ABSTRACT

Background

Drugs are very important in the etiology of nontraumatic rhabdomyolysis.

Case descriptions

A 16-year-old male patient with Wilson's disease was admitted for myoclonic contractions. Oral trientine was started for neurological problems and tremor on the hands due to D-penicillamine 1 month ago. Patient was oligoanuric, and his creatine kinase level was 15197 U/L. Rhabdomyolysis was associated with trientine, and trientine treatment was stopped. Hemodiafiltration was performed. The patient began to urinate on the 24th day.

Conclusion

This is the first pediatric patient with rhabdomyolysis induced by trientine. Drugs used should be questioned carefully in patients with rhabdomyolysis.

How to cite this article

Aslan N, Yavuz S, Yildizdas D, Horoz OO, Coban Y, Tumgor G, et al. Trientine-induced Rhabdomyolysis in an Adolescent with Wilson's Disease. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23(10):489–490.

Keywords: Continued renal replacement therapy, Rhabdomyolysis, Trientine

INTRODUCTION

Rhabdomyolysis is known as a syndrome that destroys the integrity of the sarcolemma as a result of musculoskeletal damage due to traumatic or nontraumatic reasons.1 Musculoskeletal degeneration is held responsible for 5–7% of the cases that develop acute renal failure.2 Etiology includes medications, hereditary muscle enzyme deficiencies, trauma, viral infections, excessive exercise and hypothyroidism.3 Colchicine, lithium and statins are the most commonly accused agents; however, trientine is a rare drug that should also be kept in mind in the etiology of rhabdomyolysis.4 In the present case report, we report an adolescent patient with Wilson's disease who presented with rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure induced by trientine.

CASE DESCRIPTION

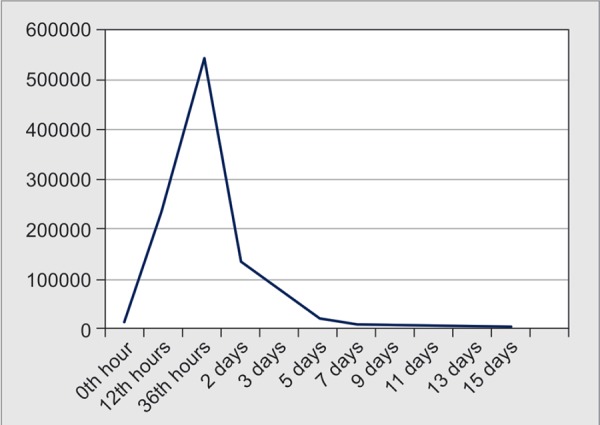

A 16-year-old male patient with Wilson's disease who was followed-up at pediatric gastroenterology for 5 years admitted to the pediatric emergency department for myoclonic contractions on the whole body. From the review of the patient's history, it was detected that the patient was using D-penicillamine as a chelating agent. D-penicillamine was discontinued, and trientine treatment was initiated due to neurological problems and tremor on the hands while the patient was using D-penicillamine until 1 month before. In the first physical examination in the pediatric emergency department, pulse was 98/min, respiratory count was 24/min, and TA was 130/85 mm Hg. The eyeballs were sunken, the skin reduced turgor, and deep tendon reflexes were normoactive. Values in the complete blood count were as follows: hemoglobin: 14 g/dL, platelet count: 250.000/µL, leukocyte count: 24.400/µL. In the urine analysis, density was 1035, and protein 3+ and abundant erythrocytes were determined in microscopy. The biochemical tests revealed the followings: BUN 60 mg/dL, creatinine 2.34 mg/dL, uric acid 9.5 mg/dL, sodium 139 mmol/L, potassium 5.2 mmol/L, phosphorus 8 mg/dL, AST 5053 U/L, ALT 6398 U/L, LDH 1400 U/L, and creatinine clearance 13.5 mL/min. Complements (C3, C4) and IgA values were within the normal range, and viral serology was negative. Prothrombin time was 15.1 seconds, aPTT was 29 seconds, fibrinogen was 281 mg/dL, and the direct Coombs test was negative. Blood gas values were as follows: pH 7.32, pCO2 29, HCO3 14.9, and BE –10.1. Creatine kinase (CK) level was 15197 U/L, and myoglobin in the blood and urine was above 3900 ng/mL. The echocardiographic evaluation was found to be normal; dimensions of the kidneys were normal on the urinary system ultrasonography, and an increase in parenchyma echogenicity (consistent with grade II parenchymal disease) was noted. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure were considered, so the patient was not hydrated. He was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit with the diagnosis of acute renal failure due to rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis was associated with trientine, and trientine treatment was stopped. The CK value of the patient increased up to 546.326 at the 36th hour of hospitalization and then followed a falling trend (Fig. 1). Continued renal replacement therapy was started, and hemodiafiltration was performed with a 12 Fr hemodialysis catheter placed in the internal jugular vein for 3 days. Then, the patient was taken to the routine hemodialysis program for 3 days a week. The patient began to urinate on the 24th day of intensive care unit admission. Creatinine levels gradually decreased and normalized on day 28. Written informed consent was obtained from the family.

Fig. 1.

CK levels measurements

DISCUSSION

Rhabdomyolysis may occur due to traumatic reasons such as earthquakes, electric shocks or mining accidents or due to many different reasons such as alcoholism and medication use (especially statins), excessive physical activity, long-term lack of movement, epileptic seizures, hyperthermia, hypothermia, infections and electrolyte imbalances (especially hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia). Rhabdomyolysis is also seen in many congenital metabolic diseases, glycolytic enzyme deficiency diseases, some diseases with abnormal lipid metabolism and malignant hyperthermia.2 Drugs should be considered in the etiology of rhabdomyolysis. Our patient started using trientine 1 month ago. We associated the rhabdomyolysis clinic of the patient with this newly added treatment.

Trientine dihydrochloride is widely used for the management of Wilson's disease. It is a cupriuretic agent and acts by promoting the urinary excretion of copper from the kidneys.5 Trientine used as a second line therapy in Wilson's disease is usually preferred for patients who are intolerant to the D-penicillamine.6 The adverse effects of trientine are rare, but they are severe conditions such as reversible sideroblastic anemia, lupus like reaction, dystonia, muscular spasm, myasthenia gravis and rhabdomyolysis.7 In a PubMed-based literature review, we found an adult patient with rhabdomyolysis associated with trientine. In one case series with four patients treated with trientine, hydrochloride for primary biliary cirrhosis and adverse reactions were reported, including heartburn, epigastric pain and tenderness, thickening, fissuring, and flaking of the skin, hypochromic microcytic anemia, acute gastritis, aphthous ulcers, abdominal pain, melena, anorexia, cramps, muscle pain and weakness. One patient developed acute rhabdomyolysis within 48 hours of receiving the first trientine dose for rhabdomyolysis. Due to the side effects, trientine was discontinued in all four patients.4

In conclusion, trientine-induced rhabdomyolysis is quite rare but is a life-threatening condition. In the present case, we considered a trientine-induced rhabdomyolysis and stopped the treatment. To the best of our knowledge, our case is the first patient in the pediatric age group with rhabdomyolysis induced by trientine. Drugs used in patients with rhabdomyolysis should be questioned carefully, and trientine should be kept in mind for etiology.

“Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's legal guardian(s) for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.”

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The idea for the manuscript was conceived at a meeting in September 2018 chaired by Nagehan Aslan, and was attended by Sibel Yavuz, Dincer Yildizdas, Ozden Ozgur Horoz and Gokhan Tumgor. Nagehan Aslan wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Dincer Yildizdas, Gokhan Tumgor, and Aysun Karabay Bayazit all reviewed the manuscript and were involved in its critical revision before submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank to the patient and her family for their permission for using their data in this case report.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Vanholder R, Sever MS, Erek E, Lameire N. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1553–1561. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1181553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward MM. Factors predictive of acute renal failure in rabdomyolisis. Arch İntern Med. 1998;148:1553–1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melli G, Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR. Rhabdomyolysis: an evaluation of 475 hospitalized patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005;84:377–385. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000188565.48918.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein O, Sherlock S. Triethylene tetramine dihydrochloride toxicity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1980;78(6):1442–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu J. Triethylenetetramine pharmacology and its clinical applications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2458–2467. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalvi A, Padmanaban M. Wilson's disease: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Dis Mon. 2014;60:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson's disease. J Hepatol. 2012;56:671–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]