Abstract

We sought to examine the effect of varying chemoreflex stress on sympathetic neural recruitment strategies during end-expiratory apnea. We hypothesized that increases in the firing frequency and probability of low-threshold axons at the asphyxic “break point” would be exaggerated during hypoxia and attenuated during hyperoxia. Multiunit muscle sympathetic nervous system activity (MSNA) (peroneal nerve microneurography) was measured in 10 healthy male subjects (31 ± 2 yr, 25 ± 1 kg/m2). Individuals completed maximal voluntary end-expiratory apnea under normoxic, hypoxic (inspired O2 fraction: 0.17 ± 0.01), and hyperoxic (inspired O2 fraction: 0.92 ± 0.03) conditions. Action potential (AP) patterns were examined from the filtered raw signal with wavelet-based methodology. Multiunit MSNA was increased (P ≤ 0.05) during normoxic apnea, because of an increase in the frequency and incidence of AP spikes (243 ± 75 to 519 ± 134 APs/min, P = 0.048; 412 ± 133 to 733 ± 185 APs/100 heartbeats, P = 0.02). Multiunit MSNA increased from baseline (P < 0.01) during hypoxic apnea, which was due to an increase in the frequency and incidence of APs (192 ± 59 to 952 ± 266 APs/min, P < 0.01; 326 ± 89 to 1,212 ± 327 APs/100 heartbeats, P < 0.01). Hypoxic apnea also resulted in an increase in the probability of a particular AP cluster firing more than once per burst (P < 0.01). Hyperoxia attenuated any increase in MSNA with apnea, such that no changes in multiunit MSNA or frequency or incidence of AP spikes were observed (P > 0.05). We conclude that increases in frequency and incidence of APs during apnea are potentiated during hypoxia and suppressed when individuals are hyperoxic, highlighting the important impact of chemoreflex stress in AP discharge patterns. The results may have implications for neural control of the circulation in recreational activities and/or clinical conditions prone to apnea.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Our results demonstrate that, compared with normoxic end-expiratory apnea, hypoxic apnea increases the frequency and incidence of action potential spikes as well as the probability of multiple firing. We further show that this response is suppressed when individuals are hyperoxic. These data highlight the potentially important role of chemoreflex stress in neural firing and recruitment and may have implications for neural control of the circulation in recreational and/or clinical conditions prone to apnea.

Keywords: breath hold, carotid body, hyperoxia, hypoxia, microneurography

INTRODUCTION

Voluntary end-expiratory apnea results in a gradual increase in sympathetic nervous system activity until the asphyxic “break point,” the time at which apnea is terminated and breathing is reinitiated. Apnea duration is shortest during hypoxia and is significantly increased during hyperoxia (Bain et al. 2017; Engel et al. 1946; Hardy et al. 1994; Klocke and Rahn 1959); this is in agreement with studies attributing the asphyxic break point to chemical stimuli (e.g., decreased oxygen, elevated carbon dioxide) (Ferris et al. 1946; Findley et al. 1983; Hardy et al. 1994). Along these same lines, increases in multiunit muscle sympathetic nervous system activity (MSNA) in response to voluntary apnea are increased by hypoxia and attenuated by hyperoxia (Hardy et al. 1994; Leuenberger et al. 2001; Morgan et al. 1993). Whereas various factors influence the break point for voluntary apnea (Godfrey and Campbell 1968; Lin et al. 1974; Parkes 2006), the observed increase in MSNA during voluntary apnea is thought to be the result of 1) chemoreflex stimulation (Badrov et al. 2017; Halliwill et al. 2003; Halliwill and Minson 2002; Morgan et al. 1993; Saito et al. 1988; Somers et al. 1989a), 2) lack of ventilatory restraint on sympathetic outflow (Badrov et al. 2017; Dempsey et al. 2002; Eckberg et al. 1985; Fatouleh and Macefield 2011; Hagbarth and Vallbo 1968; Macefield and Wallin 1995a, 1995b; Seals et al. 1990, 1993; Somers et al. 1989b; Steinback et al. 2010), and 3) increased central drive to breathe (Hardy et al. 1994; Somers et al. 1989b; Steinback et al. 2010).

It has been known for some time that average, multiunit sympathetic activity is increased at end-apnea; however, the absolute strength and/or intensity of neuronal factors contributing to this response (including number of active neurons, mean firing probability, and likelihood of multiple firing) have only more recently been explored. Such analyses provide a more sensitive measure of central sympathetic drive as well as the ability to directly explore contributing mechanisms. As a result of initial experiments, we now know that increases in sympathetic activity at end-apnea are the result of 1) increases in firing frequency and probability of previously recruited low-threshold axons, 2) recruitment of latent subpopulations of higher-threshold and faster-conducting axons (Badrov et al. 2015, 2017; Breskovic et al. 2011; Steinback et al. 2010), and 3) acute modification of synaptic delays and/or central processing times (Macefield and Wallin 1995b, 1999). This pattern has important implications for neural control of the circulation, given that the goal of the sympathetic response to apnea is peripheral vasoconstriction and distribution of blood flow away from the periphery to preserve oxygen to the brain (Heistad et al. 1968; Heusser et al. 2009; Shamsuzzaman et al. 2014).

With this information in mind, one would expect the presence and/or absence of hypoxemia alone or combined with apnea to be a main contributor to neural firing and recruitment, including frequency, probability, and within-burst firing. Unfortunately, the majority of previous work was conducted in the setting of “severe” chemoreflex stress (apnea combined with rebreathe, resulting in reduction in end-tidal Po2 and increase in end-tidal Pco2) (Badrov et al. 2015, 2017), making it difficult to determine the independent effect of hypoxemia. Furthermore, previous studies did not directly examine single versus multiple within-burst firing. Data from single-unit recordings suggest that firing probabilities are augmented in clinical conditions prone to hypoxemia (i.e., sleep apnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Ashley et al. 2010; Elam et al. 2003), including a shift toward multiple within-burst firing (Elam and Macefield 2001). Such data have important physiological implications, given that greater within-burst firing likely contributes significantly to the level of neurally mediated vasoconstriction (Briant et al. 2015). Furthermore, attenuation of nocturnal hypoxemia has been shown to reduce multiunit MSNA in patients with sleep apnea (Narkiewicz et al. 1999); however, the effect of attenuated chemoreflex stress in neural firing patterns has not been directly examined.

Taken together, a number of key gaps in knowledge exist, including whether neural firing and recruitment strategies can be modified by hypoxia and/or hyperoxia, how these patterns are modified, and their potential impact on the peripheral vasculature. Such data would improve the understanding of key neurovascular control mechanisms important in the human circulatory response to environmental stressors, such as apnea, altitude, and/or exercise. With this information in mind, we sought to examine the influences of chemoreceptor stimuli on sympathetic neural firing and recruitment strategies during voluntary end-expiratory apnea. In light of previous observations, we hypothesized that end-expiratory apnea would result in increased firing frequency, probability, and within-burst firing of low-threshold axons as well as recruitment of latent subpopulations of higher-threshold and faster-conducting axons at the asphyxic break point and that this response would be 1) exaggerated during hypoxia and 2) attenuated during hyperoxia.

METHODS

Research subjects.

All subjects were male, between 18 and 45 yr of age, healthy (no acute or chronic conditions), and nonsmokers with a body mass index ≤ 30 kg/m2 and not taking any medications. All experiments were performed in the Clinical Research and Trials Unit at the Mayo Clinic. Studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Mayo Clinic and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. On a screening visit, each subject gave written informed consent, followed by a review of medical history and a brief physical exam that included baseline measurements of height, weight, blood pressure, and heart rate. Data unrelated to the present hypotheses from a subset of the participants were published previously (Limberg et al. 2018).

Instrumentation.

On the study day, subjects arrived at the laboratory after a 4-h fast and after abstaining from exercise, caffeine, and alcohol for at least 24 h. Subjects were semirecumbent and were instrumented with a three-lead electrocardiogram to measure heart rate (Cardiocap/5; Datex-Ohmeda) and a nose clip-mouthpiece connected to a turbine for measurements of respiratory rate and tidal volume (Universal Ventilation Meter; Vacumetrics). A 20-gauge, 5-cm catheter was placed in the brachial artery under aseptic conditions after local anesthesia (2% lidocaine) to measure arterial blood pressure and blood gases [arterial partial pressure of O2 (), arterial partial pressure of CO2 ()]. Blood pressures reported in Tables 1–3 were acquired from the brachial arterial catheter; thus it is important to acknowledge the potential for underdamping/resonance with the use of an arterial catheter, which can cause blood pressure to read artificially high (Romagnoli et al. 2011, 2014).

Table 1.

Cardiorespiratory and neural responses to normoxic end-expiratory apnea

| Normoxic Baseline | Normoxic Apnea | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | 63 ± 3 | 70 ± 3 | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 141 ± 3 | 156 ± 5 | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 77 ± 2 | 93 ± 3 | <0.01 |

| Mean blood pressure, mmHg | 97 ± 2 | 114 ± 3 | <0.01 |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 98 ± 0 | ||

| , mmHg | 108 ± 5 | ||

| 2, mmHg | 40 ± 1 | ||

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 11 ± 1 | ||

| Tidal volume, L/breath | 0.77 ± 0.22 | ||

| Minute ventilation, mL/min | 7.5 ± 1.7 | ||

| Burst frequency, bursts/min | 24 ± 3 | 35 ± 3 | 0.051 |

| Burst incidence, bursts/100 heartbeats | 39 ± 5 | 52 ± 4 | 0.050 |

| Mean burst area, AU/min | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 0.02 |

| AP frequency, APs/min | 243 ± 75 | 519 ± 134 | 0.048 |

| AP incidence, APs/burst | 9 ± 2 | 13 ± 3 | 0.02 |

| AP incidence, APs/100 heartbeats | 412 ± 133 | 773 ± 185 | 0.04 |

| Mean cluster incidence, clusters/burst | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 0.03 |

| Max cluster incidence, clusters/burst | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 1.00 |

| Max cluster number | 12.2 ± 1.6 | 12.9 ± 2.0 | 0.55 |

| Data duration, s | 106 ± 7 | 17 ± 2 | <0.01 |

Data are reported as means ± SE for n = 10 subjects [n = 9 for arterial partial pressure of O2 (), arterial partial pressure of CO2 ()]. AP, action potential; AU, arbitrary units; , arterial O2 saturation from pulse oximetry. Data were analyzed with a 1-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. If not normally distributed, a Friedman repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks was conducted. Pairwise multiple comparisons were done with the Holm–Sidak method. Bold type signifies statistical significance.

Table 3.

Cardiorespiratory and neural responses to hyperoxic end-expiratory apnea

| Normoxic Baseline | Hyperoxic Baseline | Hyperoxic Apnea | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | 64 ± 2 | 63 ± 2 | 67 ± 5 | 0.53 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 145 ± 4 | 146 ± 4 | 157 ± 6*† | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78 ± 2 | 79 ± 3 | 89 ± 3*† | <0.01 |

| Mean blood pressure, mmHg | 100 ± 3 | 101 ± 3 | 113 ± 4*† | <0.01 |

| Oxygen saturation (% ) | 99 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 | 0.07 | |

| , mmHg | 110 ± 5 | 444 ± 19* | <0.01 | |

| , mmHg) | 38 ± 1 | 36 ± 2* | 0.03 | |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 11 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 0.17 | |

| Tidal volume, L/breath | 0.75 ± 0.18 | 0.80 ± 0.15 | 0.47 | |

| Minute ventilation, mL/min | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 8.8 ± 1.3* | 0.048 | |

| Burst frequency, bursts/min | 24 ± 4 | 21 ± 2 | 28 ± 5 | 0.14 |

| Burst incidence, bursts/100 heartbeats | 38 ± 6 | 33 ± 3 | 47 ± 8 | 0.12 |

| Mean burst area, AU/min | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.93 |

| AP frequency, APs/min | 155 ± 35 | 155 ± 30 | 253 ± 71 | 0.12 |

| AP incidence, APs/burst | 6 ± 1 | 8 ± 2 | 8 ± 1 | 0.18 |

| AP incidence, APs/100 heartbeats | 249 ± 61 | 258 ± 55 | 502 ± 188 | 0.28 |

| Mean cluster incidence, clusters/burst | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 0.57 |

| Max cluster incidence, clusters/burst | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 1.3 | 0.78 |

| Max cluster number | 13.2 ± 1.7 | 11.9 ± 0.9 | 11.2 ± 2.2 | 0.31 |

| Data duration, s | 107 ± 9 | 103 ± 9 | 32 ± 11* | 0.01 |

Data are reported as means ± SE for n = 9 subjects. AP, action potential; AU, arbitrary units; , arterial O2 saturation from pulse oximetry. Data were analyzed with a 1-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. If not normally distributed, a Friedman repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks was conducted. Pairwise comparisons were done with the Holm–Sidak method. Bold type signifies statistical significance.

P < 0.05 vs. normoxia;

P < 0.05 vs. hyperoxia.

Resting MSNA was recorded with the technique of microneurography (Salmanpour et al. 2010; Vallbo et al. 1979). Multiunit MSNA was recorded with a 2.0 ± 0.4-MΩ impedance tungsten microelectrode (200-µm diameter) tapering to 1–5 µm at the uninsulated tip (FHC, Bowdoin, ME). The microelectrode was placed percutaneously into the peroneal nerve posterior to the fibular head under direct two-dimensional live ultrasound guidance using a 12- to 15-MHz linear probe (Curry and Charkoudian 2011). A reference electrode was positioned subcutaneously ~4 cm from the recording electrode. The recorded signal was amplified 80,000-fold, band-pass filtered (700–2,000 Hz), rectified, and integrated (resistance-capacitance integrator circuit, time constant 0.1 s) by a nerve-traffic analyzer (662C-3; Bioengineering, University of Iowa). Sympathetic bursts in the integrated neurogram were identified with a custom-manufactured automated analysis program (Salmanpour et al. 2010). Multiunit MSNA is reported as bursts per minute (burst frequency), bursts per 100 heartbeats (burst incidence), and mean burst area (arbitrary units per minute).

Action potential detection and analysis.

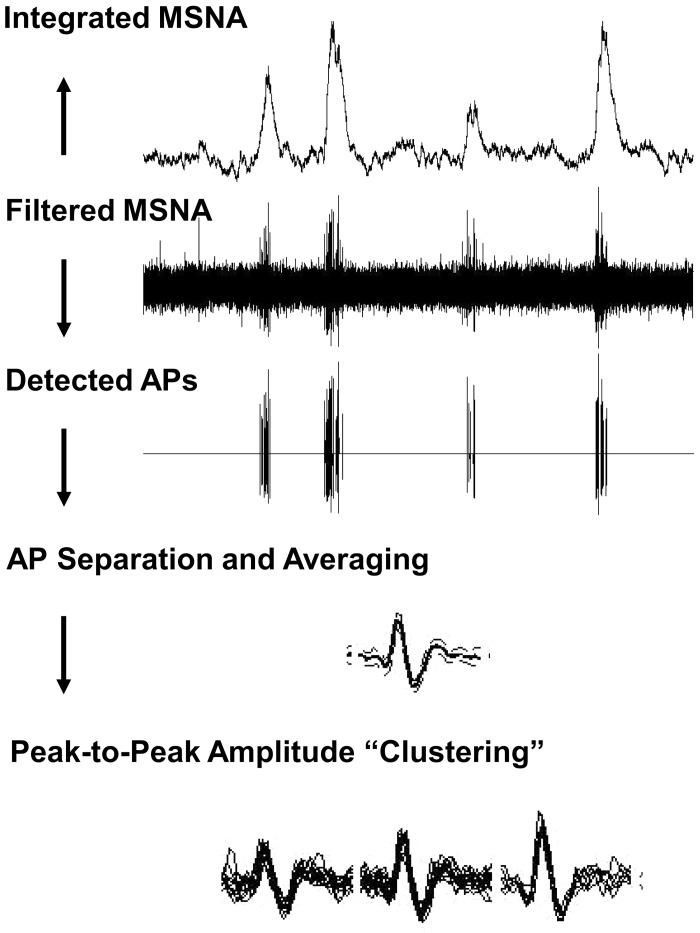

Action potential (AP) patterns were detected and extracted with wavelet-based methodology on the raw, band-pass-filtered neurogram with techniques developed in the laboratory of J. K. Shoemaker (Salmanpour et al. 2010). See Fig. 1 for visual depiction of the methodology.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of action potential (AP) detection and classification. MSNA, muscle sympathetic nerve activity. Figure adapted from Badrov et al. (2015) with permission.

As described previously (Limberg et al. 2018), a continuous wavelet transform using a “mother wavelet” with the same morphology as a physiological postganglionic sympathetic AP was used for AP detection. A continuous wavelet transform with the matched mother wavelet was applied to the filtered MSNA signal to provide a wavelet coefficient (i.e., resemblance index) between the AP of interest and the mother wavelet such that the resemblance index was largest in the presence of APs and negligible when applied to noise. Wavelet coefficients related to APs and noise were separated on the basis of threshold analysis. Nonoverlapping APs were grouped into separate clusters on the basis of their morphology with a 32-point matching model (32-point k-means). Extracted APs were ordered on the basis of peak-to-peak amplitude, and histogram analysis was performed to separate APs into amplitude-based clusters based on Scott’s rule (Scott 1979) (Fig. 1).

The number of total clusters (i.e., bins or groups of APs with similar peak-to-peak amplitudes) in the neurogram varied within maneuvers. Therefore, bin characteristics (minimum histogram bin width, maximum bin center, and total number of bins) were normalized within each individual during a given trial (normoxia, hypoxia, hyperoxia) to ensure that corresponding clusters at baseline and during apnea contained APs with similar peak-to-peak amplitudes.

AP data are reported as AP frequency (number of APs per minute), AP incidence (number of APs per 100 heartbeats), and mean AP content per integrated burst; these measures are indicative of the number of efferent postganglionic sympathetic neurons active within a specific frame of time. Data are further reported as the number of total clusters detected (max cluster number), the average number of active clusters per integrated burst (mean clusters/burst), and the maximum number of active clusters per integrated burst (max clusters/burst). The presence of a new cluster (i.e., increase in cluster number) represents recruitment of additional populations of APs during a particular trial that were not present at baseline.

Probability distributions were constructed to evaluate the firing probability of each sympathetic AP cluster at baseline and during apnea (i.e., Fig. 3, A and B, Fig. 4, A and B, Fig. 5, A and B). Because the number of total clusters varied by individual, normalization procedures were completed with methods published previously (Badrov et al. 2015). Briefly, APs were normalized to the largest detected cluster, which was given a value of 100%. Each cluster was placed into 1 of 10 equally sized bins containing a 10% range of the largest detected cluster (i.e., 0–9.9% of largest detected cluster). The number of times a normalized AP cluster bin fired was then divided by the total number of bursts that occurred in a given condition and multiplied by 100 to give a percentage. A probability of 100% indicates that clusters within the bin fired in every integrated burst. A probability <100% indicates that clusters within the bin were not active in every burst.

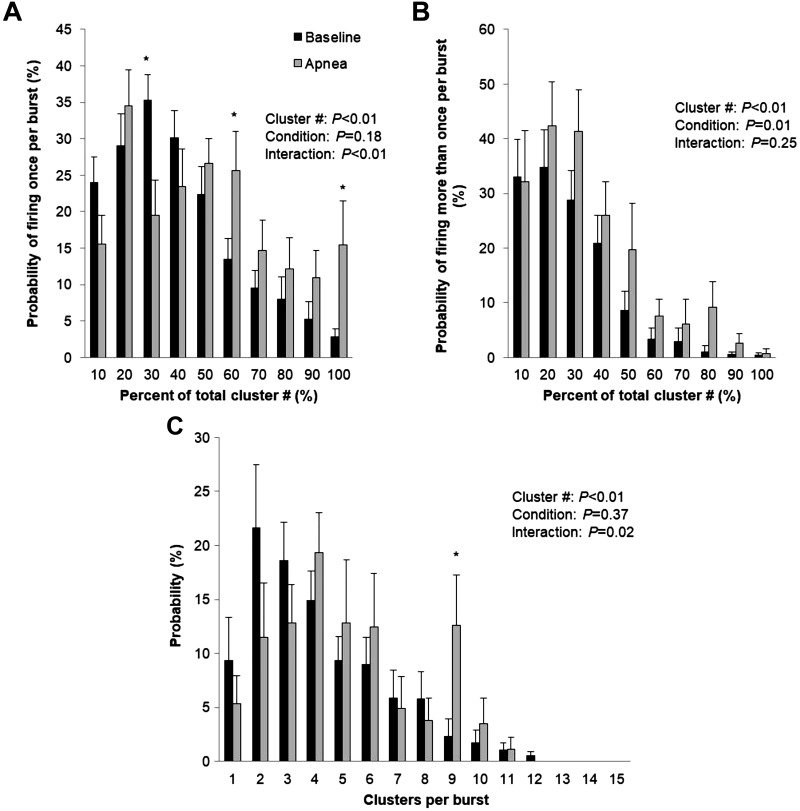

Fig. 3.

Sympathetic responses to normoxic apnea. Data are reported as means ± SE for n = 10 subjects. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline. Data were analyzed by using a 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA to determine the main effect of relative cluster size (10–100% of total clusters) and condition (baseline, apnea) and the interaction of cluster size and condition. A: probability of a relative cluster (10–100% of total clusters) firing once per integrated muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) burst. B: probability of a relative cluster (10–100% of total clusters) firing more than once per integrated MSNA burst. C: probability of multiple clusters per integrated MSNA burst.

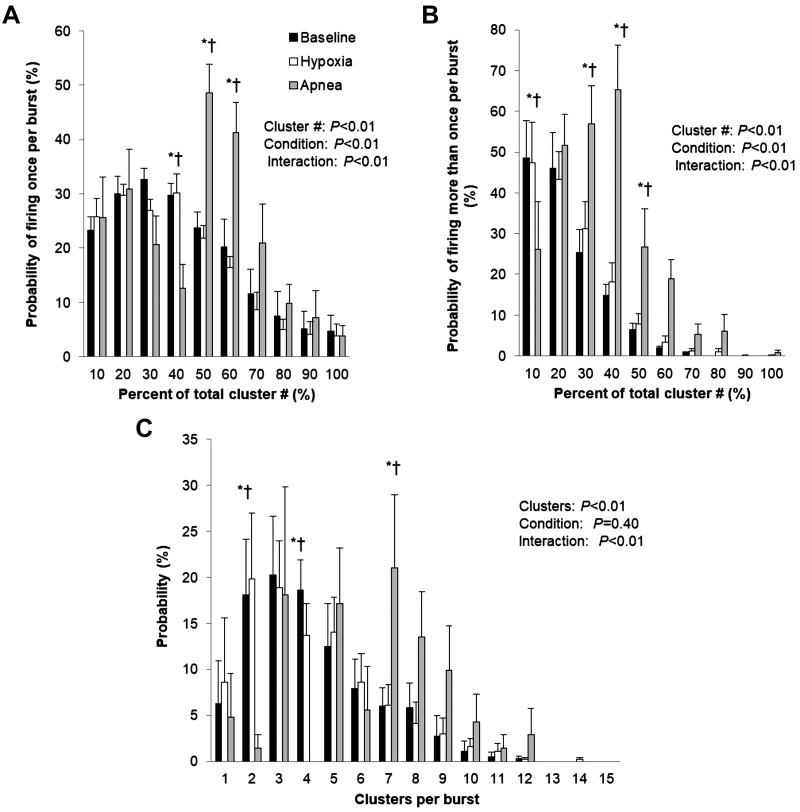

Fig. 4.

Sympathetic responses to hypoxic apnea. Data are reported as means ± SE for n = 7 subjects. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline; †P < 0.05 vs. hypoxia. Data were analyzed by using a 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA to determine the main effect of relative cluster size (10–100% of total clusters) and condition (baseline, hypoxia, apnea) and the interaction of cluster and condition. A: probability of a relative cluster (10–100% of total clusters) firing once per integrated muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) burst. B: probability of a relative cluster (10–100% of total clusters) firing more than once per integrated MSNA burst. C: probability of multiple clusters per integrated MSNA burst.

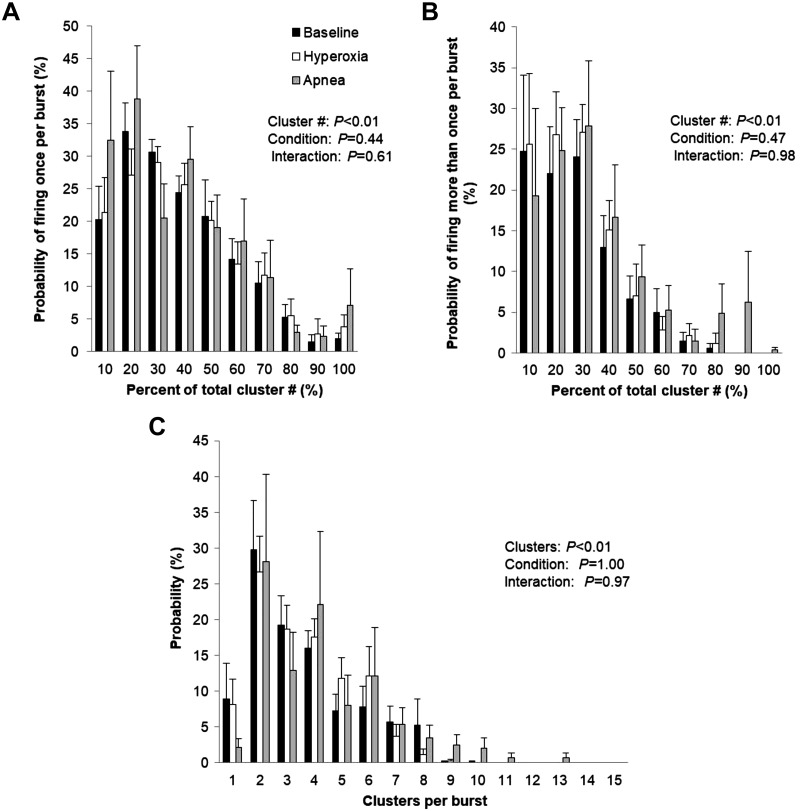

Fig. 5.

Sympathetic responses to hyperoxic apnea. Data are reported as means ± SE for n = 9 subjects. Data were analyzed by using a 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA to determine the main effect of relative cluster size (10–100% of total clusters) and condition (baseline, hyperoxia, apnea) and the interaction of cluster and condition. A: probability of a relative cluster (10–100% of total clusters) firing once per integrated muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) burst. B: probability of a relative cluster (10–100% of total clusters) firing more than once per integrated MSNA burst. C: probability of multiple clusters per integrated MSNA burst.

Acute gas exposure.

A 3-liter meteorological balloon served as a volume reservoir, and arterial blood gases (, ) and inspired/expired oxygen and carbon dioxide (capnography; Cardiocap/5; Datex-Ohmeda) were measured throughout the exposure. Arterial blood gas samples were analyzed immediately with an automatic blood gas analyzer (Radiometer ABL700; Westlake, OH). To begin, subjects breathed room air (: 108 ± 5 mmHg; : 40 ± 1 mmHg) through a mouthpiece connected to a nonrebreathing valve. During the hyperoxia trials, subjects were quietly switched to 100% oxygen (inspired O2 fraction: 0.92 ± 0.03; : 444 ± 19 mmHg; : 36 ± 2 mmHg). Hypoxic conditions were poikilocapnic, and hypoxemia was achieved by titrating inspired oxygen levels with a gas blender (inspired O2 fraction: 0.17 ± 0.01) to achieve an oxygen saturation of ~85% (arterial O2 saturation from pulse oximetry: 82 ± 1%; : 50 ± 4 mmHg; : 36 ± 2 mmHg). Maximal end-expiratory apneas were completed after a minimum of 5 min of quiet, resting normoxic, hyperoxic, or hypoxic breathing. Subjects were coached to hold apnea at functional residual volume and were instructed to avoid Müller or Valsalva maneuvers. Trials were randomized and separated by a minimum of 15 min of quiet, normoxic rest.

Data analysis.

Data were recorded at 10,000 Hz with a computer data acquisition system (PowerLab; AD Instruments) and stored for off-line analysis (Salmanpour et al. 2010). Data were analyzed over the baseline period (normoxic, hypoxic, hyperoxic) immediately before apnea and during the second half of maximal voluntary end-expiratory apnea, reflecting the time of highest MSNA (Hardy et al. 1994). Importantly, data duration has been shown previously to be unrelated to the total cluster response observed (Badrov et al. 2016) and thus is unlikely to impact conclusions. Statistical analyses were conducted with SigmaPlot version 14.0 (Systat Software). Data presented in Tables 1–3 were analyzed with a one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the main effect of condition (baseline, gas, apnea) on main outcome variables. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. If not normally distributed, a Friedman repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks was conducted. Pairwise comparisons were done with the Holm–Sidak method. Data presented in Figs. 3–5 were analyzed with a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA to determine the main effect of relative cluster size (10–100% of total clusters), condition (baseline, gas, apnea), and the interaction of cluster and condition. Pairwise comparisons were done with the Holm–Sidak method. All data are presented as means ± SE. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Subject demographics.

Ten male subjects (31 ± 2 yr, 180 ± 2 cm, 81 ± 3 kg, 25 ± 1 kg/m2) participated in the present study. Of the 10 individuals who completed the normoxia protocol, 9 individuals completed the hyperoxia protocol (30 ± 2 yr, 180 ± 2 cm, 80 ± 3 kg, 25 ± 1 kg/m2) and 7 individuals completed the hypoxia protocol (32 ± 2 yr, 177 ± 2 cm, 81 ± 4 kg, 26 ± 1 kg/m2) because of loss of stable MSNA signal.

Normoxia.

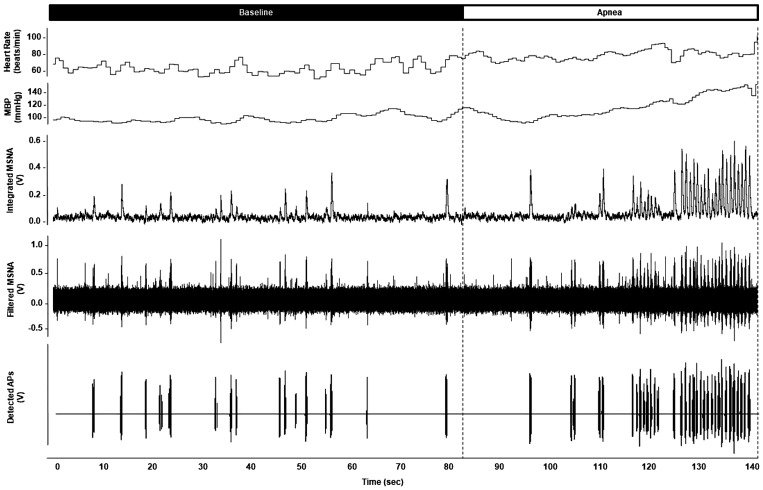

See Fig. 2 for representative data. Maximal end-expiratory apneas during normoxic conditions were 32.1 ± 3.8 s in length and resulted in a nadir oxygen saturation of 95 ± 1%. Significant increases in blood pressure (P < 0.01) were observed, with a trend for higher heart rate at end-apnea (P = 0.07) (Table 1). There was an increase in multiunit MSNA burst frequency, burst incidence, and mean burst area (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 1) at end-apnea. Any increase in multiunit MSNA during apnea was due to an increase in the frequency and incidence of AP spikes (APs/min, P = 0.048; APs/burst, P = 0.02; APs/100 heartbeats, P = 0.04) (Table 1). This included an increase in the probability of APs from the same cluster firing once per integrated MSNA burst (single firing, Fig. 3A; interaction of cluster and condition, P < 0.01) and more than once per burst (multiple firing, Fig. 3B; main effect of condition, P = 0.01). Although we observed a significant increase in cluster incidence (clusters/burst, P = 0.03; probability of multiple clusters/burst; Fig. 3C), an increase in max cluster number (P = 0.55) or incidence (P = 1.00) was not observed during apnea under normoxic conditions in the cohort studied (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Representative data during normoxic apnea. Representative recording of heart rate, mean blood pressure (MBP), muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) neurogram, and detected action potentials (APs) from 1 individual (male, 26 yr old) during quiet normoxic rest (baseline) and end-expiratory apnea.

Hypoxia.

Maximal end-expiratory apneas during hypoxia were 17.5 ± 3.5 s in length and resulted in a nadir oxygen saturation of 75 ± 2%. Significant increases in blood pressure (P < 0.01) and heart rate (P < 0.01) were observed during hypoxic apnea (Table 2). There was an increase in multiunit MSNA burst frequency (P < 0.01) and burst incidence (P < 0.01) during hypoxic apnea, in addition to an increase in mean burst area (P < 0.01) (Table 2). This increase in multiunit MSNA during hypoxic apnea was due to an increase in the frequency and incidence of AP spikes (APs/min, P < 0.01; APs/burst, P < 0.01; APs/100 heartbeats, P < 0.01) (Table 2). This included an increase in the probability of APs from the same cluster firing once per integrated MSNA burst (single firing, Fig. 4A; interaction of cluster and condition, P < 0.01) and more than once per burst (multiple firing, Fig. 4B; interaction of cluster and condition, P < 0.01). Although we observed a significant increase in cluster incidence (clusters/burst, P < 0.01; probability of multiple clusters/burst; Fig. 4C), an increase in max cluster number (P = 0.65) or incidence (P = 0.79) was not observed during apnea under hypoxic conditions in the cohort studied (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cardiorespiratory and neural responses to hypoxic end-expiratory apnea

| Normoxic Baseline | Hypoxic Baseline | Hypoxic Apnea | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | 60 ± 3 | 77 ± 3* | 81 ± 5* | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 146 ± 5 | 149 ± 5 | 164 ± 10*† | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 80 ± 3 | 81 ± 2 | 93 ± 4*† | <0.01 |

| Mean blood pressure, mmHg | 103 ± 3 | 104 ± 2 | 117 ± 5*† | <0.01 |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 99 ± 0 | 82 ± 1* | <0.01 | |

| , mmHg | 108 ± 7 | 50 ± 4* | <0.01 | |

| , mmHg | 39 ± 1 | 36 ± 2* | 0.03 | |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 10 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 0.17 | |

| Tidal volume, L/breath | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.10* | 0.045 | |

| Minute ventilation, mL/min | 5.7 ± 1.0 | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 0.14 | |

| Burst frequency, bursts/min | 20 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 46 ± 7*† | <0.01 |

| Burst incidence, bursts/100 heartbeats | 35 ± 7 | 30 ± 4 | 59 ± 7*† | <0.01 |

| Mean burst area, AU/min | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 1.6*† | <0.01 |

| AP frequency, APs/min | 192 ± 59 | 241 ± 72 | 952 ± 266*† | <0.01 |

| AP incidence, APs/burst | 9 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 | 18 ± 4*† | <0.01 |

| AP incidence, APs/100 heartbeats | 326 ± 89 | 309 ± 87 | 1,212 ± 327*† | <0.01 |

| Mean cluster incidence, clusters/burst | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 0.9*† | <0.01 |

| Max cluster incidence, clusters/burst | 7.7 ± 1.2 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 7.7 ± 1.1 | 0.79 |

| Max cluster number | 12.0 ± 1.9 | 12.7 ± 2.3 | 11.9 ± 2.4 | 0.65 |

| Data duration, s | 121 ± 1 | 102 ± 12 | 9 ± 2*† | <0.01 |

Data are reported as means ± SE for n = 7 subjects [n = 6 for arterial partial pressure of O2 (), arterial partial pressure of CO2 ()], respiratory rate, tidal volume, minute ventilation]. AP, action potential; AU, arbitrary units; , arterial O2 saturation from pulse oximetry. Data were analyzed with a 1-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. If not normally distributed, a Friedman repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks was conducted. Pairwise comparisons were done with the Holm–Sidak method. Bold type signifies statistical significance.

P < 0.05 vs. baseline;

P < 0.05 vs. hypoxia.

Hyperoxia.

Maximal end-expiratory apneas during hyperoxia were 64.7 ± 25.1 s in length and resulted in a nadir oxygen saturation of 100 ± 0%. Significant increases in blood pressure (P < 0.01) were observed during apnea (Table 3). No changes in multiunit MSNA were observed during hyperoxic apnea (P > 0.05), nor were any changes in the frequency or incidence of AP spikes observed (P > 0.05) (Table 3). Consistent with this, there were no changes in the probability of APs from the same cluster firing once per integrated MSNA burst (single firing, Fig. 5A; interaction of cluster and condition, P = 0.61) and more than once per burst (multiple firing, Fig. 5B; interaction of cluster and condition, P = 0.98). No changes in cluster incidence (clusters/burst, P = 0.57; probability of multiple clusters/burst; Fig. 5C) or max cluster number (P = 0.31) were observed during apnea under hyperoxic conditions (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We sought to examine the influences of chemoreceptor stimuli on sympathetic neural firing and recruitment strategies during voluntary end-expiratory apnea. Prior work has shown that during moderate levels of stress sympathetic activity is elevated through increased firing of already active neurons, whereas severe stress stimulates the recruitment of latent subpopulations of larger axons (Badrov et al. 2015). Present data support previous work and reveal three novel findings that provide further insight into key factors contributing to sympathetic neuronal firing and recruitment patterns in healthy humans. For the first time, we demonstrate that 1) increases in firing frequency at end-apnea are the result of an increase in the probability of previously recruited, low-threshold axons firing once (single firing) and more than once (multiple firing) per burst, 2) hypoxia exaggerates any increase in single and multiple within-burst firing at end-apnea, and 3) hyperoxia restrains any increase in multiple within-burst firing at end-apnea. Together, these data fill an important gap in knowledge and enhance our understanding of key neurovascular control mechanisms important in the human circulatory response to environmental stressors, such as hypoxic apnea.

Normoxia.

Voluntary end-expiratory apnea results in progressive increases in sympathetic nervous system activity until the asphyxic break point. Data from single-unit MSNA recordings in healthy adults have shown that at this break point there is greater within-burst firing of single axons (Macefield and Wallin 1999), which is similar to that observed after clinical exposure to chronic hypoxemia (Ashley et al. 2010; Elam et al. 2003). We extend these data and demonstrate for the first time that increases in firing frequency at end-apnea are the result of an increase in the probability of previously recruited, low-threshold axons from the same cluster firing once (single firing; Fig. 3A) and more than once (multiple firing; Fig. 3B) per burst.

In addition to the increase in multiple firing observed in the present investigation, Badrov and colleagues found that healthy young adults are also able to recruit subpopulations of previously silent and faster-conducting axons at end-apnea (Badrov et al. 2015, 2017; Klassen et al. 2018). However, the present cohort exhibited less capacity to recruit latent neural subpopulations, and recruitment strategies during normoxic apnea were more consistent with that from an older/aging population (Badrov et al. 2016). For example, at the asphyxic break point during normoxic apnea, we observed an increase in mean clusters per burst without an increase in max/total cluster number (indicating an increase in within-burst firing but lack of neural recruitment). In a study comparing younger (25 ± 3 yr) and older (59 ± 9 yr) adults, no increase in total cluster number at end-apnea was observed in the older cohort (12 ± 3 to 13 ± 4 total clusters), in contrast to responses in the younger cohort (8 ± 4 to 14 ± 5 total clusters) (Badrov et al. 2016). Given that our subjects were relatively older (~7 yr) than the young adults studied previously (Badrov et al. 2016), our data appear to further support the idea that age may play a role in the ability to recruit new clusters of APs during normoxic apnea. Consistent with this, a post hoc analysis of our data (for exploratory purposes) uncovered a relationship between age and recruitment (R = −0.56) despite the relatively young age of individuals studied (range 22–43 yr). In fact, we observed no increase in max cluster number at end-apnea in any individual > 28 yr of age. Although this is intriguing, future work in this area is warranted.

It is also possible that a shorter apnea duration in the present investigation compared with previous work (Badrov et al. 2015, 2017; Breskovic et al. 2011; Steinback et al. 2010) could limit the level of chemoreflex stress and thus the physiological need to enhance sympathetic activity. Consistent with this, sympathetic neuronal recruitment patterns have been shown to be similar between elite breath-hold divers and control subjects if the breath hold duration is similar (Breskovic et al. 2011). Although our average apnea duration was within the expected range for a voluntary, normoxic breath hold in untrained individuals (Baković et al. 2003; Heusser et al. 2009; Palada et al. 2007), it was shorter than that published by groups showing enhanced recruitment (~32 s vs. ~44 s) (Badrov et al. 2015; Breskovic et al. 2011). Thus, the recruitment of latent axons observed previously may be linked only to experienced breath holders who can sustain and/or provoke large changes in chemoreflex stimuli or endure strong drive to breathe. Along these lines, in the investigation by Badrov and colleagues (Badrov et al. 2015, 2017) apneas were conducted after rebreathe (to elicit “severe” chemoreflex stress, including a reduction in end-tidal Po2 and an increase in end-tidal Pco2); therefore, it is difficult to compare results between studies. Thus, it remains unclear as to whether such strategies are related to effort (i.e., central drive to breathe) and/or chemoreflex stress alone. Therefore, we sought to examine the influences of chemoreceptor stimuli (i.e., hypoxia, hyperoxia) on sympathetic neural firing and recruitment strategies at baseline and during voluntary end-expiratory apnea.

Hypoxia.

Any increase in multiunit MSNA during apnea has been shown previously to be augmented by hypoxemia (Hardy et al. 1994), with chemoreflex stress exerting preferential influence on burst size (Lim et al. 2015; Malpas et al. 1996). For the first time, we demonstrate that hypoxic stress alone (i.e., arterial O2 saturation from pulse oximetry 82 ± 1%, 50 ± 4 mmHg) does not augment neural firing and/or recruitment; rather, the added stress of apnea is necessary (Table 2). Consistent with this, Badrov and colleagues have shown the presence of a “sympathetic reserve,” whereby latent subpopulations of larger-amplitude sympathetic neurons are reserved for periods of “severe” chemoreflex-mediated stress (Badrov et al. 2015). Similarly, the present data show an increase in multiunit MSNA during hypoxia when combined with apnea that is due to an increase in the frequency and incidence of AP spikes (i.e., an increase in the number of active efferent postganglionic sympathetic neurons). Thus, consistent with our hypothesis, end-expiratory apnea results in an increase in firing frequency and probability of low-threshold axons, which was exaggerated during hypoxemia. In addition, during hypoxic apnea we observed recruitment of latent subpopulations of higher-threshold axons at the asphyxic break point, which was not observed under normoxic conditions. We further demonstrate for the first time that hypoxic apnea results in an increase in the probability of APs from the same cluster firing once (Fig. 4A) and more than once (Fig. 4B) per integrated burst.

There are data that suggest that multiple within-burst firing (the same axon firing more than once per integrated burst) increases release of norepinephrine and colocalized neurotransmitters, thereby increasing neurally mediated vasoconstriction (Andersson 1983; Lambert et al. 2011; Murai et al. 2006, 2009; Nilsson et al. 1985). Furthermore, previous work with ganglionic blockade suggests that the pressor response to apnea is sympathetically mediated (Katragadda et al. 1997). Taken together with our data, it is reasonable to suggest that alterations in sympathetic neural firing patterns in response to acute hypoxic apnea play an essential role in eliciting an appropriate vasoconstrictor response. As a result, there is likely a greater fall in peripheral blood flow. Given that the goal of peripheral vasoconstriction at end-apnea is to redistribute blood flow and oxygen away from the skeletal muscle toward the brain, this may have important clinical implications for conditions prone to hypoxic apnea (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, sleep apnea, chronic heart failure) and also provides a useful model for studying neurovascular transduction (Shoemaker 2017; Shoemaker et al. 2015, 2018; White et al. 2015) or the ability of sympathetic activity to elicit vasoconstriction.

Despite a clear increase in AP firing with hypoxic apnea, the present data also show the effect of apnea on firing probabilities to be highly variable across clusters (i.e., populations of APs with similar peak-to-peak amplitudes). For example, the probability of medium-threshold axons (~50% of total cluster number) firing once and more than once per burst increases at end-expiratory hypoxic apnea (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, lower-threshold axons tend to decrease their probability of firing (Fig. 4, A and B); similar patterns are seen during normoxic apnea (Fig. 3A). Although speculative, these findings may be related to the variable impact of baroreflex control over AP occurrence (Salmanpour and Shoemaker 2012). It has been shown previously that the slope of the baroreflex threshold relationship is greater for small, lower-threshold AP clusters than for larger, higher-threshold APs (Salmanpour and Shoemaker 2012). Thus, we propose that increases in blood pressure resulting from firing of recruitable, larger-threshold APs at end-apnea elicit a baroreflex-mediated attenuation of lower-threshold AP firing. We speculate that these distinct differences in firing strategies at end-apnea play an essential role in eliciting an appropriate vasoconstrictor response while buffering large swings in blood pressure. This particularly interesting and unexpected finding warrants additional work in this area.

Hyperoxia.

It has long been known that apnea duration is significantly increased during hyperoxia (Bain et al. 2017; Hardy et al. 1994). In the present investigation, we found that hyperoxia prolongs apnea time and show, for the first time, that concurrent hyperoxia restrains any increase in firing of already active, lower-threshold axons at end-apnea including an attenuation of multiple within-burst firing. The lower reflex increase in MSNA during hyperoxic apnea is consistent with our hypothesis and is likely the result of a lack of hypoxic chemoreceptor stimulation. Consistent with this, previous work has shown that low-dose dopamine, which suppresses the peripheral chemoreflex (Limberg et al. 2016), can extend/prolong hypoxic stress of voluntary apnea (van de Borne et al. 1998). Together these data suggest that increases in AP single and multiple firing at end-apnea are due, at least in part, to chemoreflex stress.

Future work will be necessary to better understand the impact of such changes in firing on peripheral blood flow and blood pressure regulation. Although speculative, the present data suggest that suppression of augmented firing patterns during voluntary end-expiratory apnea via prior hyperoxic exposure may attenuate the rise in blood pressure at end-apnea (Δmean blood pressure at end-apnea: normoxia ~17 mmHg; hyperoxia ~12 mmHg). Thus, manipulation of chemoreceptor activity may be an effective strategy to attenuate blood pressure during apnea because of its effects on sympathetic neural firing patterns. Consistent with this, attenuation of nocturnal hypoxemia has been shown to reduce multiunit MSNA (Narkiewicz et al. 1999) as well as large swings in blood pressure (i.e., blood pressure “surges”) (Carter et al. 2016) in patients with sleep apnea; however, neural firing patterns have not been directly examined. Such analyses provide a more sensitive measure of central sympathetic drive and may be useful in exploring contributing mechanisms. With this, the present data also suggest that hyperoxia could be useful in the laboratory setting as a model to study the role of central versus peripheral control of AP firing.

Experimental considerations.

It is important to acknowledge that only male subjects were tested in this study; however, given the potential for changes in circulating sex hormones to modulate the sympathetic response to chemoreflex activation (Usselman et al. 2016) future research should include female participants. Second, the present approach classifies the contribution of multiple vasomotor neurons to multiunit integrated MSNA bursts morphologically based on peak-to-peak amplitude (Salmanpour et al. 2010). This approach complements the single-unit approach (Macefield et al. 1994; Macefield and Wallin 1999), although it cannot determine whether APs with the same size/morphology are from the same or different neurons (Salmanpour et al. 2010). Third, individuals completed voluntary end-expiratory apneas (instructed to hold at functional residual volume) to the asphyxic break point. Thus, it is unlikely that variations in lung volume or respiratory drive influenced conclusions. However, apnea duration can impact carbon dioxide accumulation; thus exposure to carbon dioxide was not controlled for between conditions and was likely smallest during hypoxia (short duration) and greatest during hyperoxia (long duration) (Bain et al. 2017). It should also be noted that although hyperoxia is thought to attenuate the chemoreflex, we observed an apparent paradoxical increase in minute ventilation during steady-state hyperoxia, which has been shown previously (Becker et al. 1996, Leuenberger et al. 2001).

Conclusions.

These data are the first to show that neural firing patterns in response to voluntary end-expiratory apnea are modified by hypoxia and hyperoxia. In the present investigation we demonstrate for the first time an increase in the frequency and incidence of AP spikes, as well as the probability of multiple firing, during hypoxic apnea that is suppressed under conditions of hyperoxia, highlighting the potentially important role of the chemoreceptors in MSNA AP patterns. We also present novel data showing that firing probabilities are highly variable across AP clusters such that some clusters increase firing probability with apnea while others decrease firing probability. We speculate that these distinct differences in firing strategies at end-apnea play an essential role in eliciting an appropriate vasoconstrictor response while buffering large swings in blood pressure. Although further work will be needed to directly assess whether differences in AP firing translate to changes in neurovascular transduction, these data likely have important implications for neural control of the circulation in recreational (e.g., breath-hold diving) and/or clinical (e.g., sleep apnea) conditions prone to apnea.

GRANTS

This study was supported by American Heart Association Grant 15SDG25080095 (J. K. Limberg), NIH Grant HL-130339 (J. K. Limberg), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant program (J. K. Shoemaker). J. K. Shoemaker is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.K.S. and J.K.L. conceived and designed research; S.E.B., W.W.H., J.K.S., and J.K.L. performed experiments; E.P.O. analyzed data; E.P.O., S.E.B., J.K.S., and J.K.L. interpreted results of experiments; J.K.L. prepared figures; E.P.O. and J.K.L. drafted manuscript; E.P.O., S.E.B., W.W.H., J.K.S., and J.K.L. edited and revised manuscript; E.P.O., S.E.B., W.W.H., J.K.S., and J.K.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to the research participants as well as individuals involved in recruitment, scheduling, and data collection: Nancy Meyer, Sarah Wolhart, Shelly Roberts, Christopher Johnson, Andrew Miller, Zachariah Scruggs, Gabrielle Dillion, Humphrey Petersen-Jones, Lauren Newhouse. Thanks as well to Michael Joyner, Timothy Curry, Mark Badrov, and Stephen Klassen for intellectual and technical contributions to the project.

REFERENCES

- Andersson PO. Comparative vascular effects of stimulation continuously and in bursts of the sympathetic nerves to cat skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand 118: 343–348, 1983. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1983.tb07281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley C, Burton D, Sverrisdottir YB, Sander M, McKenzie DK, Macefield VG. Firing probability and mean firing rates of human muscle vasoconstrictor neurones are elevated during chronic asphyxia. J Physiol 588: 701–712, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.185348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrov MB, Barak OF, Mijacika T, Shoemaker LN, Borrell LJ, Lojpur M, Drvis I, Dujic Z, Shoemaker JK. Ventilation inhibits sympathetic action potential recruitment even during severe chemoreflex stress. J Neurophysiol 118: 2914–2924, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00381.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrov MB, Lalande S, Olver TD, Suskin N, Shoemaker JK. Effects of aging and coronary artery disease on sympathetic neural recruitment strategies during end-inspiratory and end-expiratory apnea. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H1040–H1050, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00334.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrov MB, Usselman CW, Shoemaker JK. Sympathetic neural recruitment strategies: responses to severe chemoreflex and baroreflex stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R160–R168, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00077.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain AR, Ainslie PN, Barak OF, Hoiland RL, Drvis I, Mijacika T, Bailey DM, Santoro A, DeMasi DK, Dujic Z, MacLeod DB. Hypercapnia is essential to reduce the cerebral oxidative metabolism during extreme apnea in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37: 3231–3242, 2017. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16686093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baković D, Valic Z, Eterović D, Vukovic I, Obad A, Marinović-Terzić I, Dujić Z. Spleen volume and blood flow response to repeated breath-hold apneas. J Appl Physiol (1985) 95: 1460–1466, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00221.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HF, Polo O, McNamara SG, Berthon-Jones M, Sullivan CE. Effect of different levels of hyperoxia on breathing in healthy subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985) 81: 1683–1690, 1996. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.4.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breskovic T, Steinback CD, Salmanpour A, Shoemaker JK, Dujic Z. Recruitment pattern of sympathetic neurons during breath-holding at different lung volumes in apnea divers and controls. Auton Neurosci 164: 74–81, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briant LJ, O’Callaghan EL, Champneys AR, Paton JF. Respiratory modulated sympathetic activity: a putative mechanism for developing vascular resistance? J Physiol 593: 5341–5360, 2015. doi: 10.1113/JP271253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JR, Fonkoue IT, Grimaldi D, Emami L, Gozal D, Sullivan CE, Mokhlesi B. Positive airway pressure improves nocturnal beat-to-beat blood pressure surges in obesity hypoventilation syndrome with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R602–R611, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00516.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry TB, Charkoudian N. The use of real-time ultrasound in microneurography. Auton Neurosci 162: 89–93, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Sheel AW, St. Croix CM, Morgan BJ. Respiratory influences on sympathetic vasomotor outflow in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 130: 3–20, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(01)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg DL, Nerhed C, Wallin BG. Respiratory modulation of muscle sympathetic and vagal cardiac outflow in man. J Physiol 365: 181–196, 1985. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam M, Macefield V. Multiple firing of single muscle vasoconstrictor neurons during cardiac dysrhythmias in human heart failure. J Appl Physiol (1985) 91: 717–724, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam M, Sverrisdottir YB, Rundqvist B, McKenzie D, Wallin BG, Macefield VG. Pathological sympathoexcitation: how is it achieved? Acta Physiol Scand 177: 405–411, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL, Ferris EB, Webb JP, Stevens CD. Voluntary breathholding. II. The relation of the maximum time of breathholding to the oxygen tension of the inspired air. J Clin Invest 25: 729–733, 1946. doi: 10.1172/JCI101756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatouleh R, Macefield VG. Respiratory modulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity is not increased in essential hypertension or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Physiol 589: 4997–5006, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.210534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris EB, Engel GL, Stevens CD, Webb J. Voluntary breathholding. III. The relation of the maximum time of breathholding to the oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions of arterial blood, with a note on its clinical and physiological significance. J Clin Invest 25: 734–743, 1946. doi: 10.1172/JCI101757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley LJ, Ries AL, Tisi GM, Wagner PD. Hypoxemia during apnea in normal subjects: mechanisms and impact of lung volume. J Appl Physiol 55: 1777–1783, 1983. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.6.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey S, Campbell EJ. The control of breath holding. Respir Physiol 5: 385–400, 1968. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(68)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagbarth KE, Vallbo AB. Pulse and respiratory grouping of sympathetic impulses in human muscle-nerves. Acta Physiol Scand 74: 96–108, 1968. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.1968.tb10904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwill JR, Minson CT. Effect of hypoxia on arterial baroreflex control of heart rate and muscle sympathetic nerve activity in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 857–864, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01103.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwill JR, Morgan BJ, Charkoudian N. Peripheral chemoreflex and baroreflex interactions in cardiovascular regulation in humans. J Physiol 552: 295–302, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JC, Gray K, Whisler S, Leuenberger U. Sympathetic and blood pressure responses to voluntary apnea are augmented by hypoxemia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 77: 2360–2365, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.5.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heistad DD, Abbound FM, Eckstein JW. Vasoconstrictor response to simulated diving in man. J Appl Physiol 25: 542–549, 1968. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.5.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heusser K, Dzamonja G, Tank J, Palada I, Valic Z, Bakovic D, Obad A, Ivancev V, Breskovic T, Diedrich A, Joyner MJ, Luft FC, Jordan J, Dujic Z. Cardiovascular regulation during apnea in elite divers. Hypertension 53: 719–724, 2009. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katragadda S, Xie A, Puleo D, Skatrud JB, Morgan BJ. Neural mechanism of the pressor response to obstructive and nonobstructive apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985) 83: 2048–2054, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen SA, De Abreu S, Greaves DK, Kimmerly DS, Arbeille P, Denise P, Hughson RL, Normand H, Shoemaker JK. Long-duration bed rest modifies sympathetic neural recruitment strategies in male and female participants. J Appl Physiol (1985) 124: 769–779, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00640.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klocke FJ, Rahn H. Breath holding after breathing of oxygen. J Appl Physiol 14: 689–693, 1959. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1959.14.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert EA, Schlaich MP, Dawood T, Sari C, Chopra R, Barton DA, Kaye DM, Elam M, Esler MD, Lambert GW. Single-unit muscle sympathetic nervous activity and its relation to cardiac noradrenaline spillover. J Physiol 589: 2597–2605, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.205351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger UA, Hardy JC, Herr MD, Gray KS, Sinoway LI. Hypoxia augments apnea-induced peripheral vasoconstriction in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 90: 1516–1522, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.4.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K, Burke SL, Moretti JL, Head GA. Differential activation of renal sympathetic burst amplitude and frequency during hypoxia, stress and baroreflexes with chronic angiotensin treatment. Exp Physiol 100: 1132–1144, 2015. doi: 10.1113/EP085312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limberg JK, Johnson BD, Holbein WW, Ranadive SM, Mozer MT, Joyner MJ. Interindividual variability in the dose-specific effect of dopamine on carotid chemoreceptor sensitivity to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 120: 138–147, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00723.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limberg JK, Ott EP, Holbein WW, Baker SE, Curry TB, Nicholson WT, Joyner MJ, Shoemaker JK. Pharmacological assessment of the contribution of the arterial baroreflex to sympathetic discharge patterns in healthy humans. J Neurophysiol 119: 2166–2175, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00935.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YC, Lally DA, Moore TO, Hong SK. Physiological and conventional breath-hold breaking points. J Appl Physiol 37: 291–296, 1974. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macefield VG, Wallin BG. Effects of static lung inflation on sympathetic activity in human muscle nerves at rest and during asphyxia. J Auton Nerv Syst 53: 148–156, 1995a. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00174-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macefield VG, Wallin BG. Modulation of muscle sympathetic activity during spontaneous and artificial ventilation and apnoea in humans. J Auton Nerv Syst 53: 137–147, 1995b. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00173-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macefield VG, Wallin BG. Firing properties of single vasoconstrictor neurones in human subjects with high levels of muscle sympathetic activity. J Physiol 516: 293–301, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.293aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macefield VG, Wallin BG, Vallbo AB. The discharge behaviour of single vasoconstrictor motoneurones in human muscle nerves. J Physiol 481: 799–809, 1994. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malpas SC, Shweta A, Anderson WP, Head GA. Functional response to graded increases in renal nerve activity during hypoxia in conscious rabbits. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 271: R1489–R1499, 1996. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.6.R1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan BJ, Denahan T, Ebert TJ. Neurocirculatory consequences of negative intrathoracic pressure vs. asphyxia during voluntary apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985) 74: 2969–2975, 1993. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai H, Takamura M, Maruyama M, Nakano M, Ikeda T, Kobayashi D, Otowa K, Ootsuji H, Okajima M, Furusho H, Takata S, Kaneko S. Altered firing pattern of single-unit muscle sympathetic nerve activity during handgrip exercise in chronic heart failure. J Physiol 587: 2613–2622, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai H, Takata S, Maruyama M, Nakano M, Kobayashi D, Otowa K, Takamura M, Yuasa T, Sakagami S, Kaneko S. The activity of a single muscle sympathetic vasoconstrictor nerve unit is affected by physiological stress in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H853–H860, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00184.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, Kato M, Phillips BG, Pesek CA, Davison DE, Somers VK. Nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure decreases daytime sympathetic traffic in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 100: 2332–2335, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.23.2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson H, Ljung B, Sjöblom N, Wallin BG. The influence of the sympathetic impulse pattern on contractile responses of rat mesenteric arteries and veins. Acta Physiol Scand 123: 303–309, 1985. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1985.tb07592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palada I, Obad A, Bakovic D, Valic Z, Ivancev V, Dujic Z. Cerebral and peripheral hemodynamics and oxygenation during maximal dry breath-holds. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 157: 374–381, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes MJ. Breath-holding and its breakpoint. Exp Physiol 91: 1–15, 2006. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnoli S, Ricci Z, Quattrone D, Tofani L, Tujjar O, Villa G, Romano SM, De Gaudio AR. Accuracy of invasive arterial pressure monitoring in cardiovascular patients: an observational study. Crit Care 18: 644, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0644-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnoli S, Romano SM, Bevilacqua S, Lazzeri C, Gensini GF, Pratesi C, Quattrone D, Dini D, De Gaudio AR. Dynamic response of liquid-filled catheter systems for measurement of blood pressure: precision of measurements and reliability of the Pressure Recording Analytical Method with different disposable systems. J Crit Care 26: 415–422, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Mano T, Iwase S, Koga K, Abe H, Yamazaki Y. Responses in muscle sympathetic activity to acute hypoxia in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 65: 1548–1552, 1988. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.4.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmanpour A, Brown LJ, Shoemaker JK. Spike detection in human muscle sympathetic nerve activity using a matched wavelet approach. J Neurosci Methods 193: 343–355, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmanpour A, Shoemaker JK. Baroreflex mechanisms regulating the occurrence of neural spikes in human muscle sympathetic nerve activity. J Neurophysiol 107: 3409–3416, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00925.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. On optimal and data-based histograms. Biometrika 66: 605–610, 1979. doi: 10.1093/biomet/66.3.605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DR, Suwarno NO, Dempsey JA. Influence of lung volume on sympathetic nerve discharge in normal humans. Circ Res 67: 130–141, 1990. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.67.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DR, Suwarno NO, Joyner MJ, Iber C, Copeland JG, Dempsey JA. Respiratory modulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in intact and lung denervated humans. Circ Res 72: 440–454, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.72.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuzzaman A, Ackerman MJ, Kuniyoshi FS, Accurso V, Davison D, Amin RS, Somers VK. Sympathetic nerve activity and simulated diving in healthy humans. Auton Neurosci 181: 74–78, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker JK. Recruitment strategies in efferent sympathetic nerve activity. Clin Auton Res 27: 369–378, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker JK, Badrov MB, Al-Khazraji BK, Jackson DN. Neural control of vascular function in skeletal muscle. Compr Physiol 6: 303–329, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker JK, Klassen SA, Badrov MB, Fadel PJ. Fifty years of microneurography: learning the language of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system in humans. J Neurophysiol 119: 1731–1744, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00841.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers VK, Mark AL, Zavala DC, Abboud FM. Contrasting effects of hypoxia and hypercapnia on ventilation and sympathetic activity in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 67: 2101–2106, 1989a. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.5.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers VK, Mark AL, Zavala DC, Abboud FM. Influence of ventilation and hypocapnia on sympathetic nerve responses to hypoxia in normal humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 67: 2095–2100, 1989b. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.5.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinback CD, Breskovic T, Frances M, Dujic Z, Shoemaker JK. Ventilatory restraint of sympathetic activity during chemoreflex stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R1407–R1414, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00432.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usselman CW, Steinback CD, Shoemaker JK. Effects of one’s sex and sex hormones on sympathetic responses to chemoreflex activation. Exp Physiol 101: 362–367, 2016. doi: 10.1113/EP085147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB, Hagbarth KE, Torebjörk HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiol Rev 59: 919–957, 1979. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Borne P, Oren R, Somers VK. Dopamine depresses minute ventilation in patients with heart failure. Circulation 98: 126–131, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DW, Shoemaker JK, Raven PB. Methods and considerations for the analysis and standardization of assessing muscle sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Auton Neurosci 193: 12–21, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]