Abstract

The development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with the loss of functional nephrons. However, there are no methods to directly measure nephron number in living subjects. Thus, there are no methods to track the early stages of progressive CKD before changes in total renal function. In this work, we used cationic ferritin-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CFE-MRI) to enable measurements of glomerular number (Nglom) and apparent glomerular volume (aVglom) in vivo in healthy wild-type (WT) mice (n = 4) and mice with oligosyndactylism (Os/+; n = 4), a model of congenital renal hypoplasia leading to nephron reduction. We validated in vivo measurements of Nglom and aVglom by high-resolution ex vivo MRI. CFE-MRI measured a mean Nglom of 12,220 ± 2,028 and 6,848 ± 1,676 (means ± SD) for WT and Os/+ mouse kidneys in vivo, respectively. Nglom measured in all mice in vivo using CFE-MRI varied by an average 15% from Nglom measured ex vivo in the same kidney (α = 0.05, P = 0.67). To confirm that CFE-MRI can also be used to track nephron endowment longitudinally, a WT mouse was imaged three times by CFE-MRI over 2 wk. Values of Nglom measured in vivo in the same kidney varied within ~3%. Values of aVglom calculated from CFE-MRI in vivo were significantly different (~15% on average, P < 0.01) from those measured ex vivo, warranting further investigation. This is the first report of direct measurements of Nglom and aVglom in healthy and diseased mice in vivo.

Keywords: cationic ferritin, glomerulus, magnetic resonance imaging, mouse, nephron number, oligosyndactylism

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects ~14% of the United States population and ~10% of the world population (15). Progressive CKD is characterized by the gradual loss of kidney function. Standard clinical approaches to estimate kidney function include the use of endogenous biomarkers such as serum creatinine or cystatin C (31, 33). Although these approaches are useful in advanced CKD, the lack of tools to detect in the earliest stages of CKD contributes to delays in diagnosis and therapy (14). As a result, kidney disease is undetected in 48% of patients who are not on dialysis but have reduced kidney function (10a).

The progression of CKD is often associated with nephron loss. During nephron loss, net glomerular filtration rate is maintained by the remaining nephrons, which are thought to compensate through glomerular hypertrophy (10, 16, 29, 32). Glomerular hypertrophy is thought to precipitate further damage to the remaining nephrons, leading to renal failure. A tool to measure and track the number of functioning nephrons in the living subject could provide an important metric to monitor kidney health and function. A novel tool to measure nephron number in vivo is cationic ferritin (CF)-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (CFE-MRI), which enables the nondestructive measurement of nephron number in the whole kidney (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 11). CFE-MRI uses a modified form of ferritin to enhance glomeruli against tissue background in images. Ferritin is a highly conserved iron-storing protein expressed in most cells and forms a 13-nm, 24-mer shell with a hollow or filled core used for iron storage. The iron oxide nanoparticle (~7 nm in diameter) typically formed in the ferritin core can change MR image contrast by shortening transverse relaxation times (T2 and T2*). CF is formed by conjugating the ferritin shell to a short amine-containing crosslinker. After intravenous injection, CF binds electrostatically to anionic glycoproteins of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and is detected with gradient-echo MRI as a dark punctate spot at the site of the glomerulus. CFE-MRI has been recently used in ex vivo studies to accurately measure glomerular number and size in the kidneys of mice, rats, and humans (2, 3, 6, 7, 23).

We have used CFE-MRI to measure glomerular number (Nglom) and the distribution of individual glomerular volumes (IGV) in vivo in rats (1). However, many important genetic models of human kidney disease are developed in mice, making it important to improve CFE-MRI for the detection of glomeruli in mice in vivo. CFE-MRI in mouse kidneys has been limited by several major technical challenges. The volume of the mouse glomerulus is approximately one-third that of the rat glomerulus, requiring higher image resolution (2, 6, 9, 21, 34). Increasing MR image resolution to resolve the mouse glomerulus reduces the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by >50% compared with the rat. A decrease in SNR can require multiple averaged images and increased scan time to detect the labeled glomeruli. Thus, measuring nephron endowment in mice requires significant improvements in image acquisition.

Here, we developed new hardware and image acquisition strategies for CFE-MRI to measure nephron endowment in the mouse kidney in vivo. Nephron endowment was measured in the kidneys of healthy mice and an oligosyndactylism (Os/+) murine model of oligomeganephronia. The Os/+ model has a reduced kidney mass and glomerular hypertrophy without evidence of glomerulosclerosis or fibrosis (37). This work establishes the principles of measuring nephron endowment at single time points or longitudinally in live mouse models of human disease.

METHODS

Hardware design.

We designed and constructed a custom transmit/receive surface radiofrequency (RF) coil for in vivo MRI of a single kidney. The design of the coil was inspired by Doty et al. (17). Multiloop coils were created with variable tuning and matching capacitors (Johanson Manufacturing) and a fixed capacitor for power balancing. Several RF coil prototypes were constructed with variable numbers of loops. We serially assessed RF penetration depth and SNR in MR images using each RF coil and a phantom containing 2% agar in 0.9% saline. A variable number of loops of three and loop diameter of 20 mm provided the highest SNR along with complete coverage of a mouse kidney and was used for all subsequent experiments. Initial tuning and matching of the RF coil was performed using the phantom. To ensure the acquisition of signal throughout the entire kidney, we acquired a map of the RF field, B1. The spatial variation in flip angle (α) was calculated from B1. For this, we used a gradient echo dual-angle method as previously described [echo time (TE)/repetition time (TR) = 5/10,000, resolution = 0.1172 × 0.1172 × 2 mm3, α = 45°; see Ref. 1]. We found the working area of our RF coil was sufficiently sensitive up to 6 mm from its surface, ensuring an error in apparent glomerular volume (aVglom) of <10% across the kidney.

In vivo MRI.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia approved all animal experiments. Male mice between 9 and 16 wk of age and weighing between 20 and 30 g were used to avoid sex-related variability (25). The RF coil was tuned and matched before imaging each animal. We performed a pilot study to assess 1) the minimum number of image averages needed to detect glomeruli in vivo in mice and 2) the minimum resolution required to identify glomeruli against the surrounding tissue with the administered dose of CF. For this experiment, wild-type (WT) C57/BL6N (n = 4) mice received CF intravenously through the tail vein, and one additional WT mouse received no CF as a control. Numerous published studies have confirmed that the renal cortex does not exhibit contrast in perfused kidneys, including mice, that are not labeled by CF (2, 5, 6, 8, 23). We used a single uninjected mouse as a control to reconfirm our multiple previous observations of no glomerular enhancement without the use of CF. We compared the kidneys of WT mice with Os/+ mice (n = 4). Os/+ mice were bred with a C57/BL6N background, and fusion of the digits on each limb confirmed the Os/+ mutation (19, 20, 37). The dose of CF was 7.68 mg/100 g body wt over four total injections (1.92 mg/100 g for each injection) separated by 90-min intervals. This dose was chosen through a pilot study based on detectability with the custom RF coil and acquisition parameters. Both WT and Os/+ cohorts received CF as described above.

Ninety minutes after final injection, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen for in vivo MRI. We used a custom animal support device with an insert for the RF coil to reduce movement during imaging. The respiratory rate was monitored using a pneumatic pillow and was maintained at 50–60 breaths/min by adjusting isoflurane concentration. A heating pad set to 38°C was placed next to the body. Mice were imaged using a Bruker 7T/30 MRI (Bruker, Billerica, MA) with Siemens software for acquisition and reconstruction (Siemens, Munich, Germany). We used a three-dimensional gradient recalled echo (GRE) pulse sequence (pilot study: TE/TR = 14/70, resolution = 54.7 × 54.7 × 100.0 μm3, α = 30; cohort study: TE/TR = 14/70, resolution = 54.7 × 109.4 × 50.0 μm3, α = 30) with flow compensation in the read direction to correct for flow-related dephasing. We used the right kidney only in each mouse for in vivo imaging. The SNR of each image was calculated as described in SNR measurements. We used the SNR of a single image to determine the number of averaged images (Navg) required to achieve our target threshold SNR of 6.5, which was Navg = 3. All three-dimensional images were acquired separately and coregistered in postprocessing. After in vivo imaging, animals received an intraperitoneal injection of euthasol (0.1 ml/animal). Animals were perfused transcardially with saline followed by 10% formalin. Right kidneys were resected and stored in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate for ex vivo MRI. Left kidneys were resected and stored in 10% formalin.

SNR measurements.

We estimated the SNR in each kidney in in vivo images. Briefly, we applied a Gaussian filter with a window size of 8 voxels in the cortex and repeated this an additional three times. Next, a region of interest (ROI) of size 50 × 50 × 5 voxels was obtained in empty space outside the mouse. We calculated SNR using the equation:

| (1) |

where SMean,Kidney is the average signal calculated in the kidney and σROI-Noise is the calculated standard deviation of noise from the ROI in empty space. All calculations were performed in Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Ex vivo MRI.

Ex vivo MRI has become a reliable method to measure Nglom and has been validated by stereology in Os/+ and healthy WT mice (2). Thus, we used ex vivo MRI to validate the value of Nglom in each mouse kidney. Resected kidneys were imaged together in a solution of 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate using a three-dimensional GRE pulse sequence (TE/TR = 20/80, resolution = 40.6 × 40.6 × 60.0 μm3, α = 30). Individual kidneys were manually segmented from background using Amira software (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

In vivo image analysis.

For postprocessing, images were first resized to a resolution of 13.7 × 27.3 × 12.5 μm3 using a Lanczos interpolation method. Images were then coregistered using Affine Registration in Amira and finally averaged together. The whole kidney and cortex were manually segmented from the images with Amira. We created a custom algorithm to identify CF-labeled glomeruli from in vivo images using a combination of MIPAR (MIPAR Image Analysis, Worthington, OH) and Matlab software. First, an adaptive threshold was applied to segmented images. Variables for MIPAR’s adaptive threshold were as follows: percentage, 53%, and window size, 15. We used Matlab for the remaining analyses. A standard watershed transformation was next applied to the remaining candidate glomeruli. We measured total Nglom using the “bwconncomp” function in MATLAB and with a three-dimensional connectivity of 26. This produced a three-dimensional map of glomeruli in the mouse kidney in vivo.

We calculated glomerular volume using intensity profiles of signal magnitude acquired in a single direction and through the center of each glomerulus. The glomerulus center was the voxel with the lowest signal magnitude. Intensity profiles of signal magnitude were obtained in orthogonal directions and at a length of 17 voxels. The magnitude values from each intensity profile acquired from orthogonal directions were averaged to create a single intensity profile of average signal magnitude, referred to as the mean profile. We analyzed glomerulus size in the following two cases: 1) with the mean profile calculated using two profiles along the directions of smallest resolution as prescribed in a previous publication (2) and 2) with the mean profile calculated using all three profile directions. We calculated IGV from the mean profile using the full width at half-minimum (FWHM) as the diameter of the glomerulus and a spherical model equation:

| (2) |

We compared aVglom measurements obtained from mean profiles calculated using either two or three profile directions. aVglom for each kidney was the median IGV in each kidney.

Longitudinal study.

A WT mouse was imaged on three different days to determine whether CFE-MRI could track glomerular number longitudinally. Dosing and imaging parameters were the same as described in In vivo MRI. On day 1, the mouse received CF and was imaged with in vivo MRI to confirm glomerular labeling. On day 7, the mouse received no CF and was again imaged with in vivo MRI to confirm no labeling of glomeruli in the kidney. This time point was chosen based on a previous publication (4) that used 0.75 times the dose of CF used in the present study and showed no labeling of glomeruli from residual CF after 2 days. On day 14, the mouse received CF once more and was imaged in vivo to confirm labeling of glomeruli, similar to day 1. After imaging on day 14, the animal was euthanized, and kidneys were resected as described in In vivo MRI. Kidneys were stored in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate for ex vivo MRI.

Ex vivo image analysis.

The kidney and cortex were segmented in ex vivo images of each mouse kidney. We developed a custom algorithm optimized for ex vivo images using MIPAR and Matlab software. The images were first resized to a resolution of 10.2 × 10.2 × 30 μm3 using a Lanczos interpolation method. We then used MIPAR’s Smart Cluster algorithm (parameters: classes = 4, edge clean = 0, speed = 1) to separate features. Next, an adaptive threshold was used to isolate labeled glomeruli. Variables for MIPAR’s adaptive threshold were as follows: percentage, 56%, and window size, 15. Finally, a size-exclusion operation was performed to omit apparent glomeruli smaller than a cluster size of 5 voxels, too small to be a mouse glomerulus (35). We used Matlab to implement the remaining analyses. Nglom was measured as in the in vivo measurements, resulting in three-dimensional maps of glomeruli in ex vivo images of mouse kidneys. IGV and aVglom were measured as described above in In vivo image analysis. Intensity profiles were 23 voxels long.

Mapping glomerular volume.

Slices from both in vivo and ex vivo MR images of the kidney were randomly sampled. Identified glomeruli were marked in sample images and color coded based on IGV. Glomeruli were grouped in five size ranges as follows: 1) 0–1, 2) 1–2, 3) 2–4, 4) 4–6, and 5), >6 × 10−4 mm3. For visualization, we used circles of varying radius size corresponding to the glomerular size for each group. Radii were 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 voxels, respectively. Matlab was used to make and visualize maps of IGV. For each identified glomerulus, the geometric centroid was calculated for the glomerulus center, and the distance of each glomerulus center from the edge of the kidney was computed.

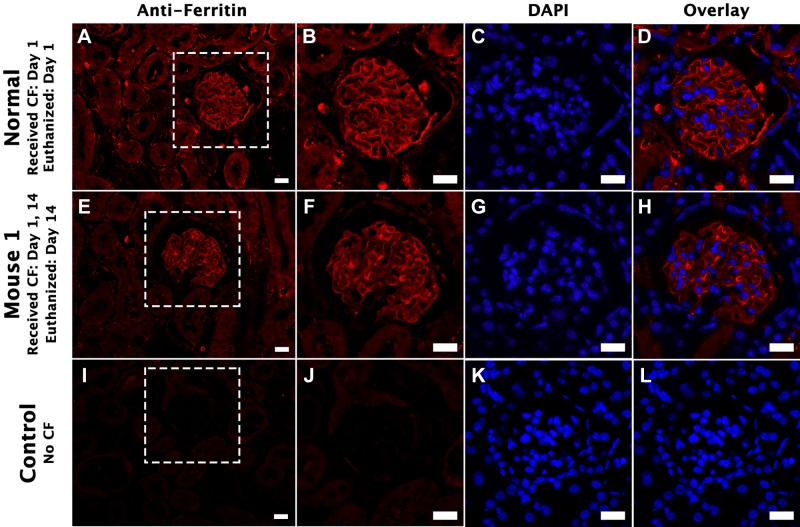

Histology.

Immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy was used to confirm the binding of CF to the GBM. IF was performed on the following samples: 1) a WT mouse that received CF on day 1, followed by imaging with MRI and then euthanized on the same day, 2) a WT mouse that received CF on days 1 and 14, and 3) a control mouse that did not receive CF. Briefly, kidney sections were embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were next cut on a Leica microtome (Leica Biosystems), and sections were deparaffinized with xylene followed by ethanol baths of 100%, 95%, and 70% and a final wash in distilled H2O. An antigen retrieval step was performed using a 10% citrate buffer and a PBS wash. Sections were blocked with normal donkey serum (catalog no. 566460, Calbiochem) followed by a PBS wash. Sections were incubated overnight with primary ferritin antibody (1:100, catalog no. F6136, Sigma-Aldrich) followed by a PBS wash. Sections were bathed for 2 h with secondary antibody (donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594, 1:500, catalog no. A21207, Life Technologies) followed by a PBS wash. Sections were then counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:2,000), dehydrated in washes of distilled H2O, 100% ethanol, and xylene, and finally mounted on a slide using VectaMount AQ (catalog no. H-5501, Vector Laboratories).

Statistics.

Standard deviations (SDs) are reported with all mean measurements. A Student’s paired t-test was used with a significance threshold of 0.05 to test the null hypothesis of no significant difference between in vivo and ex vivo measurements. Separate t-tests were performed for Nglom and aVglom. Matlab was used for all calculations using the function “ttest2.” A Student’s paired t-test was also calculated between mean IGV distributions of WT and Os/+ cohorts in overlapping histogram bins in vivo and ex vivo.

A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was measured for the glomerulus segmentation algorithm from randomly sampled ROIs in the renal cortex and using manual segmentation in the same ROI as ground truth. ROC analysis was performed using Matlab.

RESULTS

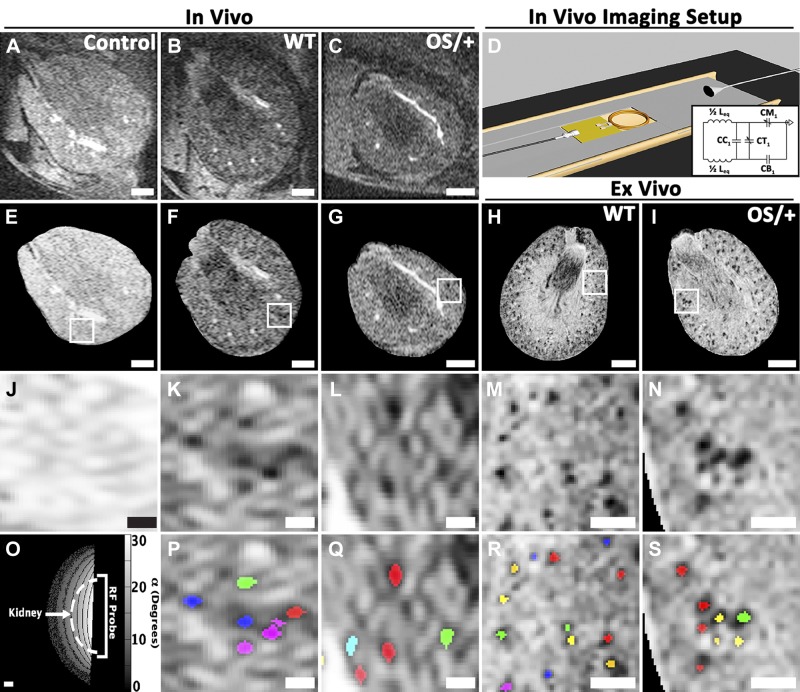

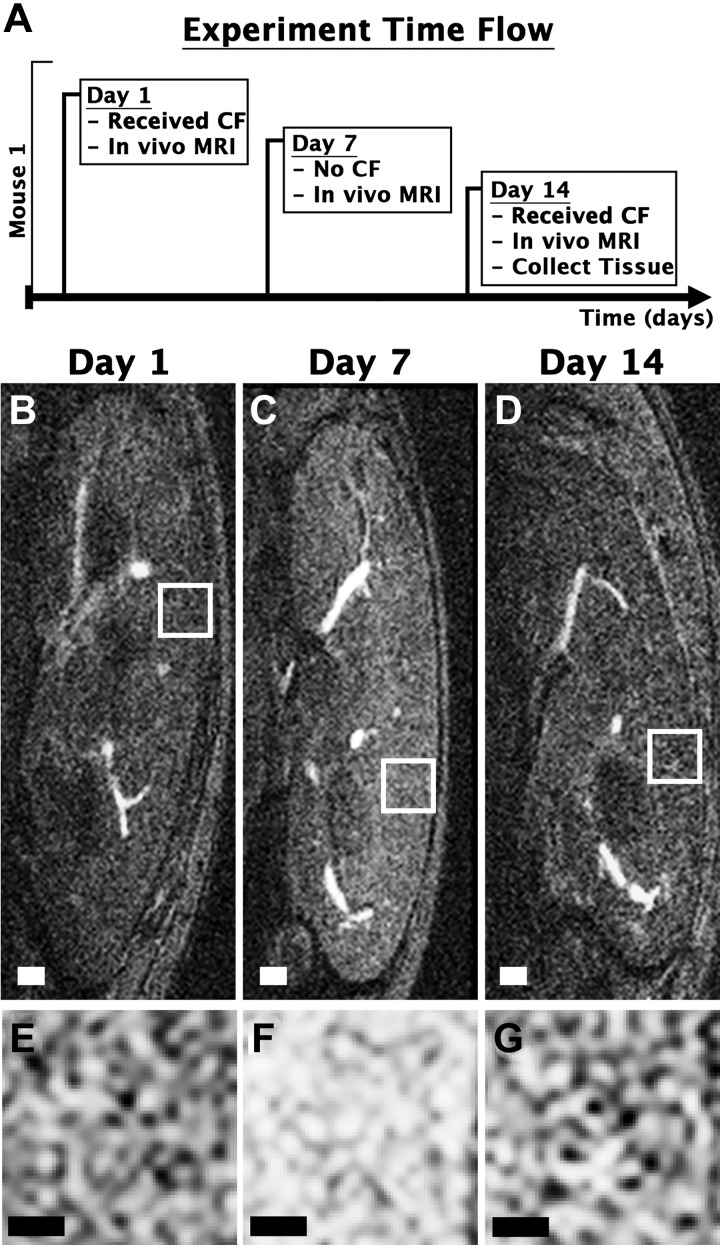

In vivo MRI revealed dark punctate spots in the kidney cortex of CF-injected mice. These spots were not present in the kidney of an uninjected control mouse (Fig. 1, A–J). Our custom software resolved individual glomeruli in vivo from CFE-MRI (Fig. 1, K, L, P, and Q). The WT mouse kidney was ~85% larger in volume than the Os/+ mouse kidney. WT mice had ~2.3 times more glomeruli than Os/+ mice (Fig. 2A). Glomerular profiles of signal magnitude appeared smooth in resampled images because of the multivariate interpolation method used here. Profiles measured in kidneys ex vivo were ~22% greater in height than those measured in vivo. In the mouse imaged after CF injection on days 1 and 14, glomerular labeling by CF in the kidney glomeruli was visible by CFE-MRI on both days (Fig. 3). Glomeruli were identified by our custom software in three dimensions. ROC analysis revealed an area under curve of 0.83 (Fig. 4, A and B). We estimated an average false discovery rate of 6.9% and average false negative rate of 5.1% for our custom software. There was no significant difference in aVglom calculated using two-dimensional or three-dimensional analysis on glomerulus size in vivo (α = 0.05, P = 0.98). Thus, we reported aVglom measured using two-dimensional analysis and similar to a previous study (1). The difference in Nglom measured at days 1 and 14 was ~3%. No glomerular labeling was visible in the kidney cortex on day 7 when the animal did not receive CF. B1 homogeneity of the custom RF coil was assessed, and all kidneys imaged were within the working area over which IGV measurements did not deviate >10% (Fig. 1O). High-resolution ex vivo MRI of the same mouse kidneys also exhibited dark punctate spots in the kidney cortex, consistent with previous work (Fig. 1, H, I, M, N, R, and S; see Ref. 2).

Fig. 1.

In vivo cationic ferritin (CF)-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (CFE-MRI) reveals individual glomeruli in mouse kidneys. Images from in vivo MRI of a kidney from a control (no CF administered) mouse (n = 1; A) and in vivo CFE-MRI of kidneys from a wild type (WT) mouse (n = 4; B) and a mouse with oligosyndactylism (Os/+; n = 4; C). D: schematic of the custom imaging setup with insert for the radiofrequency (RF) probe. Inset: RF probe circuit. E–G: each kidney was isolated in in vivo MR images, and signal magnitude was adjusted to obtain an approximately constant signal-to-noise ratio across the kidney. H and I: images from high-resolution ex vivo MRI on the same kidneys. A region of interest (ROI) inside each kidney cortex is magnified from in vivo (J–L) and ex vivo (M and N) MR images. O: the RF coil had a maximum distance of ~6 mm where measurements of glomerular volume varied by <10%. Separate glomeruli identified with custom software are overlain in randomly assigned color on ROIs from in vivo (P and Q) and ex vivo (R and S) MR images. Scale bars = 1 mm in A–C and E–I, 0.3 mm in J–N, 2 mm in O, and 0.3 mm in P–S.

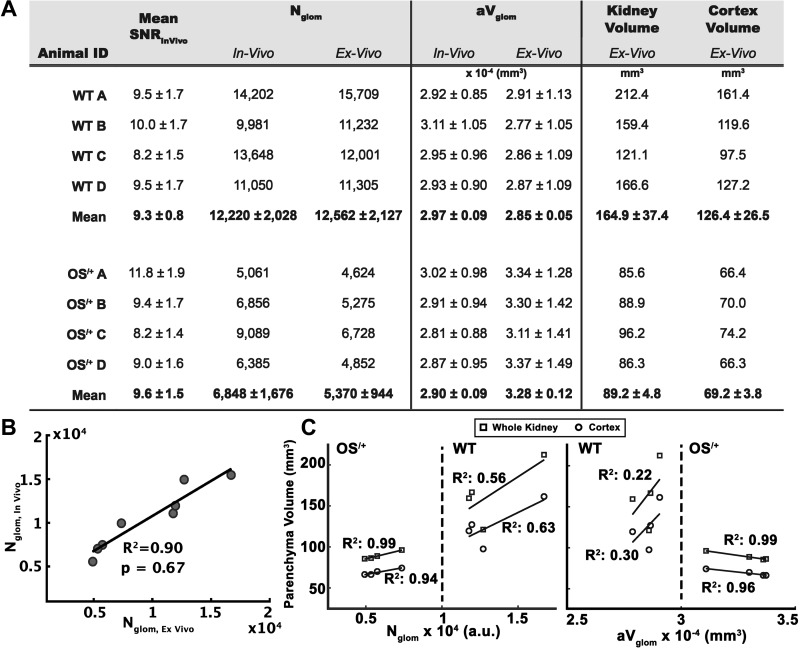

Fig. 2.

Values of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), glomerular number (Nglom), mean glomerulus volume (aVglom), and kidney and cortical volume measured from in vivo and ex vivo magnetic resonance (MR) images of mouse kidneys. A: measurements from in vivo and ex vivo MRI from wild-type (WT) mice and mice with oligosyndactylism (Os/+). The mean SNR is reported from in vivo MRI images. The difference in Nglom between WT and OS/+ mice was observed in both in vivo and ex vivo measurements. The difference in aVglom was observed in ex vivo MRI but not in vivo. Kidney and cortex volumes were measured in ex vivo MR images of mouse kidneys. B: in vivo and ex vivo measurements of Nglom from MRI (P = 0.67). C: correlation of Nglom and aVglom measured ex vivo with whole kidney and cortex volumes. Errors are reported using SDs.

Fig. 3.

In vivo cationic ferritin (CF)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CFE-MRI) on multiple days in the same wild-type (WT) mouse. A: timeline for the longitudinal experiment. On days 1 and 14, the animal received CF followed by MRI using T2* weighted imaging (B and D). Sagittal images of mouse kidneys from in vivo MRI are shown. C: on day 7, the animal did not receive CF and was imaged. E–G: magnified regions of the cortex. Glomerular enhancement was seen on days 1 and 14 but not on day 7. Measurements of glomerular number (Nglom) on days 1 and 14 differed by ~3%, within experimental error. Scale bars = 1.5 mm in B–D and 0.3 mm in E–G.

Fig. 4.

Distributions of glomerular volume from in vivo and ex vivo magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI) of mouse kidneys. A: a representative glomerulus profile shown in all three orthogonal perspectives. B: distribution of individual glomerular volume (IGV) is displayed using in vivo and ex vivo MRI (n = 4/cohort). Stars indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) between bins from wild-type (WT) mice and mice with oligosyndactylism (OS/+). Inset on bottom: receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the glomerular recognition algorithm. We estimated an average false discovery rate of 6.9% and average false negative rate of 5.1% for the glomerular recognition algorithm. C, top: representative MR images in the sagittal plane from the same kidney are shown with identified glomeruli color coded according to IGV. In ex vivo maps of IGV, the fraction of glomeruli in the largest volume bin (>6 × 10−4 mm3) was 10% greater in the Os/+ mouse compared with the WT mouse. C, bottom: mean distribution of the identified glomeruli in the IGV maps versus their distance to the edge of the kidney. Scale bars in C = 1 mm (in vivo) and 1 mm (ex vivo).

In vivo measurements of Nglom were compared with those obtained ex vivo (Fig. 2A). Mean values of Nglom measured in the WT cohort were 12,220 ± 2,028 and 12,562 ± 2,127 for in vivo and ex vivo experiments, respectively. Mean values of Nglom measured in the Os/+ cohort were 6,848 ± 1,676 and 5,370 ± 944 for in vivo and ex vivo experiments, respectively. There was no significant difference between in vivo and ex vivo measurements of Nglom (α = 0.05, PNglom,WT = 0.97, PNglom-OS/+ = 0.17). We also measured a linear regression for in vivo versus ex vivo measurements with a resulting R2 = 0.90 for all Nglom (Fig. 2B). Mean values of aVglom measured in the WT cohort were 2.97 ± 0.09 and 2.85 ± 0.05 × 10−4 mm3 for in vivo and ex vivo experiments, respectively. There was no significant difference between in vivo and ex vivo measurements of aVglom in WT mice (α = 0.05, PaVglom-WT = 0.47). Mean values of aVglom measured in the Os/+ cohort were 2.90 ± 0.09 and 3.28 ± 0.12 × 10−4 mm3 for in vivo and ex vivo experiments, respectively. There was a significant difference between in vivo and ex vivo measurements of aVglom in Os/+ mice (P < 0.01).

Values of Nglom and aVglom measured with ex vivo MRI were plotted against whole kidney volume and segmented cortical volume (Fig. 2C). In both WT and Os/+ mice, there was a positive correlation between Nglom and whole kidney volume (= 0.56, = 0.99) and between Nglom and segmented cortical volume ( = 0.63, = 0.94). There was a positive correlation between aVglom and volumes in WT mice ( = 0.22, = 0.30), but a negative correlation between aVglom and volumes in OS/+ mice ( = 0.99, = 0.66).

Mean IGV distributions from in vivo and ex vivo measurements in WT and Os/+ mice were compared (Fig. 4B). There was no significant difference in median IGV or in any of the overlapping bins of IGV distribution between WT and Os/+ in vivo (α = 0.05, P = 1.0). Median IGV differed by 11% between WT and Os/+ ex vivo (median, WT = 2.91 × 10−4 mm3; median, Os/+ = 3.24 × 10−4 mm3). Mean distributions were significantly different between strains in ex vivo data, with 61% of overlapping bins measured to be significantly different (P < 0.01). Glomeruli were separated into a low and high IGV group. The low IGV group included values up to the mean IGV measured in WT mice (low = 0.00–2.91 × 10−4 mm3). The high IGV range included all values over the mean IGV in WT mice (high = 2.91–10.00 × 10−4 mm3). There was no observed difference in the low or high IGV groups between WT and Os/+ mice in vivo (α = 0.05, P = 0.98). The fraction of glomeruli in ex vivo measurements of the low IGV group was ~20% larger in WT mice compared with Os/+ mice. The fraction of glomeruli in the high IGV group was ~12% less in WT mice compared with Os/+ mice ex vivo. This is consistent with previous reports of similar differences in the IGV distribution and larger aVglom in the Os/+ mouse with stereology (2, 21). MR images were randomly selected, and the identified glomeruli were overlaid and color coded to create spatial maps of IGV (Fig. 4C). We found no significant difference in the fraction of glomeruli in each bin of IGV values from randomly selected in vivo images of WT and Os/+ mouse kidneys (α = 0.05, P = 0.54). In similar randomly selected ex vivo images, the fraction of glomeruli in the bin with the largest IGV values was 10% higher in the Os/+ mice compared with WT mice. There was no significant correlation between IGV and distance to the edge of kidney in either WT or Os/+ mice (Fig. 4C, bottom).

Anti-ferritin IF revealed CF bound to the basement membrane in the capillary tuft of the glomerulus in a mouse that received CF and euthanized on the same day (Fig. 5). A similar distribution of CF was also was seen in the mouse that received CF on days 1 and 14. This is consistent with previous work showing the binding of CF on the GBM (8). There was no CF within the capillary tuft of the control mouse that did not receive CF.

Fig. 5.

Immunofluorescence (IF) of a mouse kidney labeled with cationic ferritin (CF) by intravenous injection on multiple days. Kidney tissue was stained for ferritin IF to examine at the distribution of CF. Nuclei were also visualized using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). A–D: kidney tissue of a mouse that received CF on day 1 and was also euthanized on day 1. A bright ribbon-like structure is visible along the tuft of the glomerulus. Below that is the kidney of a mouse that received CF on days 1 and 14 and was euthanized on day 14 (E–H). A similar ribbon-like structure is observed. I–L: kidney tissue of a mouse that did not receive CF. No CF immunolabeling is present. Scale bars = 20 μm in A–L.

DISCUSSION

We used CFE-MRI to detect and count glomeruli in the mouse kidney in vivo using a combination of custom hardware and software. We measured Nglom and aVglom in kidneys of healthy WT mice and Os/+ mice, a model of congenital renal hypoplasia leading to nephron reduction, and detected the difference in nephron number between the two strains. No significant difference in Nglom was detected between images acquired in vivo and ex vivo of the same kidney, indicating that CFE-MRI can robustly measure nephron endowment in vivo in both healthy mice and in mouse models of human disease. Nglom was also not significantly different from literature values from stereology in the same strains of mice (α = 0.05, P = 0.57; see Ref. 2). Furthermore, CFE-MRI can be used to obtain repeated measurements of Nglom over time. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a technique to identify and count glomeruli in the kidney of a living mouse.

We detected a lower aVglom in vivo compared with ex vivo for the same kidney in Os/+ mice. This discrepancy was unexpected because our previous work indicated larger aVglom in Os/+ mice ex vivo (2). One possible explanation is that the image resolution, on the order of the glomerulus size, may not be sufficient to detect the difference in vivo with the current protocol. The values of aVglom measured in vivo from three-dimensional analysis on glomerulus size were not significantly different than from two-dimensional analysis on glomerulus size, suggesting voxel resolution is an important factor for measuring aVglom. Another possibility is that a perfused glomerulus in vivo is indeed smaller in volume than a perfused fixed glomerulus ex vivo, and this difference is affected during tissue preparation for pathology and arises from the distensibility of the glomerulus (36). There was no correlation between glomerular size and location within the kidney in randomly sampled images. Mean glomerular size has been observed to be larger in juxtamedullary regions than in cortex in ex vivo samples, warranting further investigation (18, 26). Other approaches to resolve glomeruli against other soft tissue within the kidney by incorporating other pulse sequence designs, such as dynamic contrast enhanced imaging, with CFE-MRI and improving spatial resolution might resolve spatial differences in glomerular volume in future work. Also, future studies that coregister MRI with optical imaging of the same glomerulus in vivo and in relation to other morphology within the kidney should also explain this discrepancy.

Values of Nglom and aVglom were correlated with kidney volume and segmented cortical volume. There was a positive correlation between Nglom and volumes in both WT and Os/+ mice. There was a positive correlation between aVglom and volumes in WT mice but a negative correlation between aVglom and volumes in Os/+ mice. The difference in aVglom correlation between WT and Os/+ strains likely reflects the complex relationship of renal filtration with genetic factors, as also observed in humans (27).

Values of aVglom measured ex vivo were consistent with the values previously published in the same strain (2). However, future work will focus on improving the method to obtain aVglom and IGV measurements by CFE-MRI. Currently, an empirical method is used that samples intensity profiles of signal magnitude in identified glomeruli from images, and apparent glomerulus size is calculated using profile width. We have also used a semiautomated approach to measure aVglom in both rats and in human kidneys ex vivo using a novel blob detection algorithm (38, 39). These methods are reliable when calibrated to stereology (2, 3, 6). However, a theoretical approach to determine glomerulus size, taking into account the shape of the susceptibility gradient around the glomerulus, should enable an accurate method that does not require calibration. Such an approach is under development.

The advances in MRI hardware and optimization of software shown here enabled in vivo measurements of glomerular number and size in the mouse. The total time to acquire three-dimensional images in vivo was ~2 h. Reducing the image acquisition time will be an important factor for the repeated use of in vivo MRI in future studies. For example, acquisition time is directly proportional to TR, so a significant reduction in TR would similarly reduce the total time of image acquisition. Thus, TR could be reduced further while still achieving a T2* weighted image (6, 12). Also, the use of a T1-shortening agent, such as para-CF (13), would be useful in reducing total time of image acquisition since T1-weighted scans with CFE-MRI would use a reduced TR. Partial k-space acquisition or pulse sequence design could also reduce total imaging time. Finally, we used respiratory gating here to reduce the effects of motion during the scan, but there are several new acquisition techniques that allow for motion correction from the k-space data and omit the need to gate, which could reduce acquisition time by ~50% (30, 34). Another approach to reduce the image acquisition time is the improvement of hardware. For example, cryogenic RF coils provide a SNR gain of at least double compared with noncryogenic coils. Such advances in hardware could enable measurements with a single three-dimensional image or improve spatial resolution in vivo. With the combination of these techniques, we estimate total time for acquisition could be reduced to <30 min.

The routine use of MRI to measure glomerular number and size in vivo may strongly depend on MRI hardware and software, particularly in small rodent models such as mice. Factors such as gradient strength and RF technology can vary between institutions. For use in humans, challenges include regulatory hurdles and whole organ coverage with rapid acquisition. Our current scans at ~100 μm resolution in human kidneys take ~2.5 h. Further improvements to the imaging protocol should help reduce total scan time.

The ability to track changes in nephron number over time is a potentially valuable tool to investigate CKD. The present study suggests that this is possible. Although we have observed limited short- or long-term toxicity in mice receiving a single dose of CF (4, 11), the repeated systemic injection of cationic antigens may precipitate immune complex formation and glomerular injury (9, 28). This problem may eventually require recombinant CF tailored to longitudinal experiments. In a recent study to evaluate the potential toxicity of CF, mice were monitored for 3 wk after administration of either an MRI-detectable dose of CF or double that dose (high dose). Neither the CF nor high-dose CF groups had a change in renal function (by blood urea nitrogen or creatinine), kidney size, or histological structure of the kidney compared with control animals (11). We speculate that it is unlikely that CF binding causes changes in glomerular filtration because others have shown that disruption to the charge barrier within the GBM did not alter glomerular filtration (22). However, future work will include the measurement of glomerular filtration rate after CF administration in both healthy and diseased models.

While this work focused on resolving and measuring the mouse glomerulus, the advances in imaging seen here could facilitate research in other small structures in the kidney. Assessing tubular injury, for example, could benefit from improved resolution. Acute tubular necrosis can lead to acute kidney injury and is primarily diagnosed by measuring various metabolite concentrations in the blood. A tool to directly visualize and assess the tubule in conjunction with the glomerulus could be a useful tool in studying the development of acute kidney injury and CKD arising from tubular injury.

In summary, CFE-MRI can be used to measure nephron endowment in vivo in healthy mice and those with nephron reduction. This work provides a nondestructive framework for in vivo and longitudinal preclinical studies to understand the progression of kidney disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-DK-110622 (to K. M. Bennett and J. R. Charlton) and R01-DK-111861 (to K. M. Bennett and J. R. Charlton) and an American Society of Nephrology Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant (J. R. Charlton). This work used the Bruker ClinScan MRI in the Molecular Imaging Core, which was purchased with support from NIH Grant 1S10-RR-019911-01 and is supported by the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

DISCLOSURES

K. M. Bennett and J. R. Charlton own Sindri Technologies. K. M. Bennett owns Nephrodiagnostics. E.J. Baldelomar and K.M. Bennett own XN Biotechnologies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.J.B., J.R.C., and K.M.B. conceived and designed research; E.J.B., J.R.C., and K.A.d. performed experiments; E.J.B. and K.M.B. analyzed data; E.J.B., J.R.C., and K.M.B. interpreted results of experiments; E.J.B. prepared figures; E.J.B. drafted manuscript; E.J.B., J.R.C., and K.M.B. edited and revised manuscript; E.J.B., J.R.C., K.A.d., and K.M.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the molecular imaging core at the University of Virginia (UVa) and J. Roy for insights and technical assistance in imaging, along with J. Gatesman and the UVa veterinary staff. We also thank the School of Ocean and Earth Science Technology Machine Shop at the University of Hawai’i and M. Williamson for assistance in designing the custom imaging bed. We acknowledge S. C. Beeman, J. A. Ackerman, J. Neil, and members of the Biomedical Magnetic Research Laboratory at Washington University for constructive comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldelomar EJ, Charlton JR, Beeman SC, Bennett KM. Measuring rat kidney glomerular number and size in vivo with MRI. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 314: F399–F406, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00399.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldelomar EJ, Charlton JR, Beeman SC, Hann BD, Cullen-McEwen L, Pearl VM, Bertram JF, Wu T, Zhang M, Bennett KM. Phenotyping by magnetic resonance imaging nondestructively measures glomerular number and volume distribution in mice with and without nephron reduction. Kidney Int 89: 498–505, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beeman SC, Cullen-McEwen LA, Puelles VG, Zhang M, Wu T, Baldelomar EJ, Dowling J, Charlton JR, Forbes MS, Ng A, Wu QZ, Armitage JA, Egan GF, Bertram JF, Bennett KM. MRI-based glomerular morphology and pathology in whole human kidneys. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1381–F1390, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00092.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beeman SC, Georges JF, Bennett KM. Toxicity, biodistribution, and ex vivo MRI detection of intravenously injected cationized ferritin. Magn Reson Med 69: 853–861, 2013. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeman SC, Mandarino LJ, Georges JF, Bennett KM. Cationized ferritin as a magnetic resonance imaging probe to detect microstructural changes in a rat model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Magn Reson Med 70: 1728–1738, 2013. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeman SC, Zhang M, Gubhaju L, Wu T, Bertram JF, Frakes DH, Cherry BR, Bennett KM. Measuring glomerular number and size in perfused kidneys using MRI. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F1454–F1457, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00044.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett KM, Bertram JF, Beeman SC, Gretz N. The emerging role of MRI in quantitative renal glomerular morphology. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F1252–F1257, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00714.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett KM, Zhou H, Sumner JP, Dodd SJ, Bouraoud N, Doi K, Star RA, Koretsky AP. MRI of the basement membrane using charged nanoparticles as contrast agents. Magn Reson Med 60: 564–574, 2008. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Border WA, Ward HJ, Kamil ES, Cohen AH. Induction of membranous nephropathy in rabbits by administration of an exogenous cationic antigen. J Clin Invest 69: 451–461, 1982. doi: 10.1172/JCI110469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S. Glomeruli and blood pressure. less of one, more the other? Am J Hypertens 1: 335–347, 1988. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlton JR, Pearl VM, Denotti AR, Lee JB, Swaminathan S, Scindia YM, Charlton NP, Baldelomar EJ, Beeman SC, Bennett KM. Biocompatibility of ferritin-based nanoparticles as targeted MRI contrast agents. Nanomedicine (Lond) 12: 1735–1745, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavhan GB, Babyn PS, Thomas B, Shroff MM, Haacke EM. Principles, techniques, and applications of T2*-based MR imaging and its special applications. Radiographics 29: 1433–1449, 2009. doi: 10.1148/rg.295095034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clavijo Jordan MV, Beeman SC, Baldelomar EJ, Bennett KM. Disruptive chemical doping in a ferritin-based iron oxide nanoparticle to decrease r2 and enhance detection with T1-weighted MRI. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 9: 323–332, 2014. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coladonato J, Klassen P, Owen WFJ Jr. Perception versus reality of the burden of chronic kidney disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1686–1688, 2002. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000019646.05890.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Chavers B, Gilbertson D, Herzog C, Ishani A, Johansen K, Kasiske BL, Kutner N, Liu J, St Peter W, Guo H, Hu Y, Kats A, Li S, Li S, Maloney J, Roberts T, Skeans M, Snyder J, Solid C, Thompson B, Weinhandl E, Xiong H, Yusuf A, Zaun D, Arko C, Chen S-C, Daniels F, Ebben J, Frazier E, Johnson R, Sheets D, Wang X, Forrest B, Berrini D, Constantini E, Everson S, Eggers P, Agodoa L. US Renal Data System 2013 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis Suppl 63: A7, 2014. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denic A, Mathew J, Lerman LO, Lieske JC, Larson JJ, Alexander MP, Poggio E, Glassock RJ, Rule AD. Single-nephron glomerular filtration rate in healthy adults. N Engl J Med 376: 2349–2357, 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doty FD, Entzminger G, Kulkarni J, Pamarthy K, Staab JP. Radio frequency coil technology for small-animal MRI. NMR Biomed 20: 304–325, 2007. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elsherbiny HE, Alexander MP, Kremers WK, Park WD, Poggio ED, Prieto M, Lieske JC, Rule AD. Nephron hypertrophy and glomerulosclerosis and their association with kidney function and risk factors among living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1892–1902, 2014. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02560314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falconer DS, Latsyzewskia M, Isaacson JH. Diabetes insipidus associated with oligosyndactyly in the mouse. Genet Res 5: 473–488, 1964. doi: 10.1017/S0016672300034911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grüneberg H. Genetical studies on the skeleton of the mouse XVIII. Three genes for syndactylism. J Genet 54: 113–145, 1956. doi: 10.1007/BF02981706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hann BD, Baldelomar EJ, Charlton JR, Bennett KM. Measuring the intrarenal distribution of glomerular volumes from histological sections. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F1328–F1336, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00382.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey SJ, Jarad G, Cunningham J, Rops AL, van der Vlag J, Berden JH, Moeller MJ, Holzman LB, Burgess RW, Miner JH. Disruption of glomerular basement membrane charge through podocyte-specific mutation of agrin does not alter glomerular permselectivity. Am J Pathol 171: 139–152, 2007. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heilmann M, Neudecker S, Wolf I, Gubhaju L, Sticht C, Schock-Kusch D, Kriz W, Bertram JF, Schad LR, Gretz N. Quantification of glomerular number and size distribution in normal rat kidneys using magnetic resonance imaging. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 100–107, 2012. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoy WE, Douglas-Denton RN, Hughson MD, Cass A, Johnson K, Bertram JF. A stereological study of glomerular number and volume: preliminary findings in a multiracial study of kidneys at autopsy. Kidney Int Suppl 63: S31–S37, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newbold KM, Sandison A, Howie AJ. Comparison of size of juxtamedullary and outer cortical glomeruli in normal adult kidney. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 420: 127–129, 1992. doi: 10.1007/BF02358803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyengaard JR, Bendtsen TF. Glomerular number and size in relation to age, kidney weight, and body surface in normal man. Anat Rec 232: 194–201, 1992. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092320205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oite T, Shimizu F, Suzuki Y, Vogt A. Ultramicroscopic localization of cationized antigen in the glomerular basement membrane in the course of active, in situ immune complex glomerulonephritis. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol 48: 107–118, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF02890120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palatini P. Glomerular hyperfiltration: a marker of early renal damage in pre-diabetes and pre-hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1708–1714, 2012. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pipe JG. Motion correction with PROPELLER MRI: application to head motion and free-breathing cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med 42: 963–969, 1999. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandilands EA, Dhaun N, Dear JW, Webb DJ. Measurement of renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 76: 504–515, 2013. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnaper HW. Remnant nephron physiology and the progression of chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 29: 193–202, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2494-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snyder S, Pendergraph B. Detection and evaluation of chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician 72: 1723–1732, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song H, Ruan D, Liu W, Stenger VA, Pohmann R, Fernández-Seara MA, Nair T, Jung S, Luo J, Motai Y, Ma J, Hazle JD, Gach HM. Respiratory motion prediction and prospective correction for free-breathing arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI of the kidneys. Med Phys 44: 962–973, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mp.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tadashi Y. Renal and Urinary Proteomics: Methods and Protocols. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyss HM, Henderson JM, Byfield FJ, Bruggeman LA, Ding Y, Huang C, Suh JH, Franke T, Mele E, Pollak MR, Miner JH, Janmey PA, Weitz DA, Miller RT. Biophysical properties of normal and diseased renal glomeruli. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C397–C405, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00438.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zalups RK. The Os/+ mouse: a genetic animal model of reduced renal mass. Am J Physiol 264: F53–F60, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.1.F53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang M, Wu T, Beeman SC, Cullen-McEwen L, Bertram JF, Charlton JR, Baldelomar E, Bennett KM. Efficient small blob detection based on local convexity, intensity and shape information. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 35: 1127–1137, 2016. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2509463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Wu T, Bennett KM. Small blob identification in medical images using regional features from optimum scale. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 62: 1051–1062, 2015. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2360154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]