13.5 (1.5) | 15.8 (1.8) | 26.0 (9.0) | 26.9 (7.0) | DSM-IV | 2.0–27.0 [range] | France | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. decreased HDL: NS decreased LDL: NS increased TG: sig. increased Apo a1: sig. decreased Apo B: NS increased |

| (Haluzikova et al., 2009) | 19 | 16 | 15.9 (1.4) | 22.9 (1.6) | 25.0 (5.8) | 24.7 (2.4) | DSM-IV | N/A | Czech Republic | Serum | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased TG: NS decreased |

|

| (Vignini et al., 2008) | 25 | 20 | 16.2 (0.9) | 21.9 (2.1) | 25.6 (3.6) | 27.5 (2.5) | DSM-IV | 3.7 (0.8) | Italy | Plasma | Not specified |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS decreased TG: NS increased |

|

| (Storch et al., 2008) | 16 | 16 | 13.9 (2.0) | 22.5 (2.5) | 24.1 (6.0) | 24.0 (5.7) | DSM-IV | 6.2 (7.4) | Germany | Blood, unspecified | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: NS decreased LDL: NS decreased TG: NS increased |

|

| X | (Nova et al., 2008) | 14 | 15 | 15.2 (1.7) | 20.2 (1.3) | 15.1 (2.6) | 15.1 (1.4) | DSM-IV | 0.8 (0.5) | Spain | Serum | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: sig. decreased LDL: NS increased VLDL: NS decreased TG: NS decreased |

| (Krizova et al., 2008) | 28 | 38 | 15.7 (1.9) | 22.3 (2.5) | N/A | N/A | DSM-IV | N/A | Czech Republic | Serum | 8.0 | Tot. chol.: NS decreased | |

| X | (Matzkin et al., 2007) | 30 | 30 | 17.0 (2.0) | 21.0 (2.1) | 23.5 (8.7) | 23.6 (5.1) | DSM-IV | 6.3 (6.5) | Argentina | Plasma | 9.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS decreased LDL: sig. increased TG: sig. increased Apo a1: NS increased Apo B: sig. increased |

| (Lawson et al., 2007) | 85 | 28 | 16.9 (0.2) | 21.0 (0.3) | 25.6 (0.8) | 24.2 (0.6) | DSM-IV | N/A | USA | Plasma | N/A |

HDL: sig. increased LDL: NS decreased |

|

| X | (Heilbronn et al., 2007) | 10 | 7 | 16.4 (1.3) | 19.5 (1.1) | 22.0 (4.0) | 27.0 (3.0) | DSM-IV | 3.0 | Australia | Plasma | 10.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: NS increased LDL: NS increased TG: NS decreased FFA: sig. decreased |

| X | (Ohwada et al., 2006) | 24 | 5 | 14.7 (10.8) | 21.8 (2.7) | 22.0 (2.5) | 24.0 (2.1) | DSM-IV | 2.7 (0.9) | Japan | Serum | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: sig. increased LDL: sig. increased TG: NS increased FFA: NS increased Apo a1: sig. increased Apo B: sig. increased |

| X | (Misra et al., 2006) | 23 | 20 | 16.7 (1.2) | 21.9 (3.6) | 16.2 (1.6) | 15.4 (1.8) | DSM-IV | 0.7 (0.9) | USA | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: sig. increased LDL: NS increased TG: sig. decreased Apo B: sig. increased |

| (Matzkin et al., 2006) | 308 | 216 | 16.6 (2.0) | 20.2 (3.2) | 17.3 (3.8) | 18.1 (4.7) | DSM-IV | N/A | Argentina | Blood, unspecified | 11.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: sig. increased LDL: sig. increased TG: NS decreased |

|

| (Zák et al., 2005) | 16 | 25 | 15.4 (2.8) | 20.9 (2.0) | 22.4 (1.1) | 22.5 (3.0) | DSM-IV | 3.1 (2.4) | Czech Republic | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: sig. increased LDL: NS increased TG: sig. increased FFA: sig. increased Apo a1: NS increased Apo B: NS increased |

|

| (Weinbrenner et al., 2004) | 58 | 58 | 15.3 (1.5) | 22.2 (1.7) | 24.2 | 25.5 | DSM-IV | 0.1–3.5 [range] | Germany | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS increased LDL: sig. increased VLDL: NS increased TG: NS decreased FFA: NS decreased Apo B: NS increased |

|

| (Curatola et al., 2004) | 30 | 30 | 16.5 (3.4) | 21.8 (2.3) | 23.2 (4.7) | 23.8 (3.7) | DSM-IV | N/A | Italy | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS decreased HDL: NS increased LDL: sig. decreased TG: NS increased |

|

| (Delporte, Brichard, Hermans, Beguin, & Lambert, 2003) | 26 | 24 | 14.3 (2.0) | 22.4 (3.4) | 22.7 (8.7) | 21.2 (4.9) | DSM-IV | N/A | Belgium | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS increased LDL: NS increased TG: NS increased |

|

| (Boland, Beguin, Zech, Desager, & Lambert, 2001) | 75 | 95 | 14.0 (2.1) | 20.3 (2.1) | 21.5 (2.3) | 21.4 (2.3) | DSM-IV | 0.5–25.0 | Belgium | Plasma | Not specified |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS increased LDL: sig. increased TG: NS increased |

|

| (Rigaud, Hassid, Meulemans, Poupard, & Boulier, 2000) | 16 | 16 | 13.6 (1.1) | 21.2 (1.7) | 25.2 (3.9) | 23.8 (4.1) | DSM-IV | N/A | France | Serum | 10.0 | FFA: sig. increased | |

| X | (Rigaud, 1999) | 148 | 150 | %IBW 65 (6) | %IBW 104 (5) | 26.0 (9.0) | 26.0 (7.0) | N/A | 1.0–25.0 | France | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. decreased HDL: NS decreased LDL: sig. increased VLDL: sig. increased TG: NS increased Apo a1: NS decreased Apo B: NS increased |

| (Haluzík et al., 1999a) | 17 | 17 | 15.2 (3.1) | 24.9 (16.4) | 24.1 (3.8) | 50.1 (8.9) | DSM-IV | N/A | Czech Republic | Serum | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS decreased TG: NS decreased |

|

| X | (Haluzík et al., 1999b) | 11 | 11 | 15.4 (3.2) | 20.3 (1.7) | 23.7 (3.1) | 24.3 (3.2) | DSM-IV | N/A | Czech Republic | Serum | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased TG: NS decreased |

| (Case et al., 1999) | 9 | 10 | 17.4 (0.7) | 22.9 (1.2) | 30.1 (6.1) | 29.8 (5.6) | DSM-IV | 8.4 (3.0) | Canada | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS increased LDL: sig. increased VLDL: NS increased TG: sig. increased Apo a1: sig. increased Apo B: sig. increased |

|

| X | (Lejoyeux et al., 1996) | 15 | 15 | 14.6 (1.7) | 18.6 (2.6) | 17.8 (2.4) | 17.8 (2.2) | DSM-III-R | 1.5 (0.8) | France | Plasma | 8.0 | Tot. chol.: NS increased |

| (Uhe et al., 1992) | 10 | 6 | 14.7 (2.2) | 21.0 (1.7) | 20.1 (6.6) | 20.9 (5.4) | N/A | N/A | Australia | Plasma | 8.0 | Tot. chol.: sig. increased | |

| (Sanchez-Muniz et al., 1991)‡ | 12 | 7 | 15.0 (0.7) | 21.6 (7.4) | 14.4 (1.4) | 15.0 (0.8) | Feighner’s criteria | N/A | Spain | Serum | 13.5 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased TG: sig. increased Apo B: sig. increased |

|

| (Franssila-Kallunki et al., 1991) | 11 | 8 | 13.6 (1.3) | 21.8 (2.5) | 24.5 (9.6) | 26.3 (7.1) | DSM-III | N/A | Finland | Plasma | 12.0 |

Tot. chol.: NS decreased TG: NS increased FFA: NS decreased |

|

| X | (Arden et al., 1990) | 16 | 16 | %IBW 79 | %IBW 102 | 17.3 | 15 | DSM-III-R | 2.0 | USA | Plasma | Not specified |

Tot. chol.: NS increased HDL: NS increased LDL: NS increased TG: NS decreased Apo a1: NS increased Apo B: NS increased |

| X | (Umeki, 1988) | 27 | 28 | N/A | N/A | 19.0 (3.0) | 22.0 (4.0) | Feighner’s criteria | N/A | Japan | Serum | 8.0 | Tot. chol.: sig. increased |

| (De Marinis et al., 1988) | 9 | 13 | 15.2 (2.0) | 19.5 (1.3) | 19.1 (4.6) | 24.2 (1.8) | DSM-III-R | N/A | Italy | Plasma | 8.0 | FFA: no difference (identical numerical values) | |

| X | (Casper et al., 1988) | 7 | 14 | N/A | %IBW 102.1 (6.5) | 26.9 (6.4) | 24.3 (2.9) | Feighner’s criteria | N/A | USA | Plasma | 8.0 | FFA: sig. increased |

| (Castillo et al., 1985) | 6 | 6 | %IBW 73.8 (9.6) | %IBW 103.1 (4.4) | 27.3 (12.0) | 22.6 (3.0) | N/A | N/A | Belgium | Plasma | 8.0 | FFA: NS increased | |

| (Blickle et al., 1984) | 14 | 14 | %IBW 67.0 (2.0) | %IBW 97.1 (2.7) | 24.6 (6.0) | 25 (7.1) | N/A | 5.9 (1.8) | France | Plasma | 8.0 | FFA: NS increased | |

| (Stephan et al., 1982) | 35 | 19 | N/A | N/A | 23.0 (6.5) | 24.7 (7.0) | Feighner’s criteria | >0.5 | France | Plasma | N/A |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased FFA: sig. increased |

|

| (Stephan et al., 1977) | 11 | 8 | N/A | N/A | 21.3 (6.0) | 23.2 (1.2) | N/A | 1.8 | France | Serum | 13.5 |

Tot. chol.: NS increased TG: NS increased FFA: NS increased |

|

| X | (Mordasini et al., 1977) | 18 | 15 | 13.1 | 19.7 | 22.0 | 23.6 | N/A | 2.3 | Germany | Plasma | 8.0 |

Tot. chol.: sig. increased HDL: NS decreased LDL: sig. increased VLDL: sig. increased TG: NS increased |

| (Miyai et al., 1975) | 16 | 16 | 14.7 (1.7) | N/A | 20.1 (2.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Japan | Serum | 8.0 | Tot. chol.: NS increased | |

| (Nestel, 1974) | 4 | 12 | 16.3 (0.8) | N/A | 15.0 (0.7) | N/A | N/A | 0.8 (0.2) | Australia | Plasma | N/A | Tot. chol.: sig. increased | |

| X | (Crisp et al., 1968) | 37 | 37 | N/A | N/A | 20.4 (4.7) | 20.4 (4.7) | N/A | N/A | England | Serum | 8.0 | Tot. chol.: sig. increased |

Notes: Tot. chol.: total cholesterol. LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. VLDL: very-low density lipoprotein cholesterol. TG: triglycerides. FFA: free fatty acids. Apo a1: apolipoprotein a1. Apo B: apolipoprotein B. Sig.: significant. NS: non-significant. Not reported (author confirmed): the authors were contacted for further information, but data were unavailable. NA: not applicable. IBW: Ideal body weight. SBW: Standard body weight. USA: United States of America.

SD unless otherwise stated.

Sanchez-Muniz et al. stratified patients by age, only one group is included in this table and the systematic review, but both were included in the meta-analyses.

Figure 2.

Percent of studies exhibiting degrees of bias. Included studies were assessed for risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool focused on four domains. Each item was rated with ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’ risk of bias.

Total sample sizes ranged from 12 to 524 participants. Mean age of participants with AN and HC ranged from 14.4 to 31.7 years and 15.0 to 50.1 years, respectively. Mean BMI of patients with AN and controls ranged from 13.5 to 17.4 kg/m2 and 22.4 to 24.9 kg/m2, respectively. Only female participants were included in the studies except for two studies (Curatola et al., 2004; Rigaud, Tallonneau, & Verges, 2009) with 83.3% and 96% female participants, respectively. Lipid concentrations were comparable across plasma and serum, although, different laboratory methods were used. Fasting status reported as ‘overnight’ was assumed to last eight hours, and fasting reported in ranges were reported as a mean in Table 1. The diagnosis of AN was classified according to DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) in one study, DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) in 26 studies, DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) in four studies, DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) in three studies, DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) in one study, Feighner’s criteria (Feighner et al., 1972) in four studies, whereas diagnostic criteria were not specified in the remaining nine studies. In the nine studies with unpecified diagnostic criteria (Blickle et al., 1984; Castillo et al., 1985; Crisp et al., 1968; Miyai et al., 1975; Mordasini et al., 1977; Nestel, 1974; Rigaud, 1999; Stephan et al., 1977; Uhe et al., 1992), the study participants had low BMIs (<16.3 kg/m2), low percentage of ideal body weight (<73.8%), confirmation of the AN diagnosis by psychiatric examination, history of food aversion, secondary amenorrhea, and/or rapid weight loss. Mean cholesterol concentrations were reported in 41 studies, HDL in 28 studies, LDL in 26 studies, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol in five studies, triglycerides (TG) in 32 studies, free fatty acids (FFA) in 14 studies, (apolipoprotein a1) Apo a1 in nine studies, and (apolipoprotein B) Apo B in 12 studies (Table 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Systematic review results.

| Tot. chol. | HDL | LDL | VLDL | TG | FFA | Apo a1 | Apo B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significantly increased, n (%) | 21 (51%) | 8 (29%) | 10 (38%) | 2 (40%) | 6 (19%) | 4 (29%) | 2 (14%) | 5 (42%) |

| Significantly decreased, n (%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 2 (14%) | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Non-significant results, % | 44% | 68% | 58% | 60% | 75% | 57% | 43% | 58% |

Notes: Significance and trends of the lipid outcomes in cross-sectional studies comparing acutely-ill individuals with anorexia nervosa with healthy control participants.

Meta-analysis

In addition to the systematic review, we also performed separate meta-analyses for total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, VLDL, TG, FFA, Apo a1, and Apo B concentrations to compare: (1) either acutely-ill or partially weight-restored individuals with AN with HC; and (2) AN patients before and after partial weight restoration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Meta-analyses results.

| Meta-analysis results from studies comparing acutely-ill individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) with healthy control participants (HC). | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid | k | AN-pre (n) | HC (n) | MD (mg/dL) | 95% CI | P-value | I2 | τ2 | P-value for heterogeneity | Reference value (mg/dL) |

| Total chol. | 31 | 1054 | 1026 | 22.7 | 12.5, 33.0 | <0.0001 | 87% | 703.5 | <0.01 | 125-200 |

| HDL | 24 | 881 | 880 | 3.4 | 0.30, 6.95 | 0.03 | 83% | 44.2 | <0.01 | >50 (women) |

| LDL | 20 | 776 | 852 | 12.2 | 4.4, 20.1 | 0.002 | 79% | 245.0 | <0.01 | <100 |

| VLDL | 3 | 90 | 88 | 4.9 | −3.7, 13.6 | 0.270 | 90% | 53.7 | <0.01 | 2-30 |

| TG | 22 | 680 | 769 | 8.1 | 1.7, 14.5 | 0.014 | 63% | 141.2 | <0.01 | <90 |

| FFA† | 8 | 147 | 155 | 1.3 | −4.0, 6.5 | 0.640 | 87% | 46.8 | <0.01 | 0.0-27.8 |

| Apo a1† | 5 | 210 | 230 | −1.5 | −20.5, 17.5 | 0.880 | 88% | 393.1 | <0.01 | >140 |

| Apo B† | 10 | 320 | 333 | 11.8 | 2.3, 21.2 | 0.020 | 76% | 178.0 | <0.01 | <130 |

| Meta-analysis results of the studies comparing partially weight-restored individuals with AN with HC. | ||||||||||

| Lipid | k | AN-post (n) | HC (n) | MD (mg/dL) | 95% CI | P-value | I2 | τ2 | P-value for heterogeneity | Reference value (mg/dL) |

| Total chol. | 11 | 212 | 303 | 14.8 | 2.0, 27.5 | 0.020 | 79% | 307.0 | <0.01 | 125-200 |

| HDL | 7 | 122 | 143 | 0.5 | −3.5, 4.5 | 0.810 | 26% | 9.9 | 0.23 | >50 (women) |

| LDL | 8 | 128 | 158 | 19.0 | 5.9, 32.0 | 0.005 | 76% | 242.0 | <0.01 | <100 |

| TG | 8 | 134 | 154 | 3.3 | −16.9, 23.0 | 0.750 | 76% | 625.0 | <0.01 | <90 |

| Meta-analysis results of the longitudinal studies of lipid concentrations in acutely-ill individuals with AN compared with weight-restored individuals with AN. | ||||||||||

| Lipid | k | AN-post (n) | AN-pre (n) | MD (mg/dL) | 95% CI | P-value | I2 | τ2 | P-value for heterogeneity | Reference value (mg/dL) |

| Total chol. | 10 | 191 | 278 | −20.05 | −42.3, 2.2 | 0.078 | 86% | 1044.3 | <0.01 | 125-200 |

| HDL | 6 | 101 | 114 | 2.56 | −3.2, 8.3 | 0.386 | 43% | 20.8 | 0.12 | >50 (women) |

| LDL | 7 | 107 | 132 | −2.4 | −10.8, 6.0 | 0.576 | 33% | 26.4 | 0.17 | <100 |

Notes: AN: anorexia nervosa. AN-pre: individuals with AN before weight restoration (acutely-ill AN). AN-post: individuals with AN after partial weight restoration. HC: healthy control participants. MD: mean difference. CI: confidence interval. k: number of studies. Tot. chol.: total cholesterol. HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. VLDL: very-low density lipoprotein cholesterol. TG: triglycerides. FFA: free fatty acids. Apo a1: apolipoprotein a1. Apo B: apolipoprotein B. Lipid reference values for total chol., HDL, LDL, and TG: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/high-blood-cholesterol (Danish: www.sundhed.dk,

www.reference.medscape.com and www.mayomedicallaboratories.com). For VLDL, FFA, Apo a1, and Apo B ≤1 study was eligible for meta-analysis in studies comparing partially weight-restored individuals with AN with HC, and in studies comparing longitudinal studies of lipid concentrations in acutely-ill individuals with AN with HC.

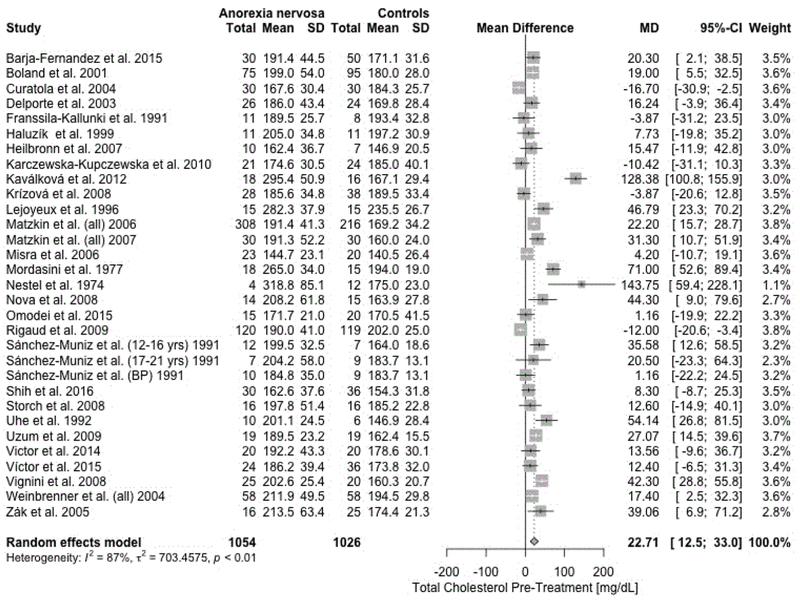

A random-effects meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant positive mean difference (MD) for total cholesterol (MD = 22.7 mg/dL, 95% CI = 12.5, 33.0; p < .0001 ; Figure 3), HDL (MD = 3.4 mg/dL, 95% CI = 0.30, 6.95; p = .03), LDL (MD = 12.2 mg/dL, 95% CI = 4.4, 20.1; p = .002), TG (MD = 8.1 mg/dL, 95% CI = 1.7, 14.5; p = .014), and Apo B (MD = 11.8 mg/dL, 95% CI = 2.2, 21.2; p = .02) comparing acutely-ill individuals with AN with HC. In summary, we found evidence for significantly higher lipid concentrations in individuals with AN compared with HC. Forest plots for all outcomes are presented in Supporting Information (Figures S1–S7). As only one study (Sanchez-Muniz et al., 1991) investigated the binge-eating/purging subtype of AN, the subgroup analysis therefore was limited (Supporting Information Figure S8). The subtype analysis examining the different diagnostic criteria for AN showed that studies not reporting any diagnostic criteria found large mean differences compared with the rest (Supporting Information Figure S9). These subgroup analyses showed a significant difference between diagnostic criteria (p<.0001), but not between the different subtypes (p=0.27). All results from the subgroup analyses of subtype and diagnostic criteria are presented for acutely-ill/pre-treatment AN compared with HC (Supporting Information Table S1).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for total cholesterol concentrations in acutely-ill individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) compared with healthy control participants. SD: standard deviation. MD: mean difference. CI: confidence interval.

Heterogeneity across studies was statistically significant for every outcome (Table 3). Visual inspection of the funnel plots for each outcome suggested some asymmetry. We fitted a Copas selection model for the pre-treatment total cholesterol meta-analysis between acutely-ill individuals AN and HC because small study effects were indicated by a significant Thompson and Sharp test (p = .008). The Copas selection model analysis did not overturn the conclusion of the original meta-analysis, although, the adjusted estimate of 14.0 mg/dL (95% CI = 6.8, 21.2; p < .0001 ) with an estimated selection probability of 59% and 13 potentially unpublished studies is about half of the random effects model estimate with 22.7 mg/dL (95% CI = 12.5, 33.0) (Supporting Information Figure S10a–d).

We then conducted a meta-regression to examine the association of the proposed moderators, BMI, the difference in BMI between cases and controls, age of individuals with AN, fasting period, duration of illness, and duration of follow-up with the MDs in lipid concentrations (Supporting Information Figures S11–S22). The results from the meta-regression for the acutely-ill individuals with AN compared with HC are reported in Table 4. Additional results are reported in Supporting Information Table S2 & S3.

Table 4.

Meta-regression results for potential moderators on lipid concentration differences in acutely-ill individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) compared with healthy control participants (HC).

| Analysis | k | beta | 95% CI | P-value | Moderator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | 31 | −2.13 | −9.92, 5.66 | 0.59 | BMI mean AN pre |

| 30 | −2.27 | −8.34, 3.81 | 0.46 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 16 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 | 0.4 | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 30 | −1.43 | −4.66, 1.80 | 0.39 | Age | |

| 26 | −0.01 | −5.55, 5.52 | 1.00 | Fasting | |

| HDL | 24 | 2.72 | 0.46,4.98 | 0.02* | BMI mean AN pre |

| 24 | −0.35 | 2.52, 1.82 | 0.75 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 14 | −0.002 | −0.006, 0.002 | 0.35 | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 24 | 0.36 | −0.67 1.39 | 0.49 | Age | |

| 18 | −1.22 | −3.27, 0.84 | 0.25 | Fasting | |

| LDL | 20 | −5.77 | −11.68, 0.15 | 0.06 | BMI mean AN pre |

| 20 | −0.78 | −5.72, 4.17 | 0.76 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 12 | −0.01 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0.41 | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 20 | −2.12 | −4.57, 0.33 | 0.09 | Age | |

| 15 | −2.63 | −8.06, 2.81 | 0.34 | Fasting | |

| VLDL | 3 | −5.81 | −8.38,−3.24 | <.01* | BMI mean AN pre |

| 3 | −3.6 | −16.67, 9.46 | 0.59 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 3 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.03 | <.01* | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 3 | 0.64 | −2.30, 3.59 | 0.67 | Age | |

| Fasting | |||||

| TG | 22 | −2.64 | −7.04,1.76 | 0.24 | BMI mean AN pre |

| 22 | 1.45 | 2.34, 5.25 | 0.45 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 13 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.02 | <.01* | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 22 | 0.81 | −0.98, 2.61 | 0.37 | Age | |

| 18 | 3.54 | 0.58, 6.49 | 0.02* | Fasting | |

| FFA | 8 | −2.46 | −7.32,2.40 | 0.32 | BMI mean AN pre |

| 7 | −1.58 | −5.16, 2.01 | 0.39 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 3 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.04 | 0.3 | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 8 | 0.57 | −1.18, 2.33 | 0.52 | Age | |

| 8 | −0.25 | −3.64, 3.15 | 0.89 | Fasting | |

| Apo A1 | 5 | 9.18 | −7.08, 25.44 | 0.27 | BMI mean AN pre |

| 5 | −4.76 | −22.37, 12.84 | 0.6 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 3 | −0.02 | −0.07, 0.04 | 0.56 | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 5 | −1.07 | −14.38, 12.24 | 0.87 | Age | |

| 5 | −9.7 | −13.02, −6.38 | <.01* | Fasting | |

| Apo B | 10 | 1.39 | −4.95,7.73 | 0.67 | BMI mean AN pre |

| 10 | −1.06 | −7.20, 5.08 | 0.73 | BMI diff AN-pre vs HC | |

| 5 | −0.003 | −0.020, 0.015 | 0.78 | Mean disease duration | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||

| 10 | −1.80 | −4.35, 0.75 | 0.17 | Age | |

| 10 | −2.86 | −6.86, 1.14 | 0.16 | Fasting |

Notes : AN: Anorexia nervosa. AN-pre: individuals with anorexia nervosa before weight restoration (acutely-ill AN). HC: healthy control participants. The P-value shows if the potential moderators body mass index (BMI), the difference in BMI between AN and HC, age of individuals with AN, fasting period, duration of illness, and duration of follow-up, are associated with the mean difference before treatment. Significant results marked with *. k: number of studies. CI: confidence interval. HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. VLDL: very-low density lipoprotein cholesterol. TG: triglycerides. FFA: free fatty acids. Apo a1: apolipoprotein a1. Apo B: apolipoprotein B.

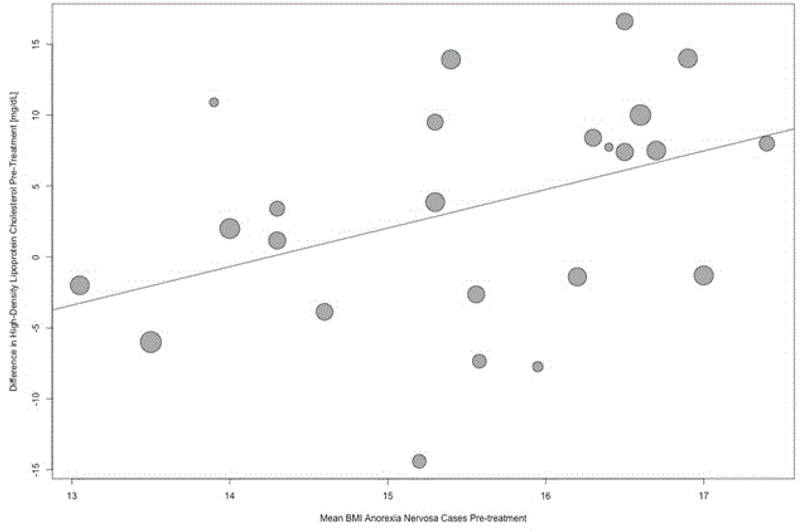

Our analyses revealed a significant positive association of HDL with BMI (β = 2.7, 95% CI = 0.5, 5.0; p = .02, Figure 4) in acutely-ill AN patients. Our analyses also showed a significant negative association of VLDL with BMI (β = −5.8, 95% CI = 8.34, 3.2; p < .01; Supporting Information Figure S11), however, only three studies on VLDL were eligible for inclusion in the meta-regression analysis, rendering our analysis exploratory in nature. None of the other outcomes showed significant associations with BMI. Our analyses also revealed a significant positive association with TG for mean disease duration (β = 0.02; 95% CI = 0.01, 0.02; p < 0.01; Supporting Information Figure S13) and fasting duration (β = 3.5; 95% CI = 0.6, 6.5; p = 0.02). Although, 18 studies contributed to the meta-regression of TG on fasting duration, this analysis must be interpreted cautiously as the majority of the data points are accumulated by the fact that we assumed on average an eight-hour period for overnight fasting (Supporting Information Figure S14).

Figure 4.

Bubble plot. Meta-regression examining the association of the moderator BMI with the mean differences in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol between acutely-ill individuals with anorexia nervosa and healthy control participants. Bubble size is inversely proportional to the variance of the estimated mean difference. This means bubbles are sized according to the precision of each estimate with larger bubble for more precise estimates.

Following partial weight restoration, total cholesterol (MD = 14.8 mg/dL, 95% CI = 2.0, 27.5; p = .02; Supporting Information Figure S23) and LDL (MD = 19.0 mg/dL, 95% CI = 5.9, 32.0; p = .005; Supporting Information Figure S25) were still significantly higher in individuals with AN when compared with HC. Meta-analyses for VLDL (k = 1), FFA (k = 1), Apo a1 (k = 0), and Apo B (k = 0) could not be carried out due to limited number of studies. Heterogeneity was significant for total cholesterol, LDL, and TG, but not for HDL (Table 3). None of the formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry were significant, indicating no small study effects (Supporting Information Table S4), and no meta-regression was significant for any of the lipids (Supporting Information Table S2 & S3.

We also performed a subgroup analysis of studies assessing LDL concentrations measured in assays only. The results still show significantly increased LDL concentrations in acutely-ill patients with AN compared to HC (MD = 25.1 mg/dL, 95% CI = 5.2, 45.0; p = .013), partially weight-restored patients with AN compared with HC (MD = 28.4 mg/dL, 95% CI = 15.3, 41.6; p < .0001), and no significant difference when estimating the change of LDL concentrations between partially weight-restored AN and acutely-ill AN (MD = −12.4 mg/dL, 95% CI = −35.4; 10.5; p = .29). No meta-regression for the proposed moderators was significant.

Lipid concentrations before and after partial weight restoration in individuals with AN

Systematic review

Out of the 48 study included, 17 studies (marked with ‘X’ in Table 1) also described lipid profiles in AN before and after partial weight restoration compared with HC. Participants in the groups undergoing weight restoration were followed-up at different timepoints (e.g., 6-week follow-up, 1-year follow-up, weight-recovered AN, and recovered AN). We summarized those by using the term ‘after partial weight restoration’ (Methods). Of the 17 weight restoration studies, there was no significant difference in lipid concentrations in eight (47%) of the studies (Crisp et al., 1968; Haluzík et al., 1999b; Heilbronn, Milner, Kriketos, Russell, & Campbell, 2007; Kavalkova et al., 2012; Misra et al., 2006; Shih et al., 2016; Umeki, 1988; Uzum, Yucel, Omer, Issever, & Ozbey, 2009). One of 17 (6%) studies reported that the lipid profile normalized after weight gain but numerical values were not available (Rigaud et al., 2009). Three of 17 (18%) studies reported significantly increased HDL concentrations after weight gain (Arden et al., 1990; Matzkin et al., 2007; Nova, Lopez-Vidriero, Varela, Casas, & Marcos, 2008), while one study (6%) reported significantly decreased HDL concentrations (Rigaud, 1999). Three of 17 (18%) studies also found significantly decreased total cholesterol concentrations after weight gain (Lejoyeux et al., 1996; Mordasini et al., 1977; Ohwada et al., 2006). Furthermore, significantly decreased LDL concentrations (Rigaud, 1999), significantly decreased TG concentrations (Arden et al., 1990), and significantly increased FFA concentrations (Casper et al., 1988) were found after weight gain treatment in one study each. The review of the literature identified nine additional studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria of comparison to a HC, but due to the longitudinal study design they were included in an additional comparative analysis (Supporting Information, Table S5).

Meta-analysis

Meta-analyses were performed for total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and TG concentrations in individuals with AN before and after partial weight restoration, showing no significant changes in lipid concentrations (Table 3). Meta-analyses for VLDL (k = 1), FFA (k = 1), Apo a1 (k = 0), and Apo B (k = 0) could not be carried out due to the limited number of studies. The forest plots are available in Supporting Information (Figure S27–S30).

Discussion

This systematic review identified 48 studies and found evidence of increased lipid concentrations in individuals with AN during the rapid weight loss phase (acutely-ill AN) compared with HC. Furthermore, some of the increases in lipid concentrations persisted after partial weight restoration. A meta-analysis was carried out for 33 eligible studies and showed significantly increased concentrations of total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and TG in acutely-ill individuals with AN compared with HC, and also significantly increased concentrations of total cholesterol and LDL in partially weight-recovered individuals with AN when compared with HC. No significant differences in lipid concentrations were found in our longitudinal meta-analyses investigating the changes in lipid concentrations in individuals with AN before and after partial weight restoration.

Only the meta-analysis of total cholesterol comparing acutely-ill individuals with AN with HC showed small study effects (e.g., selection bias); however, the adjusted estimate still indicated a significant difference between individuals with AN and HC. The subgroup analyses for AN subtypes pre-treatment was not significant. However, we were unable to meaningfully investigate differences between restricting and binge-eating subtype as only one study sampled participants with the binge-eating/purging subtype. The post-hoc meta-regression found a positive significant association of BMI in acutely-ill individuals with AN and HDL. Higher BMI was associated with a larger MD in HDL in individuals with AN, which is interesting considering recent findings of a positive genetic correlation of HDL cholesterol with AN (Duncan et al., 2017). Additionally, a negative significant association was found between BMI in acutely-ill individuals with AN and VLDL, but due to the small number of studies included (k = 3), this result is exploratory and must be interpretated with caution.

Potential mechanisms

Potential mechanisms behind increased lipid concentrations in individuals with AN have been discussed and suggested in several studies. Since lipid metabolism is complex, the increased lipid concentrations found in AN may be the consequence of multiple causes. For example, it has been proposed that excessive alimentary intake in individuals of AN (i.e., binge-eating/purging AN subtype) may increase lipid concentrations (Feillet et al., 2000). However, the diet of individuals with AN is typically low in total fats (Allen et al., 2013), and therefore unlikely to explain the observed increase in lipid concentrations, although, low dietary lipid intake does not exclude increased absorption. Furthermore, some studies suggest increased absorption of exogenous cholesterol indicated by higher concentrations of the phytosterols campesterol and beta-sitosterol—steroids derived from plants— in individuals with AN (Zák et al., 2005; Zák et al., 2003), and potentially, these changes in absorption may be influenced by alterations in gut microbiota (Glenny, Bulik-Sullivan, Tang, Bulik, & Carroll, 2017; Schwensen, Kan, Treasure, Hoiby, & Sjogren, 2018). Increased endogenous cholesterol synthesis seems to be unlikely in individuals suffering from AN (Feillet et al., 2000; Weinbrenner et al., 2004; Zák et al., 2005; Zák et al., 2003).

Another potential mechanism is the interaction between lipids and hormones. Lipid concentrations are tightly regulated by hormones and very low lipid intake and low energy diet—which is common in AN—can induce hypoinsulinemia, increase insulin sensitivity, and in severe cases may lead to hypoglycaemia. Adipose tissue plays an important role in the regulation of insulin sensitivity, and cross-talk between glucose and lipid metabolism occurs (Saltiel & Kahn, 2001). Additionally, stress increases epinephrine, cortisol, growth hormone (GH), and glucagon, and has been observed in combination with low triiodothyronine (T3) concentrations in AN (Schorr & Miller, 2017). Associations between low T3 and Apo B, HDL, and LDL concentrations may be mediated by the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) in the human liver. It shows significantly higher activity in AN compared with HC (Ohwada et al., 2006). However, high T3 (Rigaud et al., 2009; Weinbrenner et al., 2004; Zák et al., 2005) and low T3 (Matzkin, Geissler, Coniglio, Selles, & Bello, 2006) have been associated with increased HDL, but one study showed no association (Ohwada et al., 2006), rendering results inconclusive. Furthermore, GH is elevated in AN (Schorr & Miller, 2017) and may have a direct lipolytic effect independent from insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), increasing especially LDL concentrations (Misra et al., 2006).Another potential explanation is that steroid hormones such as cortisol and estradiol (for which cholesterol is the precursor) are associated with lipid alterations and, in AN the hypoestrogenic state is differentially associated with increased cholesterol in premenarchal and postmenarchal female patients (Swenne, 2016). Endothelial dysfunction and hyperlipdemia along with menstrual disturbances in association with estrogen status have also been reported (Rickenlund, Eriksson, Schenck-Gustafsson, & Hirschberg, 2005).

Several studies have raised the question whether increased lipid concentrations during the rapid weight loss phase of AN is specifically related to the disorder or merely reflect the hypocaloric starvation state. In a small study (n=16) on the effect of complete food deprivation for in endurance-trained healthy men who engaged in 10 hours of physical activity per day, the participants had decreased concentrations of LDL and TG alongside increased concentrations of total cholesterol, HDL, and FFA as they entered a catabolic process and lost weight over an 81-hour period; however, all of these changes were reversed within 12 days of recovery, showing a normalization of lipid concentrations (Shpilberg et al., 1990). These results contradict our findings, where we found that individuals with AN do not seem to reach lipid concentrations comparable with HC after partial weight restoration, supporting the notion of an underlying dysregulation.

In longitudinal studies of individuals with AN where lipid profiles normalize after weight restoration, the evidence points towards the effects of starvation for the reason behind the increased lipid concentrations (Rigaud et al., 2009), whereas studies in which there are no significant differences before and after weight restoration may suggest a more fundamental lipid dysregulation (Crisp et al., 1968; Haluzík et al., 1999b; Heilbronn et al., 2007; Kavalkova et al., 2012; Misra et al., 2006; Shih et al., 2016; Umeki, 1988; Uzum et al., 2009).

One association observed in our meta-analysis seems paradoxical as higher HDL cholesterol was associated with increasing BMI in acutely-ill individuals with AN. This phenomenon has been previously reported (Mehler, Lezotte, & Eckel, 1998; Weinbrenner et al., 2004) and remains an enigma. Emerging evidence by Duncan et al. (Duncan et al., 2017), however, showed a significant positive genetic correlation between AN and HDL cholesterol, suggesting that increased lipid concentrations in AN cannot solely be explained by the effect of starvation but more probably by a shared genetic underpinning. Future studies will need to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the increased lipids seen in AN.

Implications for future research

By standardizing study designs and measures, it is possible to obtain meaningful, replicable, and interpretable results. Prospective controlled studies examining the lipid profiles before, during, and after weight gain in large samples of well-characterized patients with long-term follow-up are warranted to understand effects of starvation and underlying biology. Additionally, repeated lipidomic profiles in combination with detailed anthropometrics could help in understanding the mechanism behind potential lipid alterations and may elucidate whether increased lipid concentrations in AN are state- or trait-related. It is important to determine how long the effects of starvation prevail to potentially identify subgroups in AN with persistently higher lipid profiles beyond the point of complete recovery.

The differentiation of state and trait is relevant as it can identify symptoms which are state-dependent in individuals with AN and likely to normalize with remission. If increased lipid concentrations are caused by starvation, they will be correctable by refeeding and weight restoration. However, if increased lipid concentrations are caused by an underlying lipid dysregulation predating the emergence of AN, further in-depth examinations would be warranted to to clarify the cause and site of dysregulation. Lipidomics (full characterization of lipid molecular species and of their biological roles) could assist in understanding the mechanism behind a potential lipid dysregulation (Wenk, 2010).

Limitations

The Cohen’s Kappa/inter-reviewer reliability coefficient for the study selection process could not be calculated as Covidence does not retain information on a reference or study’s voting history once it moves from one task to the next in the screening process. To be able to calculate the inter-reviewer reliability coefficient the number of conflicts in the Resolve Conflicts page should be checked following each stage of screening and these data are not available any longer in Covidence.

AN sample included in the systematic review and meta-analysis was very heterogenous in regards to illness duration and severity, diagnostic tools used to assess AN (including studies using varying diagnostic criteria for AN and overlap between DSM-IV and DSM-5), BMI, body fat mass, age, sex, different fasting periods before blood withdrawal, and lipid concentrations measured in both plasma and serum with different analytical methods (Beheshti, Wessels, & Eckfeldt, 1994), all of which add to the risk of bias. Furthermore, only one study investigated AN binge-eating/purging subtype (Case et al., 1999; Sanchez-Muniz et al., 1991; Weinbrenner et al., 2004), subtype analyses were not feasible due to lack of statistical power.

Most of these observations are only correlational and have been investigated in very small sample sizes with limited statistical power. Studies with larger sample sizes and replication of these findings with in-depth investigations are needed to confirm the validity of these results.

Conclusion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we find evidence of 1) elevated lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in individuals with AN compared with HC; and 2) persistence of elevated lipid concentrations in AN after partial weight restoration. The elevated lipid and lipoprotein concentrations alone could be effects of starvation, yet in the longitudinal studies with the persistenly elevated lipid concentrations the evidence points towards a more fundamental lipid dysregulation which could be presents only in a subgroup of individuals with AN.

Our results also show increased HDL cholesterol concentrations were associated with BMI in acutely-ill individuals with AN, which mirrors the positive genetic correlation between HDL cholesterol and AN uncovered by AN GWAS (Duncan et al., 2017). Our phenotypic finding in combination with the genetic component should be followed up in larger longitudinal studies to investigate if the persistently elevated lipid levels are merely effects of starvation (state-related) or actually due to an underlying dysregulation in the lipid metabolism (trait-related) in individuals with AN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by Mental Health Services - Capital Region of Denmark and the Psychiatric Center Ballerup. Dr. Bulik acknowledges funding from the Swedish Research Council (VR Dnr: 538-2013-8864) and the Klarman Family Foundation (the Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative is an initiative of the Klarman Family Foundation). Dr. Yilmaz acknowledges grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) K01MH109782. Dr. Bulik is a grant recipient from and has served on advisory boards for Shire. She receives royalties from Pearson and Walker. All interests unrelated to this work. Dr. Hussain, Dr. Hübel, Dr. Hindborg, Dr. Lindkvist, Dr. Kastrup, Dr. Yilmaz, Dr. Støving, and Dr. Sjögren have nothing to disclose.

References

- Allen KL, Mori TA, Beilin L, Byrne SM, Hickling S, & Oddy WH (2013). Dietary intake in population-based adolescents: support for a relationship between eating disorder symptoms, low fatty acid intake and depressive symptoms. J Hum Nutr Diet, 26(5), 459–469. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III) (3rd ed.). [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III-R) (3rd ed.). [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (4th ed., Text Revision; ed.). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Arden MR, Weiselberg EC, Nussbaum MP, Shenker IR, & Jacobson MS (1990). Effect of weight restoration on the dyslipoproteinemia of anorexia nervosa. J Adolesc Health Care, 11(3), 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barja-Fernandez S, Folgueira C, Seoane LM, Casanueva FF, Dieguez C, Castelao C, … Nogueiras R (2015). Circulating betatrophin levels are increased in anorexia and decreased in morbidly obese women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 100(9), E1188–E1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, & Mazumdar M (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50(4), 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beheshti I, Wessels LM, & Eckfeldt JH (1994). EDTA-plasma vs serum differences in cholesterol, high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride as measured by several methods. Clin Chem, 40(11 Pt 1), 2088–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blickle JF, Reville P, Stephan F, Meyer P, Demangeat C, & Sapin R (1984). The role of insulin, glucagon and growth hormone in the regulation of plasma glucose and free fatty acid levels in anorexia nervosa. Horm Metab Res, 16(7), 336–340. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland B, Beguin C, Zech F, Desager J, & Lambert M (2001). Serum beta-carotene in anorexia nervosa patients: a case-control study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30(3), 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Meenaghan E, Lawson EA, Misra M, Fazeli P, … Miller KK (2010). Determinants of IGF1 and GH across the weight spectrum: from anorexia nervosa to obesity. European journal of endocrinology, 163(2), 185–191. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, & Lohr KN (2007). Anorexia nervosa treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord, 40(4), 310–320. doi: 10.1002/eat.20367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case T, Lemieux S, Kennedy SH, & Lewis GF (1999). Elevated plasma lipids in patients with binge eating disorders are found only in those who are anorexic. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25(2), 187–193. doi:Doi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper RC, Pandey G, Jaspan JB, & Rubenstein AH (1988). Eating attitudes and glucose tolerance in anorexia nervosa patients at 8-year followup compared to control subjects. Psychiatry research, 25(3), 283–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo M, Scheen A, Lefebvre PJ, & Luyckx AS (1985). Insulin-stimulated glucose disposal is not increased in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 60(2), 311–314. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-2-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney E, Goodwin GM, & Fazel S (2014). Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry, 13(2), 153–160. doi: 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copas J (1999). What works?: selectivity models and meta-analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc, 162(1), 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Copas J, & Shi JQ (2000). Meta-analysis, funnel plots and sensitivity analysis. Biostatistics, 1(3), 247–262. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.3.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copas J, & Shi JQ (2001). A sensitivity analysis for publication bias in systematic reviews. Stat Methods Med Res, 10(4), 251–265. doi: 10.1177/096228020101000402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp AH, Blendis LM, & Pawan GL (1968). Aspects of fat metabolism in anorexia nervosa. Metabolism, 17(12), 1109–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curatola G, Camilloni MA, Vignini A, Nanetti L, Boscaro M, & Mazzanti L (2004). Chemical-physical properties of lipoproteins in anorexia nervosa. Eur J Clin Invest, 34(11), 747–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marinis L, Folli G, D’Amico C, Mancini A, Sambo P, Tofani A, … Barbarino A (1988). Differential effects of feeding on the ultradian variation of the growth hormone (GH) response to GH-releasing hormone in normal subjects and patients with obesity and anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 66(3), 598–604. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-3-598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delporte ML, Brichard SM, Hermans MP, Beguin C, & Lambert M (2003). Hyperadiponectinaemia in anorexia nervosa. Clinical Endocrinology, 58(1), 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L, Yilmaz Z, Gaspar H, Walters R, Goldstein J, Anttila V, … Bulik CM (2017). Significant Locus and Metabolic Genetic Correlations Revealed in Genome-Wide Association Study of Anorexia Nervosa. Am J Psychiatry, 174(9), 850–858. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Winokur G, & Munoz R (1972). Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Archives of general psychiatry, 26(1), 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feillet F, Feillet-Coudray C, Bard JM, Parra HJ, Favre E, Kabuth B, … Vidailhet M (2000). Plasma cholesterol and endogenous cholesterol synthesis during refeeding in anorexia nervosa. Clin Chim Acta, 294(1–2), 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franssila-Kallunki A, Rissanen A, Ekstrand A, Eriksson J, Saloranta C, Widén E, … Groop L (1991). Fuel metabolism in anorexia nervosa and simple obesity. Metabolism, 40(7), 689–694. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90085-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenny EM, Bulik-Sullivan EC, Tang Q, Bulik CM, & Carroll IM (2017). Eating Disorders and the Intestinal Microbiota: Mechanisms of Energy Homeostasis and Behavioral Influence. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 19(8), 51. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0797-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluzík M, Kábrt J, Nedvídková J, Svobodová J, Kotrlíková E, & Papezová H (1999a). Relationship of serum leptin levels and selected nutritional parameters in patients with protein-caloric malnutrition. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 15(11–12), 829–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluzík M, Papezová M, Nedvídková J, & Kábrt J (1999b). Serum leptin levels in patients with anorexia nervosa before and after partial refeeding, relationships to serum lipids and biochemical nutritional parameters. Physiological research, 48(3), 197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluzikova D, Dostalova I, Kavalkova P, Roubicek T, Mraz M, Papezova H, & Haluzik M (2009). Serum concentrations of adipocyte fatty acid binding protein in patients with anorexia nervosa. Physiol Res, 58(4), 577–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbronn LK, Milner KL, Kriketos A, Russell J, & Campbell LV (2007). Metabolic dysfunction in anorexia nervosa. Obes Res Clin Pract, 1(2), I–II. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isner JM, Roberts WC, Heymsfield SB, & Yager J (1985). Anorexia nervosa and sudden death. Annals of Internal Medicine, 102(1), 49–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-1-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewska-Kupczewska M, Straczkowski M, Adamska A, Nikołajuk A, Otziomek E, Górska M, & Kowalska I (2010). Insulin sensitivity, metabolic flexibility, and serum adiponectin concentration in women with anorexia nervosa. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 59(4), 473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavalkova P, Dostalova I, Haluzikova D, Trachta P, Hanusova V, Lacinova Z, … Haluzik M (2012). Preadipocyte factor-1 concentrations in patients with anorexia nervosa: the influence of partial realimentation. Physiol Res, 61(2), 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinefelter HF (1965). Hypercholesterolemia in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 25(11), 1520–1521. doi: 10.1210/jcem-25-11-1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizova J, Dolinkova M, Lacinova Z, Sulek S, Dolezalova R, Housova J, … Haluzik M (2008). Adiponectin and resistin gene polymorphisms in patients with anorexia nervosa and obesity and its influence on metabolic phenotype. Physiol Res, 57(4), 539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson EA, Miller KK, Mathur VA, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Herzog DB, & Klibanski A (2007). Hormonal and nutritional effects on cardiovascular risk markers in young women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 92(8), 3089–3094. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejoyeux M, Bouvard MP, Viret J, Daveloose D, Ades J, & Dugas M (1996). Modifications of erythrocyte membrane fluidity from patients with anorexia nervosa before and after refeeding. Psychiatry research, 59(3), 255–258. doi:Doi 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02777-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, … Moher D (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS medicine, 6(7), e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzkin V, Geissler C, Coniglio R, Selles J, & Bello M (2006). Cholesterol concentrations in patients with Anorexia Nervosa and in healthy controls. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res, 11(2), 1283–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzkin V, Slobodianik N, Pallaro A, Bello M, & Geissler C (2007). Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res, 13(1), 1531–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehler PS, Lezotte D, & Eckel R (1998). Lipid levels in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 24(2), 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra M, Miller KK, Tsai P, Stewart V, End A, Freed N, … Klibanski A (2006). Uncoupling of cardiovascular risk markers in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr, 149(6), 763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyai K, Yamamoto T, Azukizawa M, Ishibashi K, & Kumahara Y (1975). Serum thyroid hormones and thyrotropin in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 40(2), 334–338. doi: 10.1210/jcem-40-2-334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordasini R, Klose G, Heuck C, Augustin J, & Greten H (1977). [Secondary hyperlipoproteinemia type IIa in anorexia nervosa]. Verh Dtsch Ges Inn Med, 83, 384–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCEP. (2001). Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Jama, 285(19), 2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestel PJ (1974). Cholesterol metabolism in anorexia nervosa and hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 38(2), 325–328. doi: 10.1210/jcem-38-2-325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen P, Rucker G, Miettunen J, Carpenter J, & Schumacher M (2007). Statistically significant papers in psychiatry were cited more often than others. J Clin Epidemiol, 60(9), 939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nova E, Lopez-Vidriero I, Varela P, Casas J, & Marcos A (2008). Evolution of serum biochemical indicators in anorexia nervosa patients: a 1-year follow-up study. J Hum Nutr Diet, 21(1), 23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohwada R, Hotta M, Oikawa S, & Takano K (2006). Etiology of hypercholesterolemia in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 39(7), 598–601. doi: 10.1002/eat.20298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omodei D, Pucino V, Labruna G, Procaccini C, Galgani M, Perna F, … Sacchetti L (2015). Immune-metabolic profiling of anorexic patients reveals an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory phenotype. Metabolism, 64(3), 396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickenlund A, Eriksson MJ, Schenck-Gustafsson K, & Hirschberg A. L. n. (2005). Amenorrhea in female athletes is associated with endothelial dysfunction and unfavorable lipid profile. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(3), 1354–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud D (1999). Role of fat nutriments, different types of fatty acids and fat contributions on dyslipoportinemias of undernourished patients with anorexia mentosa when submitted to renutrition. Medecine et Chirurgie Digestives, 28(1), 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud D, Hassid J, Meulemans A, Poupard AT, & Boulier A (2000). A paradoxical increase in resting energy expenditure in malnourished patients near death: the king penguin syndrome. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 72(2), 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud D, Tallonneau I, & Verges B (2009). Hypercholesterolaemia in anorexia nervosa: frequency and changes during refeeding. Diabetes Metab, 35(1), 57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel AR, & Kahn CR (2001). Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature, 414(6865), 799–806. doi: 10.1038/414799a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Muniz FJ, Marcos A, & Varela P (1991). Serum lipids and apolipoprotein B values, blood pressure and pulse rate in anorexia nervosa. Eur J Clin Nutr, 45(1), 33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorr M, & Miller KK (2017). The endocrine manifestations of anorexia nervosa: mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 13(3), 174–186. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwensen HF, Kan C, Treasure J, Hoiby N, & Sjogren M (2018). A systematic review of studies on the faecal microbiota in anorexia nervosa: future research may need to include microbiota from the small intestine. Eat Weight Disord, 23(4), 399–418. doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0499-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih PB, Yang J, Morisseau C, German JB, Zeeland AA, Armando AM, … Kaye W (2016). Dysregulation of soluble epoxide hydrolase and lipidomic profiles in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry, 21(4), 537–546. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpilberg O, Burstein R, Epstein Y, Suessholz A, Getter R, & Rubinstein A (1990). Lipid profile in trained subjects undergoing complete food deprivation combined with prolonged intermittent exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol, 60(4), 305–308. doi: 10.1007/bf00379401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan F, Ghandour M, Reville P, de Laharpe F, & Thierry R (1977). [Variation in serum nonesterified fatty acids during glucose tolerance test in undernourished patients with anorexia nervosa and in obese patients]. Sem Hop, 53(11–12), 661–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan F, Schlienger JL, Blickle JF, & de Laharpe F (1982). [Hormonal adaptation to chronic self-starvation in patients with anorexia nervosa (author’s transl)]. Nouv Presse Med, 11(14), 1055–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch CH, Nikendei C, Schild S, Haefeli WE, Weiss J, & Herzog W (2008). Expression and activity of P-glycoprotein (MDR1/ABCB1) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with anorexia nervosa compared with healthy controls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(5), 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenne I (2016). Plasma cholesterol is related to menstrual status in adolescent girls with eating disorders and weight loss. Acta Paediatr, 105(3), 317–323. doi: 10.1111/apa.13258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terra X, Auguet T, Aguera Z, Quesada IM, Orellana-Gavalda JM, Aguilar C, … Richart C (2013). Adipocytokine levels in women with anorexia nervosa. Relationship with weight restoration and disease duration. Int J Eat Disord, 46(8), 855–861. doi: 10.1002/eat.22166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SG, & Sharp SJ (1999). Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med, 18(20), 2693–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhe AM, Szmukler GI, Collier GR, Hansky J, O’Dea K, & Young GP (1992). Potential regulators of feeding behavior in anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr, 55(1), 28–32. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeki S (1988). Biochemical abnormalities of the serum in anorexia nervosa. J Nerv Ment Dis, 176(8), 503–506. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198808000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzum AK, Yucel B, Omer B, Issever H, & Ozbey NC (2009). Leptin concentration indexed to fat mass is increased in untreated anorexia nervosa (AN) patients. Clinical Endocrinology, 71(1), 33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Víctor VM, Rovira-Llopis S, Saiz-Alarcon V, Sanguesa MC, Rojo-Bofill L, Banuls C, … Hernandez-Mijares A (2014). Altered mitochondrial function and oxidative stress in leukocytes of anorexia nervosa patients. PLoS ONE, 9(9), no pagination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Víctor VM, Rovira-Llopis S, Saiz-Alarcón V, Sangüesa MC, Rojo-Bofill L, Bañuls C, … Hernández-Mijares A (2015). Involvement of leucocyte/endothelial cell interactions in anorexia nervosa. European journal of clinical investigation, 45(7), 670–678. doi: 10.1111/eci.12454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignini A, Canibus P, Nanetti L, Montecchiani G, Faloia E, Cester AM, … Mazzanti L (2008). Lipoproteins obtained from anorexia nervosa patients induce higher oxidative stress in U373MG astrocytes through nitric oxide production. NeuroMolecular Medicine, 10(1), 17–23. doi: 10.1007/s12017-007-8012-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinbrenner T, Zuger M, Jacoby GE, Herpertz S, Liedtke R, Sudhop T, … Berthold HK (2004). Lipoprotein metabolism in patients with anorexia nervosa: a case-control study investigating the mechanisms leading to hypercholesterolaemia. Br J Nutr, 91(6), 959–969. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk MR (2010). Lipidomics: new tools and applications. Cell, 143(6), 888–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zák A, Vecka M, Tvrzicka E, Hruby M, Novak F, Papezova H, … Stankova B (2005). Composition of plasma fatty acids and non-cholesterol sterols in anorexia nervosa. Physiol Res, 54(4), 443–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zák A, Vecka M, Tvrzicka E, Novak F, Papezova H, Hruby M, … Stankova B (2003). [Lipid metabolism in anorexia nervosa]. Cas Lek Cesk, 142(5), 280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.