Abstract

Importance

Commercial virtual visits are an increasingly popular model of care for the management of common, acute illnesses. In commercial virtual visits, patients access a website to be connected synchronously—via videoconference, telephone, or webchat—to a physician with whom they have no prior relationship. There has been no assessment of whether the care delivered through those websites is similar, or whether quality varies among the sites.

Objective

To assess the variation in quality of care among virtual visit companies.

Design

We performed an audit study using trained standardized patients.

Setting

The standardized patients presented to commercial virtual visit companies with six common, acute illnesses (ankle pain, streptococcal pharyngitis, viral pharyngitis, acute rhinosinusitis, low back pain, and recurrent urinary tract infection).

Participants

The eight commercial virtual visit websites with the highest web traffic.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were completeness of histories and physical examinations, naming the correct diagnosis (versus an incorrect diagnosis or not naming any diagnosis), and adherence to guidelines of key management decisions.

Results

Standardized patients completed 599 commercial virtual visits from May 2013 to July 2014. Histories and physical examinations were complete in 69.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.7%-71.6%) of virtual visits, diagnoses were correctly named in 76.5% (CI, 72.9%-79.9%), and key management decisions were adherent to guidelines in 54.3% (CI, 50.2%-58.3%). Rates of guideline-adherent care ranged from 34.4% to 66.1% across the eight websites. Variation across websites was significantly greater for viral pharyngitis and acute rhinosinusitis (12.8-82.1%) than for streptococcal pharyngitis and low back pain (74.6-96.5%) or ankle pain and recurrent urinary tract infection (3.4-40.4%). There was no statistically significant variation in guideline adherence by mode of communication (video vs. telephone vs. webchat).

Conclusions

We found significant variation in quality among companies providing virtual visits for management of common acute illnesses. There was more variation in performance for some conditions than for others, but there was no variation by mode of communication.

Commercial virtual visits are a new form of physician-patient interaction in which patients use websites to request synchronous (live) consultation—via web videoconference, telephone, or webchat—with a physician whom they have not previously met. Commercial virtual visit companies have no in-person care option.1 Instead, advertisements for commercial virtual visit companies emphasize easy access to care, especially acute care, over the web.2 This may be appealing, as difficulty accessing timely care for acute problems from local brick-and-mortar providers (primary care practices, retail clinics, and urgent care centers) is common. In 2013, less than half of US adults reported being able to get same- or next-day appointments with their physicians and less than 40% reported being able to get care after hours without going to the emergency department.3

Commercial virtual visit companies have experienced rapid growth. One company reports a user base of over 6 million people.2 Acceptance by payers is also rising: one of the nation’s larger insurers, Anthem, has launched its own national virtual visit initiative.4 Moreover, the percentage of large employers offering virtual visits tripled from 2010 to 20125 and the number of virtual visits is projected to continue to grow rapidly in the near future.6

In response to this trend, some state medical boards have placed limits on how virtual visits can be performed. Some only allow telemedicine in situations in which there is already an ongoing physician-patient relationship. Others require that a virtual visit occur by videoconference (rather than telephone or webchat), despite a lack of evidence regarding the optimal mode of virtual visit communication.7–10 Recently, the Federal Trade Commission has commented not only on the growth of interstate virtual visits, but also on the uncertainty over which government agencies should oversee them.11 In addition, the industry organization for commercial virtual visit companies, the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), is developing voluntary standards for its members to consider.1

The urgency of the need to develop either a regulatory framework or industry promulgated standards will depend, in part, on how much quality of care varies among virtual visit companies. If variation is large, then characteristics of companies or their processes of care likely influence the quality of the care patients receive. This would constitute a rationale to consider standards or regulations to protect patients.

To measure the variation in performance among commercial virtual visit companies, we used audit methodology to evaluate the quality of care provided by the companies with the highest volume of web traffic. We selected six conditions that the companies advertised that they treat, for which there are evidence-based guidelines, and that have been used in previous studies to measure quality.12–19 We trained standardized patients to present as mystery shoppers with these conditions and gathered information on processes of care and decision-making. In addition, since some states require virtual visits to occur by videoconference,7–10 we compared quality of care by mode of communication (videoconference vs. telephone vs. webchat).

Methods:

Identification of commercial virtual visit companies

We decided a priori to study the eight most frequently visited (as determined by Alexa Rankings, www.alexa.com) companies meeting the eligibility criteria (see supplementary appendix). These were Ameridoc, Amwell, ConsultaDr, DoctoronDemand, MDAligne, MDLive, MeMD, and NowClinic.

Mode of Communication

All visits were initiated by a standardized patient (description of standardized patients is below) visiting a company website. Most companies offered encounters only through videoconferencing or telephone. When given a choice as to visit modality, standardized patients were instructed to a use a coin flip to choose between telephone and videoconference. On occasion, the virtual visit physician would override the standardized patient’s choice and proceed with a different mode for technical or convenience reasons (video, telephone, or webchat).

Selection of Cases

Six clinical case vignettes were designed in consultation with a panel of four board-certified physicians representing pediatrics (N.S.B.), emergency medicine (R.D.), internal medicine (G.A.L.), and pulmonary medicine (R.A.D.). Among the set of conditions the websites advertised that they treated, the panel chose situations in which there was a widely recognized and used guideline applicable to the situation. We then wrote the scenarios to have as many vignettes in which an action (prescribing or ordering tests) was recommended as vignettes in which guidelines recommended no action. We were limited to six total vignettes and the desire to have adequate power to assess care at the top 8 websites (see supplementary appendix). The cases involved low back pain, recurrent female urinary tract infection (UTI), acute rhinosinusitis, viral pharyngitis, streptococcal pharyngitis, and ankle pain. Vignettes were written to represent typical cases that might be seen in an urgent-care setting. In some vignettes, testing, imaging, or treatment is recommended in guidelines. In others, testing, imaging, or treatment is specifically noted as not necessary in guidelines (Table 1).12–19 For each vignette, a key management decision (getting testing or not or prescribing or not) was identified a priori by the physician team.

Table 1.

Guidelines, Key History and Physical Measures, Management Decision, and Number of Visits by Condition

| Condition | Guidelines | Completeness of History and Physical | Recommended Management | Number of Visits N=599 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankle Pain | Ottawa Ankle Rules | •Ability to Walk •Tenderness at Lateral Malleolus |

Order Ankle X-ray | 102 (17%) |

| Streptococcal Pharyngitis | Modified Centor Criteria | •Fever •Tonsilar Exudates •Absence of Cough •Tender Cervical Adenopathy |

Order Strep Test or Prescribe antibiotics | 97 (16%) |

| Viral Pharyngitis | Modified Centor Criteria | •Fever •Tonsillar Exudates •Absence of Cough •Tender Cervical Adenopathy |

Order Strep Test or Do Not Prescribe Antibiotics | 82 (14%) |

| Rhinosinusitis | American Academy of Family Physicians Diagnostic Guidelines | •Fever •Facial Pain •Tooth Pain •Nasal Discharge •Symptom Time Course |

Do Not Prescribe Antibiotics | 105 (18%) |

| Low Back Pain | American College of Physicians Diagnostic Guidelines | •Symptom Duration •History of Pain/Trauma •Location/Radiation of Pain •Bowel or Bladder Changes •Myelopathy/Radiculopathy |

Do Not Order Imaging or Other Diagnostic Tests | 92 (15%) |

| Recurrent Female Urinary Tract Infection | Infectious Diseases Society of America | •Fever •History of UTIs •Urinary Symptoms •Duration of Symptoms •Prior Testing/Treatment •Suprapubic/Flank/Back Pain |

Order Urine Culture | 121 (20%) |

Standardized Patient Recruitment and Training

Individuals who served as standardized patients were recruited from two groups: 1) actors with prior training as standardized patients at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Kanbar Center for Clinical Skills and Telemedicine Education Standardized Patient Program, or 2) students currently enrolled in an accredited US medical school. Each vignette was first taught to experienced standardized patient trainers from the Kanbar Center. These trainers then instructed the standardized patients (while being observed by one or more of the study physicians) in the technical and clinical aspects of the study, including typical manifestations of the condition, standardized interaction techniques, and scoring criteria for study variables. During training, standardized patients performed role-plays reflecting characteristic encounters, and checklists were scored for data collection reliability. Particular focus was put on ensuring the standardized patients knew not to suggest any specific diagnoses, tests, or treatments. All standardized patients exceeded the pre-specified 90% accuracy threshold by the end of the training and also were audited by supervising physicians throughout the study.

Study Materials

Standardized patients carried out virtual visits from May 2013 to July 2014. Details of each encounter were recorded immediately following the virtual visit. Using a data collection form, standardized patients recorded physician and company names, whether specific elements of the history and physical were performed, the diagnosis (if a diagnosis was named), testing ordered, and prescriptions provided. The websites were paid their usual charges for the study virtual visits. If the websites did not respond to encounter requests in a timely fashion (1-2 days), the SPs were unable to complete the visit. Therefore, there was variation in number of cases completed by website (see supplementary table).

Study Variables

The three primary outcomes for each virtual visit in our study were: performing a complete history and physical examination, naming the correct diagnosis, and adherence to the relevant guideline in the key management decision. The completeness of the history and physical was a score derived using items referenced in guidelines as important for diagnosis and/or treatment decision. Since we anticipated that not all physical exam maneuvers could be performed remotely, we gave credit on the physical exam if the physician sought the relevant information by asking the patient to perform the maneuver. For example, in the case of streptococcal pharyngitis, we gave credit for assessing for tonsillar exudate if the physician asked the patient to look in the back of his or her own throat.

Naming the correct diagnosis was coded as a binary variable, based on whether the physician told the standardized patient the correct diagnosis. For each diagnosis, the physician would be given credit for naming the correct diagnosis if he or she mentioned any one of a list of terms (see supplementary appendix).. For example, if a physician gave the patient a more general diagnosis (UTI for recurrent UTI), they were given credit as a correct diagnosis. If, however, the physician diagnosed what was actually viral pharyngitis as a bacterial infection, this was considered incorrect. Standardized patients were instructed not to ask physicians for a diagnosis. If a physician gave no diagnosis at all, this was considered a failure to name the correct diagnosis.

Adherence to guidelines was coded as a binary variable for each visit, based on whether the physician’s key management decision agreed with the relevant guideline (Table 1).

We evaluated the variation in performance among individual companies at different points along the performance spectrum by grouping conditions based upon the average percent adherence to key management decision guidelines across all companies. We assessed the between-company variation within these groups. We used three groups (pairs) of conditions (the two conditions with the highest overall performance, the two conditions with the lowest overall performance, and the two in the middle). We also assessed whether there was an association between performance on the three primary outcomes and communication modality (videoconference vs. telephone vs. webchat).

The secondary outcome was the frequency of referrals to a local brick-and-mortar provider for an in-person visit or testing. Standardized patients recorded the rationale the physician offered for any such referral.

Data Analysis

We used mixed-effects models to account for clustering by condition, website, and physician. The condition and website effects were treated as fixed effects, while the physician-level effects were treated as random. For binary outcomes, we used a mixed-effects logistic regression model. For continuous outcomes, we used a mixed-effects linear regression model. The rates for all binary outcomes are presented as the predicted marginal probabilities and the rates for continuous outcomes as the predicted marginal means from these models using the margins command.

We used Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) to perform all statistical analyses. This study was approved by the UCSF institutional review board.

Results:

Standardized patients completed 599 virtual visits (Table 1) with 157 internal medicine, emergency medicine, or family practice physicians. The median number of visits per site was 77 (interquartile range [IQR] 63.5-88.5). These included 372 (62.1%) videoconference encounters, 170 (28.4%) telephone encounters, and 57 (9.5%) webchat encounters. The median number of visits per doctor was 1 (IQR 1-4).

Completeness of Histories and Physical Examinations and Naming of the Correct Diagnosis

Virtual visit physicians asked all recommended history questions and performed all recommended physical examination maneuvers in 69.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.7%-71.6%) of visits. Physicians named the correct diagnosis in 76.5% (CI, 72.9%-79.9%) of visits. Physicians gave the wrong diagnosis in 14.8% (CI, 12.0%-17.9%) of visits or provided no diagnosis in 8.7% (CI, 6.6%-11.3%) of visits.

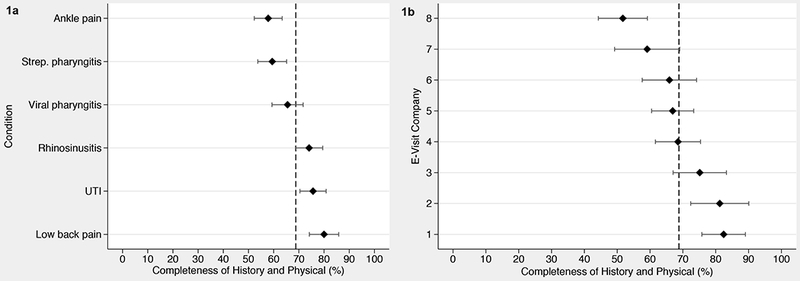

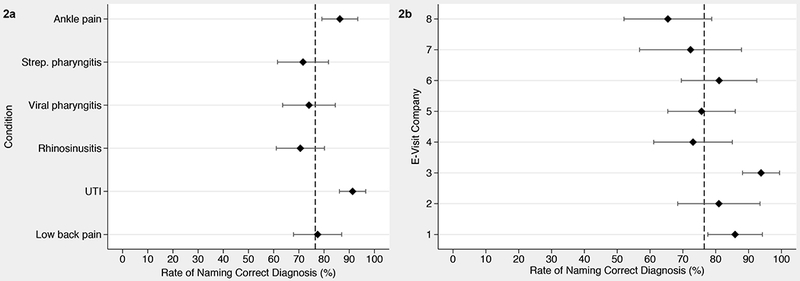

Completeness of histories and physical examinations and naming the correct diagnosis varied by condition and virtual visit company (Figures 1 and 2, p<0.001 for the statistical significance of the variation by condition and by company in both figures). For low back pain, 80.0% (CI, 74.2%-85.8%) of histories and physical examinations taken were complete, compared with only 57.8% (CI, 52.3%-63.4%) for ankle pain. The rate of physicians naming the correct diagnosis also varied by condition, from 91.3% (CI, 86.1%-96.5%) for recurrent UTI, to 70.9% (CI, 61.0%-80.2%) for rhinosinusitis.

Figure 1a and 1b. Completeness of History and Physical Exam by Condition and by Virtual Visit Company.

Abbreviations: Strep., streptococcal; UTI, recurrent female urinary tract infection. Each point represents the adjusted mean rate of completeness by condition (Figure 1a) across all virtual visit companies and adjusted mean rate of completeness by virtual visit company (Figure 1b) across all conditions. The error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The dotted line is the aggregate mean across conditions (Figure 1a) or virtual visit companies (Figure 1b). There was statistically significant variation in completeness by condition (P<.001) and by virtual visit company (P<.001).

Figure 2a and 2b. Rate of Physician Naming the Correct Diagnosis by Condition and by Virtual Visit Company.

Abbreviations: Strep., streptococcal; UTI, recurrent female urinary tract infection. Rates of naming the correct diagnosis for each visit based upon whether the physician stated the correct diagnosis for each encounter. Each point represents the adjusted mean rate of naming the correct diagnosis by condition (Figure 2a) across all virtual visit companies and adjusted mean rate of naming the correct diagnosis by virtual visit company (Figure 2b) across all conditions. The error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The dotted line is the aggregate mean across conditions (Figure 2a) or virtual visit companies (Figure 2b). There was statistically significant variation in naming the correct diagnosis by condition (P<.001) and by virtual visit company (P<.001).

When evaluated by company, the percent of virtual visits with complete histories and physicals ranged from 51.7% to 82.4% and the percent of virtual visits with correct diagnoses named ranged from 65.4% to 93.8%.

Adherence to Guidelines for Management Decisions

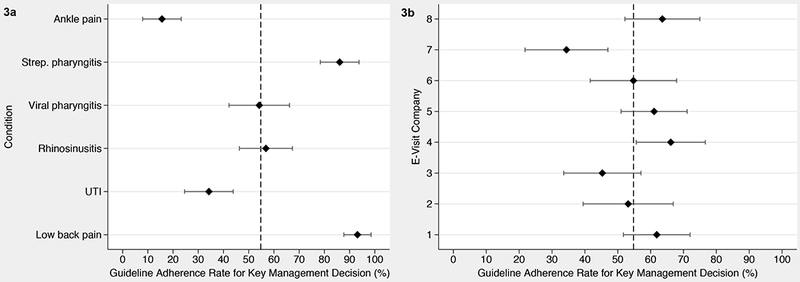

Across all conditions at all companies, key management decisions were guideline-adherent in 54.3% of visits (CI, 50.2%-58.3%). There was substantial variation among conditions and among companies (Figure 3, p<0.001 for the statistical significance of the variation among conditions and among companies). For example, physicians ordered urine cultures for recurrent UTI only 34.2% of the time (CI, 24.5%–43.8%) and guideline-recommended x-rays for ankle pain only 15.5% of the time (CI, 7.9%–23.2%), whereas they (appropriately) did not order an x-ray for low back pain 93.1% of the time (CI, 87.7%–98.5%). Across virtual visit companies, adherence of key management decisions to guidelines ranged from 34.4% to 66.1%.

Figure 3a and 3b. Adherence to Guidelines for Key Management Decisions by Condition and by Virtual Visit Company.

Abbreviations: Strep., streptococcal; UTI, recurrent female urinary tract infection. Each point represents the adjusted mean rate of adherence by condition (Figure 3a) across all virtual visit companies and adjusted mean rate of adherence by virtual visit company (Figure 3b) across all conditions. The error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The dotted line is the aggregate mean across conditions (Figure 3a) or virtual visit companies (Figure 3b). There was statistically significant variation in guideline adherence by condition (P<.001) and by virtual visit company (P=.009).

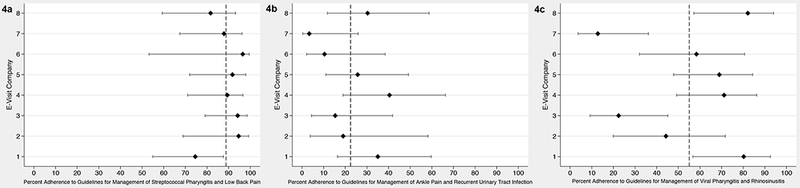

The pattern of variation in virtual visit companies’ performance differs by condition (Figures 4a, 4b, and 4c). For the two conditions (low back pain and streptococcal pharyngitis) with the highest overall adherence to guidelines (ranging among companies from 74.6% to 96.5%), there was no statistically significant variation in virtual visit companies’ performance (p=0.290, Figure 4a). Similarly, for the two conditions (ankle pain and recurrent UTI) with the lowest overall performance (3.4–40.4%), there was no statistically significant variation in virtual visit companies’ performance (p=0.330, Figure 4b). For the two remaining conditions (viral pharyngitis and acute rhinosinusitis), however, there was statistically significant variation in performance (p<0.001, Figure 4c), with a range among websites from 12.8% to 82.1%.

Figure 4. Variation by Pairs of Conditions Among Virtual Visit Companies in Adherence to Guidelines for Key Management Decisions.

Abbreviations: Strep., streptococcal; UTI, recurrent female urinary tract infection. Each point represents the adjusted mean rate of adherence to guidelines in key management decisions (for streptococcal pharyngitis and low back pain in Figure 4a, for ankle pain and urinary tract infection in Figure 4b, and for viral pharyngitis and acute rhinosinusitis in Figure 4c) for each virtual visit company and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The dotted line is the aggregate mean across virtual visit companies. Lower rates indicate lower adherence to guidelines in management decisions. The dotted line is the aggregate mean across virtual visit companies. There was no statistically significant variation between virtual visit companies in adherence to guidelines for streptococcal pharyngitis and low back pain (P=.290) or for ankle pain and urinary tract infection (P=.328), although the variation in adherence to guidelines was significant for viral pharyngitis and acute rhinosinusitis (P<.001).

Referrals

In 83 patient encounters (13.9%), physicians made a referral to local brick-and-mortar providers. The most common stated reasons for referral were that the physician considered the case out of the scope of care that could be provided online, or that the case required additional follow-up that could not be provided online.

Mode of communication

Both videoconference (85.8%; CI, 77.6%-93.9%) and telephone encounters (77.7%; CI, 70.8%-84.7%) were superior to webchat (66.1%; CI, 52.2%-80.1%) in naming the correct diagnosis (p=0.012). There was no significant difference between videoconference vs. telephone in rate of naming the correct diagnosis. There were no statistically significant differences between modes of communication in completeness of history and physical or adherence to guidelines.

Comment

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate variation in the quality of medical encounters provided by commercial virtual visit companies. We found substantial and statistically significant variation in guideline adherence among virtual visit companies and that the variation differs by condition. We found no significant difference in guideline adherence by mode of communication (video vs. phone vs. webchat).

In some ways, our finding that care varies online is consistent with prior literature of traditional care settings,20–23 where there is extensive evidence of failure to follow guidelines and of variation in quality of care.

Particularly, the antibiotic prescribing rate in commercial virtual visits we observe is similar to the rate seen in-person nationally in traditional settings. For instance, a prior study found that antibiotics were prescribed to approximately 60% of patients seen at primary care practices and emergency departments with sore throat nationally,24 while others have documented 80% prescribing to patients with upper respiratory infections.25,26

Previous literature has also compared antibiotic prescribing patterns during virtual visits (with providers who also offered in-person care) to visits in traditional settings. Courneya et al.27 found lower prescription rates for acute bronchitis during an online interactive algorithmic visit than for traditional visits, whereas Mehrotra et al.28 found that antibiotics were prescribed for presumed acute sinusitis at higher rates during virtual visits than traditional visits. Thus, antibiotic prescribing for viral illnesses appears to be an area needing attention in all care settings.

Conversely, our study demonstrates that the rates of testing in situations in which testing is not recommended may be lower in virtual care than traditional settings, but rates of obtaining tests that are recommended are also lower. . For low back pain, virtual visit providers adhered to guidelines and did not order x-rays 93% of the time, while Rosenberg et al.26 found that brick-and-mortar providers ordered additional imaging approximately half the time. In the case of ankle injury, prior studies suggest that the large majority of patients who present to brick-and-mortar practices receive imaging, whereas only 15.5% of patients were recommended imaging in our study.29 Avoiding additional testing is appropriate in some cases, but the uniformly low rates of testing in the virtual visits may actually reflect the logistical challenges of ordering or following up on tests to be performed near where the patient lived or concern about the out-of-pocket costs for additional testing. These hypotheses need to be tested in future studies. Since appropriate use of testing is critical to the delivery of medical care, identifying and reducing barriers to testing will be important.

The evidence we found does not appear to support the limitation of virtual visits to videoconference. There is ongoing debate about what modes of communication constitute a safe and appropriate telemedicine encounter.7–9 In Texas, for example, the state’s medical board recently ruled to restrict telemedicine encounters to videoconference due to safety concerns10 and the Federation of State Medical Boards has excluded audio-only and webchat visits from the definition of telemedicine. However, with regards to guideline adherence, we found no statistically significant difference by mode of communication.

The fact that some companies can perform considerably better than others suggests this variation could be addressed if performance leaders were willing to share their best practices with other virtual visit companies. Further research is required to evaluate whether better performing virtual visit companies have adopted some company-wide policy or protocol(s) that increase guideline adherence.

There are limitations of this study. First, we do not know if virtual visits are superior or inferior to in-person visits. Second, this is an evolving market and some companies had to be excluded early on from the study because they ceased operations. Third, we do not know the exact market share of each company included in our study. However, the companies that remained were the most trafficked and thus our study presumably captures the major companies in this market currently. Finally, we looked at only eight virtual visit companies and six conditions and sample size is a potential limitation. However, we have adjusted for company and condition in our statistical analysis and thus clustering and co-linearity are not responsible for observed differences by company, condition, or modality. Further, we studied the companies that receive the most traffic, and studied their care for common conditions that they advertise they treat.

In summary, our study provides the first evaluation of the variation in quality of care currently being provided during commercial virtual visits. There is significant variation across companies and by condition. The patterns of variation we observed imply an opportunity to improve and point toward approaches to determining how to do so.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Changes in Health Care Financing and Organization Program, Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies Innovation Fund, the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), National Institutes of Health, through grant No R25MD006832, and the Grove Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Notification: None

References

- 1.DeJong C, Santa J,Dudley R. Websites that offer care over the internet: Is there an access quality tradeoff? JAMA. 2014;311(13):1287–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uscher-Pines L, Mehrotra A. Analysis of teladoc use seems to indicate expanded access to care for patients without prior connection to a provider. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(2):258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the united states compared to ten other countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2205–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolan B Wellpoint now offering mobile video visits with physicians in 44 states. Mobilhealthnews. June 4, 2014. http://mobihealthnews.com/33816/wellpoint-now-offering-mobile-video-visits-with-physicians-in-44-states/. Accessed December 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathews AJ. Doctors move to webcams. The Wall Street Journal. December 20, 2012. 2012;B1 http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324731304578189461164849962.html. Accessed December 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deloitte CIO Journal Editor. eVisits: The 21st Century House Call. The Wall Street Journal, March 6, 2014. http://deloitte.wsj.com/cio/2014/03/06/evisits-the-21st-century-house-call/. Accessed January 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Telemedicine Association. Proposed changes to the model policy for the appropriate use of telemedicine technologies in the practice of medicine, 2014. http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/click-here.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 20, 2014.

- 8.Blackwell H Kwolek K. Big redial – Texas telephone medicine terminated? Lexology. January 27, 2015. http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=9593e00a-f0be-4929-8f7a-464cbebee1a5. Accessed February 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Connected Health Policy. State Telehealth Policies and Reimbursement Schedules. September 2014. http://cchpca.org/sites/default/files/uploader/50%20STATE%20MEDICAID%20REPORT%20SEPT%202014.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2015.

- 10.Goodnough A The New York Times. Texas Medical Panel Votes to Limit Telemedicine Practices in State; April 10, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/11/us/texas-medical-panel-votes-to-limit-telemedicine-practices-in-state.html. Accessed April 20, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohlhausen M Beyond Law Enforcement: The FTC’s Role in Promoting Health Care Competition and Innovation. Health Affairs Blog. January 26, 2015. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/01/26/beyond-law-enforcement-the-ftcs-role-in-promoting-health-care-competition-and-innovation/. Accessed February 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snow V, Mottur-Pilson C, Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):506–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, Vanjaka A, Low DE. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1587–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america and the european society for microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the american college of physicians and the american pain society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, Gonzales R, Hoffman JR, Sande MA. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults: Background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, Riet Gt. Accuracy of ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: Systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326(7386):417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, Brody CE, Link K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1(3):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dason S, Dason JT, Kapoor A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5(5):316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the united states. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, and Donaldson MS, eds. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dekker AR, Verheij TJ, van der Velden AW. Inappropriate antibiotic prescription for respiratory tract indications: Most prominent in adult patients. Fam Pract. 2015;32(4):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient satisfaction and quality of surgical care in US hospitals. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):2–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett ML, Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing to adults with sore throat in the united states, 1997-2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):138–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Quality compass. NCQA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early Trends Among Seven Recommendations From the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Courneya PT, Palattao KJ, Gallagher JM. HealthPartners’ online clinic for simple conditions delivers savings of $88 per episode and high patient approval. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehrotra A, Paone S, Martich GD, Albert SM, Shevchik GJ. A comparison of care at e-visits and physician office visits for sinusitis and urinary tract infection. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(1):72–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2003;326(7386):417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.