Abstract

Genetic contribution to progressive hearing loss in adults is underestimated. Established machine learning-based software could offer a rapid supportive tool to stratify patients with progressive hearing loss. A retrospective longitudinal analysis of 141 adult patients presenting with hearing loss was performed. Hearing threshold was measured at least twice 18 months or more apart. Based on the baseline audiogram, hearing thresholds and age were uploaded to AudioGene v4® (Center for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology at The University of Iowa City, IA, USA) to predict the underlying genetic cause of hearing loss and the likely progression of hearing loss. The progression of hearing loss was validated by comparison with the most recent audiogram data of the patients. The most frequently predicted loci were DFNA2B, DFNA9 and DFNA2A. The frequency of loci/genes predicted by AudioGene remains consistent when using the initial or the final audiogram of the patients. In conclusion, machine learning-based software analysis of clinical data might be a useful tool to identify patients at risk for having autosomal dominant hearing loss. With this approach, patients with suspected progressive hearing loss could be subjected to close audiological followup, genetic testing and improved patient counselling.

Key words: Machine learning, Progressive hearing loss, Audiogram, Phenotype, Genotype

Introduction

Sensorineural hearing loss is the most common neurodegenerative disease in man. Based on a report of the World Health Organization, up to 7% of the world’s population suffers from disabling hearing loss.1 This equals approximately 460 million people. Estimates indicate that unaddressed hearing loss places an economical burden of more than 750-790 billion dollars annually on society. About 30 million Americans are at risk to develop hearing loss due to their lifestyle and more than 2/3 of the elderly (<70 years) suffer from hearing loss.2,3 The causes of hearing loss are multiple, ranging from genetic predisposition, infections, ototoxic agents, immunological and environmental factors, especially noise and ageing to unknown.

In daily clinical routine, the cause as well as the course of progression remains unknown in many patients. Especially in office based otology, however, early identification of the patients that suffer from rapid progression can enable early treatment or timely admission to specialised centres for more precise and in-depth diagnostics and early intervention. Pure tone audiometry is the gold standard measure to evaluate patients with hearing loss, aiding in the diagnosis of many audiological and otologic disorders.4 It provides information about type, degree, and configuration of hearing loss.4 Hearing sensitivity is reflected with the audiogram whereas information about auditory processing of speech and music or about central auditory processing is not provided.4 Although the audiogram does not predict specific cellular damage in the inner ear, empiric data suggest that in certain cases the shape of the audiogram reflects the underlying disease.5,6

Machine learning (ML) is a central component of artificial intelligence.7 In 1959, Arthur Samuel defined ML as the ability of computers to learn without being explicitly programmed. There are several ML algorithms available, i.e., supervised, unsupervised and semi-supervised learning, reinforcement learning, transductive learning and inductive learning by imitation and many more. Supervised learning algorithms learn from labelled data, i.e. data for which the desired output values are known. After learning, algorithms can then be used for classification or regression. In classification, for instance, they allow for accurately predicting the class labels or previously unobserved data instances.8

Semi-supervised learning uses a small set of labelled data and a large set of unlabelled. It is of increasing practical relevance and closely links to areas of human learning. Reinforcement learning is a control-theoretic trial-and-error learning paradigm with rewards and punishment associated with a sequence of actions and is likewise closely linked to human learning.8 Transductive learning attempts to predict exclusive model functions on specific test cases whereas inductive inference estimates the model function based on the relation of data to the entire hypothesis space.8

In recent years, ML has significantly influenced science and medicine. In healthcare, ML has been reported to be useful, for instance, in the interpretation of complex and big data, the categorisation of diseases based on their molecular profile, the screening and optimisation of drug therapy, the assessment of risks and the prediction of outcome for specific diseases.9-11

Autosomal dominant hearing loss accounts for about 15% of the inherited cases of hearing loss. Most of these cases present with postlingual progressive hearing loss. AudioGene v4® (Center for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology at The University of Iowa City, IA, USA) is a software implementing ML techniques to prioritise genetic loci for autosomal dominant hearing loss based on the audio-profile of the individual patient.12 An audio-profile is generated from different audiograms plotted on one graph to define common features of the audiological phenotype that is associated with a specific genotype. The audiograms included are typically obtained from several members in a family with the same underlying mutation or from a single individual at different time points.13

Auxiliary tools to support the physician in the identification of patients with progressive hearing loss may lead to a close follow up and early intervention. Such tools might be especially helpful in office-based otology only if they are readily available, rapid and cost effective. The aim of the present study was to use AudioGene® for a retrospective phenotype-genotype correlation based on the first available audiograms to predict the progression of hearing loss at least for patients suspicious for autosomal dominant hearing loss. The results obtained were compared with the latest audiograms of the patients. All patients were seen at the office of a general ears-nose-and-throat practitioner.

Materials and Methods

The study was reported to the institutional Ethics Committee. No approval was required due to retrospective acquisition of anonymised patients’ data. Among the patients who visited an office-based otolaryngologist during a defined time period (07/2018-08/2018), adult patients (at the time of the last audiogram) who had two or more pure tone audiometry examinations at least 18 months apart were included. If more than two pure tone audiometry data sets were present, the two audiograms being most apart were included. Audiometric data were obtained in a silenced chamber by using the BCA 300 audiometer (Steinmeier Audio- Med GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany). The audiometer is calibrated yearly and the calibration report has to be sent to the Medical Association of Lower Saxony. Experienced staff members investigated all patients. The audiogram data were extracted and analysed retrospectively. The thresholds of the different frequencies (i.e., 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz) were averaged (pure tone average, PTA) and the differences between the newest and oldest audiogram were calculated. The threshold at 3 kHz was only included in the analysis when it was present in both audiograms. If 3 kHz was only measured in one of the two included audiograms, the values for 3kHz were excluded from analysis. Also, if the threshold of the higher frequencies could not be determined due to profound deafness, the value 110 dB was inserted as threshold. The time between the two audiograms was determined in years with two digits after the decimal.

Demographic data including age and gender were also extracted. The data were collected in an excel sheet according to the template accessed from AudioGene®. Patient data were anonymised. The age of the patients as well as the information on the side of the better hearing ear were noted in the excel sheet as indicated in the template. The pure tone thresholds of the different frequencies (i.e., 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz) from the oldest audiogram from the better ear were also included in the excel sheet. The excel sheet was up-loaded according the instructions found on the website of audiogene (https://audiogene.eng. uiowa.edu). For a detailed description of AudioGene®, we refer to the publication by Hildebrand et al.14

Analysis with AudioGene v4.0 was based on the data from the first available audiogram. In addition, the most recent audiogram was also analysed with AudioGene v4.0. The predictions based on the two audiograms (first and most recent) were compared to each other. Predictions on progression of hearing loss obtained were compared to the delta-PTA between the first and the last audiogram.

Statistical analysis was performed with Graph Pad Prism. To calculate differences between the groups, the unpaired t-test was used. All data were presented as mean ± standard error of mean including minimum and maximum.

Results

A total of 141 patients were included in the study (Table 1). Of the patients, 76 were male and 65 were female. The mean age of the patients at the time of the first audiogram was 57.3 years (ranging from 13.8 to 94.6 years). The mean age of the patients at the time of the final audiogram was 69.2 years (ranging from 38.1 to 96.4 years). The mean time period between the two audiogram measurements was 12.2 ± 7.9 SD years (range 1.6 to 26.1 years).

Using Audiogene® on the first available audiogram, the putative autosomal dominant genetic mutation was predicted. Based on the first and last audioprofile, several genes were predicted after completion of analysis (Table 2). The prediction based on the first audioprofile suggested the following genes: DFNA2B (n=73), DFNA9 (n=48), DFNA2A (n=6), DFNA16, DFNA22 and DFNA43 (each n=3), DFNA57 (n=2), DFNA15 (n=2) and DFNA25 in one case. The genes suspected as a cause for the hearing loss identified code for GJB3 (DFNA2B), COCH (DFNA9), KCNQ4 (DFNA2A), unknown gene (DFNA16, DFNA43, DFNA57), Myo6 (DFNA22), Pou4F3 (DFNA15) and SLC17A8 (DFNA25). A second analysis using AudioGene v4.0 was performed using the most recent audiogram of the 141 patients included. Interestingly, the top 2 genes predicted based on the first audioprofile (GJB3 and COCH) were also most frequently predicted based on the last audiogram (DFNA2B in n=73; DFNA9 in n=48; Table 2). DFNA16 (unknown gene) was predicted in 3 patients based on the first audiogram but in none of the patients when the analysis was based on the last audiogram. DFNA24 (unknown gene), DFNA44 (CCDC50), DFNA8/12 (TECTA), DFNA2notAnotB (unknown gene), DFNA13 (unknown), DFNA16 (unknown), DFNA18 (unknown) and DFNA50 (MIRN96) were predicted based on the last but not on the first audiogram.

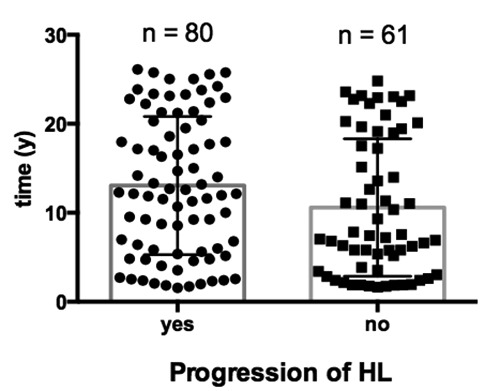

Of the 141 patients, 82 developed progression of hearing loss of more than 10 dB PTA and 59 patients showed a stable audiogram during the observed time period (progression of PTA of less than 10 dB). The mean time between the fist and the last audiogram was 13.05 years (range 1.57-26.10) for the group of the patients showing progressive hearing loss and 10.59 years (range 1.65-24.82) for the patients showing stable hearing. Figure 1 shows the time between the first and the last audiogram in patients with stable hearing and with progression of hearing loss. A nearly equal distribution of the time between the two audiograms is imposing.

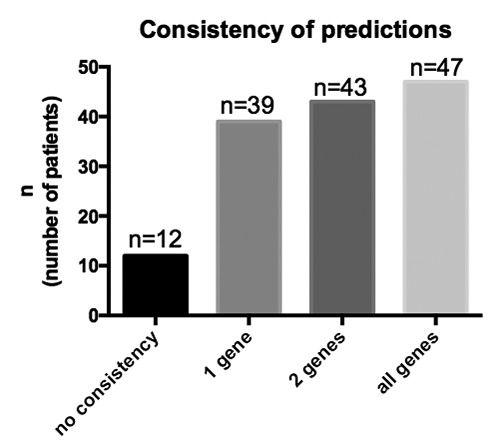

We included three predictions for each patient in our analysis based on the first and the last available audiogram and compared the consistency of the predictions. For the majority of the patients (n=47), all three predicted genes based on the first audiogram were identical to the genes predicted based on the latest audiogram. For 43 patients, 2 genes were consistent in the predictions, and for 39 patients, one gene was consistent. Only in 12 patients (8.5%), none of the genes were consistent.

Discussion

Clinical otology produces a wealth of data from different investigations as part of the daily clinical routine, especially in tertiary highly specialised centres. Often, these data are stored in different databases and not readily available for research purposes. Automated stage and abstraction of these data would not only facilitate in depth clinical research, but also could be made available in office based otology for specialised general patient care. The inherent heterogeneity in most common diseases including hearing loss demand a redefinition of disease based on pathophysiology in order provide valid new therapeutic approaches.16 However, complex multifactorial diseases make this task difficult. 16

Figure 1.

Based on the delta-pure tone average (PTA), patients were divided in two groups: progression (delta-PTA 10 dB or more) or no progression of hearing loss (HL) (delta-PTA<10 dB). The time between the two audiograms was plotted on the y-axis. No significant difference was calculated between the two groups (P=0.06, unpaired t-test).

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Demographic data | Age (years*) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | 57.25 | 141 |

| Male | 56.74 | 73 |

| Female | 57.79 | 68 |

*Median.

Table 2.

List of predicted genes based on the first and on the last audiogram.

| Locus | Gene | 1st | Last | Audioprofile* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFNA2B | GJB3 | 73 | 65 | High frequency; progressive |

| DFNA9 | COCH | 48 | 29 | High frequency; progressive |

| DFNA2A | KCNQ4 | 6 | 7 | High frequency; progressive |

| DFNA16 | unknown | 3 | 0 | - |

| DFNA43 | unknown | 3 | 8 | - |

| DFNA22 | MYO6 | 3 | 4 | High frequency; progressive |

| DFNA57 | unknown | 2 | 5 | - |

| DFNA15 | POU4F3 | 2 | 9 | High frequency; progressive |

| DFNA16 | unknown | 0 | 3 | - |

| DFNA25 | SCL17A8 | 1 | 2 | High frequency; progressive |

| DFNA24 | unknown | 0 | 2 | - |

| DFNA44 | CCDC50 | 0 | 2 | Low to mid frequencies; progressive |

| DFNA8/12 | TECTA | 0 | 1 | Mid-frequency loss |

| DFNA2 notAnotB | unknown | 0 | 1 | - |

| DFNA13 | COL11A2 | 0 | 1 | Mid-frequency loss |

| DFNA18 | unknown | 0 | 1 | - |

| DFNA50 | MIRN96 | 0 | 1 | Flat; progressive |

*Gene and phenotype from: Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Smith RJH, 1993.15

Especially for big data applications, supervised and unsupervised learning allows operation at highest efficiency by bypassing the lack of capability of humans to analyse data in real time due to the sheer volume, the diversity and the speed of data flow.8 In this context, the ability of ML to predict future scenarios that are unknown to the computer makes this tool highly valuable.8 The automated interpretation of electrocardiography is the most common example of supervised learning in medicine.16 A well-trained and experienced person, however, can perform such a task better than ML. By using supervised learning algorithms, the computer can identify novel relationships that are not readily apparent to humans.16

In office based otology as well as in any other disciplines, time is the most valuable resource and ML-based clinical decision support should be time efficient and easily fitting into the workflow of the busy clinical or office routine.17 A simple and easy to learn and use approach making time consuming training unnecessary is required to obtain advice or analytic results with a high reproducibility and strong evidence based scientific foundation.17

Cluster analysis to classify the audiogram shape in patients with idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss has been performed previously. 18With this method, the shape of the audiogram has been identified as a prognostic indicator aiding in the management of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss showing higher rates of recovery for the patients with low-frequency or mid-frequency hearing loss when compared to flat or down-sloping hearing loss.18 In addition, cluster analysis allows standardisation of diagnosis across centres minimising errors that may arise from the personal experience of the examiner.19

A systematic classification of audiogram shape has been initiated in the early 1960s by Schuknecht, who introduced flat, downsloping, and abrupt high-tone hearing loss and correlation to pathophysiological changes in the auditory pathway.6,19 More refined classifications of audiograms may be necessary in order to represent as many of the aetiologies reflected in the shape of the audiogram as possible. Approaches to even test hearing function in the absence of a physician or audiologist are possible using online machine learning audiometry consisting of a nonparametric Bayesian estimator of tone detection probability as a function of frequency and sound level.20 Epidemiological and genetic studies can be applied to identify risk factors for age-related hearing impairment.6 Usually, one phenotype is used to define the presence/ absence of hearing impairment due to genetics causes, ageing or to determine possible risk factors or causes.6 However, for some conditions, more than one shape has to be considered. Due to the complexity of hearing loss, taking into account the shape of the audiogram adds value to the identification of the aetiological background as well as in the prediction of progression. Using AudioGene v4®, the predicted progression of hearing loss in all patients suspected to suffer from autosomal dominant genetic mutations was verified by the follow-up audiograms that have been performed after at least 18 months in between. An extensive guide and review on AudioGene v4® audio-profiling as a machine-based candidate gene prediction tool for autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss offers a step to step guide for usage and outline an improved predictive accuracy with increasing data base size.21

Classification systems based on audiogram shapes accessible and easy to apply in routine practice are helpful and should be based on more clinical data. Efforts to provide national cohorts for hearing loss will be helpful to standardise classification of audiogram shapes according to their constituent parts including underlying aetiologies as well as the severity and demographic distribution of audiogram shapes.19 The electrocardiography may serve as a paradigm and future audiometers might not only give information on the patient-specific threshold but also predictions on the putative aetiology and possible progression of hearing loss. With advances in information technology and machine learning, future audiometer could be connected online retrieving information from national and international cohort data bank allowing the allocation of hearing loss to aetiology, prediction of progression and prediction of treatment outcome. This would massively easy the everyday counselling of patients in primary and secondary care including the timely admission to more specialised centres.

In the present study, a genetic analysis has not been performed according to the predictions of AudioGene yet. However, this will be the ultimate aim in utilising such assistive technologies in office-based audiology. In our analysis, two autosomal dominant mutations (GJB3 and COCH) leading to progressive hearing loss have been predicted for the majority of the analysed audiograms. Autosomal dominant hearing loss accounts for about 15% of the inherited cases of hearing loss. Up to date, more than 25 genes have been associated with autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss.15 In these cases, the audioprofile can be distinctive and can allow genotype-phenotype correlations.12 Of the more than 60 autosomal dominant deafness loci, genes have been identified only for 25. Among the 25 genes, mutations in WFS1, KCNQ4, COCH, and GJB2 are the most common.22 In our analysis, GJB3, COCH, KCNQ4, POU4F3, and MYO6 were among the top predictions. GJB3 encodes for connexin 31, a gap junction protein expressed in cochlear fibrocytes.22 The major non-collagen component of the extracellular matrix of the inner ear is cochlin, encoded by the gene COCH (coagulation factor C homology).23 In patients with a COCH mutation, deposits of the mutated protein in cochlear fibrocytes seem to lead to their degeneration.24 As a member of the POU family of transcription factors, POU4F3 is essential for inner-ear hair cell maintenance and mutations thereof lead to DFNA15.25 The molecular motor protein myosin VI is encoded by MYO6 and is known to function as either an actin-based anchor or as a transporter.26 KCNQ4, a voltage-gated potassium channel, maintains ion homeostasis and regulates the potential of the hair cell membrane.27 Many different mutations in KCNQ4 have been reported leading to loss of hair cells.27 Mutations in all of the above are associated with progressive hearing loss.

Based on the first and most recent audiogram, AudioGene analyses audiometric data and predicts the likely underlying genetic cause of hearing loss based on known phenotypic parameters.14 Interestingly, despite having nearly normal hearing or only moderate hearing loss in the first audiogram, at least for the GJB3 gene, the prediction based on the first audiogram was similar to the prediction based on the last audiogram. The high consistency of the predictions (Figure 2) indicates that AudioGene was able to identify similar phenotypic parameters despite the presence of modest to moderate forms of hearing loss in the first audiograms. Audioprofile-directed screening seems to be a powerful tool to prioritise genes for mutations screening.12,14,21,28,29 Even new mutations causing progressive hearing loss were identified after prescreening based on audioprofiles.14,30 This will be of importance in the long term for prognostic and therapeutic approaches. Current vectorisation approaches are targeting not only autosomal recessive but also autosomal dominant hearing loss for patient specific treatment of genetic hearing loss. Having an accurate, easy to use and cost-effective possibility to pre-screen patients in order to identify those at high risk for progression of hearing loss in primary care we may be able to closely follow-up these patients and accelerate the initiation of their treatment.

Figure 2.

Consistency of the predictions based on the first and the last available audiogram. Three predictions for each patient were included for the oldest and three predictions for the newest audiogram were included in the analysis.

There are several limitations associated with the herein presented study. First, clinical data on ethnicity, consanguinity and further relatives with hearing loss have not been accounted for. Second, a verification of the presence of a genetic mutation using state of the art of genetic diagnosis has not been performed.

Conclusions

Machine learning can be incorporated in highly specialised centres as well as in office-based settings to identify patients at risk for progression of hearing loss. A freely available tool for this purpose is AudioGene. However, this approach is currently limited to the identification of patients suffering from DFNA-related hearing loss. Further research and collection of patient data is necessary to allow for a wide application of ML-based predictions tools.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eda Erten for her kind assistance in retrieving the audiograms and Prof. Dr. Reinhard Matschke and Dr. Karl-Werner Herbst for providing access to the audiograms.

Funding Statement

Funding: AW and TL received funding from the Cluster of Excellence Hearing4all, EXC 1077/2.

References

- 1.WHO. Global costs of unaddressed hearing loss and costeffectiveness of interventions: a WHO report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniel E. Noise and hearing loss: a review. J Sch Health 2007;77:225-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin FR, Thorpe R, Gordon-Salant S, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:582-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musiek FE, Shinn J, Chermak GD, Bamiou D. Perspectives on the pure-tone audiogram. J Am Acad Audiol 2017;28:655-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landegger LD, Psaltis D, Stankovic KM. Human audiometric thresholds do not predict specific cellular damage in the inner ear. Hear Res 2016;335:83-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demeester K, Van Wieringen A, Hendrickx JJ, et al. Audiometric shape and presbycusis. Int J Audiol 2009;48:222-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kononenko I. Machine learning for medical diagnosis: history, state of the art and perspective. Artif Intell Med 2001;23:89-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awad M, Khanna R. Efficient learning machines. vol. 91. Berkeley, CA: Apress; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arvaniti E, Claassen M. Sensitive detection of rare diseaseassociated cell subsets via representation learning. Nat Commun 2017;8:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Gajjala S, Agrawal P, et al. Fully automated echocardiogram interpretation in clinical practice. Circulation 2018;138:1623-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasan MR, Hassan N, Khan R, et al. Classification of cancer cells using computational analysis of dynamic morphology. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2018;156:105-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor KR, DeLuca AP, Shearer AE, et al. AudioGene: predicting hearing loss genotypes from phenotypes to guide genetic screening. Hum Mutat 2013;34:539-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer N, Nishimura C, McMordie S, Smith R. Audioprofiling identifies TECTA and GJB2 -related deafness segregating in a single extended pedigree. Clin Genet 2007;72:130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hildebrand MS, Tack D, McMordie SJ, et al. Audioprofiledirected screening identifies novel mutations in KCNQ4 causing hearing loss at the DFNA2 locus. Genet Med 2008;10:797-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Smith RJH. NCBI gene reviews: hereditary hearing loss and deafness overview. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deo RC. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation 2015;132:1920-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shortliffe EH, Sepúlveda MJ. Clinical decision support in the era of artificial intelligence. JAMA 2018;320:2199-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe T, Suzuki M. Analysis of the audiogram shape in patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss using a cluster analysis. Ear Nose Throat J 2018;97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CY, Hwang JH, Hou SJ, Liu TC. Using cluster analysis to classify audiogram shapes. Int J Audiol 2010;49:628-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbour DL, Howard RT, Song XD, et al. Online machine learning audiometry. Ear Hear 2019;40:918-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildebrand MS, DeLuca AP, Taylor KR, et al. A contemporary review of AudioGene audioprofiling: A machine-based candidate gene prediction tool for autosomal dominant nonsyndromic hearing loss. Laryngoscope 2009;119:2211-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh SK, Choi SY, Yu SH, et al. Evaluation of the pathogenicity of GJB3 and GJB6 variants associated with nonsyndromic hearing loss. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis 2013;1832:285-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picciani R, Desai K, Guduric-Fuchs J, et al. Cochlin in the eye: functional implications. vol. 26. Prog Retin Eye Res 2007;26:453-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usami SI, Takahashi K, Yuge I, et al. Mutations in the COCH gene are a frequent cause of autosomal dominant progressive cochleo-vestibular dysfunction, but not of Meniere’s disease. Eur J Hum Genet 2003;11:744-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss S, Gottfried I, Mayrose I, et al. The DFNA15 deafness mutation affects POU4F3 protein stability, localization, and transcriptional activity. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:7957-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruel J, Emery S, Nouvian R, et al. Impairment of SLC17A8 Encoding Vesicular Glutamate Transporter-3, VGLUT3, Underlies Nonsyndromic Deafness DFNA25 and Inner Hair Cell Dysfunction in Null Mice. Am J Hum Genet 2008;83:278-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung J, Choi HB, Koh YI, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies two novel mutations in KCNQ4 in individuals with nonsyndromic hearing loss. Sci Rep 2018;8:16659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor KR, Booth KT, Azaiez H, Sloan CM, Kolbe DL, Glanz EN, et al. Audioprofile surfaces. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2016;125:361-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eppsteiner RW, Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, et al. Using the phenome and genome to improve genetic diagnosis for deafness. Otolaryngol Neck Surg 2012;147:975-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Heer AM, Schraders M, Oostrik J, et al. Audioprofiledirected successful mutation analysis in a DFNA2/KCNQ4 (p.Leu274His) family. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2011;120:243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]