Abstract

Background

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a heterogeneous disease characterized by mucosal inflammation in the nose and paranasal sinuses. Inflammation in CRS is also heterogeneous and is mainly characterized by type 2 (T2) inflammation but subsets of patients show type 1 (T1) and type 3 (T3) inflammation. Whether inflammatory endotypes are associated with clinical phenotypes has yet to be explored in detail.

Objective

To identify associations between inflammatory endotypes and clinical presentations in CRS.

Methods

We compared 121 non-polypoid CRS (CRSsNP) patients and 134 polypoid CRS (CRSwNP) patients and identified inflammatory endotypes using markers including IFN-γ (T1), eosinophil cationic protein (T2), Charcot-Leyden crystal galectin (T2) and IL-17A (T3). We collected clinical parameters from medical and surgical records and examined whether there were any associations between endotype and clinical features.

Results

The presence of nasal polyps (NPs), asthma comorbidity, smell loss and allergic mucin were significantly associated with the presence of T2 endotype in all CRS patients. The T1 endotype was significantly more common in females, and the presence of pus was significantly associated with T3 endotype in all CRS. We further analyzed these associations in CRSsNP and CRSwNP separately and found smell loss was still associated with T2 endotype and pus with the T3 endotype in both CRSsNP and CRSwNP. Importantly, CRS patients with T2 and T3 mixed endotype tended to have clinical presentations shared by both T2 and T3 endotypes.

Conclusions

Clinical presentations are directly associated with inflammatory endotypes in CRS. Identification of inflammatory endotypes may allow for more precise and personalized medical treatments in CRS.

Keywords: Chronic rhinosinusitis, Clinical presentation, Endotype-phenotype association, Inflammatory endotype

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a heterogeneous disease that affects approximately 12.5% of Americans, is responsible for over 400,000 surgeries annually, produces significant morbidity and costs our health system an estimated $22–32 billion annually.1–4 Most investigators accept a paradigm in which CRS is divided into the two main phenotypes: CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP). In Western countries, CRSwNP is well known to be characterized by type 2 (T2) inflammation with pronounced eosinophilia and the presence of high levels of T2 cytokines, such as IL-5 and IL-13.5–9 In contrast, CRSsNP is less well characterized despite 80% of all CRS patients having this phenotype.1, 2, 10 Recently, we comprehensively characterized inflammatory patterns by using IFN-γ as a type 1 (T1) marker, Charcot-Leyden crystal galectin (CLC) mRNA or eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) as T2 markers and IL-17A for a type 3 (T3) marker in CRS patients who had undergone surgery at our institution. We found that inflammation in CRSsNP is highly heterogeneous, much more so than what was observed in CRSwNP.7 Similar to other studies in the US and Europe, we reported that the most frequent inflammatory endotype in CRSsNP was T2, as opposed to T1 or T3.7–9, 11, 12 Additionally, on further analysis, we identified subsets of patients who had more than one type of inflammatory endotype, as characterized by concurrent elevations in T1, T2 and/or T3 markers.7 While these studies shed light onto the different molecular mechanisms underlying CRS, it remains unknown if (or how) this inflammation impacts the clinical presentation. Specifically, CRS patients experience diverse sinonasal and systemic symptoms,13–15 but the relationship between a particular clinical phenotype and an inflammatory endotype is not well defined.

In the past decade, several groups have examined the association between endotypes and phenotypes in asthma. The Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) and the Unbiased BIOmarkers in PREDiction of respiratory disease outcomes (U-BIOPRED) studies both identified asthma phenotypes and related them to inflammatory endotypes, including gene expression profiles, eosinophilia and neutrophilia.16–21 In contrast to asthma, however, investigations into the association between endotype and phenotype of CRS remain scarce, except for the known association of T2 inflammation with nasal polyps (NPs) and asthma.8, 22 In this study, we hypothesized that certain CRS inflammatory endotypes are associated with specific clinical presentations. We therefore set out to define the endotype-phenotype associations in CRS by examining clinical characteristics of CRS patients evaluated in our previously published endotyping study.7

METHODS

Patients and tissue collection

We used mRNA and protein data from our published study, which included 255 CRS patients.7 All CRS patients were recruited from the Otolaryngology clinic and the Northwestern Sinus Center of Northwestern Medicine. All CRS patients met the criteria for CRS as defined by the International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Rhinosinusitis.2 Patients with an established immunodeficiency, pregnancy, coagulation disorder or diagnosis of aspirin hypersensitivity, classic allergic fungal sinusitis, eosinophilic granulomatous polyangiitis (eGPA or Churg-Strauss syndrome) or cystic fibrosis were excluded from the study. Characteristics of subjects in this study are shown in Table 1. All subjects signed informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine (IRB Project Number: STU00016917).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with CRSsNP and CRSwNP

| CRSsNP % (n=121) | CRSwNP % (n=134) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), median (range) | 38 (19–74) | 45 (20–76) | 0.071 |

| Sex (female) | 57.0 | 35.1 | < 0.001 |

| Atopy* | 43.7 | 64.3 | 0.002 |

| Asthma | 29.8 | 44.0 | 0.019 |

| Current smoker | 4.1 | 5.2 | 0.681 |

| Nasal congestion/obstruction/blockage | 89.3 | 94.0 | 0.172 |

| Rhinorrhea/Post nasal drip/Nasal drainage | 84.3 | 69.2 | 0.005 |

| Purulent nasal drainage | 19.8 | 19.5 | 0.954 |

| Sinus pressure/pain | 73.6 | 54.9 | 0.002 |

| Headache/Migraine | 25.6 | 14.3 | 0.023 |

| Fatigue/Fever/Feel poor | 14.9 | 5.3 | 0.010 |

| Smell loss/Reduced taste | 33.9 | 72.2 | < 0.001 |

| Ear fullness/pain/popping | 17.4 | 13.5 | 0.399 |

| Eye watering/itching | 8.3 | 6.8 | 0.651 |

| Cough | 24.8 | 8.3 | < 0.001 |

| History of FESS (> 2) | 12.4 | 30.6 | 0.001 |

| Intra-Operative Pus# | 15.0 | 10.3 | 0.271 |

| Allergic mucin# | 2.7 | 11.9 | 0.007 |

The p value was determined by the Chi-square test.

CRSsNP (n=119) and CRSwNP (n=112).

CRSsNP (n=113) and CRSwNP (n=126).

CRS Endotyping

We determined mRNA and protein for endotypic markers in ethmoid and NP tissues.7 Only a minor subset of patients had matched data for mRNA and protein. Endotyping was blinded to the clinical parameters. For T1 inflammation, we evaluated gene expression and protein levels of IFN-γ. For T2 inflammation, we evaluated CLC mRNA and ECP levels. For T3 inflammation, we measured IL-17A gene expression and protein levels.7 If a donor had both mRNA and protein data available, the mRNA results were used. If a CRSwNP donor had both ethmoid and NP tissue available, the NP data was used. We used a cutoff of greater than 90th percentile of the expression in control ethmoid tissue to define endotypes. Control patients were undergoing surgery for non-CRS indicated procedures such as cranial tumor resection or septoplasty, and their clinical characteristics are shown in this article’s online repository (Table E1).

For the analysis of endotype-phenotype associations, we primarily compared clinical presentations with the presence and/or absence of specific endotypes. We secondarily compared untypeable patients, i.e. those who did not have any elevation of T1, T2 or T3 inflammation, with patients who had a single endotype (e.g. they had only T2 inflammatory profile) as well as with patients who had a mixed endotype (e.g. they had both T1 and T2 inflammatory profiles).

CRS Phenotyping

The medical records for each study subject were manually reviewed to obtain information about various clinical and demographic parameters. Reviewers of the medical record were blinded to the endotyping results. Information was gathered from outpatient clinic visits within the 6 months prior to the subject’s sinus surgery and the operative notes from the day of the procedure. Patients were determined to have asthma and/or atopy if there was a physician diagnosis listed in the clinical record. The clinical symptoms reviewed included nasal congestion, obstruction, blockage, rhinorrhea, post nasal drip, nasal drainage, purulent nasal drainage, sinus pressure/pain, headache, fatigue, fever, smell loss, reduced taste, ear fullness, ear pain, ear popping, eye watering, eye itching, and cough. For the data analysis, similar symptoms (e.g. nasal congestion, obstruction, blockage) were grouped together in one category. A history of physician diagnosed migraine was included with the symptom of headache. In the surgical report, two additional parameters, namely the presence of intra-operative pus and allergic mucin, were identified. In some instances, information regarding atopy status or the presence of pus or allergic mucin during surgery was not identified in the medical records. If this information was not available, those patients were excluded from these specific analyses.

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using Graphpad Prism version 6.07 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R 3.3.3. The Chi-square test was used for comparisons among different patient groups. The Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction was used to compare means among different groups regarding age. Separate logistic regression analyses were performed for the dependent variables intraoperative pus, each specific symptom, history of > 2 FESS, and allergic mucin. The main predictor was endotype with additional covariates including age, sex, asthma, atopy, and NP. The corresponding odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value were calculated by logistic regression. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Inflammatory endotypes in CRS

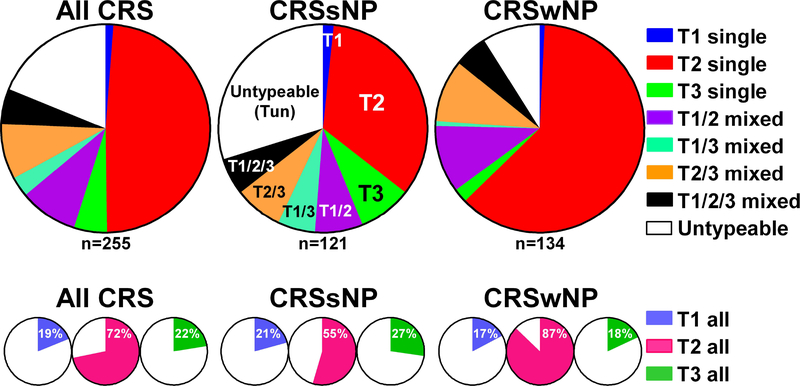

We analyzed our published data,7 which included 121 CRSsNP patients and 134 CRSwNP patients, and defined inflammatory endotypes by using the 90th percentile of expression of markers in control ethmoid tissue as the threshold. Among CRSsNP patients, the overall frequency of having any T1, T2 or T3 inflammation was 21%, 55% and 27%, respectively, of which 1.7%, 34% or 8.3% had evidence of only T1, T2, or T3 inflammation (single endotypes) (Fig. 1). Among CRSwNP patients, the overall frequency of any T1, T2 or T3 inflammation was 17%, 87% and 18%, respectively, of which 0.7%, 62% or 2.2% had only T1, T2, or T3 single inflammation (Fig. 1). Twenty six percent of CRSsNP and 26% of CRSwNP patients had a combination of T1, T2, and/or T3 inflammation and were thus referred to as having mixed endotypes. In contrast, 30% of CRSsNP patients and 9% of CRSwNP patients had no detectable elevations of T1, T2, or T3 inflammation and thus were referred to as having an untypeable (Tun) endotype (Fig. 1). The frequency of T2 inflammation was significantly higher in CRSwNP than CRSsNP (p<0.001) and the frequency of T3 inflammation tended to be higher in CRSsNP than CRSwNP (p=0.073).

Figure 1.

Patterns of inflammatory endotypes in CRS.

Differences in clinical presentation between CRSsNP and CRSwNP

We reviewed 16 clinical parameters, including 14 parameters in the clinical chart and 2 parameters in the surgical report, and examined whether there were any differences between CRSsNP and CRSwNP. We found that CRSsNP had a higher prevalence of females compared to CRSwNP (Table 1). The frequency of asthma and atopy were significantly higher in CRSwNP than CRSsNP (Table 1) confirming our previous findings.10, 23 In regards to symptoms, we found that rhinorrhea, sinus pressure/pain, headache/migraine, fatigue/fever and cough were more often reported by patients with CRSsNP compared to CRSwNP patients (Table 1). In contrast, smell loss was more frequently reported by patients with CRSwNP. Additionally, history of recurrent functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) and the presence of allergic mucin were more frequently found in CRSwNP (Table 1).

Inflammatory endotypes associate with clinical presentations in all CRS

We examined whether specific clinical characteristics were associated with a particular inflammatory endotype (Table 2). Among all CRS patients, those with the T2 endotype were significantly more likely to have NPs, asthma, smell loss and allergic mucin and were less likely to report rhinorrhea, cough and pus (Table 2). We also found that the T1 endotype was more common in females, and the presence of pus was significantly associated with the T3 endotype (Table 2). Other features including atopy, nasal congestion, purulent nasal drainage, sinus pressure, headache, fatigue, ear fullness, ocular symptoms, and history of FESS were not different among the 3 inflammatory endotypes (Table E2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of clinical presentations and inflammatory endotypes in all CRS, CRSsNP and CRSwNP

| T1 endotype | T2 endotype | T3 endotype | |||||||

| All CRS | Absence % (n=207) | Presence % (n=48) | p value | Absence % (n=72) | Presence % (n=187) | p value | Absence % (n=198) | Presence % (n=57) | p value |

| NP | 53.6 | 47.9 | 0.476 | 23.6 | 63.9 | < 0.001 | 55.6 | 42.1 | 0.073 |

| Sex (female) | 42.0 | 64.6 | 0.005 | 51.4 | 44.3 | 0.304 | 44.9 | 50.9 | 0.429 |

| Asthma | 36.2 | 41.7 | 0.483 | 26.4 | 41.5 | 0.024 | 38.4 | 33.3 | 0.487 |

| Rhinorrhea/Post nasal drip/Nasal drainage | 75.7 | 79.2 | 0.614 | 84.7 | 73.1 | 0.049 | 75.6 | 78.9 | 0.604 |

| Headache/Migraine | 21.4 | 12.5 | 0.165 | 20.8 | 19.2 | 0.772 | 20.8 | 15.8 | 0.401 |

| Smell loss/Reduced taste | 55.8 | 45.8 | 0.211 | 30.6 | 63.2 | < 0.001 | 55.3 | 49.1 | 0.408 |

| Cough | 17.0 | 12.5 | 0.446 | 25.0 | 12.6 | 0.016 | 17.3 | 12.3 | 0.368 |

| Intra-Operative Pus# | 10.5 | 20.8 | 0.053 | 19.4 | 9.9 | 0.046 | 7.5 | 30.2 | < 0.001 |

| Allergic mucin# | 7.3 | 8.3 | 0.814 | 1.5 | 9.9 | 0.027 | 8.1 | 5.7 | 0.559 |

| CRSsNP | Absence % (n=96) | Presence % (n=25) | p value | Absence % (n=55) | Presence % (n=66) | p value | Absence % (n=88) | Presence % (n=33) | p value |

| Sex (female) | 53.1 | 76.0 | 0.039 | 60.0 | 56.1 | 0.662 | 55.7 | 63.6 | 0.430 |

| Headache/Migraine | 28.1 | 16.0 | 0.216 | 14.5 | 34.8 | 0.011 | 27.3 | 21.2 | 0.496 |

| Smell loss/Reduced taste | 33.3 | 36.0 | 0.802 | 23.6 | 42.4 | 0.030 | 35.2 | 30.3 | 0.610 |

| Pus# | 11.4 | 28.0 | 0.040 | 21.2 | 9.8 | 0.094 | 8.5 | 32.3 | 0.002 |

| CRSwNP | Absence % (n=111) | Presence % (n=23) | p value | Absence % (n=17) | Presence % (n=117) | p value | Absence % (n=110) | Presence % (n=24) | p value |

| Sex (female) | 32.4 | 52.2 | 0.072 | 23.5 | 37.6 | 0.258 | 36.4 | 33.3 | 0.779 |

| Headache/Migraine | 15.5 | 8.7 | 0.400 | 41.2 | 10.3 | 0.001 | 15.6 | 8.3 | 0.357 |

| Smell loss/Reduced taste | 75.5 | 56.5 | 0.065 | 52.9 | 75.0 | 0.058 | 71.6 | 75.0 | 0.734 |

| Intra-Operative Pus# | 9.7 | 13.0 | 0.635 | 13.3 | 9.9 | 0.683 | 6.7 | 27.3 | 0.004 |

The p value was determined by the Chi-square test.

All CRS: absence (n=191) and presence (n=48) of T1 endotype, absence (n=67) and presence (n=172) of T2 endotype, absence (n=186) and presence (n=53) of T3 endotype. CRSsNP, absence (n=88) and presence (n=25) of T1 endotype, absence (n=52) and presence (n=61) of T2 endotype, absence (n=82) and presence (n=31) of T3 endotype. CRSwNP, absence (n=103) and presence (n=23) of T1 endotype, absence (n=15) and presence (n=1111) of T2 endotype, absence (n=104) and presence (n=22) of T3 endotype.

We also performed multivariate logistic regression analysis and found that smell loss was associated with T2 endotype (OR 2.80, 95% CI [1.45–5.51], p<0.01) and intra-operative pus was associated with T3 endotype (OR 5.42, 95% CI [2.23–13.61], p<0.01) while controlling for age, sex, NP, atopy and asthma (Fig. 2). In addition, headache/migraine was negatively associated with T1 endotype (OR 0.28, 95% CI [0.08–0.79], p=0.03) (Fig. 2). Other clinical factors were not significantly associated with any endotype when controlling for age, sex, NP, atopy, and asthma (Fig. E1).

Figure 2. Odds ratio for clinical presentations within endotypes in all CRS.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis with predictor endotype controlling for age, sex, asthma, atopy and NP and the corresponding odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value for headache/migraine (n=230), smell loss (n=230) and intra-operative pus (n=217) in CRS. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 by logistic regression analysis.

Inflammatory endotypes associate with clinical presentations in CRSsNP

Among patients with CRSsNP, we found that smell loss and headache/migraine were significantly associated with the presence of a T2 endotype (Fig. 3A, Table 2). In addition, the presence of pus was significantly more common in T1 and T3 endotypes (Fig. 3A, Table 2). Other clinical factors were not different among the inflammatory endotypes in CRSsNP (Table E3).

Figure 3. Endotype-phenotype associations in CRSsNP and CRSwNP.

Association of clinical presentations with the absence and/or presence of all T1, T2 or T3 endotypes in CRSsNP (A) and CRSwNP (B). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 by the Chi-square test.

Inflammatory endotypes associate with clinical presentations in CRSwNP

We next analyzed CRSwNP patients and found that the T3 endotype was significantly associated with the presence of pus and the T2 endotype tended to be associated with smell loss (p=0.058) (Fig. 3B, Table 2). Interestingly, in contrast to CRSsNP, headache/migraine was lower in the presence of T2 endotype in patients with CRSwNP (Fig. 3B, Table 2). Other clinical factors were not different among the inflammatory endotypes in CRSwNP (Table E4).

Comparisons of clinical presentations between single, mixed and untypeable CRS endotypes

Since 26% of CRS patients had more than one endotype (e.g., CRS with T1 and T2 endotypes; called T1/2CRS), we were able to test whether the presence of mixed endotypes may affect the endotype-phenotype associations. The single T1 CRS endotype was rare (1.8%, n=3, Fig. 1) and was not included in the analysis. We compared the clinical presentations between patients with untypeable CRS (TunCRS) to patients with either a single endotype (T2 or T3) or mixed endotypes (T1/T2, T1/T3, or T2/T3) (Table 3). We again found that the presence of NPs, asthma, and smell loss significantly associated with the presence of a single T2 endotype (T2CRS) (Table 3). In contrast, ocular symptoms were negatively associated with T2CRS. The presence of pus and purulent nasal drainage were both significantly associated with a single T3 endotype (T3CRS) (Table 3). Other clinical factors were not different among the single inflammatory endotypes (Table E5).

Table 3.

Comparisons of clinical presentations between single or mixed and untypeable CRS endotypes in all CRS

| Single or multiple endotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TunCRS % (n=48) | T2CRS % (n=124) | T3CRS % (n=13) | T1/2CRS % (n=23) | T1/3CRS % (n=8) | T2/3CRS % (n=22) | |

| NP | 25.0 | 66.9 | 23.1 | 47.8 | 12.5 | 59.1 |

| p value | < 0.001 | 0.886 | 0.054 | 0.438 | 0.006 | |

| Asthma | 25.0 | 42.7 | 15.4 | 43.5 | 50.0 | 36.4 |

| p value | 0.031 | 0.465 | 0.115 | 0.147 | 0.329 | |

| Purulent nasal drainage | 18.8 | 16.3 | 53.8 | 21.7 | 12.5 | 18.2 |

| p value | 0.697 | 0.011 | 0.767 | 0.669 | 0.955 | |

| Smell loss/Reduced taste | 31.3 | 65.9 | 38.5 | 52.2 | 12.5 | 63.6 |

| p value | < 0.001 | 0.623 | 0.089 | 0.277 | 0.011 | |

| Eye watering/Itching | 16.7 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 12.5 | 4.5 |

| p value | 0.040 | 0.114 | 0.114 | 0.766 | 0.160 | |

| Intra-Operative Pus# | 6.8 | 5.2 | 50.0 | 21.7 | 50.0 | 26.3 |

| p value | 0.687 | < 0.001 | 0.074 | 0.001 | 0.033 | |

The p value was determined by the Chi-square test compared to TunCRS. TunCRS: undetectable elevations of T1, T2, or T3 406 inflammation.

TunCRS (n=44), T2CRS (n=116), T3CRS (n=12), T1/2CRS (n=23), T1/3CRS (n=8) and T2/3CRS (n=19).

In some instances, mixed endotypes shared similar phenotypes as single endotypes. For example, pus was present in T3CRS as well as T3 mixed endotypes (T1/3CRS and T2/3CRS) (Table 3). Smell loss and NP were present in T2CRS as well as T2 mixed endotypes (T1/2CRS and T2/3CRS), although T1/2CRS (p=0.089 and 0.054, respectively) did not reach significance (Table 3). Similar to T2CRS, asthma tended to be associated with a T2 mixed endotype (T1/2CRS), however, this did not reach significance (Table 3). In contrast, purulent nasal drainage was present in the T3 single endotype but not in T3 mixed endotypes (Table 3). This suggests that the phenotype of mixed endotypes are not necessarily a simple combination of individual endotype- associated phenotypes in CRS.

Finally, we subdivided CRS into CRSsNP and CRSwNP and analyzed the relationships between clinical presentations and either single or mixed inflammatory endotypes in both populations. However, due to low patient numbers, T1 and T3 single endotypes were excluded from the CRSwNP analysis. Among patients with CRSsNP, those with a single T3 endotype (T3sNP) or a mixed T1/T3 endotype (T1/3sNP) were more likely to have pus (Fig. 4A). Among patients with CRSwNP, those with a mixed T2/3 endotype (T2/3wNP) but not with a single T2 endotype (T2wNP) were likely to have pus (Fig. 4B). In addition, smell loss was significantly associated with the single T2 endotype (T2wNP) as well as the mixed T2/T3 endotype (T2/3wNP) (Fig. 4B). A higher prevalence of asthma was found in the mixed T1/T2 endotype (T1/2wNP) with a trend towards being elevated in the single T2 endotype (p=0.066) (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, headache and ocular symptoms were negatively associated with T2wNP and were 279 most common associated with the untypeable CRSwNP endotype (TunwNP) (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Endotype-phenotype association in single, mixed and untypeable endotypes of CRSsNP and CRSwNP.

Comparison of clinical presentations between untypeable, single or mixed endotypes in CRSsNP (A) and CRSwNP (B). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 by the Chi-square test.

DISCUSSION

The division of CRS into two major phenotypes, CRSsNP and CRSwNP, is widely accepted, and the patterns of inflammatory endotypes in these two CRS phenotypes are known to be different.7–9, 11 While associations between endotype and phenotype in asthma have been well studied in the past decade,16–21, 24 these associations in CRS have only begun to be examined. Tomassen et al. found that the presence of T2 inflammation with Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin–specific IgE was highly associated with CRSwNP and asthma.8 Likewise, Turner et al. found that T2 inflammation was associated with presence of NPs and asthma.22 Although previous studies identified this association between T2 inflammation and presence of NPs and asthma, it was not known whether T2 inflammation was associated with other clinical presentations, or whether T1 and T3 inflammation were associated with other distinct clinical phenotypes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report how T3 inflammation influences clinical presentations in CRS. Furthermore, we have identified new associations between T2 inflammation and clinical presentations in CRS.

In the present study, we first confirmed the published observations that T2 inflammation was associated with the presence of NPs and asthma comorbidity in CRS (Table 2). This suggests that CRS patients in this study were typical of the general CRS population in the US. Interestingly, we also found that the T1 and T2 mixed endotype (T1/2wNP) showed the highest asthma comorbidity in CRSwNP but not in CRSsNP (Fig. 4B and not shown). Although we did not investigate asthma phenotypes in the present study, CRSwNP with a mixed T1 and T2 endotype may correspond to a unique phenotype of asthma. Further studies will be required to identify the association between asthma and CRS phenotypes and endotypes as well as the endotype of asthma associated with CRS endotypes.

In addition to the presence of NP and asthma comorbidity, we identified that smell loss was strongly associated with the T2 endotype. We recently found that complaints of smell/taste loss were significantly higher in eosinophilic CRS (78% were patients with CRSwNP) and that expression of an eosinophil marker, CLC, in superior turbinate correlated with olfactory defect in CRS.25, 26 These studies may suggest that T2 inflammation promotes smell loss in CRS. However, smell loss is also well known to be associated with the presence of NPs,1 and therefore it was not clear whether the T2 inflammation was just a marker of NPs or whether the T2 inflammation was instead more directly associated with smell loss. In our present study, we found that T2 inflammation was also associated with smell/taste loss in CRSsNP (Fig. 3). Furthermore, smell loss was still associated with T2 endotype while controlling for asthma and presence of NPs (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the symptoms of smell/taste loss may be directly induced by T2 inflammation. It will be valuable to investigate how T2 inflammation mediates olfactory defects.

In contrast to the presence of asthma and olfactory defects, headaches and migraines were differentially reported in CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients with a T2 endotype. We found that the presence of T2 inflammation positively associated with headache and migraine in CRSsNP while they negatively associated in CRSwNP (Fig. 3). This suggests that a subset of endotype-phenotype associations is affected by the presence (or absence) of NPs.

This study also provides the first evidence suggesting that T3 inflammation is associated with the presence of pus and purulent nasal drainage in CRS. The intraoperative finding of pus was almost always associated with T3 inflammation in both CRSsNP and CRSwNP. Multivariate analysis also supported the direct link between T3 inflammation and pus in CRS (Fig. 2). However, documentation of symptoms of purulent nasal drainage was only associated with the T3 single endotype (Table 3). Since endoscopic sinus surgery facilitates the direct inspection of sinus contents, we believe it is a more sensitive measure of purulence than relying on the patient’s ability to identify purulent nasal discharge and may explain why purulent nasal drainage was less strongly associated with T3 inflammation.

CRS is one of the diseases for which antibiotics are commonly prescribed and accounts for 7.1% of all primary diagnoses for ambulatory care visits with antibiotic prescriptions, despite limited evidence of efficacy.27 This level of overuse may lead to the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Importantly, T3 (Th17) immunity is very important for protection against bacteria and fungi.28, 29 In addition, purulent nasal drainage and pus are common symptoms associated with bacterial infections, and we found that these symptoms were associated with the T3 endotype in CRS. Together, our findings may suggest that the T3 endotype in CRS is most strongly associated with bacterial infection, and, importantly, that T3CRS patients may be the most responsive to treatment with antibiotics. This possibility may generate a more precise and personalized medical strategy for this subset of CRS patients. Several studies have suggested a central role for IL-17, Th17 cells and group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s) in severe neutrophilic asthma that is generally characterized by steroid insensitivity.30 From this we can infer that T3CRS may also be characterized by neutrophilic inflammation in the sinonasal mucosa and be resistant to glucocorticoid treatments. Future study will be required to identify whether the T3 endotype is associated with bacterial infection in CRS, whether T3CRS patients are responsive to antibiotic treatment and whether T3CRS patients have neutrophilic inflammation with resistance to glucocorticoid treatments.

We found that 30% of CRSsNP and 9% of CRSwNP patients were untypeable using the current endotyping markers (Fig. 1). Interestingly, we also found distinct clinical presentations in these untypeable patients, especially in CRSwNP. Ocular tearing and pruritus were more common in TunCRS compared to T2 and T3 single endotypes in all CRS (Table 3) and compared to T2 single and T2 mixed endotypes in CRSwNP (Fig. 4B), although some comparisons did not reach significance. In addition, headache/migraine was significantly associated with TunwNP (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the untypeable group may have one or more unrecognized endotypes independent of T cell-associated cytokines. Further study will be required to examine whether there are any biomarkers (such as non-T cell associated cytokines or chemokines) that could identify potential new endotypes in untypeable CRS.

Although we showed clear evidence that inflammatory endotypes are associated with distinct clinical presentations in CRS, our present study has certain limitations. We have purposefully selected the method used for identification of endotypes in this study. In the case of published asthma studies, most investigators used periostin, CCL26, eosinophil numbers and FeNO level as biomarkers to identify T2 endotype, since the levels of T cell associated cytokines were not high in tissue.31–33 In our present study however, we used ECP and CLC, which are very sensitive markers of eosinophils, to determine the T2 endotype in CRS and we were able to use the canonical T cell-associated cytokines IFN-γ and IL-17A for the determination of T1 and T3 inflammation, respectively. It is possible that there are some false negative calls in our data set, i.e. patients whose disease was driven by T1 or T3 cytokines but were nonetheless assigned to the untypeable group. Future study is required to identify more sensitive biomarkers of T1 and T3 endotypes in CRS to diminish the possibility of such false negatives. Another limitation is that the study was performed only in patients undergoing surgery, and we did not control for systemic or topical corticosteroids and antibiotics use perioperatively. These medications could have affected our findings. Future studies in a primary population of CRS patients and studies on the effect of medications would be worthwhile.

In conclusion, we report that a subset of clinical presentations were directly associated with inflammatory endotypes in CRS. Identification of inflammatory endotypes may help in the diagnosis of CRS phenotypic groups and may be useful for the future design of more precise and personal medicine strategies that effectively prevent or treat disease in CRS patients.

Supplementary Material

Highlights Box.

What is already known about this topic?

Clinically, patients with CRS present with a variety of symptoms including rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, smell loss, and/or facial pressure/pain. Additionally, the sinonasal tissue of CRS patients is characterized by a heterogeneous pattern of inflammation.

What does this article add to our knowledge?

This study investigates the associations between various inflammatory endotypes and clinical phenotypes in CRS and demonstrates that certain inflammatory markers can be linked with particular clinical signs and symptoms.

How does this study impact current management guidelines?

The identified association of certain inflammatory endotypes with specific clinical presentations can be useful in the diagnosis of CRS. Identifying and understanding these associations could lead to improved targeted therapies and more personalized treatment options for patients with CRS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grants, R01 AI104733, KL2 TR001424, R37 HL068546, R01 AI137174 and U19 AI106683 and by grants from the Parker B. Francis Fellowship Foundation, the HOPE APFED/AAAAI Pilot Grant Award and the Ernest S. Bazley Foundation.

We would like to gratefully acknowledge Ms. Lydia Suh, Mr. James Norton, Mr. Roderick Carter, Ms. Caroline P.E. Price Ms. Julia H. Huang and Ms. Kathleen E. Harris (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine) for their skillful technical assistance. We would like to gratefully acknowledge Ms. Chen Yeh, MS at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine for her support of statistical analysis.

Funding: This research was supported in part by NIH grants, R01 AI104733, KL2 TR001424, R37 HL068546, R01 AI137174 and U19 AI106683 and by grants from the Parker B. Francis Fellowship Foundation, the HOPE APFED/AAAAI Pilot Grant Award and the Ernest S. Bazley Foundation.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- CLC

Charcot-Leyden crystal galectin

- CRS

Chronic rhinosinusitis

- CRSsNP

CRS without nasal polyps

- CRSwNP

CRS with nasal polyps

- ECP

Eosinophil cationic protein

- FESS

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery

- NP

Nasal polyp

- OR

Odds ratio

- T1

Type 1

- T2

Type 2

- T3

Type 3

- TunCRS

Untypeable CRS

- TunsNP

Untypeable CRSsNP

- TunwNP

Untypeable CRSwNP

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest as to the interpretation and presentation of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl 2012; 23:3 p preceding table of contents, 1–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlandi RR, Kingdom TT, Hwang PH, Smith TL, Alt JA, Baroody FM, et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2016; 6 Suppl 1:S22–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KA, Orlandi RR, Rudmik L. Cost of adult chronic rhinosinusitis: A systematic review. Laryngoscope 2015; 125:1547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudmik L Economics of Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2017; 17:20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato A Immunopathology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol Int 2015; 64:121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens WW, Ocampo CJ, Berdnikovs S, Sakashita M, Mahdavinia M, Suh L, et al. Cytokines in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Role in Eosinophilia and Aspirin-exacerbated Respiratory Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192:682–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan BK, Klingler AI, Poposki JA, Stevens WW, Peters AT, Suh LA, et al. Heterogeneous inflammatory patterns in chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps in Chicago, Illinois. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:699–703 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomassen P, Vandeplas G, Van Zele T, Cardell LO, Arebro J, Olze H, et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137:1449–56 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Zhang N, Bo M, Holtappels G, Zheng M, Lou H, et al. Diversity of TH cytokine profiles in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: A multicenter study in Europe, Asia, and Oceania. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138:1344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benjamin MR, Stevens WW, Li N, Bose S, Grammer LC, Kern RC, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis without Nasal Polyps in an Academic Setting. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7:1010–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyler MA, Russell CB, Smith DE, Rottman JB, Padro Dietz CJ, Hu X, et al. Large-scale gene expression profiling reveals distinct type 2 inflammatory patterns in chronic rhinosinusitis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:1061–4 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner JH, Chandra RK, Li P, Bonnet K, Schlundt DG. Identification of clinically relevant chronic rhinosinusitis endotypes using cluster analysis of mucus cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141:1895–7 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan BK, Chandra RK, Pollak J, Kato A, Conley DB, Peters AT, et al. Incidence and associated premorbid diagnoses of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:1350–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch AG, Yan XS, Sundaresan AS, Tan BK, Schleimer RP, Kern RC, et al. Five-year risk of incident disease following a diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy 2015; 70:1613–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole M, Bandeen-Roche K, Hirsch AG, Kuiper JR, Sundaresan AS, Tan BK, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of clustering of chronic sinonasal and related symptoms using exploratory factor analysis. Allergy 2018; 73:1715–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore WC, Hastie AT, Li X, Li H, Busse WW, Jarjour NN, et al. Sputum neutrophil counts are associated with more severe asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133:1557–63 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modena BD, Tedrow JR, Milosevic J, Bleecker ER, Meyers DA, Wu W, et al. Gene expression in relation to exhaled nitric oxide identifies novel asthma phenotypes with unique biomolecular pathways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190:1363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modena BD, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Erzurum SC, Gaston BM, Jarjour NN, et al. Gene Expression Correlated with Severe Asthma Characteristics Reveals Heterogeneous Mechanisms of Severe Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195:1449–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefaudeux D, De Meulder B, Loza MJ, Peffer N, Rowe A, Baribaud F, et al. U-BIOPRED clinical adult asthma clusters linked to a subset of sputum omics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:1797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo CS, Pavlidis S, Loza M, Baribaud F, Rowe A, Pandis I, et al. T-helper cell type 2 (Th2) and non-Th2 molecular phenotypes of asthma using sputum transcriptomics in U-BIOPRED. Eur Respir J 2017; 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hekking PP, Loza MJ, Pavlidis S, de Meulder B, Lefaudeux D, Baribaud F, et al. Pathway discovery using transcriptomic profiles in adult-onset severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141:1280–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner JH, Li P, Chandra RK. Mucus T helper 2 biomarkers predict chronic rhinosinusitis disease severity and prior surgical intervention. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2018; 8:1175–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens WW, Peters AT, Suh L, Norton JE, Kern RC, Conley DB, et al. A retrospective, cross-sectional study reveals that women with CRSwNP have more severe disease than men. Immun Inflamm Dis 2015; 3:14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahy JV. Eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation in asthma: insights from clinical studies. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009; 6:256–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson CF, Price CP, Huang JH, Min JY, Suh LA, Shintani-Smith S, et al. A pilot study of symptom profiles from a polyp vs an eosinophilic-based classification of chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2016; 6:500–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavin J, Min JY, Lidder AK, Huang JH, Kato A, Lam K, et al. Superior turbinate eosinophilia correlates with olfactory deficit in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Laryngoscope 2017; 127:2210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith SS, Evans CT, Tan BK, Chandra RK, Smith SB, Kern RC. National burden of antibiotic use for adult rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132:1230–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abusleme L, Diaz PI, Freeman AF, Greenwell-Wild T, Brenchley L, Desai JV, et al. Human defects in STAT3 promote oral mucosal fungal and bacterial dysbiosis. JCI Insight 2018; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rathore JS, Wang Y. Protective role of Th17 cells in pulmonary infection. Vaccine 2016; 34:1504–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chesne J, Braza F, Mahay G, Brouard S, Aronica M, Magnan A. IL-17 in severe asthma. Where do we stand? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190:1094–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters MC, Mekonnen ZK, Yuan S, Bhakta NR, Woodruff PG, Fahy JV. Measures of gene expression in sputum cells can identify TH2-high and TH2-low subtypes of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133:388–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silkoff PE, Laviolette M, Singh D, FitzGerald JM, Kelsen S, Backer V, et al. Identification of airway mucosal type 2 inflammation by using clinical biomarkers in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140:710–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corren J, Parnes JR, Wang L, Mo M, Roseti SL, Griffiths JM, et al. Tezepelumab in Adults with Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:936–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.