Abstract

The effect of work-matched exercise intensity on β-cell function is unknown in people with prediabetes before clinical weight loss. We determined if short-term moderate continuous (CONT) vs. high-intensity interval (INT) exercise increased β-cell function. Thirty-one subjects (age: 61.4 ± 2.5 yr; body mass index: 32.1 ± 1.0 kg/m2) with prediabetes [American Diabetes Association criteria, 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)] were randomized to work-matched CONT (70% HRpeak) or INT (3 min 90% HRpeak and 3 min 50% HRpeak) exercise for 60 min/day over 2 wk. A 75-g 2-h OGTT was conducted after an overnight fast, and plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and free fatty acids were determined for calculations of skeletal muscle [oral minimal model (OMM)], hepatic (homeostatic model of insulin resistance), and adipose (Adipose-IR) insulin sensitivity. β-Cell function was defined from glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS, deconvolution modeling) and the disposition index (DI). Glucagon-like polypeptide-1 [GLP-1(active)] and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) were also measured during the OGTT, along with peak oxygen consumption and body composition. CONT and INT increased skeletal muscle- but not hepatic- or adipose-derived DI (P < 0.05). Although both treatments tended to reduce fasting GLP-1(active) (P = 0.08), early phase GLP-1(active) increased post-CONT and INT training (P < 0.001). Interestingly, CONT exercise increased fasting GIP compared with decreases in INT (P = 0.02). Early and total-phase skeletal muscle DI correlated with decreased total glucose area under the curve (r = −0.52, P = 0.002 and r = −0.50, P = 0.003, respectively). Independent of intensity, short-term training increased pancreatic function adjusted to skeletal muscle in relation to improved glucose tolerance in adults with prediabetes. Exercise also uniquely affected GIP and GLP-1(active). Further work is needed to elucidate the dose-dependent mechanism(s) by which exercise impacts glycemia.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Exercise is cornerstone for reducing blood glucose, but whether high-intensity interval training is better than moderate continuous exercise is unclear in people with prediabetes before weight loss. We show that 2 wk of exercise training, independent of intensity, increased pancreatic function in relation to elevated glucagon-like polypeptide-1 secretion. Furthermore, β-cell function, but not insulin sensitivity, was also correlated with improved glucose tolerance. These data suggest that β-cell function is a strong predictor of glycemia regardless of exercise intensity.

Keywords: glucose tolerance, high-intensity interval training, insulin sensitivity, pancreatic function, type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Maintaining the capacity of β-cells to secrete adequate amounts of insulin in response to low multiorgan insulin sensitivity is paramount to preventing the progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes (6). Habitual exercise is established to reduce oral glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) and preserve pancreatic function (3, 7, 16, 20, 34). However, GSIS is influenced by the prevailing level of multiorgan insulin sensitivity. This is clinically important because the product of GSIS and insulin sensitivity (i.e., disposition index) is considered a better predictor of future diabetes development than insulin sensitivity alone (1, 27, 38). Thus, work is required to determine how to optimize β-cell function.

It is critical to determine the optimal dose at which exercise affects pancreatic function in people with prediabetes since they have lost upwards of 80% of their β-cell function (2, 13, 27, 29). While exercise confers insulin-sensitizing and cardiometabolic benefit (e.g., lower total cholesterol and/or blood pressure), few studies have specifically been designed to determine the dose of exercise required to optimize β-cell function (5, 21, 29). Prior work by some (3, 20), but not all (28), suggests that exercise volume is more important than intensity for pancreatic function in subjects at risk for type 2 diabetes despite some individuals having a blunted insulin secretion adaptation (7, 32, 35). Nonetheless, high-intensity interval exercise training (INT) improves β-cell function when adjusted to changes in skeletal muscle insulin resistance in adults with obesity (11) and type 2 diabetes (18, 26), and it may yield greater benefit than continuous (CONT) exercise (18). However, training studies to date examining the effect of INT vs. CONT exercise on insulin secretion have been confounded by significant weight/fat loss (18, 33), thereby making it difficult to determine the impact of exercise intensity per se on pancreatic function. A recent study by Heiskanen et al. compared a 2-wk sprint interval vs. moderate continuous training program in adults with prediabetes/type 2 diabetes and reported no difference between exercise intensities on enhancing pancreatic function (15). A limitation of this prior work though was that the workloads were not work matched, only early phase insulin secretion was tested, and no assessment of incretin hormones [i.e., glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like polypeptide-1 (GLP-1)] was made. Thus, there is a major knowledge gap in determining whether INT exercise enhances both early and total-phase pancreatic function to a greater extent than CONT exercise when matched on energy expenditure. This is germane in individuals with prediabetes because they have disturbances in both phases of insulin secretion (17). Based on a recent study we conducted demonstrating that 2 wk of work-matched CONT and INT exercise improved glucose tolerance comparably, but did not relate to insulin sensitivity, in people with prediabetes (12), we tested the hypothesis that INT and CONT would induce similar benefit to early and total-phase β-cell function in relation to glucose tolerance. We also hypothesized that this increase in β-cell function would relate to the incretins GIP and GLP-1 following training.

METHODS

Subjects.

These older obese subjects (age: 61.4 ± 2.5 yr; body mass index: 32.1 ± 1.0 kg/m2) were the same individuals who were previously reported in our prior randomized controlled study on glucose tolerance and metabolic flexibility (12). Subjects were recruited via flyers and/or newspaper advertisements from the local community. All subjects underwent a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to determine prediabetes status according to the American Diabetes Association, which was defined as either a fasting plasma glucose between 100 and 125 mg/dl and/or 2 h glucose between 140 and 199 mg/dl (12). Subjects were nonsmoking and sedentary (exercise <60 min/wk) and underwent medical history and physical examination that included a resting and exercise stress test with 12-lead electrocardiogram. Blood and urine chemistry analyses were also conducted to exclude people with known disease (e.g., type 2 diabetes, liver disease, cardiac dysfunction, etc.). Subjects were excluded if taking medications considered to impact glycemia (e.g., biguanides, GLP-1 agonists, etc.). All subjects provided written signed and verbal informed consent as approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board.

Body composition and aerobic fitness.

Weight was assessed on a digital scale, and height was recorded with a stadiometer to determine body mass index. Body fat, skeletal muscle mass (i.e., fat-free mass minus total body water), and visceral fat were measured by bioelectrical impedance (InBody 770 Analyzer, Cerritos, CA) (8). Subjects completed a continuous incremental peak oxygen consumption (V̇o2peak) test using a cycle ergometer with indirect calorimetry (Vmax Encore; Carefusion, Yorba Linda, CA), and heart rate (HR) peak was used to prescribe submaximal exercise.

Metabolic control.

Subjects were instructed to consume a diet containing ~250 g of carbohydrates during the 24-h period before the preintervention testing. This dietary pattern was recorded and replicated on the day before posttesting. Three-day food logs, including two weekdays and one weekend day, were used to assess ad libitum food intake before and after training (version 11.1; ESHA Research, Salem, OR). Subjects were also instructed to refrain from alcohol, caffeine, medication, and strenuous physical activity for 24 h before each study visit. Postintervention assessments were obtained ~24 h after the last training session.

Exercise training.

Subjects were randomly assigned to 12, 60 min/day work-matched bouts of CONT or INT cycle ergometry exercise over 13 days. A rest day was provided on day 7. CONT exercise was performed at a constant intensity of 70% HRpeak, whereas INT exercise involved alternating 3-min intervals at 90% HRpeak followed by 50% HRpeak. Subsequently, both interventions were designed to exercise at ~70% HRpeak. HR (Polar Electro, Woodbury, NY) and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) were monitored throughout training to ensure intensity. Exercise energy expenditure was calculated using HR-V̇o2 regression analysis with correction for O2 consumption during CONT (n = 3) and INT (n = 4) from a subset of our group as previously performed (29).

Pancreatic β-cell function.

Following an approximate 10-h fast, subjects reported to our Clinical Research Unit. Subjects rested in a semisupine position while an intravenous line was placed in the antecubital vein for blood collection. Blood samples were obtained for the determination of plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. GLP-1(active) and GIP were collected at 0, 30, and 60 min to characterize incretin responses. Fasting free fatty acid (FFA) was also obtained. Total area under the curve (AUC) during the OGTT was calculated using the trapezoidal rule as previously performed for GSIS adjustments to multiorgan insulin sensitivity by our group and others (4, 9, 29, 30). Skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity was calculated using the oral minimal model (OMM), and hepatic and adipose insulin resistance were estimated by multiplying fasting glucose and FFA by fasting insulin, respectively (30). Prehepatic insulin secretion rate (ISR) was reconstructed by deconvolution from plasma C-peptide (39). GSIS was calculated as ISR AUC divided by glucose AUC during the OGTT. The early (0–30 min) and total-phase (0–120 min) disposition index was used to calculate β-cell function relative to skeletal muscle as AUC of ISR/glucose divided by 1/OMM. β-Cell function adjusted for hepatic and adipose insulin resistance was also calculated as AUC of ISR/glucose divided by the homeostatic model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) or Adipose-IR. Hepatic insulin extraction was calculated as AUC of C-peptide divided by insulin during the OGTT.

Biochemical analysis.

Plasma glucose was analyzed by a glucose oxidase assay (YSI Instruments 2700, Yellow Springs, OH). Remaining samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 3,000 revolutions/min and stored at −80°C until later batched analyzed in duplicate to minimize variance within conditions. Insulin, C-peptide, and FFA vacutainers contained aprotonin while GLP-1(active) and GIP Vacutainers contained aprotonin and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-IV). Insulin, C-peptide, GLP-1(active) (i.e., 7–36 and 7–37 amide), and GIP were measured using an ELISA (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Plasma FFAs were determined by a colorimetric assay (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA).

Statistical analysis.

Given the relevance of fitness, body composition, glucose, FFA, and insulin to the understanding of pancreatic function, these data are reported in text for clarity (12). Data were analyzed using R (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Skewed data were log transformed for statistical analysis to meet normality. Unfortunately, because of technical difficulty, some GIP (n = 2, 1 female and 1 male) and GLP-1 (n = 1 male) data were lost within the CONT treatment. Baseline data were compared with independent two-tailed t-tests. Intervention data were compared using a two-way (group × test) or three-way (group × test × time) ANOVA, with test as the repeated measures when appropriate. Pretest total-phase GSIS as well as early and total-phase adipose disposition index and Adipose-IR were different between groups. Thus, these data were used as covariates when performing ANOVA. Pearson’s correlation was used to determine associations. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05, and data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics.

Both CONT and INT exercise reduced body weight (−0.3 ± 0.2 vs. −1.0 ± 0.2 kg, P < 0.01) and skeletal muscle mass (−0.4 ± 0.1 vs. −0.4 ± 0.1 kg, P < 0.01) (12). However, there was no difference following CONT or INT training in body fat [0.1 ± 0.1 vs. 0.3 ± 0.2 kg, P = 0.18 (12)] or visceral fat (1.1 ± 0.2 vs. 1.1 ± 1.5 cm2, P = 0.26). V̇o2peak increased following both CONT and INT (0.4 ± 0.2 vs. 0.5 ± 0.2 ml·kg−1·min−1, P < 0.05). Although submaximal HR was ~73 ± 1% and 79 ± 1% for CONT and INT, respectively (P < 0.01), subjects had similar RPE (12.8 ± 0.3 vs. 12.2 ± 0.5 arbitrary units, P = 0.23) (12) and exercise energy expenditure (388.3 ± 14.8 vs. 384.5 ± 18.8 kcal/session, P = 0.87). There were no dietary intake differences posttraining (data not shown) (12).

Glucose, FFA, and insulin metabolism.

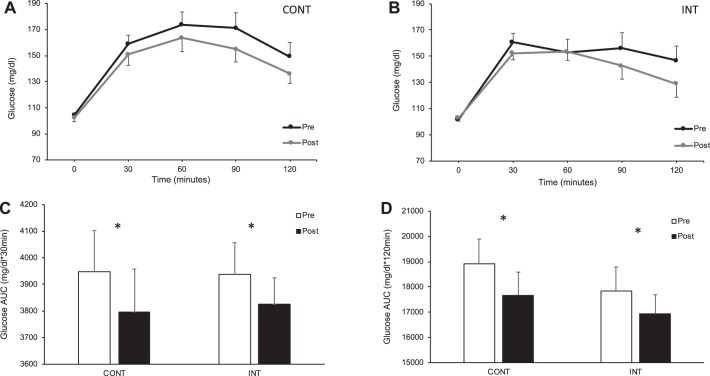

CONT and INT training had no effect on fasting (1.0 ± 1.7 vs. −2.1 ± 2.1 mg/dl, P = 0.70) or early phase glucose tolerance (Fig. 1). However, training reduced time-series glucose levels, as evident by decreased total-phase glucose AUC (P = 0.03; Fig. 1). Fasting FFA (0.03 ± 0.7 vs. 0.05 ± 0.04 meq/ml, P = 0.15) and insulin (−0.4 ± 1.5 vs. 0.1 ± 1.1 μU/ml, P = 0.89) levels were not statistically different following CONT or INT (12), although training reduced early and total-phase insulin AUC following both exercise treatments (P < 0.05, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Impact of exercise intensity on circulating glucose during the oral glucose tolerance test. CONT, continuous exercise [n = 17 subjects (13 females)]; INT, interval exercise [n = 14 subjects (11 females)]. Main effect of Test and Time (P < 0.05) was observed for circulating glucose postintervention [CONT (A) and INT (B)]. Early phase (C) and total-phase (D) glucose tolerance was calculated using total area under the curve (AUC). *Main effect of Test, P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Early and total-phase insulin secretion and incretin responses before and after training

| CONT |

INT |

ANOVA (P value) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Test | G × T | |

| Fasting | ||||||

| C-pep, ng/ml | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.17 | 0.73 |

| ISR, pM/min | 207.6 ± 19.4 | 191.9 ± 19.7 | 239.3 ± 16.9 | 232.9 ± 23.4 | 0.31 | 0.68 |

| GIP, pg/ml | 58.0 ± 10.2 | 65.4 ± 15.6 | 59.5 ± 5.3 | 46.0 ± 7.0 | 0.72 | 0.02 |

| GLP-1(active), pg/ml | 7.1 ± 2.2 | 6.7 ± 1.8 | 8.6 ± 2.9 | 7.4 ± 2.4 | 0.08 | 0.31 |

| Early phase response | ||||||

| InsulinAUC, μU·ml−1·30 min−1 | 1,449.6 ± 154.3 | 1,293.3 ± 142.1 | 1,666.2 ± 182.5 | 1,455.6 ± 206.1 | 0.01 | 0.70 |

| C-pepAUC, ng·ml−1·30 min−1 | 135.4 ± 12.6 | 126.7 ± 11.1 | 144.7 ± 10.4 | 140.6 ± 11.2 | 0.21 | 0.66 |

| ISRAUC × 10−3, pM·ml−1·30 min−1 | 17.4 ± 1.6 | 16.5 ± 1.6 | 18.8 ± 1.2 | 18.7 ± 1.5 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| GSIS, pM·min−1·mg−1·dl−1^ | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 0.88 | 0.68 |

| HIE, ng·ml−1·μU−1·ml−1·30 min−1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.60 |

| GIPAUC, pg·ml−1·30 min−1 | 5,302.2 ± 841.3 | 5,529.7 ± 824.0 | 6,222.01 ± 301.3 | 6,031.2 ± 609.4 | 0.93 | 0.49 |

| GLP-1(active)AUC, pg·ml−1·30 min−1 | 306.7 ± 75.5 | 339.9 ± 80.9 | 406.1 ± 77.7 | 443.8 ± 75.0 | <0.001 | 0.79 |

| Total-phase response | ||||||

| InsulinAUC, μU·ml−1·120 min−1 | 10,200.3 ± 1,243.6 | 9,365.7 ± 1,208.9 | 10,406.8 ± 1,266.4 | 9,288.8 ± 1,248.7 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| C-pepAUC, ng·ml−1·120 min−1 | 1,156.9 ± 95.0 | 946.7 ± 86.7 | 1,159.0 ± 88.1 | 969.7 ± 65.2 | <0.001 | 0.77 |

| ISRAUC × 10−3, pM·ml−1·120 min−1 | 91.3 ± 11.5 | 104.2 ± 10.7 | 108.4 ± 7.7 | 99.1 ± 7.0 | 0.69 | 0.13 |

| GSIS, pM·min−1·mg−1·dl−1 | 4.9 ± 2.5 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 6.2 ± 1.6^ | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| HIE, ng·ml−1·μU−1·ml−1·120 min−1 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| GIPAUC, pg·ml−1·120 min−1 | 13,797.2 ± 2,040.8 | 14,290.4 ± 1,949.7 | 16,555.4 ± 846.8 | 16,035.1 ± 1,606.7 | 0.98 | 0.46 |

| GLP-1(active)AUC, pg·ml−1·120 min−1 | 646.7 ± 156.3 | 649.3 ± 152.9 | 850.0 ± 151.9 | 801.2 ± 139.3 | 0.52 | 0.44 |

Data are expressed as means ± SE. CONT, continuous exercise {n = 17 subjects (13 females) for all outcomes except glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) [n = 15 (12 females)] and glucagon-like polypeptide-1 (GLP-1) [n = 16 (13 females)]}; INT, interval exercise [n = 14 subjects (11 females)]. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [GSIS (AUC of ISR divided by glucose)] data were log transformed for statistical analysis. G, Group; T, Test; PG, plasma glucose; C-pep, plasma C-peptide; AUC, total area under the curve; ISR, insulin secretion rate derived from deconvolution of plasma C-peptide; HIE, hepatic insulin extraction. ^Pretest group difference, P < 0.05.

Insulin sensitivity.

Skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity increased following both CONT and INT (P = 0.01, Table 2). Neither hepatic nor adipose insulin resistance was altered after the intervention.

Table 2.

Insulin sensitivity before and after exercise training

| CONT |

INT |

ANOVA (P value) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Test | G × T | |

| OMM | 0.00044 ± 0.00009 | 0.00055 ± 0.00008 | 0.00033 ± 0.00004 | 0.00051 ± 0.00008 | 0.01 | 0.50 |

| HOMA-IR | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 0.98 | 0.63 |

| Adipose-IR | 9.6 ± 1.8 | 8.6 ± 1.9 | 7.4 ± 2.1^ | 6.8 ± 1.3 | 0.53 | 0.99 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. CONT, continuous exercise [n = 17 subjects (13 females); INT, interval exercise [n = 14 subjects (11 females)]; G, Group; T, Test. The oral minimal model (OMM) was calculated from plasma glucose and insulin to measure skeletal muscle insulin resistance. The homeostatic model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as fasting plasma glucose × fasting plasma insulin (PI) and then divided by 405 to depict hepatic insulin resistance. Adipose-IR was calculated as fasting free fatty acids (FFA) × fasting PI to determine adipose insulin resistance.

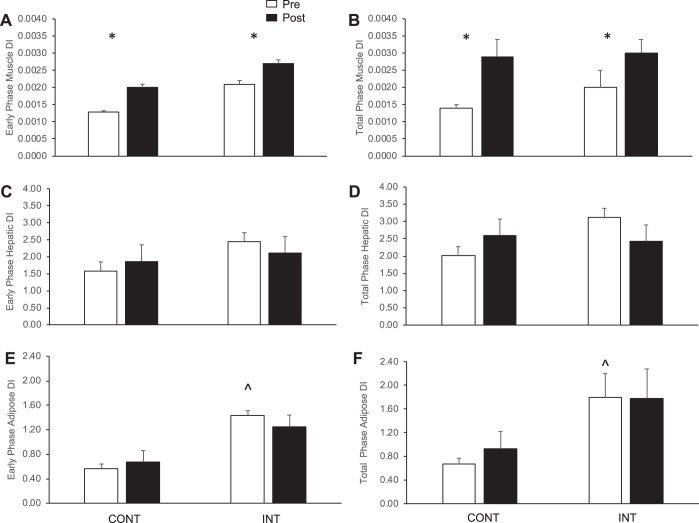

Pancreatic β-cell function.

CONT and INT training had no effect on fasting (P = 0.17) or early phase C-peptide levels, although it did lower total-phase AUC (P < 0.001, Table 1 and Fig. 1). Early and total-phase ISR were also unaltered following CONT and INT treatment. Early phase GSIS was additionally not significantly changed following either exercise intensity, although CONT training increased total-phase GSIS compared with a slight decrease after INT exercise (P = 0.02). Hepatic and adipose disposition index was not altered following CONT or INT training (Fig. 2). However, both CONT and INT exercise increased early and total-phase skeletal muscle disposition index (P < 0.05, Fig. 1). Both treatments increased early phase hepatic insulin extraction (P = 0.01), although CONT training decreased clearance during the total-phase vs. INT exercise (P = 0.07, Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Effect of exercise intensity on β-cell function adjusted for multiorgan insulin resistance. Data are expressed as means ± SE. CONT, continuous exercise [n = 17 subjects (13 females)]; INT, interval exercise [n = 14 subjects (11 females)], although 1 subject (female) was removed from CONT and INT, respectively, for hepatic and adipose disposition index (DI) since they were an outlier (>2 SD from mean). DI was used to characterize pancreatic β-cell function. Skeletal muscle DI was calculated as the area under the curve (AUC) of insulin secretion rate (ISR)/glucose divided by 1/oral minimal model (A and B). Hepatic DI was estimated as AUC of ISR/glucose divided by the homeostatic model of insulin resistance (C and D). Adipose DI was determined as the AUC of ISR/glucose divided by Adipose-IR (E and F). All β-cell function data were log transformed for statistical analysis but are shown here in raw values. *Main effect of Test, P < 0.05. ^Pretest group difference, P < 0.05.

Incretins.

Although both interventions tended to reduce fasting GLP-1(active) (P = 0.08), training raised early phase GLP-1(active) in response to the OGTT (P < 0.001, Table 1). CONT exercise increased fasting GIP compared with INT (P = 0.02), and there was no effect of training on postprandial GIP (Table 1).

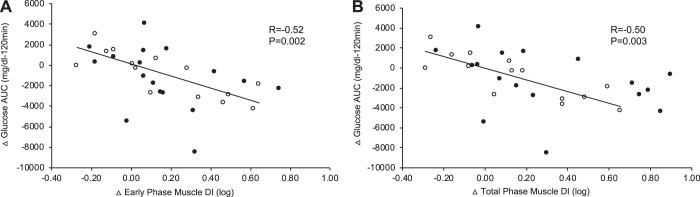

Correlational analysis.

Baseline fasting and 2-h glucose tended to correlate with changes in total-phase β-cell function (r = 0.29, P = 0.11 and r = 0.32, P = 0.07, respectively). Enhanced early and total-phase skeletal muscle disposition index was not related to weight loss (r = 0.21, P = 0.23 and r = 0.18, P = 0.32) or increases in V̇o2peak (r = −0.20, P = 0.26 and r = −0.26, P = 0.14). Reduced glucose AUC at 120 min correlated with increased early (r = −0.52, P = 0.002) and total (r = −0.50, P = 0.003)-phase skeletal muscle disposition index following short-term training (Fig. 3). There was no relation between glucose AUC at 120 min and insulin sensitivity derived from the OMM (r = −0.28, P = 0.12) or early (r = −0.20, P = 0.27) and total (r = −0.14, P = 0.42)-phase GSIS. Decreased fasting GIP correlated with lower fasting C-peptide (r = 0.41, P = 0.02) and plasma insulin (r = 0.50, P = 0.005).

Fig. 3.

β-Cell function correlates with glucose tolerance. CONT, continuous exercise [n = 17 subjects (13 females)]; INT, interval exercise [n = 14 subjects (11 females)]. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion rate (C-peptide deconvolution) area under the curve (AUC) was divided by glucose AUC during the oral glucose tolerance test. Early (0–30 min, A) and total-phase (0–120 min, B) β-cell function, or disposition index (DI), relative to skeletal muscle was calculated as AUC of insulin secretion rate/glucose divided by 1/oral minimal model. ●, CONT; ○, INT.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that short-term exercise training increases β-cell function adjusted for skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in adults with prediabetes, independent of intensity. Furthermore, only CONT exercise raised fasting GIP, whereas both CONT and INT increased early phase GLP-1 during the OGTT. The increase in pancreatic function is clinically important, since it was directly related to improved glucose tolerance. Together, these data suggest that exercise promotes unique compensatory mechanisms between skeletal muscle, gut, and pancreas to reduce ambient glucose concentrations. Although our data confirm the use of high-intensity INT exercise to improve glucose regulation (18, 32), the present data do not support prior work (5, 29, 34) suggesting greater intensities of exercise training enhance β-cell function above that of lower exercise doses in overweight people. In fact, our findings not only support moderate-intensity exercise as an effective program to increase GSIS and induce pancreatic function (34), but also we confirm recent work in adults with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes that 2 wk of sprint interval or continuous moderate-intensity exercise induced similar beneficial effects on pancreatic function (21). However, this prior research was not work matched between intensities, nor was insulin secretion measured in the early and total phase adjusted for different indexes of insulin sensitivity to elucidate how multiple organs may impact glucose disposal. Herein we expand on this prior work and show that, when high-intensity INT exercise is calorically matched to moderate CONT training, there is a similar rise in early and total-phase pancreatic function when adjusted to skeletal muscle, but not hepatic or adipose, insulin sensitivity. This is physiologically relevant, since the inverse of GSIS and tissue-specific insulin sensitivity provides an integrated view for whole body glucose disposal (4, 9, 16, 30).

Prior work by our group demonstrated that β-cell function was a stronger predictor of glycemic control benefit following CONT exercise training than insulin sensitivity (35). We confirm these findings in the present study, and expand upon our recent exercise intensity work (12), by showing that the capacity to secrete insulin following CONT or INT exercise training may be more important for glycemic regulation than insulin sensitivity. Importantly, although associations do not equal causation, improved glucose tolerance was correlated with increased early and total-phase β-cell function. This is consistent with recent work we published showing that INT exercise adds to the benefit of caloric restriction on glucose tolerance in obese adults through a pancreatic function-skeletal muscle mechanism (11). To that extent, it is recognized that the disposition index is the product of GSIS and insulin sensitivity. If one of these outcomes related to glucose tolerance, it may confound the ability to confirm that β-cell function is independently driving glycemic control. Interestingly, GSIS nor insulin sensitivity correlated with improved glucose tolerance in this report, thereby highlighting that it is the coordinated capacity to secrete insulin relative to the level of insulin sensitivity that is critical for glucose control. Indeed, recent work has postulated that functional high-intensity exercise training (32) or high-intensity INT exercise (33), but not moderate-intensity exercise with weight lifting (41), increases the efficiency by which insulin is synthesized in people with type 2 diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome. We did not design the current study to test the mechanism by which exercise increases pancreatic function per se, but the present data do support that in as little as 2 wk training increases the ability of the pancreas to release the readily available pool of insulin (i.e., early phase) and synthesize insulin in response to ambient glucose (i.e., total phase) in people with prediabetes. Moreover, we note no change in hepatic and/or adipose disposition index. This is in contrast to prior work by our group showing that a single bout of high-intensity exercise reduces GSIS when adjusted to hepatic and adipose insulin resistance to support glucose control in the immediate postexercise period (30). Subjects in the current study, however, were studied ~24 h following the last exercise bout to minimize effects of the residual exercise bout. As such, our findings suggest that tissues involved in insulin-mediated glucose regulation play distinct roles to maintain glucose homeostasis over time.

GLP-1 and GIP are collectively referred to as incretins and regulate nearly 60% of postprandial insulin secretion (42). Few exercise training studies have examined gut incretin responses, and none have tested the effect of intensity in people with prediabetes before clinically meaningful weight loss. Interestingly, prior work using CONT exercise and diet-induced weight loss reports increased pancreatic function in relation to GIP in older obese adults with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes (19, 36). This is consistent with a recent 7-day CONT high-intensity exercise intervention in obese adults resulting in reduced fasting GLP-1(active) and increased early phase GLP-1(active) in response to an OGTT (23). We report herein that fasting GLP-1(active) tended to decrease following both CONT and INT training, but only CONT exercise increased fasting GIP. Furthermore, we noted marked increases in GLP-1(active) during the early phase of the OGTT following both exercise treatments (Table 2). Our findings are consistent with this prior work (23) and cross-sectional work showing that trained individuals have lower fasting GLP-1 compared with untrained counterparts (24). In contrast, others have reported no change in fasting GLP-1 (25) or GLP-1 and GIP response to glucose stimulation (25, 32, 43). Collectively, the rise in fasting GIP from CONT exercise, coupled with the rise in early phase GLP-1(active) after both CONT and INT exercise herein, is consistent with our observation for the preservation of GSIS in the presence of increased insulin sensitivity as well as elevated pancreatic function following both treatments in people with prediabetes. Indeed, we report that the change in fasting GIP was associated with tracking fasting circulating C-peptide and insulin. The mechanism by which CONT exercise raised GIP vs. INT is beyond the scope of this study, but it may relate to reductions in DPP-IV (28) and/or altered incretin-pancreas sensitivity (37, 43) since we detected no difference in body/visceral fat or aerobic fitness following exercise. Additional work is warranted to elucidate the mechanism(s) by which exercise dose acts on the pancreas for precision treatment of glucose control.

People with prediabetes (29, 34) and type 2 diabetes (7, 36) have been documented to increase β-cell function following habitual physical activity. In fact, prior work suggests that individuals with low pretreatment β-cell function are likely to increase β-cell function following exercise training (29, 34). This later point is clinically relevant, since even small amounts of exercise could benefit β-cell function (29, 34). However, some have postulated that adults with chronic hyperglycemia or type 2 diabetes have blunted responses to habitual exercise training (7, 22, 35). Herein we show that baseline fasting and 2-h glucose levels tended to relate to increased total-phase β-cell function after training. This is consistent with some work by our group (12) and others (40) showing that people with hyperglycemia derive glucoregulatory benefit from exercise. Nonetheless, additional work is required to elucidate how exercise regulates glucose control in different obese phenotypes and consider the mechanism by which nutrition and/or pharmaceutical intervention alters the exercise effect on pancreatic function (10, 14, 31).

Our interpretations may be affected by the limitations of this study. This is a relatively small sample size without a lean control group. Therefore, it is unclear if our intervention would impact obese adults with prediabetes across age or have differential training responses to healthy controls. Individuals undergoing INT exercise had slightly higher percent heart rates during training on average than CONT exercise. The reason for this likely resides in slowed recovery between high and low intervals. Nonetheless, this is unlikely to impact our results given comparable energy expenditures between treatments. Furthermore, we used the OGTT to assess pancreatic function, and it is possible that this approach did not detect comparable changes in insulin secretion compared with intravenous glucose methods. However, use of the OGTT increases the physiological relevance of our study and provides “real-world” findings that allow simultaneous assessment of incretins. We acknowledge use of surrogate measures of liver and adipose insulin resistance may also underestimate true changes in multiorgan insulin action. However, HOMA-IR and Adipose-IR are valid approaches to estimate hepatic and adipose insulin resistance, respectively, and have been previously used by our group and others (4, 9, 30). Nevertheless, we recognize that further work using stable isotopes to more directly assess skeletal muscle glucose uptake, hepatic glucose production, and lipolytic rate is needed to tease out the role of distinct tissues on pancreatic function. Early phase hepatic insulin extraction increased during the OGTT, suggesting that circulating insulin more efficiently cleared following CONT and INT training. However, CONT exercise decreased total-phase hepatic insulin extraction compared with INT. Although these differences in insulin and C-peptide may influence calculations of insulin metabolism, the relevance of this observation is unclear, since both exercise treatments reduced total-phase glucose, insulin, and C-peptide during the OGTT, and pancreatic function was modeled using C-peptide deconvolution. Nonetheless, it highlights that exercise likely acts in a dose-dependent manner to support glycemia, and further work investigating hepatic insulin extraction is required to understand insulin metabolism postexercise.

In conclusion, short-term exercise training increases GSIS when adjusted to skeletal muscle, but not hepatic or adipose, insulin sensitivity. Independent of intensity, repeated bouts of exercise over 2 wk increased postprandial GLP-1(active). However, only CONT exercise increased fasting GIP. Together, these data indicate that exercise adjusts pancreatic function uniquely between glucose regulatory tissues to support glycemic control in people with prediabetes. Further work is warranted to understand the cross talk between insulin-sensitive tissues and the pancreatic β-cells to optimize treatments that prevent, treat, and/or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the Curry School of Education Foundation, LaunchPad Diabetes, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1-HL-130296 to S. K. Malin.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.K.M. conceived and designed study; S.K.M., M.E.F., N.Z.E., N.M.G., and E.M.H. performed experiments; S.K.M., M.E.F., N.Z.E., N.M.G., E.M.H., C.F., and M.D.B. analyzed data; S.K.M., M.E.F., N.Z.E., N.M.G., E.M.H., C.F., and M.D.B. interpreted results of experiments; S.K.M. prepared figures; S.K.M. drafted manuscript; S.K.M., M.E.F., N.Z.E., N.M.G., E.M.H., C.F., and M.D.B. edited and revised manuscript; S.K.M., M.E.F., N.Z.E., N.M.G., E.M.H., C.F., and M.D.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff and personnel of the Applied Metabolism & Physiology Laboratory who provided insight and discussion to the manuscript and the University of Virginia Clinical Research Unit and Exercise Physiology Core Laboratory staff. We also thank Drs. Arthur Weltman and Eugene Barrett for thoughts on the study and the undergraduate research assistants and subjects for their effort.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdul-Ghani MA, Matsuda M, Balas B, DeFronzo RA. Muscle and liver insulin resistance indexes derived from the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care 30: 89–94, 2007. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amati F, Dubé JJ, Alvarez-Carnero E, Edreira MM, Chomentowski P, Coen PM, Switzer GE, Bickel PE, Stefanovic-Racic M, Toledo FGS, Goodpaster BH. Skeletal muscle triglycerides, diacylglycerols, and ceramides in insulin resistance: another paradox in endurance-trained athletes? Diabetes 60: 2588–2597, 2011. doi: 10.2337/db10-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloem CJ, Chang AM. Short-term exercise improves beta-cell function and insulin resistance in older people with impaired glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 387–392, 2008. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brøns C, Jensen CB, Storgaard H, Hiscock NJ, White A, Appel JS, Jacobsen S, Nilsson E, Larsen CM, Astrup A, Quistorff B, Vaag A. Impact of short-term high-fat feeding on glucose and insulin metabolism in young healthy men. J Physiol 587: 2387–2397, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis CL, Pollock NK, Waller JL, Allison JD, Dennis BA, Bassali R, Meléndez A, Boyle CA, Gower BA. Exercise dose and diabetes risk in overweight and obese children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 308: 1103–1112, 2012. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani MA. Preservation of β-cell function: the key to diabetes prevention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 2354–2366, 2011. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dela F, von Linstow ME, Mikines KJ, Galbo H. Physical training may enhance beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E1024–E1031, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00056.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichner NZM, Gilbertson NM, Gaitan JM, Heiston EM, Musante L, LaSalvia S, Weltman A, Erdbrügger U, Malin SK. Low cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with higher microparticle counts in obese adults. Physiol Rep 6: e13701, 2018. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faerch K, Brøns C, Alibegovic AC, Vaag A. The disposition index: adjustment for peripheral vs. hepatic insulin sensitivity? J Physiol 588: 759–764, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flier SN, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. Evidence for a circulating islet cell growth factor in insulin-resistant states. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7475–7480, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131192998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francois ME, Gilbertson NM, Eichner NZM, Heiston EM, Fabris C, Breton M, Mehaffey JH, Hassinger T, Hallowell PT, Malin SK. Combining short-term interval training with caloric restriction improves ß-cell function in obese adults. Nutrients 10: 6, 2018. doi: 10.3390/nu10060717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbertson NM, Eichner NZM, Francois M, Gaitán JM, Heiston EM, Weltman A, Malin SK. Glucose tolerance is linked to postprandial fuel use independent of exercise dose. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50: 2058–2066, 2018. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Low-dose physical activity attenuates cardiovascular disease mortality in men and women with clustered metabolic risk factors. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 5: 494–499, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handschin C, Choi CS, Chin S, Kim S, Kawamori D, Kurpad AJ, Neubauer N, Hu J, Mootha VK, Kim YB, Kulkarni RN, Shulman GI, Spiegelman BM. Abnormal glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle-specific PGC-1alpha knockout mice reveals skeletal muscle-pancreatic beta cell crosstalk. J Clin Invest 117: 3463–3474, 2007. doi: 10.1172/JCI31785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heiskanen MA, Motiani KK, Mari A, Saunavaara V, Eskelinen JJ, Virtanen KA, Koivumäki M, Löyttyniemi E, Nuutila P, Kalliokoski KK, Hannukainen JC. Exercise training decreases pancreatic fat content and improves beta cell function regardless of baseline glucose tolerance: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 61: 1817–1828, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4627-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn SE, Prigeon RL, McCulloch DK, Boyko EJ, Bergman RN, Schwartz MW, Neifing JL, Ward WK, Beard JC, Palmer JP. Quantification of the relationship between insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in human subjects. Evidence for a hyperbolic function. Diabetes 42: 1663–1672, 1993. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanat M, Mari A, Norton L, Winnier D, DeFronzo RA, Jenkinson C, Abdul-Ghani MA. Distinct β-cell defects in impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes 61: 447–453, 2012. doi: 10.2337/db11-0995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karstoft K, Winding K, Knudsen SH, James NG, Scheel MM, Olesen J, Holst JJ, Pedersen BK, Solomon TPJ. Mechanisms behind the superior effects of interval vs continuous training on glycaemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 57: 2081–2093, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly KR, Brooks LM, Solomon TPJ, Kashyap SR, O’Leary VB, Kirwan JP. The glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucose-stimulated insulin response to exercise training and diet in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E1269–E1274, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00112.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King DS, Staten MA, Kohrt WM, Dalsky GP, Elahi D, Holloszy JO. Insulin secretory capacity in endurance-trained and untrained young men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 259: E155–E161, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.259.2.E155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knudsen SH, Karstoft K, Pedersen BK, van Hall G, Solomon TPJ. The immediate effects of a single bout of aerobic exercise on oral glucose tolerance across the glucose tolerance continuum. Physiol Rep 2: 8, 2014. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krotkiewski M, Lönnroth P, Mandroukas K, Wroblewski Z, Rebuffé-Scrive M, Holm G, Smith U, Björntorp P. The effects of physical training on insulin secretion and effectiveness and on glucose metabolism in obesity and type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 28: 881–890, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF00703130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kullman EL, Kelly KR, Haus JM, Fealy CE, Scelsi AR, Pagadala MR, Flask CA, McCullough AJ, Kirwan JP. Short-term aerobic exercise training improves gut peptide regulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 120: 1159–1164, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00693.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund MT, Dalby S, Hartmann B, Helge J, Holst JJ, Dela F. The incretin effect does not differ in trained and untrained, young, healthy men. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 210: 565–572, 2014. doi: 10.1111/apha.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lund MT, Taudorf L, Hartmann B, Helge JW, Holst JJ, Dela F. Meal induced gut hormone secretion is altered in aerobically trained compared to sedentary young healthy males. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 2737–2747, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2711-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madsen SM, Thorup AC, Overgaard K, Jeppesen PB. High intensity interval training improves glycaemic control and pancreatic β cell function of type 2 diabetes patients. PLoS One 10: e0133286, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magkos F, Tsekouras Y, Kavouras SA, Mittendorfer B, Sidossis LS. Improved insulin sensitivity after a single bout of exercise is curvilinearly related to exercise energy expenditure. Clin Sci (Lond) 114: 59–64, 2008. doi: 10.1042/CS20070134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malin SK, Huang H, Mulya A, Kashyap SR, Kirwan JP. Lower dipeptidyl peptidase-4 following exercise training plus weight loss is related to increased insulin sensitivity in adults with metabolic syndrome. Peptides 47: 142–147, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malin SK, Solomon TPJ, Blaszczak A, Finnegan S, Filion J, Kirwan JP. Pancreatic β-cell function increases in a linear dose-response manner following exercise training in adults with prediabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E1248–E1254, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00260.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malin SK, Rynders CA, Weltman JY, Barrett EJ, Weltman A. Exercise intensity modulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion when adjusted for adipose, liver and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. PLoS One 11: e0154063, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Virkamaki A, Michael MD, Winnay JN, Zisman A, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. A model to explore the interaction between muscle insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 49: 2126–2134, 2000. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieuwoudt S, Fealy CE, Foucher JA, Scelsi AR, Malin SK, Pagadala MR, Rocco M, Burguera B, Kirwan JP. Functional high intensity training improves pancreatic β-cell function in adults with type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 313: E314–E320, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00407.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos JS, Dalleck LC, Borrani F, Mallard AR, Clark B, Keating SE, Fassett RG, Coombes JS. The effect of different volumes of high-intensity interval training on proinsulin in participants with the metabolic syndrome: a randomised trial. Diabetologia 59: 2308–2320, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slentz CA, Tanner CJ, Bateman LA, Durheim MT, Huffman KM, Houmard JA, Kraus WE. Effects of exercise training intensity on pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes Care 32: 1807–1811, 2009. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon TPJ, Malin SK, Karstoft K, Kashyap SR, Haus JM, Kirwan JP. Pancreatic β-cell function is a stronger predictor of changes in glycemic control after an aerobic exercise intervention than insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98: 4176–4186, 2013. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solomon TPJ, Haus JM, Kelly KR, Rocco M, Kashyap SR, Kirwan JP. Improved pancreatic beta-cell function in type 2 diabetic patients after lifestyle-induced weight loss is related to glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide. Diabetes Care 33: 1561–1566, 2010. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tura A, Bagger JI, Ferrannini E, Holst JJ, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T, Mari A. Impaired beta cell sensitivity to incretins in type 2 diabetes is insufficiently compensated by higher incretin response. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 27: 1123–1129, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Utzschneider KM, Prigeon RL, Faulenbach MV, Tong J, Carr DB, Boyko EJ, Leonetti DL, McNeely MJ, Fujimoto WY, Kahn SE. Oral disposition index predicts the development of future diabetes above and beyond fasting and 2-h glucose levels. Diabetes Care 32: 335–341, 2009. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Cauter E, Mestrez F, Sturis J, Polonsky KS. Estimation of insulin secretion rates from C-peptide levels. Comparison of individual and standard kinetic parameters for C-peptide clearance. Diabetes 41: 368–377, 1992. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.41.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Dijk JW, Venema M, van Mechelen W, Stehouwer CDA, Hartgens F, van Loon LJC. Effect of moderate-intensity exercise versus activities of daily living on 24-hour blood glucose homeostasis in male patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 36: 3448–3453, 2013. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viskochil R, Malin SK, Blankenship JM, Braun B. Exercise training and metformin, but not exercise training alone, decreases insulin production and increases insulin clearance in adults with prediabetes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 123: 243–248, 2017. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00790.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vollmer K, Holst JJ, Baller B, Ellrichmann M, Nauck MA, Schmidt WE, Meier JJ. Predictors of incretin concentrations in subjects with normal, impaired, and diabetic glucose tolerance. Diabetes 57: 678–687, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db07-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss EP, Royer NK, Fisher JS, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Postprandial plasma incretin hormones in exercise-trained versus untrained subjects. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46: 1098–1103, 2014. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]