Abstract

We report a novel phenomenon produced by focused ultrasound (US) that may be important for understanding its effects on cell membranes. When a US burst (2.1 MHz, 1-mm focal diameter, 0.1–1 MPa) was focused on a motor axon of the crayfish neuromuscular junction, it consistently produced a fast hyperpolarization, which was followed or superseded by subthreshold depolarizations or action potentials in a stochastic manner. The depolarization persisted in the presence of voltage-gated channel blockers [1 µM TTX (INa), 50 µM ZD7288 (Ih), and 200 µM 4-aminopyridine (IK)] and typically started shortly after the onset of a 5-ms US burst, with a mean latency of 3.35 ± 0.53 ms (SE). The duration and amplitude of depolarizations averaged 2.13 ± 0.87 s and 10.1 ± 2.09 mV, with a maximum of 200 s and 60 mV, respectively. The US-induced depolarization was always associated with a decrease in membrane resistance. By measuring membrane potential and resistance during the US-induced depolarization, the reversal potential of US-induced conductance (gus) was estimated to be −8.4 ± 2.3 mV, suggesting a nonselective conductance. The increase in gus was 10–100 times larger than the leak conductance; thus it could significantly influence neuronal activity. This change in conductance may be due to stimulation of mechanoreceptors. Alternatively, US may perturb the lateral motion of phospholipids and produce nanopores, which then increase gus. These results may be important for understanding mechanisms underlying US-mediated modulation of neuronal activity and brain function.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We report a specific increase in membrane conductance produced by ultrasound (US) on neuronal membrane. When a 5-ms US tone burst was focused on a crayfish motor axon, it stochastically triggered either depolarization or a spike train. The depolarization was up to 60 mV in amplitude and 200 s in duration and therefore could significantly influence neuronal activity. Depolarization was still evoked by US burst in the presence of Na+ and Ca2+ channel blockers and had a reversal potential of −8.4 ± 2.3 mV, suggesting a nonselective permeability. US can be applied noninvasively in the form of a focused beam to deep brain areas through the skull and has been shown to modulate brain activity. Understanding the depolarization reported here should be helpful for improving the use of US for noninvasive modulation and stimulation in brain-related disease.

Keywords: axon, biological membrane, focused ultrasound, membrane conductance, neuromodulation

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasound (US) has now emerged as an important modality for modulating neuronal functions in the brain. A focused US beam can be applied noninvasively from outside the head to any region of the brain (Aubry et al. 2003; Clement and Hynynen 2002; Elias et al. 2013; Hynynen et al. 2005; McDannold et al. 2010; Sun and Hynynen 1999). Unlike transcranial magnetic or electrical stimulation, the US beam can be focused deep in the brain while maintaining a narrow focal point, 1–3 mm in full-width half-maximum at 1 MHz. Moreover, US bursts have been shown to modulate neuronal activity within FDA safety limits (Tufail et al. 2010, 2011; Tyler et al. 2008). Thus US has many attractive features over existing noninvasive neuromodulation techniques.

Three mechanisms have been proposed as the basis for US-based neuromodulation: 1) modulation of membrane capacitance (Krasovitski et al. 2011; Plaksin et al. 2016; Prieto et al. 2013), 2) modulation of membrane conductance associated with transient nanopores of cell membranes (Böckmann et al. 2008; Heimburg 2010), and 3) modulation of conductance of mechanoreceptors, voltage-gated channels (VGCs), or ligand-gated ion channels (Kubanek et al. 2016, 2018). Although these studies have provided insights into the potential mechanisms of US-activated neuronal responses, their conclusions were based on simulations or experiments using lipid bilayers or heterologous expression systems. Studies using neuronal tissues, mostly monitoring compound action potentials (APs) in peripheral nerves, have predominantly suggested an inhibitory role of US (Colucci et al. 2009; Mihran et al. 1990; Tsui et al. 2005; Young and Henneman 1961). However, studies in complex neuronal preparations, such as whole animals or brain slices, have suggested that US mostly triggered excitatory outcomes (King et al. 2013; Menz et al. 2013; Tufail et al. 2010; Tyler et al. 2008), although an inhibitory effect of US on the central nervous system has also been reported (Fry et al. 1958). Overall, the physiological basis of the modulation at a single-cell level is still poorly understood, and behavioral effects are controversial (Guo et al. 2018; Sato et al. 2018). In this report, we have chosen a simple neuronal preparation that allows us to examine US-mediated neuromodulation with intracellular recordings from single axons.

The crayfish opener preparation contains two motor axons, one excitatory and one inhibitory. Both axons branch extensively to innervate every muscle fiber that controls the opening of the claw of the first walking leg. The axons are large and allow for two-electrode current clamp from two locations simultaneously (Lin 2008, 2012). These technical advantages have been exploited to demonstrate that Na+, Ca2+, and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)-sensitive K+ channels have nonuniform densities along the proximo-distal axis (Delaney et al. 1991; Lin 2012, 2013, 2016). The preparation is hardy and allows for stable intracellular recordings for up to 36 h (Lin 2008). Thus this system is functionally and morphologically “realistic” yet sufficiently simple for investigating how US may affect axonal excitability and synaptic transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and Recording

Crayfish, Procambarus clarkii, were purchased from Niles Biological Supplies (Sacramento, CA). Small animals of both sexes, 5–7 cm head to tail, were maintained in tap water at room temperature (22°C). All experiments were performed at the same temperature. The first walking leg was removed by autotomy and fixed with crazy glue, dactylopodite side down, to a 50-mm petri dish. The opener axon-muscle preparation was dissected in saline. Since the upper half of the shell of the carpopodite was removed, the access of pharmacological agents to the entire length of the axons was nearly instantaneous. Both the excitatory and inhibitory axons were used in this study.

Physiological saline contained (in mM) 195 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 13.5 CaCl2, 2.6 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The saline was circulated by a peristaltic pump at the rate of 1 ml/min. 4-AP stock solution (1 M) was dissolved in distilled water. Stock solutions for tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1 mM) and ZD7288 (50 µM) were dissolved in distilled water and DMSO, respectively. The stock solutions were stored at −20C° and added to the saline directly. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Since blockers were added to circulating saline, 15 min was sufficient to achieve steady levels of blockade. US-induced responses were similar in axons in control saline and those recorded after the blockers were washed out.

In this report, each preparation represents a recording session from a motor axon dissected from an animal. A recording session typically lasted 2–4 h, and US stimuli were delivered in 20-s cycles, each cycle consisting of a 10-s recorded trace followed by a 10-s interval before the next recording. Preparations used in this report can be grouped into three subsets based on pharmacological and experimental protocols. Group 1 (n = 6; Fig. 1, Fig. 4, and Fig. 5) US-induced responses were recorded in control saline and then in the presence of TTX (1 µM) and Cd2+ (200 µM) to block inward current. Groups 2 and 3 were treated with TTX (1 µM), 4-AP (200 µM), and ZD7288 (50 µM). Group 2 (n = 11; Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) axons were used to generate a statistical summary of electrophysiological parameters of US-activated depolarization, and group 3 (n = 5, Fig. 6) axons were probed with ramp current injection to assess input resistance (Rin) changes during US-induced depolarization.

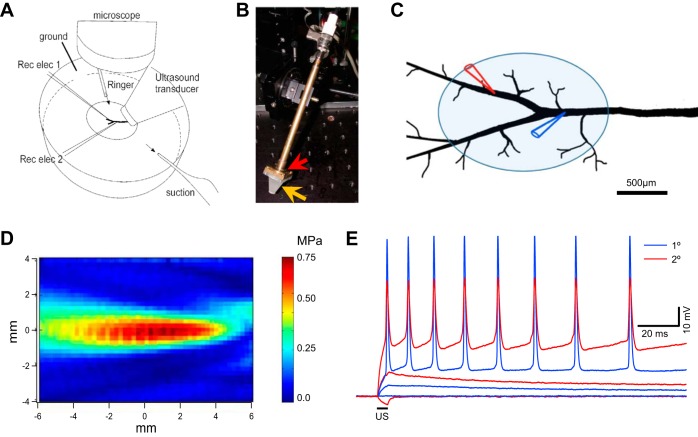

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup and ultrasound-induced changes in membrane potential in crayfish motor axons. A: illustration of the crayfish opener neuromuscular preparation, microelectrodes (Rec elec 1 and 2), and ultrasound (US) transducer placements. B: photograph of the US transducer mounted on a motorized manipulator. The piezo disk is housed in a brass holder (red arrow), and the Rexolite cone (orange arrow) is fastened to the brass housing with screws. C: detailed 2-electrode current clamp configuration, with 1 electrode at the primary branch (blue) and the second electrode at the secondary branch (red). Also shown is the approximate footprint of a typical US focal area when the transducer is angled at 45° (shaded ellipse). The dimensions of the axon are equivalent to a preparation dissected from an animal 60 cm in length head to tail. D: 2-dimensional side profile of the focused US beam produced by the 2.1-MHz US transducer, measured with a hydrophone in a chamber (150 × 50 × 50 cm) filled with degassed water. E: simultaneous intracellular recording from the primary (blue) and secondary (red) branches of an inhibitory axon. The US burst [2.1 MHz, 5 ms, and 0.4 MPa (2.7 mW/cm2)] induced a hyperpolarization and subthreshold and suprathreshold responses in 3 consecutive trials. membrane potential = −75 mV.

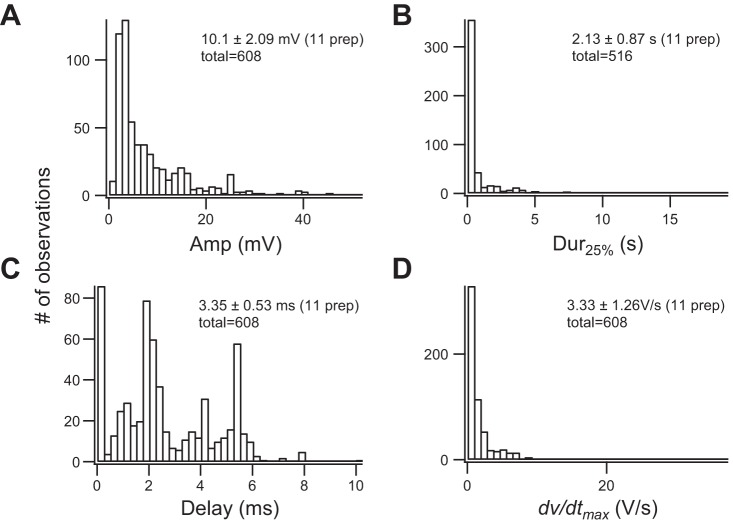

Fig. 4.

Summary of ultrasound (US)-induced depolarizations. Distributions of amplitudes (A), durations (B), delays (C), and maximal rates of rise (dV/dt; D) recorded from 11 animals and 608 depolarizations are summarized. All recordings were obtained in the presence of tetrodotoxin (1 µM), 4-aminopyridine (200 µM), and ZD7288 (50 µM). All preparations had been equilibrated with the blockers for at least 15 min before data collection started. Sample size, average, and SE of each parameter are listed for each parameter (see text for details). B has a smaller sample size because some US-induced responses had durations that outlasted the length of sampled traces. Percentages of US positive responses in these animals ranged from 4% to 39%, with an average of 14.6 ± 9.4% (n = 11), and the total number of trials, including positive and negative responses, used to calculate the average in each preparation ranged from 46 to 1,548 with an average of 469 ± 416. Intensity of the spatial peak temporal average in these preparations ranged from 4.2 to 9.4 mW/cm2.

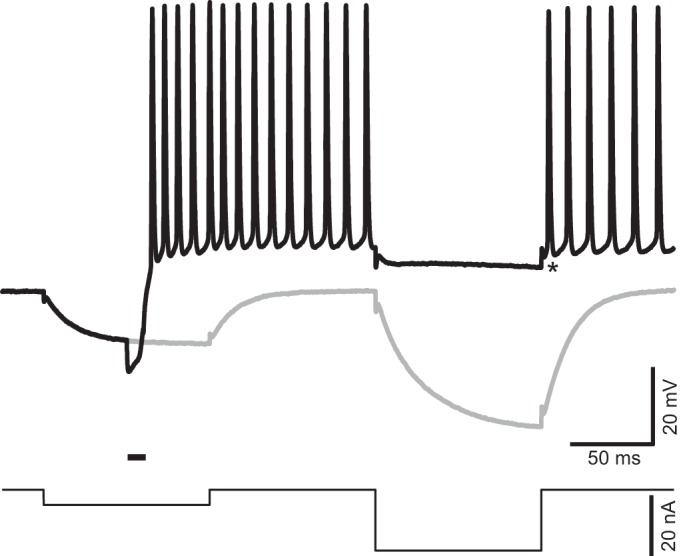

Fig. 5.

Ultrasound (US)-induced depolarization is associated with a reduction in membrane resistance. US-induced responses were investigated with a double current step protocol (bottom) including two 100-ms current steps −5 and −20 nA in amplitude, respectively, separated by an interval of 100 ms. The 2 current steps generated passive membrane responses in the absence of US stimulation (gray). A US burst delivered during a first current step induced repetitive firing (black). This firing was silenced by the second hyperpolarizing step, which only generated a small hyperpolarization. Asterisk identifies the baseline used to measure the amplitude of hyperpolarization (−4 mV) that silenced the firing. Horizontal bar above the current trace indicates the timing of US stimulation, namely, 10 ms at 2.0 MHz, and intensity of spatial peak temporal average = 7.7 mW/cm2.

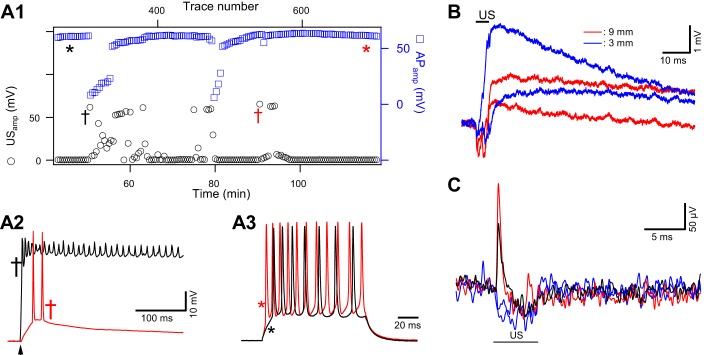

Fig. 2.

Stochastic nature of ultrasound (US)-induced responses and assessment of functional integrity of motor axons exposed to repeated 5-ms US tone bursts. A: test of action potential (AP) stability and axon viability during US-induced responses. A1: timeline plot of amplitudes of US induced depolarizations (USamp, black circles) from an inhibitory axon. Plot illustrates the stochastic and clustering nature of the responses. Axonal excitability was tested with suprathreshold current steps, inserted between US tone burst deliveries. AP amplitudes (APamp, blue squares), measured from resting membrane potential, remained constant except during the periods in which US induced prolonged depolarizations and reduced membrane resistance. The US tone burst, 5 ms at 2.1 MHz and 6.5 mW/cm2, was delivered at a rate of 0.1 Hz. x-Axes include trace number (top) and corresponding time (bottom). The same current injection amplitude (15 nA) was used over the entire experimental period. A2: 2 representative examples of US-induced depolarizations. Red and black traces correspond to the times marked by the daggers of matched colors in A1. Arrowhead indicates the timing of US delivery. A3: 2 representative examples of current step-induced AP trains, corresponding to the time points marked with asterisks in A1. APs were initiated by current injection at the primary branch and recorded at a secondary branching point. There was a slight increase in the number of APs over time (red), suggesting a slight increase in input resistance. There was no channel blocker in this preparation. A2 and A3 share the same vertical scale. B: depolarizations recorded from an axon where US focal points were displaced away from the recording electrode. Depolarizations were recorded from the primary branching point. The proximal part of the axon in this preparation had been preserved, ~10 mm in length. Depolarizations were still detected when the US transducer was moved horizontally along the axon by 3 mm (blue) and 9 mm (red) away from the primary branching point. Two traces are shown for each location to demonstrate the consistency of evoked responses. US delivery time is indicated by the black bar. US intensity was 8.9 mW/cm2. C: extracellular recordings, at 5 kHz filtering, uncovered transients coinciding with the onset of US bursts. US burst duration was 5 ms and intensity 9.0 mW/cm2. These events were rare, occurring in 2 of 55 trials. Red and black traces represent 2 examples of US-positive responses, and blue traces represent US-negative responses. Data in A, B, and C were obtained from different preparations.

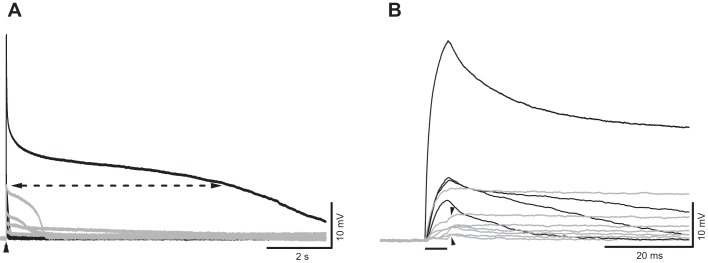

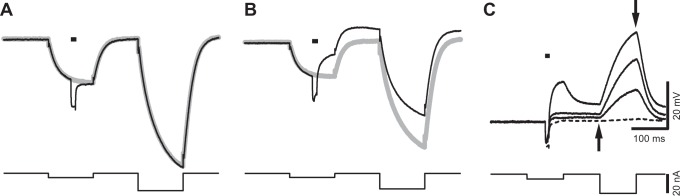

Fig. 3.

Variations in ultrasound (US)-induced membrane responses. A: US responses recorded from an axon treated with tetrodotoxin (1 µM), 4-aminopyridine (200 µM), and ZD7288 (50 µM). Recordings were obtained from 2 different clusters of US-induced responses, in black and gray, respectively. Arrowhead indicates US delivery time. Dashed line identifies the 25% level of the peak amplitude of the largest response, as an example of how duration measurements were made. B: same traces as in A but displayed in an expanded timescale. Horizontal bar indicates timing of the US burst. Arrowheads indicate that additional depolarization can occur at the end of US bursts. Intensity of spatial peak temporal average = 8.1 mW/cm2.

Fig. 6.

Ultrasound (US)-induced depolarization correlates with a reduction in membrane resistance. A: a trial in which US (black bar) only induced hyperpolarization and there was no change in membrane resistance. The current injection pattern (bottom) is the same as that shown in Fig. 4. B: a trial in which US-induced depolarization was associated with a reduction in membrane resistance (black). C: isolation of US-induced depolarization and corresponding decrease in input resistance (Rin) by subtracting traces recorded in the absence of US (gray in A and B) from those with US application (black in A and B). Dashed trace in C was obtained from the trial in A where US induced only hyperpolarization and shows no change in the difference trace, or Rin, during the test current pulse (up and down arrows). The remaining 3 traces show that the amplitude of US-induced depolarization correlates with the magnitude of changes in Rin. Horizontal bar above the voltage traces indicates the timing of US stimulation. These recordings were obtained in the presence of tetrodotoxin (1 µM), 4-aminopyridine (200 µM), and ZD7288 (50 µM). All US-induced changes in depolarization and Rin were evoked by US bursts of the same intensity as that in Fig. 4.

Two microelectrode amplifiers (Warner IE-210) were used to perform two-electrode current clamp. Voltage signals were filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 20 µs. Data were digitized with a NI 6251 board and analyzed with IGOR (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Microelectrodes were filled with 500 mM K methanesulfonate or KCl and had a resistance of 40–60 MΩ. Axon penetration was performed under a ×60 water immersion lens on a fixed-stage microscope (Olympus BX51). The typical resting membrane potential (Vm) was −70 to −80 mV.

Because of spatial constraints, the two electrodes approached axons from the same distal-to-proximal direction while the US transducer approached the preparation from the opposite direction (Fig. 1A). Thus the microelectrode tips were pointed at the US transducer. The water immersion lens used during axon penetrations was removed to make room for the US transducer. The transducer was positioned at 45°, and microelectrodes at 28°, to the horizontal plane. The US transducer was brought as close to the preparation as possible, with the lower edge of the US transducer cone ~1 mm from the bottom of the recording dish. For optimal localization of the transducer, the transducer was moved horizontally until the amplitude of a hyperpolarization transient was maximal (see Fig. 1E for example). This procedure ensured that US-induced responses could be triggered by the lowest possible intensity. Alternatively, US was tested with an orientation perpendicular to the proximal-to-distal axis of the axon and the electrodes, also at 45° to the horizontal plane. However, the perpendicular orientation appeared to be less effective. Unless specified otherwise in the figures, US-induced responses reported here were evoked by one 5-ms US burst at 2.1 MHz. Figure 1, A and C, show electrode placements from a typical experiment. The two electrodes were inserted into the same axon, the inhibitor in most cases, at the primary and secondary branches, respectively.

Figure 1D shows the spatial profile of the focused US beam, determined with a hydrophone (0.75 MPa peak pressure with a mechanical index of 0.52) in a chamber (150 × 50 × 50 cm) filled with degassed water. The focal space is cigar shaped, 4 mm longitudinally and 1 mm in cross section diameter. A focused US beam with a circular cross section of 1 mm diameter and a 45° angle will project an elliptical focal image on the preparation with minor and major axes of 1 and 1.44 mm, respectively (Fig. 1C).

Recordings shown in this report were mainly obtained from the secondary branches; traces obtained simultaneously from the primary branch are shown for comparison (Fig. 1, C and E). In this example, the two electrodes were >500 µm apart, and APs recorded from the primary branch exhibited antidromic conducting features (Lin 2013). In most experiments, the distance between the two electrodes was ~500 µm. The US beam consistently produced hyperpolarization during the US burst (n > 40), but in some cases this hyperpolarization was obscured by subthreshold depolarization or by a train of APs that occurred in stochastic clusters (Fig. 1E; 5 and 6). The hyperpolarization could be due to a change in membrane capacitance caused by radiation pressure (Prieto et al. 2013) or a differential movement of electrolytes in saline (Debye 1933). This phenomenon is not pursued in this report.

The viability of the axon and possible damaging effect of focused US were evaluated in several control experiments. First, injections of test current were inserted between US trials in some preparations. AP amplitude and Rin remained stable between and after clusters of US-induced depolarization. In the example shown in Fig. 2A, US tone bursts were delivered at 0.1 Hz, and the depolarization occurred stochastically over the course of 75 min (Fig. 2A1). A suprathreshold current step, injected between US bursts, evoked stable AP amplitude except during US-induced depolarization, which was associated with a decrease in membrane resistance (Fig. 2A1). Representative traces of US-induced depolarizations and AP trains, marked in Fig. 2A1, are displayed in Fig. 2, A2 and A3, respectively. Second, the axoplasm was inspected visually, under a ×60 water immersion lens, at the end of some experiments. Most US-responsive preparations retained a smooth and healthy consistency. Damaged axons typically exhibited reduced Rin and vacuole-like structures that have been identified as a morphological marker for injury in axons (Eddleman et al. 2000). Third, the opener preparation can be dissected such that the proximal part of the motor axons can be preserved for up to 10 mm in length. Control experiments showed that a US beam focused on the proximal end of the axons can still trigger a US-induced response. Figure 2B shows the depolarizations evoked by US tone bursts after horizontal displacement of the US focal area to the proximal part of the axon by 3 mm or 9 mm from the primary branching point where electrode insertion points were located. Since the projected US focal area was roughly 1 × 1.44 mm (Fig. 1C), a 9-mm displacement would result in a reduction in US intensity by at least 10-fold (Fig. 1D) at the electrode insertion point. In fact, a 10-fold reduction in US intensity from the threshold value of the US-induced depolarization was never able to induce any response when the focal point remained at the electrode insertion point. Thus the detection of depolarization in Fig. 2B suggests that it was due to interaction between the US pressure wave and the axonal membrane. Finally, extracellular loose-patch recording was used to monitor US-induced responses as an alternative approach for evaluating the possibility that US-induced damage at the electrode penetration site was the cause of the depolarization. Traces in Fig. 2C include two trials that exhibited a clear upward deflection at the onset of the US burst; also included for comparison are trials in which US failed to trigger depolarization and induced only hyperpolarization. The occurrence of US-induced response detected extracellularly was less frequent than those recorded with intracellular electrodes. However, since US-induced depolarizations exhibited relatively slow rising phases (see Fig. 4D), the extracellular recording technique, although ideal for detecting fast transients such as APs, is not expected to detect smaller US-induced events with a slower rising phase. These control experiments suggest that the US-induced depolarization was unlikely to be due to damage or direct US-microelectrode interaction at the recording sites.

US Transducer

The active element of the transducer was a 2.1-MHz spherical piezo cup from STEMINC (Steiner & Martins). The cup had a diameter of 20 mm and a spherical radius of 30 mm, which was also the focal length of the conical US beam from the cup (Fig. 1B).

Rexolite, a cross-linked polystyrene with low US absorption (impedance = 2.48 MRayl) and a low reflection coefficient from soft tissues, was machined into a conical shape with the large end fitting exactly to the inside of the cup (Fig. 1B). The cone and the piezo cup were glued with epoxy. The angle and length of the cone were fashioned into the shape of the US beam, with the focal point at the tip of the cone. The tip was machined down to a concave sphere with a ball-shaped milling tool. The radius of the sphere, 6.35 mm, was less than the focal length of the transducer cup. When submerged in water, the Rexolite-to-water surface formed a lens that pulled the original focal point closer to the transducer. This made the focal spot smaller. The tip was submerged in saline during the experiment.

Taking into account the US burst frequency (2.1 MHz), US pressure at the focal area (typically <0.75 MPa), Rexolite impedance, and duty cycle (5 ms burst/10 s), the intensity of the spatial peak temporal average (ISPTA) of US at the focal point should be 9.4 mW/cm2, whereas the FDA safety limit ranges from 17 to 720 mW/cm2 depending on application (Miller 2008).

Data Analysis

Statistical results were presented as averages and standard deviation or standard error (SE) as specified. Statistical significances were determined with the Mann-Whitney test when sample sizes to be compared were different and with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test when data sets were paired.

RESULTS

Figure 1E shows representative examples of axonal responses to a US tone burst. As an illustration of the stochastic nature of US-induced responses, the same US tone burst in three consecutive trials induced no response or depolarization, with or without AP firing. The recordings were obtained in pairs, i.e., simultaneously from the primary and secondary branches (Fig. 1C). The stochastic and clustering nature of the US-induced responses is better illustrated by the timeline plot of US-induced responses in Fig. 2A1 from a different preparation.

VGCs appeared to play a minimal role in US-induced depolarization, since it was still detectable after the main VGCs in this preparation were blocked. Specifically, 1 µM TTX, which blocks sodium channels, 200 µM 4-AP, which blocks the dominant low-threshold potassium channels, and 50 µM ZD7288, which blocks hyperpolarization-activated cation channels, were used to block the main VGCs previously described in the axons (Beaumont and Zucker 2000; Lin 2008, 2012, 2013, 2016). Calcium channels were not blocked because they had been shown to localize in terminal varicosities and to contribute minimally to AP waveform recorded in the axon (Delaney et al. 1991; Wojtowicz and Atwood 1984). In the presence of these blockers, 5-ms US bursts produced depolarization with the characteristic waveform shown in Fig. 3, displayed in two different timescales in Fig. 3, A and B. All traces were recorded from the same axon but from two different clusters of US-induced responses. The two clusters were recorded 90 min apart. In general, there was no chronological trend in the amplitude of US-induced responses. In most trials, the initial depolarization occurred almost immediately after the onset of the US burst and rapidly reached a peak. In 22 of 43 US-induced responses, an additional depolarization occurred at the termination of the US burst (Fig. 3B). The decay in Vm occurred in three stages, the initial fast decline leading to a plateau that was followed by a rapid return to the resting Vm. Because of this multicomponent feature of the falling phase, we measured the duration of depolarization at 25% of peak amplitude (Fig. 3A). In this preparation, the duration varied over a wide range, from 20 ms to 7.8 s.

Basic electrophysiological parameters of US-induced depolarization compiled from 11 animals are summarized in Fig. 4: peak amplitude (Fig. 4A), duration at 25% peak amplitude (Fig. 4B), delay of maximum rate of potential rise (dV/dt) (Fig. 4C), and maximal dV/dt (Fig. 4D). The amplitude of the depolarization from the entire data set ranged from 2 to 60 mV, with a mean of 10.1 ± 2.09 mV (SE). [To avoid biases due to preparations with large sample sizes, mean amplitudes calculated from individual preparations were averaged. The total number of events (total) collected from the 11 animals was used to compile the histograms.] Duration measured at 25% of peak amplitude had a mean of 2.13 ± 0.87 s, with most of the durations shorter than 300 ms. The averaged duration represents an underestimate because some depolarizations persisted longer than the lengths of sampled traces, 2–20 s, and these durations could not be measured. The sample size of the duration was smaller than the other parameters for the same reason. The latency of the depolarization was determined from the onset of the US burst to the maximum of the time derivative (dVm/dt) of Vm. The onset latency (delay in Fig. 4C) was as short as 0.3 ms, with a mean of 3.35 ± 0.53 ms. The delay histogram shows that the majority of depolarizations reached their maximum dVm/dt before the US burst was terminated. The spread of the delays over the 5-ms duration suggests that depolarization was initiated after variable cycles of the 2.1-MHz US train. There is a distinct peak that corresponds to the ending of US bursts at 5 ms, suggesting that the offset of the US could also trigger depolarization. The origin of the second delayed peak remains unclear; it could be due to the return of the hyperpolarization or due to radiation pressure-induced membrane deformation and capacitance change (Prieto et al. 2013). The averaged dVm/dt maximum was 3.33 ± 1.25 V/s. For comparison, this maximal dVm/dt value is ~30 times slower than that of APs recorded in the presence of 4-AP (Lin 2012).

We have found that the Rin of the axonal membrane decreased when the US produced a subthreshold depolarization or APs. Figure 5 shows such an example. In the control trace, the axon was hyperpolarized by a −5-nA current step (100 ms). After a 100-ms interval, the Rin of the axon was tested with a −20-nA step (100 ms). In this axon, the second step produced a 35-mV hyperpolarization, indicating that Rin = 1.75 MΩ. When a 10-ms US burst triggered a train of APs, the second (−20 nA) step suppressed the spikes and slightly hyperpolarized the cell. The hyperpolarization was 4 mV, measured from the first trough after the test current step, which is equivalent to a Rin of ~0.2 MΩ. The spike train resumed after the test step was terminated.

We next examined whether this depolarization, and the associated decrease in Rin, was due to voltage-gated inward currents. A representative example is shown in Fig. 6, where a preparation treated with TTX (1 µM) and Cd2+ (200 µM) was probed with the same current injection protocol as that in Fig. 5. When US induced only hyperpolarization (Fig. 6A), the time constant and Rin of the axon remained unchanged, as indicated by the complete overlap between the US and no-US traces. However, when a US burst of the same intensity produced a small depolarization, the test current showed a decrease in Rin (Fig. 6B). The relationship between US-induced depolarization and the decrease in Rin was best visualized by subtracting the control trace (no US) from the test trace (US) (Fig. 6, A and B). Four such “difference traces” are shown in Fig. 6C. A trial that showed no US-induced depolarization exhibited no change in Rin, i.e., a flat trajectory, during the second test pulse. In three additional trials, the amplitudes of US-induced depolarizations correlated with the magnitude of reduction in Rin. Similar observations, with the same current injection protocol, were observed in six preparations.

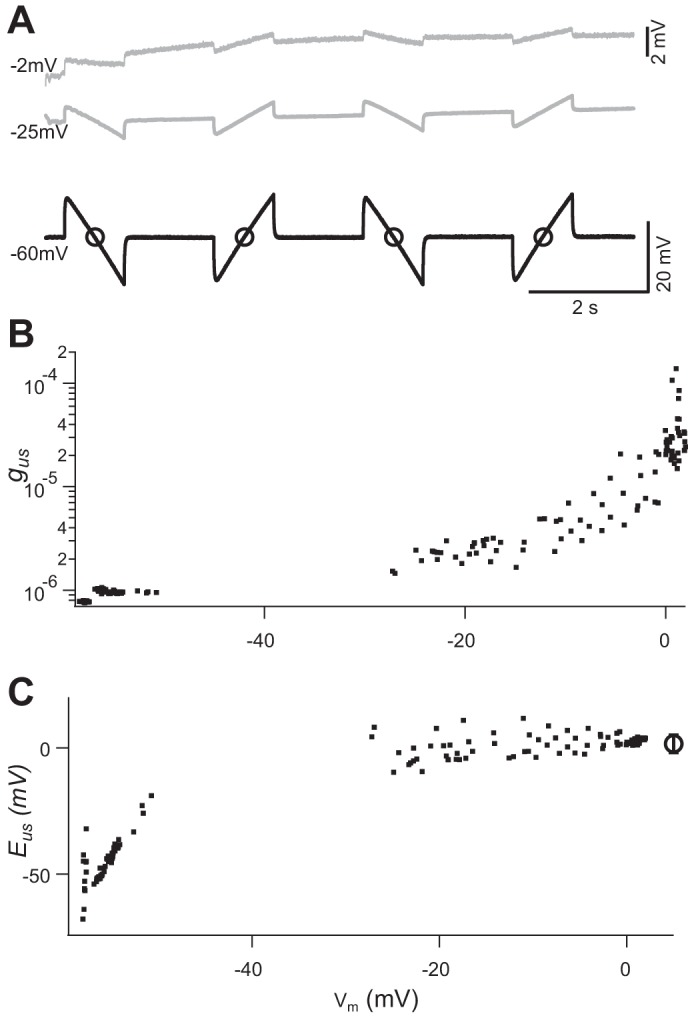

Next, we characterized the properties of this increase in membrane conductance (gm). A ramp protocol was used to estimate the reversal potential (Eus) and membrane conductance (gus) underlying US-induced depolarization. In some preparations, US-induced responses were sufficiently large and long-lasting that it was possible to measure gm and to estimate Eus and gus over a broad voltage range. Figure 7A shows three traces recorded from an inhibitor. During each trace, four current ramps with 10 nA peak-to-peak amplitude but alternating slopes were applied. The top two traces in Fig. 7A were recorded during a prolonged US-induced depolarization, whereas the bottom trace was recorded when the same US tone burst did not trigger depolarization. We assumed that the major components of VGCs had been blocked by TTX (1 µM), 4-AP (200 µM), and ZD7288 (50 µM) (Beaumont and Zucker 2000; Lin 2012, 2013). The remaining dominant conductance in the presence of these blockers would then be 1) membrane leak conductance (gl) with a reversal potential at resting Vm (El) and 2) US-induced conductance (gus) with a reversal potential (Eus). Given the prolonged nature of US-induced depolarization in this analysis, ~240 s, we assumed that at each time point of Vm and gm measurement the net current was zero. Therefore

| (1) |

substituting gus = gm − gl

Fig. 7.

Estimate of reversal potential and conductance changes induced by ultrasound (US). A: recordings obtained during a prolonged (240 s) episode of US-induced depolarization. Four current ramps were delivered during each 10-s trace. Black trace was recorded from a trial in which US burst induced no depolarization. Two gray traces were recorded during different stages of recovery from a large US-induced depolarization. Circles on black trace identify the time point when membrane potential (Vm) and membrane conductance were measured. Vm at which the traces were recorded is indicated on left of each trace. Top trace was amplified by a factor of 4 (see calibration on right), to highlight the responses induced by current ramps. B and C: US-induced conductance (gus; B) and reversal potential (Eus; C) calculated from Eqs. 1 and 2 and plotted against Vm. Circle and error bar on right in C represent the mean and SD of the Eus values estimated when Vm was above −30 mV. All recordings were obtained in the presence of tetrodotoxin (1 µM), 4-aminopyridine (200 µM), and ZD7288 (50 µM). Intensity of spatial peak temporal average = 7.0 mW/cm2

| (2) |

Vm and gm were measured at the midpoint of each ramp, where the injected current was zero (Fig. 7A). Consistent values of Eus were obtained while Vm was in the range of −30 to 0 mV (Fig. 7C). The value of Eus, based on eight episodes of large US response from five animals, had a mean value of −8.4 ± 2.3 mV (SE), which suggests that a nonselective permeability underlies this conductance. gus and gl values estimated from the same data set were 38 ± 23 µS and 0.68 ± 0.19 µS, respectively. These values of gus were 10–100 times larger than gl and are correlated with Vm (Fig. 7B). There were no data in the voltage range between −30 and −60 mV because Vm returned to resting level rapidly, during 10-s gaps of data acquisition, after the plateau phase of depolarization.

DISCUSSION

To gain a better understanding of mechanisms of US-mediated neuromodulation, we studied the biophysical effects of focused US on single motor axons of the crayfish opener neuromuscular junction (Lin 2008, 2012, 2013, 2016). We found two novel phenomena produced by a focused US tone burst in this preparation. First, the US burst consistently generated a hyperpolarization that could be followed or superseded by a depolarization or a train of APs. The depolarization persisted in the presence of blockers of main VGCs in this preparation. With VGCs blocked, depolarization had a characteristic waveform consisting of a steep rising phase followed by a fast decay to a plateau and finally a relatively rapid return to resting Vm. The onset of depolarization was nearly instantaneous, occurring in <1 ms in some instances, with a mean latency of ~3 ms. Duration was highly variable, lasting as short as 20 ms and as long as 200 s. Second, membrane conductance increased when and only when the US beam produced depolarization. The reversal potential of US-induced conductance (Eus) averaged −8 mV, suggesting a nonselective conductance. The value of Eus could be an underestimate, because spatial decay along the axon has not been taken into account. The maximum value of gus is 10–100 times larger than gl. Thus the opening of this conductance could significantly affect the activities of an axon.

Comparison with Previous Studies

There has been a long history of investigation of US effects on peripheral axons from vertebrate and, to a lesser extent, invertebrate preparations. Most studies reported inhibition in amplitude or conduction velocity of compound APs in sciatic nerve preparations (Colucci et al. 2009; Tsui et al. 2005; Young and Henneman 1961). It is important to point out a fundamental difference in experimental approaches used in the present study and those monitoring compound APs of peripheral nerves. We examined intracellular events induced by US that took off from resting Vm. Many of these depolarizations were relatively prolonged—the averaged duration at 25% peak amplitude was ~2 s—and subthreshold. Both characteristics would be difficult to detect with AC amplifiers used in compound AP recordings. Furthermore, AP generation is typically optimized in that it is an all-or-none, explosive process, with a safety factor of 5 or higher (Bostock and Grafe 1985). As a result, there is little headroom for detecting enhancement or excitatory effects unless a graded stimulation protocol is used. Therefore, it would be extremely difficult to infer the existence of depolarizations reported here from compound AP recordings.

We suggest that there is no fundamental inconsistency between our observation and those from compound AP measurements. Prolonged depolarization can inactivate Na+ channels, contribute to a depolarization block, and reduce compound AP amplitude. The stochastic nature of our observation means that such a block may occur in a subset of axons and give rise to a reduced compound AP amplitude. Although studies using complex systems, such as whole animals or brain slices, have mainly shown excitatory effect of US stimulation, the complexity of these systems does not inform the effect of US at the cellular level (King et al. 2013; Menz et al. 2013; Tufail et al. 2010; Tyler et al. 2008). In summary, we suggest that US-induced depolarization, although it may initially be excitatory, could potentially inactivate Na+ channels and explain the inhibitory effects reported in previous studies.

Mechanisms Underlying Increase in Membrane Conductance Due to Ultrasound

Here we consider two possible mechanisms that may be responsible for the transient increase of the membrane conductance gus specifically produced by US.

US modulation of protein ion channels.

It has been suggested that US modulation of neuronal activity could be mediated by VGCs or mechanosensitive channels. A US-induced increase in membrane conductance has been reported in frog skin (1 MHz), although the identity of underlying ion channels in the study was not pursued (Dinno et al. 1989). US at 10 MHz has been shown to positively modulate TREK K+ channels and Nav1.5 expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Kubanek et al. 2016). Blockers selective for these channels abolish US-induced effects. Microbubble-amplified US (2.25 MHz) stimuli have been shown to modulate Caenorhabditis elegans behavior, and this modulation correlated with TRP-4 expression levels (Ibsen et al. 2015).

We examined the possibility that the depolarization reported here involves voltage-gated Na+, Ca2+, or HCN channels by applying specific blockers of these channels. Since TTX at 10 nM completely blocks APs in crayfish opener (Lin 2013; Wojtowicz and Atwood 1984), a possible role for Nav1.5, the only known Na+ channel that exhibits US sensitivity, can be ruled out because this channel is TTX insensitive (Goldin 2001). The existence of TREK-like K+ channels in the crayfish axon is unknown. The crayfish stretch receptor preparation is one of the classical model systems for the study of mechanotransduction (Rydqvist et al. 2007), but the molecular identity of the stretch-activated channels in this animal is not known. It is also not known whether mechanosensitive channels are present in the opener motor axons. The observation that depolarization outlasted the US tone burst by tens of seconds could be interpreted as evidence against a role of mechanosensitive channels in US-induced depolarization. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that US, with its unique mechanical impacts, could cause long-lasting open states of mechanosensitive channels.

It has been shown that US can induce biological effects by raising tissue temperature (Colucci et al. 2009). In the case of neuronal tissues, temperature-sensitive TRP channels could potentially play a role in US-induced modulation if US significantly increases tissue temperature. However, the stochastic nature of US-induced depolarization reported here suggests that temperature is unlikely to be the trigger, because in our recording system temperature rise in bulk saline caused by energy injection, such as with an infrared laser, is invariant from trial to trial. Finally, a thermocouple probe with millisecond and subcentigrade resolutions uncovered no detectable change in temperature when placed in the focal area of the US transducer used in this study.

US modulation of lipid bilayers.

Simulation studies of electroporation of lipid bilayers have suggested that the phospholipids in each leaflet of a bilayer are constantly moving laterally at a speed on the order of 1 ns (Böckmann et al. 2008). When a strong electric field (>300 mV/5 nm) is applied across the membrane, it can produce hydrophobic nanopores of ~0.5 nm and hydrophilic nanopores of larger diameter within nanoseconds. A similar phenomenon may occur when US is applied to the membrane, since it can alter the lateral surface tension (Griesbauer et al. 2009; Plaksin et al. 2016) and potentially open nanopores.

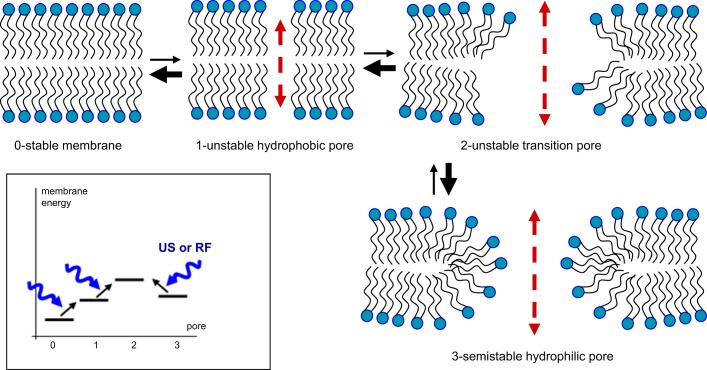

Figure 8 illustrates the possible roles of these nanopores in generating the gus (Krasovitski et al. 2011). A simulation study by Böckmann et al. (2008) has shown that an electric field of 300–1,000 mV across the lipid bilayer can produce two types of nanopores: hydrophobic nanopores of ~0.5 nm in diameter (state 1) and hydrophilic nanopores (state 3). On the basis pf this study, we hypothesize that a brief burst of US opens the gus through the following process: 1) The lipid bilayer making up the cell membrane is normally in a stable state (state 0). 2) When the lateral surface tension is perturbed by an electric field or a US pressure wave, the membrane moves to an unstable state (state 1) containing hydrophobic nanopores. 3) Continuous bombardment of the membrane with a burst of US pressure waves leads to a very unstable transition state (state 2) with the nanopores in an intermediate state between hydrophobic and hydrophilic configurations. 4) This unstable state can move back to state 1 or move to the state with hydrophilic nanopores (state 3). The delay time for individual nanopores to open can be very fast (<10 ns), but it is not known how long they stay open or how they collectively contribute to the increase in membrane conductance (Böckmann et al. 2008). We speculate that the open state may last much longer for the hydrophilic nanopores than their hydrophobic counterparts because of their geometry (Tieleman et al. 2003). Specifically, hydrophilic nanopores represent a relative energy minimum with lipid polar heads facing polar charges from ions and water dipoles and hydrophobic lipid tails maintaining contact with each other. The return from state 3 to state 0 requires some energy, either external or thermal energy, to overcome the energy barrier of state 2. The energy barrier appears to be low enough for the transition back to state 0 without external energy, since the repolarization was mostly seen after the cessation of a US burst.

Fig. 8.

Hypothetical lipid membrane pore configurations and transitions that might explain the observed variability in the duration of ultrasound (US)-induced conductance (gus). US or other forces, e.g., radio frequency (RF) electric fields, increases the probability of lateral movement in lipids and the formation of unstable hydrophobic pores (1), and from there to wider transition pores (2). These unstable transition pores would in turn have a high transition rate (heavy arrow) toward formation of semistable hydrophilic pores (3) that could mediate long-lasting gus activation. Rapid gus closing could result from high transition rates from 2 to 1, and 1 to 0, whereas transition from the semistable state 3 to 1 would be impeded by the higher energy of the transition pore state (2). Inset: hypothesized membrane energy levels for each state and US- or RF-facilitated transitions (lipid channels 1 and 3 inspired by Fig. 1 of Böckmann et al. 2008 and Fig. 4 of Krasovitski et al. 2011).

This hypothesis could explain the pharmacology and kinetics of the membrane depolarization characterized here. VGC blockers used in this study interact with specific binding sites of their target channels and would not be expected to block lipid nanopores. Since the depolarization could occur with a minimal delay of 0.3 ms, during which ~600 cycles of US pressure waves were delivered at 2.1 MHz, a continuous injection of external energy is presumably needed to move the membrane from state 0 to state 3. The time for the return of Vm after US burst was variable, lasting as little as 10–100 ms and as long as 200 s. We believe this variability is due to the stability of hydrophilic nanopores in state 3 and the difficulty of moving from this state to state 0 via the energy barrier at state 2 (Fig. 8, inset). According to our hypothesis, a burst of US pressure waves would produce a variable number of hydrophilic nanopores, with this number being very large in some cases such that it can generate a depolarization of up to 60 mV.

Our hypothesis leads to testable predictions. For example, it predicts that the probability of a pore opening, and consequent membrane depolarization, should increase when the lateral surface tension of the membrane is modified under steady-state conditions, such as by changing the osmotic pressure or temperature of the bathing medium. These manipulations would lead to changes in the duration of membrane depolarization in a predictable manner based on known effects of these physical processes on membrane stability. We will test these and other predictions in the near future.

Significance and Future Directions

We found in a single-axon preparation that a burst of US pressure waves can produce a membrane depolarization. This depolarization could trigger an AP train that was sometimes followed by a period of inhibition attributable to depolarization block. Moreover, this depolarization is associated with a US-mediated conductance increase that may correspond to “lipid ion channels” (Heimburg 2010). US is known to affect biological membranes in other ways including modulation of mechanosensitive receptors, voltage-gated ion channels, or membrane capacitance (Ibsen et al. 2015; Kubanek et al. 2016, 2018; Prieto et al. 2013). Given the complex mixture of ion channels and lipid molecules in neurons and glial cells, as well as their complex cellular morphology, the effect of US on neuronal tissues is expected to be multifaceted and remains to be further explored. Detailed understanding of the biophysical bases of US-based neuromodulation will be necessary for effectively and optimally applying US to in vivo animal studies and humans.

GRANTS

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R24 MH-109111; lead principal investigator: Y. Okada) and a grant from the National Science Foundation (1707865; principal investigator: Y. Okada).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.O. conceived and designed research; J.-W.L., F.Y., and W.S.M. performed experiments; J.-W.L., F.Y., and W.S.M. analyzed data; J.-W.L., F.Y., W.S.M., and Y.O. interpreted results of experiments; F.Y. prepared figures; J.-W.L. and Y.O. drafted manuscript; J.-W.L., W.S.M., G.E., and Y.O. edited and revised manuscript; J.-W.L., F.Y., W.S.M., G.E., and Y.O. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jason White, Casey McDermott, and Kush Tripathi for help on US transducer calibration. We thank Nicky Schweitzer for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Aubry JF, Tanter M, Pernot M, Thomas JL, Fink M. Experimental demonstration of noninvasive transskull adaptive focusing based on prior computed tomography scans. J Acoust Soc Am 113: 84–93, 2003. doi: 10.1121/1.1529663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont V, Zucker RS. Enhancement of synaptic transmission by cyclic AMP modulation of presynaptic Ih channels. Nat Neurosci 3: 133–141, 2000. doi: 10.1038/72072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böckmann RA, de Groot BL, Kakorin S, Neumann E, Grubmüller H. Kinetics, statistics, and energetics of lipid membrane electroporation studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J 95: 1837–1850, 2008. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock H, Grafe P. Activity-dependent excitability changes in normal and demyelinated rat spinal root axons. J Physiol 365: 239–257, 1985. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, Hynynen K. A non-invasive method for focusing ultrasound through the human skull. Phys Med Biol 47: 1219–1236, 2002. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/8/301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci V, Strichartz G, Jolesz F, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K. Focused ultrasound effects on nerve action potential in vitro. Ultrasound Med Biol 35: 1737–1747, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debye P. A method for the determination of the mass of electrolytic ions. J Chem Phys 1: 13–16, 1933. doi: 10.1063/1.1749213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney K, Tank DW, Zucker RS. Presynaptic calcium and serotonin-mediated enhancement of transmitter release at crayfish neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci 11: 2631–2643, 1991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02631.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinno MA, Crum LA, Wu J. The effect of therapeutic ultrasound on electrophysiological parameters of frog skin. Ultrasound Med Biol 15: 461–470, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(89)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleman CS, Bittner GD, Fishman HM. Barrier permeability at cut axonal ends progressively decreases until an ionic seal is formed. Biophys J 79: 1883–1890, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76438-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias WJ, Huss D, Voss T, Loomba J, Khaled M, Zadicario E, Frysinger RC, Sperling SA, Wylie S, Monteith SJ, Druzgal J, Shah BB, Harrison M, Wintermark M. A pilot study of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor. N Engl J Med 369: 640–648, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry FJ, Ades HW, Fry WJ. Production of reversible changes in the central nervous system by ultrasound. Science 127: 83–84, 1958. doi: 10.1126/science.127.3289.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin AL. Resurgence of sodium channel research. Annu Rev Physiol 63: 871–894, 2001. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesbauer J, Wixforth A, Schneider MF. Wave propagation in lipid monolayers. Biophys J 97: 2710–2716, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Hamilton M 2nd, Offutt SJ, Gloeckner CD, Li T, Kim Y, Legon W, Alford JK, Lim HH. Ultrasound produces extensive brain activation via a cochlear pathway. Neuron 98: 1020–1030.e4, 2018. [Erratum in Neuron 99: 866, 2018.] doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimburg T. Lipid ion channels. Biophys Chem 150: 2–22, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, McDannold N, Sheikov NA, Jolesz FA, Vykhodtseva N. Local and reversible blood-brain barrier disruption by noninvasive focused ultrasound at frequencies suitable for trans-skull sonications. Neuroimage 24: 12–20, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibsen S, Tong A, Schutt C, Esener S, Chalasani SH. Sonogenetics is a non-invasive approach to activating neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun 6: 8264, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RL, Brown JR, Newsome WT, Pauly KB. Effective parameters for ultrasound-induced in vivo neurostimulation. Ultrasound Med Biol 39: 312–331, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasovitski B, Frenkel V, Shoham S, Kimmel E. Intramembrane cavitation as a unifying mechanism for ultrasound-induced bioeffects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 3258–3263, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015771108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubanek J, Shi J, Marsh J, Chen D, Deng C, Cui J. Ultrasound modulates ion channel currents. Sci Rep 6: 24170, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep24170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubanek J, Shukla P, Das A, Baccus SA, Goodman MB. Ultrasound elicits behavioral responses through mechanical effects on neurons and ion channels in a simple nervous system. J Neurosci 38: 3081–3091, 2018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1458-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JW. Electrophysiological events recorded at presynaptic terminals of the crayfish neuromuscular junction with a voltage indicator. J Physiol 586: 4935–4950, 2008. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.158089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JW. Spatial variation in membrane excitability modulated by 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels in the axons of the crayfish neuromuscular junction. J Neurophysiol 107: 2692–2702, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00857.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JW. Spatial gradient in TTX sensitivity of axons at the crayfish opener neuromuscular junction. J Neurophysiol 109: 162–170, 2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.00463.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JW. Na+ current in presynaptic terminals of the crayfish opener cannot initiate action potentials. J Neurophysiol 115: 617–621, 2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.00959.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Clement GT, Black P, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Transcranial magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound surgery of brain tumors: initial findings in 3 patients. Neurosurgery 66: 323–332, 2010. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000360379.95800.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menz MD, Oralkan O, Khuri-Yakub PT, Baccus SA. Precise neural stimulation in the retina using focused ultrasound. J Neurosci 33: 4550–4560, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3521-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihran RT, Barnes FS, Wachtel H. Temporally-specific modification of myelinated axon excitability in vitro following a single ultrasound pulse. Ultrasound Med Biol 16: 297–309, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(90)90008-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DL. Safety assurance in obstetrical ultrasound. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 29: 156–164, 2008. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaksin M, Kimmel E, Shoham S. Cell-type-selective effects of intramembrane cavitation as a unifying theoretical framework for ultrasonic neuromodulation. eNeuro 3: ENEURO.0136-15.2016, 2016. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0136-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto ML, Oralkan Ö, Khuri-Yakub BT, Maduke MC. Dynamic response of model lipid membranes to ultrasonic radiation force. PLoS One 8: e77115, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydqvist B, Lin JH, Sand P, Swerup C. Mechanotransduction and the crayfish stretch receptor. Physiol Behav 92: 21–28, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Shapiro MG, Tsao DY. Ultrasonic neuromodulation causes widespread cortical activation via an indirect auditory mechanism. Neuron 98: 1031–1041.e5, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Hynynen K. The potential of transskull ultrasound therapy and surgery using the maximum available skull surface area. J Acoust Soc Am 105: 2519–2527, 1999. doi: 10.1121/1.426863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieleman DP, Leontiadou H, Mark AE, Marrink SJ. Simulation of pore formation in lipid bilayers by mechanical stress and electric fields. J Am Chem Soc 125: 6382–6383, 2003. doi: 10.1021/ja029504i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui PH, Wang SH, Huang CC. In vitro effects of ultrasound with different energies on the conduction properties of neural tissue. Ultrasonics 43: 560–565, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufail Y, Matyushov A, Baldwin N, Tauchmann ML, Georges J, Yoshihiro A, Tillery SI, Tyler WJ. Transcranial pulsed ultrasound stimulates intact brain circuits. Neuron 66: 681–694, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufail Y, Yoshihiro A, Pati S, Li MM, Tyler WJ. Ultrasonic neuromodulation by brain stimulation with transcranial ultrasound. Nat Protoc 6: 1453–1470, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler WJ, Tufail Y, Finsterwald M, Tauchmann ML, Olson EJ, Majestic C. Remote excitation of neuronal circuits using low-intensity, low-frequency ultrasound. PLoS One 3: e3511, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz JM, Atwood HL. Presynaptic membrane potential and transmitter release at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. J Neurophysiol 52: 99–113, 1984. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RR, Henneman E. Functional effects of focused ultrasound on mammalian nerves. Science 134: 1521–1522, 1961. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3489.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]