Abstract

Social deficiency is one of the core syndromes of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), for which the underlying developmental mechanism still remains elusive. Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) plays a key role in integrating social information and regulating social behavior. Recent studies have indicated that synaptic dysfunction in ACC is essential for ASD social defects. In the present study, we investigated the development of synapses and the roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), which mediates multiple synaptic signaling pathways in ACC by using Shank3b−/− mice (a widely used ASD mouse model). Our data revealed that Shank3b mutation abolished the social induced c-Fos expression in ACC. From 4 weeks post-birth, neurons in Shank3b−/− ACC exhibited an obvious decrease in spine density and stubby spines. The length and thickness of post-synaptic density (PSD), the expression of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGlut2) and glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2), and the frequency of miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs) were significantly reduced in Shank3b−/−ACC. Interestingly, the levels of phosphorylated GSK-3β (Ser9), which inhibits the activity of GSK-3β, decreased along the same time course as the levels of GluR2 increased in ACC during development. Shank3b mutation leads to a dramatic increase of pGSK-3β (Ser9), and decrease of pPSD95 (a substrate of GSK-3β) and GluR2. Local delivery of AAV expressing constitutively active GSK-3β restored the expression of GluR2, increased the spine density and the number of mature spines. More importantly, active GSK-3β significantly promoted the social activity of Shank3b−/− mice. These data, in together, indicate that decrease of GSK-3β activity in ACC may contribute to the synaptic and social defects of Shank3b−/− mice. Enhancing GSK-3β activity may be utilized to treat ASD in the future.

Keywords: Shank3b, social behavior, anterior cingulate cortex, synapse, glycogen synthase kinase 3β

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are a group of neural developmental disorders characterized by repetitive stereotype behaviors and social defects (Takumi et al., 2019). Hundreds of related genetic mutations have been identified in human patients (Jacob et al., 2019). Among these candidate genes, Src-homology domain 3 (SH3) and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3b (Shank3b) is one of the few genes which can cause the core syndrome of ASD at single mutation (Peca et al., 2011; Varghese et al., 2017). SHANK3 is a post-synaptic scaffold protein widely expressed by excitatory neurons, and interacts with multiple synaptic proteins (Monteiro and Feng, 2017). Even heterozygous Shank3b mice exhibit repetitive grooming and social defects (Dhamne et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2018). Previous studies have revealed that dysfunction of striatum glutamatergic transmission is essential for the repetitive grooming behavior of Shank3b−/− mice (Wang et al., 2017). The mechanism underlying the social deficiency of Shank3b−/− mice remains largely unknown.

Proper social behavior is essential for mammalian survival and reproduction. Among the brain regions involved in the regulation or generation of social behavior, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is regarded as the core region for integrating social information afferents from other brain regions such as the hippocampus, thalamus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC; Apps et al., 2016). Recently, our study demonstrated that the dysfunction of ACC, especially the dysfunction of excitatory synaptic transmission, accounted for the social deficiency in Shank3b−/− mice (Guo et al., 2019). Developmental synaptic deficiency has been proposed to be a key pathological change of ASDs (Lima Caldeira et al., 2019). How Shank3b mutation leads to synaptic defects in ACC is an interesting topic to be explored.

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) is a conserved serine/threonine kinase highly abundant in the brain. It is involved in multiple cellular process and signaling pathways, particularly Wnt signaling and mTOR signaling (Meffre et al., 2014; Hermida et al., 2017). In neurons, the function of GSK-3β is closely related to synaptic development and plasticity (Hur and Zhou, 2010). It can phosphorylate the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), thereby modulating the function of glutamic synapses (Peineau et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2013). Considering that SHANK3B is located mainly in the post-synaptic components of excitatory synapses, we are curious as to whether GSK-3β are involved in the social deficiency of Shank3b−/− mouse.

In the present study, we investigated the synaptic defects in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice during development. Our data demonstrated that the decrease of GSK-3β activity in ACC contributed to the synaptic and social deficiency of Shank3b−/− mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Virus Injection

Shank3b−/− mice were a gift from Prof. Guoping Feng as described (Peca et al., 2011). The mice were maintained and housed in the animal facility of the Fourth Military Medical University at an ambient temperature of 25°C, with a 12 h light and 12 h dark cycle and bred by mating heterozygous male with heterozygous female. The mice were given ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures conducted with mice were in compliance with the guidelines for experimental animal care and use by the Committee of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Fourth Military Medical University. The protocol of animal experiments was approved by the Committee of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Fourth Military Medical University.

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) expressing constitutive active GSK-3β (converting Ser9 into Ala9, 1 × 1013 PFU) driven by hSyn promoter was obtained from BrainVTA (Wuhan, China). The virus was injected into the bilateral ACC of Shank3b−/− mice (4 weeks old) at 0.2 mm right or left to Bregma, 0.75 mm anterior to Bregma with 400 nl per point and 1 mm in depth. AAV expressing luciferase was used as control.

Golgi Staining

Golgi staining was performed as previously described with minor modifications (Zhang et al., 2011). Animals were perfused with 0.9% saline solution or 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). The brain tissue was removed and immersed in Golgi-cox solution (consisting 5% potassium chromate, 5% potassium dichromate, and 5% mercuric chloride) for further fixation, after which the tissue was maintained in the dark at room temperature for 2–3 days. Then, the brains were transferred to a fresh Golgi-Cox Solution for additional 14 days. After that, the brains were transferred to 25%–30% sucrose for 2 more days. Coronal sections (100–200 μm) were cut serially. For staining, brain sections were washed in deionized water for 1 min, placed in 50% NH4OH for 30 min, and subsequently in fixing solution (Kodak; Rochester, NY, USA) for an additional 30 min. The sections were then incubated in 5% sodium thiosulfate for 10 min. After rinsing with distilled water, dehydration with gradient ethanol was performed. The sections were finally mounted and observed under the bright field of confocal microscope FV1000, images were taken by z-stack scanning with the excitation wavelength of 405 nm, and then the virtual color was converted into red color.

Western-Blotting

ACC tissues were carefully dissected and lysed by an RIPA buffer at the presence of a proteinase inhibitors cocktail. Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay. Protein samples were separated in 10%–12% acrylamide gels by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked in TBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBS-T) and 5% (w/v) nonfat milk before incubation with primary antibodies. The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-p-GSK-3β (ser9; 1:1,000; 9323s, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-total GSK- 3β (1:1,000; ab93926, Abcam), rabbit anti-β-catenin (1:1,000; #8480, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-p70-S6 (Thr421/Ser424; 1:1,000; #9204, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-mTOR (1:1,000; 2971s, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-GluR2 (1:1,000; 11994-1-AP, ProteinTech), rabbit anti-pPSD95 (1:1,000; ab172628, Abcam), and rabbit anti-vGlut2 (1:1,000; #71555, CST). After four washes with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Cat. CW0102S, CWBIO Company Limited), or HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Cat. EK020; 1:3,000; Zhuangzhi Biotech Company Limited). Bands were visualized by an ECL kit (Thermo). Images were taken by Tanon imaging system, and analyzed by ImageJ. For quantification of blots, the ratios of in experimental groups were compared to those of control groups.

Behavior Assay

Three-Chamber Test

The 3-Chamber apparatus was an opaque acrylic box with two pull-out doors and three chambers. Each chamber was identical in size (41 × 20 cm), with the dimensions of the entire box being 63 (length) 43 (width) × 23 cm (height). There was a 10-cm gap between adjacent chambers which could be opened or closed with the removable doors. Before tests, mice were individually habituated in the 3-Chamber apparatus for 10 min. After habituation, a C57 stimulus mouse of same age and same sex was placed in the inverted wired cylinder in the “social chamber.” The cylinder in the “non-social chamber” remained empty. The time the tested mice spent in the social vs. non-social chambers during the 10 min test period was measured. Only when all four paws entered the chamber, the mouse was considered to be within a specific chamber. The behaviors of each mouse were video-recorded during the entire test to assess the details of social behavior (rear, contact, sniff, grooming, stretch, withdrawal, and nose-to-nose). The chamber was cleaned by 75% ethanol between each test. The time and traveled distance were analyzed by using SMART3.0 software (Panlab Harvard Apparatus, Spain).

Resident-Juvenile-Intruder Home-Cage Test

Social interaction was examined as described with minor modifications (Felix-Ortiz and Tye, 2014). Briefly, a male adult Shank3b−/− mouse was allowed to explore freely for 1 min (habituation) in his home cage. Another novel juvenile (3–4 weeks old) male C57BL/6 mouse was introduced to the cage and allowed to explore freely for 3 min (test session). Juvenile mice were used to avoid mutual aggression. All behaviors were video recorded and analyzed by a researcher blind to the testing condition. The time and frequency of direct contact (pushing the snout or head underneath the juvenile’s body and crawling over or under the juvenile’s body) were measured.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were sacrificed and perfused intracardially with 4% cold paraformaldehyde phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brain tissue was cryoprotected by 20%–30% sucrose. For each mouse, serial sections (20 μm in thickness for each section) were cut and all the sections were collected onto eight slides. For immunostaining, the sections were blocked by 0.01 M PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h. Primary antibodies were used as following: rabbit anti-c-Fos (1:500; F7799, Sigma), mouse anti-NeuN (1:600; ab104224, Abcam), guinea pig anti-vGluT2 (1:200; 135404, synaptic system), mouse anti-MAP2 (1:400; MAB3418X, Millipore), and rabbit anti-vGlut2 (1:1,000; #71555, CST). After primary antibodies incubation and washing with PBS, sections were incubated with their corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 488 (Jackson Immunoresearch) for 2–4 h at room temperature protected from light. The nuclei were counterstained by DAPI (1:1,000, Sigma). All immunostained sections were photographed under a confocal microscope (FV1000, Olympus) with the same setting.

Electron Microscopic Study

Animals were perfusion fixed with a mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde containing 1% glutaraldehyde. Tissue sections of 50 μm were prepared with a vibratome and further fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated with graded ethanol, replaced with propylene oxide, and flat-embedded in Epon 812. The sections were trimmed under a stereomicroscope and mounted onto blank resin stubs for ultrathin sectioning. Ultrathin sections (70–90 nm) were prepared on an LKB Nova Ultratome (Bromma). After being counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, the sections were examined under a JEM-1230 electron microscope (JEM, Tokyo).

Patch-Clamp Recording

Coronal brain slices (300 μm) at the level of the ACC were prepared. Slices were transferred to submerged recovery chamber with oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) artificial CSF containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, and 10 glucose at room temperature for at least 1 h. The recording pipettes (3–5Ω) were filled with a solution containing (in mM) 145 K-gluconate, 5 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.1 Na3-GTP, and 10 phosphocreatine disodium (adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH). The internal solution (in mM) 140 cesium methanesulfonate, 5 NaCl, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 MgATP, 0.1 Na3GTP, 0.1 spermine, 2 QX-314 bromide, and 10 phosphocreatine disodium (adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH) was used in the experiment. For miniature EPSC miniature excitatory post-synaptic current (mEPSC) recording, 1 μM TTX and 100 μM picrotoxin were added in the perfusion solution. Picrotoxin (100 μM) was present to block GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory synaptic currents. Data were excluded when the resting membrane potential of neurons was more positive than −60 mV and action potentials did not have overshoot. Data were filtered at 1 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz. The mEPSCs were detected and analyzed using Mini Analysis (Synaptosoft Inc., Decatur, GA, USA).

Morphological Analysis

All images of Golgi staining and immunofluorescent staining were taken by Olympus FV1000. For sholl analysis, in cases where individual neurons could not be identified, branches of non-target neurons were manually erased so that the target neuron with full processes was clearly left in the field. The branch intersections and length of dendrites were determined by serial circles surrounding cell body every 5 μm until reaching the end of the longest dendrite using ImageJ. For spine analysis, IMARIS 7.5 filament tracer was used to reconstruct each dendrite. Using customized algorithms, spines were classified as filopodia, stubby, long-thin, or mushroom (Berry and Nedivi, 2017). For the fluorescent intensity, images were taken under the same setting (at least five images from each animal) and analyzed by ImageJ as described (Bhat et al., 2017).

Data Analysis

Western-blotting images were analyzed by ImageJ. For immunohistochemistry and Western-blots, at least three biological repeats were performed for each experiment. For behavior study, at least 15 mice were included in each group. The data were presented as means ± standard error of mean (SEM). The normality was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) except for Sholl analysis which was analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett post hoc using SPSS l6.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) or by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

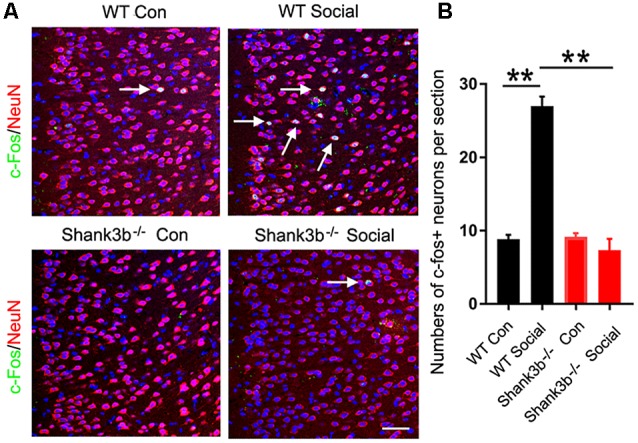

Compromised Response of ACC Neurons to Social Stimulus in Shank3b−/− Mice

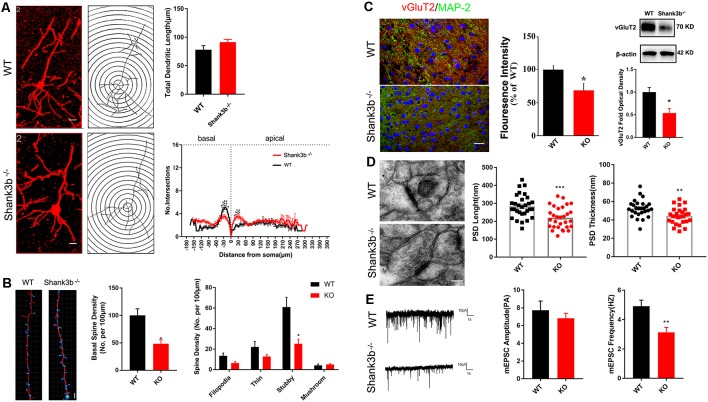

We first analyzed the response of ACC neurons to social stimulation. The expression of c-Fos, a quick-response gene widely used to reflect neuronal activation, was examined at 1 h after the 3-chamber test. The testing mice were placed into the “social chamber” for 10 min, and the control mice placed in the “non-social chamber” for 10 min. The average social time was approximately 270 s. Very few or no c-Fos-positive neurons could be observed in the ACC of both WT and Shank3b−/− mice under control conditions (Figure 1A, left panels; Figure 1B). A lot of c-Fos-positive neurons were found in the ACC of social stimulated WT mice, while the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the ACC of social stimulated Shank3b−/− mice remained at a similar level as that in WT control (Figure 1A, right panels; Figure 1B). Both in WT and Shank3b−/− mice, there was no c-Fos expression in striatum, the key region involved in the grooming phenotype of Shank3b−/− mice (Supplementary Figure S1). These data indicated that ACC, but not striatum, responds to social stimulation, which can be compromised by Shank3b mutation.

Figure 1.

Response of anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) neurons to social stimulation in WT and Shank3b−/− mice. (A) Double-immunostaining of c-Fos/NeuN in the ACC of WT control (Con) mice, social stimulated WT mice (WT social), Shank3b−/− control mice and social stimulated Shank3b−/− mice. (B) Quantification of c-Fos/NeuN-positive cells. Notice that social behavior elicits c-Fos expression in WT ACC but not in Shank3b−/− ACC. Arrows point to double-positive cells. Bar = 120 μm. Values represent mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01. N = 5 mice per group. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Abnormal Synaptic Development in the ACC of Shank3b−/− Mice

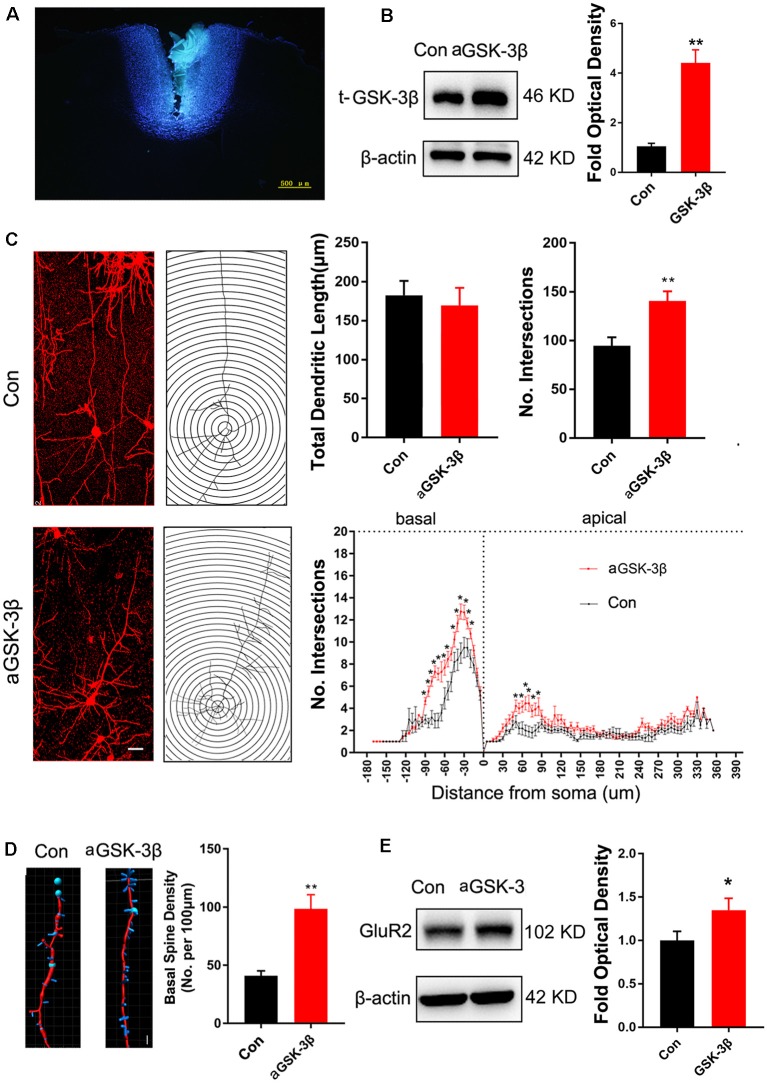

Because SHANK3B is mainly expressed in synaptic sites of excitatory neurons, we focused on the synaptic development of pyramidal neurons in ACC. Golgi staining was conducted at 2, 3, and 4 weeks post-birth. A gradual morphological differentiation was observed. Typical spines along dendrites were not detected until 4 weeks post-birth (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, in the present study, we mainly analyzed phenotype at 4 weeks post-birth. Sholl analysis showed that there was no difference in the total dendritic length between Shank3b−/− ACC neurons and WT ACC neurons. However, significantly less basal dendrite branches and more proximal apical branches were found in Shank3b−/− ACC neurons (Figure 2A), indicating that Shank3b may influence the dendrite development of ACC pyramidal neurons.

Figure 2.

Effects of Shank3b mutation on the dendrite and synapse development in ACC. (A) Sholl analysis of Golgi images of pyramidal neurons in WT and Shank3b−/− ACC 4 weeks post-birth. Notice the fewer branches in the basal dendrites of Shank3b−/− mice of 4 weeks old. (B) Imaris analysis of spines in basal dendrites of WT and Shank3b−/− neurons. Notice the decrease of total spine density and stubby spines. (C) Double-immunostaining of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGlut2)/MAP2 and Western-blotting of vGluT2. Notice the weaker expression of vGluT2 in Shank3b−/− ACC. (D) Electron microscopic study of synaptic ultrastructure in WT and Shank3b−/− ACC at 4 weeks post-birth. The average length and thickness of post-synaptic density (PSD) was reduced. (E) Patch-clamp recording of miniature excitatory post-synaptic current (mEPSC) in WT and Shank3b−/− ACC. Notice the reduction of frequency of mEPSC in Shank3b−/− ACC. Bars = 2 μm (A,B), 150 μm (C) and 135 nm (D). Values represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. N = 6 mice per group in (A,B), 30 neurons per group in (C), five mice per group in (D) and six neurons per group (E). Two-way ANOVA (A), One-way ANOVA (B) and Student’s t-test (C–E).

We next evaluated the spine development in the ACC neurons of Shank3b−/− mice with focus on basal dendrites. Quantification showed that the density of spines along basal dendrites was remarkably reduced in Shank3b−/− neurons as compared with that of WT neurons (Figure 2B, left and middle panels). Further analysis of the sub-types of spines showed that there was no change of immature filodopia and thin spines. However, the number of stubby spines decreased significantly (Figure 2B, right panel), indicating that the maturation of excitatory synapses may be affected by Shank3b mutation. In line with this result, immunohistochemistry and Western-blotting showed that the expression of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGlut2) was significantly reduced in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice (Figure 2C). Electron microscopic study further revealed that the average length and thickness of PSD were significantly reduced in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice (Figure 2D). Further, patch-clamp recording showed that the frequency of mEPSC was significantly reduced in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice (Figure 2E). These data indicate that Shank3b mutation may impair the formation and function of excitatory synapses in ACC.

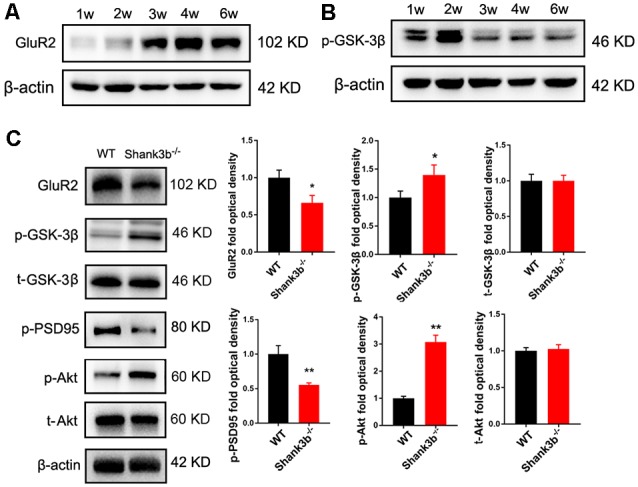

Decrease of GSK-3β Activity and GluR2 Expression in the ACC of Shank3b−/− Mice

To explore the possible underpin mechanisms, we focused on GSK-3β signaling, a key kinase involved in the dendrites growth and polarization of neurons. GSK-3β interacts with multiple signaling pathways, such as Wnt/β-catenin signaling, mTOR signaling and MAPK signaling (Hur and Zhou, 2010; Hermida et al., 2017), and phosphorylates many cytoskeleton proteins (Buttrick and Wakefield, 2008), thereby regulating dendrite development. We first investigated the expression of phosphorylated GSK-3β (p-GSK-3β, Ser 9), an inactive form of GSK-3β, and glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2), a major AMPA receptor which is correlated to synaptic localization of SHANK3 (Grimes and Jope, 2001; Ha et al., 2018). During postnatal development of ACC, the expression of GluR2 increased from 3 weeks, and remained at a high level from then on (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the expression of p-GSK-3β (Ser 9) in ACC dramatically decreased from 3 weeks, and stayed at a low level from then on (Figure 3B). These data revealed an inverse expression trend of GSK-3β activity and GluR2 protein during development. We then analyzed the expression of GSK-3β and GluR2 in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice at 4 weeks (Figure 3C). The expression of GluR2 decreased significantly in Shank3b−/− ACC. The levels of p-GSK-3β (Ser 9) were significantly increased in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice, while the levels of total GSK-3β kept unchanged (Figure 3C). Since p-GSK-3β (Ser 9) is an inhibitory form of GSK-3β, we next examined the phosphorylation of PSD95, a substrate of GSK-3β. The results showed that p-PSD95 was significantly reduced in Shank3b−/− ACC (Figure 3C). Further, we assessed the expression of Akt and p70-S6, two key proteins which modulate GSK-3β activity. The phosphorylation of Akt was increased in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice while the expression of total Akt and p70-S6 remained unchanged (Figure 3C; Supplementary Figure S3A). The levels of p-GSK-3β in mPFC and striatum of Shank3b−/− mice remained at similar levels as those in WT mice (Supplementary Figure S3B). These data indicated that GSK-3β activity is lowered in Shank3b deficient neurons.

Figure 3.

Expression of glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) during postnatal development and in Shank3b−/− ACC. (A) Western-blotting of GluR2 in the ACC of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 weeks (w) old mice. (B) Western-blotting of p-GSK-3β (S9) in the ACC of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 w old mice. Notice the increase of GluR2 and decrease of p-GSK-3β (S9) from 3 w on. (C) Western-blotting of GluR2, p-GSK-3β, total GSK-3β (t-GSK-3β), phosphorylated PSD-95 (pPSD-95), phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), and total Akt (t-Akt) in WT and Shank3b−/− ACC. Notice the up-regulation of p-GSK-3β and p-Akt, and down-regulation of GluR2 and pPSD-95 in Shank3b−/− ACC. Values represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. N = 6 mice per group. Student’s t-test.

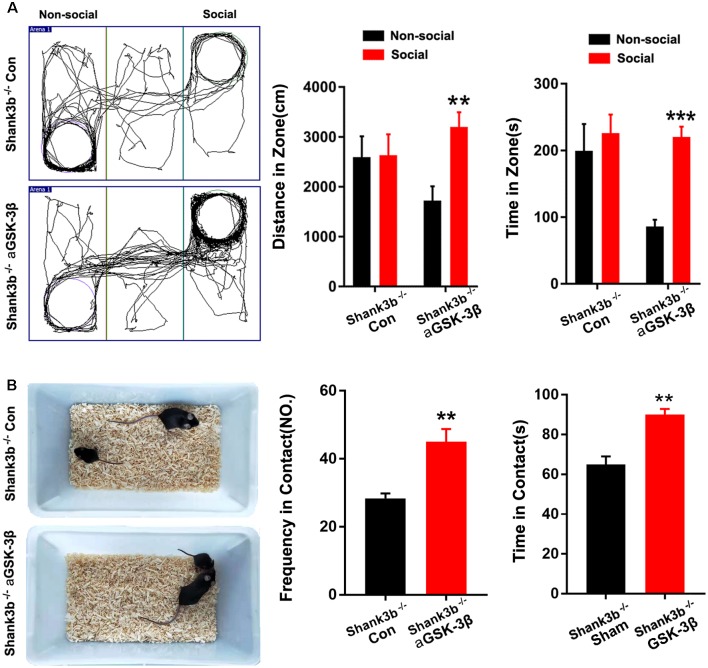

Rescue of Synaptic Development and Social Behavior by ACC Expression of Constitutive Active GSK-3β

To investigate the effects of enhancing GSK-3β activity on synapse development, we injected AAV-expressing constitutive active GSK-3β (aGSK-3β) into the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice. Our preliminary experiments showed that it was very hard to precisely inject the virus into ACC at 3 weeks or earlier, possibly due to the small size of ACC (data not shown). We performed virus injection at 4 weeks post-birth and the area of virus diffusion was determined by mixing Hoeschst33342 with virus aliquots (Figure 4A). Three weeks later, significant up-regulation of total GSK-3β was confirmed by Western-blotting (Figure 4B). Although the total length of dendrites was not significantly affected by aGSK-3β, more dendrite intersections were found in Shank3b−/− ACC treated with aGSK-3β than control (Figure 4C). Further, Sholl analysis showed that branches along both the basal and apical dendrites were significantly increased in aGSK-3β-treated neurons (Figure 4C). More importantly, not only was the spine density increased (Figure 4D), but the mature spines (stubby and mushroom spines) were also remarkably increased (Supplementary Figure S4). In addition, the expression of GluR2 was significantly up-regulated in the Shank3b−/− ACC treated with aGSK-3β (Figure 4E). These data indicated that aGSK-3β could rescue the synapse formation in Shank3b deficient ACC.

Figure 4.

Effects of over-expressing constitutive active GSK-3β (aGSK-3β) in Shank3b−/− ACC on the development of dendrites and spines. (A) Hoescht33342 staining of injection site at 24 h after virus injection in Shank3b−/− mice of 4 weeks old. (B) Western-blotting of t-GSK-3β in ACC at 3 weeks after injecting AAV expressing aGSK-3β. (C) Sholl analysis of Golgi images of pyramidal neurons in control and aGSK-3β treated Shank3b−/− ACC. Notice the increase of dendritic intersections, and particularly basal branches in the aGSK-3β treated Shank3b−/− neurons. (D) Imaris analysis of spines along basal dendrites of control and aGSK-3β treated Shank3b−/− neurons. Notice the increase of spine density by aGSK-3β. Values represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. Bar = 20 μm (C) and 2 μm (D). N = 3 mice per group (B), and 6 mice per group (C–E). Student’s t-test (A,D,E). Two-way ANOVA (B).

We next tested whether over-expressing aGSK-3β in ACC could affect the social behavior of Shank3b−/− mice. In the 3-chamber test which measures social approach and preference for social novelty, control Shank3b−/− mice spent similar time exploring the cylinder containing social mice as exploring the empty cylinder (Figure 5A). Shank3b−/− mice treated with aGSK-3β spent obviously more time in the box containing social mice (Figure 5A). In the resident-juvenile-intruder home-cage test which measures social interaction, Shank3b−/− mice treated with aGSK-3β showed significantly more direct contact with the juvenile intruder, while Shank3b−/− mice treated with control virus showed no obvious interests to the juvenile intruder (Figure 5B). These data suggested that over-expressing aGSK-3β in ACC can rescue the social deficiency of Shank3b−/− mice.

Figure 5.

Effects of over-expressing aGSK-3β in Shank3b−/− ACC on social behavior. (A) Three-chamber tests of control Shank3b−/− mice and Shank3b−/− mice treated with aGSK-3β at 3 weeks after virus injection. Notice that aGSK-3β treatment significantly rescued the social preference of Shank3b−/− mice. (B) Resident-juvenile-intruder home-cage test of control Shank3b−/− mice and Shank3b−/− mice treated with aGSK-3β. Notice that aGSK-3β treatment significantly enhanced social contact of Shank3b−/− mice with juvenile intruder. Values represent mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001. N = 15 mice per group (A,B). One-way ANOVA (A). Student’s t-test (B).

Discussion

Recently, we reported that ACC is a key region for the social deficit of Shank3b−/− mice. In the present study, we further analyzed the effects of Shank3b mutation on the morphological development of ACC neurons with focus on synaptogenesis. Our data revealed a defect of excitatory synaptic development and a decrease of GSK-3β activity in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice. Interestingly, the expression of constitutive active GSK-3β in ACC rescued both the synaptic and social deficiency caused by Shank3b mutation. Our data further supported a crucial role of ACC in social function. Considering the extensive connection of ACC, it will be interesting to investigate how the interaction between ACC and its connecting regions, such as PFC, affects social behavior.

Of the current hypothesis about the development of ASD, “developmental synaptopathie” has drawn more and more attention in recent years (Ebrahimi-Fakhari and Sahin, 2015), which implies that the disruption of the synaptic excitation and inhibition (E/I) is crucial for the progress of ASD (Howell and Smith, 2019). Shank3 is one of the few genes whose single mutation is sufficient to induce typical autism syndrome. The dysfunction of excitatory synapses in the striatum of Shank3−/− mice has been attributed to the reduction of NMDA/AMPA ratio which in turn results in the silence of excitatory synapses (Jaramillo et al., 2016). Our data showed that in the ACC of Shank3−/− mice, the density of spines, the length and thickness of PSD, and the expression of GluR2 were significantly reduced. These data demonstrated the abnormal development of excitatory synapses in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice. The reduction of vGluT2 is interesting. Our electrophysiological data are in line with this observation. It is possible that post-synaptic SHANK3B may affect synaptic transmission through neurexin-neuroligin-mediated transsynaptic signaling (Arons et al., 2012). Considering that previous studies have reported presynaptic localization of Shank3 in developing neurons (Halbedl et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2017) and that our data were obtained at 4w post-birth, it may be possible that SHANK3 may play a role in the presynaptic function during development. Because SHANK3B could also be expressed by GABAergic neurons, the possibility that abnormal inhibition may affect the morphology of neurons and regulate the structural and functional plasticity of glutamatergic synapses is interesting, and deserves to be further investigated.

The existence of six protein-protein interaction domains in SHANK3B imparts it with the ability to interact with or affect diverse synaptic proteins. Dozens of Shank3-interacting proteins have been identified, such as Contactin, Homer, and SAPAP (Monteiro and Feng, 2017). Recently, SHANK3B has been reported to directly interact with β-catenin (Qin et al., 2018), a Wnt signaling protein which can modulate synapse formation and stability. As an upstream molecule of β-catenin in Wnt signaling, GSK-3β is mainly distributed in post-synaptic components. Our data showed a significant enhancement of p-GSK-3β (S9) in the ACC of Shank3b−/− mice, suggesting that GSK-3β activity was inhibited in Shank3b−/− mice, which is consistent with previous reports that Wnt/β-catenin is activated in Shank3b deficient PFC (Qin et al., 2018). The inverse expression trend of GSK-3β and GluR2, and the rescue effects of aGSK-3β on GluR2 indicated a relationship between the expression of GluR2 and GSK-3β activity. The involvement of GSK-3β in the synapse dysfunction of other ASD models (e.g., FMR1−/− mice) has been documented (Mines et al., 2010; Caracci et al., 2016). Knocking out GSK-3β in neurons resulted in fewer spines (Kondratiuk et al., 2017), similar to what we have observed. Whether SHANK3B could directly interact with GSK-3β is worthy of further exploration.

Importantly, our data showed that expressing constitutive active GSK-3β in Shank3b−/− ACC could rescue both synaptic development and social function. The rescue of GluR2 expression may be achieved by its downstream β-catenin signaling. So far, there still lacks effective treatment for the social deficiency in ASD patients. Considering too much activation of GSK-3β by constitutive a GSK-3β may lead to inhibitory effects, pharmacologically enhancing GSK-3β activity might be an alternative for the improving social behavior in ASD patients.

Considering the multiple signaling GSK-3β involved and the wide distribution of GSK-3β, it is possible that this synaptic function of SHANK3B may also be important for the pathology of many other neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Schizophrenia.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Committee of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Fourth Military Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

Author Contributions

MW, XL and YH conducted most of the experiments, collected and analyzed the data. HZ and YZ contributed to morphological analysis. JK contributed to electron microscropic study. FW contributed to electrophysiology. JC contributed to Golgi staining. XL contributed to behavior analysis. SW and YW conceived the study, provided financial support, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Li Zhang, Lirong Liang, and Chuchu Qi for their technical help, and Prof. Wenting Wang for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China to SW (Grant No. 81730035) and to YW (Grant No. 81571224).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2019.00447/full#supplementary-material.

Double-immunostaining of c-Fos with NeuN in the striatum of WT and Shank3b−/− mice after social stimulation. Notice that there are no c-Fos-positive cells in the striatum of WT and Shank3b−/− mice after social stimulation.

Images of Golgi staining in ACC at 2w (A), 3w (C) and 4w (E) post-birth. Images of dendritic spines in pyramidal neurons at 2w (B), 3w (D) and 4w (F) post-birth 4.

(A) Western blotting and quantification of p70-S6 in WT ACC and Shank3b−/− ACC. N = 6 mice per group. (B) Western-blotting and quantification of p-GSK-3βin the mPFC and striatum of WT and Shank3b−/− mice. N = 4 mice per group.

Densities of different types of basal spines of control and aGSK-3β treated Shank3b−/− ACC. Notice the increase of stubby and mushroom spines by aGSK-3β. Values represent mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

References

- Apps M. A., Rushworth M. F., Chang S. W. (2016). The anterior cingulate gyrus and social cognition: tracking the motivation of others. Neuron 90, 692–707. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arons M. H., Thynne C. J., Grabrucker A. M., Li D., Schoen M., Cheyne J. E., et al. (2012). Autism-associated mutations in ProSAP2/Shank3 impair synaptic transmission and neurexin-neuroligin-mediated transsynaptic signaling. J. Neurosci. 32, 14966–14978. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2215-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry K. P., Nedivi E. (2017). Spine dynamics: are they all the same? Neuron 96, 43–55. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S. A., Goel R., Shukla R., Hanif K. (2017). Platelet CD40L induces activation of astrocytes and microglia in hypertension. Brain Behav. Immun. 59, 173–189. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttrick G. J., Wakefield J. G. (2008). PI3-K and GSK-3: Akt-ing together with microtubules. Cell Cycle 7, 2621–2625. 10.4161/cc.7.17.6514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caracci M. O., Ávila M. E., De Ferrari G. V. (2016). Synaptic Wnt/GSK3β signaling hub in autism. Neural Plast. 2016:9603751. 10.1155/2016/9603751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhamne S. C., Silverman J. L., Super C. E., Lammers S. H. T., Hameed M. Q., Modi M. E., et al. (2017). Replicable in vivo physiological and behavioral phenotypes of the Shank3B null mutant mouse model of autism. Mol. Autism 8:26. 10.1186/s13229-017-0142-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi-Fakhari D., Sahin M. (2015). Autism and the synapse: emerging mechanisms and mechanism-based therapies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 28, 91–102. 10.1097/wco.0000000000000186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz A. C., Tye K. M. (2014). Amygdala inputs to the ventral hippocampus bidirectionally modulate social behavior. J. Neurosci. 34, 586–595. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4257-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes C. A., Jope R. S. (2001). The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3β in cellular signaling. Prog. Neurobiol. 65, 391–426. 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., Chen J., Chen Q., Ren K., Feng D., Mao H., et al. (2019). Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction underlies social deficits in Shank3 mutant mice. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1223–1234. 10.1038/s41593-019-f13780445-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha H. T. T., Leal-Ortiz S., Lalwani K., Kiyonaka S., Hamachi I., Mysore S. P., et al. (2018). Shank and zinc mediate an AMPA receptor subunit switch in developing neurons. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:405. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbedl S., Schoen M., Feiler M. S., Boeckers T. M., Schmeisser M. J. (2016). Shank3 is localized in axons and presynaptic specializations of developing hippocampal neurons and involved in the modulation of NMDA receptor levels at axon terminals. J. Neurochem. 137, 26–32. 10.1111/jnc.13523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermida M. A., Dinesh Kumar J., Leslie N. R. (2017). GSK3 and its interactions with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling network. Adv. Biol. Regul. 65, 5–15. 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell B. W., Smith K. M. (2019). Synaptic structural protein dysfunction leads to altered excitation inhibition ratios in models of autism spectrum disorder. Pharmacol. Res. 139, 207–214. 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur E. M., Zhou F. Q. (2010). GSK3 signalling in neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 539–551. 10.1038/nrn2870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob S., Wolff J. J., Steinbach M. S., Doyle C. B., Kumar V., Elison J. T. (2019). Neurodevelopmental heterogeneity and computational approaches for understanding autism. Transl. Psychiatry 9:63. 10.1038/s41398-019-0390-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo T. C., Speed H. E., Xuan Z., Reimers J. M., Liu S., Powell C. M. (2016). Altered striatal synaptic function and abnormal behaviour in Shank3 Exon4–9 deletion mouse model of autism. Autism Res. 9, 350–375. 10.1002/aur.1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratiuk I., Łęski S., Urbańska M., Biecek P., Devijver H., Lechat B., et al. (2017). GSK-3β and MMP-9 cooperate in the control of dendritic spine morphology. Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 200–211. 10.1007/s12035-015-9625-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima Caldeira G., Peça J., Carvalho A. L. (2019). New insights on synaptic dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 57, 62–70. 10.1016/j.conb.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffre D., Grenier J., Bernard S., Courtin F., Dudev T., Shackleford G., et al. (2014). Wnt and lithium: a common destiny in the therapy of nervous system pathologies? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 1123–1148. 10.1007/s00018-013-1378-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mines M. A., Yuskaitis C. J., King M. K., Beurel E., Jope R. S. (2010). GSK3 influences social preference and anxiety-related behaviors during social interaction in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome and autism. PLoS One 5:e9706. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro P., Feng G. (2017). SHANK proteins: roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 147–157. 10.1038/nrn.2016.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. D., Kim M. J., Hsin H., Chen Y., Sheng M. (2013). Phosphorylation of threonine-19 of PSD-95 by GSK-3β is required for PSD-95 mobilization and long-term depression. J. Neurosci. 33, 12122–12135. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0131-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peca J., Feliciano C., Ting J. T., Wang W., Wells M. F., Venkatraman T. N., et al. (2011). Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction. Nature 472, 437–442. 10.1038/nature09965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peineau S., Taghibiglou C., Bradley C., Wong T. P., Liu L., Lu J., et al. (2007). LTP inhibits LTD in the hippocampus via regulation of GSK3β. Neuron 53, 703–717. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L., Ma K., Wang Z. J., Hu Z., Matas E., Wei J., et al. (2018). Social deficits in Shank3-deficient mouse models of autism are rescued by histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 564–575. 10.1038/s41593-018-0110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takumi T., Tamada K., Hatanaka F., Nakai N., Bolton P. F. (2019). Behavioral neuroscience of autism. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese M., Keshav N., Jacot-Descombes S., Warda T., Wicinski B., Dickstein D. L., et al. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder: neuropathology and animal models. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 537–566. 10.1007/s00401-017-1736-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Li C., Chen Q., van der Goes M. S., Hawrot J., Yao A. Y., et al. (2017). Striatopallidal dysfunction underlies repetitive behavior in Shank3-deficient model of autism. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 1978–1990. 10.1172/jci87997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Gan G., Zhang Z., Sun J., Wang Q., Gao Z., et al. (2017). A presynaptic function of shank protein in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 37, 11592–11604. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0893-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Li A., Yang Z., Wu J., Luo Q., Gong H. (2011). Modified Golgi-Cox method for micrometer scale sectioning of the whole mouse brain. J. Neurosci. Methods 197, 1–5. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Double-immunostaining of c-Fos with NeuN in the striatum of WT and Shank3b−/− mice after social stimulation. Notice that there are no c-Fos-positive cells in the striatum of WT and Shank3b−/− mice after social stimulation.

Images of Golgi staining in ACC at 2w (A), 3w (C) and 4w (E) post-birth. Images of dendritic spines in pyramidal neurons at 2w (B), 3w (D) and 4w (F) post-birth 4.

(A) Western blotting and quantification of p70-S6 in WT ACC and Shank3b−/− ACC. N = 6 mice per group. (B) Western-blotting and quantification of p-GSK-3βin the mPFC and striatum of WT and Shank3b−/− mice. N = 4 mice per group.

Densities of different types of basal spines of control and aGSK-3β treated Shank3b−/− ACC. Notice the increase of stubby and mushroom spines by aGSK-3β. Values represent mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.